ABSTRACT

Teachers’ knowledge has been an important research focus for many decades. Although many empirical studies have been carried out regarding content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge, less attention has been paid to general pedagogical knowledge (GPK). The focus of this study is the exploration of different definitions and dimensions of GPK and how it has been assessed. A systematic literature review was conducted on the EBSCOhost Web following the PRISMA guidelines. The search and evaluation of eligibility criteria resulted in 23 articles. The results show that the definitions of GPK cover three broad areas: student-related, teaching-related and contextual characteristics. However, the scope of GPK in the empirical studies is more narrow, focusing mainly on student-related and teaching-related dimensions. The results also showed that GPK has been assessed through teachers’ own perceptions and, recently, by measuring it with tests. These findings are further discussed and a framework for analysing, developing and assessing teachers’ GPK in further studies is proposed.

Introduction

Questions about what a teacher should know have concerned educationalists since the early days of formal schooling (Gutek, Citation2011). The 1980s saw a new boost in attention to the knowledge base of the teaching profession in the Anglo-Saxon world, initiated by Shulman (Citation1986, Citation1987). Shulman (Citation1987) argued that the contemporary psychology-based research tradition on teaching is one-sidedly oriented towards teachers’ behavioural aspects, but neglects important questions about the subject matter and content of instruction. Shulman called for a comprehensive and balanced organisation of teachers’ knowledge base. He proposed a list of knowledge categories that included: (a) content knowledge, (b) general pedagogical knowledge, (c) curriculum knowledge, (d) pedagogical content knowledge, (e) knowledge of learners and their characteristics, (f) knowledge of educational contexts, and (g) knowledge of educational ends, purposes and values (Shulman, Citation1987).

Shulman (ibid) noted that although his categorisation required further specification, he did not aim to elucidate it thoroughly in his paper. Indeed, although Shulman’s proposal has been highly influential in general, the degree to which the different categories have attracted further research varies considerably. Drawing on Shulman, many authors have highlighted what they see as the three ‘core’ categories in Shulman’s classification: content knowledge (CK; knowledge of the subject), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK; knowledge about teaching and learning a specific subject) and general pedagogical knowledge (GPK; knowledge not specific to a certain subject; Baumert et al., Citation2010; König et al., Citation2016; Merk et al., Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2018). Of these three categories, CK dominated the study of teachers’ knowledge for many centuries (Shulman, Citation1986), whereas PCK has by far received the greatest attention during the years since Shulman’s proposal (Kansanen, Citation2009; Ulferts, Citation2019). There is a large body of empirical studies conducted on CK and PCK (e.g., Anderson & Clark, Citation2012; Ball et al., Citation2008; Hashweh, Citation2005). What several authors have observed as lacking sufficient attention is research on general pedagogical principles or, in Shulman’s terms, GPK (Atjonen et al., Citation2011; Buchberger & Buchberger, Citation1999; Depaepe et al., Citation2020; König et al., Citation2016). Such inattention has led to the risk of narrowing the issues actually related to GPK down to the subject-specific, i.e. PCK, level. Shulman (Citation1987) defined GPK as ‘ … knowledge, with special reference to those broad principles and strategies of classroom management and organization that appear to transcend subject matter.’ Seen this way, GPK also has, albeit at a different level, a content of its own, which is not to be confused with or narrowed down to PCK. The risks of an imbalanced focus on the subject-specific are clearly described by Buchberger and Buchberger (Citation1999), keeping in mind that several authors (Depaepe et al., Citation2013; Kansanen, Citation2009) have referred to essential parallels between Shulman’s ‘core’ categories and the German-originated concepts of general didactics and subject didactics. Referring to the constant tension between these two concepts, Buchberger and Buchberger (Citation1999) warn: ‘In many cases a tendency to isolate particular Fachdidaktiken from closely related ones, as well as a certain lack of integration may be observed—the individual learner might get lost, while expectations of a particular Fachdidaktik related to an academic discipline and its structures might become predominant […]. The frequently used justification of particular Fachdidaktiken, that they had to provide scientifically validated knowledge for different school subjects as defined by education politicians in (national) syllabi/curricula, could well give an impression of superficiality.’ Buchberger and Buchberger (ibid) call for closer integration between different subject-specific areas and their knowledge base.

Whether and to what degree this caution holds true for any particular context is, of course, a matter for separate empirical research and discussion. For our purposes, it is relevant to highlight the importance of a further elaboration of the GPK: a more precise definition of its meaning and content, and the opportunities and limitations of its application. The aim of our study is to clarify, by a systematic literature review, how the GPK of teachers has been defined, what kind of knowledge constitutes GPK (hereafter referred to as dimensions of GPK) and what the different ways to assess GPK are. Our initial search and screening of the articles indicated that although a significant number of articles deal with GPK, there are no systematic literature reviews that provide generalisations on the concept. The contribution of the current literature review to future research lies in the synthesis of previous studies. This provides the opportunity for better operationalisation of the concept in order to contribute to supporting teachers’ professional development. We formulated the following research questions:

(1) How can the concept general pedagogical knowledge be defined on the basis of existing studies?

(2) Which dimensions of teachers’ GPK can be distinguished?

(3) Which methods have been used to assess teachers’ GPK?

Methods

A systematic literature review method (see e.g., Higgins et al., Citation2019) was chosen to answer the research questions. A systematic review makes it possible to synthesise information about a specific issue that has been sufficiently studied in previous research without generalisations being made based on these studies. It has been pointed out that a simple description of the current status of research done on a particular topic is not sufficient for a good review (Gruber et al., Citation2020). Thus, the aim of using a systematic literature review is to extend existing knowledge through authors’ contributions to the fields of study. Therefore, we first planned a systematic search of articles and then a systematic analysis of these articles in order to understand the diversity in the definitions of the concept of GPK. Next, we aimed to provide a definition of GPK that would synthesise the most important characteristics of definitions used for GPK in previous studies. In addition, we found that there was particular value in providing an overview of the major dimensions of GPK studied in previous studies since these could be further used to systematically support and assess teachers’ GPK. Finally, we also aimed to describe by systematic analysis how GPK could be assessed in our study.

Literature search

Articles were searched for using the EBSCOhost Web service (search.ebscohost.com), which is one of the largest collections of databases of academic sources. The databases accessed through the EBSCOhost Web search engine were Academic Search Complete, ERIC, E-journals, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO and Teacher Reference Center. They cover almost all articles in other major databases, e.g., in the Web of Science. The keyword used for the search was: ‘pedagogical knowledge’ not ‘general pedagogical knowledge’. We omitted the word ‘general’, assuming that in some studies the difference between pedagogical knowledge and GPK would not have been made and the usage of ‘pedagogical knowledge’ would also reveal studies on GPK. Moreover, some studies have used the word ‘generic’ instead of, or interchangeably with, ‘general’ (Baumert et al., Citation2010; Tröbst et al., Citation2019). We intentionally did not include the name ‘Shulman’ among the keywords, which enabled us to detect articles that relied on other sources than Shulman in discussing GPK. However, we understood that some studies might focus on the concept of GPK even without using the term ‘pedagogical knowledge’, for example, simply using the term ‘teacher knowledge’. Our initial search with the term ‘teacher knowledge’ in the abstracts of the articles revealed more than three thousand articles and according to initial screening most of the found articles did not provide useful information to answer our research questions. Therefore, we decided to narrow the focus to the term ‘pedagogical knowledge’.

The procedure of the literature search and selection is displayed in . The abstracts and titles of the articles were searched for by the keyword, and the availability of the full text of an article was set as an eligibility criterion. The search was performed on 2 November 2016 among articles published from 1996 to 2016. The search was limited to papers in peer-reviewed academic journals and published in English. The search revealed 441 articles.

Figure 1. Flowchart of search and screening process according to the PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & the PRISMA Group, 2009)

The first round of article selection was done by screening the abstracts. Three inclusion criteria were used:

the subjects of the articles had to be pre-service teachers or in-service teachers of preschool or general school education;

the focus of the articles had to be on knowledge (it was not specified at this point that the article had to focus on GPK, as it was decided that is was too restrictive at the level of abstracts); and

the articles had to report empirical studies.

All articles that corresponded to the three criteria were selected for further analysis at the level of full texts. We excluded articles that focused on teaching methods, school curricula or other aspects but which only marginally concerned teachers’ knowledge. Sixty-four articles out of 441 remained for the second round of selection.

For the second round of selection and the screening of full texts, the second inclusion criterion was specified. The inclusion criteria were:

the subjects of the articles had to be pre-service teachers or in-service teachers of preschool or general school education;

the focus of the articles had to be on general pedagogical knowledge (providing information about definition, dimensions and/or assessment of GPK); and

the articles had to report empirical studies.

The second criterion eliminated articles that focused on teachers’ content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge. Some studies focused on a specific sample group (e.g., mathematics teachers). In such cases, we checked that the measure of GPK used in those studies could still be applied to different subjects, meaning it would not get mixed with PCK. In order to do so, the theoretical backgrounds and definitions of GPK in those articles were studied closely before including those articles in the sample. Altogether, 23 articles remained for the analysis.

Next, an analytical framework derived from the research questions was composed. For the first research question, the description and/or definition of the concept general pedagogical knowledge was checked both in terms of the content and the theory used in the analysed articles. A qualitative content analysis was conducted, using QCAmap software. The definitions were carefully analysed in order to determine the characteristics of GPK definitions (codes). They were further divided into larger themes (categories).

For the second research question, the dimensions of GPK were found. In addition, it was analysed whether the study focused on determining the dimensions or if the dimensions were retrieved from another study. The dimensions found in content analysis were further divided by the authors of the paper into categories.

To answer the third research question, we investigated the instruments used in the analysed studies to measure GPK. The type of approach and the instrument were determined. In addition to that, the quality indicators of the instrument were assessed.

Results

The 23 articles revealed through our search were published by 11 teams of authors (see, ). Out of the 23 articles, nine were written by one team, led by Johannes König. Although for one of these articles (Blömeke et al., Citation2016b) König was not a co-author, the leading author of this paper, Blömeke, co-authored three other articles led by König, which allowed us to categorise the paper in this group. Another group, represented with three articles, appeared to form around Doris Choy, the leading author of two papers, and one of the three co-authors of all three papers. Two Gatbonton (Citation1999, Citation2008) and Hudson (Citation2004, Citation2007), were both represented with two single-authored papers. Other authors, or teams, had one paper each in our sample.

Table 1. The coding of the articles

Definitions of GPK

Although the inclusion or exclusion of a single word rarely tells the whole story, our methodological decision to use the keyword ‘pedagogical knowledge’ (PK) instead of ‘general pedagogical knowledge’ (GPK) proved decisive. It emerged that whereas the usage of ‘GPK’ (whether as an acronym or spelled out) in a paper always indicated its affiliation with Shulman’s (Citation1986, Citation1987) proposal, the omission of the word ‘general’ still revealed, to an extent, a relation to Shulman’s contribution. Eleven out of the 23 articles, including all of those from König’s research group, used GPK as a key concept, although two of the articles (Atjonen et al., Citation2011; Liakopoulou, Citation2011) used the notions of GPK and PK somewhat interchangeably. Additionally, one article (Capel et al., Citation2009) used the notion of GPK just once, but in that case defined it with explicit reference to Shulman. Altogether, all 12 articles had Shulman’s aforementioned contribution as a conceptual basis.

The remaining 11 articles, which used the term ‘PK’ and did not use the term ‘GPK’, varied significantly in terms of their affiliation with Shulman. Three of these articles (Großschedl et al., Citation2015; Mullock, Citation2006; Torff & Sessions, Citation2005), in slightly varying terms, were closely affiliated with Shulman’s vocabulary and his division between CK and GPK, and they also cited Shulman’s (Citation1987) contribution. In general, this means that what was termed as PK in these three articles can be understood as GPK in Shulman’s vocabulary. The two articles from Gatbonton (Citation1999, Citation2008), using only the term PK, linked rather loosely to Shulman’s categories and did not juxtapose PK and CK. Hudson (Citation2004) cited Shulman (Citation1986) only in relation to PCK and, although he also referred to the frequent usage of the term PK, he cited other sources than Shulman for PK. Five papers (Choy et al., Citation2012, Citation2013; Happo & Määttä, Citation2011; Hudson, Citation2007; Wong et al., Citation2008) ignored Shulman’s contribution altogether.

Main characteristics included in the definition

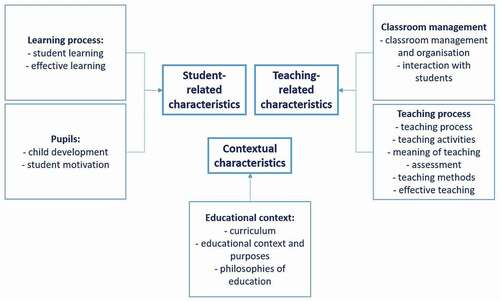

The analysis of the literature showed some similar characteristics of definitions of GPK throughout different studies. Most importantly, several studies from different authors were based on Shulman’s initial definition, although the definition of GPK was not limited to Shulman’s initial proposal. The literature analysis revealed three successive characteristics: student-related, teaching-related and context-related characteristics (). Definitions covering characteristics related to students focused mainly on the learning process, and students’ development and motivation. Teaching-related characteristics added classroom management and teaching process to the definition. Finally, definitions referring to contextual characteristics took into consideration the educational context, e.g., curriculum and philosophies of education. Next, the contribution to the GPK definition by different authors is described in more detail.

Studies by König and his co-authors added to Shulman’s definition of GPK the aspects of knowledge about learners and learning, assessment, and educational contexts and purposes. Happo and Määttä (Citation2011) were more focused on the learner, mentioning principles for supportive interaction with children and the principles of children’s development in order to promote student learning in the context of choices in teaching situations. Following this, supporting learners’ motivation was another aspect covered in the study of Großschedl et al. (Citation2015), and it was also mentioned in an improved definition in Lauermann and König’s (Citation2016) study.

Different aspects of the teaching process were captured in the definitions of GPK, e.g., instructional process and activities, teaching methods and effective teaching. Interestingly, Lauermann and König (Citation2016) combined different authors’ work in order to propose a definition based on general aspects of the instructional process and, therefore, covered principles for supporting student motivation and learning, classroom management, lesson planning and differentiated instruction. Choy et al. (Citation2013) also gathered information presented by different authors in order to describe a core body of knowledge consisting of various instructional methods, activities and assessment.

Knowledge of curriculum evidently received less attention, being mentioned only in Hudson’s (Citation2004) study and mainly in the context of science teaching. This brings us to the final aspect, which was seen as an overall characteristic of all parts of the definition of GPK: subject matter independence, or what Shulman would perhaps call transcendence over subject matter. This means that GPK is described and defined across different subjects in contrast to subject-specific knowledge (PCK and CK). This aspect was found in most of the studies included in the current analysis.

Dimensions of teachers’ GPK

Numerous dimensions of teachers’ GPK were identified in the articles. Several articles used the dimensions of GPK that were found in other studies; however, many defined dimensions based on their own study. Based on our qualitative analysis, we divided these dimensions into six larger categories that were consequently categorised into teaching-related and student-related dimensions (Appendix A). These two dimensions were in line with the characteristics found in analysing the definitions of GPK. However, one category of characteristics found in definitions did not appear among the dimensions: contextual characteristics of GPK (knowledge about curriculum, educational context and purposes and philosophies of education) have not been studied in depth in empirical studies.

Teaching-Related dimensions

Lesson planning. Lesson planning as a dimension of teachers’ GPK was identified in different studies. Overall, lesson planning is seen as a set of psychological processes for visualising the future that makes teaching more conscious and purposeful. For beginning teachers, it can also be used as the pedagogical reasoning for articulating what they plan to do and why (Choy et al., Citation2013). Lesson planning includes a variety of theoretical knowledge in order to plan and provide appropriate learning opportunities and, although it happens on a level that has no direct interaction with learners, the work supports the achievement of educational goals (Happo & Määttä, Citation2011).

Some literature suggests that lesson planning, as preparation for teaching, mainly consists of choosing the appropriate teaching strategies and methods (Choy et al., Citation2012, Citation2013; Hudson, Citation2004; Hudson et al., Citation2015; Wong et al., Citation2008), as well as structuring the lesson process and learning objectives (König, Citation2013; König et al., Citation2014, Citation2011; König & Pflanzl, Citation2016, Citation2016; König & Rothland, Citation2012) and selecting and preparing appropriate content (Choy et al., Citation2013; Hudson, Citation2004) and resources in order to implement a curriculum (Choy et al., Citation2012; Happo & Määttä, Citation2011; Wong et al., Citation2008). The planning phase also includes considering classroom management and assessment (Hudson, Citation2004; Hudson et al., Citation2015), the learning environment (Choy et al., Citation2013) and how to teach students with different ability levels (Choy et al., Citation2012; Wong et al., Citation2008). Altogether, lesson planning leads to timetabling (Hudson, Citation2004) and writing down lesson plans (Choy et al., Citation2012).

Instructional strategies. Supporting the development of novice teachers’ instructional strategies is seen as one of the most important roles of teacher education institutes (Choy et al., Citation2013). Instructional strategies, as a dimension of GPK, are described in the literature quite diversely and in complex ways. In her 1999 study, Gatbonton defined the domains of pedagogical knowledge, one of which is facilitating the instructional flow. The concepts and activities she used to describe this knowledge domain were techniques, procedures, starting activities, reviewing past lessons, pushing students to go on, directing students towards their intended goals, managing time, anticipating future activities, recapping activities and sensing how a lesson must proceed. In addition, in 2008 Gatbonton described the domain of instructional strategies as maintaining the flow of instructional activities and the appropriateness of instructional activities. Mullock (Citation2006) referred to Gatbonton’s 2000 facilitating the instructional flow pedagogical knowledge domain as a sense of how the lesson should unfold and the knowledge of techniques and procedures with respect to control of the classroom.

While Gatbonton focused more on carrying out the Choy et al. (Citation2012); (Citation2013) described instructional strategies in the context of the preparatory phase of the lesson: selecting appropriate resources and assessment modes to support instruction, producing teaching materials, incorporating information and communication technology effectively in the classroom, and designing and using assessment tools. Choy et al. (Citation2013) also referred to Darling-Hammond et al. (Citation1999) when describing instructional strategies in the context of pre-service teachers. The instructional strategies involved principles for transforming knowledge into actions in order to carry out effective teaching, evaluate student thinking and learning outcomes, plan appropriate learning opportunities, modify and use instructional materials to reach learning goals, understand and use several learning and teaching strategies, explain concepts clearly and appropriately, and provide students with useful feedback.

Based on these descriptions, it appears that instructional strategies were seen as a complex dimension of teachers’ GPK involving different phases of teaching. Großschedl et al. (Citation2015), on the other hand, came back to Shulman’s initial definition (1986; Shulman, Citation1987), claiming that his definition of pedagogical knowledge is very close to the knowledge of instructional strategies itself, covering the knowledge of teaching methods. Therefore, it can be concluded that the most common characteristic of instructional strategies through different studies is choosing and using appropriate teaching methods.

Classroom management. Capel et al. (Citation2009) defined GPK as the ‘broad principles and strategies of classroom management and organization that apply irrespective of the subject’ (p 52). As an example from this study, classroom management and organisation could mean working on getting the full attention of the group and not trying to talk over students. Classroom management plays an important role in achieving successful lessons and managing student learning-groups effectively (Wong et al., Citation2008). Building rapport in the classroom includes, for example, developing trust, not discouraging or embarrassing students, establishing a relaxed atmosphere, etc. (Gatbonton, Citation1999). In accordance with Gatbonton’s (Citation2000) study, Mullock (Citation2006) also emphasised teachers’ awareness of the need to make contact with students and to be aware of appropriate relationships between teachers and students.

Based on the above, it can be concluded that classroom management is another complex dimension of GPK. It is described in connection with effective teaching, behaviour and discipline management, building rapport with students, and supporting them to focus on tasks with appropriate classroom management techniques.

Assessment. According to Shulman (Citation1987), teachers’ GPK involves knowledge about assessment. Assessment is considered to be a typical part of course content in general pedagogy (König et al., Citation2014). The importance of assessment has been emphasised in several studies, as well as its relation to lesson preparation and planning for addressing students’ learning needs (Hudson, Citation2004; Hudson et al., Citation2015). Assessment occurs at various stages of teaching (Hudson, Citation2004) and can be used to assist students in their progress (Wong et al., Citation2008).

Assessment, as a dimension of GPK, is relevant with respect to student achievement (Brophy, Citation1999; as cited in König et al., Citation2011), which includes diagnosing principles and evaluation procedures, child-orientation and individuality (Happo & Määttä, Citation2011), and differentiation (Capel et al., Citation2009). Dealing with heterogeneous learning groups in the classroom is also described as adaptivity. In this framework, adaptivity includes strategies of differentiation and the use of a wide range of teaching methods (Blömeke et al., Citation2016; König, Citation2013; König et al., Citation2014, Citation2011; König & Pflanzl, Citation2016, Citation2016; König & Rothland, Citation2012). In a broad sense, this dimension highlights the importance of good knowledge about one’s students (e.g., Capel et al., Citation2009). Respecting each child’s individuality and being aware of the meaning of child-orientation is seen as a set of values in immediate interaction with children at a direct level of pedagogical knowledge (Happo & Määttä, Citation2011). More specifically, Choy et al. (Citation2012) described diversity as using evaluative feedback to assist students in their progress while teaching according to students’ pace, diagnosing students’ learning difficulties and responding sensitively to different student needs.

Assessing teachers’ GPK

The results of the literature review showed that teachers’ GPK has been assessed using two different approaches: 1) perceived level of knowledge and 2) testing of knowledge. The perceived level of knowledge means that participants were asked for their opinions of their own knowledge levels. These empirical studies were carried out using a survey. Testing for knowledge, on the other hand, included studies that assessed the level of GPK with a test. The methods and instruments for measuring teachers’ GPK are discussed in the following sections.

Perceived level of knowledge

In this literature review, articles about measuring teachers’ GPK have appeared since 2008, when Wong et al. published a study on a comparison of knowledge and skills held by primary and secondary school student teachers. To assess the level of teachers’ knowledge, a survey instrument with 34 questions was developed. Each participant had to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale their perception of their own knowledge level (1—no knowledge at all, 2—not so knowledgeable, 3—uncertain, 4—knowledgeable, 5—highly knowledgeable). The study was carried out longitudinally, measuring participants’ perceptions at the beginning and at the end of their studies. A factor analysis using principal components extraction was carried out with Varimax rotation, and the following five factors were found: facilitation, assessment, management, preparation, and care and concern. Finally, six questions were eliminated as they did not fit well with the data, leaving five or six questions for each identified factor. Unfortunately, the authors did not report on factor loadings. Indeed, they specified that the extraction of eigenvalue was set at over 1.10 for further analysis. The factors were considered fairly consistent, as Cronbach’s alpha for items varied from 77 to 89.

A similar study of self-perceived knowledge and skills was carried out by Choy et al. (Citation2012). In this study, a Perceptions of Knowledge and Skills in Teaching (PKST) survey was developed and validated. This process included an in-depth review of the relevant literature, expert consensus building, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). During data collection, the participants rated four to seven elements per factor on a 5-point Likert scale in order to report on their perceptions of their knowledge level. The development of this PKST survey resulted in 37 items strongly loaded on six latent constructs (with factor loadings from 50 to 82): student learning, lesson planning, instructional support, accommodating diversity, classroom management, and care and concern. The study also reported model fit indices with a ratio of χ2 to the degrees of freedom being 1.67, TLI 92, CFI 93 and the value of RMSEA 05. It showed that the model had good fit indices. As the main focus of this study was the validation of the instrument’s factor structure, the results of the study showed that the PKST survey can be adapted by different teacher education programmes to assess student teachers’ progress in developing their pedagogical knowledge and skills. The reliability of the instrument was rather good, with Cronbach’s alpha of 95 for the whole questionnaire and from 71 to 83 for the six latent constructs.

Testing GPK

In addition to studies reporting the perceived level of knowledge, studies measuring GPK level with a test have appeared since 2011. The majority of these studies have employed a TEDS-M (Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics) test that is aimed to assess the professional knowledge of future teachers. Although the initial TEDS-M test assessed mathematics’ content knowledge and mathematics pedagogical content knowledge, the German TEDS-M team, together with colleagues from the United States and Taiwan, developed a test measuring future teachers’ GPK (König et al., Citation2011).

During the development of the TEDS-M test, the researchers focused on instruction as the core activity of teachers (Berliner, Citation2001, Citation2004; Blömeke et al., Citation2008). As their perspective targeted elements that are directly under the control of the teacher, the researchers decided to employ the QAIT (Quality, Appropriateness, Incentive, Time) model of effective instruction (Slavin, Citation1994). According to König et al. (Citation2011), the four elements of the QAIT model correspond to elements of other models and listings of effective teaching. In addition to the QAIT model, the TEDS-M researchers also looked at the basic dimensions of teaching quality from a didactic point of view in order to define the topics of the QAIT framework (König et al., Citation2011). As a result, four dimensions of GPK were identified in the TEDS-M test as highly relevant with respect to the target group of future teachers: structure (structuring learning objects, lesson planning and structuring the lesson process, and lesson evaluation), motivation/classroom management (achievement motivation, strategies to motivate single students/whole groups, strategies to prevent and counteract interferences, and effective use of allocated time/routines), adaptivity (strategies of differentiation and use of a wide range of teaching methods), and assessment (assessment types and functions, evaluation criteria, and teacher expectation effects).

The final set of 77 items was distributed across four dimensions of GPK and three cognitive sub-dimensions (König et al., Citation2011). Item response theory (IRT) analysis showed that the reliability scores of a four-dimension model of GPK were lower (from 64 to 72) than the reliability for a one-dimension model (.78). However, the four dimensions were not highly correlated, indicating multidimensionality. In their conclusion, the authors claimed to have found evidence for distinguishing four dimensions of GPK.

A TEDS-M instrument was also used in later studies. For example, König (Citation2013) investigated how future teachers acquire GPK during their initial teaching education. In this study, an EAP (Expected A Posteriori) reliability of 86 is reported for the one-dimension model of GPK in IRT analysis. In 2014, König et al. examined whether GPK can be a premise for beginning teachers’ ability to notice and interpret classroom situations. The study reported GPK test reliability of 81 in a three-dimension model where the three dimensions were GPK, skill to notice, and skill to interpret. As the results of the literature review show, not much empirical evidence is provided for the dimensions of GPK and the instruments measuring it.

Discussion

The systematic literature review showed that GPK has been defined in various ways. Our findings allow us to conclude that the ongoing discussion on GPK is still essentially inspired by Shulman’s two papers, and particularly by his 1987 article which discusses GPK explicitly. Although we can conclude that the term ‘GPK’ is sometimes abbreviated to ‘PK’ (Atjonen et al., Citation2011, and Liakopoulou, Citation2011 are good examples), the concept of PK can also originate from other traditions which are unrelated to Shulman. Most notably, this is apparent in Wong et al. (Citation2008), Choy et al. (Citation2012), and Choy et al. (Citation2013). Significantly, there were no cross-references between this group of authors and the one which is most consistently affiliated with Shulman’s tradition and is now led by König. This indicates that these two groups of researchers generally relied on different conceptual traditions.

In regard to the term ‘general’ which proved decisive for our study, König et al. (Citation2014) shed light on a possible reason for the divergence, referring to differences between the Anglo-Saxon and the German-speaking Continental European educational traditions. In the former, notably in the US, ‘educational foundations’ and ‘teaching methods’ are the common labels that cover issues related to ‘general pedagogy’, whereas in the German tradition, these issues are discussed within certain foundational disciplines, such as general didactics (König et al., Citation2014). It is intriguing that, whereas Shulman’s ideas were initially received as long well-known to the German-speaking European audience (Kansanen, Citation2009), the most elaborate recent research tradition on GPK, explicitly relying on Shulman, now comes from Germany and especially from the research group of König.

The main characteristics included in the definition of GPK in our reviewed studies seemed to be classroom management, educational context, learning process, students’ development and motivation, teaching process and subject independence. As a result, we propose a revised definition of GPK that aims to synthesise the studies found in the review: GPK is defined as subject transcendent knowledge about learning and teaching processes, classroom management and educational context to support students’ development and motivation.

Our proposed definition includes three components. First, GPK is considered general knowledge that is important for teaching any subject (e.g., biology, languages or cooking): it is subject-transcendent. Second, the areas of instructional process on which GPK is focused are: both learning and teaching processes (e.g., how students acquire new knowledge through analogical reasoning or contrasting cases or inquiry-based learning, and how teachers should guide learners in these processes), classroom management (e.g., how to build a collaborative improvement-oriented learning environment), and educational context (e.g., how to organise learning and teaching activities in line with wider educational purposes). Third, the goals for which GPK should be used are: supporting students’ development (e.g., how to support the development of students’ learning and collaboration skills) and motivation (e.g., how to enhance intrinsic motivation). In comparison with those used in recent studies (e.g., Atjonen & Co, Citation2011; Capel et al., Citation2009; König et al., Citation2016), this synthesised definition is much broader. In comparison with Shulman’s (Citation1987) initially proposed seven categories of teachers’ knowledge, it clearly focuses on the following three categories: (1) general pedagogical knowledge, (2) knowledge of learners and their characteristics, and (3) knowledge of educational contexts. However, the last category also constitutes knowledge about curriculum, and educational context and purposes that are in accordance with two more dimensions specified in Shulman’s work (Shulman, Citation1987): (4) curriculum knowledge and (5) knowledge of educational ends, purposes and values, and their philosophical and historical foundations. This shows that during recent decades, GPK has been operationalised more broadly in different studies than in Shulman’s initial interpretation, where it was one of the seven dimensions.

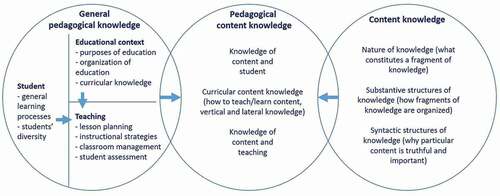

In the analysis of dimensions of GPK studies in recent decades, it appeared that the studies focused only on two of the three general categories of characteristics: (1) student-related dimensions and (2) teaching-related dimensions. However, the third dimension—contextual—could be easily integrated with the other two. In , a new framework is proposed to describe how the dimensions found in the current literature review—in the analysis of the definitions and dimensions of GPK—could be systematically presented and linked with each other and other categories of teachers’ knowledge: pedagogical content knowledge and content knowledge (see, Baumert et al., Citation2010; König et al., Citation2016).

Figure 3. Framework of general pedagogical knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge and content knowledge

In this synthesis, the student-related processes were divided into general learning processes and students’ diversity. The former is in accordance with the provided definition based on the literature review, and the latter adds one more aspect that was not directly indicated in the definition, although there was a focus on educational context (which is broader than students’ diversity-related context). The teaching-related dimensions cover all essential phases before, during and after the actual teaching process. Besides lesson planning, instructional strategies, classroom management and student assessment, which we highlighted in the literature as important areas of GPK, we propose to add knowledge about purposes of education, curriculum and educational context, because these aspects also appeared in the definitions of GPK.

According to the proposed framework, the dimensions of GPK are applied in building pedagogical content knowledge where content knowledge is also taken into account. For example, based on GPK, one knows how education is organised in general terms (e.g., what the general purposes of formal education are), how particular students learn (knowledge about both general learning processes and students’ diversity) and how to organise teaching and learning activities in the classroom (e.g., what the typical phases of a lesson are). Based on content knowledge, the teacher should know what students have to learn and why it is important. Now, the pedagogical content knowledge will be constructed as knowledge on the students’ level: how a particular student or a group of students can be motivated to learn some content and how this content knowledge should be acquired. In this framework, the broader view of GPK is revisited. However, based on the literature review, it is clear that most of these dimensions have not been the focus in assessing GPK. Teachers’ own perceptions of their knowledge can be limited to give an overview of their knowledge level. Also, the existing multiple choice test for measuring GPK seems to be limited in capturing the diverse dimensions of GPK. Therefore, further studies are needed to capture GPK in a more systematic way. Such studies could also reveal whether some of the dimensions described in this framework might be combined into one dimension based on empirical findings. Moreover, it is important to develop instruments that allow researchers to distinguish and explore different types of knowledge. It would be interesting to explore the three kinds of teacher knowledge as proposed by Neuweg (Citation2011): knowing in the objective sense, knowing in the subjective sense, and knowing manifested in action and the nature and use of theoretical and practical knowledge in teaching (Korthagen et al., Citation2001; Meijer et al., Citation2002; Pišova & Janík, Citation2011).

There are some limitations to this study. The search of the literature was limited to recent studies and a somewhat different view might be revealed if one included former studies as well. In addition, there is always a potential publication bias with literature reviews that use indexing databases to search for studies to be included. However, in this particular study, one of the largest collections of databases—EBSCOhost Web service—was selected. Thus, the literature review should provide a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge on GPK.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, D., & Clark, M. (2012). Development of syntactic subject matter knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge for science by a generalist elementary teacher. Teachers and Teaching, 18(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.629838

- Atjonen, P., Korkeakoski, E., & Mehtalainen, J. (2011). Key pedagogical principles and their major obstacles as perceived by comprehensive school teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 17(3), 273–288.

- Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108324554

- Baumert, J., Kunter, M., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Voss, T., Jordan, A., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., & Tsai, Y. (2010). Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge, Cognitive Activation in the Classroom, and Student Progress. American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 133–180. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209345157

- Berliner, D. C. (2001). Learning about and learning from expert teachers. International Journal of Educational Research, 35(5), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00004-6

- Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing about and learning from expert teachers. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 24(3), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467604265535

- Blömeke, S., Busse, A., Kaiser, G., König, J., & Suhl, U. (2016). The relation between content-specific and general teacher knowledge and skills. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.003

- Blömeke, S., Paine, L., Houang, R. T., Hsieh, F.-J., Schmidt, W. H., Tatto, M. T., Bankov, K., Cedilllo, T., Cogan, L., Han, S. I., Santillan, M., & Schwille, J. (2008). Future teachers’ competence to plan a lesson: First results of a six-country study on the efficiency of teacher education. ZDM - the International Journal on Mathematics Education, 40(5), 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-008-0123-y

- Brophy, J. (1999). Teaching. International Academy of Education.

- Buchberger, F., & Buchberger, I. (1999). Didaktik/fachdidaktik as integrative as integrative transformation science(-s) – A science/sciences of/for the teaching profession? Didaktik/Fachdidaktik as Science(-s) of the Teaching Profession, 2(1), 67–83 https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/5561196/tntee-publications-didaktik-fachdidaktik.

- Capel, S., Hayes, S., Katene, W., & Velija, P. (2009). The development of knowledge for teaching physical education in secondary schools over the course of a PGCE year. European Journal of Teacher Education, 32(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760802457216

- Choy, D., Lim, K. M., Chong, S., & Wong, A. F. L. (2012). A confirmatory factor analytic approach on Perceptions of Knowledge and Skills in Teaching (PKST). Psychological Reports, 110(2), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.2466/03.11.PR0.110.2.589-597

- Choy, D., Wong, A. F. L., Lim, K. M., & Chong, S. (2013). Beginning teachers’ perceptions of their pedagogical knowledge and skills in teaching: A three year study. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(5 68–79). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n5.6

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wise, A. E., & Kline, S. P. (1999). A licence to teach: Raising standards for teaching. Jossey-Bass.

- Depaepe, F., Verschaffel, L., & Kelchtermans, G. (2013). Pedagogical content knowledge: A systematic review of the way in which the concept has pervaded mathematics education research. Teaching and Teacher Education, 34, 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.03.001

- Depaepe, F., Vershaffel, L., & Star, J. (2020). Expertise in developing students’ expertise in mathematics: Bridging teachers’ professional knowledge and instructional quality. ZDM Mathematics Education, 52(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-020-01148-8

- Gatbonton, E. (1999). Investigating Experienced ESL Teachers’ Pedagogical Knowledge. Modern Language Journal, 83(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00004

- Gatbonton, E. (2000). Investigating experienced ESL teachers’ pedagogical knowledge. Canadian Modern Language Review, 56(4), 585–616. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.56.4.585

- Gatbonton, E. (2008). Looking beyond teachers’ classroom behaviour: Novice and experienced ESL teachers’ pedagogical knowledge. Language Teaching Research, 12(2), 161–182 doi:10.1177/1362168807086286.

- Großschedl, J., Harms, U., Kleickmann, T., & Glowinski, I. (2015). Preservice Biology Teachers’ Professional Knowledge: Structure and Learning Opportunities. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26(3), 291–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-015-9423-6

- Gruber, H., Hämäläinen, R. H., Hickey, D. T., Pang, M. F., & Pedaste, M. (2020). Mission and Scope of the Journal Educational Research Review. Educational Research Review, 30, 1–2 doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100328.

- Gutek, G. L. (2011). Historical and Philosophical Foundations of Education: A Biographical Introduction. Pearson Education.

- Happo, I., & Määttä, K. (2011). Expertise of early childhood educators. International Education Studies, 4(3), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v4n3p91

- Hashweh, M. Z. (2005). Teacher pedagogical constructions: A reconfiguration of pedagogical content knowledge. Teachers and Teaching, 11(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/13450600500105502

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Editors). (2019). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Hudson, P. (2004). Toward identifying pedagogical knowledge for mentoring in primary science teaching. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 13(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOST.0000031260.27725.da

- Hudson, P. (2007). Examining mentors’ practices for enhancing preservice teachers’ pedagogical development in mathematics and science. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 15(2), 201–217

- Hudson, P., English, L., Dawes, L., King, D., & Baker, S. (2015). Exploring links between pedagogical knowledge practices and student outcomes in stem education for primary schools. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(40 134–151). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n6.8

- Kansanen, P. (2009). Subject‐matter didactics as a central knowledge base for teachers, or should it be called pedagogical content knowledge? Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 17(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360902742845

- König, J. (2013). First comes the theory, then the practice? on the acquisition of general pedagogical knowledge during initial teacher education. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 11(4), 999–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-013-9420-1

- König, J. (2014). Designing an international instrument to assess teachers’ General Pedagogical Knowledge (GPK): Review of studies, considerations, and recommendations. http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/%0Apublicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/CERI/CD/%0ARD%282014%293/REV1&doclanguage=en (Paris, France: OECD)

- König, J., Blömeke, S., Klein, P., Suhl, U., Busse, A., & Kaiser, G. (2014). Is teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge a premise for noticing and interpreting classroom situations? A video-based assessment approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 38, 76–88 doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.004.

- König, J., Blömeke, S., Paine, L., Schmidt, W. H., & Hsieh, F.-J. (2011). General pedagogical knowledge of future middle school teachers: On the complex ecology of teacher education in the United States, Germany, and Taiwan. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 188–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110388664

- König, J., Lammerding, S., Nold, G., Rohde, A., Strauß, S., & Tachtsoglou, S. (2016). Teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching English as a foreign language. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(4), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116644956

- König, J., & Pflanzl, B. (2016). Is teacher knowledge associated with performance? On the relationship between teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge and instructional quality. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1214128

- König, J., & Rothland, M. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: Effects on general pedagogical knowledge during initial teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 289–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2012.700045

- Korthagen, F. A. J., Kessels, J., Koster, B., Lagerwerf, B., & Wubbels, T. (2001). Linking practice and theory: the pedagogy of realistic teacher education. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Lauermann, F., & König, J. (2016). Teachers’ professional competence and wellbeing: Understanding the links between general pedagogical knowledge, self-efficacy and burnout. Learning and Instruction, 45, 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.06.006

- Liakopoulou, M. (2011). Teachers’ pedagogical competence as a prerequisite for entering the profession. European Journal of Education, 46(4), 474–488 doi:10.1111/j.1465-3435.2011.01495.x.

- Meijer, P. C., Zanting, A., & Verloop, N. (2002). How can student teachers elicit experienced teachers’ practical knowledge? Tools, suggestions, and significance. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(5), 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248702237395

- Merk, S., Rosman, T., Rueß, J., Syring, M., & Schneider, J. (2017). Pre-service teachers’ perceived value of general pedagogical knowledge for practice: Relations with epistemic beliefs and source beliefs. PLOS ONE, 13(2), 1–25 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184971.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., & the PRISMA Group. (2009). Reprint-preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Physical Therapy, 89(9), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/89.9.873

- Mullock, B. (2006). The pedagogical knowledge base of four TESOL teachers. Modern Language Journal, 90(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00384.x

- Neuweg, G. H. (2011). Das Wissen der Wissensvermittler. In E. Terhart, H. Bennewith, & M. Rothland (Eds.), Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf (pp. 451–477). Waxmann.

- Pišova, M., & Janík, T. (2011). On the nature of expert teacher knowledge. Orbis Scholae, 5(2), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.14712/23363177.2018.103

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Research, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Slavin, R. E. (1994). Quality, appropriateness, incentive, and time: A model of instructional effectiveness. International Journal of Educational Research, 21(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-0355(94)90029-9

- Torff, B., & Sessions, D. N. (2005). Principals’ perceptions of the causes of teacher ineffectiveness in different secondary subjects. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(4), 530–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.4.530

- Tröbst, S., Kleickmann, T., Depaepe, F., Heinze, A., & Kunter, M. (2019). Effects of instruction on pedagogical content knowledge about fractions in sixth-grade mathematics on content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 47(1), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-019-00041-y

- Ulferts, H. (2019). The relevance of general pedagogical knowledge for successful teaching: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the international evidence from primary to tertiary education. OECD Publishing.

- Wong, A. F. L., Chong, S., Choy, D., Wong, I., & Goh, K. (2008). A comparison of perceptions of knowledge and skills held by primary and secondary teachers: From the entry to exit of their preservice programme. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 33(3 77–93). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2008v33n3.6

- Yang, X., Kaiser, G., König, J., & Blömeke, S. (2018). Measuring Chinese teacher professional competence: Adapting and validating a German framework in China. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(5), 638–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1502810