There was no end to the number of emails we sent each other punning ‘hell’ in the subject line. At the start, this was with levity but as the long year of 2020 continued, the exchanges became infused with a heavier feeling. Moreover, the fun of infernal punning became somewhat more bitter when lockdown began. It has been hell, and hell is filled with all kinds of purgatories of delay, waiting and uncertainty, and, of course, loss. It is a testament to the authors involved in writing and producing these contributions then that there is anything to show for it at all: the call went out in September 2019 and the abstracts were accepted in February 2020. So, we are here now, having endured strange times.

The idea for this issue originated in another world, in a Time Before COVID, when an entire cohort of students could assemble, with all their lecturers, and receive a live illustrated presentation, with face-to-face discussion. In 2019 D’Arcy was the convenor of a major undergraduate module, Perspectives on Performance, (at USW, Cardiff), and he had invited Gough to deliver a guest lecture. ‘The idea of “ghosts and the otherworldly (underworld) in both Noh and Kabuki” sounds like a perfect fit and will enrich their experience’, D’Arcy responded in an email to a proposal advanced by Gough. The lecture introduced attentive undergraduates to a broad range of traditional Japanese theatre forms, including Gagaku and Bunraku, but mainly focused on how ghosts and spirits from the underworld interrupted life and interacted with human mortals in ancient, codified theatre worlds. In addition, it speculated upon how the phantasmagorical intermingled with the already fantastical representations of human and animal existence in Noh and Kabuki.

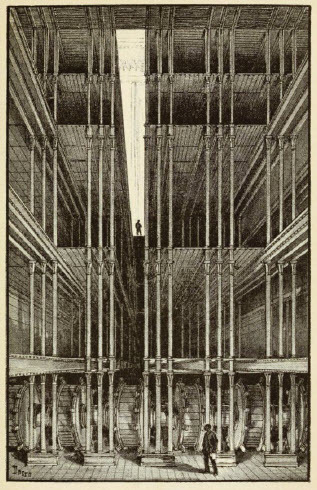

An extraordinary video sequence followed Ichikawa Ennosuke III descend through a trap in the hanamichiFootnote1 into the labyrinthine underworld of the Kabuki-za, undergo a transformation through make-up and a costume change, rapidly executed by four assistants, and then ascend on a supponFootnote2 back onto the main stage. The film allowed a glimpse into the cavernous understage of the Kabuki-za and its elaborate contraptions and stage mechanics that contribute to the creation of Naruka—Hell under-stage. Gough also described how he had once seen Ennosuke ‘ride the sky’, achieving the very opposite of the underworld journey the students had just witnessed. Ennosuke, playing the leading figure in one of Kabuki’s most popular plays, Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees, reveals himself as a magical fox. He is rapidly readjusted by assistants, in full view of the spectators, and then instead of vigorously gambolling down the hanamichi, levitates, lifts off and flies along its trajectory forever inclining to the ceiling of the theatre while striding and stomping his feet—the ‘flower path’ turned runway, became flightpath (this was a signature technique of Ennosuke, known as chunori—‘riding the sky’).Footnote3 This led to an animated discussion about stage techniques and worlds under the stage, in addition to spirits and ghosts haunting the fabulous figures above the boards.

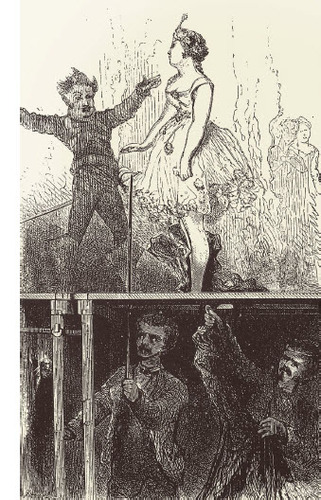

An instant costume change. The outer layer of a tear-away costume is pulled rapidly through a tiny trap door in the stage floor by stage-hands below. (M.J. Moynet. 1874: 192)

Following the lecture, D’Arcy and Gough continued to discuss the underworld of the stage. D’Arcy shared his knowledge initially forged through being a professional production manager and then extended through graduate research into the histories of stage machinery and technical invention within scenography and scenic design. Gough was introduced to the work of J. Moynet, especially the engravings of under- stage machinery, trapdoors and mechanical devices published in the book L’Envers du Theatre: Machines et decorations. An idea emerged for an issue of Performance Research specifically focused on the ‘Hell’ of theatres, on the actual physical underworld of the stage and its apparatus and machinery, ancient and modern. The Call for Papers announced that the issue would be ‘about the dark places under the stage, where things await their entrance’, and it pointed to the rich history of the under- stage world, its machinery and dark spectral potential. But it also expressed concern for the loss and disregard of the under-stage Hell, as theatres become gutted and refitted and the underworld is forgotten. The call asked: ‘So where has Hell (and all its devils and magic) gone? In a contemporary theatre of presence and immediacy, what now underlies the stage? How does what is not seen affect what is?’ The answers came in unforeseen ways. Such is the generative power of an open call. Dark places were certainly advanced but perhaps through a far wider optic than the editors had originally envisaged. Thematically this issue is diverse and different from what we thought the call On Hell would inspire: rather than one hell we received a brace of different approaches, each nuanced with a separate vision of hell in individual circumstances.

An organizing principle of the stage is that for a long time it has spatially corresponded to our cultural and spiritual concepts of the world. David Wiles in his A Short History of Western Performance Space established that the Greek and Roman stages may have been concerned with the horizontal action of human existence, but those theatres also ‘used the vertical axis to articulate relations of human and divine’, while later theatre ‘focused its attention on … movement down to Hell, back up to earth and finally to heaven’ (Wiles Citation2003: 40). Pamela Howard reinforces this, scenographically establishing that there has long been an association with the ‘vertical height from above’ the stage used ‘to indicate divine space’ and, in contrast, ‘the depth below the stage floor as the demonic space’ (Howard Citation2009: 4). The other corresponding concept that the stage has in common with the world is that just as in life, heaven and hell are invisible to those of us crawling on the surface of the world. So too are the spaces long occupied architecturally by the technologies of representation that bring the world of the stage to life also invisible.

A problem, though, now is that theatres are built without any understage; studio spaces with flat floors and no stage technology hidden in spaces beneath our feet. The aim of the Call for Papers for this issue was to ask what has replaced that space, where the technologies have gone and what this has done to the sense of the symbolic space in the theatre, particularly concerning the vertical axis. There has been a century-long divergence between the space of performance and the technologies that make it happen. The secularization brought about by a late nineteenth–century interest in realism has meant that a divine vertical axis has had less relevance in the theatre. The technologies associated with that axis have become diversified and less visible to an audience and to the performers and creators stood on the stage surface.

In collating this issue on theatre technology, we are confronted by the idea that the under- stage space of theatre being symbolically connected with an idea of ‘hell’ is a call to insiders that does not carry over to the uninitiated. If you’ve never worked on a stage with a subterranean space connected to it, there is no reason why you should even be aware of the historical axis associated with such spaces, and so, if you have never had to make an entrance from underneath a stage, or if you have never seen one, why would you create a show that included it? Going through that stage floor may just be going downstairs or going underground, and there is a significant difference between sub-stage and sub-terra, and the semiotic associations are marked. In such a contemporary world where the definition of hell is not collectively defined as beneath the stage, looking for hell in another place becomes individualistic: hell can be found in many places, each with its own hellish flavour and no longer collectively agreed to exist beneath a stage. In this issue, there are hells evoked by architecture and by technologies and there are articles that consider the ritualistic aspects of performance from across the world and their role in our salvation or, of course, our damnation.

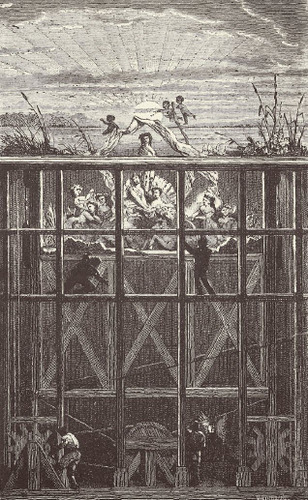

The operation of a bridge-trap raising a chorus of performers dressed as fairies and nymphs. (M.J. Moynet. 1874: 197)

Despite its contemporary rarity, Hell as a theatrical metaphor is a powerful one that, it seems, remains hidden but ever-present in theatre and performance. This is the key notion in Geraint D’Arcy’s study of different types of theatrical hell, identified as a persistent symbolic space situated directly below the stage space in various theatres across time and cultures. Hell in this circumstance is collectively agreed by an audience to exist in the same place: hidden beneath the performance space. For the participants in the site-specific performance workshops Ron Jenkins describes, hell is a resonant metaphor that surrounds them constantly. Jenkins’ work uses Dante’s journey through the Inferno to enable imprisoned people to engage with their own life stories through site-specific performance in three notorious prisons: the Sing Sing Correctional Institution, New York, the Kerobokan jail in Bali and the Sollicciano prison in Dante’s home town of Florence. In contrast to the hell of actual incarceration, Jan-Tage Kühling looks at Philippe Quesne’s scenographically innovative and disturbing Night of the Moles, as an ecological hell, inverting the metaphor of looking downwards in an analysis of a performance where the anxieties of existence in an ecologically unstable world create an environmental hell for the giant Talpidae.

Natalie Katsou assists in making sense of the variant metaphorical approaches to hell and hellishness by offering the idea of heterotopia as a way of understanding the different aspects of hell historically, philosophically and in performance. She looks at Romeo Castellucci’s (Socìetas Rafaello Sanzio) iconoclastic production of Inferno inspired by Dante, which featured Castellucci himself embarking on a journey in the Cour d’honneur du Palais des papes in Avignon, France (2008). Katsou gives an explanation for these shared versions of hell that also allows for more individualistic interpretations through an iconoclastic performance experience that presents an abstracted spectacle of Hell. This is scenographically quite a contrast to the more literal interpretations found in Hell House. Madelon Hoedt examines the scenography of this horror experience, an evangelistic Halloween performance event available in kit form to offer salvation to congregations across the US as they face the perils of contemporary sin in a peculiar blend of horror performance, realism and reality. Similar notions of reality and authenticity meet as Sara Fontana engages with a subterranean adaptation of Inferno, this time staged in the cave system that inspired its creation: the Castellana Caves in Bari, Italy. Fontana explores the further context of Dante Alighieri’s epic poem and its performance history as it is transposed into a specific spatial location against the grain of classical performance paradigms.

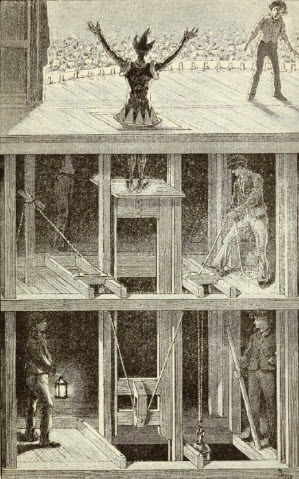

A Star Trap in operation, named after the flaps of wood which masked the opening of the trap from the view of the audience. (G Moynet 1892. 107)

This troubling of classical paradigms is continued with a technological exploration by Hakyung Sim of a Korean retelling of the Greek myth of Tiresias in A Theater for an Individual (2020). Here the subjectivity of the audience and performer is called into question through the use of robotics and Virtual Reality to think through ideas of embodiment and individual agency. Such themes are never too far from concepts of hell and no collection of articles on theatrical Hell would be complete without Jean-Paul Sartre’s Huis Clos. Rina Arya looks at Sartre’s existential vision of hell through its production history and through the solitary, banal lens of social media in the age of COVID-19. The scale of these technologies at once global and existentially isolating contrasts in interesting ways with Jasper Delbecke’s interrogation of the scenographies of DECORATELIER (an ongoing collaborative project based in a disused factory in Brussels, Belgium), which operate in both theatrical and upon architectural and civic scales. Following the arguments that have surfaced elsewhere in the issue, these articles answer some of the questions of where the technologies have gone and explore how they have manifested themselves when freed from specific theatrical spaces. Similarly, Mary L. Coyne also explores what vast spaces repurposed from old industry can create scenographically. Coyne reads a masochistic hell into the pier- like structures of Sex at Tate Modern. While Sex provides an example of how old architectures can be re-explored, we have artist pages from Peader Kirk and Tom Cassani, who re-explore bygone performance paradigms. Kirk and Cassani share their experience of staging I Promise You That Tonight, a performance that involves crawling through and lying on broken glass in the tradition of nineteenth-century stage magic reconceptualized through contemporary performance art.

Ania Malinowska’s survey of automata and robots as performance objects and as performers thinks through ideas of possession, demons or ghosts through technology in performance. This technocultural history does much to connect the historical sense of the demonic with the contemporary ideas of the cyborg and technological embodiment in performance. These are themes that Miles O’Neil and later Alvin Eng Hui Lim also evoke. First, O’Neil explores how theatrically innovative sound design and soundscapes conjure demons from the imagination using different techno-affective technologies in Picnic at Hanging Rock (2016) and Wake in Fright (2019). The demons created by sound in the imagination of these productions are firmly connected to historical performance techniques and used to interesting effect through the acoustic world of this contemporary Australian Gothic theatre. From techno- affective demons evoked in the mind to techno- provocative manifestations that appear online, Alvin Eng Hui Lim’s article investigates how the practice of spirit possession in Singapore and Malaysia has also had to cope with social distancing and lockdown restrictions. It is not just teaching that has had to move online during the COVID-19 pandemic and Lim explores the troubles and possibilities temples have faced in ritual performance through encountering underworld gods via Facebook live stream.

The ability to encounter the otherworldly or the supernatural through performance technology has long been a thrill of the theatre and a particular interest in Victorian London. Gavin Whitehead engages with such a manifestation through an examination of the material and economic context that produced the Corsican Trap, a complicated nineteenth- century performance device that once produced the most famous stage ghost in the Western world. This issue ends with Richard Gough’s visually rich exploration of Cardiff Theatre Laboratory as it performed in the slate mines of Blaenau Ffestiniog. His reverie on Hell delves into schoolboy memories and early travels to the Vucciria and the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Sicily and more recent theatre experiences of heaven and hell in Vilnius, Lithuania. This concluding exploration of Welsh Theatre in Europe is part memoir, part reminiscence, an examination of apocalyptic art and hellish performance, made and seen, above and below the stage.

This issue aims to say: we are losing a facet of the stage—a bit that is forgotten—but we are losing it because we don’t see it. We once named it, but if we forget its name, does it cease to function? How attached is it to the fabric of the stage or the aesthetic of the performance? Is it only a historical blip? A funny quirk of certain theatres, unnecessary and extravagant to think of. Even those theatres that we regard as not being reliant on any of that sort of technology, most famously and erroneously that of Brecht, still need the technology that the space provides. In 2020 (during the first lockdown implemented across Europe due to COVID), the Berliner Ensemble released (among other productions) its archive footage of Mother Courage and Her Children, a revived version of Brecht’s and Erich Engel’s 1949 production filmed in the 1960s at the Munich Kammerspeile. The first 15 minutes of the production are of the (iconic) cart being pulled along on a revolving stage by Helene Weigel, who also directed the restaging. Weigel wheels the cart at quite a pace but an enormous stage revolve allows her to remain in place while travelling: a technical construction only made possible by hidden machinery in the under- stage space of the Kammerspiele as it did in the Deutsches Theatre in 1949. It is fanciful to reject a space as unneeded simply because it does not fit with our idea of the ideals of a technology- free space. What do we do when that is gone? Where does it exist in a studio theatre or in an art gallery? Is it present in every performance?

In such a contemporary world where the definition of hell is not collectively defined as beneath the stage, looking for hell in another place becomes individualistic: hell can be found in many places, each with its own hellish flavour and no longer collectively agreed to exist beneath a stage. In this issue, there are hells evoked by architecture and by technologies and there are articles that consider the ritualistic aspects of performance from across the world and their role in our salvation or, of course, our damnation. We present here multitudes of performative Hells, each with its own inflection, history and context. Set free, the devil is in the details of all performance, whether intentional or not. That intent also extends to performativity itself and affects art that becomes embroiled in performativity such as Jake and Dinos Chapman’s installation, Hell.Footnote4 This was a monumental installation consisting of nine vitrines. They each contained horrendous exhibitions: thousands of mutilated miniature Nazi soldiers carrying out degrading acts of torture amidst skeletons and carcasses hanging from trees. The vitrines were arranged in the shape of a swastika. Hell took the Chapman Brothers two years of tedious and repetitive sculpting and engineering to make and was bought by Charles Saatchi for £500,000 (Meek Citation2004). It was the centrepiece of the Royal Academy (London) millennium exhibition: Apocalypse subtitled Beauty and Horror in Contemporary Art (23 September–15 December 2000). As Jake Chapman explained:

We bought 60,000 toy soldiers, chopped them up, remodelled and recast them. Toy soldiers were the most inappropriate form we could think of, because they exist within the realm of play. Also, they rob death of its magnitude. (Chapman Citation2015)

On 24 May 2004, the art storage firm Momart’s warehouse on an industrial estate in Leyton, East London, caught fire. The warehouse contained over 100 artworks from Saatchi’s collection, and many well-known pieces of the Britart movement were destroyed.Footnote5 The Chapman Brothers’ Hell burned to ash and cinders. Twelve fire engines and around eighty firefighters were called to the warehouse and worked through the night to control the blaze. The disaster was filmed and televised as a cinematic catastrophe. Alongside Tracey Emin’s Tent, the nine vitrines and 60,000 toy soldiers of Hell melted and congealed. Hell was on fire from night until dawn; the BBC reported that a London Fire Brigade spokesman said: ‘This was a very intense fire, black smoke and a red glow could be seen from miles away.’ (Bevan Citation2004) Some years later, Jake Chapman was to say:

We just laughed: two years to make, two minutes to burn. A smart-assed journo phoned up and said: ‘Is it true that Hell is on fire?’ It was fantastic—like a work of art still in the process of being made, even as it burnt. (Chapman Citation2015)

In 2008 the Chapman Brothers recreated Hell as an installation, again with nine vitrines containing thousands of mutilated Nazi soldiers and skeletons. It is titled: Fucking Hell.

Notes

1 The long runway (like a catwalk) that connects the stage right of the wide Kabuki stage to the rear of the theatre at the same level as spectators’ heads, enabling spectacular entries and exits along its length and through trapdoors to the ‘Hell’ beneath. It is known as the ‘flower path’ or ‘flower passage’.

2 The trapdoor and lift that takes the Kabuki actor up from the understage allowing the actor’s head to appear first and then slowly the rest of their body, like a turtle emerg- ing from its shell. Suppon as in ‘snapping turtle’.

3 A video detailing the mid-air performance, or chunori, can be found at: https://bit.ly/3CGRUmP

4 Information and a gallery of images about Hell and Fucking Hell can be found on Jake and Dinos Chapman’s website: https://jakeanddinoschapman.com/

5 Also known as Young British Artists or YBAs, Britart was a loose collection of artists who mainly emerged from Goldsmiths and the Royal College of Art, London, in the late 1980s and dominated the visual art scene in the UK throughout the 1990s. They initially gained attention by organizing their own artist-led exhibitions and a ‘sensational’ quality to their work. They became supported and collected by Charles Saatchi. Most notable, in a gathering of now well-known artists, are Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Gillian Wearing, Mat Collishaw and Sam Taylor-Wood.

REFERENCES

- Bevan, Gary (2004) qtd in ‘Fire devastates Saatchi artworks’ on BBC website, 26 May 2004, https://bbc.in/3zGwOTn, accessed 23 September 2021.

- Chapman, Jake (2015) ‘Jake and Dinos Chapman: How We Made Hell’, interviewed by Kate Abbott in The Guardian, 16 June 2015, https://bit.ly/3lJJ14W, accessed 9 June 2021.

- Howard, Pamela (2009) What Is Scenography? 2nd edn, Routledge: London.

- Meek, James (2004) ‘Out of the flames comes a bigger, better version of Hell’, The Guardian, 23 September 2004, https://bit.ly/2XTscg2, accessed 23 September 2021.

- Moynet, J. (1972 [1874]) L’Envers du Théatre, New York: Benjamin Blom.

- Wiles, David (2003) A Short History of Western Performance Space, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.