ABSTRACT

India is often credited for its success as the world’s largest democracy, but variation in subnational democracy across its states has not been systematically incorporated into scholarship on subnational regimes. This paper develops a conceptualization of subnational democracy based on four constitutive dimensions – turnover, contestation, autonomy and clean elections – and introduces a comprehensive dataset to measure each of the dimensions between 1985 and 2013. The inclusion of India – an older parliamentary democracy with a centralized federal system – broadens the universe of cases for the study of subnational regimes, and reveals variation across constitutive dimensions that has not yet been theorized. The paper shows that threats to subnational democracy come from multiple directions, including the central government and non-state armed actors, that subnational variation persists even decades after a transition at the national-level, and that subnational democracy declines in some states in spite of the national democratic track record.

Introduction

Even though India is credited for its success as the world’s largest democracy, the panorama across India’s states is mixed. In West Bengal, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) had dominated the political arena, and governed for 33 years before losing the 2011 election. In Gujarat, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as a dominant force since 1998, and has only strengthened its hold on the state after the 2002 riots. In Bihar, elections during the 1980s were often so violent that the Election Commission of India had to postpone them on several occasions. An observer of Bihar lamented that “lawlessness facilitates electoral abuse” while “those who win elections by violence” suffer little consequences.Footnote1 Jammu and Kashmir held no elections at all for almost a decade between 1987 and 1996, as elected institutions were suspended and the state was placed under President’s Rule. Overall, as these examples illustrate, threats to subnational democracy across India’s states emerge from different directions.

Yet, despite substantial variation in the degree of democracy across states, India has received relatively scant attention in the burgeoning comparative literature on subnational regimes.Footnote2 Building on a necessary and sufficient condition concept structure, we develop a conceptualization of subnational democracy in India with four constitutive dimensions: turnover, contestation, autonomy and clean elections.Footnote3 This paper introduces a new comprehensive dataset for each of the dimensions between 1985 and 2013.Footnote4 Bringing an older democracy like India into the scholarly literature broadens the universe of cases for the study of subnational regimes, and thus reveals previously overlooked variation. Since the literature on subnational regimes has tended to focus on new democracies, the inclusion of India provides opportunities for the identification of temporal trends in a democracy with a longer track record. Moreover, by extending the comparative study of subnational regimes to a parliamentary democracy and a federal system where the center retains significant discretionary power, our analysis is able to detect empirical patterns beyond those already documented and theorized in the literature.

First, our analysis shows that threats to subnational democracy come from multiple directions. Conceptually, low scores on our index reflect deviations from democracy, and the index makes it possible to scrutinize the influence of each constitutive dimension. In addition to dominant party regimes and those without turnover, we identify “vertical” and “horizontal” threats to subnational democracy.Footnote5 The misuse of President’s Rule, a constitutional provision that allows the center to suspend elected institutions and to place states under central rule, constitutes a vertical threat. Horizontal threats emerge when actors outside the political system subvert elected institutions. In India, non-state armed groups have often called for a boycott of election, and have at times succeeded in disrupting the electoral process systematically and violently.

Second, our analysis highlights that regimes with low scores on the democracy index are not “holdouts” that have survived the transition to democracy at the national level. Rather, during the three decades we observe, the level of democracy varies significantly between states, and it declines markedly in a number of them. This indicates the need to theorize not just the survival and persistence of less democratic subnational regimes after national-level democratization, but also their emergence despite national-level democracy. Evidence of “backsliding” challenges scholars to probe whether national-level theories of democratic decline and breakdown can travel to the subnational level, and if so, under which conditions.Footnote6 Moreover, our analysis shows that the party identity of hegemonic regimes may change over the lifespan of a democracy. In their pioneering work on subnational democratization in India, Tudor and Ziegfeld focus on the emergence of opposition to the Indian National Congress Party (INC) from Independence in 1947 through 1989.Footnote7 Since Congress was the hegemonic party in most Indian states following Independence, Tudor and Ziegfeld conceptualize democratization as alternation in power. Temporally, our analysis picks up where theirs leaves off. We find that in several states the parties that initially challenged Congress have now become hegemons in their own right, similarly depriving voters of viable opposition choices. Overall, the analysis of subnational regimes in India raises important questions about the causes and consequences of variation in the level of democracy, in regime trajectories, and about different types of threats to subnational democracy. The measure we introduce in this paper is designed to allow comparativists and scholars of India to explore such questions. The first section of the paper conceptualizes subnational democracy and situates our index in the literature. The second section introduces the operationalization and data. We then move on to the analysis of empirical patterns and temporal trends, before concluding with a discussion of implications.

Subnational democracy in comparative perspective

In the wake of decentralization reforms during the 1980s and 1990s, comparativists started to pay more explicit attention to the institutional configurations within countries.Footnote8 Even though the importance of democracy in subnational units had already been flagged by Dahl, who stated that an account of “opportunities available for participation and contestation within a country surely requires one to say something about the opportunities available within subnational units”, in empirical research regime type had generally been treated as a national-level variable.Footnote9 The key reason for the neglect of subnational democracy, as stated by Dahl, was the lack of data, rather than the belief that the issue was substantively unimportant. Once subnational research took off in the wake of decentralization, it indeed revealed considerable variation within countries in the degree to which citizens enjoyed democratic rights. After democratization, authoritarian elites sometimes survived at the subnational level, subverting formally democratic institutions, and at times even deepening their rule. Decentralization, which had endowed subnational governments with authority and resources, insulated such regimes. While the empirical focus of the literature has been on Latin AmericaFootnote10, similar dynamics have been documented in post-Soviet countriesFootnote11 and the Southern United States during Jim Crow.Footnote12 Collectively, this burgeoning literature made clear that subnational variation in democracy is the rule, rather than the exception, especially in large federal democracies.Footnote13

While our empirical understanding of how these subnational regimes function internally and how they manage to sustain themselves vis-à-vis juxtaposed national regimes has grown, scholars have struggled to agree on a shared conceptual language to describe them. The early literature referred to them as “authoritarian enclaves”, “authoritarian archipelagos” or “democratic blind spots”.Footnote14 In doing so, scholars highlighted continuity with the pre-transition period and insulation from democratic politics at the national level. Empirical research has since demonstrated that these regimes are deeply entangled in a multi-level political system and managing their relationship with the center is vital for their survival.Footnote15 Moreover, national-level democracy imposes restrictions, distinguishing these regimes from full-blown authoritarian regimes. Terms like “closed game”,Footnote16 “hybrid regime”Footnote17 or “electoral quality”Footnote18 have become popular to highlight these mixed characteristics. Giraudy, on whose conceptual work we build, uses the term “subnational undemocratic regime” (SUR) to denote subnational units that fall short of democratic standards, even though they do not qualify as fully authoritarian.Footnote19 Since the intuition of our measure is continuous, rather than dichotomous, we instead refer to regimes as more or less democratic based on their scores on the index.

Democracy has been defined and measured in various ways, but competition for office is undeniably an essential component. Lipset defines democracy “as a political system which supplies regular constitutional opportunities for changing the governing officials, and a social mechanism which permits the largest possible part of the population to influence major decisions by choosing among contenders for political office”.Footnote20 Yet, as Vanhanen noted, it “has been easier for researchers to agree on the general characteristics of democracy than on how to measure it”.Footnote21 This difficulty is in part due to the realization that the nature of challenges to democracy varies across time and space. One recent challenge is that undemocratic regimes increasingly mimic formal democracy, but that the “opposition’s capacity to defeat incumbents (and/or their parties) in elections is significantly handicapped”.Footnote22 Elections in such regimes are competitive, but they are not free and fair.Footnote23 While many national authoritarian regimes “hide the de facto rules that shape and constrain political choices behind a façade of formal democratic institutions”,Footnote24 the need to distinguish between democratic regimes and those that merely mimic democracy is particularly pressing in the case of subnational regimes embedded in national-level democracies. Formal institutions are often identical across subnational units, but their meaning and relevance for determining who governs varies significantly, and in ways that are not easily visible.

Our starting point is the goal to devise a measure that is sensitive to the specific challenges for competitive politics in subnational regimes. One of the advantages of subnational comparative research is the ability to achieve greater measurement validity through a fine-grained and context-sensitive coding of cases.Footnote25 We focus on the challenges to subnational democracy in India, a large federal democracy which has so far received limited attention in the literature on subnational regimes. Bringing India into the debate allows us to extend existing efforts to theorize subnational democracy to a parliamentary democracy, to a federal system in which the center retains substantial discretionary powers, and to a country with an established democratic track record. This record brings into focus temporal trends that are more difficult to discern in countries that have democratized recently.

Before presenting our own conceptualization, we briefly discuss two extant measures of democratic characteristics across Indian states. The first measure, developed by Tudor and Ziegfeld, conceptualizes subnational democratization as the emergence of a viable electoral opposition to the Congress party, which dominated politics across all major Indian states following Independence.Footnote26 Specifically, subnational democratization is understood to occur only when “the party initially in power has peacefully conceded power to an opposing party”,Footnote27 and the previous opposition then serves a complete term in government. This measure worked well for the period of Congress-dominance from 1947 through 1989 on which the authors focus. Since then, however, India’s political landscape has become more fragmented, and other parties have replaced Congress as dominant players in certain states.

The second effort to measure democracy relies on a subnational adaptation of the Index of Democratization proposed by Vanhanen.Footnote28 This index is composed of two dimensions: competition (measured as 100 minus the percentage vote for the largest party) and participation (measured as the percentage of the total population who actually voted). Both dimensions are multiplied and the product is divided by 100, so that competition and participation weigh equally and that a high score on one cannot compensate the lack of the other constitutive dimension. Beer and Mitchell follow this measurement strategy in their study of the relationship between democracy and human rights at the state level,Footnote29 and Lankina and Getachew calculate the same index at the district level.Footnote30 Yet, even though in both studies the index succeeds in picking up relevant differences, we believe it overlooks key aspects of subnational democracy.

For one, interpreting participation in the context of universal suffrage is not entirely straightforward. Vanhanen highlights that South Africa under apartheid was classified as a non-democracy in his index because it scored poorly on the participation dimension.Footnote31 So including participation is crucial to identify regimes that discriminate against large groups of citizens based on race, religion or gender.Footnote32 In the context of universal suffrage, however, it is not clear that higher participation is necessarily better.Footnote33 Voting patterns in India are unusual compared to other democracies since poor, rural voters are more likely to turn out than affluent urban voters. Overall, elections generate considerable enthusiasm among those at the margins of the state.Footnote34 However, allegations of forced turnout and intimidation by state actors continue to surface periodically, especially in area controlled by anti-system groups.Footnote35 While these are difficult to substantiate, incidents of outright coercion to vote appear to have declined in recent years.Footnote36 Nevertheless, “none of the above” or NOTA voting, where voters cast blank ballots, is more prevalent in rural than in urban constituencies,Footnote37 suggesting that voters there may be more excited about participating than about choosing one of the particular candidates on the ballot. Moreover, clientelism and patronage continue to play an important role in promoting turnout.Footnote38 Without comparative data about how these factors influence turnout in different parts of the country, it is not self-evident that higher turnout necessarily indicates more democracy, even when combined with the competition measure.

Second, focusing on the vote share of the largest party to gauge competition is problematic in the context of multi-party systems where the largest party often does not govern alone. Even if the largest party falls well short of a majority, it may be able to dominate politics by bringing in junior coalition partners. Ziegfeld and Tudor demonstrate that Congress was able to govern for prolonged periods even in the absence of a popular majority.Footnote39 Ultimately, in parliamentary systems where electoral alliances and coalition governments are common, the vote share of the largest party does not tell us enough about the strength of the opposition. Whether the opposition is able to present a viable alternative, however, is a crucial test for how meaningful electoral competition is. Our data for state-level elections between 1985 and 2013 highlight that coalition governments are formed in more than 45% of all electoral periods, making this a serious enough concern to warrant explicit consideration in the construction of a measure of democracy.

Constructing the index: measuring electoral democracy in India

Our analysis of electoral democracy is based on a new dataset of election outcomes, coalition formation, President’s Rule and the coding of news reports about election security across 30 territorial units and 171 elections between 1985 and 2013. It includes India’s 28 states and the union territories of Delhi and Puducherry.Footnote40 Three states – Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Uttarakhand – were created from the territories of other states during the time period we examine. Appendix 1 provides an overview of all assembly elections included in the dataset.

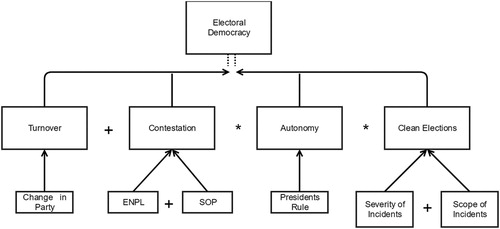

In developing our index, we aim to conceptualize the electoral component of democracy,Footnote41 and to incorporate the insights of previous efforts to measure democracy at the subnational level. Following Przeworski et al, Giraudy conceives of subnational democracy as having three constitutive dimensions: (1) contested elections for the executive and the legislature, (2) alternation in power, and (3) clean elections.Footnote42 Like Giraudy’s, our conceptualization proceeds from the necessary and sufficient concept structure. The basic notion of this approach is to identify the constitutive dimensions, i.e. those conditions that are “necessary and sufficient for something to fit into a category”.Footnote43 Visualizing the constitutive dimensions and specifying their relationship to each other is a useful way to make choices explicit and to ensure concept-measurement consistency.Footnote44 Our conceptualization – visualized in – consists of four dimensions: (1) turnover, (2) contestation, (3) autonomy, and (4) clean elections. Jointly, we argue, these dimensions reflect the electoral component of democracy. Our index thus draws on conceptualizations of democracy that are more restricted than those aiming to capture liberal democracy, which includes civil liberties, respect for minority rights, and the rule of law.Footnote45 In the following paragraphs, we discuss each dimension and its operationalization. We motivate the inclusion and operationalization of the dimensions both theoretically and empirically, underlining our aim to develop an index that can pick up meaningful differences across Indian states.

Turnover

Democracy, as Przeworski has argued, “is a system in which parties lose elections.”Footnote46 Nevertheless, whether turnover should be considered a constitutive dimension of democracy is a topic of some debate. Skeptics have pointed out that the absence of turnover may be indicative of two scenarios; one in which the opposition is weak, thus depriving voters of meaningful alternatives, and one in which voters are simply happy with the incumbent party, and continue to support it. Since the absence of turnover does not tell us which of these two is at work, it constitutes an imprecise measure of democracy.Footnote47 In parliamentary systems, there are generally no term limits, so that parties could conceivably rule for extended periods of time without violating any rules or democratic norms. Nevertheless, as Giraudy argues for Mexico, where there is a history of dominant party rule, a lack of turnover might be a canary in the coalmine for an electoral process that systematically advantages incumbents.Footnote48 Democracy requires not merely that parties win election, but that they are voted out of power without upheaval or reprisals.Footnote49

Tudor and Ziegfeld probe the role of turnover across Indian states.Footnote50 They find that examining whether a non-incumbent party formed an election coalition is insufficient to gauge alternation in power. Specifically, they demonstrate that rule by parties other than Congress at the state-level was often short-lived because they lacked an effective organization, or because Congress undermined them by intervening in local politics. For these reasons, Tudor and Ziegfeld find only a weak correlation between the first time the opposition formed a government and the first time such a government completed a term in office.Footnote51 The latter, they argue, is a more adequate measure of state-level democratization.

Recently, some former opposition parties have become hegemonic in their own right. States like Sikkim, West Bengal and Gujarat have experienced extended periods of non-Congress dominant party rule. The Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF), for example, has been in power since 1994. The party has won five consecutive elections, including one term (2009-2014) without any opposition in the Legislative Assembly. While there had been alternation in power twice during the first two decades after Sikkim became a state in 1975, the opposition began to crumble once the Sikkim Democratic Front defeated Congress in 1994, despite a series of short-lived alliances among opposition parties. In West Bengal, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) has dominated the political arena and it governed for 33 years before losing the 2011 election, making it the longest-governing elected communist government in the world. This period also witnessed the uninterrupted 23-year rule of Chief Minister Jyoti Basu, the longest serving Chief Minister. In Gujarat, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as a dominant force since 1998. Dominant party rule is therefore no longer the prerogative of Congress.

To account for this, we include turnover in our index, but code it conservatively. Specifically, we code turnover as a dummy, where 0 equals the absence of turnover. However, allowing for the possibility that citizens may simply be happy with the governing party, we code turnover as 0 only if the majority party in the governing coalition remains unchanged for more than two consecutive electoral periods. In Sikkim, for instance, the SDF was first elected in 1994, and reelected in 1999. These first two periods are coded as having experienced turnover. When the party is reelected for a third, fourth, and fifth term (2004, 2009, 2014), the turnover dummy drops to 0.

Turnover is connected to the other dimensions with the logical OR (denoted by the symbol +), indicating substitutability, while the remaining three dimensions are connected with the logical AND (denoted by the symbol *) to highlight that each of them is necessary.Footnote52 Substantively this means that even in the absence of turnover, a high score for contestation can still lead to a high score on the index and vice versa.

Contestation

Our second dimension – contestation – captures the degree of competition in the party system. As noted above, turnover only very crudely reflects the strength of the opposition. Our operationalization of contestation draws on two indicators: the effective number of legislative parties and the strength of the opposition in the legislature. Both indicators are calculated at the state-level.Footnote53 We discuss them in turn.

The effective number of parties in the state legislative assembly (ENPL) reflects not only the number of parties but also their relative importance. It is calculated with the formula developed by Laakso and Taagepera on the basis of the number of seats won by each party.Footnote54 In our data, the mean for ENPL is 2.9, which suggests moderate multipartism, but there is significant variation across electoral periods. Strikingly, we observe the lowest possible value (ENPL = 1 for Sikkim 1989, 2009) as well as 31 instances of “extreme pluralism” with more than four effective parties.Footnote55 For ten electoral periods in our data, ENPL takes values higher than five.

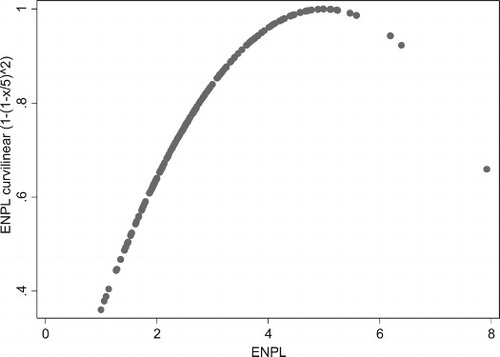

In a parliamentary system, one set of elections determines the composition of the legislature and the executive. In the comparative literature, the effective number of parties is regarded as a bit of a double-edged sword. While very low scores suggest stifled party competition, more is not always better. Specifically, legislative fragmentation has been associated with difficult coalition formation, cabinet instability and lower overall government performance.Footnote56 This literature also indicates that the number of parties interacts with other party system characteristics and contextual factors, so that there is no straightforward way to gauge an optimal number of parties. Conceptually, we take from this literature the insight that there is no linear relationship between the number of parties and democracy. Both extremely low as well as extremely high values for ENPL are problematic, with a sweet spot of robust competition somewhere in between. We therefore include a curvilinear transformation of ENPL in our index where the positive effect of each additional party slowly levels off and ultimately decreases for extreme values higher than five.Footnote57

The second indicator for contestation is the strength of the opposition (SOP), which is calculated as the percentage of seats controlled by parties outside the governing coalition. Empirically, it ranges from 0 (Sikkim) to 53% (Puducherry 1996) with an average of 35%. The correlation between the curvilinear ENPL indicator and SOP is .63, suggesting that – despite some overlap – they pick up different aspects of contestation. The indicators of contestation are treated as substitutable. In , they are thus connected by the logical OR (denoted by the symbol +). To ensure equal weight of both indicators, they are normalized between 0 and 1, and the sum is divided by 2.

Autonomy

Our third dimension reflects whether subnational elections actually decide who governs in a state. Autonomy of local institutions is a pre-condition for subnational democracy, since accountability of elected officials to constituents presupposes the authority to take decisions on their behalf.Footnote58 Autonomy is often only implicit in indices of democracy. Making it explicit is necessary in the case of India because of a constitutional provision, the so-called President’s Rule (PR), which allows the central government to take over the administration of a state. Specifically, Article 356 authorizes the president to dismiss the government of a state and dissolve the legislature in case of “a breakdown of the constitutional machinery”. Even though suspending elected institutions through PR is an emergency power, Article 356 has often been declared “in circumstances where it was perfectly clear that a breakdown in constitutional authority had not taken place”.Footnote59 The provision has been misused to “intimidate recalcitrant state governments”,Footnote60 and to resolve intra-party conflicts.Footnote61 Episodes of PR are thus akin to “interrupted regimes” in cross-national research. This label is generally applied to a regime that qualifies as neither democratic nor authoritarian, because “it is occupied by foreign powers during wartime, or if there is a complete collapse of central authority, or if it undergoes a period of transition during which new polities and institutions are planned”.Footnote62

Between 1950 and 2003 PR was evoked 115 times. Its use has declined since 1994, when a Supreme Court ruling imposed considerable hurdles for the discretional use of Article 356.Footnote63 Nevertheless, non-Congress central governments have continued the practice of trying to use PR for partisan purposes, and the BJP government has resisted efforts to abolish the provision.Footnote64 The threat that PR constitutes to subnational democracy is twofold. First, a provision that had been envisioned by the architects of the constitution as an emergency power has been leveraged to intervene in routine circumstances, such as the loss of a parliamentary majority for the government, or the death or resignation of a chief minister. While such situations create political uncertainty, they do not in and of themselves constitute emergencies. Second, outside interventions introduce an unaccountable external veto player. The imposition of PR, which “used to hang above the heads of India’s regional governments like the sword of Damocles”,Footnote65 constitutes a profound shock to the subnational regime. With the imposition of PR, political majorities and party dynamics tend to shift, so that even the end of PR does not imply the return to the status quo ante. This, arguable, was the whole point of placing the state under central rule.

While PR is specific to India, political autonomy is applicable to the conceptualization of subnational democracy more broadly. Without autonomy, subnational democracy is hollow, even if voters are allowed to go through the motions of electing representatives. Akin to the “interrupted regimes” classification in cross-national research, a state under PR ceases to be a democracy, since democratic rules and procedures no longer determine who governs.

President’s Rule can be relatively brief or it can last for multiple years. An extended period of 2,455 days in Jammu & Kashmir between 1987 and 1996 constitutes the most extreme case in our data. We consider the suspension of elected institutions such a severe violation of democracy that our autonomy dummy takes a value of 0 if President’s Rule was evoked at any point during the electoral period. Overall, we document 38 instances of PR across states. The majority (21 instances or 59%) occurred during the first decade under investigation (1985-94).

Clean elections

Democracy requires “the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules” so that the outcome of the democratic process is uncertain.Footnote66 To avoid this institutionalized uncertainty, actors may be tempted to rig the process to avoid the costs of losing. Free and fair elections are therefore an essential component of democracy. The logistics inherent in organizing such elections in India are hard to overstate. The electorate grew from over 370 million in 1984 to more than 787 million by 2014.Footnote67 Three states now have populations of more than 100 million, making subnational elections there larger undertakings than national elections in most countries. The overwhelming majority of voters live in rural areas, and illiteracy and poverty are widespread. The Election Commission of India (ECI), an autonomous constitutional body, is in charge of organizing national and state elections. The architects of India’s constitution believed that centralized election management would provide better protections against electoral malpractice and political interference than state-level commissions.Footnote68 Since Independence, the ECI has earned a reputation of professionalism, and has become one of the most highly regarded institutions.Footnote69

Since the ECI’s own staff is fairly small (>300 people in the early 2000s), it relies primarily on employees deputized from state and local governments.Footnote70 In large states polling is often spread out over multiple phases so that security forces and poll workers can move around. Despite its commitment to impartial election management, logistics pose considerable challenges to the ECI. In addition to staffing polling booths, clean elections require the ability to head off disruptions of polling. Non-state armed actors, such as the Naxalite movement, have at times called for a boycott of elections, and sought to enforce it with voter intimidation, including bomb blasts at polling stations and killings of poll workers or candidates. Booth capturing, or the armed takeover of polling places to stuff ballot boxes, constitutes another threat to the integrity of elections.Footnote71 There are several instances where the ECI postponed polling either completely or partially because of security.Footnote72 Over the last decade, technological and organizational innovations spearheaded by the ECI, such as vulnerability mapping and the use of electronic voting machines, have contributed to reducing electoral malpractice.

Capturing whether the exercise and tabulation of the vote was fair is crucial particularly for the first elections in our dataset, but no comprehensive state-level data are available.Footnote73 We therefore created an original dataset of election security based on news reports about assembly elections in the Times of India (TOI). For each election, we code reports of ballot fraud, especially booth capturing, violence at the polls, and voter intimidation (including boycotts by armed groups). While these reported irregularities reflect a narrow interpretation of electoral integrity, especially violence is often associated with other forms of electoral manipulation, so that they can be expected to constitute an adequate proxy.Footnote74 The unit of analysis is event-election-constituency.Footnote75

To turn news reports into an indicator of clean elections, we focus on two aspects: (1) the severity of incidents reported, and (2) how widespread reported problems were. Isolated incidents occur in many elections, but they normally do not raise concerns about the overall process. In our data, at least one incident is reported for 106 elections (62%). In operationalizing clean elections, we aim to distinguish incidents from systematic problems.Footnote76 Since violence, especially lethal violence, tends to be reported most consistently,Footnote77 we capture the severity of incidents with the number of deaths (logged) due to election violence. The number of fatalities ranges from 0 (65% of elections) to 112 (Tripura 1988). In the first decade under study (1985-94) 654 deaths are reported compared to 99 in the elections between 2005 and 2014. To gauge how widespread problems were, we examine in which percentage of constituencies incidents were reported. Here, we include not just fatalities, but also reports of booth capture, non-lethal violence and voter intimidation. This variable ranges from 0 (65 elections or 38%) to 100 (6 elections or 3.5%). Both indicators are treated as substitutable, and for each the scale is reversed so that higher scores indicate more security. To ensure equal weight both indicators are normalized, and the sum is divided by 2.

Subnational democracy in India: findings and implications

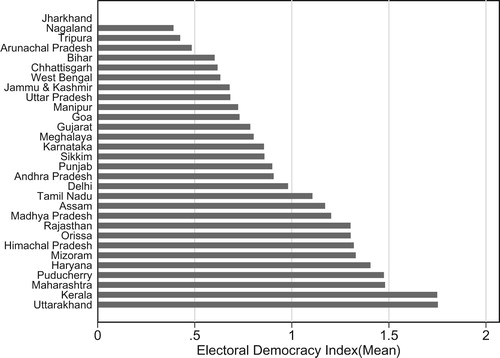

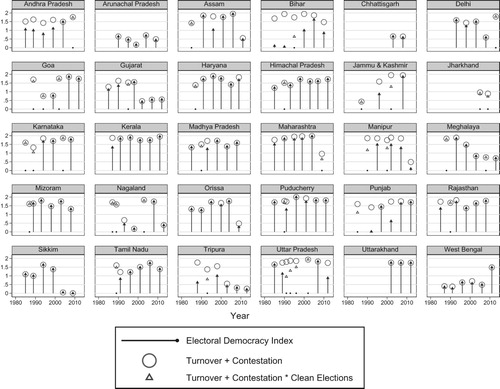

Combining the indicators for constitutive dimensions allows us to examine democracy empirically, with higher index scores indicating better performance on our continuous measure. provides a quick summary of the data, and shows the average score on the index per state for the whole period. The frontrunners are Uttarakhand, which was founded in 2000, and Kerala, which is widely regarded as one of the most successful examples of subnational democracy.Footnote78 At the other end of the spectrum, we find states in the North East, specifically the new state of Jharkhand, and the peripheral states of Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, and Tripura. To examine the state-specific patterns more closely, displays index scores per election.

Conceptually, low scores on the index reflect deviations from democracy. One advantage of our index is transparency about the influence of constitutive dimensions, which allows other scholars to scrutinize our measurement and to revise it where they disagree with our conceptualization.Footnote79 To spell out how each dimension influences the index reports three scores: (1) turnover and contestation, (2) turnover and contestation with the clean elections multiplier, and (3) the full index, which drops to zero in the case of President’s Rule.

Identifying threats to subnational democracy in India

A comparison of index scores per election illustrates how President’s Rule disrupts electoral politics. Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Mizoram and Uttar Pradesh have high scores on the electoral dimensions throughout the period, but instances of PR disrupt that pattern. Similarly, Karnataka, Mizoram, Punjab and Rajasthan generally do well on the electoral dimension, but experience President’s Rule. Substantively, a score of 0 indicates that it does not make sense to classify the regime as more or less democratic on the index, since election do not determine who governs.

Low scores on the full index that are unrelated to PR indicate variation across states in the level of electoral democracy. This is the case in Gujarat after 2002, in Nagaland in 1993, 1998 and 2013, in Orissa after 2009, in Sikkim after 2004, in Tripura after 2003 and in West Bengal until 2011.

How heavily do violations of the clean elections dimension weigh on the index? If the triangle is below the circle, this indicates that the overall score is lower because of problems with election security. Instances of this can be found in Andhra Pradesh, Manipur and Uttar Pradesh. The most striking case is Bihar, where widespread and systematic problems were reported for multiple elections. The good news here is that election management has improved considerably.

Jammu & Kashmir has long been considered an authoritarian enclave in democratic India,Footnote80 and observers have lamented the suppression of electoral competition in the state.Footnote81 In our data, the score based on contestation and turnover for the first electoral period (1987) is indeed extremely low. The state is then placed under President’s Rule for more than six years, indicating an interrupted regime. In terms of electoral dynamics, things seem to improve after 1996, when elections are held again. Nevertheless, irregularities are reported during these elections and electoral politics continue to be disrupted by PR after scores for turnover and contestation pick up. While previous studies had already identified Jammu and Kashmir as undemocratic, our data reveal that threats to subnational democracy come from multiple directions. This is not only an instance of dominant party rule with limited electoral competition locally,Footnote82 but also one where the center threatens elected institutions, and where elections have systematic problems.

The comparison of scores across constitutive dimensions highlights the need to distinguish and theorize different types of threats to subnational democracy. First, there are instances in which low scores for turnover and contestation signal problems with party competition. These dominant party regimes resemble those theorized in Latin America, where incumbents distort the playing field to systematically disadvantage challengers.Footnote83 For such regimes, theorization of regime characteristics has focused on unit-specific factors, such as the local bureaucracy,Footnote84 or legacies of economic development,Footnote85 and the relationship with the center.Footnote86

Second, there are instances where threats to democracy come from the center as states are placed under President’s Rule. This highlights the need to more explicitly theorize how and why central governments intervene in local politics. Previous scholarship has shown that the survival of undemocratic elites depends on successfully managing the vertical relationship with the center. Gibson posits that “central governments intervene regularly and substantively in the affairs of provincial governments”,Footnote87 but the scope and constitutional provisions for such interventions vary across countries. The case of India highlights a new dimension of this vertical relationship, namely one where the center interrupts subnational regimes in parts of the territory. Boundary control has often been theorized as a defensive strategy pursued by undemocratic regimes to ward off intervention from the democratic center.Footnote88 Subnational democracies in India may similarly need to engage in boundary control to head off intervention by a center controlled by political rivals. For the literature on subnational regimes, this suggests that a closer dialogue with the literature on subnational democracy in authoritarian regimes, especially Russia, may be fruitful to identify similarities and differences regarding the causes and consequences of interventions.Footnote89

Third, there are instances where low scores on the index are driven by systematic problems with election security. Overall, problems during elections appear to be prevalent especially where turnover and contestation are fairly high, so that elections produce uncertainty about future governance. Assam (1996), Bihar (1985, 1990, 1995), and Uttar Pradesh (1991, 1993) fit into this category. In Manipur (2012) and Nagaland (1993) a low score for electoral dynamics drops even further because of problems with the elections. Both of these elections were characterized by anti-system violence as the locally dominant Congress party became the target of insurgent groups boycotting the elections. In Manipur our database records multiple bomb explosions at Congress party offices, the homes of candidates and polling stations. There are also reports of threats against Congress campaign workers. Here anti-system violence, rather than manipulation by incumbents, undermines subnational institutions. Whereas President’s Rule can be conceptualized as “a vertical threat” to democracy, anti-system violence can be understood as a “horizontal threat”.Footnote90 The existence of similar threats in Mexico highlights the need to theorize challenges to subnational democracy from actors outside the political system more explicitly,Footnote91 especially since such threats are often localized and do not affect all of the national territory.

Temporal trends

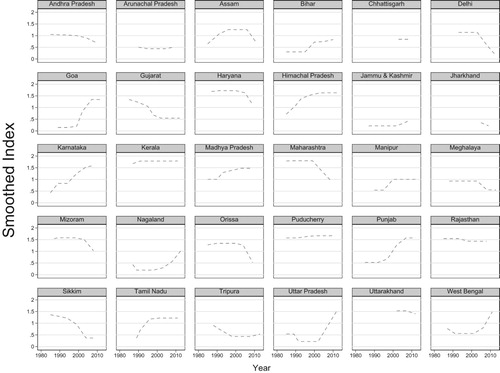

Since our index is sensitive to shocks in each of the constituent dimensions, a nonlinear robust smoother has been applied to reveal underlying patterns in scores on the index and to examine trajectories during the period under study.

In , the trend line for Arunachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Kerala, Puducherry, and Rajasthan is fairly flat, though the level of democracy varies significantly between them. Arunachal Pradesh performs poorly throughout the time period whereas Kerala is a continual front-runner. Among the states that show a more dynamic development, both upward and downward trends can be observed. Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Punjab and West Bengal exhibit an upward trend, and Gujarat, Meghalaya, Sikkim and Tripura move in the opposite direction. Importantly, the latter are not holdouts from a previous authoritarian regime, as many other cases studied in the literature on subnational regimes thus far. Comparatively, we might better conceptualize them as “backsliding”,Footnote92 indicating a need to theorize not just democratization or authoritarian persistence, but also democratic decline in subnational regimes.

In Tudor and Ziegfeld’s analysis, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal are identified as early democratizers, i.e. states in which a non-Congress government was able to complete a full term in office comparatively early.Footnote93 After alternation, however, the paths of these states diverged. Kerala clearly kept its frontrunner status, and Tamil Nadu also performs well. West Bengal, however, entered a renewed period of dominant party rule. So in hindsight, the case of West Bengal might be better understood as one where one hegemonic regime is replaced by another. Geddes et al. show that transitions from one undemocratic regime to another remain poorly understood.Footnote94 The cross-national literature has tended to focus on transitions to democracy or democratic breakdown instead. To the literature on subnational politics, insights from India indicate that the loss of power by one hegemonic party might not always lead to more competitive politics

Conclusion

This paper introduces new disaggregate data on subnational democracy in India, and leverages this data to map subnational democracy across states, and to trace regime trajectories over time. Our analysis shows variation in all constitutive dimensions. Subnational democracy is challenged by multiple directions, including the central government and non-state armed actors. While scholarship on subnational regimes has highlighted that within-country variation in democracy is widespread, the empirical focus has been on new democracies. The Indian case broadens the universe of cases for the comparative literature, and our analysis has revealed empirical patterns not yet theorized. The inclusion of India therefore strengthens the emerging research agenda on subnational regimes.

Since the data are disaggregated by election and constitutive dimension scholars interested in using the data can scrutinize our measurement decisions, and re-aggregate it in a way that best suits their research needs. Those interested in the long-term consequences of subnational democracy, for instance, may find the smoothed measure of temporal trends more relevant than scores per electoral period. Students of electoral dynamics may want to use only the data on party system characteristics and governing coalitions, while leaving out indicators for President’s Rule or clean elections. Beyond providing novel tools for answering existing questions, the data for constitutive dimensions highlights variation across states and over time that invites further analysis. Our indicator for clean elections, for example, shows that systematic problems with elections persist in some states over a series of elections, whereas they remain isolated to just one or two elections in others, and are entirely absent altogether in the rest. What explains such differences in election management, since all elections are organized by the same institution? Does the party identity of the incumbent government matter? Or the configuration of parties in the state assembly? In light of the scale of subnational elections in India, it is crucial for scholars of democracy to develop a better understanding of what determines regime outcomes. We hope that the index and data will constitute a resource for scholars going forward.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jos Bartman http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3635-3778

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Imke Harbers

Imke Harbers is associate professor of Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. Her research focuses on subnational politics, state capacity and state-society interactions, with a specific emphasis on the territorial reach of the state. Her work has appeared, or is forthcoming in, Political Science Research and Methods, Political Analysis, and Comparative Political Studies, among others. She has held visiting positions at the University of California, San Diego, and her current research is funded by a Marie Curie Fellowship from the European Commission.

Jos Bartman

Jos Bartman is a PhD candidate in the Political Science Department of the University of Amsterdam. As part of the ERC-funded “Authoritarianism in a Global Age” project, he investigates how subnational undemocratic regimes use repression. Other primary research interests include subnational patterns of electoral competitiveness and subnational patterns of repression and human rights violations. He recently also published the article Murder in ‘Mexico; are journalists victims of general violence or targeted political violence?’ (2018) in Democratization.

Enrike van Wingerden

Enrike van Wingerden is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her doctoral research theorizes how seemingly localized political struggles are enacted transnationally. She also convenes the seminar series in International Political Sociology at the University of London. At the University of Amsterdam, she contributes to research projects on global, transnational, and subnational modes of power. Her co-authored article “A ‘distributive regime’: Rethinking global migration control” (2019) recently appeared in Political Geography.

Notes

1 Times of India, “Electoral Violence.”

2 Notable exceptions are Heller, “Degrees of Democracy”; Beer and Mitchell, “Comparing Nations and States”; Lankina and Getachew, “Mission or Empire”; Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization.”

3 Goertz, “Social Science Concepts”; Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats.

4 Replication materials and the dataset are available via Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/V0AD8L).

5 Schedler, “Criminal Subversion.”

6 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding.”

7 Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization.”

8 Snyder, “Scaling Down”; Sinha, “Scaling Up”; Giraudy et al. Inside Countries.

9 Dahl, Polyarchy, 12.

10 E.g. O’Donnell, Counterpoints; Gervasoni “A Rentier Theory”; Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats.

11 McMann 2006, “Economic Autonomy and Democracy”; Lankina and Getachew, “A Geographic Incremental Theory”; Libman, “Subnational Political Regimes”; Ross and Panov, “The Range and Limitation of Sub-National Regime Variations.”

12 Gibson, Boundary Control.

13 McMann, “Measuring Subnational Democracy.”

14 Cornelius “Blind spots”; Lawson, “Mexico’s Unfinished Transition.”

15 Gibson, Boundary Control; Gervasoni “A Rentier Theory.”

16 Behrend, “The Unevenness of Democracy.”

17 McMann, Economic Autonomy and Democracy.

18 Lankina and Libman, “Soviet Legacies.”

19 Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats.

20 Lipset, “Some Social Requisites,” 71.

21 Vanhanen, “A New Dataset,” 252; Lindberg et al, “V-Dem.”

22 Giraudy, “Democrats and Autocrats,” 35.

23 Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism.

24 Geddes et al, “Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions,” 314.

25 Snyder, “Scaling Down”; Tillin, “National and Subnational Comparative Politics.”

26 Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization.”; Ziegfeld and Tudor, “How Opposition Parties Sustain Single-Party Dominance.”

27 Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization,” 56.

28 Vanhanen, “A New Dataset.”

29 Beer and Mitchell, “Comparing Nations.”

30 Lankina and Getachew, “Mission or Empire.”

31 Vanhanen, “A New Dataset,” 262.

32 Lindberg et al, “V-Dem.”

33 Doorenspleet, “Reassessing the Three Waves of Democratization.”

34 Ahuja and Chhibber, “Why the Poor Vote”; Banerjee, Why India Votes?

35 Spokesperson, “On the Election Boycott Tactic.”

36 Ahuja and Chhibber, “Why the Poor Vote.”

37 Goel, “Voting from the Margins.”

38 Chandra, Patronage, Democracy, and Ethnic Politics.

39 Ziegfeld and Tudor, “How Opposition Parties Sustain Single-Party Dominance”; Chhibber and Nooruddin, “Do Party Systems Count?” 162.

40 India has seven union territories. Of these only Delhi and Puducherry have locally elected governments.

41 Lindberg et al, “V-Dem.”

42 Przeworski et al, Democracy and Development; Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats.

43 Goertz, Social Science Concepts, 7.

44 Goertz, Social Science Concepts.

45 Doorenspleet, “Reassessing the Three Waves of Democratization”; Lindberg et al., “V-Dem.”

46 Przeworski, Democracy and the Market, 10.

47 Mainwaring et al, “Classifying Political Regimes.”

48 Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats.

49 Przeworski, Democracy and the Market.

50 Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization.”

51 Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization,” 57.

52 Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats, 179–83.

53 Note that even a highly competitive state-wide party system may contain constituencies where the same party wins by large margins in election after election. Generally, the effective number of electoral parties at the constituency level is lower than at the state- or national-level, as shown in Ziegfeld, “Electoral Systems in Context,” 14–16; Ziegfeld, “Are Higher-Magnitude Electoral Districts Always Better.” Our focus here is on the state-level since we are examining whether or not parties are able to dominate statewide.

54 Independents are treated as individual parties, rather than as a block. Coding independents as a block would suggest cohesiveness among them, and thus most likely underestimate ENPL. However, there are instances where candidates that formally ran as independents actually constitute a political group. After the 1985 election in Assam, for instance, during which independents garnered 92 of 126 seats, they formed a government under the banner of the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP). The 1985 elections were the outcome of a pact between the AGP and Rajiv Gandhi after the highly contentious elections of 1983. In this instance, we then do code independents as a group. We provide detailed information about our decisions in the codebook. Laakso and Taagepera “Effective Number of Parties.”

55 Mainwaring & Scully, Building Democratic Institutions 32.

56 E.g. Blondel, Comparative Government Introduction; Laver, “Models of Government Formation”; Chhibber and Nooruddin, “Do Party Systems Count?”

57 The formula used to calculate the transformation is 1 – (1 – x/5)^2. The correlation between the original variable and the transformation is .87, suggesting that the transformation influences the ranking of states only at the margins.

58 Bland, “Considering Local Democratic Transition.”

59 Hewitt & Rai, “Parliament,” 39.

60 Metcalf & Metcalf, “A Concise History of Modern India,” 232.

61 Kochanek and Hardgrave, India: Government and Politics in a Developing Nation, 80–4; Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization.”

62 Doorenspleet, “Reassessing the Three Waves of Democratization,” 389.

63 Kochanek and Hardgrave, India: Government and Politics, 81–3.

64 Sharma and Swenden, “Modi-fying Indian Federalism?”

65 Mitra and Pehl, “Federalism,” 50.

66 Przeworski, Democracy and the Market, 14.

67 IDEA Voter Turnout Database; https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout.

68 Gilmartin and Moog “Introduction”, 138; Mexico, by contrast, initially decentralized authority over state-level elections to the states. After it became apparent that these state-level bodies varied in their degree of political independence and professionalism, election management was centralized as part of the 2014 electoral reform (see Harbers and Ingram, “On the Engineerability of Political Parties” and “Democratic Institutions”).

69 Rudolph and Rudolph, “New Dimensions in Indian Democracy.”

70 Sridharan and Vaishnav “Election Commission,” 424.

71 Verma, “Policing Elections”; Berenschot, “On the Usefulness of Goondas.”

72 Sridharan and Vaishnav “Election Commission.”

73 The “Election Integrity Project” has conducted an expert survey to evaluate the 2015–2016 assembly elections in five states (Assam, Bihar, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Bengal), but beyond this pilot study no systematic data are available (see Mahmood and Ganguli, “The Performance of Indian States”).

74 Staniland, “Violence and Democracy,” 105.

75 Information about the extraction procedure and coding decisions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

76 See Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism, 366.

77 Franzosi, From Words to Numbers.

78 Heller, “Degrees of Democracy”; Lankina and Getachew, “Mission or Empire.”

79 Niedzwiecki et al, “The RAI Travels to Latin America.”

80 Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization.”

81 Ganguley “Explaining the Kashmir Insurgency.”

82 See Dahl, Polyarchy, 13.

83 Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats; Behrend, “The Unevenness of Democracy.”

84 Durazo Herrman “Neo-patrimonialism.”

85 McMann, Economic Autonomy and Democracy; Lankina and Libman, “Soviet Legacies of Economic Development.”

86 Gervasoni “A Rentier Theory.”

87 Gibson, Boundary Control, 12.

88 Gibson, Boundary Control.

89 Golosov, “The Regional Roots of Electoral Authoritarianism”; Ross and Panov, “The Range and Limitation of Sub-National Regime Variations.”

90 Schedler, “Criminal Subversion.”

91 See Ley, “To Vote or Not to Vote.”

92 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding.”

93 Tudor and Ziegfeld, “Subnational Democratization,” 50.

94 Geddes et al, “Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions.”

Bibliography

- Ahuja, Amit, and Pradeep Chhibber. “Why the Poor Vote in India: “If I Don’t Vote, I am Dead to the State.” Studies in Comparative International Development 47, no. 4 (2012): 389–410.

- Banerjee, Mukulika. Why India Votes? New Delhi: Routledge India, 2017.

- Beer, Caroline, and Neil J. Mitchell. “Comparing Nations and States: Human Rights and Democracy in India.” Comparative Political Studies 39, no. 8 (2006): 996–1018.

- Behrend, Jacqueline. “The Unevenness of Democracy at the Subnational Level: Provincial Closed Games in Argentina.” Latin American Research Review (2011): 150–176.

- Berenschot, Ward. “On the Usefulness of Goondas in Indian Politics: ‘Moneypower’ and ‘Musclepower’ in a Gujarati Locality.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 34, no. 2 (2011): 255–275.

- Bermeo, Nancy. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19.

- Bland, Gary. “Considering Local Democratic Transition in Latin America.” Journal of Politics in Latin America 3, no. 1 (2011): 65–98.

- Blondel, Jean. Comparative Government Introduction. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969.

- Chandra, Kanchan. Patronage, Democracy, and Ethnic Politics in India. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2013.

- Chhibber, Pradeep, and Irfan Nooruddin. “Do Party Systems Count? The Number of Parties and Government Performance in the Indian States.” Comparative Political Studies 37, no. 2 (2004): 152–187.

- Cornelius, Wayne A. “Blind Spots in Democratization: Sub-National Politics as a Constraint on Mexico's Transition.” Democratization 7, no. 3 (2000): 117–132.

- Dahl, Robert Alan. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Doorenspleet, Renske. “Reassessing the Three Waves of Democratization.” World Politics 52, no. 3 (2000): 384–406.

- Durazo Herrmann, Julián. “Neo-patrimonialism and Subnational Authoritarianism in Mexico. The Case of Oaxaca.” Journal of Politics in Latin America 2, no. 2 (2010): 85–112.

- Franzosi, Roberto, and Franzosi Roberto. From Words to Numbers: Narrative, Data, and Social Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Ganguly, Šumit. “Explaining the Kashmir Insurgency: Political Mobilization and Institutional Decay.” International Security 21, no. 2 (1996): 76–107.

- Geddes, Barbara, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz. “Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions: A New Data Set.” Perspectives on Politics 12, no. 2 (2014): 313–331.

- Gervasoni, Carlos. “A Rentier Theory of Subnational Regimes: Fiscal Federalism, Democracy, and Authoritarianism in the Argentine Provinces.” World Politics 62, no. 2 (2010): 302–340.

- Gibson, Edward L. Boundary Control: Subnational Authoritarianism in Federal Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Gilmartin, David, and Robert Moog. ““Introduction to ‘Election Law in India’.” Election Law Journal 11, no. 2 (2012): 136–148.

- Giraudy, Agustina. Democrats and Autocrats: Pathways of Subnational Undemocratic Regime Continuity Within Democratic Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Giraudy, Agustina, Eduardo Moncada, and Richard Snyder. Inside Countries: Subnational Research in Comparative Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Giraudy, Agustina. “Varieties of Subnational Undemocratic Regimes: Evidence From Argentina and Mexico.” Studies in Comparative International Development 48, no. 1 (2013): 51–80.

- Goel, Garima. “Voting from the Margins: Patterns of ‘None of the above’ Voting in India.” Economic and Political Weekly 53, no. 33 (2018): 55–62.

- Goertz, Gary. Social Science Concepts: A User's Guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Golosov, Grigorii V. “The Regional Roots of Electoral Authoritarianism in Russia.” Europe-Asia Studies 63, no. 4 (2011): 623–639.

- Harbers, Imke, and Matthew C. Ingram. “On the Engineerability of Political Parties: Evidence From Mexico.” In Regulating Political Parties: European Democracies in Comparative Perspective, edited by Ingrid van Biezen and Hans-Martien ten Napel, 253–277. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2014.

- Harbers, Imke, and Matthew C. Ingram. “Democratic Institutions Beyond the Nation State: Measuring Institutional Dissimilarity in Federal Countries.” Government and Opposition 49, no. 1 (2014): 24–46.

- Heller, Patrick. “Degrees of Democracy: Some Comparative Lessons from India.” World Politics 52, no. 4 (2000): 484–519.

- Hewitt, Vernon, and Shirin Rai. “Parliament.” In The Oxford Companion to Politics in India, edited by Niraja Gopal Jayal and Pratap Bhanu Mehta, 28–42. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Kochanek, Stanley A., and Robert L. Hardgrave. India: Government and Politics in a Developing Nation. Boston: Thomson Wadsworth, 2007.

- Laakso, Markku, and Rein Taagepera. “‘Effective’ Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 12, no. 1 (1979): 3–27.

- Lankina, Tomila V., and Lullit Getachew. “A Geographic Incremental Theory of Democratization: Territory, Aid, and Democracy in Postcommunist Regions.” World Politics 58, no. 4 (2006): 536–582.

- Lankina, Tomila V., and Alexander Libman. “Soviet Legacies of Economic Development, Oligarchic Rule and Electoral Quality in Eastern Europe’s Partial Democracies: The Case of Ukraine.” Comparative Politics (forthcoming).

- Lankina, Tomila, and Lullit Getachew. “Mission or Empire, Word or Sword? The Human Capital Legacy in Postcolonial Democratic Development.” American Journal of Political Science 56, no. 2 (2012): 465–483.

- Laver, Michael. “Models of Government Formation.” Annual Review of Political Science 1, no. 1 (1998): 1–25.

- Lawson, Chappell. “Mexico's Unfinished Transition: Democratization and Authoritarian Enclaves in Mexico.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 16, no. 2 (2000): 267–287.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Ley, Sandra. “To Vote or Not to Vote: How Criminal Violence Shapes Electoral Participation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62, no. 9 (2018): 1963–1990.

- Libman, Alexander. “Subnational Political Regimes and Formal Economic Regulation: Evidence From Russian Regions.” Regional & Federal Studies 27, no. 2 (2017): 127–151.

- Lindberg, Staffan I., Michael Coppedge, John Gerring, and Jan Teorell. “V-Dem: A New Way to Measure Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 25, no. 3 (2014): 159–169.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review 53, no. 1 (1959): 69–105.

- Mahmood, Zaad, and Rahul Ganguli. “The Performance of Indian States in Electoral Integrity.” Electoral Integrity Project, January 2, 2017. https://www.electoralintegrityproject.com/international-blogs/2017/1/2/the-performance-of-indian-states-in-electoral-integrity.

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Timothy Scully. Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Mainwaring, Scott, Daniel Brinks, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán. “Classifying Political Regimes in Latin America, 1945-1999.” Studies in Comparative International Development 36, no. 1 (2001): 37–65.

- McMann, Kelly M. “Measuring Subnational Democracy: Toward Improved Regime Typologies and Theories of Regime Change.” Democratization 25, no. 1 (2018): 19–37.

- McMann, Kelly M. Economic Autonomy and Democracy: Hybrid Regimes in Russia and Kyrgyzstan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Metcalf, Barbara D., and Thomas R. Metcalf. A Concise History of Modern India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Mitra, Subrata, and Malte Pehl. “Federalism.” In The Oxford Companion to Politics in India, edited by Niraja Gopal Jayal and Pratap Bhanu Mehta, 43–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Niedzwiecki, Sara, Sandra Chapman Osterkatz, Liesbet Hooghe, and Gary Marks. “The RAI Travels to Latin America: Measuring Regional Authority Under Regime Change.” Regional & Federal Studies (2018): 1–26.

- O’Donnell, Guillermo A. Counterpoints: Selected Essays on Authoritarianism and Democratization. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999.

- Przeworski, Adam. Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Przeworski, Adam, Michael E. Alvarez, Jose Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Ross, Cameron, and Petr Panov. “The Range and Limitation of Sub-National Regime Variations Under Electoral Authoritarianism: The Case of Russia.” Regional & Federal Studies (2018): 1–26.

- Rudolph, Susanne Hoeber, and Lloyd I. Rudolph. “New Dimensions in Indian Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 1 (2002): 52–66.

- Schedler, Andreas. “The Criminal Subversion of Mexican Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 25, no. 1 (2014): 5–18.

- Sharma, Chanchal Kumar, and Wilfried Swenden. “Modi-fying Indian Federalism? Center–State Relations under Modi’s Tenure as Prime Minister.” Indian Politics & Policy Journal 1, no. 1 (2018): 51–81.

- Sinha, Aseema. “Scaling Up: Beyond the Subnational Comparative Method for India.” Studies in Indian Politics 3, no. 1 (2015): 128–133.

- Snyder, Richard. “Scaling Down: The Subnational Comparative Method.” Studies in Comparative International Development 36, no. 1 (2001): 93–110.

- Spokesperson. “On the Election Boycott Tactic of the Maoists.” Economic and Political Weekly 44, no. 38 (2009): 73–77.

- Sridharan, Eswaran, and Milan Vaishnav. “Election Commission of India.” Rethinking Public Institutions in India (2017): 417–463.

- Staniland, Paul. “Violence and Democracy.” Comparative Politics 47, no. 1 (2014): 99–118.

- Tillin, Louise. “National and Subnational Comparative Politics: Why, What and How.” Studies in Indian Politics 1, no. 2 (2013): 235–240.

- Times of India. “Electoral Violence Endemic in Bihar.” March 19, 1990.

- Tudor, Maya, and Adam Ziegfeld. “Subnational Democratization in India: The Role of Colonial Competition and Central Intervention.” In Illiberal Practices: Territorial Variance Within Large Federal Democracies, edited by Jacqueline Behrend and Laurence Whitehead, 49–88. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

- Vanhanen, Tatu. “A New Dataset for Measuring Democracy, 1810–1998.” Journal of Peace Research 37, no. 2 (2000): 251–265.

- Verma, Arvind. “Policing Elections in India.” India Review 4, no. 3–4 (2005): 354–376.

- Ziegfeld, Adam. “Are Higher-Magnitude Electoral Districts Always Better for Small Parties?” Electoral Studies 32, no. 1 (2013): 63–77.

- Ziegfeld, Adam. “Electoral Systems in Context: India.” The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190258658.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190258658-e-41.

- Ziegfeld, Adam, and Maya Tudor. “How Opposition Parties Sustain Single-Party Dominance: Lessons From India.” Party Politics 23, no. 3 (2017): 262–273.