?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In spite of a prominent discussion in the literature about the relationship between theory and practice in teacher education there is a lack of empirical research examining the effects on teachers’ development of professional knowledge after graduating from higher education into teaching practice. This study uses a database of 191 German and Austrian teachers whose general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) was tested at four time points to cover their teaching career from entering into initial teacher education through graduation until entering the teaching profession. In both country contexts, teachers acquire knowledge during their initial teacher education, indicating the impact of formal opportunities to learn (OTL) during higher education. However, the knowledge growth discontinues at the transition from academic learning in higher education institutions into teaching practice at school. Teachers with high school grade point average (GPA) are significantly less affected, which reflects the relevance of future teachers’ cognitive entrance characteristics to higher education.

Introduction

How theory and practice should be linked to design coherent learning opportunities in teacher education programmes has been subject to controversial discussions for decades (Flores, Citation2016; F. A. J. Korthagen, Citation2010; F. A. J. Korthagen & Kessels, Citation1999; Lawson et al., Citation2015; Shulman, Citation1998; Zeichner, Citation2010). Whereas universities provide relevant learning content with the aim to support preservice teachers’ acquisition of teacher knowledge, practice teaching is mainly placed at school (European Commission, Citation2013, p. 45). There is a critical discussion that traditional programmes tend to be divided between university and school-based training. In contrast, approaches integrating educational coursework and fieldwork early and throughout teacher education programmes have been favoured (Ball & Forzani, Citation2009; Darling-Hammond, Citation2000; Nelson & Voithofer, Citation2022). Although balancing theoretical and practical learning opportunities for preservice teachers has become a decisive issue in evaluating teacher education programmes, empirical findings on the transition of early career teachers into practice after graduation from university or teacher training college programmes are limited (Tatto et al., Citation2020). One reason for this is the lack of longitudinal studies that would allow in-depth insights into the learning and the professionalisation process of teachers from their entering into initial teacher education through graduation until starting their career as professional in-service teachers (Kaiser & König, Citation2019; Rowan et al., Citation2015).

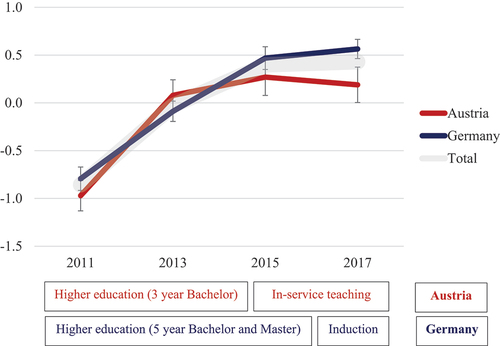

Against this background, the present study uses a database of 191 German and Austrian teachers whose general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) was tested at four time points: Starting with their entrance into initial teacher education in 2011, they were continuously followed up every two years (2013, 2015, and 2017). Due to a very short Bachelor programme, Austrian teachers had entered professional teaching when surveyed in 2015. Due to a relatively long training, German teachers had entered induction when surveyed in 2017. We analyse the data to answer two research questions focusing the transition that happened between time points 2013 and 2015 in Austria and between time points 2015 and 2017 in Germany:

Does the transition from higher education into teaching practice supports teachers’ further development of GPK?

Do institutional factors (opportunities to learn) and individual factors (entrance characteristics of students) predict teacher GPK development at the transition?

Theory–practice relationship in teacher education

There is a long tradition to discuss the relationship between theory and practice in training teachers in particular, regarding higher education (Flores, Citation2016; F. A. J. Korthagen, Citation2010; Lawson et al., Citation2015; Zeichner, Citation2010). Universities provide relevant learning content and therefore support preservice teachers’ acquisition of content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and general pedagogical knowledge (König et al., Citation2018; König et al., Citation2022; Schmidt et al., Citation2011). In contrast to this, schools are considered being the sites of teaching practice and therefore support the acquisition of teaching skills (European Commission, Citation2013, p. 45). Dividing the curriculum into content and teaching practice even affects teachers’ perceptions of teacher education (Flores et al., Citation2014; König et al., Citation2017).

Practical learning opportunities serve to approach teacher professionalism in a proactive and responsible way (P. Grossman et al., Citation2009; F. A. Korthagen, Citation2001), they help teachers to acquire teacher expertise, as they support them in progressing from the stage of novices to advanced beginners (Berliner, Citation2004; Stigler & Miller, Citation2018) and in starting to become a reflective practitioner (Schön, Citation1983). In many countries worldwide, teaching practice is considered as a key element of teacher education (Arnold et al., Citation2014; Flores et al., Citation2014; Wilson et al., Citation2001). However, there is diversity with regard to how teaching practice is linked to the academic part of teacher education. A general distinction can be found with regard to the way a teacher education curriculum focuses on theoretical study in contrast to a more practical training. Whereas short-term programmes or a mere training on the job have turned out to be inappropriate (Darling-Hammond, Citation2000), the adequate design of the theory-practice relationship is still subject to teacher education reforms worldwide (Ball & Forzani, Citation2009; Clift & Brady, Citation2005; Wilson et al., Citation2001). Although links can be established on different levels and through diverse approaches—for example, through the integration of coursework and fieldwork –, the major gap between theoretical study and teaching practice can be identified at the transition when teachers enter the professional career after academic learning at higher education institutions (Tatto et al., Citation2020). Teachers may experience it as a ‘sink or swim’ process with practice shock or even drop out as consequence (Stokking et al., Citation2003). The way graduates from teacher education at higher education institutions are successful in entering teaching practice (either through induction or as in-service teacher directly) indicates the effectiveness of a teacher education programme and therefore provides insight into the quality provided in higher education (König et al., Citation2024; Blömeke et al., Citation2011).

Research on Teacher knowledge acquisition and development

Many preservice teachers worldwide experience the transitional process from preservice training to teaching as particularly challenging (Wanzare, Citation2007). The ‘practice shock’ has been described as ‘the disorienting and sometimes traumatic identity crisis that often occurs during the first year of teaching’ (Delamarter, Citation2015). As novice teachers, they usually lack routines and expert teachers’ knowledge structure (Berliner, Citation2004; Stigler & Miller, Citation2018), for example, making it difficult for them to adapt their teaching strategies to students’ needs (König et al., Citation2020) or to master classroom management challenges in terms of disruptive behaviour of students (Jones, Citation2006). Novice teachers, such as preservice teachers during induction, often apply a less-adaptive, recipe-like teaching style (Chizhik & Chizhik, Citation2018; Wolff et al., Citation2021). Most likely, they experience difficulties in considering the instructional context, in anticipating typical classroom events, and generating quick and effective decisions during the teaching process. Besides teaching requirements, other responsibilities such as educational responsibility for a class may set early beginners under pressure when entering the profession (Perrone et al., Citation2019).

Building on the research on teacher expertise and teacher cognition, teacher knowledge itself has increasingly become a research area of considerable interest (Gitomer & Zisk, Citation2015), also as a relevant outcome of initial teacher education programmes (König et al., Citation2024; Darling-Hammond & Bransford, Citation2007; König et al., Citation2022; König, Lammerding, et al., Citation2016; Tatto, Citation2021). In 2008, the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) carried out the Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M), building their analysis on representative samples in 17 countries worldwide (Tatto et al., Citation2012). For the first time, preservice teachers’ knowledge was assessed directly using standardised tests, but also data was collected to look at the opportunities to learn (OTL) the preservice teachers had been exposed to during their preparation. TEDS-M analysed the link between learning opportunities and the preservice teachers’ professional knowledge at the end of their training (Blömeke et al., Citation2011; Schmidt et al., Citation2011).

Undoubtly, TEDS-M has proliferated outstanding findings on the preservice teachers’ knowledge acquisition in higher education. As a survey with one occasion of measurement, effects on the assessed knowledge are based on cross sectional data only, though. There is the need for higher education research building on longitudinal assessment data, which would allow the modelling of long-term learning gains towards the knowledge acquired by the preservice teachers (Rowan et al., Citation2015). Therefore, with the present study, we draw on a sample of four measurement occasions of teachers from Germany and Austria whose GPK was tested using the TEDS-M test at the entrance to their teacher preparation programme in 2011 every two years after (2013, 2015, 2017).

The present study: teachers’ development of GPK in Austria and Germany

The current study was conducted at several universities and pedagogical training institutions in Austria and Germany. Germany is a country with a specific teacher education structure. Programmes encompass two phases, namely a theoretical one at higher education institutions, followed by a practical phase that serves as induction (Terhart, Citation2019). After graduation from one of the academic programmes at German universities, preservice teachers enter their second phase of initial teacher education with a duration of 1.5 years. During induction, preservice teachers work part-time at schools, but they also attend methods courses in small, government-operated teacher education institutions. This practical phase contains a certification process called State Examination: Preservice teachers undergo a practical performance assessment, with two lessons they are required to teach followed by an oral examination.

Austria, although linguistically and culturally very close to Germany, has a different teacher education structure (Hollenstein et al., Citation2020). At the time we conducted our study, teacher training colleges offered teacher education programmes that did not differentiate into two phases due to a short initial teacher training (three years), with graduates being fully certified to enter professional teaching as in-service teachers. Therefore, the challenges preservice teachers experience during induction in Germany should be observable in early career teachers in Austria as well.

Teacher education programmes provided by universities in Germany and teacher training colleges in Austria comprise practical learning opportunities, often denoted as practicum (Hollenstein et al., Citation2020; Terhart, Citation2019). However, as responsibility for professional teaching does not start before induction in Germany or early career teaching in Austria (Arnold et al., Citation2014), in the current study we focus on the transition that the graduates from higher education have to face when commencing to be in charge of teaching as the real challenge of professionalisation.

Research questions and hypotheses

In this article, we focus on two research questions:

Does the transition from higher education into teaching practice supports teachers further development of GPK?

Do institutional factors (opportunities to learn) and individual factors (entrance characteristics of students) predict teacher GPK development at the transition?

For the German-speaking countries, but even internationally, it has been stated coherence of curricula is necessary for improving teacher education (Flores et al., Citation2014; Richmond et al., Citation2019). We therefore focus on the development of knowledge at the transition from higher education into teaching practice. We assume coherence should be significantly endangered at the major transition point when preservice teachers graduate from university or teacher training colleges and enter induction (German) or in-service teaching directly (Austria). Taking Germany and Austria as educational contexts under study, we hypothesise (H1) that teachers acquire pedagogical knowledge in the course of academic learning at university or teacher training colleges, but after that such a development does not necessarily continue in the same way. Instead, teacher knowledge may change, due to transformation of the teacher knowledge structure or even because knowledge acquired in the academic context turns out to be ‘inert knowledge’, that means, knowledge representing information that the teacher can express but not use in practical setting (Renkl et al., Citation1996). As clear evidence exists that entrance characteristics (individual factors) as well as institutional factors are relevant predictors for educational success, we hypothesise that they influence such a transition and therefore may lead to differential development in teacher knowledge (H2).

Method

Sampling design

The data set derives from the comparative study EMW (Entwicklung von berufsspezifischer Motivation und pädagogischem Wissen in der Lehrerausbildung [Change of Teaching Motivations and Acquisition of Pedagogical Knowledge duringInitial Teacher Education], funded by the Rhine-Energy-Foundation Cologne, Germany, Project number W-13-2-003 and W-15-2-003). With the support of a network of research partners, preservice teacher cohorts who started in winter term 2011 were sampled at four time points (T1: Autumn 2011, T2: Autumn 2013, T3: Autumn 2015, T4: Autumn 2017). A total of 4,402 student teachers in Germany and 1,585 in Austria from 30 universities/teacher training colleges were sampled at the first time point, representing a population of about 47,000 preservice teachers at the beginning of their teacher education (König et al., Citation2013). In the institutions of the research partners, student teachers were surveyed during compulsory lectures thus preventing self-selection during participation. The panel sample used in the analysis comprises the subsample that could be followed up at three more time points in 2013, 2015, and 2017. Several drop outs occurred during these years resulting in a sample used in the analyses of the present article.

Dropout analysis

Although during data collection considerable effort was made to reach panellists, substantial dropout occurred during longitudinal data collection. The main reasons were that whole institutions stopped participating in our study for organisational reasons, no central lectures existed to reach potential panellists again, and difficulties occurred when contacting preservice teachers via email who had graduated and entered teaching and were therefore broadly spread out at numerous schools. As a result, the number of panellists was reduced by around two-thirds each time point, respectively.

In order to examine for possible selection bias, we carried out analyses separately for the German and Austrian sample. Based on the sample of the first occasion the participation in the fourth occasion was predicted using binary regression analyses. We included the background variables age and gender, the entrance characteristics variable grade point average (GPA) and the scale intrinsic value from the FIT-Choice instrument measuring factors influencing teaching as a career (H. M. G. Watt & Richardson, Citation2008). provides sample characteristics and findings from the dropout analysis. They hardly indicate differences between the panel sample and the dropout sample at the first time point. Only in the Austrian sample, age and GPA are significant (p < .05), indicating a slight selection towards younger study participants with better GPA. The results therefore do not point to a strong selection bias related to study variables. However, due to the reduction in sample size, generalisability of the sample is limited.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Instruments

General pedagogical knowledge (GPK) of (preservice) teachers was directly assessed using a standardised test that originally had been developed in the context of TEDS-M (König et al., Citation2011). The test conceptualises GPK with relation to teaching as the core challenge of teachers and therefore defines instructional requirements teachers have to fulfill as content dimensions (see ): dealing with heterogeneous learning groups (adaptivity in teaching), structuring lessons, motivating students as well as managing the classroom effectively, and assessing students. In TEDS-M, several pilot studies and expert reviews had been conducted to develop test items that could be applied in various country contexts (König et al., Citation2011). Moreover, in previous studies, we conducted in-service teacher surveys in Germany and Austria providing evidence of prognostic validity of the assessed in-service teachers’ GPK for their instructional quality and student learning (König et al., Citation2022; König & Pflanzl, Citation2016).

Table 2. Dimensions and topics covered by the GPK test.

The GPK test in the present study comprises 30 complex test items. Besides test content dimensions as outlined in , test items relate to one of three cognitive processes that come to the foreground when preservice teachers respond to the single item. They are required to recall knowledge (recall), to provide a more profound understanding or to analyse a concept or phenomenon (understand/analyze), or to generate fruitful strategies to solve a typical problem represented to them via a short text vignette (generate). contains item examples illustrating the different kind of test items.

Table 3. Item examples from the GPK test.

The measurement approach of the GPK test used in the present study allows a comprehensive assessment of pedagogical teacher competence, as specific reviews of the instrument may show (Leijen et al., Citation2022; Voss et al., Citation2015). In particular, the test is not limited to measuring declarative knowledge through single choice test items, but it also comprises complex open response test items with the cognitive demand of generating (see ) that relate to a teacher’s reflection (Schön, Citation1983), which in turn is a typical prompt for inquiry into teaching (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation2009, p. 41).

Open response items were coded on the basis of the TEDS-M coding manual. Double coding of around 20% test booklets resulted in an average consistency MKappa = .78, SDKappa = .03, which is good (Fleiss & Cohen, Citation1973). We carried out IRT scaling analyses using the Software package Conquest (Wu et al., Citation1997). First, we scaled the test for each occasion of measurement separately. As findings provided evidence of reliable measures, we then did concurrent model scaling, which means we included all cases from all occasions of measurement into one data set to increase the analytical power (Bond & Fox, Citation2007). Test data were analysed in the one dimensional Rasch model (one parameter model). Reliability was good (EAP = .87). Scaling analysis indicated good discrimination of items (M = .37, SD = .14; Min = .11, Max = .65). The weighted mean square (WMSQ; Wu et al., Citation1997) of items was in an appropriate range (.80 < WMSQ < 1.20; Bond & Fox, Citation2007) with one item exceeding the critical WMSQ of 1.20, which, however, was kept for theoretical reasons.

Data on entrance characteristics of study participants were collected during the survey in 2011 when they entered initial teacher education. Besides GPA as the key factor governing entrance to initial teacher education programmes (König, Citation2020), we used the FIT-Choice scale inventory developed by H. M. G. Watt and Richardson (Citation2008; Factors Influencing Teaching as a Career Choice). The FIT-Choice model builds on expectancy-value theory and the international state of research on future teachers’ motivations for choosing teaching as a career. It comprises several factors that specifically influence future teachers’ decision to become a teacher. After preliminary analyses of our data, it turned out that only ‘Intrinsic Value’ was an essential factor being correlated with our data. Intrinsic teaching motivations are considered to be ‘the main focus of several models in the motivation literature’ (Richardson & Watt, Citation2014, p. 5) and are ‘emphasized as major influences within the expectancy-value framework’ (p. 8). Numerous empirical studies have shown that in many countries worldwide, including Germany and Austria, ‘Intrinsic Value’ are among the highest-rated motivations for choosing teaching as a career (Rothland Citation2014 ; Richardson & Watt, Citation2014; H. M. G. Watt et al., Citation2012). As a general indicator, it serves as important predictor for the learning situation at university (Schiefele & Urhahne, Citation2000). This confirms our focus on the selection of this motivational factor in the present analyses.

Opportunities to learn were captured using a scale inventory that was developed by König et al. (Citation2017) on the basis of national standards in Germany (KMK [Standing Conference of the (State) Ministers for Education and Culture] Citation2004/2019) that guide the curriculum design for pedagogy in initial teacher education. In Austria, the curriculum is designed in a similar way, with reference to the German national standards and other sources (Schrittesser, Citation2012). The standards indicate four topic areas in pedagogy: instruction, support of students’ social and moral development, assessment, and school development. However, since the wording of these standards are not very specific, the scale inventory developed by König et al. (Citation2017) represents only a selection of relevant topic aspects that could be used for measuring opportunities to learn in pedagogy. To assure content validity of the scale inventory, expert reviews among teacher educators were conducted in Germany and Austria with sufficient agreement on the curricular significance of the topic selection. In total, 37 items require preservice teachers to indicate whether or not they have ever studied the relevant topic, and they have to answer with ‘Yes’ (coded as 1) or ‘No’ (coded as 0). For more details on the scale inventory and item examples, see the documentation by König et al. (Citation2017). In the following, we use survey teacher data on opportunities to learn from the time point before teachers’ graduating from higher education institutions (2013 in Austria, 2015 in Germany, see ).

Missing data and multilevel analyses

For all n = 191 (preservice) teachers a complete data set was obtained by ML estimation of the missing observations (MAR) and using the auxiliary information (other than the variables included in the analyses) available from the (preservice) teachers. Multiple imputation was considered for the missing observations. However, for ease of presentation, the results presented here are based on a single imputation of the missing observations, which show no substantial difference from the multiple imputation results.

For the analyses, a multilevel approach to repeated measures was used, consisting of two piece-wise linear regressions for the GPK before the transition to teaching practice and after the transition, respectively. The advantage to this approach is that the transition from higher education into teaching practice can be quantified by a single parameter (γ01) that expresses the difference in GPK between the two regressions at the point of transition, while taking into account that the transition occurs between two different measurement occasions for the German and Austrian preservice teachers ().

For H1, a multilevel model is specified to estimate the effect of the transition from higher education into teaching practice (as expressed by the parameter γ01). For H2, this model is extended with individual-level and institutional factors to investigate potential factors that moderation the transition into teaching practice. Appendix A (Electronic Supplementary Material) provides details of the models used for our analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics of the GPK test shows that there is a statistically significant increase of test scores (Logit-scale) during initial teacher education which clearly indicates preservice teacher acquire GPK (). However, after graduation from higher education, which happened between 2013 and 2015 in Austria and between 2015 and 2017 in Germany, this knowledge growth does not continue. Remarkably, as higher education takes longer in Germany than in Austria, preservice teachers in Germany had a better chance to acquire a higher level of GPK in 2015. However, after graduation, similar discontinuity of GPK can be observed.

Findings from multilevel analyses

shows the results of the analyses related to H1 (details of the parameters and the models can be found in Appendix A). The results show that the inclusion of the country specific effects in the extended model provides a substantial improvement in model fit, compared to the basic model ( = 37.042, p < 0.01). Moreover, we find a substantial and significant effect related to the transition from academic learning into teaching practice (γ01 = −0.334, p < 0.05) on teachers’ knowledge. That is, according to the extended model, on average, GPK is expected to drop by one-third of a standard deviation during the transition to teaching practice.

Table 4. Parameter estimates multilevel models related to H1.

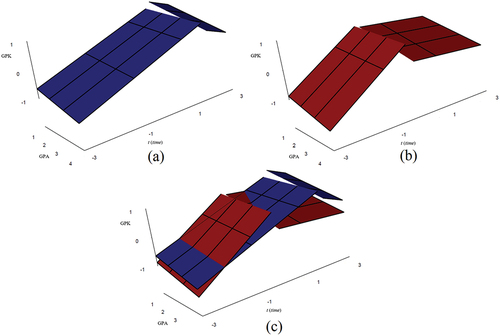

For the second hypothesis, we look for individual and institutional factors that may moderate the observed drop in GPK during the transition to teaching practice. The second column in shows the results of Model 1, whereby both the main effect of the grade point average (GPA) upon entering the study, as its interaction with Bit (transition variable) on GPK are included. The results show that the inclusion of GPA reduces the gap associated with the transition into teaching practice. More specifically, the interaction effect (Bit = −0.172, p < 0.05) shows that a higher GPA is associated with a smaller gap when transitioning to teaching practice.

Table 5. Parameter estimates models related to hypothesis 2.

The inclusion of interactions of the transition with other factors did not show any significant contributions to the model.Footnote1 However, two main effects of factors were found to be related to GPK: Intrinsic Value (IV) as a factor influencing teaching as a career choice (entrance characteristic) and opportunities to learn (OTL) in pedagogy (surveyed before graduating from higher education). The inclusion of these main effect resulted in the final model, as shown in the last column of .

For illustration, shows the surface plots for the expected GPK across t (time) and GPA, under the final model for the a) German preservice teachers, b) Austrian (preservice) teachers, and c) both plots combined. We included GPA into due to its significant interaction effect with the gap variable. Note that, for German preservice teachers with a low GPA (high proficiency), there is actually a relative large positive gap (increase in GPK) in going from academic learning into teaching practice.

Discussion

The present study used a longitudinal data set, comprising four time points with direct assessments of teachers’ GPK. Surveyed first at their entrance into initial teacher education, they had been followed up through graduating from higher education until entering the teaching profession in Austria and induction in Germany. In analysing this rich dataset, the study’s aim was to proliferate empirical findings that would provide insights into teachers’ development of professional knowledge in particular, at the transition from higher education into teaching practice. Such a development can be framed by the discussion on the relationship between theory and practice in teacher education, thus contributing to a controversy in the literature that has rarely been supported by empirical data yet (Lawson et al., Citation2015). With the investigation of teachers’ transition in Austria and Germany as two structurally different, but comparable teacher education systems, the study also aimed at identifying a pattern of teacher knowledge development that would take place across countries.

Transition from higher education into teaching practice

For both country contexts, evidence was provided that preservice teachers acquire GPK in the time span between entering initial teacher education and graduating from higher education. This is an important finding about the countries’ ‘teacher education effectiveness’ (König et al., Citation2024; Blömeke et al., Citation2011), since for decades, severe doubts have been stated about the role of general pedagogy in teacher education. For example, claims about its uselessness as well as about what preservice teachers need to know at the end of their training have been made and linked with requests either to eliminate opportunities to learn in pedagogy or to structure it in a new way (P. L. Grossman, Citation1992; Kagan, Citation1992). The development and implementation of national standards in Austria and Germany was clearly a response to this issue, with the aim to enhance general pedagogy in teacher education and increasing its mandatory status as a curricular component (Terhart, Citation2019). Until today, hardly any rigorous assessments have been conducted to examine whether requirements indicated by those standards have actually been fulfilled (König, Citation2020). Therefore, the findings presented here showing the increase of GPK in the course of initial teacher education in higher education institutions in Germany and Austria may enrich the discourse about standards in teacher education and what preservice teachers should know at the end of higher education. As mentioned before, predictive validity of the GPK test has been provided in previous studies with in-service teachers and measures for instructional quality they delivered to students in Austria (König & Pflanzl, Citation2016) and Germany (Blömeke et al., Citation2021). This serves as an important justification for claiming relevance of the knowledge looked at in the present study.

Longitudinal findings we presented here may provide evidence for ‘programme evaluation’, but the question arises how teacher education programmes can be validated (Galluzo & Craig, Citation1990). There is the general need to connect research on teacher education and research on teaching (P. Grossman & McDonald, Citation2008; Kaiser & König, Citation2019). We therefore looked at the ongoing GPK development of the graduates, thus going beyond initial teacher education. As expected with H1, the transition after graduation leads to a knowledge drop. As soon as preservice teacher have graduated, they seem to fall back into a kind of comfort zone in which the increase of GPK, on average, does not continue.

Moderation of individual and institutional factors

To analyse possible explanations for the knowledge drop after graduating from higher education, we tested both entrance characteristics and learning opportunities as possible individual and institutional factors that might lead to differential effects and thus prevent the discontinued knowledge growth at the transition point. As expected with H2, GPA, intrinsic teaching motivations, and learning opportunities in pedagogy turned out to significantly predict the development. Taking GPA as example, we illustrated the effect in using surface plots. The transition point appears like tectonic plates (): The higher the proficiency as indicated by GPA, the more successful graduates manage in continuing their GPK development even after higher education. That the GPA of teachers does play a significant role even after graduating from higher education corresponds to the state of research on the predictive validity of GPA in higher education and beyond (Schneider & Preckels, Citation2017).

Although we did not include further variables in our analyses to test for alternative predictors, some more explanations are worth consideration. First, graduates just might forget what they have learned during higher education. For example, if they acquired GPK on short notice before higher education examinations, teachers may have difficulties in recalling it later from long-term memory. Second, teaching practice might offer views that are concurrent to scientific knowledge. The graduates now are required to adapt to a community of teaching practice and may dissociate themselves from academic thinking (Chitpin et al., Citation2008; Munby et al., Citation2001). Finally, although agreement exists that professional teacher knowledge is a relevant source for the individual teacher, this does not guarantee that every practicing teacher makes an effort to update his or her professional knowledge accordingly. In particular early career teaching can be overwhelming for graduates. Teachers entering teaching practice may primarily use their previous experience and knowledge for problem solving when they are committed to mastering teaching requirements. This kind of ‘usual routine of solving problems’ has been denoted as ‘knowledge stagnation’ (Schmidt et al., Citation2011).

Limitations

Although hardly any differences in study variables could be found between dropout and panel, the considerable number of participants we lost in the course of conducting longitudinal data collection is clearly a limitation, also since sample size has substantially decreased. With less than 200 longitudinal participants, the generalisability is limited and the findings of the present analyses have to be interpreted with caution. Future research should make an effort to create larger longitudinal samples with higher response rates.

Implications and suggestions for further research

To the best of our knowledge, longitudinal data analyses on the teacher knowledge acquisition and development during both initial teacher education and entering teaching practice is very scarce (see the recent synthesis of literature reviews by König et al., Citation2024). As a consequence, theoretical assumptions about knowledge growth of teachers during their higher education career and beyond have hardly been tested. There is a critical discussion that higher education institutions have been carrying out numerous teacher education reforms without any support of empirical data (Larcher & Oelkers, Citation2004; Terhart, Citation2019). But data on teachers acquisition of knowledge would also support the creation of evidence-based theories on the process of professionalisation during teacher education, which are still lacking (König & Blömeke, Citation2020). Future research should continue longitudinal data approach as suggested by the present study. This would enrich the state of research on expert-novice comparisons that mainly rely on comparisons of cohorts (e.g. Kleickmann et al., Citation2013).

Conclusion

The present study’s findings demonstrated evidence that preservice teachers in Austria and Germany acquire GPK during initial teacher education, which also indicates effectiveness of the specific teacher education programmes and systems (König et al., Citation2024). However, as broadly discussed in the literature, this development does not continue further at the transition from higher education into teaching practice. Higher education impact seems to be limited after graduation. As GPA, intrinsic teaching motivations, and learning opportunities in pedagogy turned out in significantly predicting the development, findings should contribute to discussions about individual cognitive und motivational prerequisites of student teachers at the entrance to teacher education and the design of pedagogy as curriculum component in teacher education programmes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2024.2308895

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In additional analyses, we examined a number of further variables such as all FIT-Choice model factors other than intrinsic value. However, no significant effect could be observed. As these entrance characteristics do not belong to our primary research focus in the present analyses, we decided against presenting these non-significant findings in the present paper.

References

- Arnold, K.-H., Gröschner, A., & Hascher, T. (Eds.), (2014). Schulpraktika in der Lehrerbildung: Theoretische Grundlagen, Konzeptionen, Prozesse und Effekte. Waxmann. (Pedagogical field experiences in teacher education: Theoretical foundations, programmes, processes, and effects).

- Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109348479

- Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documenting the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 24(3), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467604265535

- Blömeke, S., Suhl, U., & Kaiser, G. (2011). Teacher education effectiveness: Quality and equity of future primary teachers’ mathematics and mathematics pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110386798

- Blömeke, S., Jentsch, A., Schlesinger, L., Felske, C., Musekamp, F., & Kaiser, G. (2021). The links between pedagogical competence, instructional quality, and mathematics achievement in the lower secondary classroom. Educational Studies in Mathematics.

- Bond, T., & Fox, C. (2007). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Chitpin, S., Simon, M., & Galipeau, J. (2008). Pre-service teachers’ use of the objective knowledge framework for reflection during practicum. Teaching and Teacher Education, 12(8), 2049–2058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.04.001

- Chizhik, E., & Chizhik, A. (2018). Value of annotated video-recorded lessons as feedback to teacher-candidates. Journal of Technology & Teacher Education, 26(4), 527–552.

- Clift, R. T., & Brady, P. (2005). Research on methods courses and field experiences. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education. The report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher education (pp. 309–424). Erlbaum.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Teacher research as stance. In S. E. Noffke & B. Somekh (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Educational Action Research (pp. 39–49). Sage Publications.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (2007). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. John Wiley & Sons.

- Delamarter, J. (2015). Avoiding practice shock: Using teacher movies to realign pre-service teachers’ expectations of teaching. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n2.1

- European Commission. (2013) . Supporting teacher competence development for better learning outcomes. European Commission Education and Training UE.

- Fleiss, J. L., & Cohen, J. (1973). The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33(3), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447303300309

- Flores, M. A. (2016). Teacher education curriculum. In J. Loughran & M. L. Hamilton (Eds.), International handbook of Teacher education (pp. 187–230). Springer.

- Flores, M. A., Santos, P., Fernandes, S., & Pereira, D. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ views of their training: Key issues to sustain quality teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 16(2), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.2478/jtes-2014-0010

- Galluzo, G. R., & Craig, J. R. (1990). Evaluation of Preservice Teacher Education Programs. In R. W. Housten (Ed.), Handbook of research on Teacher education (pp. 599–616). Mac-Millan.

- Gitomer, D. H., & Zisk, R. C. (2015). Knowing what teachers know. Review of Research in Education, 39(1), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X14557001

- Grossman, P. L. (1992). Why models matter: An alternate view on professional growth in teaching. Review of Educational Research, 62(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062002171

- Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009). Redefining teaching, re‐imagining teacher education. Teachers & Teaching Theory & Practice, 15(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875340

- Grossman, P., & McDonald, M. (2008). Back to the future: Directions for research in teaching and teacher education. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 184–205. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312906

- Hollenstein, L., Brühwiler, C., & Biedermann, H. (2020). Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung an Universitäten und Pädagogischen Hochschulen. [Teacher education at universities and teacher training colleges. In J. C Cramer (Ed.), Handbuch Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung (Vol. 37, pp. 323–331). Klinkhardt/UTB.

- Jones, V. (2006). How do teachers learn to be effective classroom managers? In C. M. Evertson & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 887–907). Erlbaum.

- Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62(2), 129–169. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062002129

- Kaiser, G., & König, J. (2019). Competence measurement in (mathematics) Teacher education and beyond: Implications for policy. Higher Education Policy, 32, 597–615.

- Kleickmann, T., Richter, D., Kunter, M., Elsner, J., Besser, M., Krauss, S., & Baumert, J. (2013). Teachers’ content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge: The role of structural differences in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487112460398

- KMK [Standing Conference of the (State) Ministers for Education and Culture]. (2004/2019). Standards für die Lehrerbildung: Bildungswissenschaften. Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 16.12.2004 [Standards for teacher education: Education sciences. Resolution of the Standing Conference of 16.12. 2004, updated 2019]. Berlin, Germany: KMK.

- König, J. (2020). Beurteilung und Zertifizierung von (angehenden) Lehrerinnen und Lehrern. In C. Cramer, J. König, M. Rothland, & S. Blömeke. Eds., Handbuch Lehrerinnen- und LehrerbildungVol. 44 pp. 376–384. Klinkhardt/UTB.

- König, J., & Blömeke, S. (2020). Wirksamkeits-Ansatz in der Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung. In C. Cramer, J. König, M. Rothland, & S. Blömeke. Eds., Handbuch Lehrerinnen- und LehrerbildungVol. 20 pp. 172–178. Klinkhardt/UTB.

- König, J., Blömeke, S., Paine, L., Schmidt, B., & Hsieh, F.-J. (2011). General pedagogical knowledge of future middle school teachers. on the complex ecology of teacher education in the United States, Germany, and Taiwan. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 188–201.

- König, J., Bremerich-Vos, A., Buchholtz, C., Fladung, I., & Glutsch, N. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ generic and subject-specific lesson-planning skills: On learning adaptive teaching during initial teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(2), 131–150.

- König, J., Bremerich-Vos, A., Buchholtz, C., Lammerding, S., Strauß, S., Fladung, I., & Schleiffer, C. (2017). Modelling and validating the learning opportunities of preservice language teachers: On the key components of the curriculum for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 394–412.

- König, J., Doll, J., Buchholtz, N., Förster, S., Kaspar, K., Rühl, A.-M., Strauß, S., Bremerich-Vos, A., Fladung, I., & Kaiser, G. (2018). Pädagogisches Wissen versus fachdidaktisches Wissen? Struktur des professionellen Wissens bei angehenden Deutsch-, Englisch- und Mathematiklehrkräften im Studium. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 21(3), 1–38.

- König, J., Hanke, P., Glutsch, N., Jäger-Biela, D., Pohl, T., Becker-Mrotzek, M., Schabmann, A., & Waschewski, T. (2022). Teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy: Conceptualization, measurement, and validation. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 34, 483–507.

- König, J., Heine, S., Kramer, C. H., Weyers, J., Becker-Mrotzek, M., Großschedl, J., Hanisch, C. H., Hanke, P., Hennemann, T. H., Jost, J., Kaspar, K., Rott, B., & Strauß, S. (2024). Teacher education effectiveness as an emerging research paradigm: A synthesis of reviews of empirical studies published over three decades (1993-2023). Journal of Curriculum Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2023.2268702

- König, J., Lammerding, S., Nold, G., Rohde, A., Strauß, S., & Tachtsoglou, S. (2016). Teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching English as a foreign language: Assessing the outcomes of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(4), 320–337.

- König, J., & Pflanzl, B. (2016). Is teacher knowledge associated with performance? On the relationship between teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge and instructional quality. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 419–436.

- König, J., Rothland, M., Darge, K., Lünnemann, M., & Tachtsoglou, S. (2013). Erfassung und Struktur berufswahlrelevanter Faktoren für die Lehrerausbildung und den Lehrerberuf in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 16(3), 553–577.

- Korthagen, F. A. (2001). Linking practice and theory: The pedagogy of realistic teacher education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Korthagen, F. A. J. (2010). How teacher education can make a difference. Journal of Education for Teaching, 36(4), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2010.513854

- Korthagen, F. A. J., & Kessels, J. P. (1999). Linking theory and practice: Changing the pedagogy of teacher education. Educational Researcher, 28(4), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1176444

- Larcher, S., & Oelkers, J. (2004). Deutsche Lehrerbildung im internationalen Vergleich. In S. Blömeke, P. Reinhold, G. Tulodziecki, & J. Wildt (Eds.), Handbuch Lehrerbildung (pp. 128–150). Klinkhardt.

- Lawson, T., Çakmak, M., Gündüz, M., & Busher, H. (2015). Research on teaching practicum–a systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 392–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.994060

- Leijen, Ä., Malva, L., Pedaste, M., & Mikser, R. (2022). What constitutes teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge and how it can be assessed: A literature review. Teachers & Teaching, 28(2), 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2022.2062710

- Munby, H., Russell, T., & Martin, A. K. (2001). Teachers’ knowledge and how it develops. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (4th ed., pp. 877–904). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

- Nelson, M. J., & Voithofer, R. (2022). Coursework, field experiences, and the technology beliefs and practices of preservice teachers. Computers & Education, 186, 104547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104547

- Perrone, F., Player, D., & Youngs, P. (2019). Administrative climate, early career teacher burnout, and turnover. Journal of School Leadership, 29(3), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052684619836823

- Renkl, A., Mandl, H., & Gruber, H. (1996). Inert knowledge: Analyses and remedies. Educational Psychologist, 31(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3102_3

- Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. G. (2014). Why people choose teaching as a career. An expectancy-value approach to understanding Teacher motivation. In P. W. Richardson, S. A. Karabenick, & H. M. G. Watt (Eds.), Teacher motivation. Theory and practice (pp. 3–19). Routledge.

- Richmond, G., Bartell, T., Carter Andrews, D. J., & Neville, M. L. (2019). Reexamining coherence in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 188–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119838230

- Rothland, M. (2014). Warum entscheiden sich Studierende für den Lehrerberuf? Berufswahlmotive und berufsbezogene Überzeugungen von Lehramtsstudierenden [Why decide students to become a teacher? Teaching motivations and beliefs of student teachers]. In E. Terhart, H. Bennewitz, & M. Rothland (Eds.), Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf [Handbook on research on teachers] (2nd Ed. ed., pp. 319–348). Waxmann.

- Rowan, L., Mayer, D., Kline, J., Kostogriz, A., & Walker-Gibbs, B. (2015). Investigating the effectiveness of teacher education for early career teachers in diverse settings: The longitudinal research we have to have. The Australian Educational Researcher, 42(3), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-014-0163-y

- Schiefele, U., & Urhahne, D. (2000). Motivationale und volitionale bedingungen der studienleistung [motivational and volitional determinants of academic performance. In U. Schiefele & K.-P. Wild (Eds.), Interesse und Lernmotivation. Untersuchungen zur Entwicklung, Förderung und Wirkung (pp. 183–205). Waxmann.

- Schmidt, W. H., Cogan, L., & Houang, R. (2011). The role of opportunity to learn in teacher preparation: An international context. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110391987

- Schneider, M., & Preckels, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner – how professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Schrittesser, I. (2012). Organisation der Lehrerbildung in Österreich: Modelle und Empfehlungen. In Ö. Wissenschaftsrat (Ed.), Lehren lernen – die Zukunft der Lehrerbildung (pp. 115–130). ÖWR.

- Shulman, L. S. (1998). Theory, practice, and the education of professionals. The Elementary School Journal, 98(5), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1086/461912

- Stigler, J. W., & Miller, K. F. (2018). Expertise and expert performance in teaching. In A. Ericsson, R. R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, & A. M. Williams (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (2nd edition ed., Vol. 24, pp. 431–452). Cambridge University Press.

- Stokking, K., Leenders, F., De Jong, J., & van Tartwijk, J. (2003). From student to teacher: Reducing practice shock and early dropout in the teaching profession. European Journal of Teacher Education, 26(3), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261976032000128175

- Tatto, M. T. (2021). Professionalism in teaching and the role of teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1849130

- Tatto, M. T., Peck, R., Schwille, J., Bankov, K., Senk, S. L., Rodriguez, M., & Rowley, G. (2012). Policy, Practice, and Readiness to Teach Primary and Secondary Mathematics in 17 Countries: Findings from the IEA Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M). In International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. Amsterdam.

- Tatto, M. T., Rodriguez, M. C., & Reckase, M. (2020). Early career mathematics teachers: Concepts, methods, and strategies for comparative international research. Teaching and Teacher Education, 96, 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103118

- Terhart, E. (2019). Teacher education in Germany. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.377

- Voss, T., Kunina-Habenicht, O., Hoehne, V., & Kunter, M. (2015). Stichwort Pädagogisches Wissen von Lehrkräften: Empirische Zugänge und Befunde. [Teachers’ pedagogical knowledge: Empirical approaches and findings]. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 18(2), 187–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-015-0626-6

- Wanzare, Z. O. (2007). The Transition Process: The Early Years of Being a Teacher. In T. Townsend & R. Bates (Eds.), Handbook of Teacher Education (pp. 343–364). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2008). Motivations, perceptions, and aspirations concerning teaching as a career for different types of beginning teachers. Learning and Instruction, 18(5), 408–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.002

- Watt, H. M. G., Richardson, P. W., Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Beyer, B., Trautwein, U., & Baumert, J. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: An international comparison using the FIT-Choice scale. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(6), 791–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.03.003

- Wilson, S., Floden, R., & Ferrini-Mundy, J. (2001). Teacher preparation research: Current knowledge, gaps, and recommendations. Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy, University of Washington.

- Wolff, C. E., Jarodzka, H., & Boshuizen, H. P. (2021). Classroom management scripts: A theoretical model contrasting expert and novice teachers’ knowledge and awareness of classroom events. Educational Psychology Review, 33(1), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09542-0

- Wu, M. L., Adams, R. J., & Wilson, M. R. (1997). ConQuest: Multi-aspect test software [computer program]. Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Zeichner, K. M. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college- and university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347671