ABSTRACT

This article offers insights into how digital methods in cultural heritage settings can help evoke and illuminate the richness of visitor engagement and interpretation, especially in relation to expressions of ownership. Drawing on the Artcasting research project, which examined how galleries can inventively evaluate visitors’ engagement with art, we propose that, in addition to looking for commonalities and stability in visitors’ articulation of engagement, it is beneficial to look for ways to make sense of difference. The project drew on theories of mobility to explore visitor engagement with cultural heritage, creating an artcasting platform that invited visitors to ‘cast’ artworks to another place or time. We analyse artcasting data through two ‘movements’. The first uses thematic analysis of artcasts to show how visitors to two ARTIST ROOMS exhibitions expressed ownership in relation to their engagement with artworks. The second demonstrates how individual responses can be put into relationship and understood as an articulation of engagement that moves beyond the interpretive authority of the gallery or any one visitor. The article contributes new perspectives to understandings of articulation and engagement and their relationship to the production of heritage, and reflects on implications for moving digital practice towards more complexity and diversity.

Introduction

In museums and galleries, visitors ‘perform their own heritage’ in ways that are ‘facilitated from being at – and revisiting – the heritage site… interpretations emerge from reflecting on their own histories along with objects and environments at the heritage site’ (Haldrup and Bœrenholdt Citation2015, 60). This article explores how visitors can use inventive mobile methods to articulate their engagement with artworks in and beyond gallery settings. We argue that this articulation is an expression of a sense of ownership that characterises the transformation of art objects into heritage. We analyse the divergent forms articulation takes and theorise how they can be brought into relationship with each other.

The research that underpins this article comes from the 2015–16 Artcasting project, funded by the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council. As part of the project, we built an experimental digital methodology and mobile application (app) called ‘Artcasting’ to explore how galleries can inventively evaluate visitors’ engagement with art, and make that process of evaluation part of the experience of engagement. Artcasting was piloted in two ARTIST ROOMS exhibitions in the UK – Roy Lichtenstein at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, Scotland, and Robert Mapplethorpe: The Magic in the Muse at the Bowes Museum in County Durham, England.

An artwork is encountered as heritage at a given place or time through a combination of factors including its location (such as presence in a gallery), interpretative material that accompanies it, its aesthetic qualities, its perceived value, viewers’ previous experience of the work or similar work, and the idiosyncratic associations and values that those who view it might bring. Together, these constitute what Harrison (Citation2015) refers to as ‘properties that emerge in the dialogue of heterogeneous human and non-human actors who are engaged in keeping pasts alive in the present, which function toward assembling futures’. For those who used the Artcasting app, it became one of these actors, contributing to the ‘cultural processes and activities that are undertaken at or around’ things (Smith Citation2006, 3) and which make them into heritage.

In this project, we sought mobilities-informed, more-than-representational methods that would help us think beyond ‘striving to uncover meanings and values that apparently await our discovery, interpretation, judgement and ultimate representation’ (Lorimer Citation2005, 84), to explore the complexities of interpretation and heritage-making. In the Artcasting project, this meant developing an approach that allowed visitors to articulate how the artworks they encountered entered into the ‘flows’ of their own lives and became heritage (Waterton and Watson Citation2013, 552) – for example through associations with memory. The app invited visitors to digitally move or ‘cast’ artworks into other places and times, and to re-encounter and respond to artworks from beyond the gallery space. Visitors created brief geo-located narratives that responded to the question ‘where and when do you want to send this artwork to, and why?’. The aim was to provide a creative prompt for visitors to articulate personal connections to and interpretations of artworks, capturing a moment of the ‘dynamic intersections of people, objects and places’ (Waterton and Watson Citation2013, 553) that constitute heritage, and leaving a permanent digital trace of those moments, to be revisited at other times by gallery staff, other visitors, and the original Artcaster themselves. The locations, journeys, narratives and encounters captured in the Artcasting app form the empirical foundation for this article.

The project worked with mobilities theory to understand engagement itself as mobile, moving through and beyond the space and time of the gallery. However, mobilities theory did more than provide a rationale for the project’s design-based methods and its reimagining and reconfiguring of methods of engagement, both of which are discussed in the methodology section. The same theoretical framework pushed us beyond a thematic analysis that looked for commonalities in visitors’ experiences. In its emphasis on the only temporarily stable nature of interpretation, mobilities theory offered new ways to make sense of difference. This led to a key insight, discussed in the ‘Movement 2ʹ section: that ownership in the context of engagement with and interpretation of heritage can be generatively understood and represented in terms of divergence and diversity. By making such diversity explicit, and offering both visitors and galleries access to representations of difference, findings from the Artcasting project suggest that expressions of engagement, including those that suggest a sense of ownership of cultural objects and artworks, are unstable, provisional and mobile. This article contributes to an understanding of heritage-making by making this mobility visible and showing how interpretations intersect and diverge, in the context of imaginative digital engagement with artworks.

Articulating engagement with cultural heritage

A focus on and attempt to foster greater visitor engagement with cultural heritage locations, institutions and objects has been understood as a response to declining attendance figures (Simon Citation2010); an educational goal (Hooper-Greenhill Citation1999); a consequence of the digital age (Kidd Citation2014); a policy priority (Black Citation2005, 1); and a moral or ethical imperative linked to the rights of the public to have access to cultural institutions (Ashley Citation2014). Visitor engagement with cultural heritage in institutional settings comprises a range of activities and experiences, including interaction with exhibitions and cultural objects, and participation in the creation or production of cultural heritage materials, exhibitions, and organisations themselves. Making participation visible and measurable forms an important basis for institutions’ understanding of how engagement is taking place, and what visitors might be learning from their engagement, and reflects the current performative and evaluation-centred climate in the cultural sector (see Ross et al. Citation2017).

Gallery educators seek ways to maximise active and visible participation through a combination of in-gallery, classroom-based, and digital interventions. Simon (Citation2010, no page) defines a ‘participatory institution’ as ‘a place where visitors can create, share, and connect with each other around content’, and defines content as ‘the evidence, objects, and ideas most important to the institution in question’. Her emphasis on design for participation may be a useful response to what Roberts (Citation1992) identified as the ‘footnoting’ of visitor experience and affect in favour of ‘“real” more serious goals that describe what visitors will come away knowing’.

The Artcasting project explored how engagement could be expressed or articulated, through the development of a new method of responding to artworks. There are several meanings of the term ‘articulation’, two of which are especially relevant to this research. First, the project sought new approaches to encourage visitors to make and express connections with artworks by answering a provocative question (‘where and when do you want to send this artwork?’) and by using the Artcasting app to digitally move the artwork to the chosen time and location. The range of visitor responses to this provocation are discussed in the section of this article titled ‘making the interpretive trace’. This analysis is indebted to the well-established body of research examining how visitors interpret exhibits and cultural heritage objects (Hooper-Greenhill Citation2000; Falk and Dierking Citation2013). It also emerges from literature examining how digital practices support visitor interpretations (Coenen, Mostmans, and Naessens Citation2013) and the sharing of responses to cultural heritage, for example through social media:

Viewing texts from other students and their perspectives brought an understanding of peers’ feelings, interests and actions. The texts displayed on the phones’ screens became, to a certain extent, objects for discussion. (Charitonos et al. Citation2012, 816)

Second, we sought to understand these traces of engagement as a ‘joint’ – made up of a gathering of social, technological, imaginative and communicative resources which is highly mobile (double-jointed, or hypermobile) (see ‘hypermobilising the trace’, below). We consider articulation in its sense of ‘jointedness’ to be a process that creates as much as expresses an experience. In encountering Artcasting, we expected that visitors would construct their account of connection, desire and movement in partnership with the objects, processes, environments and social relationships surrounding the experience. In other words, Artcasting (or any form of articulation of engagement) does not offer a direct window into individual experience of the artworks or exhibition, and so we cannot seek an unmediated response to an artwork. While acknowledging the considerable philosophical debate about the nature of aesthetic response and preference (Neill and Ridley Citation2013), we theorised that, as Melchionne (Citation2010) puts it, people are often in a state of ‘affective ignorance’ in relation to their own aesthetic experience, so are not necessarily trustworthy reporters of their inner states of engagement or emotion. A better approach is to ask whether the articulation that makes up an artcast is generative: whether it provides a lens through which visits and artworks can be engaged with in a variety of ways. This reflects a belief that the meaning of objects and exhibitions is ‘never fully completed’ (Hooper-Greenhill Citation2000, 118), and nor is the experience of engagement with those objects. Individuals’ expressions of engagement with particular artists or artworks as heritage and in heritage locations are therefore of value – instrumentally, in the context of evaluation of the impact of cultural heritage; and theoretically, in the insights they generate into the intra-actions that constitute heritage. Harrison (Citation2015) explains that heritage:

involves practices which are fundamentally concerned with assembling and designing the future – heritage involves working with the tangible and intangible traces of the past to both materially and discursively remake both ourselves and the world in the present, in anticipation of an outcome that will help constitute a specific (social, economic, or ecological) resource in and for the future.

The contributions of digital and mobile processes – for example, the algorithmic surfacing of particular resources as a visitor browses or searches a digital collection – are important factors in many kinds of heritage experiences and the meanings made of them. Tools and methods such as Artcasting can capture a sense of ownership of cultural heritage, but cannot make claims for autonomous or static human interpretation in the construction of such ownership. The next section draws some of these factors together into a discussion of mobilities theory and its influence on the Artcasting project.

Mobilities theory and the artcasting project

The Artcasting project sought a richer understanding of arts engagement and evaluation in cultural heritage contexts through a lens of mobilities theory. Mobilities theory sees the idea of the gallery and its material configurations as open to re-imagining and movement. It takes as its starting point ‘the combined movements of people, objects and information in all of their complex relational dynamics’ (Sheller Citation2011, 1), rather than viewing the world in terms of stable locations, individuals or institutions. Across the social sciences and humanities, what is termed the ‘mobilities paradigm’ (Sheller and Urry Citation2006) has had a significant impact on thinking about movement as a social and political, as well as a practical, issue (Cresswell Citation2011). In the context of heritage, Waterton and Watson (Citation2013, 552) characterise mobilities theory as offering ‘critiques of representational thought, a shared appreciation of the complexity of practices and a broadly relational view’.

Artcasting connects with Latour’s (Citation1986) concept of the ‘immutable mobile’ – a term for objects such as ‘writings, documents and illustrations [which] are stable inscriptions that help to bring about new knowledge formation as they focus the gaze and actions of other entities as they travel’ (Ong and Du Cros Citation2012, 2938). Artcasting is an immutable mobile in that it presents:

not just as an app for engaging audiences or gathering data, but also as an “object to think with”: affecting visitors’ encounters with art; foregrounding ideas of movement and trajectory; to develop a digital platform that captures and retains this thinking. (Knox and Ross Citation2016)

The importance of a mobilities perspective for this project ties into a more general need for new approaches to understanding engagement. This need is being acutely felt across the cultural sector as challenges such as the rising popularity of metrics, the relationship between funding and advocacy, and shifting concepts of cultural value come under increasingly intense scrutiny (Crossick and Kaszynska Citation2016).

While mobilities theory has been slow to appear in museum studies literature (though it appears extensively in tourism studies – see for example Bærenholdt et al. Citation2004), increasing attention has been paid to the spatial contexts of museums and galleries. Geoghegan (Citation2010, 1466) draws attention to the relevance of geography to museum studies and suggests that the field is currently in the midst of a ‘spatial turn’, and attention to space and place has appeared in museum studies literature over the past several decades, for example in Stewart and Kirby’s (Citation1998) work on how interpretation transforms space into place, and in Malpas (Citation2008) critique of the idea of virtually simulating cultural heritage environments. Indeed, Hetherington (Citation2014) argues that themes of space appear in many even earlier critical analyses of museums, including those of Benjamin, Adorno and Proust, ‘even if not fully articulated as such’.

Analyses of how curatorial practice constructs space are especially useful in the context of interpretation and articulation of engagement. For example, Bal (Citation2007, 74) describes curatorial practice as ‘scenography’: ‘arrang[ing] objects in a space that, by virtue of the status of those objects as art, becomes more or less fictional. The gallery suspends everyday concerns and isolates the viewer with the art’. Stead (Citation2007) argues that contextualising cultural objects might be problematic for certain values of art and culture as transcendent. Reconsidering these values in terms of space, time and movement can be productive, and lead in surprising directions. For example, aesthetic judgement, awareness and engagement can themselves be thought of in mobilities terms, by considering personal responses and preferences as less fixed than ‘floating’:

Sometimes, we are not sure how we feel about a work of art, but having preferences, or at least thinking we do, is more comfortable than floating in ambivalence. So, we rely on the trappings of conviction to avoid the discomfort of confusion and indifference. (Melchionne Citation2010, 131)

Speaking of the museum or gallery building, Prior (Citation2011, 207) notes that thinking beyond ‘concept, monolith, icon or commodity’ can make opportunities for ‘surprising alterations and interactions – not just grand gestures such as throwing eggs at portraits, but using museums as shortcuts, traversing the collection backwards, or playing with the limits of security’. The extent to which such gestures are welcome varies in different institutions, but some mobility has become increasingly accepted as part of the visitor experience in cultural institutions – including via the presence of digital devices which serve to ‘blur’ the concept of fixed space in favour of what De Souza E Silva (Citation2006) calls ‘hybrid space’. Mobile technologies like smartphones have been the focus of intense interest in cultural heritage spaces, in some ways a direct descendent of handheld materials and devices long part of the experience of cultural heritage settings (Tallon and Walker Citation2008), but in other ways representing wider shifts towards more personal, intimate, mediated and ubiquitous relationships with digital flows and the social world, leading Parry (Citation2008, 191) to describe them as ‘both agents and epitomes of the modern museum’.

Chen (Citation2015, 96) concluded from his analysis of data from the 2011 Pew Internet & American Life Project that ‘mobile technologies have opened up new venues for cultural appreciation’ and that ‘mobile cultural participation reached patrons from broader social strata’, while not appearing to negatively affect levels of in-person participation in cultural activity. It may be, however, that these technologies are changing the character of that participation – caught as they are between sociality, personalisation and private engagement (Parry Citation2008, 184). Beyond the visit itself, mobile technologies and practices are seen as ‘carrying’ experiences ‘across environments and contexts’ (Charitonos et al. Citation2012, 804), and generating ‘interconnected opinion space’, not bound by the time scales of the visit (Charitonos et al. Citation2012, 815). Indeed, more than a decade of sociological and science and technology studies research has explored the use of mobile devices and their impact on memory, connection to place, and social life. These devices participate in the creation of hybrid space, which blurs borders, redefines physical and digital space, and changes communication patterns (De Souza E Silva Citation2006, 274).

In other words, devices and mobile approaches make new arrangements between cultural heritage, movement, and public and private spaces. These new arrangements are being experienced and explored as people use technology to ‘mobilize place and memory together to create new forms of digital network memory’ (Frith and Kalin Citation2016, 44). Place-based forms might be used to ‘remember… pasts’ and ‘write histories’ (Frith and Kalin Citation2016, 44) and to ‘interact with texts produced by other people who have also moved through that physical space’ (Frith Citation2015, 49). Evoking and creating histories through cultural heritage objects is a key dimension of a sense of ownership of those objects, as we will see. Importantly, mobile technologies and practices can urge us to move away from the idea of place and memory as ‘static storage containers of experience’ towards viewing them as ‘dynamic practices that are constitutive of experience’ (Frith and Kalin Citation2016, 53). Multiple mappings of place and meaning, including ‘social, emotional, psychological, and aesthetic’ (Hjorth and Pink Citation2014, 42), emerge from digital mobile practices and artefacts. The Artcasting project asked: how can such mappings be mobilised in the context of cultural heritage engagement?

Methodology

The Artcasting project was designed and undertaken in collaboration with the ARTIST ROOMS programme. ARTIST ROOMS is a collection of more than 1600 works of international contemporary art, jointly owned and managed by Tate & National Galleries of Scotland. ARTIST ROOMS shares the collection in a series of monographic exhibitions throughout the UK in a programme of exhibitions organised in collaboration with local associate galleries. The primary aim of ARTIST ROOMS is to foster creativity, and to inspire visitors – particularly young people. The Arts Council England Quality Principles, including ‘developing belonging and ownership’, ‘being authentic’, and ‘actively involving children and young people’,Footnote1 were piloted by ARTIST ROOMS during the period of this project. These quality principles helped to inform the research approach taken by the Artcasting project, and we focused in particular on the idea of ownership. Developing belonging and ownership is understood by the Arts Council as providing opportunities for decision-making, choice and autonomy (Lord et al. Citation2012). In the context of ARTIST ROOMS, Cairns and Cooper (Citation2013) suggested considering young people’s response to engaging with public artwork exhibitions in light of how they are made to feel welcome as owners of national collections of artwork. While the research approach was informed by the ARTIST ROOMS focus on young people, the data generated by the project was produced by visitors of all ages. Expressions of ownership were a common thread in many of the artcasting responses, among adults as well as young people, and this article explores how the project captured and interpreted these expressions.

The research took as its starting point the problem that engagement, inspiration and active learning are high priorities for museums and galleries attempting to foster connections between visitors and their cultural heritage. However, methods for understanding and evaluating engagement are often constrained, lacking a sense of the richness of participants’ experience or an understanding of the place of those experiences in the context of their lives. As highlighted by the recent AHRC Cultural Value report (Crossick and Kaszynska Citation2016), new approaches for evaluation of engagement are needed, and grappling with the implications of approaches like Artcasting for evaluation was a central element of the project (Ross et al. Citation2017).

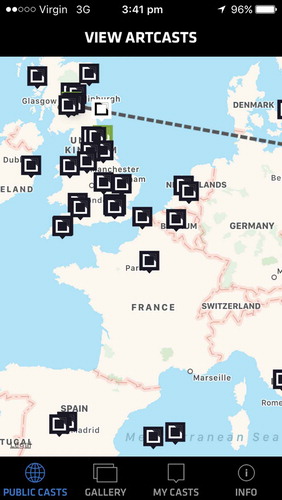

The primary data-gathering method for the research was the Artcasting app. The app was designed and built to capture visitor narratives of the places and times (past, present, future) to which they chose to ‘cast’ (digitally send) artworks from the two exhibitions in which it was piloted. The data generated was a combination of geo-spatial (geographical co-ordinates, also represented as a pin on a map of the world), temporal (the selected time for the cast to arrive and the associated ‘trajectory’ lines on the map showing the current location and direction of casts sent to the future), demographic (the age and postcode data volunteered by some users), and textual (the names given to the cast locations, and the descriptions of the reasons for the choice of time and location) (see ).

The process of designing a new data capture instrument was a key part of the project, with questions of value, mobilities theory and practice, engagement, and organisational issues emerging as topics of discussion and debate during the design phase. These conversations were interdisciplinary by nature and involved members of the research team from education, arts, design and software engineering perspectives. The use of a newly created method for data capture aligned this project with ‘speculative’ or ‘inventive’ methods (Ross et al. Citation2017). As Lury and Wakeford (Citation2012, 7) put it:

the inventiveness of methods is to be found in the relation between two moments: the addressing of a method… to a specific problem, and the capacity of what emerges in the use of that method to change the problem. It is this combination… that makes a method answerable to its problem, and provides the basis of its self-displacing movement, its inventiveness.

Artcasting achieved this combination through the development of a method that addressed the need for capturing different insights into how visitors engage with art, and simultaneously shifted our understandings of the meanings of articulation and engagement. This was apparent from the early stages of the project, when we tested Artcasting as a concept in workshops with young people, and conducted an ‘Explorathon’ drop-in session at the National Galleries of Scotland, using an early version of the app to generate data and gather verbal and written feedback. Along with shaping the design and technical development, participant feedback and the artcasts themselves helped us understand what Artcasting might offer, with one participant commenting:

I don’t know what people in the arts do when they attend to an exhibition like this, but I think that many people just see, think, feel, but do not share their feelings, thoughts nor imaginations with anyone. What you are doing here is providing ways for people to express themselves, to share with others their experience of attending to an exhibition. (attendee at Explorathon event)

Some of the artcast data analysed in this article came from this event (68 casts from 28 participants). The remainder of the data analysed here came from pilots of Artcasting which took place in two ARTIST ROOMS exhibitions in 2015–16: ARTIST ROOMS: Roy Lichtenstein at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (December 2015-January 2016), and Robert Mapplethorpe: The Magic in the Muse at The Bowes Museum (December 2015-April 2016). Initially, use of the app was researcher-led and supported, with drop-in sessions and periods of observation and supported Artcasting taking place between December–April (see ). The Artcasting app was ultimately available for both iOS (Apple) and Android devices. Promotional materials, including leaflets, were available in both settings, and gallery staff were briefed about the app. In total there were 172 downloads of the Artcasting app during the pilot period (151 on iOS, 22 on Android, not including visitor uses of the app on the team’s devices), and 97 artcasts were sent.

The research institution granted ethical approval for the project, and the British Educational Research Association and Association of Internet Researchers’ guidelines were followed in developing the data protection and consent processes. Ethical considerations related to the use of the Artcasting app for data collection, especially informed consent, confidentiality, and its use by young people. The use of the Artcasting app was voluntary, and the app and printed materials described the project and linked to more information. The app launched with a short description of the research and a consent screen, which had to be accepted before participants could continue. Users were asked for their age range and postcode, but this disclosure was optional, and for the use of the research team and galleries only. All other Artcasting data including the choice of location and description of the reason for the cast was publicly available on the Artcasting map, and users were asked to agree to this. Anyone under 16 had their casts held for moderation by the research team to ensure no personally identifying data was shared.

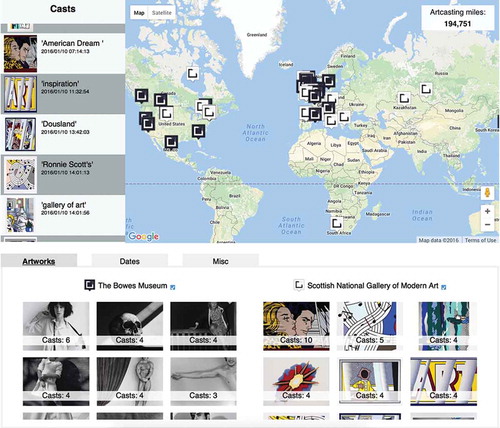

In addition to seeking to understand how Artcasting supported and reflected visitor engagement, the research explored how Artcasting could inform arts evaluation in theory, and in practice – the latter by generating a digital interface that could allow gallery staff to review and analyse artcasts. To accomplish this, we worked with the Institute of Digital Art and Technology at Plymouth University, to build on their ‘Qualia’ dashboard. By plugging Artcasting into this existing platform, we were able to test the flexibility of the approach and build on work previously done to help visualise visitor engagement data (see ).

Starting from the position that data visualisation does not speak for itself, and that the choice of what to visualise affects what can be seen (Kinross Citation1985; Kennedy et al. Citation2016), we considered a number of different possibilities for the dashboard. Ultimately, we sought to visualise Artcasting in terms of intensity of interest in particular artworks, and type and geographical spread of engagement with those artworks, rather than in terms of individual demographics of users. The dashboard made it possible to view the destinations and casts associated with particular artworks, see the overall distance travelled of exhibitions and artworks, and explore the trajectories of artworks through time – factors harder to account for using the textual data alone, and important for the analysis presented here. The figure below shows the elements of each artcast as visualised on the dashboard ().Footnote2

Analysis & discussion

Discussing mobile methods, Büscher, Urry and Witchger (Citation2010, 8) recommend observing the movement of objects. By treating artcasts as digital objects (immutable mobiles) we attempted to maintain their mobility in our analysis by continually returning to questions of travel, trajectory and movement. This section is therefore divided into two ‘movements’, taking into account time, space, imagination, relations, and intensity in an attempt to understand how Artcasting produced a means of articulating engagement with artworks.

An analysis of artcasting texts and locations grouped together into themes helps understand the different ways people connect their own experiences to the artworks they have engaged with, and what this permits and closes off in terms of articulation of engagement and ownership. However, thematic analysis, while productive in drawing out different modes of engagement, is not on its own sufficient to ensure our analysis avoids traps of sedentarism (Cresswell Citation2011, 552). All representations of the Artcasting data involve selecting ways to hold together an unstable articulation of artwork, location and interpretation. As Hooper-Greenhill (Citation2000, 118) writes, ‘any interpretation is never fully completed… The hermeneutic circle is never fully closed, but remains open to the possibilities of change. There is always more to say, and what is said may always be changed. Meaning is never static’. We therefore propose that Artcasting supports the articulation of engagement by:

helping people ‘fit’ experiences with art with their memories, beliefs and relationships (movement one – interpretive traces);

making that fit provisional and showing how it could be different (movement two – hypermobility of the trace).

Movement one looks at the themes emerging from an analysis of Artcasting texts, with a focus on different ways that ownership might be understood through approaches participants took to Artcasting. The Artcasting process disturbs the process of encountering artworks in order to generate and record an interpretive trace. The trace is then digitally ‘cast’ – reaching its chosen location, where it remains available to be recast or reencountered (by the originator or by another user).Footnote3 Movement one engages with these interpretive traces, attempting to see how they have moved and been stilled.

Movement two draws on the second meaning of articulation discussed earlier: articulation as the state of being jointed. We propose the idea of double-jointedness (hypermobility – a condition where joints in the body have more than the usual range of motion) as productive here. By analysing the range of artcasts associated with a single artwork – Lichtenstein’s In the Car – the second movement shows the hypermobility of the joint connecting artwork, visitor, and Artcasting technology. It addresses the notion of doubling, where a copy of the image is sent to multiple locations, and explores this as a mode of articulation which goes beyond the individual visitor.

Movement 1: making the interpretive trace

To understand the interpretive traces generated as visitors selected a destination for artworks in the two exhibitions, and explained their reasons for their choices, this section organises the artcasting data into themes. Data from the ‘name’ and ‘description’ fields of the live Artcasting database and from the Explorathon pilot were coded using Nvivo analysis software. For each of the 167 artcasts included in the analysis, the description (body) and name (title) texts were coded separately, assigned to nodes which reflected the work the cast texts were doing in terms of situating the artworks in place and time, and in terms of the relationship of the cast to its author.

In the initial analysis, we generated 34 ‘body’ nodes and 17 ‘title’ nodes. The most frequently used body nodes are listed in below. As is evident from these, articulation of engagement took multiple forms in the Artcasting data. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the task set for visitors, casts frequently referenced or discussed how the artworks evoke place, with landmarks, cities, cultural locations (such as other galleries), and other specific places appearing in the titles of casts. The most commonly used code reflected how artcasts tended to associate memories of the past with artworks.

Table 1. Partial list of codes from ‘body’ texts of artcasts.

Artcasting as a method offers more than textual data, however. What is innovative about this approach is the connections it makes possible between artwork and place, the geographical and mapping dimension to the casting process, brought together in a process of imagining and realizing mobility of artworks. The dashboard representation of the casts from the pilots usefully visualised these elements, and was an important support for the analysis, providing a multimodal snapshot of the location of artworks in relation to the galleries, and a sense of scale, distance and trajectory.

Codes and visualisations were explored and refined further through subsequent stages of analysis. Here we illustrate participant approaches to ‘stabilising’ the artworks by expressing ownership through the connection of artworks to personal memories, and the use of artcasts as messages to others.

Personal memory

Many of the most detailed casts discussed the ways that artworks provoked personal memories. Sometimes these related to previous encounters with the artist or artworks themselves, or associated memories with the content of the images. In this artcast, the Monet references in Lichtenstein’s Water Lily Pond with Reflections are picked up as a basis for reflection:

Thanks Dad!: My first introduction to Monet was at the Art Institute of Chicago. My father would take me and my 5 siblings to museums. He gave me an appreciation of art and my mother a break at the same time. (explorathon cast)

More frequently, though, casts expressed memories that were associative rather than literal. In this cast of Lichtenstein’s Reflections on Crash, the violent movement depicted in the painting is associated with the collapse of the ‘best house ever built’ – an idyllic summer woodland setting is evoked, and the caster’s younger self’s conviction – perhaps affectionately – deflated:

Tobermory: This artwork reminds me of a treehouse my brother and I built one summer, in the woods by our house. Ramshackle and held together with string and rope, we were convinced it was the best house ever built! It crashed to the ground within an hour of completion. (explorathon cast)

While some memory-related casts were lighthearted, others evoked more serious themes, such as nostalgia for a far away home:

My old home: Lotus is often seen as an Eastern symbol. It reminds me of my home country. The work might appear in a dream of my home. Hmm I really want to have that dream in the bed of my old house. (explorathon cast of Water Lilies with Cloud)

These reminiscing casts (as well as others) were often sent to dates in the past (in the final version, when casting could be through time as well as space – this was not available in the explorathon version). The layering of time, place, artwork and personal reflection could be very powerful:

School: The text on the jacket reminds me of the effort I would put into scrawling my favourite bands’ names all over books and pencil cases. You can see how much music is a visual part of someone’s identity, especially at a young age and this was very important to me growing up. (cast of Mapplethorpe’s Nick Marden, sent to Dublin in the year 1997)

Overall, the memory casts connected artworks with people, places and feelings from the past or from elsewhere, associating these with the subjects, materials and affective qualities of the works themselves. These casts gave the impression of being intensely personal – producing an individual interpretation which, through its detail and specificity, binds artwork, place and time together. In doing so, they illustrate heritage-making in action – in this case, heritage as re-imagining of memory, as Waterton and Watson Citation2013, 830) puts it. Artcasting played a role in legitimising, without reifying, these personal and idiosyncratic interpretations and connections.

Messages

Because the Artcasting platform presented artcasts for others to view or to re-encounter, the process of casting implied an audience, giving a performative dimension to many of the casts. A number of these functioned explicitly as messages or gifts to absent others. Three such casts are discussed here, each demonstrating an approach to appropriating artworks as a way of sending messages through Artcasting, and expressing ownership through the decisions made about the recipient of the message and how the artwork should be communicated to them.

The first cast title was a person’s name (not included here to preserve anonymity), and the text described that person’s potential relationship or engagement with the artwork (Lichtenstein’s Composition I). The cast sender’s affection for the work, combined with the recipient’s connection to the painting’s subject, and the suggestion of what he might do with the cast, combine in this description:

I like the picture and he really likes playing the piano and he is having a baby and I thought he could show it to his little girl when it is born. (cast of Lichtenstein’s Composition I)

Intriguingly, the cast is written in the third person rather than directly to the recipient, and this is also the case with the other ‘message’ casts. A second audience is therefore implied – perhaps the public, or the gallery. Understanding who Artcasting users think they are communicating with would be a valuable follow-up to the data generated in this project.

Another message artcast is directed to a historical figure – da Vinci – whose Vitruvian Man was evoked for this visitor by Mapplethorpe’s Self Portrait, 1975, which they cast to the 17th century (). The date of the cast (1602) is not historically accurate for da Vinci, but the intention for the cast to reach him is clear. Like the previous cast, the sender expresses a personal opinion about the artwork, and also suggests what the recipient might do as a response to the cast. Here the interaction and possible future engagement around the artcast is wholly imaginary, but the artist has been brought to life through this articulation of desired connection.

Figure 5. ‘Da Vinci hometown: i [sic] would like da Vinci to see how art is in the 21st century because I think he would love to get into photography. this [sic] reminds me of his drawing of the man in the circle. I love his cheeky face, like he’s saying yes it’s a classical reference but it’s me as well.’. Artwork: Self Portrait, 1975 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

![Figure 5. ‘Da Vinci hometown: i [sic] would like da Vinci to see how art is in the 21st century because I think he would love to get into photography. this [sic] reminds me of his drawing of the man in the circle. I love his cheeky face, like he’s saying yes it’s a classical reference but it’s me as well.’. Artwork: Self Portrait, 1975 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.](/cms/asset/b7977eaa-935c-4c61-8d90-85048932b2f5/rjhs_a_1493698_f0005_oc.jpg)

Another of these ‘message’ casts came from a visitor who identified as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP), and who cast Mapplethorpe’s Lowell Smith to Brussels as a reminder to their colleagues and themselves ().

Figure 6. ‘European parliament: this is a reminder to me and my fellow MEPs to look after and welcome people fleeing conflict who are hanging onto life in the most difficult of circumstances’. Artwork: Lowell Smith, 1981 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

The performative quality of this cast comes not only from our awareness of the intended audience, but from the explicitly political message the cast sends, potentially controversial at the time, as it referenced contemporary debates about migration and asylum in Europe. The artwork, here, is used as part of a political performance – it acts on a political world to which the caster belongs, and brings the artwork into that world. This is especially striking in contrast with the ‘official’ interpretation of the work given by Tate, which discusses its composition and potential sources of inspiration, but does not attempt to interpret its meaning (Tate Citationn.d.). This artcast is a powerful example of how the negotiation of meaning around artworks as heritage is never completed, and how understanding of an object or artwork comes through construction of patterns in an attempt to ‘mobilise meaning’ rather than by ‘being fed information or having an experience’ (Hooper-Greenhill Citation2000, 117). Official interpretation only forms part of the pattern – sometimes a very small part, as we see here. Taking ownership of artworks, claiming them through interpretation, may transform their meanings well beyond what the gallery or museum would expect. There is risk, as well as opportunity, in making these transformations visible in the way Artcasting (and other forms of user-generated creation) does.

All three of these casts offer intriguing forms of interpretive trace: by deploying the artwork as part of a message for specific recipients, these artcasts take the invitation to re-locate artworks and bring new people into their articulation, producing an additional dimension to the configuration of art and place which constitutes the heritage being created. The artworks become agents, which are propelled forward with specific, if temporary, meanings in tow. This is an example what Harrison (Citation2015) refers to as the ‘remaking’ of the world that heritage practices involve.

Movement 1 demonstrated common approaches to artcasting that express ownership in relation to the artworks by associating them with personal memories or involving them in messages to others. The combination of openness and constraint produced by the question of where artworks should be sent gave visitors some creative license, but the tendency of casts to ‘settle’ around particular modes of response enabled us to approach them thematically, as we have done here. However, a thematic analysis misses some of the instability of Artcasting as a process and approach, as the second ‘movement’ of our analysis shows.

Movement 2: hypermobilising the trace

Lichtenstein’s In the Car was one of the most frequently cast artworks, with nine artcasts from the live pilot and eight from the Explorathon event (). We discuss seven of these in this section to show how, along with the possibility of grouping individual casts into thematic categories, a mobilities approach to analysis permits close attention to diversity and difference. This offers a second perspective on ownership, one that focuses on how personal responses, like those discussed in the previous section, can be put into relationship with one another and understood as an articulation of engagement that moves with and beyond the interpretive authority of the gallery, or any one visitor. Using the metaphor of hypermobility (double-jointedness), we can explore what Bal (Citation2006, 531) means when she describes an exhibition as a conversation where ‘the event is reiterated in each visit, in each act of confrontation between viewer and show’.

In the Car’s text on the National Galleries of Scotland web site identifies the theme of the painting as romantic, discusses its ‘monumental’ scale, and says:

[Lichtenstein’s] paintings present archetypal images of contemporary America, simultaneously glamorous, mundane, dramatic and impersonal. (National Galleries of Scotland Citationn.d.)

However, the gallery’s interpretation forms a backdrop, at most, for the range of associations made in artcasts of In the Car. These associations diverge greatly from the gallery's interpretation, and from each other. A simple example of this hypermobility is seen in the two In the Car casts sent to New York City.

Grubby: Destination after a long drive from boston in a blizzard

This cast appears to reference a specific personal experience. The title might describe the state of the passengers or vehicle, or a quality of the destination. Driving in a blizzard evokes a degree of tension or anxiety, and the ‘long drive’ connects to the subject, and perhaps the mood, of the painting.

(1) there [sic] sort of style: it looks like it comes from there

The second New York cast is more general and vague, and refers to the destination as ‘there’, indicating a certain detachment. The ‘sort of’ in the title suggests a cast relatively uncommitted to the specificities of New York City, perhaps informed by a stereotypical image of the city rather than personal experience. The style of the painting is referenced, rather than its subject.

Already in these two casts we begin to see how interpretation around a single painting diverges – a single location generates two quite different short casts.

Looking at two of the more detailed casts (both sent to locations in Edinburgh during the Explorathon event) augments this sense of divergence:

(3) Granton:hub at Madelvic House: This is the location of the madelvic factory, the first factory to build electric car in the 19th century!!! This Lichtenstein work illustrates a car scene which seems a perfect match

(4) My study: The story is simply throwing out of the it. It makes you wonder what’s going on. And you also seem to know because it is so direct with showing the emotions and potential relationships between the two people. I like putting this kind of work in my study. Stimulating?

Cast 3 refers to an arts centre in the Granton area of Edinburgh, and the history of the building it is housed within. The ‘perfect match’ is the car scene shown in the painting and the identity of the hub building as a former car factory. The link to manufacture of cars in this destination is distant in space and time from the official ‘placing’ of the artwork (‘contemporary America’). The cast puts a very present-day preoccupation (electric cars) into a different time period (the 19th century), so the interpretation plays with time as well as space.

Cast 4 sends the painting to the caster’s study, and addresses a viewer of the cast as ‘you’. The conversational tone and intimate or personal setting for the cast aligns with the light-touch reflective question at the end – ‘Stimulating?’ – in reference to having this kind of work in his or her study. The cast expresses a tension around viewing the work – that it provokes curiosity but also illustrates emotions directly. Knowing/not knowing what is happening in the painting is stimulating (maybe) for this visitor.

A similar domestic setting is the location for the fifth In the Car cast:

(5) Location of my flat in 1983!!! I had a copy of this poster, fake black and white version, sent to me by a friend from Leeds. The poster was framed in very modern frame, and was hanging in my living room. I still have it, though it now sits in my loft…

This cast traces the movement of a version of this artwork from a friend in Leeds to a central location in the caster’s home (a living room in Brussels) to a storage area (a loft) in their current home, all over a thirty-year period. The poster is described as ‘fake’, but is valued enough to keep. Associations between place, memory and art are made explicit here:

(6) Royal Academy (sent to 1991): The Pop Art show, Royal Academy was the first time I saw Lichenstein (and others) work up-close. Huge impression.

(7) Wellingborough: My brother loves Pop Art and has just moved house. I think he’d be delighted to encounter this icon in his home town!

These two casts reference the art historical period of the painting, and the significance of Pop Art for the caster (cast 6) and the caster’s brother (cast 7), as well as this work in particular (‘this icon’). The casts are both personal (‘huge impression’; ‘delighted’) and express ‘official’ knowledge of the artwork and its time.

Cast six locates the artwork in the place and time where the caster first saw it; cast seven’s destination is the new home of the caster’s brother. The span of time (15 years) and different purposes for locating the artworks (a memory and a message) again demonstrates the divergence of interpretations as visualised by artcasting.

Through these seven casts of a single artwork, we can understand the provisional nature of ‘fixing’ locations and interpretations for artworks, and how Artcasting keeps things moving by confronting visitors and gallery staff with hypermobility – the double- (or multiple-) jointedness of the point of engagement. In this way, Artcasting is not simply a collection of reflections of individual visitors, but a mode of articulation that becomes more mobile and more meaningful as it is seen in terms of its trajectories and layers of interpretation. This serves to problematise any straightforward or apparently transparent understandings of a sense of ‘ownership’ of cultural heritage, in favour of a more complex idea of what such a sense might mean, and how galleries and museums might work to capture and use it. The final section of this article discusses the implications of such an approach.

Conclusions

This article presented the concept and practice of Artcasting as a theoretically informed example of mobilities thinking and how it can deliver insights for cultural heritage research and practice. Artcasting was an explicit response to the need for more imaginative approaches to evaluation of engagement and learning in cultural heritage contexts, and an exploration of how engagement and evaluation could be brought more closely together (Ross et al. Citation2017)

Our analysis of the data generated with the Artcasting app shows the possibility of examining visitor responses to shed light on an issue of importance to cultural heritage educators and evaluators – that of ownership – and to complicate and enrich the picture of what this entails. As with all forms of evaluation which actively seek responses from individuals about their affective states or opinions, the data generated through Artcasting is one story of interpretation. Artcasting was able to surface the complex articulation of engagement that any exhibition or artwork provokes – there is no ‘pure’ state of engagement which could alternatively be captured, only more or less generative, and generous, approaches to trying to understand what is meaningful and significant to particular visitors at particular moments in time.

The thematic analysis of artcasts helped to establish more or less stable traces of expressions of ownership, through ‘memory’ and ‘message’ casts. The variety of approaches to Artcasting, the personal connections with artworks and the diversity of associations made indicate that inviting connections between place, movement, and artworks could lead to expressions of ownership that drew from but also went beyond the interpretations offered by the galleries. Artcasts are examples of the ‘complex occurrences of materialities that occur around us, and the affects that we participate in relationally with them’ (Crouch Citation2015, 188).

Using a mobilities-informed analytic approach, these traces can also be destabilised or hypermobilised, exposing these expressions of ownership as a more volatile articulation of engagement that can move in multiple directions away from a single point (in this case, the Lichtenstein painting In the Car). The two movements presented here are therefore in productive tension with each other. This tension speaks to the value of a mobilities approach which does not settle around a single lens of interpretation but insists that interpretation, like the objects that spark it, is ambiguous and shifting:

it is always possible to take an individual object and place it in a new framework or see it in a new way. The lack of definitive and final articulation of significance keeps objects endlessly mysterious – the next person to attach meaning to it may see something unseen by anyone else before. (Hooper-Greenhill Citation2000, 115)

The Artcasting project focused on supporting visitors to articulate their responses to artworks using a method that was provocative, performative, and attuned to the mobilities of interpretation, engagement and ownership. This mobility, and the sparking of expressions of ownership through the question of where and when an artwork belonged, created new articulations (when compared with, for example, the other kinds of evaluations undertaken by ARTIST ROOMS – see Cairns and Cooper Citation2013 for an overview of these). The capture of these articulations constitutes a contribution and valuable step forward in our understanding of how heritage is performed at an individual level through the production of memory and messages; and at a collective level through the hypermobility of interpretation.

The research also contributes an analysis of how ownership can be understood in relation to the diversity of how visitors engage with cultural heritage. By examining the variety of ways in which people were able to engage with interpreting artworks and the places and times they evoke, the project developed and theorised representations of difference. A key finding, we suggest, is that ownership is both provisional and unstable, gathering richness as it moves through time and space along the multiple trajectories that are created by inviting visitors to cast artworks.

This matters in theoretical terms, but it also has practical implications for the work of gallery educators and evaluators. Viewing ownership as diverse and provisional can ultimately enrich the visitor experience by encouraging cultural heritage institutions to take more account of this diversity in how they engage with visitors and represent their voices. Furthermore, engaging with creative and inventive modes of generating data about visitor experiences can support cultural organisations themselves to claim greater agency in relation to the evaluation process. Artcasting was developed as a methodology that could provoke and capture multiple and highly divergent articulations of engagement with artworks. It demonstrates that there is no single or simple message that can be given to funders and other stakeholders about the impact or value of an exhibition or programme of engagement, and that there are alternatives to evaluation methodologies that seek solely to instrumentalise or quantify impact (Ross et al. Citation2017). There is more that could be done to explore what audiences – particularly young audiences – do with a sense of ownership, and longitudinal studies investigating traces through time of co-creative activities like Artcasting would be of great value. What we can say, though, is that gallery educators need resources and approaches that help them insist on the value of divergence, multiplicity and diversity in the ways visitors make and understand connections with art.

Hetherington (Citation2014) argues that ‘the challenge for the museum as archive has always been a gatekeeping one in relation to [an] unspecified realm of the outside. And yet its continued presence is really what makes museums interesting’. Defending and centring such complexity and divergence in evaluation, visitor engagement and educational practice helps cultural institutions play their vital role as places that can account for the complexities of what engagement can mean. Each artcast – each provisional articulation of place, engagement, artwork and technology – performed and mobilised heritage. Artcasting left traces of these performances, making them available for analysis and a richer understanding of individuals’ heritage-making at a moment in time, and of the hypermobility of interpretation and its trajectories through and beyond the gallery.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues at National Galleries of Scotland, Tate and the Bowes Museum for their significant contributions to the research. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers of this article for their detailed and helpful comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council, grant number AH/M008177/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jen Ross

Jen Ross is a senior lecturer in Digital Education, and co-director of the Centre for Research in Digital Education (Digital Cultures). She publishes on online and open education, digital cultural heritage learning, digital cultures and futures, and online reflective practices.

Jeremy Knox

Jeremy Knox is co-director of the Centre for Research in Digital Education (Data Society) and a lecturer in Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh. His research interests include critical posthumanism and new materialism, and the implications of such thinking for education and educational research, with a specific focus on the digital.

Claire Sowton

Claire Sowton is a researcher and project and communications manager at the University of Edinburgh. Her recent research has focused on digital and mobile approaches to engagement and evaluation of cultural experience.

Chris Speed

Chris Speed is Chair of Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh where his research focuses upon the Network Society, Digital Art and Technology, and The Internet of Things. He has sustained a critical enquiry into how network technology can engage with the fields of art, design and social experience through a variety of international digital art exhibitions, funded research projects, books journals and conferences.

Notes

2. Missing from the dashboard visualisation is the date the cast was sent to (visitors were invited to cast to the past or future, as well as the present). This information is noted in the analysis that follows, where relevant. Some demographic data relating to age and postcode were collected from visitors on a voluntary basis, but because many casts were sent from shared devices during drop-in sessions, or the information was not given, it is not included in this analysis.

3. The re-encountering functionality of Artcasting was conceptually important for the project, but is not reflected in the data for both technical reasons and reasons of scale. To read more about re-encounters and their significance, please see Ross et al. (Citation2017).

References

- Ashley, S. L. T. 2014. “‘Engage the World’: Examining Conflicts of Engagement in Public Museums.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 20 (3): 261–280. doi:10.1080/10286632.2013.808630.

- Bærenholdt, J. O., M. Haldrup, J. Larsen, and J. Urry. 2004. Performing Tourist Places. London: Ashgate.

- Bal, M. 2006. “Exposing the Public”. A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by S. Macdonald, 525–542. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/doi/10.1002/9780470996836.ch32/summary.

- Bal, M. 2007. “Exhibition as Film.” In Exhibition Experiments, edited by S. Macdonald and P. Basu, 71–93. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Black, G. 2005. The Engaging Museum: Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement. Abindgon: Psychology Press.

- Büscher, M., J. Urry, and K. Witchger. 2010. Mobile Methods. Abindgon: Routledge.

- Cairns, S., and H. Cooper. 2013. “ARTIST ROOMS Evaluation: Summary and Recommendations”. Sam Cairns Associates.

- Charitonos, K., C. Blake, E. Scanlon, and A. Jones. 2012. “Museum Learning via Social and Mobile Technologies: (How) Can Online Interactions Enhance the Visitor Experience?” British Journal of Educational Technology 43 (5): 802–819. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01360.x.

- Chen, W. 2015. “A Moveable Feast: Do Mobile Media Technologies Mobilize or Normalize Cultural Participation?” Human Communication Research 41 (1): 82–101. doi:10.1111/hcre.2015.41.issue-1.

- Coenen, T., L. Mostmans, and K. Naessens. 2013. “MuseUs: Case Study of a Pervasive Cultural Heritage Serious Game.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 6 (2): 8. doi:10.1145/2460376.2460379.

- Cresswell, T. 2011. “Mobilities I: Catching Up.” Progress in Human Geography 35 (4): 550–558. doi:10.1177/0309132510383348.

- Crossick, G., and P. Kaszynska. 2016. Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture: The AHRC Cultural Value Project. Swindon: Arts and Humanities Research Council.

- Crouch, D. 2015. “Affect, Heritage, Feeling.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research, edited by Waterton, E. and Watson, S., 177–190. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137293565_11.

- De Souza E Silva, A. 2006. “From Cyber to Hybrid Mobile Technologies as Interfaces of Hybrid Spaces.” Space and Culture 9 (3): 261–278. doi:10.1177/1206331206289022.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 2013. The Museum Experience Revisited. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Frith, J. 2015. “Writing Space: Examining the Potential of Location-Based Composition.” Computers and Composition 37 (September): 44–54. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2015.06.001.

- Frith, J., and J. Kalin. 2016. “Here, I Used to Be Mobile Media and Practices of Place-Based Digital Memory.” Space and Culture 19 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1177/1206331215595730.

- Geoghegan, H. 2010. “Museum Geography: Exploring Museums, Collections and Museum Practice in the UK.” Geography Compass 4 (10): 1462–1476. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00391.x.

- Haldrup, M., and J. O. Bœrenholdt. 2015. “Heritage as Performance.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Researchedited by Waterton, E. and Watson, S., 52–68. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137293565_4.

- Harrison, R. 2015. “Beyond ‘Natural’ and ‘Cultural’ Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene.” Heritage & Society 8 (1): 24–42. doi:10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036.

- Hetherington, K. 2014. “Museums and the “Death of Experience”: Singularity, Interiority and the Outside.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (1): 72–85. doi:10.1080/13527258.2012.710851.

- Hjorth, L., and S. Pink. 2014. “New Visualities and the Digital Wayfarer: Reconceptualizing Camera Phone Photography and Locative Media.” Mobile Media & Communication 2 (1): 40–57. doi:10.1177/2050157913505257.

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. 1999. The Educational Role of the Museum. London: Psychology Press.

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. 2000. Museums and the Interpretation of Visual Culture. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jeremy, K., and J. Ross. (2016) “’Where Does This Work Belong?; New Digital Approaches to Evaluating Engagement with Art”, In. MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016, Los Angeles. http://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/where-does-this-work-belong-new-digital-approaches-to-evaluating-engagement-with-art/.

- Kennedy, H., R. L. Hill, G. Aiello, and W. Allen. 2016. “The Work That Visualisation Conventions Do.” Information, Communication & Society 19 (6): 715–735. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1153126.

- Kidd, J. 2014. Museums in the New Mediascape: Transmedia, Participation, Ethics. London: Ashgate Publishing.

- Kinross, R. 1985. “The Rhetoric of Neutrality.” Design Issues 2 (2): 18–30. doi:10.2307/1511415.

- Latour, B. 1986. “Visualization and Cognition.” Knowledge and Society 6 (1): 1–40.

- Lord, P., C. Sharp, B. Lee, L. Cooper, and H. Grayson. 2012. “Raising the Standard of Work By, with and for Children and Young People: Research and Consultation to Understand the Principles of Quality”. Berkshire: National Foundation for Educational Research. http://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/ACYP01/ACYP01.pdf.

- Lorimer, H. 2005. “Cultural Geography: The Busyness of Being `More-Than-Representational’.” Progress in Human Geography 29 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1191/0309132505ph531pr.

- Lury, C., and N. Wakeford. 2012. Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social. London: Routledge.

- Malpas, J. 2008. “New Media, Cultural Heritage and the Sense of Place: Mapping the Conceptual Ground.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 14 (3): 197–209. doi:10.1080/13527250801953652.

- Melchionne, K. 2010. “On the Old Saw ‘I Know Nothing about Art but I Know What I Like’.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68 (2): 131–141. doi:10.1111/(ISSN)1540-6245.

- National Galleries of Scotland. n.d. “Roy Lichtenstein, in the Car, 1963”. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/object/GMA2133.

- Neill, A., and A. Ridley. 2013. Arguing About Art: Contemporary Philosophical Debates. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ong, C.-E., and H. Du Cros. 2012. “Projecting Post-Colonial Conditions at Shanghai Expo 2010, China: Floppy Ears, Lofty Dreams and Macao’s Immutable Mobiles.” Urban Studies 49 (13): 2937–2953. doi:10.1177/0042098012452459.

- Parry, R. 2008. “The Future in Our Hands? Putting Potential into Practice.” In Digital Technologies and the Museum Experience: Handheld Guides and Other Media, edited by L. Tallon and K. Walker. Lanham: Altamira Press.

- Prior, N. 2011. “Speed, Rhythm, and Time-Space: Museums and Cities.” Space and Culture 14 (2): 197–213. doi:10.1177/1206331210392701.

- Roberts, L. 1992. “Affective Learning, Affective Experience: What Does It Have to Do with Museum Education.” Visitor Studies: Theory, Research, and Practice 4: 162–168.

- Ross, J., C. Sowton, J. Knox, and C. Speed. 2017. “Artcasting, Mobilities, and Inventiveness: Engaging with New Approaches to Arts Evaluation.” In Cultural Heritage Communities: Technologies and Challenges, edited by L. Ciolfi, A. Damala, E. Hornecker, M. Lechner, and L. Maye. London: Routledge.

- Sheller, M. 2011. “Mobility.” Sociopedia. Isa 12. doi:10.1177/205684601163

- Sheller, M., and J. Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environment and Planning A 38 (2): 207–226. doi:10.1068/a37268.

- Simon, N. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0. http://www.participatorymuseum.org/read/.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Stead, N. 2007. “Performing Objecthood; Museums, Architecture and the Play of Artefactuality.” Performance Research 12 (4): 37–46. doi:10.1080/13528160701822619.

- Stewart, E., and V. Kirby. 1998. “Interpretive Evaluation: Towards a Place Approach.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 4 (1): 30–44. doi:10.1080/13527259808722217.

- Tallon, L., and K. Walker, eds. 2008. Digital Technologies and the Museum Experience: Handheld Guides and Other Media. Lanham: Altamira Press.

- Tate. n.d. “Robert Mapplethorpe, ‘Lowell Smith’ 1981”. Tate. Accessed 16 November 2016. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/mapplethorpe-lowell-smith-ar00161.

- Waterton, E., and S. Watson. 2013. “Framing Theory: Towards a Critical Imagination in Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (6): 546–561. doi:10.1080/13527258.2013.779295.