The onlookers go rigid when the train goes past.

Franz Kafka’s first diary entry, 1910

Marx says that revolutions are the locomotive of world history. But perhaps it is quite different. Perhaps revolutions are the passengers of this train—the human race – reaching out for the emergency brake.

Walter Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’, 1940

In the beginning of 2017 theatre director Ruth Kanner and I met with Michal Linial, a worldrenowned biochemist, who was the Academic Director of the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies (IIAS) at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.Footnote1 We wanted to discuss the possibility of establishing a research laboratory for a period of three to four months during the 2019–20 cycle at the IIAS with her. This laboratory would include scholars of literature, theatre and performance in combination with critical theory/ philosophy as well as the six actors of the Ruth Kanner Theatre Group (RKTG), an independent, experimental theatre, established in 1998, which had developed and perfected their activist brand of storytelling theatre.Footnote2

The aim of such a short-term research laboratory, we explained, would be to create opportunities for encounters between theoretical/scholarly and artistic/tacit forms of knowledge that as a rule do not take place beyond occasional meetings during the preparations for a specific production or in brief exchanges after a performance. Instead, we wanted to create an environment—a space—to explore the existing and possible bridges between theory and practice, while at the same time safeguarding their respective, individual independence. We wanted to ‘stop and think’, as Hannah Arendt had suggested in her posthumously published book The Life of the Mind (1978), taking time to reflect on the topic of interruptions, striving to avoid deep-rooted hierarchies where the academic discourse stands for theory/reflection while the practices of theatre are perceived as doing. We wanted to halt our regular working routines and set aside a short and intensive period of research for a few months to explore and think about interruptions.

Our proposal, initially called ‘Interrupting Kafka: Research laboratory for scholarship and artistic creativity’ (and I will clarify below why we chose this specific perspective) was submitted in December 2017 and it was accepted by the IIAS in May 2018. This gave us over a year to plan the work of the laboratory in detail before the threemonth residency at the IIAS, which took place from the middle of October 2019 through January 2020. During this year of planning the historian Yitzhak Hen became the Academic Director of the IIAS, and together with the administrative team of the institute he enabled us to realize the logistically complex research programme for the short and intensive research period at our disposal.Footnote3 We are very grateful for the support of IIAS throughout the project and in the creation of this issue. See page 171 for more details.

The workshop/seminar, held in Jerusalem during the first days of January 2020—after the laboratory had been active for about two monthsFootnote4—was simply called ‘Interruptions’. Among the invited guests who would assist us in reflecting on performative interruptions and the laboratory format of our research was Richard Gough, delivering the keynote that now opens this issue, with ‘Holding Breath’. He surprised us when he in his capacity as the General Editor of Performance Research suggested that we make an issue of the journal, based on the research laboratory. Its title, ‘On Interruptions’ is in accordance with the long-standing convention for each issue of the journal to be ‘on’ something.

With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020, a month after the end of our research laboratory, our perspectives radically changed. Instead of reflecting ON interruptions we were suddenly IN an interruption without knowing what its implications were and still are. Vivian Liska’s and Paul North’s readings of Kafka’s story ‘Up in the Gallery’, first presented at the workshop/seminar, are now also published here. Liska explores the inherent tensions between the motivations of the spectator for interrupting the circus performance while North draws attention to the interruptive/ludic potentials of pronouns like ‘on’, that we simply take for granted. This issue of Performance Research will reflect ON interruptions, IN a still ongoing interruption which is, in many ways, becoming the routine.

When preparing the Call for Papers for this issue, which was distributed in June 2020, ‘we’, the editors—Jan Kühne, who was a participant in the research laboratory, and myself—felt that it was self-evident that we would make an open call, inviting artists and scholars who had not participated in the project itself to join the initial research laboratory participants. We had already practised this open-door policy during the months the laboratory itself was active, inviting guests, both artists and scholars who did not participate in all its activities, but had similar interests and were willing to share their knowledge. The workshop/seminar in January 2020 also practised this policy.

In retrospect, the chronology of this process has been uncanny, and there is no doubt that the future will present additional challenges that we will not be able to cope with unless we study previous interruptions in depth. Even if a sine qua non of interruptions is being unexpected and sudden, like the COVID-19 pandemic; there are perhaps symptoms that we can learn something about through the histories of interruptions.

After Michal Linial’s encouraging response to our initial ideas, Ruth and I began preparing the proposal for the research laboratory. It was clear to us from the outset that we want to explore different forms of interruptions; disruptions, interferences, breaks, lapses, aporias, failures, catastrophes, transitions, montage techniques, turning points and moments of crisis (a partial list); as well as what in Hebrew is called shibushim (םישוביש), mishaps or disturbances, when something just goes wrong, usually for no apparent reason, challenging our expectations, forcing (or enabling) us to rethink (or ‘re-route’). Sadly, life in Israel presents daily opportunities to think about failure: the failure to realize an ancient dream, which was probably even impossible to begin with. But what are the cognitive and emotional challenges of such a daily existence, in an ongoing state of interruption, we repeatedly ask. Several of the contributions published here—not only those about Israel—address this issue.

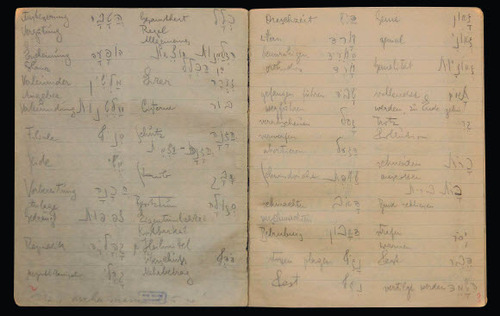

We also wanted a thematic focus that would be relevant for the IIAS, located on the Givat Ram Campus of the Hebrew University, in the vicinity of the Israel National Library, where a large collection of Franz Kafka’s manuscripts and drawings are kept.Footnote5 Of special interest among these documents is one of the notebooks that Kafka used for his Hebrew studies during the last years of his life, after he had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. It consists of a list of words in Hebrew and German in Kafka’s handwriting, which, since Hebrew is written from right to left and German from left to right, face each other in neatly organized columns on the pages of the notebook, leaving ample space for thought-inbetween the two languages. Seen from the perspective of today’s Jerusalem, this ‘inbetween’ reflects a broad range of historical and existential conditions.

Kafka’s notebook had already served as the point of departure for a performance of the RKTG, The Hebrew Notebook—and Other Stories by Franz Kafka, which was commissioned by the National Library in 2013 for its 120th anniversary.Footnote6 Since we were—and are actually still—approaching the centenary of Kafka’s death, in 2024, we wanted the laboratory to continue the study of this notebook as well as of additional Kafka stories from those that had already been included in this performance, under the heading of ‘other stories’. The performed version of Kafka’s ‘Imperial Message’ that was presented at the symposium/workshop is the subject of the conversation between Ruth Kanner and the actors published here. This story had also provided the basis for several improvisational sessions of the laboratory in the rehearsal studio of the RKTG, where we met twice every week. It is situated in the abandoned Community Centre of a small village called K’far Azar, which is today a pristine enclave where time has stopped (i.e. been interrupted), surrounded by the aggressively approaching high-rise apartment buildings of urban Tel Aviv.

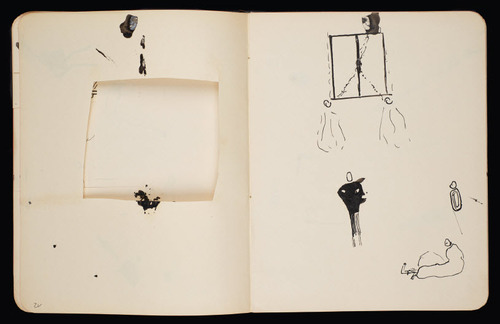

As it turned out, just before the opening of the research project itself, in October 2019, additional Kafka manuscripts and drawings (including the image on the cover of this issue , drawings on this page and the poster on page 39) were deposited in the archives of the National Library; and though most of their contents were known, these had never been viewed publicly before. In 2016 an Israeli court had ordered that these documents, brought to Mandatory Palestine by Max Brod in 1939, following the Nazi occupation of Prague, should be deposited in the library, having earlier lacked what the court considered to be a legal owner.Footnote7

Besides presenting these multilayered interruptive contexts—Kafka and his study of Hebrew at a time when his life was interrupted by illness during the First World War, being diagnosed with tuberculosis, and the vicissitudes of his archive, which had been rescued just before the Second World War—our second challenge was to characterize the notion of the interruption as a specific feature of artistic representation in literature/theatre/performance. This raises aesthetic/philosophical issues while at the same time being more specific and more readily discernible than notions like ‘tragedy’/‘tragic’ or the ‘sublime’. An interruption can be pointed at and defined ostensibly by saying, ‘This is an interruption!’ And an interruption can of course be tragic, though it can also serve as a comic relief. This makes interruptions complicated and interesting. Just think of the dynamics of playing peekaboo with a child.

Today, two years into the Age of COVID-19 (irrevocably leaving BC—Before COVID—behind us) while at the same time also experiencing the gradually approaching catastrophe of climate change (which is still primarily a crisis, approaching its fated/fatal turning point), we all know that interruptions must be approached very directly. But we do not know when, what we still term ‘an ongoing crisis’, becomes an irreversible, interruptive catastrophe. In all their forms interruptions affect our lives head-on.

The notion of interruption also has a complex history within aesthetics and performative representation, which has not yet been fully written. We began by outlining how with German Romanticism the traditional caesura, the break or pause in a verse, where one phrase ends and the subsequent phrase begins, became the point of departure for a more comprehensive theoretical approach to literature and theatre. Inspired by the enigmatic remarks of the poet and translator Friedrich Hölderlin about how this interruptive device gives form to, or structures, literary representation, Walter Benjamin developed a theatrical, performative idiom of interruptions and gestures, primarily based on the practices of Brecht’s epic theatre and the writings of Kafka, supplemented by Benjamin’s own reading of Goethe’s Elective Affinities. According to Benjamin the interruption (Unterbrechung) in Brecht’s epic theatre ‘consists in producing not empathy (Einfühlung) but astonishment (Staunen)’, and the ‘task of the epic theatre, according to Brecht, is less the development of the action than the representation (Darstellung) of situations’ (Benjamin Citation2003: 304). Through its inherent defamiliarization or estrangement (Verfremdung) an interruption of the continuous flow of harmony and wholeness also holds potentials for protest, resistance and change.Footnote8 These ideas had been further developed by poets (like Paul Celan) and philosophers (like Jacques Derrida), after the Second World War.

Both Ruth and I had already approached these topics in different ways. In 2009, we had organized a session at the Performance Studies international (PSi) conference in Zagreb together with our department colleague Daphna Ben-Shaul (who has also contributed to this issue) exploring the notion of ‘Misperformance’, mainly in the sense of disturbance and disruption, or just by making a mistake. The session we curated consisted of short performance excerpts from the repertoire of the RKTG together with critical responses to their work by researchers we had invited as well as the audience. A collage of texts reflecting (on) this session and the work of the RKTG was published the following year in Performance Research (Ben-Shaul et al. Citation2010).

Not long after the Zagreb conference, the RKTG premiered a production of Brecht’s two Learning Plays, The Yes Sayer and The No Sayer. And in 2013 they performed the The Hebrew Notebook— and Other Stories by Franz Kafka, emphasizing Benjamin’s understanding of Kafka as a writer for the stage. In his essay published for the tenth anniversary of Kafka’s death, Benjamin writes that

Kafka’s entire work constitutes a code of gestures (einen Kodex von Gesten darstellt) which surely had no definite symbolic meaning for the author from the outset; rather, the author tried to derive such a meaning from them in ever-changing contexts and experimental groupings. The theater is the logical place for such groupings. (Benjamin Citation2001: 801)

Benjamin reads Kafka through Brechtian binoculars, applying the critical apparatus that he had already developed for his interpretation of Brecht’s epic theatre to unlock the hidden secrets of Kafka’s writings. And judging by Brecht’s strong reactions to Benjamin’s essay, which he read when Benjamin visited his exilic home in Denmark in 1934, Brecht, who was also an avid, admiring reader of Kafka, was quite upset by Benjamin’s appropriation of his own innovations in the early epic plays and in particular in the Learning Plays, the Lehrstücke.

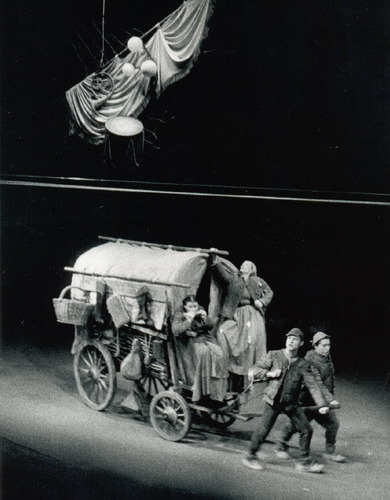

In parallel, my book Philosophers and Thespians: Thinking performance (Rokem Citation2010) had explored this triangulation of Kafka/Brecht/ Benjamin, examining Benjamin’s notion of the standstill in the context of Kafka’s short story ‘The Next Village’ about the rider who according to Kafka, regardless of the accidents that can happen on this journey, will due to the shortness of life itself never reach the next village. I had also analysed Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children, which is also about a journey that can never be completed, with Kafka’s story as well as Benjamin’s interpretation of this story in mind as a journey backwards in time. In Brecht’s own iconic 1949 production of his play in Berlin, in the opening scene the carriage on which Mother Courage and her mute daughter are sitting is drawn by her two sons. The carriage is moving in one direction, while the stage is revolving in the opposite one—thus standing still in one place, while the wheels are turning—with an emblem of a war-angel (not an Angelus Novus) hovering over them. This is not the angel of history (as in Benjamin’s well-known meditation on the painting by Paul Klee), but a cosmic standstill, interrupting history. Here, as in many other instances, for example in Fatzer, Brecht’s understanding of the interruption is even more radical and final than Benjamin’s image of/as a ‘standstill’.

The third and most important issue we had to address in the research proposal for IIAS was choosing the prospective participants of the group. This is not about documents in archives or the history of aesthetic practices, but concerns colleagues with teaching schedules and families, who would commit themselves either for the full three-month residency (as core-members) or as guests for shorter periods, or only for the final workshop/seminar. Looking back at this intricate process I believe we were very fortunate, being able to create a research community including both scholars and artists with similar interests but with widely different backgrounds and approaches in ways that made each one of us feel that we really profited in some way from the work and ideas of the others.Footnote9

It is impossible in a brief introduction to give a full overview of the process leading up to as well as the contents of this expanded issue of Performance Research, which besides those who participated in the research laboratory now also includes a selection of contributions from the many researchers and artists who responded to the Call for Papers. There are writers and artists who have contributed to this issue (some co-authored) and of these more than half have in some way been directly connected with the research laboratory:

The ‘core-members’, all of whom attended the laboratory for the whole period (or most of it), were besides Ruth Kanner and myself (in alphabetical order): Siwar Awwad, Ronen Babluki, Shirley Gal, Jan Kühne, Vivian Liska, Adi Meirovitch, Paul North, Arnon Rosenthal, Ruth Schor. Adi Chawin served as the research assistant of the group.

The guest scholars, participating in the group work from one to four weeks, were Esa Kirkkopelto, David Levin, Nikolaus Müller-Schöll, Diego Rotman and Galili Shahar.Footnote10

And the authors who only participated in the final workshop/seminar that are included in this issue are Daphna Ben-Shaul and Richard Gough.

Opening Scene of Berlin production of Mother Courage and Her Children (1949) © by Ruth Berlau/ Hoffmann (BBA Teaterdoku 655/445).

The articles by Vivian Liska, Paul North, Galili Shahar, David Levin, Nikolaus Müller-Schöll as well as the discussion of Ruth Kanner and Adi Chawin with the actors focus on different constellations related to the initial triangulation of Kafka/Benjamin/Brecht. The essays by Jan Kühne and Arnon Rosenthal are indirectly related to this triangulation and Ruth Schor’s contribution explores the Freudian slip. Among the articles originating from the Call for Papers, those by Michal Kobialka, Julia Schade and the essay by Valentín Benavides García and Carlos Gutiérrez Cajaraville engage directly with Walter Benjamin, for their discussions of a broad range of issues. Esa Kirkkopelto discusses Hölderlin, who was seminal for Benjamin’s notion of the caesura.

The contributions resulting from the Call for Papers broaden the scope of the initial project—first through the artists’ pages by Tracy Breathnach Evans, Ivana Momčilović and Ashwarya Samkaria as well as Kristina Kocyba’s interview with Falk Richter. These open each of the subsections with aspects of creative work, ranging from protest to expressing the need for care in the pandemic era and the interruption of ongoing projects. We have also included five shorter articles under the rubric of ‘Provocations’. They are meant as position statements about a specific issue, drawing attention to an interruption without presenting a fully worked out argument, in the essays by Cosimo Chiarelli, Avital Barak, Lee Campbell, Julia Schade and Naphtaly Shem-Tov.

There are also articles focusing on the artistic medium of expression; on painting (Michal Kobialka) and opera (David Levin) as well as more recent technological media, like photography (Cosimo Chiarelli and Jan Kühne) and radio (Minou Arjomand). There are also articles on the interruptive effects of the human voice (Saba Zavarei and Andrea Soto Calderón/Antonio Gómez Villar). We have also included three contributions from Israeli scholars who were not involved in the work of the research laboratory itself: by Avital Barak (on the demonstrations against Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu), Naphtaly Shem-Tov (on performative representations of women) and Dorit Yerushalmi (on the censorship of a performance by a Palestinian author). These essays reinforce the local perspectives of the project and can be read with Daphna Ben-Shaul’s exploration of the signature on the document declaring Israel’s independence. They should be read with the political changes in Israel during the time in mind, with four elections, finally leading to a left/ centre/right-wing so-called ‘change’ government.

All together there are almost thirty contributions presenting and analysing interruptions in this issue of Performance Research. They can obviously not be read in one breath—or while ‘Holding Breath’, as Richard Gough suggests. They have been selected and arranged to create a multifaceted discursive space, hopefully unfolding some of the complexities of this topic, and to stimulate further explorations and discussions. The scope of the topic is immense, ranging from the question of if/how the pandemic interruption will end and to what extent (and how) it is related to the consequences of the current anthropogenic climate change, which will lead to a much more radical interruption against which there will be no vaccine. And at the same time there are more private issues, like personal health. One month before the opening of the research laboratory at the IIAS was going to begin its work—in September 2019—I was diagnosed with cancer and received various forms of treatment until April 2020, a few months after the end of the research project. I have not needed any additional treatments since then. Considering this range of global and private issues, I do not believe it is possible to provide any comprehensive definition of the notion of ‘interruption’ beyond the specific instances that are pointed out and examined here: this is an interruption; this is another one; and here is one more.

They come in clusters, creating new contexts, making demands, causing problems that have to be solved, even complications that have no solution at all. But are they related in any way to each other? The article by Esa Kirkkopelto points at the difficulties of delineating the interruption caused by the death of Pan, the symbol of an all-inclusive reality, the ‘pan-’. The basic issue that has crystallized for me while working on this project is how to synchronize inner states of emotion with our perceptions of an outer reality; how or when sorrow or joy bring out the tears in us, or how we find ways to restrain and harness the inner human rage that leads to protest (for change) but also to violence. These tensions are perhaps crucial for what it means to be human: being able not only to experience interruptions, but to explore ways to communicate their emotional impact as well

One possible route to address this issue that I have only begun to understand during the final stages of the process described here is to approach an interruption as the result of an emotional negotiation or confrontation with a supposedly objective state of affairs. Like in quantum theory, the emotional reaction is both the outcome and the constituting agent of this reality—a reality that in turn triggers a new emotional response. From the article on The Odyssey (by Valentín Benavides García and Carlos Gutiérrez Cajaraville) I began to understand that the interruption of storytelling is triggered by the tears of Odysseus caused by his memories of the war that Demodocus is singing about. This interruption is part of the chain reaction of interruptions from which the Homeric epic is constructed, beginning already in the first line of The Iliad by invoking the goddess to sing about another emotion, the wrath (or rage) of Achilles. In the end of the Homeric epic, with Odysseus reuniting with Penelope and killing the suitors, tears and rage become unified. I leave further consideration of this, final interruption in the Homeric epic for another opportunity.

I hope that those who have the patience to explore this territory in depth will have a rewarding experience, reaching Diego Rotman’s presentation of an actor whose death begins on stage with a stroke and Mischa Twitchin’s meditation on Artaud’s empty page—the final article of this issue—as the ‘rest’ has become silence, ending with a whimper. Just before announcing his final silence, Hamlet asks Horatio to ‘Absent thee from felicity awhile, / And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain / To tell my story’ (Shakespeare Citation1989: 240). When Horatio begins to carry out this wish, inhaling to prevent the tears from coming, he is immediately interrupted by Fortinbras, who will soon begin a new war. And Samuel Beckett’s Endgame ends in a moment of ‘crying’, both referring to the shedding of tears and screaming in pain or anger, as Hamm—that which has remained of Hamlet— says, to Clove: ‘You prayed—/ you CRIED for night, it comes—/ It FALLS: now cry in darkness. / You cried for night; it falls: now cry in darkness. / Nicely put that’ (Beckett Citation1990: 133).

Yes, isn’t it?

Notes

1 See https://iias.huji.ac.il/ (accessed 27 October 2021).

2 See https://bit.ly/3dXIc54 (accessed 23 October 2021).

3 As a rule, we spent two days every week in a seminar room at the IIAS in Jerusalem, beginning the week with a day of readings and discussions we termed ‘provocations’, with one or several members of the group presenting a text or an object. The two following days every week were spent in the studio/rehearsal space of the RKTG (see below) and on the final day of our weekly group-meetings we returned to the seminar space at IIAS in Jerusalem, often with invited guests.

4 This is the same amount of ‘time’ (or even less) that Hamlet says in his first soliloquy (Act I, Scene 2), passed between the death of his father and the marriage of his mother with Hamlet’s uncle Claudius. A little later in the same scene, Hamlet says to Horatio that the funeral meats were served cold for the wedding. I’m mentioning this piece of trivia in order to draw attention to the range of perceptions of time that interruptions give rise to, with COVID-time beginning less than a month after the end of the project.

5 This is the third-largest manuscript collection of Kafka materials, all of which have been digitized and can be read or viewed online at https://bit.ly/3E2bsC4 (accessed 24 October 24).

6 For a detailed analysis of this performance see my articles Rokem (Citation2017), which was later expanded in Rokem (Citation2018).

7 This complex ‘affair’ has been described in Balint (Citation2018).

8 In this context Benjamin presents what he considers to be the most basic example of such an interruption: the sudden entrance of a stranger into a room where a scene of violence is taking place. For a detailed analysis of this situation in Benjamin’s writings see my article Rokem (Citation2019).

9 The IIAS website of the project only gives a partial picture of this complexity. See https://bit.ly/3dVgyFV (accessed 25 October 2021).

10 Ilit Farber, who led a one-day workshop on Benjamin’s plays for children; the participants of a two-day seminar/ workshop with young scholars from Yale and the universities of Tel Aviv and Haifa; and a group of young artists who had studied at the Bezalel Academy of Arts in Jerusalem are not represented here.

REFERENCES

- Arendt, Hannah (1978) The Life of the Mind, San Diego, Harcourt.

- Balint, Benjamin (2018) Kafka’s Last Trial: The case of a literary legacy, New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Beckett, Samuel (1990) Endgame, The Complete Dramatic Works, London: Faber and Faber.

- Benjamin, Walter (2001) ‘Franz Kafka: On the tenth anniversary of his death’, in Selected Writings, Volume 2, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, pp. 794–818.

- Benjamin, Walter (2003) ‘What Is Epic Theater? II’, in Selected Writings, Volume 4, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, pp. 302–9.

- Ben-Shaul, Daphna, Ruth Kanner, Janelle Reinelt and Freddie Rokem (2010) ‘Capturing Moments of Misperformance “Local Tales”’, Performance Research 15(2): 66–73, DOI: 10.1080/13528165.2010.490433 and https://bit.ly/3q0mxyO, accessed 12 December 2921.

- Rokem, Freddie (2010) Philosophers and Thespians: Thinking performance, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Rokem, Freddie (2017) ‘The Hebrew Notebook—and other stories by Franz Kafka. A work of “Speech Theatre” by the Ruth Kanner Theatre Group’, Kafka und Theater, Thewis, GTW, https://bit.ly/3F1DZcl, accessed 25 October 2021.

- Rokem, Freddie (2018) ‘Before the Hebrew Notebook: Kafka’s words and gestures in translation’, in Amir Eshel and Rachel Seelig (eds) The German–Hebrew Dialogue: Studies of encounter and exchange, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 177–96.

- Rokem, Freddie (2019) ‘”Suddenly a Stranger Appears”: Walter Benjamin’s readings of Bertolt Brecht’s Epic Theatre’, Nordic Theatre Studies 31(1): 8–21, DOI: https://bit.ly/3shEfAJ, accessed 9 November 021. doi: 10.7146/nts.v31i1.112998

- Shakespeare, William (1989) Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.