ABSTRACT

This studyinvestigates the need for psycho-oncological care over the course of a breast cancer treatment and possible associated factors to develop such a need. The PIAT-Study was a longitudinal postal survey study conducted in Germany (2013 to 2014) with breast cancer patients (BCPs). Patients received a questionnaire at three-time points (T1: few days after surgery, T2: after 10 weeks; T3: after 40 weeks). This study considers information about patients’ needs for psycho-oncological care, their breast cancer disease, social support, anxiety, health literacy (HL) and sociodemographic information. Data were analysed with descriptive statistics and logistic regression modelling to estimate the association between a need for psycho-oncological treatment and patient characteristics. N = 927 breast cancer patients reported their psycho-oncological need. 35.2% of patients report at least at one measuring point to be in need for psycho-oncological care. In a multiple logistic regression, noticeable determinants for developing such a need are an inadequateHL(OR = 1.97), fear of progression (FoP) (OR = 2.08) and psychological comorbidities (OR = 8.15) as well as certain age groups. BCPs with a low HL, suffering from a dysfunctional level of FoP or mental disorders are more likely to develop a need for psycho-oncological care.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in Germany (Robert Koch-Institut, Citation2016) and can be seen as a chronical disease (van Muijen et al., Citation2013). Around 69.000 women are newly diagnosed with breast cancer every year, in Germany (Robert Koch-Institut, Citation2016). One-third of breast cancer patients report to suffer from mental illness over the course of their treatment (Maass et al., Citation2015; Mitchell et al., Citation2011; Vehling et al., Citation2012). Patients suffering from breast cancer have a higher prevalence of a mental disorder in comparison to other tumor entities as shown in a large diverse sample of cancer patients (Mehnert et al., Citation2014; Tsaras et al., Citation2018). Up to 50% of breast cancer patients show psychological symptoms like depression in the time after diagnosis and report more depressive symptoms after 5 years compared to the general female population (Maass et al., Citation2015; Pinto & De Azambuja, Citation2011, Citation2011; Schubart et al., Citation2014; Tojal & Costa, Citation2015).

Prevalent comorbidities of a cancer diagnosis are anxiety and adjustment disorders as well as depression (Herschbach et al., Citation2010; Koch et al., Citation2013; Maass et al., Citation2015; Mehnert et al., Citation2006; Walker et al., Citation2013). Besides symptoms like fatigue, feeling of isolation, pain and helplessness, fear of progression (FoP) is a common symptom which is likely to occur with a cancer diagnosis and its treatment (Crist & Grunfeld, Citation2013; Koch et al., Citation2013). FoP is a common fear among cancer patients and patients with chronical diseases (Simard et al., Citation2013). FoP includes fears and worries about the development of the disease and a possible recurrence. If FoP levels arise to a dysfunctional level it may need to be treated (Herschbach et al., Citation2010). Simard et al. stated that 49% of cancer patients develop a moderate to high FoP (Simard et al., Citation2013). While Koch et al. found 6% of long-term survivors to show high levels of FoP (Koch et al., Citation2014). FoP is associated with distress, a depressive coping style as well as lower quality of life (Koch et al., Citation2014; Mehnert et al., Citation2009; Simard et al., Citation2013). Cancer-related anxiety and worries are one of the main motives why patients seek psychological help during their cancer treatment (Salander, Citation2010).

Fiszer et al. stated in a systematic review that 20–70% of breast cancer patients show a need for psycho-oncological support (CitationFiszer et al., 2014). However, the sole occurrence of symptoms of depression or anxiety is not synonymous to being in need for psycho-oncological care (Ernstmann et al., Citation2009). The subjective feeling of distress and suffering or furthermore the subjective feeling of needing support should be considered (Ernst et al., Citation2018). This has already been implicated by the German AWMF Guidelines Program for Psycho-Oncology that next to an indication, also motivation for psycho-oncological care is needed (AWMF, Citation2014). Around one-third of patients wish for psycho-oncological support during their hospital stay (Singer et al., Citation2010).

Developing a need for psycho-oncological care and the use of psycho-oncological care require complex skills in terms of self-perception, active coping strategies, and knowledge about health-care providers and services. A comprehensive construct incorporating these individual skills is health literacy. As a complex construct, health literacy includes features such as finding health information up to applying information about healthy living (Sørensen et al., Citation2012). A limited health literacy has been associated with higher FoP (Halbach, Enders, et al., Citation2016), which influence coping mechanisms and is associated with a reduced self-care behavior (Matsuoka et al., Citation2016; Scarpato et al., Citation2016). Hence, limited health literacy might be a risk factor for the need for psycho-oncological care and a sufficient health literacy might be a barrier for developing a need for psycho-oncological care.

Diverse barriers on individual as well as organizational level to receive and find psycho-oncological care have been described earlier (Singer et al., Citation2017) (Fagerlind et al., Citation2013; Henderson et al., Citation2013; Neumann et al., Citation2010). Individual barriers include stigma of psychotherapy, not realizing to be in need or belief to be unable to find a psychotherapist (Dilworth et al., Citation2014; Pepin et al., Citation2009). Main organizational barriers can be identified in an insufficient and incomprehensible psycho-oncological service situation (Bergelt et al., Citation2016; Wickert et al., Citation2013). There are multiple options for psycho-oncological care, e.g. some hospitals have their own departments for psycho-oncological care or they offer consultation service or there are outpatient psycho-oncologist or therapists as well.

There are studies about psychological comorbidities and FoP within breast cancer patients. Additionally, the individual health literacy of breast cancer patients has been investigated in depth (Altin & Stock, Citation2016; Halbach, Enders et al., Citation2016; Halbach, Ernstmann et al., Citation2016; Schmidt et al., Citation2016). However, there has been limited research which combines these topics in regard of changing needs for psycho-oncological support over a course of a breast cancer treatment as well as in terms of determinants for developing such a need.

Thus the aims of this study are: (1) to investigate distribution and change of need for psycho-oncological care over the course of a breast cancer treatment, (2) to investigate individual determinants for reporting a need for psycho-oncological support with special emphasis on individual health literacy, FoP, and mental disorders. Especially, it is intended to clarify whether there are positive or negative associations between health-literacy levels and the need for psycho-oncological care.

Methods

Study design and participants

In 2013 female breast cancer patients, treated in breast cancer center hospitals, were asked to participate in a prospective, longitudinal and multicenter cohort study (PIAT-Strengthening patient competence: Breast cancer patients’ information and training needs).98 out of 247 German breast cancer centers hospitals (as certified by the German Cancer Society and the German Society for Senology at that time) were randomly approached to take part in the study. In total 56 breast cancer center hospitals participated in the study.

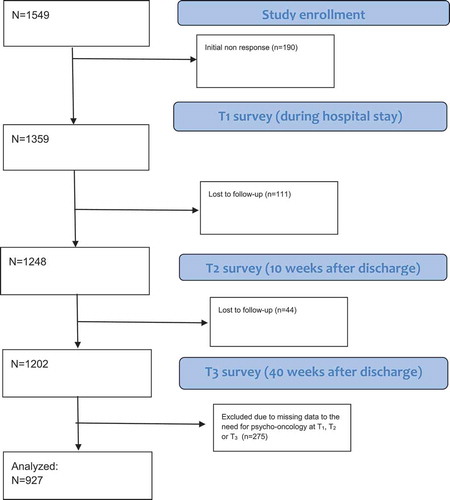

In the participating centers, patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer and receiving an inpatient surgery between 1st of February and 31st of August 2013 were approached by nurses of medical staff to be enrolled in the study. If patients were interested in taking part, they gave written consent and filled out a contact sheet that was sent back to the survey institute. Participating patients received the first questionnaire while being at the hospital (T1 = few days after surgery). After discharge those patients were sent questionnaires at two follow-up time points (T2 = 10 weeks after surgery and T3 = 40 weeks after surgery). Patients received all questionnaires via postal service. Patients who answered the questions about psycho-oncological support at every measuring point were included in the following analysis. The final sample consists of N = 927 patients (see for the flow chart and the final sample).

Variables and measures

At T1 patients’ socio-demographic information (e.g. age, education, mother-tongue, living with a partner) was gathered. Data about need for psycho-oncological support and care as well as health literacy were asked at measuring points T1, T2 and T3. FoP was assessed at measuring points T1 and T3. Information about comorbidity was asked at T1. Pre-tests were conducted beforehand for all measures and used instruments as described elsewhere (Halbach, Enders et al., Citation2016; Schmidt et al., Citation2016). Information about clinical characteristics (e.g. staging of tumor) were given by clinical personnel.

Fear of Progression (FoP)

For measuring FoP, the short-version of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF) was used (Mehnert et al., Citation2006). The questionnaire includes 12 items which can be answered on a 5-point-Likert-Scale (1 = never to 5 = very often), thus scores are possible to range between 12 and 60 points. Higher scores implicate higher fear of progression. Herschbach et al. stipulate a cut-off value for dysfunctional FoP, which is based on the total sum score (Herschbach et al., Citation2010). If a patient scores higher than 33 points (34–60 points), the score indicates a dysfunctional level of FoP. Four dimensions of FoP (‘affective reactions’, ‘partnership/family’, ‘occupation’ and ‘loss of autonomy’) are assessed by FoP-Q-SF.

Comorbidity

Information about comorbidity was asked at measuring point T1, this scale has been already used prior to this study (Pfaff et al., Citation2009). Ten options were given to choose one or more from. For this analysis the presence of mental illness was taken in account (‘Do you suffer from one or more of the following diseases?’ ‘1 = Diabetes 2 = Stroke 3 = Chronic Bronchitis, 4 = Kidney Disease, 5 = Cardiovascular Disease, 6 = Mental Illnesses, 7 = High Blood Pressure, 8 = Arthritis or Rheumatism, 9 = none, 10 = other diseases’).

Health literacy

The German version of the HLS-EU-Q16 (Sørensen et al., Citation2012), which is a short version of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire, was used to assess health literacy. The HLS-EU-Q16 covers with 16 items four dimensions of health literacy. Every item could be answered on a 4 point Likert Scale (‘1 = very difficult’ to ‘4 = very easy’) with an additional option (‘don’t know’). Patients were classified into following categories depending on their scores: sufficient (>12–16 points), problematic (>8–12 points) and inadequate (0–8 points).

Further information about the used questionnaires of FoP and health literacy can be found elsewhere (Halbach, Enders et al., Citation2016; Schmidt et al., Citation2016).

Information about psycho-oncological need and treatment

Information about needing psycho-oncological care or receiving support was measured with a scale differentiating three options at T1 and four options at T2 and T3. The scale is an adapted subscale of the WIN-ON-Questionnaire (Pfaff et al., Citation2014). At T1 patients could either choose ‘Yes I’m in need for psychological support and I’m already receiving treatment’, ‘Yes, I’m in need for psychological care and I’m waiting for treatment’ and ‘No, I’m not in need for psychological care’. At T2 and T3 patients had the following options: ‘I’m in treatment which started beforehand of the diagnosis’, ‘Yes, I’m in need for psychological support and receiving care’, ‘Yes I’m in need for psychological support and still waiting for treatment’ and ‘No, I’m not in need for psychological support’.

Data analysis

Data analyses were carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. If cases were missing more than 30% of their answers, they were deleted, leaving a sample of 1060 patients in a first step. Further patients were deleted, if they did not answer the psycho-oncological support question at every measuring point, leaving a final sample of 927 patients. Descriptive statistics were used for all variables. A stepwise logistic regression model was estimated. The dependent variable `need for psycho-oncological support’ was defined into two groups, those who answered at least once over all measuring times that they needed support and may even receive treatment and those who did not feel a need for psycho-oncological support at any measuring point.

Results

Descriptive results

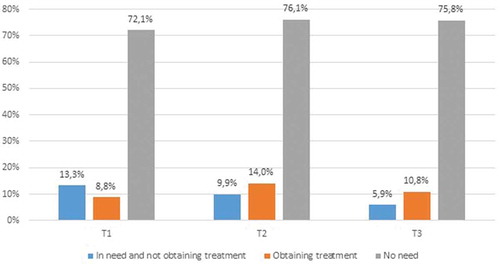

927 patients answered the questions about psycho-oncological support at every measuring point. shows the sample characteristics as well as the need for psycho-oncological care over the course of cancer treatment. shows the need for care as well as receiving psycho-oncological care at every measuring point. At each time point around 20% of patients show a need for psycho-oncological care regardless if they obtain care. 10% of patients obtain care at every measuring point. 1.3% of patients show a need for psycho-oncological care from T1 to T3 but are still waiting for care at T3. 1.6% develop a need at T3 and are not receiving care. In contrast 58.4% do not report a need for a psycho-oncological care at all.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Results of logistic regression analysis and multilevel modelling

presents the findings of the stepwise logistic regression analysis regarding the association of different determinants (e.g. FoP, health literacy) with need for psycho-oncological treatment. In a first step socio-demographical information was considered, in a second step comorbidity and UICC stages, in a third step health-literacy and in a final step FoP. The regression model shows significant effects for breast cancer patients in an age-group of 50–54 (OR = 0.43; 95%Cl = 0.24–0.77) and 60–99 years (OR = 0.27; 95%-Cl = 0.16–0.47) as well as for patients with a lower school certificate (OR = 0.53; 95%-Cl = 0.33–0.83).

Table 2. Logistic regression with need for psycho-oncological care at any point in time (T1–T3) as dependent variable

Suffering from a mental disorder is significantly associated with showing a need for psycho-oncological care (OR = 8.15; 95%-Cl = 3.72–17.86). Furthermore, patients with an inadequate health literacy are significantly more likely to develop a need than patients with a sufficient health literacy (OR = 1.97; 95%-Cl = 1.26–3.08). Patients suffering from dysfunctional FoP are significantly more likely (OR = 2.08; 95%-Cl = 1.38–3.15) to develop a need for psycho-oncological care than those with a functional FoP. Pseudo-R2 of Nagelkerke assumes a value of .210.

Discussion

Aim of our study was to identify possible changes of psycho-oncological need over time as well as looking for determinants for developing a need for psycho-oncological care over the course of a breast cancer treatment. No studies to our knowledge were found about longitudinal studies, which focuses on our combination of determinants of developing a need for psycho-oncological care.

Our results show that around one-fourth of patients are in a need for psycho-oncological care at every measuring point over the course of their treatment and one-third of all patients report to be in need at least at one measuring point, which is in line with other studies (Mitchell et al., Citation2011; Singer et al., Citation2007; Vehling et al., Citation2012). Our study focused on reporting needs rather than only on the appearance of symptoms of mental disorders. Because the subjective feeling of distress and having an urge for treatment should always be considered (AWMF, Citation2014) as an indication for treatment. Moreover, there is recognizable decrease of being in need for psycho-oncological care over the course of a breast cancer treatment, which might be caused by adaptation processes and gained information that could lead to less distress.

Our second aim was to identify determinants for developing a need for psycho-oncological care. Patients aged 50–54 years and especially those over 60 years are significantly less likely to develop a need for psycho-oncological treatment. Elderly cancer patients tend to have a higher Quality of Life (Adam et al., Citation2018; Parker et al., Citation2003), experience less FoP (Mehnert et al., Citation2013), also they tend to suffer from less aggressive forms of breast cancer and might not have to take care of children or need less support in their everyday lives (Mor et al., Citation1994).

Patients with an inadequate health literacy are almost twice more likely to develop a need for psycho-oncological care. Halbach, Enders et al. (Citation2016) showed that elderly patients with an inadequate health literacy are more likely to develop high FoP-Levels and in combination with Salanders (Salander, Citation2010) results, that anxiety and worries are the most common reasons to seek help, these findings support our results that health literacy as well as FoP are determinants for developing a need for psycho-oncological care.

18.9% of patients showed a dysfunctional level of FoP, which is less than Simard et al. reported but in contrast twice as much as Mehnert et al. found for long-term survivors (Mehnert & Koch, Citation2008; Simard et al., Citation2013). Fear can lead to a feeling of helplessness which increases the likelihood to develop depressive symptoms (Miller & Seligman, Citation1975). A low health literacy can lead to extreme views on cancer (Morris et al., Citation2013) which could increase a feeling of fear and helplessness, since an understanding of the disease and possibilities of treatment and coping are not accessible for those patients. Hence these patients are more likely to develop depressive and anxiety symptoms which can influence their quality of life.

Patients who already suffer from a mental disorder are eight times more likely to be in need for psycho-oncological care. Symptoms of mental disorders can lead to increased suffering and may influence coping strategies and thus promote a subjective desire for psycho-oncological care. Since a cancer diagnosis is usually overwhelming and leads to a feeling of further distress, patients who are already suffering from a mental disorder might have less resources and resilience to deal with this new burden in their life.

Furthermore, a dysfunctional level of anxiety and mental disorders shape coping styles and information processing (Amaral, Citation2002; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Steimer, Citation2002). A high arousal might hinder a successful coping, which supports our findings that those are significantly more vulnerable who have dysfunctional levels of FoP and suffer from a mental disorder.

Breast cancer patients with a lower educational status are significantly less likely to develop a need for psycho-oncological care. This might be because of a lack of knowledge about this type of intervention and stigma of psychotherapy (Andritsch, Citation2001).

The independent variables explain a certain amount of variance in the need for psycho-oncological care. However, a large amount of variance remains unexplained. Other factors influencing the need for psycho-oncological care might be associated with individual coping strategies, sense of coherence or resilience. Beside those individual factors also supporting relationship to health-care professionals (others than psycho-oncologists) might be helpful for patients and fulfil their psychosocial needs.

Limitations and strengths

There are some limitations to our study which should be considered. The observational study design included mostly self-reported items, a common method bias might lead to an overestimation of the associations found. No causal interferences can be drawn from this sample due to the observational design. There might be a selection bias in terms of higher education and an underestimation of immigrants since the questionnaires were not translated into foreign languages. The question about psycho-oncological care needs differed from T1 to T2 and T3, a fact which might have biased the answers, since patients had more options at T2 and T3. Although the items were pretested by cognitive think-aloud interviews, it cannot be excluded that respondents might have different understandings of the concept ‘psychological support’. Furthermore, there is no knowledge if patients are actively seeking help and are enrolled on waiting lists or whether they are in need for psycho-oncological care but have not initiated to search for help yet. Strengths of this study are the longitudinal design, a high response rate, the multi-centered design with a random sample and the use of validated instruments. Since the data was hierarchically structured and patient data was embedded in breast cancer centers, multilevel modeling was used to consider clustering. Multilevel modeling was carried out with STATA version 15 and showed no significant associations for breast cancer centers and psycho-oncological need.

Conclusion and implications

In conclusion, insufficient health literacy, mental disorders, dysfunctional levels of FoP, higher education and younger age are significantly associated with a need for psycho-oncological care. Our findings give new insights in the development of a need for psycho-oncological care in breast cancer.

Practical implications can be seen on different levels. First health-care systems and health insurances should provide a realistic supply on psycho-oncological care as well as structures and to ensure that health-care providers are able to take part in further education programs without much effort or loss of money or their leisure time. Further education should ensure that oncologists and doctors should be able to identify and address emotional distress and foster their knowledge about treatment options to enable their patients. Health-care providers should pay attention to indicators of health literacy levels and may screen their patients for mental comorbidities. Further research should investigate determinants for other tumor entities and also focus on partners of oncological patients and their determinants for a need for psychotherapy (Ketcher & Reblin, Citation2019; Zimmermann, Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

Dr. Kowalski reports grants from the German Ministry of Health to the University of Cologne, during the conduct of the study, and is an employee of the German Cancer Society (Krebsgesellschaft), the non-profit scientific association that develops clinical guidelines and criteria for the certification of cancer centers.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam, S., Feller, A., Rohrmann, S., & Arndt, V. (2018). Health-related quality of life among long-term (≥5 years) prostate cancer survivors by primary intervention: A systematic review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0836-0

- Altin, S. V., & Stock, S. (2016). The impact of health literacy, patient-centered communication and shared decision-making on patients’ satisfaction with care received in German primary care practices. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 450. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1693-y

- Amaral, D. G. (2002). The primate amygdala and the neurobiology of social behavior: Implications for understanding social anxiety. Biological Psychiatry, 51(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01307-5

- Andritsch, E. (2001). Psychoonkologie aus der Sicht des am Krankenbett arbeitenden Psychologen/Psychotherapeuten. Der Onkologe, 7(2), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007610170150

- AWMF. (2014). Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Psychoonkologische Diagnostik, Beratung und Behandlung von erwachsenen Krebspatienten, Kurz version 1.1 2014 AWMF -Registernummer: 032/051OL.

- Bergelt, C., Reese, C., & Koch, U. (2016). Psychoonkologische Versorgung in Deutschland. In A. Mehnert & U. Koch (Eds.), Handbuch Psychoonkologie (1st ed., pp. 454–463). Hogrefe.

- Crist, J. V., & Grunfeld, E. A. (2013). Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 22(5), 978–986. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3114

- Dilworth, S., Higgins, I., Parker, V., Kelly, B., & Turner, J. (2014). Patient and health professional’s perceived barriers to the delivery of psychosocial care to adults with cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 23(6), 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3474

- Ernst, J., Faller, H., Koch, U., Brähler, E., Härter, M., Schulz, H., Köhler, N., Hinz, A., Mehnert, A., & Weis, J. (2018). Doctor’s recommendations for psychosocial care: Frequency and predictors of recommendations and referrals. PloS One, 13(10), e0205160. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205160

- Ernstmann, N., Neumann, M., Ommen, O., Galushko, M., Wirtz, M., Voltz, R., Hallek, M., & Pfaff, H. (2009). Determinants and implications of cancer patients’ psychosocial needs. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 17(11), 1417–1423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0605-7

- Fagerlind, H., Kettis, Å., Glimelius, B., & Ring, L. (2013). Barriers against psychosocial communication: Oncologists’ perceptions. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 31(30), 3815–3822. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.1609

- Fiszer, C., Dolbeault, S., Sultan, S., & Bredart, A. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 23(4):361–74. doi: 10.1002/pon.3432

- Halbach, S. M., Enders, A., Kowalski, C., Pförtner, T.-K., Pfaff, H., Wesselmann, S., & Ernstmann, N. (2016). Health literacy and fear of cancer progression in elderly women newly diagnosed with breast cancer–A longitudinal analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(5), 855–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.12.012

- Halbach, S. M., Ernstmann, N., Kowalski, C., Pfaff, H., Pförtner, T.-K., Wesselmann, S., & Enders, A. (2016). Unmet information needs and limited health literacy in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients over the course of cancer treatment. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(9), 1511–1518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.028

- Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 777–780. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056

- Herschbach, P., Book, K., Dinkel, A., Berg, P., Waadt, S., Duran, G., Engst-Hastreiter, U., & Henrich, G. (2010). Evaluation of two group therapies to reduce fear of progression in cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 18(4), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0696-1

- Ketcher, D., & Reblin, M. (2019). Social networks of caregivers of patients with primary malignant brain tumor. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 24(10):1235–1242. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1619787

- Koch, L., Bertram, H., Eberle, A., Holleczek, B., Schmid-Höpfner, S., Waldmann, A., Zeissig, S. R., Brenner, H., & Arndt, V. (2014). Fear of recurrence in long-term breast cancer survivors-still an issue. Results on prevalence, determinants, and the association with quality of life and depression from the cancer survivorship–a multi-regional population-based study. Psycho-Oncology, 23(5), 547–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3452

- Koch, L., Jansen, L., Brenner, H., & Arndt, V. (2013). Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors–A systematic review of quantitative studies. Psycho-Oncology, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3022

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Maass, S. W. M. C., Roorda, C., Berendsen, A. J., Verhaak, P. F. M., & De Bock, G. H. (2015). The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Maturitas, 82(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.010

- Matsuoka, S., Tsuchihashi-Makaya, M., Kayane, T., Yamada, M., Wakabayashi, R., Kato, N. P., & Yazawa, M. (2016). Health literacy is independently associated with self-care behavior in patients with heart failure. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(6), 1026–1032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.003

- Mehnert, A., Berg, P., Henrich, G., & Herschbach, P. (2009). Fear of cancer progression and cancer-related intrusive cognitions in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 18(12), 1273–1280. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1481

- Mehnert, A., Brähler, E., Faller, H., Härter, M., Keller, M., Schulz, H., Wegscheider, K., Weis, J., Boehncke, A., Hund, B., Reuter, K., Richard, M., Sehner, S., Sommerfeldt, S., Szalai, C., Wittchen, H.-U., & Koch, U. (2014). Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 32(31), 3540–3546. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0086

- Mehnert, A., Herschbach, P., Berg, P., Henrich, G., & Koch, U. (2006). Progredienzangst bei Brustkrebspatientinnen - Validierung der Kurzform des Progredienzangstfragebogens PA-F-KF/Fear of progression in breast cancer patients – Validation of the short form of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF). Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, 52(3), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2006.52.3.274

- Mehnert, A., & Koch, U. (2008). Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64(4), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.12.005

- Mehnert, A., Koch, U., Sundermann, C., & Dinkel, A. (2013). Predictors of fear of recurrence in patients one year after cancer rehabilitation: A prospective study. Acta Oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden), 52(6), 1102–1109. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2013.765063

- Miller, W. R., & Seligman, M. E. (1975). Depression and learned helplessness in man. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 84(3), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076720

- Mitchell, A. J., Chan, M., Bhatti, H., Halton, M., Grassi, L., Johansen, C., & Meader, N. (2011). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. The Lancet Oncology, 12(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X

- Mor, V., Allen, S., & Malin, M. (1994). The psychosocial impact of cancer on older versus younger patients and their families. Cancer, 74(7 Suppl), 2118–2127. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2118::aid-cncr2820741720>3.0.co;2-n

- Morris, N. S., Field, T. S., Wagner, J. L., Cutrona, S. L., Roblin, D. W., Gaglio, B., Williams, A. E., Han, P. J. K., Costanza, M. E., & Mazor, K. M. (2013). The association between health literacy and cancer-related attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge. Journal of Health Communication, 18(Suppl 1), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.825667

- Neumann, M., Galushko, M., Karbach, U., Goldblatt, H., Visser, A., Wirtz, M., Ernstmann, N., Ommen, O., & Pfaff, H. (2010). Barriers to using psycho-oncology services: A qualitative research into the perspectives of users, their relatives, non-users, physicians, and nurses. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 18(9), 1147–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0731-2

- Parker, P. A., Baile, W. F., De Moor, C., & Cohen, L. (2003). Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 12(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.635

- Pepin, R., Segal, D. L., & Coolidge, F. L. (2009). Intrinsic and extrinsic barriers to mental health care among community-dwelling younger and older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 13(5), 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860902918231

- Pfaff, H., Ernstmann, N., Groß, S. E., Ansmann, L., Gloede, T. D., Nitzsche, A., Baumann, W., Wirtz, M., & Neumann, M. (2014). Fragebogen für Patienten mit Kolorektalkarzinom in ambulanter onkologischer Versorgung (WIN ON Pat) Kennzahlenhandbuch - PDF Kostenfreier download. Institute for Medical Sociology, Health Services Research, and Rehabilitation Science (IMVR), Faculty of Human Sciences and Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne. https://docplayer.org/11371759-Fragebogen-fuer-patienten-mit-kolorektalkarzinom-in-ambulanter-onkologischer-versorgung-win-on-pat-kennzahlenhandbuch.html

- Pfaff, H., Nitzsche, A., Scheibler, F., & Steffen, P. (2009). Der Kölner Patientenfragebogen (KPF) Kennzahlenhandbuch - PDF. Institute for Medical Sociology, Health Services Research, and Rehabilitation Science (IMVR), Faculty of Human Sciences and Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne. https://docplayer.org/16443871-Der-koelner-patientenfragebogen-kpf-kennzahlenhandbuch.html

- Pinto, A. C., & De Azambuja, E. (2011). Improving quality of life after breast cancer: Dealing with symptoms. Maturitas, 70(4), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.09.008

- Robert Koch-Institut. (2016). Berichts zum Krebsgeschehen in Deutschland 2016.

- Salander, P. (2010). Motives that cancer patients in oncological care have for consulting a psychologist–an empirical study. Psycho-Oncology, 19(3), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1569

- Scarpato, K. R., Kappa, S. F., Goggins, K. M., Chang, S. S., Smith, J. A., Clark, P. E., Penson, D. F., Resnick, M. J., Barocas, D. A., Idrees, K., Kripalani, S., & Moses, K. A. (2016). The impact of health literacy on surgical outcomes following radical cystectomy. Journal of Health Communication, 21(sup2), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1193916

- Schmidt, A., Ernstmann, N., Wesselmann, S., Pfaff, H., Wirtz, M., & Kowalski, C. (2016). After initial treatment for primary breast cancer: Information needs, health literacy, and the role of health care workers. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(2), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2814-6

- Schubart, J. R., Emerich, M., Farnan, M., Stanley Smith, J., Kauffman, G. L., & Kass, R. B. (2014). Screening for psychological distress in surgical breast cancer patients. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 21(10), 3348–3353. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3919-8

- Simard, S., Thewes, B., Humphris, G., Dixon, M., Hayden, C., Mireskandari, S., & Ozakinci, G. (2013). Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: Research and Practice, 7(3), 300–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z

- Singer, S., Bringmann, H., Hauss, J., Kortmann, R.-D., Köhler, U., Krauss, O., & Schwarz, R. (2007). Häufigkeit psychischer Begleiterkrankungen und der Wunsch nach psychosozialer Unterstützung bei Tumorpatienten im Akutkrankenhaus [Prevalence of concomitant psychiatric disorders and the desire for psychosocial help in patients with malignant tumors in an acute hospital]. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (1946), 132(40), 2071–2076. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-985643

- Singer, S., Das-Munshi, J., & Brähler, E. (2010). Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care–a meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 21(5), 925–930. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp515

- Singer, S., Kojima, E., Beckerle, J., Kleining, B., Schneider, E., & Reuter, K. (2017). Practice requirements for psychotherapeutic treatment of cancer patients in the outpatient setting-A survey among certified psychotherapists in Germany. Psycho-Oncology, 26(8), 1093–1098. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4427

- Sørensen, K., Van den Broucke, S., Fullam, J., Doyle, G., Pelikan, J., Slonska, Z., & Brand, H. (2012). Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

- Steimer, T. (2002). The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 4(3), 231–249. PMID: 22033741. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181681/#__ffn_sectitle

- Tojal, C., & Costa, R. (2015). Depressive symptoms and mental adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 24(9), 1060–1065. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3765

- Tsaras, K., Papathanasiou, I. V., Mitsi, D., Veneti, A., Kelesi, M., Zyga, S., & Fradelos, E. C. (2018). Assessment of depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP, 19(6), 1661–1669. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.6.1661

- Van Muijen, P., Weevers, N. L. E. C., Snels, I. A. K., Duijts, S. F. A., Bruinvels, D. J., Schellart, A. J. M., & Van der Beek, A. J. (2013). Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care, 22(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12033

- Vehling, S., Koch, U., Ladehoff, N., Schön, G., Wegscheider, K., Heckl, U., Weis, J., & Mehnert, A. (2012). Prävalenz affektiver und Angststörungen bei Krebs: Systematischer Literaturreview und Metaanalyse [Prevalence of affective and anxiety disorders in cancer: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis]. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, medizinische Psychologie, 62(7), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1309032

- Walker, J., Holm Hansen, C., Martin, P., Sawhney, A., Thekkumpurath, P., Beale, C., Symeonides, S., Wall, L., Murray, G., & Sharpe, M. (2013). Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: A systematic review. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 24(4), 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds575

- Wickert, M., Lehmann-Laue, A., & Blettner, G. (2013). Ambulante psychosoziale Krebsberatung in Deutschland-Geschichte und Versorgungssituation. In J. Weis & H. Alexander (Eds.), Psychoonkologie in Forschung und Praxis: Mit 22 Tabellen (pp. 67–78). Schattauer.

- Zimmermann, T. (2015). Intimate relationships affected by breast cancer: Interventions for couples. Breast Care (Basel, Switzerland), 10(2), 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381966