Abstract

What is failure? Defining failure broadly, Colin Feltham explains it as ‘some sort of breakdown, some malfunctioning or underperformance’. As many would suspect, espionage is rife with it. In espionage, it is often difficult to identify failure due to the secretive nature of the profession. Moreover, what is one’s failure is almost always another’s success, and vice versa.

Espionage is inherently a theatrical and performative practice. Yet lacking from scholarly discussion on this subject is the role that failure plays within espionage work. Failure often acts as a point of generation for new undertakings, or, as noted above, indicates the success of the opposing side. In intelligence work, it is part of the dialectic that feeds the self-perpetuating nature of espionage. We also see this sort of success-failure dialectic in certain forms of theatre and performance.

This article engages the case study of the infamous performer, and supposed double agent, Mata Hari, whose ultimate execution by the French during the First World War signifies total failure when viewed from multiple perspectives. By analysing the life, trial, and execution of Mata Hari through the lenses of failure and success as they relate to theatre and performance, we are able to expose and explore the dialectic at the core of espionage. To ground this analysis the essay first engages with the theatricality found in Mata Hari’s work as a spy and in her execution, a weaving together of archival documentation and biographies, and ideas from Conquergoode, Althusser, and Harbinger. Following this, the essay turns to the work of Sarah Jane Bailes and Elinor Fuchs, relating the death of Mata Hari, who stands in for all clandestine agents, to their speculations on performance theatre and the death of character.

By investigating success and failure in espionage as it parallels forms of theatre and performance, this essay looks to expose the dialectic at the heart of espionage, expand the terms in which we discuss failure in theatre and performance, and challenge the conceptualization of utopias within the discourse of live art.

THE STATE OF FAILURE

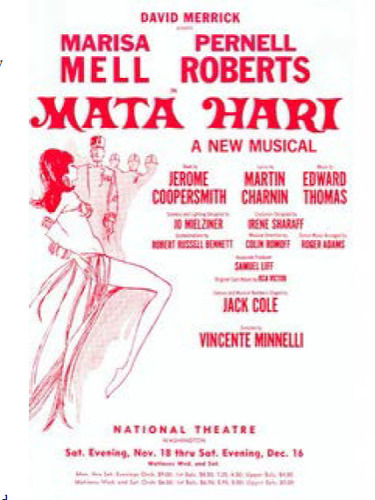

It may shock historians to know that following her execution by a firing squad—indeed, directly after a ‘doctor had pronounced her lifeless’— Mata Hari ‘raised her hand to her forehead’ (Henry Citation1967: A1). Well, perhaps not Mata Hari herself but the actress Marisa Mell who was cast as the infamous spy in the ill-fated 1960s musical Mata Hari. Mell’s raised hand was just one of the many bizarre mistakes and failures that, according to theatre critic Bill Henry, plagued the preview of the show that he attended. Failures that were so numerous that Henry asserted that ‘the whole thing began to look like something planned by Mack Sennett’ of Keystone Cops fame (1967: A1). The failure was so anticipated that when it ran that night in Washington, D.C. producer David Merrick warned the audience beforehand that the show was ‘just a rehearsal’—and it was, but not in the sense that Merrick anticipated (ibid.). This was never going to be a dry run for an ultimately successful show on Broadway. It was a rehearsal for the future failures of the show that in the end could not escape the so-called ‘Keystone Cops’ aesthetic, as it was described by Henry in his deliciously descriptive critique. What transpired over the next year was one of the biggest flops in the history of Broadway musicals. Closed early due to disastrous reviews and results in Washington during the pre-Broadway tour, the show was revamped and given the new title of Ballad for a Firing Squad. Yet, as is noted by critics such as Henry and contemporary Sam Zolotow, even the revamped songs and title could not save Mata Hari from fated failure.

It seems that failure often requires a description to contextualize that which has failed. More general definitions locate failure as a category of performance. In Failure (The Art of Living), Colin Feltham, for example, writes, ‘[Failure] refers to some sort of breakdown, some malfunctioning or underperformance’ (2014: 17). And this description certainly accounts for what happened with Mata Hari. The scenery falling, the clothes coming undone, the ‘dead’ character coming back to life: these events were not meant to happen in the tightly controlled environment of the musical. Yet Henry’s description, as an articulation of the points raised by Feltham reveals an intriguing aspect about failure: it requires context. It could be argued that the failure of Mata Hari was not the poor performers, set or costumes, but the lack of control and discipline on the part of management or directing. It could also be suggested that there was a failure to properly set expectations for what was about to be watched at the National Theatre in Washington that evening. In another reality—where Mata Hari was meant to be a comedy—these events of failure might have been intended. In such an instance it could be argued that these failures were in fact successes in their attempt to illustrate failure along the lines of Mack Sennett’s Keystone Cops slapstick aesthetic. Failure is at times hard to identify and even harder to define. And the world of theatre and performance is no stranger to this issue.

In theatre we speak about the failure of a show, an installation or a piece of work. We make work about failure, and about the failure of making work about failure. Evocative of Marvin Carlson’s assertion of theatre productions being ghosted by the past, failure haunts theatre and performance both as lived reality and as subject matter (2002: 3). And Mata Hari was no different. For what was that musical if not a failed theatrical production haunted by the case of failed espionage that was the real-life Mata Hari? Even more strange is that the failure haunting a production or lived reality seems to be able to transcend the performance event to affect people. It has been suggested that the demise of the career of Austrian actress Marisa Mell can, in part, be traced to the very noted and infamous failure of the musical Mata Hari. Cruelly coincidental is the fact that, like Mata Hari, Mell’s career began to seriously decline when she was no longer seen as the beautiful young woman that she used to be. Her last productions strayed into the realm of softcore pornography much in the way that Mata Hari turned to prostitution and love affairs to maintain her success, while her career as a dancer and performer collapsed and failed.

Yet failure not only haunts an undertaking but also governs it. How an individual rates or categorizes failure is equally based on their ability to identify and eschew the phenomenon. And this is as much about reality as it is about perception. Consider this next narrative: On 25 July 1917, a woman arrived in Vincennes, France, on what was then the outskirts of Paris. She was dressed in stockings and a blouse, which accented a dark outfit lined with fur, ‘on her head a felt hat and her shoes were ankle boots’ (Le Petite Parisien 1917). As she walked to the parade ground, thirteen men stood at a distance watching. Offered a blindfold, she declined; as she did when it was suggested that she be tied to the stake now between her and the wall behind, or when she was offered a last confession by a priest. The sentence of death was read out and upon the final word the sergeant in command called his troops to attention and raise their guns. He brought his sword up and, after a moment’s pause, drew the sword down shouting ‘tirez’.

Unlike Mell’s performance, Mata Hari did not lift her hand and rest it against her forehead. The sets did not come undone, dresses did not fall apart, scenery did not lift into the air while the other half remained on the ground and no one was laughing. This was no Keystone Cops aesthetic. As the British reporter Henry Wales wrote,

She did not die as actors and moving picture stars would have us believe that people die when they are shot. She did not throw up her hands nor did she plunge straight forward or straight back. Instead she seemed to collapse. Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. (Wales Citation1917)

What transpired was a scene of both success and failure. Success in execution, but failure in living. From Wales’s description Mata Hari continued to watch her executioners as she slowly fell backwards, her legs twisted beneath her.

She lay prone, motionless, with her face turned towards the sky. A non-commissioned officer, who accompanied a lieutenant, drew his revolver from the big, black holster strapped about his waist. Bending over, he placed the muzzle of the revolver almost—but not quite—against the left temple of the spy. He pulled the trigger, and the bullet tore into the brain of the woman. (Wales Citation1917)

Unlike the dramatic and inaccurate performance by Marisa Mell, these were the final moments of the real-life Mata Hari. Yet, it is here in such a moment of finality that the analysis of failure must begin. Indeed, as it will become clear, in espionage final moments are often the moments of departure and (re)generation.

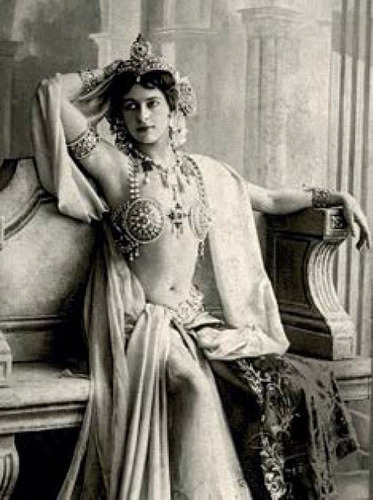

THE MATA HARI CASE: A FAILURE

A complicated history, the story of Mata Hari is one the great stories of espionage. Born in the Dutch city of Leeuwarden in 1876 Mata Hari is perhaps one of the most infamous female spies in the twentieth century. This cannot be overstated. Indeed, as Rosie White explains, ‘the infamous spy executed by the French during the First World War, haunts all subsequent accounts of women and espionage’ (2010: 72). But it is not merely that to consider women and espionage is to be obliged to understand the story of Mata Hari. This Dutch spy also presents a unique opportunity to examine the relation of espionage to theatre and performance because Hari was a performer before and while she was a spy. The fact that she was also, at times, a prostitute and mistress of high-powered men cannot be ignored if only because this aspect of her life plays into widely circulated—and indeed, problematic— cultural assumptions that society makes about the kind of women who work in the theatre and in espionage. Those cultural assumptions imply that female actors and spies are cut from the same cloth and at some level, the cultural assumption is that this cloth is woven from the fabric of moral failure. As tragic as the story of Mata Hari is, there is thus something particularly special about having a case study that features an individual who participates in the oldest and second-oldest professions simultaneously, especially since acting is sometimes offered as an alternative to the notion that espionage is the world’s second oldest profession.

Women have a long and relatively welldocumented role in espionage history. From antiquity to modern day, across culture, and in both governmental and industrial instances, women feature well. We see this in the narrative of Delilah, arguably the mythological precursor to Mata Hari; ‘Delilah shines as leading lady; shamelessly seductive, she is the quintessential femme fatale’ (Blyth Citation2017: 1). The femme fatale, while more famous for the portrayals in literature, film, theatre and art more broadly, exists beyond the artistic representation and is found throughout narratives of real life as a cultural construct. As Hanson and O’Rawe write, ‘[t]he femme fatale is thus read simultaneously as both entrenched cultural stereotype and yet never quite fully known: she is always beyond definition’ (2010: 2). And entrenched they are. So much so that the case of Hari cannot be analysed without this consideration. The idea of the femme fatale is historically rife throughout espionage history and beyond

the idea of the femme fatale is ‘as old as Eve’, or indeed as old as Lilith, Adam’s first wife, turned demon and succubus, the femme fatale, at least in Western literature and art, ‘is only formulated as a clear and recognizable “type” in the late nineteenth century’ (Hanson and O’Rawe Citation2010: 3)

To put it simply, the context that surrounds the Mata Hari-femme fatale story is governed by centuries-old misogynistic framing, which is its own kind of moral failure. But so too is it part of the context that imbues the notion of failure and success by those who engage with Mata Hari. The challenge is to not only understand the failure of her endeavours in espionage, but to also consider the failures in the context of the gendered construction of womanhood that governs the notion of femme fatale. These constructions of womanhood always bring a new aspect to espionage, much like in any other male-dominated and controlled endeavour.

The same is true of Mata Hari’s intermittent profession as a prostitute. It governed perception of her in the time she was alive, during her trial and execution, and has continued to do so since her death. Her sex and gender and her liberal notions of sexual interaction contextualized her perception by others, particularly those in government agencies. Her failure to act chastely in the eyes of others affected her throughout her life as a mother, lover, performer and public figure. More pressingly, this supposed failure influenced her trial and led in part to her conviction. In France during the early 1900s the common perception was that loose women were more likely to partake in illegal work. In her monograph, Femme Fatale: Love, lies, and the unknown life of Mata Hari, Pat Shipman provides a quote sourced from Mata Hari’s interrogator that sums up this belief among French society perfectly:

Her long stories left us skeptical. This woman set herself up as a sort of Messalina [the sexually voracious wife of Claudius I], dragging a throng of adorers behind her chariot, on the triumphant road of the theatrical success […] it was certain that she was no virgin in espionage matters. (Shipman Citation2007: 336–37)

However, Mata Hari’s supposed deviant behaviour and moral failings can also be read as personal successes. Indeed, it was her utilization of such subversive and ‘immoral’ behaviour that allowed her to succeed in a world where men were typically the ones who established moralities, ran intelligences agencies, served as military officers and held the positions of judge, jury and executioner. The trouble, as Mary Craig notes in her book Tangled Web: Mata Hari dancer, courtesan, spy, was that Mata Hari was particularly fond of men with power.

She actively sought out her lovers. She had several, sometimes seeing more than one on the same day. She was particularly fond of military men; a dangerous preference in wartime, compounded by the fact that she collected lovers from several nationalities. And, probably most damning of all, Mata Hari appeared to like sex. (Craig Citation2017: Chapter 10)

Such active pursuit served her well in establishing a life that was financially stable from shortly after her second arrival in Paris to the weeks before she was arrested. She rebelled against social convention, her success in surviving an unfair world, but her failing and downfall as well. It was the perception and context of deviance and womanhood that, in so many ways, exacerbated the speed at which Mata Hari was tried, and influenced the judgement rendered: execution. It is her execution that helps tease out how failure exists in espionage, particularly when viewed through a theatre and performance lens.

Executions themselves are imbued with performativity and theatricality. They are ‘awesome rituals of human sacrifice through which the state dramatizes its absolute power and monopoly on violence’, as Dwight Conquergood explains (2002: 342). This is just as true for the United States in the present day as it was for France in the early twentieth century. An execution is a demonstration of state power through the refined and trained movements of the military personnel firing their weapons, just as it is for the offers of a last confession. The citation that Conquergood makes at the beginning of his article is of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The birth of a prison. In this publication, Foucault ties the ritual of state execution to the domination of the human body by the state. The question that arises is: to what end? This question is in many ways challenging to answer, but if we consider this from the perspective of Louis Althusser the domination of the human body by the state is ultimately a redistribution and reaffirmation of power for the state to continue its domination—the cyclical dialectic of power and tactics of retaining power.

This retaining and reaffirmation of power is enabled through various aspects of the ritual of execution. This would include the judicial pronouncement of the death sentence that was read immediately before Mata Hari was shot; the location of the execution at the barracks of Caserne de Vincennes, which limited public access and helped maintain the opaque lens through which Mata Hari was viewed; or the use of eleven shots from twelve soldiers, a theatrical technique that is reminiscent of bad sleight of hand, absolving them of any guilt for participating and taking someone’s life, also often called the conscience round. The shooting is particularly rife with theatrical or performative tactics that enable state domination. Consider the actions that the officer and Lieutenant take after Mata Hari is fusilladed. He walks up to the lifeless body and shoots her again at close range in the head. The coup de grâce, or blow of mercy, as it is often referred to, is a particularly gruesome performative act that blurs the line between humane action and the desecration of a body. This action also serves to perform finality and to communicate simultaneously a domination of state over body, native over foreigner, man over woman, normalcy over deviance, and, as the French would have people believe, ally over enemy. Yet just as the execution is a ritual event of state power, particularly when viewed from the perspective of the state itself, so too is there theatricality and performativity within the execution from the vantage point of the executed.

In the case of Mata Hari, those who witnessed the execution were captivated by the manner in which she approached the execution grounds and held herself through the whole ordeal. Her choice to proceed without blindfold turns the power of spectatorship, which is a part of the state’s domineering, on its head. The executors become the watched performers through an act of obstinacy and self-determination. Her failure to submit is a final instance of subversion that reads to everyone watching, as evidenced by the quote from Wales. It is Mata Hari’s understanding that the blindfold is part of the costume of dominance—a tactic that enables the French military and political machinery to advance. The same determination can be used to describe her refusal of last confession. The rejection of the mainstream religious last rites offered by the dominant religion in a country whose identity has been so closely linked to such a religion, is yet another act of defiance rupturing a part of the execution ritual employed to dominate her as an extension of the populace.

In some sense, each of these instances are forms of failure. And while it could be argued that the execution of Mata Hari is a success from the standpoint of the French, the lack of ability to control the execution in totality also signifies a failure on their end. Simultaneously, this is where Mata Hari succeeds in her final moments. Consider these examples again as I draw out how one such instance constitutes both failure and success. In the first example I addressed the theatricality that is viewed in the execution. When the execution is considered as performative ritual the success or transformative result ultimately lies in the destruction of an individual. Yet, when Mata Hari intervenes, or miss-executes the role of the prisoner, she disrupts the ritual aspect of the execution. Yes, Mata Hari still dies, but the ritual power that rests in the execution has been chipped away at. She has called into question, or at least provided an alternate interpretation of, or transformative result for, the ritual for those watching. This rests on her failure to submit that in turn is a success of autonomy. The success found in her turning down the use of a blindfold is a capitalization of spectatorship while also a failure on the part of the state and its agents to exercise total control.

What should be apparent is that failure is not a finite singularity within a given instance. To put this more succinctly, I turn back to Colin Feltham who explains that beyond the lack of performance or underperformance, failure also ‘logically implies antecedent non-failure: all was apparently running smoothly or looking perfect, as expected, before this negative event. It is as if we hold a belief, perhaps a fantasy, that things should always function without fail’ (2014: 17). But this is not always true, as Feltham explains. And the analysis of Mata Hari’s execution seems to suggest that Feltham is correct. Not everything should or can always function perfectly. By the admission of many artists in history, the processes of creation, composition and execution (the doing kind, not the terminal kind) are not flawless. They are messy, organic and ever-changing. To echo Feltham further, failure exists on a spectrum of unsuccessful attempts and executions, and manifests in all the earlier identified categories that I listed in the previous paragraph. Part of the consideration of failure is contextually based.

Much like any analytical consideration, an understanding of failure is dependent on the vantage point from which an analysis is undertaken or perspective through which it is conducted. Consider again the context of Mata Hari. In some instances, we might consider the execution to be her failure as a spy. She was caught and thus executed. We can also consider this to be a success on the part of the French government, the military and the intelligence services. Yet it could also be that Mata Hari fulfilled her objectives and was only caught afterwards, meaning that in some capacity she was successful, while the French military and its allies failed. Further still, there is a strong historical case to be made that Mata Hari was in fact never a spy. This would then mean that the French intelligence services failed in their apprehending of an agent and, more ethically dubious, in their justified execution of a human being.

Another perspective on the success–failure dichotomy relates to an instance when Mata Hari was attempting to travel back to the Netherlands. On this journey the British ‘mistakenly identified her as a woman called Clara Benedix, who, like Mata Hari, was suspect and on the intelligence services’ list of those to be watched’ (Craig Citation2017: Chapter 11). Like the situations teased apart earlier, this instance can be read in a multitude of manners. Let us assume that Mata Hari was mistakenly identified as someone else. This would suggest that the British and French not only failed in their efforts to identify Mata Hari as an agent, but also to detain Clara Benedix— who was clearly a person of interest. On the other hand, Mata Hari’s brief detention was enough to have her flagged and reported to the French authorities, who in turn identified her as a person of interest that the British should keep tabs on. This would then suggest that Mata Hari failed in her attempts to move through Europe undetected. A third possible reading of this situation is that Mata Hari was, in fact, Clara Benedix—an agent who has never been fully identified by historians—and was not caught by the British and the French and thus succeeds in shielding her alter ego while the Allies fail in their attempts to detain Benedix. The possible reading of whether an undertaking or instance constitutes failure or success is incredibly varied. Part of the reason that this is the case is because the denotation of success and failure is dependent on the perspective and context of a given undertaking. It is also the case because of how espionage has been conceived of and framed throughout history.

THE BLURRING OF SUCCESS AND FAILURE

Up until this point the analysis of the Mata Hari has been an exercise in understanding both perspectives of failure and success in any given moment. It is in many ways a demonstration of the potential multitudinous reality that an undertaking in espionage can be identified as having. The trouble with the analysis so far is that it does nothing to challenge the assumption that endeavours in espionage are isolated instances that have not been pre-calculated. And this is most certainly not the case. The blurring, or perhaps I should title it a lack of distinction, between success and failure is not only an issue of analytical positioning but is in fact built into the constructs of espionage and any intelligence efforts. Support for intelligence initiatives is predicated on the position that through such support a nation, or even corporation, will be successful in their efforts.

In the case of Mata Hari the support for the French Intelligence Services, the Deuxiéme Bureau as it was called then, was due to a belief that through such support the French, and by extension the Allies, would obtain the upper hand in the conflict with the Central Powers of the First World War. Mary Craig documents the efforts made by Georges Ladoux, the head of the Deuxiéme Bureau during the First World War, to convince the upper ranks of the French government to support intelligence work.

By September 1915, France and her allies had suffered several military defeats. The war had changed and the national mood was ugly. General Joffre was out of favour with the government and a culture of blame was starting to develop. It was at that moment that Ladoux stressed again the role of espionage, both in generating military intelligence and thwarting enemy agents. (Craig Citation2017: Chapter 10)

This question drives to the heart of how success and failure can co-mingle within espionage efforts. As Phillip Knightley wrote in his book The Second Oldest Profession, espionage agencies are difficult to get rid of once established because

the agencies justify their peacetime existence by promising to provide timely warning of a threat to national security. It does not matter to them whether that threat is real or imaginary, and agencies have shown themselves quite capable of inventing a theatre when none have existed. (Knightley Citation1988: 6)

The term ‘theatre’ used by Knightley is no accident. This term in military and intelligence parlance, borrowed from the artistic undertakings, has direct connotations to how an event is framed. In the case of espionage, the distinct framed performance taking place, or proposed to potentially take place, is a narrative of conflict between adversaries. In this sense espionage is not only performative and theatrical, but also dramatic, and in this respect both the success and failure of espionage ultimately has to do with its success or failure as performance, theatre and/or drama.

Dramatic structure can also be applied to other instances within espionage, including the tactics used by intelligences agencies to persuade governments and corporations to undertake clandestine work. If we consider the trial of Mata Hari within this framework it has strong echoes of what Richard Harbinger would refer to as ‘Trial by Drama’ (1971: 122). This could further be extended to Mata Hari’s execution, which not only reads as performative but also dramatic. In both instances the event is defined by the adversarial core structure identified by Harbinger. The same realities govern the methods through which espionage agencies justify their existence; there is an adversary external to the agencies and the institutions they are affiliated with. Due to this reality espionage is necessary for successfully deterring such an adversary. Parallel to this, the execution of Mata Hari is a theatrical event that communicates successful intelligence work: an agent of the adversary was apprehended through successful intelligence work and her capture is proof of the success. But just as success exists within a particular context or event, failure also reads in a given scenario. In more plain terms, the success also hints at what might have been potential failure.

Capitalizing on this, espionage bureaus have developed a strong ability to conjure up success out of nothing and perpetuate a state of action and self-justification. This self-justification is based on three principles, according to Knightley, which ‘ensure survival’. He writes;

The first is that in the secret world it may be impossible to distinguish success from failure. A timely warning of attack allows the intended victim to prepare. This causes the aggressor to change [their] mind; the warning then appears to have been wrong. The second proposition is that failure can be due to incorrect analysis of the agencies accurate information—the warning was there but the government failed to heed it […] The third proposition is that the agency could have offered timely warning had it not been starved of funds. (Knightley Citation1988: 6)

What Knightley lays out for his reader almost seems as if it could have been taken from the playbook of La Deuxiéme Beureau in the lead up to Mata Hari’s execution. As historians have identified, the likely scenario that befell Mata Hari is that she was used as a sacrificial lamb to shore up support for espionage efforts within the French military establishment and to galvanize support from the French public more broadly. Likewise, the Germans exploited her by allowing her sacrifice to take place to ‘distract attention from other agents’ (Craig Citation2017: Chapter 13). The strongest evidence that supports this position is that by the time Mata Hari was employed by the Allied forces, the French had already begun to intercept coded German broadcasts, which the Germans were aware of but continued to send anyway in a manner that easily identified Mata Hari as an agent of theirs. The speculation that arises from this is that the Germans used Hari as a distraction to allow agents like Clara Benedix more manoeuvrability in their work. Concerning the French, ‘Ladoux testified that he had never employed her as an agent for France, but had merely pretended to do so in order to entrap her’ (Shipman Citation2007: 340). Herein lies yet another strange reality found in espionage; that shared success can be found for both opposing parties within a failed event. This is particularly pronounced in the fast-moving pace of immediate conflict such as war, but is likewise the case within less intensive periods such as in corporate espionage. This ability to generate success out of failure is an intriguing aspect of espionage. Indeed, it runs against the very notion of success and failure as finite instances. But this (re)generational ability is found in other areas, and one of those is theatre.

THE DEATH OF CHARACTER IS POETIC FAILURE

Before progressing any further I will now take this moment to kill off Mata Hari. Who remains is the woman Margaretha Zelle McLeod. The reason that I can, and will, undertake such a terminal act is because the character created by Zelle McLeod is just that, a character—a construct of a woman who is performing a role. The richness in this case study is that Margaretha Zelle McLeod was at various points navigating upwards of three, perhaps even four, identities within a given instance. These included her original birth identity, her identity of exotic dancer, as well as her identities as both German and French agents. The most famous persona—her character as the exotic dancer—was formed out of both the necessity to survive after arriving in Paris, and due to her artistic success. It was, as Mary Craig notes, ‘a shrewd move, blurring the lines even more about her origins’ (2017: Chapter 6). This was a performance that tapped into the exoticism at the centre of the Orientalist art movement captivating much of the Western world at the time. The formulated identity developed by Margaretha Zelle McLeod capitalized on otherness, while the execution by French authorities was, as suggested earlier, a resounding rejection of otherness.

The death of Zelle McLeod and her exotically fashioned character is remarkable for a myriad of reasons beyond the theatricality presented throughout the staging of the execution. One of the more interesting instances that concerns this study is how Zelle McLeod’s death falls within the notion of the ‘Death of Character’ as described by Elinor Fuchs. Fuchs’s original article on the subject, which precedes Hans Thies-Lehman’s publication Post-Dramatic Theatre by nearly two decades, proposed that a shift in live performance took place in the transition from modernism to post-modernism, defined in part by the decentring of character; ‘just as Character once supplanted Action, so Character in turn is being eclipsed’ (Fuchs Citation1996: 171). The reformulation proposed by Fuchs one decade later in her monograph The Death of Character identifies the exploding of character in domains both inside and outside the traditional theatre space as being central to the shift of what we might now call postdramatic theatre. In respect to this project, one of the more resonant postulations within Fuchs writing is how the ‘death of character’ applies to a lived reality. Echoing Richard Foreman’s speculations on Ontological-Hysteric Theatre, which Fuchs describes as ‘the vision that what we have taken to be human identity disintegrates on scrutiny into discrete sentences and gestures that can be perceived as objects’, she then extends this position to ‘the divisions [of her] own character’ (172–3). In turn I would apply this to Zelle McLeod’s alternate persona and her very being. The death of both Zelle MacLeod and her various characters are a result of failure and are theatrical in nature, but also generative of success. With the destruction of MacLeod’s character comes the destruction of her actions, sentences, gestures and more. The death of a clandestine operative’s character not only signifies the destruction of who they represent, but also the individual qualities of such a persona. In the case of Mata Hari, with her destruction comes the elimination of her behaviour, which might include her enjoyment of sex or her so-called dance performance, but also the threat she represented as a foreign agent. Furthermore, and in respect to acts of espionage, such destruction is a permanent purging of the knowledge an agent carries with them. In a sense it is the termination of the embodied archive. Espionage in turn relies on this activity. If we think about one of the three central tenants of espionage as a phenomenon identified by Knightley—that espionage relies on instances of success in combating foreign agents to justify its existence—it is possible to conclude that the destruction of character acts as the post-dramatic event that communicates this theatrical ruse.

The suggestion that Fuchs makes aides us in placing the death of Margarethe Zelle McLeod’s characters, and any other characters employed by clandestine agents, within the tradition of post-dramatic theatre. Indeed, it could be argued that espionage as signified by the death of character is an instance of post-dramatic or post-modern performance that precedes its theorization. It might even be argued that espionage not only acts as the vanguard of military and political initiative, but is also within the vanguard of the post-modern theatre tradition. This possibility requires even further consideration. The death of character gestures towards a particular type of performance event, one that Fuchs has described as ‘Performance Theater’. She explains:

Performance Theater bears some similarity to the conventional theater of dramatic texts in situating the theatrical event in an imaginative world evoked by visual, lighting, and sound effects, and an ensemble of actors. Yet it is like performance art in two signal regards: in its continuous awareness of itself as performance, and in its unavailability for representation. (Fuchs Citation1996: 79)

Positioning Zelle McLeod’s exotic dance character within this framework is only logical, particularly when McLeod reinvents herself and begins to identify publicly with the name of Mata Hari outside of the theatre and dance venues she frequented. The erotic character McLeod creates and lives as is a continuously aware performance blurring the lines between the real and the representational. The same is true for the agent identities employed by Zelle McLeod, which is also true of any clandestine agent identity. The outward persona becomes a lived reality while at the same time wholly representational.

Representation is perhaps the most critical element when thinking through the death of character. When considering the notion of representation often a mimetic understanding of the word is drawn upon. But espionage blurs the boundary between the representational and the non-representational, while also embracing failure. In her work Performance Theatre and the Poetics of Failure Sarah Jane Bailes identifies, as Feltham does, that failure is often positioned as an undesirable outcome, or at the very least something that should not happen. Bailes explains that failure can be read in a multitude of manners but, in her estimation, theatre and performance are most often concerned with two. For her own work Bailes declares that ‘more than a concern with representations that fail (of which clearly there are many) it is the failure of representation that focuses my inquiry’ (2011: 12). For this essay I am concerned with both. My reading of Bailes’s work informs me that there is significant cross-over between both the failure of representation and representations that fail. Due to the cyclical nature of failure and success, to most effectively understand the relationship between espionage and theatre and performance these two views of representation and failure should not be considered independently from each other. To do so would be like analysing a mirror and only thinking about the image within the mirror, while ignoring how that mirror comes to reflect the image in the first place.

With the goal of understanding how representations fail and a failure of representation occurs, it is necessary to cycle back to the understanding of failure. What Bailes identifies, like Knightley, is that failure is not only a result but also a (re)generative departure point. She sets out the parameters of failure with a focus on two core ideas: the first concerns Fuchs ‘Performance Theatre’ and the second J. L. Austin’s ‘performatives’. In invoking Fuchs’s definition, Bailes situates her work within a lineage that is indebted to avant-gardism. Her citation of terms such as ‘live art’ (7), ‘experimental theatre’ (18), and ‘performance art’ (21), to name but a few, further illustrates the cross-pollination that was, and still is, taking place in these artistic endeavours. She groups together work by companies such as Goat Island, Forced Entertainment and Elevator Repair Service in an effort to prove that the failure at the core of this style of artistic work is rooted in aesthetic and compositional methods that embrace failure, which at their core are an embracing of the ephemeral nature of live art. Moreover, she explains how failure can be used as a compositional tactic in the production of theatre events to illustrate the tenuousness of success. Espionage can and should be viewed within many of these parameters. As has been noted, clandestine initiatives most certainly embrace failure as a practice, and even build moments of failure into their strategies, such as the telegraphs sent by the Germans that outed Mata Hari. Espionage and its undertakers are also highly aware of the ephemeral quality of moments and endeavours, and often exploit this nature to further their initiatives: instructions are destroyed, informant networks are setup to be dismantled quickly and every undertaken action is meant to be imbued with plausible deniability.

The aesthetics of failure and representation are also of significant importance. What they offer is an understanding of how failure is both identified and imagined. In respect to identifying failure, there is perhaps no greater example than the death of character. Such destruction of character offers perspectives on the instances of failure, and thus the generation point of successes. The insight that an aesthetic understanding of failure offers does not end there. As O’Gorman and Werry write in the introduction to Performance Research: On failure, an employment of failure and representation in performance ‘strategically mobilizes failure to imagine alternatives foreclosed by the normative tyranny of success and expected outcomes’ (2012: 2). Herein lies one of the central ideas of failure and success in espionage as theatre and performance— imagined futures. As Knightley might suggest, the imagined alternative is a potent force in the future justification of espionage. The technique used by clandestine agencies to justify their funding is to demand that governments and corporations imagine the conflagration that will take place if they are not successful in their work. Such potential and imagined futures are truly tactical, helping espionage agencies push forward their agenda. More interestingly still, it is an instance of futurity that departs from utopic use identified by scholars such as Jill Dolan, or Rachel Bowditch and Pegge Vissicaro.

The theatricality around the death of character is not the only area of espionage in which failure is engaged. Much like the broken-down elements identified by Foreman in hysteric ontological theatre, the performative elements in the day-to-day exchanges that are at the core of espionage also encounter instances of failure. There is an infamous example cited by First World War I spy-training programmes that document an instance when an agent failed in his undercover work and was caught out in his role as a spy during the Second World War. The story highlighted how the agent, after landing in France undercover, proceeded to enter a café and request a café noir—a black coffee—even though milk was being rationed and all coffees ordered were assumed to come black without the distinction being made in the ordering process. In this instance, the operative was immediately outed as a foreign agent due to his misfire within the cultural and transactional exchange. Such misfires and misexecutions are the second core idea influencing Bailes’s conceptualization of poetic failure. She writes that failure ‘indexes the infelicitous outcome of a designated task or action, to invoke J.L. Austin […] The act—a performative speech act in his discussion— always exhibits a number of conditional needs or properties to ensure its felicitous outcome’ (Bailes Citation2011: 4). The central notion presented by Bailes is that failure in performance (particularly performance theatre) hinges on the idea of felicitous/infelicitous outcomes. The companies at the centre of her study embrace infelicity and lean into these moments with gusto. She explains that utilizing such a technique depicts a moment where the experience of watching this work is much like seeing the ‘haphazard disassembling of its parts’ (34). These instances of failure, identified in this case as intentional infelicity, are the other critical moments of espionage viewed as performance theatre. Espionage organizations look to exploit infelicitous moments, while simultaneously being threatened by the potential of their happening. This, in turn, speaks to the dialectic of success and failure that defines espionage.

The significance in identifying these aspects of Bailes’s definition of failure is that it provides a rich departure for understanding failure in modes of theatre and performance, and more specifically contemporary espionage. Moreover, case studies of agents, particularly failed agents like Zelle McLeod, provide unique insight into these instances of failure and thus (re)generation points of success. Understanding that a postmodern performance perspective enables us to view the disassembled parts of a whole, further allows us to consider both the micro and the macro instances of espionage within a given context. And understanding the aesthetics of the ‘failure of representation’ along with how ‘representations fail’ within espionage— representations like Mata Hari—allows us to conduct analysis of clandestine work, an otherwise opaque world, but one of performance theatre.

REFERENCES

- (1917) ‘A story’, Le Petite Parisien, 16 October.

- Althusser, Louis (2001) Lenin and Philosophy and other essays, trans. Ben Brewster, New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- Bailes, Sarah Jane (2011) Performance Theatre and the Poetics of Failure: Forced entertainment, Goat Island, elevator repair service, Oxon: Routledge.

- Blyth, Caroline (2017) Reimagining Delilah’s Afterlives as Femme Fatale: The lost seduction, New York, NY: T&T Clark Bloomsbury.

- Bowditch, Rachel and Vissicaro, Pegge (2017) Performing Utopia, Kolkata: Seagull Books.

- Carlson, Marvin (2002) The Haunted Stage: The theatre as memory machine, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Conquergood, Dwight (2002) ‘Lethal theatre: Performance, punishment, and the death penalty’, Theatre Journal 54(3): 339–67. doi: 10.1353/tj.2002.0077

- Craig, Mary W. (2017) Tangled Web: Mata Hari dancer, courtesan, spy, Kindle edn, Stroud: UKL History Press.

- Dolan, Jill (2010) Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theatre, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Feltham, Colin (2014) Failure (The Art of Living), Kindle edn, Milton: Taylor & Francis.

- Foreman, Richard (1976) ‘Ontological-Hysteric: Manifesto I’, in Kate Davy (ed.) Richard Foreman: Plays and Manifestos, New York: New York University Press, p. 73.

- Foucault, Michel (1975) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan, New York: Vintage.

- Fuchs, Einor (1996) The Death of Character: Perspectives on theater after modernism, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Hanson, Helen and O’Rawe, Catherine (2010) ‘Introduction: “Cherchez la Femme”’, in Helen Hanson and Catherine O’Rawe (eds) The Femme Fatale: Images, histories, contexts, London, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–8.

- Harbinger, Richard (1971) ‘Trial by drama’, Judicature 55(3): 123–8.

- Henry, Bill (1967) ‘Window on Washington’, Los Angeles Times, A1, 29 November.

- Knightley, Phillip (1988) The Second Oldest Profession, New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Lehman, Hans-Thies (2006) Postdramatic Theatre, Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis.

- O’Gorman, Róisín and Werry, Margaret (2012) ‘Editorial introduction’, Performance Research: On failure (on pedagogy) 17(1): 1–8. doi: 10.1080/13528165.2012.651857

- Shipman, Pat (2007) Femme Fatale: Love, lies, and the unknown life of Mata Hari, Kindle edn, New York, NY: HarperCollins e-books.

- Wales, Henry (1917) ‘The execution of Mata Hari’, International News Service, 19 October.

- White, Rosie (2010) ‘”You’ll be the death of me”: Mata Hari and the myth of the femme fatale’, in Helen Hanson and Catherine O’Rawe (eds) The Femme Fatale: Images, histories, contexts, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 72–85.