ABSTRACT

Our study evaluated factors associated with ill-health in a population-based longitudinal study of women who delivered a singleton live-born baby in a 3-month period across Jamaica. Socio-demographics, perception of health, chronic illnesses, frequency and reasons for hospital admission were assessed. Relationships between ill-health and maternal characteristics were estimated using log-normal regression analysis. Of 9,742 women interviewed at birth, 1,311 were assessed at four stages, 27.7% of whom reported ill-health at least once. Hospitalization rates were 20.9% during pregnancy, 6.1% up to 12 months and 0.5% up to 22 months after childbirth. Ill-health, reported by 11% of women, was less likely with better education (RR=0.62, 95%; 0.42-0.84). Hospital admission was associated with higher socio-economic status (RR=1.33, 95% 1.04-1.70) and Caesarean section [CS] (RR=1.57, 95%; 1.21-2.04). One in three (33.7%) women reported chronic illnesses, and the likelihood increased with age, parity and delivery by elective CS (RR=1.44, 95%; 1.20-1.73). In multivariable analyses, ill-health was more likely with chronic illness (RR=2.06, 95%; CI: 1.71-2.48) and hospital admission from 12 to 22 months after childbirth (RR=1.54, 95% CI: 1.12-2.12). Ill-health during pregnancy and after childbirth represent a significant burden of disease and requires a standardised comprehensive approach to measuring and addressing this disease burden.

Introduction

While maternal mortality has been decreasing in many settings globally, the burden of morbidity or ill-health is significant and may be underestimated, with chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) becoming proportionately more important (Firoz et al., Citation2013). While the causes of maternal deaths have become clearer, the concept and true magnitude of underlying maternal morbidity is poorly understood (Liskin, Citation1992). Much research on maternal morbidity to date has focused on life threatening, severe acute maternal morbidity or ‘maternal near miss’, which has been well defined and usually assessed at secondary or tertiary care levels (Mantel, Buchmann, Rees, & Pattinson, Citation1998; Pattinson, Say, Souza, van den Broek, & Rooney, Citation2009).

In contrast, morbidity which is not immediately life threatening, but experienced as ill-health by the woman during or after pregnancy or noted by her healthcare provider, because it impairs her wellbeing or is associated with adverse perinatal outcome, is less well documented (Zafar, Jean-Baptiste, Rahman, Neilson, & van den Broek, Citation2015). Non-severe maternal morbidity, has been defined as ‘any condition attributed to or aggravated by pregnancy and childbirth which has a negative impact on the woman’s wellbeing and functioning’ (Firoz et al., Citation2013). This is in line with the concept of health as ‘a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (World Health Organization, Citation2015). To date, there is little information, regarding how women perceive or report ill-health during pregnancy and after childbirth, especially in low-and middle-income countries (LMIC) where the burden of disease is expected to be highest.

In Australia, women were asked 2–4 weeks after childbirth to rate their health as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. When responses were collapsed into a dichotomous variable of better (excellent, very good, good) or worse (fair, poor), 4.0% perceived their health as worse. This negative rating was associated with financial and social challenges and emotional distress (Morgan & Eastwood, Citation2014). In Lebanon, 13.1% of women rated their health as poor after childbirth (Abdulrahim & El Asmar, Citation2012). A multi-country study of 11,454 women across four LMIC settings found that while most women reported good satisfaction with health and good quality of life, 9.0% had an identified infectious disease (HIV, malaria, syphilis, chest infection or tuberculosis), 47.9% were anaemic, and 11.5% were diagnosed with other medical or obstetric morbidity. In addition, 25.1% of women screened positive for a psychological morbidity and 36.6% reported social morbidities such as exposure to violence and substance misuse (McCauley et al., Citation2018). Another study of three LMICs found that at least 30% of women suffer some form of morbidity during and after pregnancy (Barreix et al., Citation2018).

The new Sustainable Development Goal three (SDG 3) aims to ‘ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’ and has been associated with a new international priority to ensure that every woman, including pregnant women, have an equal chance not only to ‘survive, but to thrive’ (United Nations, Citation2015; United Nations, World Health Organization, Citation2015). There is a need to understand and document better the health needs of women during, immediately, and more long-term, after pregnancy. Furthermore, it is important to develop methods and tools to comprehensively assess and document health status, and where possible, identify indicators or markers that can be used as proxy measures for the burden of ill-health not considered life-threatening or severe, but which is nevertheless of significance.

Our primary objective was to explore the self-reported health status of women who were assessed during pregnancy, after childbirth and up to 22 months after childbirth, as experienced and reported by women themselves. As a secondary objective we assessed the number and reasons for hospital admission at each stage of pregnancy, the presence of underlying chronic illness, and the effect of socio-economic status (SES) and education on health. Finally, we examined if hospital admissions or presence of chronic illness could be considered proxy indicators for non-severe maternal morbidity.

Materials and methods

Study design

Data on the health status of women during and after pregnancy were collected as part of the second Jamaican Birth Cohort Study (JA KIDS), a population-based observational study to investigate health, developmental and behavioural outcomes for livebirths occurring from July 1–30 September 2011. The methodology of the study is published elsewhere (JA KIDS Citation2019) In brief, mothers of these children were assessed during pregnancy (after 28 weeks gestation) and 24–48 hours after childbirth. Efforts were made to follow up all mothers within 9–12 months of childbirth and a computer generated random sample (35%) was selected for follow-up when the children were 18–22 months old. For the purposes of this study, data relating only to women delivering singleton live births and assessed at all four stages are presented, n = 1,311.

Participation and refusal rates

Most Jamaican women attend four or more antenatal visits (86%), with 99% of births attended by a skilled health attendant (Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Citation2015). Of 11,124 women who delivered a live-born baby between July 1 and 30 September 2011 and who were eligible for the study, 9,742 (87.5%) were assessed within 48 hours of childbirth (5% refusal rate; 7.5% discharged before invitation or too ill to participate). Of these, 4,572 (46.9%) had enrolled during pregnancy. All mothers were interviewed face-to-face using standardized questionnaires by trained interviewers. Questions were mainly closed ended but allowed for recording of options not listed on the schedule.

Socio-demographic variables

Available demographics include age, number of previous pregnancies and educational level were assessed during pregnancy and within 48 hours after childbirth. SES was derived using a durable goods index proxy indicator which incorporates demographic variables such as age, previous pregnancies, education level, and information collected on a range of household items. The process employs principal components analysis to place participants in low, medium or high SES. Such indices are commonly used in LMICs where data describing income tends to be incomplete and/or unreliable (Filmer & Pritchett, Citation2001).

Rating of health status

At birth women were asked to rate their condition on a two-point scale as well (1) or ill (2). During pregnancy and at the two post-childbirth assessments women were asked to rate their health on a five-point scale: excellent (1), very good (2), average (3), fair (4) or poor (5). This latter scale was collapsed to good (1) or poor (2), with a score of ill (2) at birth or fair to poor (4–5) on other occasions considered to represent ill-health (2).

Obstetric and non-obstetric conditions including chronic diseases

Women were asked to respond (yes/no) to a comprehensive listing of health conditions by health systems including: gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, respiratory, haematological, metabolic, neurological, musculoskeletal, psychological, dermatological, immunological, gynaecological and urogenital; and obstetric conditions such as hypertension, haemorrhage, and infections related to pregnancy and childbirth. In addition, women were asked to provide details on any known chronic illnesses at 9–12 and 18–22 months after childbirth.

Admissions to hospital

Women were asked about the number and reason for hospital admission during pregnancy, at 9–12 months (since childbirth) and at 18–22 months after childbirth (since child turned one).

Coding and classification of health conditions and rating of health status

The World Health Organization International Classification of Disease - Maternal Mortality (WHO ICD-MM) classification framework (World Health Organization, Citation2012) was adapted to code the reason for hospital admission as: obstetric (complications related to pregnancy), indirect (non-communicable diseases or infections not related to pregnancy), co-incidental, (intentional or unintentional injuries) or unspecified (not documented). The indirect category was expanded to detail four groups of NCDs (cardio-cerebro-renovascular; haematological and immunological; endocrine and metabolic and other) and two categories of non-obstetric infections (HIV disease and other infections) (McCaw-Binns, Campbell, & Spence, Citation2018). Responses were coded into clinically relevant categories.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS v21 and Stata v12. P-values were derived using likelihood ratio test; a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant and estimates were derived with 95% confidence intervals. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were used. Relative risks were estimated (for the outcomes of ill-health, hospital admission and chronic illness) using univariable log binomial models for binary variables. Ill-health was also analysed using a multivariable log binomial model with hospital admissions and chronic illness as explanatory variables. Variables statistically significant in univariable analyses (p < 0.10) were included in multivariable log-binomial regression analyses.

Results

Of the 9,742 women assessed at least once during or after pregnancy, 79.5% had a normal vaginal birth, 19.4% delivered by caesarean section (CS) (12.3% elective, 7.1% emergency), while less than 0.1% had an instrumental vaginal childbirth. No delivery information was available for 1.4%. Of the 1,311 women assessed at all four stages, their characteristics were similar to those not assessed on all occasions, however those with all four contacts were more likely to have secondary level education or vocational training (). On each follow up occasion (9–12 and 18–22 months) women assessed were less likely to report ill-health than those not assessed (3.0% for those assessed at 9–12 months (p = 0.004) and 2.7% for those assessed at 18–22 months (p = 0.02) compared, with 3.4% at delivery). Further descriptive analyses are confined to these 1,311 women, who were on average 25.9 (±6.6) years, all literate (7% tertiary education), 23% of whom were classified as low and 19% as high SES.

Table 1. Comparison of socio–demographic characteristics for all possible women at each assessment point.

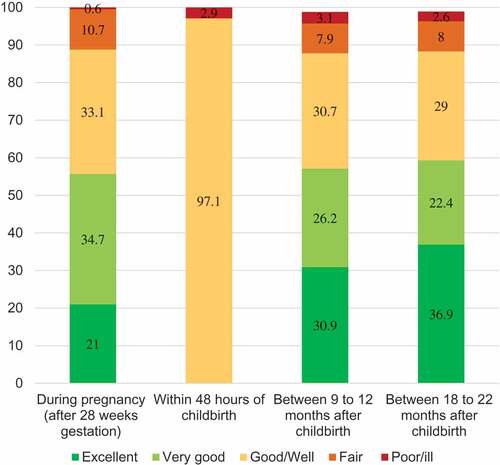

Self-reported health

At each assessment point (n = 1,311), between 55.7% and 59.3% of women reported excellent or very good health while up to 3.1% reported poor or ill–health. Using the collapsed two-point scale, about one in ten women reported feeling either fair or poor/ill during pregnancy (11.3%), at 9–12 months (11.0%) and at 18–22 months (10.6%). At the four time-points during and after pregnancy 73.4% always reported feeling well, with the remainder reporting ill-health on one or more occasion (19.8% reported ill-health during one of the four points, 5.2% for two and 1.5% for three or more assessment points) ().

Hospital admission

Admission to hospital was reported by 20.9% of women during pregnancy, 6.1% in the first year after childbirth and 0.5% in months 12–22 after childbirth, with 31.0% admitted at some point over the two-year review period (). Of the antepartum admissions (n = 349) with details, 274 (78.5%) women were admitted once while 75 (21.5%) required two or more admissions. Of 80 women admitted between childbirth and 9–12 months, 72 (90%) reported one and eight (10%) reported two or more admissions. At 18–22 months, 7 of the 13 women reported just one admission (53.8%). Complications of pregnancy (direct) were the most frequent reason for admissions during pregnancy (68.3%), with 60.8% of these classified as ‘other obstetric complications’ such as threatened preterm labour and pre-labour rupture of membranes ().

Table 2. Prevalence of hospital admission and cause, coded as per adapted WHO ICD-MM framework.

Chronic illness

Women were asked to detail specific chronic illnesses during pregnancy and after childbirth. For the 1,311 women who provided information at all four contact times, similar proportions reported essential hypertension (10.5–9.5%), asthma (4.4–3.2%), diabetes mellitus (1.3–1.0%) and sickle cell anaemia (0.7–0.7%) at the two contacts after childbirth. On both occasions 5.9% of the respondents reported other ‘unspecified conditions’. Women reporting chronic illnesses were older, more likely to have at least one previous pregnancy and to have only completed primary education ().

Table 3. Associations between socio-demographic characteristics, ill-health, hospital admission and chronic illness (n = 1,311).

Associations between hospital admission, chronic illness and ill-health

Ill-health was less likely as education increased (RR = 0.62, 95%; 0.42–0.84). Hospital admission was more likely with a higher SES (RR = 1.33, 95% 1.04–1.70) and delivery by emergency CS (RR = 1.57, 95%; 1.21–2.04). Maternal assessment of any poor health was not predictive of hospital admission in the two years after childbirth. Economically vulnerable women (primary education, low SES) were more likely to report being unwell than women with higher levels of education and SES. Mode of childbirth was not associated with being unwell but correlated with admission for elective (RR 1.48, 95% CI: 1.21–1.81) and emergency CS (RR 1.57, 95% CI: 1.21–2.04). Women reporting chronic illness were more likely to be delivered by elective CS (RR 1.44, 95% CI: 1.20–1.73). At 9–12 and 18–22 months after childbirth, 24.0% and 20.6% of women reported ongoing chronic illness, which was more likely with an increase in age (RR = 2.01 95% CI: 1.41–2.86) and parity (RR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.09–2.04). Ill-health at any time was associated with chronic illness (RR = 2.15, 95% CI:1.81–2.57); and admissions antenatally (RR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.14–1.66), during the first 12 months (RR = 1.54, 95% CI:1.15–2.05) and between 12–22 months (RR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.30–2.54). In multivariable analyses, ill-health was more likely with chronic illness (RR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.71–2.48) and hospital admission from one year to 22 months after birth (RR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.12–2.12) ().

Table 4. Summary of univariable and multivariable analyses of association between ill-health and hospital admission and chronic illness for women assessed at all four assessment stages (n = 1,311).

Discussion

Principal findings

Of the women assessed at four stages during and after pregnancy in Jamaica, at least 10% reported ill-health in at least at one stage, with a minority (3.1%) reporting ill-health at all four stages. Admission was common during pregnancy with one in four women (26.6%) admitted to a hospital, two-thirds for problems related to the pregnancy. After childbirth, hospital admission rates decreased to 6.1% in the first and 0.8% in the second year after childbirth. Overall, one in three women reported a chronic health condition (33.7%), mainly essential hypertension, asthma and diabetes mellitus, with the risk increasing with age.

Strengths and weaknesses

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in a LMIC to explore women’s self-assessed health, beginning with pregnancy and continuing up to 22 months after childbirth, and explore associated factors such as hospital admission and presence of chronic illness. Women included in this study were compared with women in the larger JA KIDS study and there were little differences in the study populations, suggesting the findings are generalizable to the Jamaican population. This paper only included women with a live singleton birth and may underestimate ill-health associated with stillbirth or multiple pregnancies. This study focussed on women who were assessed at all four assessment contacts and may underestimate in maternal morbidity as ill-health at the time of delivery could reduce the likelihood of a woman participating in both follow-up visits. Furthermore, as JA KIDS excluded women with severe or life-threatening complications around birth, we report only on ill-health or non-severe maternal morbidity.

Another key strength is the long follow-up period, continuing to 18–22 months after childbirth. While not every woman recruited at each assessment answered every question and around 20% were not assessed at 9–12 months after childbirth, we report on a core group of 1,311 women evaluated at all stages. This ensures we are observing the health status of the same population of women over time.

While the assessment of ill-health reported by women themselves was not ‘verified’ by medical examination, investigations and/or analyses of medical records, our prevalence rate of 10-11% is like findings from other developed and LMIC settings which range from 4% to 15% (Morgan & Eastwood, Citation2014; Zafar et al., Citation2015). Self-reported perception or experience of health has been associated with objective clinical measures of morbidity, after controlling for a variety of physical, socio-demographic and psycho-social health indices (Eriksson, Undén, & Elofsson, Citation2001). Furthermore, women’s own experience and reporting of ill-health or non-wellbeing is increasingly being accepted as a valid outcome measure (Barreix et al., Citation2018; McCauley et al., Citation2018; Zafar et al., Citation2015).

A critical limitation of the lack of clinical examination (e.g. height, weight) resulted in the inability to measure the contribution of obesity or possible malnutrition to maternal morbidity. A 2008 national survey found that 16.5%, 37.7% and 50.5% of non-pregnant Jamaican women 15–24, 25–34 and 35–44 years of age were obese. Underweight was found in 12.6% of 15-24-year olds but only 2.4% of older women (Wilks, et. al., Citation2012). Furthermore, as the study was not designed to explore perinatal outcome, women with an adverse infant outcome were excluded, restricting our capacity to evaluate the relationship between maternal ill-health and perinatal loss.

We included women who had given birth within 48 hours. We recognise that data collected at this time regarding complications during pregnancy and self-reporting of health may not be very reliable and biased. For example, women who have just had a straightforward vaginal birth may be very happy and may under-report their other problems; whereas women who just had a difficult complication of labour and delivery (although a small component) may overstate the situation. In future studies, it may be considered sensible not to collect such data at this stage, as maternal morbidity that arises because of the pregnancy and persists as a health problem could be better screened for during and after pregnancy.

In our study, some antenatal conditions may be misclassified; for example, vomiting could be classified as an obstetric complication due to hyperemesis or as vomiting secondary due to gastroenteritis and classified as a non-obstetric complication. Furthermore, the data collection process did not distinguish between conditions diagnosed prior to pregnancy from those only identified during or since the index birth. This distinction may be difficult to make in many LMICs however as pre-existing conditions may only get diagnosed when women who consider themselves healthy interact with the health services for the first time during pregnancy.

At the time of writing, there was no internationally agreed framework to classify and code medical conditions that contribute to non-severe maternal morbidity. While adapting the WHO ICD-MM framework (World Health Organization, Citation2012) to maternal morbidity was appropriate and feasible, we recognize that the prevalence of some conditions (e.g. threatened preterm labour) differs remarkably from the major causes of maternal death, and may require expanding the ‘other obstetric complications’ category further. Use of this adapted version of the WHO ICD-MM framework to maternal morbidities needs to be explored in further studies to enable realistic comparisons to be made.

Meaning of the study

In our study 31.0% of women require hospitalisation at least once during or after pregnancy. Our admission rate during pregnancy (20.9%) is less than that for teenage girls (26.5%) and women aged 20 years or more (31.1%) from a previous study of Jamaican women (Ashley et al., Citation1994). In the USA, the proportion of pregnant women requiring admission was 12.8% in 2000, a decrease from 17.6% in 1991 (Bacak, Callaghan, Dietz, & Crouse, Citation2005). In the UK, the proportion of women requiring antenatal admission ranges from 16.4–22.6% (Lindquist, Kurinczuk, Redshaw, & Knight, Citation2014; Sultan et al., Citation2013). This constitutes a significant burden for the health system and understanding the reasons for ill-health leading to hospital admission may help develop more comprehensive care packages for use during ‘routine’ antenatal and postnatal care visits that can help reduce this burden. In our study, 21.5% of admitted women required two or more hospital admissions during pregnancy. The reasons for recurrent admission require further investigation as this may indicate recurrent morbidity or inability to manage the first episode of ill-health effectively.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to describe the occurrence of any hospital admission in the first year (6.1%) and up to 22 months childbirth (0.5%), with 10.0% (8/80) and 46.1% (66/13) of women admitted two or more times by 12 months and 22 months respectively. Several studies describe the need and reason for admission in the early postnatal period and up to six weeks after childbirth; with 0.9% of women in the UK readmitted as an emergency within 30 days of childbirth (Lindquist et al., Citation2014; Sultan et al., Citation2013) and 1.3% of women readmitted within 6 weeks of childbirth in the Canada (Liu et al., Citation2002). A randomised controlled trial in Switzerland reported a higher rate of readmission (3.5%) in the first six months after home-based care versus 2.2% after hospital-based care (Boulvain et al., Citation2004). However, data on admission up to and after one-year childbirth is limited and primarily addresses mental health. In Australia 1.7% of new mothers were admitted with a mental health diagnosis in the first year after childbirth (Xu et al., Citation2014).

The most common reason for admission in the first year was due to sequelae of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and this was also the most common self-reported ongoing chronic illness after childbirth. It is unclear whether some are misclassified cases of essential hypertension first diagnosed during pregnancy. Women reporting chronic illness tend to be older, higher parity, more likely delivered by elective CS and/or report ill-health. However, neither hospital admission nor reporting of ill-health are particularly good indicators or proxy markers of perceived maternal morbidity with a likelihood ratio of between 1.4 and 1.8 only.

The documented CS rate (19.4%) for Jamaica exceeds the 15% upper limit recommended by the WHO after which the benefit to mother or neonate cease to exceed the risk (Belfort et al., Citation2010; World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Citation2015). US and Canadian women who had a CS were more likely to be readmitted than after a vaginal birth, with pregnancy-related infections common reasons for readmission within six weeks of birth in women with CS compared to vaginal birth (Bacak et al., Citation2005; Liu et al., Citation2002).

Unanswered questions

The current challenge is that estimates of non-severe maternal morbidity are not based on standardised, clear and concise definitions and methodology, and thus have limited utility and validity to inform efforts to measure and address the burden of ill-health during and after pregnancy and do not allow comparability across settings. Recent studies demonstrating the need to develop and test a standardized tool holds some promise for the future (Barreix et al., Citation2018; McCauley et al., Citation2018; Ye et al., Citation2016). This will complement existing guidelines for severe acute maternal morbidity or ‘near misses’ (Chou et al., Citation2016; Say, Souza, & Pattinson, Citation2009).

Conclusions

This longitudinal assessment of maternal health during pregnancy and up to 22 months after childbirth among women delivering singleton livebirths in Jamaica indicates that one in 10 women did not assess their health status favourably during this period; and these women were more likely to be older, socially vulnerable and with a pre-existing chronic health condition. Efforts are needed to promote global use of a standardized tool to measure and understand non-life threatening maternal ill-health co-existing with childbearing. Effective methodologies will benefit the family and the community by safeguarding the chances for both mother and baby to survive and thrive.

Author’s contributions

AMB, MSV and NvdB conceived the study. MM, JAR and NvdB conceived the design of the secondary analysis and inclusion of variables. MM coded variables in the database. JAR cleaned the data and JAR and SW performed data analysis. MM interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. JAR, SW, AMB, NvdB and MSV edited the manuscript and have approved it for submission.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the University of the West Indies Ethics Committee (Mona) and the Ministry of Health’s Advisory Panel on Medico - Legal Affairs, Kingston, Jamaica.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the staff in health centres and hospitals throughout Jamaica for their help during recruitment, and the JA KIDS team, of interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical and administrative workers, research scientists, volunteers and managers at the University of the West Indies (Mona). The Inter-American Development Bank (Grant ref: ATN/JF-12312-JA; ATN/OC-14535-JA) and the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus provided core support for JA KIDS. Secondary data analysis at the Centre for Maternal and Newborn Health in the UK was funded through a Global Health Grant (Project number OPP1033805) from Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and World Health Organization (WHO). Additional support was provided by the World Bank, UNICEF, the CHASE Fund, the National Health Fund, Parenting Partners Caribbean, the University of Nevada - Las Vegas, the University of Texas Health Science Centre at Houston and Michigan State University and its Partners. This publication is the work of the authors listed who will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdulrahim, S., & El Asmar, K. (2012, Sep 17). Is self-rated health a valid measure to use in social inequities and health research? Evidence from the PAPFAM women’s data in six Arab countries. International Journal for Equity in Health, 11, 53.

- Ashley, D., McCaw-Binns, A., Golding, J., Keeling, J., Escoffery, C., Coard, K., & Foster-Williams, K. (1994). Perinatal mortality survey in Jamaica: Aims and methodology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 8, S6–S16.

- Bacak, S. J., Callaghan, W. M., Dietz, P. M., & Crouse, C. (2005). Pregnancy-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1999-2000. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 192, 592–597.

- Barreix, M., Barbour, K., McCaw-Binns, A., Chou, D., Petzold, M., Gichuhi, G. N., & Say, L.; WHO Maternal Morbidity Working Group (MMWG). (2018 May). Standardizing the measurement of maternal morbidity: Pilot study results. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: the Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 141(Suppl 1), 10–19.

- Belfort, M. A., Clark, S. L., Saade, G. R., Kleja, K., Dildy, G. A., 3rd, Van Veen, T. R., … Kofford, S. (2010). Hospital readmission after delivery: Evidence for an increased incidence of non-urogenital infection in the immediate postpartum period. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202, 35e1–e7.

- Boulvain, M., Perneger, T. V., Othenin-Girard, V., Petrou, S., Berner, M., & Irion, O. (2004). Home-based versus hospital-based postnatal care: A randomised trial. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 111, 807–813.

- Chou, D., Tunçalp, Ö., Firoz, T., Barreix, M., Filippi, V., von Dadelszen, P., & Say, L.; Maternal Morbidity Working Group. (2016 Mar 2). Constructing maternal morbidity - towards a standard tool to measure and monitor maternal health beyond mortality. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16, 45.

- Eriksson, I., Undén, A.-L., & Elofsson, S. (2001). Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30, 326–333.

- Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data - or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography, 38, 115–132.

- Firoz, T., Chou, D., von Dadelszen, P., Agrawal, P., Vanderkruik, R., Ö, T., & Say, L.; Maternal Morbidity Working Group. (2013, Oct 1). Measuring maternal health: Focus on maternal morbidity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 91(10), 794–796.

- Lindquist, A., Kurinczuk, J. J., Redshaw, M., & Knight, M. (2014). Experiences, utilisation and outcomes of maternity care in England among women from different socio-economic groups: Findings from the 2010 National Maternity Survey. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 122, 1610–1617.

- Liskin, L. S. (1992). Maternal morbidity in developing countries: A review and comments. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 37, 77–87.

- Liu, S., Heaman, M., Kramer, M. S., Demissie, K., Wen, S. W., & Marcoux, S. (2002, Sep). Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Length of hospital stay, obstetric conditions at childbirth, and maternal readmission: A population-based cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 187(3), 681–687.

- Mantel, G. D., Buchmann, E., Rees, H., & Pattinson, R. C. (1998). Severe acute maternal morbidity: A pilot study of a definition for a near-miss. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 105, 985–990.

- McCauley, M., Madaj, B., White, S. A., Dickinson, F., Bar-Zev, S., Aminu, M., … van den Broek, N. (2018, May 3). Burden of physical, psychological and social ill-health during and after pregnancy among women in India, Pakistan, Kenya and Malawi. BMJ Glob Health, 3(3), e000625.

- McCaw-Binns, A. M., Campbell, L. V., & Spence, S. S. (2018, Feb 8). The evolving contribution of non-communicable diseases to maternal mortality in Jamaica, 1998-2015: A population-based study. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15154

- Morgan, K. J., & Eastwood, J. G. (2014, Jan 21). Social determinants of maternal self-rated health in South Western Sydney, Australia. BMC Research Notes, 7, 51.

- Pattinson, R., Say, L., Souza, J. P., van den Broek, N., & Rooney, C. (2009). WHO maternal death and near-miss classifications. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87, 734–A.

- Say, L., Souza, J. P., & Pattinson, R. C.; WHO working group on Maternal Mortality and Morbidity classifications. (2009 Jun). Maternal near miss–Towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 23(3), 287–296.

- Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Jamaica – Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2011. January 2015. http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2214/study-description

- Sultan, A. A., West, J., Tata, L. J., Fleming, K. M., Nelson-Piercy, C., & Grainge, M. J. (2013). Risk of first venous thromboembolism in pregnant women in hospital: Population based cohort study from England. BMJ, 347, f6099.

- The Jamaican Birth Cohort Study 2011, 2019. January 2019. https://www.mona.uwi.edu/fms/jakids/

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: Author. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/7891Transforming%20Our%20World.pdf

- United Nations, World Health Organization. (2015). The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health 2016-2030. New York: United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/en/

- Wilks, R., Younger, N., Tulloch-Reid, M., Shelly McFarlane, S., & Francis, D. for the Jamaica Health and Lifestyle Survey Research Group 2012. Jamaica Health and Lifestyle Survey 2007-08: Technical Report. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2012/Jamaica-Health-LifeStyle-Report-2007.pdf

- World Health Organization. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June 1946, and entered into force on 7 April 1948.

- World Health Organization. (2012). The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM. Geneva: Author. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241548458/en/

- World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research. (2015). WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. Geneva: Author. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/161442/WHO_RHR_15.02_eng.pdf

- Xu, F., Sullivan, E. A., Li, Z., Burns, L., Austin, M.-P., & Slade, T. (2014). The increased trend in mothers’ hospital admissions for psychiatric disorders in the first year after birth between 2001 and 2010 in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Women’s Health, 14, 119.

- Ye, J., Zhang, J., Mikolajczyk, R., Torloni, M. R., Gülmezoglu, A. M., & Betran, A. P. (2016, Apr). Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century: A worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 123(5), 745–753. Epub 2015 Aug 24

- Zafar, S., Jean-Baptiste, R., Rahman, A., Neilson, J. P., & van den Broek, N. R. (2015, Sep 21). Non-life threatening maternal morbidity: cross sectional surveys from Malawi and Pakistan. PloS One, 10(9), e0138026.