Abstract

This article examines the convergence of amateur and professional documentary practice, particularly photographic self-portraiture, as it is performed on the mountainside. It uses a tight selection of examples drawn from the community of hillwalkers known as ‘Wainwrighters’ to examine the phenomenon of ‘produsage’ (Bruns Citation2008).

While the world of digitally co-created artefacts may seem a distance away from the top of a mountain, I argue here that high peaks and mountain tops are no more immune from the influence of social media than any other space. In this context, the article seeks to answer a series of questions relating to the practice of taking ‘summit selfies’: What do the self-made digital artworks produced by walkers, and disseminated in tight-knit online communities of mountain hikers, look like? What is it about the mountains that provokes such forms of mediatized self-expression? And how do artefacts evolve and transform, to form ‘palimpsests’ as Axel Bruns terms the outputs of produsage? These questions are discussed in relation to three main examples sited in the Lake District National Park in England: Karen’s Forster’s 214 Headstands, my own celebration of ‘Completion’ on the peak of Pillar; and Charlotte Mellor’s #HoopingtheWainwrights project.

The article concludes by repositioning the selfie as a collective creative act and challenging its popular representation as an expression of youthful selfishness.

INTRODUCTION

There are few amateur pastimes without a professional counterpart, few home pursuits undertaken in one’s own time that haven’t been professionalized and capitalized. The rise of professional gaming, or Esports (Li Citation2016), is perhaps the most telling example of this – where players’ dedication to video games, originally rehearsed in darkened bedrooms and private domestic spaces, has migrated to massive gaming arenas with global exposure. Spelling, baking, even hotdog eating have seen similar developments, and as a result the phrase ‘turning professional’ might be seen to have lost some of its clout.

Hillwalking, by contrast, has retained its status as a resolutely amateur activity, for now at least. Of course there are various professional occupations aligned with hillwalking – fell running, ultra-marathons, mountain leading, guide writing, for instance – but the practice of walking up and down fells itself, solo or in a group, somehow seems to defy the forces of professionalization, not least because of its inbuilt Sisyphean absurdity. Locals with jobs to do living in mountainous areas often look upon the passing hillwalker with amusement: Why put all that effort into climbing a peak if all you’re going to do is come down it again?

Such distinctions, though credible and recognizable, are founded on a false dichotomy and, as critics such as Caroline Hamilton have pointed out, are fraught with ‘remarkable contradictions and oversights’ (Hamilton Citation2012: 179). Amateurism and professionalism are not best defined in counterpoint to one another, she maintains (179–80), as this leads to the, frankly silly, conclusion that an amateur wilfully avoids payment for their activities and a professional, by definition, doesn’t like what they do for a living – ‘amateur’: from French, from Latin: amator, lover (Collins). What is more interesting is to examine the convergence of these two statuses, a convergence undeniably accelerated by web-based technologies and the diversification of roles associated with them. Hamilton describes these in illuminating terms:

Many work roles (especially in the media industries) now deliberately avoid classification or refuse official forms of consecration or authorisation: the reality TV celebrity, the social media user, the blogger, the citizen journalist, the hacker, and the media intern are all roles performed somewhere between the lines of paid/unpaid, professional/amateur, authorised/ unofficial. (180)

These are ‘liminal’ roles, she argues, ones that promote modes of complex co-creation rather than linear forms of production.

Hamilton is echoing points made by others, including the media theorist Axel Bruns, who in 2007 coined the term ‘produsage’ to represent a (then) emerging new hybridity of producer and user. So-called produsers operate ‘in a collaborative, participatory environment’, he argues, ‘which breaks down the boundaries between producers and consumers and instead enables all participants to be users as well as producers of information and knowledge’ (Bruns Citation2007: 101). The results of this co-creation or produsage, then, challenge previous models of cultural production and indeed of artistry, disaggregating creative processes and artefacts across multiple contributors. We need, therefore, to rethink the very notion of an artefact, according to Bruns, recognizing that an object that is ‘prodused’ is ‘evolutionary, iterative, and palimpsestic’ (101). In short, it is never finished.

The world of digitally co-created social media may seem a distance away from the top of a mountain or from the mocking eyes of a Cumbrian farmer, but high peaks and mountain tops are no more immune from these developments than any other space. As outdoor educationalist Simon Beames concludes in the chapter ‘Adventure, Technology and Social Media’, ‘the transnational growth and existence of adventure practice is undoubtedly supported by those actively using new technologies that underpin social media’ (Beames et al. Citation2019: 88). Beames and his colleagues are, in truth, analysing the extreme, celebrity end of adventure practices – Big Wall climbing, for instance – whose practitioners garner hundreds of thousands of followers on media platforms, such as Instagram and Facebook. But it is equally true, I argue here, that the more modest pastime of hillwalking

is being similarly transformed by social media. What do the self-made digital artworks produced by walkers and disseminated in tight-knit online communities of mountain hikers look like? What is it about the mountains that provokes such forms of mediatized self-expression? And how do artefacts evolve and transform, to produce the palimpsests Bruns refers to in which ‘projects take the form of texts authored collaboratively … through comments and annotations “in the margins”’ (2008: 27)?

The field of social media production is unimaginably large, and the subset of produsers dedicating their activity to hillwalking is still vast. The hashtag ‘summitselfie’ on Instagram has attracted over 15,000 posts and this figure is dwarfed by those who have watched YouTube videos of more severe forms of hiking, such as the Mount Huashan Plank Walk in China (ten million views since 2014),Footnote1 or Half Dome in Yosemite National Park in the US (four and a half million views since 2015).Footnote2 To bring focus (and arguably sanity) to this enquiry I draw here on less extreme hillwalking practices to approach these questions using examples from a community of hikers practising in the Lake District National Park in England. Despite the less elevated location (below 1,000 metres rather than up to 3,000 metres) the environment nevertheless provokes some heightened expressive behaviours played out on the social media platforms Facebook and Twitter. As a walker and Facebooker myself I am part of this community and in this article I move between my own experience of ‘produsage’, to that of others in the region, charting the modes of self-presentation adopted. As a group we are united by the shared pursuit of ‘peak bagging’ or, more specifically, ‘Wainwrighting’ – that is, ticking off each of the 214 fells in Lakeland declared by artist, guide writer and notorious curmudgeon Alfred Wainwright to be worthy of a walker’s attention.

PEAK PRODUSAGE

Mountains have long been the target of careful framing. From the hand-held facilitator of the picturesque known as the Claude Glass, popular in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,Footnote3 to the witty labelling of Skye’s mountains in Alec Finlay’s a company of mountains project (2012–13), perspective has been played with by walkers in the mountains. Ever since they began to be climbed, self-immersion has always been in tension with an urge to capture what is beheld of the mountains, an urge that, for Finlay, took him on a ‘journey toward the fundamentals of viewing itself’ (Finlay Citation2013).

Those fundamentals underwent radical change with the advent of smartphone technology and the inclusion, in 2010, of the reversible camera, a device that could equally point forwards to the landscape or backwards towards the user. This ostensibly modest innovation led to a substantial change in attitudes to self- portraiture and ushered in the now much maligned practice of ‘selfie’ taking, one simply defined as ‘characterized by the desire to frame the self in a picture taken to be shared with an online audience’ (Dinhopl and Gretzel Citation2016: 127). The popular press and some academic critiques have focused on the ubiquity of the selfie as evidence of a rise in narcissism, particularly in men (Sorokowski et al. Citation2015), and there are many stories about the mishaps that befall selfie-takers trying to frame their pictures without looking around them: ‘Risky Selfies Killed 259 People in 6 Years, Study Says’ (CNET Citation2018) or ‘That Selfie May Be Epic, But Not Worth Your Life’ (WebMD Citation2019) are typical examples. Beyond psychology and media studies, selfie research has been undertaken in leisure and tourism studies, and in the subset of that discipline that might broadly be called performative, treating tourism as ‘a complex multiplicity of fluid, dynamic, and continuingly unfolding practices and performances’ (Scarles Citation2009: 484). Researchers from this field are calling for more balanced analyses of the selfie (both as an object and a practice) and for research to go beyond positioning selfie-taking as ‘a selfish act’ to seeing it as part of ‘the continued convergences of travel, digital culture, and communication technologies’ (Paris and Pietschnig Citation2015: 6).

Hillwalking offers fertile territory for this expansion of interest into digital self-portraiture and it is the summit cairn, fittingly, that sees the highest concentration of activity. Responding to a post I placed on the popular Facebook group, ‘To climb the 214 Wainwright Fells’ (on 13 September 2019), walkers admitted to an array of selfie practices from the homespun to the acrobatic – modest acts of expressivity triggered by their arrival at the mountain’s highest point.Footnote4 Dogs, mascots, puppets, hula hoops, stuffed toys, even Jelly Babies are brought into service in the ritual of place-making occasioned by reaching the cairn. Generally, the scale of these figures is pragmatically determined by the ease with which they fit into a rucksack (or can travel under their own steam) but there are well-documented instances of much larger items being dragged up mountains to be framed at the top as a selfie. Marine Matthew Disney, for example, gained international recognition for his fundraising challenge to climb the highest peaks in England, Wales and Scotland with a 26-kg rowing machine strapped to his back. Later he was pilloried for leaving the same rowing machine on top of Mont Blanc when he got into difficulties (BBC News Citation2019).

In this middle section, I want to elaborate on three examples from this vivid collection of mountain selfies, discussing them as discrete artefacts before in the final, concluding section I draw out some of their unifying characteristics and return to the question of distributed creativity and liminality suggested by the term ‘produsage’. These artefacts are i) Karen’s Forster’s striking 214 Headstands, ii) my own dewy-eyed celebration of ‘completion’ on the peak of Pillar and iii) Charlotte Mellor’s joyous #HoopingtheWainwrights project.

214 HEADSTANDS

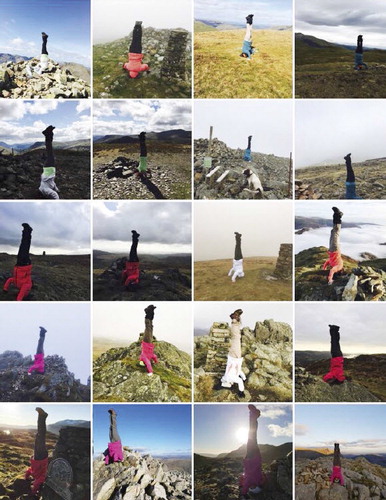

The Wainwright mountains, so called as they feature in Alfred Wainwright’s seven-volume guide to the Lake District (1952–65), are located across a diverse Cumbrian landscape that stretches from the most southerly peaks of Dow Crag and Old Man of Coniston to the northern outlier, Binsey, some 65 kilometers away. Like all aspiring Wainwrighters, Karen Forster undertook to climb each of these peaks, and to keep a record of her feat. Unlike most, that record was a headstand on the summit of every mountain, an act chosen because that was something she could do ‘easily’ (Forster Citation2019).

As a single picture the photo-documentation of this balancing act might be dismissed as something gimmicky or perverse. But as a montage (ultimately of 214 thumbnails), it is a much more thought-provoking piece of work. The stark simplicity of the act, symbolized in the neat lines of the performer’s body, contrasts with the fluctuating state of play all around her. Weather, topography, landscape, time of day, background and foreground: all are changing against the solidity of the human form. Vertical and eye- catching, Forster is a human cairn at the mercy of the elements, at times in competition with her constructed partner-in-rock, at others filling in the gap where there is no cairn. These 214 feats of balancing are a headstrong act in every sense of the word. As we view them in all their iterations it is impossible not to imagine what the changing surface of the mountain feels like to Forster. There is a palpable shock in seeing forehead meet with crag – a reminder that we have in many ways lost direct contact with the landscape by virtue of the technology we wear and our bias for intellection, as Tim Ingold has observed in relation to the boot (Ingold Citation2011: 36). Ironically, here, it is the head not the foot being forced into sensory service.

While this might seem a unique and idiosyncratic project, my post to the Wainwright walkers group flushed out a surprising collection of similar practices on the summit of the mountains: handstands, star jumps (clothed and unclothed) and balances on the columned triangulation point itself, all formed part of the ritual of marking the highest point.Footnote5 There is something about a summit that provokes expression.

PILLAR COMPLETION

Selfies did not even exist when I began my own efforts to complete the Wainwrights in 2006, a task I took on in a group of four with my wife and two sons. A dozen years later, in August 2018, we stood on our final Wainwright, at the top of a peak called Pillar, having entirely habituated the practice of self-documentation; it was as if our achievement was somehow dependent on its capture and dissemination on social media. Even if we had wanted to, we could not have produced an artwork of the simple beauty Karen Forster managed; ours was an altogether more fragmented record, begun when cameras were largely separate devices from phones and when Facebook was still a university networking tool. The artwork presented here is a set of rough and ready snaps grabbed in the window of visibility afforded to us on the summit that day, and as such is perhaps a more typical example of the selfie ‘form’.

Horizons are slanted, faces cropped out: there is little here one would describe as good composition. But composed it is, of course, even though the mix of joy and sadness captured is spontaneous and authentic. The performed behaviour may not be as obviously choreographed as Forster’s headstands but there are still the ingredients of self-aware construction and storytelling – the pouring of champagne libations on the cairn; the clunking of plastic glasses with the Cumbrian mountains behind; and the collective confessional to camera telling an anticipated audience that this is the very last time this coming together will occur.

It was this story (an ‘epic quest’ to summit all the peaks together) that formed the key part of the extended artefact, prodused by the many hundreds who ‘liked’ this image and the scores of people who commented. Notably, there are no references in those comments to the quality of the posted images, but many to the narrative behind them: ‘lovely story’, ‘a wonderful finale’, people commented. More interestingly, the post prompted personal reflections, occasionally sad ones, of walking partners past and present, and triggered in some a nostalgia for experiences on the fells that are no longer possible. One comment requested pictures of my sons from the very first Wainwright we climbed in 2006 (Pavey Ark), and in doing so forced me to confront the bookends of the ‘project’ and the gulf of time between them. Others reflected on the meaning of ‘family’, on the challenges of parenting and the vagaries of self- and group motivation.

There are layers of co-creation at work here, from the ensemble act of Wainwrighting to which we, as a family, were committed, to the multi-vocal dialogue played out in the comment threads of the post, one that for all its unremarkable domesticity nevertheless reflected some fundamentals of the human condition: mortality, family dynamics, our place in nature. These are compelling reasons to rethink the ‘selfish act’ of the selfie.

# HOOPINGTHEWAINWRIGHTS

Youth Hostel Association worker Charlotte Mellor has chosen to mark her summitting of the Wainwrights through expressive hoop dancing or ‘hooping’, a form of dance that developed out of the child’s game ‘hula hooping’, using rings of plastic originally trademarked by a US toy company in the 1950s. Spurred on by the festival and rave cultures of the 1990s, hooping has become a source of fitness, well- being and even spiritual expression (Roberts and Gray-Hildenbrand Citation2019: 37). Mellor is still finishing the 214 fells (at the time of writing), and her project, documented largely on video rather than stills, is accessible through Twitter at the hashtag HoopingtheWainwrights. There are shared characteristics with the previous examples, not least the marking of a summit with an act of heightened self-presentation. Here, though, the tone of the work is light, playful and joyfully contagious. If hooping is experiencing a renaissance and moving out of circus and into the mainstream (Hula Hooping Citation2019), then Mellor is a great advocate for its adoption into mountain culture. In her own words she is ‘escaping the boundaries’ of traditional hooping practice and ‘creating a whole new field’ with this endeavour (Mellor Citation2019).

The early videos in the series HoopingtheWainwrights indicate a distinct getting-to-know-the-task quality – an improvised tripod results in the head of the dancer being cut off; wind in the microphone dominates another. ‘I’m so bad at recording myself’, Mellor says in the post, ‘I need a camera person’. Later, she manages to recruit a series of willing volunteers, and the static perspective of previous films is replaced by much more dynamic visuals, the camera circling the dancer as she circles herself with the hoop; music and post-production titles are added too. One such example is the 30-second film ‘Ling Fell’, filmed on the small peak in the North Western Fells.

Mellor perches confidently on the triangulation pillar, ‘the only feature of note’ on the hill (Wainwright Citation2005), as far as the disparaging Wainwright was concerned. The camera arcs about her as she swings the hoop around her arms and body, sometimes using it to frame her own face to create a momentary circular vignette. Aloft the cairn with crossed legs, it is a performance of casual possession, a statement of intent, a provocative, deftly delivered gendering of the mountain.

Along with the other examples discussed in this article, there is a DIY quality to these expressions of mountain enthusiasm (even with the added special effects). Mellor does not have thousands of followers or a long stream of comments and ‘likes’ on any of the videos. The music choices are eclectic and there is no attempt to impose an organizing aesthetic on any of the digital assets. Mellor’s short videos are the very antithesis of the genre seen so often in mountain festivals: films with dramatic drone footage and uplifting strings. But with her magical manipulation of a hoop she is expressing a commonly felt sensation at the summit of a mountain: the feeling that you can shout at the wind with abandon, express delight without sanction.

CONCLUSION

What then is it about the summit cairn that provokes these modest but memorable acts of creativity? I began this discussion with the suggestion that the hybrid act of ‘produsage’ is part of a twenty-first-century convergence of amateur and professional roles, or – more fundamentally – may signal the obsolescence of the distinction itself, at least in some contexts like the media industries. To reiterate, this is because, Hamilton argues, roles in these industries are ‘liminal’ and often fall between paid and unpaid, authorized and unauthorized activity (Hamilton Citation2012: 180). Such liminality may not be applicable in occupational terms in the examples analysed here but in spatial terms it most certainly is, and not just in the manner Hamilton (and indeed Bruns) understand it. For them, spatial liminality is a function of the digital space occupied by practitioners: that is, by the ostensibly levelling environment of social media platforms, where all of us are just a post away from viral visibility and a new profession. Even for the low-visibility examples analysed here, that might indeed be true – after all who knows who might pick up the hashtag HoopingtheWainwrights in the future? But liminality is not just a digital phenomenon in these expressions of mountain creativity; it is also a given of the environment in which the acts are taking place. The cairn is the marker point between climbing up and descending, the dividing line between attempt and completion. It exudes a peculiar attraction, a magnetism, which in certain circumstances can be fatal, luring explorers rapt with ‘summit fever’ into decisions they would not otherwise make.Footnote6 Once that attraction has been gratified and the summit point reached, the examples outlined here suggest there is a surfeit of energy, which seeks – needs – to be released. For some, that release is in the form of heightened or stylized expression, either achieved through their own bodies or through an extended inventory of props, objects that have nothing in common except their unsuitability as mountain equipment.

That unlikeliness of activity and object – the uncanniness of the hula hoop or headstand – in turn serves a function once the experience has been captured and posted on social media. It provides a hook for those witnesses beyond the location and the act itself to relate to, or in Bruns’ terms co-create, the memory.

Notably in these examples, and particularly my own posting on Pillar, after the initial engagement the lure itself is forgotten in favour of the story behind the act. For it is the story, not the remarkable deed, that can be widely shared in what Scarles has called ‘theatres of memory’ inhabited by ‘coperformers’ (2009: 471). From such a perspective, the selfie is a misnomer, then; acts of self-presentation performed high up in the mountains in remote locations lead not to solipsism and selfishness but to collective meaning-making in the world below.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This article would not have been possible without the support of the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Notes

3 ‘A Claude Glass – essentially a small, treated mirror contained in a box – is a portable drawing and painting aid that was widely used in the later 18th century by amateur artists on sketching tours. The reflections in it of surrounding scenery were supposed to resemble some of the characteristics of Italian landscapes by the façmous 17th-century painter and sketcher Claude Lorrain, hence the name.’ https://bit.ly/32OaCIi

4 This is a closed group, currently with 15,000 members. It is located here: https://bit.ly/2ImcHBX

5 I deal with the performativity of rituals in mountains extensively in Chapter 2.1, in the forthcoming: Performing Mountains (Palgrave, 2020).

6 Summit fever: ‘the continued pursuit of a mountain summit despite information indicating that the pursuit is likely unsafe’ (Zajchowski et al. Citation2016: 120).

REFERENCES

- BBC News (2019) ‘Mont Blanc: Outcry as ex-Marine dumps rowing machine near peak’, https://bbc.in/3cyzU1q, accessed 31 October 2019.

- Beames, Simon, Chris Mackie and Matthew Atencio (2019) Adventure and Society, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bruns, Axel (2007) ‘ Produsage’, in Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Creativity and Cognition, pp. 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1145/1254960.1254975

- Bruns, Axel (2008) Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life and Beyond: From production to produsage. New York: Peter Lang.

- CNET (2018) ‘Risky selfies killed 259 people in 6 years, study says’, https://cnet.co/39pHhGL, accessed 19 December 2019.

- Dinhopl, Anja, and Ulrike Gretzel (2016) ‘Selfie-taking as touristic looking’, Annals of Tourism Research 57: 126–39. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.015

- Finlay, Alec (2013) A Company of Mountains, https://bit.ly/2wwWnvf, accessed 31 October 2019.

- Forster, Karen (2019) Email conversation with the author, 13 September 2019.

- Hamilton, Caroline (2012) ‘Symbolic amateurs: On the discourse of amateurism in contemporary media culture’, Cultural Studies Review 19(1): 177–92. doi: 10.5130/csr.v19i1.2679

- Hula Hooping (2019) ‘History of hula hooping’, http://www.hulahooping.com/history.html, accessed 31 October 2019.

- Ingold, Tim (2011) Being Alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Li, Roland (2016) Good Luck, Have Fun: The rise of eSports, New York: Skyhorse Publications.

- Mellor, Catherine (2019) Telephone interview with the author, 28 October 2019.

- Paris, Cody Morris, and Jakob Pietschnig (2015) ‘”But first, let me take a selfie”: Personality traits as predictors of travel selfie taking and sharing behaviors’, in Travel and Tourism Research Association, pp. 1–7.

- Roberts, Martha Smith, and Jenna Gray-Hildenbrand (2019) ‘Finding religion, spirituality, and flow in movement: An ethnography of value of the hula hooping community’, Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 22(3): 36–59. doi: 10.1525/nr.2019.22.3.36

- Scarles, Caroline (2009) ‘Becoming tourist: Renegotiating the visual in the tourist experience’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27: 465–88. doi: 10.1068/d1707

- Sorokowski, Piotr, Agnieszka Sorokowska, A. Oleszkiewicz and Tomasz Frackowiak (2015) ‘Selfie posting behaviors are associated with narcissism among men’, Personality and Individual Differences 85: 123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.004

- Wainwright, Alfred (2005) A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells: The North Western Fells, London: Frances Lincoln.

- WebMD (2019) ‘That selfie may be epic, but not worth your life’, https://wb.md/2TFUowz, accessed 31 October 2019.

- Zajchowski, Chris, Matthew Brownlee and Nate Furman (2016) ‘The dialectical utility of heuristic processing in outdoor adventure education’, Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership 8(2): 119–35. doi: 10.18666/JOREL-2016-V8-I2-7697