Abstract

Since the Community of Portuguese Speaking Nations (CPLP) was created in 1996, environmental education (EE) has gained recognition for enhancing multilateral cooperation on environmental protection and sustainability promotion. Conducted online in 2020 in all member states during the COVID-19 pandemic, this second Environmental Education Survey of CPLP explores the conditions and approaches of EE within the overall setting of the 2030 UN Agenda, taking the concepts of Canaparo’s geo-epistemology and Öhman and Östman’s selective traditions as the underlying framework of analysis. The survey received 196 valid responses from EE Experts and Promoters who hold positions in various institutional backgrounds. Addressing the current state of EE in all nine countries, a picture emerges of significant and ecologically prudent human intervention based on fact-based, normative, and pluralist EE approaches. Most encouraging is the overall finding that EE is vibrant, relevant for sustainable transformation, young people focussed, and in good heart.

1. Introduction: CPLP and the promotion of sustainability

The Community of Portuguese Speaking Nations (CPLP) is an international organisation founded in 1996. Its purpose is to enhance and coordinate cooperation between Lusophone (Portuguese speaking) countries in a post(de)colonial context, rooted and purposeful in their shared language: ‘a fundamental element of speculation [that cannot be seen as] a neutral tool, but as an invisible instrument’ (Canaparo Citation2015, 220) to interpret the world. Canaparo (Citation2015) stresses that a common language provides an important comparative dimension for assessing a culturally embracing concept and activity. Hence this is one of the underlying driving rationales of this survey.

On a constructivist approach, the Argentinian author suggested the concept of ‘geo-epistemology’ (2009, 2015) to understand and develop the peripheral spaces of Western culture: politically and economically peripheral territories, whose historical legacy, although fractious in specific domains, can lead to a common identity from colonial times to the present. Canaparo looks at knowledge/sought and territory/environment framing as part of the same social construct in analysing a historical relationship where language is the anchor. We cannot separate conceptual perspectives from local experiences and the cultural and physical environments within which they are thought. Therefore, geo-epistemology prioritises constructing a sense of locality that includes physical, non-material and imaginary places, among which language takes a central role (Canaparo Citation2009).

Based on such an idea, CPLP has always regarded environmental education (EE) as central to meeting its international development and collaboration goals yet limited to CPLP members. Its founding declaration highlights the enhancement of bilateral and multilateral cooperation for environmental protection and the promotion of sustainable development (CPLP Citation1996). In 2014, following the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UN DESD 2005–2015) and through promoting the CPLP Platform for Environmental Cooperation and the UN Millennium Goals, the constituent nations launched a Strategic Plan for Environmental Cooperation (PECA-CPLP), which recognised the central role of EE in promoting sustainability and a healthy environment for everyone.

However, important as it is, a common language is far from enough automatically to smooth socio-economic diversity in an imbalanced world. The PECA-CPLP proposal is thus designed to ‘stimulate environmental education actions adapted to the specificities of each member state’ (CPLP Citation2014, 7). Its purpose was to share common understanding across its member nations while taking their shared language and peripheral territories as an organising geo-epistemological condition.

A plural and locally based outlook from which EE promoters could achieve more local-tailored initiatives was thus the basic assumption of the second Environmental Education Survey in CPLP (EE2CPLP). This survey was designed and conducted by OBSERVA (Observatory of Environment, Territory and Society) and ASPEA (Portuguese Environmental Education Association). The goal was to explore a deeper understanding of the conditions and approaches of EE in the forthcoming context of the 2030 Agenda, taking the concepts of ‘geo-epistemology’ and ‘peripheral thinking’ (Canaparo Citation2009) and ‘selective traditions’ (Öhman and Östman Citation2019) as the underlying framework of analysis.

The EE2CPLP survey received 196 valid responses from EE experts and promoters in nine Portuguese-speaking countries. Respondents held positions in various institutional backgrounds (Governmental and Non-Governmental entities), roles within EE (Leadership, Training, Communication, Research), and geographic scope (ranging from local to international). This article considers its main findings, by addressing the current status of EE in CPLP Countries; assessing the repercussions of the pandemic on the SDGs and the EE responses; reviewing the prevalence of a mix of selective traditions in context; outlining the likely role of young people, and weighing up the support and impacts of an interventive EE on the overall transition to sustainability.

2. Data construction: a survey adapted to lock-down conditions

Particularly in settings where activists and practitioners may face different kinds of opposition (Abreu and Serrano Citation2010; Schmidt et al. Citation2011; Imaflora and ISA Citation2021; Guerra, Schmidt, and Prata Citation2022), the extensive geographical scope and the complex nature of EE within CPLP nations required considerable effort to collect reliable data. The COVID-19 pandemic context and the diversity of restrictive policies enacted in these nations severely limited the ability to reach respondents through traditional means. It required the exclusive use of an online survey and contacts through email addresses. The EE2CPLP survey ran over eight months (April to December 2020) and employed a ‘snowball’ strategy, inviting respondents to share the mix (open and closed questions) questionnaire with known EE stakeholders and promoters.

To kick things off, the research team mobilised the databases of the two partner entities (OBSERVA and ASPEA), particularly the Lusophone Network of Environmental Education (REDELUSO), which ASPEA coordinates. Hence, spread across all the Portuguese-speaking countries, REDELUSO and OBSERVA members served as spearheads dissemination of the questionnaire survey. With such support and based on many informal conversations with the two networks leaders, the questionnaire addressed the pursuit of EE activities in these new contextual conditions. It thus relied on more than thirty closed questions or sets of closed questions (i.e. Likert scales, multiple responses, dichotomies) and a similar number (twenty-five) of open questions that aimed to reach lesser-known features and patterns and decrease response dirigisme.

3. The final sample: comprehensiveness and scope for sharing

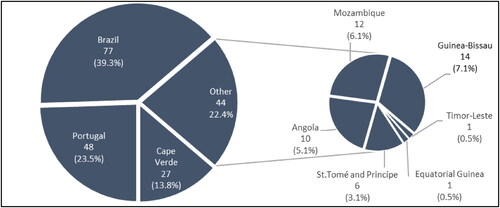

The resulting data can be seen as a portrait drawn from these EE experts and promoters’ practices and stances. Because of the necessarily constrained sampling strategy, the evidence is not statistically representative of the whole universe of EE stakeholders in the CPLP. Nevertheless, as shown in , three countries stand out with the most significant representation of respondents – Brazil, Portugal, and Cape Verde – with the last contradicting the trend of a lesser presence of the Portuguese Speaking African Nations. Indeed, this triad of nations stands out in various measures – e.g. higher scores within the Human Development Index (http://report.hdr.undp.org/) and Democracy Index (Economist Intelligence Unit Citation2022).

We recognise the limitations of predominantly online procedures – even boosted by phone calls and e-mails – as further expressing the invisibility of vulnerable communities and less web-connected EE practitioners. Moreover, given the low response rate (N = 1) from Equatorial Guinea and Timor-Leste, we do not include these respondents in the national-level analysis.

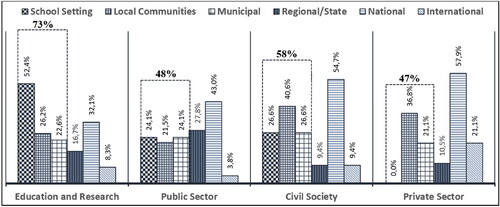

The EE2CPLP survey allowed respondents to select multiple options regarding their institutions, geographic contexts, and roles. In , institutional contexts were placed into four major groups to support a more straightforward interpretation.

Table 1. Diversity in selected institutions within the groups (multiple response group).

First, the prevalence of the public sector, research and education institutions is apparent. Moreover, although most respondents develop EE within only one type of institution (41.3% selected more than one), we note the diversity within the institutional groups. For example, most respondents in the Private Sector (84.2%) and Research and Education settings (69.4%) indicated that they are engaged in more than one institution in their EE work. On the other hand, Civil Society and those within the Public Sector were most likely to be dedicated to a single institutionFootnote1.

When breaking down these groupings at a national level, we found that local government representatives only appear in Brazil, Cape Verde, and Portugal. Such absence in other African nations may result from a perceived lack of institutional stability, decentralised policies, and regular local elections, which may reflect the mistrust and devaluation of municipal power already mentioned in other studies (Costa and Ferreira Citation2004; Abreu and Serrano Citation2010; Lusa Citation2018).

Nevertheless, as can be seen in , with or without municipalities, localised activities ensure a relevant global presence: education and research (73%), civil society (58%), public sector (48%), and private sector (47%).

Respondents working in the Private Sector and within Civic Society institutions are the most engaged in local communities yet also report activities at the national level. On the other hand, a minority of respondents who work in Educational and Research institutions or within the Public Sector (approximately one quarter) are active within local communities or municipal settings. This points toward a greater emphasis on EE within formal education, which happens in almost all countries. While valuing the relevant role of youth in the desired transition process, this bias tends to isolate school-age young people to the detriment of lifelong learning, weakens the promotion of sustainable community living, and prevents the understanding of sustainability as a holistic concept (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2021).

4. The current status of EE: attributed value and performance

The environmental movement emerged in the second half of the 20th Century with the growing political and civic recognition of the ecological crisis. Since then, the relationship between environmental and social quality became apparent in a dynamic where ‘the rise of the environmental movement walked hand in hand with other critical social movements’ (Rodrigues and Lowan-Trudeau Citation2021, 294). The idea of Sustainable Development also derives from the evidence of climate and environmental degradation. Still, deviant approaches emerged and persisted since the Brundtland Report (Redclift 1995), presenting its most forceful critiques and current socio-environmental emergencies (Schmidt and Guerra Citation2018). In short, capitalism became hegemonic in the 21st Century but was ‘haunted by an apocalyptic overtone’ (Latour Citation2017, 587). Hence sustainability was far from being overcome.

In this context, the idea of education for sustainable development (ESD) – launched in Johannesburg (UN Citation2002) and now integrated into the 2030 Agenda (SDG 6) – could raise eyebrows. But as Richard Kahn underlined, it could be strategically devoted to fostering a more radical eco-pedagogy if used under its holistic and systemic terms. ‘In this way, what has been heretofore known as EE could at least [under ESD label] move beyond its discursive marginality’ (Kahn Citation2008, 8).

Ever since the Tbilisi Declaration (1977), EE was expected to be ‘a learning process that increases people’s knowledge and awareness about the environment and its associated challenges’ (UNESCO and UNEP Citation1978). Later, by challenging established socio-economic order, it was asked to nourish a critical ecological awareness and to promote alternative lifestyles in which equity and justice emerge as inalienable principles of pedagogical work (Caride and Meira Citation2001).

Despite the oft-described policy gaps within EE and the 2030 Agenda (Bylund et al. Citation2021) it would be wise to harness the 2030 Agenda’s momentum and highlight the common ground between both proposals. Accordingly, the EE2CPLP Survey attempted to navigate the different EE tracks by assessing their attributed value and national performances.

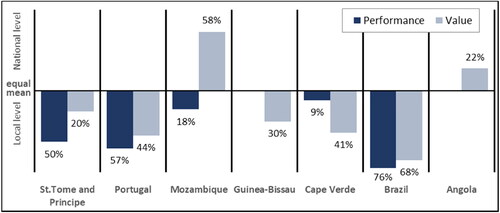

In , whilst Angolan and Mozambican experts considered that their national governments valued EE more than local governments, the general trend is to attribute better performances and assessments to local governments, especially among Portuguese and Brazilian respondents. This trend was already identified in the first survey (Schmidt, Guerra, and and Pinto Citation2017).

Moreover, the apparent opposition to Bolsonaro’s government – headed by a populist and denialist politician elected in Brazil in 2018 (Arruda et al. Citation2021) – can explain the more extreme results of Brazilian respondents, in line with other reported civil society complaints (Imaflora and ISA Citation2021). In sum, despite the autonomy afforded by the Brazilian constitution to states and local governments:

At the federal level, with the Bolsonaro government, there was the extinction of the Department of EE linked to the Ministry of Environment, which promoted a generalised demobilisation of EE, deregulating processes, programs and projects of the sustainability agenda, both at national, regional, and local level.

Respondent 122 - Brazilian Public Administration Official (EE2CPLP Citation2020)

5. COVID 19 repercussions on SDGs: an EE promoters’ perspective

The COVID-19 pandemic wrought extensive damage upon multiple sectors of society resulting in significant setbacks in the quality of life and environmental protection, i.e. in the 2030 Agenda (Shulla et al. Citation2021; Servant-Miklos Citation2022). These setbacks were felt worldwide, notably in the most economically fragile nations and communities, highlighting ‘justice as a fundamental concept to EE as they are environmental protection and conservation’ (Rodrigues and Lowan-Trudeau Citation2021, 294). After all, recovering from pandemic consequences, within or without the Sustainable Development framework, is crucial and consensual, and in the process, education undoubtedly plays a vital role.

In this light, we used the 2030 Agenda framework (the 17 SDGs) to ask about impacts and response needs, starting by analysing the perceived impacts of EE activities ().

Table 2. Assessment of SDGs where EE is most effective, by country.

For our respondents, EE has been most effective within Clean Water and Sanitation (SDG 6), chosen within the top 6 of all nations and in first place in Cape Verde (77.8%), Guinea-Bissau (64.3%) and Mozambique (66.7%). African countries were also united by the emancipatory impacts of EE on gender equality. This suggests that practitioners within these educational and environmental fields have spotted cultural practices within traditional local communities, supporting the greater autonomy of girls and women. For its part, Angola stands out as the nation where EE has had the most impact on social areas such as poverty, hunger, health, education, gender equality, and water and sanitation, which are deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, particularly among Angolan respondents, the EE and Agenda 2030 imperatives of justice seem to be part of respondents’ mindsets.

In turn, Brazilian respondents are the most diverse in their recognition of a pattern that reflects i) the diversity found within their regional and local contexts and ii) the variety of EE worked themes associated with a more established EE tradition (Schmidt, Guerra, and and Pinto Citation2017). Finally, in line with Portuguese respondents, Brazilian respondents stands out from other CPLP colleagues by observing the short-term impacts of EE on social problems.

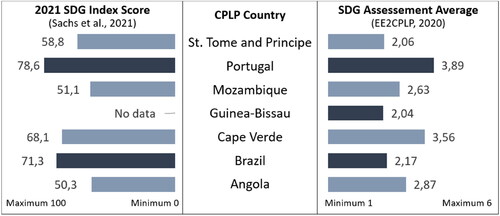

We then asked respondents to rate each SDG on a Likert scale of 6 (). By contrasting results with the SDG Index Score (Sachs et al. Citation2021), we found that they are congruent – except for Guinea-BissauFootnote2 and for Brazil, where the assessment of our respondents are considerably lower.

On the other hand, the only moderately optimistic respondents in their general assessment of the effectiveness of EE, are the Portuguese (3.89 out of 6) and Capeverdians (3.56). Brazilian respondents demonstrate a concern regarding their current hostile social and political climate, in a globally negative perception reflected in the Brazilian decline in the 2021 SDG Index (Sachs et al. Citation2021).

What is the prospect for further EE based action for a post-pandemic recovery? As shown in and compared to results, the scope widens, extending the need for action in most geographic contexts.

Table 3. SDGs where EE action is most necessary in a post-pandemic recovery.

For example, respondents from Angola and St. Tomé and Principe now consider extending a former restricted set of actions to other fields in the future. Within all CPLP countries, the strain of school closures has been acutely felt, so the Quality of Education (SDG 4) has risen to prominence. Regarding Clean Water and Sanitation (SDG 6), particularly in African countries, the signs of progress are tiny and of considerable global concern. Although Health and Well-Being (SDG 3) was considered an emphasised strength in Angola and Mozambique in the pre-covid period, it arises as a primary area which post-covid EE should address, once again in all nations except for Portugal.

6. EE in context: approaches and selective traditions

According to Öhman and Östman (Citation2019), different educational traditions cut across the various fields and contexts, determining themes and methods over what they call ‘Education for Sustainability and Environment (ESE)’. In such a view, a ‘selective tradition’ is primarily educational in context but can also be shaped by particular sociocultural considerations. Hence ESE can represent specific epistemological contexts stemming from their historical and social changes (Canaparo Citation2009). A process of local identity revelation, where sustainability would be perceived in the context of its history, its aspirations, its power relations, and its response to opportunities (O’Riordan and Church Citation2001).

Like most established practices, ‘selective traditions’ often function as a filter for what is and is not acceptable for a particular community. That is a kind of ‘imposed’ frame that may hinder or foster challenging ideas. Following such a view (), there are three types of selective traditions: fact-based, normative and pluralistic (Öhman and Östman Citation2019).

Table 4. Main assumptions of the three main selective traditions of ESE.

The strength of the fact-based tradition is its reliable and credible scientific anchoring. Sustained by it, students can better judge a tangle of information that is not always scientifically grounded in a so-called post-truth era. In turn, the weakness of this approach stems from offering an overly simplistic view, in which environmental and sustainability issues are presented as purely scientific and hence free of value and ideology. This situation can be worsened by: i) too little space for discussion and deliberation; ii) a lack of support for students to take their own stand on sustainability issues.

Yet, while not denying the relevance of scientific facts, the normative tradition primarily presents sustainability and environmental problems as a matter of attitude and of perspective. It thus encourages the adoption of specific views and the assumption of moral and cultural responsibilities. However, because of the inherent complexity of ecological degradation and sustainability, it becomes challenging to choose which values, norms and perspectives to promote without taking ‘the right values and norms’ for granted via an undemocratic process.

On the contrary, the pluralist tradition seeks to make students aware of different perspectives and interests. As a result, the students can reflect in a more anchored, lasting, and hopefully effective process, turning the classroom into a more democratic arena for negotiations, even if sometimes (as claimed by its detractors), being too relativistic and time-consuming process.

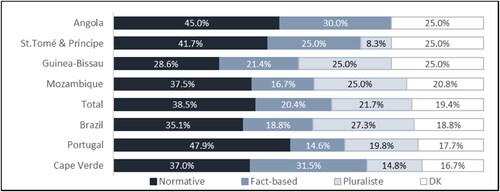

On the ground, however, and according to our results, EE practitioners tend to assume mixed attitudes that simultaneously include parts of all three selective traditions. The results expressed in should therefore be seen as one of the most commonly used approaches, which according to respondents, does not exclude other competing selective traditions.

With such a situation in mind, we note a lower confidence in the fact-based approach in Portugal, Mozambique and Brazil. In Cape Verde and Angola, this is the most valued approach. The normative tradition – which seems to be the most widely used selective tradition – is the predominant one, particularly in Portugal (47.9%), Angola (45%), and St. Tomé and Principe (41.7%).

Maybe because if taken seriously, ‘it is the more exigent in time and effort in a pandemic context’ (Respondent 12 – Portuguese NGO (EE2CPLP Citation2020), the pluralist approach is a presumed to be a minority choice in all national contexts. But in this particular case, Brazilian respondents take the lead with the higher percentage of responses (21.7%), in contrast to Angolan (0%) and St. Tomé and Principe (8.3%).

Finally, the ‘non-response’ rate – including those who do not recognise any significant EE activity – ranges from 25% to 16.7%, with an average of 19.4%. Once again, Brazil, Portugal and Cape Verde stand out with the lowest values, meaning that in these countries, the presence of environmental education activities is more present and perhaps more effective.

looks at the settings that actively develop and communicate knowledge (Media and Research Institutions) and act locally (Local Governments and Civic Society), which are most likely to support a pluralist approach, although normative approaches are also prevalent. On the other hand, the differences between Public Sector organisations are pretty visible, particularly when considering non-answers.

Table 5. EE selective tradition in your institution.

Therefore, although shaping different directions, the three traditions seems to coexist peacefully in all geographical contexts, and signs of cooperation between them clearly emerge. In an open world with multiple connections, tendencies and influences, it is not always possible to reject a true factual basis, urgent social change, or even pluralism of choice.

For example, 19% of respondents that work in government at a national level and 17% who work in Public Services preferred not to answer this question or indicated they didn’t know, whereas none of the local government officials opted for these choices. Although EE Centres are the only specialist educational facilities integrated within communities, most do not consider their primary goal to disseminate knowledge or develop participatory processes. They are more likely to inculcate environmentally friendly behaviours.

7. Participatory and interventive EE actions: support and impact

From Local Agenda 21 to Agenda 2030, the underpinnings of sustainable development are recognised as resting upon civic engagement and mobilisation. This also depends upon the perceived and real support (or backlash) offered by governmental and non-governmental institutions.

We analyse the assessment provided by the respondents of the institutional support, frequency, and impact of the ten EE actions shown in . In aggregate, most respondents (66.5%) identified the frequency of EE actions as ranging from occasional (22.7%) to every six months (25.8%). By reviewing the categories, we see that the EE Actions most frequently applied are the dissemination of information using online and traditional media, environmental investigative reports, and to a lesser extent, community outreach and environmental clean-up conservation actions.

Table 6. Perceived support provided by entities for EE actions.

In terms of the institutions that support these actions as presented in , we find a general trend favouring Non-Governmental Organisations by the respondents, with the notable exception of participation in school decision-making (27.1%). The only actions in which most respondents reported Government support (at the local or national level) were traditional media dissemination of EE, Education and Training and, to a lesser extent, Reporting and Investigations regarding the Environment.

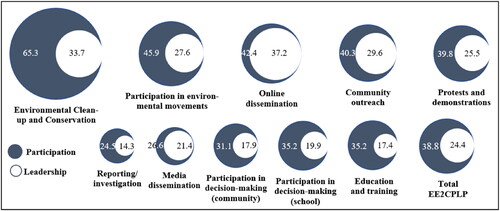

Given the centrality of children and youth in setting the goals of sustainable development and EE goals, it is essential to understand to what extent youth participation and leadership take place ().

About 39% of respondents reported active involvement of children and young people in overall EE actions, but only 24.4% reported leadership roles. Moreover, ‘Environmental Clean-up and Conservation’ stands out as the most youth mobilising activity, both as voluntary work (65.3%) and as leadership (33.7). On the other hand, we found ‘Reporting/Investigation’ activities as only 24.5% for simple participation and no more than 14.3% for leadership. But perhaps more important is the apparent diversity of actions involving children and young people, which does not permeate all activities in the same way. For example, when it comes to EE actions developed online (online dissemination), we find that 37.2% of responses refer to leadership, and only a few more (42.4%) refer to simple participation. On ‘Environmental Clean-up and Conservation’, ‘Education and Training’, and ‘Participation in Decision Making’ (both at school and community), a large part of activities remain outside the leadership of younger groups.

When looking into the perceived impact of these actions (), respondents attribute a modest yet positive evaluation (3.77 out of 6). Although respondents identify a strong adherence to leadership of children and youth in environmental mobilisation, these forms of intervention are evaluated as some of the environmental activities with the tiniest impacts (3.67 and 3.45, respectively). These are unexpected results, given the momentum of youth in environmental protests and mobilisation, which have received international political and political recognition (Riemer, Lynes, and Hickman Citation2014). Likewise, knowledge production regarding EE is the activity least reported and is rated as among the least effective.

Table .7 Perceived impact of some EE actions.

Although experts provide diverse perspectives, these contexts are highlighted by their societies’ demographic make-up. Such a situation was particularly pointed out by comments from Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, where most of the population is young. However, as a Cape Verdean expert pointed out, the education level in this micronation is markedly high, which, combined with increased access to technology, leads to ease in information dissemination. On the other hand, although respondents from Guinea-Bissau and Sao Tome and Principe affirmed a high level of engagement and leadership of youth in community action, the lack of IT resources limits their frequency and impact. Finally, whilst Angolan respondents opted not to provide further feedback, two of the three Mozambican experts considered that youth action was low-impact and mostly adult-led.

A Guinea-Bissau respondent indicated an essential consideration regarding EE and youth within these nations:

Frequency of actions is low due to lack of means, and as in African traditions, children and young people are less listened to in their communities and are considered as those who have no responsibility or skills to be able to speak out on important issues, so their impacts are always negative.

Respondent 82 – Guinea-Bissau NGO (EE2CPLP Citation2020)

Whilst most PALOP experts indicated that youth leadership was high in their countries, both Portuguese and Brazilian respondents described EE actions as being primarily adult driven, placed within a formal educational setting, and characterised as having a less proactive position in solving problems within local communities. Experts within these two countries differed regarding young people’s role in their communities. A Portuguese respondent considered that knowledge children acquire would be transmitted to their parents, leading to change within their communities, while Brazilian respondents were generally doubtful. A Brazilian researcher working in the Amazon went further:

I see in the children/young people a lethargy/doldrum/unbelief for the actions linked to voluntary actions (typical in Europe). Honestly, we have tried in many ways to involve children/young people, but the moment is of an indescribable ‘vacuum’.

Respondent 126 – Brazilian Researcher and Educator (EE2CPLP Citation2020).

8. Discussion and further research

In the complex world of today, and when we are just beginning to deal with post-pandemic consequences, it is essential to widen the perspective to the Web of interactions and feedback that could be de focus of Education for Sustainability and Environment (ESE) – the Leif Ostman and Johan Ohman proposal – and not only Environmental Education.

Environment and sustainability are indeed connected. The origin of the sustainable development idea clearly emerged from the first signals of the environmental disruptions in the seventeens of the 20th Century (Schmidt and Guerra Citation2018). Environmental education (whether or not assuming sustainable development) can thus benefit from the momentum offered by the 2030 Agenda to leverage its action. As underlined by Thomas Block and Eric Paredis, sustainability and sustainable development are, of course, also about ecological issues. But:

that’s only one part of the story. (…) The challenge lies essentially in how we can develop societies that provide a high quality of life in a way that is simultaneously ecological and just, not only locally or nationally but also globally (2021, 15).

Empirical analyses have demonstrated that democracies, particularly those that have developed social-liberal features to reduce poverty and inequality, outperform autocratic systems regarding environmental legislation and efforts, particularly in developing nations (O’Flaherty and Liddy Citation2018). Hence, given pressures from global and local imperatives, the localisation of sustainability (including its environmental dimension but not only) becomes even more challenging.

The confluence of objectives and activities of the various community actors (e.g. administration, NGOs, companies and schools) is thus central to any transition towards sustainability, simultaneously supported by networks of policy innovations and rigidities. In this view, there is no best practice or benchmark; there is only the memory of learning, the joy of change and the excitement of discovery (O’Riordan and Church Citation2001).

Yet, we sense that the degree of direct engagement with political processes and the exercise of power does not receive the full attention which is required if ESE is fully to be effective. This is a sensitive theme in many PALOP countries so we will await a future survey in more suitable conditions to assess this vital relationship further.

9. Conclusion

Faced with the onset of the environmental crisis within the CPLP, we conclude that the very different local communities surveyed found it troublesome to face the scenario of unsustainability within their policy delivery settings. Overall, we found local solutions and approaches are diverse and plural, based on a varied mix that depends on real and felt problems, which sometimes highlight dimensions of empowerment (critical thinking, leadership skills), sometimes relations with others (solidarity and belonging), and at other times of engaged consciousness (willingness to change, environmental awareness).

What seems to emerge in most of the CPLP countries (including Portugal and Brazil) experiencing the darkest pandemic periods, is a tendency for education to confront the environmental crisis without neglecting other relevant dimensions. In short, it is an SDG-driven process that put in its heart the motive ‘Leave no one behind’ as the central and transformative promise of the 2030 Agenda (UN General Assembly Citation2015). After all, the creation of new skills for a critical and ecologically prudent human intervention in nature incorporates fact-based, normative and pluralist approaches.

The most clearly disseminated selective tradition of EE among all CPLP countries is the normative one – the need to change values and behaviour remains urgent in these societies –followed by the pluralist tradition – the need for mobilising and proactive critical thinking grows. EE practitioners are mainly committed to social change, privileging ‘environmentally friendly’ attitudes and behaviours. But they do not undervalue empowerment and critical and transformative thinking, together with the promotion of citizen competencies and solutions through constructive processes of joint reflection and discussion. Accordingly, within CPLP countries’ EE experts and promoters, the fact-based selective tradition languishes as the least popular choice. EE practices no longer correspond to a simple fact-based activity, where environmental problems are approached by means of scientific knowledge (strong or weak). We regard this as a heartening form of maturity in the evolution of the EE/SD transition

The downside features identified from this survey include the lack of teaching materials and educational equipment, as well as insufficient training of technicians and teachers in the areas of environment and sustainability. In addition, there is a weak link with local universities. Most critically is the significant variability of meaningful political empathy, which has been weakened by the pandemic and the distractions of public health and economic survival.

Another outcome we cannot yet fully evaluate here is the effects of the pandemic on the pursuit of EE in PALOP countries. The impacts on economies and societies and public health safeguards are very many and very varied. What seems to come through from this survey is the vibrancy of a new sustainability-sensitive EE approach focusing on young people, their more viable futures, and the transformation of national and local politics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

João Guerra

João Guerra is a sociologist (Ph.D. in Social Sciences) and an Assistant Researcher at the Social Sciences Institute of the University of Lisbon (ICS-ULisboa). In this institution, he is responsible for the “Sustainability and Climate Change Sciences Seminar” at the Ph.D. Program on “Climate Change and Sustainable Development Policies.” In addition, he is currently a member of the OBSERVA - Observatory of Environment, Territory. Outside the ICS-Ulisboa,he is an elected member of the coordinating committee of the Portuguese Sociological Association Environment and Society Section.

Leonor Prata holds a Master in Sociology (MSc Sociology Research Track) from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). In addition, she is pursuing a Ph.D. degree in Sociology at the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon (ICS-ULisboa). Her doctoral research is in Environmental Education, specifically focused on the International FEE (Foundation for Environmental Education) Eco-Schools Programme in Portugal.

Luísa Schmidt is a sociologist and a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Social Sciences—University of Lisbon (ICS-ULisboa). At the ICS-ULisboa, she leads the OBSERVA—Observatory of Environment, Territory, and Society, and she is also part of the scientific committee of the interdisciplinary Ph.D. on Climate Change and Sustainable Development Policies. In addition, she is a member of the National Council for the Environment and Sustainable Development and the working group on the Sustainability of the EEAC (European Environment and Sustainable Development Advisory Councils).

Notes

1 To capture the diversity of institutional backgrounds, respondents were asked to select the institutions that applied, from a list of 10 options (as well as an open response), which were codified as: Research and Education – Educational Institution (N = 67), Research Centre (N = 43), EE Centre (N = 13) –; Public Sector – National Government (N = 26), Local Government (N = 20), Public Services and Public-Private Entities (N = 41 + 3) –; Civil Society – Non-Governmental Organization (N = 40), Association/Movement (N = 29) – Private Sector – Company/Consulting (N = 16), Media (N = 4).

2 Although the authors (Sachs et al., Citation2021) underlined the need for improved computing infrastructure and data collection is pervasive, Guinea-Bissau is among the worst ranked countries in terms of digital infrastructure, and therefore with no available data in the SDG Index.

References

- Abreu, C. & Serrano, C. (2010). Sobre Tolerância e Confiança em Angola [Tolerance and Trust in Angola]. 7.° Congresso Ibérico de Estudos Africanos. Lisbon, Centro de História da Universidade de Lisboa.

- Ardoin, N., Heimlich, J. (2021). Environmental learning in everyday life: foundations of meaning and a context for change. Environmental Education Research, 27 (12), 1681–1699. doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.1992354.

- Arruda, R., Meneses, T., Alves dos Santos, J., Paez, A., Lopes, F. (2021). The effect of politician denialist approach on COVID-19 cases and deaths. EconomiA, 22, 214–224, doi:10.1016/j.econ.2021.11.007.

- Block, T. & Paredis, E. 2021). Four misunderstandings about sustainability and transitions. In K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, & J. Öhman (Eds.), Sustainable development teaching: ethical and political challenges (pp. 15–27). London: Routledge.

- Bylund, L., Hellberg, S., Knutsson, B. (2021). We must urgently learn to live differently: the biopolitics of ESD for 2030. Environmental Education Research,1–16,2821 doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.200.

- Canaparo, C. (2009). Geo-Epistemology: Latin America and the Location of Knowledge, Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Canaparo, C. (2015). El colonialismo en segundo grado.Epistemología y pensamiento periférico. In Sanmartín, I., Gómez-Jordana, S. (Coord.) Temporalidad y contextos - La interdisciplinariedad a partir de la historia, el arte y la linguística, Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela - Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Cientíico

- Caride, J. A., Meira, P. A. (2001). Educación Ambiental y Desarrollo Humano. Bercelona: Editorial Ariel.

- Costa, M., & Ferreira, M. E. (2004). Geminações autárquicas e CPLP: Que articulação no apoio ao desenvolvimento económico local? [Municipal twinning and the CPLP: What articulation in supporting local economic development?] VIII Congresso Luso-Afro-Brasileiro de Ciências Sociais (pp. 1–22). Coimbra: CES - Universidade de Coimbra.

- CPLP. (1996). Declaração Constitutiva da Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa - CPLP [Constitutive Declaration of the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries]. Lisbon, Portugal.

- CPLP. (2014). Plano Estratégico de Cooperação em Ambiente da CPLP [CPLP Strategic Environmental Cooperation Plan].

- Economist Intelligence Unit (2022). Democracy Index 2021 - The China challenge. Retrieved from: https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2021/

- EE2CPLP (2020). II Inquérito sobre Educação Ambiental nos países da CPLP - Base de dados [II Survey on Environmental Education in CPLP countries - Database]. Lisbon: Observa (ICS-ULisboa).

- Guerra, J., Schmidt, L., & Prata, L. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals in Portuguese Speaking Countries: The perspective of Environmental Education Experts. Em W. V. (eds.) Leal Filho, Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research - World Sustainability Series. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32318-3_1.

- Kahn, R. (2008). From education for sustainable development to ecopedagogy: Sustaining capitalism or sustaining life?. Green Theory & Praxis: The Journal of Ecopedagogy, 4 (1), 1–14. doi:10.3903/gtp.2008.1.2

- Imaflora & ISA (2021). Mapeamento dos retrocessos de transparência e participação social na política ambiental brasileira (2019-2020) [Mapping transparency and social participation setbacks in Brazilian environmental policy]. Retrieved from: https://www.imaflora.org/public/media/biblioteca/mapeamento_dos_retrocessos_de_transparencia_e_participacao_social_na_politica_ambiental_.pdf

- Latour, B. (2017). Où atterrir? Comment s’orienter en politique. Paris: La Découverte.

- Lusa. (9 de september de 2018). Quintas eleições autárquicas de Moçambique preparadas em clima de mudança. RTP Notícias. Retrieved from https://www.rtp.pt/noticias/mundo/quintas-eleicoes-autarquicas-de-mocambique-preparadas-em-clima-de-mudanca_n1097856

- O’Flaherty, J. & Liddy, M. (2018) The impact of development education and education for sustainable development interventions: a synthesis of the research. Environmental Education Research, 24 (7), 1031–1049, doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1392484.

- Öhman, J., & Östman, L. (2019). Different teaching traditions in environmental and sustainability education. In K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, & J. Öhman (Eds.), Sustainable development teaching: ethical and political challenges (pp. 70–82). London: Routledge.

- O’Riordan, T. & Church, C. (2001). Synthesis and Context. In O’Riordan, T. (Ed.) Globalism, localism and identity: fresh perspectives on the transition to sustainability. (pp. 3-24). London: Earthscan.

- Redclift, M. (2005). Sustainable Development (1987–2005): An Oxymoron Comes of Age. Sustainable Development, 13, 212–227. doi:10.1002/sd.281.

- Riemer, M., Lynes, J. & Hickman, G. (2014) A model for developing and assessing youth-based environmental engagement programmes. Environmental Education Research, 20 (4), 552–574, doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.812721.

- Rodrigues, C. & Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2021). Global politics of the COVID-19 pandemic, and other current issues of environmental justice. The Journal of Environmental Education, 52 (5), 293–302, doi:10.1080/00958964.2021.1983504.

- Sachs, J., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., & Woelm, F. (2021). Sustainable Development Report 2021 - The Decade of Action for the Sustainable Development Goals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schmidt, L., Guerra, J. (2018). "Sustainability: dynamics, pitfalls and transitions". In Delicado, A., Domingos, N., & Sousa, L. (Eds.) Changing societies: legacies and challenges. The diverse worlds of sustainability, (pp. 27–53). Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais

- Schmidt, L., Guerra, J., & Pinto, J. R. (2017). Educação Ambiental no contexto da CPLP: Um Desaio Urgente [Environmental Education in the context of the CPLP: An Urgent Challenge]. ambientalMENTEsustentable - Revista científica galego-lusófona de educación ambiental, 1(23-24), 11–23. doi:1887–2417.

- Schmidt, L.; Nave, J. G.; O’Riordan, T.; Guerra, J. (2011). Trends and dilemmas facing environmental education in Portugal: From environmental problem assessment to citizenship involvement. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 13 (2): 159–177. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2011.576167.

- Servant-Miklos, V. (2022). Environmental education and socio-ecological resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from educational action research. Environmental Education Research, 28 (1), 18–39, doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.2022101.

- Shulla, K., Voigt, BF, Cibian, S., Scandone, G., Martinez, E., Nelkovski, F., Salehi, P. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Discover Sustainability, 2 (15), 1–19. doi:10.1007/s43621-021-00026-x.

- UN General Assembly (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

- UN. (2022). Report of the world summit on sustainable development. New York: United Nations Publications.

- UNESCO & UNEP. (1978). The Tbilisi declaration. Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education organised by Unesco in cooperation with UNEP, Tbilisi. http://www.gdrc.org/uem/ee/Tbilisi-Declaration.pdf