Abstract

Given the prominence of sustainability in current global crises and the commitment of societies to the Sustainable Development Goals, this mixed methods study ascertains how Dutch higher education students (N = 549) integrate sustainability into their life purposes. From quantitative data, we identified four purpose profiles: purposeful (33%), dreamer (32%), self-oriented (18%), and disengaged (17%), signifying a potential commitment to sustainability among over half of the participating students. However, technology students differed from other respondents in that fewer of them were identified as having a purposeful profile and more of them were disengaged. The data reveal happiness (61%), work (22%), and sustainability (22%) as the most frequently mentioned contents of purposes, implying a more self-oriented picture than indicated in the profiles. The two case studies illustrate concrete ways of manifesting sustainability as a purpose in life. We discuss the educational implications of this, especially the need to enhance sustainability education in the domain of technology.

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainability as a goal in higher education

This study investigates sustainability as a purpose in life among Dutch higher education students. Given the prominence of sustainability in current global crises and the commitment of societies to the United Nations’ (2015) Sustainable Development Goals, we aim to ascertain how well tertiary-level students have internalized and integrated sustainability into their lives and identities, and more precisely into their life purposes. In adopting the relatively new operationalization of life purpose by Damon, Menon, and Bronk (Citation2003), we present a rarely studied perspective on sustainability.

According to Hallinger and Chatpinyakoop (Citation2019), sustainability studies on the tertiary level have focused on (1) managing for sustainability in higher education from institutional perspectives, (2) research and development in the form of reviews and instrument development, and (3) teaching, learning, and capacity development, which includes planning and testing the effectiveness of study modules and research on sustainability-related conceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. The present study belongs to the third category, with a specific interest in sustainability as ‘a matter of the heart’, as it is, for instance, for the young climate-change activist Greta Thunberg, as well as ‘a matter of the mind’ (Marathe, Dutta, and Kundu Citation2020). Thus, we argue that sustainability education on the tertiary level is justifiably an integral part of students’ holistic development and citizenship education. The implication is that students are educated, encouraged, and guided to acknowledge and reflect on their personal values and life goals connected to the subjects they study, to living a good life and contributing to the well-being of society (Colby Citation2020; De Ruyter and Schinkel Citation2017).

In the Netherlands, the context of the present study, the law requires higher education institutes to address the personal development of students and to inculcate a sense of social responsibility (Higher Education Law 1992, article 1.3.5.). This means that sustainability education should be a pervasive topic across study programs and courses (Kopnina Citation2018; Pashby and de Oliveira Andreotti Citation2016; Van Poeck, König, and Wals Citation2018). However, Dutch scholars have questioned the fulfillment of these obligations (De Ruyter and Schinkel Citation2017; Schutte Citation2017). Similar tendencies have been identified in sustainability education in other countries, notably among students of technology and economics (e.g. Hilty and Huber Citation2018; Marathe, Dutta, and Kundu Citation2020). This motivated us to holistically investigate personal positions on sustainability among Dutch higher education students. In other words, we focus on the extent to which students perceive sustainability as a life purpose.

Sustainability is often described in terms of three main pillars, namely environmental, social, and economic (Goodland Citation1995; Purvis, Mao, and Robinson Citation2018). Environmental sustainability refers to sustainable growth and to resolving global crises such as climate change; social sustainability concerns human rights and ensuring that they are respected and advocated in society; while economic sustainability aims at the ethical and equal distribution of economic resources. Hence, sustainability ranks as a fundamental quality of good citizenship.

Westheimer and Kahne (Citation2004) have identified three levels of citizenship: personally responsible, participatory, and justice-oriented. The first of these concerns the individual: citizens are those who recycle their clothes and biowaste, and donate money to good causes, for example. Participatory citizenship operates more on the collective level, in influencing and contributing to establishing recycling initiatives in the community or society. Finally, justice-oriented citizens are concerned with social, political, and economic structures, seeking to address the root causes of problems. As an example, they understand that the shipping of western recycled clothes to developing countries may harm local industries and cause unemployment, especially among women, and therefore they seek solutions on the structural level by addressing the main causes of such injustice. Even though these categories appear descriptive and useful, as Westheimer and Kahne (Citation2004) point out, in everyday life they are not as clearcut as they seem: individuals may identify with several categories, and this may also manifest in different combinations.

The present study was conducted at Hanze University of Applied Sciences (HUAS) in The Netherlands, an institution aiming to maximally develop its students’ talents so they can be help make a difference in the world (Hanzehogeschool Groningen Citation2021). The HUAS is a large institute of higher education with over 28,000 students and offers education in several subjects: economics, technology, social and education studies, healthcare, and the arts. It has been developing initiatives, courses, research, and networks to support sustainability education and holistic growth among students since 2015. A group of teachers established ‘the color palette’ (Kool and Schutte Citation2016), which highlights eight aspects of holistic education, among them a moral compass, a sense of community and social responsibility, and includes examples of lessons and methods introduced. Some of these aspects, such as developing professional identity in students, as well as social awareness and involvement, have been integrated into profession-related education. For example, students on some programs are asked to answer the question, ‘What kind of professional do you want to be?’ Although holistic education emphasizing civic engagement is not yet widespread within the HUAS, the HUAS has invested effort in developing sustainability in policy (e.g. aims in HUAS strategy), education (e.g. sustainable courses) (Schutte and Van der Lei Citation2018), and research. The HUAS has also endeavored to achieve the United Nations’ (2015) Sustainable Development Goals through a transition to green energy in collaboration with Energy Academy Europe (EAE), the Northern Innovation Lab for Circular Economy, and the Bio Economy Region Northern Netherlands (BERNN). There is also a program enabling students to become Green Ambassadors by participating in a sustainable project, taking on an internship, or doing a graduation project on an environmental aspect of sustainability. The strategic aim of the HUAS is to be an engaged university (Hanzehogeschool Groningen Citation2021) specifically by embracing the following five Sustainable Development Goals: ‘good health and well-being’, ‘quality education’, ‘affordable and sustainable energy’, ‘responsible consumption and production’, and ‘partnerships for achieving objectives.’ Emphasizing the last of these goals, the HUAS encourages graduates to consider eventually becoming part of and forming partnerships for responsible action in pursuit of more equitable trade and sustainable development across borders.

1.2. Purpose in life during higher education studies

Earlier research has identified purpose in life as a developmental asset and a moral beacon providing resilience in challenging times, promoting overall well-being, and facilitating academic learning (Sumner, Burrow, and Hill Citation2018). It refers to 1) a long-term intention of an individual 2) in which one is engaged in realizing, and 3) a goal by which an individual contributes to the wellbeing of others (Damon, Menon, and Bronk Citation2003). The third, beyond-the-self dimension is pivotal as it highlights the noble and prosocial nature of purpose (Moran Citation2009). The definition by Damon et al. fits the context of sustainability as it inherently refers to serving or helping other people, society, or nature. Conceptually, therefore, it is close to notions such as mission and calling and addresses profound existential questions such as ‘Why do I exist?’

Purpose in life develops over the life span (Bronk Citation2014). Studies on young people have shown that it typically emerges among 11-year-olds, although some children have ideas and ideals regarding their future occupations even earlier. American researchers have identified profiles that illustrate the development of purpose: disengaged, dreamer, self-oriented, and purposeful (Damon Citation2008; Moran Citation2009). Purposeful refers to a fully developed or mature sense of purpose that incorporates all three of the dimensions presented by Damon et al. while leaving room for further development and expansion. The other profiles are potential precursors to purpose, to be developed in due course. In recent years, self-orientation has become a prevalent feature among youth in traditionally collective cultures such as Iran and China (Hedayati et al. Citation2017; Jiang and Gao 2018; see also Moran Citation2019). Among American college students, Moran (Citation2009) identified the most common profiles as self-orientation and purposefulness (both 42%): ten percent were dreamers with a strong beyond-the-self orientation but did not realize their visions, and a further ten percent were disengaged and could not perceive any long-term and meaningful intention in themselves, did not engage in purpose-related activities, and were not interested in contributing to society.

The majority of studies adopting the definition by Damon et al. have been conducted in America, and their conceptualization is relatively novel in European contexts (Moran Citation2019; see also Bronk, Citation2014 for a review). However, some studies have been conducted in Finland. Kuusisto and Tirri (Citation2021), for example, investigated how personal life purposes aligned with professional purposes among preservice and in-service teachers (N = 912, N = 77, respectively). The data comprised subjects’ written statements describing in their purpose in life in their own words. The majority of the Finnish teachers aimed at happiness, having a family and a job, and over half of them had only self-oriented aspirations. The present study examines the prevailing situation among Dutch higher education students, with a special focus on sustainability. We adopted a mixed-methods approach incorporating quantitative and qualitative methods to build a holistic understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The aim is to investigate the extent to which sustainability is a purpose in life among tertiary-level students. We seek answers to the following research questions:

What purpose profiles can be identified among students in a Dutch higher education institution? (quantitative survey data)

How do students describe their life purposes and how is sustainability represented in their written statements? (qualitative survey data: open-ended responses)

How does sustainability manifest in different purpose profiles and among students in different domains? (mixed-methods: survey, open-ended responses)

How do purposeful students perceive the role of sustainability in their lives? (semi-structured interview data)

2 Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

The data comprised a non-probability sample of students (N = 549) at the HUAS in their first year (n = 266, 48.5%), second year (n = 135, 25%), third year (n = 90, 16%) or fourth year of studies or above (n = 58, 13%). Over half reported female gender (n = 306, 56%), less than half male gender (n = 240, 44%) and a few reported other gender (n = 3, 0.5%). The fields of study included economics (n = 222, 40%), technology (n = 159, 29%), healthcare (n = 73, 13%), social and education studies (n = 70, 13%), and the arts (n = 20, 4%). Five students did not report their field of study. Most of the participants and their parents were born in The Netherlands (n = 317, 93% of the students responding to these questions), although it should be noted that 38 percent of the sample omitted the question.

2.2. Procedure

We adopted the mixed-methods approach because we wanted to study sustainability as a life purpose from three complementary perspectives. This served to yield a more holistic and more profound account than would have been possible using only one method. We initially used a convergent mixed-methods research design (Creswell Citation2015), meaning that quantitative and qualitative data were gathered simultaneously by means of a Qualtrics-online survey. Teachers at the HUAS distributed an anonymous link to students in 2019 and 2020. Participants received an information letter and provided informed consent before completing the survey. Participation was voluntary and the students were able to withdraw without any adverse consequences.

Second, we adopted an explanatory sequential approach (Creswell Citation2015), meaning that the results of the first part were discussed in semi-structured interviews with the participants. The selection of students for the interview was based on their purpose profiles emerging in the quantitative analysis and their willingness to participate, indicated in the survey by sharing their contact information. We interviewed two students per profile and report here the analysis of purposeful students (n = 2). We conducted the qualitative interviews between September 21 and November 18, 2020. Owing to the corona pandemic restrictions, we conducted six of the eight interviews online in a video meeting.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Quantitative instruments

presents the reliability and descriptive statistics of the scales measuring the purpose profiles (Bronk et al. Citation2018; Bundick et al. Citation2006). We measured the first dimension (meaningful intentions; Damon, Menon, and Bronk Citation2003) using five items of the Presence-of-purpose subscale of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (Steger et al. Citation2006). Examples include: ‘My life has a clear sense of purpose.’ ‘I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful.’

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the purpose profile scales.

The second dimension (commitment to the actualization of the purpose) was measured using nine items from the Purpose-in-Life subscale of the Scales of Psychological Well-being (Ryff Citation1989, Ryff and Keyes Citation1995). Examples include: ‘I am an active person in carrying out the plans I set for myself.’ ‘I enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them a reality.’ The Likert scale for the first and second dimensions ranged from one to seven (1 = Absolutely untrue/Strongly disagree, 7 = Absolutely true/Strongly agree).

We used four items of the Claremont Purpose Scale (Bronk et al. Citation2018) to measure the third beyond-the-self dimension. The items were formulated as questions, inviting the participants to respond on a Likert scale ranging from one to five (1 = Not at all important/Almost never, 5 = Extremely important/Almost all the time). Examples include: ‘How important is it for you to make the world a better place in some way?’ ‘How often do you hope that the work that you do positively influences others?’

2.3.2. Qualitative instruments

The survey also included open-ended questions (Magen Citation1998; Moran Citation2014) enabling respondents to describe and reflect on their life purposes in their own words. In this article, we analyze responses to the question: ‘What do you think is your life purpose, or the closest thing you have to a life purpose?’

The semi-structured interview guide included three main questions: What is important to you (your life purpose and your vision of society)? What kind of societal concerns do you have and how are you engaged in addressing them? How do you perceive the contribution of the HUAS to your civic engagement? The interviews lasted between 25 and 50 min (approximately 35 min on average) and were transcribed verbatim for the analysis.

2.4. Analyses

2.4.1. Analysis of the quantitative data

We identified the purpose profiles with K-cluster analysis utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics 25. The means of the variables shown in were standardized because the scales of the instruments differed. We tentatively tested three, four, and five clusters. After six iterative rounds, we chose the four-cluster solution as being theoretically the soundest model (Naes, Brockhoff, and Tomic Citation2010). We tested the differences between the clusters using one-way variance (ANOVA): the results appear in with the means of the original scales and standardized values. The clusters differed statistically significantly from each other in relation to the three dimensions of purpose, but with one exception: disengagement and self-orientation did not differ on the beyond-the-self dimension.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of the dimensions in each cluster and in the ANOVAs.

To triangulate the quantitative and qualitative data, we cross-tabulated the content categories and orientations with the purpose profiles and background variables. We applied the Chi-square test to measure the statistical significance.

OK

2.4.2. Analysis of the qualitative data

We coded the written statements according to the conventions of qualitative content analysis (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). We used the Excel program, coding every answer inductively in keeping with the content of the purposes identified. Each content item was further coded deductively to identify self- and beyond-the-self orientations (Damon, Menon, and Bronk Citation2003). Sustainability-related contents were also classified in line with the three pillars of sustainability (Goodland Citation1995; Purvis, Mao, and Robinson Citation2018). The following example of a written description illustrates the analysis:

Being happy and making the people around me happier [content: happiness; orientation: self & beyond-the-self] and making sure everyone is aware of environmental issues and doing something about them [content: sustainability –environment; orientation: beyond-the-self]. (ID 20358)

We analyzed the interviews by means of qualitative content analysis. First, we formed a general picture of the interviewees’ life purposes then selected for closer scrutiny in the more detailed case studies reported here two students with purposeful profiles whose interests were related to sustainability. In the next phase, three dimensions of the definition by Damon, Menon, and Bronk (Citation2003), the three pillars of sustainability (Goodland Citation1995; Purvis, Mao, and Robinson Citation2018), and three types of citizenship (Westheimer and Kahne Citation2004) guided the deductive analysis of the two interviews, the aim being to elucidate and explain the findings of the quantitative data. We present quotations from the interviews to illustrate the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Purpose profiles

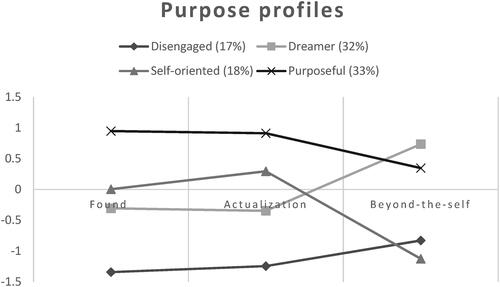

illustrates the four purpose profiles identified among the students, named according to Damon (Citation2008) and Moran (Citation2009). Over one-third (n = 142, 33%) of students’ responses fell under the category of purposeful, indicating that they had meaningful aspirations in their lives and were committed to their pursuit. They also wanted to make the world a better place, demonstrating a beyond-the-self orientation. The second largest group (n = 137, 32%) comprised dreamers, who scored highest on beyond-the-self orientations, thereby indicating their willingness to contribute to the wellbeing of others, while less certain of whether they had found their purpose or commitment to realizing their aspirations. These results show that over half (n = 279, 65%) of the participating students were interested in making the world a better place, potentially implying high-level awareness of sustainability.

Figure 1. Purpose profiles among Dutch higher education students: the means in the figure are standardized (z-scores).

The scores of the remaining students (n = 153, 35%) implied less interest in contributing to the welfare of others. The self-oriented group (n = 79, 18%) had identified some meaningful goals that engaged them, but their scores on contributing beyond-the-self were as low those of the disengaged students. Those in the disengaged group (n = 74, 17%) scored low on all three dimensions: they identified no aspirations making their lives meaningful and thus were not able to engage in any. Furthermore, they scored low on contributing to the world beyond-the-self.

3.2. Contents of the purposes emerging from the written descriptions

We initially report in general the contents of the life purposes the students included in their written descriptions (see ), and secondly in specific relation to sustainability. Most of the students (n = 216, 61% of those who described their life purposes) wanted to be happy, to pursue positivity, and to enjoy their lives. They aimed to complete their studies and find pleasant and meaningful work (n = 79, 22%). They wished to live life as they pleased, indicating the importance of self-actualization (n = 62, 18%) and self-development. Relationships (n = 69, 17%) mainly centered on having a family and finding a spouse. A few students mentioned economic or health-related goals, and three based their purpose on religious beliefs. Overall, the written statements highlighted self-orientation: 62 percent of the students (n = 217) mentioned contents of benefit to themselves alone. Nevertheless, a beyond-the-self orientation was associated with all content categories: the students also hoped for happiness for other people, (see Kuusisto and Tirri Citation2021). Moreover, sustainability was the only content category in which all the statements indicated a purely beyond-the-self orientation.

Table 3. Results of the qualitative content analysis.

Students mentioning sustainability-related contents as their life purpose (n = 78, 22%) referred mainly to social sustainability (n = 65), wishing to help people or to make the world a better place on a general level. Some of them gave details about whom and how they would like to help:

Thinking about the lonely elderly. (ID 20168)

Helping people with problems in life through music and coaching and physical exercise. (ID 20156)

My life purpose is to push the world forward into the future. Although it may be in the sense of making the planet more sustainable through evolution in technology or a revolution in contemporary thinking. (ID 20303)

Becoming a marine biologist so that I can focus on the future of our environment. (ID 20300)

I hope to contribute to making the world healthier through the better distribution of available resources. (ID 20336)

Improvement of health care in a continent such as Africa, especially in third-world countries. (ID 20506)

3.3. Sustainability in different profiles and fields of study

Next, we triangulated the purpose profiles, fields of study, and content categories. When we cross-tabulated the profiles with the fields of study, we found statistically significant differences (χ2(12) =29.485, p < .01). Close scrutiny of the standardized residuals revealed that technology students were more disengaged (standardized residual 2.7) and less purposeful (standardized residual −2.5) than students in other fields. The profiles in the written descriptions did not differ statistically significantly (), although we did detect some domain-specific differences in the content categories: students of social sciences and education placed more emphasis than others on relationships (χ2(4) =11.418, p < .05, standard residuals 2.6), and work (χ2(4) =10.536, p < .05, standard residuals 2.5). There were also statistically significant differences in happiness (χ2(4) = 11.397, p < .05), but none of the standard residuals exceeded |2| (MacDonald and Gardner Citation2000). The written statements revealed no differences related to the sustainability domains.

Table 4. Written responses in the different profiles.

3.4. Case studies of two purposeful students

3.4.1. Wiel – sustainability through personal responsibility

Wiel was a 26-year-old bachelor’s-level student in healthcare leading a busy life. He was studying to become a teacher of physical education. He did voluntary work in the community as a sports coach. He also had a part-time paid job for 20 h a week in business. Wiel emerged as purposeful in the survey although he did not write about his purpose in life. He mentioned in the interview that having a family was his ultimate purpose and that in order to realize this he needed to find the material means through work.

In Wiel’s case, sustainability was related to the social pillar in terms of family and working life, in which he highlighted his personal responsibility (Westheimer and Kahne 2004). For him, it was important to understand that all individuals have their own views on life and therefore need to be given space. Wiel emphasized the need to invest effort in high-quality social encounters on a personal and an individual level. He was also concerned about the increasing tendency towards individualization, which meant people concentrating only on themselves:

I think it’s very important […] that you show a certain commitment to what you do with each other, and I sometimes find it very individually focused, I also get the feeling that people are letting one another go a bit more.

3.4.2. Lyla – sustainability through participatory and justice-oriented actions

Lyla was a 20-year-old, active second-year student of technology living at home with her parents. She emerged as having a purposeful profile in the survey. Her written description of her purpose in life also revealed her goal-oriented attitude in aiming towards ‘Achieving my goals, such as my degree.’ This statement did not imply an interest in sustainability, but rather gave more of a self-oriented impression. However, the interview reflected her purposeful profile.

Lyla explained in the interview how her long-term goals related to sustainability, and how committed she was to contributing to it, for example, by doing voluntary work both in her community and at her university. Her purpose in life incorporated both the environmental and the social pillars: on the environmental level her concerns were about the climate and animals, and on the social level she cared about human rights. Lyla had clearcut ideas about what and how she wanted to contribute to making the world a better place. She perceived many opportunities for making positive and constructive changes. For example, showing her interest in contributing to the wellbeing of her peers; during the pandemic she actively promoted social sustainability together with her friend:

He suggested that maybe we could start a kind of survey in which we students would ask how you feel about how things are going now [during the pandemic]. So, we did that. Then we then sent the written report to our team leader, who sent it to the program committee [at the HUAS].

The above example further shows the value of contacting and collaborating with peers in learning to contribute. Lyla also acknowledged the influence of her parents in developing these attitudes and core beliefs, as they had encouraged her to think about things, to form her own opinions, and to act upon them. Lyla also expressed her disappointment that there was not much discussion with the teachers about sustainability at the HUAS:

In my opinion, school doesn’t spend a lot of time or effort on it [sustainability]. […] I think it would be nice to talk about it. I also think that such conversations would allow us to get to know each other a bit more, and so on, and you have, for example, in your Study Career Guidance group with your counselor you could very well have a conversation about it when the school year has just started, because then, you know, this sort of conversation is always good to have and you get to know each other better and I think that forms a good basis.

4. Discussion

This study investigated sustainability as a purpose in life among Dutch higher education students. We identified four purpose profiles: purposeful (33%), dreamer (32%), self-oriented (18%), and disengaged (17%). These profiles showed that over half of the participating students wanted to make the world a better place, indicating potential interest in and commitment to sustainability. This result could reflect the explicit aims of the HUAS, which encourages students to use their talents to improve the world, and to make a contribution in terms of resolving societal issues. However, the large number of dreamers implies that many of the students had not yet found ways to engage in realizing their visions and hopes, and that they needed more sustainability education focusing on insights into the root causes of the lack of sustainable development, concrete engagement options as well as opportunities to practice at different levels of society (Schutte Citation2017). It is particularly concerning that technology students were the most disengaged and the least purposeful. This result seems to reflect findings reported in earlier research acknowledging the need for both holistic and sustainability education, but also indicating its challenging nature in technology-related subjects (e.g. Hilty and Huber Citation2018).

The shares of students belonging to the various profiles differed from the findings of the study by Moran (Citation2009), with more students in the disengaged and dreamer profiles in the Dutch data, but fewer self-oriented and purposeful students. Some of these differences could be attributed to the diverse methodologies: in Moran’s study, the profiles were based on qualitative clinical interviews and in the present study on quantitative instruments.

We further examined the students’ life purposes by means of qualitative content analysis of their written statements. According to the results, happiness (61%), work (22%), and sustainability (22%) emerged most frequently. In spite of there being no statistically significant differences between the purpose profiles in the content categories, there were some statistically significant differences depending on the field of study. Students of social and education studies emphasized relationships and work more than did the other students, which closely reflects findings among Finnish student teachers (Kuusisto and Tirri Citation2021). The aspirations of the majority (62% of those returning written statements) were aimed solely at benefiting themselves, implying a more self-oriented picture than indicated in the profiles. Self-orientation in written responses has also been prevalent in Finnish studies using the same question (Kuusisto and Tirri Citation2021; Manninen, Kuusisto, and Tirri Citation2018). It should also be noted that almost a third (32%) of the students participating in the present study did not respond to the open-ended question, which may have affected the results.

Our particular interest in this study was to explore sustainability as a purpose in life. Sustainability occurred in 22 percent of the written descriptions. Sustainability was also among the most frequently mentioned contents in the purposeful and dreamer profiles, indicating alignment of the quantitative and qualitative results. Social sustainability was the most frequently occurring dimension: students wanted to help others and to make the world a better place. Environmental sustainability was at the core of their life purpose, especially among students whose future professions would enable them to make a meaningful contribution to the field, such as in architecture or marine biology. Economic sustainability was mentioned least, indicating low levels of awareness of economic inequalities in Dutch society, and between the global north and south. It may also be that the students perceived few opportunities to contribute to resolving economic inequalities as motivation to act presupposes a sense of efficacy or empowerment (Colby et al. Citation2003). Not even economics students seemed to differ on this issue, although this is hardly surprising in light of earlier studies. Business education in particular appears to foster selfish motives among students (Marathe, Dutta, and Kundu Citation2020).

We conducted case studies on two students, Wiel and Lyla, who emerged as purposeful in the survey and who revealed in the interviews that sustainability was at the core of their purpose in life. In Wiel’s case, this manifested in his social relations through personal responsibility in family and work contexts. Lyla, for her part, focused on sustainability in the environmental and social domains: her commitment and contributions were essentially participatory (Westheimer and Kahne Citation2004) through her influence in her community on the collective level, and in her university on the organizational level. She was also aiming at social justice in seeking and addressing the root causes of structural challenges (Westheimer and Kahne Citation2004), indicating a broader actualization of sustainability than in Wiel’s case. Lyla also addressed the pedagogical challenges of sustainability education in technology, which could explain the domain-specific differences in the purpose profiles.

Methodologically and in terms of triangulation, the interviews supported the validity of the profiles constructed with the quantitative instruments. However, Wiel had not written down his purposes at all and Lyla’s relatively brief description did not include sustainability or a beyond-the-self orientation, which in her interview proved to be the essence of her purpose. Open-ended questions in surveys have some inherent risk factors, which seemed to materialize in this study at least to some extent. Firstly, the responses were relatively short and concise, which is not necessarily problematic as such if the participants are motivated and able to convey their real thoughts in writing. Secondly, a significant proportion (32%) of the participants did not write anything or did not even finish the survey. These issues are problematic and require critical contemplation as to whether the survey was too long or too difficult to sustain the participants’ interest. Nevertheless, open-ended responses are potentially informative about people’s answering styles, and give a general picture of the contents of life purposes in the sample under study (Geer 1988). Any interpretation of the results should account for the fact that the findings cannot be generalized to all Dutch higher education students. It would be valuable in future studies with larger and more representative samples to triangulate the contents of purposes with a quantitative instrument, which requires careful instrument development to capture all the relevant aspects (Kuusisto and Tirri Citation2021). Therefore, as the interviews showed, the findings from the open-ended question should be treated with some caution: such questions clearly require more motivation, more effort, and reflection skills on the part of the participant than tick-box questions. It is demanding to explicitly summarize one’s thoughts in writing (Geer 1988). There are some reliability-related issues in these responses, however. In terms of content and length, they consistently resembled those reported in the Finnish studies by Kuusisto and Tirri (Citation2021) and Manninen, Kuusisto, and Tirri (Citation2018). Furthermore, Dutch students of social and education studies, including prospective elementary school teachers, highlighted the same contents as their Finnish peers.

It is always a challenge in mixed-methods studies to find different ways of capturing a phenomenon from various perspectives and to give a broader and more profound picture when the data sets are merged (Creswell Citation2015). It is, therefore, possible that not all the results are fully aligned: in the present study, the self- and beyond-the-self orientations manifested differently in the quantitative and qualitative data, for example. Overall, valid and reliable instruments have been under construction and topics of research projects (Bronk et al. Citation2018; Damon Citation2008) in studies on life purposes utilizing the framework by Damon, Menon, and Bronk (Citation2003). Given the results of the present study, this task has not yet been accomplished.

5. Concluding remarks

The realization of the United Nations’ (2015) Sustainable Developmental Goals has become a high priority in higher education in Western countries, as institutions develop courses and offer a general educational atmosphere that will engage students. The present study investigated the extent to which sustainability is a purpose in life among Dutch higher education students. The findings suggest a fairly positive situation as the majority of the HUAS students we investigated had found a meaningful purpose in life and fell into the purposeful or dreamer profiles in quantitative analysis, thereby suggesting their interest in making the world a better place. As exceptions to this, technology students did not seem to be as keen on contributing beyond-the-self as were students of other disciplines. Furthermore, general interest in sustainability did not figure equally clearly in the students’ own written statements, in which self-orientation was the dominant perspective and 22 percent explicitly mentioned sustainability-related issues as their purpose. Our case-study interviews shed more light on and confirmed a stronger commitment to sustainability than was apparent in the written descriptions. Overall, our results draw specific attention to the need to promote the holistic growth of students through ethics education, especially in the field of technology, directed towards reflecting on living a good life in which it is meaningful to contribute beyond the self (Colby Citation2020; Damon, Menon, and Bronk Citation2003; De Ruyter and Schinkel Citation2017): more effort is needed to incorporate sustainability into daily teaching, into the curriculum, and on the structural level to support holistic growth among students for a purposeful and sustainable future. Finally, the students did not yet seem to pay much attention to economic sustainability, in other words, the ethical and equal distribution of economic resources. Given the extensive socio-economic differences both within and between countries, a major challenge facing higher education is to purposefully promote economic sustainability.

Ethics declaration

The study followed ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research was assessed and approved by the Education chair group and the Executive Board of the University of Humanistic Studies, The Netherlands. Participants were asked to give their informed consent.

Notes on contributors

Dr Elina Kuusisto is a University Lecturer (diversity and inclusive education) at the Faculty of Education and Culture, Tampere University, Finland. She holds the title of Docent (Associate Professor) at the University of Helsinki, Finland. In 2018-2019, she worked as an Associate Professor at the University of Humanistic Studies, The Netherlands. Her academic writings deal with teachers’ professional ethics and school pedagogy, with a special interest in purpose in life, moral sensitivities, and a growth mindset.

Dr Ingrid Schutte is a Researcher and worked as an Educational Advisor until November 2021 at the Staff Office Education and Applied Research of the Hanze University of Applied Sciences. Her expertise includes diversity in education and personal and societal development of students. Her PhD research was about ethical sensitivity and developing global civic engagement in undergraduate honors students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bronk, K. C. 2014. Purpose in Life: A Critical Component of Optimal Youth Development. New York, NY: Springer.

- Bronk, K. C., B. R. Riches, and S. A. Mangan. 2018. “Claremont Purpose Scale: A Measure That Assesses the Three Dimensions of Purpose among Adolescents.” Research on Human Development 15 (2): 101–117. doi:10.1080/15427609.2018.1441577.

- Bundick, M., M. Andrews, A. Jones, J. Menon Mariano, K. C. Bronk, and W. Damon. 2006. Revised Youth Purpose Survey. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

- Colby, A. 2020. “Purpose as a Unifying Goal for Higher Education.” Journal of College and Character 21 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1080/2194587X.2019.1696829.

- Colby, A., T. Ehrlich, E. Beaumont, and J. Stephens. 2003. Educating Citizens. Preparing America’s Undergraduates for Lives of Moral and Civic Responsibility. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Creswell, J. W. 2015. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- De Ruyter, D. J., and A. Schinkel. 2017. “Ethics Education at the University: From Teaching an Ethics Module to Education for the Good Life.” Bórdon 69 (4): 125–138.

- Damon, W. 2008. The Path to Purpose. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Damon, W., J. Menon, and K. C. Bronk. 2003. “The Development of Purpose during Adolescence.” Applied Developmental Science 7 (3): 119–128. doi:10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_2.

- Elo, S., and H. Kyngäs. 2008. “The qualitative content analysis process.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–115.

- Geer, J. G. 1988. “What Do Open-Ended Questions Measure?” Public Opinion Quarterly 52 (3): 365–367. doi:10.1086/269113.

- Goodland, R. 1995. “The Concept of Environmental Sustainability.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 26 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.000245.

- Hallinger, P., and C. Chatpinyakoop. 2019. “A Bibliometric Review of Research on Higher Education for Sustainable Development, 1998–2018.” Sustainability 11 (8): 2401. doi:10.3390/su11082401.

- Hanzehogeschool Groningen, 2021. Betrokken en Wendbaar. Strategisch Beleidsplan 2021-2026. https://www.hanze.nl/assets/strategisch-beleids-plan/Documents/Public/HAN3039_BRO_StrategischBeleidsplan-NL-Digi_A4_fc_14_KJ.pdf

- Hedayati, N., E. Kuusisto, K. Gholami, and K. Tirri. 2017. “Life Purposes of Iranian Secondary School Students.” Journal of Moral Education 46 (3): 283–294. doi:10.1080/03057240.2017.1350148.

- Higher Education Law, article 1.3.5. 1992. Accessed 23 June 2021, https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0005682/2020-08-01#Hoofdstuk1

- Hilty, L. M., and P. Huber. 2018. “Motivating Students on ICT-Related Study Programs to Engage with the Subject of Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 19 (3): 642–656. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-02-2017-0027.

- Jiang, F, and D. Gao. 2018. “Are Chinese Student Teachers’ Life Purposes Associated with Their Perceptions of How Much Their University Supports Community Service Work?” Journal of Moral Education 47 (2): 201–216. doi:10.1080/03057240.2018.1430023.

- Kool, A., and I. Schutte, eds. 2016. The Colour Palette. Guidelines for Personal and Social Development. Internal Publication Hanze University of Applied Sciences. Groningen: Hanze University of Applied Sciences.

- Kopnina, H. 2018. “Teaching Sustainable Development Goals in The Netherlands: A Critical Approach.” Environmental Education Research 24 (9): 1268–1283. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1303819.

- Kuusisto, E., and K. Tirri. 2021. “The Challenge of Educating Purposeful Teachers in Finland.” Education Sciences 11 (1): 29. doi:10.3390/educsci11010029.

- MacDonald, P. L., and R. C. Gardner. 2000. “Type 1 Error Rate Comparisons of Post Hoc Procedures for I J Chi-Square Tables.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 60 (5): 735–754. doi:10.1177/00131640021970871.

- Magen, Z. 1998. Exploring Adolescent Happiness: Commitment, Purpose, and Fulfilment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Manninen, N., E. Kuusisto, and K. Tirri. 2018. “Life Goals of Finnish Social Services Students.” Journal of Moral Education 47 (2): 175–185. doi:10.1080/03057240.2017.1415871.

- Marathe, G. M., T. Dutta, and S. Kundu. 2020. “Is Management Education Preparing Future Leaders for Sustainable Business? Opening Minds but Not Hearts.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 21 (2): 372–392. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-02-2019-0090.

- Moran, S. 2009. “Purpose: Giftedness in Intrapersonal Intelligence.” High Ability Studies 20 (2): 143–159. doi:10.1080/13598130903358501.

- Moran, S. 2014. How Service-Learning Influences Youth Purpose around the World, Student Semester Start Survey. Worcester, MA: Clark University.

- Moran, S. 2019. “Is Personal Life Purpose Replacing Shared Worldview as Youths Increasingly Individuate? Implications for Educators.” International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 18 (5): 8–23. doi:10.26803/ijlter.18.5.2.

- Naes, T., P. B. Brockhoff, and O. Tomic. 2010. “Cluster Analysis: Unsupervised Classification.” In Statistics for Sensory and Consumer Science, 249–261. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Pashby, K., and V. de Oliveira Andreotti. 2016. “Ethical Internationalisation in Higher Education: Interfaces with International Development and Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 22 (6): 771–787. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1201789.

- Purvis, B., Y. Mao, and D. Robinson. 2018. “Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins.” Sustainability Science 14: 681–695.

- Ryff, C. D. 1989. “Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57 (6): 1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

- Ryff, C. D., and C. L. M. Keyes. 1995. “The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69 (4): 719–727. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719.

- Schutte, I. 2017. “Ethical Sensitivity and Developing Global Civic Engagement in Undergraduate Honors Students.” Doctoral diss., University of Humanistic Studies, The Netherlands. Repository UVH. https://repository.uvh.nl/uvh/bitstream/handle/11439/3095/dissertatie%20Ingrid%20Schutte%20Ethical%20sensitivity%20and%20developing%20global%20civic%20engagement.pdf?sequence=1.

- Schutte, I., and R. Van der Lei. 2018. “Bildung ontrafeld: het Kleurenpalet Persoonlijke en Maatschappelijke Vorming.” OnderwijsInnovatie 4. https://onderwijsinnovatie.ou.nl/oi-december-18/bildung-ontrafeld/overlay/pmv-bij-de-hanze-verder-lezen/.

- Steger, M. F., P. Frazier, S. Oishi, and M. Kaler. 2006. “The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 53 (1): 80–93. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80.

- Sumner, R., A. L. Burrow, and P. L. Hill. 2018. “The Development of Purpose in Life among Adolescents Who Experience Marginalization: Potential Opportunities and Obstacles.” The American Psychologist 73 (6): 740–752. 10.1037/amp0000249.

- United Nations. 2015. “General Assembly Resolution a/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.”

- Van Poeck, K., A. König, and A. E. J. Wals. 2018. “Environmental and Sustainability Education in the Benelux Countries: Research, Policy and Practices at the Intersection of Education and Societal Transformation.” Environmental Education Research 24 (9): 1234–1249. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1477121.

- Westheimer, J., and J. Kahne. 2004. “Educating the “Good” Citizen. Political Choices and Pedagogical Goals.” Political Science and Politics 2: 241–247.