ABSTRACT

This paper examines the importance of, and variations in, political alignment within African regimes. Political alignment is how leaders establish sufficient political support across elites: we posit that formal appointments are the primary way that leaders manipulate political coalitions in order to secure their collective authority and tenure. Appointments, individually and collectively, can take on multiple characteristics: they can create inclusive or exclusive coalitions, transactional or loyal support, volatile or stable elite networks. Appointment powers have greater salience since governments institutionalized and formalized in governance systems across democratic and autocratic states. Manipulating who holds and secures power at the subnational and national levels, rather than repressive control or state capacity, underpins the stability, security, and survival of modern African regimes.

Introduction

Alignment is a system of political alliances that dictates how leaders extract sufficient political support at the national and subnational levels to sustain their authority and further the reach of the regime. It is built on appointments into formal positions by leaders and a regime’s political senior elites. The placement of elites into appointments creates variations in representation, accommodations and power balances. In turn, appointments and formal authorities can be manipulated to create inclusivity, co-option, imbalance, increased coordination and competition between elites. Appointments are the basis for coalition-building between the leader and a regime’s political elites, and involve volatile transactional exchanges of loyalty and authority at multiple governing scales throughout the state.

By introducing alignment, we engage with several research avenues that consider the role of political elites as agents of regime security;Footnote1,Footnote2 the volatility of uneven governance and subnational variations in state presence;Footnote3 transactional political exchanges;Footnote4 and the role of formal institutional positions.Footnote5 In our investigation, regimes refer to the recognized government of a state; political elites are those who hold formal government office, are candidates for formal government office, or a recognized representative for a political party or movement.

This paper builds on research directions in Democratization which focus on avenues for further investigations into the practices of continuity;Footnote6 resilience of regimes to regressions;Footnote7 the use of institutional tools to develop new manipulations for regime continuity;Footnote8 the endurance of personalization, albeit negotiated and curtailed modern versions;Footnote9 intra-party political dynamics and frequently violent contestation;Footnote10 and new forms of patronage that emerge as regimes adopted democratic practices to secure power, rather than share it.Footnote11 We suggest a further interrogation of how regimes with both consistent rates of political violence and often volatile elite management are resilient by asking: how do regimes continue to evolve through strategies to hold power?

We reflect on how highly formalized, institutionalized and inclusive systemsFootnote12 sustain hybrid, competitive and complete autocracies through elite management. Whereas previous discussions of regime survival and capacity have privileged engagements between senior, national elites,Footnote13 we posit that modern African regimes are built upon a network of aligned subnational authorities. Regimes create formal appointments, decentralized budgets, new administrative positions, and devolved authority to broaden and deepen the formal integration and inclusion of elites.Footnote14 Footnote15 The resulting network requires constant management to keep it loyal, and responsive to leaders and senior elites. The goal is to secure alignment across elites, and this practice has important implications for stability, security and development.

Political alignment transmits state positions, rents, patronage, security to elites, and these relationships are short-term, volatile, and result in unlikely alliances, dangerous bargains, often bloated government agencies and ineffective regime politics and politics. For regimes, the management of elites is the business of government: their support from the bottom keeps the hierarchy stable; the largesse and integration flowing downwards through formal government roles keeps the centre surviving. Institutionalization requires this buy-in, and constant attention to elite integration, appointments, and balance.

Where does alignment deviate from established discussions of patronage, state control and uneven governance? We posit that alignment represents a significant break in previous interpretations of African regime authority and its machinations in two ways. First, its focus is not on repression as the main tool available to the regime to keep its subnational elites in line. Recent research demonstrates how strategies of co-option, accommodation and control are key to generating loyalty and support and securing mutual survival and stability.Footnote16 Second, it places importance on the subnational elites across states, rather than those on the senior, national level. The “uneven governance” discussion positions subnational regions as ungoverned – growing from failures in state and regime formation and consolidation – or independent from national regimes. Both positions often disregard the role that subnational governance actors have in creating and perpetrating national stability and regime survival. These research areas limit – if not obscure – the role of the central state and the agency of subnational elites who operate within the state and regime system.Footnote17 At its limits, the hybrid and contested state narratives render invisible the role played by governors, mayors and regional or municipal governments, local bureaucrats, and other agents of the state across the territory.Footnote18 Even a cursory knowledge of states – however weak or affected by crisis – can identify many formal representatives of the centre, including border guards, revenue collectors, agricultural extension workers, police and paramilitaries, among others. We suggest that alignment between the subnational and national elites, rather than repressive control or state capacity, underpins the stability, security, and survival of modern African regimes.

In this paper we delve into how political elites enter regimes; we consider how and why manipulations are widespread across democratic and autocratic African states; and we address how the alignment system is established to promote continuity despite often persistent crises. The four contributions demonstrate that the very significant increase in elites ushered into African political systems in the past decades has deepened the need to “manage” elite interests at different levels of the state hierarchy. While threats to leaders’ survival mainly come from inside regimes, tactics to nurture alignment with subnational elites are necessary to balance power at the national level.

Political alignment, formality and appointments

Over the past three decades, many African states have become more inclusive and institutionalized.Footnote19 They have adopted democratic processes; formalized election calendars; introduced term limits; increased the size of parliaments, cabinets, and bureaucracies; expanded representation to include ethno-political and regional minorities at senior government levels; and engaged in decentralization and devolution procedures.Footnote20 In an effective, well-institutionalized state with ample capacity and democratic legitimacy, the government operates at local, municipal, regional, and national levels under a hierarchical structure, with representation and oversight at each level seeking to ensure regime legitimacy. Multiple actors exist simultaneously and act in concert to deliver the regime’s governance agendas. Disagreements that arise, however serious, can potentially be managed via formal institutions, such as recourse to constitutional courts and electoral mandates, partisan structures, and involvement of civil society organizations.

A central paradox in modern African politics is that as states have become more inclusive and institutionalized, many incumbents continue to face persistent challenges to their regime’s survival and stability.Footnote21 Regimes and leaders most often encounter threats from the inside, despite how democratic gains in the past three decades fortified elites into formal positions of power. These elites placate, accommodate and manipulate authority, and those in government are often in contest with each other for dominance. National leaders thus enhance stability and ensure their survival in power through strategies of political control, making choices as to which elites to integrate into the regime and to what extent.Footnote22 Within these systems, elites cannot gain and keep power without the acquiescence of a variety of other elites, including ministers, governors, regional party leaders and cadres, elements of the security sector, and other members of the variable “selectorate.”Footnote23

The effects of how regimes negotiate political control between elites – and require a formal role to engage in politics – is that, in aggregate, many African states institutionalize without democratizing, stalling their democratic progress, or become increasingly autocratic.Footnote24 In many African countries, “formal democratic institutions exist and are widely viewed as the primary means of gaining power, but in which incumbents’ abuse of the state places them at a significant advantage vis-à-vis their opponents.”Footnote25 Spatial variations in the institutional design and power sharing arrangements within and across states are the function of political struggles and bargaining that goes on within African societies between rulers, urban and rural allies, and provincial rivals.Footnote26 It is within such contexts that the manipulation of the institutional hierarchy and its elite agents becomes vital to understand. We posit that the manipulation of appointments from local to national levels, and the introduction into, and churn of, elites within the formal system, is designed to maximize the alignment of power holders for the promotion, stability and survival of the regime.

Subnational authority and elites

Debates about transactional relationships, loyalties through proximate identities, leader removal, “informal” power structures, regime and elite characteristics pervade recent research on African democratization, autocracies, and institutional change.Footnote27 Development of a regime's territorial politicsFootnote28 have occurred outside of discussions focused on regime characteristics: the role and agency of subnational elites is often left at the margins of such discussions, with minimal attention to how central governments are dependent on coalitions of such groups.Footnote29 Footnote30 Further, the shifts in territorial authority as a result of national regime formalization and institutionalization have, thus far, failed to be drawn conclusively, nor have persistent variations in regime-subnational relationships been fully explained.

At one extreme, select research on African governance often presents countries as a volatile and often violent patchwork of different authorities within a national territory, rather than a unified, albeit contested, political order.Footnote31 As a result, limited state reach is translated into an absence of formal and structural representation mechanisms between the centre and the periphery, which render many governments incapable of providing basic services to their populations, including security.Footnote32 Weak state capacity is correlated with the emergence of civil wars and insurgent conflictFootnote33, and also is defined by it.Footnote34 Anti-system actors are expected to emerge and thrive in these “ungoverned spaces,” and disappear if and when national states assert their authority.Footnote35 But multiple forms of subnational authority have long existed in African states, where they frequently enabled the “indirect rule” of colonial states through local elites and intermediaries.Footnote36 Recent processes of devolution and federalism, along with the emergence of professional politicians at the regional level,Footnote37 have raised important questions about the nature and distribution of authority across states.Footnote38 In the hybrid rendering of African states, institutional pluralism is evident in a range of subnational governance actorsFootnote39 and components of a heterodox yet durable form of political order.Footnote40 Several “types” of agent exist within an alternative version of a “negotiated state”Footnote41: these processes of local governance integrate “a wider family of concepts … emphasising the contingent, constructed and contested nature of governance, public authority and security … . related formulations include the notion of “governance without government.”Footnote42 In such readings, the state is characterized by “the rule of the ‘intermediaries,’ a series of networks and polities that substitute and compensate for the lack of authority of the central, legally constituted state and its ability to deliver essential public goods and services.”Footnote43

These perspectives highlight that authority and governance are exercised and contested by a vast array of different subnational actors. The national regime is not a neutral or plural arena of interests, but possibly the strongest among a diverse set of political actors within national territories. But in such renderings, there is still little “subnational governance”: there are few formal governance arrangements that distribute degrees of authority to municipalities, districts, regions, and governorates.Footnote44 Yet, every state has a formal, institutionalized administrative system.Footnote45 Constellations of subnational authority within and across states means that there is no “one size fits all” definition of sub-national governance, and multiple combinations of authority can emerge, along with a wide range of political geographies and economies. Rather than such systems existing informally, or creating fiefdoms, we argue that it is imperative to the regime to maximize the alignment between the subnational authority and the centre.

Indeed, central regime survival is dependent on subnational elites and their ability to maximize their aligned claims to authority and legitimacy. At the subnational level, regimes exercise power via subnational representatives, and these subnational entities have significant levels of agency. Subnational elites often operate as gatekeepers, using their networks and positions to reinforce their local authority, suppress competition, and claim resources for themselves and surrounding elites.Footnote46 Representing their community and interests; acquiring and distributing patronage, and securing regime support in a region, make these elites far more than “agents” in a principal-agent scenario: they operate for own self-interest; they may engage in large scale corruption, and sometimes violently compete with other elites as and when they see fit. By contributing to determining the overall stability and functioning of the state, subnational elites are vital cogs in the politics of contemporary African states.

Subnational elites can leverage their authority within these institutional structures, turning their relationship with the centre and other subnational elites into one of mutual dependence and authority exchange. In turn, regimes are shown to be largely inclusive of representatives from subnational constituencies, granting them with access to government positions and rents.Footnote47 This is less likely a result of an “inclusive power-sharing” motive, and more likely to be due to the need to a regime to corral as many subnationally aligned powers as possible, regardless of ethnic, regional, or political identities. Regimes also increased power to devolved subnational authorities, including allowing “gatekeeping”Footnote48 and “boundary control”Footnote49 practices for these regime-aligned elites. For a local elite’s sustained authority, the exchange of these powers creates an increased dependence and loyalty to keep national elites in power.

An effective subnational support structure accommodates and co-opts a multitude of elites from regional or provincial communities, and requires extensive regime management.Footnote50 Leaders are only as strong as their coalition of national and subnational elites, whose aggregate composition reflects where support is strongest.Footnote51 Local authorities are at the frontline of resource control, territorial integrity, and opposition suppression. Likewise, subnational appointments are vital tools for managing competition among elites and building coalitions of loyalty. The primary value of subnational appointments, therefore, is not about creating stable or effective governments, but nurturing mutually beneficial relationships where loyalty towards the centre is exchanged with co-option.Footnote52 Consequently, managing local level elite support is indeed pivotal for regimes’ survival,Footnote53 and maintaining power requires that they build and maintain relationships with subnational authorities: these gatekeepers are intermediaries with local power and control, brokering alliances between leaders, constituencies, and voters.Footnote54

The practice of political alignment

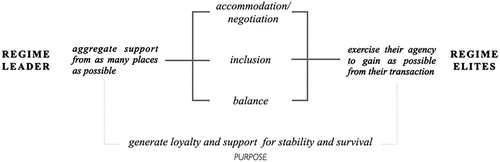

Political alignment in Africa is characterized by two components: the formal transaction of authority between senior leadership and intermediate elites (via appointments); and the support and loyalty that results from these appointments. Institutional arrangements and manipulations of appointments increase the number and power of subnational elites, while simultaneously extending the power of the regime and leader to those positions and elites. The result is a political architecture that delegates power through institutional appointments to those aligned to the regime. The agents and processes of alignment are represented by .Footnote55

Political alignment is practised at different levels and spheres of a regime: from the national government down to subnational authorities, security agencies, bureaucracies, and other institutional apparatuses. Through appointments and their characteristics, mutual political benefits are designed from practices sustain regime authority and reach.Footnote56 Extensive scholarship on clientelism, bureaucratic politics and “competitive authoritarianism” consider appointments as part of the “menu of manipulation,”Footnote57 and how regime manage elites and social groups in an attempt to ensure stability and regime survival.Footnote58 The regime uses appointments and representation to reward and punish, and exchanges of patronage and authority are closely associated with the fluid needs of the regime and its immediate responses to political developments.Footnote59

The proliferation of formal positions in African states means that institutional appointments are a primary avenue for distributing and legitimizing authority.Footnote60 Even in cases where the central government is poorly consolidated, the most significant claims of power are formal, via a structure that links elites to resources, authority, and legitimacy.Footnote61 The aggregated positions and relationships that result are fluid and volatile but constitute a functioning political architecture.Footnote62 Therefore, where institutionalization formalizes the authority and roles of subnational political elites, political exchanges between national and subnational elites can be measured through empirical outcomes, including ministerial or bureaucratic appointments; institutional changes; and other shifts in the composition of the regime.Footnote63

Examples of these practices abound across African regimes. Cabinets are an exemplar of such transactions. Appointments and reshuffles of cabinets to include regional or ethnic representatives is well-documented in the existing scholarship, and points to how ministerial appointments contribute to nurturing alignment with subnational elites and ultimately security regime stability.Footnote64 In Ethiopia, for example, an extensive analysis of the cabinet system indicated how elite changes at the ministerial level, and new ethnic balancing, cemented regime change in 2018. The elite coalitions built at that time (and rebuilt multiple times since) were expected to fortify the new leader and his agenda.Footnote65 Yet, alignment is also practiced at the parliamentary level through the co-option of opposition or the reshaping of parliamentary coalitions. In Togo, Faure Gnassingbé stabilized his rule by forging a distinctive parliamentary coalition that relies on the support of the Kabye ethnic group and former regime cadres.Footnote66 Likewise, the co-option of opposition politicians into the cabinet is also practiced widely across African countries.Footnote67

Especially ahead of contested elections, regimes are likely to engage in alignment practices to influence electoral outcomes.Footnote68 The holding of multiparty elections in democratic and competitive authoritarian regimes, as well as the empowering of subnational gatekeepers whose support is key to enforce electoral wins, can alter the calculus of subnational-national relationships by increasing the agency of subnational elites. Regimes are especially likely to seek the support of local gatekeepers in electoral swing areas, where access to local constituencies is key to win tight electoral contests and local authorities can use their leverage to be co-opted in exchange for delivering votes.Footnote69 In turn, research on African elections has also shown that electoral coalitions assembled by incumbents around dominant subnational figures are more likely to win elections and defeat opposition challenges.Footnote70 Alignment through institutional engineering is frequently practised in Nigeria, where zoning and consociationalism aggregate several groups in grand coalitions, while also providing subnational elites with the tools to ensure an electoral outcome desired by incumbents.Footnote71 In turn, Nigerian local governments have used this system to their own advantage, turning the design of the federalist system and their protected roles to extract political outcomes and manipulate corruption opportunities and appointments.Footnote72

Yet, as reliably as these measures can extend a leader’s tenure and authority, a failure to align destabilizes regimes. Consider recent events in Sudan, when then-president Omar Bashir fired all regional governors during a period of intense political turmoil in 2018.Footnote73 Why did he focus on governors at this time? He did so to prevent them from aligning with inner circle defectors: if the allegiances of regional leaders shifted to the coup plotters, Bashir’s survival was in grave doubt.Footnote74 For Bashir’s coalition, the governors’ individual support was central, and their aggregated support was vital. By placing those he trusted in governor positions, Bashir exchanged control over security, funds, party offices, and state agents for regional alignment and loyalty. When regional alignment was in doubt, Bashir’s attempt to fire governors and remove their authority before they could defect was based on the calculation that, without access to the formal state position, potentially disloyal office holders would be without power, forces and influence. The regional governors did prove to be ineffective without their positions, but too many other appointees had defected from across the political network.Footnote75 Bashir eventually failed to secure political support, before being removed in April 2019 by his former regime allies.

A similar example played out in Ethiopia at the outset of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali’s time in office in 2018. While initially granting a wide degree of independence to regional Presidents in exchange for support with the regime transition of 2018, the violent actions of Somali regional President Iley against a Somali minority group caused a rupture in national-regional alignment. The result was a violent removal of the regional president, and an established threshold for independent action by regional Presidents. In both cases, the alignment between national and subnational elites was volatile, transactional, and important to the security of the regime.Footnote76

This overview shows that political alignment is not homogeneous and monolithic but responsive to competition, change and variable levels of authority. The political longevity of a regime reflects balances of power and loyalty between the centre and subnational authorities; these regimes survive when the sum and costs of alignment is in their favour. Leaders and regimes that lack alignment are highly vulnerable to dissent, while leaders that have high alignment must control the costs of accommodating elites. The relationships fostered between central and subnational authorities are highly variable, heterogeneous and volatile as they respond to local circumstances and challenges. Who is aligned with the regime, and where they are based, are important questions, indicating that previous conceptions of entrenched political relationships are less relevant in contemporary regimes than previously assumed across Africa. Leaders must balance, manipulate, and manage elites and interests. This creates short term practices and actions, even across long-lasting regimes.

Research going forward

This paper, demonstrates the centrality of the notion of political alignment to understand the survival of African regimes. Political alignment encourages the “buy-in” of elites towards the regime’s continuing authority. The centre seeks to co-opt many subnational elites; appease others; and control dis-aligned elites, groups, and locations. In places of limited alignment between centre and periphery – that is, where coordination is poor and rival centres of power exist – state engagement is more likely to include coercive means.Footnote77 Strong subnational authorities can be the most powerful allies in advancing a regime’s agenda in the provinces, yet they can also turn into competitors and try to undermine regime stability.Footnote78 Destabilizing the regime’s subnational coalition, they may constitute the most significant threats to its stability.

Political crisis, elite churn, and coalition composition reflect choices about the costs of alignment with local power holders and the central regime.Footnote79 The thematic section examines these issues and suggest that interpreting the domestic politics of African states in the light of the construction and costs of necessary subnational alignment is a key explanation for the often-volatile process of regime survival. While individual interest balancing and strategic alliances are at play at the national elite level, subnational coalitions and alliances of aggregated elites are also crucial. For ruling regimes, the goal is to generate and aggregate support from as many places as possible; elites exercise agency to gain as much as possible from these transactions. Bargaining between the national and the subnational level, rather than the unilateral choices of the centre, drives the politics of national (dis)integration and determines how institutions distribute power among state elites.

Current and future directions of research in this area should expand recent work on domestic regime politics in African states, and lessons learned might also be applied to some states outside Africa. We suggest that the volatile nature of domestic politics is best explained by such coalition building and negotiation rather than grand state capacity or state building theories that do not consider the ongoing, volatile, short-termism of most regimes. We advance this discussion by positing that the state is not neutral in its approach to supporting, allying, or rejecting local leadership, which negotiates their positions with other relevant agents including governors, senators, representatives of national, regional, and local governments. In interrogating positions, scales, and locations of power, subnational elites, territorial governance, subnational elites and representatives are part of the governing calculus of autocratic and democratic states in similar ways.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2024.2369139)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Clionadh Raleigh

Clionadh Raleigh is a professor of political geography and conflict at the University of Sussex, and the president and founder of the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data organization (ACLED). Her European Research Council Horizon 2020 project VERSUS (Violence and Elites in States under Stress) no. 726504 focused on subnational elites and authority patterns across African states.

Andrea Carboni

Andrea Carboni completed his PhD at the University of Sussex in 2021, and is a researcher on the VERSUS project. He is the head of analysis at ACLED.

Notes

1 Daloz, “Political Elites in Sub-Saharan Africa”.

2 Ibid.

3 Boone, Political Topographies.

4 Arriola, “Patronage and political stability”.

5 Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance”.

6 Sinkkonen, “Dynamic dictators”.

7 Merkel and Luhrmann, “Resilience of democracies”.

8 Heyl and Llanos, “Contested, Violated but Persistent”; Tolstrup, “When can External Actors Influence Democratization?”; Wiebreacht, “Between Elites and Opposition”.

9 Grundholm, “Taking it Personal”.

10 Van de Walle, “The Party Paradox”.

11 Berenschot and Aspinall, “How Clientelism Varies”.

12 Meng, Constraining Dictatorship; Posner and Young, “The institutionalization of Political Power in Africa”.

13 Geddes et al., How dictatorships work.

14 Meng, Constraining Dictatorship.

15 Geddes et al. How Dictatorships Work.

16 Carter and Hassan, “Regional Governance in Divided Societies”; Hassan, Mattingly, and Nugent, “Political Control”.

17 For variations on this theme, and a deeper political economy approach, see Boone, Political Topographies.

18 Mamdani, Citizen and Subject.

19 Bleck and Van De Walle, Electoral Politics in Africa; Meng, Constraining Dictatorship.

20 Arriola, “Patronage and political stability”; Haass and Ottmann, “Rebels, Revenue and Redistribution”; Osei and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Personal Power in Africa”.

21 Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance”.

22 Arriola et al., “Democratic Subversion”; Arriola and Johnson, “Ethnic Politics and Women's Empowerment”; Hassan, Mattingly, and Nugent, “Political Control”.

23 Bueno de Mesquita et al., The Logic of Political Survival.

24 Arriola, Rakner, and Van De Walle, Democratic Backsliding in Africa; Bleck and Van De Walle, Electoral Politics in Africa; Raleigh et al., 2021.

25 Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism, 5.

26 Boone, Political Topographies.

27 Brownlee, Authoritarianism in an Age of Democratization; Van de Walle, “Meet the New Boss”; Arriola, “Patronage and political stability”; De Bruin, “Preventing Coups d’état”.

28 Tarrow, Katzenstein, and Graziano, Territorial Politics in Industrial Nations; Boone, Political Topographies; Giraudy, Democrats and Autocrats.

29 Recent seminal work on centre-periphery relations was conducted by Gorlizki and Khlevniuk in relation to the Soviet Union. Gorlizki and Khlevniuk, Substate Dictatorship.

30 Choi and Raleigh, “The Geography of Regime Support”.

31 Wolff, Ross, and Wee, Subnational Governance and Conflict.

32 Krämer, “Why Africa’s ‘Weak States’ Matter”; Polese and Santini, “Limited Statehood and its Security Implications”.

33 Raleigh and Dowd, “Governance and Conflict”; Mukhopadhyay, Warlords, Strongman Governors; Boone, Political Topographies; Carter and Hassan, “Regional Governance in Divided Societies”.

34 Fearon and Laitin, “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War”; Stanislawski et al., “Para-States, Quasi-States”; Collier and Rohner, “Democracy, Development, and Conflict”.

35 Jackson and Rosberg, Personal Rule in Black Africa; Herbst, States and Power in Africa.

36 Mamdani, Citizen and Subject.

37 Tronconi, “Sub-National Political Elites”.

38 Bratton, “Citizen Perceptions”; Cederman et al., “Territorial Autonomy”; Erk, “Iron Houses”; Wilfart, “The Politics of Local Government”; Wolff, Ross, and Wee, Subnational Governance and Conflict; Iddawela, Lee and Rodríguez-Pose. “Quality of Subnational Government”.

39 Bierschenk and De Sardan, “Local Powers”.

40 Naseemullah, Adnan. “Shades of Sovereignty”.

41 Titeca and De Herdt, “Real governance beyond the ‘failed state’”.

42 Lund, “Twilight Institutions", 694.

43 Scheye, “State Provided Service”, 5.

44 Wolff, Ross, and Wee, Subnational Governance and Conflict, 19.

45 Treisman, The Architecture of Government.

46 Tolstrup, “When can External Actors Influence Democratization?”.

47 Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance”.

48 Choi and Raleigh, “The Geography of Regime Support”.

49 Gibson, Boundary Control.

50 Hassan “Regime Threats and State Solutions”

51 Arriola, Multi-Ethnic Coalitions in Africa; Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance”.

52 Similar mechanisms were also applied in the analysis of modern Afghani politics. Mukhopadhyay, Warlords, Strongman Governors.

53 Koter, “King Makers”.

54 Corra and Willer, “The Gatekeeper”; Sidel, “Economic Foundations of Subnational Authoritarianism.”

55 Graphic designed by Dr Tiziana Corda.

56 Hassan, Mattingly, and Nugent, “Political Control”; Carter and Hassan, “Regional Governance in Divided Societies.”

57 Schedler, Electoral Authoritarianism.

58 Arriola, “Patronage and Political Stability”; Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance.”

59 Blaydes, Elections and Distributive Politics.

60 Osei, “Formal Party Organisation”; Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance”; Woldense, “The Ruler’s Game”; Woldense, “What Happens When Coups Fail.”

61 Schouten, Roadblock Politics.

62 Carboni and Raleigh, “Regime Cycles and Political Change.”

63 Bertelli et al, “An Agenda for the Study of Public Administration”; Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance”; Woldense, “The Ruler’s Game.”

64 Wehner and Mills, “Cabinet Size and Governance.”

65 Meester, Lanfranchi and Gebregzibar, “Clash of Nationalisms and the Remaking of the Ethiopian State.”

66 Osei, “Like Father, Like Son?”

67 Arriola, Devaro, and Meng. “Democratic Subversion.”

68 Hassan, “The Strategic Shuffle”; Hicken and Nathan, “Clientelism's Red Herrings”; Pierskalla and Sacks, “Personnel Politics.”

69 Cheeseman, Lynch, and Willis, The Moral Economy of Elections in Africa; Choi and Raleigh, “The Geography of Regime Support”.

70 Resnick, “Do Electoral Coalitions Facilitate Democratic Consolidation in Africa?”

71 Kendhammer, “Talking Ethnic but Hearing.”

72 Page and Wando, “Halting the Kleptocratic Capture.”

73 Carboni and Raleigh, “Regime Cycles and Political Change.”

74 Indeed, 16 of the 18 governors had been appointed from military ranks to placate that faction of the Bashir government. International Crisis Group, “Bashir Moves Sudan”.

75 el-Gizouli, “The Fall of al-Bashir.”

76 Hagmann, “Fast Politics, Slow Justice.”

77 Gel’man and Ryzhenkov, “Local Regimes, Sub-national Governance”; Hassan, “The Strategic Shuffle.”

78 Mukhopadhyay, Warlords, Strongman Governors.

79 De Waal, The Real Politics of the Horn.

Bibliography

- Arriola, Leonardo R. “Patronage and Political Stability in Africa.” Comparative Political Studies 42, no. 10 (2009): 1339–1362. doi:10.1177/0010414009332126

- Arriola, Leonardo R. Multi-Ethnic Coalitions in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Arriola, Leonardo R., Jed Devaro, and Anne Meng. “Democratic Subversion: Elite Cooptation and Opposition Fragmentation.” American Political Science Review 115, no. 4 (2021): 1358–1372.

- Arriola, Leonardo R., and Martha C. Johnson. “Ethnic Politics and Women's Empowerment in Africa: Ministerial Appointments to Executive Cabinets.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (2014): 495–510.

- Arriola, Leonardo R., Lise Rakner, and Nicholas Van de Walle. Democratic Backsliding in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Berenschot, Ward, and Edward Aspinall. “How Clientelism Varies: Comparing Patronage Democracies.” Democratization 27, no. 1 (2020): 1–19. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1645129

- Bertelli, Anthony M., Mai Hassan, Dan Honig, Daniel Rogger, and Martin J. Williams. “An Agenda for the Study of Public Administration in Developing Countries.” Governance 33 (2020): 735–748. doi:10.1111/gove.12520

- Bierschenk, Thomas, and Jean-Pierre Olivier De Sardan. “Local Powers and a Distant State in Rural Central African Republic.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 35, no. 3 (1997): 441–468. doi:10.1017/S0022278X97002504

- Blaydes, Lisa. Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Bleck, Jaimie, and Nicholas Van de Walle. Electoral Politics in Africa Since 1990: Continuity in Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Boone, Catherine. Political Topographies of the African State: Territorial Authority and Institutional Choice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Bratton, Michael. “Citizen Perceptions of Local Government Responsiveness in Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Development 40, no. 3 (2012): 516–527. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.003

- Brownlee, Jason. Authoritarianism in an Age of Democratization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

- Carboni, Andrea, and Clionadh Raleigh. “Regime Cycles and Political Change in African Autocracies.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 59, no. 4 (2021): 415–437. doi:10.1017/S0022278X21000240

- Carter, Brett L., and Mai Hassan. “Regional Governance in Divided Societies: Evidence from the Republic of Congo and Kenya.” The Journal of Politics 83, no. 1 (2021): 40–57. doi:10.1086/708915

- Cederman, Lars-Erik, Simon Hug, Andreas Schädel, and Julian Wucherpfennig. “Territorial Autonomy in the Shadow of Conflict: Too Little, Too Late?” American Political Science Review 109, no. 2 (2015): 354–370. doi:10.1017/S0003055415000118

- Cheeseman, Nic, Gabrielle Lynch, and Justin Willis. The Moral Economy of Elections in Africa: Democracy, Voting and Virtue. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Choi, Hyun Jin, and Clionadh Raleigh. “The Geography of Regime Support and Political Violence.” Democratization 28, no. 6 (2021): 1095–1114. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1901688

- Collier, Paul, and Dominic Rohner. “Democracy, Development, and Conflict.” Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (2008): 531–540. doi:10.1162/JEEA.2008.6.2-3.531

- Corra, Mamadi, and David Willer. “The Gatekeeper.” Sociological Theory 20, no. 2 (2002): 180–207. doi:10.1111/1467-9558.00158

- Daloz, Jean-Pascal. “Political Elites in Sub-Saharan Africa.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Political Elites, edited by Heinrich Best, and John Higley, 241–253. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- De Bruin, Erica. “Preventing Coups D’état.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62, no. 7 (2018): 1433–1458. doi:10.1177/0022002717692652

- De Waal, Alex. The Real Politics of the Horn of Africa: Money, War and the Business of Power. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015.

- Erk, Jan. “Iron Houses in the Tropical Heat: Decentralization Reforms in Africa and Their Consequences.” Regional & Federal Studies 25, no. 5 (2015): 409–420. doi:10.1080/13597566.2015.1114921

- Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil war.” American Political Science Review 97, no. 1 (2003): 75–90. doi:10.1017/S0003055403000534

- Geddes, Barbara. “What do we Know About Democratization After Twenty Years?” Annual Review of Political Science 2, no. 1 (1999): 115–144. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.115

- Geddes, Barbara, Joseph George Wright, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz. How Dictatorships Work: Power, Personalization, and Collapse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Gel’man, Vladimir, and Sergei Ryzhenkov. “Local Regimes, Sub-National Governance and the ‘Power Vertical’ in Contemporary Russia.” Europe-Asia Studies 63, no. 3 (2011): 449–465. doi:10.1080/09668136.2011.557538

- Gibson, Edward L. Boundary Control: Subnational Authoritarianism in Federal Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Giraudy, Agustina. Democrats and Autocrats: Pathways of Subnational Undemocratic Regime Continuity Within Democratic Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- el-Gizouli, Magdi. “The Fall of al-Bashir: Mapping Contestation Forces in Sudan.” Arab Reform Initiative, 12 April (2019). https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/the-fall-of-al-bashir-mapping-contestation-forces-in-sudan/.

- Gorlizki, Yoram, and Oleg Khlevniuk. Substate Dictatorship: Networks, Loyalty, and Institutional Change in the Soviet Union. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.

- Grundholm, Alexander T. “Taking it Personal? Investigating Regime Personalization as an Autocratic Survival Strategy.” Democratization 27, no. 5 (2020): 797–815. doi:10.1080/13510347.2020.1737677

- Haass, Felix, and Martin Ottmann. “Rebels, Revenue and Redistribution: The Political Geography of Post-Conflict Power-Sharing in Africa.” British Journal of Political Science 51, no. 3 (2021): 981–1001. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000474

- Hagmann, Tobias. “Fast Politics, Slow Justice: Ethiopia’s Somali Region two Years After Abdi Iley” Conflict Research Programme Briefing Paper (2020). https://copese.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Hagmann-Two-years-after-Iley-final.pdf.

- Hassan, Mai. “The Strategic Shuffle: Ethnic Geography, the Internal Security Apparatus, and Elections in Kenya.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (2017): 382–395. doi:10.1111/ajps.12279

- Hassan, Mai. Regime Threats and State Solutions: Bureaucratic Loyalty and Embeddedness in Kenya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Hassan, Mai, Daniele Mattingly, and Elizabeth R. Nugent. “Political Control.” Annual Review of Political Science 25, no. 1 (2022): 155–174. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-013321

- Herbst, Jeffrey. States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Heyl, Charlotte, and Mariana Llanos. “Contested, Violated but Persistent: Presidential Term Limits in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa.” Democratization 29, no. 1 (2022): 1–17. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1997991

- Hicken, Allen, and Noah L. Nathan. “Clientelism's red Herrings: Dead Ends and new Directions in the Study of Nonprogrammatic Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 23 (2020): 277–294. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-032657

- Iddawela, Yohan, Neil Lee, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose. “Quality of Subnational Government and Regional Development in Africa.” The Journal of Development Studies 57, no. 8 (2021): 1282–1302. doi:10.1080/00220388.2021.1873286

- International Crisis Group. “Bashir Moves Sudan to Dangerous New Ground.” International Crisis Group, 26 February (2019). https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/sudan/bashir-moves-sudan-dangerous-new-ground.

- Jackson, Robert H., and Carl G. Rosberg. Personal Rule in Black Africa: Prince, Autocrat, Prophet, Tyrant. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1982.

- Kendhammer, Brandon. “Talking Ethnic but Hearing Multi-Ethnic: The Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP) in Nigeria and Durable Multi-Ethnic Parties in the Midst of Violence.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 48, no. 1 (2010): 48–71. doi:10.1080/14662040903444509

- Koter, Dominika. “King Makers: Local Leaders and Ethnic Politics in Africa.” World Politics 65, no. 2 (2013): 187–232. doi:10.1017/S004388711300004X

- Krämer, Anna Maria. “Why Africa’s ‘Weak States’ Matter: A Postcolonial Critique of Euro-Western Discourse on African Statehood and Sovereignty”. In Reimagining the State, 79–96. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Problems of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Lund, Christian. “Twilight Institutions: Public Authority and Local Politics in Africa.” Development and Change 37 (2006): 685–705. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2006.00497.x

- Magaloni, Beatriz. Voting for Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival and Its Demise in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Magaloni, Beatriz, and Ruth Kricheli. “Political Order and One-Party Rule.” Annual Review of Political Science 13 (2010): 123–143. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220529

- Mamdani, Mahmood. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Meng, Anne. Constraining Dictatorship: Personalized Rule to Institutionalized Regimes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Meester, Jos, Guido Lanfranchi, and Tefera Negash Gebregziabher. “A Clash of Nationalisms and the Remaking of the Ethiopian State: The Political Economy of Ethiopia’s Transition.” The Clingendael Institute (2022). https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2022/the-remaking-of-the-ethiopian-state/.

- Merkel, Wolfgang, and Anna Lührmann. “Resilience of Democracies: Responses to Illiberal and Authoritarian Challenges.” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 869–884. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1928081

- Mukhopadhyay, Dipali. Warlords, Strongman Governors, and the State in Afghanistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Naseemullah, Adnan. “Shades of Sovereignty: Explaining Political Order and Disorder in Pakistan’s Northwest.” Studies in Comparative International Development 49 (2014): 501–522. doi:10.1007/s12116-014-9157-z

- Osei, Anja. Party-Voter Linkage in Africa. Ghana and Senegal in Comparative Perspective. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2012.

- Osei, Anja. “Formal Party Organisation and Informal Relations in African Parties: Evidence from Ghana.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 54, no. 1 (2016): 37–66. doi:10.1017/S0022278X15000981

- Osei, Anja. “Like Father, Like son? Power and Influence Across two Gnassingbé Presidencies in Togo.” Democratization 25, no. 8 (2018): 1460–1480. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1483916

- Osei, Anja, and Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd. “Personal Power in Africa: Legislative Networks and Executive Appointments in Ghana, Togo and Gabon.” Government and Opposition (2022): 1–25. doi:10.1017/gov.2022.42

- Page, Matthew, and Abdul H. Wando. “Halting the Kleptocratic Capture of Local Government in Nigeria.” Carnegie Endowment of International Peace, 18 July (2022). https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/07/18/halting-kleptocratic-capture-of-local-government-in-nigeria-pub-87513.

- Pierskalla, Jan H., and Audrey Sacks. “Personnel Politics: Elections, Clientelistic Competition and Teacher Hiring in Indonesia.” British Journal of Political Science 50, no. 4 (2020): 1283–1305. doi:10.1017/S0007123418000601

- Polese, Abel, and Ruth Hanau Santini. “Limited Statehood and its Security Implications on the Fragmentation Political Order in the Middle East and North Africa.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 29, no. 3 (2018): 379–390. doi:10.1080/09592318.2018.1456815

- Posner, Daniel N., and Daniel J. Young. “The Institutionalization of Political Power in Africa.” Journal of Democracy 18, no. 3 (2007): 126–140. doi:10.1353/jod.2007.0053

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Hyun Jin Choi, and Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd. “Inclusive Conflict? Competitive Clientelism and the Rise of Political Violence.” Review of International Studies 48, no. 1 (2022): 44–66. doi:10.1017/S0260210521000218

- Raleigh, Clionadh, and Caitriona Dowd. “Governance and Conflict in the Sahel’s ‘Ungoverned Space’.” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2, no. 2 (2013): 1–17. doi:10.5334/sta.bs

- Raleigh, Clionadh, and Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd. “Elite Coalitions and Power Balance Across African Regimes: Introducing the African Cabinet and Political Elite Data Project (ACPED).” Ethnopolitics 21, no. 1 (2022): 22–47. doi:10.1080/17449057.2020.1771840

- Raleigh, Clionadh, et al. “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651–660. doi:10.1177/0022343310378914

- Resnick, Danielle. “Do Electoral Coalitions Facilitate Democratic Consolidation in Africa?” Party Politics 19, no. 5 (2013): 735–757. doi:10.1177/1354068811410369

- Schedler, Andreas, ed. Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Boulder, CO: Rienner. 2006.

- Scheye, Eric. State Provided Service, Contracting Out, and Non-State Networks: Justice and Security as Public and Private Goods and Services. International Network on Conflict and Fragility. Paris: INCAF, 2009.

- Schouten, Peer. Roadblock Politics: The Origins of Violence in Central Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Sidel, John T. “Economic Foundations of Subnational Authoritarianism: Insights and Evidence from Qualitative and Quantitative Research.” Democratization 21, no. 1 (2014): 161–184. doi:10.1080/13510347.2012.725725

- Sinkkonen, Elina. “Dynamic Dictators: Improving the Research Agenda on Autocratization and Authoritarian Resilience.” Democratization 28, no. 6 (2021): 1172–1190. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1903881

- Slater, Dan, and Diana Kim. “Standoffish States: Nonliterate Leviathans in Southeast Asia.” TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 3, no. 1 (2015): 25–44. doi:10.1017/trn.2014.14

- Stanislawski, Bartosz H., Katarzyna Pełczyńska-Nałęcz, Krzysztof Strachota, Maciej Falkowski, David M. Crane, and Melvyn Levitsky. “Para-States, Quasi-States, and Black Spots: Perhaps Not States, but Not ‘Ungoverned Territories,’ Either.” International Studies Review 10, no. 2 (2008): 366–396.

- Tarrow, Sydney, Peter J. Katzenstein, and Luigi Graziano, eds. Territorial Politics in Industrial Nations. New York: Praeger, 1978.

- Titeca, Kristof, and Tom De Herdt. “Real Governance Beyond the 'failed State': Negotiating Education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” African Affairs 110, no. 439 (2011): 213–231. doi:10.1093/afraf/adr005

- Tolstrup, Jakob. “When Can External Actors Influence Democratization? Leverage, Linkages, and Gatekeeper Elites.” Democratization 20, no. 4 (2013): 716–742. doi:10.1080/13510347.2012.666066

- Treisman, Daniel. The Architecture of Government: Rethinking Political Decentralization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Tronconi, Filippo. “Sub-National Political Elites.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Political Elites, edited by Heinrich Best, and John Higley, 611–624. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Van de Walle, Nicolas. “Meet the new Boss, Same as the old Boss? The Evolution of Political Clientelism in Africa.” In Patrons, Clients, and Policies: Patterns of Democratic Accountability and Political Competition, edited by Herbert Kitschelt and Steven I. Wilkinson, 50–67. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2007.

- Van de Walle, Nicolas. “The Party Paradox: A Comment Nicolas van de Walle (Cornell) February 20, 2018.” Democratization 25, no. 6 (2018): 1052–1062. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1464253

- Wehner, Joachim, and Linnea Mills. “Cabinet Size and Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Governance 35 (2022): 123–141. doi:10.1111/gove.12575

- Wiebrecht, Felix. “Between Elites and Opposition: Legislatures’ Strength in Authoritarian Regimes.” Democratization 28, no. 6 (2021): 1075–1094. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1881487

- Wilfart, Martha. “The Politics of Local Government Performance: Elite Cohesion and Cross-Village Constraints in Decentralized Senegal.” World Development 103 (2018): 149–161. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.09.010

- Woldense, Josef. “The Ruler’s Game of Musical Chairs: Shuffling During the Reign of Ethiopia’s Last Emperor.” Social Networks 52 (2018): 154–166. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2017.07.002

- Woldense, Josef. “What Happens When Coups Fail? The Problem of Identifying and Weakening the Enemy Within.” Comparative Political Studies 55, no. 7 (2022): 1236–1265. doi:10.1177/00104140211047402

- Wolff, Stefan, Simona Ross, and Asbjorn Wee. Subnational Governance and Conflict: The Merits of Subnational Governance as a Catalyst for Peace. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020.