ABSTRACT

Contemporary autocratization is typically the result of a long sequence of events and gradual processes. How can democratic actors disrupt such autocratization sequences in order to enhance democratic resilience? To address this question, this conclusion presents an ideal-typical autocratization sequence and entry points for democratic resilience. It builds on the findings of this special issue, extant research and a novel descriptive analysis of V-Party data. In the first autocratization stage, citizens’ discontent with democratic institutions and parties mounts. Remedies lie in the areas of a better supply of democratic parties and processes as well as in civic education. During the second stage, anti-pluralists – actors lacking commitment to democratic norms – exploit and fuel such discontent to rise to power. In order to avoid the pitfalls of common response strategies, this article suggests “critical engagement”, which balances targeted sanctions against radicals with attempts to persuade moderate followers; and has the aim of decreasing the salience of anti-pluralists’ narratives by means of democratic (voter) mobilization. Thirdly, once autocratization begins, weak accountability mechanisms and opposition actors enable democratic breakdown. Thus, resilient institutions and a united and creative opposition are the last line of democratic defense.

The articles in this Special Issue demonstrate that processes of autocratization are multi-faceted and multi-causal. Because diverse factors may contribute to democratic failure,Footnote1 strategies for democratic resilience are heterogenous. Nevertheless, many contemporary processes of autocratization share one commonality: democracy rarely dies overnight. Rather, “incumbents who accessed power in democratic elections gradually but substantially undermine democratic institutions”.Footnote2 Such processes of democratic erosion often span many years. In each step along that path, anti-pluralists – actors lacking “commitment to key democratic processes, institutions, and norms”Footnote3 – challenge the resilience of democracies.

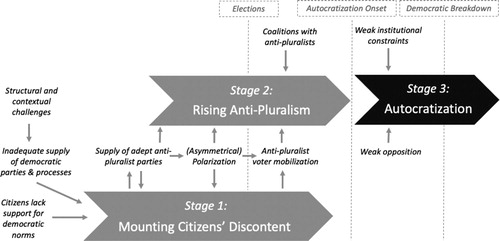

Building on such insights, I propose to schematize the process of autocratization and its drivers into three ideal-typical stages: first, citizens’ discontent with democratic parties and democracy mounts (Stage 1), which enables adept anti-pluralists to rise to power in elections (Stage 2) and then to erode democracy to the extent that is possible given existing constraints (in Stage 3) (see ).

The articles in this special issue explore individual parts of this autocratization sequence. Welzel focuses on the role of democratic norms and values for autocratization and democratic resilience.Footnote4 Finkel and Lim present evidence on how civic education may foster such traits.Footnote5 Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser shed light on the voter potential of the most prevalent type of anti-pluralist party in Western Europe: the Populist Radical Right.Footnote6 Somer, McCoy and Luke demonstrate that pernicious polarization, which many such actors actively promote through wilful political action, enables them to foster an autocratization agenda.Footnote7 Laebens and Lührmann show how accountability mechanisms may halt autocratization even after it has begun.Footnote8 Boese et al. distinguish between factors contributing to the onset of autocratization and those fostering the subsequent breakdown of democracy.Footnote9

The contributions show that autocratization is not inevitable. Many democratic regimes are able to “prevent or react to challenges without losing its democratic character”.Footnote10 What entry points do democratic actors – citizens, politicians, civil society groups, civil servants – have in this autocratization sequence where they can enhance such democratic resilience?

This article addresses this question as follows. Firstly, I develop the idea of an autocratization sequence and demonstrate the central role of anti-pluralist parties in this sequence using data from V-Dem and the V-Party project.Footnote11 In the subsequent three sections, I elaborate on each of the three stages of autocratization in detail, and outline sources of democratic resilience. I conclude with a summary of the main resilience strategies and recommendations for future research.

The autocratization sequence: three stages to democratic breakdown

Structural and contextual challenges heighten the risk of autocratization. These include an economic or financial crisis, inequality, migration, the salience of polarizing cleavages, the rise of new communications technologies and cultural transformation.Footnote12 Such challenges are one of several drivers and mediating factors that determine the “success” of the autocratization sequence. Addressing them in a timely and effective manner shapes democratic resilience. includes some relevant challenges in italics. The list is not exhaustive.

Building on the contributions to this special issue, I argue that the rise of anti-pluralists to power becomes more likely if the following three factors are contributing to citizens’ discontent with democratic parties and institutions: Firstly, an inadequate supply of democratic parties and processes; secondly, lacking support for democratic norms, which may be fuelled by (asymmetrical) polarization; and thirdly, appealing anti-pluralist leaders and parties that skilfully fuel and then exploit such discontent. In order to achieve power, they need to win elections or be invited to join a coalition government. Anti-pluralist mobilization and a lack of mobilization for democratic alternatives contribute to such electoral success.

Even if anti-pluralists are in power, they do not have free reign to erode democracy. Therefore, Boese et al. distinguish between onset and breakdown resilience.Footnote13 In particular, constraints on the power of the executive may halt autocratization once it has started. Institutions (legislature, judiciary, public administration) as well as opposition actors (political parties, civil society groups, citizens) create such accountability mechanisms.Footnote14 These are critical for limiting the damage to democratic institutions, halting autocratization, and paving the way for democratic recovery.

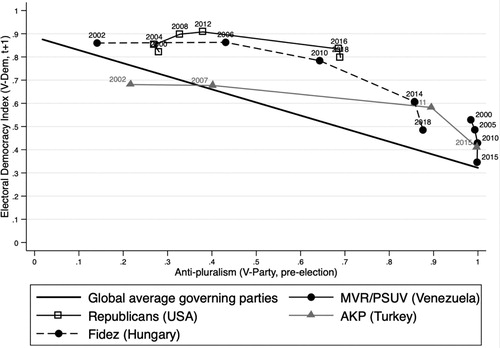

However, once anti-pluralists are in power, autocratization becomes more likely, as illustrates. V-Party measures the degree of anti-pluralism in political parties as the extent to which they lack “commitment to (i) the democratic process; (ii) the legitimacy of political opponents; (iii) peaceful resolution of disagreements and rejection of political violence; and (iv) unequivocal support for civil liberties of minorities”.Footnote15 The thick black line on shows that the relationship between the pre-electoral anti-pluralist traits of all (future) governing parties (2000–2019) (x-axis) and V-Dem's Electoral Democracy Index the year after the election is negative.Footnote16 Thus, the more anti-pluralist parties appear before an election, the lower the level of democracy when they take or regain power. Lührmann, Medzihorsky and Lindberg demonstrate that this relationship in democracies holds in further statistical tests.Footnote17

Figure 2. Anti-pluralist party traits and electoral democracy (2000–2019).

Note: The Electoral Democracy Index ranges from 0 (not democratic) to 1 (fully democratic). The Anti-Pluralism Index ranges from 0 (pluralist) to 1 (anti-pluralist). N = 682.

Some parties have demonstrated unequivocally anti-pluralist positions from early on, such as the Fifth Republic Movement (MVR), which brought Chavez to power in Venezuela in 1998 and later evolved into the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) (black circles on the right). The story is different for the Fidesz Party in Hungary (dashed line) and the AKP in Turkey (grey line with triangle markers), which only gradually became more anti-pluralist and subsequently eroded democratic institutions step-by-step. In other cases, new party leaders or leading candidates have shifted their party into an anti-pluralist direction, such as Donald Trump in the United States in 2016 (line with squares).

Such anti-pluralists often use populist rhetoric to claim that they – and only they – are the legitimate representatives of “the people” and that “the elites” are not to be trusted.Footnote18 While a certain degree of skepticism of elites may be healthy for a democracy, anti-pluralists use anti-elitism to undermine democratic political competition. They challenge the pluralist foundation of democracy, which embraces “that societies are composed of several social groups with different ideas and interests”.Footnote19 Such actors may gain votes, but should not gain democratic legitimacy in a normative sense, because their actions prevent citizens from exercising their democratic rights in the future.Footnote20

Stage 1: mounting citizens’ discontent with democratic parties and institutions

Democracies are consolidated if democracy is the “only game in town”.Footnote21 Thus, support for democracy among elites and citizens is conducive to democratic resilience. Elites tend to support democratic norms if they trust political opponents to play by the rules as well.Footnote22 Such mutual trust is limited in countries with weak democratic institutions and a history of autocratization. This might explain why autocratization is more likely in such countries, as Boese et al. demonstrate in this issue.Footnote23

Contemporary autocratizers typically come to power through popular vote and not military coups, which gives citizens an important role in autocratization processes. Citizens turn away from democratic parties and candidates for two reasons: firstly, out of discontent with the way democratic governments and parties perform (a lack of specific support); secondly, because they are explicitly discontented with basic democratic norms and procedures (a lack of diffuse support).Footnote24 These sources of discontent can be interrelated and reenforce each other. For instance, declining specific support may activate already existing diffuse non-support.

Rising discontent with democratic options increases the demand for alternatives, but by far not all discontented citizens vote for anti-pluralist parties and candidates. Therefore, it is also important to understand the supply side and how anti-pluralist parties mobilize voters, which will be the focus of the next section (Stage 2).

Declining specific support: insufficient supply of effective democratic responses to structural and contextual challenges

Dissatisfaction with the performance of democratic governments and parties is a major source of discontent with democracy.Footnote25 Petrarca et al. have demonstrated a clear empirical link between declining trust in government institutions and a decline in vote share for established parties, which “opens a window of opportunity for challenging outsider parties”Footnote26 such as the Populist Radical Right. Low and declining public trust in institutions increases the probability of regime change from democracy to autocracy as well as the other way around.Footnote27

Such dissatisfaction and lack of trust can be due to the actual failure of governments to respond to new structural or contextual challenges or due to the mere perception that they have failed to do so. As Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser summarize the state of the research in this issue, many contemporary supporters of anti-pluralist parties “are not predominantly ‘economic losers’ in an objective sense, but individuals who at the subjective level feel left behind because of ongoing cultural and economic transformations that negatively affect their social status”.Footnote28 Historical comparative studies show that economic recession,Footnote29 weak economic development,Footnote30 corruption,Footnote31 and inequalityFootnote32 predict democratic discontent and – further down the line – autocratization. Thus, policies which effectively address such grievances can be seen as fostering democratic resilience.

At the same time, we are witnessing tectonic shifts in the social fabric of our societies.Footnote33 The labour market has become more flexible and the economy globalized. Ways of life are more individualized and less pre-determined. Two-dimensional party systems are a consequence of these developments: economic status matters less in how people vote while the salience of cultural issues has increased.Footnote34 The Internet has revolutionized the way we communicate and form political opinions and has opened the door for disinformation. At the same time, traditional “gatekeepers” of the political system – newspapers and established political parties – have lost much of their power.Footnote35

Thus, many analysts view the rise of anti-pluralist parties as a symptom of the failure of established democratic parties “to adapt to [this] new social reality”.Footnote36 After they have de-aligned with established parties, some voters realign with new parties.Footnote37 This creates a window of opportunity for anti-pluralist mobilization. Historically, similar processes have occurred. For instance, Cornell, Møller and Skaaning attribute democratic resilience in Denmark and United Kingdom during the interwar years to “the ability of conventional parties to channel the frustrations resulting from the repeated interwar crisis episodes”.Footnote38

A lack of diffuse support for democratic norms: a driver for autocratization?

We have strong evidence that citizens with weak commitment to democratic norms – those who show a lack of support for democracy,Footnote39 and exhibit authoritarian valuesFootnote40 and populist attitudes – are more likely to vote for anti-pluralists.Footnote41 In Germany for instance, 75% of the voters for the anti-pluralist party AfD approve of law-and-order authoritarianism, racism and evince distrust in democracy.Footnote42 However, such attitudes have not increased in the German population since 2014 – unlike the AfD's share of the vote.Footnote43

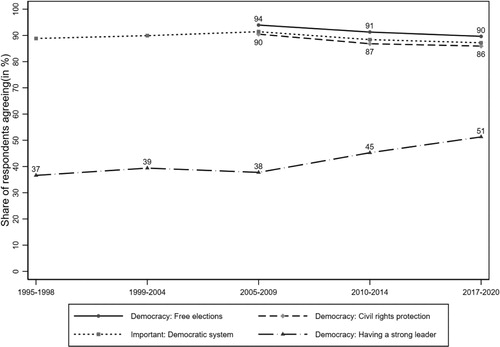

Globally, there is mixed evidence on the development of democratic values. Christian Welzel shows in this issue that mass support for democracy has increased in many more countries (26) than it declined in (14) from the third round (1994–98) of the World Value Survey (WVS) to the seventh round (2017–20).Footnote44 shows that the share of citizens supporting a democratic system has remained at the consistently high level of around 90% in democracies since the 1990s (small-dashed line).Footnote45 Other surveys paint a similar picture. For instance, it remains “absolutely” important for 52% of EU citizens to live in a democracy and not important for only 3.5%.Footnote46

Figure 3. The attitude of citizens living in a democracy towards democracy since the mid-1990s (WVS). Source: Inglehart et al., “World Values Survey”. Includes only citizens in countries classified as democracies at the beginning of the WVS wave by the Regimes of the World measure. Coppedge et al. “V-Dem dataset V10.”

However, at the same time, some of these respondents might be “democrats in name only”.Footnote47 For instance, support for “strong leaders who do not have to bother with parliaments and elections” has increased by 14% – from 38% in the 2005–2009 wave to 51% in 2017–2020 (dashed/dot line ).Footnote48 Nevertheless, 90% of WVS respondents continue to value free elections as an important part of democracy (black line). They even support a key principle of liberal democracy: that the protection of civil rights is “essential” (dashed line).Footnote49 Complementing this evidence, Christian Welzel points out in this issue that “emancipative values” – gender equality, child autonomy, public voice and reproductive freedoms – have been globally on the rise.Footnote50

Strengthening citizens’ support for democracy to enhance democratic resilience

While we do not have clear evidence for a drastic decline in global commitment to democratic norms, citizens with a weak commitment to democratic norms are more likely to vote for anti-pluralists. The average vote share for anti-pluralist parties in the world's democracies has increased from 17.8% in the period 1994–98 to 22.7% in 2016–19.Footnote51 What explains this? In the literature, we find four hypotheses: rollback due to over-liberalization; activation of authoritarianism; rising protest vote; and ignorance of democratic threats. How can such insights help to strengthen democratic resilience?

In this issue, Christian Welzel argues that some of the recent processes of autocratization such as in Poland and Hungary, are the result of an over-liberalization of the regimes. He argues that prior to autocratization, these regimes had liberalized more than the advancement of emancipative values in their respective electorates would naturally support.Footnote52 Skilful demagogues may intuitively capture and capitalize on such misalignments between values and the regime and use such window of opportunity for autocratization.Footnote53 Emancipative values are fostered by modernization – “rising living standards, falling mortality rates, dropping fertility rates as well as expanding education”.Footnote54 Such existential conditions are improving across the world – a further increase in emancipative values is likely to follow the same pattern, which might be conducive to re-democratization.Footnote55

The activation hypothesis claims that the rise of anti-pluralist parties is (partially) due to their mobilization of previously unaligned voters.Footnote56 These could be voters who lack a commitment to democratic norms. For example, as Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser summarize in this special issue, the Populist Radical Right (PRR) combines populism and anti-pluralism/authoritarianism with nativism – the longing for a homogenous nation state.Footnote57 Malka et al. show that cultural conservativism and authoritarian attitudes are closely related.Footnote58 Thus, the cultural conservative agenda of anti-pluralists such as Victor Orbán might have activated such voters. Furthermore, anti-immigration policies and euro-skepticism matter a lot to the voters for these parties.Footnote59

In response to such challengers, pro-democratic actors have to avoid merely enhancing the salience of those issues that many voters attribute anti-pluralist parties as having the main competence in – such as immigration.Footnote60 Attempts of centre parties to adopt a tough stance on immigration typically do not result in electoral success.Footnote61 On the contrary, such parroting maneuvers might actually undermine the credibility of centre parties while at the same time risk strengthening the anti-immigration agendas of anti-pluralist parties.Footnote62

At the same time, some citizens turn away from democratic parties in protest against the way democratic parties and governments perform and not because of a lack of support for democratic norms.Footnote63 Those who think that politicians do not represent their views are more likely to be dissatisfied with democracy. A meta-study of 3,500 country surveys reported that, globally, the proportion of citizens dissatisfied with the performance of democracy rose by 10% between 1995 and 2019, from 48% to 58%.Footnote64

Thus, it is paramount that democratic parties get better at responding to legitimate grievances and societal changes. To revitalize democratic parties, Bertoa and Rama propose a potpourri of remedies: building new and strong party organizations which capitalize on new technologies; leadership by example and without corruption; and embracing the democratic imperative of consensus.Footnote65 Others suggest that democratic parties should appeal more to the emotions and show empathy towards those people who feel that globalization and cultural modernization has devalued their experience and accomplishments.Footnote66

Nevertheless, the question remains: Why would citizens who support democratic norms in principle jeopardize them by voting for anti-pluralist parties? Here the literature holds several answers, which can be summarized as ignorance out of a lack of awareness, knowledge or alternative priorities. Citizens might prioritize other issues such as anti-abortion, their economic situation, and anti-immigration policies. They might not be aware that a party or politician has anti-pluralist tendencies or they might not recognize anti-pluralism as a threat to democracy. Many citizens hold a majoritarian view of democracy, thinking that democracy simply means the majority should get what they want (and they also often falsely assume that the majority wants the same as them).Footnote67 For example, 41% of US citizens support the notion that the US President should act without bothering with institutional procedure if “a large majority of the American people believe the president should act”.Footnote68 Furthermore, anti-pluralist actors turn the political contest into an “us-versus-them” game where their ideological wins are perceived as more important than democratic norms.Footnote69 Such pernicious polarization increases apathy in relation to authoritarian and illiberal behaviour.Footnote70 For instance, in several survey experiments, voters were shown to prioritize their ideological preferences over democratic norms in polarized societies.Footnote71

In order to foster democratic awareness, knowledge and commitment among ordinary citizens, civic education is an important tool.Footnote72 Civic education and engagement is a key pillar of external democracy promotion activities. Given the contemporary challenges, even established democracies could learn from these well-established methodologies.Footnote73 Therefore, this special issue features a study by Finkel and Lim demonstrating how a civic education programme in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) enhanced political participation in non-electoral activities, as well as knowledge and the feeling of efficacy and tolerance.Footnote74 They attribute the success to the programme's “active and participatory approach”.Footnote75 However, the programme also decreased support for democracy in the DRC and satisfaction with an ongoing decentralization programme. Such mixed effects are not uncommon.Footnote76 Finkel and Lim point out that in the studied case, civic education had fostered an understanding of what democracy and decentralization should look like – a normative ideal that did not match the dire realities of the DRC.Footnote77 Thus, they concluded that future programmes should better account for the “discrepancy between democracy in theory and in practice”.Footnote78

Stage 2: anti-pluralists rising to power

Discontent with democracy as such does not bring down democracies. Anti-pluralist political leaders or parties do. These actors skilfully claim to address democratic discontent while fuelling it, and mask their anti-democratic aspirations with populist rhetoric. They also fuel and benefit from polarization.

In democracies, most autocratizers come to power through free and fair elections.Footnote79 Thus, understanding how the electoral arena enables or constrains them is critical for blocking their access to power. The key variables here are the mobilization of voters – for the anti-pluralist challenger as well as for democratic parties and the institutions and coalitions which translate votes into power.

Adept anti-pluralist parties: populist narratives for claiming legitimacyFootnote80

Populist rhetoric helps anti-pluralists to conceal how dangerous their ideas are for democracy. As discussed earlier, they claim to stand for “true democracy” while their actions are likely to undermine it. To a limited extent, the totalitarian movements of the last century shared such populist traits and appealed to legal justifications.Footnote81 As Hannah Arendt noted, both fascists and communists “use[d] and abuse[d] democratic freedoms in order to abolish them”.Footnote82

Many anti-pluralist parties attract voters beyond a radical base by avoiding explicit autocratic statements. Consequently, their parties suffer from internal tensions between such reformers aiming at broad coalitions and radicals prioritizing protest.Footnote83 Grahn, Lührmann and Gastaldi show that the demise of European far right parties has occurred mainly due to internal factors such as “internal splits, changes in leadership and corruption scandals”.Footnote84 The authors recommend that democratic actors should amplify such scandals and internal conflicts and “develop creative strategies” seeking to deepen divisions within anti-pluralist parties.Footnote85 This includes parliamentary initiatives that force MPs of anti-pluralist parties to show their true colours, e.g. their views on the Nazi regime. Others suggest the toolkit of a “militant democracy”: “pre-emptive, prima facie illiberal measures to prevent those aiming at subverting democracy with democratic means from destroying the democratic regime”.Footnote86 Such reasoning builds on Karl Popper's “paradox of tolerance”: If a tolerant society tolerates the intolerant, the latter will eventually undermine the foundations of tolerance.Footnote87 In effect, the constitutions of many democracies – most conspicuously Germany – include measures allowing constitutional courts to subdue actors and behaviour that would undermine the liberal order; for instance banning extremist parties. Repressive strategies include “hard” responses such as party/organization bans, prosecution and surveillance, but also “softer” strategies such as state officials excluding anti-pluralistic organizations and teachers.Footnote88

Such measures are often not effective in containing contemporary challengers of democracy, who conceal an anti-democratic agenda behind a populist façade and thus do not meet the legal criteria for the application of such measures. Furthermore, critiques of militant democracy fear that governments will use such measures not to defend democracy, but to subvert it.Footnote89 Juan Linz rightly worries that indiscriminate, exclusionary measures might push supporters of anti-pluralist actors more into their arms.Footnote90 Thus, they may foster polarization.

The accelerator: pernicious polarization

Anti-pluralists – in particular populist ones – often use a stark rhetoric separating a society into the “people” (us), and its enemies (them). Ultimately, as Somer, McCoy and Luke point out in this special issue, “society is split into mutually distrustful us vs. them camps in which political identity becomes a social identity”.Footnote91 Such pernicious or “toxic polarization” goes beyond healthy, controversial debates about policy preferences and impedes trustful interactions between citizens with different points of views.

As Somer, McCoy and Luke emphasize, polarization is the result of a deliberate strategic choice of political actors to exploit and exaggerate pre-existing cleavages for their own political ends rather than an automatic consequence of such structural preconditions.Footnote92 Two or more sides may intentionally foster polarization. It may also occur “asymmetrically,” that is, be pushed from only one side as in recent years in the US, where Republicans increasingly placed their own political ends over democratic norms.Footnote93 However, democratic actors may also foster a vicious circle of polarization by mounting vigorous counterattacks.Footnote94

In this issue, Somer, McCoy and Luke show, using a cross-national data set (1900–2019), that countries that are more polarized are more likely to autocratize.Footnote95 Thus, polarization seems to be a key accelerating factor in the autocratization sequence. It helps anti-pluralists to fuel discontent with democratic parties, and muster support.

Furthermore, supporters of polarizing political leaders tend not to trust information from a non-partisan or opposing source, and they communicate less with people with opposing views.Footnote96 Arendt observed similar processes when studying the supporters of totalitarian movements.Footnote97 The social media algorithms aggravate this problem.

Democratic actors have to be aware of such toxic dynamics of pernicious polarization and address them thoughtfully in order to disrupt the autocratization sequence.Footnote98 This does not imply that both sides are the culprits for democratic malaise. Furthermore, addressing polarization does not imply avoiding polarizing policy debates at all costs. On the contrary, “transformative repolarization” may be successful if it “seeks to change the axis of polarization away from the Manichean line emphasized by the polarizing incumbent and toward one that is more flexible and programmatic, such as those based on democratic or social justice principles”.Footnote99 For example, the successful protest movement in South Korea in 2016–17 moved the cleavage from “conservative vs. liberal” to “executive accountability vs. corruption/authoritarianism” with the help of innovative methods.Footnote100

In other cases, “active depolarization” has been successful: social and political action which places new issues on the political agenda and forges new alliances, cutting across the polarizing cleavage.Footnote101 Similarly, Norris and Inglehart stress that “[polarization] calls above all for leaders who can help to bridge divisions – and not exacerbate them”.Footnote102 Such strategies have contributed to the 2019 opposition victories in local elections in Turkey and Hungary.Footnote103 Conversely, reactive strategies such as “reciprocal polarization” along the same cleavage entail the risk of backfiring as in Turkey in 2007 and 2008, and in Venezuela in recent years.Footnote104

Thus, the key to hindering pernicious polarization is increasing unity and common ground through the invention of “communication tools, campaign strategies and alliances with social movements and civic organization, recruitment methods, use of emotion and symbols, and narratives”.Footnote105

The electoral arena: voter mobilization and coalition building

Anti-pluralist parties polarize, which limits their potential to mobilize voters. Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser analyse such “electoral ceilings” for the case of the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe in this special issue.Footnote106 They conclude that in 2019 about 50% of the electorate clearly opposed such parties – in Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser's words thy had a “negative identity” towards them – while only about 10% identify positively with the parties of that family.Footnote107 At the same time, citizens who support such parties are somewhat more likely to actually vote than those with a negative identity (83% versus 76%).Footnote108 Thus, while the potential for electoral success for the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe is limited, specific electoral outcomes depend on who mobilizes their support base better: democratic parties or anti-pluralists.

The rejection of anti-pluralists can be important in mobilizing the democratically-minded voters.Footnote109 Strategies of passive depolarization run the risk of demobilizing them.Footnote110 The 2020 US election has demonstrated once more how critical electoral mobilization is. While Donald Trump mobilized more voters than in 2016 (from 63 million to 74 million); Joe Biden won because the Democratic vote increased even more (from 66 million in 2016 to 81 million in 2020).Footnote111 For many Biden voters, preventing four more years of Donald Trump was an important argument.Footnote112 Thus, counter-mobilization may give democratic parties an electoral advantage.Footnote113 However, it also runs the risk of increasing the salience of anti-pluralist agendas, which can be avoided by appealing to a broad base and cutting through polarizing cleavages.

To what extent votes translate into political power depends on the electoral system. While several studies have pointed to presidential systems being more prone to autocratization,Footnote114 the effects of specific electoral rules have not been systematically tested. The exception is perhaps the introduction of a minimal threshold for achieving parliamentary representation, which is said to preserve the parliamentary capacity to act by avoiding fractionalization.Footnote115

Issues of institutional design are relevant to consider for long-term reform processes. In the short-term, after elections in systems with proportional representation, parties between the centre and the extremes (“border parties”) can become “king-makers” as they choose between a coalition of democratic parties or one with anti-pluralists. If their main strategic goal is vote maximization, they are likely to “follow their voters” and move towards the extremes.Footnote116

Some scholars argue in favor of accommodating anti-pluralist parties in coalitions. Such parties might perform badly in government with mundane issues (such as “fixing potholes”Footnote117), distracting them from their radical policies. This might disappoint their support base and eventually present the anti-pluralist party with the choice of leaving government or losing electoral support.Footnote118 Other scholars suggest that inclusion in government forces such parties to deradicalize.Footnote119 However, in several cases such deradicalization has not materialized.Footnote120 Even parties that became slightly less radical while in office re-radicalized as soon as they joined the opposition again.Footnote121

In Europe in the 1920s to 1930s, the accommodation of anti-pluralists – intended to keep them under control – enabled them to dominate government.Footnote122 Similarly, in already autocratic settings, the cooptation of democratic parties has cemented dictatorships multiple times, e.g. in Kenya and Zimbabwe.Footnote123 Some pact transitions (e.g. in Chile after 1989) and the broad-based coalition in post-revolutionary Tunisia were perhaps more positive for democratization.Footnote124

Critical engagement: addressing polarization and the legitimacy claims of anti-pluralists

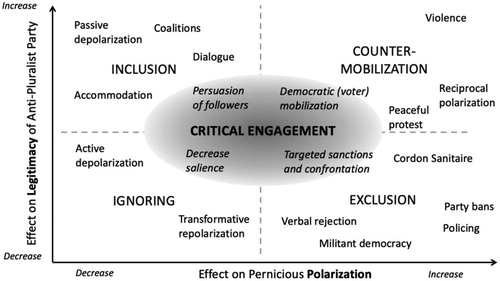

Anti-pluralists claim to be democratically legitimate, while at the same time fuelling pernicious polarization. This creates a strategic dilemma for democratic actors (see ). Democratic responses may have contrary effects on the legitimacy of anti-pluralists (y-axis) and on pernicious polarization (x-axis).

On the one hand, democratic actors aim to signal clearly that anti-pluralists are not legitimate actors in a democratic sense, because while they may gain some electoral support, they are not playing by democratic rules. To achieve such an aim, a strategy of exclusion seems promising – placing anti-pluralists in a “cordon sanitaire” to limit their agenda-setting powerFootnote125 and using the tools of militant democracy discussed above such as party bans (low-right quadrant). On the other hand, such measures may fuel the vicious circle of pernicious polarization. Actors aiming to prevent this from happening often call for a more inclusionary approach of accommodation, which could help to depolarize societies (top-left quadrant).Footnote126 However, by tolerating them or even forming a coalition with anti-pluralists, democrats give such actors a veneer of democratic legitimacy – a gift, which they can scarcely take back.Footnote127

The aim of depolarization could also be fostered by a strategy of ignoring anti-pluralist provocations (low-left quadrant). This avoids anti-pluralists framing themselves as “victims” of the establishment.Footnote128 Similarly, Somer, McCoy and Luke discuss in this issue various strategies for reducing the salience of the polarizing divide with “active depolarization” and “transformative repolarization” (see above).Footnote129 The downside of such activities is that they might not actively challenge the legitimacy of anti-pluralists at least in the short term. In the long run, they might decrease anti-pluralist legitimacy by reducing the salience of the issues that render them legitimate in the eyes of their supporters in the first place. Conversely, extreme counter-mobilization strategies (top-right quadrant), such as “fighting fire with fire”Footnote130 with violent counter-attacks, intend to delegitimize anti-pluralists but might actually enhance their legitimacy by creating plausible victim narratives. They also risk fuelling polarization. Other types of counter-mobilization seem more suitable such as civic engagement and peaceful protest even though they may also fuel polarization.

An effective strategy of democratic resilience could use “critical engagement” as a leitmotif combining the advantages of all four response strategies while avoiding their pitfalls. Targeted sanctions and confrontation use the exclusionary tool kit of militant democracy, including policing, party-bans, and verbal delegitimization, but focus interventions on the most radical anti-pluralists and in particular their leaders.

Thus, pro-democratic actors should only engage in measures that suppress anti-pluralist actors if there is clear evidence that they threaten the democratic order and that such tools are proportionate and effective. Trusted arbiters such as courts can help to differentiate between what is legitimate opposition within a democratic system and what is undemocratic and thus illegitimate.Footnote131 In particular, it is important to differentiate between the threat posed by groups and individuals.Footnote132 Arguably, the threat level posed by an organized group is higher than the danger posed by individual citizens. Thus, while some anti-pluralist groups and group activities could be the subject of militant measures, societies should avoid actions that “vilify supporters” of anti-pluralists.Footnote133

Persuasion aims at convincing moderately illiberal citizens that democratic values and institutions work for them; and at unifying people around what they have in common. Linz suggests that such “semi-loyal” actors should be integrated as much as possible.Footnote134 On their own, authoritarian radicals are rarely able to take and sustain power in a democracy. They need the support or at least toleration of more moderately-oriented reformers within their party or other parties or groups in society.Footnote135 A source of democratic resilience is thus to drive a wedge between those groups. Such a strategy needs to make it more attractive for reform-oriented followers of anti-pluralist groups to turn towards democratic alternatives than to stay with the anti-pluralists. This includes engaging in dialogue, a more attractive supply of democratic candidates, and fostering civic education, and, for potential defectors from authoritarian governments, guarantees for future participation.

However, many polarizing actors use deliberate lies, disinformation and hatred to advance their agendas. Merely talking risks legitimizing and amplifying such narratives. In public debates, red lines need to be drawn to protect minorities and separate facts from lies. At the same time, democratic actors should not mirror unfair and aggressive tactics.Footnote136 Rather, as Michele Obama put it in 2016 “when they go low, we go high” should be the leitmotif. For instance, in Slovakia, Caputova won the 2019 presidential elections against a severely polarizing incumbent while not engaging in demonization and disinformation due to support from civil society and his focus on anti-corruption.Footnote137

Such democratic mobilization demonstrates the strength of the democratic side of the political spectrum and creates the momentum for democratic candidates to win elections. Democratic mass protests and civic engagement can also help to educate citizens about democratic values and processes while creating spaces for democrats to collaborate.Footnote138 At the same time, democratic mobilization should avoid merely reacting to anti-pluralists’ provocations along the polarizing cleavage in order to decrease the salience of the issue “owned” by anti-pluralists (e.g. immigration).

Stage 3: autocratizers dismantle democratic institutions

Boese et al. show that resilience to democratic breakdown, or breakdown resilience – limiting the extent to which autocratization damages democratic institutions – is contingent on several factors.Footnote139 Strong institutions of accountability and democratic experience (“democratic stock”) make such breakdown less likely.Footnote140 This applies in particular for judicial constraints, but not for the role of the legislature – at least not on average.Footnote141

In individual cases, the parliament has been relevant for breakdown resilience for instance when the South Korean legislature impeached then-president Park Geun-heye in 2017.Footnote142 However, the legislature responded mainly because other accountability actors – civil society and the media – mounted pressure and public opinion turned against Park Geun-heye after a major corruption scandal came to light.Footnote143

Therefore, Laebens and Lührmann argue that accountability mechanisms – constraints on the power of the executive – are key for breakdown resilience.Footnote144 This includes: parliamentary and judicial oversight and an independent administration (horizontal accountability), pressure from civil society and the media (diagonal accountability), and electoral competition between parties and within parties (vertical accountability).Footnote145 Such mechanisms may halt autocratization if multiple accountability actors work together and contextual factors shift the “balance of power between the incumbent and accountability actors”.Footnote146

Such contextual factors include corruption scandals, economic downturns and approaching term of office limits, but only if the opposition or intra-party elites exploit them for mobilization against the incumbent. Thus, “creative” opposition strategies are critical, particularly during advanced stages of autocratization, where formal accountability institutions may not be independent, but still be perceived as legitimate.Footnote147 As Boese et al. demonstrate, democracies are more likely to break down the longer the autocratization process lasts.Footnote148 Therefore, a quick response is of the essence.

Conclusions

Democracies typically do not die overnight. Contemporary autocratization is typically the result of a long sequence of events and processes – ranging from mounting discontent with democratic institutions and parties, to anti-pluralists rising to power, to the failure of accountability constraints. The articles assembled in this special issue shed light on specific stages in this autocratization sequence.

The good news is that each step along this sequence is also an entry point for enhancing democratic resilience. While no “silver bullet” exists, democratic actors – citizens, politicians, civil servants – have many options to choose from.Footnote149 As Boese et al. show in this issue, only one in five democracies survive autocratization once it has started.Footnote150 Thus, the most important avenue for democratic resilience is preventing it from starting.

For such onset resilience, firstly, democratic actors need to avoid discontent with democratic institutions and parties. Here, the most important parameter seems to be an attractive supply of democratic parties and politicians that address structural and contextual challenges as well as organize inclusive and participatory political processes. The latter gives citizens a sense of political efficacy, which enhances support for democratic norms. If the gap between democratic ideals and reality is wide, the effects of civic education on support for democracy are limited.Footnote151 Thus, an inclusive, participatory, and effective political process also enhances the effectiveness of civic education, which in general should be expanded in order to foster support for democratic norms.

Secondly, as democratic actors try to block anti-pluralists’ access to power, they face several dilemmas: Should they choose exclusionary approaches and risk fuelling pernicious polarization; or inclusionary approaches, which might give anti-pluralists a veneer of undeserved legitimacy? Should they ignore anti-pluralist provocations or rather counter-mobilize? Based on the articles assembled in this special issue and other research, I suggest balancing the advantages and pitfalls of conventional approaches with a strategy of critical engagement. Borrowing from exclusionary strategies, targeted sanctions and confrontation could limit the reach of the most radical anti-pluralist actors, groups and causes. At the same time, the inclusionary idea that more moderate followers could be persuaded to follow democratic causes might have some merits, while coalitions with anti-pluralists appear too risky. Finally, it seems important to decrease the salience of anti-pluralist issues and campaigns while at the same time mobilizing democratic citizens for elections, peaceful protest and civic engagement. Here, it is important to build shared values, visions and priorities, which cut through polarizing cleavages.

Once an anti-pluralist has come to power, institutional constraints and skilful opposition strategies may limit the extent of autocratization. To build such breakdown resilienceFootnote152 it seems advisable to enhance the independence and strength of judicial oversight, of public administration, the media and civil society.

Future research needs to empirically test the notions presented here more extensively, in particular regarding the effects of democratic strategies vis-à-vis anti-pluralists. Multiple bottlenecks and circles of reverse causality make such endeavors challenging, but data availability has improved in recent years, – for instance with the V-Dem and V-Party datasets.Footnote153 The list of factors contributing to the autocratization sequence addressed in this special issue is explicitly not exhaustive. For instance, we have not addressed how the rise of social media relates to processes of autocratization and how online debates could become more civil and fact-based. Future studies should shed light on this important topic. The same applies to international factors. To foster democratic resilience, “democracy protection”Footnote154 needs to happen across borders.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the authors of this issue as well as Paulina Fröhlich, Christal Morehouse, Bernhard Wessels, Daniel Ziblatt, participants at the Berlin Democracy Conference (11/2019), V-Dem research seminar (2/2021) and Cornell University's Peace and Conflict Studies Institute's reading group (2/2021) for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article and inspiring discussions. I highly appreciate the skilful research assistance of Lisa Gastaldi, Sandra Grahn, Dominik Hirndorf, Palina Kolvani, Martin Lundstedt, and Shreeya Pillai.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Lührmann

Anna Lührmann is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg and Senior Research Fellow at the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem). Her research on autocratization, elections and democracy aid has been published among others in American Political Science Review, Electoral Studies, International Political Science Review, and the Journal of Democracy.

Notes

1 For excellent reviews see: Waldner and Lust, “Unwelcome Change”, Hyde, “Democracy's Backsliding.”

2 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?,” 2.

3 Lührmann, Medzihorsky and Lindberg, “Walking the Talk,” 9. Anti-pluralism is a contested notion that not both editors of this issue agree to.

4 Welzel, “Democratic Horizons.”

5 Finkel and Lim, “The Supply and Demand Model.”

6 Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Negative Partisanship.”

7 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization.”

8 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?.”

9 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail.”

10 Merkel and Lührmann, “Introduction.”

11 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem.” Lührmann et al. “V-Party.”

12 See next section, contributions to this issue and Waldner and Lust, “Unwelcome Change.”

13 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail.”

14 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?.”

15 Lührmann, Medzihorsky and Lindberg, “Walking the Talk.”

16 The Pearson's correlation of −0.83 is statistically significant. On the Electoral Democracy Index see Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Dataset v10.” Ruling parties are identified in the V-Party data set by the variable v2pagovsup. Lührmann et al., “V–Party Dataset.” Both datasets rely on expert coding, which is aggregated by a custom-built measurement model to enhance comparability across countries and time. Pemstein et al., “V-Dem Measurement Model.”

17 Lührmann, Medzihorsky and Lindberg, “Walking the Talk,” 9.

18 Populism as such is a contested concept. For more detail, see Melendez and Rovira Kaltwasser's article in this special issue.

19 Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism”, 152.

20 For a similar argument, see Karl Popper's work on the paradox of freedom (1945/2003, 130).

21 Linz and Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation.

22 Przeworski, Sustainable Democracy, 11; Dahl, Polyarchy, 40.

23 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail,” 19.

24 On the difference between specific and diffuse support, see Easton, “A Re-assessment.”

25 On the link between perceived government performance and democratic discontent, see Dahlberg, Linde, and Holmberg, “Democratic Discontent.”

26 Petrarca, Giebler, and Weßels. “Support for Insider Parties,” 1.

27 Ruck, Matthews and Kyritsis, “Cultural Foundations.”

28 Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Negative Partisanship,” 11, emphasis mine. On status anxiety, see also Gidron and Hall, “The Politics of Social Status.”

29 Bernhard, Nordstrom, and Reenock, “Economic Performance.”

30 Svolik, “Authoritarian Reversals”; Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development.

31 Dahlberg, Linde, and Holmberg, “Democratic Discontent.”

32 Leininger, Lührmann, and Sigman, “The Relevance of Social Policies”; Haggard and Kaufman, Dictators and Democrats.

33 See e.g. Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

34 Mair, Ruling the Void.

35 Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die, 55–6.

36 Casal Bertoa and Rama, “The Antiestablishment Challenge,” 40. See also: De Vries and Hobolt, Political Entrepreneurs.

37 Mair, Ruling the Void; Hooghe and Marks, “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe's Crises.”

38 Cornell, Møller and Skaaning, Democratic Stability, 12.

39 Todd, “Authoritarian Attitudes.”

40 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash, 279; MacWilliams, “Trump Is an Authoritarian.” https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/09/23/trump-america-authoritarianism-420681

41 Van Hauwaert and van Kessel, “Beyond Protest and Discontent.”

42 Zick, Küpper, and Berghan, “Verlorene Mitte.”

43 Ibid.

44 Welzel, “Democratic Horizons”, 13. See also Wuttke et al., “Grown Tired of Democracy?.”

45 Respondents viewing democracy as a “fairly” or “very” good way of “governing this country” (Inglehart et al., “World Values Survey”).

46 Schmitt et al., “European Parliament Election.”

47 Wuttke et al., “Grown Tired of Democracy?.”

48 Respondents viewing a “strong leader” as a “fairly” or “very” good way of “governing this country” (Inglehart et al., “World Values Survey”). See also Wuttke et al., “Grown Tired of Democracy?.”

49 Respondents selecting 5 or higher on a 0–10 scale.

50 Ibid., 6; Alexander and Welzel, “The Myth of Deconsolidation.”

51 This includes all parties scoring higher than 75% of the parties in democracies in this millennium on the V-Party Anti-Pluralism Index (0.4395). Lührmann et al. “V–Party Dataset.”

52 Welzel, “Democratic Horizons,” 6.

53 Ibid., 8.

54 Ibid., 9.

55 Ibid., 16–19.

56 Pardos-Prado, Lancee and Sagarzazu, “Immigration and Electoral Change.”

57 Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Negative Partisanship,” 3.

58 Malka et al., “Open to Authoritarian Governance.”

59 Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Negative Partisanship”, 13. Hainmueller and Hopkins, “Public Attitudes Toward Immigration.”

60 On issue ownership, see Pardos-Prado, Lancee, and Sagarzazu, “Immigration and Electoral Change.”

61 Abou-Chadi and Wagner, “The Electoral Appeal”; Spoon and Klüver, “Responding to Far Right”; Hutter and Kriesi, “Politicising Immigration.”

62 Akkerman and Rooduijn, “Pariahs or Partners?”; Heinze, “Strategies of Mainstream Parties.”

63 Dahlberg, Linde, and Holmberg, “Democratic Discontent,” 24f.

64 Foa et al., “The Global Satisfaction with Democracy Report.”

65 Casal Bertoa and Rama, “The Antiestablishment Challenge,” 47f.

66 Urbanska and Guimond, “Swaying to the Extreme.” Wigura and Kuisz, The Guardian, 11 Dec 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/11/populist-politicians-power-emotion-loss-change.

67 In a survey experiment, Grossman et al. show that citizens often do not object to undemocratic actions by elected leaders. Grossmann et al., The Majoritarian Threat.

68 Drutman, “Democracy Maybe,” 5.

69 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization.”

70 See for example McCoy and Somer, “Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization.”

71 Svolik, “When Polarization Trumps”; Graham and Svolik, “Democracy in America?.”

72 Finkel and Lim, “The Supply and Demand Model.”

73 Thomas Carothers has made a similar call, see Foreign Policy, January 27, 2016; https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/01/27/look-homeward-democracy-promoter/

74 Finkel and Lim, “The Supply and Demand Model.”

75 Ibid., 18.

76 Ibid., 2.

77 Ibid., 18.

78 Ibid., 18.

79 Medzihorsky, Lührmann, and Lindberg, “Autocratization by Elections.”

80 For similar arguments see Lührmann et al., Resource Guide.

81 Linz, The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes; Cavazza, “War der Faschismus populistisch?.”

82 Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 312.

83 See, for example, Schroeder and Weßels, Smarte Spalter.

84 Grahn, Lührmann and Gastaldi, “Resources for Democratic Politicians,” 53.

85 Ibid., 53. Downs recommends a similar approach, see Downs, “How Effective Is the Cordon Sanitaire?,” 49.

86 Müller, “Militant Democracy,” 1253.

87 Popper, Open Society, 293.

88 Müller, “Protecting Popular Self-government.”

89 For a detailed discussion of this controversy, see Müller, “Militant Democracy.”

90 Linz, The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes.

91 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 1.

92 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 6.

93 Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die.

94 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 6.

95 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 8.

96 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 12.

97 Members of a totalitarian movement are “well-protected against the reality of the non-totalitarian world” (Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 367).

98 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 28.

99 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 19.

100 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 21. See also Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”

101 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 19.

102 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash, 265.

103 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 22, 26.

104 Ibid., 14–15; Cleary and Öztürk, “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown?”; On Venezuela see also: Rovira Kaltwasser, “Populism,” 502.

105 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 19–20.

106 Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, “Negative Partisanship.”

107 Ibid., 14.

108 Ibid., 13.

109 Ibid., 14.

110 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 18.

111 CNN, 2016; https://edition.cnn.com/election/2020/results/president; https://edition.cnn.com/election/2016/results

112 Forbes, August 13, 2020; https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackbrewster/2020/08/13/poll-56-of-biden-voters-say-theyre-voting-for-him-because-hes-not-trump/?sh=2ba442266132

113 See Grahn, Lührmann, Gastaldi, “Resources for Democratic Politicians”; Müller, What Is Populism?, 84.

114 Linz, The Perils of Presidentialism; Stepan and Skach, “Constitutional Frameworks”; Washington Post, February 4, 2021; Carey, “Did Trump Prove.”

115 Carey and Hix, “The Electoral Sweet Spot.”

116 Capoccia, Defending Democracy, 17 (based on Sartori).

117 Berman, “Taming Extremist Parties.”

118 Heinisch, “Success in Opposition.”

119 Ibid., Berman, “Taming Extremist Parties.”

120 Akkerman and Rooduijn, “Pariahs or Partners?”; Akkerman, “Conclusions,” 279.

121 Akkerman, “Conclusions,” 276.

122 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 16. Casal Bertoa and Rama, “The Antiestablishment Challenge,” 40; Grahn, Lührmann, Gastaldi, “Resources for Democratic Politicians.”

123 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 16.

124 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 16–17.

125 Norris, Radical Right; van Spanje, “Contagious Parties,” 485; Minkenberg, “The Radical Right.”

126 Heinze, “Strategies of Mainstream Parties”; Downs, “Pariahs in their Midst”; Grahn, Lührmann, Gastaldi, “Resources for Democratic Politicians.”

127 Heinze, “Strategies of Mainstream Parties.”

128 However, anti-pluralists may use such narratives even if they are in government – think about Donald Trump.

129 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 12–15.

130 See Rovira Kaltwasser, “Populism,” 489–503.

131 Linz, The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes.

132 See also Müller, “Protecting Popular Self-government”; Popper, Open Society, 293; Lührmann et al., Resource Guide, 19.

133 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 14.

134 Linz, The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes, 34.

135 See for example Bermeo, Ordinary People in Extraordinary Times; Ziblatt, Conservative Parties.

136 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 14.

137 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 14.

138 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash; Bermeo, “Reflections.”

139 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail.”

140 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail,” 19.

141 Ibid.;. Staton, Reenock and Holsinger, Can Courts be Bulwarks of Democracy?

142 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”

143 Ibid., 11–12.

144 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?”

145 On the concept of accountability see Lührmann, Marquardt and Mechkova, “Constraining Governments.”

146 Laebens and Lührmann, “What Halts Democratic Erosion?,” 15.

147 Somer, McCoy and Luke, “Pernicious Polarization,” 14, 15.

148 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail.”

149 For an overview of options see Lührmann et al., Resource Guide.

150 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail,” 1.

151 Finkel and Lim, “Supply and Demand Model.”

152 Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail.”

153 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Dataset v10”; Lührmann et al., “Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V–Party) Dataset.”

Bibliography

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Michael Wagner. “The Electoral Appeal of Party Strategies in Post-Industrial Societies: When Can the Mainstream Left Succeed?” The Journal of Politics 81, no. 4 (2019): 1405–1419.

- Akkerman, Tjitske. “Conclusions.” In Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe, edited by Tjitske Akkerman, Sarah L. De Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn, 268–282. Oxon: Routledge, 2016.

- Akkerman, Tjitske, and Matthijs Rooduijn. “Pariahs or Partners? Inclusion and Exclusion of Radical Right Parties and the Effects on Their Policy Positions.” Political Studies 63, no. 5 (2015): 1140–1157. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12146.

- Alexander, Amy C., and Christian Welzel. “The Myth of Deconsolidation: Rising Liberalism and the Populist Reaction”. Journal of Democracy: online debate forum (2017). https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exchange-democratic-deconsolidation/.

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1951.

- Berman, Sheri. “Taming Extremist Parties: Lessons from Europe.” Journal of Democracy 19, no. 1 (2008): 5–18. doi:10.1353/jod.2008.0002.

- Bermeo, Nancy. Ordinary People in Extraordinary Times: The Citizenry and the Breakdown of Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Bermeo, Nancy. “Reflections: Can American Democracy Still Be Saved?” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no. 1 (2019): 228–233. doi:10.1177/0002716218818083.

- Bernhard, Michael, Timothy Nordstrom, and Christopher Reenock. “Economic Performance, Institutional Intermediation, and Democratic Survival.” The Journal of Politics 63, no. 3 (2001): 775–803. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2691713.

- Boese, Vanessa A., Amanda B. Edgell, Sebastian Hellmeier, Seraphine F. Maerz, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “How Democracies Prevail: Democratic Resilience as a Two-Stage Process.” Democratization 5 (2021): 1–23.

- Capoccia, G. Defending Democracy: Reactions to Extremism in Interwar Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. doi:10.1353/book.3332.

- Carey, John. “Did Trump Prove that Governments with Presidents Just Don’t Work?” Washington Post (4 Feb 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/did-trump-prove-that-governments-with-presidents-just-dont-work/2021/02/04/9e9c69f2-5f3f-11eb-9430-e7c77b5b0297_story.html?fbclid=IwAR0sKpgvNSrxTKNozrljDuvRDhN6TmUZ3FuGo8LJck3wrEUK19Xps5ASXXM.

- Carey, John M, and Simon Hix. “The Electoral Sweet Spot: Low-Magnitude Proportional Electoral Systems.” American Journal of Political Science 55, no. 2 (2011): 383–397. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00495.x.

- Casal Bértoa, Fernando, and José Rama. “The Antiestablishment Challenge.” Journal of Democracy 32, no. 1 (2021): 37–51. doi:10.1353/jod.2021.0014.

- Cavazza, Stefano. “War der Faschismus populistisch? Überlegungen zur Rolle des Populismus in der faschistischen Diktatur in Italien (1922–1943).” Totalitarismus und Demokratie 9, no. 2 (2012): 235–256.

- Cleary, Matthew R., and Aykut Öztürk. “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown? Uncertainty and Opposition Strategies in Democracies at Risk.” Perspectives on Politics (2020): 1–17. doi:10.1017/S1537592720003667.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. “V-Dem Dataset v10.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute (2020). doi:10.23696/vdemds20, 2020.

- Cornell, A., J. Møller, and S. Skaaning. Democratic Stability in an Age of Crisis: Reassessing the Interwar Period. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Dahl, Robert A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Dahlberg, Stefan, Jonas Linde, and Sören Holmberg. “Democratic Discontent in Old and New Democracies: Assessing the Importance of Democratic Input and Governmental Output.” Political Studies 63 (2015): 18–37. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12170.

- De Vries, Catherine E., and Sara B. Hobolt. Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

- Donovan, Todd. “Authoritarian Attitudes and Support for Radical Right Populists.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 29, no. 4 (2019): 448–464. doi:10.1080/17457289.2019.1666270.

- Downs, William M. “How Effective Is the Cordon Sanitaire? Lessons from Efforts to Contain the Far Right in Belgium, France, Denmark and Norway.” Journal für Konflikt- und Gewaltforschung 4, no. 1 (2002): 32–51.

- Downs, William M. “Pariahs in Their Midst: Belgian and Norwegian Parties React to Extremist Threats.” West European Politics 24, no. 3 (2001): 23–42. doi:10.1080/01402380108425451.

- Drutman, Lee, Joe Goldman, and Larry Diamond. “Democracy Maybe. Attitudes on Authoritarianism in America.” Democracy Fund (June 2020). https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/democracy-maybe.

- Easton, David. “A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5, no. 4 (1975): 435–457. doi:10.1017/S0007123400008309.

- Finkel, Steven E., and Junghyun Lim. “The Supply and Demand Model of Civic Education: Evidence from a Field Experiment in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Democratization (2020): 1–22.

- Foa, Roberto Stefan, Andrew Klassen, Micheal Slade, Alex Rand, and Rosie Collins. “The Global Satisfaction with Democracy Report 2020.” Cambridge: Centre for the Future of Democracy, 2020.

- Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall. “The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right.” British Journal of Sociology 68, no. S1 (2017): S57–S84. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12319.

- Graham, Matthew H., and Milan W. Svolik. “Democracy in America? Partisanship, Polarization, and the Robustness of Support for Democracy in the United States.” American Political Science Review 114, no. 2 (2020): 392–409. doi:10.1017/S0003055420000052.

- Grahn, Sandra, Anna Lührmann, and Lisa Gastaldi. “Resources for Democratic Politicians and Political Parties.” In Defending Democracy against Illiberal Challengers: A Resource Guide, edited by Anna Lührmann, Lisa Gastaldi, Dominik Hirndorf, and Staffan I. Lindberg, 45–53. Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute/University of Gothenburg, 2020.

- Grossman, Guy, Dorothy Kronick, Matthew Levendusky, and Marc Meredith. “The Majoritarian Threat to Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Experimental Political Science (2021): 1–10.

- Haggard, Stephan, and Robert R. Kaufman. Dictators and Democrats: Masses, Elites, and Regime Change. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Daniel J. Hopkins. “Public Attitudes Toward Immigration.” Annual Review of Political Science 17, no. 1 (2014): 225–249. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818.

- Heinisch, Reinhard. “Success in Opposition-Failure in Government: Explaining the Performance of Right-Wing Populist Parties in Public Office.” West European Politics 26, no. 3 (2003): 91–130. doi:10.1080/01402380312331280608.

- Heinze, Anna-Sophie. “Strategies of Mainstream Parties Towards Their Right-Wing Populist Challengers: Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland in Comparison.” West European Politics 41, no. 2 (2018): 287–309. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1389440.

- Hyde, Susan D. “Democracy’s Backsliding in the International Environment.” Science 369, no. 6508 (2020): 1192–1196. doi:10.1126/science.abb2434.

- Inglehart, Ronald, Christian Haerpfer, Alejandro Moreno, Christian Welzel, Kseniya Kizilova, Jaime Diez-Medrano, Lagos Marta, et al., eds. “World Values Survey: All Rounds – Country-Pooled Datafile.” ([dataset]; accessed March 3, 2021). http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp, 2020.

- Laebens, Melisa, and Anna Lührmann. “What Halts Democratic Erosion? The Changing Role of Accountability.” Democratization 5 (2021): 1–21.

- Leininger, Julia, Anna Lührmann, and Rachel Sigman. “The Relevance of Social Policies for Democracy.” Discussion Papers 7/2019, German Development Institute (DIE) (2019).

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Broadway Books, 2018.

- Linz, Juan. The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Crisis, Breakdown & Reequilibration. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978.

- Linz, Juan. “The Perils of Presidentialism.” Journal of Democracy 1, no. 1 (1990): 51–69. muse.jhu.edu/article/225694.

- Linz, Juan, and Alfred Stepan. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- Lührmann, Anna, Nils Düpont, Masaaki Higashijima, Yaman Berker Kavasoglu, Kyle L. Marquardt, Michael Bernhard, Holger Döring, et al. “Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V–Party) Dataset V1.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/data/v-party-dataset/?edit_off=true, 2020.

- Lührmann, Anna, Lisa Gastaldi, Dominik Hirndorf, and Staffan I. Lindberg, eds. Defending Democracy against Illiberal Challengers: A Resource Guide. Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute/University of Gothenburg, 2020.

- Lührmann, Anna, and Staffan I Lindberg. “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New about It?” Democratization 26, no. 7 (2019): 1095–1113. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029.

- Lührmann, Anna, Kyle L Marquardt, and Valeriya Mechkova. “Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability.” American Political Science Review 114, no. 3 (2020): 811–820. doi:10.1017/S0003055420000222.

- Lührmann, Anna, Juraj Medzihorsky, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Walking the Talk: How to Identify Anti-Pluralist Parties.” V-Dem Working Paper (2021).

- Mair, Peter. Ruling the Void: The Hollowing-Out of Western Democracy. London: Verso, 2013.

- Malka, Ariel, Yphtach Lelkes, Bert N. Bakker, and Eliyahu Spivack. “Who Is Open to Authoritarian Governance within Western Democracies?” Perspectives on Politics, First View (2020): 1–20. doi:10.1017/S1537592720002091

- McCoy, Jennifer, and Murat Somer. “Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no. 1 (2019): 234–271. doi:10.1177%2F0002716218818782.

- Medzihorsky, Juraj, Anna Lührmann, and Staffan Lindberg. “Autocratization by Elections: Arena or Trigger of Democratic Decline?” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) (2019).

- Meléndez, Carlos, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. “Negative Partisanship Towards the Populist Radical Right and Democratic Resilience in Western Europe.” Democratization 5 (2021): 1–21.

- Minkenberg, Michael. “The Radical Right in Public Office: Agenda-Setting and Policy Effects.” West European Politics 24, no. 4 (2001): 1–21. doi:10.1080/01402380108425462.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. “Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America.” Government and Opposition 48, no. 2 (2013): 147–174. doi:10.1017/gov.2012.11.

- Müller, Jan-Werner. “Militant Democracy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, edited by Michel Rosenfeld, and András Sajó. Oxford University Press, 2012. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199578610.013.0062.

- Müller, Jan-Werner. “Protecting Popular Self-Government from the People? New Normative Perspectives on Militant Democracy.” Annual Review of Political Science 19 (2016): 249–265. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-043014-124054.

- Müller, Jan-Werner. What Is Populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

- Norris, Pippa. Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. doi:10.1017/9781108595841.

- Pardos-Prado, Sergi, Bram Lancee, and Iñaki Sagarzazu. “Immigration and Electoral Change in Mainstream Political Space.” Political Behavior 36, no. 4 (2014): 847–875. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9248-y.

- Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, Farhad Miri, and Johannes von Römer. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data”. V-Dem Working Paper 21. 5th edition. (2020). doi:10.2139/ssrn.2704787.

- Petrarca, Constanza Sanhueza, Heiko Giebler, and Bernhard Weßels. “Support for Insider Parties: The Role of Political Trust in a Longitudinal-Comparative Perspective.” Party Politics (2020). doi:10.1177/1354068820976920.

- Popper, Karl. Open Society and Its Enemies. London: Routledge, 1945/2003.

- Przeworski, Adam. Sustainable Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Przeworski, Adam, Michael E. Alvarez, Jose Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Material Well-being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal. “Populism and the Question of How to Respond to it.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.21.

- Ruck, Damian J, Luke J Matthews, Thanos Kyritsis, Quentin D Atkinson, and R. Alexander Bentley. “The Cultural Foundations of Modern Democracies.” Nature Human Behaviour 4, no. 3 (2020): 265–269. doi:10.1038/s41562-019-0769-1.

- Schmitt, Hermann, Sara B. Hobolt, Wouter Van der Brug, and Sebastian Adrian Popa. “European Parliament Election Study 2019, Voter Study”. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. (2020). https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13473.

- Schroeder, Wolfgang, and Bernhard Weßels. Smarte Spalter. Bonn: Dietz Verlag J.H.W. Nachf, 2019.

- Somer, Murat, Jennifer McCoy, and Russell Evan Luke, IV. “Pernicious Polarization, Autocratization and Opposition Strategies.” Democratization 5 (2021): 1–20.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae, and Heike Klüver. “Responding to Far Right Challengers: Does Accommodation Pay Off?” Journal of European Public Policy 27, no. 2 (2020): 273–291. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1701530.

- Staton, Jeffrey, Christopher Reenock, and Jordan Holsinger. Can Courts be Bulwarks of Democracy? Judges and the Politics of Prudence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming.

- Stepan, Alfred, and Cindy Skach. “Constitutional Frameworks and Democratic Consolidation: Parliamentarianism versus Presidentialism.” World Politics 46, no. 1 (1993): 1–22. doi:10.2307/2950664.

- Svolik, Milan. “Authoritarian Reversals and Democratic Consolidation.” American Political Science Review 102, no. 2 (2008): 153–168. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080143.

- Svolik, Milan W. “When Polarization Trumps Civic Virtue: Partisan Conflict and the Subversion of Democracy by Incumbents.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 15, no. 1 (2020): 3–31.

- Urbanska, Karolin, and Serge Guimond. “Swaying to the Extreme: Group Relative Deprivation Predicts Voting for an Extreme Right Party in the French Presidential Election.” International Review of Social Psychology 31 (2018): 1–12. doi:10.5334/irsp.201.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., and Stijn Van Kessel. “Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support.” European Journal of Political Research 57, no. 1 (2018): 68–92. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12216.

- van Spanje, Joost. “Contagious Parties: Anti-immigration Parties and their Impact on other Parties’ Immigration Stances in Contemporary Western Europe.” In The Populist Radical Right: A Reader, edited by Cas Mudde, 474–492. Oxon: Routledge, 2017.

- Waldner, David, and Ellen Lust. “Unwelcome Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding.” Annual Review of Political Science 21 (2018): 93–113. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628.

- Welzel, Christian. “Democratic Horizons: What Value Change Reveals about the Future of Democracy.” Democratization (2021): 1–25.

- Wuttke, Alexander, Konstantin Gavras, and Harald Schoen. “Have Europeans Grown Tired of Democracy? New Evidence from Eighteen Consolidated Democracies, 1981–2018.” British Journal of Political Science (2020): 1–13. doi:10.1017/S0007123420000149.

- Ziblatt, Daniel. Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017. doi:10.1017/9781139030335.

- Zick, Andreas, Beate Küpper, and Wilhelm Berghan. “Verlorene Mitte – Feindselige Zustände. Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2018/19.” Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Bonn: Dietz, 2019.