Abstract

This study engages with how sustainability stories can assign meaning to sustainability matter in different ways. The study contributes to discussions on how to combine facts, norms, and the democratic action competence in pluralistic approaches in Environmental and Sustainability Education. A special focus is put on how co-created sustainability stories can be used to provide, explore, and expand shared experiences of sustainability. The analysis engages with how content is defined and made relevant through stories, how they represent matter as pre-defined problems and solutions or as an invitation to exploration and reinterpretation, and how competences for sustainable development are made visible through the characters. The method used is a holistic narrative content analysis of 21 sustainability stories, co-created by pre-school teachers and their children. Three selected stories exemplify the results and show how some stories manage to move back and forth between on the one hand assembling sustainability matter as concrete problems to be solved, and on the other hand as open-ended issues promoting critical reflection. The main conclusion is that these, promising but yet uncommon, stories best represent pluralistic perspectives, creativity, and democratic action competence.

Introduction

In her article Storytelling in troubled times, Keri Facer (Citation2019) highlights the ability to articulate our hopes, fears, and desires through stories as a key to become active participants in the transformation towards a sustainable future. Stories are important, they are everywhere, they concern all aspects of our lives and are an integral part of all human practices. They are crucial in our relations and how we create meaning in and about the world (Bruner Citation1987; Polkinghorne Citation1988; Hart Citation2008). As such, stories are potent tools for communication that create space for certain goals, values, and actions while hiding others, or as Catherine Riessman (Citation2008, p. 8) puts it: “narratives do political work”. It is just as important to keep in mind that narratives and stories are not simply out there but “are actively and inventively crafted” (Gubrium and Holstein Citation2009, p. 30). These stories are not automatically innocent or good. Hence, it is important to explore how content is assembled into different kinds of sustainability in education, such as preschool.

Sustainable development challenges often include irreconcilable interests, uncertainty, goal conflicts, and situations where neither the problem nor the solution can be taken for granted (e.g. Block et al. Citation2019; Hulme Citation2010). Inspired by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber (1973), many scholars have described these challenges as ‘wicked problems’, meaning that problems that are difficult to define, lack clarity, and have solutions that cannot be defined as true or false. The political character of defining wicked problems draws attention to how and what sustainability matter is represented, on a scale from fragmented parts to an integrated whole (Uhrqvist et al. Citation2021). Hence, they represent pluralistic views whereby neither problems nor solutions can ever be fully resolved. Many scholars have emphasised the value and need for stories in the encounter with sustainability issues and as a tool in the transformation of the society (e.g. Facer Citation2019, Hensley Citation2020; Wibeck et al. Citation2019). In education research, this manifests in calls for pluralistic teaching (e.g. Caiman and Lundegård Citation2018; Sund and Öhman Citation2014; van Poeck et al. 2019) and creative problem-solving (Caiman et al. Citation2022; Cheng Citation2019; Garrison et al. Citation2015). To intertwine these two discussions, Uhrqvist et al (Citation2021) point to the use of Sustainability stories for critical and creative exploration of the interrelatedness of sustainability matter and articulation of inspiring pathways into the future.

Within the broader discussion about the role of stories in Environmental and sustainability education (ESE) this study focuses on how sustainability stories, co-created by teachers and pre-school children, assign meaning to sustainability matter in different ways. More precisely, we ask: a) What content is made relevant and what is the representation of causes to selected sustainability problems? b) How do the stories represent matter, as pre-defined problems and solutions or an invitation to exploration and reinterpretation? and c) How are competences for sustainable development made visible through the characters in the stories? All three questions address the importance to open up for different ways to relate to sustainability matter, both in understanding the matter and in exploring role-models for different ways to relate to complex phenomena. Thus, this study contributes to discussions about how stories and storytelling can strengthen ESE, enhance pluralism and creativity, and develop system perspectives and problem-solving.

Before moving on, we want to clarify our distinction between the concepts of stories and narratives, often used as synonyms. Inspired by the concepts Fabula and Sjuzet (see in Bruner, Citation1987), we use the concept story in line with Fabula to include attempts to narrate matter where there is a normative dimension creating meaning; in our case, assembling matter as a sustainability concern. The author makes a point. As such, stories can range from meta-narratives of the capitalist system, via nature documentaries, to fairy tales. Sustainability stories, more specifically, consist of matter assembled into believable wholes, including subjects that propel the course of events towards sustainability. Hence, documentaries and other fact-oriented accounts can also be seen as stories. Narrative is here used, like Sjuzet, as any sequenced account of events, where it is enough to share information.

Previous research

This previous research section outlines three scientific discussions relevant to our analysis of how sustainability can be assembled in different ways and its effect on how education engages with sustainability. Firstly, following our interest in sustainability education on a general level, we combine sources from different stages in the education system. One influential discussion in research on early childhood education for sustainability focuses on didactic methods, the how of education. This literature provides many insights about the value of practical engagement. In science education, creativity and explorative problem solving is seen as key to meaningful learning activities (Caiman and Lundegård Citation2014; Cheng Citation2019). Arts-based education bring in aesthetics, embodiment and emotions into the learning activities and shows its beneficial effects on learning and curiosity (Garrison et al. Citation2015; Karlsson Häikiö et al. Citation2020; Ward Citation2013). Specifying arts-based education, Furu et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate the value of multimodal storytelling as a creative way to include many voices in early childhood education. Taken together, this literature connects to the sustainability competences, e.g. action competence, anticipatory, and interpersonal competence and as outlined over the past decade (Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; Vare et al. Citation2022; Wiek et al. Citation2011). However, more knowledge seems to be needed on how to engage with more abstract competences such as systems and critical thinking with young children.

Parallel to the didactic how question, ECEfS can also be encountered based on the content selected as relevant, the what. From this angle, ESE seems to follow three selective traditions, fact-based, normative, and pluralistic (Sund and Gericke Citation2021). Many studies in Early childhood education show that although research for many years have shown that sustainability is often introduced in pre-schools as nature and taking care of nature, in many cases it is assumed that learning facts about nature will create environmentally friendly behaviour (Ärlemalm-Hagsér and Sundberg Citation2016; Hedefalk et al. Citation2015). Still many scholars have pointed to the need of critical reflections about the relationship between nature and the social (Hensley Citation2020; Facer Citation2019). A final condition for sustainability learning is pedagogues being engaged in the creative processes to facilitate and ask questions that inspire to new thoughts (Biesta Citation2022; Caiman et al. Citation2022).

At the intersection between studies of the creative, embodying, and explorative modes in education and the content selected, we find a gap in the knowledge about how matter can be represented when combining socio-ecological content with the form of co-crated storytelling that let the creation of a story invite children to explore sustainability. This study focuses on the possibilities to represent sustainability matter in different ways and how co-created stories can support more pluralistic education.

A second body of literature that also influences this study engages with new ways to make sustainability matter depart from the problem of pre-packaged representations of sustainability, simplifying real-world heterogeneity. Instead, this literature argues for the need of multiple perspectives and critical thinking (Furu et al. Citation2021; Jickling Citation1992; Kopnina and Cherniak Citation2016). Recently, van Poeck et al. (Citation2016, p. 806) pointed out Bruno Latours concept ‘matter of concern’ to be useful in engaging with controversy, as “an indispensable ingredient of environmental and sustainability education”. Their work is well in line with how Latour (Citation2004) introduced it as a contrast to ‘matter of fact’. The latter refers to a way of looking at reality based on what is taken for granted, indisputable, and unquestioned, while the former refers to the complex, controversial, and partly unknown.

Since it was introduced in Science and Technology Studies, matter of concern has been used to unravel matters of fact as unsettled and intrinsically interlinked with democratic processes, negotiating their role in society (Latour Citation2004; Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2011). Following this view, democracy is both a part of knowledge formation and a political process, within which the ability to engage requires a broad range of competences (Marres Citation2007). As van Poeck et al. (Citation2016) translate this into the ESE context, they point to a need to develop the capacity to act within unsettled knowledge conditions. However, they are not explicit in how this could be done in practice and thus this study explore how matters of fact and concern have been represented in stories co-created by children and their pre-school teachers.

Our third and final body of literature focus on stories. They have been presented as a creative and exploratory context where the challenges outlined above can interact and thus provide leverage for engaging with different ways of thinking, including self-reflection. On a broad social scale, stories have been identified as important for creating identity and meaning in general (Bruner Citation1987), in relation to the sustainability of the places we inhabit (Facer Citation2019; Hensley Citation2020), and for environmental knowledge (Furu et al. Citation2021; Lejano et al. Citation2013). As such, stories can be seen as an important leverage point in the anticipated sustainability transformation (Kall and Asplund, Citation2022; Rockström and Klum, Citation2015; Wibeck et al. Citation2019).

Education is one arena able to engage with stories in a way that helps active learners to explore how sustainability matter can be assembled with the support of teachers and each other (Uhrqvist et al. Citation2021). Pedagogical work with stories can also assist in the self-reflection that is sought in transformational learning because stories can make our assumptions visible (Kroth and Cranton Citation2014). Reason and Heinemeyer (Citation2016) argue that co-creation of stories enables learners to engage through what they call storyknowing, i.e. connecting the realism of a narrative with more intuitive kinds of knowledge based on long-term practical experience of authentic situations. Hence, creating stories that appear reasonable allows assumptions about relations and places to become visible and open for discussion. In the context of this study, stories are understood to open up matters of fact and matters of concern for critical reflection, and storyknowing can thus be a valuable tool in transformative learning processes. Nevertheless, the potential of using stories as a vehicle for problematising matters of concern is far from well-studied in ESE research, although its potential has been pointed out (Facer, Citation2019; Franck and Osbeck, Citation2018; Hensley Citation2020; Russell Citation2020; Uhrqvist et al. Citation2021).

Taken as a whole, previous research stresses the importance of agency in shaping both individual and shared knowledge in relation to different matters of concern. Furthermore, given the efforts of ESE to contribute to social transformation for a sustainable world, researchers such as Holfelder (Citation2019) argues that activities must dare to challenge the current unsustainable ways of knowing and being in the world. In turn, this actualises discussions about the inherent democratic paradox (van Poeck et al. Citation2016) as well as its political dimension (Håkansson et al. Citation2018). In the following, we use the term Sustainability stories to highlight the merge of content, integrating nature and the social as well as a plurality of voices within a story that align with anticipated sustainability transitions. Preferably, they are co-created in an explorative and creative way that includes the participants as agents of change.

Method

This article presents a holistic narrative content analysis of 21 sustainability stories, co-created by pre-school teachers and their child-groups. It is a part of a three-year research and workplace development project focusing on exploring and creating new narratives in education for sustainable development, engaging 100 preschool teachers in 21 working groups in Sweden. The stories studied here are the result of the final activity in the project, in which groups of teachers and children co-created sustainability stories during one spring semester.

The stories analysed have been created in different ways. Some are inspired by characters in existing stories, while others were created from scratch. The levels of co-creation differed from interaction around stories primarily created by the teachers to joint development in an exploratory process. All teachers were prepared by a basic introduction into ESE and how to create sustainability stories. The latter imply a story of how something becomes more sustainable based on a holistic approach. Preferably, the story includes agents that the children can identify with (Uhrqvist et al. Citation2021). The teachers also got short feedback on their approach halfway into the process. At the end, the teachers presented their stories to each other in smaller groups and then reflected upon the process. The researchers were not present in the preschools during the co-creation phase and the focus of the analysis is on the content of the final stories.

Our analytical approach builds on the perspective that we, as humans, are storytelling creatures, using stories to make sense of ourselves and the world (e.g. Bruner Citation1987; Hart Citation2008). Co-created stories can be assumed to reflect narratives that are meaningful and reasonable to the participants in their local context (Reason and Heinemeyer Citation2016). In our case, this means teachers’ and children’s knowledge, experience, and imaginations. Hence, the content of stories offers a window into the participants understanding of sustainability, reflecting what they find important and doable in their specific situation. For the teachers, this includes ideas about meaningful learning activities in the specific pre-schools.

A holistic content analysis of the narratives was used in this study, a method well known in studies of life histories (Beal Citation2013). Lieblich et al. (Citation1998) present this analytical approach in relation to categorical analysis that organises content in recurring categories in a text and between texts. In contrast, the holistic mode interprets different parts, what we call matter, in relation to the story as a meaningful whole. Thus, each story must be understood as an individual entity. In a second round of analysis, comparisons between stories are made to identify similarities and differences. In ESE research, similar narrative inquiry has been used to understand teachers’ professionalism (do Carmo Galiazzi et al. Citation2018). In our analysis, the primary empirical material, 21 sustainability stories, is triangulated with pedagogic documentation from the creation process as well as recorded teacher-intergroup reflections where the teachers presented and reflected upon their work. The pedagogic documentation and the teacher-intergroup reflections have supported our interpretation but are not be explicitly addressed in the results.

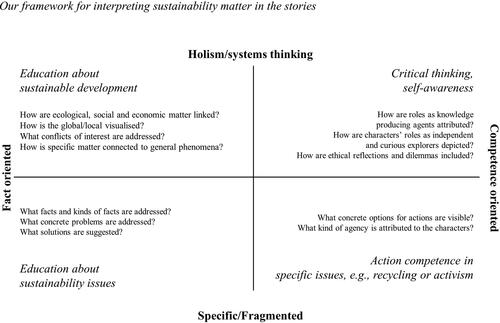

To guide our interpretations and visually (re)present how the stories unfold, but without narrowing down our scope to given categories, we have developed a four-fielder based on content to be expected given central themes within ESE research (see ). As such, the representation is based on two axes, resonating the guiding questions of this study. The first spans from fact-based to competence-based content. The second represents the scope of the content, from specific to holistic. This support for the interpretation provides a scale between extremes and not four discrete boxes. The framework also functions abductively to help us see what is not addressed in the stories.

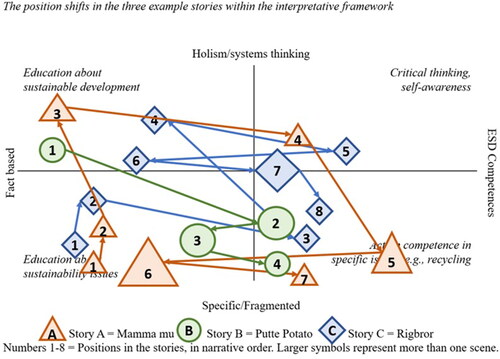

Importantly, stories are understood to be dynamic in the sense that they shift positions within the interpretative framework as they unfold. In the results part, three stories are used to exemplify the pattern in the empirical material and visualise how they move between different positions in the framework.

Considering the holistic mode of analysis with its focus on the relation between part and whole in each story, fragmented examples from the empirical material, therefore, bring little explanatory value. To provide a connection between empirical material and interpretations, positions in the stories will be referred to with a letter for each and the number for the position in the story, e.g. A5 for fifth position in the story Mamma Mu.

Many of the 21 stories interpreted circle closely around a narrow topic, such as a bird or a berry, and thus never manage to explore a deeper understanding of sustainability that includes human-nature relations, agents for change, and conflicts of interest. Thus, stories that focus on facts, such as the habits of an animal, remain within the lower left field in . Other stories in the empirical material focus on activities such as recycling or planting seeds. These stories tend to remain within the lower right field, occasionally bringing in facts and thus briefly venture into the lower left field. No stories move exclusively in the two upper fields. This could be expected since a story needs concrete content and action, especially considering the age of the children. In the results part, we present stories that provide elements from at least three fields. Following their shift in positions, the study provides a holistic and process-oriented interpretation of how matter is given meaning.

Results – three kinds of story

At a surface level, the stories studied in this article: a) are characterised by engagement with things that are familiar to the children; b) are typically materialised as different kinds of natural objects, e.g. spiders, blueberries or seeds, and litter; c) often deal with matter through the perspective of anthropomorphised animals and fictional characters; and d) relate to very concrete activities such as cleaning up litter, planting seeds and following their growth, playing with water, and in some cases exploring what things are made of. Considering the age of the children, this hands-on approach to sustainability matter comes as no surprise.

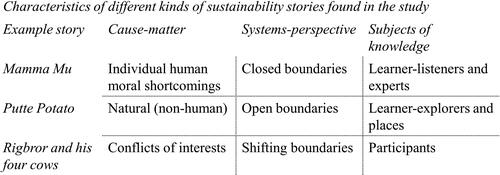

However, our main focus ventures beyond this surface level and into the deeper structure of the stories. We present three families of stories that emerged from the empirical material. These families relate to 1) causes and kinds of matter, 2) the kind of systems perspective employed, and 3) the subjects enacted in the knowledge production, experts and learners. gives an overview of our results. Three stories are used here to illustrate the general pattern in the 21 stories of the study. All three are well-known child stories in Sweden that the teachers and children have reformulated in the context of sustainable development.

Causes and kinds of matter

Firstly, and in line with previous studies (e.g. Öhman, 2008; van Poeck et al. Citation2016), the matter introduced in the stories tends to gravitate towards a focus on either facts or values. It is rare with pluralistic approaches, where conflicts between different values, views, and interests are made visible. The three stories used to exemplify patterns in the empirical material show different ways to relate causes and solutions. The sustainability matters enacted in the three stories are: litter in the forest (A1), water scarcity (B1), and deforestation (C1). Here we focus on how the matters are made fundamentally different through the narratives.

The first story, Mamma Mu, represents stories evolving around individual human shortcomings as the cause of the problem. In this particular case, a plastic bag has been left in the pasture, home to the anthropomorphised cow Mamma Mu (A1). This is presented as a problem that needs to be handled, and the plastic bag provides a starting point for an exploration of what happens to different types of objects, both human-made and natural. This story represents a common pattern where the cause of problem is human shortcomings. It turns into a moral lesson: respect the integrity of nature and animals and do not litter. This ethical imperative is supported by depoliticised neutral facts such as that plastic is made from oil, or that the waste can be sorted and left at the recycling station (A5).

The fact-based approach is further reflected as the story unfolds, from the starting point (A1), to the gathering of knowledge (A2), and the connection of questions and things (A3), to the inclusion of the children and their reflections (A4) to a focus on practice and actions competence (A5), to more exploration of sustainability issues (A6) and finally a conclusion in action competence and a way of tying the story together in (A7) with the following words from the main character: “Don’t litter in nature! Throw your plastic here! Your old ice cream jar can become a new toy! Thanks! From Mamma Mu”.

The second story, co-created with 2- to 3-year-olds, is about Putte Potatis (Little Potato) and represents how natural phenomena can be the cause of concern. Here children at a preschool receive a letter telling them about previous preschool children experiencing a lack of food (B1). The story mixes storytelling with practical experience as there is only one potato on each table when they sit down to eat lunch. As the story develops, the children realise that this will become a problem because there are no potatoes in the store due to the drought that is troubling the country. Here, the topic is not presented as a human (moral) shortcoming but as the effect of an unproblematised, naturally occurring extreme weather event implicitly combined with a particular human use of water (B2). The system shock caused by the drought highlights water as a vital resource for human well-being, encouraging the children and their teachers to explore where water comes from. As they do so, they encounter the technologies that bring water into the preschool, first as a small technical system inside the building and then in a wider circle, including a water-tower and underground pipes (B3). This experience of water use and transport is translated into practice as the children deal with the problem of bringing water to their own plants (B4). Here, causes emerge as a practical issue with no pre-given solution. Instead, the topic is made into a matter of concern for which the children search, trial, and assess different solutions.

The third story is the only one in the empirical material that is clearly developed around a conflict of interests. Here, Rigbror and his/her four cows are interested in grazing in a forest landscape threatened by Liselott, who is using her machines to chop timber for her paper mill. Starting from the perspective of Rigbror and the cows (C1, C2), the story broadens the scope to include an argument between different interests. The argument moves from an integrated problem description connecting consumption and production (C4) to a self-reflection on who the characters want to be (C5) to how this now deeper known problem can be handled in practise (C6). This ends in a compromise seeking to ensure that all characters get something, but also realising that Rigbror’s consumption (of paper) is dependent on the resource (C7, C8). Hence, the story exemplifies an approach to sustainability education topics that ties appreciated human behaviour to unwanted effects on the forest and the economic processes that make it possible. In addition, this conflict of interests is not only between people but also visible within the main character Rigbror, who both want to consume paper and save the forest.

The three stories demonstrate how differently sustainability matter can become parts of narratives depending on how causes and solutions are defined (). Most of the stories deal with human shortcomings, where both causes and solutions are clearly defined. For example, the story about Mamma Mu is about throwing away litter in a natural environment, and about finding the correct solutions and taking the morally right action. In contrast, Putte Potato exemplifies stories about natural causes and human ingenuity. This story also starts with a problem: there are not enough potatoes, but the focus is not on human shortcomings but on natural causes – in this case, a lack of water due to drought. Even though the story starts with a problem, the causes and solutions are not pre-given but open up space for a more exploratory approach. The third example demonstrates how it is possible to include conflicts of interest by creating twists in the story and not pitting good against evil, right against wrong, or villains against heroes. There is a solution in this story as well, even though it is achieved through compromises.

In contrast to these three characteristics of the matter dealt with in the pre-school stories, some potential is absent. First of all, no story starts in a neutral situation with the aim of improving a situation that is not clearly problematic at first glance. This could be, for example, increasing the biodiversity of a playground, which would probably lead to competing interests, but from a more positive angle. This relates to the second absence, which is enduring conflicts of legitimate interests. In all three stories, there is a correct solution to the problem, even though it sometimes requires a compromise.

Systems perspectives – broad to narrow, open to closed

The stories address a system perspective in different ways and, in relation to this, sustainability matter is of central importance. All stories in the empirical material begin on the fact-based side and usually in the specifics area of and present a concrete problem as a starting point. Close attention to the physical contexts within which the stories play out, the scenes, distil information about what the co-creators find it meaningful to include. Some stories move upwards into the fact-holistic area and thus increase the degree of complexity and pluralism (see ). Hence, more or less intentionally, scenes create a system boundary for the story.

At first glance, these scenes range from broad to narrow scopes in two different ways. Firstly, the spatial scales span from the very local of the playground to the national circulation of plastics, and sometimes even to imaginary lands where dragons roam. Secondly, scenes can also focus narrowly on a single phenomenon, such as spiders, or expand all the way to integrate all three sustainability dimensions, or a range of SDGs. This might be expected. However, in parallel to framing narrow and broad perspectives, the scenes also bear on a process perspective, as open or closed systems, depending on how teachers and children engage with the matter. As outlined below the stories about Mamma Mu, Putte Potatis, and Rigbror illustrate three different combinations of systems perspectives.

In the story about Mamma Mu, she finds plastic in the pasture (A1). The systems perspective primarily consists of the theme of plastic and follows it as a specific object – e.g. the children find out where the plastic comes from, how it is used, and how it can be recycled – a rudimentary lifecycle analysis (A3). The story also includes alternative trajectories, about degradation and why it is not good to leave plastic in natural environments (A3). By showing the relationship between how products made by humans risk affecting nature negatively, how plastic litter can be made into new products, and the ways in which, for example, worms, soil, and seeds, can be related to apples, relations and systems connections are made visible. While there is a system perspective, it has clear and stable boundaries. Consequently, all the questions asked in the story have answers waiting to be discovered, not constructed. Similarly, all the problems have solutions based on recycling technology and proper behaviour. Hence, the story moves into the specific-competence area (A5) when handling potential action. The system is closed, meaning that the matter considered relevant is decided beforehand.

In Putte Potatis, we see a different kind of systems perspective. The story illustrates an open-ended system with possibilities for exploration. Both the starting point and problem in the story are clear – there is a lack of the water needed to grow food, in this case potatoes (B1). The question asked is what the children in preschool should do now. This openness exemplifies what could be called an issue – even though scarcity is presented as a problem, it has not yet been assembled as a problem in a specific way. Here, solutions are not pre-given, which opens up opportunities for multidimensional perspectives by exploring human/nature interconnections through the lens of water scarcity (B2, B3, B4). Even though the story has a clear starting point in a defined problem, it opens out to encompass new questions, objects, and relations. In ESE, it is important to deal with the uncertain and the unknown, where understandings of phenomena can change and move. Putte Potatis takes a more open approach to the scene, in which co-creation explores different trajectories depending on how the discussions emerge in the process.

The analysis shows that most of the stories lack conflicts of interest. Or, in other words, the stories tend to be more about matter of fact and problems than matter of concern and issues. Hence, what is considered to be true and relevant knowledge is clearly defined, even though the story might, for example, be about children investigating a specific piece of matter, such as a plastic bag in a pasture. In the light of such defined problems and solutions, each action becomes either right or wrong, and thus heroes and villains are constructed. Even though facts have an important role to play, they are not enough in learning for sustainable development.

However, some of the stories exemplify the possibility of problematising conflicts of interest, as the story Rigbror. Like several other stories, it contains themes such as littering and the protection of nature. In the story, the four cows argue for the importance of preserving the forest, for the benefit of all. Then the story takes a turn as Liselott, with a smile on her face, drives into the forest on a machine to cut down the trees to make paper out of them (C5). This far into the story, there seems to be heroes who want to preserve the forest and a villain who wants to cut it down. However, it turns out not to be that simple. For example, the cows’ farts are problematised, while new trees can be planted to become carbon-dioxide sinks (C6). Furthermore, the paper mill can turn old cardboard into new paper. As the story unfolds, the increasingly complex depiction of competing interests complicates the roles of heroes and villains (C5, C6). This evolved view of interests highlights the characters’ agency and paves the way for a story about negotiation, which in this case ends in a win-win compromise (C7). In this story, neither the problem nor the solution is stable, which also leads to the system boundaries being more fluid. Hence, the felling of trees, the production of paper, and carbon-dioxide emissions, as well as plastics and the slaughter of cows due to a feed shortage, change meaning as the story twists and turns.

Subjects of knowledge/bearers of knowledge and learning

Characters in stories make actors tangible and thus provide examples of different ways to relate to sustainability matters, creating potential role-models for learners. By following how knowledge is produced, by whom, and how it is transferred, this section explores and analyses what kinds of knowledge the stories contain and enable. Leaving the focus on the three example stories, this part is organised to reflect the many different kinds of actors, i.e. experts, explorers, learners, and places, as well as the cross-cutting theme of anthropomorphised animals. In addition to the stories, this section also incorporates the results from the teachers’ group discussions.

Many of the stories present knowledge as something that both the children and teachers seek, explore, and discover. In many examples, teachers build upon their previous knowledge and provide room for the children to explore. However, as explained by one of the teachers, they did not always know the answers to the children’s questions, turning learning into a joint exploration. Putte Potato exemplifies this when a water tower outside the preschool becomes part of the story, presenting an opportunity to explore how it works, and how it connects a water source to the taps in the preschool (B2, B3). The children are able to follow their own line of thought and connect one phenomenon with another. Hence, both when teachers guide the learning exploration and sometimes also when it is a co-learning process, the children are able to engage as subjects whom we name learner-explorers.

In the exploratory stories, learning is primarily shaped through encounters with specific places and their inhabitants, which in turn become important carriers of knowledge. The learning subject becomes someone who is engaged with a specific environment. In the case of the water-transport system, exploration combined observation of the system with the construction of technologies for water transport at the preschool, with the aim of watering the children’s plants. Hence, the place becomes something to feel, taste, and interact with, something to influence and be influenced by. The place is also followed over time and returned to, which makes it possible to see and understand changes.

Moreover, places are not only physical spaces but also social ones, inhabited by others. Here, exploration can involve encounters with other inhabitants. These others could be insects in the preschool yard, wild animals in a protected natural area a short walk away, or sometimes even fictional characters, like trolls and dragons, which inhabit a place and whose activities are woven together with what happens there. Usually, these elements enable an encounter with non-human perspectives. In the stories, these characters contribute to the unpacking of matters of fact by bringing in other perspectives. By doing so, they also tend to present the problem as rooted in human ignorance and bad manners. Their expressed interests are never challenged and can thus be seen as an example of nature being the norm. Humans, positioned as external to nature, need to adapt, not compromise.

In contrast, the learner-explorer subject, the most common position into which the stories invite the children to become subjects, works through the relationship between curious learners and experts. As an example, the learners identify a question, ask the right expert, and then follow their advice. This sequence of tasks may be more or less challenging, false experts need to be exposed and dismissed, and sometimes many experts need to be consulted. Either way, experts are described as being either right or wrong, hence representing a fact-oriented kind of knowledge. The false expert is more of a comic figure for the children to react against, while multiple experts provide different but coherent pieces of unproblematic passive knowledge.

This kind of passive knowledge can be an issue in pluralistic learning, since it risks reducing the story to matter of fact, rather than envisioning alternatives. Asking an expert is a well-known way to get answers at preschool age. However, the expert knowledge encountered by the children always appears to be passive and neutral. Consequently, the children lose sight of the processes of knowledge production and learning, and especially the subjects involved in it. This could reduce the incentives for creative and critical thinking related to knowledge. No accounts were given of how the experts know, or the purposes for which the knowledge was assembled. Nor do such stories provide accounts from experts with different and competing interests. As a result, children encounter knowledge as a passive entity, something that is out there to be found, not created.

Animals are important in many of the stories, both as objects and subjects. They appear as objects to learn about, linked to questions such as: what do birds eat, do cows live in houses, or, at a more advanced level, how do worms benefit the soil? They are also linked to values, such as not trampling the animals, or destroying their habitats. The vast majority of the animals are also enacted as subjects in different ways. Animals possess expert knowledge about what it is like in nature and are thus a subject that the children can learn from and through. Sometimes, as in an example where the character Kråkan (the Crow) asks the children what happens to things thrown away in natural environments. Here the children are invited as co-creators of knowledge (A4, A5).

Especially when the stories engage with empathy, animals emerge as anthropomorphised, expressing humans’ thoughts and emotions. With few exceptions, they represent a naïvely harmonious view of nature, which is disturbed by humans, but where predators can be friends with their prey. The legitimacy of animals’ interests and behaviours is never questioned. When anthropomorphised animals participate in the stories, with their hybrid interests, this privileged position might distort the children’s learning about conflicts of interest.

Discussion – from problems to issues and back again

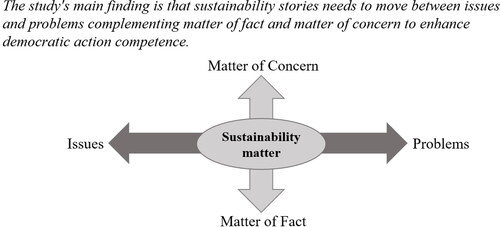

The result of our analysis contributes to scholarly discussions about how sustainability matter can be framed in ESE (Facer Citation2019; Hensley Citation2020; van Poeck et al. 2019) and the role of children as creators of knowledge and agents for change (Caiman and Lundegård Citation2014, Citation2018; Almers Citation2013). Especially, we focus on how matter comes to matter as facts and concern through sustainability stories (Furu et al. Citation2021; Lejano Citation2013; Uhrqvist et al. Citation2021). The main argument in the following discussion is that sustainability matter becomes more pluralistic in sustainability stories where a matter of concern is complemented with a narrative that moves between open ended issues and concrete problems.

As van Poeck et al. (Citation2016) convincingly argue, Latour’s (Citation2004) distinction between matter of fact and matter of concern is useful in the ESE context when engaging with the inherent democratic paradox (see also Block et al. Citation2019). However, translating these two concepts into an educational setting calls for attention to the different character of STS and ANT on one side and ESE on the other. While the first two primarily are interested in problematising black-boxed facts and knowledge production, ESE has a dual role in simultaneously training pluralistic critical thinking, engagement, and democratic action competence. As Almers (Citation2013) argues this requires a balanced combination of analytical distance and emotional engagement. Following Facer (Citation2019), we think that stories have a potential to combine these two.

In our holistic content analysis, pluralistic sustainability stories tended to move between positions in our interpretative framework (see ). The more frequently they moved between fields the more open-ended and explorative the story tended to be. These stories are not locked into being about facts alone, nor a critical reflection on them or calls to action. In these stories, the continuous movement between positions affects the depictions of the protagonists. They tend to become curious explorers of systems, which in turn visualise new ways to engage with unsettled issues, while simultaneously allowing the matter to be formulated as a distinct problem that can be acted upon, such as water scarcity. In the stories distinct problems are connected to emotional engagement and thus a call to action, as in the case with the Putte Potatis story where what could have been an abstract issue of drought was connected to a relatable problem at the preschool. The dynamic character of the pluralistic stories becomes clearer in contrast to narratives developed around static problem/solution assemblages. The latter tend to align with transmissive modes of education where relevant knowledge is to be given or found rather that created. As with dynamic stories this effects how protagonists are depicted, in this case as receivers of expert knowledge.

Narrative moves turning problems into issues connect to self-reflection, exploration of different views. On the contrary, as issues are turned into tangible problems, focus turns to practicalities, agency, and normative ethics (see ). Drawing on to Latour’s (Citation2004) original use of matter of concern, focused on unpacking undisputed facts, we suggest that in educational contexts this needs to be complemented the packaging of issues as problems for practical engagement. Our analysis suggests that stories that continuously moves between issues and problems support the balance between the analytical distance and practical engagement needed for democratic action competence, without reducing the complexity of sustainability matter into matters of fact (see Almers Citation2013; Hulme Citation2010; Rittel and Webber Citation1973).

Figure 4. The study’s main finding is that sustainability stories need to move between issues and problems complementing matter of fact and matter of concern to enhance democratic action competence.

Pluralistic action competence as narrated in the co-created sustainability stories acknowledges the need for the protagonists to engage with one or more problem/solution assemblages. Seen through Reason and Heinemeyer’s (Citation2016) concept of storyknowing, these tangible situations resonate with the lived experience of the co-creators of the story, enabling them to test the narrative against their own experience, explore creative solutions and thus build a shared knowledge. Hence, different kinds of stories invite different kinds of subjects to take place (see Biesta Citation2020). Stories that start with a clear, stable problem tend to engage the children as, what we call, learner-listener subjects, who learn through finding the right experts and listen to their message. For this kind of subject, the main challenge becomes visible as finding the right expert, which sometimes includes a reflection about if he/she can be trusted. In some stories, a series of experts are needed before the solution is reached. These stories follow a linear path where each expert adds to what the others have said, and there is no contradictory knowledge or implications, only an incomplete understanding.

Issue-oriented stories create space for subjects to take place as learner-explorers that engage with places (the scenes of the stories) through observation, experiments, and play. However, if no tangible problem/solution is included, the exploration has no direction and thus has difficulties connecting to action competence. These two subject positions exemplify different kinds of imaginaries and creativity, and hence the importance of reflecting upon how learners are positioned in stories. These results resemble Caiman and Lundegård (Citation2014) as they show the importance of allowing children to be in control of their learning process, where teachers adopt a listening approach allowing the children to stay in their experience. Our study contributes to this discussion as the co-created sustainability stories enable isolated matter to be embedded in a broader context, which can help teachers and children to engage and explore matter from positions and perspectives that are otherwise difficult to reach only based on children’s everyday experiences. As such, co-creation of stories allows teachers to combine a listening approach with Biesta’s (Citation2020) call to challenge children’s thinking, while remaining within but also to expand a shared experience.

Then what is the shared experience that is supposed to expand? Following the need to reframe sustainability matter and read the possible futures (Facer Citation2019) and landscapes (Hensley Citation2020) differently, we see that some of the stories in this analysis builds on exploration of the systems around sustainability matter, such as following the lifecycle of plastic like in the Mamma Mu story. However, our analysis point to two different ways to approach these systems. One is based on a closed system in the sense that relevant content and boundaries are fixed. On the other hand, open systems can be found in stories that explore and simultaneously redefine boundaries and sustainability matter. In the latter case, what seemed to be the initial problem changes through the story. As such, our analysis exemplifies the importance of combining different sustainability competences, among them systems, and anticipatory thinking as pointed out by Wiek et al. (Citation2011) and Vare et al. (Citation2022), in order to understand and redefine the frameworks used when engaging with sustainability.

The example of Rigbror shows how new knowledge can be created in the encounter between two characters with different but legitimate interests. One starting in an ecological and the other in an economic point of view. In the discussion they realise both perspectives need to be acknowledged, giving a new and more nuanced understanding of the initial problem, and hence a pluralistic perspective. The Rigbror example is the exception among the analysed stories that are otherwise build around right and wrong ways to handle the problems at hand. This could be seen to resonate how sustainability problems are discussed in general and, if so, maybe one of ESE most important contributions is to support more pluralistic understandings of problems and issues.

Conclusion and implications for ESE

Our holistic narrative analysis of 21 sustainability stories, co-created by pre-school children and their teachers, demonstrates that pluralistic stories continuously move between different position in a four-field interpretive framework structured around the axis of specific-holistic and facts-competences. These stories manage to include a broad understanding of sustainability that alternate between framing the matter as, what we call problems and issues. This pair of analytical concepts complement Latour’s (Citation2004) matters of fact and matters of concern translated from ANT/STS into pluralistic ESE by van Poeck et al (Citation2016). Adding issues and problems and especially the narrative moves between them, highlight the importance of problematising taken for granted frames of problem/solution assemblages as initially envisioned by Latour.

Considering the role of action competence in education and particularly in ESE, learning activities also has to include the construction of such assemblages, i.e. problems. Furthermore, our analysis suggests that stories that move multiple times between all four fields in the interpretive framework carry far more pluralistic accounts of sustainability matter. As a consequence and in contrast to what might be expected considering the well-established division between fact-based, normative, and pluralistic selective traditions (Sund and Gericke Citation2021), the contribution of our study is to point out the importance of stories that enable moves back and forth between the all three in different stages of the learning process. The fact-based and normative traditions are necessary to make problems tangible and emotionally engaging while the pluralistic tradition brings awareness of different but legitimate interests and how to deal with democratic negotiations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank The Swedish Research Council FORMAS (grant number 2018-00222) for supporting this work. We are also very grateful for the constructive and helpful comments we have received from the anonymous reviewers.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Almers, E. 2013. “Pathways to Action Competence for Sustainability: Six Themes.” The Journal of Environmental Education 44 (2): 116–127. doi:10.1080/00958964.2012.719939.

- Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E., and B. Sundberg. 2016. “Naturmöten och källsortering-En kvantitativ studie om lärande för hållbar utveckling i förskolan.” Nordic Studies in Science Education 12 (2): 140–156. doi:10.5617/nordina.1107.

- Beal, C. C. 2013. “Keeping the Story Together: A Holistic Approach to Narrative Analysis.” Journal of Research in Nursing 18 (8): 692–704. doi:10.1177/1744987113481781.

- Biesta, G. 2020. “Risking Ourselves in Education: Qualification, Socialization, and Subjectification Revisited.” Educational Theory 70 (1): 89–104. doi:10.1111/edth.12411.

- Biesta, G. 2022. World-Centred Education: A View for the Present. New York: Routledge.

- Block, T., K. van Poeck, and L. Östman. 2019. “Tackling Wicked Problems in Teaching and Learning. Sustainability Issues as Knowledge, Ethical and Political Challenges.” In Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges, edited by K. van Poeck, L. Östman, and J. Öhman, 28–39. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Bruner, J. S. 1987. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Caiman, C., M. Hedefalk, and C. Ottander. 2022. “Pre-School Teaching for Creative Processes in Education for Sustainable Development: Invisible Animal Traces, Purple Hands, and an Elk Container.” Environmental Education Research 28 (3): 457–475. doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.2012130.

- Caiman, C., and I. Lundegård. 2014. “Pre-School Children’s Agency in Learning for Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 20 (4): 437–459. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.936157.

- Caiman, C., and I. Lundegård. 2018. “Young Children’s Imagination in Science Education and Education for Sustainability.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 13 (3): 687–705. doi:10.1007/s11422-017-9811-7.

- Callon, M., P. Lascoumes, and Y. Barthe. 2011. Acting in an Uncertain World: An Essay on Technical Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cheng, V. M. Y. 2019. “Developing Individual Creativity for Environmental Sustainability: Using an Everyday Theme in Higher Education.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 33 (May): 100567. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2019.05.001.

- do Carmo Galiazzi, M., Paula D. Salomão de Freitas, C. Aguiar de Lima, C. da Silva Cousin, M. Langoni de Souza, and R. Launikas Cupelli. 2018. “Narratives of Learning Communities in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 24 (10): 1501–1513. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1545152.

- Facer, K. 2019. “Storytelling in Troubled Times: What Is the Role for Educators in the Deep Crises of the 21st Century?” Literacy 53 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/lit.12176.

- Franck, O., and C. Osbeck. 2018. “Challenging the Concept of Ethical Literacy within Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): Storytelling as a Method within Sustainability Didactics.” Education 46 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1080/03004279.2016.1201690.

- Furu, A. C., H. Kaihovirta, and S. Ekholm. 2021. “Promoting Sustainability through Multimodal Storytelling.” Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability 23 (2): 18–29. doi:10.2478/jtes-2021-0014.

- Garrison, J., L. Östman, and M. Håkansson. 2015. “The Creative Use of Companion Values in Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring the Educative Moment.” Environmental Education Research 21 (2): 183–204. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.936157.

- Gubrium, J. F., and J. A. Holstein. 2009. Analyzing Narrative Reality. London: Sage.

- Håkansson, M., L. Östman, and K. van Poeck. 2018. “The Political Tendency in Environmental and Sustainability Education.” European Educational Research Journal 17 (1): 91–111. doi:10.1177/1474904117695278.

- Hart, P. 2008. “What Comes before Participation? Searching for Meaning in Teachers’ Constructions of Participatory Learning in Environmental Education.” In Participation and Learning: Developing Perspectives on Education and the Environment, Health and Sustainability, edited by A. Reid, B. B. Jensen, J. Nikel, and V. Simovska, 197–211. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Hedefalk, M., J. Almqvist, and L. Östman. 2015. “Education for Sustainable Development in Early Childhood Education: A Review of the Research Literature.” Environmental Education Research 21 (7): 975–990. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.971716.

- Hensley, N. 2020. “Re-Storying the Landscape: The Humanities and Higher Education for Sustainable Development.” Högre Utbildning 10 (1): 25–42. doi:10.23865/hu.v10.1946.

- Holfelder, A. K. 2019. “Towards a Sustainable Future with Education?” Sustainability Science 14 (4): 943–952. doi:10.1007/s11625-019-00682-z.

- Hulme, M. 2010. “Problems with Making and Governing Global Kinds of Knowledge.” Global Environmental Change 20 (4): 558–564. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.005.

- Jickling, B. 1992. “Why I Don’t Want My Children to Be Educated for Sustainable Development.” The Journal of Environmental Education 23 (4): 5–8. doi:10.1080/00958964.1992.9942801.

- Kall, A.-S, and T. Asplund. 2022. “Let Many Stories Bloom: Scholarly Contributions on Narratives for Climate Transitions.” The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses 14 (1): 181–206. doi:10.18848/1835-7156/CGP/v14i01/181-206.

- Karlsson Häikiö, Tarja, Pernilla Mårtensson, and Liisa Lohilahti. 2020. “Aesthetic Practice as Part of Work with Sustainability, Participation and Learning Environments ñ Examples from a Finnish and Swedish Preschool.” Nordic Studies in Education 40 (4): 343–361. doi:10.23865/nse.v40.2601.

- Kopnina, H., and B. Cherniak. 2016. “Neoliberalism and Justice in Education for Sustainable Development: A Call for Inclusive Pluralism.” Environmental Education Research 22 (6): 827–841. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1149550.

- Kroth, M., and P. Cranton. 2014. Stories of Transformative Learning. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6209-791-9_2.

- Latour, B. 2004. “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 30 (2): 225–248. doi:10.1086/421123.

- Lejano, R. P., J. Tavares-Reager, and F. Berkes. 2013. “Climate and Narrative: Environmental Knowledge in Everyday Life.” Environmental Science & Policy 31: 61–70. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2013.02.009.

- Lieblich, A., R. Tuval-Mashiach, and T. Zilber. 1998. Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis, and Interpretation. Vol. 47. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Marres, N. 2007. “The Issues Deserve More Credit: Pragmatist Contributions to the Study of Public Involvement in Controversy.” Social Studies of Science 37 (5): 759–780. doi:10.1177/0306312706077367.

- Mogensen, F., and K. Schnack. 2010. “The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/13504620903504032.

- Öhman, J. 2008. “Environmental Ethics and Democratic Responsibility: A Pluralistic Approach to ESD.” In Values and Democracy in Education for Sustainable Development: Contributions from Swedish Research, edited by J. Öhman, 17–32. Malmö: Liber.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. 1988. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Reason, M., and C. Heinemeyer. 2016. “Storytelling, Story-Retelling, Storyknowing: Towards a Participatory Practice of Storytelling.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 21 (4): 558–573. doi:10.1080/13569783.2016.1220247.

- Riessman, C. K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. London: Sage.

- Rittel, H. W., and M. M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4 (2): 155–169. doi:10.1007/BF01405730.

- Rockström, J., and M. Klum. 2015. Big World, Small Planet: Abundance within Planetary Boundaries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Russell, J. 2020. “Telling Better Stories: Toward Critical, Place-Based, and Multispecies Narrative Pedagogies in Hunting and Fishing Cultures.” The Journal of Environmental Education 51 (3): 232–245. doi:10.1080/00958964.2019.1641064.

- Sund, P. J., and N. Gericke. 2021. “More Than Two Decades of Research on Selective Traditions in Environmental and Sustainability Education: Seven Functions of the Concept.” Sustainability 13 (12): 6524. doi:10.3390/su13126524.

- Sund, L., and J. Öhman. 2014. “On the Need to Repoliticise Environmental and Sustainability Education: Rethinking the Postpolitical Consensus.” Environmental Education Research 20 (5): 639–659. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.833585.

- Uhrqvist, O., L. Carlsson, A.-S. Kall, and T. Asplund. 2021. “Sustainability Stories to Encounter Competences for Sustainability.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 15 (1): 146–160. doi:10.1177/09734082211005041.

- van Poeck, K., G. Goeminne, and J. Vandenabeele. 2016. “Revisiting the Democratic Paradox of Environmental and Sustainability Education: Sustainability Issues as Matters of Concern.” Environmental Education Research 22 (6): 806–826. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.966659.

- van Poeck, K., L. Östman, and J. Öhman, eds. 2019. Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Vare, P., N. E. Lausselet, and M. E. Rieckmann, eds. 2022. Competences in Education for Sustainable Development. Cham: Springer.

- Ward, K. S. 2013. “Creative Arts-Based Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability (EfS): Challenges and Possibilities.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 29 (2): 165–181. doi:10.1017/aee.2014.4.

- Wibeck, V., B. O. Linnér, M. Alves, T. Asplund, A. Bohman, M. T. Boykoff, P. M. Feetham, et al. 2019. “Stories of Transformation: A Cross-Country Focus Group Study on Sustainable Development and Societal Change.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 11 (8): 2427. doi:10.3390/su11082427.

- Wiek, A., L. Withycombe, and C. L. Redman. 2011. “Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development.” Sustainability Science 6 (2): 203–218. doi:10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6.