ABSTRACT

The international dimension of authoritarian resilience is receiving increased attention by scholars of comparative politics and international relations alike. Research suggests that autocratic states exploit regionalism to boost domestic regime security. This article explains how membership in regional organizations can help to strengthen survival chances of autocratic incumbent elites. It argues that membership provides additional material, informational, and ideational resources to autocratic incumbents that can be used to boost domestic survival strategies vis-à-vis internal and external challengers. The article provides qualitative case-based evidence to show how autocratic incumbents in Zimbabwe, China, and Bahrain have benefited from the involvement of regional organizations during moments of political instability to strengthen legitimation, repression, co-optation, and international appeasement strategies. The article thereby provides the first encompassing explanation linking regionalism and authoritarian survival politics that is applicable across regions and different types of authoritarian regimes.

Introduction

Regionalism has developed into a popular form of international cooperation across the globe to regulate relations amongst neighbouring states. In contrast to regional organizations (ROs) in the Global North that tend to produce democratizing effects by locking-in liberal reformsFootnote1, ROs in the Global South however often seem to exhibit a dark side because of their propensity to stabilize authoritarian rule. As the regime-boosting literature has argued, this is because authoritarian regimes exploit RO membership to further their own elite interests in regime security.Footnote2

Processes of regime-boosting regionalism have been studied in multiple regions. While early literature investigated unintended stabilizing effects from foreign aidFootnote3 or sanctionsFootnote4 and consequences of competing influences from both democratic and autocratic actors on authoritarian resilienceFootnote5, recently scholars started to explore consequences of cooperation between authoritarian regimes.Footnote6 Comparative politics literature mostly focused on the efforts of autocratic powers such as China, Russia, and Venezuela in intentionally shaping and sustaining autocracy in their immediate neighborhoodFootnote7 with ROs as one possible instrument of influence.Footnote8 Beyond ROs as a tool of powerful states, regionalism scholars have investigated how ROs have been employed to boost legitimation through “shadow election monitoring”Footnote9 or regional identity discourses,Footnote10 to boost rent-seeking capacities,Footnote11 for purposes of cross-border policing and intelligence-sharing,Footnote12 or to deal with negative externalities through international signalling.Footnote13

While previous literature has made important contributions to understand the regional dimension of authoritarian resilience, it often fails to clearly connect regional dynamics and domestic politics to theorize and empirically test how RO membership can actually increase the likelihood of incumbent survival. While this regional-domestic link has been amply theorized within the study of EuropeanizationFootnote14 and EU democracy promotion and diffusion abroadFootnote15, this is still lacking with regard to regionalism and domestic politics in non-democratic regimes. In a recent contribution, Libman and ObydenkovaFootnote16 for instance discuss how economic redistribution and legitimation work in different ROs in Eurasia, the Gulf, and Latin America, but their work does not address how both interact with domestic politics. Kneuer et al.Footnote17 compare how ROs can serve as “transmission belts” for regional powers to disseminate material support and authoritarian ideas in order to stabilize their rule and raise authoritarian legitimacy. However, both their theoretical framework and case studies focus on potential motives of regional powers to engage in regionalism and the tools at their disposal to influence other RO member states, not on how this affects regime stability. While the regional-domestic link is sometimes explored in more detail in research focusing on single regions and ROs,Footnote18 there is little comparative work that systematically theorizes and assesses to what extent findings are transferable. Finally, existing research also largely relies on the realist assumption that international organizations are merely tools of powerful member states,Footnote19 thereby negating the fact that ROs vary significantly with regard to authority and agencyFootnote20 and can affect the behaviour of domestic actors independently of power politics.Footnote21

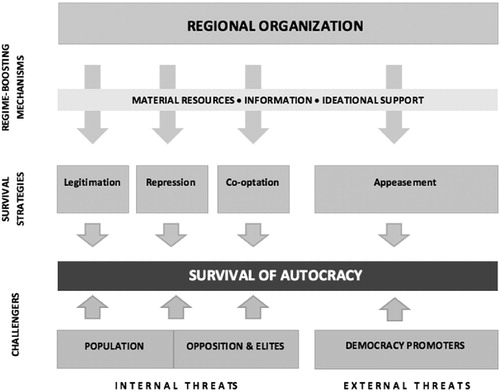

To contribute to these debates, this article asks how RO membership can help authoritarian regimes to strengthen domestic survival politics and thereby increase the chances of incumbent survival. It integrates existing literature on regime-boosting and combines it with literature on authoritarian stability and survival to both develop an analytical framework that conceptualizes the regional-domestic link and to explore this link in three novel comparative case studies. Domestically, authoritarian regimes are characterized by survival politics directed at mitigating threats from challenging actors.Footnote22 While research has mostly focused on conceptualizing strategies directed at domestic challengers such as preventing mass uprisings and political dissent through legitimationFootnote23 and repressionFootnote24 or averting intra-elite splits through co-optationFootnote25, I expand this taxonomy by also including strategies aimed to counter external challenges from democracy promoters through international appeasement.Footnote26 Based on a rational institutionalist approach, I furthermore argue that ROs represent opportunity structures that affect the power distribution between domestic actors by providing additional resources to some and thereby severely constraining others. To the extent that autocratic incumbents have the capacity to exploit opportunities provided by RO membership and avoid constraints, they can strengthen each respective survival strategy through additional material, informational, and ideational resources. While domestic factors certainly remain decisive to explain variation in regime outcomes, RO membership can help to increas the likelihood of incumbent survival through executive empowerment vis-à-vis challenging actors, particularly during moments of political upheaval.Footnote27

The proposed analytical framework offers four major advantages. First, it takes institutions seriously by conceptualizing them as opportunity structures that influence domestic politics by redistributing resources between actors instead of only considering them as tools of powerful states. This conceptualization also allows us to study under which conditions non-state actors might profit from regionalism to explain processes of reform and change. Second, it clearly spells out how membership in ROs can constrain challengers and thereby increase the likelihood of regime survival. Third, it combines existing knowledge on regime-boosting identified for different regions and ROs into one encompassing framework. Finally, it is parsimonious enough to be applied to study different types of autocratic regimes and different regions to allow for meaningful comparison.

Empirically, the article illustrates how the proposed involvement of ROs during moments of political turmoil added to incumbent survival in three novel case studies focusing on the Southern African Development Community’s (SADC) support of legitimation in Zimbabwe during the 2008 election crisis, the role of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in repressing the Urumqi riots in China in 2009, and the engagement of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in co-optation during the Arab Spring uprisings in Bahrain in 2011. It thereby further contributes to specific regional knowledge by exploring cases such as the Chinese Uighur issue that have not yet received much attention by the regime-boosting literature, as well as highlighting new dimensions on well-discussed cases such as the role of regional economic incentives and co-optation in stabilizing Bahrain or regional discourses legitimizing Mugabe’s rule in Zimbabwe.

Linking regionalism and authoritarian survival

To conceptualize the regional-domestic link in non-democratic regimes, the following section builds on existing research to develop a theoretical framework that links membership in ROs to authoritarian survival via four survival strategies: legitimation, repression, co-optation, and international appeasement. ROs as opportunity structures offer domestic actors the possibility to empower themselves vis-à-vis other actors if they have the capacity to exploit opportunities and avoid constraints. RO membership can thus help autocratic incumbents to increase their chances of survival if they are able to successfully employ additional material, informational, and ideational resources to strengthen any one of the domestic survival strategies from the autocrat’s toolbox, and thereby further constrain challenging actors.

Conceptualizing the regional and domestic arena

In contrast to realists who regard ROs as epiphenomenal, institutionalists recognize the constraining effects that ROs can have for domestic politics.Footnote28 In line with rational-choice institutionalism, ROs can be conceived as opportunity structures that affect the power distribution between domestic actors by providing additional resources to some and thereby constraining others.Footnote29 Essentially, RO membership thereby leads to differential empowerment of actors at the domestic level depending on their capacity to exploit opportunities and avoid constraints. Resources can include both material benefits from cooperation in the form of financial redistributions, market access, military equipment, or other forms of technical support as well as more intangible benefits stemming from knowledge exchange, symbolic politics, diplomacy, or common norms and discourses.Footnote30 While the Europeanization literature has come to the conclusion that EU membership has not systematically empowered one particular group over another,Footnote31 we can expect autocratic incumbents to have an advantage in profiting from regionalism due to the already constrained domestic environment in which oppositional actors have to move.

Politics in authoritarian regimes are characterized by strategic political elites who strive for political survival by mitigating the double-dilemma of authoritarian rule: simultaneously achieving control over the population and establishing appropriate power-sharing arrangements with societal elites.Footnote32 A more recent third facet of the autocrat’s dilemma that should also be considered is the relationship with international actors that might put external pressure on incumbents in order to empower reform coalitions and incentivize democratization.Footnote33 To mitigate these internal and external challengers, the autocrat’s toolbox essentially contains the strategies of legitimation, repression, and co-optation as highlighted by the work of Gerschewski,Footnote34 but must be extend by a forth strategy highlighted by this article, international appeasement.

Legitimation is directed towards creating diffuse support from the population, and is achieved by offering claims to legitimacy that justify the division between ruler and ruled.Footnote35 While the most popular type of legitimation today is the creation of democratic institutions,Footnote36 legitimation can also rest on providing alternative narratives based on tradition, ideology, or output.Footnote37 Repression can be exerted through soft (i.e. non-violent restriction of rights and creation of fear) and hard (violent) means to coerce the population and oppositional actors into rule-conforming behaviour and discourage them from challenging the incumbent elites.Footnote38 Since violent forms of coercion tend to decrease legitimacy and unite the opposition, incumbents also have to create loyalty amongst oppositional actors and fellow elites through co-optation. This strategy essentially involves tying key political and societal groups to the incumbent by offering incentives in the form of power, material benefits, or reputational gains within formal institutions or through patrimonial networks.Footnote39 Finally, I argue that external pressures from democratic powers and donors can be mitigated through international appeasement. This strategy essentially either involves signalling compliance with demands for democratic governance without jeopardizing core powers of the regimeFootnote40 or devaluing the applicability of democracy and human rights.Footnote41

Regime-boosting regionalism through executive empowerment

Based on these conceptualizations, we can conceive of regime-boosting regionalism as a process of executive empowerment that works by strengthening each respective survival strategy, thereby further constraining internal and external challengers and raising the likelihood of incumbent survival (see ). Ideational resources such as diplomatic support, symbolic politics, or joint discourses can help to raise domestic legitimacy and to appease international democracy promoters that put pressure on regimes to liberalize. Material and informational resources from security cooperation boost the repressive capacities of regimes to enable incumbents to suppress oppositional groups or civic uprisings. Finally, material benefits from economic and financial cooperation can be used to strengthen co-optation strategies meant to buy the loyalty of key societal elites.

Domestic legitimation and international appeasement are often employed simultaneously by symbolically engaging in regionalism. Both processes essentially involve mock strategies that validate regimes as democratically elected, internationally engaged, and committed to international norms of good governance without actually enforcing standards. First, RO membership simply signals a commitment to peaceful cooperation and public goods provision to domestic and international audiences, with ROs as a venue to receive unconditional diplomatic support from fellow autocrats to boost domestic legitimacy.Footnote42 Second, autocrats can also transfer commitments to democracy, human rights, or the rule of law to mere declaratory regional treaties to fend off pressure for democratization, to contain negative externalities and subsequent loss of international recognition, or to satisfy international donor communities.Footnote43 Due to the lack of enforcement mechanisms, they do not, however, run the risk of having to follow through with extensive domestic implementation. The Arab League has, for instance, reacted to international pressure to up their human rights practice by passing a Human Rights Charter in 2004 and even approving the establishment of an Arab Court of Human Rights in 2014, however without including any form of conditionality.Footnote44

This mock practice is specifically important with regard to validating elections. Many electoral autocracies jointly employ ROs to legitimize flawed elections by setting up regional “shadow” monitoring missions. These observers usually report very favourably about the democratic quality of manipulated incumbent elections without engaging in meaningful monitoring activities, while disrupting the work of more critical missions from established organizations, thereby providing international sources of legitimation for incumbents.Footnote45 Unsurprisingly, ROs with a significant number of autocratic members are amongst the least critical election monitors worldwide and keep endorsing some of the most blatantly flawed elections as free and fair.Footnote46 Their recognition is then disseminated domestically to validate results as regionally accepted, while international criticism can be discarded as unfounded. After winning the 2013 presidential elections, Robert Mugabe for instanced stated in his inauguration speech: “We abide by the judgement of Africa … Today it is these Anglo-Saxons who dare contradict Africa’s verdict over an election in Zimbabwe, an African country.”Footnote47

Simultaneously, autocrats attempt to raise domestic legitimacy by devaluing democracy and human rights, and in extension the activities of domestic and international democracy promoters. ROs as ideational communities provide an identity function for member regimes. By presenting themselves as part of an “alternative” ideational community, incumbents can strengthen domestic legitimation narratives and contest the validity of challenges based on democracy, the rule of law or human rights.Footnote48 Russia in particular has been engaged in using “Eurasianism” to counter democratization by continuously questioning the universal applicability of democratic governance, human rights, and liberal norms and instead legitimizing its autocratic rule as an alternative form of democracy.Footnote49 Similarly, members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) have employed the “ASEAN Way” – an alternative form of conducting international relations based on consensual and informal politics – to defend human rights violations and undercut democratic values.Footnote50

RO security and military cooperation in the form of joint military structures, exchange of security technology, weapon sales or intelligence sharing is key for the third process, boosting domestic repressive capacities. Many ROs have increasingly developed security and military capacities over time or have been specifically founded as security institutions.Footnote51 This security dimension can be exploited by member states by employing RO security discourses to normalize repression and criminalize dissidents in the name of regional security.Footnote52 Furthermore, particularly joint intelligence sharing can be an attractive security-related perk of RO membership for authoritarian regimes that generally rely heavily on security institutions to coerce oppositional groups and dissidents. Practices of cross-border policing and intelligence sharing have been on the rise both in Eurasia and the Gulf to enable the prosecution of critical actors independently of his or her physical location under the guise of fighting terrorism and securing regional stability.Footnote53 As a matter of last resort, ROs might even offer military assistance to fellow RO members to deter or squash dissidents, although pro-regime military intervention comes with a high threshold and has thus far only been employed once in Bahrain during the Arab Spring uprisings.Footnote54

Finally, ROs can provide material benefits from financial and economic cooperation to strengthen domestic co-optation of intra-elite groups. Financial redistributions or tariff revenues from state-led market liberalization can be used to buy the loyalty of key political and societal actors and sustain patronage networks. In this regard, development assistance channelled through ROs particularly from new donors from South-South cooperation might represent a particularly important way to increase rent-seeking capacities, especially considering the fact that these forms of development assistance often come without attached conditionality.Footnote55 The Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America (ALBA) for instance provides cheap access to oil for member states, while the Commonwealth of Independent States allows for free migration of workers to Russia, thereby indirectly supporting a redistribution of resources to like-minded regimes.Footnote56

Furthermore, formal domestic institutions play an important patronage function because they can help to prevent elite splits that might lead to regime change.Footnote57 This realm can be expanded through RO memberships where prestigious diplomatic positions can be handed to key political actors in an effort to further tie them to the regime. Scholars of regional integration in Sub-Saharan Africa argue that regionalism is often an attempt to accumulate diplomatic positions to reward politicians, business elites and military personnel with reputable jobs.Footnote58 Finally, even purely rhetorical strategies using the language of economic regionalism might appease and bind business elites to the regime by signalling commitment to demands for regional market liberalization.Footnote59

Regime-boosting regionalism in practice

In subsequent sections, I apply the proposed framework to three case studies to show how ROs can help to strengthen authoritarian survival politics in practice. Each case identifies a specific threat and corresponding survival strategy to trace how the RO was involved in dealing with the challenge (see overview in ). The first case focuses on the role of SADC during the election crisis in Zimbabwe in 2008 and follows the efforts of long-term leader Mugabe to remain in power by signalling democratic legitimacy to domestic and international audiences. The second case shows how the Chinese Communist Party has been able to benefit from SCO membership to strengthen the repression of Muslim Uighur minority groups in Xinjiang after the Urumqi riots in 2009. The third case deals with the co-optation (and repression) strategy of the Bahraini regime to deal with challenges from political activists and key elites from within the royal family during the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 through financial (and military) aid received by the GCC.

Table 1. Overview of cases.

Since the argument is based on presenting evidence on survival – i.e. non-change in the dependent variable – all three cases deal with crisis moments that make survival strategies and RO involvement more visible. To increase the representativeness and external validity of findings, the case selection follows a most-different methodFootnote60 whereby cases are similar with regard to the dependent variable (survival) and the main independent variable (RO membership) but vary on other alternative explanatory variables that have been shown by the literature to be important domestic and international drivers of regime survival. On the domestic level, institutionsFootnote61 and economic capacityFootnote62 have been identified as main explanations of stability, with international linkage and leverageFootnote63 as international factors that can explain variation.Footnote64 Zimbabwe is an electoral autocracy in Sub-Saharan Africa, with poor economic and military capacity which has been highly isolated internationally due to EU and UN sanctions put on the Mugabe regime in the 2000s. Bahrain is an absolute monarchy in the Middle East, with medium economic capacity that has strong ties to the United States due to multiple military bases stationed on their territory. Finally, China as a dominant party regime under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) dominates regional relations due to its high economic performance and is one of the main emerging powers in global politics.

While the cases differ with regard to these major alternative explanations, all three cases are similar in that ROs were involved during a major moment of political instability, and all regimes managed to successfully survive the challenge in question. Importantly, I do not argue that RO involvement was solely responsible for survival, but only that it contributed to the successful resolution of the crisis. To establish that the relationship is not a spurious correlation, the article analyses official documents provided by regimes and ROs, secondary literature, and reporting by national and international media outlets to build a timeline of events that can trace when, how, and through which means ROs were involved in the successful solution of a crisis situation in a member regime.

SADC, legitimation and international appeasement: the 2008 election crisis in Zimbabwe

With the rise of electoral democracy as an international norm, autocrats face a new dilemma: either hold free and fair elections under the auspices of international monitors, but risk losing power; or manipulate electoral proceedings and bear the cost of losing democratic legitimacy. The dilemma hit the Zimbabwe regime under the rule of long-time President Robert Mugabe who received increasing pressure to step down after manipulating electoral results during the 2008 general elections.Footnote65 To deal with the crisis and keep Mugabe in power, the regime needed to both re-legitimize Mugabe domestically and regionally and fend off international calls to sanction the regime.

SADC membership emerged as a critical factor during the crisis. Mugabe successfully exploited SADC’s regional identity discourses surrounding “African renaissance” to validate his standing as Africa’s liberation hero and to fend of pressure from critical actors by de-legitimizing them as part of an outgroup controlled by Western powers. This led to SADC offering continued diplomatic support to Mugabe instead of intervening in favour of the opposition and conferred democratic legitimacy upon him as the rightful representative of the state.

After Mugabe and the ruling ZANU-PF party ostensibly lost the first round of elections on March 29, the regime managed to rig vote counting to necessitate a second round of Presidential run-off elections. It simultaneously started to violently target members of the opposition party finally leading to the withdrawal of the opposition candidate Tsvangirai from the race before the second round. While SADC did convene an emergency-meeting on April 12 called for by Zambia, the official SADC statement remained free of open criticism of Mugabe, with Southern African president Mbeki instead insisting that the issue was a matter of domestic affairs and the elections represented “a normal electoral process.” Footnote66 The final SADC statement even commended the Government for holding peaceful elections, and only called for a speedy announcement and broad acceptance of results.Footnote67

As the sole contender, Mugabe emerged victorious from the second election round on June 23, although the proceedings were criticized as undemocratic both by representatives of the SADC monitoring mission and SADC members Zambia and Botswana. However, the official SADC electoral report merely appeals to “the relevant authorities, particularly supporters of political parties and candidates to refrain from all forms of violence”Footnote68 instead of officially condemning the regime. Rather, Mugabe was invited to attend the AU summitry meeting in full standing only a week later,Footnote69 South Africa intervened at the United Nations Security Council to lobby against resolutions calling for additional sanctions in JulyFootnote70 and SADC helped to keep Mugabe and loyal party cadres in executive control during the SADC-mediated negotiations for a power-sharing agreement with the opposition party throughout August and September. The final agreement signed September 15 grants Mugabe full executive power with oppositional candidate Tsvangirai as head of a toothless second Cabinet and loyal Mugabe party cadres in charge of key Ministries. In spite of rigged elections, SADC’s continued diplomatic support thus enabled Mugabe to refuse exit by claiming that he was the legitimately elected leader of Zimbabwe, with the opposition party and regional critics unable to initiate SADC action to intervene in their favour.

SADC’s non-intervention can be explained by Mugabe’s efforts to exploit the SADC-coined discourse on pan-African solidarity and Western imperialism to strengthen his legitimacy as the continent’s liberation hero and to simultaneously de-legitimize critical actors as neo-colonial imperialists. This rhetoric particularly surfaced before and after important SADC meetings to prevent critics from successfully demanding institutional intervention against the regime. Oppositional candidate Tsvangirai was charged to “deliberately engage in reversing the gains of our liberation”Footnote71 to discredit his accusations of vote rigging before the SADC emergency meeting in April, with Southern African President Mbeki strengthening Mugabe’s propaganda by calling Tsvangirai “a militant critic” instead of “taking responsibility for the future of Zimbabwe.”Footnote72 In the wake of the SADC summitry meeting in August, Mugabe furthermore accused regional critic Botswana of deliberately destabilizing Zimbabwe as a “surrogate” of Western imperial power interference.Footnote73 This framing strategy was evidently successful, particularly in constraining regional critics who refrained from taking unilateral action or further pressuring for SADC intervention to avoid isolation from the Southern African community.Footnote74

The SCO and repression: the 2009 Urumqi riots in Western China

To the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), upholding territorial integrity is of particular importance due to increasing political engagement by ethnic minority groups that are clustered in the Western border provinces Xinjiang and Tibet and demand more autonomy.Footnote75 The CCP’s central legitimation narrative has been built on the notion of a united China encompassing all border regions (most importantly Taiwan) and is both codified in domestic law and enacted internationally through the “One China Principle”.Footnote76 Reports of Muslim Uighurs being detained in “re-education camps”, especially if they have family outside of China, increasingly surfaced in the last years and show how deeply the CCP feels threatened by Uighur activism.Footnote77

The Uighur issue first received more widespread attention in July 2009, when demonstrations broke out in Xinjiang’s capital city Urumqi and soon radicalized after clashes with police in the days after.Footnote78 While the sources of unrest remain contested with both Uighurs and the CCP claiming that the other attacked first, the CPP reacted with a complete lock-down and communications blackout in Xinjiang, large-scale arrests of more than 1,400 Uighurs in the preceding weeks, and a fervent public relations campaign against Uighur groups that framed riots as Islamic terrorism.Footnote79 The SCO played a decisive role for the CCP to repress rioters more effectively both by helping to frame and criminalize protestors as Islamic terrorists based on the SCO “three-evils” doctrine and by exploiting joint intelligence and military command structures to pursue, deter and threaten Uighurs across borders in subsequent months.

When riots first broke out on July 5, the CCP was intent on reporting about the incident on Chinese state media and framing rioting Uighurs as illegitimate terrorists that had to be pursued and prosecute. To this end, the CCP relied heavily on the so-called “three evils doctrine”, which refers to the main objective of the SCO, the fight against religious extremism, terrorism, and separatism. The CCP deployed loudspeaker trucks and red banners warning from the “three evils” all over Xinjiang, security forces carried banners reading “we must defeat the terrorists” and “oppose ethnic separatism and hatred,”Footnote80 and Han Chinese interviewed on TV kept stating that they would not let the three evils destroy social harmony and economic progress.Footnote81 The SCO Secretary General further lent support to the framing, announcing tightened SCO cooperation in the face of the three evils: “The fight against the “East Turkestan” forces has been the top priority of the SCO since it was established, and we are confident that we will emerge the winner.”Footnote82

While the riots had been largely squashed by July 8, Uighur mobilization remained an immediate danger to the CCP and authorities therefore proceeded to employ a number of measures in the following days, weeks and months to repress and prosecute Uighurs and deter future actions. In a first step, the CCP began to arrest large numbers of Uighurs based on accusations tied to the three evils, particularly terrorism and separatism. Based on estimations by NGOs, up to 1,400 Uighurs were arrested, with more than 200 prosecutions tied to terrorism charges and at least 30 death sentences issued by the end of 2009.Footnote83 In a second step, joint intelligence structures allowed the CCP to pursue and prosecute Uighurs across borders through blacklisting, extradition, and denial of asylum organized within the SCO Regional Antiterrorism Structure (RATS).Footnote84 Based on these blacklists, the CCP had previously already framed the World Uighur Congress as a terrorist organization, and now moved to accuse its exiled Uighur dissident leader Rebiya Kadeer for orchestrating the Urumqi riots from abroad as early as July 6.Footnote85 The accusation was widely broadcast on national TV to further sooth enraged Han Chinese and legitimize the repression of Uighurs groups.

Additionally, an updated SCO Counter-Terrorism Convention signed earlier in 2009 had established jurisdiction over individuals and groups accused of terrorism in any of the SCO member states.Footnote86 The NGO Human Rights in China (HRIC) documented more than 70 cases of forcible returns between SCO members amongst them several that had fled Xinjiang after having been targeted by Chinese authorities for alleged connections to terrorist groups.Footnote87 In a prominent case, Kazakhstan repatriated Uyghur refugee, Ershidin Israil, who had fled Xinjiang following the 2009 riots, although he had already been granted refugee status by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). On Chinese request, Israil was detained, refused departure to Scandinavia, and transferred to China in May 2011.Footnote88 UNHCR even transferred the power to decide upon the refugee status of Chinese Uighurs to the Kazakh authorities, giving them more power to enact the joint SCO extradition agreements.Footnote89 Until today, China has profited immensely from these joint SCO practices to retrieve and detain Uighurs in “re-education” camps.Footnote90

Third, the CCP moved to enshrine the three evils doctrine into regional law immediately after the end of the riots through the 2009 amendment to the XUAR Regulation on the Comprehensive Management of Social Order in order to establish a legal basis for future prosecution of Uighurs as terrorists, a move that has been mirrored in other SCO member states.Footnote91 In a final step, joint SCO military training missions were employed to threaten future dissidents from challenging the regime. The 2010 SCO “Peace Mission” following the Urumqi riots staged the largest to date counter-terrorism drill in Kazakhstan, with over 5000 troops from most SCO member states participating to showcase “a ‘timely’ demonstration of the SCO’s contribution to combat terrorism, separatism and extremism.” Footnote92

The GCC and co-optation: the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings in Bahrain

The six member states of the GCC are run as dynastic monarchies with vast oil reserves that base their legitimacy on traditional Sunni-monarchical identity and the provision of public goods. To the Gulf regimes, the Arab Spring uprisings represented a new type of substantial threat emanating from within their societies. Calls for constitutional monarchy that would severely limit or even remove the power of the ruling families only surfaced during the 2011 uprisings, and played out especially strong in Bahrain’s highly polarized society, where the Shiite population has increasingly been marginalized by the ruling Sunni royal family.

Large-scale protests first broke out on February 14, 2011, and were met with harsh response by security forces. However, the Bahraini regime surprisingly withdrew its troops after these initial protests on February 19, and initiated a “national dialogue” to calm the situation.Footnote93 Although Crown Prince Salman attempted a strategy of reform and accommodation, demonstrations spread throughout the country as demands turned more radical.Footnote94 During this time, the GCC emerged as a critical actor in support of the Bahraini regime by providing an institutional forum to coordinate material support aimed at co-opting both reform-oriented factions within the royal family, pro-regime Sunni minority groups, as well as political activists and societies. The situation was, however, finally resolved through repression with the help of the GCC military intervention.

In a first step, the Bahraini regime recurred to familiar ways of co-optation through large-scale investment projects and financial handouts. The regime announced that it would recruit up to 20,000 new people into all ministry departments, and planned to invest 2.5 billion dollars into new housing projects across the country.Footnote95 While bureaucratic jobs are well-paid, secure, and highly attractive positions in the Gulf monarchies, they are effectively not available to the Shiite population that has been marginalized from public service.Footnote96 Instead, the regime intended to mainly co-opt Sunni citizens, the traditional support base of the regime. To finance this co-optation strategy, Bahrain was able to draw on the “Gulf Development Program”, a 10 billion USD Marshall Plan-like package of support by the resource-rich GCC members to poorer Bahrain and Oman that was announced during the 118th session of GCC foreign ministers in March.Footnote97

The GCC also proofed to be a valuable forum to coordinate co-optation strategies from day one. Mere days after violent responses to initial protests, the extra-ordinary session of GCC foreign ministers marked a remarkable turn towards an initially peaceful handling of the crisis. Crown Prince Salman, head of the reform section within the Bahraini royal family, was tasked to initiate a national dialogue with protestors and political societies to carve out ways of reforming the kingdom. The dialogue was announced to table issues such as establishing a fully elected parliament with enhanced authority, redrawing voting districts to allow a fairer representation of Shiite population, and addressing sectarian polarization that were previously on the blacklist of topics to discuss. However, the move seems to have been a way to co-opt the reform faction as well as political activists and leading political societies such as Al-Wifaq via promise of institutionalized political dialogue.Footnote98

The co-optation strategy seemed to take effect: while early protestors wore badges reading “No Sunni, No Shi‘a, Just Bahraini”, later more and more Sunni Bahrainis started to support the regime.Footnote99 Co-optation of Sunni groups was additionally supported by a joint GCC propaganda campaign rolled out at the extra-ordinary meeting of GCC foreign ministers on February 17 that framed protestors as Iranian-led insurgencies. In the GCC summit statement, the RO rejects “any external interference in the internal affairs of the Kingdom of Bahrain”Footnote100, and during the later regular summit Iran’s alleged meddling was even reprimanded as “flagrant intervention” and a “violation of their sovereignty, independence and principles of good-neighborliness.”Footnote101 In response, pro-regime demonstrations, a country-wide Sunni-led boycott against Shi’a-owned business, as well as growing vandalism in Shi’a shrines and mosques were staged,Footnote102 evidencing the growing resentment against Shi’a in response to the regime propaganda: “As these rumors of Iranian involvement spread, more and more Sunnis distanced themselves from the movement.”Footnote103

While Salman was negotiating with protestors, the hard-liner faction around the Prime minister prepared for a security solution to the crisis to repress protestors. On March 13, King Hamad asked for the support of GCC military troops under the joint “Peninsula Shield Force” command to squash protestors.Footnote104 Salman was sacked from his role as leader of the national dialogue and replaced by the Speaker of Parliament, who wields no executive and political power, and was thus the perfect decoy to continue a façade co-optation strategy with political opposition. In the following months, GCC security cooperation was updated to allow for more effective cross-border persecution of critical actors which allowed the Bahraini regime to severely clamp-down on opposition groups, particularly those with Shiite background.Footnote105

Conclusion

Regionalism has increasingly become a way of organizing international relations between geographically and culturally proximate states. Especially autocratic regimes are some of the biggest fans of regional institution-building and often try to exploit their membership to further domestic regime interests in survival. But how can RO membership actually help to keep incumbents in power?

I argue that ROs as political opportunity structures affect domestic politics by redistributing resources between actors, and thereby strengthen executive capacity of autocratic incumbent elites to execute survival strategies vis-à-vis internal and external challengers. During moments of political upheaval, RO membership can thus provide incumbents with crucial material, informational, and ideational boosts to increase the chances of holding on to the reins of power. The argument is illustrated by case-based evidence that shows how ROs have been involved during three major moments of political upheaval in member states. While the degree to which RO membership contributes to domestic survival certainly varies between cases and domestic factors often remain decisive to ensure survival, regional resource often play a major role to successfully resolve political crisis.

While this article has focused on explaining how autocratic incumbents are able to profit from regionalism through executive empowerment, the proposed conceptualization of ROs as opportunity structures also allows research into conditions under which other societal actors might be able exploit regional opportunities to put pressure on regimes to reform. Autocratic members of ASEAN, ECOWAS or the African Union for instance have increasingly been constrained by institutional requirements for good governance that have strengthened civil society actors, resulting in differential empowerment.Footnote106 Further exploring scope conditions of regime-boosting is also important given the growing debate on challenges to democratic lock-in and legitimacy even in democratic ROs such as the EU, with populist leaders increasingly questioning and subverting democratic norms.Footnote107 EU and international relations scholars could thus also profit from these comparative insights for their future research to identify under which conditions populist parties and leaders might be able to successfully exploit European institutions to further their non-democratic goals.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to two anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback and guidance. The author also wants to thank Tanja A. Börzel, Sean L. Yom, Thomas Risse, Hylke Dijkstra, Sebastian Knecht, as well as members of the Kolleg-Forschergruppe “The Transformative Power of Europe” and the Berlin Graduate School of Transnational Studies at Free University Berlin, and conference participants at ISA, ECPR General Conference, NorDev, and the APIR Seminar at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin (WZB) for useful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria J. Debre

Maria Debre is a postdoctoral researcher at Maastricht University within the ERC-funded research project “Who gets to live forever? Toward an Institutional Theory on the Decline and Death of International Organisations”. She received her PhD from the Free University Berlin within the Berlin Graduate School of Transnational Studies and the Research College (KFG) ‘The Transformative Power of Europe’. She has subsequently been a Fox International Fellow at the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Centre for International and Area Studies at Yale University.

Notes

1 Pevehouse, Democracy from Above.

2 Söderbaum, The Political Economy of Regionalism.

3 Kono and Montinola, “The Uses and Abuses of Foreign Aid.”

4 Peksen and Drury, “Coercive or Corrosive.”

5 Risse and Babayan, “Democracy Promotion and the Challenges of Illiberal Regional Powers”; Tolstrup, Russia vs. the EU; Stoddard, “Authoritarian Regimes in Democratic Regional Organisations?”

6 Von Soest, “Democracy Prevention”; Libman and Obydenkova, “Informal Governance and Participation in Non-Democratic International Organizations”; Obydenkova and Libman, Authoritarian Regionalism in the World of International Organizations.

7 Tansey, The International Politics of Authoritarian Rule; Bader, China’s Foreign Relations and the Survival of Autocracies; Vanderhill, Promoting Authoritarianism Abroad; Tolstrup, “Black Knights and Elections in Authoritarian Regimes.”

8 Kneuer et al., “Playing the Regional Card”; Libman and Obydenkova, “Regional International Organizations as a Strategy of Autocracy.”

9 Fawn, International Organizations and Internal Conditionality; Debre and Morgenbesser, “Out of the Shadows.”

10 Russo and Stoddard, “Why Do Authoritarian Leaders Do Regionalism? ”; Allison, “Virtual Regionalism”; Ambrosio, “Catching the ‘Shanghai Spirit’.”

11 Herbst, “Crafting Regional Cooperation in Africa.”

12 Cooley and Heathershaw, Dictators Without Borders.

13 Jetschke, “Why Create a Regional Human Rights Regime? ”; van Hüllen, “Just Leave Us Alone.” A related debate circles around the question of diffusion of authoritarian norms and practices and authoritarian learning as a more unintentional form of external influence on regime survival, e.g.: Lankina, Libman, and Obydenkova, “Authoritarian and Democratic Diffusion in Post-Communist Regions”; Yom, “Authoritarian Monarchies as an Epistemic Community.”

14 E.g. Börzel and Risse, “Conceptualizaing the Domestic Impact of Europe.”

15 E.g. Obydenkova, “Democratization at the Grassroots”; Lankina and Getachew, “A Geographic Incremental Theory of Democratization.”

16 Libman and Obydenkova, “Understanding Authoritarian Regionalism.”

17 Kneuer et al., “Playing the Regional Card.”

18 Yom, “Authoritarian Monarchies as an Epistemic Community”; Collins, “Economic and Security Regionalism”; Debre and Morgenbesser, “Out of the Shadows.”

19 E.g. in Kneuer et al., “Playing the Regional Card”; Tansey, The International Politics of Authoritarian Rule.

20 Hooghe, Lenz, and Marks, A Theory of International Organization.

21 Keohane, After Hegemony.

22 Gerschewski, “The Three Pillars of Stability”; Svolik, The Politics of Authoritarian Rule.

23 Dukalskis and Gerschewski, “What Autocracies Say (and What Citizens Hear).”

24 Escribà-Folch, “Repression, Political Threats, and Survival under Autocracy.”

25 Gandhi and Przeworski, “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.”

26 Börzel and van Hüllen, Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations.

27 This article cannot deal with the question by how much regionalism boosts survival chances, since this goes beyond the qualitative research design and requires quantifiable data.

28 Keohane, After Hegemony.

29 Börzel and Risse, “Conceptualizaing the Domestic Impact of Europe.”

30 Johnston, “Treating International Institutions as Social Environments.”

31 Börzel and Risse, “Conceptualizaing the Domestic Impact of Europe.”

32 Svolik, The Politics of Authoritarian Rule.

33 Burnell, Democracy Assistance; Whitehead, The International Dimensions of Democratization.

34 Gerschewski, “The Three Pillars of Stability.”

35 Beetham, The Legitimation of Power.

36 Schedler, Electoral Authoritarianism.

37 Dukalskis and Gerschewski, “What Autocracies Say (and What Citizens Hear).”

38 Escribà-Folch, “Repression, Political Threats, and Survival under Autocracy.”

39 Gandhi and Lust-Okar, “Elections Under Authoritarianism”; Svolik, “Power Sharing and Leadership Dynamic in Authoritarian Regimes.”

40 Börzel and van Hüllen, Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations.

41 Fawn, International Organizations and Internal Conditionality; Ambrosio, Authoritarian Backlash.

42 Söderbaum, The Political Economy of Regionalism.

43 Börzel and van Hüllen, Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations.

44 van Hüllen, “Just Leave Us Alone.”

45 Debre and Morgenbesser, “Out of the Shadows.”

46 Kelley, “D-Minus Elections.”

47 Zimbabwe Situation, “Transcript - Mugabe’s Inauguration Speech.”

48 Ambrosio, Authoritarian Backlash.

49 Ibid.

50 Acharya, “Democratisation and the Prospects for Participatory Regionalism.”

51 Kacowicz and Press-Barnathan, “Regional Security Governance.”

52 Ambrosio, “Catching the ‘Shanghai Spirit’”

53 Yom, “Collaboration and Community amongst the Arab Monarchies”; Cooley and Heathershaw, Dictators Without Borders.

54 Yom, “Authoritarian Monarchies as an Epistemic Community.”

55 Hodzi, Hartwell, and de Jager, “‘Unconditional Aid’.”

56 Libman and Obydenkova, “Understanding Authoritarian Regionalism.”

57 Gandhi and Przeworski, “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.”

58 Bach, “The Global Politics of Regionalsim: Africa”; Herbst, “Crafting Regional Cooperation in Africa.”

59 Collins, “Economic and Security Regionalism.”

60 Gerring, Case Study Research.

61 Pepinsky, “The Institutional Turn in Comparative Authoritarianism.”

62 Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development; Ulfelder, “Natural-Resource Wealth and the Survival of Autocracy.”

63 Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War.

64 Regional historical legacies argued to shape trajectories of regime development (e.g. in Lankina, Libman, and Obydenkova, “Appropriation and Subversion.”) will be treated as scope conditions in the case studies.

65 International Crisis Group, “Negotiating Zimbabwe’s Transition.”

66 Aljazeera, “Zimbabwe Focus of Regional Summit.”

67 SADC, “Communiqué of the 2008 First Extra-Ordinary SADC Summit.”

68 SADC, “Election Observation Mission Preliminary Report”, 4.

69 SADC, “Communiqué of the Extraordinary Summit of the SADC Organ”; African Union, “African Union Summit Resolution on Zimbabwe.”

70 United Nations, “Security Council 5933rd Meeting.”

71 BBC News, “Mugabe Attacks Opposition and UK.”

72 News24, “Mbeki Slams Tsvangirai.”

73 Mail&Guardian, “Botswana Denies Plot to Unseat Mugabe.”

74 Nathan, Community of Insecurity.

75 Clarke, “Ethnic Separtism in the People’s Republic of China.”

76 Shambaugh, China Goes Global.

77 CNN News, “Former Xinjiang Teacher Claims Brainwashing.”

78 New York Times, “Rumbles on the Rim of China’s Empire.”

79 Ibid.

80 BBC News, “China Leaders Vow Xinjiang Action.”

81 NBC News, “Chinese Muslims Target of Propaganda Effort.”

82 China Daily, “Xinjiang Riot Hits Regional Anti-Terror Nerve.”

83 Amnesty International, “‘Justice, Justice’. The July 2009 Protests”; Human Rights Watch, “China: Detainees ‘Disappeared’ After Xinjiang Protests” & “China: Xinjiang Trials Deny Justice.”

84 Cooley and Heathershaw, Dictators Without Borders.

85 BBC News, “Timeline: Xinjiang Unrest.”

86 SCO, “Convention of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization”, Art. 5.

87 Cf. HRIC, “Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights, Appendix D.”

88 Reuters, “Kazakh Deports Uighur to China.”

89 US Department of State, “Kazakhstan 2012 Human Rights Report.”

90 CNN News, “Former Xinjiang Teacher Claims Brainwashing.”

91 HRIC, “Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights, p. 73f.”

92 quoted in: Weitz, “China’s Growing Clout in the SCO”, 9.

93 Bahrain News Agency, “HM King Hamad Grants HRH Crown Prince Role to Commence Dialogue.”

94 Bahrain News Agency, “No Compromise on National Security.”

95 Bahrain News Agency, “Interior Minister Unveils Plans to Recruit 20000 Employees” & “Housing Minister Unveils Plans to Build 50,000 Units.”

96 Abdo, The New Sectarianism.

97 Washington Post, “GCC Pledges $20 Billion in Aid for Oman, Bahrain.”

98 Louër, “Bahrain’s National Dialogue.”

99 Abdo, The New Sectarianism.

100 Bahrain News Agency, “HM King Hamad Grants HRH Crown Prince Role to Commence Dialogue.”

101 Gulf News (United Arab Emirates), “GCC Condemns Iran’s Interference.”

102 International Crisis Group, “Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East.”

103 France24, “How the Bahraini Monarchy Crushed the Country’s Arab Spring.”

104 Katzman, “Bahrain: Reform, Security, and U.S. Policy.”

105 Ibid.

106 Börzel and van Hüllen, Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations.

107 Krastev, “European Disintegration?”; Pepinsky and Walter, “Introduction to the Debate Section”; Hooghe and Marks, “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration.”

Bibliography

- Abdo, Geneive. The New Sectarianism: The Arab Uprisings and the Rebirth of the Shi’a-Sunni Divide. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Acharya, Amitav. “Democratisation and the Prospects for Participatory Regionalism in Southeast Asia.” Third World Quarterly 24, no. 2 (2003): 375–390.

- African Union. “African Union Summit Resolution on Zimbabwe Adopted at the 11th Ordinary Session of the African Union Assembly.” African Unit Summit Resolution on Zimbabwe. Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt: 11th Ordinary Session, 1 July, July 1, 2008.

- Aljazeera. “Zimbabwe Focus of Regional Summit,” April 13, 2008. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2008/04/2008525123616618856.html.

- Allison, Roy. “Virtual Regionalism, Regional Structures and Regime Security in Central Asia.” Central Asian Survey 27, no. 2 (2008): 185–202.

- Ambrosio, Thomas. Authoritarian Backlash: Russian Resistance to Democratization in the Former Soviet Union. Surrey: Ashgate, 2009.

- Ambrosio, Thomas. “Catching the ‘Shanghai Spirit’: How the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Promotes Authoritarian Norms in Central Asia.” Europe-Asia Studies 60, no. 8 (2008): 1321–1344.

- Amnesty International. “‘Justice, Justice’. The July 2009 Protests in Xinjiang, China.” ASA 17/027/2010. London: Amnesty International, 2010.

- Bach, Daniel. “The Global Politics of Regionalsim: Africa.” In Global Politics of Regionalism. Theory and Practice, edited by Mary Farrell, Björn Hettne, and Luk van Langenhove, 171–186. London and Ann Arbor: Pluto Press, 2005.

- Bader, Julia. China’s Foreign Relations and the Survival of Autocracies. Oxon, New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Bahrain News Agency. “HM King Hamad Grants HRH Crown Prince Role to Commence Dialogue with All Parties in Bahrain,” February 18, 2011. http://www.bna.bh/portal/en/news/447586?date=2011-04-9.

- Bahrain News Agency. “Housing Minister Unveils Plans to Build 50,000 Units in 5 Years,” March 7, 2011. http://bna.bh/portal/en/news/449278?date=2011-09-28.

- Bahrain News Agency. “Interior Minister Unveils Plans to Recruit 20000 Employees,” March 5, 2011. http://www.bna.bh/portal/en/news/449075?date=2011-3-20.

- Bahrain News Agency. “No Compromise on National Security and Safety, HRH Prince Salman Vowed,” March 13, 2011. http://www.bna.bh/portal/en/news/449823.

- BBC News. “China Leaders Vow Xinjiang Action,” July 9, 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8141657.stm.

- BBC News. “Mugabe Attacks Opposition and UK,” April 18, 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7353929.stm.

- BBC News. “Timeline: Xinjiang Unrest,” July 10, 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8138866.stm.

- Beetham, David. The Legitimation of Power. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991.

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Vera van Hüllen. Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations: Patching Together a Global Script. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Thomas Risse. “Conceptualizaing the Domestic Impact of Europe.” In The Politics of Europeanization, edited by Kevin Featherstone, and Claudio M. Radaelli, 57–82. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Burnell, Peter J. Democracy Assistance: International Co-Operation for Democratization. London: F. Cass, 2000.

- China Daily. “Xinjiang Riot Hits Regional Anti-Terror Nerve,” July 18, 2009. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2009-07/18/content_8445811.htm.

- Clarke, Micheal. “Ethnic Separtism in the People’s Republic of China. History, Causes and Contemporary Challenges.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 12 (2013): 109–133.

- CNN News. “Former Xinjiang Teacher Claims Brainwashing and Abuse inside Mass Detention Centers,” May 10, 2019. https://edition.cnn.com/2019/05/09/asia/xinjiang-china-kazakhstan-detention-intl/index.html.

- Collins, Kathleen. “Economic and Security Regionalism among Patrimonial Authoritarian Regimes: The Case of Central Asia.” Europe-Asia Studies 61, no. 2 (2009): 249–281.

- Cooley, Alexander, and John Heathershaw. Dictators Without Borders: Power and Money in Central Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Debre, Maria Josepha, and Lee Morgenbesser. “Out of the Shadows: Autocratic Regimes, Election Observation and Legitimation.” Contemporary Politics 23, no. 3 (2017): 328–347.

- Dukalskis, Alexander, and Johannes Gerschewski. “What Autocracies Say (and What Citizens Hear): Proposing Four Mechanisms of Autocratic Legitimation.” Contemporary Politics 23, no. 3 (March 16, 2017): 251–268.

- Escribà-Folch, Abel. “Repression, Political Threats, and Survival under Autocracy.” International Political Science Review 34, no. 5 (2013): 543–560.

- Fawn, Rick. International Organizations and Internal Conditionality: Making Norms Matter. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- France24. “How the Bahraini Monarchy Crushed the Country’s Arab Spring,” June 9, 2016. https://observers.france24.com/en/20160906-bahrain-monarchy-arab-spring-repression-revolution.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Ellen Lust-Okar. “Elections Under Authoritarianism.” Annual Review of Political Science 12, no. 1 (2009): 403–422.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.” Comparative Politics 11 (2007): 1279–1301.

- Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Gerschewski, Johannes. “The Three Pillars of Stability: Legitimation, Repression, and Co-Optation in Autocratic Regimes.” Democratization 20, no. 1 (2013): 13–38.

- Gulf News (United Arab Emirates). “GCC Condemns Iran’s Interference In Affairs of Its Member States,” June 16, 2011. https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/c297af7d-2ee1-4dcb-a9b9-1ac1e42d3ef7/?context=1516831.

- Herbst, J. “Crafting Regional Cooperation in Africa.” In Crafting Cooperation: Regional Institutions in Comparative Perspective, edited by Amitav Acharya, and Alastair I. Johnston, 129–180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Hodzi, Obert, Leon Hartwell, and Nicola de Jager. “‘Unconditional Aid’: Assessing the Impact of China’s Development Assistance to Zimbabwe.” South African Journal of International Affairs 19, no. 1 (2012): 79–103.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Tobias Lenz, and Gary Marks. A Theory of International Organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39, no. 1 (2009): 1–23.

- HRIC. “Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights: The Impact of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.” Human Rights in China Whitepaper, 2011.

- Hüllen, Vera van. “Just Leave Us Alone: The Arab League and Human Rights.” In Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations. Patching Together a Global Script, edited by Tanja A. Börzel, and Vera van Hüllen, 125–140. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Human Rights Watch. “China: Detainees ‘Disappeared’ After Xinjiang Protests. Chinese Government Should Account for Every Detainee,” October 21, 2009. https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/10/21/china-detainees-disappeared-after-xinjiang-protests.

- Human Rights Watch. “China: Xinjiang Trials Deny Justice. Proceedings Failed Minimum Fair Trial Standards,” October 15, 2009. https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/10/15/china-xinjiang-trials-deny-justice.

- Human Rights Watch. “Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (VIII): Bahrain’s Rocky Road to Reform.” Middle East/North Africa Report No. 111. Manama/Washington/Brussels: International Crisis Group, July 28, 2011.

- International Crisis Group. “Negotiating Zimbabwe’s Transition.” Africa Briefing No. 51. Pretoria/ Brussles: International Crisis Group, May 21, 2008.

- Jetschke, Anja. “Why Create a Regional Human Rights Regime? The ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission for Human Rights.” In Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations. Patching Together a Global Script, edited by Tanja A. Börzel, and Vera van Hüllen, 107–124. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Johnston, Alastair I. “Treating International Institutions as Social Environments.” International Studies Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2001): 487–515.

- Kacowicz, Arie M., and Galia Press-Barnathan. “Regional Security Governance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, edited by Tanja A. Börzel, and Thomas Risse, 297–322. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Katzman, Kenneth. “Bahrain: Reform, Security, and U.S. Policy.” CRS Report Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress, 95–1013, April 13. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, April 13, 2017.

- Kelley, Judith G. “D-Minus Elections: The Politics and Norms of International Election Observation.” International Organization 63, no. 4 (2009): 765.

- Keohane, Robert O. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Kneuer, Marianne, Thomas Demmelhuber, Raphael Peresson, and Tobias Zumbrägel. “Playing the Regional Card: Why and How Authoritarian Gravity Centres Exploit Regional Organisations.” Third World Quarterly 40, no. 3 (2018): 451–470.

- Kono, Daniel Yuichi, and Gabriella R Montinola. “The Uses and Abuses of Foreign Aid: Development Aid and Military Spending.” Political Research Quarterly 66, no. 3 (2013): 615–629.

- Krastev, Ivan. “European Disintegration? A Fraying Union.” Journal of Democracy 23, no. 4 (2012): 1–16.

- Lankina, Tomila, Alexander Libman, and Anastassia Obydenkova. “Authoritarian and Democratic Diffusion in Post-Communist Regions.” Comparative Political Studies 49, no. 12 (2016): 1599–1629.

- Lankina, Tomila V, and Lullit Getachew. “A Geographic Incremental Theory of Democratization: Territory, Aid, and Democracy in Postcommunist Regions.” World Politics 58, no. 4 (2006): 536–582.

- Lankina, Tomila V, Alexander Libman, and Anastassia Obydenkova. “Appropriation and Subversion: Precommunist Literacy, Communist Party Saturation, and Postcommunist Democratic Outcomes.” World Politics 68, no. 2 (2016): 229–274.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Libman, Alexander, and Anastassia V Obydenkova. “Informal Governance and Participation in Non-Democratic International Organizations.” Review of International Organizations 8, no. 2 (2013): 221–243.

- Libman, Alexander, and Anastassia V Obydenkova. “Regional International Organizations as a Strategy of Autocracy: The Eurasian Economic Union and Russian Foreign Policy.” International Affairs 94, no. 5 (2018): 1037–1058.

- Libman, Alexander, and Anastassia V Obydenkova. “Understanding Authoritarian Regionalism.” Journal of Democracy 29, no. 4 (2018): 151–165.

- Louër, Laurence. “Bahrain’s National Dialogue and the Ever-Deepening Sectarian Divide.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 29, 2011. http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/?fa=44882.

- Mail&Guardian. “Botswana Denies Plot to Unseat Mugabe,” December 18, 2008. https://mg.co.za/article/2008-12-16-botswana-denies-plot-to-unseat-mugabe.

- Nathan, Laurie. Community of Insecurity: SADC’s Struggle for Peace and Security in Southern Africa. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

- NBC News. “Chinese Muslims Target of Propaganda Effort,” July 15, 2009. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/31927269/ns/world_news-asia_pacific/t/chinese-muslims-target-propaganda-effort/#.WjgybVSdVbU.

- New York Times. “Rumbles on the Rim of China’s Empire,” July 11, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/12/weekinreview/12wong.html.

- News24. “Mbeki Slams Tsvangirai.” News24, November 28, 2008. https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Mbeki-slams-Tsvangirai-20081128-2.

- Obydenkova, Anastassia V. “Democratization at the Grassroots: The European Union’s External Impact.” Democratization 19, no. 2 (April 1, 2012): 230–257.

- Obydenkova, Anastassia V, and Alexander Libman. Authoritarian Regionalism in the World of International Organizations: Global Perspective and the Eurasian Enigma. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Peksen, Dursun, and A. Cooper Drury. “Coercive or Corrosive: The Negative Impact of Economic Sanctions on Democracy.” International Interactions 36, no. 3 (2010): 240–264.

- Pepinsky, Thomas. “The Institutional Turn in Comparative Authoritarianism.” British Journal of Political Science 44, no. 3 (2014): 631–653.

- Pepinsky, Thomas B, and Stefanie Walter. “Introduction to the Debate Section: Understanding Contemporary Challenges to the Global Order.” Journal of European Public Policy 27, no. 7 (2020): 1074–1076.

- Pevehouse, Jon C. Democracy from Above: Regional Organizations and Democratization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Przeworski, Adam, Michael E. Alvarez, José Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Reuters. “Kazakh Deports Uighur to China, Rights Groups Cry Foul.” Thomson Reuters News Agency, June 7, 2011. http://news.trust.org//item/?map=kazakh-deports-uighur-to-china-rights-groups-cry-foul.

- Risse, Thomas, and Nelli Babayan. “Democracy Promotion and the Challenges of Illiberal Regional Powers: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Democratization 22, no. 3 (2015): 381–399.

- Russo, Alessandra, and Edward Stoddard. “Why Do Authoritarian Leaders Do Regionalism? Ontological Security and Eurasian Regional Cooperation.” The International Spectator I 53, no. 3 (2018): 20–37.

- SADC. “Communiqué of the 2008 First Extra-Ordinary SADC Summit of Heads of State and Government.” Lusaka, Zambia, April 13, 2013.

- SADC. “Communiqué of the Extraordinary Summit of the SADC Organ.” Sandton, South Africa, August 17, 2008.

- SADC. “SADC Election Observation Mission (SEOM) Preliminary Statement.” Harare, Zimbabwe, 2008.

- Schedler, Andreas. Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2006.

- SCO. “Convention of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization against Terrorism.” Yekaterinburg, Russia, June 16, 2009.

- Shambaugh, David L. China Goes Global: The Partial Power. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Soderbaum, Fredrik. The Political Economy of Regionalism. The Case of Southern Africa. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Soest, Christian von. “Democracy Prevention: The International Collaboration of Authoritarian Regimes.” European Journal of Political Research 54, no. 4 (2015): 623–638.

- Stoddard, Edward. “Authoritarian Regimes in Democratic Regional Organisations? Exploring Regional Dimensions of Authoritarianism in an Increasingly Democratic West Africa.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35, no. 4 (2017): 469–486.

- Svolik, Milan W. “Power Sharing and Leadership Dynamic in Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 53, no. 3 (2009): 477–494.

- Svolik, Milan W. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Tansey, Oisín. The International Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Tolstrup, Jakob. “Black Knights and Elections in Authoritarian Regimes: Why and How Russia Supports Authoritarian Incumbents in Post-Soviet States.” European Journal of Political Research 54, no. 4 (2015): 673–690.

- Tolstrup, Jakob. Russia vs. the EU: The Competition for Influence in Post-Soviet States. Boulder: FirstForumPress, 2014.

- Ulfelder, Jay. “Natural-Resource Wealth and the Survival of Autocracy.” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 8 (August 30, 2007): 995–1018.

- United Nations. “Security Council 5933rd Meeting.” New York, July 11, 2008.

- US Department of State. “Kazakhstan 2012 Human Rights Report.” Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012 of the United States Congress. Washington, DC: US Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2012.

- Vanderhill, Rachel. Promoting Authoritarianism Abroad. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2013.

- Washington Post. “GCC Pledges $20 Billion in Aid for Oman, Bahrain,” March 10, 2011. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/03/10/AR2011031003629.html.

- Weitz, Richard. “China’s Growing Clout in the SCO: Peace Mission 2010.” China Brief 10, no. 20 (October 2010): 7–10.

- Whitehead, Laurence. The International Dimensions of Democratization: Europe and the Americas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Yom, Sean L. “Authoritarian Monarchies as an Epistemic Community.” Taiwan Journal of Democracy 10, no. 1 (2014): 43–62.

- Yom, Sean L. “Collaboration and Community Amongst the Arab Monarchies.” In Transnational Diffusion and Cooperation in the Middle East, edited by Marc Lynch, 33–37. POMEPS Studies 21. Washington, DC: Institute for Middle East Studies, George Washington University, 2016.

- Zimbabwe Situation. “Transcript - Mugabe’s Inauguration Speech,” 2013. https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/transcript-mugabes-inauguration-speech-22-august-2013/.