ABSTRACT

The proliferation of democratic rule in Africa has been accompanied by external involvement in fostering democracy. The African Union along with various regional organizations have included clauses in their treaties calling for member-state adherence to democratic governance. Moreover, African regional organizations have used punishments such as membership suspension, sanctions, and military force to motivate states experiencing democratic reversals to change course. However, despite these trends, there has been no investigation into how Africans perceive external involvement in fostering democracy. This study remedies this gap by evaluating public attitudes toward such external pressure using the sixth round of the Afrobarometer survey. Specifically, the study explores how individual assessment of electoral practice and a country's and its neighbours' history of unconstitutional changes of government influence approval of external democracy promotion. This article lays the foundation for further investigating the roots of legitimacy of actions taken by international organizations aimed at promoting good governance and democracy.

Introduction

On 2 December 2016, Yahya Jammeh shockingly lost the presidential elections in The Gambia to the unknown Adama Barrow. Although having initially accepted this result that marked the end of his 22-year rule, Jammeh later rescinded his concession and demanded fresh elections arguing that the electoral process had been compromised. Jammeh’s about-face was surprising particularly because The Gambia’s Independent Electoral Commission along with African Union (AU) observers had concluded that the elections were relatively free and fair. In response, the AU and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) condemned Jammeh’s actions, urged him to honour the outcome of the elections, and initiated mediation talks to facilitate Jammeh’s departure. Instead, Jammeh persisted in refusing to relinquish power and declared a state of emergency. AU and ECOWAS responded by increasing pressure on Jammeh and ceasing to recognize him as president of The Gambia. ECOWAS went further by indirectly threatening to use force to intervene militarily to ensure Barrow’s electoral victory prevailed if Jammeh did not relinquish power. Still refusing to step down, ECOWAS endorsed the inauguration of Barrow at The Gambian embassy in Senegal on 19 January 2017, amassed troops on the border of The Gambia, and gave Jammeh an ultimatum to relinquish power or face ECOWAS’s military intervention in support of Barrow’s presidency. With pressure from ECOWAS mounting, Jammeh finally resigned and fled the country on 21 January 2017. In this instance, ECOWAS intervention was instrumental in promoting electoral democracy in The Gambia.

The involvement of regional organizations in the politics of African states has become common since the end of the Cold War. The AU for example has developed formal guidelines on how the organization should respond in cases of unconstitutional changes of government such as coups d’état. ECOWAS along with other regional economic communities including the East African Community (EAC), West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), and Southern African Development Community (SADC) have formalized their procedures aimed at promoting constitutional rule through observing elections, mediating political crises in member-states, suspending the participation of member-states deviating from constitutional rule, and imposing sanctions on perpetrators of unconstitutional changes of government. Such involvement has been heralded as complementing domestic efforts of consolidating democracy in Africa. However, no study has considered how the potential beneficiaries of these external democracy promotion activities perceive such efforts. Understanding and explaining public attitudes toward these democracy promotion activities can help to shed light on the legitimacy and necessity of these regional efforts. Importantly, an investigation of public opinion towards external democracy promotion among citizens of states targeted with such efforts can help us understand the extent to which and under what conditions international policies resonate with and have the support of these citizens.

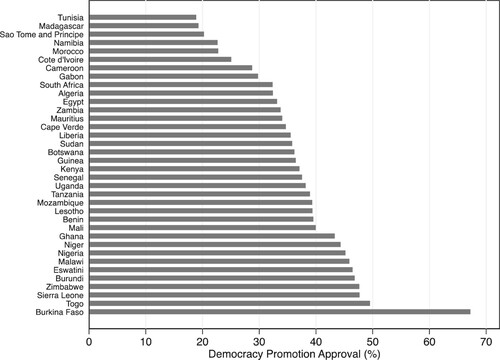

Recent public opinion data from the AfrobarometerFootnote1 reveal variation in public preference for such external actor involvement in promoting democracy. In the sixth round of the Afrobarometer conducted between 2014 and 2015, respondents were asked whether countries in their respective regions “have a duty to try to guarantee free elections and prevent human rights abuses in other countries in the region” through for example “political pressure, economic sanctions or military force” or that these countries “should respect the independence of other countries and allow them to make their own decisions about how their country should be governed”. The responses, as summarized in below, denote cross-country variation in approval of external democracy promotion activities and serves as another motivation for this study. The figure shows that public approval of external democracy promotion is relatively low. It is only in Burkina Faso where over 50% of respondents indicated their approval of such activities. On average, only 38% of respondents in the 36 countries surveyed approved external democracy promotion activities.

To explain the variations depicted in , I develop three related arguments on how evaluations of past elections and a country’s experience with unconstitutional changes of government influence public approval of external democracy promotion by regional actors. Specifically, I argue that individuals who have a negative evaluation of past elections in their country will be more likely to approve external democracy promotion since such intervention can facilitate improvements in a country’s electoral process. Additionally, individuals in countries with a history of unconstitutional changes of government such as coups d’état will also be more likely to approve external democracy promotion activities since past illegal seizures of power may signal fragile democratic institutions in need of third-party pressure to consolidate. Finally, approval of democracy promotion would be higher among those individuals whose countries neighbour states with a history of unconstitutional changes of government since such a history would be indicative of potential challenges to democracy in their neighbourhoods that regional democracy support can mitigate.

The article begins with a review of the literature on democracy promotion, specifically studies on regional organization involvement in democracy promotion, to identify gaps in this body of research that this article aims to fill. Following the literature review, I develop the three related arguments explaining attitudes toward democracy promotion among African citizens. I then test these arguments quantitatively by evaluating data from the sixth round of the Afrobarometer survey. Following a discussion of the findings, I conclude the article with implications and directions for future research.

Literature review

Democracy promotion involves “activities by external actors that seek to support democratization [or] enable internal actors to establish and develop democratic institutions that play according to democratic rule”.Footnote2 These activities include democracy aid targeting civil society and political institutions, political conditionality in foreign aid, economic and other sanctions, and military intervention.Footnote3 Although not new, democracy promotion became particularly integral in the foreign policies of promoter states since the end of the Cold War which was accompanied by the third wave of democratization.Footnote4 Literature on democracy promotion has addressed various themes, notably the motivations of promoters, processes, and activities that constitute democracy promotion, and evaluations of the impact of democracy promotion.Footnote5 However, this review will focus on the place of regional organizations in democracy promotion given this article's interest. It will be observed that despite a growing body of literature that has highlighted how African and other regional organizations promote democracy among their constituent member-states, there is a lack of systematic study on how the public perceives these democracy promotion activities.

Regional organizations have become key to the promotion of democracy. Pevehouse argues that those regional organizations whose majority of members are democracies should be more likely to influence democratization through various processes.Footnote6 These include pressuring “member states to democratize or redemocratize after reversals to authoritarian rule” and socializing elites, particularly the military, “not to intervene in the democratic process by changing their attitudes towards democracy”.Footnote7 Genna & Hiroi further argue that regional organizations promote democracy through democracy clauses embedded in their formal agreements.Footnote8 These clauses serve a democratic conditionality function that clarifies to member-states what would follow actions that breach their agreed commitment to democratic rule including sanctions and suspensions. Yet, Donno observes that the enforcement of sanctions and other punishments as a consequence of violating a regional organization’s democracy clause is varied given that member-states may have competing geopolitical interests that take priority over democracy promotion and the possibility of having incomplete information on violators.Footnote9 These enforcement challenges however can be mitigated through effective monitoring that publicizes and reveals information about norm violations, processes that pressure states to prioritize sanctioning norm violations, and facilitating coordination of collective sanctions against violations.

The case of the European Union (EU) can help us understand how regional organizations through the enforcement of democracy clauses can influence democratization. One can observe the EU’s democracy promotion in its relations with potential member-states, particularly during the accession of Central and Eastern European states. In fact, Dimitrova & Pridham and Ethier argue that the EU has been more effective in promoting democracy to these potential entrants compared to EU’s democracy promotion in other states owing to the tangible reward of full membership that is tied to democratic reforms.Footnote10 Interestingly, the EU’s record in ensuring democracy in member-states does not backslide is mixed particularly for Central and Eastern European member-states. Although the EU has enshrined sanctioning mechanisms to respond to democracy backsliding in member-states, the process of imposing sanctions is complicated by supermajority and unanimity decision-making rules in the European Parliament and Council.Footnote11 Moreover, others find that internal divisions among EU member-states and institutions have limited the emergence of consensus necessary to impose such sanctions.Footnote12

Regional organizations elsewhere have also variedly committed to promoting democracy in their respective member-states. While some of these organizations do include admission criteria urging potential members to be democratic, these are rarely implemented to levels comparable to those of the EU described above.Footnote13 Instead, these regional organizations have focused on improving democracy amongst their bona fide member-states by adopting democracy clauses and treaties specifying actions the organization should take when democracy is threatened.Footnote14 Yet even here, we observe variation in the enforcement of these rules when democracy is under threat. Closa and his colleagues for example observe inconsistencies in the application of these democracy rules among regional organizations in Latin America.Footnote15 Similarly, those examining the AU’s application of its rules against unconstitutional changes of government note inconsistencies with coups receiving more attention compared to other democracy threats.Footnote16

Different accounts have been offered to explain these variations in how regional organizations react to threats to democracy. Some comparing the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and SADC and EU, Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), and SADC have argued that regional organizations are more likely to respond to threats to democracy when reacting is in line with the interests of the regional hegemon in the respective organization.Footnote17 Others have noted that such variations in democracy promotion particularly among African regional organizations (AU and ECOWAS) may be due to the specificity of the actions to be taken as stipulated in democracy clauses and/or treaties of regional organizations.Footnote18 Finally, in evaluations of the AU’s inconsistent reactions to coups and other unconstitutional changes of government, McGowanFootnote19 argues this may be due to weak capacity of the AU while EngelFootnote20 and WittFootnote21 conclude that inconsistencies are due to poor coordination between the AU and other regional organizations in Africa.

The above literature has contributed to our understanding of interstate cooperation aimed at advancing democracy. However, very few studies have systematically investigated public attitudes toward democracy promotion among respondents of potential target states. For example, Marinov finds that “educated and politically sophisticated” Lebanese respondents were more likely to reject external democracy promotion when such promotion was deemed to be partisan.Footnote22 However, most studies that have examined the intersection between public opinion and democracy promotion focus on the attitudes of respondents from democracy promoters such as the United StatesFootnote23 and European Union.Footnote24 This article aims to address this discrepancy in the existing literature by exploring public attitudes among African citizens toward democracy promotion efforts of African regional actors. As highlighted previously in this article, African regional organizations have adopted and enforced various democracy promotion activities following threats to democracy, yet little is known about whether and why citizens of potentially targeted states hold certain perceptions regarding these democracy promotion efforts.

Argument

Why would individuals approve of external actors potentially intervening in their country’s domestic political affairs to promote democracy? I answer this question by developing three related arguments extending from the literature on the consequences of electoral history and unconstitutional changes of government on democracy. I argue that one’s attitudes toward external democracy promotion are framed by their experience with electoral politics, their country’s political history, and the political history of their neighbouring countries. Specifically, those that evaluate the conduct of elections in their country negatively are more likely to approve of external democracy promotion because a history of electoral malpractice signifies weaknesses in the electoral system and democratic institutions and deteriorates public trust and confidence in these institutions to self-correct. The propensity to approve external democracy intervention emerges from the possibility that external actors will motivate improvements in electoral practices that help to strengthen democratic rule.

Concomitantly, individuals whose country has had a history of unconstitutional changes of government and undemocratic rule are more likely to approve of external democracy promotion. A history of coups d’état and governments that upend democratic norms signals the fragility of democracy and the possibility of future threats to democratic and civilian rule for a given country. Individuals in countries with such a political history would therefore be likely to approve of external democracy intervention since external actors can provide additional pressure and more legitimate means to motivate the institutionalization of democratic reforms in their country and region, complementing domestic reformers.

Similarly, individuals may also be influenced by the political trajectory of their neighbouring countries when forming attitudes toward external democracy promotion. While individuals may not be fully aware of the internal politics of their neighbouring countries, they may nonetheless be cognizant of broadly defined threats to democracy, for example, coup occurrences and military rule in neighbouring countries. Individuals from countries neighbouring those with a history of undemocratic politics and rule would therefore be more likely to approve democracy promotion to improve the region’s civilian and democratic rule.

As a quintessential feature of democracy providing the public with a means of choosing their leaders, elections frame individuals’ evaluation of the quality of their country’s democracy. Previous literature has observed that individuals associate elections with democracy and democratic reforms.Footnote25 And although elections do occur in autocratic regimes,Footnote26 evaluating how they are conducted is important to better understand the qualities of elections that make them democratic.Footnote27 Some of these democratic qualities of elections include inclusive and fair participation both for voters and candidates, quality of competition, and legitimacy of the electoral process including whether the election was conducted peacefully.Footnote28 These qualities have been found to shape individual attitudes toward democracy in different ways. For instance, BrattonFootnote29 finds a negative association between the time since the previous electoral power transition and public attitudes toward democracy, a finding similar to that of Moehler and LindbergFootnote30 who report a positive association between elections resulting in turnovers and improvements in public legitimacy towards the democratic process in Africa. Others find that perceptions regarding electoral integrity and the freeness and fairness of elections influence voter turnout and public satisfaction with and support for democracy.Footnote31

If the conduct of elections influences public evaluations of democracy, then it is plausible to expect such evaluations to also affect public attitudes toward external democracy promotion. Negative experiences with elections signify weaknesses in the electoral system and democratic institutions. Widespread perception regarding electoral malpractice “can erode public faith in democracy itself, facilitating democratic backsliding,”Footnote32 “undermines democratic stability” and corrodes “the democratic body politic”.Footnote33 Moreover, trust in a country’s electoral and political institutions including political parties is likely to be weakened owing to a history of electoral malpractice.Footnote34 These perceived weaknesses and mistrust reduce the public’s confidence that meaningful reforms will be pursued by domestic actors toward strengthening democracy, increasing their likelihood of supporting democracy promotion activities from external actors and institutions including regional organizations.

This above expectation is similar to that observed in evaluations of public support for international human rights institutions. Zhou finds that democratic backsliding increases public support for international human rights institutions presumably because “[i]n countries undergoing a deterioration of democratic institutions, citizens lose trust in national governments and place more faith in international institutions”.Footnote35 Elcheroth and Spini similarly conclude that in the former Yugoslavia “when communities collectively experience vulnerability created by systematic flouting of basic principles, they become more critical toward local authorities and more supportive of international institutions that prosecute human rights violations”.Footnote36 Finally, in explaining attitudes toward the International Criminal Court among victims of electoral violence in Kenya, Cody et al report “[f]ew people trusted Kenya’s notoriously crooked courts, […] and as a consequence respondents were more willing to invest hopes in an international court, especially at the outset of proceedings”.Footnote37 Based on this expectation, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Individuals who evaluate elections in their country to be marred by malpractices are more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

Along with electoral malpractice, a country’s history of unconstitutional changes of government informs individuals’ evaluation of the extent of democracy consolidation in their country. Violations of term limits through constitutional amendments reduce fairness in electoral competition, epitomize abuse of power, and represent institutional decay, structural vulnerabilities, and a general deterioration of democracy.Footnote38 Similarly, a history of coups d’état suggests that a country’s democratic institutions may be fragile.Footnote39 Previous research has noted that coups rarely motivate the emergence and consolidation of democracy but can instead usher in further authoritarian rule and repression.Footnote40 Importantly, past coups are argued to increase the risk of later coups,Footnote41 emphasizing the vulnerabilities post-coup democratization processes face.

Given the fragility that coups and other unconstitutional changes of government inflict in democratizing states, I argue that a country’s history of illegal power seizures will influence public attitudes toward external democracy promotion efforts. With a history of unconstitutional changes of government, individuals are more likely to have little faith that domestic institutions are sufficient to ensure illegal seizures do not take place. Instead, individuals will be likely to approve external means of ensuring democratic institutions are respected. These external actors not only complement domestic efforts by providing an additional impetus for consolidating democratic practices but also avail a supplementary and external check on democratic reform processes that deters unconstitutional changes of government.

As noted earlier, most regional organizations in Africa have embraced processes aimed at promoting democracy and discouraging coups and other illegal seizures of power. Those evaluating sanctions of these African regional organizations against coups have observed that member-states of these organizations perceive these punishments as more legitimate compared to sanctions from actors outside Africa.Footnote42 It is therefore plausible to expect citizens of states with a history of illegal power seizures to also find democracy promotion activities of these organizations as legitimate and be more willing to welcome them to safeguard their country’s fragile democracy. I, therefore, propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Individuals from a country with a history of unconstitutional changes of government are more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

Beyond the politics of one’s country, regional trajectories may also matter in shaping public attitudes toward external democracy promotion. Several studies have shown that individual attitudes toward foreign policy decisions are shaped by events outside their countries. For example, in their exploration of public support for military interventions, Falomir-Pichastor et al argue that “the political regime of countries in conflict may also constitute a central contextual factor in people’s support for military interventions”.Footnote43 Their survey experiments reveal that support for military intervention is low “when the target country of the intervention was democratic [… but] support for such intervention increased when a nondemocratic target population supported the belligerent policies of its government”.Footnote44 Closer to this article's interest, Escribà-Folch et al use survey experiments to find that support for specific types of democracy promotion activities among U.S. citizens varies depending on characteristics of the potential autocratic targets: citizens support coercive democracy promotion means when the potential target is under unconstrained military rule while they support less harsh means such as democracy aid for those potential targets that hold multi-party elections.Footnote45

A similar impact of potential target states’ characteristics may influence public approval of external democracy promotion in Africa. Democratic and civilian rule have become key features of post-Cold War African politics. In the past eight rounds of the Afrobarometer survey, over 60% of respondents indicated their preference for democracy. Additionally, the AU and other regional organizations have led efforts in institutionalizing democracy at the regional and continental levels as an aspirational norm for African states. As noted earlier, these African regional organizations have included specific guidelines on democracy and democracy promotion in formal treaties. Furthermore, African regional organizations have also increasingly observed elections in their member-states and have, although variably, responded to threats to democracy and civilian rule, such as coups in their member-states. Under such circumstances, the normative value attached to democracy motivates individuals to approve external democracy promotion not only when their own country’s democracy is perceived as fragile, but also when they observe similar fragility in their neighbours.

While it is unlikely that citizens have complete information on the domestic politics of their neighbouring states, it is plausible that they are aware of drastic and dramatic political trajectories and upheavals in neighbouring states. Military overthrows, for example, receive more international media attention and are marked by the visibility of uniformed armed forces illegally replacing the previous, at times civilian, government. A history of such undemocratic rule in their neighbouring countries signals to individuals the precariousness of democratization efforts in those countries. For individuals, these neighbours could benefit from regional democracy promotion efforts that may assist in strengthening civilian and constitutional rule. I therefore expect:

Hypothesis 3: Individuals from a country whose neighbors have a history of unconstitutional changes of government are more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

Research design

I test this article’s three hypotheses quantitatively primarily using survey data from the sixth round of the Afrobarometer administered in 36 African countries between 2014 and 2015.Footnote46 Afrobarometer is by far the most comprehensive public opinion data source with a wide coverage of respondents from different African countries. The sixth round of the Afrobarometer included questions relevant to this article including individual attitudes toward external democracy promotion. Variables capturing country characteristics such as coups are drawn from a variety of sources as will be discussed in this section.Footnote47 The assembled data are estimated using a multilevel logistic regression model with robust standard errors clustered around countries.

The dependent variable is operationalized from the question asking respondents whether or not they agreed with the following two statements: (1) governments of regional/neighbouring states have a duty to intervene politically, economically and militarily in order “to guarantee free elections and prevent human rights abuses in other countries in the region” or (2) countries in the region “should respect the independence of other countries and allow them to make their own decisions about how their country should be governed”. The question aimed to gauge the strength of respondents’ perceptions regarding the two statements. From this question, I developed a dichotomous variable where 1 indicated those respondents who agreed or strongly agreed with statement 1 and 0 for those who agreed or strongly agreed with statement 2. Admittedly, this question does not ask respondents directly whether they would approve of regional actors intervening in their own country. However, it nonetheless captures the attitudes this article investigates by distinguishing between those likely to accept the involvement of neighbours in domestic political affairs and the more nationalist individuals wary of violations of national sovereignty.

To measure individual evaluation of their country’s electoral practices (Hypothesis 1), I construct a latent variable using a Bayesian approach from an item response theory (IRT) model for ordinal items. Like democracy,Footnote48 respect for human rightsFootnote49 or media freedom,Footnote50 one’s perception of their country’s overall electoral history can be understood as an unobserved attitude influenced by the individual’s experience with different aspects of their country’s elections. Specifically, the IRT model estimates responses from six questions in the Afrobarometer survey asking respondents to evaluate the frequency in which certain (mal)practices occur in elections held in their country. These (mal)practices include the frequency in which (i) votes are tallied fairly in elections held in the country, (ii) opposition candidates are prevented from competing in elections held in the country, (iii) media covers all candidates fairly, (iv) voters are bribed, (v) voters have a genuine choice during elections, and (vi) political violence accompanies elections.Footnote51 The predicted latent variable from the IRT model, Electoral History, ranges between −2.1 and 2.8 with higher values indicative of persistent occurrence of malpractices in a given country’s elections according to the respondent.

To measure a country’s and its neighbours’ past experience with unconstitutional changes of government (Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3), I rely on data from the Global Instances of Coups dataset to develop four variables.Footnote52 Coups d’état have been identified as one of the key challenges to democratic and civilian rule in Africa in the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance. Importantly, the AU and regional organizations like ECOWAS have been particularly active in responding to coups since 1997. First, I code attempted coups, the total number of previous coups attempted in a respondent’s country, and successful coups, the total number of previous successful coups a respondent’s country experienced. Second, I develop indicators of past coup activity for the neighbouring states of the respondent’s country. Neighbouring states are those that share a border with the respondent’s country. For surveyed island countries, their neighbours are defined as those closest to them. Neighbours’ attempted coups is the total number of previous coup attempts experienced by neighbouring states while neighbours’ successful coups is the total number of successful coups that have taken place in neighbouring states.Footnote53

I control for other potential factors that may influence individual approval of external democracy promotion at the individual and country levels. At the individual level, I control for an individual’s preference for democracy (democrat), satisfaction with democracy in their country (democracy satisfaction), and demographic indicators (age, female, and higher education). It may be the case that those that prefer democracy are more likely to approve of means aims at enhancing democratic processes including through external involvement while those satisfied with democracy in their countries are less welcoming of such third-party support. Additionally, those satisfied with democracy in their country may be less willing to support external democracy promotion activities. These variables are derived from responses from the Afrobarometer survey.

At the country level, I control for whether a respondent’s country is democratic and the extent to which that country is neighboured by democracies, the percentage of democracies neighbouring the surveyed country, using the dichotomous democracy indicators of Boix et al.Footnote54 Citizens of democratic countries and those with democratic neighbours may have been socialized to approve external actions aimed at promoting a more open form of government that guarantees political and civil rights. Conversely, it may be that those in non-democratic countries and regions would approve external actions aimed at promoting forms of government that improve civil and political rights.Footnote55 I also control for the extent to which a country’s regime is corrupt using indicators from the Varieties of Democracy dataset.Footnote56 Citizens in a country where political elites and institutions are characterized by corruption may be less trusting of these institutions, as noted in this article's argument, and also be more likely to view external involvement favourably as a way of mitigating these poor-quality institutions.Footnote57 Summary statistics of these variables are presented in the appendix. In the next section, I present and discuss the empirical findings.

Findings

presents estimates of public approval of external democracy promotion in Africa. Five models are presented: The first includes only individual-level variables while the second to the fifth include country-level variables along with indicators of previous coup activity in a respondent’s country and neighbourhood. The results are supportive of this article's arguments. Individuals who indicated a high frequency of electoral malpractice in their country, those residing in countries that experienced a high number of attempted and successful coups, and those with neighbouring countries that also experienced a high number of attempted and successful coups were more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

Table 1. Public approval of external democracy promotion in Africa.

Before discussing findings supporting this article's arguments, three observations can be made based on estimates in . First, the results indicate that those that prefer democracy were more likely to support external democracy promotion. Second, female respondents were less supportive of third-party democracy intervention compared to their male counterparts. This finding is similar to that Gordon reports in their study on public attitudes toward free movement in Africa.Footnote58 Third, citizens of democratic countries and those with a high percentage of democratic neighbours were more likely to approve of democracy promotion by regional actors. Although outside the scope of this study, these findings may be indicative of the normative impact of democracy on individuals motivating them to be more supportive of actions aimed at strengthening democracy in their respective regions.

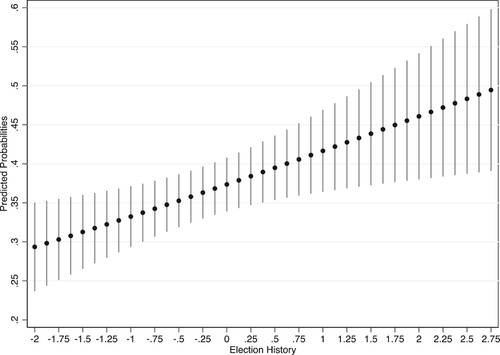

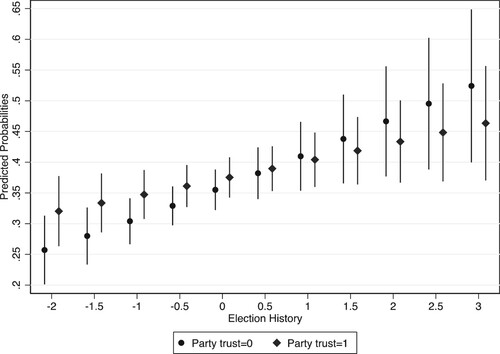

Perceptions regarding electoral malpractices affect public approval of external democracy promotion. Estimates in depict a positive relationship, implying that those who deemed elections in their country to be frequently marred by malpractices were the ones more likely to approve of external democracy promotion efforts. These estimates are summarized in which presents the predicted probabilities for individual approval of external democracy promotion at different levels of Election History. From , those who scored lowest on the latent election malpractice variable, that is, those that believed electoral malpractices never took place in their country, were 29% more likely to approve of external democracy promotion. Conversely, those that perceived the highest frequency of malpractices in their country’s elections were 49% more likely to approve of external democracy intervention.

Figure 2. Election history and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals. The figure is based on estimates from Model 1 of .

Individual experiences matter in shaping their attitudes toward certain phenomena. In their study on Kenyans’ attitudes toward the International Criminal Court, Dancy et al find that those who directly experienced violence following the 2008 elections were generally less likely to perceive the ICC as biased against African countries, a narrative that had been advanced by various politicians in Kenya following the indictments of Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto.Footnote59 This article finds similarly that individual experiences with elections in their country, and specifically the frequency of malpractices including electoral violence and unfair vote counting influence the extent to which they will approve of external actions aimed at advancing democracy and human rights. These experiences inform individuals’ assessment of their country’s electoral democracy, fostering confidence in their democracy and its institutions when electoral malpractices are absent and distrust when such malpractices are prevalent. Distrust in their country’s democratic institutions as a result of a history of electoral malpractices makes it likely that an individual will welcome third-party actions aimed at motivating the consolidation of democracy.

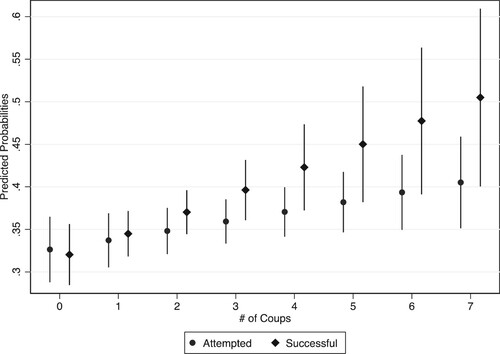

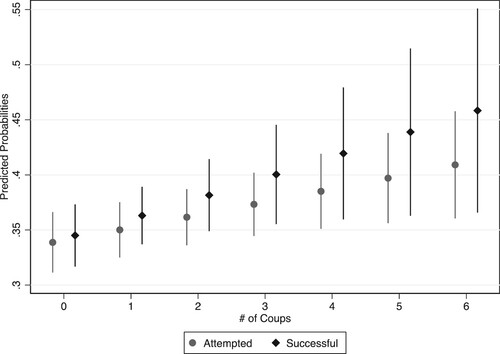

A history of unconstitutional changes of government in one’s country and neighbours also increase the likelihood of public approval of external democracy promotion. Individuals in countries and with neighbours that experienced a high number of attempted and successful coups were more likely to approve of external democracy promotion. As hypothesized, coups signal the fragility of a country’s democracy. This fragility motivates individuals in countries with a history of coups to be more willing to accept third-party intervention aimed at strengthening democracy. To illustrate, citizens of a country like Togo which had experienced seven coup attempts at the time of the Afrobarometer survey were 41% more likely to approve of external democracy promotion by their neighbours compared to a 33% likelihood for citizens of Tanzania that has not experienced any coup attempts. More telling, for citizens of Burkina Faso that had experienced seven successful coups by 2014, the probability of approving democracy promotion activities conducted by their neighbours stood at 51% whereas Botswanans, whose country has not had any successful coups were 32% more likely to welcome their neighbours’ actions in promoting democracy. presents these predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion for the two types of coup events. The differences in probabilities between attempted coups and successful coups are underscored in this figure.

Figure 3. Coups and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

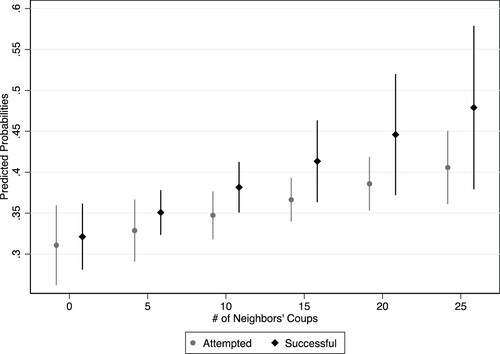

Similarly, past coup activity in states neighbouring the respondent’s country increases the likelihood of approval of democracy promotion by regional actors. Estimates in the last two columns of support this article's third hypothesis: It is in those neighbourhoods with a history of unconstitutional changes of government that we are more likely to witness support for external democracy promotion. presents the predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion for different numbers of attempted and successful coups in countries neighbouring the respondent’s state. Interpreting the probabilities depicted in , citizens of a country like Zambia whose neighbours have only experienced five coup attempts in the past were 33% more likely to approve of external democracy promotion. For Nigerians whose neighbours have experienced 21 previous coup attempts, the likelihood of approving democracy intervention by regional actors was 39%. When successful coups in one’s neighbourhood are considered, Malawians whose neighbours have not experienced any successful coups were 32% likely to approve of external democracy promotion compared to Beninese citizens whose neighbours had experienced 20 successful coups and were 45% more like to approve of regional democracy promotion activities.

Figure 4. Neighbourhood coups and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

Coups provide the background context in which regional actors in Africa have sought to promote democracy. For example, regional and continental actors in Africa responded to coups in Madagascar in 2009, Niger in 2010, and Mali in 2012 with suspensions of these states from participating in relevant regional organizations. In some coup cases, particularly those in West Africa, regional actors have responded with sanctions targeting specific coup plotters. For instance, ECOWAS responded to coups in Guinea-Bissau in 2012, Mali in 2020, and more recently Burkina Faso in 2022 with measures that included targeted sanctions against the military junta. These measures are employed to motivate coup perpetrators to relinquish power and begin the process of restoring civilian and constitutional rule. The visibility of coups as threats to democratic and civilian rule along with recent responses by the AU and other regional organizations may be seen as not only informing the public of the role regional actors can play in discouraging threats to democracy but also in increasing public support for such measures in those states and regions with a history of coup activity.

Additional evidence

Although the above tests provide empirical support for this article's arguments, I present further evidence using different configurations of the data.Footnote60 First, it could be argued that the effect of electoral malpractice on public approval of external democracy promotion is conditional on the extent to which an individual trusts their current ruling party. Those trusting their country’s ruling party may be less inclined to perceive a high frequency of malpractices in their country’s elections given that their party prevailed in the most recent elections. This confidence would in turn suggest that the effect of electoral malpractice on public approval of external democracy promotion is lower for those that trust their ruling party. To test this conditional effect, I include an interaction term consisting of Election History and ruling party trust, a dichotomous variable recoded from the Afrobarometer’s question asking respondents the extent to which they trust the ruling party. graphs the predicted probabilities for public approval of external democracy promotion for those that overwhelmingly trust their ruling party and those that do not have such high confidence. As the figure shows, the differences in probabilities between trusters and non-trusters is not substantively significant to support the proposition that trust in the ruling party mediates the effect of electoral malpractice on public approval of external democracy promotion, although the gradient for the non-trusters slope is slightly greater compared to that of trusters. Instead, both types of individuals are more likely to approve regional efforts at strengthening democracy when they perceive a high frequency of electoral malpractices in their country.

Figure 5. Election history and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion for ruling party trusters and nontrusters. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

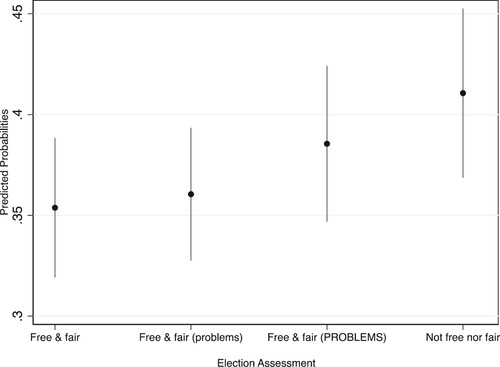

Second, an individual’s perception of electoral practice may equally be near-term, meaning that their most recent electoral experience influences their attitudes toward external democracy promotion. I re-estimated the model, substituting Election History with a variable operationalized from the Afrobarometer’s question asking respondents to evaluate the freeness and fairness of their most recent elections, Election Assessment.Footnote61 graphs predicted probabilities for the different levels of Election Assessment. As the figure reveals, it is among those who assessed their most recent elections to be with major problems (Free & fair (PROBLEMS)) and those that rated their most recent elections as neither free nor fair that support for external democracy promotion was more likely. For those that deemed their elections as either free and fair or free and fair but with minor problems (Free & fair (problems)), support for external democracy promotion was lower.

Figure 6. Election assessment and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

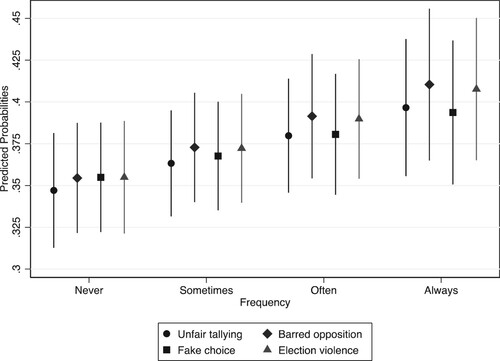

Third, while the latent variable Election History considers six components of electoral malpractices, it could be argued that some of these components are more influential compared to others. I tested the effects of these six components separately to evaluate which specific malpractices matter more for individuals.Footnote62 The estimates reveal that a high frequency of unfair media coverage of candidates and voter bribing are not statistically significant predictors of public approval of external democracy promotion. Undoubtedly, media coverage and voter bribery influence the conduct of elections by affecting how citizens vote. Yet it could be argued that these two instances of electoral malpractice are encapsulated in some of the other four components of manifestations of electoral malpractice. For example, unfair media coverage may be seen as part of attempts to prevent opposition candidates from competing in elections or the presentation of less genuine candidates in elections. Similarly, we may expect less genuine electoral candidates to be the ones engaging in voter bribery.

Instead, it is a history of unfair vote tallying, opposition candidates being barred from competing in elections, unauthentic electoral choices for voters, and a threat of violence during elections that increase the likelihood of support for external democracy promotion. presents the predicted probabilities of these four manifestations of electoral malpractice showing that individuals who noted that elections in their countries were frequently marred by these malpractices were more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

Figure 7. Election history components and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

Fourth, it may be the case that recent and cumulative threats to democratic rule through unconstitutional changes of government resonate more with individuals compared to those that occurred in the past. It has only been recently that organizations like the AU have responded aggressively to such political upheavals making these external reactions more memorable to citizens.Footnote63 Moreover, the effect of unconstitutional changes of government this article examined may be cumulative: an individual’s evaluation of the fragility of democracy in their region may consider both events in their country and those in their immediate neighbours. As such, I re-estimated the model by substituting the four coup variables in with two indicators of the total number of attempted and successful coups since 2003 in the surveyed country and its immediate neighbours. As shown in , individuals whose country and neighbours had experienced a high number of attempted and successful coups since 2003 were the ones more likely to approve democracy promotion activities by regional actors.

Figure 8. Recent coup activity and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

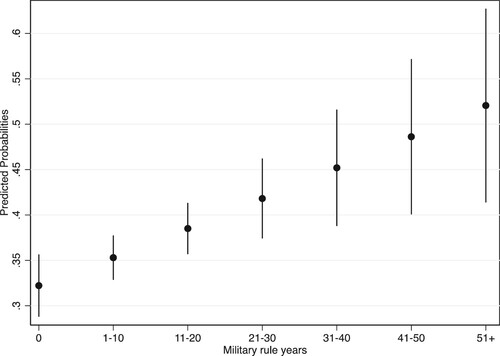

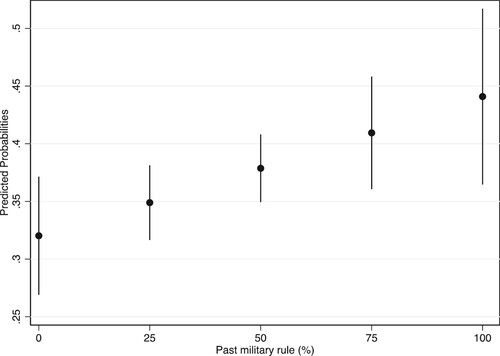

Fifth, whereas coup activity epitomizes a history of unconstitutional changes of government, an equally apt indicator may be the extent to which a given country experienced military rule. Coups, particularly successful ones, are precursors to military governments. Since military rule hardly signals respect for democratic norms and human rights, a history of military rule may motivate citizens to be wary of potential relapses and hence more likely to approve of external democracy promotion. To assess the effect of military rule, I operationalize two variables from the Political Regimes of the World dataset.Footnote64 The first measures the duration of military rule for the surveyed country in years recoded as decades. The second identifies the percentage of the surveyed countries’ neighbours where military rule had the longest duration compared to other regime types.Footnote65 The results, as presented in and , offer further support to this article's arguments. Individuals from countries with a long history of military rule and those with neighbouring countries where military rule lasted longer than other regime types were more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

Figure 9. Military rule and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

In , there is a notable difference between citizens from a country with no history of military rule compared to those from countries that have endured decades of a junta government. To illustrate, a citizen of a country with no history of military rule such as Botswana, Kenya or Senegal was about 32% more likely to approve of external democracy promotion. Contrastingly, a citizen of a country with between 41 and 50 years under military rule such as Burkina Faso or Sudan was 49% more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

Similarly, an individual whose country neighboured those with a history of military rule was more likely to approve of regional actor’s democracy promotion as depicted in . For example, an individual whose country neighbours those that did not have a history of a ruling military regime such as a Malawian was 32% more likely to approve of external democracy promotion whereas those like Nigerians whose country has 75% of neighbours with a history of military rule were 41% more likely to approve external democracy promotion.

Figure 10. Military rule in neighbourhood and predicted probabilities of public approval of external democracy promotion. Notes. Spikes depict 95% confidence intervals.

Finally, the models in were re-estimated with the inclusion of regional fixed effects and without respondents from Burkina Faso. Factors unique to particular regions of respondents’ countries may influence their attitudes toward external democracy promotion, for example, the extensive involvement of ECOWAS in democracy promotion in West Africa compared to regional organizations in Central and North Africa. Additionally, given that an exponential percentage of Burkinabes compared to other countries’ citizens approved of external democracy promotion (see ), it may be argued that this outlier case affects the presented results. The re-estimated results presented in the appendix are consistent with those in and support this article’s arguments.

Conclusion

In this article, I sought to explain why citizens of African countries would approve of external democracy promotion. The arguments developed and tested linked experience with elections and unconstitutional changes of government with public approval of external democracy promotion. Quantitative tests using the sixth round of the Afrobarometer survey provided empirical support for this article's three hypotheses. Individuals that have a negative evaluation of their experience with elections including those recently held in their country and those from countries and regions with a history of illegal power seizures – coup attempts, successful coups, and military rule – were more likely to approve of external democracy promotion.

This article’s argument and findings make several contributions to the study of the international relations of democratization. First, this article contributes to the literature on democracy promotion by situating the attitudes of citizens of potential recipients of external democracy intervention at the front and centre. Previous literature, as I summarized, has paid little to no attention to how and why individuals whose states are targeted for democracy promotion perceive these actions. Second, this article shows how political events in neighbouring states affect attitudes toward democracy promotion. In doing so, this article underscores the importance of considering factors outside the respondent’s country when seeking to explain international actions such as democracy promotion. While individuals in democratic countries may not necessarily expect democracy promotion activities to target them, they may nonetheless support democracy promotion in neighbouring countries with a history of unconstitutional changes of government.

Third, the article’s focus on public attitudes toward actions external states might take provides means of understanding the legitimacy of international actors. Regional organizations in Africa and beyond present themselves as guardians of democracy and in some cases have taken actions to promote human rights and democratic rule. Yet, little is known on the extent to which such organizations and their actions enjoy popular legitimacy. In evaluating public attitudes, this article identifies possible reasons why and under what conditions the actions of international organizations may be deemed legitimate and enjoy popular support.

Yet in its investigation of public attitudes and popular legitimacy of international organizations, this article highlights the need to further examine how citizens of countries that have experienced external democracy promotion in recent years perceive these actions. Admittedly, this article’s empirical tests rely on a measure of potential third-party intervention, although, as noted, the African Union along with regional organizations in Africa have been actively seeking to advance democracy, particularly in countries that have experienced coups in recent years. Anecdotal evidence so far suggests that the public in some of the targeted states is not keen on these democracy promotion actions. For example, Malian citizens in January 2022 protested against further sanctions ECOWAS had imposed on the country’s military junta for delaying elections aimed at restoring civilian and constitutional rule. Examining the motivations of citizens to react to external democracy promotion efforts in this manner helps us understand the sources of and potential ways of improving the legitimacy of such actions of regional organizations. This is especially important at a time when recent coups in Africa have either been preceded by mass protests against the incumbent regime or followed by public celebrations welcoming the military junta.

Appendix (Tables).docx

Download MS Word (40 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mwita Chacha

Mwita Chacha is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science and International Studies, University of Birmingham (UK). His research examines the intersection between regional cooperation, public opinion, and post-coup politics.

Notes

1 Afrobarometer Data, available at http://www.afrobarometer.org.

2 Grimm and Leininger, “Not All Good Things Go Together,” 396.

3 Beichelt, “The Research Field of Democracy Promotion”; Carothers, Aiding Democracy Abroad; Hackenesch, “Not as Bad as it Seems”; and Leininger, “Bringing the outside In.”

4 Carothers, Aiding Democracy Abroad; and Lavenex and Chimmelfennig, “EU Democracy Promotion in the Neighbourhood.”

5 Carothers, Aiding Democracy Abroad.

6 Pevehouse, “With a Little Help from My Friends?”; and Pevehouse, Democracy from Above.

7 Pevehouse, Democracy from Above, 3.

8 Genna and Hiroi, Regional Integration and Democratic Conditionality.

9 Donno, “Who is Punished?”

10 Dimitrova and Pridham, “International Actors and Democracy Promotion in Central and Eastern Europe”; and Ethier, “Is Democracy Promotion Effective?”

11 Holesch and Kyriazi, “Democratic Backsliding in the European Union.”

12 Jenne and Mudde, “Hungary’s Illiberal Turn”; Sedelmeier, “Anchoring Democracy from Above?”; and Soyaltin-Colella, “The EU’s ‘Actions-Without-Sanctions’?”

13 Boateng, “Membership Accession in the African Union”; Hoffmann, “Political Conditionality and Democratic Clauses”; and Spandler, “Regional Standards of Membership and Enlargement.”

14 Closa and Palestini, “Tutelage and Regime Survival”; Powell, Lasley, and Schiel, “Combating Coups d’état in Africa”; Wobig, “Defending Democracy with International Law”; and Witt, Undoing Coups.

15 Closa, Castillo, and Palestini, Regional Organisations and Mechanisms for Democracy Promotion; and Closa and Palestini, “Tutelage and Regime Survival.”

16 Ani, “Coup or not Coup”; Wiebusch and Murray, “Presidential Term Limits”; and Wilén and Williams, “The African Union and Coercive diplomacy.”

17 Hoffmann and Van Der Vleuten, eds., Closing or Widening the Gap?; and Van der Vleuten and Hoffmann, “Explaining the Enforcement of Democracy.”

18 Ateku, “Regional Intervention in the Promotion of Democracy in West Africa”; and Hartmann, “ECOWAS and the Restoration of Democracy.”

19 McGowan, “Coups and Conflict in West Africa.”

20 Engel, “The African Union and Mediation.”

21 Witt, “Mandate Impossible.”

22 Marinov, “Voter Attitudes when Democracy Promotion Turns Partisan.”

23 Brancati, “The Determinants of US Public Opinion”; Christiansen, Heinrich, and Peterson, “Foreign Policy Begins at Home”; Escribà-Folch, Muradova, and Rodon, “The Effects of Autocratic Characteristics”; and Tures, “The Democracy-Promotion Gap.”

24 Faust and Garcia, “With or Without Force?”

25 Bratton, Mattes, and Gyimah-Boadi, Public Opinion, Democracy, and Market Reform; and Cho, “To Know Democracy is to Love It.”

26 Knutsen, Nygård, and Wig, “Autocratic Elections”; and Golosov, “Why and How Electoral Systems Matter.”

27 Lindberg, “Democratization by Elections in Africa.”

28 Ibid.; Moehler and Lindberg, “Narrowing the Legitimacy Gap.”

29 Bratton, “The ‘Alternation Effect’ in Africa.”

30 Moehler and Lindberg, “Narrowing the Legitimacy Gap.”

31 Birch, “Perceptions of Electoral Fairness”; Fortin-Rittberger, Harfst, and Dingler, “The Costs of Electoral Fraud”; Norris, “Do Perceptions of Electoral Malpractice Undermine Democratic Satisfaction?”; and Robbins and Tessler, “The Effect of Elections on Public Opinion.”

32 Norris, “Do Perceptions of Electoral Malpractice Undermine Democratic Satisfaction?”, 19.

33 Lehoucq, “Electoral Fraud,” 249.

34 Aluaigba, “Democracy Deferred”; Mauk, “Electoral Integrity Matters”; and Simpser, “Does Electoral Manipulation Discourage Voter Turnout?”

35 Zhou, “Public Support for International Human Rights Institutions,” 544–5.

36 Elcheroth and Spini, “Public Support for the Prosecution of Human Rights Violations.”

37 Cody et al., The Victims’ Court?, 56.

38 Cassani, “Law-Abiders, Lame Ducks, and Over-Stayers”; Kiwuwa, “Democracy and the Politics of Power Alternation”; and Maltz, “The Case for Presidential Term Limits.”

39 Greene, “Coups and the Consolidation Mirage.”

40 Koehler and Albrecht, “Revolutions and the Military”; and Powell, Chacha, and Smith, “Failed Coups, Democratization, and Authoritarian Entrenchment.”

41 Croissant, “Coups and Post-Coup Politics”; and Hiroi and Omori, “Causes and Triggers of Coups d’état.”

42 Hellquist, “Regional Sanctions as Peer Review.”

43 Falomir-Pichastor et al., “Do All Lives have the Same Value?”

44 Ibid., 354.

45 Escribà-Folch, Muradova, and Rodon, “The Effects of Autocratic Characteristics on Public Opinion.”

46 Afrobarometer Data.

47 Summary statistics are presented in the Appendix.

48 Treier and Jackman, “Democracy as a Latent Variable.”

49 Fariss, “Respect for Human Rights has Improved Over Time.”

50 Solis and Waggoner, “Measuring Media Freedom.”

51 For each question, respondents could choose “never”, “sometimes”, “often”, and “always”. A full description of these questions is included in the Appendix.

52 Powell and Thyne, “Global Instances of Coups from 1950 to 2010.”

53 As hypothesized, coup events are likely to be observable to individuals outside the countries they occur given their suddenness, the drastic regime change they engender, and the visibility of military personnel attempting to overthrow another regime. Using the sum of these coup events taking place in the neighbourhood of the surveyed country captures the magnitude, severity, and persistence of this threat to civilian and democratic rule in that neighbourhood.

54 Boix, Miller, and Rosato, “A Complete Data Set of Political Regimes, 1800–2007.” These dichotomous indicators are appropriate for this study as they capture the key attributes of democracies that are the focus of external democracy promotion activities, competitive free and fair elections and can be operationalized at the regional level when one’s interest is in the extent of democraticness in the neighbourhood of a given state.

55 Zhou, “Public Support for International Human Rights Institutions.”

56 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13.”

57 Simmons and Danner, “Credible Commitments and the International Criminal Court.”

58 Gordon, “Mass Preferences for the Free Movement.”

59 Dancy et al., “What Determines Perceptions of Bias Toward the International Criminal Court?”

60 These additional tests are presented in the Appendix. In conducting these additional tests, I also estimate the data using a multilevel logistic regression model with robust standard errors clustered around countries.

61 Responses to this question were recoded such that those who deemed elections in their country to be not free and fair were coded 4 whereas those that deemed elections to be free and fair were coded 0.

62 These malpractices are: Unfair tallying of votes, opposition candidates barred from elections, unfair media coverage of candidates, bribing voters, lack of genuine electoral choice, and threats of electoral violence.

63 The first suspension of a member-state from the AU following a coup d’état was in 2003 that targeted the junta in the Central African Republic.

64 Anckar and Fredriksson, “Classifying Political Regimes 1800–2016.”

65 Other regime types were presidential, semi-presidential, parliamentary, one-party, personalist, and absolute monarchy rule.

Bibliography

- Afrobarometer Data. [Country(ies)], [Round(s)], [Year(s)]. http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Aluaigba, Moses T. “Democracy Deferred: The Effects of Electoral Malpractice on Nigeria’s Path to Democratic Consolidation.” Journal of African Elections 15, no. 2 (2016): 136–158.

- Anckar, Carsten, and Cecilia Fredriksson. “Classifying Political Regimes 1800–2016: A Typology and a New Dataset.” European Political Science 18 (2019): 84–96.

- Ani, Ndubuisi Christian. “Coup or Not Coup: The African Union and the Dilemma of “Popular Uprisings” in Africa.” Democracy and Security 17, no. 3 (2021): 257–277.

- Ateku, Abdul-Jalilu. “Regional Intervention in the Promotion of Democracy in West Africa: An Analysis of the Political Crisis in the Gambia and ECOWAS’ Coercive Diplomacy.” Conflict, Security & Development 20, no. 6 (2020): 677–696.

- Beichelt, Timm. “The Research Field of Democracy Promotion.” Living Reviews in Democracy 3, no. 1 (2012): 1–13.

- Birch, Sarah. “Perceptions of Electoral Fairness and Voter Turnout.” Comparative Political Studies 43, no. 12 (2010): 1601–1622.

- Boateng, Oheneba A. “Membership Accession in the African Union: The Relationship between Enforcement and Compliance, and the Case for Differential Membership.” South African Journal of International Affairs 24, no. 1 (2017): 21–39.

- Boix, Carles, Michael Miller, and Sebastian Rosato. “A Complete Data Set of Political Regimes, 1800–2007.” Comparative Political Studies 46, no. 12 (2013): 1523–1554.

- Brancati, Dawn. “The Determinants of US Public Opinion Towards Democracy Promotion.” Political Behavior 36, no. 4 (2014): 705–730.

- Bratton, Michael. “The Alternation Effect in Africa.” Journal of Democracy 15, no. 4 (2004): 147–158.

- Bratton, Michael, Robert Mattes, and Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi. Public Opinion, Democracy, and Market Reform in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Carothers, Thomas. Aiding Democracy Abroad: The Learning Curve. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2011.

- Cassani, Andrea. “Law-Abiders, Lame Ducks, and Over-Stayers: The Africa Executive Term Limits (AETL) Dataset.” European Political Science 20, no. 3 (2021): 543–555.

- Cho, Youngho. “To Know Democracy is to Love it: A Cross-National Analysis of Democratic Understanding and Political Support for Democracy.” Political Research Quarterly 67, no. 3 (2014): 478–488.

- Christiansen, William, Tobias Heinrich, and Timothy M. Peterson. “Foreign Policy Begins at Home: The Local Origin of Support for US Democracy Promotion.” International Interactions 45, no. 4 (2019): 595–616.

- Closa, Carlos, P. J. Castillo Ortiz, and Stefano Palestini Céspedes. Regional Organisations and Mechanisms for Democracy Protection in Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union. Hamburg: EU-LAC Foundation, 2016.

- Closa, Carlos, and Stefano Palestini. “Tutelage and Regime Survival in Regional Organizations’Democracy Protection: The Case of Mercosur and Unasur.” World Politics 70, no. 3 (2018): 443–476.

- Cody, Stephen, Eric Stover, Mychelle Balthazard, and Alexa Koenig. “The Victims’ Court? A Study of 622 Victim Participants at the International Criminal Court.” The Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkley, School of Law (November 1, 2015), 2015.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset V13.” edited by Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. 13, 2023.

- Croissant, Aurel. “Coups and Post-Coup Politics in South-East Asia and the Pacific: Conceptual and Comparative Perspectives.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 67, no. 3 (2013): 264–280.

- Dancy, Geoff, Yvonne Marie Dutton, Tessa Alleblas, and Eamon Aloyo. “What Determines Perceptions of Bias toward the International Criminal Court? Evidence from Kenya.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64, no. 7–8 (2020): 1443–1469.

- Dimitrova, Antoaneta, and Geoffrey Pridham. “International Actors and Democracy Promotion in Central and Eastern Europe: The Integration Model and its Limits.” Democratization 11, no. 5 (2004): 91–112.

- Donno, Daniela. “Who is Punished? Regional Intergovernmental Organizations and the Enforcement of Democratic Norms.” International Organization 64, no. 4 (2010): 593–625.

- Elcheroth, Guy, and Dario Spini. “Public Support for the Prosecution of Human Rights Violations in the Former Yugoslavia.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 15, no. 2 (2009): 189–214.

- Engel, Ulf. “The African Union and Mediation in Cases of Unconstitutional Changes of Government, 2008–2011.” In New Mediation Practices in African Conflicts, edited by Ulf Engel, 55–82. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2012.

- Escribà-Folch, Abel, Lala H. Muradova, and Toni Rodon. “The Effects of Autocratic Characteristics on Public Opinion Toward Democracy Promotion Policies: A Conjoint Analysis.” Foreign Policy Analysis 17, no. 1 (2021): oraa016.

- Ethier, Diane. “Is Democracy Promotion Effective? Comparing Conditionality and Incentives.” Democratization 10, no. 1 (2003): 99–120.

- Falomir-Pichastor, Juan M., Andrea Pereira, Christian Staerklé, and Fabrizio Butera. “Do All Lives have the Same Value? Support for International Military Interventions as a Function of Political System and Public Opinion of Target States.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 15, no. 3 (2012): 347–362.

- Fariss, Christopher J. “Respect for Human Rights has Improved over Time: Modeling the Changing Standard of Accountability.” American Political Science Review 108, no. 2 (2014): 297–318.

- Faust, Jörg, and Maria Melody Garcia. “With or Without Force? E Uropean Public Opinion on Democracy Promotion.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no. 4 (2014): 861–878.

- Fortin-Rittberger, Jessica, Philipp Harfst, and Sarah C. Dingler. “The Costs of Electoral Fraud: Establishing the Link between Electoral Integrity, Winning an Election, and Satisfaction with Democracy.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 27, no. 3 (2017): 350–368.

- Genna, Gaspare M., and Taeko Hiroi. Regional Integration and Democratic Conditionality: How Democracy Clauses Help Democratic Consolidation and Deepening. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Golosov, Grigorii V. “Why and How Electoral Systems Matter in Autocracies.” Australian Journal of Political Science 51, no. 3 (2016): 367–385.

- Gordon, Steven. “Mass Preferences for the Free Movement of People in Africa: A Public Opinion Analysis of 36 Countries.” International Migration Review 56, no. 1 (2022): 270–295.

- Greene, Samuel R. “Coups and the Consolidation Mirage: Lessons for Stability in New Democracies.” Democratization 27, no. 7 (2020): 1280–1300.

- Grimm, Sonja, and Julia Leininger. “Not All Good Things Go Together: Conflicting Objectives in Democracy Promotion.” Democratization 19, no. 3 (2012): 391–414.

- Hackenesch, Christine. “Not as Bad as it Seems: EU and US Democracy Promotion Faces China in Africa.” Democratization 22, no. 3 (2015): 419–437.

- Hartmann, Christof. “ECOWAS and the Restoration of Democracy in the Gambia.” Africa Spectrum 52, no. 1 (2017): 85–99.

- Hellquist, Elin. “Regional Sanctions as Peer Review: The African Union against Egypt (2013) and Sudan (2019).” International Political Science Review 42, no. 4 (2021): 451–468.

- Hiroi, Taeko, and Sawa Omori. “Causes and Triggers of Coups D’état: An Event History Analysis.” Politics & Policy 41, no. 1 (2013): 39–64.

- Hoffmann, Andrea Ribeiro. “Political Conditionality and Democratic Clauses in the EU and Mercosur.” In Closing or Widening the Gap?, edited by Andrea Ribeiro and Anna Van Der Vleuten Hoffmann, 173–189. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Hoffmann, Andrea Ribeiro, and Anna Van Der Vleuten. Closing or Widening the Gap?: Legitimacy and Democracy in Regional Integration Organizations. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Holesch, Adam, and Anna Kyriazi. “Democratic Backsliding in the European Union: The Role of the Hungarian-Polish Coalition.” East European Politics 38, no. 1 (2022): 1–20.

- Jenne, Erin K, and Cas Mudde. “Hungary’s Illiberal Turn: Can Outsiders Help?” Journal of Democracy 23, no. 3 (2012): 147–155.

- Kiwuwa, David E. “Democracy and the Politics of Power Alternation in Africa.” Contemporary Politics 19, no. 3 (2013): 262–278.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, and Tore Wig. “Autocratic Elections: Stabilizing Tool or Force for Change?” World Politics 69, no. 1 (2017): 98–143.

- Koehler, Kevin, and Holger Albrecht. “Revolutions and the Military: Endgame Coups: Instability, and Prospects for Democracy.” Armed Forces & Society 47, no. 1 (2021): 148–176.

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Frank Schimmelfennig. “EU Democracy Promotion in the Neighbourhood: From Leverage to Governance?” Democratization 18, no. 4 (2011): 885–909.

- Lehoucq, Fabrice. “Electoral Fraud: Causes: Types, and Consequences.” Annual Review of Political Science 6, no. 1 (2003): 233–256.

- Leininger, Julia. “‘Bringing the Outside In’: Illustrations from Haiti and Mali for the Re-Conceptualization of Democracy Promotion.” Contemporary Politics 16, no. 1 (2010): 63–80.

- Lindberg, Staffan I. “Democratization by Elections in Africa Revisited.” Paper presented at the 103rd annual meeting of American Political Association, Washington DC, 2007.

- Maltz, Gideon. “The Case for Presidential Term Limits.” Journal of Democracy 18, no. 1 (2007): 128–142.

- Marinov, Nikolay. “Voter Attitudes When Democracy Promotion Turns Partisan: Evidence from a Survey-Experiment in Lebanon.” Democratization 20, no. 7 (2013): 1297–1321.

- Mauk, Marlene. “Electoral Integrity Matters: How Electoral Process Conditions the Relationship between Political Losing and Political Trust.” Quality & Quantity 56, no. 3 (2022): 1709–1728.

- McGowan, Patrick J. “Coups and Conflict in West Africa, 1955–2004: Part II: Empirical Findings.” Armed Forces & Society 32, no. 2 (2006): 234–253.

- Moehler, Devra C., and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Narrowing the Legitimacy Gap: Turnovers as a Cause of Democratic Consolidation.” The Journal of Politics 71, no. 4 (2009): 1448–1466.

- Norris, Pippa. “Do Perceptions of Electoral Malpractice Undermine Democratic Satisfaction? The US in Comparative Perspective.” International Political Science Review 40, no. 1 (2019): 5–22.

- Pevehouse, Jon C. Democracy from Above: Regional Organizations and Democratization. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Pevehouse, Jon C. “With a Little Help from My Friends? Regional Organizations and the Consolidation of Democracy.” American Journal of Political Science 46, no. 3 (2002): 611–626.

- Powell, Jonathan, Mwita Chacha, and Gary E. Smith. “Failed Coups, Democratization, and Authoritarian Entrenchment: Opening Up or Digging In?” African Affairs 118, no. 471 (2019): 238–258.

- Powell, Jonathan, Trace Lasley, and Rebecca Schiel. “Combating Coups D’état in Africa, 1950–2014.” Studies in Comparative International Development 51, no. 4 (2016): 482–502.

- Powell, Jonathan M., and Clayton L. Thyne. “Global Instances of Coups from 1950 to 2010: A New Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 48, no. 2 (2011): 249–259.

- Robbins, Michael D. H., and Mark Tessler. “The Effect of Elections on Public Opinion Toward Democracy: Evidence from Longitudinal Survey Research in Algeria.” Comparative Political Studies 45, no. 10 (2012): 1255–1276.

- Sedelmeier, Ulrich. “Anchoring Democracy from Above? The European Union and Democratic Backsliding in Hungary and Romania after Accession.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no. 1 (2014): 105–121.

- Simmons, Beth A., and Allison Danner. “Credible Commitments and the International Criminal Court.” International Organization 64, no. 2 (2010): 225–256.

- Simpser, Alberto. “Does Electoral Manipulation Discourage Voter Turnout? Evidence from Mexico.” The Journal of Politics 74, no. 3 (2012): 782–795.

- Solis, Jonathan A., and Philip D. Waggoner. “Measuring Media Freedom: An Item Response Theory Analysis of Existing Indicators.” British Journal of Political Science 51, no. 4 (2021): 1685–1704.

- Soyaltin-Colella, Digdem. “The EU’s ‘Actions-without-Sanctions’? The Politics of the Rule of Law Crisis in Many Europes.” European Politics and Society 23, no. 1 (2022): 25–41.

- Spandler, Kilian. “Regional Standards of Membership and Enlargement in the EU and Asean.” Asia Europe Journal 16, no. 2 (2018): 183–198.

- Treier, Shawn, and Simon Jackman. “Democracy as a Latent Variable.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 1 (2008): 201–217.

- Tures, John. “The Democracy-Promotion Gap in American Public Opinion.” Journal of American Studies 41, no. 3 (2007): 557–579.

- Van der Vleuten, Anna, and Andrea Ribeiro Hoffmann. “Explaining the Enforcement of Democracy by Regional Organizations: Comparing EU, Mercosur and Sadc.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 48, no. 3 (2010): 737–758.

- Wiebusch, Micha, and Christina Murray. “Presidential Term Limits and the African Union.” Journal of African Law 63, no. S1 (2019): 131–160.

- Wilén, Nina, and Paul D. Williams. “The African Union and Coercive Diplomacy: The Case of Burundi.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 56, no. 4 (2018): 673–696.

- Witt, Antonia. “Mandate Impossible: Mediation and the Return to Constitutional Order in Madagascar (2009–2013).” African security 10, no. 3–4 (2017): 205–222.

- Witt, Antonia. Undoing Coups: The African Union and Post-Coup Intervention in Madagascar. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

- Wobig, Jacob. “Defending Democracy with International Law: Preventing Coup Attempts with Democracy Clauses.” Democratization 22, no. 4 (2015): 631–654.

- Zhou, Min. “Public Support for International Human Rights Institutions: A Cross-National and Multilevel Analysis.” Sociological Forum 28, no. 3 (2013): 525–548.

Appendix

Summary Statistics

Table A1. The conditional effect of election history on approval of external democracy promotion.

Table A2. Assessment of recent elections and approval of external democracy promotion.

Table A3. The effect of Election History components on approval of external democracy promotion.

Table A4. Recent cumulative coups and public approval of external democracy promotion.

Table A5. Military rule and public approval of external democracy promotion.

Table A6. Public approval of external democracy promotion in Africa with regional fixed effects.

Table A7. Models excluding Burkina Faso.