Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted daily life globally, including education. Environmental science cautions that we must expect further disruptions as the sustainability crisis deepens. Resilience to these disruptions will be key to humanity’s survival in years to come. The pandemic constitutes a litmus test for environmental education’s effectiveness in fostering socio-ecological resilience. This paper uses Educational Action Research (EAR) to report on the impact of an environmental education intervention on students’ socio-ecological resilience during the pandemic. Using two-step participatory thematic analysis as part of the reflection phase of the EAR cycle, the author interviewed twenty students from a liberal arts college in The Netherlands about their perspectives on the pandemic. The findings suggest that environmental education can catalyse a change of perspective on the purpose of education, from instrumental to social-transformative; bring about greater concern for others in times of crisis; help to develop greater awareness of the systemic underpinnings of crises; and spur some students to take concrete action for change. However, the research cautions against undue optimism, as many students reverted to old patterns of thought and behaviour after the intervention. The EAR cycle closes with suggestions for developing better pedagogies to reach through to these students.

Introduction

Environmental and global health experts have been warning for years that the unchecked encroachment of human activity on natural ecosystems would lead to a global pandemic (Flahault, de Castaneda, and Bolon Citation2016; Gorji and Gorji Citation2021; Schmeller, Courchamp, and Killeen Citation2020; Tollefson Citation2020). The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 proved these fears to be tragically well-founded. The pandemic showed that environmental crises do not come gradually, but in abrupt jolts that disrupt global political, economic and social systems overnight. Thus, whereas environmental concerns are still too often pitted against socio-economic progress in political discourse, the pandemic has demonstrated the need for a concerted discussion on the interdependency of social and ecological resilience in the face of global environmental threats.

Resilience is a complex and multifaceted concept. Scholars have converged around a definition of socio-ecological resilience that encompasses human and environmental aspects (Lundholm and Plummer Citation2010, 481; Plummer Citation2010, 497):

the amount of disturbance a system can absorb and still remain within the same state or domain of attraction,

the degree to which the system is capable of self organization (versus lack of organization, or organization forced by external factors), and

the degree to which the system can build and increase the capacity for learning and adaptation.

In the last decade, the interconnection between environmental education (EE) and socio-ecological resilience has grown in importance (Krasny Citation2020; Krasny, Lundholm, and Plummer Citation2011). The scope for the interconnection is wide: EE has the capacity to connect individual reflexive awareness and behavioral change with systemic governance issues (Sterling Citation2011), to instill a sense of urgency and a normative drive for change that encompasses action and activism (Lundholm and Plummer Citation2010), and to foster discussions around structural power inequities (Plummer Citation2010; Stone-Jovicich et al. Citation2018).

Before COVID-19, tests of strength for the impact of EE on socio-ecological resilience could be found at the local level: for instance, in New York after Hurricane Sandy (Dubois and Krasny Citation2016) or in Haiti after devastating earthquakes (Bazin and Saintis Citation2021). The pandemic has unfortunately forced environmental educators to consider the impact of their work in the face of sudden, global disruptions.

This paper offers a reflection on one environmental educator’s work at a liberal arts college in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, as part of an Educational Action Research (EAR) cycle (McNiff and Whitehead Citation2006; Mertler Citation2019). In 2020, an eight-week second-year undergraduate EE course finished by chance on the day the first COVID-19 lockdown started in The Netherlands. The course objectives related to resilience in two ways: growing students’ resilience by developing their collaboration, reflection, and imagination skills; and fostering students’ reflection on EE as a powerful vector for resilient learning. Resilient learning has been defined as the combination of instrumental outcomes of learning (i.e. changes in environmental behaviours) coupled with personal growth (D’Amato and Krasny Citation2011; Sterling Citation2011). At the time the course was designed, it was hardly imagined that students would be called to use these skills so soon and so directly. The pandemic offered an unfortunate, unprecedented real-time litmus test. This study therefore investigated the following research questions:

What lessons can educators draw from EE students’ experience of socio-ecological resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic?

Are there different perspectives between students who followed an EE course just prior to the pandemic, and those who did not?

Using an EAR design, this paper systematizes the post-action reflection process through a two-step participatory thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2014) with 20 students, ten of whom followed an EE course and ten who did not, during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research framework

Socio-ecological resilience

The literature on socio-ecological resilience is rooted in Holling’s work on ecological resilience (1973), but has since been revisited to include a multilevel range of concerns (Walker et al. Citation2004). While agreeing broadly that resilience is ‘the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize so as to retain essentially the same function, structure and feedbacks’ (Walker and Salt Citation2012, 3), resilience scholars have focused on different aspects of resilience.

At the individual level, there has been a push to include psychological resilience within socio-ecological resilience. Psychological resilience is defined as the individual’s successful adaptation to adversity (Zautra, Hall, and Murray Citation2010) and is increasingly considered crucial in navigating environmental breakdown (Davenport Citation2017). Key aspects of individual resilience include persistence, coping self-efficacy, social competency, problem-solving ability, autonomy, sense of purpose and hope (Bernard Citation2004; Sterling Citation2011; Trombley, Chalupka, and Anderko Citation2017; Van Breda Citation2001). Krasny and Roth (Citation2010) suggested that individual resilience contributes to socio-ecological resilience by a cumulative factor within communities. Sterling (Citation2011) went further, proposing that individuals themselves may be considered ‘resilient systems’ (51). Baker, Clayton, and Bragg (Citation2021) suggested that the development of invididual resilience to climate change in childhood learning is conditional on promoting children’s mental and emotional wellbeing, with a focus on hope and action.

At the community-level, resilience has been linked to communities of practice focused on resource stewardship (Krasny and Roth Citation2010), a bond of reciprocity within communities bound by a common history with their socio-ecological environment (Kimmerer, 2013; Whyte, 2018), and a pool of strengths to resist and recover from external stressors (Krasny Citation2020). Interviewing stakeholders after Hurricane Sandy in New York, Dubois and Krasny (Citation2016) found the definition of community resilience in urban settings to be shifting towards green spaces, place attachment and stewardship actions linked to them. They concluded: ‘by including green spaces, these programs were expanding existing definitions of community resilience to link to ecological resilience’ (p. 263). Most recently, social psychology has identified forms of collective psychosocial resilience that move beyond the ‘common history’ narrative and center on shared identities as key to mutual aid and support (Ntontis et al. Citation2020). Linking individual to community resilience, Williams and McEwen (Citation2021) showed how learning for resilience focused on individual resilience helps children to develop key skills for building community resilience, such as empathy and connectedness with others.

Finally, socio-ecological resilience encompasses a systemic social and ecological level. Fazey et al. (Citation2007) identified four elements of societal socio-ecological resilience: the collective will and intention to change; possessing sufficient knowledge to inform decisions about change (knowledge about the impact of current behaviour; knowledge about the appropriate direction of change; knowledge about how to achieve change); the collective ability to accept change and modify behaviour; and proaction on part of leaders, for bold decision-making. Plummer (Citation2010) differentiated between three key dimensions of systemic socio-ecological resilience: time and space, which form the ecological basis of resilience, and symbolic meaning-making, which springs from the social dimension. This third aspect involves the ‘creation of a hierarchy of abstraction that permits a degree of divorce from space and time; increasing and intensifying reflexivity that is limited in dealing with complex issues and multiple time scales’ (498). Smith and Stirling (Citation2010) suggested adding technological considerations to this already broad understanding of systemic resilience. This suggestion has since been taken up by a large span of authors from different fields such as geography, agriculture, and computer sciences, with a common theme of using data networks to increase predictability of and reactivity to climate extremes (Hills, Μichalena, and Chalvatzis Citation2018; Lipper et al. Citation2017; Sarker et al. Citation2020).

The broad focus of socio-ecological resilience has made it difficult to discern its implications for learning. However, in the last decade, a growing movement in EE has built onto the socio-ecological resilience literature.

Socio-ecological resilience and environmental education

The first point of articulation between socio-ecological resilience and EE is the connection between learning and adaptability. It has been suggested that environmental education can provide key skillsets for adapting to adverse circumstances at the individual and collective levels, and more importantly, the will to change (Fazey et al. Citation2007). Numerous student-centred, active pedagogies have been proposed to this end; for instance, social learning, and problem-and-project-based learning (Ban et al. Citation2015; Krasny, Lundholm, and Plummer Citation2010; Kricsfalusy, George, and Reed Citation2018). Krasny and Roth (Citation2010) have suggested that designing EE in the light of Activity Theory, a goal-oriented and action-driven approach to learning, can amplify the impact of EE on socio-ecological resilience. Krasny and Roth proposed that Activity Theory has a greater potential to embed adaptation to real-world environmental contexts into EE than personal growth-oriented approaches. Critiquing situated learning theory and transformational learning theory, which, in their view, focus on learners’ internal processes, Krasny and Ross suggested that Activity Theory’s focus on ‘adaptive co-management’ (p. 547) would benefit socio-ecological system adaptability. Sterling (Citation2011) addressed concerns that such a link between EE and adaptability might be viewed as ‘instrumental’ by offering points of conciliation between instrumentality and a second interpretation of EE as ‘instrincally’ beneficial.

The ‘intrinsic’ view invites EE to ‘adopt and accept key ideas about participative and contextualised learning, about social–ecological systems and their well-being, about dynamic systems concepts, as well as the need for paradigm change towards holistic and integrative thinking and approaches’ (Sterling Citation2011, 49). Resilience in this sense is not an end-product but part of the process of EE, which becomes in itself ‘transformational learning’ (Krasny and Roth Citation2010). This view has gained traction in recent literature, where EE is seen as a space where learners’ wellbeing and social support networks can flourish (Krasny Citation2020), where emotions such as anxiety, grief, loss, guilt, shame, hope and joy can be processed (Pihkala Citation2017). To do so, experiential pedagogies have been put forward such as community gardening, urban community forestry, watershed management, drama and arts-based EE, mindfullness and spiritual activities and experiences (Chang Citation2020; Gómez-Olmedo, Valor, and Carrero Citation2020; Krasny and Roth Citation2010; Pihkala Citation2017).

Common to both views of resilience in EE is an explicit normative commitment to change: to develop resilience in EE is to invite learners to action as citizens, voters and consumers (Lundholm and Plummer Citation2010). There are two normative dimensions in play: firstly, the effectiveness of educational policies and curricula in aligning with learning outcomes for change. Secondly, ‘asking whether EE is adequately preparing students to tackle environmental challenge and to function under conditions of radical uncertainty and environmental breakdown’ (Plummer Citation2010, 502). In particular, several scholars enjoined EE to tackle issues of structural inequality and power dynamics head on (Plummer Citation2010; Stone-Jovicich et al. Citation2018). It has been suggested that the fluid and socially constructed nature of normativity, the process through which certain ideas and practices congeal into norms with moral weight, comes with a responsibility for reflexivity (Krasny, Lundholm, and Plummer Citation2010; Lundholm and Plummer Citation2010; Sterling Citation2011).

Environmental education, socio-ecological resilience and COVID-19

While there is a body of literature to build on, discussions on environmental education and socio-ecological resilience which abounded a decade ago have gone somewhat quiet since. In the last year, environmental education research has reacted to the implications of the Coronavirus pandemic for future-proofing EE (e.g. Kaukko et al. Citation2021; Rios, Neilson, and Menezes Citation2021). These EE scholars draw links between the disruptive impact of the pandemic and future disruptions expected from climate change and biodiversity collapse. They call upon EE to capitalise on the experiences of the pandemic to strengthen EE’s relevance for future crises. However, the discussion of socio-ecological resilience in EE in response to COVID-19 has been muted, so far. Román et al. (Citation2021) discussed the impact of the pandemic on EE in terms of community resilience in the Galapagos, and the Editorial Board of The Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education published a collection of teachers’ experiences of the pandemic in which several accounts mentioned resilience (Quay et al. Citation2020). But aside from this, not much has yet been published on socio-ecological resilience, EE and the Coronavirus pandemic. This present paper connects the body of research on socio-ecological resilience and environmental education presented above with action research and the coronavirus pandemic.

The pandemic provided an unprecedented global litmus test for many ideas on EE and socio-ecological resilience: the scale of the crisis lends itself to analyses at all levels of resilience (individual, community, socio-ecological system). The new physical and virtual delineations of emergency remote teaching in the lockdown periods have implications for resilient learning both at the instrumental level (e.g. complete halt of the climate movement’s protest activities during lockdown), and the intrinsic level (e.g. wellbeing and social connections were both likely impacted by social distancing). At the same time, the global scale of the crisis laid bare structural issues that were less widely recognised beforehand, such as global supply chain issues and global health coverage inequity, offering an opportunity for renewed discussions on power and norms in EE. These issues will be explored in the rest of the paper.

Methodology: Reflecting in EAR with thematic analysis

Educational action research

EAR is generally understood to comprise two chief characteristics: firstly, an EAR cycle begins with an investigation phase, leading to an action phase, followed by a reflection or evaluation phase (McAteer Citation2013; McNiff and Whitehead Citation2006). Secondly, a participatory inquiry process is led by the educators themselves with their students, with a view to improving practice (Bradbury, Lewis, and Embury Citation2019). At the time of writing, the inquiry process prior to the education intervention was already completed and published (Servant-Miklos and Noordzij Citation2021), and the education intervention was already developed and carried out (Servant-Miklos and van Oorschot Citation2020). Although an EAR cycle was already underway, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the author to rethink and redesign the reflection phase in the light of global events. EAR has the advantage of being flexible, adaptable, and designed to fit the ‘messy’ reality of practice (Cook Citation2009). However, this is not an invitation to do away with analytical rigor. On the contrary, EAR scholars have enjoined practitioner-researchers to consider investigative rigor (Cook Citation2009; Rowell Citation2019), and research validity (Dosemagen and Schwalbach Citation2019) during each phase of the cycle. There is, however, no precise methodology prescribed to this effect. Therefore, borrowing from well-established traditions in qualitative educational inquiry, this paper took a Thematic Analysis (TA) approach to the reflective phase of the EAR cycle (Braun and Clarke Citation2014), with this difference that whereas TA is traditionally not participatory, EAR calls for building student participation into the process (Bradbury, Lewis, and Embury Citation2019). This was done by adding participatory focus groups during which the emergent themes were discussed with participants. Although the full cycle is explained in this section, this paper only presents the results of the post-action evaluation phase.

Investigation: The first part of the EAR cycle

The study presented in this paper forms part of a broader EAR cycle, which started in 2018 in an English-language liberal arts college that offers bachelor’s degrees with majors in Life Sciences, Social and Behavioural Sciences, Economics and Business and Humanities. Between 2018–2019, taking the role of an academic researcher acting as a ‘critical friend’ to the then-course coordinator (Olin, Karlberg-Granlund, and Furu Citation2016), the author of this paper evaluated the impact of the existing climate course at the college by interviewing the students who had taken the course, and the teachers who had designed and taught the course. This was a course heavily influenced by Science and Technology Studies, delivered through problem-based learning and lecturing. The detailed results of this investigation were published elsewhere (Servant-Miklos and Noordzij Citation2021). In summary, the investigation revealed the importance of critical, humanistic inquiry into environmental issues, but also identified identity dissonance, defined as a conflict between students’ western middle-class socialised identity and their aspiration towards a moral identity in which environmental care is defined as a moral good. This dissonance acted as a barrier to change in students’ environmental beliefs and behaviours, and they were found to use strategies such as bargaining, blaming and fatalism to deflect moral responsibility. Following this initial investigation, the author changed position from external academic researcher to internal course coordinator, and the old climate course was replaced by the author’s new course, The Climate Crisis, in 2020. This changed the nature of the author’s role in this project from primarily academic researcher and ‘critical friend’, to primarily practitioner-researcher (Niemi Citation2018; Olin, Karlberg-Granlund, and Furu Citation2016). However, the project remained an Educational Action Research project rather than practitioner-research or pedagogical action research project in that the author dialectically negotiated her position as an educational and pedagogical scholar, and a course coordinator and teacher. Following the tenets of action research, the author’s purpose was ‘planning, acting, observing and reflecting on one’s practices’ (Rönnerman Citation2003), but moving beyond practitioner-research and into EAR, the author also aimed to ‘develop knowledge and understanding of one’s practice that can be shared with others’ (Capobianco and Feldman Citation2006, 499).

Action: The climate crisis in 2020

Different disciplinary problematizations of the climate crisis inspired the author’s new course design. Recognizing the entanglement of environmental and social justice issues, the learning activities were developed around a critical pedagogy framework, in which education was seen as problem-posing, critically reflexive, praxis-oriented, and socially-transformative, rather than transmissive (Biesta Citation1998; Servant-Miklos and Noordegraaf-Eelens Citation2021). The content was inspired by scholars working in the ‘environmental humanities’, drawing on Science and Technology Studies (Latour Citation2017; Stengers Citation2009), eco-feminism (Haraway Citation2016; LeGuin Citation1986; Tsing Citation2015), environmental psychology (Lertzman Citation2015; Cunsolo and Landman Citation2017), and critical political economy (Parenti and Moore Citation2015; Weston Citation2015).

In 2020, around 80 students were enrolled in the course. The course structure is indicated in .

Table 1. Structure of The Climate Crisis course.

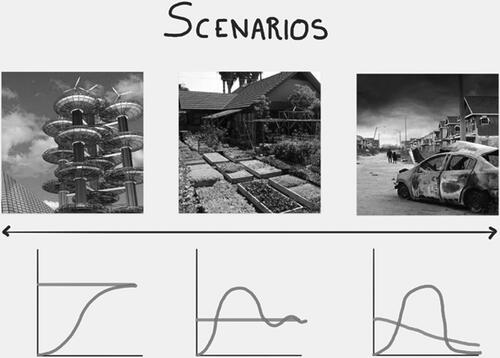

The new course responded to students’ identity issues raised in the earlier part of the EAR cycle by asking them not to just look for ‘solutions’ in the shape of more sustainable production, but also to reconsider what it means to be human in the context of a radically warming world. Alternative world-views to the prevailing ‘capitalist realism’ (Fischer Citation2009) were presented through the lens of eco-feminism (Haraway Citation2016; LeGuin Citation1986; Tsing Citation2015) and indigenous environmental perspectives (Cunsolo and Landman Citation2017; Simpson Citation2017). The course was delivered through problem-based learning (PBL), project-based learning and speculative fiction (speculative fiction, or SF, an environmental thinking-with tool developed by Haraway Citation2016). Each week, students attended a PBL tutorial, covering six problems over the duration of the course. As an illustration, shows one of the problems from the course. In groups of twelve guided by a tutor, students discussed this ‘vignette’ with no prior reading or explanatory lecture, after which they formulated learning goals for the following week’s reporting phase, following the ‘seven-step’ method of PBL (Servant-Miklos, Norman, and Schmidt Citation2019).

Figure 1. PBL Problem Week 4: Future scenarios in a warming World.

Scenario 1: Social Capitalism; Scenario 2: Post-capitalism and controlled de-growth; Scenario 3: Collapse

The course assessment comprised three elements: a group project in which students designed and recorded a podcast on the climate crisis in the Netherlands; a short individual self-reflection essay on their personal journey through the course; an individual speculative fiction essay in which students were tasked with imagining life in the year 2100.

The course developed key themes of socio-ecological resilience in EE: the utilization of psychological insights related to individual resilience, reflexivity in learning, contributions from indigenous and eco-feminist scholars about community resilience, discussions of power structures and inequity in societal resilience, and speculative fiction as an individual and collective normative exercise in willing change.

Evaluation: Reflecting on the action through thematic analysis

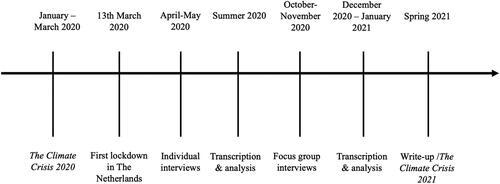

To evaluate the impact of the action stage of the EAR, the author used a two-step TA consisting of student interviews, as highlighted by the timeline in . The findings from these interviews are presented in this paper. While this paper only has one author, the other teachers were consulted and involved in discussions on the findings, particularly as they fed into the following year’s iteration of the course.

Designing the interview protocol: Identifying resilience surrogates

Designing the interview protocol presented a double difficulty: investigating a fuzzy concept (resilience) in a messy process (EAR). Asking students to discuss resilience directly would possibly confuse them, and given the overwhelmingly positive connotation of ‘resilience’ among students (Kharrazi, Kudo, and Allasiw Citation2018), risk students trying to appear ‘resilient’ to the interviewer. Therefore, the author followed the four-step process developed by Bennett, Cumming, and Peterson (Citation2005) to identify surrogates for resilience. The procedure consists in identifying a ‘system of interest’ (Plummer Citation2010, 501) for investigation, then mapping out the interrelations between the elements of the system. From there, researchers look at how changes in variables within the system affect the distance from the present state of the system to a threshold state in which the system is transformed. Although the process is couched in quantitative terms, translated into a qualitative context, it involves mapping relevant elements within the systems of interest and their interactions in feedback loops, then looking at what variables determine the direction the system takes when a change occurs. EAR simplifies the task of identifying the system of interest, since the latter is always situated around the educational practice under investigation. Through a mapping exercise informed by the research framework outlined in the previous section (in particular: Krasny, Lundholm, and Plummer Citation2011; Sterling Citation2001; Wals Citation2007), the author identified two key surrogates within the system of the EE classroom:

Students’ perspectives on education: social norms prevailing in and around education as key to maintaining the educational system in its present state. When the social consensus around education breaks down, education is forced to change. The new system that emerges can only be sustained if it receives social support.

Students’ visions of the future: the educational system rests on the promise of delivering students unto a brighter future. If the social contract breaks down, education is forced to change. The new system can only be maintained if it promises a future that resonates with learners.

What were students’ prevailing beliefs about education and the future prior to the pandemic? Did these maintain or challenge the education system? Did environmental education affect this in any way? What happened to these beliefs during the pandemic? Were there differences between students who took The Climate Crisis and those who didn’t? The interview protocol (see Appendix) was designed to investigate these questions.

It would have been preferable to interview students before the start of the pandemic to obtain their perspectives on education prior to the pandemic. However, due to the unforeseen nature of the pandemic, this was not feasible. Instead, the interview protocol asked students to ‘go back in their mind to their mindset prior to the coronavirus pandemic’. While the reconstruction biases associated with this exercise constitute a limitation of the study, all participants made a sincere effort to portray their pre-pandemic beliefs honestly.

This surrogacy approach aimed to address the broader research question about students’ experience of EE and socio-ecological resilience in the pandemic: what is the impact of this kind of course on the overall resilience of the education system within which it is embedded? What is its impact on the individual and community resilience, as defined in the literature review, of students after they leave the course? How does the intervention impact the resilience of the systems in which it is embedded in the face of brutal changes brought about by ecological disasters like COVID-19? These are messy questions, in a messy process, in a messy time. As Cook (Citation2009) pointed out, EAR’s unique capacity to build rigor in the mess lies not in the precision of its methodological approach, but in its participatory design and a thorough, reflexive analytical process.

Recruiting participants

In EAR, the participants are drawn from the students and teachers involved in the education intervention. However, the pandemic situation was so novel and disruptive, that it would be difficult to draw conclusions from just speaking to students who experienced the course. Therefore, the author decided to also interview students from the same college, but who had not taken the course.

Purposive sampling was used to select ten students who took The Climate Crisis in the Spring 2020 semester, and 10 students who had never taken the course as of 2020. An equal representation of male and female students was chosen, with a distribution of majors that fairly represents the broad sweep of student perspectives at the college. shows a pseudonymised list of participants.

Table 2. List of participants.

Research process

Round 1. The students gave written consent to be interviewed individually during the first two-months lockdown in the Netherlands. The interviews were done online, given that face-to-face meetings were proscribed by lockdown rules. They were conducted in English, the lingua franca of the college, lasted around an hour each, and were recorded using the videoconferencing software. The audio recordings were transmitted to a research assistant who transcribed them verbatim. The author read through the transcripts and checked them against the audio for accuracy and to get a full picture of the interviews. Then, the transcripts were imported into Atlas.ti where the author proceeded to a round of free coding, attempting to conceptualize the ideas expressed by the participants. At the end of each transcript, the author wrote a memo with impressions and ideas. The codes were cross-referenced with the memos to proceed to a second, more systematic round of coding. Overlapping codes were harmonized, codes were checked against the data in a process of constant comparison. Then, the codes were compared against each other using Atlas.ti’s code manager tool. From there, the codes were sorted iteratively to surface the main themes. The transcripts were read one last time with the codes and the themes to hand in order to check that the interpretations fitted the data.

Round 2. The themes were presented to half of the students in each sub-group (Climate Crisis, CC, and did not take Climate Crisis, NCC) in an online focus group setting described in . They were invited to critically reflect on the author’s interpretations, suggest counter-interpretations, explanations and clarifications. The groups were kept small to account for the online setting, and lasted about one hour each.

Table 3. Focus group compositions.

The focus group interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed using the same procedures as Round 1. The results were then presented to the teaching community of the university through an internal conference, where informal feedback was incorporated into the analysis.

Results

Contrasting beliefs about education prior to the pandemic

Both groups of participants reported seeing education as a vehicle for personal growth prior to the pandemic. Most of the students saw their university years as a journey of self-discovery, self-improvement and maturation. They craved intellectually and socially stimulating environments that enabled them to grapple with existential questions, experience adventure and successfully overcome challenges.

Melissa (NCC): I think for me, 100% personal growth and self-actualization and trying to find what you love that will let you maybe, indeed one day work in what you love.

Nearly all of the participants expressed intrinsic interest in their studies, and interest in developing metacognitive skills such as learning to learn, and involving themselves in the academic process:

Kevin (CC): Generally, I believe [university] is meant for you gaining understanding of new things and kind of and involving yourself in the world of science with whatever form that may take.

In both groups, there was also a less prominent but nonetheless consistent instrumental view of education as a career-building opportunity.

Amy (CC): I think for most jobs that I would be interested in, you need a university degree. So it’s kind of even maybe an economic choice.

Noa (NCC): [My parents] worked very hard and left a Third World country and they wanted me to have the biggest opportunity for myself. I didn’t want to be a doctor or a lawyer, but I definitely wanted to have a very good job after college and work very hard.

Though students were aware of the advantages procured by university education on the job market, they generally chose personal growth over career cost-benefit calculation when the two conflicted, which is not unexpected in a liberal arts setting.

The main difference between the two groups of participants is the existence of a third perspective on education within the EE group: education as transformative. Students who took The Climate Crisis expressed dissatisfaction with the neoliberal status quo on education, and held the belief that education could bring about radical social change.

Jake (CC): I got involved with university matters at the college through the Student Academic Affairs Council last year, and there it became clear that what the university is doing is training us into productive machines. […] So it became clear education needs to be something else, it can’t work like this. Then, through the Climate Crisis course, … it gave some content to this feeling of: ‘something needs to change’.

Raymond (CC): We have to structure our education in such a way that we feel that we have the ability to tackle these wicked problems and that we feel a link to what’s going on outside our classroom, that we feel agency in these situations and have the skills to tackle them.

This difference between the two groups was discussed with participants in the focus groups. The author reflected with the participants on the possibility of selection bias: that students who took The Climate Crisis would have been inclined to a social-transformative view of education in any case. However, many of the participants who did not take The Climate Crisis also expressed an interest in environmental and social issues in general – such concerns are widely shared within the college’s student population. The participants from The Climate Crisis honed in on the course’s specific effect on their views of education. Firstly, it was their first course that took itself as a subject of critical observation:

Jake (CC): I think what rarely happens at the college is… this gaze that turns inward towards the education that we’re receiving. So there’s a switch… where suddenly it’s like, take a look at what you are doing, what you’re being taught and what you’re learning, and reflect on that.

Second, the critical, participatory, problem-posing nature of the course also brought students to question what they knew about education’s role in the world.

Amy (CC): I was shocked that university hadn’t taught me [about climate change] before, or that it wasn’t included in the core courses. Something that is happening to our world right now. And it’s not being taught to us. Instead, we get core economics […]. I think this is really where things started rolling… Just by asking a lot of questions about ‘why is this this way, and how can we change it?’

The participants who did not take The Climate Crisis were also confronted with this difference in perspectives in the focus groups. They explained that education reflects society’s prioritization of individual achievement, and this coloured their views on education:

Nina (NCC): [Education] doesn’t really encourage coming together, maybe as a society to create change. I think it encourages more, you know, you to think of your own fate and to act as an individual.

So while the conception of education as a vehicle for personal growth dominated overall, the view of education as socially-transformative was only expressed by students who took the course. This finding is interesting in how it relates to students’ reactions to the pandemic.

The pandemic: From shock to care

Almost all of the students interviewed experienced psychological shock and distress from the sudden onset of the coronavirus pandemic. The dominant emotions were apathy, anxiety, lack of motivation to study, and a desire to retreat into isolation until the storm passes.

Rosa (CC): I was just crying. A lot of the days, just doing nothing. Also thinking in circles, isolating myself a bit from other people as well… Then I took some days off from studying because I was like, ‘this is not gonna work’.

Maria (NCC): I was a bit freaked out in the beginning because I also heard from a friend that the army was preparing for lockdown. And also, you know, with the supermarkets, with the empty shelves, like, that was a bit chaotic. And just kind of scared to not know what was going to happen next. […] With all the classes and everything online, I think it’s a little bit hard… It’s a bit challenging to find that motivation, I think, to get your stuff done.

Because of the middle-class socio-economic background of these students, they were mostly able to retreat to their parents’ houses where they had their own space and family support to ride out the lockdown.

There was a striking difference between the groups of participants in how they reacted to the lockdowns after the initial shock. The group who did not take The Climate Crisis mostly closed in on themselves, focusing on their own productivity and personal growth in quarantine.

Noa (NCC): I try to write out my goals for the day and I try to talk out loud to my roommate, like, ‘Oh, I’m gonna do this and this,’ and then she holds me accountable for some of it. […] I’m a member of the University Council, and we’re still progressing with their meetings. So I’ve just kind of decided to take on another project for that. I’m gonna make a podcast for the University Council, just about information. And that’s something I normally would never have taken on during the regular quad [half-semester] with everything going on. So just something to give myself more work for.

Melissa (NCC): I’ve been focused a lot on trying to improve part of myself, getting up a bit early and just taking a walk and trying to set some routines… I’ve been thinking about that a lot, the kind of things that make your life more structured, but in a good way, and make you feel good as well. Like, just taking a little bit of time to read a book or do some things that are a bit more. I mean, that’s also everywhere, like on Instagram, like ‘now’s the time to go back to your roots’.

This focus on personal productivity was accompanied by increased feelings of anxiety, stress, and guilt, as students pressured themselves to remain productive without taking the time to process what was going on.

Melissa (NCC): There was… a lot of pressure to be like, ‘oh, now we can finally slow down. Let’s read books about racism, and feminism and capitalism. And let’s do yoga every day. And let’s, you know, like, now’s the time to do everything we ever wanted’. And yeah, that was definitely difficult. I don’t think there was really the thought of: ‘oh, let’s process this’.

Joe (NCC): And so this year would have been a very pivotal year, I would say for both my academics and myself personally. And the realization of that has made me feel incredibly guilty about not being able to explore or have the same experiences that I would have had without the pandemic, not being able to develop personally on the same level.

They also found it very difficult to empathize with less fortunate people suffering through the crisis:

Nina (NCC): I would not say I’m not an empathetic person, you know, and it’s that I don’t care about others, but I found it really difficult. Maybe it was also like… a feeling of just like being overwhelmed, you know, by so much.

While this attitude was also present in some of the participants from EE group, other participants in this group also expressed intense feelings of empathy and care for less fortunate people suffering through the crisis. However, these were quite abstract feelings, which they struggled to concretize into action during the lockdown.

Jake (CC): My girlfriend and I started crying in bed. But even those emotions are super abstract. Like the first thing I said she was like, ‘oh, what’s up?’ and I was like, ‘it’s just unfair how much better off I am than others’.

They also struggled to project themselves into the future, in terms of the immediate aftermath and longer term consequences of the pandemic, as Gina expressed in the focus group interview, just after the end of the first lockdown, before the start of the second lockdown.

Gina (CC): why should I be in this in this situation where I’m anxious about the future, it will come either way. Kind of like that. So, Carpe Diem! But I can use this situation right now, to at least be more at ease. And I kind of push that to the back of my mind and just enjoy the freedoms that I’ve gained again.

Even with the experience of the first lockdown behind her, as caseloads were increasing and it was apparent that there would be a second lockdown, she could not adjust her mindset to prepare for further disruption to her life. This dissonance was mirrored almost exactly in these students’ attitudes to the climate crisis, as we shall see in the final section of the analysis.

After the initial shock of the lockdown, Amy, Madeleine, Rosa, Raymond and Jake did translate their concerns into social action. However, they also expressed fatigue as a result of the drawn-out nature of the pandemic:

Amy (CC): maybe some social engagements that I’ve started taking now that were because of COVID have become just more like a normal thing that I do. I mean, I hear also Rosa, that you’re like going to the food bank. I don’t know if this was something you did before, but maybe there is less raw energy…

Rosa (CC – continued): Yeah. Yeah. […] There was really this great sense of urgency. And now… that sense of urgency is just going down a bit. But as Amy said, in the lockdown, I also decided to take a minor for Transformative Change, which I’m doing right now. I still work at the food bank. So there’s definitely things that I’ve taken from it. But that yeah, it’s not like I’m living on that sort of the peak of energy anymore, it’s a bit more flat.

The difference between the individual productivity and social prioritization was discussed in the focus groups. The students who did not take The Climate Crisis were honest about their reasons for focusing on themselves:

Nina (NCC): I think that’s also kind of what society is communicating to you, right? […] I think it’s communicated to you in this very individualistic perspective, that your life is what you make out of it. And if you don’t end up with a great life, then that’s basically on you, right?

Joe (NCC): I felt too preoccupied with myself to step outside of that bubble. And look around me and see how I can, for example, volunteer at a food bank. I did do that once. […] But it was more filling in position. So even doing that job that day, I didn’t make a connection of: ‘Oh, we need they need extra help, because of this crisis, because of the pandemic because of there being there being problems with food supply, where people aren’t getting the amount of food they need, because they lost income’. And I and I honestly don’t know why I don’t make that connection and why I don’t have that altruistic side to me, as much as I maybe should. I was also just too involved with my own personal affairs.

Although not all of the students in this group were as brutally honest as Joe, most of them expressed feeling similarly wrapped up in their own affairs, too worried about gaining a competitive advantage in a post-pandemic job market to think about others. The decision to focus on self-growth or to engage in social action opened up a conversation about power and privilege.

Power, privilege and solving systemic problems

Both groups of students understood the coronavirus crisis as a systemic issue rather than a random event. The students without exception credited their Humanities courses for this critical perspective on current events, even among Life Sciences majors (Humanities courses are mandatory across all majors).

Stephanie (NCC): In the Humanities department, we’ve read philosophers that reflect on what has happened in history. So maybe that line of thinking is something that I take with me. Like, the ways in which this can affect the world in so many different levels… I do think it has helped me understand what is happening now.

Andre (NCC): Seeing friends’ reactions to the virus was something that I found interesting, because I think I’m thinking mainly of [a course] called Science, Technology and Society in the first quad at the college. And that was, I think, was the most important one, because it gave me a nice perspective on maybe why people misinterpret science, which was a big thing during this whole [pandemic] that frustrated a lot of people.

However, the systemic analysis of the pandemic was deeper within the group that took The Climate Crisis. They referred to more theories, went into more in-depth analysis, and in particular, gave an analysis of the linkages between systems of production, environmental collapse and pandemics.

Madeleine (CC): I just had this massive realization that this is not the last crisis that I’m going to live through. It’s going to be one of many, many crises. […]And then I also realized it’s not the first crisis, right? Because I read, especially the indigenous texts really influenced this, that there’s people who live in a permanent state of crisis and extinction.

The students from the group who did not take The Climate Crisis were less reflexive on their own position, preferring an ‘all in the same boat’ narrative.

Stephanie (NCC): It’s something that has hit everyone, so everyone is involved in this crisis, the virus doesn’t exclude certain people from it. So in that sense, I think because everyone shares this, and of course, there are different levels and it hits people differently, but the fact that everyone has to cope with this reality also gives a kind of comfort, I think, because we’re all in the same boat.

Their main focus in the pandemic was frustration about the disruption to their lives, such as the cancellation of travel, exchange programmes, and social events. Being less reflective about their position of privilege disinclined students from societal or community engagement:

Noa (NCC): there wasn’t really much I did with, I don’t know, like, community service and stuff. I mean, there wasn’t really much you were… you could do, you were in a lockdown.

Andre (NCC): besides doing the work I had to do to finish my bachelor’s obviously, I didn’t really do anything else, like outside of my own personal stuff. I think… that’s how I took it, as an opportunity, like you can, you know, work on your own stuff?

On the whole, both groups of students were quite pessimistic about the possibilities for systemic change after the pandemic. The Climate Crisis students expressed a deep frustration with human nature and political decision-making. They felt defeated by the evidence that governments chose to support the old systems rather than see this as an opportunity for radical change.

Charles (CC): I truly believe that people have a lot of trouble changing deeply. As humans, we are more or less the same and we’re driven. And we always go to the easiest way. And we’re always trying to trying to be comfortable and so people will never voluntarily give up on their comfort and give up on the standards of life. Even if it means driving everyone to their end. So I think I am very pessimistic about the future.

Amy (CC): Yes, it’s a crisis. Yes, it breaks normalcy. But also, it feels like it’s just going to turn out the same way that it always does, where we’re going to bail out people who are already privileged, and then people who are starving will be like, ‘Oh, no, there’s a famine. How could that have happened?’ So yeah, I don’t know, for the future of society… I feel quite pessimistic, I will admit.

In the final section of this analysis, we look at how EE has impacted students’ vision of the future.

Envisioning the future

Despite their pessimism about the future, the students who took The Climate Crisis credited the course with giving them some of the tools to think through the pandemic, and while they were not optimistic about avoiding system collapse, they did feel more comfortable with the idea of navigating that collapse.

Jake (CC): During the Climate Crisis course, we had this conversation with the tutor, about whether we’re afraid about the future… I remember thinking… yes, it seems like we will have huge transformations, and there’s going to be a lot of uncertainty, people will suffer, but at the same time, they’re already suffering now. This is a change which you can latch on to and use it to make something better and try to make the best out of it. And it’s better than staying in this current system.

Rosa (CC): I was talking about this with friends the other day: what would you do the rest of your life if it wasn’t for the climate crisis? I said, well, I would have probably become a journalist or a teacher… But then right now I really see myself in – or at least I hope that will happen – making connections with other people and creating another reality and trying to shape the world in which I want to live with others.

There were two elements of the course that struck a particular chord with students in terms of connecting present and future: the reflection piece, and the final world-building essay.

Jake (CC): So in the [reflection] assignment, I’d written about this episode in the David Attenborough documentary where you see all the walruses tumbling down the cliff… and then during the pandemic when it was so warm, I felt a lot more attentive to how the forest that is in my parents’ backyard, how that is really suffering during this heat and I could really empathise more with the trees dying.

Rosa: [the final essay] allowed me to engage with the stuff I wanted to engage with. When this was happening, and I was like, okay, thinking about everything that is wrong about the system we have right now is not really going to bring me anywhere right now. Just makes me really sad and it paralyzes me. So imagining how things can be different and how I can be part in that and how I can be a part of that with other people, that really helped me coming out of this negative spiralling thoughts.

The course spurred a few of the students into concrete actions, like Andy, who wants to start a green consultancy company to help businesses in their green transition:

Andy (CC): because of the things I learned in Strategy, together with what I was learning in Climate Crisis, I realized like, okay, wait a minute, if we address this problem of the climate crisis, by being able to create shareholder value, with what I learned in strategy, then there is no way a shareholder will ever say ‘No, let’s not take the sustainable option,’ if they can get money out of it. So when I realized that because of those two courses together, I think that’s when that idea started unfolding.

Madeleine, Rosa, Jake and Raymond, among others, organised a town hall at the college that was attended by over sixty students. A letter was subsequently drafted to the college management team requesting a broadening of the college’s commitment to sustainable education.

However, other students like Sharon, Gina, Kevin, and Charles struggled with the same dissonance they experienced with regards to the pandemic: while they could imagine that life would have to change as a result of climate change in the abstract, they could not relate to it personally and concretely, and therefore reverted back to old patterns of thinking.

Gina (CC): I should prepare myself, there should be preparation in society, for more crises to come or just this one to never end, basically. But I kind of choose to be in that role, where I think ‘okay, for now, everything’s fine. And I don’t need to worry’. Even though I know in the back of my mind that I should still worry that it’s not over, that this worry should never stop.

Kevin (CC): I haven’t thought that much about that, to be honest, but I doubt it will change anything radically in the span of, let’s say, a century.

Amy suggested that while The Climate Crisis did a good job of laying out possible futures, a concrete bridge between present and future was missing, which incapacitated some students from identifying with these potential futures.

Amy (CC): The last assignment was about thinking about a potential future. I think the idea was to engage… to be open to possible futures, how would we get there and what they mean, but maybe to then highlight the connection we have to those futures, and not to put them in something outside of ourselves.

The discussion section of this paper connects these findings with EE practice and socio-ecological resilience.

Discussion

Student perspectives on education and resilience

Some of the students who took part in The Climate Crisis developed a view of education as social-transformative that challenges prevailing narratives of education as either instrumental to entering the job market (Collini Citation2012), or supportive of individual lifestyle development (Giddens Citation1991). This change contributes to the paradigm shift from education about sustainability to sustainable education first identified by Sterling (Bosevska and Kriewaldt Citation2020; Sterling Citation2001, Citation2011). The pandemic provided insights on the impact of this change in perspective on students’ resilience. Students who prioritized education for job-market competitivity and personal development experienced greater stress and anxiety about their personal productivity in lockdown. Students who focused on the impact of the pandemic on others gave themselves more time and space to feel despair, numbness, shock, and empathy without the pressure to be productive or learn new skills. They were arguably less anxious about their schoolwork, while some channeled their feelings into community work. This could be viewed as a ‘successful adaptation to adversity’ (Zautra, Hall, and Murray Citation2010), and expression of social competency and sense of purpose (Bernard Citation2004; Sterling Citation2011; Van Breda Citation2001) that contribute to individual resilience. Rather than building community-resilience through a ‘cumulative factor’ (Krasny and Roth Citation2010), one could read this as a shift in the constituent parts of the individual as a ‘resilient system’ (Sterling Citation2011), where the sense of self becomes entangled with community systems and belonging to the world with others. It is therefore hard to draw lines between the impact of The Climate Crisis on individual and community resilience in the pandemic, the two being perhaps more deeply interconnected than the literature on socio-ecological resilience currently implies.

The educational perspectives of the students who took The Climate Crisis could push two of the factors for systemic resilience proposed by of Fazey et.al. (2007) – namely, seeing education as providing knowledge to inform decisions about change, and generate the collective ability to accept change and modify behaviour. However, EE students were more skeptical about education’s potential to affect proaction on part of leaders or the collective will and intention to change. One could argue that these students were betting on education as a vehicle for community resilience to offset collective failure at the systemic level.

Student perspectives on the future and resilience

Students who took The Climate Crisis were aware that humanity has entered an era of permanent crises. Though they could engage with this on an abstract, imaginary level, they struggled to effect this into a concrete vision for their own future. The dissonance experienced by these students might impede their coping self-efficacy, and thereby their individual resilience (Trombley, Chalupka, and Anderko Citation2017). Perhaps as a coping mechanism, these students experienced community-resilience ideation, romanticising indigenous lifestyles and eco-communities and building imaginary futures of togetherness.

The world-building assignment seems to have provided an escape to some students who felt invited to dream of a changed world on paper while experiencing the isolation of lockdown. Two reactions emerged from this. On the one hand, as soon as the lockdown ended, students like Gina and Sharon reverted to individualistic patterns of thought and behaviours as seen in the group that did not take The Climate Crisis. On the other hand, more than half of the EE students engaged in action after the initial shock of the lockdown, organizing sit-ins at the college, volunteering for community organisations, and making further decisions about their education, career and life with ecological collapse in mind. This ties in with the findings of recent social-psychological literature on utopian thinking, which predicts that abstract imagination will lead to increased engagement and action (Badaan et al. Citation2020; Bagci, Stathi, and Piyale Citation2019). This also bridges community and system resilience, approximating what Plummer (Citation2010) termed a ‘hierarchy of abstractions’: a group of students committed to abstract transformative educational perspective and a community-oriented vision of the future was able to incite concrete change at the level of the university system. Indeed, as a result of these students’ actions, the first year curriculum has been changed to include climate change and sustainability issues throughout the year, including an introductory course on climate change for incoming first-years.

EE, socio-ecological resilience and the climate crisis

Closing the EAR cycle involves reflecting on the implications for the further practice of this course in particular, and EE more generally.

Reflexivity is a key theme of socio-ecological resilience and environmental education literature and a core design feature of The Climate Crisis. However, it became apparent that reflexivity on its own is not sufficient to impact resilience at all three levels – all of the students, including those who did not take the course, were reflexive in the sense that they were able to analyse the role of structural inequality and power dynamics in the outcomes of the pandemic (Plummer Citation2010; Stone-Jovicich et al. Citation2018). However, only half of the EE students made the extra step of reflecting on their own positionality within the global power dynamic, acknowledging their privilege as middle-class cosmopolitan students as a first step to feeling personal and community responsibility towards effecting change. The Climate Crisis, and EE more generally, could benefit from deconstructing students’ positionality and interrelation with global systems of production, human, living and material. Perhaps an exercise like ‘writing the implosion’ (Dumit Citation2014) on the pandemic could help students through this thought process.

The supportive role of pedagogy in fostering resilience outcomes (Ban et al. Citation2015; Krasny, Lundholm, and Plummer Citation2010; Kricsfalusy, George, and Reed Citation2018) was further evidenced by the findings: the problem-based, critical pedagogies employed in the course were a factor students’ transformative experiences. However, while the transformative actions of a small group of students could be tallied as a successful outcome for the course, a large group of the 80 students who took the course were more like Gina and Sharon – keen to revert to old patterns of thought and behaviour. More needs to be done to reach those students.

One way to tackle this problem may be to further emphasize the course as an intrinsically transformative resilience-building process (Krasny Citation2020; Pihkala Citation2017; Sterling Citation2011). While maintaining the course’s normative commitment to change (Lundholm and Plummer Citation2010), students and teachers could strive to create a space where the students’ well-being and social support networks can flourish (Krasny Citation2020). Two avenues could be explored to this effect. Firstly, the final assignment could be changed from an individual essay to a group world-building project, thereby weaving individual and community resilience into students’ visions of the future. Whereas collaboration and imagination were evaluated separately in the present design of the course, they could now be evaluated together.

Secondly, the course could embed more concrete practices of being-together in the educational activities. For instance, the final workshop could be moved to a forest area of Rotterdam, led by a botanist to guide students through mindful, embodied practices for living-with the local biosphere (Chang Citation2020). Learning about environmental issues in a natural setting has been linked to the development of ‘environmental identities’, which in turn leads to greater commitment to behaviour and mindset change (Prévot, Clayton, and Mathevet Citation2018; Servant-Miklos and Noordzij Citation2021). Since the pandemic has shattered norms around learning environments, now is the time to explore alternative learning spaces and places. These are some avenues to explore for the next iteration of the EAR cycle for this course. The findings of EAR offer interesting points of transferability for environmental educators and scholars.

The contributions of this paper are both methodological and substantive, but it is important to acknowledge some of the limitations of this research. Firstly, the constraints of doing research under lockdown meant that the interview process was done online, which perhaps made interviews more formal than in a face-to-face setting. Secondly, the choice of EAR as a research method was appropriate for the particular aims of this paper, which was chiefly to improve understanding and practice around a particular educational space, but further, broader qualitative and quantitative research is much needed around the subject of the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental education and socio-ecological resilience. This particular EAR cycle was conducted from the expert insider perspective, but perhaps there is also room for EAR with the researcher as a facilitative outsider (Badger Citation2000).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic threw education into disarray around the world. Environmental science warns us that as a consequence of human impact on the biosphere, we should prepare ourselves for more and longer crises that will disrupt life as we know it. This study contributes to our understanding of how environmental education can prepare students to deal with this disruption. Pairing socio-ecological resilience with a commitment to sustainable education creates fertile ground for a paradigm shift away from an education that supports a destructive production system, towards education that opens up the cognitive, cultural, material, environmental, and social space to adapt, transform and re-build in the Anthropocene. This paradigm shift invites environmental education research to move forward into a more participatory, dynamic framework. This paper also contributes to the further development of Educational Action Research as a suitable approach to this effect. Given the extent of the environmental challenges facing the current generation of higher education students, it may be time to revisit the idea of environmental education not merely as education about or for the environment, but as part of a broader shift towards sustainable education (Sterling Citation2001) – i.e. education that can survive and thrive in the challenging decades to come.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the students and teachers of The Climate Crisis at Erasmus University College, Rotterdam. Gratitude goes out in particular to Chiara Lampis Temmink and Fei Williams for their assistance with the interviews, transcriptions, and literature review, and to Tung Tung Chan, for the feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I am reporting that I have do not have any financial and/or business interests in a company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I therefore have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Badaan, V., J. T. Jost, J. Fernando, and Y. Kashima. 2020. “Imagining Better Societies: A Social Psychological Framework for the Study of Utopian Thinking and Collective Action.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 14 (4): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12525.

- Badger, T. J. 2000. “Action Research, Change and Methodological Rigour.” Journal of Nursing Management 8 (4): 201–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2834.2000.00174.x.

- Bagci, S. C., S. Stathi, and Z. E. Piyale. 2019. “When Imagining Intergroup Contact Mobilizes Collective Action: The Perspective of Disadvantaged and Advantaged Groups.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 69: 32–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.12.003.

- Baker, C., & S. Clayton, and E. Bragg. 2021. “Educating for Resilience: Parent and Teacher Perceptions of Children’s Emotional Needs in Response to Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 27 (5): 687–705. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1828288.

- Ban, N., E. Boyd, M. Cox, C. Meek, M. Schoon, and S. Villamayor-Tomas. 2015. “Linking Classroom Learning and Research to Advance Ideas about Social-Ecological Resilience.” Ecology and Society 20 (3): 34–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07517-200335.

- Bazin, A., and C. Saintis. 2021. “Rezistans Klimatik: Building Climate Change Resilience in Haiti through Educational Radio Programming.” In Education and Climate Change: The Role of Universities, edited by F. M. Reimers, 113–136. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Bennett, E. M., G. S. Cumming, and G. D. Peterson. 2005. “A Systems Model Approach to Determining Resilience Surrogates for Case Studies.” Ecosystems 8 (8): 945–957. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-005-0141-3.

- Bernard, B. 2004. Resiliency: What We Have Learned. San Francisco: WestEd.

- Biesta, G. 1998. “Say You Want a Revolution… Suggestions for the Impossible Future of Critical Pedagogy.” Educational Theory 48 (4): 499–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.1998.00499.x.

- Bosevska, J., and J. Kriewaldt. 2020. “Fostering a Whole-School Approach to Sustainability: Learning from One School’s Journey towards Sustainable Education.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 29 (1): 55–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2019.1661127.

- Bradbury, H., R. Lewis, and D. C. Embury. 2019. “Education Action Research: With and for the Next Generation.” In The Wiley Handbook of Action Research in Education, edited by C. Mertler, 7–28. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2014. “Chapter 4: Thematic Analysis.” In Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology, edited by T. Teo, 1947–1952. New York, NY: Springer.

- Capobianco, B. M., and A. Feldman. 2006. “Promoting Quality for Teacher Action Research: Lessons Learned from Science Teachers’ Action Research.” Educational Action Research 14 (4): 497–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790600975668.

- Chang, D. 2020. “Encounters with Suchness: Contemplative Wonder in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 26 (1): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1717448.

- Collini, S. 2012. What Are Universities for? London: Penguin UK.

- Cook, T. 2009. “The Purpose of Mess in Action Research: Building Rigour Though a Messy Turn.” Educational Action Research 17 (2): 277–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790902914241.

- Cunsolo, A., and K. Landman. 2017. Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- D’Amato, L. G., and M. E. Krasny. 2011. “Outdoor Adventure Education: Applying Transformative Learning Theory to Understanding Instrumental Learning and Personal Growth in Environmental Education.” The Journal of Environmental Education 42 (4): 237–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2011.581313.

- Davenport, L. 2017. Emotional Resiliency in the Era of Climate Change: A Clinician’s Guide. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Dosemagen, D., and E. Schwalbach. 2019. “Legitimacy of and Value in Action Research.” In The Handbook of Action Research in Education, edited by C. Mertler, 161–183. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

- Dubois, B., and M. E. Krasny. 2016. “Educating with Resilience in Mind: Addressing Climate Change in post-Sandy New York City.” The Journal of Environmental Education 47 (4): 255–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2016.1167004.

- Dumit, J. 2014. “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time.” Cultural Anthropology 29 (2): 344–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.14506/ca29.2.09.

- Fazey, I., J. A. Fazey, J. Fischer, K. Sherren, J. Warren, R. F. Noss, and S. R. Dovers. 2007. “Adaptive Capacity and Learning to Learn as Leverage for Social-Ecological Resilience.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 5 (7): 375–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[375:ACALTL.2.0.CO;2]

- Fischer, M. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester, UK: Zero Books.

- Flahault, A., R. R. de Castaneda, and I. Bolon. 2016. “Climate Change and Infectious Diseases.” Public Health Reviews 37 (1): 1–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0035-2.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Gómez-Olmedo, A. M., C. Valor, and I. Carrero. 2020. “Mindfulness in Education for Sustainable Development to Nurture Socioemotional Competencies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Environmental Education Research 26 (11): 1527–1555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1777264.

- Gorji, S., and A. Gorji. 2021. “COVID-19 Pandemic: The Possible Influence of the Long-Term Ignorance about Climate Change.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 28 (13): 15575–15579.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hills, J. M., E. Μichalena, and K. J. Chalvatzis. 2018. “Innovative Technology in the Pacific: Building Resilience for Vulnerable Communities.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 129: 16–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.01.008.

- Kaukko, M., S. Kemmis, H. L. T. Heikkinen, T. Kiilakoski, and N. Haswell. 2021. “Learning to Survive Amidst Nested Crises: Can the Coronavirus Pandemic Help us Change Educational Practices to Prepare for the Impending Eco-Crisis?” Environmental Education Research 27 (11): 1559–1573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1962809.

- Kharrazi, A., S. Kudo, and D. Allasiw. 2018. “Addressing Misconceptions to the Concept of Resilience in Environmental Education.” Sustainability 10 (12): 4612–4682. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124682.

- Kimmerer, R. W. 2013. Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

- Krasny, M. E. 2020. Advancing Environmental Education Practice. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Krasny, M. E., C. Lundholm, and R. Plummer. 2010. “Resilience in Social–Ecological Systems: The Roles of Learning and Education.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5–6): 463–474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2010.505416.

- Krasny, M., C. Lundholm, and R. Plummer. 2011. Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems: The Role of Learning and Education. Adingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Krasny, M. E., and W. Roth. 2010. “Environmental Education for Social–Ecological System Resilience: A Perspective from Activity Theory.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5–6): 545–558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2010.505431.

- Kricsfalusy, V., C. George, and M. G. Reed. 2018. “Integrating Problem- and Project-Based Learning Opportunities: Assessing Outcomes of a Field Course in Environment and Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 24 (4): 593–610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1269874.

- Latour, B. 2017. Facing Gaïa: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- LeGuin, U. K. 1986. The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. London, UK: Ignota.

- Lertzman, R. 2015. Environmental Melancholia: Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement. London & New York: Routledge.

- Lipper, L., N. McCarthy, D. Zilberman, S. Asfaw, and G. Branca. 2017. Climate Smart Agriculture: building Resilience to Climate Change. New York, NY: Springer Nature.

- Lundholm, C., and R. Plummer. 2010. “Resilience and Learning: A Conspectus for Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5–6): 475–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2010.505421.

- McAteer, M. 2013. Action Research in Education. London, UK: Sage.

- McNiff, J., and J. Whitehead. 2006. All You Need to Know about Action Research: An Introduction. London, UK: Sage.

- Mertler, C. A. 2019. The Wiley Handbook of Action Research in Education. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

- Niemi, R. 2018. “Five Approaches to Pedagogical Action Research.” Education Action Research 27: 1–16.

- Ntontis, E., J. Drury, R. Amlôt, G. J. Rubin, and R. Williams. 2020. “What Lies beyond Social Capital? The Role of Social Psychology in Building Community Resilience to Climate Change.” Traumatology 26 (3): 253–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000221.

- Olin, A., G. Karlberg-Granlund, and E. M. Furu. 2016. “Facilitating Democratic Professional Development: Exploring the Double Role of Being an Academic Action Researcher.” Educational Action Research 24 (3): 424–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2016.1197141.

- Parenti, C., and J. Moore. 2015. “Anthropocene or Capitalocene?.” Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. Oakland, CA: MIT Press.

- Pihkala, P. 2017. “Environmental Education after Sustainability: Hope in the Midst of Tragedy.” Global Discourse 7 (1): 109–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2017.1300412.

- Plummer, R. 2010. “Social–Ecological Resilience and Environmental Education: Synopsis, Application, Implications.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5-6): 493–509. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2010.505423.

- Prévot, A.-C., S. Clayton, and R. Mathevet. 2018. “The Relationship of Childhood Upbringing and University Degree Program to Environmental Identity: Experience in Nature Matters.” Environmental Education Research 24 (2): 263–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1249456.

- Quay, John, Tonia Gray, Glyn Thomas, Sandy Allen-Craig, Morten Asfeldt, Soren Andkjaer, Simon Beames, et al. 2020. “What Future/s for Outdoor and Environmental Education in a World That Has Contended with COVID-19?” Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 23 (2): 93–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-020-00059-2.

- Rios, C., A. L. Neilson, and I. Menezes. 2021. “COVID-19 and the Desire of Children to Return to Nature: Emotions in the Face of Environmental and Intergenerational Injustices.” The Journal of Environmental Education 52 (5): 335–346. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2021.1981207.

- Román, D. X., M. Castro, C. Baeza, R. Knab, S. Huss-Lederman, and M. Chacon. 2021. “Resilience, Collaboration, and Agency: Galapagos Teachers Confronting the Disruption of COVID-19.” The Journal of Environmental Education 52 (5): 325–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2021.1981204.

- Rönnerman, K. 2003. “Action Research: Educational Tools and the Improvement of Practice.” Educational Action Research 11 (1): 9–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790300200206.

- Rowell, L. 2019. “Rigor in Educational Action Research and the Construction of Knowledge Democracies.” In The Wiley Handbook of Action Research in Education, edited by C. Mertler, 117–138. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

- Sarker, M. N. I., B. Yang, Y. Lv, M. E. Huq, and M. M. Kamruzzaman. 2020. “Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience through Big Data.” International Journal of Advanced Computer Science Applications 11 (3): 533–539.

- Schmeller, D. S., F. Courchamp, and G. Killeen. 2020. “Biodiversity Loss, Emerging Pathogens and Human Health Risks.” Biodiversity and Conservation 29 (11–12): 3095–3102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02021-6.

- Servant-Miklos, V., and L. Noordegraaf-Eelens. 2021. “Toward Social-Transformative Education: An Ontological Critique of Self-Directed Learning.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (2): 147–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1577284.

- Servant-Miklos, V., and G. Noordzij. 2021. “Investigating the Impact of Problem-Oriented Sustainability Education on Students’ Identity: A Comparative Study of Planning and Liberal Arts Students.” Journal of Cleaner Production 280 (2): 124846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124846.

- Servant-Miklos, V., G. R. Norman, and H. Schmidt. 2019. “A Short Intellectual History of Problem-Based Learning.” In The Wiley Handbook of Problem-Based Learning, edited by M. Moallem, W. Hung, & N. Dabbagh, 3–24. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.