Abstract

The roots and goals of outdoor education (OE) in Canada are often linked to the Canadian summer camp tradition that emerged in the early 1900s which centered around character development, and the environmental movement of the 1950s and 1960s. However, a comprehensive understanding of the philosophies, goals, and activities of modern Canadian OE K-12 programs is unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify the underlying philosophies, learning goals, and activities of K-12 OE programs in Canada. Using a descriptive research design, we conducted a web-based survey consisting of closed-and open-ended questions of 100 K-12 programs across Canada. Our findings indicate the programs are grounded in hands-on experiential learning that is holistic and integrates knowledge from a variety of disciplines. Primary learning goals include personal growth, community building, environmental stewardship, and people and place consciousness. OE activities varied but commonly included basic outdoor skills that can be practiced regardless of seasons. Implications for K-12 programming are discussed.

Introduction

While the summer camp tradition that emerged in the early 1900s and focused on character development may have been the origin of outdoor education (OE) in Canada (Dimock & Hendry, Citation1929; Wall, Citation2009), OE first appeared in Canadian K-12 public schools in the 1950s in response to the growing environmental movement (Passmore, Citation1972). Since then, OE has expanded to include a broad range of activities, learning objectives, and is driven by various educational philosophies (Asfeldt et al., Citation2020). However, the last study to examine OE activities, learning goals, and philosophies in Canadian public schools was conducted nearly 50 years ago (Passmore, Citation1972). In an era of increasing concern regarding climate-change, reconciliation, and the ongoing task of improving public education in Canada, our study aims to understand why and how OE is being delivered to children and youth in Canadian public schools. An additional goal is to identify and provide a foundation for further critical inquiry of OE in Canada.

The precise definition of OE is contested among scholars (Dyment & Potter, Citation2015; Nicol, Citation2002; Wattchow & Brown, Citation2011) and tends to focus on debating whether OE is a method of teaching or a subject area (Quay & Seaman, Citation2013). For the exploratory purpose of this study, we adopt a broad definition of OE guided by Henderson and Potter’s (Citation2001) notion that OE in Canada is a form of organized learning that takes place outdoors. Specifically, Henderson and Potter write that OE is an “overarching curricular enriching education in the outdoors that include both environmental and adventure education” (69). Generally, environmental education aims to enhance knowledge about ecosystems and how humans interact with those ecosystems while adventure education is focused on developing personal and social skills.

As the international OE community has no definitive definition of OE, it is not surprising that there is no one definition for OE in the Canadian K-12 context, especially considering education is a provincial and territorial responsibility as opposed to falling under federal jurisdiction. Canada is organized into 10 provinces and three territories, which means there can be 13 distinct K-12 curricula. However, some territories have adopted provincial curricula, such as Yukon which follows British Columbia’s curriculum (Yukon Education, n.d.). While OE is present in all K-12 curricula in Canada, some provinces adopt a standalone OE curriculum while others integrate OE into other disciplines. For example, Alberta adopts a standalone approach where OE (titled Outdoor and Environmental Education in the Alberta curriculum) is introduced in grades 7 through 12 (Alberta, Citation1990) whereas Ontario integrates OE into the Health and Physical Education curriculum in all grades from K to 12 (Ontario Elementary, n.d.; Ontario Secondary, n.d.). Therefore, OE programs in K-12 differ widely across Canada.

Prior to the study by Asfeldt et al. (Citation2020), nearly 50 years have passed since the last comprehensive investigation of OE in Canada. In 1972, Passmore published the results of a nationwide examination of OE in Canada which included site visits, surveys, and interviews with teachers, students, administrators, and bureaucrats. Passmore reported that common OE learning goals included personal growth, presenting challenging and adventurous outdoor learning, stimulating student interests, developing social and cultural values, and enhancing ecological knowledge. Central to achieving these goals were pedagogies that integrated traditional disciplines (e.g. ecology, history, physical education, creative writing) and provided a holistic learning process. Passmore concluded his research by saying:

Outdoor environmental education is certainly not the answer to all our educational problems. But there is growing recognition that it is a method of teaching that can add that other important “R” to every subject on the curriculum – relevance in what we teach about the world in which our young people live (61).

Since Passmore’s (Citation1972) research, researchers have examined specific aspects of various K-12 OE programs in Canada (e.g. Breunig et al., Citation2014; Coe Citation2017; Ghafouri, Citation2014, Nazir & Pedretti, Citation2016; Russell & Burton, Citation2000), some conceptual papers have outlined the role and function of OE in Canada (e.g. Henderson & Potter, Citation2001; Maher, Citation2018), scholars have examined Indigenous issues related to outdoor and environmental education (Lowan-Trudeau, Citation2014, Citation2019; McLean, Citation2013) and one systematic review of qualitative OE research in Canada identified factors influencing the programs learning outcomes, and psychosocial benefits of OE from the learners’ perspective (Purc-Stephenson et al., Citation2019) which included OE programs in the camp, K-12, and post-secondary sectors.

In Purc-Stephenson et al.’s (Citation2019) systematic review, eight themes were identified that describe the learning outcomes and psychosocial benefits of OE programs. These include, (1) developing outdoor-living skills, (2) risk and challenge, (3) gaining environmental knowledge, (4) personal growth and leadership skills, (5) sense of community, (6) building connections, (7) having fun in nature, and (8) lasting impacts. In addition, Purc-Stephenson et al. developed a model depicting the common influences and processes of OE in Canada. Key influences are the educator and an interdisciplinary curriculum. Common processes include (1) exploration and fun, (2) balancing competence and challenge, and (4) intentional processing and reflection. Most frequently, outcomes include interpersonal skills (i.e. personal growth, sense of community, and building connections) and lasting impacts (i.e. influencing a student’s career path, improved skills and knowledge, and positive memories).

Guided by the conceptual model developed by Purc-Stephenson et al. (Citation2019), Asfeldt et al. (Citation2020) conducted a Canada wide qualitative investigation of K-12, post-secondary, and summer camp OE programs with the goal of “describ[ing] the philosophies, goals, and activities of Canadian OE programs to stimulate the development of a deeper understanding of Canadian OE” (1). Their research identified five themes describing the dominant philosophies that shape Canadian OE programs. These themes are: (1) influential founders, (2) hands-on experiential learning, (3) holistic and integrated learning, (4) journeying through the land, and (5) religion and spirituality. The most commonly identified program goals were (1) building community, (2) personal growth, (3) people and place consciousness, (4) environmental stewardship, and (5) employability and skill development. From a long list of program activities, eight themes emerged: (1) outdoor-living skills, (2) sport and recreation activities, (3) curricular activities, (4) reflection, (5) environmental education activities, (6) games, (7) arts and crafts, and (8) certification courses. Among the implications identified in Asfeldt et al. (Citation2020) are that “OE in Canada is grounded in experiential learning outdoors that link academic disciplines, and included the added benefit of helping students make connections with the land, its people, and our past” (11).

The results presented in this paper are part of a larger three phased, sequential exploratory mixed-method (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018) project examining the guiding philosophies, distinguishing characteristics, and central goals of OE in Canada to provide a foundation for the increased provision of OE in Canada. Results from earlier phases are reported in Purc-Stephenson et al. (Citation2019) and Asfeldt et al. (Citation2020). Here, we narrow the research focus to K-12 OE programs based on a nationwide quantitative survey shaped by the findings of Purc-Stephenson et al. (Citation2019) and Asfeldt et al. (Citation2020). In this study, we ask three research questions: (1) What are the underlying philosophies that guide K-12 OE in Canada? (2) What are the central learning goals of K-12 OE in Canada? (3) What activities are included in K-12 OE in Canada?

Materials and methods

Research design and sampling

Based on the research objectives of this study, we used a non-experimental descriptive research design (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). To create a large and diverse sample, we conducted a rigorous internet search of OE programs offered at K-12 schools in Canada. To focus our search, OE programs offered at K-12 schools had to meet the following criteria: (1) be identified as an OE program or a subprogram consisting of at least one course, (2) specify at least one learning goal, and (3) the program must have been currently operating or have been operating within the last two years. Using these criteria, we conducted an internet search of OE programs at K-12 institutions in each province and territory across Canada. Our goal was to use stratified random sampling (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018) to select approximately 35 schools from each province and territory to be invited to participate in our study.

However, as K-12 education is a provincial and territory responsibility, our ability to identify schools offering OE programs varied from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, in British Columbia and Alberta, school websites allowed us to identify schools that offered at least one OE course while in Newfoundland and Labrador, school websites listed only basic school information. In addition, we sought approval by the Nunavut Department of Education for approval to circulate our survey to Nunavut schools but that request went unanswered. Therefore, we supplemented our sampling approach with convenience and snowball sampling when necessary (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). For example, we advertised our study in the electronic newsletters for the Ontario Council of Outdoor Educators (COEO, n.d.) and the Alberta Council of Environmental Education (ACEE, Citation2020). Furthermore, in Quebec we distributed our survey through a colleague’s network of approximately 300 K-12 OE teachers.

Procedure

Between August and October 2019, we emailed 695 invitations to a combination Canadian K-12 schools and individual teachers, as well as through the two provincial OE newsletters and the Quebec network described earlier. Potential participants were provided a brief explanation of the study and an electronic link to our survey where they could provide consent and then complete the survey. The survey took approximately 20 min to complete and participants could choose to be included in a draw to win a $25 gift certificate to an outdoor store. No reminders emails were sent out. We asked that respondents have a minimum of 5-years work experience in outdoor education or a related field and be at least 18 years of age. This project was approved by the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board #2 (Pro00093297).

Materials

We developed an online survey based on our previous research (Asfeldt et al., Citation2020; Purc-Stephenson et al., Citation2019) and guided by our research questions. Therefore, the philosophies and learning goals included in our online survey were those identified in the qualitative phase of the project (Asfeldt et al., Citation2020). The survey was reviewed and pilot tested by four independent OE educators and consisted of 5 sections: participant demographics; program characteristics; program values, principles, and philosophies; program learning goals; and program activities.

Participant demographics

We gathered information including the participant’s age, gender, education level, years working in OE, years in their current position, and their job title.

Program characteristics

We asked participants to describe the OE program offered at their school, including the year the program was established, the number of courses offered annually, the grade levels involved, time of year the courses are offered (i.e. fall, winter, spring/summer). We also asked participants to specify whether the courses involved a day program (i.e. regularly spending time outside of the classroom such as a forest kindergarten), taking field trips (i.e. class takes a trip), overnight trips (e.g. 1–2 nights away), and/or an expedition or out-trip (e.g. three or more nights away). For courses involving an expedition, we asked participants to indicate the length of these trips.

Program values, principles, and philosophies

To examine underlying program values, principles, and philosophies, we asked participants to rate their level of agreement with seven statements reflecting common program values identified in our previous research (Asfeldt et al., Citation2020). Using a 5-point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), participants indicated whether their program was influenced by: a founder whose vision and values continue to influence the program today; a hands-on experiential learning approach that includes content, experience, and reflection; a holistic integrated learning approach where traditional subjects are blended (e.g. history, biology, physical education); a religious traditions such as Christianity or Judaism; a spiritual connection to people and the natural world; a self-propelled wilderness travel experience; and an educational philosopher’s ideas such as those of Dewey, Kolb, and/or Mezirow. We included an “other” option for participants to identify additional underlying philosophies. Finally, we asked respondents to choose which two philosophies were most essential in guiding their program.

Program learning objectives

To understand the learning goals of each OE program, we asked participants to rate their level of agreement with five statements reflecting common program learning goals identified in our previous research (Asfeldt et al., Citation2020). Using a 5-point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), participants rated the extent to which a central goal in their program was: building community by promoting relationships and teamwork; employability by providing students with certifications and work experiences; environmental stewardship by enhancing sustainable practices in students’ everyday lives and during out-trips; people and place consciousness by teaching about a specific location, people, and their historical significance; and personal growth through mental and physical challenges. We included an “other” option for participants to identify additional program goals. We also asked participants to select the two goals that were most essential to their program.

Lastly, we asked participants to specify if their OE program included an Indigenous learning objective. For those who indicated that it did, we included an open-ended question for them to describe what was involved.

Program activities

In order to identify the common activities of the OE programs sampled, we provided a list of the 32 most common activities identified in the previous stages of this project. We asked participants to indicate all activities that their program offered to students. The activities included, for example, traditional outdoor travel activities such as hiking, canoeing, and dog-sledding; outdoor-living skills such as camping, cooking, and building a campfire; nature studies and journal writing, as well as certification courses and safety training. Finally, we asked participants to specify which three activities were their most common program activities.

Data analysis

All data were entered into SPSS. Closed-ended, quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and Pearson Product Moment correlations. All open-ended, qualitative data were examined using thematic analysis.

Results

Participant demographics

There were 145 participants who completed the survey. We removed 45 participants due to excessive missing data (i.e. >50% data missing on key variables). The final sample included 100 participants, of whom a slight majority were female (n = 57, 57%), were approximately 40 years old (M = 39.56, SD = 9.88), and had nearly 13 years (M = 12.74, SD = 8.05) of OE work-related experience (See ). As participants may not have answered every demographic or program-related question, the counts and percentages may not equate to 100.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Program characteristics

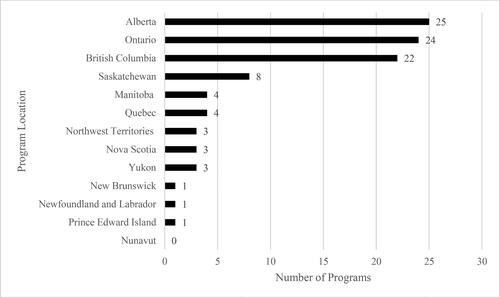

The participants reported on 100 different OE programs. As shown in , the majority of programs were located in Alberta (n = 25, 25.25%), Ontario (n = 24, 24.24%), and British Columbia (n = 22, 22.22%); there was little representation from the Atlantic provinces. presents detailed program characteristics. According to 81 participants, most OE programs were established after 2000 (n = 48, 59.26%), with the earliest program established in 1907 and the most recent in 2020 (Mdn = 2004). The schools sampled offered approximately six courses (M = 6.13, SD = 7.57) with an OE component each year. Of these courses, about a third (n = 32, 32.70%) were offered as a single elective course. However, it was more common for OE courses to be offered as part of a broader integrated OE program with a series of courses. While OE courses were represented at each grade level, we observed a trend whereby a greater number of courses were offered at higher grade levels (e.g. 28 OE-related courses in kindergarten versus 56 OE-related courses in Grade 12).

Table 2. Program characteristics.

Program philosophy

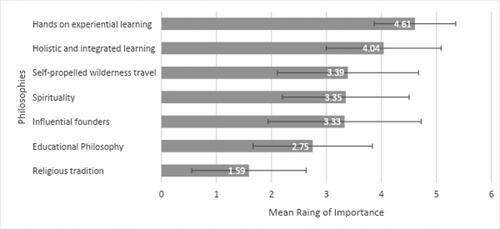

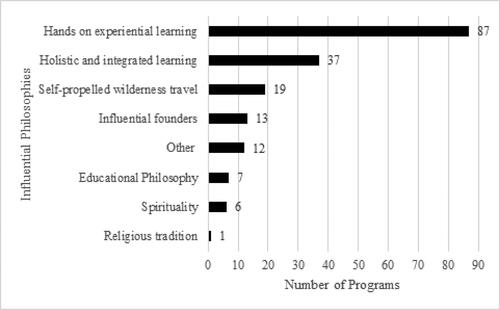

All of the participants reported that their OE program was influenced by a variety of values, principles, and philosophies rather than a single factor. As shown in , hands-on experience (M = 4.61, SD = 0.74) and holistic and integrated learning (M = 4.04, SD = 1.04) were rated as the most important values, principles, and philosophies underlying an OE program; educational philosophies (M = 2.75, SD = 1.09) and a religious tradition (M = 1.59, SD = 1.04) were rated the least important. When asked to identify the two most influential philosophies, participants identified hands-on experiential learning (87%) followed by holistic integrated learning (37%); the least influential was religious traditions (1%) (see ). When we coded responses for an “other” philosophy, 10 participants indicated that their OE program was also influenced by a belief that being outdoors in nature was healthy both physically and mentally for children and youth. Indeed, these participants reinforced a belief that OE programs provide an opportunity for students to disconnect from technology and reconnect with nature.

Program learning goals

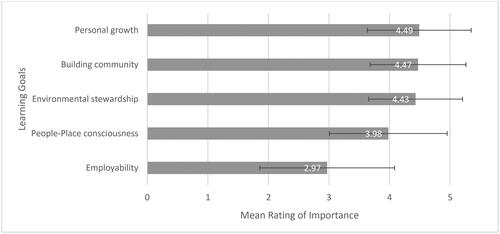

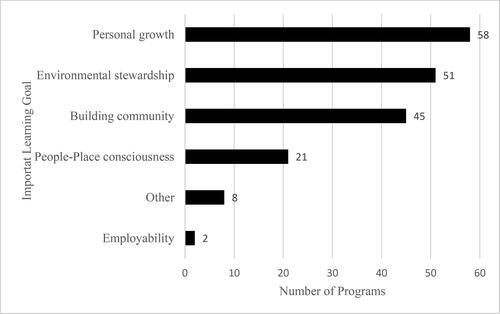

Similar to program philosophies, participants indicated that their OE program entailed several learning goals instead of one central goal. As shown in , participants rated personal growth, (M = 4.49, SD = 0.86), building community (M = 4.47, SD = 0.79), and environmental stewardship (M = 4.43, SD = .77) as the three learning goals most central to their programs. Employability was the least important learning goal (M = 2.97, SD = 1.11). When asked to identify the two most important learning goals, participants identified personal growth (58%) and environmental stewardship (51%); the least important learning goal was employability (2%) ().

In addition, the majority of participants (n = 72, 73.5%) indicated that their OE programs included an Indigenous learning objective. A review of the open-ended responses revealed that Indigenous learning objectives vary widely across OE programs in terms of content and depth. For example, some programs incorporated land acknowledgement at the start of their day whereas other programs invited an Elder to lead a discussion of traditional land use, customs, and language. Most programs incorporated a discussion of Indigenous traditions (e.g. sweat lodges, smudging), history of settler-Indigenous relations (e.g. fur trading), and activities (e.g. beading, food processing, making mittens, and canoeing). Only two participants mentioned that their OE program included a discussion of residential schools and colonial history.

We examined the possible associations between the programs’ underlying philosophy and the programs’ learning goals. As shown in , the programs that had underlying philosophies of hands-on experiential learning, holistic integrated learning, and spiritual connections were more likely to have learning goals that focused on building community, environmental stewardship, people and place consciousness, and personal growth. Of the learning goals, personal growth was significantly associated with all of the program philosophies except educational philosophy and religious traditions. In fact, the philosophies of educational philosophy and religious traditions were not associated with any particular learning goal.

Table 3. Learning goals correlations.

Program activities

Of the 32 activities listed, participants reported that their OE programs incorporated approximately 13 activities (M = 13.33, SD = 5.25), ranging from one activity to 24 activities. For ease of description, we grouped the 32 activities into seven broad categories, which are presented in . Nearly 50% of OE programs incorporated outdoor-living skills (e.g. camping, cooking, fire-building), 22% incorporated sport and recreational activities (e.g. hiking, orienteering, snowshoeing), and less than 1% offered arts and crafts. Of the 100 programs sampled, the most common activities included camping (79%), campfires (77%), games (77%), nature studies (70%), orienteering (70%), and hiking (69%). These activities were commonly offered at all grade levels. The least common activities included hunting (8%), horseback riding (8%), rafting (7%), dog sledding (6%), and caving (5%). We observed that the least common activities were more usually offered at senior grade levels and often involved greater risk and specialized equipment.

Table 4. Program activities.

Discussion

Philosophies

The results demonstrate that K-12 OE in Canada is strongly influenced by philosophies of learning that value hands-on experiential learning and holistic integrated learning. Holistic integrated learning blurs traditional disciplinary boundaries and subject areas such as history, biology, and physical education are blended together in order to highlight linkages and connections. This is consistent with previous findings (Asfeldt et al. Citation2020; Breunig et al. Citation2014; Coe Citation2017; Ghafouri, Citation2014, Nazir & Pedretti, Citation2016; Russell & Burton, Citation2000) as well as those purported by Henderson and Potter (Citation2001). Moreover, these findings point to Canadian K-12 outdoor educators having a more organic, transformational, philosophy of education as opposed to a primarily discipline based, transactional, one. Therefore, K-12 OE in Canada appears to be guided by educational philosophes that embrace a flexible, rhythmic, and intuitive form of teaching where complexity and interconnections are welcome and are less encumbered by common structures of education such as strict schedules, classrooms, and the neat boundaries of curricula (Blenkinsop et al. Citation2016).

Historically, OE has often been viewed as a means of educational reform that has pushed back against the institutional and disciplinization of schooling (Quay & Seaman, Citation2013; Roberts, 2012). That is, with the formalization of schooling came specialization of subject matter which often resulted in students struggling to understand the relationship between emerging subjects. This was coupled with education taking place in a specialized setting–the school–which was commonly decoupled from the community and the students’ everyday life. This typically resulted in the focus of schooling being to know the content of specific subjects with little importance placed on integrating subject matters or demonstrating the relevance of that knowledge in the students’ everyday life. Further, because this institutional, transactional schooling took place in the specialized setting of schools, it did little to help students’ personal development or to assist them in understanding their place in the world or their local community. A number of educational reform movements evolved to try to overcome these shortcomings which educational philosopher John Dewey termed a “medieval conception of learning” (Dewey Citation1900, 41). Therefore, that Canadian K-12 outdoor educators identify hands-on experiential learning and holistic integrated learning as the two primary values that drive their programs and teaching practice, suggests that these teachers continue to attempt to overcome the shortcomings of formal schooling by embracing a natural and intuitive approach to education. In this more natural and intuitive approach, the complex interrelationships of specialized subjects are embraced and opportunities are provided through outdoor experiences for the purposeful use of that subject matter which helps students understand their place in the world and local community while on a journey of personal and social development.

Learning goals

There are some clear links between the dominant philosophies and values identified by Canadian K-12 educators and the primary learning goals of Canadian OE programs. This should not be surprising and suggests that teachers’ educational values drive their teaching practice and learning goals, as they should. The primary learning goals of OE support the idea of OE as a form of holistic integrated learning with roots in the personal growth and character development agenda of the Canadian summer camps tradition and the environmental movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The top four most important and frequently identified goals (i.e. personal growth, community building, environmental stewardship, and people and place consciousness) could be grouped into two categories such as personal and social development and environment and place consciousness. From this perspective, OE in Canadian K-12 schools could be seen as having two overarching goals related to developing and providing personal and social skills combined with environmental and place specific knowledge using both scientific and social sciences knowledge and skills. Employability was the least common central goal with only 2% of respondents identifying employability as one of their top two program goals affirming OE as primarily a form of holistic education rather than a form of outdoor vocational training.

Canadian OE as a means for achieving holistic integrated learning outcomes is further strengthened by our finding that four learning goals–personal growth, building community, environmental stewardship, and people and place consciousness–are significantly related. Moreover, these four learning goals were the most common among the OE programs we sampled. These findings suggest these four learning goals are central to the vast majority of OE programs and it is unusual for an OE program to focus solely personal or social goals or environmental or place goals; most programs have blended and integrated goals.

These findings parallel many other studies of OE in Canada and internationally that identify learning outcomes and lasting impacts of OE programs as falling into the two broad categories of personal and social and environmental and place specific knowledge (e.g. Asfeldt et al., Citation2017; Breunig et al., Citation2014; Coe Citation2017; Nazir & Pedretti, Citation2016; Prince, Citation2020; Russell & Burton, Citation2000; Tan & So, Citation2019). In addition, these findings are strikingly similar to three of the four pillars of the Council of Outdoor Educators of Ontario: Education for Environment, Education for Character, and Education for Well-Being. The fourth pillar is Education for Curriculum which describes OE as “broaden[ing] and deepen[ing] the knowledge base of all subject areas…in integrating ways” (Humphreys, Citation2018, 7). This fourth pillar aligns well with our findings outlining the underlying philosophies of OE described earlier.

Activities

We suspect that there is a strong relationship between some program characteristics and typical OE activities. For example, over 90% of OE programs offer courses in the fall, 94% offer courses in the winter while only 30% of programs offer courses in spring and summer. This reflects the common seasonal timing of public schooling in Canada which generally takes place between September and June. Therefore, it is not surprising that the most common activities (i.e. camping, campfires, games, orienteering, hiking, and cooking) can be done in all seasons and that snowshoeing and canoeing are the next most common activities which reflect activities that make sense in both winter and non-winter seasons.

Other program characteristics that likely influence which OE activities programs offer include that 86% of programs include OE sessions that take place outside during a normal class period. This requires that the activities are logistically simple and likely school based which reflect the need to address the common barriers of limited time and logistics which have been identified by several researchers as primary constraints of K-12 OE (Mannion et al., Citation2013; Shume & Blatt, Citation2019). While most OE activities take place during traditional class time, most programs also include day-trips (77%) and overnight trips of 1–2 days/nights (68%). Clearly, with more time, more logistically complex and engaged activities are possible. Henderson and Potter’s (Citation2001) claim that the pinnacle of Canadian OE programs is a self-propelled wilderness travel experience. This data indicated that almost half (48%) of programs include a self-propelled wilderness travel experience with an average length of 5 days. While our data are not precise enough to determine in which grade levels these expeditions happen, we expect they happen in later grades. Because the 48% of programs offering an expedition is spread across all grades levels (K-12), this likely means that the percentage of later grades participating in an expedition is higher than 48% lending more support for Henderson and Potter’s claim that self-propelled wilderness travel is a pinnacle experience. Had our data been more precise, it would have been interesting to determine if expeditions were more common in some regions or in rural versus urban school districts and in which specific grades expeditions take place.

Research investigating the development of environmental consciousness and stewardship in children and youth demonstrates that early experience and learning in natural settings play an important role in influencing future responsible environmental behavior and knowledge (Braun et al., Citation2018; Ernst, Citation2012; Mannion et al., Citation2013; Randler et al., Citation2005). Similar research also claims that longer experiences are more likely to have a lasting impact (Braun & Dierkes, Citation2017; Hattie et al., Citation1997). Therefore, it is encouraging that Canadian K-12 schools offer OE learning at all grade levels and include experiences of multiple days. Based on the above research, in order to maximize lasting environmental literacy, increasing outdoor and environmental learning in elementary grades is particularly important as is including multiple day experiences. However, at Eames, Barker, and Scarff (Citation2018) point out, in addition to formative school experiences, summer camps and family experiences also play an important role as a form of environmental education for sustainability for children and youth. Therefore, if Canadians desire to move towards a more environmentally sustainable future, it is important that parents recognize the role that they too can play in providing nature experiences that will have a lasting impact on their children and not rely solely on public education and summer camps to provide these experiences.

Just over half of programs (55%) visit an outdoor center or summer camp which means that the activities engaged in will be determined by those that the camps and centers provide. Ideally, we would have conducted regional correlations to determine which activities are most common in which regions, but our sample was not evenly distributed enough to make those comparisons. Overall, OE activities in Canadian K-12 schools reflect the need for activities that make sense given the winter and non-winter seasons, what the local environments allow (i.e. lakes and rivers, forested areas, ski trails), and can accommodate typical class sizes. Based on our qualitative study (Asfeldt, et al., Citation2020), outdoor educators articulated that the activities included in their programs aligned and changed with the skills and experience of the teachers. Therefore, it makes sense that activities identified through our surveys are basic fundamental skills that most OE teachers would have regardless of whether their personal OE skills are rooted, for example, in canoe tripping, climbing, backpacking, or sea kayaking. The skills of camping, campfires, orienteering, and cooking are common to all these specific skill-based traditions.

A particularly interesting finding related to activities is that the majority of participants (n = 72, 73.5%) indicated that their OE programs included an Indigenous learning objective. However, no participants choose Indigenous activities from the list of OE activities that are included in their programs. We are not sure how to understand this finding. It could be that Indigenous learning activities are not “classic” outdoor or environmental education activities, or that Indigenous learning goals are relatively new and not yet linked to specific activities but rather embedded (blended) throughout the program. In Lowan-Trudeau’s (Citation2014) exploration of the question of how Indigenous ecological perspectives might reshape environmental education in Canada, he concludes that “it is already beginning” (361). Our findings support this notion. Later, Lowan-Trudeau (Citation2019) claims that educators “often experience formidable internal and external challenges” (62) when incorporating Indigenous content into their courses. Lowan-Trudeau contends that an “inadequate level of pre-service, curricular, resource, and research support” (62) for teachers contributes to some teachers’ reticence to include Indigenous content in their courses. Lowan-Trudeau’s perspective may help explain these findings. Regardless, this is an area worthy of further research.

Implications

Outdoor education can be an effective means for many Canadian educational jurisdictions to achieve their mission and vision and for preparing children and youth for current and emerging environmental and social challenges. For example, the British Columbia Ministry of Education’s stated mission is “to enable learners to develop their individual potential and to acquire knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to contribute to a healthy society and a prosperous and sustainable economy”. To achieve this mission, British Columbia aims to develop the “educated citizen” which they define as a person having intellectual development, human and social development, and career development. (BC Education, n.d.). Therefore, as Canadian educational jurisdictions continue to develop educational programs to meet the changing needs of Canadian students for a changing world–particularly to address pressing environmental and social issues–OE should be considered for its strength as a form of holistic and integrated learning that embraces experiential teaching methods, achieves a range of learning goals, and links that learning to student’s everyday lives and local communities.

The holistic and integrated nature of OE in Canada that blends learning goals from a broad spectrum of disciplines, may be one factor that leads to OE’s struggles to establish its place in some Canadian K-12 in jurisdictions. Hands-on experiential learning and holistic integrated learning are hallmarks of early forms of outdoor education that evolved to address a lack of direct experience in education and the silozation of subject matter that didn’t reflect the interconnected nature of life (Quay & Seaman, Citation2013; Robert, 2012). Typically, school curricula identify learning goals in specific disciplines and do not specify methods for how those learning objectives will be accomplished. Therefore, if OE educators see OE as more of a method than a specific subject matter, it is not surprising that OE struggles to find its place alongside well-established disciplines with clearly defined subject matters and learning goals. This may also explain why in some Canadian jurisdictions, OE is a standalone subject and integrated in others. In jurisdictions with standalone OE curricula, OE is likely viewed more as subject than method. Ironically, the holistic and integrated nature of OE in Canada may be both a strength and a shortcoming. It is a strength because it that is a foundation of engaged and purposeful experiences of Canadian OE that contributes to the achievement of the overarching purpose and mission of K-12 education in Canada. However, it is a shortcoming because it makes it difficult to see how OE fits neatly into a typical siloized and discipline structured curricula. Consequently, it is important for teachers, administrators, and politicians to look beyond the traditional disciplinary divisions of public education when developing curricula and allocating funding in order to prepare children and youth for a sustainable future.

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations to note. First, our sample is not equally representative of all regions (i.e. geographic, cultural, socio-economic) across Canada. Although we applied a broad sampling strategy to collect responses from K-12 schools across Canada, our efforts resulted in many responses from participants from OE programs in Ontario and Alberta and relatively few from Quebec and the Atlantic provinces. The difference in responses may be because we also advertised our study in electronic newsletters of OE associations in Ontario and Alberta. However, our pilot research did show that many OE programs exist in Ontario and Alberta, so it is possible that our sample reflects the relative distribution of OE programs across Canada. Further, as noted earlier, K-12 program and course information available online varied from jurisdiction to jurisdiction which influenced the development of the study group. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to all regions and jurisdictions of Canada.

In addition, while we asked respondents to specifically identify the guiding philosophies and learning goals of their programs, we can’t be sure that the respondent’s answers reflect only their program philosophies and learning goals. Therefore, these results are likely a mix of program and personal teacher philosophies and learning goals.

Future research

This research points to a number of important and interesting future research questions. For example, a particularly important and timely question is to understand more fully what the Indigenous learning goals are that teachers have identified as central to their programs and how those goals are achieved. As well, it is important to identify what specific role and contribution Canadian K-12 OE programs can play in advancing reconciliation in Canada. Given the hands-on experiential holistic integrated nature of OE in Canada that takes place outside on traditional territories, OE seems well placed to play a specific and meaningful role in reconciliation given that OE commonly connects people, place, and environment.

Another interesting project would be to identify the characteristics of long-standing successful OE programs and to determine what best practices they share that might enable other jurisdictions to build and maintain OE programs. Such an investigation might also identify barriers and challenges for developing K-12 OE programs and clarify which barriers are real and which are perceived.

Had our data been more precise, it would have been interesting to see if expeditions were more common in some regions or in rural versus urban school districts. Therefore, this too would be an interesting future investigation. As well, on a jurisdictional basis, it would be helpful to review specific jurisdiction’s educational missions and values and demonstrate how OE can assist in achieving those goals given the outcomes of this and related research.

While this research was designed and data gathered prior to the COVID pandemic, it would be informative to investigate how K-12 education has changed and adapted to COVID restrictions. Based on local and national news stories (CBC, Citation2021), it appears many Canadian K-12 schools adapted to COVID restrictions by taking their classes outside. Therefore, understanding how taking classes outside has impacted the perception of outdoor education and if the pandemic might have served as a springboard for increasing outdoor education opportunities in K-12 education would be valuable.

Finally, this study may serve as a model for OE research in other parts of the world facilitating international and cross-cultural comparisons and learning. As international colleagues might use these results to inspire and guide their OE courses, so might Canadians use similar findings from other parts of the world to inspire and guide OE in Canada.

Conclusion

This research set out to answer three specific questions: (1) What are the underlying philosophies that guide K-12 OE in Canada? (2) What are the central learning goals of K-12 OE in Canada? (3) What activities are included in K-12 OE in Canada? In summary, Canadian K-12 OE programs are strongly influenced by a belief in the value of hands-on experiential learning as well as the virtues of holistic integrated learning that blends knowledge from a variety of disciplines and links that knowledge into students’ lives. Canadian K-12 OE programs have a blend of learning goals that include goals of both personal and social development as well as environmental and place consciousness. The activities of Canadian OE programs are varied but commonly included basic outdoor skills that can be practiced regardless of seasons (i.e. campfires, cooking). However, activities also vary with the seasons (i.e. canoeing, snowshoeing).

Overall, these results support the finding in Asfeldt et al’s., (2020) findings that “OE in Canada is grounded in experiential learning outdoors that link academic disciplines, and included the added benefit of helping students make connections with the land, its people, and our past” (11). As well, these findings support Purc-Stephenson et al. (Citation2019) conceptual model depicting common influences, curriculum, and outcomes of Canadian OE. Further, this research points to Henderson and Potter (Citation2001) being correct in a number of their assertions about OE in Canada. Specifically, that OE in Canada embraces curricular integration while striving to achieve the goals of both adventure and environmental education often through a self-propelled wilderness travel experience. Finally, Passmore’s (Citation1972) claim that outdoor environmental education “is a method of teaching that can add that other important “R” to every subject on the curriculum - relevance in what we teach about the world in which our young people live” (61) appears to be as true today as it was in 1972. Having said this, as Passmore articulated almost 50 years ago, OE is not a silver bullet that will address all the challenges of education in Canada. Nevertheless, hands-on experiential learning and holistic integrated learning are hallmarks of early forms of outdoor education that evolved to address a lack of direct experience in education and the silozation of subject matter that didn’t reflect the interconnect nature of life (Quay & Seaman, Citation2013; Robert, 2012). Therefore, based on the philosophies, learning goals, and activities of K-12 OE programs in Canada identified here, a well-developed OE program can facilitate engaged, meaningful, and relevant educational experiences that can address some of the challenges of educating Canada’s children and youth. Moreover, the holistic and integrated nature of OE is well suited to prepare children and youth for the challenges of living well in the 21 century that are well aligned with the purpose and mission of K-12 education in Canada.

Disclosure statement

There is no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACEE. 2020. Alberta council for environmental education. Retrieved November 13, https://www.abcee.org/

- Alberta, O. E. 1990. Environmental and outdoor education. Retrieved October 30, 2020 from https://education.alberta.ca/media/3114964/eoed.pdf

- Asfeldt, M., R. Purc-Stephenson, and G. Hvenegaard. 2017. “Students’ Perceptions of Group Journal Writing as a Tool for Enhancing Sense of Community on Wilderness Educational Expeditions.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership 9 (3): 325–341. doi:10.18666/JOREL-2017-V9-I3-8362.

- Asfeldt, M., R. Purc-Stephenson, M. Rawleigh, and S. Thackeray. 2020. “Outdoor Education in Canada: A Qualitative Investigation.” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 21(4): 297–310. doi:10.1080/14729679.2020.1784767.

- BC Education. n.d. Vision for student success. Retrieved December 02, 2020 from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/administration/program- http://management/vision-for-student-success

- Blenkinsop, S., J. Telford, and M. Morse. 2016. “A Surprising Discovery: Five Pedagogical Skills Outdoor and Experiential Educators Might Offer More Mainstream Educators in This Time of Change.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 16 (4): 346–358. doi:10.1080/14729679.2016.1163272.

- Braun, T., R. Cottrell, and P. Dierkes. 2018. “Fostering Changes in Attitudes, Knowledge and Behavior: Demographic Variation in Environmental Education Effects.” Environmental Education Research 24 (6): 899–920. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1343279.

- Braun, T., and P. Dierkes. 2017. “Connecting Students to Nature – How Intensity of Nature Experience and Student Age Influence the Success of Outdoor Education Programs.” Environmental Education Research 23 (7): 937–949. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1214866.

- Breunig, M., J. Murtell, C. Russell, and R. Howard. 2014. “The Impact of Integrated Environmental Studies Program: Are Students Motivated to Act Pro-Environmentally?” Environmental Education Research 20 (3): 372–386. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.807326.

- CBC. 2021, April 13. Government to spend $7M on outdoor learning for N.S. elementary schools. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/schools-outdoor-learning-provincial-federal-government-education-1.5985257

- Coe, H. A. 2017. “Embracing Risk in the Canadian Woodlands: Four Children’s Risky Play and Risk-Taking Experiences in a Canadian Forest Kindergarten.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 15 (4): 374–388. doi:10.1177/1476718X15614042.

- COEO. n.d. The council of outdoor educators of Ontario. Retrieved November 13, 2020, from https://www.coeo.org/

- Creswell, J, and D. Creswell. 2018. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dewey, J. 1900. The School and Society. The University of Chicago Press.

- Dimock, H. S., and C. E. Hendry. 1929. Camping and Character: A Camp Experiment in Character Education. New York, Association Press.

- Dyment, J. E., and T. G. Potter. 2015. “Is Outdoor Education a Discipline? Provocations and Possibilities.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 15 (3): 193–208. doi:10.1080/14729679.2014.949808.

- Eames, C., M. Barker, and C. Scarff. 2018. “Priorities, Identity and the Environment: Negotiating the Early Teenage Years.” The Journal of Environmental Education 49 (3): 189–206. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1415195.

- Ernst, J. 2012. “Influences on and Obstacles to K-12 Administrators’ Support for Environment- Based Education.” The Journal of Environmental Education 43 (2): 73–92. doi:10.1080/00958964.2011.602759.

- Ghafouri, F. 2014. “Close Encounters with Nature in an Urban Kindergarten: A Study of Learners’ Inquiry and Experience.” Education 3-13 42 (1): 54–76. doi:10.1080/03004279.2011.642400.

- Hattie, J., H. Marsh, J. Neill, and G. Richards. 1997. “Adventure Education and Outward Bound: Out-of-Class Experiences That Make a Lasting Difference.” Review of Educational Research 67 (1): 43–87. doi:10.3102/00346543067001043.

- Henderson, B., and T. Potter. 2001. “Outdoor Adventure Education in Canada: Seeking a Way Back in.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 6: 225–242.

- Humphreys, C. 2018. Dynamic Horizons: A Research and Conceptual Summary of Outdoor Education. Kingston, ON: The Council of Outdoor Educators of Ontario.

- Lowan-Trudeau, G. 2014. “Considering Ecological Métissage: To Blend or Not to Blend?” Journal of Experiential Education 37 (4): 351–366. doi:10.1177/1053825913511333.

- Lowan-Trudeau, G. 2019. “From Reticence to Resistance: Understanding Educators’ Engagement with Indigenous Environmental Issues in Canada.” Environmental Education Research 25 (1): 62–64. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1422114.

- Maher, P. T. 2018. “Conversations across the Pond: Connections between Canadian and Western European Outdoor Studies over the Last 20 Years.” In The Changing World of Outdoor Learning in Europe, edited by P. Becker, C. Loynes, B. Humberstone, & J. Schirp, 251–263. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Mannion, G., A. Fenwick, and J. Lynch. 2013. “Place-Responsive Pedagogy: Learning from Teachers’ Experiences of Excursions in Nature.” Environmental Education Research 19 (6): 792–809. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.749980.

- McLean, S. 2013. “The Whiteness of Green: Racialization and Environmental Education.” The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 57 (3): 354–362. doi:10.1111/cag.12025.

- Nazir, Joanne, and Erminia Pedretti. 2016. “Educator’s Perceptions of Bringing Students to Environmental Consciousness through Engaging Outdoor Experiences.” Environmental Education Research 22 (2): 288–304. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.996208.

- Nicol, R. 2002. “Outdoor Education: Research Topic or Universal Value? Part One.” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 2 (1): 29–41. doi:10.1080/14729670285200141.

- Ontario Elementary. (n.d.). The Ontario curriculum elementary. Retrieved June 23, 2020 from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/

- Ontario Secondary. (n.d.). The Ontario curriculum secondary. Retrieve June 23, 2020 from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/secondary/

- Passmore, J. 1972. Outdoor Education in Canada–1972. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Education Association.

- Prince, H. E. 2020. “The Lasting Impacts of Outdoor Adventure Residential Experiences on Young People.” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 21(3): 261–276.doi:10.1080/14729679.2020.1784764.

- Purc-Stephenson, R. J., M. Rawleigh, H. Kemp, and Morten. Asfeldt. 2019. “We Are Wilderness Explorers: A Qualitative Review of Outdoor Education Research in Canada.” Journal of Experiential Education 42 (4): 364–381. doi:10.1177/1053825919865574.

- Quay, J, and J. Seaman. 2013. John Dewey and Education Outdoors: Making Sense of the ‘Educational Situation’ through More than a Century of Progressive Reform. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Randler, C., A. Ilg, and J. Kern. 2005. “Cognitive and Emotional Evaluation of an Amphibian Conservation Program for Elementary School Students.” The Journal of Environmental Education 37 (1): 43–52. doi:10.3200/JOEE.37.1.43-52.

- Russell, C., and J. Burton. 2000. “A Report on an Ontario Secondary School Integrated Environmental Studies Program.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 5: 287–303.

- Shume, T., and E. Blatt. 2019. “A Sociocultural Investigation of Pre-Service Teachers’ Outdoor Experiences and Perceived Obstacles to Outdoor Learning.” Environmental Education Research 25 (9): 1347–1367. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1610862.

- Tan, E., and H. J. So. 2019. “Role of Environmental Interaction in Interdisciplinary Thinking: From Knowledge Resources Perspectives.” The Journal of Environmental Education 50 (2): 113–130. doi:10.1080/00958964.2018.1531280.

- Wall, S. 2009. The Nurture of Nature: Childhood, Antimodernism, and Ontario Summer Camps, 1920–1955. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Wattchow, B, and M. Brown. 2011. A Pedagogy of Place: Outdoor Education for a Changing World. Clayton, Australia: Monash University.

- Yukon Education. (n.d.). Learning about Yukon’s school curriculum. Retrieved October 29, 2020 from https://yukon.ca/en/school-curriculum.