Abstract

In ‘(C)Overt Operations: Detective disguise and the threat of deception,’ Isabel Stowell-Kaplan explores the productive tensions and contradictions rife in the theatrical performance of undercover operations. Beginning with the introduction of the New Police in the mid-nineteenth century, the article shows how the institution of a centralized police force in London laid bare anxieties about police power and the sort of state surveillance the British associated with revolutionary France. These concerns quite literally shaped the initial force. The ‘bobby’ was employed in conspicuous policing; he was to deter criminals and prevent crime by virtue of his very visible presence. What then do we make of his plainclothes counterpart? No longer badged or uniformed, how did the new detective visibly perform his police work in a country not always comfortable with his plainclothes presence? One answer to this question could be found in mid–late nineteenth-century detective drama, beginning with Jack Hawkshaw—the first English detective on the stage. ‘C(O)vert Operations’ explores how Hawkshaw’s showy performance fit within a melodramatic schema that valued clarity and moral legibility. In Detective Hawkshaw’s hands, and those of many of his successors, ‘undercover’ was a synonym for ‘disguise’, and dramatic disguise at that. It was, in other words, simultaneously clandestine and flashy, indicative of the contradiction at the heart of performing ‘undercover’. It was, moreover, a propensity shared by the detectives’ stage nemeses, and thereby threatened to bring the detectives uncomfortably close to those they pursued. Examining nineteenth-century plays such as The Ticket-of-Leave Man (1863), The Detective (1875), Handcuffs (1893) and Sherlock Holmes (1899), the article investigates the implications of this uneasy association between the detective and the criminal, showing how nineteenth-century detective drama explored the social and theatrical consequences of going ‘undercover’, where police work, criminality, and theatrical fraud and deception merged.

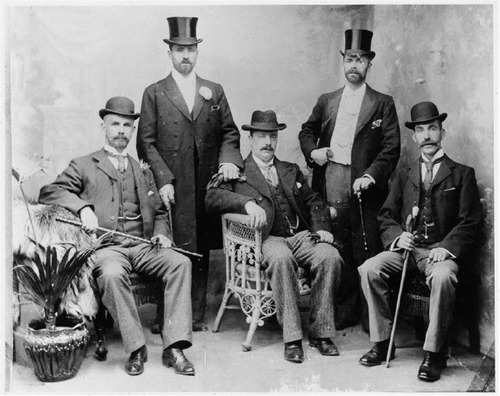

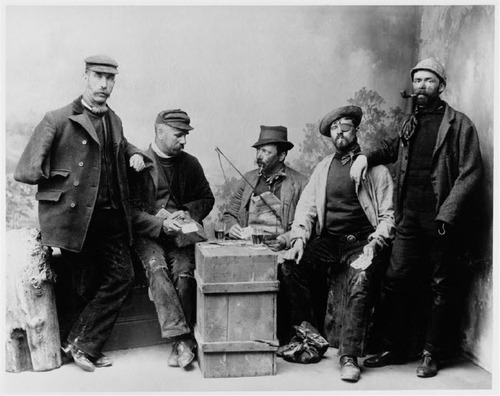

A pair of apparently twinned photographs from 1911 project two strikingly different images of five officers from the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the Metropolitan Police. In one photograph, the men are dressed in formal attire, complete with tops hats, buttonholes and pocket squares (). In the other, the same men appear undercover as dock workers—the elegant evening clothes have been replaced with flat caps, ripped trousers and dirty shoes (). The photographs seem primed to evidence the performative skills of these officers, showing off the elaborate and effective lengths to which they will go ‘undercover’. The second image shows the officers’ obvious commitment to the dramatic with a clear prioritization of the theatrical over the practical. One man appears to have compromised his vision for the striking effect of an eyepatch. Another has tied up his jacket sleeve to give the impression that he is an amputee and a third has replaced his left hand with a hook. It is hard to imagine that maintaining the ruse that you are an amputee would have been a particularly effective or even feasible strategy when working undercover. And while the replacement of a hand for a hook by the man on the far right may be intended to evidence his role as a dock worker—supposed perhaps to be a stevedore’s hook often carried by those in the trade—the officer has deployed it in such a way that it appears to be not so much a tool as a replacement for a missing hand, or, if viewed through a particularly theatrical lens, may be supposed to be a pirate’s hook.

Fig. 2 The same CID officers dressed as Dock Workers (1911). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Police Heritage Centre

Each man’s commitment to his individual disguise is compounded by a more general interest in performance practice. That is, not only is each man engaged in an individual ‘undercover’ performance, but the staging and taking of the photograph itself suggests a more general, force-wide, belief in the importance of performance practice. The dock worker photograph is not an image of these policemen at work, nor is it an image taken to serve as a useful catalogue of police disguise, a sort of inverse of the criminal mugshot. It is instead a staged studio portrait that revolves around a dramatic scene—the men seeming to drink and play cards—with attractive poses and variable ‘levels’ maintained in front of a cloth backdrop. Moreover, the existence of the two images, rather than simply the second one, suggests an investment in the process of performance. The twinning of the two photographs effectively provides a ‘before’ shot and an ‘after’, encouraging a performance of spectatorship in which each viewer is invited to comparatively assess the two images, taking note of the profound differences.Footnote1 The process of disguise is underlined as each viewer is invited to cast their eye back and forth, thereby establishing the true extent of the performance maintained. While it is impossible to establish whether these disguises were ever actually deployed as part of any undercover operations, it is certainly true that in 1911 the police had more than one reason to want to infiltrate the world of the dock workers. Not only were there concerns in the period about drug smuggling into the Limehouse Docks, but the summer of 1911 was one of international strike action at the ports. The police therefore had both criminal and political reasons to want to be taken for dock workers.

In this article I explore the productive tensions and contradictions rife in the kind of theatrical performance epitomized by these photographs. With police going undercover onstage and off, theatrical play and police performance became mutually affective as the appearance of performing police shaped the role and reception of the force in complex ways. In one sense, the association between theatre and policing infused the force with the levity of entertainment, both opening the door to critiques of unseriousness and misplaced priorities, and simultaneously providing perfect cover for the threatening nature of a new force by costuming it in droll wigs and whiskers. In addition, the complex and often contradictory reception of theatre and entertainment genres of the mid-nineteenth century meant that this ongoing association might at once tarnish the police by association with petty grifters and overlay their work with the moral clarity of melodrama.

Beginning with the introduction of the New Police in the mid-nineteenth century, I will show here how the institution of a centralized police force in London laid bare anxieties about police power and the sort of state surveillance the British associated with revolutionary France. These concerns, I argue, quite literally shaped the initial force. The ‘bobby’ was employed in conspicuous policing; he was to deter criminals and prevent crime by virtue of his very visible presence. What then do we make of his plainclothes counterpart, introduced some years later? No longer badged or uniformed, how did the new detective visibly perform his police work in a country not always comfortable with his plainclothes presence? This question, I suggest, was answered by mid–late nineteenth-century detective drama, beginning with Jack Hawkshaw—the first English detective on the stage. Examining Hawkshaw’s showy performance—a performance that, much like that of the detectives in the photographs, suggested both conspicuous inconspicuousness as well as dramatic disguise—I will explore how it fit within a melodramatic schema that valued clarity and moral legibility. In Detective Hawkshaw’s hands, and those of many of his successors, ‘undercover’ was a synonym for ‘disguise’, and dramatic disguise at that. It was, in other words, simultaneously clandestine and flashy, indicative of the contradiction at the heart of performing ‘undercover’. It was, moreover, a propensity shared by the detectives’ stage nemeses, thereby threatening to bring the detectives uncomfortably close to those they pursued. Examining mid–late nineteenth-century plays such as The Ticket-of-Leave Man (1863), The Detective (1875), Handcuffs (1893)—likely the first ‘bent copper’ play—and Sherlock Holmes (1899), I investigate here the implications of this uneasy association between the detective and the criminal. In this way I will show how nineteenth-century detective drama explored the social and theatrical consequences of going ‘undercover’, where police work, criminality and theatrical fraud and deception merged.

The commitment to performance practice and the dramatic skill latent in covert police work demonstrated by the above photographs in fact gestures to much earlier conversations about the visibility of plainclothes officers. A piece published in February of 1882 in Macmillan’s Magazine titled ‘The French Detective Police’ suggests that even when these officers were not calling attention to their elaborate and dramatic disguises they nevertheless remained visible:

Not many months past I was having my shoes cleaned outside the Charing Cross Station, when I noticed two well-built, well-set-up, active-looking men standing near me. They were in plain clothes, and yet their dress was so much alike that they might almost be said to be in uniform. I remarked to a friend who was with me that they looked like soldiers of the guards in mufti. Upon this the youngster—a mere boy, certainly not more than twelve or thirteen years of age—who was brushing away at my feet, looked up at me, winked, and said—‘No, sir, them beant soldiers; they’s detectives, they is.’ ‘How do you know?’ said I. ‘Oh, sir,’ was the answer, ‘we knows all them plain-clothes officers. They try to look like other folks; but it’s no good. We can tell them as well as if they wore helmets and blue coats.’ (Meason Citation1882: 301)

Despite their attempts to ‘look like other folks’, there is something about their build, dress and even attitude that draws the eye of the observer and the identification of the youngster. While to a twenty-first century reader this may sound like basic incompetence—what good are undercover officers if they remain readily apparent to any and all?—such overt covert behaviour may in fact have been no bad thing. In a piece that may in fact be an earlier iteration of the story cited above, published some five years earlier in All the Year Round, the author goes to great lengths to distinguish the French detective from his English counterpart on the precise basis of the former’s ability to remain truly unknown. In the tale, the French master of disguise argues that the English ‘secret police’ are entirely incapable of being truly secret. They are, he insists, ‘no more secret than your police in uniform. Everybody knows them, and they even dress so exactly alike that they might as well wear the blue tunic with the number on the collar’ (‘A French Detective Story’ 1877: 369). The insistent visibility of the English plainclothes policeman may be laughable to our French antagonist, but it may yet speak well for him in an English context. This is because throughout the nineteenth century there was continuing anxiety in the country about the possibility that their still relatively young police force could yet turn into the covert system of government surveillance fretfully associated at the time with France. Concerns about the status and purpose of the New Police (or Metropolitan Police), initially established in 1829, were in fact so strong that they helped to shape the very development and introduction of the new force.

The appearance of a thousand new officers on the streets of London in September of 1829 marked an important moment in what was an extended and often fractious political process. While early histories of the police have tended to view this new force as the necessary work of far-sighted reformers, doing away with an inefficient and patchwork system of beadles and Bow Street Runners, such an attitude can obscure the fiercely contested position of this new force. By the early nineteenth century, following almost a hundred years of debate about crime and disorder, some were in favour of introducing a more comprehensive and centralized force but others remained passionate critics. Even in the face of the brutal Ratcliff Highway murders of 1811—in which seven people from two different families were slaughtered in their homes—the Earl of Dudley might yet observe that

they have an admirable police at Paris, but they pay for it dear enough. I had rather half a dozen people’s throats should be cut in Ratcliffe Highway every three or four years than be subject to domiciliary visits, spies, and all the rest of Fouché’s contrivances. (Earl of Dudley cited in Philips Citation1980: 174)

Dudley’s invocation of both ‘Paris’ and ‘Fouché’—Napoleon’s much-feared Minister of Police—locates a major source of the concern at the time: First Empire France. There was a very real fear, among certain Englishmen, that what they saw as French-style policing—characterized by spies and government overreach—would infringe upon the rights of the native English gentleman whose home was still very much his castle. While striking dock workers were unlikely to be foremost in the thoughts of the Earl of Dudley, it is interesting to observe that the kind of political interference made possible by the dock worker costumes of the 1911 CID is precisely the sort of government overreach initially feared by some. Twenty years following Dudley’s strongly expressed views and these sentiments were still openly expressed, evident, for instance, in an anonymous 1830 poem, ‘The Blue Devils, or New Police’, which contains a note stating that

the people of the present day, have not unfittingly christened this force by the name of Jenny Darbies— the English way of pronouncing gens d’armes, a French civil force, or military espionage, which answers the twofold purpose in that country of watching the streets and watching the people. (cited in Clarkson and Richardson Citation1889: 70)

Given such strong resistance to a surreptitious system of continental-style surveillance, it is perhaps not surprising that there was a certain visibility written into the first officers—a good example of the ways in which surveillance practices (or indeed the threat of them) could become effecting and performative within society, as James M. Harding argues in Performance, Transparency, and the Cultures of Surveillance (2018). The initial instructions given to each man upon his induction into the force were published widely in the London newspapers. The Times printed them in full, dedicating more than a sixth of its spread to them. And just as the instructions were visible to the newspaper-reading public at large, so too were the men. Once outfitted in the ‘suit of blue cloth’ and the ‘tall chimney-pot hat’ with a ‘leather stock worn high inside the collar to guard the officer against strangulation’ each man was required to wear it at all times, whether on duty or not (Clarkson and Richardson Citation1889: 65; Dell Citation2010: 4). Moreover, as Haia Shpayer-Makov argues, by the end of the nineteenth century it was clear that physical stature was a key component in police selection: ‘while the physical examinations were demanding,’ she notes, ‘the educational tests were minimalist’ (2002: 35). By the turn of the century, the average policeman was about five inches taller and three stone heavier than his army counterpart (39). This ‘physical stature’, Shpayer-Makov observes, ‘meant conspicuousness’ (37). And so, while there was doubtless pragmatic purpose to having large men patrolling their beats—predictable paths they traced through the metropolis—such impressive physicality, like the uniform and the ‘beat’ itself, also served the function of visibility.

The hyper-visibility of the ‘bobby’ meant that performance was written into the earliest history of the English police constable. By contrast, the detective, introduced some thirteen years later, lacked the obvious markers of police performance. Established following a request by the Police Commissioners in 1842, the new ‘detective body’ consisted of eight officers—two inspectors and six sergeants—out of a force of approximately 4,000. No longer a man in uniform walking the beat, how did the detective perform his police work in a country still anxious about his plainclothes presence? The 1911 images of the CID and the tales published in Macmillan’s Magazine and All the Year Round suggest one approach. Perhaps by emphasizing the overt nature of his covert work, the new detective could go undercover without becoming one of Fouché’s insidious spies. Other questions, nevertheless, arise. Could he ever be sufficiently visible to assuage these concerns? Did, moreover, any work pursued undercover risk bringing the detective into disrepute, aligning him with the very people he sought? Answers to these questions can be found, I suggest, in the detective drama of the period. Primed to tackle such questions about deception, fraud and the possibility of (c)overt police work, the stage detectives of the mid–late nineteenth century helped to address the contradictions inherent in the act of performing ‘undercover’.

Stage detectives proliferated in British theatre from the 1860s onwards. Beginning with Jack Hawkshaw, the lead detective in Tom Taylor’s 1863 play, The Ticket-of-Leave Man, the stage detective appeared in dramas across the capital and country. The 1860s delivered Dion Boucicault’s Foul Play (1868) and Presumptive Evidence (1869) as well as G. B. Ellis’s The Female Detective (1865), William Travers’s The Boy Detective (1867), Watts Phillips’s Maude’s Peril (1867) and another Tom Taylor play, Mary Warner (1869). In the 1870s, numerous detectives made the leap from page to stage, including Dickens’s well-known Inspector Bucket of Bleak House and Sergeant Cuff from Wilkie Collins’s runaway-success The Moonstone. Clement Scott’s aptly-titled The Detective was produced at the Mirror Theatre in 1875 and, by 1878, there was even an application made to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office for a play titled The Dog Detective. The 1880s and 1890s saw Henry Arthur Jones’s The Silver King (1881), featuring Detective Baxter, as well as Mark Melford’s The Secrets of the Police (1886) and Handcuffs by E. Stockton and E. V. Hudson (1893). By 1899, perhaps the most famous detective to grace the stage appeared in a titular drama, Sherlock Holmes. Penned by American playwright and actor William Gillette, Sherlock Holmes was a runaway success, with revivals touring the US and UK for more than thirty years.

These stage detectives seemed primed to go ‘undercover’, with many relishing the performance opportunities that arose from the nature of disguise. Taylor’s foundational detective, Jack Hawkshaw, certainly seemed to revel in the disguises put towards his policing ends. In the final act of The Ticket-of-Leave Man (1863), Hawkshaw, played by Horace Wigan, dons an elaborate disguise. Appearing as a navvy, Hawkshaw’s disguise consists not only of ‘rough cap, wig, and whiskers’ but also a ‘country dialect’, and, as the scene continues, a performance of increasing intoxication (Taylor Citation1985 [1863]: Act 4, Sc 1; 219 and 208). When Wigan appeared again as a stage detective just over a decade later, in Clement Scott’s The Detective (1875), he again was called upon to go ‘undercover’. As the critic for the Globe and Traveller reported, ‘Mr Wigan acted capitally as the detective, and was quite unrecognizable in his disguises’ (31 May 1875). The first he dons is that of an Irishman, dressed ‘as the Irish singer and dancer of the racecourse, with a shillelagh, piece of board under one arm, and a few bottles of champagne under the other’ (Scott and Manuel Citation1875: Act 2, Sc 2; 32). And like his predecessor Hawkshaw, Walker’s performance consists of an accent to match:

WALKER. (As Paddy): Save me, bhoys! Save me for the love of Heaven! Its [sic] lynchen law they’re havin’ wi’ me; I shall be kilt entirely. (Act 2, Sc 2; 32)

In the following act, Walker appears in his second disguise. This time he is ‘dressed as a French sailor, red shock head and whiskers’, with a ‘French accent’ complete with his own Franglais: ‘Vous comprenez ce qus je dis, ze lady of ze murder, ze chanteuse de l’assassinat’ (Act 3; 45).

Similarly, in C. H. Hazlewood’s popular play The Mother’s Dying Child, produced at the East End Britannia Theatre in 1864, and featuring a proto detective in Florence Langton, the ability to go ‘undercover’ was effectively the defining element of the play. As a recurring advertisement for the play in the Shoreditch Observer was at pains to point out, the play’s lead actress would, during the course of the show, ‘sustain five different characters’ (1, 8 and 15 October 1864). The lead actress of whom they spoke was none other than Sarah Lane: the theatre’s star performer who had a reputation for her virtuosic range. As a biographer for The Stage noted in 1882, ‘to recapitulate the characters which Mrs. Lane has enacted at one time and another would be an almost impossible task’ (‘Our biographies’ 1882: 10). In Hazlewood’s drama, Lane’s performance as Langton requires that she be disguised variously as ‘Grizzle Gutteridge—a Somersetshire Wench’, ‘Mrs. Gammage—an ancient Nurse’, ‘Mr. Harry Racket—a fast young Man’ and ‘Barney O’Brian—from the Bogs of Ballyragget’ (Hazlewood Citation1864: Cast List; 2). While Detective Ben Burleigh does not take on quite so many disguises in E. Stockton and E. V. Hudson’s play Handcuffs (1893)—produced at the Theatre Royal, Nottingham—he does, at one point, enter ‘disguised as a coster [monger] and pushing a fish barrow’ and at another appear as a cabman (Act 2, Sc 1; 109). Finally, William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes ensures he does not miss the opportunity to go dramatically undercover, appearing in the final act of the play as ‘a white haired OLD GENTLEMAN in black clerical clothes [and] white tie’ (Gillette Citation1983: Act 4; 259). Indeed, Gillette adds much more elaborate costume specifications in his own hand in one early typescript version of the play, citing that he’ll need, ‘White wig (loose) with small side-whiskers attached. Forehead pieces, with white bushy eyebrows—to fasten on with 2 elastic bands around behind head. False nose (papier)—secured with just a trifle of cement or glue at the tip’ (Gillette Citation1899: Act 4; 15).

There are clear elisions here between theatrical performance and police performance, as the detective characters take advantage of their dramatic environment and the histrionic skill of those who play them. Indeed, Lottie D’Esterre, the cockney Music Hall performer who serves as Ben Burleigh’s love interest in Handcuffs, notes as much herself. When she sees Burleigh disguised as a costermonger, she compliments him on his costume and suggests he take to the stage: ‘Well you do look a treat in them togs and you do take a coster proper—Why don’t you go on the stage Ben?’ (Stockton and Hudson Citation1893: Act 2, Sc 1; 119). This obvious overlap, between stage performance and police undercover work, might seem to undermine the seriousness of detective business. Indeed, the critic for The Telegraph complained that Detective Hawkshaw’s multiple disguises implied his misplaced priorities, noting that he seemed to have ‘as many characters to personate as if he had to contribute to the amusement instead of the safety of society’ (29 May 1863). Such investment in disguise might be problematic for the police force, indicative not only of the kind of unattractive levity identified by The Telegraph critic, but also because it might suggest a certain investment in the sort of deceptive strategies of which the early critics of the British police had been so wary. There was, however, an even more pressing problem for these undercover stage detectives—that is, a problematic similarity between themselves and those they pursued, characterized by their undercover practices.

In every play cited above in which the detective figure puts on a disguise to conduct their work, the criminals pursued do the very same. In The Ticket-of-Leave Man, the leading villain, Jim Dalton, has two alternate aliases listed in the cast list—‘Downey’ and ‘The Tiger’—and appears within minutes of the play’s opening, disguised:

MOSS: (starting, but not recognizing him) Eh, did you speak to me, sir?

DALTON: What, don’t twig me? Then it is a good get up. (He lifts his hat, and gives him a peculiar look.) Eh, Melter?

MOSS: What, Tiger!

DALTON: Stow that. There’s no Tigers here. My name’s Downy [sic]; you mind that John Downy [sic], from Rotherham, jobber and general dealer. (Taylor 1863: Act 1; 166–7)

Dalton’s latest disguise is seemingly so effective as to have fooled even an old associate. Moriarty also takes the opportunity to disguise himself in the final act of Sherlock Holmes and the other villains of the piece regularly pretend to be others in service to their nefarious plans. Shortly after Holmes has appeared as the Old Gentleman, Moriarty arrives dressed as a cabman. And just shortly before Holmes appears in this disguise, Madge Larrabee—the arch-villainess of the play—comes to Dr Watson pretending to be one distressed Mrs Seaton, and, moreover, doing so in a manner that Gillette specifies must be ‘entirely different from that in former scenes’ (1983: Act 4; 256). In a similar vein, Florence Langton’s virtuosic detective work in The Mother’s Dying Child results in the unmasking of a man who has attempted to commit bigamy by way of an elaborate alias.

Clement Scott’s The Detective best highlights the potentially problematic overlap in police and criminal undercover practice by featuring a detective and one of the so-called ‘criminal classes’ in precisely the same disguise. Both Inspector Walker and the aptly named Savage Mike appear, inexplicably, dressed as French sailors. When Walker initially appears, Mike’s criminal compatriot, Sleeky, assumes that he is Mike, observing, ‘Mike, by the Lord! If I hadn’t arranged the fakement myself, burn me, if I should have recognized him!’ (Scott and Manuel Citation1875: Act 3; 45). When Mike does, in fact, appear a few minutes later, ‘dressed exactly like Walker’, confusion reigns (Act 3; 46). Ben Burleigh, the lead detective of E. Stockton and E. V. Hudson’s Handcuffs, never appears in precisely the same disguise as his own antagonist. However, the nature of the plot—Burleigh is on the heels of a corrupt officer successfully living a double life and evading justice because of what he describes as his ‘dual personality’ (Act 2, Sc 1; 106)—means that Burleigh’s own investment in disguise draws him uncomfortably close to his corrupt colleague. The stage detective’s propensity to go ‘undercover’ is seemingly one shared by their criminal targets, as their undercover work seems to implicate them in the very criminal and fraudulent behaviour they are supposed to investigate.

This was of particular significance in this period because, as historian James Cook observes, ‘the new middle-class maintains a well-deserved scholarly reputation for having been deeply concerned—even downright anxious—about questions of fraud in almost every facet of its historical development’ (Cook Citation2001: 26). Cook’s argument is that we ought not to be surprised by a corollary interest in deceptive exhibitionary practices, as the two elements—anxiety about fraud and a willingness to engage with deceptive practices—are two sides of the same coin. As he expands,

[T]here was […] a fundamental paradox at the heart of the cultural defenses. Simply put, the etiquette manuals, advice columns, and city guides seem to have promoted precisely the same anxieties they claimed to alleviate. The cultural work of guarding against social impersonation was never done. (Cook Citation2001: 27)

Cook is here speaking of the mid–late nineteenth-century United States where he regards the presence of and fascination with fraud as deeply enmeshed within the developing capitalist market. There is, however, no shortage of clues that the same anxieties permeated contemporaneous British society. This is especially evident in The Ticket-of-Leave Man. The detective and his criminal counterparts are, significantly, not the only ones engaged in ‘undercover’, fraudulent or deceptive practices. The whole landscape of the play is, in fact, suffuse with fraud or the threat of it. The naïve innocent for whom the play is titled, Bob Brierly, is sent down for passing false notes and many of the characters in the play are both on the lookout for deceptive strategies and employing their own. Just before the exchange cited above, in which Moss fails to recognize Dalton, Moss had himself been considering the worth of the seemingly silver spoon in his hands:

MOSS: (stirring and sipping his brandy and peppermint) Warm and comfortable. Tiger ought to be here before this. (As he stirs his eye falls on the spoon; he takes it up: weighs it in his fingers). Uncommon neat article—might take in a good many people—plated, though, plated.

(While MOSS is looking at the spoon, DALTON takes his seat at MOSS’s table, unobserved by him.)

DALTON: Not worth flimping, eh? (Taylor Citation1985 [1863]: Act 1; 166)

‘Not worth flimping’, that is ‘stealing’, because although the spoon looks silver, to the trained eye (and hand) of a master thief it is clearly plated. Its outside is not indicative of its inside. This is the first of many references in the play to objects that are forged, fraudulent or generally untrustworthy. Just as the characters disguise themselves so, it seems, do the play’s objects.

The character most obviously poised to cut through the fraud that permeates the world of The Ticket-of-Leave Man and the similar plays that followed, is of course the detective. His, or in some cases her, role is to root out criminal deception and expose it to the purifying light of melodrama, a genre in which, as Michael Booth explains, the ‘bright sword of justice always fall[s] in the right place’ and ‘the bags of gold are awarded to the right people’ (1965: 14). However, the stage detective’s own tendency to perform ‘undercover’ threatens to compromise his ability to stand apart from those he seeks. The possibility of confusion between detective and target is one occasionally realized both within and without these detective dramas. At the end of Act 1 of The Ticket-of-Leave Man when Brierly is accosted by Hawkshaw and his detective colleagues for passing the forged notes, he assumes, as David Mayer notes, not that he is being arrested but that he is being garrotted (1987: 34)Footnote2—that is, attacked from behind by criminals intent on strangling him and stealing his possessions:

(BRIERLY has been wrestling with the two DETECTIVES; as DALTON speaks he knocks one down.)

BRIERLY: I have. Some o’ them garottin’ [sic] chaps! (Taylor Citation1985 [1863]: Act 1; 177)

Brierly, unaware that he himself has committed a crime, initially assumes that those plainclothes officers who have unexpectedly set upon him must themselves be the criminals. A notable authorial or transcription error in the Lord Chamberlain’s copy of C. H. Hazlewood’s drama, The Detective, or A Ticket-of-Leave’s Career: A drama of every day life (1863), derived from Tom Taylor’s play, suggests a similar overlap. In Hazlewood’s version of the play, the detective is named Eagleson and nicknamed the ‘Lynx’, while his criminal antagonist, Richard Blackburn, dubbed the ‘Fox’, disguises himself in one scene as ‘Mr Lamb’. While Eagleson is speaking of his plans to arrest Blackburn, he mistakenly uses his own moniker, nonsensically referring to Blackburn as ‘Mr. Lynx’ rather than ‘Mr. Lamb’ or ‘Fox’:

EAGLESON: Thank you Sir. Then I’ll go (aside) to fetch assistance to secure Mr. Lynx—he may escape me if I tackle him myself. I’ll make sure of him this time (Exit). (Hazlewood Citation1863: Act 3, Sc 1; 64, my emphasis)

It’s a small slip certainly, but one that suggests a certain elision between the detective and his target in the mind of the playwright or his transcriber.

Nevertheless, despite this potentially troubling overlap, the manner in which the stage detectives perform their undercover work functions, I suggest, to assuage concerns that they might be precisely that which they seek. Emerging at a time when actors such as Sarah Lane were lauded for their virtuosic skill and popular ‘entertainers’ wowed audiences with their quick-change abilities, the stage detective was able to take advantage of the spectators’ appreciation of visible skill. In her article, ‘Feeling public: Sensation theater, commodity culture and the Victorian public sphere’, Lynn Voskuil outlines this Victorian appreciation of ‘stage business’, relating an 1867 account in which an actor’s on-stage death so impressed the audience that they demanded he ‘die again!’ This, as Voskuil explains, was ‘no slice of life’, but an opportunity for ‘his audience to appreciate his performative talent and recognize his skill in manipulating the conventions of staged death’ (2002: 260). It was, one might even suggest, a specifically melodramatic performance. In a series of essays on notable actors of the period, critic George Henry Lewes outlined his own thoughts on stage and performance traditions. Observing with frankness both the skills and shortcomings of Charles Kean’s work, Lewes explains that Kean was certainly a skilled actor but only of a very specific type. Although, Lewes suggests, Kean was never destined to be a tragedian, he was nevertheless a strong actor of the melodramatic type, which Lewes defines as follows: ‘A melodramatic actor is required to be impressive, to paint in broad, coarse outlines, to give relief to an exaggerated situation; he is not required to be poetic, subtle, true to human emotion’ (Lewes Citation1958: 24–5). Painting in bold, broad strokes these stage detectives successfully perform in this melodramatic mode as each commits to a performance tradition that reveled in shows of histrionic ability. Moreover, by making a dramatic point of each disguise— putting on and throwing off wigs and whiskers, Irish brogues, French dialects and so on—each stage detective paradoxically draws attention to the undercover work and ensures that even in disguise, each detective remains visible.

Indeed, in this way the stage detectives can sometimes be differentiated from those they seek whose disguises, by comparison, are often more subtle and understated. Though this is not always the case—Savage Mike’s French sailor costume is as absurd as Walker’s—we see this overtly in Handcuffs and The Mother’s Dying Child as well as in Sherlock Holmes. In Handcuffs, where there is the most obvious latitude for overlap between the detective hero of the piece and the corrupt officer he pursues, Burleigh’s costumes are patently obvious and even signalled to the audience, in direct contrast to the continued deception of his antagonist, Ingram/Holt:

BURLEIGH: She’d be in deadly danger with James Ingram but she’ll be safe enough with Ben Burleigh (removes disguise [of a cabman] so that audience see who he is). (Stockton and Hudson Citation1893: Act 3; 175)

Likewise, while Dalton of The Ticket-of-Leave Man subtly ‘lifts his hat’ to identify himself, Hawkshaw dramatically ‘pulls off his rough cap, wig, and whiskers, and speaks in his own voice’ to declaim that he is, in fact, ‘Hawkshaw’ (Taylor Citation1985 [1863]: Act 1; 167 and Act 4, Sc 1; 219). Similarly, while Moriarty, like Holmes, appears disguised in the final act of Sherlock Holmes, Moriarty never discards his cabman costume. By contrast, Holmes leisurely removes his Old Gentleman wig partway through the scene. In addition, Gillette (as playwright) pays little heed to the particular details of Moriarty’s disguise, giving no specifics in either the typescript or additional marginalia, quite unlike the approach taken for Holmes.

Significantly, this commitment to what we might call visible invisibility or going ‘undercover’ was not in fact restricted to such showy instances of performed disguise. Hawkshaw opens the play wearing no extravagant costume but he nevertheless evinces a commitment to a kind of conspicuous inconspicuousness.

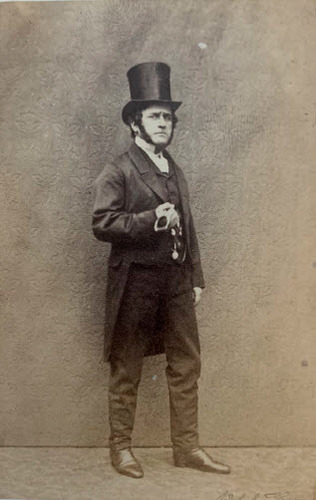

Fig. 3 Carte de visite of Horace Wigan as Detective Jack Hawkshaw (1863). Photo by Adolphe Beau, author's own collection

Amidst a bustling scene at the Bellevue Tea Gardens in which various patrons call for various combinations of ‘tea’, ‘shrimps’ and ‘muffins’, and a harassed waiter shuttles between tables, Hawkshaw enters in an intentionally casual mode:

(Enter HAWKSHAW. He strolls carelessly to the DETECTIVES’ table, then in an undertone and without looking at them—)

HAWKSHAW: Report.

1st DETECTIVE: (in same tone and without looking at

HAWKSHAW) All right.

HAWKSHAW: (same tone) Here’s old Moss. Keep an eye on him. (Strolls off) (Taylor Citation1985 [1863]: Act 1; 166)

Tom Taylor specifies that Hawkshaw ‘stroll’ on and off, moving with apparent ‘careless[ness]’. He, like his fellow detective, speaks in an undertone, with both men taking care not to look at each other. The stark contrast with the otherwise frenetic pace of the scene ensures that this performance of studied discretion would draw the eye of the audience. What is more, though none of the detectives are here mentioned by name, the clear directions issued and received by the men would ensure that an audience of 1863 would identify these unusual tea garden patrons as undercover officers of the police. As such, by the time that the act closes and Brierly mistakenly believes that he is being garrotted, the audience is well aware that he is in fact being arrested by the conspicuously inconspicuous detective, Hawkshaw. The insistent visibility of Hawkshaw might seem to be a theatrical necessity, a dramatic adaptation to force the ordinarily imperceptible detective branch into the limelight. The tales in Macmillan’s Magazine and All the Year Round as well as the decidedly dramatic photograph of the 1911 CID officers, however, suggests not. There was, it seems, a shared commitment to the appearance of conspicuous inconspicuousness.

In this, these officers appear to practice what Gary T. Marx has described as ‘deceptive and overt’ strategies of policing (1988: 11). In his foundational study, Undercover: Police surveillance in America, Marx helpfully divides different types of police work into four categories: ‘nondeceptive and overt’, ‘nondeceptive and covert’, ‘deceptive and overt’ and ‘deceptive and covert’. In other words, as he explains, ‘although covert and deceptive practices are often linked, just as overt and nondeceptive practices are, in principle they are independent’ and can therefore be combined in the ways cited above (11–12). While Marx sees ‘overt and deceptive’ police work as that in which officers trick suspects into confessions or deploy various deceptive tactics in order ‘to get around various legal restrictions’, the distinction he draws is useful (11). I suggest that the stagey and conspicuous practices deployed by these dramatic officers of the law (and some of their real-life counterparts) is a different type of such overt deception. They are quite conspicuously not practicing the seemingly more insidious form of undercover work that is at once deceptive and covert. Here, the overt nature of their deception serves to reassure the public that while they may be deploying deceptive practices they remain in some sense visible.

Nevertheless, the willingness of these detectives to go ‘undercover’—to throw on an elaborate disguise, assume a new accent and perform broadly as Irishmen, French sailors and drunken navvies—was a point of potential concern. It threatened to confirm long-standing anxieties that the new police system would imitate what many in England saw as the worst excesses of imperial France: an inclination to allow an overarching, overreaching body of government-sanctioned spies. What is more, the use of disguise and deception brought the new policemen into problematic alignment with those they pursued. If detective and criminal alike take on pretended identities to achieve their ends, one could be forgiven for asking just how distinct they really are. These anxieties were particularly acute in the mid–late nineteenth century when public discourse often circled back to the threat of fraud and concerns about deceptive practices— something Tom Taylor’s The Ticket-of-Leave Man certainly seems to acknowledge. The fact that these are stage detectives might, moreover, seem to justify levelling an additional charge of deception. In other words, these detective performances of disguise occur within a mode itself often charged with the perpetuation of deception and delusion. The melodramatic traditions of the period, however, did not tend to advance the subtle deception that underpins such a charge, but rather applauded virtuosic shows of performance skill. Operating in this environment, the stage detective and, indeed, his offstage counterpart as featured in contemporary periodicals, was able to evince a commitment to visible performance, even when that performance was one of inconspicuous nonchalance, thereby deflecting any charges of underhand undercover work. The detective was primed to remain visible even when—perhaps especially when— undercover. Whether or not the belief in such evident performances of inconspicuousness by detectives was justified, such a belief was certainly facilitated by the traditions of melodrama and the figure of the stage detective. Indeed, the visibility of the kind of theatrical deception practiced by these stage detectives implied the impossibility of the scandalous and ongoing deceptions practiced in recent years by undercover officers of the Met police who engaged in long-term relationships with women who were intentionally deceived as to the nature of their actual identities (Evans Citation2021). In this way, the show-stopping detectives of Victorian drama provided a useful foil to anyone anxious about the latent work of the force. They encouraged a convenient faith in the overt nature of such covert operations as their onstage ‘undercover’ work remained necessarily and reassuringly in air quotes—an overt performance of a covert tactic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The research for this article has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 843672.

Notes

1 While I cannot say with absolute certainty that the first image of the men in formal attire is not also an image of the men in ‘disguise’, it is highly improbable. Unlike the second image, the first does not highlight any obviously performative elements: there is no scene set, no obviously theatrical accoutrements and no facial obscurement. Formalwear, in and of itself, would not have been a particularly effective disguise. Moreover, while it is theoretically possible that the detectives intended to showcase their ability to infiltrate more polished affairs, it seems unlikely that the police, who were aware of the sort of sentiments expressed by the Earl of Dudley at their formation (see p. 79), would have been keen to advertise their ability to infiltrate the formal events of the typically more professional or upper-class worlds.

2 In accordance with the 1853 Penal Servitude Act, ‘felons due for transportation after penal servitude were permitted to remain in Britain and to live at large among society on a “ticket-of-leave.” The ticket was a card that the parolee was required to carry at all times and to present to the police for inspection at intervals specified by law’ (Mayer Citation1987: 35). Bob Brierly becomes one of these ‘ticket-of-leave’ men once he is released from Portland Prison in the latter part of the play. Ironically for Brierly, the ‘garrotting scare’ of 1862–3 caused many in Parliament to link these parolees with the recent spate of garrotings. The question of this scheme and the position of these parolees in society was one very much under discussion at the time of the play’s production (34).

REFERENCES

- ‘A French Detective Story’ (1877) All the Year Round: A weekly journal 19(469), 24 November.

- Booth, Michael (1965) English Melodrama, London: Herbert Jenkins.

- Clarkson, Charles Tempest and Richardson, J. Hall (1889) Police!, London: Field & Tuer, The Leadenhall Press E.C.

- Cook, James (2001) The Arts of Deception: Playing with fraud in the age of Barnum, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dell, Simon (2010) The Victorian Policeman, Oxford: Shire Publications.

- Evans, Rob (2021) ‘Judges criticise Met police after woman wins spy cops case’, The Guardian, https://bit.ly/3wiSLs0, 30 September, accessed 17 February 2022.

- Gillette, William Hooker (1899) Marginalia, Sherlock Holmes. Wherein is set forth for the first time the strange case of Alice Faulkner, Typescript with author’s ms corrections, Oversize (+), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Synthetic Collection, Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library, New York City.

- Gillette, William (1983) Sherlock Holmes, in Rosemary Cullen and Don B. Wilmeth (eds) Plays by William Hooker Gillette, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 192–272.

- Harding, James M. (2018) Performance, Transparency, and the Cultures of Surveillance, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Hazlewood, Colin Henry (1863) The Detective, or A Ticket-of-Leave’s Career: A drama of every day life, Manuscript Add MS 53024 A, Lord Chamberlain’s Collection, British Library, London.

- Hazlewood, Colin Henry (1864) The Mother’s Dying Child, or, Woman’s Fate, Manuscript Add MS 53034 N, Lord Chamberlain’s Collection, British Library, London.

- Lewes, George Henry (1958) ‘Charles Kean’, in On Actors and the Art of Acting, revised edn, New York, NY: Grove Press.

- Marx, Gary T. (1988) Undercover: Police surveillance in America, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Mayer, David (1987) ‘”The Ticket-of-Leave Man” in context’, Essays in Theatre 6(1): 31–40.

- Meason, M. Laing (1882) ‘The French detective police’, Macmillan’s Magazine, pp. 296–301, February.

- ‘Our biographies: Being brief sketches of the lives of managers, authors, actors, and actresses. No. LXI.—Mrs. Sara Lane’ (1882) The Stage, pp. 10–11, 1 December.

- Philips, David (1980) ‘”A new engine of power and authority”: The institutionalization of law enforcement in England 1780–1830’, in V. A. C. Gatrell, Bruce Lenman and Geoffrey Parker (eds) Crime and the Law: The social history of crime in Western Europe since 1500, London: Europa Publications Ltd.

- Scott, Clement William and Manuel, E. (1875) The Detective, Manuscript Add MS 53149 A-T, Lord Chamberlain’s Collection, British Library, London.

- Shpayer-Makov, Haia (2002) The Making of a Policeman: A social history of a labour force in metropolitan London, 1829–1914, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Stockton, E. and Hudson, E. V. (1893) Handcuffs, Manuscript Add MS 53525 L, Lord Chamberlain’s Collection, British Library, London.

- Taylor, Tom (1985 [1863]) The Ticket-of-Leave Man, in Martin Banham (ed.) Plays by Tom Taylor, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 164–222.

- Voskuil, Lynn (2002) ‘Feeling public: Sensation theater, commodity culture and the Victorian public sphere’, Victorian Studies 44(2): 245–74. doi: 10.2979/VIC.2002.44.2.245