ABSTRACT

Landscapes are composed of physical places, affording meaning-making and value creation from everyday heritage based on personal experiences, life histories, memories, traditions and heritage practices. Individually held values form the basis for attachment and connection between people and places. Place attachment develops into a sense of place, belonging and identity. Despite the Burra Charter and Faro Convention’s aspiration to include people in the assessment process, individual, subjective or emotional connections to place are often overlooked within heritage decision-making. When places are altered, neglected or damaged, such connections can be lost, and the quality of place diminished. Most changes to landscapes happen as part of the planning process, which is not currently able to account for individual connections but based on views expressed in the language of the Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD). This paper presents a method to meaningfully integrate insider or individual knowledge into the framework of local planning and decision-making while at the same time addressing subtleties and fluidity of such personal views. The people and place-centred method of Social Landscape Characterisation collects, analyses and visualises invisible or hidden value communities based on the same meaning (category value) or location (place value) as shared values across wider landscapes.

Introduction: everyday heritage and living landscapes

Everyday heritage consists of a material world – landscapes, buildings, places and objects – that provides the setting for activities and experiences in daily life. People perceive this outer world as an individual or communal experience. But only when this information is processed in the inner world of ideas and cultural imprints do such mundane tangible objects become imbued with meaning (Jacobs Citation2006). Meaning is formed based on beliefs, traditions, legends, myths, events and local and life histories. When places are imbued with meaning, people begin to value these places for the qualities they afford (Williams and Patterson Citation1999, 142). Some are consciously experienced and shared by a community, while others are more of an affectionate connection like a feeling difficult to grasp and even more difficult to express. For example, Historic England recognises that ‘social value of places are not always recognised by those who share them’ (English Heritage Citation2008, 32). The strong bond people have towards places can be measured through brain activities (Gatersleben et al. Citation2020).

Internationally and on different levels of heritage protection including designations, shared values as ‘social values’ or ‘communal values’ form part of official assessment strategies (English Heritage Citation2008, 32; see also Johnston Citation2017, Citation2023) – from local planning to World Heritage Sites – for everyday landscapes and the elements that constitute them. Social values are currently only defined through a group or community – as shared, negotiated and agreed upon in discursive methods – and these values are slowly being accepted and integrated into the heritage assessment process since their introduction with the Burra Charter (ICOMOS Citation2013) and the Faro Convention (Convention on the Value of Heritage for the Society (Council of Europe Citation2005)). However, individually held values are often not recognised and therefore lose out to the expert assessment which is supported by robust data and defined as the AHD (Smith Citation2006; see also Avrami and Mason Citation2019; Jones Citation2017). Social values are typically undervalued in official heritage assessments compared to other values and seen as less authentic because they are ‘less capable of constructing a logically consistent and convincing narrative’ (Wagenaar, Rodenberg, and Rutgers Citation2023, 1). It becomes even more challenging when an attempt is made to create such a consistent narrative from individual values or the personal connection of people to place and heritage. Social values across the everyday landscape remain hidden and unknown, despite having the potential of forming value patterns that are shared by non-related members of value communities, as will be demonstrated in the case study (below). Such communities are related through their connection and attachment to the same place – most likely without ever meeting or knowing each other. Identifying value patterns as a shared and consistent narrative can be achieved when the place, location or subject/value category come more sharply into focus. Ethnographic methods of enquiry have been shown to provide a deep insight into relationships to specific locations based on a synthesis of individually held values or opinions on a subject (Low Citation2002; Maguire Citation2017).

Following Piaget’s concept of individual constructivism (Piaget Citation2013) and Jacobs (Citation2006, 9) development of landscape perception, ‘mindscape’ form as ‘individual values, judgements, feelings and meanings’. ‘Powerscapes’ on the other hand are influenced by culture and rules and are socially negotiated involving accepted behaviour and codes; while ‘matterscape’ is the ‘material reality, described as a system of facts on which laws of nature apply’. According to Jacobs (Citation2006, 187) landscapes have triggers of natural qualities that allow the emotional response and creation of meaning and connection to people with a predisposition for such qualities. However, when such a valuation of place is then integrated into the current system of heritage assessment, this subjective and individual process can be limited and distorted by the need for identifying a community with shared values, limited by the discourse and biased by the dominant voices in the group or the assessment object. This raises the question: how can local authorities identify significance of everyday heritage and what matters most in people’s daily lives and environment on an individual basis? And how can this insider or individual knowledge be meaningfully integrated into the framework of local planning and decision-making?

This paper provides an overview of the current approaches to value assessment in the historic environment in an international context and presents challenges of a people-centred approach to the inclusion of such values into the planning and decision-making process. I will then give a UK-based example of new research that attempts to find ways to include people’s views more easily into the process. The developed methodology can be applied internationally and scaled up or down according to need. While Dalglish and Leslie (Citation2016, 217) advocated for a meaningful integration of individually held values into planning considerations, which was difficult to achieve with conventional techniques, Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools offer new applications and levels of capability. I present a project that has collected, analysed and visualised individually held values in a digital form using AI tools, such as Natural Language Processing and Topic Modelling, and GIS software. In the presented case study, I propose the integration of the resulting Social Landscape Characterisation maps, based on individually held values and subsequently categorised as shared value groups based on location or value category, into the framework of existing heritage and landscape management datasets.

Heritage assessment strategies and value communities

People’s connection to places is complex, difficult to articulate and the format of expressions often not appropriate for inclusion into data sets held at local authorities to facilitate change and development (Common Ground Citation1996, Citation2006; Johnston Citation2023). Historic England’s Conservation Principles (English Heritage Citation2008) identifies four value categories: historical, evidential, aesthetic and communal (see also Emerick Citation2014, Citation2016). This approach has been analysed and extended as part of this research elsewhere (Tenzer Citation2022; Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023a, Citation2023b). As a subcategory of communal value, the Conservation Principles recognise that ‘social values of places … may only be articulated when the future of a place is threatened’ (English Heritage Citation2008, 32). In such a case, the potential loss of a heritage asset can trigger the formation of an interest group. Other groups or communities are identified through a shared tradition (see Johnston Citation2023). Nonetheless, the definition and final assessment of significance of tangible or intangible heritage nearly always rests with the expert.

Defining significance of the historic environment focuses on the assessment of professionals and experts expressing values of place in a language adhering to the AHD. This approach is based on communal values as shared values of the public. For example, in Australia, Johnston notes that the AHC (Australian Heritage Council Citation2009, 6) – aligning with Historic England’s communal values (English Heritage Citation2008) – frames social value as:

‘The necessity for the social value to be a shared value […] arises solely from the way this criterion is framed in Australian heritage practice. It does not accommodate the situation where many individuals independently hold the same value’.

However, people perceive their daily environment and everyday heritage most likely as an individual within cultural and social boundaries, not as a group, continuously negotiating identity and attachment (compare Jacobs Citation2006, ‘mindscape’). Individual views on landscapes, places, buildings and objects are what constitute dynamic heritage practice in a daily context. In contrast, not all members of a community share all values at the same level. Interest groups work towards one or a set of aims. Communities are connected through, e.g. locality, profession, tradition, historical interest or local initiatives, for example, neighbourhood planning or stewardships. But communities are not homogeneous, and any approach needs to acknowledge this form of value creation. Individuals can express values that loosely create value communities based on specific landscapes, areas, goals or interests. Sometimes the reasons behind place attachment and connections are also hard to define and express by people themselves. This makes it more challenging for local authorities that want to engage people through local initiatives, such as Local Listing projects.Footnote1 These list applications demand research by the people who want to put local heritage forward which deters people from engaging. The challenge going forward is to find tools and methodologies that allow authorities to collect place attachment data on an individual level and integrate the results of the analysis into the assessment framework for valuation of the historic or everyday landscape.

Current landscape of place-based, people-centred initiatives

Recent Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) place-based projects acknowledge that the meaning of place-based and people-centred varies. Place, however, can be more tightly defined, as:

‘[…] where life courses are shaped, social networks are formed, and the sites of lived and felt experiences. Place is also a geographic location where economic resource is allocated, boundaries are mapped, and data is collected’.

Heritage plays a central role in the process of creating a sense of place and ‘is both an input and an output of the process of heritage creation’ (Graham, Ashworth, and Turnbridge Citation2000, 4). AHRC-funded place research projects in the UK show the different approaches to express the various forms of place attachment, sense of place and identity, and place making through rootedness (Madgin and Robson Citation2023). Public involvement and participation have become a focus for development over the last three decades, and the role of experts has been at the centre of discussions. English Heritage campaigns and guidance with titles such as Knowing your place (English Heritage Citation2011) and Our Places (English Heritage Citation2011) tried to actively engage people with the heritage on a local basis, but the relevant places were – in the end – still defined by experts. The public were included successfully as stewards, visitors or volunteers but not in actively defining and shaping the values of the cultural landscape. As Smith (Citation2006, 94) points out, the way in which heritage is managed has an influence on public opinion. Schofield (Citation2014) argued that while we still need experts, the role of the public needs to be reinforced. It is the local population who are the experts in their own place and know best what direction change could take in line with locally held values. Schofield’s provocative title Who needs experts? was critiqued for dismissing the important role experts still play in the process of heritage identification and management and for handing over the field of heritage to an untrained public with no real chance of changing the underpinning policies. It was polemicised that in this process, the whole sector, including academic education, would be at risk. Instead, it was suggested to study up to be more effective (Hølleland and Skrede Citation2019, 833).

However, so far, several projects have proven that the bottom-up approach is more people-centred and empowering for marginalised groups in society to make their voices heard than a top-down approach, and, while expertise will still be a regulating factor in heritage and landscape management, the role of experts has to change to remain meaningful and inclusive in a changing world (Avrami Citation2009, 179; Byrne Citation2008b, 15–16; Chitty Citation2016, 7; Jokilehto Citation2016, 31; Primdahl and Kristensen Citation2016; Smith Citation2006, 4). The role of the public is still seen as a passive participant and consumer. This is, for example, reflected in the language of heritage organisations which is dominated by terms such as ‘invited’, ‘learn’, ‘share’ (Smith Citation2006, 44). This language contradicts any intention of developing meaningful participation or co-creation. The future challenge will be to design approaches for meaningful integration of public views and social values; also, to create a methodology for a practical, repeatable, on-going evaluation of such data. In view of landscape characterisation,Footnote2 for example, there is a sense in which people’s perceptions will play an increasingly essential role in the recognition of distinctiveness and quality of places.

Examples of people-centred approaches to place evaluation and management

Internationally, projects have developed people-centred methods and approaches for the evaluation of people’s perceptions. Assessing the personal connection to places that define cultural landscapes has been identified as an essential element of heritage in view of contemporary cultural association, for example in the US (Altman and Altman Citation1992; Low Citation1987, Citation2002; Lynch Citation1960; Manzo and Perkins Citation2006) in a rural and urban context and Canada (Maguire Citation2017) associated with national parks, in Italy (Nardi Citation2014), in the UK (Jones and Leech Citation2015), in Australia (Byrne Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Brown, Raymond and Corcoran Citation2015; Modesto and Waterton Citation2020) and in Denmark (Primdahl and Kristensen Citation2016), the last with a strong focus on heritage practice and landscape perception of marginalised groups and in urban contexts. People’s individual perception plays a role in the study of place attachment and has been extensively explored in Poland (Lewicka Citation2011). The following section will detail some of these approaches.

Examples of counter mapping can be found in the US with the work of Lynch and his approach to understanding the use of place and attachment within an urban context (Lynch Citation1960). A similar approach was undertaken by Byrne, mapping the life stories and memories of First Nation People in an Australian context (Byrne Citation2008a). The approach went beyond and critiqued a one-sided western and nature-focused view on landscapes. Also, Cultural Mapping is an initiative that enables community participation and identification of social values across wider landscapes.Footnote3 Nardi (Citation2014) applied a similar people-centred approach in Italy by using 2D paper maps which were annotated with stories and memories by the local community. These projects were based on methodologies which provide a good foundation for new approaches using innovative methodologies through advanced GIS and computer capabilities and the evolving field of AI technologies (see also Jones Citation2017; Jones and Leech Citation2015).

Common Ground, an environmental and arts organisation, was formed in 1985 by Angela King, Sue Clifford and Roger Deakin out of the environmental movements of the 1970s (Common Ground Citation2019; Hayden Citation1995, 63). Their Parish Map project was different from the usual environmentally focussed projects in its focus on local heritage and artistic exploration of local distinctiveness (Perkins Citation2007, 128). What started with a few artists exploring a sense of place grew into a community-led activity across the country. Parish maps were the visual representation of the essence of a place, the artistic expression of people’s attachments and experiences in their neighbourhoods (Common Ground Citation1996; Perkins Citation2007, 130). The examples vary from woven panoramas, as produced during the parish maps project, to web-based maps since digital online mapping has become affordable and accessible for the public (Perkins Citation2007, 127). The artistic expression format made a meaningful integration into frameworks and structures of local authorities for the planning process challenging, if not impossible. The essential development to render such projects integratable was, therefore, the step towards digital technology, which is increasingly finding entry into the fields of heritage and archaeology.

Two projects carried out in Denmark encouraged communities to use landscape characterisation carried out by the communities themselves, based on participant’s perception of the environment (Primdahl and Kristensen Citation2016). This approach allowed the public to inject their views into the planning process and represent on a map the values of the community in the form of ‘landscape as a common good’ (Primdahl and Kristensen Citation2016, 229). The advantage of these case studies was the close cooperation between the authorities, specialised experts, academic researchers, other stakeholders, such as landowners, and a group of interested people from the communities. The method proved to influence the planning proposals. However, while the groups continued their work after the end of the research projects, the project was initiated, led and supported by experts and technology which is not usually readily available and accessible to communities (Primdahl and Kristensen Citation2016, 236). The approach of recreating the landscape character map to include people’s views without funding and technical/IT support proved challenging for local authorities with limited resources. This approach has the advantage that it is proactive, not reactive. However, while the mapping process in cooperation with the researchers was successful in representing the values of the communities, one of the case studies revealed that the assessment of natural and cultural characteristics in the landscape proved to be problematic for non-experts (Primdahl and Kristensen Citation2016, 236), proving the point that experts and local residents need to work together to achieve the best result for increasing the quality of places.

Other projects in the UK, such as Roots and Futures by the University of Sheffield (University of Sheffield Citation2020), Heritage Lincoln Connect (City of Lincoln Council Citation2011), Know your Place in Bristol and the English West (Bristol City Council Citation2021), attempted to capture social values on online web map platforms to evaluate and incorporate the data into the practice of local authorities or to explore how these data can contribute to a holistic view on heritage resources. A further project studying the relationship between museum collections and people during the COVID-19 crisis was launched by Liverpool Museum, providing extraordinary insights into how people’s view on the world and their stories changed during the pandemic (National Museum Liverpool Citation2021). All these projects use digital platforms for the collection and visualisation of the data, which constitutes a development towards meaningful integration opportunities in the planning and assessment structures.

Community-led characterisation by community or focus groups has the potential to empower communities and include their values meaningfully in the planning process (Dalglish Citation2018, 53–55). However, this approach proved challenging as communities do not always share a coherent identity or are motivated to act purely democratically. Rather, community groups represent the dominant voices in a community rather than the whole community or individual opinions. Furthermore, groups often consist of self-selecting active community members, while others are marginalised leading to ‘unrepresentative views’ (Dalglish Citation2018, 56–58). Parts of the community are excluded based on, for example, time restraints, ethnicity, IT illiteracy or anxiety. Despite these difficulties, toolkits have been developed to help communities identify what is important in their neighbourhood. In Scotland, for example, Talking About our Place Toolkit (NatureScot Citation2020) or the Place Standard How good is our Place? (Scottish Government Citation2023) are useful to improve participation in local characterisation and evaluation schemes. Similarly, Robson (Citation2021) developed a methodology to empower communities and qualitative researchers to engage with communities and explore shared values.

Surveys or polls conducted by local governments or organisations to collect public opinions run the risk of consciously or subconsciously influencing or manipulating public opinion. Opinion can be influenced through directed questioning, narrowing the opportunity to express opinions openly. For example, stating that heritage is important and asking the question afterwards or focusing the surveyed group on people who are already engaged with heritage, results in a highly biased survey outcome and brings circularity into the process. Examples are IPSOS Mori surveys formulating statements as questions and asking for the degree of agreement (English Heritage Citation2000, 2; Byrne, Brayshaw, and Ireland Citation2003, 64; Smith Citation2006, 94).

According to current views, public participation cannot accommodate every single, individual view of members of a community, and they are not always uncontested and democratic (Dalglish and Leslie Citation2016, 217). Perkins (Citation2007, 131) shows that even grass roots projects such as the Parish map of Mottram-in-Longdendale revealed tensions amongst communities; agendas were dominated by some groups or parts of the community, while others were excluded. Avrami (Citation2009, 182) suggests, therefore, to focus more on the ‘process’ of ‘negotiating change’ with the public in planning rather than the outcome. In this context, the following section presents a project that developed a methodology to collect and analyse individually held values in places as stories that represent personal connection or place attachment that allows meaningful integration of personal, subjective and individual values associated with places (tangible and intangible factors for connection) into the framework of planning and decision-making.

Case study: from individually held values to Social Landscape Characterisation

Developing a Social Landscape Characterisation (SLC) based on the perception, needs and visions of the local population and visitors, against the background of current practice and previous projects, using bottom-up approaches, was the main focus of a project at the University of York. The used data collection methods comprised social media data (Twitter, now X), online surveys and semi-structured interviews. The resulting datasets were analysed using Artificial Intelligence tools, correlated and visualised in GIS. The resulting digital maps provide opportunities for meaningful integration of the insights into individually held values into assessment frameworks.

While the study areas were located in the UK, the method is applicable anywhere where comparable data exist, in both rural and urban areas. Study areas for this project comprised the Peak District National Park (PDNP) and the city of Sheffield, two spatially closely connected, in fact overlapping, but very different areas in the north of England (for map see Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023b, ). While the study included the city of Sheffield for the survey approach (Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023b), the focus in this paper is the PDNP, which provided data for all three data collection stages (social media, survey and interviews). The PDNP was the first designated National Park in the UK (in 1951), with wide views, open space and natural beauty. The rich history of human occupation extends from the Palaeolithic, through Roman and medieval times into the historic landscape of post-medieval and contemporary worlds. Archaeological and historical features comprise designated monuments such as burial mounds, henges and stone circles, traces of mining and medieval industries, listed buildings, and conservation areas, as well as a large number of undesignated, locally important heritage assets. Together these historic sites form the environment in which people follow their daily routines, contributing to the distinctiveness of places through their social practices, affording these places values through connection and sense of place, belonging and identity. As elsewhere, communities and places in the PDNP are affected by local and global challenges. Increasing footfall of visitors, community coherence loss through second and holiday homes, wildfires and droughts as results of climate change are just some challenges the National Park has to tackle.

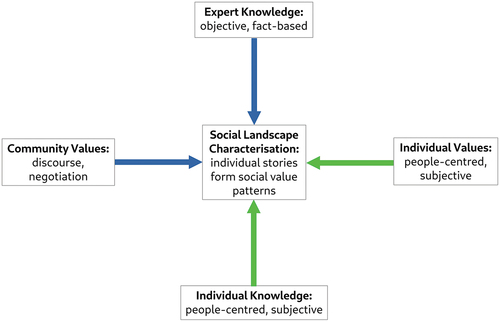

shows how the approach taken in this research can be positioned within current assessment strategies, which are (a) expert-led or people-centred (vertical scale) and/or (b) focused on predefined community groups to assess shared values or based on individual stories (horizontal scale). The proposed method is expert-led and implemented but includes people’s perceptions through their individual stories. The approach has the potential to form invisible communities and reveal patterns of social values shared by individuals. Such individual values when viewed as single occurrences are anecdotal and subjective; however, when patterns emerge across landscapes such individual values can be understood and interpreted as shared or social values focused across wider landscapes, including everyday and designated heritage.

Figure 1. Position of Social Landscape Characterisation in the approaches of current assessment strategies. The vertical axis shows the position between expert-led and implemented assessment, which is fact-based, and objective and a people-centred approach based on individual knowledge. The horizontal scale represents the spectrum of community-based values and an approach from the individual story to extract patterns and create invisible communities of shared values based on same meaning or same location.

The methodology consists of three stages: (1) data collection from three different data sources, (2) the application of Artificial Intelligence tools (Natural Language Processing (NLP), Topic Modelling (TM)), after (T. W. Jones Citation2021; T.; Jones, Doane, and Attbom Citation2021) and (3) the creation of various outputs for different requirements of potential users, such as community groups or local authorities (for detailed methodology and workflow diagram see Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023b). The project used social media data from people posting about the study areas (Twitter data, now X) (Tenzer Citation2022), online surveys focused on people living and working in the study areas (Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023b), and semi-structured in-depth interviews with people living and working in the study areas (Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023a). Social media data was based on hashtag searches for the area of the PDNP, extracting frequently mentioned locations and sentiments towards those places. The online survey asked participants for their favourite places within the study areas and their stories of personal connections to those places. The interviews were semi-structured to give participants the widest possible freedom to tell their stories. While social media data provided a broader overview of the places dominating the conversation and the emotional connections formed towards them, the survey narrowed the focus and provided insights into the personal stories of connection and perception of local people. A further focus with individual case studies through in-depth interviews gave essential snapshots of personal place attachments and the reasons for the development of a strong sense of place and belonging.

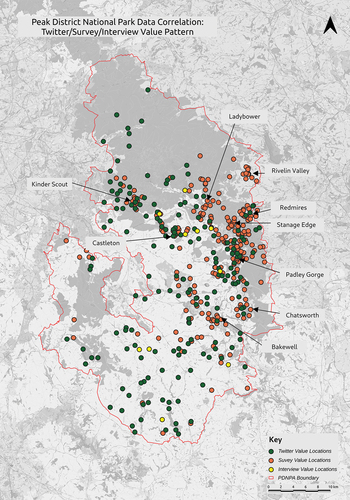

shows the correlation of the three different data sources in the PDNP study area. Survey and social media analysis provided larger datasets that represented patterns of values in varying levels of convergence. Survey data represent the valued places of locals (orange point data), while social media data (green point data) represent a wider view on valued places from visitors. Hotspots, representing a stronger connection of local people, are apparent in, e.g., the reservoirs of Ladybower and Redmires and Rivelin Valley, as ideal local recreation areas. Similarly, Stanage Edge as a natural landmark featuring remnants of the industrial past in the form of large millstones () and the market town of Bakewell are seemingly more valued by local residents of the PDNP and Sheffield than by outsiders. In contrast, the south of the PDNP, also known as White Peak, with a gently undulating landscape, deep gorges and caverns, was more often mentioned by social media users tweeting about the PDNP. Both data sources revealed high values for, e.g. Padley Gorge (), one of the UK’s rare temperate rainforests, valued for its qualities for recreation and natural beauty. A high significance for social media users and survey participants was notable at Kinder Scout, the highest point in the Peak District with wide views, moorland and waterfalls. The yellow point data on the map () represents the interview locations (for more details of the methods and results of this approach, see Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023a). This in-depth exploration of people’s deep connection and rootedness in the landscape focused on the reasons behind a strong place attachment. The participants were partly located in areas that were identified as highly valued by social media users and survey participants (northern part of the PDNP) and areas of less dense data (southern part of the PDNP). The reasons for connection were dominated by the aesthetic qualities of the landscape, the rich historical past and personal memories, and life histories in the particular places.

Figure 2. Correlation of the results from social media data (green points), surveys (orange points) and interviews (yellow points). The point data symbolises the story and connection of an individual person to a specific place in the PDNP. In this visualisation, the pattern of individual values shared across wider landscapes can provide an insight into areas of high value. However, blank areas symbolise no data not the absence of significance for the people. (map created in QGIS; data contain OS data © crown copyright and database right 2022. Map tiles by Stamen Design, under CC by 3.0. Data by OpenStreetMap, under OdbL).

Figure 3. Impression of the moorland below Stanage Edge with wide views and remnants of the millstone industry (photo by the author).

Figure 4. Padley Gorge, a rare example of a temperate rainforest in the UK, a place valued by visitors and locals for the natural qualities and as recreation space. While the place seems natural, wild, and untamed human traces can be tracked across the landscape, e.g. drystone walls and remnants of the millstone industry (photo by the author).

The results revealed two distinctive patterns of invisible or hidden value communities, based on single, individually held values (for detailed results see Tenzer Citation2022; Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023a, Citation2023b). While current evaluation processes define a community in advance of research or assessments and negotiate dominant values, this approach allowed such value communities to arise and form naturally based on two factors: first, people who connect to the same places for different reasons – location-based communities; and second, people who value wider areas for the same reasons – value-based communities.

As an example for the first category, participants in the survey favoured the ‘natural’ qualities of the landscapes in the PDNP in various spots (see categorisation of the data in Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023b, Fig. 8; also; Bell Citation2005). Reasons for this connection were often associated with the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent changes of behaviour and the need for relaxation and recreation in an increasingly busy world. Such seemingly natural and untamed, wild places are the result of human impact on the environment but treated as natural heritage, creating the dichotomy of nature/culture in the discussion of heritage and landscape management (see Byrne and Ween Citation2015; Harrison Citation2015). This dichotomy did not exist in the minds of the research participants and reasons for attachment overlapped, spanning from aesthetic values, family and local history value, the need for recreation and exercise to spaces of mental well-being and solitude or community and cultural programmes.

The study also showed that people connect and appreciate historical places that are officially designated as heritage, such as the Grade I listed stately home of Chatsworth House in a Grade I listed Park and Garden (). Other locations, e.g. the small town of Castleton, are favoured mainly by locals for associated traditions, such as the Castleton Garland and Well Dressing. gives an impression of Rivelin Valley, one of the river valleys leading from the PDNP into Sheffield and providing green space for recreation as well as a connection to the industrial history of the city. The second category or the accumulation of different values in specific places was present in the data and visualised as hotspot maps (Tenzer Citation2022) and category maps (Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023b). Important to note is that blank areas on the map represent a lack of data and not the absence of values or of their significance for people.

Figure 5. Impression of the valued landscapes in the PDNP and Sheffield: Rivelin Valley and the wheels along the watercourse. The place affords recreation and historical connection and represents the qualities of nature/culture heritage (photo by the author).

Figure 6. The stately home of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, a Grade I listed Chatsworth House set in a registered Park and Garden, are officially designated heritage assets and equally valued by local people and visitors, albeit for different reasons. While the designation is based on the historical value of the country house and the designed parkland, people also value the place for the recreational qualities and traditional events (photo by the author).

How an inclusion of social values in the planning and decision-making process might look is shown in . The proposed structure contains maps with different information from various sources, e.g. Historic Landscape Character data, results from social media research or surveys, with variation in complexity of represented data achieves with varying levels of application in the planning process and potential for engaging resources for outreach and public engagement. The results prove that the collection, analysis and meaningful integration of individually held social values can be achieved, using time-efficient methods, such as TM and online surveys, and digital visualisations in GIS that can be integrated in existing tools of local authorities.

Figure 7. Framework for inclusive heritage mapping with decreasing complexity and increasing potential for engagement and outreach from top to bottom. Information on each map varies and is gathered from different sources showing HLC data, results from social media research, survey results and other. The combination of information allows to create a comprehensive data structure of landscape information for specific areas.

Discussion: the study in context

The methodology outlined in this paper builds on the shift in society which started as the cultural turn in the 1960s and was conceptualised in charters and conventions concerning the cultural and natural heritage, such as the Faro Convention (Council of Europe Citation2005) and the Burra Charter (ICOMOS Citation2013). In response on a national level, social values were added to the traditional canon of heritage values in the official assessment strategies as shown in the example of the Australian and UK guidelines (Australian Heritage Council Citation2009; English Heritage Citation2008). However, the realisation of the aim to include people and local knowledge meaningfully into heritage practice and management has not yet been fully realised. The reasons for this are the continuing adherence of professionals and experts to the AHD (Smith Citation2006) and the challenges of capturing and including social or individually held values in the framework of assessment strategies (Dalglish and Leslie Citation2016, 217). Sustainable, inclusive and transparent planning needs to acknowledge the people-place connection and better understand the reasons behind place attachment to provide better quality places in future. This need is fully acknowledged in the AHRC Place Matters project: ‘Understanding place as somewhere with lived and felt as well as geographic and economic dimensions is crucial to the pursuit of better outcomes for people and place’ (Madgin and Robson Citation2023, 6). Internationally, several initiatives are working towards the goal of meaningful integration of people-centred perspectives into planning for better places in rural and urban landscapes (Jones Citation2017; Madgin and Robson Citation2023; Nardi Citation2014; Primdahl and Kristensen Citation2016). However, projects have a slow uptake as IT literacy and access to the online resources can be challenging for the wider public. Also, research projects often rely on licenced software and highly skilled digital researchers. Such support usually ceases after project funding ends.

This research shows that individually held values can be collected, analysed and visualised in a time efficient way. Instead of predefining groups or communities, participants were allowed to tell the stories that connect them to their favourite places in a given study area. The resulting patterns, formed based on the same values across the landscape or different values in the same place, revealed hidden value communities. This provided the opportunity to infer and categorise the reasons behind a strong place attachment from personal stories, which allowed the creation of value categories based on the language and themes dominant in the empirical data, as opposed to a predefined and expert-led top-down process. This people-centred approach will offer new ways to explore people’s views on natural and cultural landscapes in a working and living environment.

The presented case study provides an example for the innovative application of AI methods to qualitative data in a landscape management context. NLP and TM were used for the analysis of unstructured text documents following the principles of Grounded Theory (Charmaz Citation2006) to achieve a first bias-reduced insight into the latent themes within the data. This allowed themes to emerge from the empirical data which were not anticipated in the outset of the project. A subsequent manual analysis revealed shortcomings, ethical implications and advantages of the method (for details see Tenzer and Schofield Citation2023b). A refined study could include and focus on marginalised groups and explore pathways to engage people that were not reached in this study. A further project would also have the potential to use Machine Learning and Deep Learning methods to automatically categorise new data by unsupervised/self-taught learning. The field of AI deployment in heritage and landscape studies offers a wide range of opportunities in the future.

The trans- and cross-disciplinary development of digital technologies and AI have yet to find a way forward in the field of landscape and heritage management. However, data scientists, digital archaeologists and heritage professionals are starting to collaborate for a joint approach to the application of digital methods in archaeology and cultural heritage management. Such collaboration will in future open new ways and give new insights into new and existing data sets to explore and use archaeological and historical data for the creation of resilient and coherent communities and have a positive impact on place-making and care for the environment in the face of global challenges.

Conclusion

This paper presents and gives context to a novel methodology that allows capturing and visualising individually held values and analysing reasons behind strong connections to places. The results show that it is possible to integrate and categorise individually held values and visualise these as coherent patterns of shared social values across wider landscapes.

Although this case study is focused on a small area in the north of England, the methodology can be scaled and applied much more broadly. Current advances in internet connectivity, analysis tools, e.g. AI tools, and technologies for interactive collaboration and visualisation, e.g. online surveys and GIS, have the potential to realise the ambitions of the cultural turn for a meaningful discourse between planning authorities and community groups as well as individual people that benefit from positive change and preservation of living landscapes. Data sets of this Social Landscape Characterisation offer a vital background for proactive planning and decision-making within local authorities while integrating people’s individual values meaningfully into the heritage and landscape management strategies.

The study of story-based, individually held values has the potential to generate practical applications with an effective integration of people’s views into the framework of planning policies. It shows that individual opinions based on local people’s personal stories, memories and traditions can be meaningfully and efficiently integrated into the official frameworks of planning and decision-making. Reinforcing the bond between people and place through a bottom-up approach within local planning and thereby generating appreciation of the everyday places and a wish to care for this environment, might help to tackle the most pressing problems of the present but also of future generations and foster cooperation and communication between planning authorities and the people for whom inclusive and transparent planning strategies provide better places to live.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Archaeology, University of York, UK. All participants of the surveys and interviews have provided informed consent. Social media research adhered to the terms and conditions of the respective social media platforms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martina Tenzer

Martina Tenzer is a PhD researcher at the University of York (UK) focusing on methods for analysis and visualisation of public perception and place attachment in cultural landscapes for inclusive landscape and heritage management. She also works as a Heritage at Risk Project Officer for Historic England. Prior to this, she gained degrees at the University of Oxford, UK (MSc Applied Landscape Archaeology) and the University of Heidelberg, Germany (MA Archaeology and Prehistory) and worked in commercial archaeology. Her research interests include Contemporary Archaeology, Historic Landscape Characterisation, landscapes of biodiversity and climate change impact, Artificial Intelligence in heritage management, mapping and visualisation of complex, abstract concepts, and QGIS.

Notes

1. https://local-heritage-list.org.uk/south-yorkshire Sheffield local listing project

2. For example, Historic Landscape Characterisation as planning tool for the historic environment. The maps are based on the historic processes that lead to present landscapes and provide the element of time-depth to the assessment process.

References

- Australian Heritage Council. 2009. “Guidelines for the Assessment of Places for the National Heritage List.” https://www.dcceew.gov.au/parks-heritage/heritage/ahc/publications/nhl-guidelines.

- Avrami, E. 2009. “Heritage, Values and Sustainability.” In Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truths, edited by A. Richmond, A. L. Bracker, and V. A. Museum, 177–183. 1st ed. Oxford, Amsterdam: Butterworth-Heinemann, Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum London. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/york-ebooks/detail.action?docID=535314.

- Avrami, E. and R. Mason., 2019. “Mapping the Issue of Values.” In Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions, edited by S. Macdonald, 9–33. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Bell, S. 2005. “Nature for People: The Importance of Green Spaces for Communities in the East Midlands of England.” In Wild Urban Woodlands. New Perspecives for Urban Forestry, edited by I. Kowarik and K. S., 81–94. Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-26859-6_5.

- Bristol City Council. 2021. “Know Your Place - Bristol.Gov.uk.” https://www.bristol.gov.uk/planning-and-building-regulations/know-your-place.

- Brown, G., C. M. Raymond, and J. Corcoran. 2015. “Mapping and Measuring Place Attachment.” Applied Geography 57:42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.12.011.

- Byrne, D. 2008a. “Countermapping: New South Wales and Southeast Asia.” Transforming Cultures eJournal 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.5130/tfc.v3i1.687.

- Byrne, D. 2008b. “Heritage as Social Action.” In The Heritage Reader, edited by G. Fairclouch, R. Harrison, J. N. R., Jameson J and J. Schofield, 149–173. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Byrne, D., H. Brayshaw, and T. Ireland. 2003. Social Significance: A Discussion Paper. 2nd ed. Hurstville, N.S.W: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/-/media/OEH/Corporate-Site/Documents/Aboriginal-cultural-heritage/social-significance-a-discussion-paper-010001.pdf.

- Byrne, D. and G. D. Ween. 2015. “Bridging Cultural and Natural Heritge”. In Global Heritage: A Reader. 1st ed. edited by L. Meskell, 94–111. Wiley Blackwell Readers in Anthropology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Los Angeles; London: Sage Publications .

- Chitty, G., ed. 2016. “Introduction.” In Heritage, Conservation and Communities: Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building Heritage, Culture, and Identity, 1–14. London: Routledge.

- City of Lincoln Council. 2011. “Heritage Connect Lincoln.” http://www.heritageconnectlincoln.com/article/about.

- Common Ground. 1996. “Parish Maps.” Common Ground. https://www.commonground.org.uk/parish-maps/.

- Common Ground. 2006. “Local Distinctiveness.” Common Ground. https://www.commonground.org.uk/local-distinctiveness/.

- Common Ground. 2019. “History.” Common Ground. https://www.commonground.org.uk/history/.

- Council of Europe. 2005. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/199.

- Dalglish, C. 2018. Community Empowerment and Landscape. Glasgow: Inherit and Community Land Scotland.

- Dalglish, C., and A. Leslie. 2016. “A Question of What Matters: Landscape Characterisation as a Process of Situated, Problem-Orientated Public Discourse.” Landscape Research 41 (2): 212–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2015.1135319.

- Emerick, K. 2014. Conserving and Managing Ancient Monuments: Heritage, Democracy, and Inclusion. Heritage Matters. Boydell & Brewer. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/conserving-and-managing-ancient-monuments/99AEFF7CEDEA0F8CB53D131E54634F8D.

- Emerick, K. 2016. “The Language Changes but Practice Stays the Same. Does the Same Have to Be True for Community Conservation?” In Heritage, Conservation and Communities: Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building, edited by G. Chitty, Heritage, Culture, and Identity 65–77. London: Routledge.

- English Heritage. 2000. Power of Place: The Future of the Historic Environment. London: English Heritage.

- English Heritage. 2008. Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance. Swindon: English Heritage.

- English Heritage. 2011. “Our Places.” English Heritage. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/about-us/our-places/.

- English Heritage. 2011. “Knowing Your Place: Heritage and Community-Led Planning in the Countryside.” https://www.stratford.gov.uk/doc/173665/name/English%20Heritage%20Knowing%20your%20Place.pdf/.

- Gatersleben, B., K. J. Wyles, A. Myers, and B. Opitz. 2020. “Why are Places so Special? Uncovering How Our Brain Reacts to Meaningful Places.” Landscape and Urban Planning 197 (May): 103758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103758.

- Graham, B., G. J. Ashworth, and J. E. Turnbridge. 2000. A Geography of Heritage. New York: Oxford Universtiy Press.

- Harrison, R. 2015. “Beyond ‘Natural’ and ‘Cultural’ Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene.” Heritage & Society 8 (1): 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036.

- Hayden, D. 1995. The Power of Place. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/power-place.

- Hølleland, H., and J. Skrede. 2019. “What’s Wrong with Heritage Experts? An Interdisciplinary Discussion of Experts and Expertise in Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (8): 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1552613.

- ICOMOS. 2013. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance 2013. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf.

- Jacobs, M. 2006. The Production of Mindscapes: A Comprehensive Theory of Landscape Experience. Thesis, Wageningen: University of Wageningen.

- Johnston, C. 2017. “Recognising Connection: Social Significance and Heritage Practice.” Córima, Revista de Investigación en Gestión Cultural 2 2 https://www.academia.edu/36157277/Recognising_connection_social_significance_and_heritage_practice (2): https://doi.org/10.32870/cor.a2n2.6306.

- Johnston, C. 2023. “Social Value. Identifying, Documenting, and Assessing Community Connections.” In Routledge Handbook of Cultural Landscape Practice, edited by S. Brown and C. Goetcheus, 245–259. London: Routledge.

- Jokilehto, J. 2016. “Engaging Conservation: Community, Place and Capacity Building.” In Heritage, Conservation and Communities: Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building, edited by G. Chitty, Heritage, Culture, and Identity 17–33. London: Routledge.

- Jones, S. 2017. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (1): 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996.

- Jones, T. W. 2021. “Topic Modeling.” https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/textmineR/vignettes/c_topic_modeling.html.

- Jones, T., W. Doane, and M. Attbom. 2021. textmineR: Functions for Text Mining and Topic Modeling. Version 3.0.5. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=textmineR.

- Jones, S., and S. Leech. 2015. Valuing the Historic Environment: A Critical Review of Existing Approaches to Social Value. AHRC Cultural Value Report. Manchester: University of Manchester. https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/uk-ac-man-scw:281849.

- Lewicka, M. 2011. “On the Varieties of People’s Relationships with Places: Hummon’s Typology Revisited.” Environment and Behaviour 43 (5): 676–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510364917.

- Low, S. M. 1987. “A Cultural Landscapes Mandate for Action.” CRM Bulletin 10 (1): 30–33.

- Low, S. M. 2002. “Anthropological-Ethnographic Methods for the Assessment of Cultural Values in Heritage Conservation.” In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage: Research Report, edited by M. T. de la, 31–49. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute.

- Low, S. M. and I. Altman. 1992. “Place Attachment.” In Human Behavior and Environment, Vol. 12. edited by I. Altman, and S. M. Low. Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-8753-4_1.

- Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge: THe MIT Press & Harvard University Press.

- Madgin, R., and E. Robson. 2023. Developing a People-Centred, Place-Led Approach: The Value of the Arts and Humanities. University of Glasgow.

- Maguire, B. D. 2017. Modeling Place Attachment Using GIS. Vancouver: University of British Columbia. https://open.library.ubc.ca/media/download/pdf/24/1.0348807/3.

- Manzo, L., and D. Perkins. 2006. “Finding Common Ground: The Importance of Place Attachment to Community Participation and Planning.” Journal of Planning Literature 20 (May): 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412205286160.

- Modesto, G. and E. Waterton. 2020. “The Elite and the Everyday in the Australian Heritage Field.” In Fields, Capitals, Habitus: Australian Culture, Inequalities and Social Divisions 1st, edited by T. Bennett, D. Carter, M. Gayo, M. Kelly, and G. Noble.Routledge, https://www.routledge.com/Fields-Capitals-Habitus-Australian-Culture-Inequalities-and-Social-Divisions/Bennett-Carter-Gayo-Kelly-Noble/p/book/9781138392304.

- Nardi, S. D. 2014. “Senses of Place, Senses of the Past: Making Experiential Maps as Part of Community Heritage Fieldwork.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 1 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1179/2051819613Z.0000000001.

- National Museum Liverpool. 2021. “Covid-19 Display.” National Museums Liverpool. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/covid-19-display.

- NatureScot. 2020. “Talking About Our Place Toolkit.” NatureScot. https://www.nature.scot/enjoying-outdoors/communities-and-landscape/talking-about-our-place-toolkit.

- Perkins, C. 2007. “Community Mapping.” Cartographic Journal, The 44 (2): 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1179/000870407X213440.

- Piaget, J. 2013. The Construction of Reality in the Child. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315009650.

- Primdahl, J., and L. S. Kristensen. 2016. “Landscape Strategy Making and Landscape Characterisation—Experiences from Danish Experimental Planning Processes.” Landscape Research 41 (2): 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2015.1135322.

- Robson, E., 2021. “Social Value Toolkit – Guidance for Heritage Practitioners.” https://socialvalue.stir.ac.uk/.

- Schofield, J. 2014. Who Needs Experts? Counter-Mapping Cultural Heritage. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Scottish Government. 2023. “Place Standard.” https://www.placestandard.scot/.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, Routledge. https://www.dawsonera.com/guard/protected/dawson.jsp?name=https://shib.york.ac.uk/shibboleth&dest=http://www.dawsonera.com/depp/reader/protected/external/AbstractView/S9780203602263.

- Tenzer, M. 2022. “Tweets in the Peak: Twitter Analysis - the Impact of COVID-19 on Cultural Landscapes.” In Internet Archaeology, 59 July Internet Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.59.6

- Tenzer, M., and J. Schofield. 2023a. “People and Places: Towards and Understanding and Categorisation of Reasons for Place Attachment - Case Studies from the North of England.” Landscape Research Journal [Manuscript Accepted for Publication]. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2023.2289970

- Tenzer, M., and J. Schofield. 2023b. “Using Topic Modelling to Reassess Heritage Values from a People-Centred Perspective – Applications from the North of England.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 1–22. First view. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774323000203.

- University of Sheffield. 2020. “Roots and Futures.” https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/archaeology/research/roots-and-futures.

- Wagenaar, P., J. Rodenberg, and M. Rutgers. 2023. “The Crowding Out of Social Values: On the Reasons Why Social Values so Consistently Lose Out to Other Values in Heritage Management.” In International Journal of Heritage Studies, June Routledge. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs.

- Williams, D. R., and M. E. Patterson. 1999. “Environmental Psychology: Mapping Landscape Meanings for Ecosystem Management.” In Integrating Social Sciences and Ecosystem Management: Human Dimensions in Assessment, Policy and Management, edited by H. K. Cordell and J. C. Bergstrom, 141–160. Champaign, IL: Sagamore Press. https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/value/docs/environmental_psychology_mapping_landscape_meanings.pdf.