ABSTRACT

In the integration literature, the relationship of the European Union (EU) as a donor and the (potential) candidates for EU membership as recipients of democracy promotion is described as asymmetrical. The donor is portrayed to have full whereas recipients have moderate or even no leverage over democratic reform what brings a hierarchical notion of active donors versus passive recipients into the analysis. Taking the local turn into consideration, however, this contribution argues that democracy promotion, is better conceptualized as a dynamic interplay between external and domestic actors. It reveals the toolbox of instruments that both sides dispose of, traces the dynamic use of these instruments, and systematizes the structural and behavioural factors that constrain the negotiation interplay. A case study of negotiations over public administration reform in Croatia in the context of EU enlargement shows that domestic actors dispose of leverage that counterweights external leverage and mitigates the implied hierarchy.

Introduction

In the integration literature on the European Union’s (EU) enlargement process, scholars have conceptualized democracy promotion as an asymmetric relationship between ‘donors’ and ‘recipients’ of democracy promotion where the external donor has democratizing leverage over the domestic recipient. While the EU sets the accession conditions, the role of the (potential) candidate country is to fulfil them, and get in return rewarded, with financial aid, policy concessions (e.g. visa liberalization), and finally with membership.Footnote1

In this understanding, external actors would sit in the driver’s seat setting the reform agenda while domestic actors would have to comply with external reform demands with little power to alter them. Domestic adoption costs would further limit the domestic side’s willingness and capacity to actively manage the reform process.Footnote2 External reform demands are fulfilled due to the leverage of the EU over the (potential) accession candidate, or in other words, the candidate’s vulnerability to external pressure that is due to the attractive EU membership.Footnote3 The higher the leverage of the external actor, here the EU, the more likely is the adoption and implementation of democratic reform in the recipient country, here in the (potential) accession candidate.Footnote4

As the integration literature shows, on a regular basis EU reform demands are not fulfilled while the government of the (potential) candidate country has demanded for membership and thereby accepted the conditions under which accession takes place in the first place. At times, the EU even accepts to drop reform demands or to adapt them to local purposes to the extent that the original objective of the reform is not longer achieved. To explain this puzzling behaviour, it is necessary to bring in an interactive notion into the analysis of democracy promotion negotiations and take both sides’ leverage over the course of the negotiations into account. Both the external and the domestic side disposes of leverage making the respective negotiation counterpart to change its agenda, its preferences and its expectations about what kind of reform to achieve and how to achieve it. Domestic actors not only dispose of the capacity to take over or reject external reform demands, but also to actively modify and change them.

It is argued here that the relationship between donor and recipient should be conceived as a dynamic interaction between donors and receivers of democracy promotion where the formulation of specific policies (reform content), the distribution of material resources (reform scope), and the process of drafting, adopting and implementing agreements and programmes (reform procedure and pace) are negotiated.Footnote5

In the enlargement negotiations between EU officials and the governments and line ministries of the (potential) candidate countries, both sides introduce ideas about democratic norms and institutions, reform procedures and expected outcomes intended to adapt the (potential) candidate’s political system to EU requirements. Content, scope, procedure and pace of reforms can become subjects to be negotiated between external and domestic actors involved.Footnote6 During this process, both sides dispose of leverage making the negotiation counterpart to change its agenda, preferences and expectations about what kind of reform to achieve and how to achieve it.

The interactive model opens up the black box of democracy promotion negotiations and allows for a more fine-grained analysis of the dynamics of the negotiation process that leads to an in-depth explanation as of why some reforms in democracy promotion are accepted while others are modified or rejected. It achieves these aims due to two innovations: First, it complements the well-described set of external instruments with a set of domestic instruments. Domestic actors make use of these instruments to accept, to modify or to reject reform proposals. Modification or rejection might distort a specific reform, but not the overall democracy promotion relationship. Second, it systematically takes external and domestic constraints (e.g. structural conditions and other relevant actors) into account while avoiding a too simplified notion of unwillingness or lack of capacity on the domestic side.

The remainder begins with critically discussing the integration model and identifies the shortcomings of a hierarchical notion of external leverage. As an alternative, then, it conceptualizes an interactive model of the external-domestic interplay in democracy promotion and discovers the instruments that are used by both sides in enlargement negotiations. It continues to systematize the structural and behavioural factors that constrain the negotiation process. On the external side, conflicting objectives, hidden agendas, and limited mission capacity are among those factors that limit external leverage. On the domestic side, it is the need of governments to respect organized interests of coalition partners, political parties in the opposition, trade unions or other domestic veto-players when drafting, adopting and implementing democratic reforms. A case study on Croatia’s public administration reform traces the dynamics of the external-domestic interplay, the use of external and domestic instruments that shape the reform process and analyses the influence of constraining factors. A final section concludes.

The integration model: external leverage, hierarchy, and domestic resistance

Different strands of the literature tend to focus on the external actors’ side when analysing democracy promotion, ascribing domestic actors either a passive or a reluctant role in their interaction with external actors. The EU integration literature presents the EU as the driver of democratization through approximation and integration of (potential) candidates for membership. To name two prominent attempts, Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier’s focus on the EU’s capacity to further democratization through three models of integration, the external incentives model, the social learning model, and the lesson-drawing model.Footnote7 The application of these models suggests that domestic actors either accept EU demands and democratize, or reject them and, as a consequence, get stuck somewhere in the transition process. Börzel and Risse’s four modes of external democratization, coercion, conditionality, persuasion, and socialization, operate on the assumption that domestic actors sooner or later learn from external, meaning ‘Western’ concepts of democracy and adapt to the external democratization agenda.Footnote8

In the transition literature, Levitzky and Way offer the most cited attempt to theorize external influences in democratization.Footnote9 In their perspective, ‘external leverage’ (the degree to which governments are vulnerable to external democratizing pressure) and ‘linkage to the West’ (economic, political, diplomatic, social, and organizational ties and cross-border flows of trade and investment, people, and communication between particular countries and the United States, the EU, and western-led multilateral institutions) best explain the variance of democratization in countries that are exposed to Western pro-democratic influences to different extents.Footnote10 In that line, Levitzky and Way would explain democracy promotion failures partly by deficits that are inherent to the democracy promotion agenda and the strategies that pro-democracy Western actors use to promote democracy, resulting in low and inconsistent democratization pressure. When it comes to the domestic side, like the EU integration literature, Levitzky and Way tend to reduce the domestic agency in the democracy promotion relationship between external and domestic actors to ‘compliance,’ ‘partial compliance,’ or ‘non-compliance.’ Thereby, an asymmetric relationship between external actors as the active ‘givers,’ and domestic actors as the passive “receivers” of democracy promotion, is established.Footnote11

IR literature on the promotion and diffusion of international norms suggests looking more closely at the processes of norm contestation and localizationFootnote12 and taking the economic, political and social situation of democratizing, post-conflict and fragile states as recipients of democracy promotion into account.Footnote13 Domestic context conditions and especially the embedded domestic third parties influencing the preferences of domestic actors function as constraining factors for domestic negotiators. In the same vein, the literature on the post-liberal peace takes a local turn in hinting to the importance of local ownership in state- and peace-building processes. Scholars such as Mac Ginty or Richmond (with various co-authors) discuss in detail the reasons for local ‘resistance’ to external reform demands.Footnote14 In this strand, domestic actors are not portrayed as passive, but instead as foremost ‘resistant’ to external reform demands. Hardly if ever it is considered an option in this literature, that domestic actors accept external reform ideas. The process of acceptance, modification or resistance is not specifically described.

To sum the major shortcoming of the above-cited literature strands up, domestic actors are hardly if ever described as independent rational actors that dispose of distinct and powerful instruments that could serve to influence the process of negotiations, shape the reform agenda, and alter the outputs. Instead, scholars and practitioners perceive external actors to sit in the driver’s seat of reform and tend to portray domestic actors foremost as ‘unwilling’ (interpreted by external actors as being ‘illiberal,’ ‘anti-democratic’ or ‘anti-modern’)Footnote15 or ‘unable’ (understood as being not capable due to resource constraints or a lack of personal knowledge) to democratic reform in order to explain a domestic actor’s ‘partial’ or ‘non-complying’ behaviour.Footnote16

The interactive model: interplay, instruments, and domestic leverage

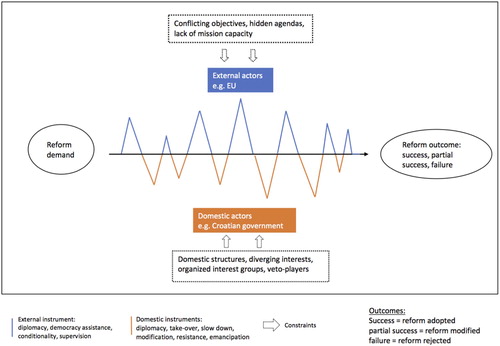

In line with Poppe, Leininger and Wolff and the other contributions to this special issue, I suggest to bring in a dynamic perspective to democracy promotion research, and to conceptualize the external-domestic interplay as a permanent, interactive process of action and reaction through negotiations where both sides are competent to take action independently. External and domestic actors negotiate over content, scope, procedure and pace of reform. Not only the external, but also the domestic side disposes of a set of instruments shaping the reform agenda and its implementation. Domestic actors are not just passive receivers, but can willingly set, accept, modify, and completely change and reject the reform agenda taking domestic actors’ preferences, behaviours and constraints into account. These facts need to be included into an interactive model of democracy promotion negotiations (see ).

The instruments external actors dispose of in the negotiations are well described in the democracy promotion and EU integration literature. They include diplomacy, democracy assistance, conditionality, and supervision.Footnote17 The external instruments differ according to the general level of leverage external actors can mobilize to influence the democratic reform process, with diplomacy having the least leverage and supervision the most. While analytically emphasizing distinct reasoning, in practice, these instruments are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but are often combined.

Diplomacy describes the practice of dialogue and negotiation between representatives of external and domestic actors. Diplomacy is primarily based on arguments rather than material incentives, and can include alliance-building with other actors.Footnote18 Democracy assistance refers to the provision of financial resources or political expertise to support institution-building and actors’ empowerment.Footnote19 Democracy assistance (in the literature also called ‘democracy aid,’ ‘political aid’ or ‘targeted aid’) and development assistance (for broader purposes of socio-economic development) are part of a donor’s total foreign aid. Democracy assistance functions top-down for political institution-building and administrative capacity-building, and is transmitted bottom-up with respect to the development civil society and free press.Footnote20 Conditionality is a bargaining strategy of reinforcement by reward. As an example, the EU uses conditionality when it provides the incentive of EU membership to encourage a target government to comply with its conditions. Through conditionality, a donor rewards target governments for aligning with its political conditions, and withholds (financial, technical, political) rewards for non-compliance.Footnote21 Supervision is the (temporary) takeover of decision-making and the implementation of capacity by an external actor. Softer forms of supervision are international peace- and state-building missions with a mandate to monitor or supervise democratization.Footnote22

Unlike previously assumed, however, domestic actors also do dispose of a large set of instruments with which they can succeed in convincing external actors to accept modifications of drafted laws and to change reform objectives. External actors might even be obliged to drop certain aspects of desired reforms. Based on previous empirical research, the author of this contribution together with a co-author identifies a set of instruments that allow domestic actors either to accept or to alter, modify, change or reject reform demands. The six instruments are: diplomacy, take-over, slowdown, modification, resistance, and emancipation.Footnote23 Diplomacy refers to the practice of argumentation and persuasion over the direction of reform or specific details of a policy draft and its implementation. Arguments and bargaining strategies are used to strengthen the domestic position and convince the international counterpart to accept a compromise acceptable to both sides. Take-over is a practice in which domestic actors follow specific external demands in the process of policy-making, taking over the goals and practices of the external actors. This term describes the domestic side’s acceptance of the ideas and practices of external actors. Slowdown refers to the domestic actor’s actions that result in the deceleration of initiated reforms, such as the withdrawal of administrative resources from the policy, inability to reach an agreement, and postponement of decision-making in parliament. In modification, domestic actors selectively change external reform proposals. Modification implies the introduction of changes to external reform drafts or the re-interpretation of adopted laws in a way that is considered more appropriate to the given context. Resistance describes the rejection of external reform demands. Resistance might be targeted against the external proposals of a specific reform initiative, the complete reform drafts, parts of reform drafts, or recommendations to proceed in the implementation of a new policy. Emancipation refers to the development of reforms independent from external demands. Because of an increased awareness of mismatches between external demands and conditions on the ground, or due to growing self-esteem, domestic actors may begin to search for their own solutions to problems, thereby possibly disregarding external reform proposals.

The interaction model of democracy promotion assumes that diplomacy is a constant between external and domestic actors. Meeting, talking, and negotiating over the content, scope, procedure and pace of reforms take place continuously during any reform process between external and domestic actors.

If both sides agree about the content, scope, procedure and pace of a reform, interaction is less antagonistic. Moderately intrusive instruments such as democracy assistance on the external side and take-over on the domestic side are used in addition to diplomatic interactions. When the level of conflict in interaction increases (for example due to external and domestic constraints that emerge on one or both sides, what is detailed further below) the involved actors resort to more antagonistic instruments. Domestic actors make use of slowdown and modification to alter reform proposals. External actors might threaten with the withdrawal of democracy assistance or the tightening of conditionality. At the highest point of conflict, external actors might resort to supervision whereas domestic actors make use of resistance or emancipation: either they resist adopting or implementing a reform proposal, or they emancipate fully and take the lead in proposing a new proposal. The model assumes that, at any point, actors can decide whether to resort to more or less antagonistic instruments, as the table of instruments and its level of intrusiveness does not imply any automatism in their employment.

Following the literature on preference formation, it can be assumed that actors are consistent in their preference structure and prefer the policy outcome in which they are least vulnerable. They place greater weight on short-term trade-offs than on possible long-term trade-offs, and prefer gains over losses.Footnote24 Uncertainty about the (intended and unintended) effects of reform policies reinforces this mechanism. As domestic actors prefer short-term gains and cannot perfectly foresee the possibly negative consequences of reform, the perceived vulnerability against externally demanded reforms increases what can result in more antagonistic behaviour in democracy promotion negotiations. Likewise, external actors want to see their reform demands be adopted in domestic politics, thus referring to more antagonistic instruments if necessary.

External-domestic interaction in democracy promotion negotiations can either lead to full, partial or non-agreements. Assessed through the lenses of democracy promoters, the former two can be judged a (partial) democracy promotion success; the latter needs to be judged as a democracy promotion failure. In other words, if the democratic reform proposed by the external actor is adopted right away by the domestic actors without any substantial change compared to the original version of the democracy promoter’s reform proposal, the outcome can be called a democracy promotion success. If both sides agree to moderately or significantly revise the original reform proposal and adopt this new version, the outcome can be called a partial democracy promotion success: the original proposal was revised, but the external actors agree upon the modifications and adaptions. If the reform proposal is completely rejected by the domestic side and there is no domestic alternative to it, the reform can be called a democracy promotion failure.

It needs to be noted that the interaction model does not suggest an ideal way of how to achieve a reform success. Instead, and in line with the general research framework proposed in this special issue,Footnote25 it offers an analytical scheme allowing the description and analysis of the interactive process of itinerated negotiations that takes place between the external and domestic actors in democracy promotion. Complementing this special issue’s framework, the model serves to identify external and domestic instruments that are actually used and to analyse precisely at which juncture during the reform process external and domestic actors employ which instruments. The model also allows classifying the process outcomes. Thereby, the model enables the researcher to gather information on reform processes in a systematic way and to compare reforms over different actors and contexts. Finally, it takes external and domestic constraining factors into account while avoiding any pejorative notion of complete ‘unwillingness,’ ‘incapacity’ or ‘illiberalism.’ External and domestic constraints will be further detailed in the next section.

External and domestic factors constraining the negotiation interplay

In line with transition and democracy promotion research,Footnote26 the here proposed interplay model acknowledges the relevance of agency and structure as well as their mutual co-constituency. Several structural and behavioural factors constrain on both sides the interplay between external and domestic actors in democracy promotion negotiations. On the external side, these are conflicting objectives, hidden agendas, and a lack of mission capacity. On the domestic side, these are domestic structures, diverging interests and the existence of organized domestic interests and domestic veto-players. Not all factors can be observed all the time and all at once. But one or more factors might be present at specific points in time influencing the course of negotiations and creating junctures for both sides. The external and domestic factors are now further detailed.

External constraints

Conflicting objectives

International democracy promotion seeks to foster democratic institution-building and the empowerment of democratic political actors, as well as the creation of favourable context conditions for democratization. However, there is no consensus on what and how to achieve a positive outcome among Western donors. In the study at hand, European democracy promoters, such as the European Commission, the governments of EU member countries and their respective development agencies, as well as other regional organizations like the European Council and OSCE, and several European-based non-governmental organizations work in the field of democracy promotion while not sharing a consensus about content, scope, procedure and pace of democratization reforms. Some might favour EU accession as a valuable tool for promoting democracy in (potential) EU candidates, other might be totally against it. Consequently, the mismatched policy objectives of different actors serve to compromise democracy promotion. Such conflicts of objectives among donors negatively influence the effectiveness of democracy promotion when not managed well and donor coordination and harmonization is missing.Footnote27

Hidden agendas

At the same time, economic or security issues might be higher ranked on the policy agenda of external actors what is, however, rarely explicitly revealed when democratization reforms are negotiated. Such hidden agendas also might negatively influence democracy promotion leverage.

Lack of capacity

Furthermore, external democracy promoters might suffer from poor capacity in the field. UN peace-building missions, for example, are regularly criticized for being “habitually under-funded, under-equipped and understaffed”Footnote28 and for using wrong “habits, practices and narratives.”Footnote29 In addition, time frames of democracy promoting projects and mission deployments are often criticized as being too short to create a considerable impact on democracy levels.Footnote30 Recent studies find evidence for a positive relationship between greater mission capacity of an external actor and better outcomes in a target country’s democratization track record.Footnote31

Domestic constraints

Domestic structures

Most processes of democratization take place nowadays in post-conflict and fragile contexts, as for example in the Western Balkans where new states emerged out of the violent dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) and the resulting Balkan wars. In such contexts, the conditions conducive to democratization are usually absent.Footnote32 Recent warfare, challenged statehood, and on-going ethnic tensions within the countries, in combination with destroyed infrastructure, the massive displacement of refugees, rising levels of poverty and unemployment, high levels of corruption and criminality and a weak civil society, represent difficult context conditions for successful democracy promotion.Footnote33 Democratization efforts, such as the organization of democratic elections, therefore risk the transfer of cleavages amassed through violent conflict into the political realm, creating potentially unstable, ineffective and compromised political institutions.Footnote34 If such institutions exist, the administrative capacity to negotiate and manage reform projects on the domestic side might be reduced (but not totally absent).

Diverging interests

As a consequence of diverging political, economic or social preferences, the attitude of domestic actors towards external demands for democratic reforms can range from very supportive to very critical. However, even when they are critical, the governments and state officials of democratizing countries do not necessarily oppose the fundamental ideas that lie behind an external reform initiative – such as improving transparency, accountability, or service-orientation to citizens – but rather might substantially disagree with the scope and scale of desired reforms, the necessary degree of local third-party participation in policy-making, or the process of implementing the reform package.Footnote35

Other domestic actors and veto players

Overall, domestic actors seek to defend their interests on two levels. On the first level, the external-domestic interaction between external democracy promoters and domestic recipients (that are political actors such as governments, ministries, or parliaments) unfolds. Here, conflicts over preferences, reform approaches and reform implementation might emerge between external and domestic actors involved in the negotiation process. On the second level, domestic political actors have to interact and negotiate with domestic third party actors (such as oppositional parties, political unions, civil society actors and the like). Here, domestic governments have to consider three issues: First, domestic third party actors can act as veto players whose consent is necessary to draft, adopt or implement a reform package.Footnote36 Second, governments and state officials have to consider the framing of reforms that might touch upon issues of national identity.Footnote37 Third, national governments must take the possible reform effects for the electorate into consideration, meaning they must anticipate social mobilization for or against proposed reforms. Context-insensitive reform demands might not resonate with local needs or the everyday of affected citizens.Footnote38

In sum, without seriously acknowledging the behaviour of domestic actors and the constraints they are confronted with and instead portraying them as ‘unwilling’ or ‘unable’ to reform, international democracy promoters tend to neglect the rational interests of domestic political actors and the dynamics of the domestic political arena. Domestic actors might seek to modify, adapt, change or reject external reform demands due to preferences that diverge from external actors’ preferences or because of domestic constraints such as the existence of domestic veto players and specific domestic conditions that do not fit the reforms demanded by external actors.

A case study on public administration reform in Croatia

The external-domestic interaction at the micro-level of public administration reform in Croatia serves as an empirical example for the dynamic external-domestic interplay in enlargement negotiations as described above. Croatia represents the case of a country in transition with a conflict history on its way to institutionalize and consolidate democratic institutions. Croatia’s experience is highly representative of the extraordinarily intense efforts of the international community to overcome the consequences of violent state dissolution and civil war through state-building and democracy promotion. The EU in particular has promoted democratization in Croatia with the opening of an accession perspective. The Union set the conditions for EU membership and thereby established a blueprint for Croatia’s transition to democracy. At various stages of the reform process, it provided aid, offered expert consultancy, and supervised democratization. Studying the interplay between the EU and the Croatian government captures the full range of external instruments used in democracy promotion.

The Croatian political elite showed great willingness to implement democratic reforms, while at the same time remaining critical of what they viewed as ‘too much’ external interference in domestic state affairs. This variance in attitudes is reflected in the respective behaviours of domestic actors in policy-formulation and implementation and allows systematizing the toolbox of instruments used by domestic actors to shape and modify the reform agenda. Croatia’s path to democracy allows an exploration of the conditions constraining the external-domestic interplay in enlargement negotiations. Some of the external and domestic constraints as elaborated above influence the course of negotiations between the EU and the Croatian government. Finally, Croatia’s reform process shows indication for reform successes and reform failures.

I trace the process of formulating and adopting two reform initiatives in Croatia’s Public Administration Reform (PAR), namely the General Administrative Procedures Act (GAPA) and the Civil Servants Salary Act (CSSA). Public administration reform is a substantial part of external actors’ democracy promotion agenda as a democratic state requires an effective, transparent, corruption-free public administration. Such an administration shall respect the citizens’ democratic rights (civil rights and political liberties) and work upon democratic rules (e.g. respecting the dignity of citizens and treating them all as equals) and procedures (e.g. allowing for stakeholders’ involvement in reform processes).

The two reform initiatives have been chosen because they ranked highest on the EU PAR agenda and show the required output variance. They serve as sub-units of analysis.Footnote39 Holding context conditions constant through the comparison of two sub-units, the use of external and domestic instruments of democracy promotion can be studied and the factors that particularly influence on both sides the negotiation interplay between the EU as the external and the Croatian government as the domestic actor can be discovered.Footnote40 Process-tracing serves here well to reconstruct the complex interaction process between domestic and external actors, revealing the use of instruments and the causal mechanisms that lead to the respective reform outputs.Footnote41

Negotiating the reforms

The overall goal of the EU (and other external actors) in engaging in Croatia’s PAR was to optimize the structures and mechanisms of administrative state bodies based on democratic principles. A reliable, open, transparent, and citizen-oriented public administration was considered a prerequisite of a good business environment and a better living standard of all citizens.Footnote42 As regards the content of reform, in the GAPA, the EU and the Croatian government negotiated how to simplify and speed up administrative decision-making structures to improve services for both citizens and businesses. In the CSSA, it was negotiated how to unify the wage system for civil servants at the different levels of state administration and render it more competitive. A burden sharing can be observed when it comes to the reform process as such: Whereas the EU initiated the drafting the reform proposals, the Croatian Ministry of Administration (MoA) was responsible for the adoption and implementation of the reforms. The pace of reform was a constant issue between the negotiation partners as the EU constantly wanted to speed up the negotiations whereas the Croatian side used its leverage to retard them. The negotiations that began in 2003 and took until 2011 produced an agreement for the GAPA that included substantial changes to the original proposal (e.g. partial democracy promotion success). For the CSSA, no such agreement was found (e.g. democracy promotion failure) and the Croatian side decided to stick to the status quo of paying civil servants not in the frame of a unified wage system. Next, the two reform processes are briefly described following the lines of a policy-cycle, focusing in the phase of agenda-setting, policy formulation and policy adoption.Footnote43

Tracing the GAPA reform process

To set the agenda in 2003, the EU offered financial assistance to reform the GAPA through the CARDS 2003 project.Footnote44 At first, reform demands were met with resistance by the Croatian government. Only after discussions, it agreed to EU demands and to the CARDS 2003 project, which was scheduled to begin in 2006.

The first phase of policy-formulation (2003–2005) was characterized by low levels of external-domestic interaction. In 2004, the then-State Secretary of the MoA assigned low priority to the reform, establishing a working group that was never invited to meet. The following year, external actors offered democracy assistance to push the process forward. SIGMA advised on policy-formulation by assessing possible amendments to the old GAPA.Footnote45 During the second phase of policy-formulation (2006–2008), external actors and the MoA interacted more intensively. When the CARDS project started, the EU project team engaged in advising on policy-formulation, analysing reform options, and preparing policy and strategy papers to be adopted by the cabinet. The Croatian government again used slowdown as an instrument to counter reform demands, adopting all pre-formulated documents but not engaging in drafting a new law based on these documents, thus paying lip service to the international advisors. As policy adoption approached, interactions began to become more antagonistic. At the end of 2007, the EU project team presented its draft law for the new GAPA, which consisted of a completely new legal framework. The proposal was met with resistance by the Croatian government as it was considered to be far-reaching. Subsequently, the MoA used the instrument of modification and installed a new working group composed of MoA employees and moderate Croatian academics to re-write the draft law, based on the old GAPA. In response, the EU Delegation resorted to more coercive means of diplomacy to exert pressure on the ministry. The delegation sought alliance with other external actors, asking SIGMA to issue recommendations on the results of the working group, with partial success. Some recommendations were included by the ministerial working group, but without alterations to the basic structure.

In March 2009, the domestically prepared draft of the GAPA was adopted in parliament. In response, the EU Delegation applied the instrument of conditionality to push for further changes. In the October 2009 negotiations, the EU argued that the law did not meet EU soft political criteria with regard to EU best practices for administrations and warned that accession might be endangered if no amendments were made.Footnote46 However, the MoA made it quite clear that it would not accept further changes to the new GAPA, arguing that they had “found their own solution” to integrate essential EU demands while maintaining a basic structure in line with established Croatian administrative traditions.Footnote47 After intensive discussions, the EU dropped its demands for changes to the new GAPA.

To sum up, the reform of the GAPA can be judged as a partial democracy promotion success. A new law was adopted and enacted, but this law differs to a great extent from the original proposal made by external consultants and leaves the basic structure of the old system intact.Footnote48 The Croatian government was thus satisfied with the result, whereas the EU would have favoured further changes.

Tracing the CSSA reform process

Like for the GAPA, the EU set the agenda for a CSSA reform in 2003. The Croatian government took over EU demands as a more transparent wage system was in its interests as well.

In the first policy-formulation phase (2003–2008), the interactions between the Croatian government and international actors followed a repeating pattern: External actors provided policy advice via democracy assistance and Croatian decision-makers reacted with a general take-over of the EU goals, but then the Croatian government used slowdown, postponing actual decisions. Several times, the MoA installed working groups with all affected ministries and trade unions participating to negotiate a new CSSA. EU, the World Bank, and SIGMA provided democracy assistance: external consultants analysed the Croatian system, made policy recommendations and proposed draft laws to the working group.

In 2005, the government postponed the decision on an externally drafted policy to the next year.Footnote49 The government took up negotiations within the tripartite system again in 2006 to unify the salary system. Again, a draft law was produced with the advice of external consultants. It was adopted by the Croatian government, but was not submitted to the Croatian parliament in 2007.Footnote50 Croatia’s government justified its retarding strategy with vague fiscal impact of that law that might risk its dismissal in parliament. The decision was postponed to take on discussions at a later stage.Footnote51

In a second policy-formulation phase (2008–2009), external actors reverted to the instruments of diplomacy and conditionality in an attempt to speed up the reform process. The EU used diplomacy, forming alliance with all involved donors and recommending the Croatian government to speed up the reform.Footnote52 As the Croatian government and the trade unions were still unable to reach an agreement and thus continued to retard the reform process, the EU resorted to the use of conditionality and made the adoption of a CSSA a pre-condition for further financial grants to the MoA.Footnote53 The Croatia’s government resisted this EU demand because it anticipated that no agreement could be reached with the trade unions at this point. In the end, the EU dropped the pre-condition. It provided financial assistance despite the lack of compliance. General take-over of EU demands on the part of domestic actors followed. The Croatian government adopted another draft law with the help of external advice and through discussions within the social partners. This draft was submitted to the Croatian parliament in January 2009. This time, however, the parliament used slowdown techniques and postponed the decision due to doubts about the financial sustainability. Severe protests and strikes by trade unions followed because they feared a new proposal would be less favourable to their demands.

In autumn 2009, the EU started a third policy-formulation phase (2009–2011) and resorted to the instrument of conditionality. It made the adoption of the CSSA a benchmark of Chapter 22 during accession negotiations.Footnote54 This demand was met with resistance from the Croatian government, who insisted on reaching an agreement with the trade unions first in order not to face severe strikes and social unrest. In the end, the EU dropped its demand for a new CSSA as part of EU benchmarks.

To sum up, the reform of the CSSA cannot be evaluated a democracy promotion success, as no new law was adopted. Finding a compromise between all the actors involved in the reform of the CSSA proved to be very difficult, due to widely diverging interests. However, this also means that domestic trade unions were able to influence the process and successfully prevented a reform in disfavour of civil servants’ interests.

Comparative analysis of the negotiation interplay in democracy promotion

The comparative analysis of the two reform projects, the GAPA and the CSSA, illustrates, first, that enlargement negotiations entail a constant exchange of diplomatic means: meeting, talking, and negotiating over the content, scope and pace of reforms take place continuously during the reform process between the external and domestic actors, here the EU and the Croatian side.

Second, it shows that all external and domestic instruments are employed during the negotiation process. Evidence suggests that domestic actors are not just passive recipients of democracy promotion but either actively accept (parts of) the reform proposal or actively alter the reform process through the use of a wide range of instruments. Domestic actors influence external preferences and may succeed in convincing external actors to accept modifications of drafted laws and change reform objectives. In the two reform initiatives, the EU was obliged to drop certain aspects of its desired reforms despite using all available instruments to avoid this output.

Third, the external-domestic interplay followed an escalation curve. In the early phase of policy-formulation, interaction was less antagonistic. Democracy assistance on the external side and take-over on the domestic side were used in addition to diplomatic interactions. However, when the point of policy-adoption approached, the level of conflict in interaction increased. In the case of the CSSA, when the trade unions entered the scene on the domestic side to oppose this reform project, the Croatian government referred to slowdown and resistance to avoid full compliance with external reform demands. The EU increased its pressure with intensified diplomacy and set more fine-grained conditions in order to enforce the adoption of the CSSA, thus far without success (reform failure). In the case of the GAPA, no such strong third actor emerged. Nevertheless, the Croatian government sought to change the proposal, using slowdown and modification. Again, the EU intensified diplomacy and hinted to the conditions to be fulfilled before the respective chapter in enlargement negotiations could be closed. In the end, the reform passed, but as a consequence of the modification strategy employed by the Croatian side, it differed significantly from to the original demands made by the EU (partial reform success).

Fourth, the notion of ‘unwillingness’ or ‘inability’ does not capture the domestic side adequately. Indeed, the Croatian government showed great willingness to further democratization, but it also had to respect the preferences of powerful organized domestic actors such as the trade unions that effectively opposed the reform of the civil servants’ salary act. Multi-faceted motivations, interests and concerns of domestic actors about the potential implications of reforms can be observed. Challenges of coordinating reforms with various domestic stakeholders (such as the Croatian government, the line ministries, the parliament, the trade unions) became visible. Domestic motivations for supporting or rejecting external reform proposals existed, as well as the need for domestic political actors to bargain with the trade unions representing civil servants. Both factors explain why the outputs of democracy promotion diverge from external actors’ expectations. In fact, EU officials appeared in this case as rather reluctant to secure voice representation in including third-party stakeholders, since they are perceived as a potential obstacle to reform making democracy promotion much more time and resource intense. Thus, it can be judged a success that domestic players became empowered to the extent to competently engage in the process of political decision-making and express diverging preferences – although the CSSA reform as such has to be classified as a reform failure, according to the scheme of possible outcomes as introduced in the previous section.

Finally, it needs to be clearly noted that there is still a certain asymmetry involved in democracy promotion as demands for democratic reform and the initiative to place these issues on the agenda came mostly from the EU. Domestic actors in Croatia had to accept the reform agenda in return for becoming a EU member. They had to learn how external actors organize policy-making, projects, and programmes, and subsequently adopt the implementation of liberal democratic principles in the Croatian political system. Furthermore, within PAR in Croatia, there is no evidence of incidents in which domestic actors took the lead in proposing a reform issue to external actors that became the object of democracy promotion, thus, emancipation was rarely if ever used as a domestic instrument.

Conclusions

This article suggests to conceptualize democracy promotion as interactive interplay between external and domestic actors who intensively negotiate about scale, scope, and contents of democratic reforms in which both sides dispose of a wide range of instruments to set, modify and change the reform agenda. It is conceived as a model focusing on the external-domestic interplay and both sides’ instruments therein instead of a hierarchical notion of donors disposing leverage over recipients in democracy promotion. A brief case study on public administration reform in Croatia in the context of EU enlargement negotiations served as an empirical illustration.

The empirical example puts further emphasis on the need to overcome the unidirectional notion of the asymmetric relationship of external leverage and domestic passivity in democracy promotion. Instead, it is necessary to more seriously engage with the interactive interplay between external and domestic actors in specific structural contexts constituting influential constraints. The interaction model identifies those instruments that domestic actors employ to accept, modify or adapt external reform demands with regard to local needs, studies domestic motivations for critical attitudes about externally promoted reforms, and looks upon the domestic constraints in which political actors operate. It sheds light on the struggles fought in the domestic arena of democratizing countries and connects them to the outcomes of democracy promotion, offering a more fine-grained analysis of why some democracy reform proposals succeed, some are substantially altered and some fail after all. The empowerment of domestic actors as competent players in the political arena, their mode of interaction with external actors as well as constraints on both sides explain democracy promotion’s (partial) successes or failures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sonja Grimm

Sonja Grimm is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz, Germany. She specializes in comparative democracy and democratization studies, with a special focus on democracy promotion and state-building in postconflict societies and fragile states. Before moving to Konstanz, Sonja Grimm worked at the Social Science Research Center Berlin (WZB) and taught at Humboldt University Berlin. She co-edited two special issues for Democratization on “War and Democratization: Legality, Legitimacy, and Effectiveness” (15, no. 3 (2008)), and “Do All Good Things Go Together? Conflicting Objectives in Democracy Promotion” (19, no. 3 (2012)). From 2005 until 2015, she was spokesperson for the network “External Democracy Promotion” (EDP). More about her can be found at [www.sonja-grimm.eu].

Notes

1 Schimmelfennig and Scholtz, “Legacies and Leverage”; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, “Governance by Conditionality.”

2 Schimmelfennig and Scholtz, “Legacies and Leverage”; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, “Governance by Conditionality.”

3 Levitsky and Way, “Linkage versus Leverage”; Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism.

4 Schimmelfennig and Scholtz, “Legacies and Leverage”; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, “Governance by Conditionality.”

5 See Poppe, Leininger and Wolff’s analytical framework in this issue.

6 See Poppe, Leininger and Wolff’s analytical framework in this issue.

7 Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, “Governance by Conditionality.”

8 Börzel and Risse, The Transformative Power of Europe.

9 Beichelt, “The Research Field,” for an overview. Levitsky and Way, “Linkage versus Leverage”; Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism.

10 Levitsky and Way, “Linkage versus Leverage,” 379.

11 See also Leininger, “Bringing the Outside In”; and Schmitz, “Domestic and Transnational Perspectives,” 404.

12 For norm localization in the IR literature, see Acharya, “How Ideas Spread”; Wiener, A Theory of Contestation; Zimmermann, Global Norms; among many others. For justice conflicts, see Poppe and Wolff, “The Normative Challenge.”

13 Elbasani, “Europeanization Travels”; Tholens and Gross “Diffusion, Contestation and Localisation.”

14 Mac Ginty, International Peacebuilding and Local Resistance; Richmond, “Resistance and the Post-Liberal Peace”; Kappler and Richmond, “Peacebuilding and Culture”; Richmond and Mitchell, “Peacebuilding and Critical Forms.”

15 Carothers, Critical Mission, 137; Richmond, “Resistance and the Post-Liberal Peace,” 669; Richmond and Mitchell, “Peacebuilding and Critical Forms,” 326.

16 Caplan, “Partner or Patron?,” 230; Chesterman, “Ownership in Theory and Practice”, 16; Doyle and Sambanis, “International Peacebuilding”; Feeny and McGillivray, “Aid Allocation to Fragile States”; Hameiri, “Capacity and its Fallacies,” 56.

17 Following Grimm, Erzwungene Demokratie, 135–45, I prefer the term “supervision” over “coercion”.

18 Berridge, Diplomacy.

19 Burnell, “Democracy Assistance,” 4–5.

20 Carothers, Aiding Democracy Abroad.

21 Koch, “A Typology of Political Conditionality”; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, “Governance by Conditionality,” 662.

22 Grimm, Erzwungene Demokratie, 135–45.

23 The toolbox of domestic instruments has been inductively developed through intensive process-tracing as described in Groß and Grimm (“The External-Domestic Interplay,” 920–22).

24 Streich and Levy, “Time Horizons,” 199; Walter, “A New Approach,” 412.

25 See Poppe, Leininger and Wolff’s analytical framework in this issue.

26 See Poppe, Leininger and Wolff’s analytical framework in this issue, 4.

27 Grimm and Leininger, “Not all Good Things Go Together.”

28 Fortna and Howard, “Pitfalls and Prospects,” 39.

29 Autesserre, Peaceland.

30 Ramsbotham, “Reflections on UN,” 179; Zeeuw, “Projects Do Not Create.”

31 Steinert and Grimm, “Too Good to be True?.”

32 Caplan, International Governance of War-torn Territories; Paris, “International Peacebuilding,” Paris, At War’s End; Fortna, “Peacekeeping and Democratization,” 46.

33 Zürcher et al., Costly Democracy; Milačić “A Painful Break.”

34 Zeeuw and Kumar, Promoting Democracy.

35 Groß and Grimm, “The External-Domestic Interplay,” and Groß and Grimm, “Conflicts of Preferences and Domestic Constraints.”

36 Tsebelis, Veto Players.

37 See as an example the condition to cooperate with the ICTY that touches national identity: while the EU and the ICTY perceived the indicted suspects as war criminals, the governments and a majority of the population in Serbia and Croatia perceived them as national heroes (Freyburg and Richter, “National Identity Matters”).

38 Groß and Grimm, “Conflicts of Preferences and Domestic Constraints.”

39 Gerring “What is a Case Study,” 342–3.

40 The analysis is primarily based upon 30 semi-structured expert interviews held in Croatia between August and November 2011, complemented by document analysis. Domestic interviewees (marked with “D”) were selected from the MoA (at different levels in the hierarchy), the Chief Negotiators’ Office, national agencies managing EU assistance, and trade unions. External actors (marked with “E”) included members of the EU delegation in Croatia, team members for EU financial assistance projects, and officials of a other donors engaged in Croatia.

41 George and Bennett, Case Studies and Theory Development, chap. 10.

42 Common standards of public administration shared by EU Member States are laid down in the “European Administrative Space” (EAS) policy and EU Best Practices. See also SIGMA, European Principles, 8–14.

43 Scharpf, “Verwaltungswissenschaft”. More details about the reform process are described in Groß and Grimm, “The External- Domestic Interplay” and Groß and Grimm, “Conflicts of Preferences and Domestic Constraints.”

44 EU democracy assistance for PAR has been provided through two framework programmes: the “Community Assistance for Reconstruction, Development and Stabilization” (CARDS) and subsequently the “Instrument of Pre-Accession Assistance” (IPA).

45 SIGMA (“Support for Improvement in Governance and Management”) is a joint initiative of the EU and the OECD providing technical assistance and expert advice. Interview D6; Republic of Croatia, 2004 Pre-Accession Economic Recovery Programme.

46 Interview D2.

47 Interview D6.

48 European Commission, Croatia 2011 Progress Report.

49 Republic of Croatia, 2005 Pre-Accession Economic Recovery Programme, 76.

50 Republic of Croatia, 2006 Pre-Accession Economic Recovery Programme, 66.

51 Interview E2.

52 Interview E3.

53 Interview E3.

54 Interview D4.

Bibliography

- Acharya, A. “How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism.” International Organization 58, no. 2 (2004): 239–275. doi: 10.1017/S0020818304582024

- Autesserre, S. Peaceland: Conflict Resolution and the Everyday Politics of International Intervention. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Berridge, G. R. Diplomacy: Theory & Practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2010.

- Beichelt, T. “The Research Field of Democracy Promotion.” Living Reviews in Democracy, July, 2012 . http://democracy.livingreviews.org.

- Börzel, T. A., and T. Risse. The Transformative Power of Europe: The European Union and the Diffusion of Ideas . KFG Working Paper (1). Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 2009.

- Burnell, P. “Democracy Assistance. The State of the Discourse.” In Democracy Assistance. International Co-operation for Democratization, edited by P. Burnell, 3–33. London: Frank Cass, 2000.

- Caplan, R. “Partner or Patron? International Civil Administration and Local Capacity-building.” International Peacekeeping 11, no. 2 (2004): 229–247. doi: 10.1080/1353331042000237256

- Caplan, R. International Governance of War-torn Territories. Rule and Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Carothers, T. Aiding Democracy Abroad. The Learning Curve. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1999.

- Carothers, T. Critical Mission. Essays on Democracy Promotion. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2004.

- Chesterman, S. “Ownership in Theory and Practice. Transfer of Authority in UN Statebuilding Operations.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 1, no. 1 (2007): 3–26. doi: 10.1080/17502970601075873

- Doyle, M. W., and N. Sambanis. “International Peacebuilding: A Theoretical and Quantitative Analysis.” American Political Science Review 94, no. 4 (2000): 779–801. doi: 10.2307/2586208

- Elbasani, A. “Europeanization Travels to the Western Balkans: Enlargement Strategy, Domestic Obstacles and Diverging Reforms.” In European Integration and Transformation in the Western Balkans, edited by A Elbasani, 3–21. London: Routledge, 2013.

- European Commission. Croatia 2011 Progress Report . SEC(2011) 1200 Final. Brussels: European Commission, 2011.

- Feeny, S., and M. McGillivray. “Aid Allocation to Fragile States: Absorptive Capacity Constraints.” Journal of International Development 21, no. 5 (2009): 618–632. doi: 10.1002/jid.1502

- Fortna, V. P. “Peacekeeping and Democratization.” In From War to Democracy. Dilemmas of Peacebuilding, edited by A. K. Jarstad and T. D. Sisk, 39–79. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Fortna, V. P., and L. M. Howard. “Pitfalls and Prospects in the Peacekeeping Literature.” Annual Review of Political Science 11 (2008): 283–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.041205.103022

- Freyburg, T., and S. Richter. “National Identity Matters. The Limited Impact of EU Political Conditionality in the Western Balkans.” Journal of European Public Policy 17, no. 2 (2010): 263–281. doi: 10.1080/13501760903561450

- George, A. L., and A. Bennett. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

- Gerring, J. “What is a Case Study and What is it Good For?” American Political Science Review 98, no. 2 (2004): 341–54.

- Grimm, S. Erzwungene Demokratie. Politische Neuordnung Nach Militärischer Intervention Unter Externer Aufsicht. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2010.

- Grimm, S., and J. Leininger. “Not All Good Things Go Together. Conflicting Objectives in Democracy Promotion.” Democratization 19, no. 3 (2012): 391–414. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2012.674355

- Groß, L., and S. Grimm. “The External-domestic Interplay in Democracy Promotion: A Case Study on Public Administration Reform in Croatia.” Democratization 21, no. 5 (2014): 912–936. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2013.771257

- Groß, L., and S. Grimm. “Conflicts of Preferences and Domestic Constraints: Understanding Reform Failure in Liberal Statebuilding and Democracy Promotion.” Contemporary Politics 22, no. 2 (2016): 125–143. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2016.1153285

- Hameiri, S. “Capacity and its Fallacies: International State Building as State Transformation.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 38, no. 1 (2009): 55–81. doi: 10.1177/0305829809335942

- Kappler, S., and O. P. Richmond. “Peacebuilding and Culture in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Resistance or Emancipation?” Security Dialogue 42, no. 3 (2011): 261–278. doi: 10.1177/0967010611405377

- Koch, S. “A Typology of Political Conditionality Beyond Aid: Conceptual Horizons Based on Lessons from the European Union.” World Development 75 (2015): 97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.01.006

- Leininger, J. “‘Bringing the Outside In’: Illustrations from Haiti and Mali for the Re-conceptualization of Democracy Promotion.” Contemporary Politics 16, no. 1 (2010): 63–80. doi: 10.1080/13569771003593888

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. “Linkage Versus Leverage. Rethinking the International Dimension of Regime Change.” Comparative Politics 38, no. 4 (2006): 379–400. doi: 10.2307/20434008

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Mac Ginty, R. International Peacebuilding and Local Resistance: Hybrid Forms of Peace. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

- Milačić, F. “A Painful Break or Agony Without end? The Stateness Problem and its Influence on Democratization in Croatia and Serbia.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 17, no. 3 (2017): 69–387. doi: 10.1080/14683857.2017.1355030

- Paris, R. “International Peacebuilding and the ‘Mission Civilisatrice’.” Review of International Studies 28, no. 4 (2002): 637–656. doi: 10.1017/S026021050200637X

- Paris, R. At War's End. Building Peace After Civil Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Poppe, A. E., and J. Wolff. “The Normative Challenge of Interaction: Justice Conflicts in Democracy Promotion.” Global Constitutionalism 2, no. 3 (2013): 373–406. doi: 10.1017/S204538171200024X

- Ramsbotham, O. “Reflections on UN Post-settlement Peacebuilding.” International Peacekeeping 7, no. 1 (2000): 169–189. doi: 10.1080/13533310008413824

- Republic of Croatia. 2004 Pre-Accession Economic Recovery Programme. Zagreb, 2005.

- Republic of Croatia. 2005 Pre-Accession Economic Recovery Programme. Zagreb, 2006.

- Republic of Croatia. 2006 Pre-Accession Economic Recovery Programme. Zagreb, 2007.

- Richmond, O. P. “Resistance and the Post-liberal Peace.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 38, no. 3 (2010): 665–692. doi: 10.1177/0305829810365017

- Richmond, O. P., and A. Mitchell. “Peacebuilding and Critical Forms of Agency: From Resistance to Subsistence.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 36, no. 4 (2011): 326–344. doi: 10.1177/0304375411432099

- Scharpf, F. W. “Verwaltungswissenschaft als Teil der Politikwissenschaft. Planung als Politischer Prozess [Administrative Science as Political Science. Planning as Political Process].” In Aufsätze zur Theorie der Planenden Demokratie [Essays on a Theory of a Planning Democracy], edited by F. W. Scharpf, 9–23. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1973.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and H. Scholtz. “Legacies and Leverage: EU Political Conditionality and Democracy Promotion in Historical Perspective.” Europe-Asia Studies 62, no. 3 (2010): 443–460. doi: 10.1080/09668131003647820

- Schimmelfennig, F., and U. Sedelmeier. “Governance by Conditionality. EU Rule Transfer to the Candidate Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 11, no. 4 (2004): 661–679. doi: 10.1080/1350176042000248089

- Schmitz, H. P. “Domestic and Transnational Perspectives on Democratization.” International Studies Review 6, no. 3 (2004): 403–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-9488.2004.00423.x

- SIGMA. European Principles for Public Administration . SIGMA Papers No. 27. Paris: OECD Publishing, 1999.

- Steinert, J., and S. Grimm. “Too Good to be True? UN Peacebuilding and the Democratization of War-torn States.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 32, no. 5 (2015): 513–535. doi: 10.1177/0738894214559671

- Streich, P., and J. S. Levy. “Time Horizons, Discounting, and Intertemporal Choice.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51, no. 2 (2007): 199–226. doi: 10.1177/0022002706298133

- Tholens, S., and L. Gross. “Diffusion, Contestation and Localisation in Post-war States: 20 Years of Western Balkans Reconstruction.” Journal of International Relations and Development 18, no. 3 (2015): 269–264. doi: 10.1057/jird.2015.21

- Tsebelis, G. Veto Players. How Political Institutions Work. New York/Princeton: Russell Sage Foundation/Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Walter, S. “A New Approach for Determining Exchange-rate Level Preferences.” International Organization 62, no. 3 (2008): 405–438. doi: 10.1017/S0020818308080144

- Wiener, A. A Theory of Contestation. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.

- Zeeuw, J. D. “Projects Do Not Create Institutions. The Record of Democracy Assistance in Post-conflict Societies.” Democratization 12, no. 4 (2005): 481–504. doi: 10.1080/13510340500226036

- Zeeuw, J. D. and K. Kumar, eds. Promoting Democracy in Postconflict Societies. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2006.

- Zimmermann, L. Global Norms with a Local Face: Rule-of-law Promotion and Norm Translation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Zürcher, C., C. Manning, K. Evenson, R. Hayman, S. Riese, and N. Röhner. Costly Democracy. Peacebuilding and Democratization After War. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013.