ABSTRACT

Becoming a teacher is difficult, especially in times of a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. We investigated how preservice teachers (PSTs) experienced their resilience, and which factors influenced resilience during the pandemic. We were interested in the following factors: 1) personal resources such as motivation, efficacy and emotions, 2) contextual resources such as relationships and support of colleagues, 3) coping strategies such as problem solving and maintaining a work-life balance. A questionnaire with both open and closed questions was completed by 443 PSTs. Compared to previous studies that used the same instruments, PSTs showed lower scores on resilience and personal resources, comparable scores on contextual resources, and higher on coping strategies. A regression analysis showed that all factors except for self-efficacy were related to resilience. The open answers revealed different aspects influenced by the pandemic, such as conditions for teaching at school, interaction with pupils, study progress, support from supervisors in their school and the teacher education institute, and social support received from important others, such as family and friends. Furthermore, factors were mentioned that influenced PSTs resilience in both enhancing and diminishing ways. The findings provide more insight into how societal and environmental circumstances affect teacher resilience.

Introduction

COVID-19 was an emotional rollercoaster, but I knew how to overcome it and find the positive side of the situation.

In this study, we examine key factors that influence preservice teachers’ resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Becoming a teacher is a challenging process, both physically and especially emotionally (Day et al., Citation2011). In this process, preservice teachers (PSTs) have to learn how to cope with the demands of two worlds: those of the teacher education programme and those of the schools. This can cause stress and possibly affects PSTs’ wellbeing, which may influence their intention to finish the programme or to even start as a teacher (Rots et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, as Dabrowski (Citation2020) mentioned, one can presume that the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the stress. In line with Mansfield et al. (Citation2016) and Vesely et al. (Citation2014), in the process of becoming a teacher and in particular when PSTs are faced with difficult situations, we argue that resilience is key. Resilience involves bouncing back after challenging or adverse situations but also thriving professionally and personally, which can lead to increased job satisfaction, enhanced wellbeing, and more commitment to the teaching profession (Mansfield et al., Citation2016). Previous studies have already shown the importance of resilience; e.g. mental wellbeing can be enhanced by teaching preservice teachers’ strategies to become resilient (Mansfield et al., Citation2016). Studies also showed that, early career teachers with higher resilience are more inclined to stay in the profession, where teachers with lower resilience may leave the profession (Hong, Citation2012). Doney (Citation2013) concluded that resilience is an important factor to encourage in beginning teachers, and thus in preservice teachers, because it will affect teacher retention. This might be even more relevant during times of a pandemic, as was illustrated in a qualitative study by Cromer (Citation2020) on teacher resilience building during the COVID-19 pandemic; this author also pleads for more training to support resilience.

A world-wide pandemic such as COVID-19 brings its unique challenges that can influence both the resilience experienced by PSTs and the possibilities they experience to deploy those resources that are needed to enhance their resilience. These challenges for our PSTs were related to the measures the Dutch government installed to prevent the virus from further spreading and pertained to rules and regulations, among which quarantine, social distancing and hygiene-related measures. Universities closed and went completely online and after a few weeks, schools for primary and secondary education were closed as well. Preservice teacher education shifted from face-to-face/live teaching to online, sometimes asynchronous teaching, which forced preservice teachers to study from home. Because of the closing of schools, teaching practicums were shifted online or sometimes even cancelled.

This shift to online education and online (or lack of) practicums has most likely influenced preservice teachers’ learning, their wellbeing and resilience. We noticed in our conversations with students and educators that, as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures, PSTs encountered many and different challenges. For example, related to the measures of social distancing at school, the nature of teaching tasks can lead to PSTs having difficulties keeping their distance from the pupils. For instance, how does one comfort a toddler when it is crying, or how does one apply a bandage keeping the distance in mind? Furthermore, the measures of social distancing can impact the social support PSTs experienced from their friends and families. How do you discuss problems with family and friends if you cannot be close to them? The quarantine implied that PSTs had to work from home, which caused challenges such as fuzzy boundaries between study/working life and private life, and also more practical problems such as not having an own room in the house to work, or not having an appropriate set-up for teaching. PSTs also experienced challenges related to not being able to go to the teacher education institutes and attend face-to-face classes, dealing with differences in the organisation and sometimes even the requirements of the TE-programme. As an example, many PSTs were no longer allowed to teach in practicums at their schools; certain assignments which focused heavily on practice (i.e. observing peers), had to be re-written as they could no longer be done as planned.

Some PSTs may have experienced the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting measures as a challenge, stimulating them to find the positive side of the situation like the preservice teacher cited above. However, it is just as likely that not all PSTs were able to deal with this situation. These probable, contrasting, reactions prompted questions about PSTs in challenging situations, such as why do certain PSTs face these challenging circumstances and survive, or sometimes even thrive? And, how are PSTs perceptions of challenges related to the process of becoming a (better) teacher? These potential differences in resilience and opportunities regarding personal and contextual resources and strategies could explain the extent to which PSTs feel able to deal with a challenging situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

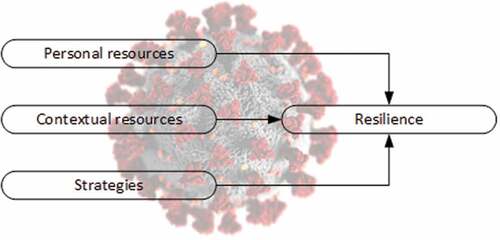

In the current study, we explored how preservice teachers report on their resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. More specifically, we investigated the factors that influenced PSTs resilience during the pandemic. The starting point in our study was the conceptual framework developed by Mansfield et al. (Citation2016). In their review study they distinguished four key factors that that should be considered when trying to stimulate resilience in teacher education. They pointed towards the importance of acknowledging and addressing: 1) personal resources such as motivation, efficacy and emotions, 2) contextual resources such as relationships and support of colleagues, 3) coping strategies such as problem solving and maintaining a work-life balance and 4) outcomes, that is, professional outcomes such as commitment and job satisfaction and academic outcomes such as persistence and achievement in teacher education. For PSTs, the resilience process is multifaceted and dynamic as the different resources interact over time, and, Mansfield et al. (Citation2016) proposed that teacher education should pay attention to aspects such as how to strengthen relationships, focusing on one’s wellbeing and motivation, learning to take initiative and managing emotions of PSTs. Still, we need to know more about how the above-mentioned factors are related to PSTs’ resilience during challenging times. In our study, we therefore focused on examining these key factors (personal resources, contextual resources, strategies and outcomes) in relation to resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic (see ). We specified the following research questions:

Figure 1. Resources, strategies and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What are PSTs’ perceptions of their resilience, resources and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic?

How are Dutch PSTs’ personal and contextual resources and coping strategies related to dealing with the challenges they face during the COVID-19 pandemic?

What ware PSTs’ experiences in relation to the quality of their teacher education programme and their own learning and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Materials and methods

Sample/design/analysis

A questionnaire was developed, that consisted of both open and closed questions about, among others, PSTs’ resilience, resources and coping strategies. The questionnaire was distributed in May/June of 2020, through the four institutions that participated in the project (see acknowledgements for more information about the project), and through social media. The questionnaire was anonymous and all participants were informed that the data would be only used for research purposes. Research clearance has been obtained from the Ethical Committee . Overall, 443 PSTs completed the questionnaire. Responses from those PSTs who had answered most of the items and had data for the resilience scale were included in the analysis (55 PSTs were excluded).

We wanted to examine resilience, resources and coping strategies both quantitatively and qualitatively. We focused on the key factors that might enhance resilience specified by Mansfield et al. (Citation2016): personal resources, contextual resources, and coping strategies. Furthermore, we added questions on the COVID-19 pandemic. For the questionnaire we limited ourselves to measuring one variable that is considered a personal resources (teacher self-efficacy), one that is considered a contextual resources (social support and network), and one variable that is considered a strategy (coping strategies). We did not limit preservice teachers in their response to our open questions. Thus in relation to resources and strategies they could have mentioned the three above, or totally different ones (e.g. the negative emotions they experiences or maintaining a healthy work-life balance). Descriptive statistics and a regression analysis with method enter were used for the quantitative data. The open questions were analysed by using a content-analysis approach, where we focused on describing PSTs’ resilience and factors that influence their resilience.

Variables and instruments

Resilience

Resilience was measured with the Dutch version of Smith et al. (Citation2008) Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). It consists of six 5-point Likert scale items. An example item is: ‘It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event’. This scale had a sufficient reliability, Cronbach’s alpha=.79.

Teacher self-efficacy as a personal resource

To measure one of the personal resources PSTs might have, we used the four item Self-efficacy for teaching (4-point Likert) scale from the Talis project (OECD, Citation2010 (Cronbach’s alpha =.79). An example item is ‘I feel that I am making a significant educational difference in the lives of my students’.

Social support and networks

To measure PSTs relationships and support of colleagues, we used the the Social Resilience Scale (Keijzer et al., Citation2020), an eight-item 5-point Likert scale. An example item of this scale is: ‘I have someone to talk to if there’s trouble’ is an example item. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .88.

Coping strategies

We focused on coping strategies and used the coping self-efficacy scale short form (11-point Likert scale), developed and validated by Chesney et al. (Citation2006). We adapted this to the teaching context by adding the words ‘when something goes wrong during teaching I am confident that I’ to the stem. The original scale consists of three subscales: use problem-focused coping (Cronbach’s alpha=.81); stop unpleasant emotions and thoughts (Cronbach’s alpha =.88) and get support from friends and family (Cronbach’s alpha=.59). This last subscale failed to be acceptable reliable and was not used in the further analyses. An example item of the use problem-focused coping subscale was ‘Break an upsetting problem down into smaller parts’, an example item for the stop unpleasant emotions and thoughts subscale was: ‘Make unpleasant thoughts go away’.

COVID-19 pandemic

In the survey, we asked the respondents in two open answer questions: 1) whether or not they think that they have filled out the survey differently now compared with the pre-COVID-19 period, and in what sense, and, 2) in which way the COVID-19 measures had affected their resilience and well-being. We coded the answers to these question based on the broad categories mentioned in the introduction: personal and contextual resources, coping strategies and personal or academic outcomes. From those broad categories, we discussed which themes emerged from the data during four collaborative online discussions. For this, we iteratively coded several sets of data samples, using the broad categories, and compared and discussed differences until agreement was reached. The answers to these open questions provide illustrations of how COVID-19 has affected these preservice teachers academic and/or professional life and which personal or contextual resources contributed to positive or negative outcomes.

Results

Perceptions of resilience, resources and coping strategies

In this section, we discuss the quantitative data and qualitative data for the personal and contextual resources, as well as for the coping strategies. We will start with a description of PSTs perceptions of their resilience.

Resilience

PSTs scored their resilience around the mean scale score, which means that their resilience is neither quite high nor quite low (see ). However, when comparing this score to samples in the original Smith et al. (Citation2008) study, that focused on among others undergraduate students and rehabilitation patients, we found that the mean score in the present study was lower. The Smith et al. (Citation2008) study found mean scores between 3.53 (0.69) for the undergraduate students up to 3.98 (0.76) for the rehabilitation patients. The score found in our study was also lower than that found in the O’Brien at al. (Citation2020) study, which focused on Irish PSTs (mean scores was 3.24 (.79)).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and correlations.

Personal resources (teaching self-efficacy)

When looking at the personal resources we noted that the PSTs were rather positive about their teaching self-efficacy. For example, they felt that they could make a difference in the lives of their pupils and would be successful with pupils in their classes. However, the mean score was lower than those found in comparable studies (i.e. Fackler & Malmberg, Citation2016).

In general, the PSTs’ qualitative answers about the consequences of the COVID-19 measures showed a lot of variation. Below, we illustrate how PSTs reactions varied from ‘positive’ and ‘strengthened’ to ‘negative’ and ‘insecure’ for all factors associated with resilience, and, in addition how PSTs thought about changes in the teacher education programme and their own learning in this respect.

We found that PSTs reported on different emotions related to the COVID-19 measures. These emotions varied from strengthened and more certain to insecure and stressed. One PST stressed that he/she became more secure about him/herself in the new situation:

I started to feel more confident about my own competences and strengths which I can share with my team.

PSTs also stressed negative emotions, often in relation to contextual resources such as support and social connections. The COVID-19 measures were often thought to enlarge already difficult situations:

I experienced a lot of stress due to the COVID-19 crisis, because I am in a rather difficult home situation. I noticed that I have a less energy and motivation to keep working on my courses.

And

More often than usual, I feel depressed and alone. As a result, my wellbeing is of course less.

Contextual resources

Related to the contextual resources, we found that PSTs were also quite positive about support from friends or family, e.g. they indicated that they had people they could talk to when experiencing problems and they were helped by their friends and family (see ). Though somewhat higher, the scores for the contextual resources were comparable to those in the original study (R. Keijzer, personal communication 22 January 2021).

When looking at the qualitative data we see that, for the PSTs, social distancing was clearly a measure with a lot of negative impact, although it also helped PSTs to realise the importance of connectedness:

‘Discovered that friends and family are really important.’

However, PSTs mostly reported on missing relatives, friends, colleagues, teachers and students. Being (dis)connected from others influenced resilience for a number of reasons, as was strikingly formulated by this PST:

Less social contact, involving less opportunities to share experiences, and working more solitary which also has its consequences for the supervision from school.

Strategies

In our questionnaire, we asked PSTs about their coping strategies to deal with difficult situations during teaching, related to their problem-solving strategies, and how they would deal with unpleasant thoughts. PSTs had mean scores around the scale mean, however the standard deviations for both scales were rather high. Compared to the scores in the original study by Chesney et al. (Citation2006), we found higher mean scores for both scales; the standard deviations in the original study were also high. The standard deviations were smaller for problem focused coping and comparable for the stop unpleasant emotions and thoughts scale.

In response to the open questions PSTs tended to focus on (difficulties with) maintaining a good work-life balance, and not so much on problem-solving strategies or dealing with unpleasant thoughts. Instead, they indicated that their work-life balance was thrown, resulting in reflections on difficulties in finding a space to relax:

‘The only thing that I experience is having difficulties concentrating on school, work and practicum. Even though I am in a separate space in the house, I am still distracted quickly by sounds outside, by things that need to be done in the house, etc. Normally, I study in the library and whenever I couldn’t concentrate anymore I would go home to relax and move out of the “working”-climate. Now one’s house is one’s office, study place, practicum place and also the place to relax. I therefore find it difficult to relax for 100%, because one’s workplace and work is always visible.’

At the same time, for some PSTs the limitations because of the COVID-19 measures resulted in a situation of diminished stress and less unpredictable challenges with regards to combining work, internship and studies:

Very positive (except for the societal stress and worries about my parents and grandma), because I have more time to rest and can stay in my own home and environment more often. This allows me to re-charge after stressful situations and I am much less exposed to overwhelming-environments.

Resources, strategies and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic

Our second research question focused on the relationship between the factors and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Again we start with a discussion of the quantitate findings followed by the qualitative findings.

Relationship key factors and resilience: quantitative findings

We examined the zero-order correlations between the key factors and resilience. Here significant relationships of resources and strategies with resilience were found, where stopping unpleasant emotions and thoughts showed the highest correlation (r = 0.55, p < 0.01), and self-efficacy the lowest (r = .13, p < .05). After that, linear regression analysis was used to analyse the relationship between the resources, strategies and resilience. indicates the standardised coefficients for the regression analysis. All variables except teaching self-efficacy were significant predictors of resilience. That is, the more PSTs perceived that they had opportunities for social support, the more they thought they were able to use problem solving skills, and the more they thought they could cope with negative thoughts and emotions, the higher their resilience.

Table 2. Regression analysis for variables predicting resilience.

Consequences of the COVID-19 measures in relation to resources and strategies

PSTs were found to report on both positive and negative consequences because of the COVID-19 measures. On a positive note, PSTs noticed that normal relations became different, responsibilities and co-dependencies were reformed. In the words of a PST:

I am much more digitally competent than my co-workers, which suddenly gave me a head start and allows me to give more valuable input.

The negative consequences for PSTs mostly reflected a loss of energy. PSTs reported on being tired because of the challenging circumstances, for instance:

It costs a lot of energy to re-design education and getting used to the temporary measures together with the children.

Interestingly, PSTs were found to show in their answers an awareness of their development in resilience during the pandemic. They both reported on a renewed evaluation of certain qualities and skills as well as on changes in how they dealt with difficult situations and what this taught them about themselves in relation to demands of the profession:

‘I discovered how resilient and flexible one should be.’

And:

Staying at home has made me think a lot about myself. I felt bad for a while, for having to be only with myself. However, this has resulted in me feeling better about myself, and also in feeling more able to put things in perspective.

Answering a questionnaire about resilience for some PSTs triggered a general reflection about their situation and their development in teacher education, illustrating how resilience for PSTs is dynamic and related to self-awareness:

I noticed that my motivation for my study has decreased due to working from home. I miss social and physical contact with my peers, teachers and my classroom full of pupils at the practicum school. I also reflect more on things, because I have more time for that. This may have positive consequences, but sometimes also has negative consequences. It is important to remain positive.

Quality of the teacher education programme and PSTs’ professional development

The third research question focused on PSTs experiences in relation to the quality of their teacher education programme, their own learning and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. In relation to the teacher education programme, PSTs mentioned organisational problems such as assignments that were postponed due to the closure of schools or delay (and uncertainty) because school practicums were postponed. For example one respondent mentioned:

It is rather uncertain what the remainder of my teacher education looks like, do I have study delay? Will I be able to finish my internship?

And another:

There is a lack of clarity at school. This may result in stress for deadlines and finishing courses. Especially with all the work ahead.

One PST also mentioned this uncertainty, and how it had affected beliefs on whether teaching would be a good career. However, this PST also referred to coping strategies, i.e. stopping unpleasant thoughts and emotions, for being able to deal with these uncertainties:

The uncertainty and lack of clarity from the teacher education programme cause much stress; this makes me doubt about whether the teaching profession fits me. However, I now try to separate these two things, these are two different things and it is an uncommon situation.

Another respondent explicitly mentioned that the COVID-19 crisis intensified the teacher education programme and it made teaching at schools rather boring.

The corona impact intensifies my teacher education, it also makes it boring (with more online, less interaction, especially considering doing the internship in the teaching practicum online).

Some PSTs explicitly mentioned that they missed the opportunity to work on their pedagogical qualities, sometimes related to the fact that their experience was now solely online. In response to the question whether or not the PST estimated that they would have answered the questionnaire differently before the COVID-19 pandemic, one PST mentioned:

‘No, but then I would feel somewhat more certain about my own pedagogical qualities. I wanted to work on those but haven’t had the opportunity to do so anymore.’

Another PST doesn’t explicitly mention the word pedagogical qualities, but refers to it when he or she discusses only having positive experiences with teaching:

Yes, I now only have positive experiences with teaching, as I am good at online teaching. You are not in front of a class with 30 students, but you are talking to a laptop. Because I have so little contact with pupils, I haven’t had any negative experiences yet.

PSTs also mentioned other quite positive effects on their own teaching competences. For example:

‘I feel more creative since I am forced to think about education differently.’

And:

In the first period of remote teaching my tasks as intern where very limited, and despite my enthusiastic and pro-active attitude I could do hardly anything to nothing. This started to get demotivating. Now this has changed. And, I am very active in a role which I feel is indispensable within the team. I feel valued and am motivated, enthusiastic and proud. The alternative teaching situation is a challenge, I get energised from thinking about alternative ideas to design lessons and teaching them in this new situation.

Discussion

Becoming a teacher is difficult, especially in times of a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Even more so, it is important to focus on learning how to become and stay resilient as a teacher and to know which factors are important in that respect. In the current study, we investigated how preservice teachers experienced their resilience, and which factors influenced PSTs resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first question concerned PSTs resilience, self-efficacy, social support, and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, PSTs score around or above the mid-scale scores for all scales. When compared to previous studies using the same scales, we found that the PSTs in our sample showed lower resilience and self-efficacy. For example, our sample revealed even lower scores on the Brief Resilience Scale than those reported by O’brien et al. (Citation2020), who concluded that the PSTs in their sample had significant lower scores than the normative population. Our PSTs also reported lower scores on the self-efficacy for teaching scale compared to those in the study by Fackler and Malmberg (Citation2016). The lower scores on both resilience and personal resources might have been related to the COVID-19-related measures. One could imagine that it would be hard for PSTs to ‘make a significant educational difference in the lives of my students’ without actual opportunities to practice and experience success in their work. As, Beltman et al. (Citation2011) indicated ‘[…] in relation to important individual factors such as motivation and self-efficacy, as teachers experience success their work, this builds their self-efficacy which then leads to greater persistence.’ (p. 105). However, the lower scores may also be explained by our sample of PSTs with fewer years of teaching experience. We found higher scores on the two subscales of the coping self-efficacy short form compared to these mentioned in previous samples. This might again be related to the COVID-19 related measures; without actual face-to-face teaching in practicums it might be difficult to ‘leave options open’ when some things go wrong during teaching.

In the qualitative data, related to personal resources, PSTs mentioned aspects such as feelings of boredom or being overwhelmed. PSTs mentioned both positive and negative effects related to contextual resources such as an increase of support from supervisors at the teacher education institute which motivated preservice teachers to seek support from others more often, feeling empowered by having knowledge and skills needed for the new situation (e.g. online teaching), and the lack of opportunities to share experiences. When looking at the coping strategies, we see that PSTs mentioned aspects such as dealing with an increase of work pressure.

The second research question focused on the relation between the key factors and resilience. Here we found that all factors except for the personal resource of teaching self-efficacy were related to resilience. Our qualitative findings indicated that PSTs were both positively and negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. They mentioned different aspects that were influenced such as the conditions for teaching at school, changes in the type of interaction with pupils, their study progress, the support from supervisors in their school and the teacher education institute, and social support received from important others, such as family and friends. Next to this, aspects were mentioned that influenced their resilience in both enhancing and diminishing ways. PSTs also showed an increase in their awareness of their development in resilience during the pandemic, which is important as according to Mansfield et al. (Citation2016, p. 83) it may promote a sense of agency in times of challenge.

Related to the quality of the teacher education programme and PSTs’ own professional development PSTs mentioned organisational problems, other PSTs mentioned aspects such as uncertainty about the remainder of the year and even uncertainty related to whether the teaching profession was a good career choice. PSTs also mentioned the increasing workload due to the shift to online teaching, and the lack of opportunities to actual practice to improve competencies, whereas others mentioned the positive effects in terms of creativity and innovation.

Our assumption was that the COVID-19 pandemic would influence the resilience PSTs experienced as well as the personal and contextual resources and coping strategies that could explain why PSTs might differ in their resilience. First indications for differences in resilience, resources and coping strategies where found in the qualitative data analyses, which illustrated the different ways that PSTs deal with stressful and challenging situations. This finding actually reflects the findings in a report by Allen et al. (Citation2020) who investigated teacher wellbeing in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. They used Teacher Tapp data to monitor teachers’ wellbeing throughout the academic year and found that the COVID-19 pandemic affected teachers’ wellbeing in different ways. They found some teachers: ‘[…] having more energy and feeling more loved, but also being less likely to feel useful and optimistic about the future.’ (p. 18). We did not find one common indicator for explaining why certain PSTs were more resilient. Instead, PSTs mentioned different (combinations of) personal and contextual resources and coping strategies to deal with the challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic. This concurs with the study by Beltman et al. (Citation2011, p. 27), which described resilience as a complex, idiosyncratic and cyclical construct.

There were several limitations to this study. These originate from the sample, procedure and the instruments used to collect our data. We used cross-sectional data to examine PSTs resilience and the key factors that are of importance. Since, at the time of measurement, we were at the forefront of the pandemic, it would have been interesting if we could have measured or monitored resilience, resources and strategies more frequently over time, to gain more insight into whether and how these variables undergo changes during the year. Second, as mentioned above, we examined the relationship between the key factors and resilience using a correlational design. Consequently, we cannot actually prove a causal relationship between these two. It is important to take this into account when examining the findings of our studies.

The findings from the current study can give raise to approach the concepts of teacher resilience from a broader perspective, for example by also including societal conditions. This study highlights the importance of scaffolding social resources during teacher education, in line with Collie et al. (Citation2016) who showed that teachers with many positive relationships with students and colleagues indicate higher levels of wellbeing, both in the profession as well as in daily life. The findings are also in line with Dabrowski (Citation2020), who in her study among teachers, also emphasised the need for support and the importance of social capital in a broader context (i.e. not only on an individual level, but also taking into account the organisational level). According to Dabrowski (p. 38), this so-called enhanced social capital ‘… can lead to a collaborative and proactive approach to building relationships and community bonds.’ Furthermore, the findings may inspire teacher trainers and developers of teacher education programmes who wish to assist preservice teachers in developing resilience skills. This finding is also underlined by the study by Cromer (Citation2020) that suggested that is important for school leaders to consider strategies for fostering collaboration. This would help teachers ensure they have the power to meet challenges, and understand that there is support available to them. An example for PSTs might be a group work variant where peer student teachers can support each other; this could be a good way to support this process and may also help to overcome feelings of isolation.

However, the study also yields more questions, such as how can we continuously assure the quality of teaching at teacher education programmes in an online situation? And, how do we enhance the teaching quality for those PSTs who are in a difficult home situations? Even though at the time of writing this manuscript our PSTs have almost had a year of dealing with the challenges of the pandemic, it seems important to continuously monitor their resilience and the resources and the coping strategies they use. In the end, though PSTs may display different levels of resilience, and focus on different resources and strategies to deal with challenging situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, one PST had a clear vision and future goal, that is, to work as a teacher in education and this is what kept this PST going:

The corona crisis has not changed my vision to education and myself as an individual. I only became more aware of my goals, i.e. working in education

Acknowledgments

The data collected in this manuscript is part of the project ‘Life is tough but so are you: Enhancing preservice teachers’ resilience’ (40.5.18650.036) funded by the Netherlands Initiative for Education Research (NRO). We also acknowledge the support of our other consortium members, including Monika Louws, Ietje Pauw, and Irene Poort, and the BRiTE team members, Caroline Mansfield and Susan Beltman.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allen, R., Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2020). “How did the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic affect teacher wellbeing?.” CEPEO Working Paper Series 20-15, Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities, UCL Institute of Education, revised Sep 2020.

- Beltman, S., Mansfield, C. F., & Price, A. (2011). Thriving Not Just Surviving: A Review of Research on Teacher Resilience. Educational Research Review, 6(3), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2011.09.001

- Chesney, M. A., Neilands, T. B., Chambers, D. B., Taylor, J. M., & Folkman, S. (2006). A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(3), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910705X53155

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., & Martin, A. J. (2016). Teachers’ psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000088

- Cromer, G. (2020). How Can Teacher Training Maintain Rigor and Increase Resilience Beyond Covid-19? [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Trident University International.

- Dabrowski, A. (2020). Teacher wellbeing during a pandemic: Surviving or thriving? Social Education Research, 2(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021588

- Day, C., Edwards, C., Griffiths, A., & Gu, Q. (2011). Beyond survival: Teachers and resilience. Retrieved from: http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/education.

- Doney, P. A. (2013). Fostering Resilience: A Necessary Skill for TeacherRetention. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 24(4), 645–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-012-9324-x

- Fackler, S., & Malmberg, L. -E. (2016). Teachers’ self-efficacy in 14 OECD countries: Teacher, student group, school and leadership effects. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56, 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.002

- Hong, J. Y. (2012). Why do some beginning teachers leave the school, and others stay? Understanding teacher resilience through psychological lenses. Teachers and Teaching, 18(4), 417–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.696044

- Keijzer, R., Admiraal, W., Van der Rijst, R., & Van Schooten, E. (2020). Vocational identity of at‑risk emerging adults and its relationship with individual characteristics. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20(2), 375–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09409-z

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., & Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education: An evidenced informed framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.016

- O’brien, N., Lawlor, M., Chambers, F., Breslin, G., & O’brien, W. (2020). Levels of wellbeing, resilience, and physical activity amongst Irish pre-service teachers: A baseline study. Irish Educational Studies, 39(3), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1697948

- OECD. (2010). Talis 2008. Technical Report. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264079861-en

- Rots, I., Aelterman, A., & Devos, G. (2014). Teacher education graduates’ choice (not) to enter the teaching profession: Does teacher education matter? European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2013.845164

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

- Vesely, A. K., Saklofske, D. H., & Nordstokke, D. W. (2014). EI training and pre-service teacher wellbeing. Personality and Individual Differences, 65, 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.052