Abstract

The aim of this article is to present a case study in the field of ESD for in-service teachers training conducted in a Swiss primary school . A Discursive Community of Interdisciplinary Practices (DCIP) has been created including researchers, teachers, and a pedagogical advisor in the context of ESD, focusing on the topic of chocolate. In this article, we discuss how the DCIP helped teachers to develop competencies in the field of ESD. Furthermore, we see how teacher training could lead to a transformation of teachers’ practices, moving from a normative education to a more reflexive one. We present the collaborative research and its theoretical context. The analysis of focus group discussions evidenced an evolution of ESD teachers’ points of view. The analysis of the teachers’ comments highlights the potential of the methods implemented to help teachers to enter into the process of conceptualizing knowledge in terms of ESD.

1. Introduction

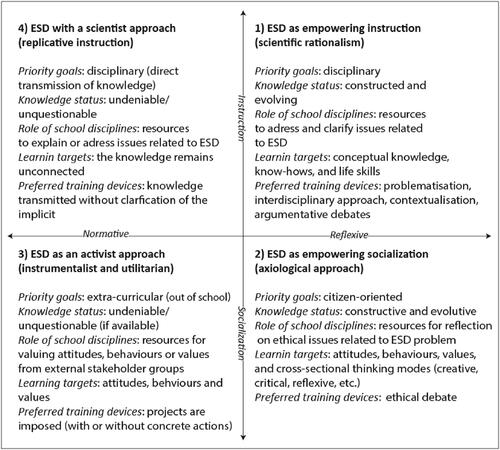

This article reports on the results from the implementation of a Discursive Community of Interdisciplinary Practices (DCIP)Footnote1 in the field of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)Footnote2. The main goal of this community was to study the reflection tools supporting investigation used by teachers to work on and grasp complex social objects and situations. In addition, the community aimed to create and test a new teaching approach to help a team of in-service primary school teachers to develop their pupils’ abilities in order to comply with the requirements of the ESD curriculum. There, teaching ESD in an emancipatory instructional and socialization perspective (infra, right side of the ) is a new approach for teachers (Roy & Gremaud. 2017). The implementation of this DCIP is part of a projectFootnote3 conducted in a Swiss primary school. Fifteen teachersFootnote4, four researchers from the Universities of Education in Geneva, Lausanne and Fribourg as well as a pedagogical advisor were involved in this community.

Figure 1. Four possible theoretical configurations of the relationship between school disciplines and ESD issues, adapted from Roy and Gremaud (2017, p. 104). This figure provides the background for possible approaches to teaching ESD (cf. supra).

The main challenge of the DCIP was to engage teachers in an interdisciplinary problem-solving approach in the field of ESD. In this article, we discuss how teacher trainingFootnote5 can transform teachers’ practicesFootnote6, moving from normative education to reflexive education with the goal of fostering empowerment. We also describe the implementation of the collaborative research project and present its theoretical foundations. An analysis of (ante and post) focus group discussions reveals how the teachers’ practices changed with regard to ESD.

1.1. Challenges associated with ESD

During the last decades, ‘Éducations à…’Footnote7 have been developed to fulfil the social needs (Hägglund and Pramling-Samuelsson Citation2009) put forward by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (ONU Citation2002, UNESCO Citation2014) and embedded in the curricula of many school systems Lebrun et al. Citation2019, Audigier Citation2015). In the Swiss curriculum, ESD is defined as a cross-curricular domain of education and is described as ‘socially, economically and environmentally interdependent’ (Conférence Intercantonale de l’Instruction Publique de la Suisse romande et du Tessin Citation2003). In an analysis of the ‘Éducations à…’ concept, Audigier (Citation2015) explains that school has to give ‘priority to knowledge that is oriented towards decision-making and action, towards developing attitudes and social behaviours, which is expressed by the term competencies’. He explains that ‘knowledge, know-hows, attitudes, projects, actions… are a ‘reality’ in a situation (…) [and] the social situations experienced by individuals, groups, citizens are not related to disciplines’ (2001 in Audigier Citation2015, p. 10). However, he also points out the necessity of finding new ways of harnessing school subjects in the context of ESD. Indeed, ESD ‘requires the creation of a conceptual framework that allows individuals to read about and understand phenomena occurring across the world’ (Diemer and Marquat Citation2016). ESD is ‘a polysemous, complex object, structured on the basis of knowledge, practices, values and demands which are in flux’ (Matagne Citation2013). Matagne notes that ‘educating in sustainable development also means educating in complexity’. Diemer and Marquat (Citation2016) define ESD as a sub-topic of global education within ‘Educations à’, arguing that ESD requires ‘mobilisation of various types of knowledge and their interrelationships in order to gain an understanding of complex problems’ (p. 43). In this education context, an interdisciplinary approach seems particularly relevant for studying ESD and for fostering the development of complex thinking (Audigier, Citation2015, Hertig Citation2016) because ‘it is a process aiming to develop the ability to analyse and synthesise from the perspective of several disciplines’ (Diemer and Marquat Citation2016, p. 43). For these authors, interdisciplinarity consists in ‘treating a problem as a whole, identifying and integrating all the relationships between the different elements involved’ (p.43). In relation to this theoretical and conceptual framework in relation to, we sought to develop a framework for analysing different teaching practices and discourses related to ESD (with the aim of developing new forms of thinking).

1.2. ESD as an interdisciplinary problem-solving approach

Since ESD differs from school disciplines ‘by the absence of an academic referent and therefore of a clearly established curriculum’ (Lange and Victor Citation2006, p. 87), it poses specific challenges for teachers in compulsory schools. In particular, it requires teachers to plan teaching sequences in an interdisciplinary way. It also requires a better understanding of the role that school disciplines, and in particular their knowledge, play in addressing sustainability issues in the classroom.

These challenges are all related to the interdisciplinary nature of ESD. The role of constructing problems in the classroom is therefore a central step for teachers who want their pupils to understand complex subjects or situations in a scientific manner. Many authors agree that the ability to construct problemsFootnote8 is pivotal in the context of ESD (Sgard and Janzi Berhnardt Citation2013). In our DCIP, the problematisation phase has been particularly worked with and by the teachers. Indeed, the problem construction is necessary to enter into the process of investigation for teachers (planification) and their students (learning process).

Sgard and Janzi Berhnardt have asked ‘how can we ensure that a class takes part in the process of identifying problems and constructing questions, in the preliminary examination of what a problem is about before seeking answers?’. Fabre (Citation2015), on the other hand, questions the very nature of ESD, arguing that problem construction enables teachers to avoid stating their own solutions and imparting ‘good habits’ to their students (e.g. the habit of separating waste). For example, Thémines (Citation2012) stresses that themes such as sustainable development or globalisation could be the starting point for problem construction in the context of geography education, adding that ‘what is taught is the result of a process of reconciliation, of bringing together elements from distinct and independent spheres of knowledge and action’ (p.7). In the same vein, Lange (Citation2014) notes that ‘the need for dialectical thinking is at the heart of non-normative ESD, as there is a need to overcome the gaps, tensions and contradictions that characterise sustainable development situations’ (§18). In the context of the humanities and social sciences, Audigier (Citation2015) highlights that ‘it is necessary to take real social situations as a starting point, to identify the vital issues at stake for the present and future of our societies and humanity, to analyse them, to formulate, investigate and validate appropriate responses’ (p.10). Finally, Thémines (Citation2012, p. 6) acknowledges that ‘the cultural challenge of constructing problems (Orange Citation1997) is that students adopt a discipline-specific point of view on topics or issues that are not necessarily discipline-related’. Thereby, the study of a social situation in the context of ESD allows the mobilisation, construction and introduction of knowledge from many different subject areas (e.g. the social sciences, such as Geography and History, together with the natural sciences). Although the objects and situations addressed in the context of ESD are related to different subject areas, an interdisciplinary approach to problem construction (Roy & Gremaud Citation2017) can help primary school teachers to better understand the aims of ESD.

1.3. The challenge of school disciplines contributing to dealing with ESD issues

When considering ESD in the primary school classroom, it is important to examine the role school disciplines play in dealing with a problem. It is clear that school disciplines have a substantial impact, in particular in the natural sciences, humanities and social sciencesFootnote9. As highlighted by Lebrun et al. (Citation2019, p. 2), ‘the disciplines aim to establish a different way of questioning the world (introduction to the disciplines’ principles of intelligibility), to develop cross-curricular learning of an intellectual, methodological and social nature and to empower students to cope with their everyday and professional life’. The authors discuss the interrelationships between school subjects, such as the natural sciences, the humanities and ‘Educations à…’. They note that the natural and social science disciplines aim to build a new way of questioning the world, to develop cross-disciplinary learning of an intellectual, methodological and social nature, and to equip pupils to face their future life. However, Roy and Gremaud (Citation2017) point out that the ways in which school disciplines deal with an ESD problem vary depending on ‘the main aim, the value of subject-specific knowledge, the role of school disciplines, the intended learning outcome in the subject and the favoured teaching methods’ (p. 104). Thus, the authors propose a model () with four possible theoretical configurations representing the relationships between school subjects and ESD problems in order to characterise the possible teaching practices of teachers in this field. In particular, their model highlights the educational objectives which are prioritised depending on the different approaches adopted by teachers. These approaches may range from being normative to reflective and be combined with a subject-specific or social focus. The model proposes the following four configurations: on the right side, a reflexive education with: (1) ESD as empowering instruction (scientific rationalism) and (2) ESD as empowering socialisation (axiological approach); on the left side, a normative education with: (3) ESD as an activist approach (instrumentalist and utilitarian) and (4) ESD with a scientist approach (replicative instruction).

In our study, we used this model as a framework to analyse the teachers’ discourse about their practices and intentions. The aim of the article is to report on how teachers’ instruction practices changed during the course of the collaborative research project, which took the form of a Discursive Community of Interdisciplinary Practices. We were, in particular, interested in investigating the following question: How did the methodological inputFootnote10 and joint development of an interdisciplinary investigation approach enable teachers to change their ESD teaching practices and their perception of ESD?

1.4. The discursive community of interdisciplinary practices (DCIP)

A Discursive Community of Interdisciplinary Practices (DCIP) was created to explore how teachers can approach ESD with pupils at different grade levels of primary school (4 to 12 years old). Researchers, pedagogical advisors, and teachers worked together with the purpose of formulating, elaborating, and resolving teaching and learning problems in the field of ESD (Roy and Gremaud Citation2017). Another aim was to develop a teacher training intervention to transform the teachers’ practices and perceptions, moving from normative education towards reflexive education with the goal of fostering empowerment (Roy & Gremaud, Citation2017). In addition to investigating interdisciplinary practices, the study also aimed to open teachers’ minds to the complexity of sustainability. Finally, the researchers wanted to analyse the impact of the DCIP on the teachers. The DCIP draws on the methodology of cooperative didactic engineering (Joffredo Le Brun et al., Citation2018; Ligozat and Marlot Citation2016; Sensevy et al. Citation2013), aiming to co-design logical teaching sequences with certain variables monitored by researchers in order to measure their effects on student learning. Within this framework, the scientific investigation approach (Roy & Gremaud, Citation2017) and complex thought-modelling (Jenni, Varcher, and Hertig Citation2013) were two main inputs selected by the community.

In this context, pupils and teachers were invited to take chocolate as an object to investigate. With 10 kg of chocolate consumed annually per person in Switzerland, chocolateFootnote11 can be considered as a symbolic reference (Fumey Citation2019). Indeed, ‘(…) chocolate permeates every space and every object, every social group and every individual living in Switzerland. A passion that was brought to the rest of the world in the 20th century, when it became a transitional artefact of ‘Swissness’ (Santschi Citation1991 in Fumey 2019, p.99). An everyday object known to everyone was chosen because it allowed us to focus on how the status of this object can be changed in the classroom within the framework of the ‘didactics of constructing objects’ proposed by Bisault and Rebiffé (Citation2011). The authors stress the importance of ‘bridging two types of relatively blurred and mobile ‘boundaries’ (especially in pre-school): the boundary between the respective subject [discovery of the world] and other school disciplines, and the boundary between school and non-school’ (p. 14). What interests us here is the latter boundary as this is the process that will allow an item that is initially conceptualised as an everyday (non-school) item to become an object of investigation in school for both teachers and students. Thanks to the investigative work carried out by students, the status of chocolate as an object change from an everyday, non-school object to an object of interdisciplinary school investigation.

The underlying idea of the collaborative research is to create the right conditions to progressively build a ‘shared interpretative space’ (Bednarz Citation2015; Marlot, Toullec-Thery, and Daguzon Citation2017) around some of the didactic elements introduced by the researchers such as the scientific investigation approach and its problem-construction stage (Orange Citation2005; Roy & Gremaud, Citation2017: presentation of a framework of the investigative approach) and the modelling of complex thinking (Jenni, Varcher, and Hertig Citation2013).

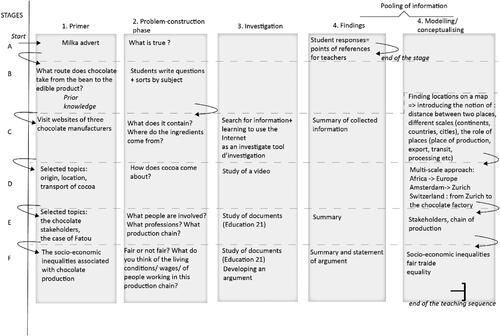

More specifically, the starting point is the definition of a teaching-learning problem (phase 1, ), which consists in bringing out the concerns of all the participants of the community with regard to a reflective ESD on the topic of chocolate. This sharing of concerns leads to a clarification and negotiation of training, research and development objectives between the members of the community. The desire to gradually introduce pupils to a culture of sustainability through an investigative approach that allows them to ask questions and construct answers or actions by mobilising ‘reasoned knowledge’ (Orange Citation2005) appeared to be an objective shared by all participants. In phase 2 () of the co-construction of a teaching-learning problem, these concerns are problematised and made intelligible by two didactic concepts introduced by the researchers: the interdisciplinary investigative approach and complex thought modelling. To give them more meaning, these didactic concepts are related to examples of classroom situations reported by the researchers and teachers. These concepts are used by the teachers as ‘thinking tools’ (Hertig Citation2016), or as a basis for designing their teaching sequences. In phase 3 (), teachers implement their teaching sequences. Finally, in phase 4 (), the teaching sequences are subject to a co-analysis within the framework of an explicitation interview (Martinez Citation1997; Vermersch Citation2019) and a cross self-confrontation interview (Clot et al. Citation2000; Faïta and Vieira Citation2003) based on these concepts. The researchers select relevant traces of the teachers’ and students’ activity and conduct a debate allowing a reflexive analysis of the practices.

Table 1. Stages of teacher training.

This process enables the community to bring the practical epistemologies of the different actors (teachers, researchers, and pedagogical advisors) involved closer together, thus giving pupils the means to grasp the complexity of the world. The integration of a discursive dimension into the community of practices is also important as it allows the progressive construction of this ‘shared interpretative space’ for teachers and researchers (Ligozat and Marlot Citation2016). In this way, the actors engage in a common undertaking, provide mutual assistance and pool their complementary skills, making it possible to build a repertoire of resources (experience, knowledge, material resources, etc.) which will enable them to achieve their objectives (Desgagné et al. Citation2001).

The teachers had very clear expectations regarding the creation and possible use of the teaching materials resulting from co-construction with the researchers. The latter wanted to contribute to continuing education in the field of science didactics and, more specifically, to problems-framing related to ESE from an interdisciplinary perspective through their analysis and the perspective of their work. The teachers constructed an interdisciplinary matrixFootnote12(Roy and Gremaud Citation2017) and developed a relevant problematic situation for the age and context of their class, which would allow them to engage the students in an issue/question (Roy & Gremaud, Citation2017; Orange Citation2005). Throughout implementation, the teachers designed teaching materials related to didactical concepts discussed in the training session within the DCIP in order to generate materials they could use with their students. While the topic of chocolate generated a lot of interest among pupils, it required a significant investment by the teachers, because few or no official educational resources were available. The teachers worked in teams. For cycle 1 (primary early school 1&2 + primary school Grade 1&2), they created teaching resources adapted to the profiles of the pupils in their class. For cycle 2 (primary school, Grade 3 to 6), as the teaching materials were compulsory, and because teachers invested a lot of time in appropriating disciplinary official resources, the work focused on adapting these official materials from an interdisciplinary perspective. In addition, we were given access to their planning documents (interdisciplinary matrix, personal planning), course documents and student documents (first- to eighth-grade levels; 1-8H). Ante and post focus group discussions were conducted with all the community, which were filmed and fully transcribed. These focus group discussions constituted a very rich resource for analysing changes in the teaching approach. We analysed the focus groups qualitatively following Baribeau (Citation2009).

The focus groups were analysed by means of a thematic analysis (Paillé and Mucchielli Citation2012), enabling us to compile synthesis tables including verbatim reports. In addition, expert discussions (same teachers divided into small groups per school cycle for more specificity) in the format of cross self-confrontation (Clot et al. Citation2000; Faïta and Vieira Citation2003) were conducted and analysed at the end of the training session to complement the focus groups. The purpose of the cross-confrontation is to get teachers talking about the concepts we want to study (ESD, problematisation, planification etc). The next section presents the main findings from our analysis.

2. Results

2.1. Findings from the analysis of the ante focus groups

The ante focus groups allowed the researchers to gain insights into the approach of the teachers with whom they would be collaborating. How do the teachers construct problems with their students? What does ESD mean for them? How have they considered ESD up to now? Have they previously implemented an investigative approach in class with students? The aim was to draw up a general profile of the teaching team’s needs in order to define the priorities and possibilities for cooperating and to identify the didactical concepts which could be studied/developed in the context of the DCIP. The results from the ante focus groups allowed us to identify a teaching approach which could be compared with the goal categories proposed by Roy et al. (ibid). In this section, we will present the initial approaches (reported practices) together with the difficulties, expectations of teachers regarding the project and the objectives to be achieved in the project (comments related to what the teachers think: ‘I would have liked to… I think it touches them… etc.’).

During the two ante focus groups, the primary school teachers talked about their work in relation to ESD ( and ). They presented their ‘usual practices’, the experiments carried out with the students, the methodologies they had developed, the results, and their reflections on their own practices (). Various difficulties were presented (). Fifteen teachers, from a same school, reported having already planned a teaching session in the context of ESD, most of them on the topic of waste management (8/15), food (analysis of a recipe and the distance travelled by the ingredients) (4/15) and energy (associated with Geography) (2/15).

Table 3. Synthesis of teachers’ responses regarding ESD and professional experience-related main issues (FG ante A and B, 2018).

Table 4. Synthesis of the responses to the question on the planning and experimentation of ESD session, focussing on the experiences and learning goals for pupils (Focus A and B, 2018).

In the first two focus groups (2018, A and B), we collected questions related to ESD and issues related to teachers’ practices when teaching cross-curricular themes of this kind. On the whole, the team’s responses to the questions asked (focus on didactic knowledge: objects taught and implemented [Gagnon and Dolz Citation2009]) revealed that a substantial number of elements relevant to the study were already present (). The ante focus groups allowed teachers to name (or not name) elements of knowledge that could be considered as ante-didactic knowledge. The teachers who answered questions about the teacher’s role (E1, 7, 8, 9, 10 in ) were not the same as those who highlighted the difficulties (E2, Ens7, E3, 6, 9). Those who spoke about the teacher’s role emphasised issues relating to citizenship and the individual’s power to shape the world and how it is understood. For instance, about the economic dimension of ESD and the study of the theme of consumption, E4 said, ‘Humans aren’t perfect… but maybe they’ll ask questions in the shop.’ E9 then added, ‘Even for us it’s not easy’. Those who voiced difficulties emphasized a strong need for support with implementing ESD and for help with finding relevant content for ESD (see E4 , Column 2, topic of energy, below). These teachers said they require methodological support from researchers.

Table 2. Synthesis of the methodology used for the analysis.

Furthermore, we observed that many teachers wished to place the pupils at the centre of a joint reflection. Most of them perceive ESD as a form of instruction that will enable pupils to question and reflect on issues beyond behaving in an environmentally friendly manner. Some of them described their difficulties with the practice. In the column 2, the practical problems listed are related to the pedagogy of the inquiry. It could be explained by the fact that for more than ten years, the Swiss curriculum (2008) and the official teaching materiel (2012) has prescribed this inquiry-based pedagogy. We should underline here the most important difficulty encountered by some teachers: they knew that they had to practice this kind of pedagogy (, Column 1 and 2) but they could only teach with a directive dimension (, Column 2).

Thus, in the examples given by many teachers, it is the directive dimension, centred on action, that seems to be prominent in their reported practices. For example, E2 explained that ‘my students and I picked up all [the waste] that remained in the yard for a week (…) having observed a rather impressive pile of waste, I did a learning sequence with my pupils, it triggered an activity in which the students and I asked questions. (…) Some [colleagues] simply made observations, others went a step further, in search of solutions and that was it’. Ens6 added that he/she ‘found the impact interesting (…) at the time it really affected them, and I don’t know, maybe we should have reactivated it (…)’. Furthermore, regarding awareness, E6 underlined that ‘when you see the waste that remains in the school yard (…), you say to yourself that the seed has not yet been properly sewn’. Others, such as E10, went a step further, explaining that ‘the theme is really important (…) because it is a social aspect that concerns us all, and awareness of it makes each person responsible, and I feel that this is something that we should give our students (…) it has to do with mutual respect (…) or simply respect for the environment (…). It touches on the notion of respect (…) between us or simply respect for the environment (…) I agree that we should not become moralistic at all, but that we should be able to raise awareness, to exhibit and encourage more open-mindedness (…)’.

The teachers’ reports highlight the fact that the planning of ESD is not organised in the same way as in other disciplines: ‘We don’t plan the task from the beginning through to assessment, like we used to (…) and I found that really interesting’. Ens7 pointed out that the pre-school students’ questions ‘don’t always come at the right time when you’re ready to do a learning sequence, I find it hard to exploit or find the right research question among all of the questions’. Although there was a lack of homogeneity among teachers with regard to their methodologies, they shared the need for support with the problem-construction and investigation phases and with guiding pupils ‘reflection (Gremaud, Letouzey-Pasquier and Roy, Citation2021, accepted). What is interesting for the researchers at this point in the study was that teachers needed a methodological framework to plan their activities (the interdisciplinary matrix) and a theoretical framework to better structure students’ knowledge and activity (complex thinking modelisation).

2.2. Analysis of the post focus groups and the expert discussion

We will now examine the data from the post focus groups (2019) and the expert discussion (2019).

We found that all teachers who completed the process made progress concerning problems related to planning and problem construction (, column 1). On the other hand, we observed that some teachers still had difficulties with selecting suitable starting points and some did not know whether they had carried out any ESD with their pupils (, column 2). The post focus groups, and the expert discussion therefore played an essential role. The opportunity to share their practices allowed teachers to compare views and to analyse problematic aspects together. The underlying purpose of the focus groups and expert discussions was not to provide insights into success stories, but more to bring problems encountered by teachers to the fore, which could then be addressed subsequently. For example, in this post analysis, the teachers had the opportunity to highlight the difficulties they encountered and to work on them again in a subsequent round of the DCIP. For example, E15 explained that ‘there are plenty of times when I have the impression that they more or less know something, but afterwards you really have to explain what the others did (…) [and] you really have to go back over it. For example, I thought that the video was going to be sufficiently clear (…)’. E16 added that ‘what is difficult with the little ones is that they lack a lot of language, understanding (…) two or three talk a lot (…) but the others wait for it to come…’. Commenting on the work carried out, Ens 7 explained, ‘What bothers me is actually sustainable development, I didn’t do anything about it. There’s nothing in the topic’ (FG 2019 A). This remark triggered a discussion on the definition of ESD among the teachers. In another way, the teachers were enthusiastic about the didactic approach proposed to them and reported progress on the aspects that posed problems for them – that is, problems regarding problem construction and planning – even if some of them still have progress to make. One difficulty teachers encountered, which was following a common thread in this type of sequence, was solved by the interdisciplinary matrix tool. Moreover, such an approach can also help change the way teachers perceive their pupils. For instance, E4 and E15 reported, ‘I was surprised by the amount of questions they asked’ and, thanks to the project format, ‘motivation is maintained, and I think that it is also because they have to ask questions, find answers, investigate, that’s what makes it interesting because they are involved’.

Table 5. Expert discussion and post focus group (2019): thematic analysis of responses to the question about the benefits and challenges from the teachers’ perspective.

2.3. Analysis of the change in the teachers’ approach based on modelling a learning sequence

In addition to analysing the content from the focus groups and as a more precise illustration of two teachers’ work, we modelled a teaching sequence implemented by teachers in a seventh and eighth graders classroomFootnote13 (11–12 years old). Based on the personal planification and the teachers’ reports (post focus groups and expert discussion), we analysed the sequence and mapped out the different stages worked on by the class within the framework of the investigative approach and presented to the teachers (cf. part 1, input). It is worth noting that the structure of the teaching sequence was strongly oriented towards the methodology presented to the teachers during training (, stages 2, 4 and 5). We can therefore conclude that, in this particular case, the teachers benefited significantly from training within the framework of the DCIP.

Figure 2. Modelling of a teaching sequence implemented in Grades 7 and 8 (7-8H) on the topic of chocolate. Design & realisation. Sources: focus group post A&B, 2019, teachers’ personal planification (2018).

We chose this sequence as it illustrates how two teachers jointly implemented a teaching sequence on the topic of chocolate within the framework of ESD, following the theoretical guidelines proposed by the researchers of the DCIP. The planning lessons stagesFootnote14 are labelled with letters (vertical dimension), and the phases of the investigation are numbered (horizontal dimension). A step can include between one and four phases of the investigation process. It can be seen that the investigative approach was repeated six times during the sequence. Although the first steps were descriptive, the problems became more complex from Step C onwards, as the teachers encouraged their pupils to reflect on ESD in an increasingly complex manner. The last column shows that the sequence included a wide range of explanatory factors related to the production of chocolate. E5 focused on implementing an abstract and analytical task with her pupils: modelling the supply chain for chocolate, constructing the problem with help and stimulus from the teacher (grouping the pupils’ questions by category and by subject), researching and analysing documents, organising and summarising the data as they were added to the panels. E5 explained that she encouraged her pupils to take a position regarding the documents about fair trade ‘to say whether they find it fair or unfair’ and specified that ‘it remains a choice, everyone is free to do what they want’ but that ‘if they want to be mindful of small producers, they know that they can buy fair trade’. E5 explained that she documented the topic as she went along so that the pupils could formulate arguments about it.

3. Discussion and conclusion: Review of the objectives and impact of the CDPI

In this section, we will discuss how the teachers’ approach has changed and show how their experience with the DCIP enabled them to adopt a reflective approach regarding their teaching practice. The main limit of this work concerns the interdisciplinary way that we wanted to implement. Indeed, the results indicate that the teachers tried to plan their lessons in an interdisciplinary way. However, we thought that their concrete work in the classroom was inscribed in a pluridisciplinary way because few links were clearly expressed to the pupils. Diemer and Marquat (Citation2016, p. 43) note that pluridisciplinarity is ‘the juxtaposition (at first sight complementary) of the works of several disciplines on the same subject but without effort of confrontation of the knowledge’. This is especially the case in the grades 7–8, where teachers chose to teach, one disciplinary field per class (maximum two) to answer to the chocolate problem(s). The main reason declared (cf. supra) was the timing. The analysis of the different focus groups with a diachronic approach enabled us to examine the progress of this ‘school team’ (Desgagné et al. Citation2001) and observe that the speed of progress varied between members of the team. In this context, the main benefit of the DCIP is to offer differentiated pathways (e.g. choice of disciplines, possibility of working on certain stages of the investigative process, the possibility for the co-construction of lessons, video recording or not) to teachers depending on their needs as part of an overall research-training project. ESD appears to be an area that needs further work from both an epistemological and practical point of view regarding implementation. The teachers had different approaches regarding knowledge and drew on their creative thinking skills to propose pathways to their pupils for, by example, modelling the chocolate supply chain (model with material in grade 1–2; systemic initiation in grades 7–8). Although the approaches implemented by teachers were imbued with the theoretical insights provided by the researcher-trainers, the teachers were given pedagogical (and didactic) freedom in how they worked with their pupils. In this respect, we believe that, at the end of this first complete phase of the DCIP, some of the training objectives were achieved. It should be emphasised that objects and concepts presented (matrix, modelling, problem construction) were considered by some teachers, as Marlot, Toullec-Thery, and Daguzon (Citation2017) write, «as a tool for grasping and organising usages and behaviours together [and separately] in order to make the activity more effective’ (p. 31). As researchers, we believe that the most important contribution has been the creation for all of interdisciplinary planifications related to a general problem associated to several sub-questions in relation to the chocolate theme. Teachers developed their ability to reflect on their practice connected to ESD. Researchers developed their skills linked with to collaborative research and a better understanding of the work and the needs of these teachers. This could help to prepare future training. We would add that the in-depth analysis of the recordings of two pre-school classes work revealed an appropriation of the modelling process by the teacher and their pupils (Gremaud, Letouzey-Pasquier, Roy et Mauron, in press). In addition, it is interesting to observe that the difficulties were not only related to planning and implementing classroom sessions, but that a problem of an epistemic (What is SD?) and an epistemological nature (What is ESD?) also emerged, prompting the researchers to question the ‘practical epistemology’ of the teachers (Amade-Escot Citation2019)Footnote15. Concerning this aspect, we could add that this observation has to be studied. Indeed, the researchers planned to work later on teachers’ understanding of ESD. This second phase of the community of practice was not conducted due to the coronavirus context. There was a focus group discussion before and during the training, but we can see that the problem is still present for some people at the end of the first round of the community. The limit of this Focus Group is that a real debate has not taken place. Teachers were reassured and there were no follow-ups about the ESD definitions. We can thus confirm that the DCIP played a role in establishing collaboration in relation to ESD by fostering ‘collaborative work between teachers in the spirit of a reflective community [with] (…) an impact on classroom practices (…)’ (Little, 1990 in Desgagné et al. Citation2001).

Notes

1 The theoretical-methodological foundations retained for the conceptualisation of this community are essentially based on the Discursive Community of Professional Practices (DCPP) theorised by Marlot and Roy (Citation2020).

2 The objective of ESD in the Swiss curriculum is to design lessons in such a way as to open students up to problems involving ‘actors and contexts, and which integrate environmental, social and economic aspects as well as spatial and temporal dimensions at the same level’(CIIP, 2003, p.23)

3 Approaching complexity in the context of education for sustainable development. Project leaders: Philippe Hertig (HEP Vaud) and Patrick Roy (HEP FR) https://www.hepfr.ch/recherche/projets-de-recherche-2

4 The number of teachers is high in this school since in most classes there are two half-time teachers.

5 Teachers’ training was including in the DCIP. Research and training worked together as a double process.

6 Teaching practice is understood here at the epistemological level (meanings that teachers attribute to ESD) and at the operational level (how ESD is implemented in the classroom). ESD in a reflective perspective is an integral part of the DCIP. Through its methodological operation, the DCIP proposes to link examples and classroom situations to build shared meanings on reflective ESD.

7 ‘Educations à…’ could be translate as ‘adjectival educations’. McKeown and Hopkins (Citation2005) explain that is ‘a term used (…) to describe those disciplines that need the word “education” attached to a term to assure their role roles in formal education’. This generic term refers for example to education for sustainable development, health education, environmental education, etc.

8 Here, we follow Bachelard (Citation2004) who says that ‘the scientific spirit forbids us to have an opinion on questions that we do not understand, on questions that we do not know how to formulate clearly. Above all, we must know how to pose problems’ (p. 16).

9 These school disciplines play a central role in understanding the world. Therefore, they are particularly relevant to the treatment of sustainability issues.

10 Inputs were mainly made on the characteristics of an interdisciplinary investigation approach in a reflective perspective, in particular on the conditions necessary to ensure an adequate articulation between problematisation (e.g. where can I buy this chocolate bar? Investigation by the students to find the same bar in Fribourg, investigation to the chocolate factory then questioning on the conditions of its manufacture and on its quality) and conceptualisation. The development of situational exercises was also discussed. We also shed light on the meaning of the concepts in the study plan.

11 The theme of chocolate was proposed by the researchers to the teaching team because of its emblematic character for Switzerland and its potential to address sustainability issues.

12 The interdisciplinary matrix provides an interdisciplinary representation of a situation or issue by highlighting the knowledge (concepts, methods, processes, etc.) of each contributing discipline.

13 Another article currently under publication addresses the modelisation of the project implemented in Cycle 1 with 5-to-7-year-old children.

14 In this context, a lesson is considered complete when the ‘end of the stage’ return arrow is shown.

15 The work of Wickman and Östman is cited in this article: ‘They focus on reporting on the choices made by participants and how these choices influence the direction of learning and, ultimately, what students learn.’

References

- Amade-Escot, C. 2019. “Epistémologies pratiques et action didactique conjointe du professeur et des élèves.” Education et didactique 13 (1): 109. https://www.cairn.info/journal-education-et-didactique-2019-1-page-109.htm.

- Audigier, F. Les Educations à…? Quel bazar! ! 2015. Conférence de plénière:. In J.-L. Lange (dir.). Actes du colloque: Les « Educations à »: Un (des) levier(s) de transformation du système éducatif? 8–24. ESPE de l’Académie de Rouen et Maison de l’Université. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01183403/.

- Bachelard, G. 2004. Le rationalisme appliqué. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Baribeau, C. 2009. “Analyse des données des entretiens de groupe.” Recherches qualitatives 28 (1): 133–148. http://www.recherche-qualitative.qc.ca/documents/files/revue/edition_reguliere/numero28(1)/numero_complet_28(1).pdf#page=136. doi:10.7202/1085324ar.

- Bednarz, N. 2015. “La recherche collaborative.” Carrefours de l’éducation 39: 171–184. doi:10.3917/cdle.039.0171.

- Bisault, J, and C. Rebiffé. 2011. “Découverte du monde et interactions langagières à l’école maternelle: construire ensemble un objet d’investigation scientifique. Carrefours de l’éducation.” Hors série 1 (3): 13–28. https://www.cairn.info/revue-carrefours-de-l-education-2011-3-page-13.htm.

- Clot, Y., D. Faïta, G. Fernandez, and L. Scheller. 2000. “Entretiens en autoconfrontation croisée: une méthode en clinique de l’activité, Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la santé [Online].” Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la santé 2 (1). doi:10.4000/pistes.3833.

- Conférence Intercantonale de l’Instruction Publique de la Suisse romande et du Tessin. 2003. Plan d’Etudes romand, Suisse. https://www.plandetudes.ch/

- Desgagné, S., N. Bednarz, P. Lebuis, L. Poirier, and C. Couture. 2001. “L’approche collaborative de recherche en éducation: un rapport nouveau à établir entre recherche et formation.” Revue des sciences de l’éducation 27 (1): 33–64. doi:10.7202/000305ar.

- Diemer, A, and C. Marquat. 2016. “Des « éducations à » à l’éducation au développement durable: un changement en profondeur de l’enseignement?.”. In Marin, B. & Berger, D. (dirs.). Recherches en éducation, recherches sur la professionnalisation: consensus et dissensus, 40–57. Le Printemps de la recherche en ESPE 2015. Paris: Réseau national des ESPE https://en.calameo.com/read/005079594f5f28d8defdf.

- Fabre, M. 2015. “Conférence de plénière: « Education à » et problématisation.” In J.-L. Lange (dir.). Actes du colloque: Les « Educations à »: Un (des) levier(s) de transformation du système éducatif?“.” (25–35). Rouen, France: ESPE de l’Académie de Rouen et Maison de l’Université.

- Fabre, M. 1999. Situations-problèmes et savoir scolaire. Paris, France: Education et formation, Presses universitaires de France. https://doi.org/10.3917/puf.fabre.1999.01.

- Faïta, D, and M. Vieira. 2003. “Réflexions méthodologiques sur l’autoconfrontation croisée.” DELTA 1 (19): 123–154. https://www.scielo.br/j/delta/a/dpx3ydxFrCRRwYJKTtcCZ7n/?lang = fr.

- Fumey, G. 2019. Le chocolat, une étrange passion suisse. Bulletin de l’Institut Pierre Renouvin, 2 (50), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.3917/bipr1.050.0087

- Gagnon, R, and J. Dolz. 2009. Savoirs dans la formation des enseignants de français langue première: Une étude de cas sur l’argumentation orale. In Hofstetter R. & Schneuwly, B. (dirs.) Savoirs en (trans)formation, pp. 221–244. Raisons éducatives, de Boeck Supérieur. https://www.unige.ch/fapse/publications-ssed/files/3615/6094/4557/RE13.pdf

- Gremaud, B., J. Letouzey Pasquier, P. Roy, and A. Mauron. (2021, accepted). “Le rôle de la modélisation pour appréhender le chocolat comme un objet d’investigation interdisciplinaire complexe: analyse de deux enseignantes.” Questions vives

- Hägglund, S, and I. Pramling-Samuelsson. 2009. “Early childwood education and learning for sustainable development and citizenship.” International Journal of Early Childhood 41 (2): 49–63. doi:10.1007/BF03168878.[Mismatch] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF03168878.

- Hertig, P. 2016. “Des outils de pensée pour appréhender la complexité dans le cadre de l’éducation en vue du développement durable.” In Ethier M.-A. & Mottet, E. (dir.), Didactiques de l’histoire, de la géographie et de la citoyenneté, 117–128. Louvain-la-Neuve: Belgique: Editions de Boeck supérieur.

- Jenni, P., P. Varcher, and P. Hertig. 2013. “Des élèves débattent: sont-ils en mesure de penser la complexité?” Penser l’éducation, Hors série 187–204.

- Joffredo Le Brun, S. Morellato, M. Sensevy, G, and Quilio, S. 2018. “Cooperative engineering as a joint action.” European Educational Research Journal 17 (1): 187–208. https://journals.sagepub.com/10.1177/1474904117690006.

- Lange, J.-M. 2014. “Education au développement durable: intérêts et limites d’un usage scolaire des investigations multiréférentielles d’enjeux, Education et socialisation.” [on line] 36 doi:10.4000/edso.959.

- Lange, J. M, and P. Victor. 2006. “Didactique curriculaire et «éducation à… la santé, l’environnement et au développement durable»: quelles questions, quels repères?” Didaskalia 28 (1): 85–100. doi:10.4267/2042/23954.[Mismatch] https://hal.umontpellier.fr/hal-01699624/document.

- Lebrun, J., P. Roy, F. Bousadra, and S. Franc. 2019. “Relations entre disciplines scolaires et «éducations à»: proposition d’un cadre d’analyse.” McGill Journal of Education 54 (3): 646–669. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/mje/1900-v1-n1-mje05322/1069774ar/abstract/.

- Ligozat, F, and C. Marlot. 2016. Un "espace interprétatif partagé" entre l’enseignant et le didacticien est-il possible? Étude de cas à propos du développement de séquences d’enseignement scientifique en France et à Genève. Raisons Éducatives, 20, 143–163. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12162/1563

- Marlot, C., M. Toullec-Thery, and M. Daguzon. 2017. “Processus de co-construction et rôle de l’objet biface en recherche collaborative.” Phronesis 6 (1–2): 21–34. doi:10.7202/1040215ar.

- Marlot, C, and P. Roy. 2020. “La Communauté Discursive de Pratiques: un dispositif de conception coopérative de ressources didactiques orienté par la recherche. Formation et Pratiques d’Enseignement en Questions.” Revue des HEP de Suisse romande et du Tessin 26: 163–184. http://revuedeshep.ch/pdf/26/26-09-Marlot-Roy.

- Martinez, C. 1997. “L’entretien d’explicitation comme instrument de recueil de données.” Association GREX

- Matagne, P. 2013. “Education à l’environnement, éducation au développement durable: la double rupture.” Education et socialisation 33 (1). [online] doi:10.4000/edso.94.

- McKeown, R. and C. Hopkins. 2005. “EE and ESD: Two Paradigms, One Crucial Goal.” Applied Environmental Education & Communication 4 (3): 221–224, doi:10.1080/15330150591004616.

- Orange, C. 1997. Problèmes et modélisation en biologie: quels apprentissages pour le lycée? Paris, France: Presses universitaires de France.

- Orange, C. 2005. “Problématisation. et conceptualisation en sciences et dans les apprentissages scientifiques.” Les Sciences de L’éducation-Pour L’ère Nouvelle 38 (3): 69–94. https://www.cairn.info/revue-les-sciences-de-l-education-pour-l-ere-nouvelle-2005-3-page-69.htm.

- ONU. 2002. Rapport du sommet mondial pour le développement durable. Johannesburg: Publication des Nations Unies. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/478154/files/A_CONF.199_20-FR.pdf

- UNESCO. 2014. Feuille de route pour la mise en oeuvre du programme d’action global pour l’éducation en vue du développement durable. France: UNESCO. https://www.unesco.ch/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Feuille-de-route.pdf.

- Roy, P, and B. Gremaud. 2017. “La matrice interdisciplinaire d’une question scientifique socialement vive comme outil d’analyse a priori dans le processus de problématisation.” Formation et pratiques d’enseignement en questions 22: 125–141. https://doc.rero.ch/record/289041.

- Paillé, P, and A. Mucchielli. 2012. L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales. Paris, France: Armand Colin. https://www.cairn.info/l-analyse-qualitative-en-sciences-humaines–9782200249045.htm.

- Santschi, C. 1991. La mémoire des Suisses. Histoire des fêtes nationales du xiiie au xxe siècle. Genève: Association de l’Encyclopédie de Genève.

- Sensevy, Gérard, Dominique Forest, Serge Quilio, and Grace Morales. 2013. “Cooperative Engineering as a Specific Design-Based Research.” ZDM 45 (7): 1031–1043. doi:10.1007/s11858-013-0532-4.

- Sgard, A, and H.-T. Janzi Berhnardt. 2013. Le « savoir des questions »: comment problématiser avec les élèves? Un exemple d’élément déclencheur: les éoliennes dans le paysage genevois. Penser l’éducation, 33, 205–221. https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=UUO_7n8AAAAJ&hl=fr

- Thémines, J.-F. 2012. “Ressources de problématisation en géographie scolaire française.” Nouveaux cahiers de la recherche en éducation 15 (1): 5–19. doi:10.7202/1013376ar.

- Vermersch, P. 2019. L’entretien d’explicitation. Paris, France: ESF Sciences humaines.