Abstract

Recent decades have seen a marked growth in the quantity and range of literature reviews published on various aspects of environmental and sustainability education (ESE). However, critical assessment of these reviews suggests common challenges for authors and readers, the core of which concern distinct but related aspects of naming, assessing, and applying literature review methods. In some cases, these concerns can be traced back to matters of ‘category mistake’. Such mistakes may arise through a failure to recognise or demonstrate sufficient understanding of the differences between and suitability of literature review options, such as systematic vs. scoping reviews. In response, we contrast some of the key considerations for designing and conducting both review methods. We also draw on various protocols, checklists, and examples of reviews from the field to help readers and authors combat the likelihood of repeating a category mistake. In sum, we suggest such considerations are particularly helpful for checking when research objectives and methodological frameworks are not correctly aligned with their elected literature synthesis approach, while they may also help enhance the transparency and rigour of literature reviews and help further establish their suitability and/or usability in the field of ESE.

Introduction

Well-designed syntheses of peer-reviewed research literature that generate rigorous outcomes are indispensable to education research, practice, and policy development communities (Suri & Hattie, Citation2013). Justified appropriately and conducted successfully, such syntheses are expected to provide high-quality analysis (Gough et al., Citation2012) and create new knowledge (Suri, Citation2013). In short, such syntheses:

offer a field of inquiry enriched understandings of the breadth and depth of a knowledge base at a particular point in time (Littell et al., Citation2008),

generate ideas for (re)directing research and development activities (McMahan & McFarland, Citation2021) into the future, and

prepare the ground for further critique and innovation in research and practice by current and future generations of researchers (Harlen & Deakin Crick, Citation2004).

While knowledge syntheses in and across educational research have become increasingly significant for critically assessing claims about the state-of-the-art for particular topics and themes (Rickinson & Reid, Citation2015), they are also crucial to developing and supporting evidence-based approaches to policy and practice development (Rickinson et al., Citation2021). However, decisions about which knowledge synthesis approach to choose and why for such purposes are seldom clear cut, be that pragmatically (Cook et al., Citation2017), ethically (Suri, Citation2020) or politically (Moss, Citation2013). Indeed, although environmental and sustainability education (ESE) is still a young field with relatively low levels of funding and engagement in knowledge synthesis activities, recent contributors to the literature have advocated that ESE research and practice development stand to benefit from engaging with a wider range of approaches (e.g., Heimlich & Ardoin, Citation2008; Merritt et al., Citation2022; Thomas et al., Citation2019). A key recommendation here is that ESE researchers draw on advancements in related fields that use knowledge syntheses to drive new developments and priorities for practice.

In the first part of this article, we discuss some of the broader challenges that the work of literature review entails in education research and practice development. In the second half, we focus on the scoping review as an extended example of a knowledge synthesis option. But before proceeding, we offer a brief summary of some of the knowledge synthesis options already available, alongside existing insights and challenges. (See also Rickinson and Reid (Citation2015), Marcinkowski and Reid (Citation2019)) for summaries that have inspired many of the considerations and arguments in this article.)

By way of introduction, we suggest that these challenges might centre on researchers:

learning how to handle literature and evidence derived from diverse sources

This is because the claims about an ESE-related field of inquiry made by literature reviewers might be informed by diverse knowledge sources drawn and synthesised from a range of studies that investigate environmental, sustainability, and educational phenomena, factors, and processes (see, for example, Lingard, Citation2021). These will often require combining findings from various epistemologies and traditions of research (e.g., related to quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods). This can be challenging in and of itself, if not also having to factor in how to handle material that may be largely theoretical or conceptual in orientation at a particular phase in a field’s evolution, or in accessing databases and sources that are not in some sense familiar to the research team, e.g., from other disciplines (Suri, Citation2013).

developing approaches tailored to the conditions and state of ESE research rather than unreflexively adopting those developed for other fields of inquiry

While ESE researchers often trace their motivations for doing literature reviews to many of the advances and collaborations developed in health and medical research or to initiatives in education that support evidence-based policy and practice (e.g., Cochrane, or the EPPI-Centre discussed in Evans & Benefield, Citation2001), it remains that the fuzziness, diversity and richness of ESE research questions and inquiries can present their own challenges. On the one hand, we suggest these invite ESE researchers to consider, for example, the suitability, power and limitations of analysis and synthesis techniques and outcomes in and of themselves. While on the other, they take on more specific characteristics when selecting and ensuring a particular type of review is capable of tackling the unique features of the literature available, a specific research question, or set of research objectives and the theories that inform them (see, for example, Gough & Thomas, Citation2016, for general comments; Remmen & Iversen, Citation2022, on outdoor education; and Suri, Citation2014, on inclusive approaches).

practising intellectual virtues that include humility, flexibility and integrity

In knowledge synthesis, as with the previous points, we are often advised to avoid assuming a default ‘fitness for purpose’ for a particular way of engaging in a research literature review, and especially not for how it may be subsequently used by its readers (see Chalmers, Citation2005). If the goal is to systematically describe the literature, narrative reviews may serve this purpose well and are often technically less complex than other options. Yet that purpose might also be achieved through a rapid review, meta-analysis, or umbrella review (see Appendix 1 for a typology of main literature review options). What can be overlooked is a need to recognise the context for practising reflexivity and openness in the very acts of review and reading. This is because while different typologies are available for classifying literature reviews (e.g., Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020; Grant & Booth, Citation2009; Wollscheid & Tripney, Citation2021), we have to remain mindful that each option has corresponding implications for planning, speed, detail, risk of bias, and comprehensiveness. Thus, Chalmers invites us to heed various cautions to ensure integrity, which also include ensuring that professionalism and ethics are demonstrated such that the synthesis does not misrepresent either the ‘method’ that produced it, nor the researchers in how it is written up, read, applied or critiqued (Appendix 2).

keeping meta-level considerations in view about the contradictions and evolution of the state-of-the-art of the literature

How a particular synthesis of knowledge is evaluated and adjudicated must also be considered, if not when, where, by who and why. This is to recognise that some uses of literature review are for general purposes in contrast to those within a field or subfield, especially when ‘knowledge’ and ‘syntheses’ are sought from a range of disciplines to provide insight on a particular topic (e.g., Marcinkowski & Reid, Citation2019, on attitude-behaviour research studies and their implications for ESE). Doing so might reveal discrepancies on fundamental aspects of inquiry, such as where the weight of evidence is either argued, demonstrated or interpreted to lie, which may not actually be where it does or should (Dunkin, Citation1996; Gough, Citation2007). Thus, sometimes readers must recognise that an evidence base for a review may simply prove to be heavily limited (e.g., because of the time period, scope, sources or resources available, or purposes used to investigate a topic related, e.g., on ESE policy – see, for example, (Aikens et al. (Citation2016)). Equally, the literature base may be scant or skewed because of funding issues or the dominance of particular theories and priorities, such as when trying to illuminate implications for practice on, for example, pro-environmental values, attitudes, or behaviours, and how they do or do not connect (again, see Marcinkowski & Reid, Citation2019). Finally, perhaps it is upon reflection, that it is unclear as to exactly whose and which assumptions are being mobilised when accounting for diverse understandings of, say, the literature on agency and/or structure in ESE when constructing and communicating a review (e.g., Güler Yıldız et al., Citation2021).

appreciating that a particular technique may not yield the outcomes desired

Key tasks then for those involved in creating a knowledge synthesis include thoughtfully and transparently selecting from a range of possible assumptions, topics, sources, and approaches, alongside iteratively developing and prosecuting the research work accordingly (see Appendix 1 and Gough et al., Citation2017). Achieving this with an awareness of the key debates about particular techniques and acts of research ‘reconnaissance’ of and for a field of study is especially challenging including in relation to its development. This includes establishing and corroborating claims to the analytical power of the review at a point in time in light of the constraints on its outcomes (not just design), as well as delimiting the contexts for and relevance of its findings when drawing out implications for action—see Appendix 2 and Peters et al. (Citation2015).

Taken together, such challenges (and more besides) are emblematic of those arising from efforts to reflect on how one might aggregate, sift and communicate knowledge claims through knowledge synthesis techniques however they are framed or nuanced in practice. In short, attention must be given to how assumptions, boundaries, and ways of producing and assessing knowledge from diverse fields are practised, reinforced or transgressed.

As we argue in bridging the two parts of this article, the ideal is that the type of literature review method selected demonstrates a thoughtful and reflexive assessment of such matters. Sometimes this includes through commentary on the presence, scope, accessibility, and relevance of studies determined to be significant rather than simply relying on a ‘method recipe’ (Janesick, Citation1994). Equally, the commentary may need to be transparent about the ESE researcher’s stage, role or identity, timeframe, or funding available (see an illuminating discussion on such matters in Stevenson et al., Citation2016). Moreover, these aspects become doubly important when attempting to assay scholarly trends over time and across diverse contexts by those comparatively new to a field. Thus, it can be particularly important to acknowledge one’s experience, positionality, and biases in the team shaping the project, be they positioned as supervisors or supervisees (Nind et al., Citation2015). Doing so may surface matters such as why, when, and how individual researchers or teams conducting knowledge synthesis might appear to prefer or default to particular methods in their interpretation or enaction, or are prompted to acknowledge and account for the effects of the following:

the realities of ‘unlevel’ research fields around the world: this may include working with and across evidence or literature drawn from diverse political jurisdictions and what their associated priorities might mean for funding, interpreting, or translating research. These may be key to understanding and accounting for what may have been researched and reported or not, and thus what is visible, available, prioritised and/or constrained within the particular configuration of a research landscape by research councils and other funders or arrangements for funding research (Hammersley, Citation2020; Newman, Citation2008),

‘Anglocentricity’ and other ‘evils’: this may include the realities and challenges of linguistic and cultural assumptions embedded within privileged to marginalised ESE-related texts and text work, such as the barriers that might be experienced in translating from second to first language contexts, including among the research team (Cloete, Citation2011; Suri, Citation2017), and

questions or matters of ‘taste’: such as whether or how to acknowledge or address the ‘requisite variety’ in criteria, traditions, and understandings for what counts as evidence and/or inquiry in ESE (for a range of views, contrast Hart, Citation2000; Pawson, Citation2006; Raven, Citation2006; Shaxson & Boaz, Citation2021) that may ‘feed into’ the synthesis (or be ‘spat out’, so to speak).

This comes to matter because, as we have previously argued, one of the apparent ‘initiation rights’ to gaining and then maintaining status in an academic field is showing that one has more than a ‘passing acquaintance’ with its core literature (see Reid, Citation2016), i.e. a literature review presents an opportunity to demonstrate one’s literacy about a field to others. Next, authoring, reviewing, editing and reading journal articles might also reveal shortcomings on many of the challenges raised above (as discussed in Reid, Citation2019). Relatedly, literature reviews are often performed in the face of complex epistemological and pragmatic considerations that place a lot of responsibility on comparative novices in the field, who may reflect that they are juggling a wide range of queries and senses of the field, including during and after peer review (Rickinson, Citation2001; then compare Rickinson, Citation2003; and Rickinson, Citation2006). Indeed, it is important to acknowledge that the bulk of this synthesising work is increasingly done by or with small teams typified by those in ‘early career’, such as graduate research students and research assistants. So our opening points, coupled with the workload constraints and purposes faced by any particular researcher (alongside their supervisory and wider quality aspects) become important considerations too—and that includes in relation to matters of planning, speed, detail, risk of bias, comprehensiveness but also of capacity to choose and execute the method appropriateness for the task at hand.

With such initial observations about the work of reviewing in mind, this article’s main contribution and focus are to explore the scoping review, a relatively new approach to knowledge synthesis that is receiving growing attention in ESE research.

We write collaboratively, and our team comprises a doctoral student [Laura] working with her supervisors [Alan and Gill] as part of an ongoing project that includes producing a ‘thesis by publication’. Each author comes from a different country, disciplinary background, and a particular range of academic experience and expertise with research and reviewing the literature (see, for example, the article’s notes on contributors and our ORCID profiles). Thus, it draws on a combination of our own senses and experiences of discussions and priorities in scholarship and publication within and beyond the fields of ESE to date.Footnote1

In the next section, we start with an overview of scoping reviews and their terminologies to help identify some common and distinctive features with literature reviewing in general. We then illustrate how a scoping review compares with a systematic review as the latter is often more prominent and familiar as a technique in the field, especially among graduate students and research teams (Newman & Gough, Citation2020). This enables us to discuss key aspects of the design and prosecution of scoping reviews before we conclude with some thoughts on how they may be evaluated and developed both in and for the ESE field.

In brief, we argue that scoping reviews can offer ESE researchers a powerful method for mapping, clarifying, or summarising findings in the literature. We also argue that there are particular ways to be rigorous and transparent when practising this form of review, especially in determining the quality and value of the claims made about the field in a particular timeframe. Thus, it is in recognising the strengths and limitations of this method that we suggest special attention is given to the suitability and value of scoping reviews when presented with a choice of ways to review literature. This is because confusion about the stages, outcomes, and claims possible with a systematic vs. scoping review are often where a ‘category mistake’ emerges (Hart, Citation2018, pp. 226-228), while attending to this risk can help avoid the value of any subsequent manuscript, findings or implications being called into question.

Scoping reviews – background

In brief, a scoping review is understood here as part of a broad family of techniques for knowledge synthesis typically pursued in response to a thematic and/or evidentiary research question (Appendix 1). A scoping review may occur either as the whole of a research project or as a prelude to further inquiry (e.g., as an example of a two-stage literature review, scoping then systematic, in doctoral studies). Accordingly, a scoping review is often undertaken to generate an overview of the literature, identify knowledge gaps, and check the extent of evidence of scholarly work on emerging topics (Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020). However, rather than present a systematic review of the available peer-reviewed evidence, or limit the span of the search or analysis to that which has been published in high-quality journal archives, a key feature of a scoping review is the possibility of closer attention to both ‘grey’ and ‘white’ peer-reviewed literature in determining the parameters of and candidates for the knowledge synthesis being pursued (e.g., drawing on database holdings for research theses as a key part of the scoping process).

While such scoping reviews have become markedly popular in some quarters in the last few years—typically, in health and medical-related research (Pollock et al., Citation2021)—their purposes, features, benefits, and limitations can remain relatively unfamiliar to others including in education research as well as for ESE. Consequently, this article offers some reflections on each aspect to help further discussion and debate about the range and appropriateness of methods used in ESE research. As examples of a further range of considerations for this field see, for example, Barth and Thomas (Citation2012) and O’Flaherty and Liddy (Citation2018).

To continue, nearly a decade ago and using Cochrane and Campbell protocols as a backdrop, Colquhoun et al. (Citation2014) noted particular features to the growth patterns in health sciences scoping reviews. At the time, they also identified a lack of consensus in associated publications about the purpose and methodology of scoping reviews. While to bring insights about the patterns and delineations into conversation, they offered the following definition to clinical researchers of scoping reviews (p. 5): “A scoping review…is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesising existing knowledge.”

From our perspective and in relation to ESE research, exploratory and mapping are key to both this definition and its particular value to understanding the purpose and scope of research synthesis in any specific field (for a recent ESE-related example of its application we have been involved with, see Gutierrez-Bucheli et al., Citation2022). This is because in contrast to a systematic review that may, for example, adopt a positivistic perspective when examining the effectiveness or appropriateness of a policy, practice or initiative (Munn et al., Citation2018), a scoping review will likely take a different approach to develop understandings of a topic from a broader and iterative set of questions, that may appear eclectic or unsystematic to some. This is often the case when, for example, it becomes clear in the initial steps of the scoping exercise (e.g., from the grey literature) that there is still little known about a topic and the quality of evidence available (Colquhoun et al., Citation2014); or when the kinds of studies that have been used to examine a field or topic share little common ground (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005); or when it is unclear which theories appear or remain ‘tentative, emergent, refined, or established’ (Brunton et al., Citation2020) in the ‘finds’ due to the particular application of ‘the scope’—albeit a scoping review can be implemented in well-established areas to offer further clarity on such points.

Therefore, although Colquhoun et al. (Citation2014) noted that the number of health-related scoping reviews published since the turn of the century had increased rapidly, there can still be confusion about their purpose, scope, and methodological steps within and beyond that particular field of inquiry. By way of illustration, they noted that Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) had presented one of the first methodological frameworks for scoping studies. Yet it took almost 13 years for guidelines and checklists to articulate quality standards available for alternative forms of knowledge synthesis to systematic reviews and other forms of meta-analysis. In this, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) manual guidelines (Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020) and those for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Citation2018) have become particularly prominentFootnote2. However, while such guidelines are designed to ensure standards are followed on the quality and validity of the review findings, it remains that their audience has primarily been those working in health-related disciplines, resulting in a paucity of investigations into the case for, and use of, scoping reviews in education, including ESE.

This becomes especially significant for those investigating ESE because there are typically fewer candidates available in the literature base that afford conditions for a review that can claim to be systematic, i.e. the review study has not violated serious recommendations about agreed standards of process, evidence and degrees of interpretative freedom (Barth & Rieckmann, Citation2016). It is, therefore, incumbent upon the field’s researchers, academics and students to understand the purposes and limitations of the various literature synthesis approaches available, including which are sensible, appropriate, and feasible for the aims of an intended research project, particularly given the state and maturity of the available publications to hand.

Systematic review vs. scoping review: An introduction

As noted earlier, this article has been designed to contrast key methodological considerations that illustrate when there may be a case for following a scoping review technique rather than, say, claiming a systematic review is either happening or has taken place. In this, we note that at the time of writing, a search for “systematic review” in the journal Environmental Education Research surfaced 34 publications as compared with two using “scoping review”. However, before elaborating on why we compare these types of reviews, it is crucial we further clarify what we mean by a systematic review.

Drawing on the definition of the (then named) Cochrane CollaborationFootnote3: “A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected to minimise bias, thus providing reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made.” Here the term decision highlights one of the main primary outcomes expected of a systematic review, namely, that it can serve to inform policymakers and practitioners about the effectiveness of an intervention (Evans & Benefield, Citation2001).

We also note that like scoping reviews, systematic review approaches have become prominent as a method to address methodological and practical concerns in a wide range of clinical and medical contexts but this has been happening for much longer than for scoping reviews, i.e. since the 1970s (Munn et al., Citation2018). In this, systematic reviews have been heavily associated with pursuing a ‘what works’ agenda and following the Cochrane and Campbell protocols for evidence synthesis (Miller et al., Citation2021). In the social sciences (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2005), researchers have become more interested in recent decades in the possibilities of this type of review, as well as other types of meta-analysis, and knowledge synthesis techniques (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009), including in education (Pampaka et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, while the volume of literature syntheses has increased dramatically across diverse traditions and fields of inquiry, the range of possible approaches to developing them has grown too but not to the same extent. In some instances, some of the newer approaches to reviewing literature have led to disputes about what is well suited to systematic reviews of educational and environmental topics and queries, e.g., on class sizes (Biesta, Citation2020), the application or not of novel mapping techniques (Saran & White, Citation2018); and the capabilities required of researchers in growing their repertoire of literature review skills (Eales et al., Citation2017). Moreover, as with the challenges noted in our introductory comments, critics have noted key issues with these approaches, such as: when assessing an evidence synthesis it fails to meet agreed criteria for ‘best available evidence’ (e.g., Slavin, Citation1986); when fudging occurs over where the evidence base is uncertain, insufficient, or has gaps (e.g., given the availability, attributes, or distribution of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods used in research designs (e.g., Boaz et al., Citation2002; Higgins et al., Citation2008; Kugley et al., Citation2017)); or where other techniques are arguably better suited to generating the outcomes than the one used (e.g., Bearman et al., Citation2012; Cooper, Citation1998; Major & Savin-Baden, Citation2012).

In light of this, and as a writing team, the particulars of the authoring of the systematic reviews we have consulted in preparing this article have been of interest. We note that while they are more widely used for knowledge synthesis than scoping reviews, they can be frequently traced to ESE-related graduate student training programs, partly because they are supposed to lead to significant publishable outcomes and ensure progress towards the award of a doctorate. Nevertheless, as will be argued in the following sections, such studies during and after doctoral work may not always have been methodologically appropriate or helpful to the fields or questions of ESE research, such as when contrasted with the features of a scoping review. Indeed, among other options listed in Appendices 1 and 2, a scoping review may have proven better suited to an ESE-related research question, particularly given some of the challenges noted above.

Therefore, in this article, we have also tried to ensure we offer researchers working in ESE a basic understanding of how a scoping review may be used (see Appendix 3 and the following sections) when designing research such that it both reduces misapplication of synthesis techniques and increase the opportunities for rigour (Thomas et al., Citation2012). This is because by their very definition, scoping reviews tend to be more modest in their claims, in that they tend to establish an initial point for scoping a topic that has not been investigated in-depth (yet). Similarly, as noted above, the originality that a scoping review may offer can work well as a precursor to the more widely known systematic review, e.g., via the support of a research council grant, but the two should not be confused with the work carried out by research students as part of a project or to achieve a doctorate (Munn et al., Citation2018; Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020). This may be because a systematic approach is more likely to succeed when it is clear that the evidence base has proven robust, diverse and rich enough by ‘scoping’ it. In other words, the systematic review might be held off until it is clear that further quality evidence has become available, or can be used in high-quality as well as ethical ways to inform both practice and practice development (Rickinson & Edwards, Citation2021).

However, despite ongoing commentary and debate that clarifies the differences between scoping and systematic review in the healthcare field (e.g., Munn et al., Citation2018), there still appears to be some difficulty in identifying the main differences between both approaches, as reflected in studies with research objectives and methodological frameworks not correctly aligned with their literature synthesis approach.

To illustrate, Güler Yıldız et al. (Citation2021) have produced a systematic review of Early Childhood Education for Sustainability (ECEfS), including interventional research studies. Nevertheless, their article does not account for “their synthesis design” nor cite “methodological references” (Hong et al., Citation2017, p. 11) when drawing on qualitative and quantitative evidence and for when the reviews have to address some of the challenges this can present. Arguably, if their actual aim was to broadly summarise the practices and results of these studies, their purpose is more akin to the rationale, methodology and method more typically followed in a scoping review (Appendix 1). In contrast, Monroe et al. (Citation2019, p. 792) developed their systematic review to study climate change educational interventions with the intention of “guid(ing) educators as they continue to explore new approaches, gaps, and needs”. Arguably a limitation in this particular review concerns the lack of discussion of the possible risks associated with biased assessment of each of the studies involved. Thus, it is strongly advised that researchers aiming to undertake a synthesis or summary of existing knowledge in a literature review assess whether the purposes, range and quality of studies available are actually more suited to a scoping review or another type of systematic review. We now illustrate these and related matters in more detail:

Systematic review vs. scoping review: Similarities and differences

Although there are common methodological aspects across all types of literature review, a key consideration for researchers remains the need to assess the most appropriate literature review technique for conducting their work according to their research aims, purposes, timeframe and other pragmatic factors.

As introduced above, scoping reviews typically present a general perspective to clarify concepts and features not yet investigated in-depth for a certain topic or field. In contrast, systematic reviews evaluate the quality of the existing literature to respond to one or more specific and precise research questions (Munn et al., Citation2018). To illustrate, a meta-analysis is typically expected to review quantitative literature as its primary source, given the interest in reliability and validity and constraining their interpretations or ambiguities for health- and clinical-related settings and questions (Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020). Likewise in ESE, Miller et al. (Citation2021) conducted a systematic review that drew on meta-analysis techniques to determine the quantifiable impacts of nature-based learning regarding different learning outcomes. In contrast, those preparing a systematic review may also want to draw on qualitative evidence while conducting a meta-analysis (Liberati et al., Citation2009) or in their aggregation techniques (see Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). Although an account of these types of methods and their challenges goes beyond the scope of this article (but see Appendix 1 and 2), we note these wide-ranging approaches to systematic reviews aim to do justice to the “basis of trustworthiness” in developing practice and policies, such as in contemporary calls to develop evidence-based responses to the COVID-19 pandemic from quantitative and qualitative research (Pollock et al., Citation2021, p. 2104). As Munn et al. (Citation2018, p. 3) propose, “the provision of implications for practice is a key feature of systematic reviews.”

lists key considerations when elaborating systematic and scoping reviews based on the PRISMA statement (Liberati et al., Citation2009; Tricco et al., Citation2018). We note that if these considerations are neither engaged nor examined in the drafting of the review’s design and reporting, there could be an additional risk of the emergence of inconsistencies, incoherence, and problems in the literature reviewer’s purposes and methodology. In short, a study is done well if a thorough account of the research approach taken in a literature review is provided. It is done poorly when commentary is mainly through reference to one or a string of textbooks and manuals, or omitted entirely.

Table 1. Topics to consider for systematic and scoping reviews.

Thus, to avoid methodological biases and inconsistencies, researchers might work with such guidelines to enhance the research strategies used in particular forms of literature review, be that in developing them or critically reading or applying their findings and implications (see examples cited in the last row of ). The following sections will now describe a series of key steps for scoping reviews based on specific guidelines and examples.

Scoping review – key steps

The key steps to a scoping review described in the following sections are largely based on the guidance document provided by JBIFootnote4 (Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020) and the reporting guideline elaborated by Tricco et al. (Citation2018) as a PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (i.e. PRISMA-ScR). We combine these two sources due to their international relevance and popularity since Cochrane and JBI emerged in 1990s (Munn et al., Citation2018).

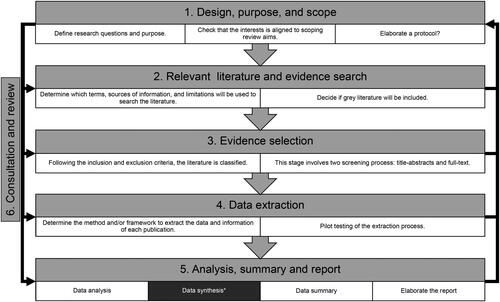

In brief, JBI offers a manual and PRISMA a checklist which when taken together, serve to enhance considerations of any methodological framework and corresponding stages that might be considered when undertaking a literature review rather than using one source or the other. Thus, the methods described in the following section synthesise and summarise the steps to develop a scoping review, based on JBI and PRISMA-ScR (see and Appendix 3).

Figure 1. Critical steps for scoping reviews.

Note: * to indicate this step is often underdeveloped in the guidance and practice of scoping reviews.

While JBI guidelines and PRISMA-ScR divide the scoping review process into nine steps, the initial versions (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010) aggregated these steps into six stages. Therefore, the steps presented in have been blended together from both sources to ensure the same number across both protocols. The focus and number of steps have been verified for their comprehensiveness against the initial version presented by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), a subsequent overview of this framework (Levac et al., Citation2010), the current scoping review guidelines (Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020; Tricco et al., Citation2018), and examples of scoping reviews in ESE (see Berchin et al., Citation2021; Derr & Simons, Citation2020; Gutierrez-Bucheli et al., Citation2022).

Scoping reviews as a research approach for knowledge reviews

As shown in , the steps for developing and conducting a scoping review presented in this article are sequenced into six aspects that have channels for feedback and feedforward. The six aspects relate to: 1) Design, purpose, and scope, 2) Relevant literature and evidence search, 3) Evidence selection, 4) Data extraction, 5) Summary and report, and 6) Consultation and review.

Design, purpose, and scope

Design, purpose, and scope are the initial aspects for consideration, and as such, are arguably the most important stage in a scoping review. If this ‘platform’ for proceeding is successfully elaborated, the risks of inconsistency between research objective(s) and review type selected are drastically reduced.

Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005, p. 23) recommended that it is essential that the research question incorporates details about “the study population, interventions or outcomes” that will determine the scope of which topics will be studied (see and Appendix 4). As an example, describes three scoping reviews that focus on ESE topics, study the literature available on a particular topic, and generate an overview of current knowledge and trends in research question(s), methods, and findings. Likewise, following Rickinson and Reid’s (Citation2015) example, we have proposed a list of ESE topics and areas that could guide future research questions of scoping reviews based on research synthesis (see Appendix 4).

Table 2. Examples of research questions of scoping reviews elaborated in ESE.

The details about the population (P), concept (C), and context (C) presented in the research question(s) will spawn the constraints that must be considered in subsequent stages (e.g., evidence search and selection criteria). For this reason, we have included iterative arrows in because researchers will typically corroborate that the research question(s) remain aligned with the methodological decisions as they proceed through each stage of the process (Daudt et al., Citation2013). If they are do not align, researchers might then consider adjusting their research question(s).

The conclusion we draw from these considerations is to recommend that researchers clearly specify and reflect on the research question(s) to be used in their literature review, factoring in the key expected outcomes and options related to furthering those. This helps ward off any tendency in ESE research to disregard the importance of this step, such as risk claiming to have conducted a systematic review when perhaps a scoping review may be more suited to the questions identified. In other words, research teams—and especially graduate students—should be cautious because, on the one hand, lead researchers should be committed to ensuring that the research question remains as comprehensive and manageable as possible to afford significant coverage and thus fulfil the very terms of a ‘scoping’ review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). On the other, before delimiting a review inadvertently or too hastily, researchers do well to maintain attention on the specific purpose when conceptualising and designing their research question(s) and thus, establishing what is in and out of scope (Levac et al., Citation2010). Accordingly, researchers might cross-check their scope with the following aims ascribed to such reviews, as suggested by Peters, Godfrey, et al. (Citation2020):

As a precursor to a systematic review, [a scoping review can be used] to identify the types of available evidence in a given field, to identify and analyse knowledge gaps, to clarify key concepts/definitions in the literature, to examine how research is conducted on a certain topic or field, (and) to identify key characteristics or factors related to a concept.

In short, the design, purpose, and scope aspects equate to considering the rationale in for the PRISMA protocol (Tricco et al., Citation2018). If the scope delimited by the research question(s) does not match the scoping review’s purposes, researchers should consider changing the literature synthesis approach.

It is important then to remember that one of the main aims of a scoping review is to study the currently available evidence in a field and identify the nature and spectrum of this evidence to determine knowledge gaps and thus advise future research. However, in scoping reviews these are indexed to the types of evidence and key features and characteristics, such as research methods, stakeholders involved, and area of intervention (Munn et al., Citation2018). Therefore, scoping reviews do not commonly require a critical appraisal (e.g., risk of bias assessment) of evidence because they do not seek to give insight into practice and policy decisions based on evidence-based research—aspects more typical of a systematic review (see and Pollock et al., Citation2021). Therefore, to avoid methodological inconsistencies, a key step is to identify the purpose and scope that will delimit a scoping review’s research question(s).

Before advancing to the next aspects, a further substep might also be considered: elaborating the review protocol (see, e.g., Casey et al., Citation2021). A protocol “provides the plan or proposal for the systematic review and as such is important in restricting the presence of reporting bias” (Munn et al., Citation2020). While a protocol is commonly elaborated in a systematic review, only a few reports have recognised this step’s importance for scoping reviews, and for their readers (Pollock et al., Citation2021). Protocols for a scoping review can be logged (e.g., at PROSPERO, see footnote 2) or published, e.g., on Fig Share, Web of Science, ResearchGate, or Research Square (Peters, Marnie, et al., Citation2020; Pollock et al., Citation2021). Although a review protocol is not commonly required in ESE journals or as an article’s supplementary material, for example, it is recommended that researchers prepare a protocol before undertaking a complete scoping review to reduce ad-hoc decisions (Pollock et al., Citation2021). Lodging it in a register of scoping reviews can also afford further inspection, reuse and/or adaption in follow-up researchFootnote5. Equally, other types of reviews could be considered in their own right or as a precursor to a systematic review. For instance, mapping reviews (Saran & White, Citation2018) could be undertaken as the first step of a systematic review, the primary outcome of which is the creation of visual synthesis (see Appendix 1).

Relevant literature and evidence search

The search for evidence in a scoping review is intended to identify scholarly studies and publications whose findings can be brought to bear on the research question(s). Sound advice generally recommends researchers define the search strategies following a protocol or plan that aligns with the scope established in the previous step (Peters, Marnie, et al., Citation2020). These strategies might include, but are not limited to the identification of sources, search terms, and limitations (e.g., by timeframe, language, a threshold number of citations). Crucial to this step (but it appears, often skipped) is researchers consulting with a research librarian to determine the most relevant databases in the field, the correct designation of search terms (including truncations, synonyms or wildcards), particularly if they are relatively new to the topic area or the supervisor cannot provide this advice (see, e.g., Derr & Simons, Citation2020). The reliability of the search terms can also be sense-checked and evaluated by a subject matter expert (consistent with consultation strategies evaluated in stage 6—Consultation and review), or by using text mining of the selected studies to determine if these terms align with the research question(s), keywords and scope of the scoping review, or by citation analysis (e.g., Gutierrez-Bucheli et al., Citation2022).

As noted in the previous step, a key recommendation for this stage of a scoping review is that researchers describe in detail the search strategy. This typically involves detailing information about the limitations used per database and the most recent date when the search was undertaken (Tricco et al., Citation2018). For instance, in elaborating the features of a literature review of policy research in ESE studies, Aikens et al. (Citation2016) described the text-based search terms inputted into the portals selected. However, while not positioned as a scoping review, as with other common literature review expectations, their report did not specify what process was followed to identify what were deemed irrelevant articles to their research question(s). We note it is recommended that for ease of reference, literature reviewers in scoping and systematic reviews state the in/eligibility criteria from the beginning, together with key process considerations for each screening, incorporating the information about how the evidence was sourced and selected (cf. Briggs et al., Citation2018).

A related critical consideration at this stage is the constant monitoring of comprehensiveness and feasibility in a scoping review (Levac et al., Citation2010). Researchers are encouraged to log and justify all the decisions related to the evidence search, including its limitations. For instance, for scoping reviews, researchers should openly evaluate the value of incorporating elements of the grey literature (Levac et al., Citation2010) or reports in multilingual databases. These are important aspects to consider as the scoping review will often incorporate different types of evidence (Peters, Marnie, et al., Citation2020). In young and diverse fields like ESE, grey literature and from multiple language bases could be especially relevant to exploring contexts or settings where peer-review publications are restricted and to address biases towards particular expectations, genres, regions, biomes, cultures, or traditions in research, e.g., to de-colonise or de-anthropocentricise engagements with the research literature (Briggs et al., Citation2018; Lotz-Sisitka, Citation2009; Van Den Hoven, 2019). Therefore, while we might set aside the wider debate about what constitutes grey literature or not (see, for example, Mahood et al., Citation2014), ESE researchers might still evaluate the advantages of including dissertations, conference proceedings, reports, book chapters, among others, that meet quality thresholds but also further aspects of representation and redress marginalisation in an international and internationalised field. The range of sources for grey literature is vast, from Google Scholar to online databases (see Mahood et al., Citation2014), and online translation software can reduce some structural barriers here. Likewise, researchers could consider the benefits of involving other search strategies, quality and member checks such as ‘snowballing’, reference and citation tracking, or personal knowledge and suggestions (Greenhalgh & Peacock, Citation2005) using globalised reference, critical friend or affinity groups. However, despite these possibilities and goals, it is worth noting again that regardless of the source or steps taken, all decisions should be stated and justified by researchers in the scoping review report, especially regarding source provenance and quality.

Evidence selection

Steps in selecting from the evidence to determine the relevance of studies to a scoping review that address the research question(s) can take a range of forms. As noted above, such steps are often a consequence of the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined in the protocol or plan aligned to the research question(s). For example, in the scoping review on healthcare elaborated by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005, p. 26), the inclusion criteria were “related to the: type of study; type of intervention; care recipient group; and carer group”. offers examples of inclusion and exclusion criteria used in ESE scoping reviews. As can be observed, these criteria should align to the scope and purpose of the scoping review, and will typically describe eligible ‘participants’, concepts, and contexts for the review (Peters, Marnie, et al., Citation2020). This critical step aligns with Dunkin’s (Citation1996) suggestion, highlighting that the exclusion process should be meticulous in reducing the likelihood of misrepresentation, misattribution and biases in accounts of “the state of knowledge in the field”.

Table 3. Examples of inclusion and exclusion criteria used in ESE scoping reviews.

Thus, the main priority in this stage of a scoping review is to sift the material’s relevance (and exclude the irrelevant) in creating both the corpus and margins of the scoping review. The process customarily involves: (a) reading the title, abstract, and keywords of all studies obtained from the previous stage, followed by (b) the full-text screening of the studies obtained from the initial screening.

Recommendations on the practicalities include ensuring that the results of this process are documented in a flowchart, such as by following and populating that shown in PRISMA-ScR (Tricco et al., Citation2018). Levac et al. (Citation2010) have recommended that this activity could be enhanced if it is done by multidisciplinary teams when determining if a study should be included or excluded, not just simply based on the lone reviewer (or for that matter, validations of their supervisor). Appendix 2 lists recommendations regarding the number of reviewers recommended for each literature review type. Additionally, specialist software for literature reviews to facilitate the management of references and analysis and synthesis of literature between a team is now widely available, e.g., EPPI-Reviewer or CovidenceFootnote6.

Data extraction

Extraction of the data from the selected studies will then enable the elaboration of the scoping review findingsFootnote7. As before, it should be clear to the author and reader that the extraction process has aligned with the terms defined in the protocol and plan, which has also been determined to be appropriate for addressing the research question(s) and can then be defensible beyond the research team, e.g., in a public research forum such as to a project reference group or in a research journal (Levac et al., Citation2010).

Pollock et al. (Citation2021, p. 2109) suggest that an extraction framework includes “a standardised extraction form” with the information to be extracted from the evidence. For instance, Berchin et al. (Citation2021, p. 4) charted the data in tables according to the type of ESE initiatives elaborated in higher education institutions and the “year, publication title, authors, journal and number of citations on Google Scholar”.

However, before proceeding with extraction, an important second consideration is the value of pilot testing the standardised extraction procedure (Pollock et al., Citation2021). Thus, it is widely recommended that before charting all the studies, researchers test the charting framework with two or three studies and evaluate if more information is required or they need to revisit earlier steps, e.g., the scoping criteria and what counts as relevant literature (e.g., Peters, Marnie, et al., Citation2020). We note that in practice, this process is usually iterative because it requires that the researchers demonstrate familiarity with the extent and quality of the evidence, which might also suggest further tweaking of the research question and scope of the search. For instance, after reading several studies related to engineering education for sustainable development, Gutierrez-Bucheli et al. (Citation2022) realised that the extraction protocol needed recalibrating. This was to ensure it surfaced examples of collaborations and partnerships between institutions as these typically yielded evidence that offered more explanatory insight into understanding the maturation and advancement of such educational initiatives than those studies that reported on individual institutions alone.

Analysis, summary, and report

At the end of the preceding stage, the charting table or form is expected to contain data from all the relevant studies to facilitate the analysis process that follows. This next aspect typically involves iterative ‘substeps’ and ‘subroutines’ of data summary, data analysis, data synthesis, and data reporting that flesh out the methods and priorities established in the protocol or plan. As stated previously, the main objective of this stage of a scoping review is to map, précis and distil the data extracted in the previous stage. For instance, this might be visualised in charts to show the distribution of evidence in publications per year and by location (Gutierrez-Bucheli et al., Citation2022) or in tables to report the participants, intervention, research methods and evidence types (Derr & Simons, Citation2020).

Although some medical and health research researchers argue that scoping reviews do not synthesise results (Pollock et al., Citation2021), it can still seem unclear how main gaps or trends in the literature are identified in scoping reviews. Indeed, we believe a synthesising step is critical to enhancing the reliability of the conclusions without getting overwhelmed by calculating effect sizes, for example, which may be more typically expected of a systematic review (Hammersley, Citation2020). Therefore, we have assigned a dark colour to data synthesis in to highlight this step may not be appropriately defined or practised. As mentioned above, in addressing this, we also encourage educational researchers to be open to other options and take advantage of the flexibility offered by scoping reviews and other types of reviews. The data analysis in a scoping review is usually limited by the deliberate intention of providing a mapping via descriptive qualitative analysis techniques, and that is does not have to go beyond this (Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020). This is critical in research about education because knowledge syntheses could be addressing concerns of a complex and shifting nature which require, in some circumstances, a mix of different review methods to adequately capture and represent these features (Gough & Thomas, Citation2016). For example, once Gutierrez-Bucheli et al. (Citation2022) determined the spectrum of educational strategies and methodologies used worldwide in engineering education for sustainability, they applied techniques from realist synthesis to flesh out the scoping review (Evald, Citation2018). This was to ensure that the scoping review could account for how particular educational mechanisms ‘worked’ to generate certain learning outcomes in different contexts (see also Wong et al. (Citation2013), and Appendix 1 and 2 on key features of realist reviews).

The essential communicative point then of an analysis and synthesis stage is exemplifying the very terms of a scoping review. As such, it is vital to remember that some authorities argue that a scoping review does not have to assess the quality of the evidence (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005), but this is where confusion about methods might occur (see considerations of critical appraisal listed in ). Notably, systematic reviews of qualitative evidence should discuss the degree of confidence possible or strength of the evidence in addition to any limitation (Lockwood et al., Citation2020). Yet it would not be too far off the mark to claim that some systematic reviews in ESE research fail to describe the quality of evidence, synthesis method, interpretative approach, and/or search limitations. Thus, in agreement with Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), who suggest that in determining the scope of a systematic review, researchers should clarify how they prioritise the most important data to collate and summarise the evidence, we too would encourage authors to offer a quality check of the evidence that is included or omitted to help confirm the rigour of the search and review. We note Derr and Simons (Citation2020) elaborated such a process prioritising the research approach of the evidence related to photovoice in environment and conservation contexts. Similarly, Berchin et al. (Citation2021) reviewed the quality and extent of evidence according to ESE initiatives promoted in higher education institutions.

Finally, it is often suggested that the authors of the final report of the knowledge synthesis elaborate a narrative summary where progress towards ‘answering’ each research question is reviewed, and the limitations of the scoping review are acknowledged and presented. This is to ensure that when describing how a scoping review’s findings may or may not have implications for the current literature, policy, and practice (Levac et al., Citation2010; Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020) the final report can ground these with close attention to insider and outsider perspectives on the findings rather than by way of recourse, for example, to post hoc or ad hoc criteria which were not part of the review protocol.

Consultation and review

Despite the numbering of stages and steps in our overview of ways to conduct a scoping review, this is usually not the final stage as ‘best practice considerations’ would suggest it is expected to take place in parallel to the preceding steps we have outlined. This is because consultation can help with sense-checking, combat groupthink, and test out whether different perspectives, interpretations or debates have been considered in ensuring consistency between research objective(s) and methodological decisions. A multi-perspective approach is particularly helpful in ESE literature reviews when considering different viewpoints that could influence the methodological strategies defined in a scoping review, or the outcomes or implications discerned. We note this stage is not yet seen as mandatory; however, the consultation of experts throughout the process is recommended to ensure rigour (and not only at the refereeing stage of a publication, for example).

Consultation may have multiple aims, such as to: (a) consider different perspectives that could enhance the analysis, (b) check the review is not drifting into another mode or technique (Appendix 1), and (c) to trial and ensure effective communication of the findings. We note, as Levac et al. (Citation2010, p. 7) argue, researchers are encouraged to “clearly articulate the type of stakeholders with whom they wish to consult, how they will collect the data (e.g., focus groups, interviews, surveys), and how these data will be analysed, reported, and integrated within the overall study outcome”. As an example, experts could be consulted to identify or include additional relevant studies (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005) from the grey literature that a database or search engine may not have surfaced, to access or audit preliminary studies, or to prepare methods of communication and dissemination (Levac et al., Citation2010). Again, the researchers are encouraged to justify their decisions and actions in this regard, when documenting the consultation process that did or did not take place.

In the case of early career or unfamiliar researchers with scoping reviews, it is widely recommended that this consultation starts from the planning stage, where researchers will be expected to select the best type of literature review that serves the review’s purpose, particularly if they do not know the strengths, limitations or implications of available literature review approaches (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). Likewise, this step will allow all participating researchers to consider the value of protocols and standards. For example, a sound reason for not offering implications in a scoping review is when authors have shown they have wrestled with incompatible epistemological and methodological bases for knowledge synthesis such that they cannot draw out sound or defensible implications (this is in contrast to, for example, providing a badly organised paper that does not make space for this). As argued above, when systematic reviews in education mainly follow a positivist perspective to evaluate ‘what works’ in policy, practice or paradigm, there is a significant risk of conceiving of education from an instrumentalist perspective, such that implications for teaching and learning are approached in ways that ‘read off’ best practices from a select set of studies on the assumption that their adoption can ensure certain outcomes or competencies (Rickinson & Reid, Citation2015). We trust the same risk is avoided in scoping reviews by being explicit about quality, inclusion and exclusion, and this can be readily achieved through the continuous consultation of experts (e.g., critical friends, supervisors, examiners, or reference groups) throughout the review process to help ensure transparency in reporting the results of a scoping review. As noted above, while Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) have advocated that researchers should prioritise the most important data to collate in a scoping review, consultation can help ensure that it is aligned to the review’s research question(s) and what researchers decide is ‘relevant’ (Gough, Citation2007) is tested, defensible and clear to others.

Conclusions

In this article, we have illustrated how researchers might consider a wide range of options and considerations available to them when designing, conducting, and evaluating literature reviews. While we encourage education researchers to be open and flexible to the strengths and limitations offered by each review type and the typical sources of these options, we suggest that researchers also do well to revisit recent debates and their legacies on literature review design and practices in education research (e.g., Maxwell, Citation2006). These recommendations are often especially geared towards doctoral students and studies where the likelihood of methodological inconsistencies and category mistakes are arguably higher for a knowledge synthesis when, for example, the research student or supervisor is not familiar with the kinds of principles, stages or challenges we have discussed here. We also agree with Boote and Beile (Citation2005) who suggest that doctoral programs should have formal workshops where students can strengthen their capabilities and decision-making skills about literature review techniques, as well as take part in opportunities to test out their argumentative and systematic skills when considering undertaking a knowledge synthesis, e.g., workshops and seminars about searches through to reporting.

While in general terms literature reviews are often undertaken to appraise what is currently known and thus unknown about a field to direct future research, we also recognise that the research objectives of literature reviews in ESE are diverse and remain to some degree, provisional. For example, recent literature reviews in ESE have focused on disseminating initiatives developed in higher education institutions to promote sustainable development (Berchin et al., Citation2021) or understanding how particular research methods (i.e. photovoice) have been used in different contextual settings (Derr & Simons, Citation2020). Yet neither study could have happened decades ago, or is expected to remain authoritative for decades to come. However, we note that in some instances, ESE researchers have tended to directly appeal to ‘systematic review’ as if this is the gold standard and most suitable approach to the exclusion of many viable and useful alternatives for their projects. We have outlined the key features of leading contenders (Appendix 2), and we trust this can serve as a guide for ESE researcher choices too.

In summary, as scoping reviews are well suited to nascent research fields with diverse and often patchy forms of evidence (Tricco et al., Citation2018), how we frame and prosecute literature reviews may merit further consideration for ESE topics. Since their conception, scoping reviews have been mainly recommended for projects that seek to analyse and map the terrain of the current literature on a specific topic, rather than trace out what has been found along the way more systematically in journeys through a particular landscape (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Thus, a scoping review is well suited to understanding and explaining an emerging field’s or topic’s characteristics, nature, or diversity, rather than an established one that is suited to more systematic analysis.

As outlined above, when developing a scoping review, the planning stage is perhaps the most crucial in the process due to the need to ensure the quality and rigour of what ensues. We invite novice or junior researchers undertaking a literature review to work collaboratively with their supervisors to ensure they understand the review options available, assess previous reviews critically, and avoid repeating any of the mistakes other reviews may have made even if they are held up as exemplars. We especially recommend that during the planning stage, researchers cross-check their intentions and capacities with agreed purposes of scoping reviews (e.g., consult ) because, as shown with examples drawn from Environmental Education Research, there can be several and severe inconsistencies in argumentation and execution. A key concern is confusion or misrepresentation between systematic and scoping reviews, including when it comes to how much narrative, assessment of the quality of evidence, and systematicity are typically expected (see also Appendix 1 and 2).

Similarly, we strongly encourage all the steps and stages to be elaborated and discussed in relation to agreed standards or recommendations for a scoping review process, and that these are then carefully applied when justifying and accounting for decisions and activities throughout the review project. On the one hand, this should help reduce methodological inconsistencies and the likelihood of category mistakes such as when researchers do not consider a fuller range of options (or confuse one approach with another), or when the suitability of that which is chosen does not align with what’s possible or sensible for their literature review and the literature currently available. On the other hand, such considerations should spur better quality and more trustworthy literature reviews being developed and published, especially if assessments of evidence about and implications for the field remain both a priority and touchstone for establishing progress and further research needs.

Finally, we believe that further work on literature review goals and techniques is required to identify, explore and demonstrate the boundaries and productive crossovers and combinations of each literature review type in the ESE field. In the case of scoping reviews, possibilities include exploring how to enhance and clarify the synthesis step as a standalone literature review, or in relation to other forms, or indeed, other forms of research and research communication, e.g., in advancing eeWORKS-type projects (see, for example, Ardoin & Bowers, Citation2020; Ardoin et al., Citation2020; Plate et al., Citation2020). Thus, we conclude by also encouraging researchers in ESE to undertake literature reviews that give rise to methodological investigations and experiments, e.g., on whether ‘less anthropocentric’ methods might be developed or encouraged, and how multi- or mixed methods to literature reviewing might be developed further.

Authorship contribution statement

Laura Gutierrez-Bucheli (50%): Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, resources, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing and visualisation.

Alan Reid (45%): Conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, supervision, and project administration.

Gillian Kidman (5%): Writing-review & editing and supervision.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the Faculty of Education and Monash University for promoting transdisciplinary research about sustainability and education. The authors would like to thank the Editor of Environmental Education Research and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and efforts towards improving the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura Gutierrez-Bucheli

Laura Gutierrez-Bucheli: is a doctoral student at the Faculty of Education, Monash University, originally from Colombia, with a background in civil engineering and construction management. Parallel to her studies, she works as a research assistant and teaching associate in the future building initiative at Monash Art, Design and Architecture and the Faculty of Engineering. Her research interests are sustainability education, engineering education, and construction management.

Alan Reid

Alan Reid: is a Professor at the Faculty of Education, Monash University. He is Editor-in-Chief of the international research journal, Environmental Education Research, and publishes regularly on environmental and sustainability education (ESE) and their research primarily in ‘Anglo’ contexts. Alan’s interests in research and service focus on growing associated traditions, capacities and the impact of ESE research. A key vehicle for this is his work with the Global Environmental Education Partnership, and via eePRO Research and Evaluation. Find out more via social media, pages or tags for eerjournal.

Gillian Kidman

Gillian Kidman: is an Associate Professor of Science Education in the Faculty of Education, Monash University, Australia. She is the Chief Editor of the International Journal of Geographical and Environmental Education and is a member of the IGU’s Steering Committee for its Commission on Geographical Education. Her main research interests relate to interdisciplinary education and curriculum design, specialising in STEM Education using sustainability concepts and contexts. Gill works extensively in STEM education with South East Asian Ministries of Education and the Regional Education Centre of Science and Mathematics (RECSAM) in Penang, Malaysia.

Notes

1 We also hope the article moves some of our previously discussed considerations forward, particularly in relation to how we might identify some of the ‘blank, blind, bald, and bright spots’ of research that are produced by the use, misuse, or non-use of certain research methods Reid, A. (2019). Blank, blind, bald and bright spots in environmental education research. Environmental Education Research, 25(2), 157-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1615735.

2 Other examples of field specific protocols include: ROSES—RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses in environmental research (https://www.roses-reporting.com), a “a collaborative initiative with the aim of improving the standards of reporting in evidence syntheses in the field of environment,” while the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, UK, host PROSPERO, an international prospective register of systematic reviews, rapid reviews and umbrella reviews.

3 Cochrane (previously the Cochrane Collaboration) (https://www.cochrane.org/) is an international charitable organisation that organises health and medical-related systematic reviews intended to support evidence-based choices. See Gough, D., & Thomas, J. (2016). Systematic reviews of research in education: aims, myths and multiple methods. Review of Education, 4(1), 84-102. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3068

4 JBI is constantly updating their methodological recommendations for scoping reviews – from 2015 (https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Scoping-.pdf) until now (https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/3283910770/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews). The version used should be specified where possible.

5 A review protocol in a scoping review will describe the strategies for evidence search, selecting the evidence (e.g., inclusion and exclusion criteria) and data extraction to ensure the scoping review is as comprehensive as possible (see Peters, Godfrey, et al., Citation2020 for more details about scoping review protocols).

6 Summaries of software options are widely available, e.g., at https://utas.libguides.com/SystematicReviews/Tools

7 It is recommended that researchers evaluate the advantages of using a software for the data extraction process such as Excel or NVivo (https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/resources/blog/extending-your-literature-review-nvivo-12-plus)

References

- Aikens, K., M. McKenzie, and P. Vaughter. 2016. “Environmental and Sustainability Education Policy Research: A Systematic Review of Methodological and Thematic Trends.” Environmental Education Research 22 (3): 333–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1135418.

- Ardoin, N. M., and A. W. Bowers. 2020. “Early Childhood Environmental Education: A Systematic Review of the Research Literature.” Educational Research Review 31: 100353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100353.

- Ardoin, N. M., A. W. Bowers, and E. Gaillard. 2020. “Environmental Education Outcomes for Conservation: A Systematic Review.” Biological Conservation 241: 108224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224.

- Ardoin, N. M., C. Clark, and E. Kelsey. 2013. “An Exploration of Future Trends in Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 19 (4): 499–520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.709823.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Aromataris, E., and Z. Munn. 2020. “Chapter 1: JBI Systematic Reviews.” In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, edited by E. Aromataris and Z. Munn. JBI. doi:https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-02.

- Barnett-Page, E., and J. Thomas. 2009. “Methods for the Synthesis of Qualitative Research: A Critical Review.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 9 (1): 59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59.

- Barth, M., and M. Rieckmann. 2016. “State of the Art in Research on Higher Education for Sustainable Development.” In Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development, edited by M. Barth, G. Michelsen, M. Rieckmann, and I. Thomas, 100–113. London: Routledge.

- Barth, M., and I. Thomas. 2012. “Synthesising Case-Study Research – Ready for the Next Step?” Environmental Education Research 18 (6): 751–764. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.665849.

- Bearman, M., C. D. Smith, A. Carbone, S. Slade, C. Baik, M. Hughes-Warrington, and D. L. Neumann. 2012. “Systematic Review Methodology in Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (5): 625–640. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.702735.

- Berchin, I. I., A. R. Aguiar Dutra, and J. B. S. O. d Guerra. 2021. “How Do Higher Education Institutions Promote Sustainable Development? A Literature Review.” Sustainable Development (Bradford, West Yorkshire, England) 29 (6): 1204–1222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2219.

- Biesta, G. 2020. Educational Research: An Unorthodox Introduction. London: Bloomsbury.

- Boaz, A., D. Ashby, and K. Young. 2002. Systematic Reviews: what Have They Got to Offer Evidence Based Policy and Practice? London: ESRC UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice London.

- Boote, D. N., and P. Beile. 2005. “Scholars before Researchers: On the Centrality of the Dissertation Literature Review in Research Preparation.” Educational Researcher 34 (6): 3–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034006003.

- Briggs, L., N. M. Trautmann, and C. Fournier. 2018. “Environmental Education in Latin American and the Caribbean: The Challenges and Limitations of Conducting a Systematic Review of Evaluation and Research.” Environmental Education Research 24 (12): 1631–1654. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1499015.

- Brunton, G., S. Oliver, and J. Thomas. 2020. “Innovations in Framework Synthesis as a Systematic Review Method.” Research Synthesis Methods 11 (3): 316–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1399.

- Casey, M., D. Coghlan, Á. Carroll, D. Stokes, K. Roberts, and G. Hynes. 2021. “Application of Action Research in the Field of Healthcare: A Scoping Review Protocol.” HRB Open Research 4: 46. doi:https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13276.2.

- Chalmers, I. 2005. “If Evidence-Informed Policy Works in Practice, Does It Matter If It Doesn’t Work in Theory? Evidence & Policy: A.” Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 1 (2): 227–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/1744264053730806.

- Clark, C. R., J. E. Heimlich, N. M. Ardoin, and J. Braus. 2020. “Using a Delphi Study to Clarify the Landscape and Core Outcomes in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 26 (3): 381–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1727859.

- Cloete, E. L. 2011. “Going to the Bush: Language, Power and the Conserved Environment in Southern Africa.” Environmental Education Research 17 (1): 35–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504621003625248.

- Colquhoun, H. L., D. Levac, K. K. O’Brien, S. Straus, A. C. Tricco, L. Perrier, M. Kastner, and D. Moher. 2014. “Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67 (12): 1291–1294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

- Cook, C. N., S. J. Nichols, J. A. Webb, R. A. Fuller, and R. M. Richards. 2017. “Simplifying the Selection of Evidence Synthesis Methods to Inform Environmental Decisions: A Guide for Decision Makers and Scientists.” Biological Conservation 213: 135–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.07.004.

- Cooper, H. M. 1998. Synthesizing Research: A Guide for Literature Reviews. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Daudt, H. M., C. Van Mossel, and S. J. Scott. 2013. “Enhancing the Scoping Study Methodology: A Large, Inter-Professional Team’s Experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 13 (1): 48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48.