Abstract

The advance of immersive and virtual technologies draws into starker contrast the analogue modalities of dominant approaches to actor training and makes more visible certain of their dynamics, which are analysed here using a philosophical framework of habit and habitus as propositionally causative. This technology is disruptive to habit and habitus in actor training and signifies potential to experiment with these dynamics to address extant problems in actor training.

Problems in training habitus discussed here derive from trainers’ habits but arise primarily for trainees, and especially so for certain groups. I use Lazlo Pearlman and Deirdre McLaughlin’s critique of the effects on LGBTQ+ trainees of Meisner Technique to exemplify this. I make three philosophically derived practical proposals to address the problems caused by trainers’ language-use habits that are germane to the Meisner Technique context but applicable to actor training, and training more generally.

This article does not propose an un-tested adoption of technology or prejudge its effects; it builds the philosophical case for experimenting now before this technology becomes ubiquitous in actor training and makes provocative proposals about future use-cases.

There is no sound philosophical basis on which to see habit in actor training as bad but when did that ever stop anyone. Frank Camilleri writes that, in theatre, ‘habitual patterns [of body use] are usually frowned on as conditioning movement and thus limiting the exploration of a range of other possibilities’ (2018: 37). This prejudice is widespread within twentieth-century European Laboratory theatre traditions of actor training that stipulate the ‘stripping away’ of layers of socialization and that valorize what is thought to reside underneath (Matthews 2014: 68). It is also apparent in the distain for social mores in the post-Stanislavskian traditions typified by Meisner Technique,Footnote1 which is now ‘a staple within western drama school training, professional development courses and masterclasses’ (Pearlman and McLaughlin 2020: 311). Habits, as Camilleri argues, are often seen as bad by actor trainers because they have been formed in the everyday and thus, the critique goes, they constrain movement, speech and behaviour within quotidian parameters thereby limiting and perhaps even inhibiting embodied experiences or representational possibilities. ‘Many teachers of acting’ therefore ‘attempt to reduce or neutralise’ (Camilleri 2018: 43) habits altogether.

In redress of prejudice, Camilleri makes the common-sense observation that ‘the tendency and potential for change and becoming that is contained within the repetition of exercises in training resonates with the fact that habits can be acquired, modified or dropped’ (2018: 39); particular habits are the problem because they give rise to particular unwanted effects. Camilleri notes the relational, situational and temporal qualities of habit in performer training, and conceives of these within a material ‘milieu’ of the training studio, where agency is ‘distributed and spread’ across assemblages and ‘patterns’ of human and non-human things (37, 38). Camilleri’s notion draws on John-David Dewsbury’s ‘ecological’ sense of habit. Dewsbury describes ‘in situ habits, cued by ecological surroundings and understood as inhabitations’ in an ‘understanding [of] the human to come into being out of habit ecologies’ (2012: 74–5, 81).

The sense in Camilleri and Dewsbury is of habits enmeshed within material patterns and relationships. Dewsbury considers the causative nature of ecologies, sub-textually recalling Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics juxtaposition of learning and habit with the human and the non-human. Aristotle comments on both teleology and causality by which the doing and the thing done are subordinate to its causeFootnote2. Germane to Camilleri’s and Dewsbury’s interest in the non-human elements of the ‘habit milieu’ is that, for Aristotle, the artisan is mostly irrelevant. According to Aristotle, a statue is not because of a sculptor; the sculptor manifests the specific knowledge required but this knowledge, not the artisan who has mastered it, is the efficient cause of the statue (Physics II 3, 195 b 21–25 (1983)). Accounting for causality, Marcel Mauss and Pierre Bourdieu have translated Aristotle’s ‘hexis’ not as ‘habit’ but ‘habitus’, denoting something more encompassing than an exclusively behavioural definition and thereby more akin to the habit ‘milieu’ or ‘ecology’ in Camilleri and Dewsbury.

Definitive contrasts between habit and habitus are impossible (Crossley 2013: 136) but Bourdieu and Mauss preserve a distinction to differentiate between repeating human behavioural elements and the larger context in which these elements are isolatable. For Mauss (1979), ‘habitus’ is an acquired ability – from hexis as having. Acquisition is central to Mauss’s concept of ‘body techniques’ and is recapitulated in Camilleri’s common-sense observation about the changeability of habit. Mauss makes a finer distinction still: habit suggests what Nick Crossley calls ‘individual variation, whereas habitus, without precluding individual-level variation, suggests variation between social groups’: ‘we all have individual habits but habitus are social facts’ (2013: 137). Habitus belongs to the ‘collective repertoire of practical reason within a particular group’ (138), relevant to the studio milieu or ecology.

According to Crossley, the ‘key point’ about the distinction in the Aristotelean tradition is that habitus defines ‘actors in different social communities acquiring from those communities the dispositions and skills constitutive of practical reason’ (141). Or, as Bourdieu has it, habitus are ‘structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures’ (1992: 53). Camilleri is sceptical about the possibility of describing habit ‘on its own’ but argues that ‘rather than distinguishing features that belong to form’, habits may be identifiable as ‘dynamics or forces’ whose ‘spatio-temporal context’ ‘allude’ to ‘the “milieu” of habits’ (2018: 37).

Semantically, I follow Mauss and Bourdieu and opt for the terms ‘habit’ and ‘habitus’ to distinguish philosophically between individuallevel repeatable, reproduced, reproducible and transmissible behaviour (habit) and the relational, spatial, temporal and material ‘structuring structures’ (habitus) that coordinate, motivate, determine and envelope the reproduction of behaviour. In my reading of Camilleri and Dewsbury, training ‘milieu’ or ‘ecologies’ are akin to this definition of habitus but with a significant ‘environmental’ orientation. Milieu denotes spatiality (from lieu meaning place) and, in common usage, connotes an environmental concept derived principally from physicality and sociality (rather than nature, as such). Dewsbury’s ‘ecology’ foregrounds contemporary discourses in a semantics of nature and climate explicitly, denoting an appreciation of human behaviour in a context inclusive not only of things but of nonhuman agency.

Camilleri’s and Dewsbury’s use of language might be read in context of the turn to nature in Western philosophy following Watsuji’s Climate and Culture (1961), and other influential works on this theme in the late twentieth century. Influenced by Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit (Being and Time, 1927), Watsuji’s Fūdo (Fūdo ningengakuteki kōsatsu; translated as Climate and Culture) critiques Heidegger’s under-emphasis on spatiality and over-emphasis on temporality. Watsuji asserted that if Being and Time has been a proper double-bill, and had Heidegger equally emphasized spatiality and not over-emphasized temporality, his ideas would have been secured in a human realm of interactions thereby ethicizing his philosophy by embedding it within the ‘real world’ of interconnected material relations dominating social interactions.

According to Marcella Horrigan-Kelly et al. (2016), Being and Time contradicts Descartes’ characterization of human beings as spectators of objects and asserts the inseparability of subject and object. Watsuji uses fūdo, which means ‘wind and earth … the natural environment of a given land’ (Watsuji 1988 [1961]: 1) to connote the co-embeddedness of spatial, environmental, and collective aspects of human existence (Berque 1994: 498). In Watsuji’s influential philosophical interjection, humans are ineluctably environed by nature – topography, geology, humidity, weather, fauna, flora, atmosphere, ocean and so forth – in ways that give rise to living and also to interdependent artefacts – clothing, cuisine, built environments and so on.

The philosophy of Mauss and Bourdieu can also be situated within this phase-shift in Western philosophy. However, their term to describe the environmentality of behaviour – habitus – denotes agency and activity, deemphasizing the passivity of that which is given (by nature) and emphasizing that which is taken (by humans). ‘Habitus’ and ‘ecology’ both derive from Proto-Indo-European roots: ‘ecology’ from weik, meaning ‘household’ as a social group or simply ‘house’, as a location as in the Greek oikos, and ‘habitus’ from ghabh, meaning to grab or to take by force, leading to the Latin verb habēre, to have, hold, possess. Like Mauss and Bourdieu, I wish to draw attention to the causative nature of habit and habitus and the extent to which they are each shaped by individual and collective willing, and not driven by natural processes. They each work on nature and things and not for or with them, even if the outcomes of these processes may have positive or negative effects with regards nature. This is because these processes are not initiated or instructed by nature or guided by its intentions or desires (if nature can be said to have these), or the objectives of any non-human agents or things though, as Watsuji’s explains, they will be environed by these.

I choose this language – habit and habitus – to enable me to theorize training against the drift of contemporary discourse as that philosophical category of activity that is distinctly human and uniquely capable of subordinating non-human things to human purpose (see Matthews 2021 [2019]). In my theorization of training, habit and habitus are not passive processes but definitively causative and teleological as well as arising because of human agency. Habit, as a descriptor for units of human behaviour, and habitus, as a descriptor of a causative envelope of human and non-human relations, can be used to frame an understanding of how intention connects with effect in training. Framing this understanding requires an appreciation of habitus not as a given environmental context but an activity in which human beings and things are impelled by agentic force – plunged into (immersio) and driven under and within.

IMMERSION

The metaphor of immersion is commonly used to define habitus: the individual being within habitus, enveloped and bounded by it and an indivisible and sustaining part of it, like ‘a fish in water’ (DeLuca 2016; Çakmak et al. 2021). This understanding is tacit in actor training discourses and practices and reified in Grotowski’s and post-Grotowskian paratheatrical training experiments and traditions. Deborah Middleton and Nicolás Núñez, for example, have continued to assert the transformational potential of immersive experiences in nature, arguing in favour of nature-based training exercises bringing about a ‘“deconditioning of perception” in order that we [performers] are able to receive sensory inputs in a more immediate, and less mediated manner’ (2018: 220).

Jamie DeLuca (2016) uses a water-immersion metaphor for habitus in the literal context of swim club membership in a study of becoming ‘like a “fish in water”’. Similarly, Loïc Wacquant, in a commentary on ‘becoming a prize-fighter’ in ‘the black American ghetto’, writes about how, methodologically, habitus posits ‘deep immersion in, and carnal entanglement with, the object of ethnographic inquiry’ (2011: 81). The meaning of habitus is built on a metaphorical understanding that it is something we are spatiotemporally within. However, philosophically, the immersion metaphor may not even be metaphorical. In Bourdieu, habitus is ‘a subjective but not individual system of internalised structures, schemes of perception, conception, and action common to all members of the same group or class’ (1977: 86). These ‘internalised structures’ and ‘schemes of perception’ organize the subject’s (shared) worldview and their ‘apperception’ of the (physical and non-physical) world in which they suppose they exist (ibid.). The dichotomy between what is outside of the self (the world in which they suppose they exist) and what is inside of the self (internalized structures) in habitus are co-constitutive; they are differentiable but, to recall the metaphor, held apart only by an intervening surface tension.

The extent to which immersive experiences in training give rise to ethical or desirable outcomes is moot but the efficacy of habitus in bringing about transformational outcomes in capability and identity in training is evident (see Matthews 2009: 103–12). In line with the inside/outside dynamic of habitus and the immersion ‘metaphor’, David Shearing has commented on a ‘danger in the discourse’ on immersion in audience theory and event design: ‘Immersion is not’, he writes, ‘an external experience given to someone. It is an internal state, built through an individual’s sustained relational encounters with the world’ (2018: 291). This understanding of what it means or feels to be immersed is well established in actor training such as Middleton and Núñez’s. Here, trainees ‘become more attuned to arising visual sense perceptions, and more receptive to direct experience’ by practising a ‘non-habitual mode of seeing’ predicated on ‘360 degree vision’ (220). Middleton and Núñez assert that a ‘heightening of sensory experience is associated with an enhanced relationship to the surrounding environment’ (227) and that this is encompassed within and because of a 360-immersion built, as Shearing would have it, through an individual’s sustained relational encounters with the world.

THE PROBLEM: APPLYING THE CAUSATIVE THEORY OF HABITSIN CONTEXT

The prejudice against habits in actor training is more artistic than moral but habits might be ‘bad’ when their effects are bad. Lazlo Pearlman and Deidre McLaughlin give a description of bad-habit-effects in Meisner Technique actor training, where two participants – Matt and Clara – are forced to behave in ways that make them both uncomfortable. During improvisation, Matt is instructed by the trainer to kiss Clara. ‘Watching Matt move closer to Clara, we observe her locked in a visible struggle as to whether or not she wanted him to kiss her or had to let him [sic]’: ‘We are left with the impression that Matt no longer had any choice but to head in for the kiss, and Clara had no real agency to stop him’ (2020: 313). The exercise ‘ended in an awkward near miss’ (313) and Pearlman and McLaughlin conclude that the instruction to ‘a male student to kiss a female student “if he wanted to” brought normative notions of masculine and feminine behaviour and heteronormative gender and sexuality to bear in the name of “following your instincts”’ (311). The ‘problem with this instruction was clear: neither student had been given the tools or opportunity to follow any but the culturally trained “instinct” to kiss (male) and be kissed (female)’ (ibid.). They describe this teacher as directing participants using ‘prescriptive and limiting’ (314) instructions and assert that the participants felt powerless to disregard these.

For Pearlman and McLaughlin, this isolated incident is illustrative of a broader ‘bad’ effect – widespread oppressive cis-normative culture in actor training. It is also illustrative of an even broader bad effect – the potential for trainers’ habits to negatively affect trainees, which extends beyond the potential for all humans to negatively affect one another because of the over-determining effect of trainers on trainees tout court.

The socio-cultural problem of cis-gendernormativity, according to Pearlman and McLaughlin, crystalizes in the ‘instruction’ that the teacher gave and is reified in the difficulty faced by a participant seeking to ‘take on and feel the instruction not as a favoured “mode of being”’ (2020: 315). They suggest that the propensity of teachers to facilitate Meisner Technique exercises in the format of a ‘scene’ derives character and narrative via normative assumptions and modes, and that this impels teachers to formulate instructional language accordingly in such a context.

A LANGUAGE PROBLEM

Spoken language is a principal modality for facilitating trainingFootnote3. Meisner Technique exercises are structured on the trope of the conversationFootnote4, and this foregrounds spoken language as the primary-ground for meaningmaking and interpreting. This can equally be seen to promote conventions and connotations of normative socio-cultural interactions limiting the much-valorized capacity in acting training to bring about anti-normative thinking and action.

The expression, assertion and embedment through language of normative conventions and connotations might be influenced by the time-pressure that Meisner Technique training exercises place, by design, on the use of language by trainers and participants. The repetition exerciseFootnote5, for example, intentionally pressurizes participants to formulate observations into speech quickly, requiring very high-level language skills and processing speeds. Irrespective of accessibility barriers related to this requirement, the pressure thus caused may also augur retrenchment of cultural and narrative norms in unfolding exercises. In Pearlman and McLaughlin’s illustrative example, it is when the exercise is misfiring and a male participant is ‘struggling with letting go of any previous idea he had of “improvising a scene”’ (2020: 313) that the trainer ‘urgently’ ‘stepped in’ to give an instruction (ibid.), which purportedly imposed regularizing narrative shape upon the unfolding action. The pressure to interpret inchoate action and give it meaning in the facilitation of an ostensibly edifying training exercise might drive trainers towards familiar patterns and interpretations of meaning. The time-pressure possibly constricts the ability to express novel insights requiring novel language formations, and this pressure could favour and embed trainers’ habitual ‘talk moves’.

Conceptualizing training experiences as primarily teleological, Sarah Michaels and Catherine O’Connor argue that ‘talk moves’ are linguistic ‘tools’, ‘conversational moves used to accomplish local goals’ (2013: 334). Claire Syler has used discourse analysis in actor ‘coaching’ ethnographies to identify species of ‘talk moves’, classifying these as ‘reflections’, ‘rules’, 'recounts', 'eventcasts' and ‘technical directives’ (Syler 2017). Each species represents a language format used by coaches to impute value to student conduct, behaviour, actions and abilities. Syler describes teachers’ ‘talk moves’ as ‘epistemic tools’ that organize coaching ‘by extending participatory pathways to mediate performance learning’ (2017: 317) and, as such, they are highly determinant in student understanding.

INVERTING THE PROBLEM: ASSESSING PHILOSOPHICALLY THE PROSPECT OF HABITS AND HABITUS CAUSING GOOD EFFECTS IN ACTOR TRAINING

Dichotomous with their critique of trainers, Pearlman and McLaughlin proclaim antinormative potential latent within Meisner Technique. They contrast Elizabeth Freeman’s concept of ‘heteronormative time’ and ‘chrononormativity’ with Jack Halberstam, E. L. McCallum and Mikko Tuhkanen’s ‘Queer Time’ in an analysis of the potential of Meisner Technique to organize representations of identities and participants’ subjectivities. Freeman’s definition of chrononormativity as a ‘use of time to organize individual human bodies toward maximum productivity’ posits a ‘“Kronos”, a “linear time”’ (2010: 23) in and by which the Capitalist imperative of productivity induces normativity. Freeman’s ‘chrononormative’ describes the curation of time within spatial materiality (2010: 3) whereby ‘time can be money only when it is turned into space, quantity and/or measure’ (54). Chrononormativity is concerned with ‘time rather than just space’ (126, emphasis added) and not time outside of space or without it. ‘Queer Time’ denotes ‘specific models of temporality that emerge within post-modernism once one leaves the temporal frames of bourgeois reproduction and family, longevity, risk/safety, and inheritance’ (Halberstam 2005: 6). It might also be understood as a sense of time ‘manifest as lived experiments with ways of life, forms of identity, cultural activities, and modes of existence that upset the smooth flow of reproductive straight time’ (Farrier 2015: 1,401).

Pearlman and McLaughlin contend that Meisner Technique possesses inherent potential to facilitate Queer Time, supporting Queer actions and subjectivities. They argue it is ideologically committed to an interpersonal free-play of feeling and representation unbounded by normative temporal codes and modes. Pearlman and McLaughlin associate Queer Time with the potential to cause ‘normative logics of time and conversational dialogue [to] disappear’, allowing time to ‘stretch’ and ‘shrink’ and, with it, ‘“narrative coherence”’ (2020: 316). They give a sense of a rarefied space-time that resonates with Dewsbury’s account of an unfolding of manifold ‘affordances’ enabling ‘the human to come into being’ (2012: 81) differently; they hold out the promise of enabling participants to act outside of socio-cultural constraints and assert that so doing will have specific benefits for ‘LGBTQ+ and other marginalized student groups’ (Pearlman and McLaughlin 2020: 310) as well as benefits for any student participating in actor training. Furthermore, they argue that Meisner Technique exercises can be facilitated in ways such that participants are ‘free not to follow hegemonic cultural behaviour patterns’ (ibid.). They argue that a ‘freewheeling Meisner session’, where students are able to ‘“live truthfully” (and potentially “queerly”) under a myriad of “imaginary circumstances” in a 10–30-minute exercise’ (317) is not only a possible outcome but a desired one.

In this context, it should be noted that in mid- to late-twentieth-century European actor training, theorization was dogged by Neo- Rousseauian fantasies of a ‘pre-expressive’ state of being, and the possibility of excavating prelapsarian human potential from beneath the accretions of culture (Matthews 2011: 40–66, 194–6). However, the notion of ‘free-play’ or perhaps ‘less-un-free-play’ has remained central to many actor training practices (Matthews 2014: 112).

Whether or not free-play is conceptually or practically possible in actor training or the Meisner Technique exercises, training nonetheless confers on trainers specific responsibility (and authority) to determine the boundaries within which actions and speech are formulated, cultivated, interpreted and valorized. The imperative to facilitate training exercises better – that is, more inclusively and less repressively – is non-contentious even if the prospect of practising free from cultural baggage altogether might be.

Perhaps the ideal conditions in which Meisner Technique exercises can be practised in the real world are not those of complete free-play but of less-un-free-play. Not a socio-culturally unbounded habitus but a differently bounded one. Or simply, less over-determined by the talk move habits of teachers. Achieving this aim – if it can be achieved – will evidently involve using language in very certain ways that, as Pearlman and McLaughlin indicate, will have very certain causative effects.

Identifying language-use that would not have normative, normalizing or repressive effects represents a distinct challenge. Enabling teachers to employ such language represents a second challenge because, as Syler’s work makes clear, teachers are seldom fully conscious of their ‘talk moves’ or the values they inculcate:

Whereas [an] acting instructor described his coaching practice as unrehearsed and extemporaneous, discourse analysis revealed repeated talk moves embedded in his coaching of which the instructor was unaware. (Syler 2017: 317)

PRACTICAL PROPOSALS IN RESPONSE TO THE PROBLEM

Proposing the possibility of Queer Time in Meisner Technique is a habitus proposition. The difficulty that Pearlman and McLaughlin find in conceiving of specific practical measures that will bring about ‘good’ language-use habits is, arguably, because ethical intentions do not reliably lead to ethical actions. Their appeal to trainers to begin ‘confronting’ their own ‘conditioning’ and ‘dismantling it’ is, ironically, a sometimes-explicit and often-illusory intention of many twentieth-century actor training methodologies and approaches, including Meisner Technique (Matthews 2011: 198–200; 2009: 108–10). Ethical training practice – trainers’ good habits causing good effects and/or not causing bad ones – brings with it all the challenges of ethical practice tout court, including defining ‘good’ and ‘bad’ effects (both ethically and artistically).

If trainers will facilitate exercises through habitual talk moves derived from the position of their own ‘enculturation or experience’ (Pearlman and McLaughlin 2020: 310), then one of the primary barriers to good language-use habits is the discrete fact of trainers. Given the specific status of spoken language in Meisner Technique, this practice may be especially exposed to an over-determining effect caused by trainers’ talk moves, particularly in conjunction with the ‘guru’ status of teachers in this tradition (Hornby 2007; Malague 2012: 1–2). However, it is evident logically that although the effects of talk move habits on habitus in Meisner Technique training may have specific characteristics, they can be understood in a general context of training (and not just actor training) (Matthews 2016: 91–2).

Muting or doing away with trainers altogether might address the problems under discussion. Such pragmatic solutions ascribe a new and obvious set of ethical and artistic problems that scarcely require discussion. Yet, following the logic of that drastic suggestion, the problems of trainers’ habits might be addressed by reducing the opportunities for trainers to talk as a means of facilitating exercises. Or, by reducing the total number of talk moves required of trainers to facilitate effectively. Or, by sublimating ‘talk’ into another non-verbal means of communication and perhaps even by doing all of this in conjunction with removing trainers physically from the material work-space of the studio while still retaining their wanted influence within its habitus.

It might be ‘good’, then, to:

reduce language-based instruction in exercise facilitation

decentralize the conspicuous authority of the teacher in facilitating exercises

promote an interstitial habitus capable of sustaining diverse relational encounters during training exercises

In the broad context of actor training, there is nothing especially radical in these proposals. In the more specific context of Meisner Technique and the associated traditions of actor training gurus and charismatic teachers, they may be more radical. However, in the context of training today, they may elicit a radical response with consequences yet unknown because of the indication that they give towards the capabilities of new technologies.

NEW TECHNOLOGY NEW PROBLEMS

The habitus immersion metaphor is a touchstone to new technologies of immersion, which raises questions about the potential of this technology to effect training habitus. Immersive technology describes several things, including virtual and augmented reality headsets as well as larger, usually dome-shaped, projection spaces, all of which generate a sensorial effect of being within a computer-generated or affected reality. Control of these realities – or ‘models’ from the 3D modelling underpinning them – is usually referred to as ‘driving’ or ‘piloting’, and these various technologies can be self-piloted, piloted remotely (by someone else not within the immersive reality) or autonomously piloted by computers using artificial intelligence (AI).

The capacity of immersive technology to formulate and sustain habitus can be seen to derive from its perception-encompassing experience generation and not necessarily from its ability to produce photorealistic or authentic-seeming perceptual experience as such. Such capability offers a wholesale interruption to and within habitus by a comprehensive reformulation of many of its material dynamics. It thereby offers both an exemplification of habitus and a flexible technical means of experimenting with it.

Actor training exercises, such as Meisner Technique, can be practised with and within immersive technology, such as 360-degree immersive domes. This was the focus of Watercourse: Actor training and immersive virtual production, a Story-Futures-funded research project I delivered with co-investigators Andrew Prior, Musaab Garghouti, Joel Hodges and Lauren Hayhurst. Watercourse set out to make exploratory technical experiments with immersive and virtual production technology in Europe’s largest 360-degree dome; to explore what is technically possible and to scope the potential for further experimentation of the effects – good and bad – of what technical possibility has wrought.

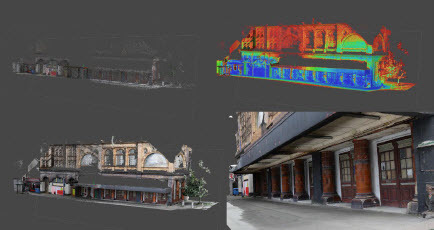

Watercourse noticed that the materiality of immersive technology in training habitus opens novel possibilities for sublimating trainers’ talk moves into non-verbal modalities that might help to address some ‘bad’ habits. Exercises, such as those practised by Matt and Clara, can be facilitated by non-verbal interjections. These interjections might be made with ‘assets’, that is, pre-programmed modular changes or additions to the model that appear in the reality experienced by a participant. In place of the instruction (for example, ‘if you want to kiss her then kiss her!’), a new image could appear in the model, or a lighting or sound change, or the appearance of a symbol. These changes could have pre-agreed meaning or, perhaps more radically, they could have no pre-agreed meaning and could serve only as provocations to be interpreted by participants, in place of literal instructions to them ().

Figure 1a. Photogrammetric 3D modelling of Plymouth’s Union Street showing sparse point cloud, dense point cloud, point cloud confidence, 3D model (Musaab Garghouti).

Figure 1c. 3D model running in flat screen test space (House Theatre) and in Devonport Market Hall Dome.

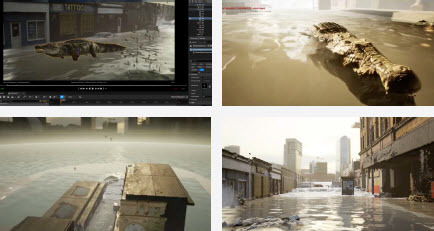

Figure 2. Pilotable digital assets including a tidal wave, a flock of birds and a crocodile (Musaab Garghouti).

The 3D models being used in actor training might be photorealistic, enveloping participants in authentic-seeming virtual realities or they could be diagrammatic. Assets deployed to facilitate exercises could be changes or additions to photorealistic virtual realities that would have strong perceptual effects on participants, or they could be diagrammatic signs and figures appearing in virtual space prompting participants to respond in more critical and less emphatic ways. In Watercourse, we made photogrammetric models and drove these in Unreal game engine, making exploratory technical experiments with photorealism and diagrammatics to test the current technical capabilities and limitations of these approaches. These capabilities represent new possibilities in actor training exercise facilitation, as well as the option of replacing some bad language habits with new non-linguistic materialities, with yet to be determined ethical and artistic effects.

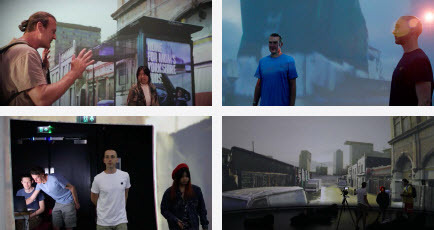

The piloting of assets can be done remotely, meaning that trainers can deploy and drive nonlinguistic prompts from outside of the immersive reality occupied by trainees. This may reduce the influence of the trainer as a determining factor in habitus in ethically ‘good’ ways by making their authority less conspicuous. It does not reduce their authority but makes it less present in the physical work-space and thereby potentially less determinant in the structuring of training habitus ().

Figure 3. John Matthews facilitating Meisner Technique actor training exercises with actors Clive Rowe and Zoe Maramba in Devonport Market Hall Dome. Andrew Prior and Musaab Garghouti at the remote control piloting station.

Remote piloting of non-verbal assets in actor training in immersive spaces represents a novel modality of exercise facilitation but, of course, not an ethically neutral one in the context of habitus. Immersive technology and associated digital assets will remain subject to human agency and its reproduced and reproductive behavioural structures and structurations. This technology enables a novel form of non-verbal and physically remote facilitation that allows testing and comparative analysis with orthodox, charismatic-teacher-centric approaches. Considering the fraught history of the teacher’s persona in actor training and the unconscious nature of their talk moves it would be fruitful to explore the potential for alternative modes of facilitation to inculcate progressive values, such as inclusivity.

The technical feasibility of generating and piloting digital assets in immersive spaces using AI opens additional lines of practical enquiry into my theoretical assertion that training is definitively human (Matthews 2014). In immersive domes, space can be mapped to create ‘trigger’ zones within it. When participants move into these zones, assets or asset sequences are deployed automatically. Trainers could design assets and maps and then allow these to be algorithmically evolved using machine learning AI; trigger points and asset sequences can be iteratively remapped and the assets modified by a data-analytics-driven algorithm ().

Figure 4. HTC Vive tracking experiments in the House Theatre. Tracking by Joel Hodges. Camera operator Tom Fitzgibbon.

Machine learning AI involves ‘training’ computer models on expanding databases of information, and assigning decision-making functions to the AI. The language of ‘training’ in machine learning is partly syntaxial coincidence, or metaphor: Jafar Alzubi, Anand Nayyar and Akshi Kumar contend that, in ‘machine learning [a subset of AI], each interaction, each action performed, becomes something the system can learn and use as experience for the next time’ and this is ‘the data analytics method which enables computers to learn and do what comes naturally to humans, i.e. learn from experience’ (2018). The data analytics method, though, is a highly limited systematized computational schema for only part of the habit acquisition and modification process noted by Camilleri (2018: 39), at least for now, anyway.

AI is not human but neither is it not-nothuman, and so utilizing AI to sublimate unwanted human values or actions in training is not straightforward. The United States’ government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 1270, ‘Towards a Standard for Identifying and Managing Bias in Artificial Intelligence’ (2022) records the widespread realization that AI algorithms and the data used to train them are innately biased. NIST’s principal investigator Reva Schwartz complexifies the picture further, noting that, in addition to innate biases, the societal contexts in which AI systems are deployed further biases algorithms and their outcomes. The report observes that human, systemic and computational biases are endemic within AI and that a combined ‘social-technical’ approach would be required to mitigate these.

The new modalities of actor training scoped in Watercourse bring with them all the associated problems of teachers, or rather, of humans precisely because of the definitively human nature of training as well as of products such as AI software. Rather than a moral corrective to extant training practice, immersive technology and AI might be a productively disruptive influence on firmly sedimented training habitus. Their disruptive potential allows for both comparative analysis of extant practices and practical experimentations with alternative approaches. In their novelty and disruptive nature, new technologies may inhibit habitual engagement in exercises by trainees and trainers, disrupting participants’ expectations and providing a ‘for the first time’ experience, which may be highly desirable in the context of the anti-everyday-habit prejudice in performer training.

The disruptive potential of new technologies is a factor of their newness, which will erode as these technologies become more embedded in actor training, as they inevitably will become in all human life. AI can, and no doubt will, become invisible in training habitus much as talk moves have. This observation gives impetus to experiments with this technology now, in its comparatively nascent stages of technical development and application. Such experiments in new technologically augmented approaches to actor training may give rise to outcomes that are ethically or artistically better or worse than extant ones.

Addressing habit in actor training discourse as a behavioural category deemphasizes its propositionally causative nature. Analysing habits, as I have here, via an understanding of habitus reemphasizes causality, setting a stage on which we are better able to prize apart and apprehend the relationship between cause and effect in habit. Holding these two apart can be instructive and is potentially corrective to actor training practice as well as being significant in a broader understanding and theorization of training as a philosophical category.

Notes

1 Meisner Technique is well-established in American actor-training programmes and has ‘significant impact in the UK’ (Shirley 2010: 200).

2 In the Posterior Analytics, Aristotle states that we have knowledge of a thing only when we have grasped its cause (I 2, 71 b 9–11 & II 11, 94 a 20). That proper knowledge is knowledge of the cause is repeated in the Physics: we think we do not have knowledge of a thing until we have grasped its why, that is to say, its cause (Physics II 3, 194 b 17–20). See Aristotle (1983).

3 See Matthews (2014: 77–108) for discussion of language use and affects in training, and Matthews (2011: 67–103) for philosophical discussion of the status of language in the meta-disciplinary training process of vocation.

4 See Shirley (2010).

5 For description of this exercise, see Shirley (2010).

REFERENCES

- Alzubi, Jafar, Nayyar, Anand and Kumar, Akshi (2018) ‘Machine learning from theory to algorithms: An overview’, Journal of Physics 1,142: 012012.

- Aristotle (1983), Aristotle’s Physics Books III and IV, trans. and notes Edward Hussey, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berque, Augustin (1994) ‘Milieu et logique du lieu chez Watsuji’ (Environment and the logic of place in Watsuji), Revue Philosophique de Louvain 92(4): 495–507. doi: 10.2143/RPL.92.4.556273

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice, Vol. 16, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1992) The Logic of Practice, Cambridge: Polity.

- Çakmak, Erdinç Lie, Rico, Selwyn, Tom and Leeuwis, Cees (2021) ‘Like a fish in water: Habitus adaptation mechanisms of informal tourism entrepreneurs in Thailand’, Annals of Tourism Research 90(1): 103262. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103262

- Camilleri, Frank (2018) ‘On habit and performer training’, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 9(1): 36– 52. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2017.1390494

- Crossley, Nick (2013) ‘Habit and habitus’, Body & Society 19(2–3): 136–61. doi: 10.1177/1357034X12472543

- DeLuca, Jamie (2016) ‘Like a “fish in water”: Swim club membership and the construction of the upper-middleclass family habitus’, Leisure Studies 35(3): 259–77. doi: 10.1080/02614367.2014.962581

- Dewsbury, John-David (2012) ‘Affective habit ecologies: Material dispositions and immanent inhabitations’, Performance Research 17(4): 74–82. doi: 10.1080/13528165.2012.712263

- Farrier, Stephen (2015) ‘Playing with time: Gay intergenerational performance work and the productive possibilities of queer temporalities’, Journal of Homosexuality 62(10): 1, 398–418. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1061361

- Freeman, Elizabeth (2010) Time Binds: Queer temporalities, queer histories, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Halberstam, Judith (2005) In a Queer Time and Place, New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Heidegger, Martin (1962 [1927) Being and Time, trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, London: SCM Press.

- Hornby, Richard (2007) ‘Feeding the system: The paradox of the charismatic acting teacher’, New Theatre Quarterly 23(1): 67–72. doi: 10.1017/S0266464X06000649

- Horrigan-Kelly, Marcella, Millar, Michelle and Dowling, Maura (2016) ‘Understanding the key tenets of Heidegger’s philosophy for interpretive phenomenological research’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods (January–December): 1–8.

- Malague, Rosemany (2012) An Actress Prepares: Women and ‘the method‘, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Matthews, John (2009) ‘Acting freely’, Performance Research 14(2): 103–12. doi: 10.1080/13528160903319620

- Matthews, John (2011) Training for Performance, London: Bloomsbury.

- Matthews, John (2014) Anatomy of Performance Training, London: Bloomsbury.

- Matthews, John (2021 [2019]) The Life of Training, London: Bloomsbury.

- Mauss, Marcel (1979) ‘Techniques of the body’, in Marcel Mauss, trans. B Brewster Sociology and Psychology: Essays, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Michaels, Sarah and O’Connor, Catherine (2013) ‘Conceptualizing talk moves as tools: Professional development approaches for academically productive discussion’, in Lauren Resnick, Crista Asterhan and Sherise Clarke (eds) Socializing Intelligence through Talk and Dialogue, Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association, pp. 333-47

- Middleton, Deborah and Núñez, Nicolás (2018) ‘Immersive awareness’, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 9(2): 217–33. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2018.1462252

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (2022) Special Publication 1270, ‘Towards a standard for identifying and managing bias in artificial intelligence’, https://bit.ly/3wlCdU5, accessed 20 February 2024.

- Pearlman, Lazlo and McLaughlin, Deirdre (2020) ‘If you want to kiss her, kiss her! Gender and queer time in modern Meisner training’, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 11(3): 310–23. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2020.1789723

- Shearing, David (2018) ‘Training … immersion and participation’, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 9(2): 291–3. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2018.1475903

- Shirley, David (2010) ‘”The reality of doing”: Meisner Technique and British actor training’, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 1(2): 199–213. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2010.505005

- Syler, Claire (2017) ‘Conceptualising actor coaching: Talk moves as tools’, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 8(3): 317–28. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2017.1323002

- Wacquant, Loïc (2011) ‘Habitus as topic and tool: Reflections on becoming a prizefighter’, Qualitative Research in Psychology 8(1): 81–92. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2010.544176

- Watsuji, T. (1988 [1961]), Climate and Culture: A Philosophical Study, Geoffrey Bownas (trans.), New York: Greenwood Press; revised and reprinted from A Climate: A Philosophical Study, Geoffrey Bownas (trans.), Tokyo: Ministry of education and Hokuseido Press, 1961.