Abstract

The focus of this article is participatory research with and by people with learning disabilities. Drawing on discussions that took place across a series of seminars, we use the concepts of space and boundaries to examine the development of a shared new spatial practice through creative responses to a number of challenges. We examine the boundaries that exist between participatory and non-participatory research; the boundaries that exist between different stakeholders of participatory research; and the boundaries that exist between participatory research with people with learning disabilities and participatory research with other groups. With a particular focus on participatory data analysis and participatory research with people with high support needs, we identify a number of ways in boundaries are being crossed. We argue that the pushing of new boundaries opens up both new and messy spaces and that both are important for the development of participatory research methods.

Introduction

The focus of this article is participatory research with and by people with learning disabilities. For the purposes of this article, we apply an accepted understanding of learning disabilities: Firstly, people with learning disabilities have some form of difficulty with experiencing and acquiring new information. Secondly, this difficulty starts in childhood. Thirdly, the difficulty impacts on people's ability to cope independently (Seale, Nind, and Simmons Citation2013). There is common agreement that the environment can play a particular role in disabling or enabling a person with a learning disability. One example of how people with learning disabilities have been disabled is the way in they have been traditionally marginalized and silenced, which results in their perspectives being consistently ignored (Gillman, Swain, and Heyman Citation1997; Walmsley and Johnson Citation2003). This has led to a call for greater involvement of people with learning disabilities in research as one way to combat this long-term societal exclusion (Townson et al. Citation2004). Participatory research with people with learning disabilities involves collaboration between them and academic researchers whereby people with learning disabilities contribute to the research as active co-researchers rather than passive subjects. The focus of such research is expanding understanding of the experience of living with a learning disability, often with a view to improving their lives in some way. Participatory research with people with learning disabilities therefore emphasizes research partnerships, the sharing of power and transformation of the lives of participants (Zarb Citation1992; Cornwall and Jewkes Citation1995).

The stimulus for this article has been an ESRC funded seminar series that the authors have been involved in called “Towards equal and active citizenship: pushing the boundaries of participatory research with people with learning disabilities” (ES/J02175X/2).Footnote1 There were two underpinning premises of the seminar series: Firstly, that while participatory research in general is not necessarily better ethically, morally or methodologically than any other methodological approach (See Holland et al. [Citation2008]), in the field of learning disabilities it is fundamentally important because it is responsive to calls for political and civic engagement by people with learning disabilities (Barton Citation1999) and to “global concerns with rights and voice” (Nind Citation2011, 350). Secondly, that participatory research is not unproblematic, and further progress in the development of participatory methods will be severely limited without interrogating the claims made regarding outcomes and benefits of participatory research and addressing underdeveloped areas. Over a period of two years a series of five seminars were organized. For each seminar, researchers and practitioners (with and without disabilities) were invited to present their experiences of doing participatory research and to participate in discussions emanating from these presentations.Footnote2

The first seminar sought to set the scene by reviewing what had been achieved in the field so far, identifying where the boundaries were in terms of current achievement. Analyses of the state of the art of participatory research with children and with people with learning disabilities (Walmsley and Johnson Citation2003; Grant and Ramcharan Citation2007; Nind Citation2011) have identified two particular areas in need of further development: (1) the need to extend well developed practices in participatory research into participatory data analysis, and (2) the need to explore how the boundaries of participatory methodologies can be extended to those with severe, profound and multiple learning disabilities who due to their high support needs are at risk of having little opportunity to make decisions regarding their how they live their lives. Given that participatory research is underpinned by partnerships and by the sharing of power, the apparent invisibility of participants with learning disabilities in the data analysis process and the minimal participation of people with high support needs brings into question the claims for truly transformative experiences that academic participatory researchers tend to make. The second and third seminars therefore focused on data analysis and high support needs. The fourth seminar brought together participatory researchers from a range of different fields (learning disability, young children, adults with dementia, mental health) to identify whether and how the boundaries of these fields overlapped. The final seminar was both reflective and practical in nature, seeking to draw out the main messages and ideas across the seminars as well as exploring solutions to issues raised by participants about their own participatory research projects – seeking to enable them to push beyond real or potential barriers to progress.

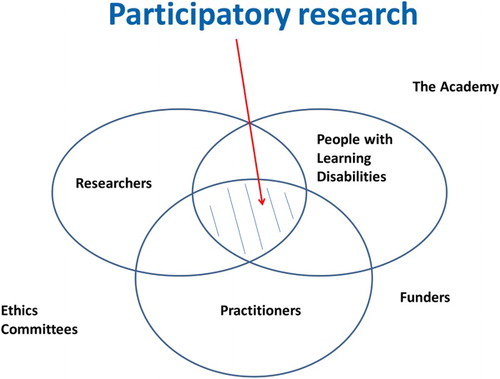

Conceptually, we have always framed the work of the seminar series using notions of boundaries and pushing boundaries. As the series unfolded, however, we came to realize that the research community's understanding of “boundaries” was complex and that this understanding was influenced by an emergent notion of participatory research as a shared space. In the NCRM Research Methods Festival symposium on Inclusive Research: Advances in Participatory Methods and Approaches, convened by co-author Nind, Niamh Moore, a feminist researcher, drew on the ideas of Star (Citation2010) to argue that participatory research is as a “boundary object” because it is a collectively generated shared space.Footnote3 According to Star, an object is something that people act toward and with. Different groups (termed by Star as social groups or communities of practice) can have common objects. These common objects form the boundary between the groups “through flexibility and shared structure – they are the stuff of action.” (Star Citation2010, 603). This conceptualization of shared space has real resonance with the conceptualization of participatory research with people with learning disabilities as discussed across our seminar series. Different social groups: people with learning disabilities, academic researchers and practitioners (see ) come together, joined by a shared interest in improving the lives of people with learning disabilities. Star and her collaborators (Star and Griesemer Citation1989; Bowker and Star Citation1999) conceptualize boundaries as interfaces facilitating knowledge production. They approach boundaries as means of communication, as opposed to division, and show that they are essential to the circulation of knowledge and information across social worlds. This contrasts with a conceptualization of boundaries as markers of difference (e.g. the separation of identities and belonging that is implicit in labels such as disabled or non-disabled; academic not academic). This has resonance with the observation within the seminar series that there were comfortable interfaces between participatory research, inclusive research and feminist research (seminar one) as well as interfaces between participatory research with people with learning disabilities and participatory research with young people, carers of people with mental health issues, or people with dementia (seminar four). Star and colleagues use their understanding of conceptual boundaries to explore how interrelated sets of categories, that is, systems of classification, come to be delineated. Bowker and Star (Citation1999, 5) agree with Foucault that the creation of classification schemes by setting the boundaries of categories “valorizes some point of view and silences another”, reflecting ethical and political choices and institutionalizing differences. This concern is pertinent to participatory research with people with learning disabilities given their long history of being marginalized, as well as the silencing of particular groups, such as those with profound and multiple learning disabilities who require a high level of support in all aspects of their life.

The notion of participatory research as a shared space also has resonance with the ideas of Torre (Citation2005, 258), who writing in the context of racial discrimination referred to “creating democratic spaces of radical inclusivity” and “diverse democratic spaces of inquiry”. In these democratic spaces:

Each participant is understood to be a carrier of knowledge and history; everyone holds a sincere commitment to creating change for educational justice; power relationships are explicitly addressed within the collaborative; disagreements and disjunctures are excavated rather than smoothed over, and there is a collective expectation that both individuals and the group are “under construction.”

The imperative for examining tensions and differences is particularly relevant for the seminar series since one of its aims was to challenge the idea that participatory research is not unproblematic. The presentations within the series certainly identified a number of problems and tensions and the suggested solutions to these problems were many and varied, suggesting that the participatory research community will be “under construction” as it continues to examine and debate these potential solutions.

In this article we use the concepts of space, boundaries and boundary objects as lenses through which to examine the boundaries that were perceived by seminar participants to exist, the extent to which these boundaries have been challenged or pushed, and the opportunities this provides for new spaces to be opened up, some of which may be contested or messy.

Examining the boundaries

Across the five seminars, three different kinds of boundaries were conceptualized by participants: the obvious, though sometimes tenuous, boundary that exists between participatory and non-participatory research; the boundaries that exist between different stakeholders of participatory research with people with learning disabilities; and the boundaries that exist between participatory research with people with learning disabilities and participatory research with other groups.

Boundaries between participatory and non-participatory research

Several seminar participants positioned participatory research with people with learning disabilities as methodologically and qualitatively different to non-participatory research. Participatory research was therefore conceptualized as occupying a different space to other research, reflecting the position taken by Cook (Citation2012, 16), who argues that participatory research inhabits “different spaces and offers different ways of seeing”. For example, in seminar one, Jan WalmsleyFootnote4 suggested that a history of the development of participatory methods can be traced back to self-advocacy, participatory action research, normalization and social role valorization, the social model of disability and co-production. This history means that participatory research with people with learning disabilities is concerned with different questions and outcomes compared to other methods. Val Williams and Andrew Barbour,Footnote5 who argued that participatory research “should not pretend to be the same as other academic research”, reinforced this sense of difference, suggesting that good participatory research has its own quality standards. Similarly, Gordon Grant offered a set of quality indicators, arguing that good participatory involves: using and explaining knowledge contributions from service users and academic researchers; testing each other's knowledge contributions; changing things (services, policies, personal, ideas, and research capacity) and rigor and clarity in data analysis.Footnote6

Despite the sense of difference that seminar participants expressed, there were also times when they challenged the value or benefits of being different, suggesting that the boundaries between participatory and non-participatory research might be blurred in some way. For example, one question raised quite early on in the seminar series was: “what is different or special about participatory research?” Initially when reflecting on this question, participants commented that participatory research required things such as flexibility, trust, rapport, good relationships and respect. The creation of such a list did however cause some to ask “but are these not indicators of all good research?” This raised for some the issue of how helpful it was to position participatory research as different. For example, Nicola Grove argued that we are in danger of participatory research being seen as just “special learning disability” researchFootnote7; which may lead to its dismissal by those conducting other kinds of research. The space that participatory research with people with learning disabilities occupies is therefore not so separate from other research spaces that it is immune to unfavourable comparisons on the basis of quality or importance.

The boundaries that exist between different stakeholders of participatory research with people with learning disabilities

From the discussions across the five seminars there was an explicit understanding that academic researchers and people with learning disabilities shared a research “space”, although this did not preclude them moving in and out of this space, doing other kinds of non-participatory research as well. The academic researchers within this space were often those with a clear commitment to the principles of participatory research, regarded as separate from the wider academy when occupying this different space. Participatory academic researchers tended to feel devalued or ostracized from the wider academic community, which led to them feeling that they continually had to justify the research they did. There was a more implicit acknowledgement that practitioners (e.g. support workers and service providers) also shared the sometimes awkward participatory research space. Support workers play an important role in enabling people with learning disabilities to participate in research (for example through facilitating travel to and from research meetings or using advocacy principles and practices to encourage contribution). They mediate with service providers who are key “users” of the research findings in terms of informing how services might be transformed to improve the lives of people with learning disabilities. The space that is shared by academic researchers, people with learning disabilities and practitioners (see ) could be called a new space or what Hall (Citation2014, 384), writing in the context of inclusive research with indigenous people, called a “third space of understanding”.

In discussing this new or third space however, it was clear that some groups were currently positioned outside the space, for example, the wider academy, ethics committees and most funders (see ). These groups were positioned as either not valuing participatory research or adopting rules and practices that placed barriers in the way of the kind of participatory research that occupants of the space wished to conduct. Common examples given were refusal of funding or risk averse ethical conditions. Seminar participants therefore discussed the problem of how to get their research valued beyond those they saw as already converted to its merits. They identified possible ways of legitimizing their research (e.g. incorporating more theory; using the accepted jargon and language of those outside of the space), but participants worried about how this could be achieved in an inclusive way without compromizing the integrity of the project. One visual image that was offered to represent the influence of these outsiders on the space was the pushing in on boundaries of participatory research, making it a smaller, more confined and therefore a more difficult space to operate in.

In proposing a “third space of understanding”, Hall (Citation2014, 384) argued for “ongoing negotiated reciprocal relationships”, because it is up to those in the relationships to negotiate the way these relationships play out within the immediacy of ever changing interactions and purposes. Discussions held within our seminar series confirmed the need for continued negotiation about what happens within the space. For example, regular seminar participants, Anne Collis and Alan ArmstrongFootnote8 argued for the creation of a new space in which practices moved on from academics involving people with learning disabilities (“my space”) or people with learning disabilities involving academics (“your space”) towards academics and users working together (“new space”). The point they were making is that the participatory research should be jointly initiated or negotiated, carving out new customs away from the other spaces.

The boundaries that exist between participatory research and similar kinds of research

A key focus of the seminar series was the negotiation of boundaries with similar forms of research. An early example of this negotiation was over the use of language. As seminar organizers we had labelled the series as being about “participatory research”, yet frequently the term “inclusive research” was used by participants instead, reflecting an emergent change in language in the UK. For example, in the first seminar drawing on her research with Kelley Johnson, one presenter, Jan Walmsley defined inclusive research as: owned (but not always started) by people with learning disabilities; furthering the interests of disabled people with researchers being “on the side of” people with learning disabilities; collaborative; enabling people with learning disabilities to exercise control over process and outcomes and producing accessible outputs. Walmsley and Johnson (Citation2003) position participatory research as a subset of inclusive research and argue that it is more helpful to use the term inclusive research because it is more readily understood by people with learning disabilities. Like Nind (Citation2014), they are arguing for the blurring and shifting of boundaries between different research communities and approaches. Linked to this, in the fourth seminar, Nind envisioned a “second generation research” that would carve out “new spaces” where there was room for more dialogue across research areas and the development of a more shared language.Footnote9 The first step in this development of a shared language might be the adoption of the term “inclusive research”; the second step might be to agree on the terms used to describe partners in inclusive research. The term co-research is often used, but in a seminar dedicated to identifying common ground between participatory research with people with learning disabilities and participatory research conducted with other groups, Toby Brandon and Caroline KempFootnote10 argued against the term preferring to use “researcher” for all partners in that, “you are either a researcher or you are not.”

In our efforts to scope in more detail what second generation participatory or inclusive research might look like, we sought to contribute to a range of related research communities, not specifically focused on learning disabilities. As we engaged with these communities it became evident that participatory or inclusive researchers working in different fields (to learning disabilities) also conceptualized their research as occupying shared spaces. For example, in a special issue of International Journal of Research and Method in Education on inclusive research in education several authors referred to a social construction of space. In writing about doing inclusive research with indigenous people in Australia, Hall (Citation2014, 387) talked of the challenges of discussing ownership of research in an “academic space”. She suggested the need for a “post-colonial academic space” (388). MacLeod, Lewis, and Robertson (Citation2014, 413) described the follow-up interviews they conducted with autistic learners as dialogues through which “the space between autistic and non-autistic interpretations could be explored and common ground identified”. In discussing their participatory research with university students, Welikala and Atkin (Citation2014) draw on the arguments of Fielding (2004) and Cook-Sather (Citation2006) to position inclusive research as an uncomfortable space and to argue for a new language that recognizes the difficulty of developing shared understandings in such a space. The idea that participatory research is a “spatial practice” (Lefebvre Citation1991; Thomson Citation2007) that involves the “democratic” sharing of spaces (Torre Citation2005) is therefore not unique to participatory research with people with learning disabilities. What is unique however, are the challenges involved in developing a set of shared “spatial practices” with people with learning disabilities. The resolution of these challenges pushes boundaries and in doing so opens up new and messy spaces.

Pushing the boundaries

The presentations in the seminar series illuminated the creative ways in which people were pushing the boundaries of participatory research in response to the challenges of involving people with learning disabilities in data analysis and meaningfully involving people with high support needs in participatory research. For the purposes of this article, we are drawing on the concept of “possibility thinking” in order to define creativity (Craft Citation2002; Burnard et al. Citation2006) as it is useful for understanding the creative process involved. Possibility thinking is a particular part of the process of creative thinking defined as refusing to give up when circumstances seem impossible and using imagination, with intention, to either identify or solve a problem. Burnard et al. (Citation2006) propose that problem finding and problem solving involves the posing, in many different ways, of the question “What if?” In the context of participatory research with people with learning disabilities we would argue that researchers need to counter common questions such as “what if people with learning disabilities find it too difficult to engage in data analysis?” with the question “what if people with learning disabilities could participate in data analysis?” Possibility thinking, through the use of positively framed “what if” questions, might therefore be the catalyst for change in terms of prompting participatory researchers to explore the possibility of doing something which would have been previously considered impossible or unthinkable.

Creative approaches to involving people with learning disabilities in data analysis

In the second seminar on participatory data analysis, all the projects that were presented used familiar qualitative methods to collect data including: videos; interviews; focus groups and observations. The methods used to make analysis of the data collected from these methods accessible to people with learning disabilities varied, however. Some projects used standard coding and thematic analysis techniques, paying attention to the provision of appropriate support and structure to enable this to happen (see note 5).Footnote11 For example, The Carlisle People First Research Team gave two examples of how they thematically analysed data in two projects. In the first project (see note 11) they explained that thematic analysis was influenced by discussions that took place prior to the fieldwork about what might be observed (e.g. power relationships; how non-disabled people exert power over people with learning disabilities by not enabling them to make their own decisions). Using a structured agenda for sessions, analysis then involved: listening to the tapes of the fieldwork; writing down themes from all the interviews on flipcharts on the wall; discussing key extracts and what different people saw and understood from the extracts. In the second project (see note 11) they did a number of things to try to make the analysis process accessible for the researchers with learning disabilities including: making sure that they had pictures of things that people had talked about in their interviews; using easily understandable words and using summary sheets. These summary sheets had all the information in one place. The team cut out all the things they did not want or need and colour coded and themed the rest.

Other projects used less familiar methods such as “research circles”Footnote12 or Comic Strip Conversations.Footnote13 For example, Gudrun Stefansdottir, Olafur Aoalsteinsson and Embla Hakadottir described a programme at the University of Reykjavik where people with learning disabilities study (for a diploma) together with others studying for a degree. (see note 13) As part of the course, students work together on a research project and do joint data analysis. Their methods included use of Comic Strip Conversations, (see note 13) originally designed for people with autism, where speech or thought balloons record talk, thought, and emotion. In offering her view on how do participatory data analysis with people with learning disabilities, Gudrun Stefansdottir argued there is no “one way to do data analysis”.

The methods described here push the boundaries of participatory research with people with learning disabilities because they replicate familiar processes of data analysis while adapting them to be suitable to the challenging contexts in which they are used.

Creative approaches to involving people with high support needs in research

In the third seminar, speakers described a range of creative, sensory methods to engage people with high support needs in research, including: mobile interviews,Footnote14 deconstructed cartoons,Footnote15 and multimedia.Footnote16 For example, Sue Ledger, Sue Thorpe, and Lindsay Shufflebotham (see note 14) gave a presentation focused on Sue Ledger's Ph.D. research on what enabled a small group of people with high support needs in London to remain local, when so many of their peers had been moved out of area. Sue wanted to research with the people themselves, and so this required her to be responsive and flexible regarding the best tools to facilitate this. For example, mobile interviews serendipitously proved to be a powerful way to prompt people recalling past events in their life story. Through the process of putting together people's individual maps, Sue began to trace a collective local history of services, and to identify what helped to keep people local (e.g. respite services). Andy Minnion and Ajay Choksi from the Rix Centre (see note 16) described a recent project involving sensory objects at Speke Hall (a Tudor manor house in England). The aim was to create a series of interactive, multisensory objects that replicate or respond to artworks or other objects of cultural significance in national collections. This was being done by employing people with learning disabilities as participant researchers, who were generating and designing these art objects, so that they cater for a wide and yet targeted range of needs. They described the research process as being like story creation involving: choosing the tools (e.g. particular cameras for particular individuals); visiting Speke Hall and choosing what to record/photograph; reviewing, remembering and sharing what is recorded; organizing the resources in a wiki, adding text, audio etc.; reflecting on the resource and identifying key themes; making an object (baking; electronics made from play dough) and placing all the physical/sensory objects in a box for display.

Projects like the ones described here have developed nuanced processes that fit the context in which they are being implemented. These processes are continually developed throughout the course of the project and can lead to data that would not have otherwise been generated (e.g. Sue Ledger's findings on what helped to keep people local). We acknowledge that, according to some definitions, they may fall beyond the boundaries of participatory research, but they serve an important purpose in calling these boundaries into question.

Within the shared space of participatory research with people with learning disabilities, there appears to be a core set of principles that all members use to form the basis of their research processes, for example being committed to collaborative research that seeks to further the interests of people with learning disabilities. Within this shared space however, there were also examples of how research projects varied significantly from one another, often influenced by local contexts. In this article, we have labelled these as examples of creativity or pushing the boundaries. Star's (Citation2010) conceptualization of boundary objects, offers an explanation for this variation in processes. Star conceptualized boundary objects as residing between groups and as being inherently ill-structured, having a vague identity. This vagueness means that groups may not always achieve consensus. This does not stop them from co-operating however. Instead, when necessary, local groups (subsets of the larger groups) tailor the object to their local uses. In doing so, they do not necessarily reject the common wider object, rather they “tack back and forth” between the common object and their more localized object” – between the ill-structured and the well-structured. Boundary objects are therefore subject to reflection and local tailoring. Hence, every time people with learning disability, practitioners and academics come together to undertake research, they will occupy a new space – locally negotiated – with agreed rules and ways of working that are situated in the context and time in which they are operating. An example of locally agreed rules and ways of working might include agreements over whether or not the academic will lead on data analysis which may be influenced by the history of the relationship between the academic and people with learning disabilities (see next section).

Messy spaces

We have argued that the boundaries of participatory research with people with learning disabilities have been pushed through the use of a range of creative and contextualized methods and in doing so have created the potential for the opening up of new spaces. Our seminar discussions also revealed a number of tensions and disagreements, suggesting that such boundary pushing has also revealed small cracks and fissures in the boundaries of the participatory research community. It is our contention that these cracks and fissures create what Torre (Citation2005) called a “messy social space” where people with different perspectives “meet, clash and grapple with each other” (Pratt Citation1992, 4). This messy space is not necessarily a threat to the participatory research community, rather an opportunity to creatively analyse differences (Fine, Weis, and Powell Citation1997). In other words, messy social spaces create openings for analysis. Three examples of such messy spaces are disagreements about whether data analysis with people with learning disabilities is simple or complex, differences in ideas about who should lead in in participatory data analysis and concerns over whether the requirements of ethics committees can be married with the principles of participatory research.

Can people with learning disabilities readily participate in data analysis?

There were disagreements amongst seminar participants regarding whether data analysis is something in which people with learning disabilities can readily participate. Some of the researchers collaborating in doing analysis argued for conceiving of data analysis as simple. For example, Val Williams and Andrew Barbour argued that: “Data analysis is not magic, it does not have to be done by scientists and there are no right methods”. (see note 5) They went on to suggest that analysis is always from somebody's point of view so there should be no issue when people with learning disabilities engage in analysis. Furthermore, people with learning disabilities bring with them their direct experience, which enriches analysis. “We should not apologize or worry about this”, Val and Andrew argue, instead, “we do need to be reflective”. Carlisle People First Research researchers saw data analysis as possible for people with learning disabilities to engage in because it can be done in many ways and does not have to rely on writing. One way in which the team tried to make analysis more accessible was to offer alternative terms and definitions that might assist a shared understanding of what analysis is and does. For example, they stated that analysis is “just another word for understanding and explaining what we found out about”. Lou Townson summed up the position of the team by saying:

I thought analysis was complicated; for some people it might be. Some assume only academics do analysis and don't find it difficult but even they can find it difficult. Researchers with learning disabilities may not get a chance to do it because others make an assumption that it is too difficult or there is no time for the process.

Melanie Nind however identified the tensions around the fact that that accessible research is about making things simple, while analysis is not always about making things simple; for qualitative researchers it is about understanding and retaining all that is complex and messy.

There was no resolution to this disagreement and it is something that needs further examination. However, perhaps the way forward lies in the statement by the Carlisle People First Research Team that data analysis can be done “in many different ways”. There may be different levels and kind of analysis and each will differ depending on who is doing the analysis or the purpose of the analysis. The project described by Val Williams and Andrew Barbour would be a good example of this: where simple thematic analysis undertaken by the researchers with learning disabilities is complemented by a more complex conversational analysis undertaken by the academic researcher. While we would not advocate excluding people with learning disabilities from the process of analysis, it might need to become a rich mix of what they bring and what academics bring. In this way the process is enhanced rather than reduced.

Who should take the lead in data analysis?

There were key differences between the projects presented in the seminars regarding who in the team led the data analysis. For some projects, the academic researcher conducted the first round of analysis and then consulted with the researchers with learning disabilities. For other projects, researchers with learning disabilities conducted the first phase of analysis and then shared it with academic researchers. (see note 5) One example of academics conducting the primary analysis is the “All We Want to Say” project presented by Marie Wolfe, Josephine Flaherty, Siobahn O’ Doherty and Edurne Garcia IriarteFootnote17 from The Irish Inclusive Research Network. This project aimed to explore what life is like for people with learning disabilities in Ireland and how life could be better. Workshops were held to recruit and train people with learning disabilities to run the focus groups. The focus groups were audio-recorded. The academics transcribed these and then picked out nineteen themes that they thought were important. It was at the point that the people with learning disabilities joined with the academics, looked at the nineteen themes and decided which were important. Similarly, Ruth Garbutt described a project about sex and relationshipsFootnote18 in which analysis of video data involved the academic researcher making a long list of “important” points and then the wider team reducing this to a shorter list of priorities.

When these projects were presented, there were some questions about the extent to which a project could be genuinely participatory if the academics took the lead in the analysis. An alternative position however, could be to acknowledge that different participants will control the space (take the lead) depending on the context and circumstances in which the research is being conducted. For example, in seminar four, when talking about participatory research with young people, Sally HollandFootnote19 acknowledged that sometimes the open spaces offered to young people in an effort to give them control and choice were actually disconcerting spaces for young people, as they lacked focus. This experience is echoed by Thomson (Citation2007, 2009) who conceptualizes participatory research with children as a “spatial practice” in which spaces for life experiences to be discussed may be closed (or invited) spaces, directed by the researcher, or claimed, created spaces in which participants can create new power and possibilities themselves. Furthermore, as Seale, Nind, and Parsons (Citation2014, 351) argue in conducting participatory research in education:

It is often problematic to commence with a research space that is too wide and open – a blank slate of possibilities may not be helpful. Instead, the people we engage with in the research process often require and value some initial ideas and suggestions (from academic researchers) as a starting or discussion point.

Perhaps the main point that most participatory researchers would agree on is that, irrespective of how open or closed the space is, a key reference point for participatory research needs to be the “worldview” (Hall Citation2014, 377) of the marginalized group becoming involved.

The issue of who should lead on data analysis links to debates regarding capacity-building and whether offering ‘training’ for people with learning disabilities to enable them to do things like analyse data is simply another form of oppression. For example, valuing academic skills of analysis above other skills that people with learning disabilities may have (see Nind et al. Citation2015 for a more detailed discussion).

Can the requirements of ethics committees be married with the principles of participatory research?

Negotiating the development of practices within the inclusive research space seemed particularly fraught when it came to the governance of ethics, with seminar participants talking repeatedly of their frustrations with ethics committees. Seminar participants seemed to feel they were faced with an impossible choice: They could choose to adopt practices that would be approved of by ethical committees, but may not necessarily reflect what they conceived of as the true principles of participatory research, or they could seek to maintain their own personal ethical stance as participatory researchers, but run the risk of not being able to proceed with the planned research due to lack of formal ethics committee approval. This raised the question of whether the two were mutually exclusive or whether ethics committees could support researchers to manage the journey of participatory research with people with learning disabilities with integrity. This question was particularly evident in relation to participatory research with people with high support needs. Seminar participants highlighted the contradictions between the Mental Capacity Act, which can be interpreted as offering opportunities for people with learning disabilities opportunities to be involved in research and the actions of ethics committees who appeared to be risk averse in that they tended to assume that any barriers to informed consent were insurmountable. Examples shared within the seminars suggested that this was not the case and that innovative approaches to informed consent could be married with the legal requirements set out under the Mental Capacity Act. Appropriate proxy informed consent combined with assent could be ascertained, but this involved careful development of relationships and rapport (with individuals and their circle of support). A clear example of this was the research conducted by Debby Watson with children with profound disabilities.Footnote20 In her presentation, Debby argued that while the issue of consent is complex and ongoing the ethical involvement of her participants was achievable. In the context of Debby's research it mostly involved looking for adverse reactions and lots of checking with other people who knew the child well. This kind of ethical practice may be unfamiliar to members of ethical committees but perhaps needs more recognition and negotiation.

Critics of boundary object theory have argued that it does not take into account instances when boundary objects are unable to facilitate a smooth negotiation and crossing of boundaries, for example, the boundaries between participatory research with people with learning disabilities and ethics committees. Lee (Citation2007, 313), for example, argued that boundary object as a concept was incomplete because the active and chaotic negotiation processes that take place at boundaries was missing. Lee proposed the need for “boundary negotiating artefacts” that cause sufficient conflict at the boundaries of spaces or communities in order to necessitate the creation of information from scratch, rather than from a particular social world. Boundary negotiating artefacts also facilitate the pushing and establishing of boundaries between communities as well as the crossing of those boundaries. In our final seminar of the series, we invited researchers to share their research problems with us with a view to stimulating potential creative solutions to these problems. Sue Ledger and colleagues who had recently been appointed as researchers to an AHRC funded project focused on creating a learning disability digital archive, shared with us their desire to create a consent process that would be sensitive to the needs of the project and the ethics committee. The creation of this new consent process protocol may be an example of a “boundary negotiating artefact” if it encourages the two communities to start from scratch with regards to their conceptualization of ethical practice. Alternatively, participatory research may be example of one of those boundary objects that Fujimara (Citation1992) suggests is just too flexible, having too wide a margin of negotiation, so that there will always be limits to the extent to which it can be accepted across different groups or communities.

Conclusion

In this article we have used the concepts of space and boundaries as lenses with which to examine the spatial practice of participatory research with people with learning disabilities. Using the debates that arose from a funded seminar series as a stimulus for this examination e have argued that the development of this spatial practice faces unique challenges but that creative methods are being developed in response to these challenges that is contributing to the emergence of a shared new space.

Participatory research is underpinned by a number of core principles or values. Our examination of participatory research with people with learning disabilities however lends support to the argument that it is unhelpful to adopt an overly idealistic view of participatory research that ignores the problems, complexities or tensions that arise when trying to enact these values. There will not always be a smooth negotiation or crossing of boundaries, but there may sometimes be creative responses to the problems, complexities or tensions that mean that participatory research with people with learning disabilities can contribute to the pushing and extending of boundaries. In so doing, people involved in participatory research may challenge the extent to which its’ own boundaries are pushed and affect the extent to which the spaces within them are confined.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2. All the presentations and summaries of group discussions can be downloaded from the project blog http://participat.blogspot.co.uk/.

11. http://www.slideshare.net/Jane65/brief-notes-on-our-different-approaches-to-analysis-example-1 and http://www.slideshare.net/Jane65/brief-notes-on-our-different-approaches-to-analysis-example-2.

12. http://www.slideshare.net/Jane65/doing-it-together-an-aspie-eye-on-the-neurotypical-researchers-analysis and http://www.informationr.net/ir/15–3/colis7/colis707.html.

13. http://www.slideshare.net/Jane65/glrushow-fyrir-manchesterdata-analysis-from-a-disability-course-for-university-education-for-people-with-learning-difficulties and http://www.autism.org.uk/living-with-autism/strategies-and-approaches/social-stories-and-comic-strip-conversations/what-is-a-comic-strip-conversation.aspx.

16. http://www.scribd.com/doc/205350403/Doing-research-with-people-with-disabilities-using-new-media.

References

- Barton, L. 1999. “Developing an Emancipatory Research Agenda: Possibilities and Dilemmas.” In Articulating with Difficulty: Research Voices in Inclusive Education, edited by Peter Clough and Len Barton, 29–39. London: Sage.

- Bowker, G., and S. L. Star. 1999. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Burnard, P., A. Craft, T. Cremin, B. Duffy, R. Hanson, J. Keene, L. Haynes, and D. Burns. 2006. “Documenting ‘Possibility Thinking’: A Journey of Collaborative Enquiry.” International Journal of Early Years Education 14 (3): 243–262. doi:10.1080/09669760600880001.

- Cook, T. 2012. “Where Participatory Approaches Meet Pragmatism in Funded (Health) Research: The Challenge of Finding Meaningful Spaces.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13 (1): Art. 18. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201187.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2006. “Sound, Presence and Power: ‘Student Voice’ in Educational Research and Reform.” Curriculum Inquiry 36 (4): 359–390.

- Cornwall, A., and R. Jewkes. 1995. “What is Participatory Research?” Social Science and Medicine 41 (12): 1667–1676. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S.

- Craft, A. 2002. Creativity and Early Years Education: A Life Wide Foundation. London: Continuum.

- Fine, M., L. Weis, and L. Powell. 1997. “Communities of Difference: A Critical Look at Desegregated Spaces Created for and by Youth.” Harvard Educational Review 67 (2): 247–284. doi: 10.17763/haer.67.2.g683217368m50530

- Fujimura, J. H. 1992. “Crafting Science: Standardized Packages, Boundary Objects, and ‘Translation’.” In Science as Practice and Culture, edited by A. Pickering, 168–211. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Gillman, A., J. Swain, and B. Heyman. 1997. “Life History or ‘Case History’: The Objectification of People With Learning Disabilities Through the Tyranny of Professional Discourses.” Disability and Society 12 (5): 675–694. doi:10.1080/09687599726985.

- Grant, G., and P. Ramcharan. 2007. Valuing People and Research: The Learning Disability Research Initiative. London: HM Government.

- Hall, L. 2014. “’With” Not “About’ – Emerging Paradigms for Research in a Cross-Cultural Space.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 37 (4): 376–389. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2014.909401.

- Holland, S., E. Renold, N. Ross, and A. Hillman. 2008. Rights, “Right on” or the Right Thing to do? A Critical Exploration of Young People's Engagement in Participative Social Work Research. NCRM Working Paper Series 07/08. Accessed March 14. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/460/.

- Lee, C. P. 2007. “Boundary Negotiating Artifacts: Unbinding the Routine of Boundary Objects and Embracing Chaos in Collaborative Work.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 16: 307–339. doi:10.1007/s10606-007-9044-5.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- MacLeod, A. G., A. Lewis, and C. Robertson. 2014. ““Charlie: Please Respond!” Using a Participatory Methodology with Individuals on the Autism Spectrum.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 37 (4): 407–420. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2013.776528.

- Nind, M. 2011. “Participatory Data Analysis: A Step Too Far?” Qualitative Research 11 (4): 349–363. doi:10.1177/1468794111404310.

- Nind, M. 2014. What is Inclusive Research? London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Nind, M., R. Chapman, J. Seale, and L. Tilley. 2015. “The Conundrum of Training and Capacity Building for People with Learning Disabilities Doing Research.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. doi:10.1111/jar.12213.

- Pratt, M. L. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge.

- Seale, J., M. Nind, and S. Parsons. 2014. “Inclusive Research in Education: Contributions to Method and Debate.” International Journal of Research & Method In Education 37 (4): 347–356. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2014.935272.

- Seale, J., M. Nind, and B. Simmons. 2013. “Transforming Positive Risk Taking Practices: The Possibilities of Creativity and Resilience in Learning Disability Contexts.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 15 (3): 233–248. doi:10.1080/15017419.2012.703967.

- Star, S. L. 2010. “This is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origins of a Concept.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 35 (5): 601–617. doi:10.1177/0162243910377624.

- Star, S. L., and J. R. Griesemer. 1989. “Institutional Ecology, “Translations” and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology 1907–39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (3): 387–420. doi:10.1177/030631289019003001.

- Thomson, F. 2007. “Are Methodologies for Children Keeping them in Their Place?” Children's Geographies 5 (3): 207–18. doi:10.1080/14733280701445762.

- Torre, M. E. 2005. “The Alchemy of Integrated Spaces: Youth Participation in Research Collectives of Difference.” In Beyond Silenced Voices: Class, Race and Gender in United States Schools, edited by L. Weis and M. Fine, 251–266. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Townson, L., S. Macauley, E. Harkness, R. Chapman, A. Docherty, J. Dias, M. Eardley, and N. McNulty. 2004. “‘We are All in the Same Boat’: Doing ‘People-Led Research’.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 32 (2): 72–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2004.00282.x.

- Walmsley, J., and K. Johnson. 2003. Inclusive Research with People with Learning Disabilities: Past, Present and Futures. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Welikala, T., and C. Atkin. 2014. “Student Co-inquirers: The Challenges and Benefits of Inclusive Research.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 37 (4): 390–406. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2014.909402.

- Zarb, G. 1992. “On the Road to Damascus: First Steps Towards Changing the Relations of Disability Research Production.” Disability, Handicap & Society 7 (2): 125–138. doi:10.1080/02674649266780161.