Abstract

Young people and educators in the UK have called for changes in the education system to better prepare learners for a future shaped by climate change and our collective response to the climate crisis. This research explored both reported climate education practices and future outlooks through a questionnaire completed by 16–18-year-old secondary school students (n = 512) and teachers (n = 69) in England. The research participants had mixed emotions about the future, and rated negative future scenarios as more likely than positive scenarios. This is the first study in the UK to directly measure climate hope and action competence using recently developed and validated questionnaires, finding a strong positive correlation between hope and action competence. Replicating previous research, the reported teacher practices that best predicted student-reported hope were 1) accepting negative emotions and 2) maintaining a positive outlook, which was further explored through the model of emotionally-mediated education for climate action. In this study, a complicated picture emerges in which hope and anxiety coexist, and both have a relationship with students’ reported environmental action.

We can no longer let the people in power decide what hope is. Hope is not passive. Hope is not ‘bla, bla, bla’. Hope is telling the truth. Hope is taking action (Thunberg Citation2021).

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on the physical science of climate change combines the state of our knowledge of the Earth’s climate system and human-induced climate change with a series of future scenarios, emphasising that climate change is shaping the future (Masson-Delmotte et al. Citation2021). Education is concerned with preparing students for the future, with Biesta (Citation2020) arguing that the function of education can be understood as a combination of qualification, socialisation, and subjectification. This raises a question: how can our educational systems effectively prepare young people for a future shaped by climate change and our collective response to the climate crisis?

For educators, effective climate education involves more than expertise in a specific subject; it requires new pedagogical approaches (Monroe et al. Citation2019; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). Educators also need to be aware of the emotional landscape of climate change – a number of recent commentaries in medical journals highlight concerns about high levels of climate anxiety among young people (Godlee Citation2021; Rao and Powell Citation2021; Wu, Snell, and Samji Citation2020). This study of 16–18-year-olds in England and their teachers seeks to better understand:

the future outlook of students, as reflected in their ratings of future scenarios, hope, distress, and action competence,

the relationship between teacher practices, the future outlook of students, and student participation in school sustainability activities and environmental protest.

Climate education is an emerging field of education research and practice with origins in environmental and sustainability education and strong links to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Facer et al. Citation2020; Reid Citation2019). This research explores emerging themes in climate education that are of interest both to governments responding to calls for education reform and to educators experimenting with new pedagogical approaches. It is the first study of UK youth to directly measure climate hope and action competence using recently developed and validated scales.

The paper begins with a background section reviewing relevant literature in climate education, hope and action competence. A methodology section follows with the research questions, more details about the students and teachers in England that participated in the research, and the elements of the questionnaire used to collect the data. The results section describes the findings with respect to the research questions, and the paper concludes with a discussion of key themes, noting the study limitations and potential directions for future research.

Background

Young people and climate change

The United Nations defines ‘youth’ as people between the ages of 15 and 24 years old. The 1.2 billion young people born between 1997 and 2006 make up 16% of the global population in 2022 (United Nations Citationn.d.). They were born after scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change, and after governments had begun to make commitments to tackle the crisis; the IPCC was created in 1988 and released the first two Assessment Reports in 1990 and 1995, while the UNFCCC was adopted in 1992, followed by the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. Atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased from 367 to 420 parts per million and average global temperatures have risen by 0.5 degrees Celsius from 1997 to 2022 (Scripps Citation2022; Met Office Citation2022). For 15–24-year-olds, the threat of climate change, and the reality of increasing greenhouse gas emissions and rising global temperatures, has been present their entire lives.

Previous research has found that young people have similar knowledge and attitudes with respect to climate change when compared to older age groups (Corner et al. Citation2015). However, more recent studies indicate a sharp rise in a sense of urgency and anxiety among youth, with a large-scale global survey finding that 69% of respondents under 18 years old believe climate change is an emergency, compared to 58% of the respondents over 60 years old, and a large international study of youth reporting that 84% of respondents were worried about climate change, with 59% very or extremely worried (Flynn et al. Citation2021; Hickman et al. Citation2021).

This generational concern is reflected in the Fridays for Future school strikes, which at their peak in September 2019 attracted over 6 million young people and their supporters worldwide (Taylor, Watts, and Bartlett Citation2019). The influence of the latest wave of the youth climate movement is illustrated by recent research on the ‘Greta Thunberg Effect’ in the United States – familiarity with the Swedish teenager and climate activist predicted intention to participate in collective action to mitigate climate change across all ages (Sabherwal et al. Citation2021).

Future scenarios

Future scenarios have played a critical role in climate science and policy, describing different potential socioeconomic pathways and their associated greenhouse gas emissions (O’Neill et al. Citation2020). Scenarios describing pathways that limit climate change are related to sociotechnical imaginaries, a concept in science and technology studies (STS). ‘Imaginaries, in this sense, at once describe attainable futures and prescribe futures that states believe ought to be attained’ (Jasanoff and Kim Citation2009, 120). Anticipating the future can also take different forms: calculating futures using models, imagining futures through visualisation and storytelling, and performing futures with simulations (Anderson Citation2010).

Climate and geography education researchers have long advocated for developing ‘futures literacies’ (Facer and Sriprakash Citation2021; Hicks and Holden Citation1995; Morgan Citation2015). In a study of Swedish students, researchers argued for education for sustainable development involving ‘future teaching based on possible, probable and preferable futures’ (Torbjörnsson and Molin Citation2014, 273). In a recent study of environmental and sustainability education in Germany, students and teachers rated a series of scenarios in terms of desirability and likelihood, with both groups pessimistic about futures shaped by climate change, social inequality and digitisation (Grund and Brock Citation2019).

Climate hope

The concept of hope has been explored by a number of influential educational theorists. Dewey (Citation2008, 294) distinguished hope from optimism, arguing that optimism ‘encourages a fatalistic contentment with things as they are’ while hope – or what the pragmatists called meliorism – is an active process, in which ‘by thought and earnest effort we may constantly make better things’. Freire (Citation2014, 2–3) also commented on the relationship between hope and action: ‘That is why there is no hope in sheer hopefulness. The hoped-for is not attained by dint of raw hoping. Just to hope is to hope in vain’.

Snyder’s hope theory defines three components of hope: goal identification and a combination of pathways thinking and agency thinking – ‘the perceived capacity to use one’s pathways to reach desired goals’ (Snyder Citation2002, 251). A number of researchers have applied hope theory to environmental and sustainability education, often in response to concerns about climate anxiety among children (Kelsey and Armstrong Citation2012; Kerret et al. Citation2020; Ojala Citation2017). Ojala (Citation2012) created a survey to capture climate hope through questions exploring three concepts: trust in one’s ability to influence environmental problems in a positive direction, trust in others, and positive reappraisal, which involves thinking differently about environmental problems in a way that activates hope. Building on the measures developed by Ojala, Li and Monroe (Citation2018) developed a scale to measure climate hope among teenagers organised around Snyder’s hope theory, with components covering what they describe as willpower (agency thinking) and waypower (pathways thinking) at both a personal and collective level.

Ojala (Citation2012) also makes a distinction between constructive hope – the ability to identify and pursue alternative pathways to reach desired goals – and climate change hope based on denial, which represents a lack of concern about the future as a result of climate scepticism. In non-academic writing, similar concepts have been explored using the phrase active hope (Macy and Johnstone Citation2012). In a study of Swedish high school students, Ojala (Citation2015) found constructive hope was higher when teachers accepted their students’ negative emotions about social and environmental problems, while also maintaining a positive and solution-oriented outlook in the classroom. Kerret et al. (Citation2020) investigated hope-enhancing programmes at schools in Israel, concluding that more research was required in terms of how to best design school activities to enhance environmental hope.

Action competence

While much research in environmental education attempts to measure specific pro-environmental behaviours, this study instead explores the more generalised and future-oriented concept of action competence. Action competence was developed by Danish environmental and health education researchers in reaction to shortcomings of both knowledge-based approaches that fail to achieve desired changes in behaviour and behaviour modification campaigns that manipulate students into choosing a set of predetermined pro-environmental behaviours (Jensen and Schnack Citation1997).

Action competence is defined as, ‘a critical, reflective and participatory approach by which the developing adult can cope with future environmental problems’ (Breiting and Mogensen Citation1999, 350). While the definition and utility of action competence continues to be debated, this approach to environmental and sustainability education relates to scientific literacy and self-efficacy (Bandura and Cherry Citation2020; Bishop and Scott Citation1998; Chawla and Cushing Citation2007; Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; Sass et al. Citation2020). In developing a tool to measure self-perceived action competence for sustainability, Olsson et al. (Citation2020) use a theoretical model with three components: knowledge of action possibilities, confidence in one’s own influence, and willingness to act.

There is clear potential overlap between the sub-constructs of action competence and the dimensions of hope identified above, especially in terms of pathways and agency thinking, and the relationship between these two concepts is explored in more depth in this study. While Olsson et al. (Citation2020) maintain a distinction between the concepts of hope and action competence when referencing Li and Monroe (Citation2018) hope scale, Ojala (Citation2015) recognises the similarities: ‘there is a close relation between action competence and hope concerning global futures’ (135). Li and Monroe (Citation2018) also called for more research into the relationship between hope and action competence: ‘Future research could also look at how the hope scale relates to climate change action competence among young people to find out whether this hope scale is a motivational force’ (474).

Climate education

Article 12 of the UNFCCC Paris Agreement reinforces the importance of climate education as part of an agenda of action for climate empowerment (United Nations Citation2015). The education system has also been identified as a critical social tipping point for achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming (Otto et al. Citation2020). Improving climate education was a key recommendation of both the UK Climate Assembly and a summit of Education and Environment Ministers at the 26th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP26) in Glasgow, as well as at a number of recent youth-driven events (Climate Assembly UK Citation2020; Finnegan Citation2021; Mock COP2626 Citation2021; United Nations Citation2021; Youth4Climate Citation2021).

As an emerging field of research and practice, there is still some debate about what constitutes good climate education (Reid Citation2019). A review of climate education research reported that, ‘top-down, science-based approaches in formal educational settings [are] continuing to dominate the field of climate change education’ while calling for an approach that ‘empowers children and young people to meaningfully engage with entanglements of climate fact, value, power, and concern across multiple scales and temporalities’ (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020, 12–13). Researchers in Finland have developed a new conceptual model of holistic climate change education using the metaphor of a bicycle, with the handlebars representing future orientation and the light attached to the handlebars representing hope and other emotions (Cantell et al. Citation2019). In a call to action that has been repeated by other researchers, Kagawa and Selby (Citation2010) direct climate education towards the future: ‘the learning moment can be seized to think about what really and profoundly matters, to collectively envision a better future, and then to become practical visionaries in realizing that future’ (4–5).

In the UK, the youth-led Teach the Future campaign has crafted a climate education bill to update the national curriculum (Harvey Citation2022). Their recent survey of 4,690 secondary school teachers in England found that only a third felt that climate change was meaningfully embedded in the curriculum for their subject (Teach the Future Citation2022). Another recent study of teachers in England found they supported interdisciplinary and action-oriented climate education (Howard-Jones et al. Citation2021).

Educators and learners who are calling for educational reform to improve climate education need to know how best to create meaningful educational experiences. This research picks up on that call with the goal of untangling the relationship between hope and action competence and exploring how teachers can educate for both.

Research questions

This study is part of a larger research project exploring how secondary schools in England are responding to the climate crisis and preparing young people for the future. The specific research questions driving this study are:

How can we better understand the future outlook of students by exploring their ratings of future scenarios, hope, distress, and action competence?

What is the relationship between teacher practices, the future outlook of students, and student participation in school sustainability activities and environmental protest?

Methodology

The research was approved by the Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC) at the University of Oxford, with reference number SOGE20201A-178.

Participants

In this study, 512 sixth form students and 69 secondary school teachers in England completed an online questionnaire delivered through Microsoft Forms. Sixth form is the traditional name for the final two years of secondary school in England, also known as Year 12 and Year 13, and the students ranged in age from 16 to 18 years old. The survey was conducted in 2021 and the majority of the participants were from twelve secondary schools in Greater London and the Thames Valley Region (Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire), which were evenly split between state (government funded) and independent (privately funded) schools. The study used a combination of convenience sampling, recruiting schools based on geography and participation in networks related to sustainability, snowball sampling (as teachers were initially recruited in each school and they shared the questionnaire with their students and other teachers) and voluntary response sampling (as the survey respondents were recruited differently in each school, for example through a geography class, tutor group, or cross-curricular activities, and their participation was usually voluntary). Any submissions to the online survey that were outside England or outside the age range of 16 to 18 were excluded from this analysis.

Sixty-five percent of the students were in Year 12; during Year 13 students prepare for and take their A-Level exams (the sixth form leaving qualification), which most likely accounts for the smaller percentage. The breakdown of students by age was 26% 16, 52% 17, and 22% 18, with a mean age of 16.96. Sixty-seven percent of the students identified as female (three of the twelve secondaries were girls’ schools), 1% chose the gender category ‘other’, and 2% withheld information about their gender. Seventy-eight percent of the students identified as white, which is slightly lower than the percentage of white 16-to-19–year-olds in England and Wales (82%) according to the 2011 Census (Office for National Statistics Citation2021). The number of students that completed the survey was almost evenly split between state (51%) and independent (49%) schools, while only 13% of A-Level students in England attend independent schools (Department for Education Citation2021a). is a cross-tabulation of the number of students by school type, gender and age.

Table 1. Cross-tabulation showing number of students by school type, gender and age.

In the analysis that follows, survey responses were compared across these identified subgroups (school type, age, gender, ethnicity) and are reported when statistically significant. In comparisons based on gender, ‘other’ and ‘prefer not to say’ were not included due to the small number in each category. The online survey did not capture the school name or any specific information about the school location, so no geographic comparisons can be made.

The teachers that responded to the survey are more heavily skewed towards independent schools at 71%. Ninety percent of the teachers identified as white, and 62% as female; for reference, the 2020 School Workforce Census of state schools in England found that 85% of teachers identified as white and 75% as female (Department for Education Citation2021b). The teachers in this study were a mix of new and experienced teachers: 28% were in their first five years of teaching, while a quarter had been teaching for more than 20 years, with a third of the teachers in their thirties and 29% in their fifties. The teachers represented a wide range of subjects: 48% STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) more than half of which were biology and chemistry teachers, 33% humanities, and 14% social sciences, including geography.

Given the smaller sample of teachers, and the fact that it is heavily skewed towards independent schools, the analysis below doesn’t break teachers into subgroups. The responses of teachers were compared to students, and reported below when statistically significant.

Questionnaire

outlines the different sections of the questionnaire, including the number of questions, themes and calculations, sources, and whether they applied to students or teachers. The survey primarily used questions that were developed and validated through previous research, as indicated in the table below.

Table 2. Questionnaire components.

Recent studies have included more sophisticated surveys of climate anxiety, including cognitive and functional impairment, but these studies were published after this research began so did not influence the design of the questionnaire (Clayton and Karazsia Citation2020; Hickman et al. Citation2021). The questions about negative emotions were adapted from studies of participants in the 2019 school climate strikes (Wahlström et al. Citation2019; Wahlström et al. Citation2020). These responses were used to measure Climate Change Distress (CCD) based on the similar calculation by Searle and Gow (Citation2010).

Future scenarios were adapted from the short narratives in Grund and Brock (Citation2019). This section of the questionnaire included brief instructions to picture the world in 50 years and then rate each scenario in terms of likelihood and desirability. The positive climate scenario read:

The importance of climate change was recognised by all sectors of society. Curbing it has become top priority resulting in a stable Earth system.

Climate change and its consequences could not be contained in time by an altering course in politics, business and individual behaviour. This led to severe ecological crises and to massive economic declines, as well as a severe decrease of quality of life for the majority of people.

Positive scenario likelihood − negative scenario likelihood

As noted in , the variation of the questionnaire for teachers did not include the questions on emotional support or outlook (in which students rated their teachers) and the two questions about student activities.

The data is available on the Oxford Research Archive for Data (https://doi.org/10.5287/bodleian:kKZRkMBMy). Both the full questionnaire, which includes some questions not included in this study, and a Jupyter Notebook of the data analysis (Python) are also available via the link above as related items.

When comparing mean values of scales for different segments of the research participants, only statistically significant comparisons are reported below, and data was tested for normality and variance. When indicating the strength of association from correlation analysis, the general guidelines of Campbell and Swinscow (Citation2009) are followed: r of 0 to .19 is very weak, .2 to .39 is weak, .40 to .59 is moderate, .6 to .79 is strong and .8 to 1 is very strong.

Results

This section is organised based on the two research questions above, beginning with a descriptive analysis of student future outlook.

The future outlook of students: hope, action competence, distress, and future scenarios

To explore this first research question, we will look at the Climate Change Hope Scale (CCHS), Climate Change Distress (CCD) score, Climate Change Scenario Rating (CCSR) and Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability Questionnaire (SPACS-Q). For each calculation, there is a statistically significant difference based on gender, which is presented in .

Table 3. Climate hope, distress, scenario ratings, and action competence of students, compared by gender.

According to the CCHS, the students were slightly hopeful, with a mean score above 1 on a scale of −3 to 3, and 94% of students scoring above zero. Two-sided independent T-tests were used to compare CCHS scores of teachers and students, and different subgroups of students. Teachers were moderately more hopeful (M = 1.68, SD = 0.75) than students (M = 1.39, SD = 0.76); t(579) = 2.97, p < 0.01. Students that identified as female were more hopeful than students that identified as male (see ). A one-way ANOVA calculated for the three age groupings also found statistical significance, with CCHS scores decreasing with age when comparing 16-year-olds (M = 1.57, SD = 0.70) to 17-year-olds (M = 1.30, SD = 0.76) and 18-year-olds (M = 1.39, SD = 0.78); F(2, 509) = 5.53, p < 0.01.

The Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability Questionnaire (SPACS-Q) scores follow a similar pattern to CCHS. With respect to the mean scores on a scale of 1 to 5, teachers have a higher SPACS-Q scores (M = 3.86, SD = 0.46) than students (M = 3.61, SD = 0.57); t(561) = −3.48, p < 0.001. Students that identify as female rate higher than students that identify as male (see ). Younger students have slightly higher scores when comparing 16-year-olds (M = 3.71, SD = 0.53) to 17-year-olds (M = 3.57, SD = 0.56) and 18-year-olds (M = 3.58, SD = 0.62); F(2, 509) = 3.01, p < 0.05.

In the questionnaire, students also reported how much they felt a series of negative emotions with respect to climate change. Combining the ‘quite’ and ‘very much’ responses, the strongest feelings are anxiety (68%), worry (68%), frustration (67%), anger (58%), and fear (57%). The only emotions that a majority of respondents didn’t strongly feel were powerless (48%) and hopeless (38%). These emotions were also used to calculate CCD, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90 indicating high internal consistency. Students reported moderate levels of CCD, and students that identified as female had higher levels of CCD than students that identified as male (see ). There also is a slight difference in distress reported by ethnicity, with students from ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities) reporting lower levels of CCD (M = 3.40, SD = 1.08) than white students (M = 3.68, SD = 0.91); t(510) = 2.79, p < 0.01.

A fourth reference point was provided by the ratings of the likelihood and desirability of positive and negative climate change scenarios adapted from Grund and Brock (Citation2019). A Pearson correlation of responses to both climate scenarios finds a negative relationship between likelihood and desirability for students (r = −.360, p < 0.001) and teachers (r = −.348, p < 0.001) which indicates they have a negative view of the future – desirable scenarios are rated as less likely, undesirable scenarios are rated as more likely. Looking more closely at the likelihood ratings on a scale of 1 to 7, the students rated the negative scenario (M = 4.82, SD = 1.36) as more likely than the positive scenario (M = 3.76, SD = 1.44). A similar pattern exists between the teacher ratings of the likelihood of the negative scenario (M = 5.03, SD = 1.28) versus the positive scenario (M = 3.65, SD = 1.62). As explained above, we can also subtract the negative scenario likelihood from the positive scenario to calculate the CCSR, and the majority of both students (59%) and teachers (61%) had a negative outlook. The only statistically significant difference on CCSR values is based on gender, with students that identify as female having slightly more negative outlooks than students that identify as male (see ).

The relationship between climate hope and action competence

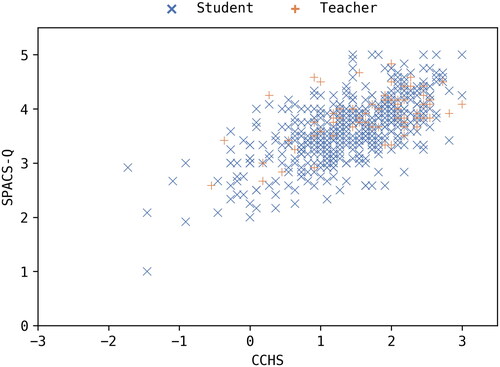

Given the similarities between the conceptual frameworks, questionnaires, and descriptive results for the measurements of climate hope and action competence, this relationship was further investigated. presents the Pearson correlation coefficients for the student scores for CCHS, SPACS-Q, and their respective subscales. This analysis indicates a very strong correlation between the two scales (r = .648, p < 0.001), which means that the more the students have hope about climate change, the more probable it is that they also have a high rating of self-perceived action competence. This relationship is illustrated in . The strongest correlation across the two scales is between the overall SPACS-Q score and the personal-sphere willpower and waypower (PW) component of CCHS scale (r = .683, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Student and teacher scores for the Climate Change Hope Scale (CCHS) and Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability Questionnaire (SPACS-Q).

Table 4. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) for student climate hope, action competence, and subscales.

This exploration of the relationship between climate hope and action competence, as reflected in CCHS and SPACS-Q, was motivated by the similar conceptual framework of the two measures and potentially overlapping questions. This strong correlation between SPACS-Q and both overall CCHS and the PW component of CCHS indicates that action competence is strongly related to the personal dimension of climate hope.

Feelings about the future

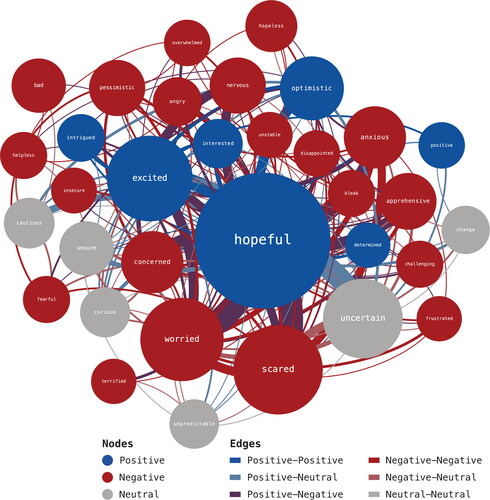

In addition, we can explore both positive and negative emotions through responses to the open-ended question: How do you feel about the future? Please use only three words. Five words appeared in over 10% of the student responses: hopeful (30%), scared (15%), excited (14%), worried (13%) and uncertain (12%). The phrases were coded to indicate if the overall sentiment was positive, negative, neutral or mixed. 36% of the student responses were mixed – including both positive and negative words – while 35% were negative, 19% were positive, and 10% were only neutral words. It is worth noting that earlier references to climate hope describe a cognitive concept, as reflected in Snyder’s hope theory and the Climate Change Hope Scale, however the student responses of ‘hopeful’ for this question can be understood as a positive emotional response.

A matrix of co-occurring words was used to visualise these responses as a network, with individual words as ‘nodes’ and co-occurring pairs as ‘edges’ (the connections between nodes). The most common combinations were hopeful and scared (5%), hopeful and worried (5%), hopeful and uncertain (5%), and hopeful and excited (3%). For readability, the Gephi network visualisation in only includes words that were repeated at least 5 times, and the proportional size of nodes is not to scale.

Figure 2. Network of co-occurring words in response to the open-ended question: How do you feel about the future? Please use only three words.

The young people in this study have mixed emotions about a future shaped by climate change and our response to the climate crisis. With respect to measures of hope, they are moderately hopeful about the future; teachers appear to be more hopeful than their students, students that identify as female are more hopeful than students that identify as male, and younger students are more hopeful than older students. Students also report worry, anxiety, frustration, anger and fear about the future, and are moderately distressed about climate change, with students that identify as female more distressed than students that identify as male, and white students more distressed than ethnic minorities. Both students and teachers rated a negative future scenario which would lead ‘to severe ecological crises and to massive economic declines, as well as a severe decrease of quality of life for the majority of people’ as more likely than a positive climate scenario.

Teacher practices, the future outlook of students, and student participation in school sustainability activities and environmental protest

The components of the questionnaire related to teacher practices allow us to investigate the second research question. The results of four of these measures indicated statistically significant differences by school type, which are presented in .

Table 5. Student perception of teacher emotional support and outlook, and teaching about the future and sustainable development pathways, compared by school type.

Students reported that teachers were more likely to be accepting of negative emotions regarding societal and environmental issues (M = 3.37, SD = 0.92) than dismissive (M = 2.04, SD = 0.89). Students also reported that their teachers were more likely to maintain a positive and solution-oriented outlook in the classroom (M = 3.20, SD = 0.89) than a negative outlook (M = 2.29, SD = 0.92). Teachers rated their instruction as more oriented to the future (M = 2.56, SD = 0.68) than students rated their teachers (M = 2.17, SD = 0.74); t(579) = 4.11, p < 0.001. Bringing together these teacher practices with CCHS and SPACS-Q, shows the results of a Pearson correlation analysis.

Table 6. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) for teacher practices and student climate change hope and action competence.

The teacher practices that had the strongest correlation with student-reported climate hope were accepting negative emotions expressed by students and maintaining a positive and solution-oriented outlook in the classroom. This relationship is even stronger with respect to action competence – implying that teachers that accept negative emotions and maintain a positive outlook are more likely to have students with higher levels of both climate hope and action competence. These results also indicate differences based on school type, with all four positive teacher practices reported more strongly at independent schools than at state schools.

Turning to self-reported student action, rather than ask about specific pro-environmental behaviours, the questionnaire included more general questions about student participation in school sustainability activities, like an eco-club, and environmentally-themed protests, such as the Fridays for Future climate strikes.

43% of students reported that they had never participated in school sustainability activities and 56% had never participated in environmental protests. This also means that the majority of students have participated to some extent in school sustainability activities and a large percentage have attended at least one environmental protest. presents the mean values of the student responses using the four-point frequency scale – never (1), seldom (2), sometimes (3), often (4) – grouped by school type and gender. presents a Pearson correlation analysis of these student activities and the hope, distress, competence, and future orientations scores.

Table 7. Mean values (and standard deviation) of student self-reported participation in school sustainability and environmental protest by school type and gender.

Table 8. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) for school sustainability, environmental protest, hope, action competence, distress, future outlook.

This finding confirms the basic premise of action competence – higher levels of self-perceived action competence translate to higher frequencies of environmental action. The impact of climate hope and distress on action appears to be more complicated, as the strongest correlation for protest activity was with climate distress, while school sustainability activity was more strongly correlated with hope than distress. Of course, the causality of these relationships is not clear, as climate hope, for example, could be interpreted as motivating school sustainability activity, or participation in school activities might engender climate hope. The scenario rating, which reflects student assessments of the likelihood of a positive climate future, does not appear to have any relationship with environmental action.

Education for climate action mediated by the future outlook of students

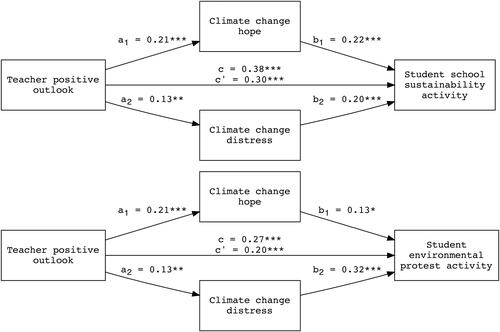

Further investigating the relationship between teacher practices, student outlook, and action, a model in which both climate hope and distress were analysed as mediators between teacher practices and student action was developed. Maintaining a positive and solution-oriented outlook was the teacher practice most strongly correlated with student participation in both school sustainability (r = .317; p < 0.001) and environmental protest (r = .249; p < 0.001) and was used as the independent variable in this model, with both student activities as the dependent variables, and climate hope and distress serving as mediators (see ). In terms of the other elements of future outlook described above, the scenario rating did not have strong enough relationships with the dependent or independent variables to be included as a mediator, and action competence and climate hope were too closely correlated to include both as mediators.

Figure 3. Mediation analysis diagram of the impact of teachers’ positive and solution-oriented outlook on both students’ school sustainability and environmental protest activity, mediated by climate hope and distress.

Note. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The mediation analysis was conducted by calculating the ordinary least squares linear regression to identify the relationships between the different variables in the model. The β coefficient from linear regression between teacher positive outlook and student participation in school sustainability activities is 0.38 (c in ), which means an increase in the positive outlook score by 1 predicts an increase in school sustainability activity by 0.38 (p < 0.001). The adjusted R2, or coefficient of determination, for this relationship is 10%, indicating that 10% of the variation in student school sustainability activity can be explained by this relationship with teachers’ positive outlook.

Next, linear regression was calculated between the independent variable and both mediators (a1 and a2 in ), and between both mediators and the dependent variable (b1 and b2 in ). The indirect or average causal mediation effect is the product of the β coefficient for each of these moderators (a# × b#) which was 0.05 for hope and 0.03 for distress. When included in the model, these indirect effects decrease the direct prediction by teacher practice to 0.30 (c’ in ) while increasing adjusted R2 to 16%, meaning the inclusion of the mediating variables of climate hope and distress increased the predictive power of the model.

Performing the same calculations with the dependent variable as environmental protest, the β coefficient decreased from 0.27 to 0.20 (p < 0.001), with the indirect effect from hope equal to 0.03 and the indirect effect from distress equal to 0.04, and adjusted R2 increased from 6% to 18%. The mediation model was run with 10,000 bootstrap iterations for the confidence intervals and p-value estimations.

This mediation analysis indicated that climate hope and distress contribute to the relationship between teacher practices and student action, with hope playing a larger role in motivating school sustainability activity and distress playing a larger role in environmental protest activity. It is important to note that cross-sectional data is used to test this theoretical model in terms of these relationships. Future longitudinal and experimental research would be required to confirm these relationships and the direction of influence or causality.

Discussion

This study set out to triangulate the assessment of climate hope among sixth form students in England with ratings of the likelihood and desirability of positive and negative future scenarios, as well as negative emotions captured by climate change distress. Students had moderately high levels of both hope and distress, and negative future outlooks. Mixed emotions towards the future were also reflected in the network analysis of the open-ended response capturing their feelings about the future. While the pessimism reflected in the ratings of future scenarios appear to contradict the findings of moderately high levels of hope, these results may actually reflect an aspect of hope – one can maintain a high level of hope that a positive outcome is possible while still believing that a negative outcome is more likely than a positive outcome. Also worthy of note is that students that identified as female had higher ratings of both climate hope and climate distress compared to students that identified as male, although researchers have identified similar gender differences in young people’s emotional expression beyond environmental issues (Chaplin and Aldao Citation2013).

In addition, this study used recently developed and validated scales for hope and action competence to explore the relationship between these concepts. As noted above, there was a strong positive correlation between hope and action competence, as captured by Climate Change Hope Scale (CCHS) and Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability Questionnaire (SPACS-Q). When extending this analysis to the sub-components of each scale, there was a strong positive correlation between the overall SPACS-Q score and the personal-sphere willpower and waypower subscale of CCHS. Given the similar conceptual frameworks and questions used in each scale, this association is not unexpected, but it does indicate a strong relationship between the personal dimension of climate hope and the concept of action competence.

Another concern of this study is what teachers can do in the classroom to support hope and action competence in their students. Replicating research with Swedish teenagers (Ojala Citation2015), this study found a positive correlation in England between student hope and teachers accepting negative emotions and maintaining a positive and solution-oriented outlook with respect to social and environmental problems. This correlation is notable as the original study did not use the CCHS to assess hope, indicating a durable relationship between these practices and the concept of climate hope. Future research could investigate a more extensive series of teacher practices (beyond the six measures identified in in the rows labelled educator practices part 1 and 2) developed in collaboration with educators, resulting in practical guidance for climate education.

The questions related to teaching practices also revealed a potential divide between independent schools and state schools, as the students at independent schools reported higher levels of future orientation, sustainable development pathways, positive outlook, and acceptance of negative emotions. There were no significant differences between students from state and independent schools when it came to their responses for hope, distress, future scenarios, and action competence. Private education has been identified as a major factor perpetuating educational inequality in the UK (Farquharson, McNally, and Tahir Citation2022). Independent schools have more flexibility in the classroom, as they are not required to follow the national curriculum of England, and have more resources – an average of £6,500 more per pupil per year compared to state schools – which helps explain the higher ratings of teacher practices in this study. Given the differences between privately-funded and government-funded education, as well as the differences in class and socio-economic privilege of the respective student populations, the similarities in the cognitive and emotional scores for students across school types is notable and worthy of additional research. In addition, the schools included in this study were based in Greater London and Southeast England, and future research could compare students and teachers from different regions of the United Kingdom.

While hope and action competence are oriented to the future, this study also explored the relationship between these two concepts and climate action today. Action competence, as measured by the SPACS-Q, was one of the main predictors of reported participation in both school sustainability activities and environmental protests. Distress was more likely to predict participation in environmental protests. Hope was an additional predictor of participation in school sustainability activities. In an attempt to weave together teacher practices, climate hope and distress, and student action, this research included the development of a model of emotionally-mediated education for climate action. While the model only partially explained the relationship between the independent variable of teacher positive outlook and dependent variables of student sustainability activities, the mediation analysis confirmed that emotions have a mediating effect, with the indirect effect of climate change hope being larger than climate change distress when motivating school sustainability activity. The opposite is true of environmental protest activity – climate change distress has a larger average causal mediation effect than climate change hope. As this is only cross-sectional data, these results should be interpreted as a preliminary test of the model, and longitudinal or experimental studies would be required to confirm this causality.

Hope is often conceived of as in opposition to – or a remedy for – anxiety when it comes to climate change. However, a more complicated picture emerged from this research in which hope and distress coexist, and both have a relationship with environmental action. Studies of public health campaigns utilising fear appeals have identified an important relationship between threat and efficacy when it comes to message effectiveness, and this may also be true of emotionally-mediated climate education (Peters, Ruiter, and Kok Citation2013; Tannenbaum et al. Citation2015). The lack of a relationship between future outlook, as captured by the future scenarios, and environmental action may also indicate that pessimism about the distant future is somewhat universal, as both hopeful and hopeless students (as well as both students participating in climate action and those not participating) believe a negative future is more likely than a positive one. Future research into both climate hope and anxiety could provide important insights into the complex interactions between anxiety and hope for the future, and how these translate into, and are shaped by, climate action.

There are a number of limitations to this study. The questionnaire for this study was distributed during a school year disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns, online learning, and disruptions to school activities and exams may have impacted the young people’s perceptions of the future. The impact of the pandemic on young people may have resulted in more negative outlooks, and the long-term relationship between the pandemic and youth climate attitudes and action is worthy of additional research. However, interest in and concern about climate change may have remained high during the pandemic, especially as this study was preceded by a new wave of youth climate activism and followed by the high profile COP26 events in the UK.

The online questionnaire did not track the individual schools, which made it impossible to know the response rate for each school, or the specific number of respondents outside the twelve schools with which the researcher directly communicated. While the students were evenly split between state and independent schools, this does not reflect the proportion of sixth form students in privately funded education in England, which is only 13%. The students were also not demographically representative of young people in England in terms of gender; two-thirds of the students identified as female, as a number of the schools engaged in the research were girls’ schools, and students that identify as female may have been more likely to choose to participate in the research. 3% of the students chose the gender category ‘other’ or withheld information about their gender, and these students aren’t included in the analysis by gender above. The combination of convenience, snowball and voluntary response sampling limit the strength of the results, as students with higher levels of interest in climate may have been more likely to complete the survey.

Finally, in terms of the findings of this study, the strong correlation between climate hope and action competence can be explained by the similar conceptual models and questionnaires, and therefore is not a particularly surprising result. And, as noted above, the mediation model uses cross-sectional rather than longitudinal or experimental data, and therefore cannot be used to confirm causal relationships.

Conclusion

The cognitive and emotional landscape of climate change is complicated, especially for young people looking ahead to a future shaped by this issue. As the model of emotionally-mediated education for climate action illustrates, hope and distress are both fuelling climate action of different sorts, and both may be necessary to respond to this time of crisis and shape a positive future.

In this study, previously developed and validated surveys were used to further investigate the relationship between hope and action competence (Li and Monroe Citation2018; Olsson et al. Citation2020). Any future development of these questionnaires would benefit both from integrating these two survey instruments and by incorporating additional concepts such as collective action competence and positive reappraisal (Clark Citation2016; Ojala Citation2012). A comprehensive tool that assesses both hope and distress, especially cognitive and functional impairment as a result of climate anxiety, would be invaluable to better understand the complicated relationship between climate hope, distress and action (Clayton and Karazsia Citation2020). In terms of climate action, this study had a novel focus on exploring how young people collectively participate in systems change in their schools and communities, rather than just exploring individual pro-environmental actions.

For teachers, this research replicated the finding that accepting negative emotions and maintaining a positive outlook correlates with students expressing climate hope. It is worth noting the importance of both of these practices – educators that aspire to maintain a positive outlook when teaching about climate change should take care not to dismiss the negative emotions that students might express in the classroom. Emotional support provided by teachers is an emerging theme in environmental and climate education research and practice (O’Hare et al. Citation2020; Ojala Citation2021). Teachers should also actively engage young people in talking about the future that they want and how they can shape it, as this is not currently happening despite calls for futures literacies by researchers and interest from students (Hicks and Holden Citation1995; Facer and Sriprakash Citation2021).

Constructive hope can be understood as a stance towards the future in which we believe a positive future is possible, but not a given, and each of us are called to shape that future. That is where action competence comes in, as it represents the skills and competencies required to navigate future challenges and act sustainably. Teachers who want to support hope should look to the long tradition of action competence in environmental education, which has a strong relationship with the personal dimension of climate hope. Educating for hope and action competence involves engaging young people with the future, creating space for them to express the negative emotions generated by the climate crisis, and maintaining a positive and solution-oriented outlook in the classroom. The climate resilience of young people involves experiencing both climate hope and distress, and harnessing these cognitive and emotional responses for action. Educators play an essential role in supporting young people as they develop this resilience and maintain constructive hope.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, B. 2010. “Preemption, Precaution, Preparedness: Anticipatory Action and Future Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 34 (6): 777–798. doi:10.1177/0309132510362600.

- Bandura, A, and L. Cherry. 2020. “Enlisting the Power of Youth for Climate Change.” The American Psychologist 75 (7): 945–951. 10.1037/amp0000512.

- Biesta, G. 2020. “Risking Ourselves in Education: Qualification, Socialization, and Subjectification Revisited.” Educational Theory 70 (1): 89–104. doi:10.1111/edth.12411.

- Bishop, K, and W. Scott. 1998. “Deconstructing Action Competence: Developing a Case for a More Scientifically-Attentive Environmental Education.” Public Understanding of Science 7 (3): 225–236. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/7/3/002.

- Breiting, S, and F. Mogensen. 1999. “Action Competence and Environmental Education.” Cambridge Journal of Education 29 (3): 349–353. doi:10.1080/0305764990290305.

- Campbell, M. J, and T. D. V. Swinscow. 2009. Statistics at Square One. 11th ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell/BMJ Books.

- Cantell, H., S. Tolppanen, E. Aarnio-Linnanvuori, and A. Lehtonen. 2019. “Bicycle Model on Climate Change Education: Presenting and Evaluating a Model.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 717–731. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1570487.

- Chaplin, T. M, and A. Aldao. 2013. “Gender Differences in Emotion Expression in Children: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Psychological Bulletin 139 (4): 735–765. 10.1037/a0030737.

- Chawla, L, and D. F. Cushing. 2007. “Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior.” Environmental Education Research 13 (4): 437–452. doi:10.1080/13504620701581539.

- Clark, C. R. 2016. “Collective Action Competence: An Asset to Campus Sustainability.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 17 (4): 559–578. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-04-2015-0073.

- Clayton, S, and B. T. Karazsia. 2020. “Development and Validation of a Measure of Climate Change Anxiety.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 69: 101434. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434.

- Climate Assembly UK. 2020. The path to net zero: Climate Assembly UK full report. House of Commons. https://www.climateassembly.uk/recommendations/index.html

- Corner, A., O. Roberts, S. Chiari, S. Völler, E. S. Mayrhuber, S. Mandl, and K. Monson. 2015. “How Do Young People Engage with Climate Change? The Role of Knowledge, Values, Message Framing, and Trusted Communicators.” WIREs Climate Change 6 (5): 523–534. doi:10.1002/wcc.353.

- Department for Education. 2021b. School workforce in England, Reporting Year 2020, June 17. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-england

- Department for Education. 2021a. A level and other 16 to 18 results, Academic Year 2020/21. Accessed 2 December2021 https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/a-level-and-other-16-to-18-results

- Dewey, J. 2008. The Middle Works. 7: 1912–1914: [Essays, Book Reviews, Encyclopedia Articles in the 1912–1914 Period, and Interest and Effort in Education]. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Facer, K., L.-S. Heila, A. Ogbuigwe, C. Vogel, and S. Barrineau. 2020. “TESF Briefing Paper: Climate Change and Education (2.0.).” Zenodo doi:10.5281/ZENODO.3796143.

- Facer, K, and A. Sriprakash. 2021. “Provincialising Futures Literacy: A Caution against Codification.” Futures 133: 102807. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2021.102807.

- Farquharson, C., S. McNally, and I. Tahir. 2022. Education Inequalities (IFS Deaton Review of Inequalities). Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://ifs.org.uk/inequality/chapter/education-inequalities/

- Finnegan, W. 2021. Climate Futures Youth Perspectives—Cumberland Lodge Report 2021. Cumberland Lodge. https://www.academia.edu/52420246/Climate_Futures_Youth_Perspectives_Cumberland_Lodge_Report_2021

- Flynn, C., E. Yamasumi, S. Fisher, D. Snow, Z. Grant, M. Kirby, P. Browning, M. Rommerskirchen, and I. Russell. 2021. Peoples’ Climate Vote. United Nations Development Programme and University of Oxford. https://www.undp.org/publications/peoples-climate-vote

- Freire, P., A. M. A. Freire, and P. Freire. 2014. Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Bloomsbury.

- Godlee, F. 2021. “A World on the Edge of Climate Disaster.” BMJ 375: n2441. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2441.

- Grund, J, and A. Brock. 2019. “Why We Should Empty Pandora’s Box to Create a Sustainable Future: Hope, Sustainability and Its Implications for Education.” Sustainability 11 (3): 893. doi:10.3390/su11030893.

- Harvey, F. 2022. “UK Pupils Failed by Schools’ Teaching of Climate Crisis, Experts Say.” The Guardian, January 28. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/jan/28/uk-pupils-failed-by-schools-teaching-of-climate-crisis-experts-say

- Hickman, C., E. Marks, P. Pihkala, S. Clayton, R. E. Lewandowski, E. E. Mayall, B. Wray, C. Mellor, and L. van Susteren. 2021. “Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey.” The Lancet Planetary Health 5 (12): e863–e873. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

- Hicks, D, and C. Holden. 1995. “Exploring the Future: A Missing Dimension in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 1 (2): 185–193. doi:10.1080/1350462950010205.

- Howard-Jones, P., D. Sands, J. Dillon, and F. Fenton-Jones. 2021. “The Views of Teachers in England on an Action-Oriented Climate Change Curriculum.” Environmental Education Research 27 (11): 1660–1680. doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.1937576.

- Jasanoff, S, and S.-H. Kim. 2009. “Containing the Atom: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and Nuclear Power in the United States and South Korea.” Minerva 47 (2): 119–146. doi:10.1007/s11024-009-9124-4.

- Jensen, B. B, and K. Schnack. 1997. “The Action Competence Approach in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 3 (2): 163–178. doi:10.1080/1350462970030205.

- Kagawa, F., and D. Selby. eds. 2010. Education and Climate Change: Living and Learning in Interesting Times. New York; London: Routledge.

- Kelsey, E., and C. Armstrong. 2012. “Finding Hope in a World of Environmental Catastrophe.” In Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change, edited by A. E. J. Wals, 187–200. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. doi:10.3920/978-90-8686-757-8_11.

- Kerret, D., H. Orkibi, S. Bukchin, and T. Ronen. 2020. “Two for One: Achieving Both Pro-Environmental Behavior and Subjective Well-Being by Implementing Environmental-Hope-Enhancing Programs in Schools.” The Journal of Environmental Education 51 (6): 434–448. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1765131.

- Li, C, and M. C. Monroe. 2018. “Development and Validation of the Climate Change Hope Scale for High School Students.” Environment and Behavior 50 (4): 454–479. doi:10.1177/0013916517708325.

- Macy, J, and C. Johnstone. 2012. Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in without Going Crazy. Novato, Calif: New World Library.

- Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, Ö. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou. eds. 2021. “Summary for Policymakers.” In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Met Office. 2022. Met Office Climate Dashboard. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/monitoring/dashboard.html.

- Mock COP26. 2021. “Conference Declaration,” December. Mock COP. http://www.mockcop.org/treaty/

- Mogensen, F, and K. Schnack. 2010. “The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/13504620903504032.

- Monroe, M. C., R. R. Plate, A. Oxarart, A. Bowers, and W. A. Chaves. 2019. “Identifying Effective Climate Change Education Strategies: A Systematic Review of the Research.” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 791–812. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842.

- Morgan, J. 2015. “Making Geographical Futures.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (4): 294–306. doi:10.1080/10382046.2015.1086133.

- O’Hare, A., R. B. Powell, M. J. Stern, and E. P. Bowers. 2020. “Influence of Educator’s Emotional Support Behaviors on Environmental Education Student Outcomes.” Environmental Education Research 26 (11): 1556–1577. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1800593.

- O’Neill, Brian C., Timothy R. Carter, Kristie Ebi, Paula A. Harrison, Eric Kemp-Benedict, Kasper Kok, Elmar Kriegler, et al. 2020. “Achievements and Needs for the Climate Change Scenario Framework.” Nature Climate Change 10 (12): 1074–1084. 10.1038/s41558-020-00952-0.

- Office for National Statistics. 2021. Population by Ethnicity, Age and Sex—Office for National Statistics. Accessed 5 October 2021 https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/populationbyethnicityageandsex

- Ojala, M. 2012. “Hope and Climate Change: The Importance of Hope for Environmental Engagement among Young People.” Environmental Education Research 18 (5): 625–642. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.637157.

- Ojala, M. 2015. “Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations with Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation.” The Journal of Environmental Education 46 (3): 133–148. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662.

- Ojala, M. 2017. “Hope and Anticipation in Education for a Sustainable Future.” Futures 94: 76–84. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2016.10.004.

- Ojala, M. 2021. “Safe Spaces or a Pedagogy of Discomfort? Senior High-School Teachers’ Meta-Emotion Philosophies and Climate Change Education.” The Journal of Environmental Education 52 (1): 40–52. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1845589.

- Olsson, D., N. Gericke, W. Sass, and J. Boeve-de Pauw. 2020. “Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability: The Theoretical Grounding and Empirical Validation of a Novel Research Instrument.” Environmental Education Research 26 (5): 742–760. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1736991.

- Otto, I. M., J. F. Donges, R. Cremades, A. Bhowmik, R. J. Hewitt, W. Lucht, J. Rockström, et al. 2020. “Social Tipping Dynamics for Stabilizing Earth’s Climate by 2050.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (5): 2354–2365. 10.1073/pnas.1900577117.

- Peters, G.-J Y., R. A. C. Ruiter, and G. Kok. 2013. “Threatening Communication: A Critical Re-Analysis and a Revised Meta-Analytic Test of Fear Appeal Theory.” Health Psychology Review 7 (Suppl 1): S8–S31. 10.1080/17437199.2012.703527.

- Rao, M., and R. A. Powell. 2021. “The Climate Crisis and the Rise of Eco-Anxiety.” BMJ Opinion,October 6. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/10/06/the-climate-crisis-and-the-rise-of-eco-anxiety/

- Reid, A. 2019. “Climate Change Education and Research: Possibilities and Potentials versus Problems and Perils?” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 767–790. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1664075.

- Rousell, D, and A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles. 2020. “A Systematic Review of Climate Change Education: Giving Children and Young People a ‘Voice’ and a ‘Hand’ in Redressing Climate Change.” Children’s Geographies 18 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1080/14733285.2019.1614532.

- Sabherwal, A., M. T. Ballew, S. Linden, A. Gustafson, M. H. Goldberg, E. W. Maibach, J. E. Kotcher, J. K. Swim, S. A. Rosenthal, and A. Leiserowitz. 2021. “The Greta Thunberg Effect: Familiarity with Greta Thunberg Predicts Intentions to Engage in Climate Activism in the United States.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 51 (4): 321–333. doi:10.1111/jasp.12737.

- Sass, W., J. Boeve-de Pauw, D. Olsson, N. Gericke, S. De Maeyer, and P. Van Petegem. 2020. “Redefining Action Competence: The Case of Sustainable Development.” The Journal of Environmental Education 51 (4): 292–305. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1765132.

- Scripps. 2022. “The Keeling Curve.” The Keeling Curve. https://keelingcurve.ucsd.edu

- Searle, K, and K. Gow. 2010. “Do Concerns about Climate Change Lead to Distress?” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2 (4): 362–379. doi:10.1108/17568691011089891.

- Snyder, C. R. 2002. “Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind.” Psychological Inquiry 13 (4): 249–275. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01.

- Tannenbaum, M. B., J. Hepler, R. S. Zimmerman, L. Saul, S. Jacobs, K. Wilson, and D. Albarracín. 2015. “Appealing to Fear: A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeal Effectiveness and Theories.” Psychological Bulletin 141 (6): 1178–1204. 10.1037/a0039729.

- Taylor, M., J. Watts, and J. Bartlett. 2019. “Climate Crisis: 6 Million People Join Latest Wave of Global Protests.” The Guardian, September 27. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/27/climate-crisis-6-million-people-join-latest-wave-of-worldwide-protests

- Teach the Future. 2022. “Our Research.” Accessed 31 January https://www.teachthefuture.uk/research

- Thunberg, G. 2021. “We Can No Longer Let the People in Power Decide What Hope Is. Hope is Not Passive. Hope Is Not Blah Blah Blah. Hope Is Telling the Truth. Hope Is Taking Action.” My speech at #Youth4Climate #PreCOP26 in Milan. September 28. https://t.co/BA62GpST2O [Tweet]. @GretaThunberg. https://twitter.com/GretaThunberg/status/1442860615941468161

- Torbjörnsson, T, and L. Molin. 2014. “Who is Solidary? A Study of Swedish Students’ Attitudes towards Solidarity as an Aspect of Sustainable Development.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 23 (3): 259–277. doi:10.1080/10382046.2014.886153.

- United Nations. n.d. Youth. United Nations; United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth

- United Nations. 2015. Paris Agreement. Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1. https://unfccc.int/process/conferences/pastconferences/paris-climate-change-conference-november-2015/paris-agreement

- United Nations. 2021. Co-Chairs conclusions of Education and Environment Ministers Summit at COP26. UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) at the SEC – Glasgow 2021, November 5. https://ukcop26.org/co-chairs-conclusions-of-education-and-environment-ministers-summit-at-cop26/

- Wahlström, M., J. de Moor, K. Uba, M. Wennerhag, M. De Vydt, P. Almeida, A. Baukloh, et al. 2020. “Surveys of Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 20–28 September, 2019, in 19 Cities around the World.” doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/ASRUW.

- Wahlström, M., P. Kocyba, M. De Vydt, J. de Moor, P. Adman, P. Balsiger, A. Buzogany, et al. 2019. “Fridays for Future: Surveys of Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European Cities.” doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/XCNZH.

- Wu, J., G. Snell, and H. Samji. 2020. “Climate Anxiety in Young People: A Call to Action.” The Lancet Planetary Health 4 (10): e435–e436. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30223-0.

- Youth4Climate. 2021. Youth4Climate Manifesto. UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021 in Partnership with Italy. https://ukcop26.org/pre-cop/youth4climate-2021/