ABSTRACT

This study aimed to determine the mortality in a Jamaican birth cohort over a 3-month period. Data on the outcome of 87.5% of all births in Jamaica between July and September 2011 were used to determine trends in and determinants of neonatal mortality. There were 9650 live births and 144 neonatal deaths yielding a Neonatal Mortality Rate of 14.9/1000 (95% CI: 12.6–17.52/1000) livebirths. One hundred and twenty-one (84%) deaths occurred within the first seven days of life giving an Early Neonatal Mortality Rate of 12.5/1000 (95%CI: 10.4–15.0/1000) livebirths and a Late Neonatal Mortality Rate of 2.38/1000 (95%CI: 1.51–3.57/1000) live births. Sixty-nine (48%) deaths occurred within the first 24 hours. Thirty-eight neonates (26%) died prior to being admitted to a neonatal unit, approximately within 2 hours of life.

Maternal age <15 years, decreasing birthweight, prematurity, male gender, multiple gestation and birth by caesarean section were associated with an increased risk of mortality p < 0.05. In order for Jamaica to experience further decline in its Neonatal Mortality Rate to meet the Sustainable Developmental Goal of at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030 the focus must be on decreasing mortality in the very low birth weight infants who disproportionally contribute to mortality as well as continuing to implement measures to further decrease mortality in the larger infants.

Introduction

The neonatal period, the first 28 days of life, remains a perilous period in a child’s life as it is the time where there is the highest risk of death. Fifty percent of the 2.9 million babies who die worldwide in the neonatal period each year die within the first 24 hours of life and 75% die within the first week of life (Basha et al., Citation2020; Lawn et al., Citation2005; United Nations Development Programme, Citation2015). Four out of every five babies who die do so from three main preventable or treatable causes, complications of prematurity, intrapartum-related events including birth asphyxia, and neonatal infections (World Health Organization, United Nations International Children Emergency Fund 2014). One of the unmet Millennium Developmental Goals was that of decreasing under five mortality by two-thirds by the year 2015. Half of the 6 million children who die under the age of five each year will die in the neonatal period, thus, decreasing neonatal mortality remains a priority as enunciated in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Every New-born Action plan (Lawn et al., Citation2014). The goal of this plan is to end preventable new-born deaths and achieve a target of less than 10 neonatal deaths per 1000 births by 2035 (WHO, UNICEF, Citation2014). Meeting this goal dovetails with achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 of aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030 (United Nations, Citation2015)

The 1986–1987 Jamaican Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality Survey showed that 56% of the recorded neonatal deaths occurred in the first day of life, 89% in the first seven days of life and the commonest cause of death was immaturity 39% and asphyxia-related deaths 35%. The neonatal mortality rate (NMR) was 17.9/1000 live births with an early neonatal mortality rate (ENMR) of 16/1000 live births and a late neonatal mortality rate (LNMR) of 1.9/1000 live births (Ashley et al., Citation1988). The major determinants of neonatal mortality were young maternal age, prematurity, intrapartum asphyxia and twin gestation (Samms-Vaughan et al., Citation1990). A subsequent review of perinatal mortality in Jamaican hospitals in 2003 documented an ENMR of 13.7/1000live births (Lindo et al., Citation2006). McCaw-Binns et al. (Citation2015) in reviewing the quality and completeness of 2008 perinatal and under five mortality data from vital registration in Jamaica documented a NMR of 16.1/1000 live births, an ENMR of 14/1000 live births and a LNMR of 2.1/1000 live births. The latter two studies were retrospective and possible incomplete data may account for some of the difference in mortality rate compared to the prospective Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality Survey.

The Programme for the Reduction of Maternal and Child Mortality, PROMAC funded by the EU in partnership with the Government of Jamaica was commenced in 2014 to aid Jamaica in attaining the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) 4, reduction of child mortality and MDG 5, improvement of maternal health now Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG) 3 (Ministry of Health Jamaica Citationn.d.). The programme supports the establishment of maternal and neonatal High Dependency Units in Jamaica as well as the provision of advanced medical and nursing training for personnel to man these units. The effectiveness of the programme will be measured by what reductions in maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity accrue post implementation of the programme. If Jamaica is to achieve the goal of a neonatal mortality rate of <10 per 1000 live births, it is critical to audit neonatal outcome to determine action points for targeted intervention to decrease neonatal mortality. This study therefore aimed to determine the mortality in a Jamaican birth cohort over a 3-month period which could provide baseline data for assessing the attainment of SDG 3.2 post PROMAC.

Methods

Setting

Jamaica is the largest of the English-speaking Caribbean islands with an area of 10,992 km2 and a population (2011) of 2.7 million people (https://statinja.gov.jm). The Public Health Care system consists of a network of 327 primary care health centres and 24 public hospitals distributed throughout 62 health districts. Approximately 99% of births in Jamaica occur in public or private health-care institutions (Registrar General’s Department Jamaica www.rgd.gov.jm/index.php/vital-statistic).

Study population

The Birth phase of the JA KIDS (https://www.mona.uwi.edu/fms/jakids) longitudinal cohort study commenced on 1 July 2011 and ended 30 September 2011, with 26 public and private hospitals participating across all 14 parishes in Jamaica. Trained field research officers were stationed at hospitals every day during the study period and were assigned to review the Hospital Delivery Register and identify all mothers who delivered in the previous 24 hours. The hospital register also provided important information on women whose babies may have died or were unwell. Information on eligible mothers was recorded on the JA KIDS Delivery Register in the sequence in which the births occurred. Field Research Officers then used the JA KIDS Delivery Register to identify the next mother for enrolment. Mothers were then approached, sensitized about the study, consented and then interviewed. Additionally, JA KIDS staff extracted data from the hospital records of cohort children who were admitted (in the first 28 days of life) to Neonatal Intensive Care Units and Special Care Nurseries across the island.

In total, 9,742 mothers (87.5%) of 11,124 mothers who delivered in Jamaica during this period were enrolled in JA KIDS study. Five percentage of mothers refused to participate while 7.5% of mothers were missed because interviewers did not have the opportunity to interview them, primarily as a result of the mothers being discharged soon after delivery (within 12 hours) or being too ill to participate. The JA KIDS Birth Cohort is therefore made up of children born in all fourteen parishes across Jamaica from July 1 to 30 September 2011.

Definitions

Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR) – the number of babies dying within the first 28 days of life per 1000 live births.

Early Neonatal Mortality Rate (ENMR) – the number of babies dying within the first 7 days of life per 1000 live births.

Late Neonatal Mortality Rate (LNMR) – the number of babies dying after day 7 of life up to day 28 of life per 1000 live births.

Very low birth weight infant (VLBW) – an infant weighing less than 1500 g at birth.

Extremely low birth weight infant (ELBW) – an infant weighing less than 1000 g at birth.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed; mortality was expressed as percentages and rates. Difference between survivors and non-survivors were determined using the chi-square test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was taken at the level p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the conduct of this study was granted by the Jamaican Ministry of Health ethics committee (approval #198; 2011) and the University of the West Indies, Mona Research Ethics Committee (approval # ECP 12 210/11).

Results

During the study period there was a total of 9650 live births. There were seven babies <500 g and or less than 24 weeks gestation who were born alive but died shortly after birth, that were excluded from the study as they were considered to be below the age of viability. There were 144 neonatal deaths giving a NMR of 14.9/1000 (95% CI: 12.6–17.52/1000) livebirths, 121(84%) of them died within the first seven days of life giving an ENMR of 12.5/1000 (95%CI: 10.4–15.0/10 000 livebirths and a LNMR of 2.38/1000 (95%CI: 1.51–3.57/1000) live births. Sixty-nine (48%) deaths occurred within the first 24 hours. Thirty-eight neonates (26%) died prior to being admitted to a neonatal unit, approximately within 2 hours of life.

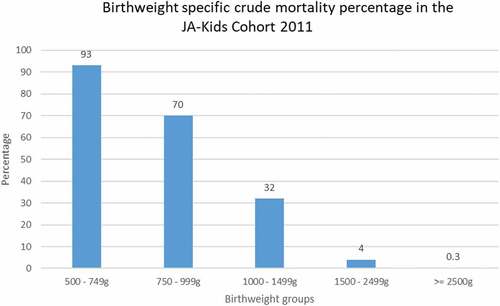

Neonates born to mothers <15 years had an almost eight-fold greater risk of dying than neonates born to mothers 15–19 years and 20–24 years old. Babies born to mothers ≥40 years had a similar risk of dying as those born to younger women 20–29 years (). Mortality decreased with increasing birth weight with neonates <750 g having 93% mortality and those ≥2500 g having 0.3% mortality p < 0.001 (). Very low birth weight infants (VLBW < 1500 g) accounted for 1.6% of the birth cohort but contributed to 54% of overall mortality while extremely low birth weight infants (ELBW <1000 g) accounted for 0.5% of the birth cohort but contributed to 30% of overall mortality.

Table 1. Neonatal mortality rate by maternal age in the JAKIDS cohort 2011.

Premature infants were more likely to die than term infants (OR 20.6; CI 13.1–32.2) and a neonate of a multiple gestation was almost 5 times more likely to die than a neonate from a singleton gestation (OR 4.8; CI 2.3–10.1) . Male infants were more likely to die than their female counterparts (OR 1.5; CI 1.04–2.09). The NMR for males was 17.2/1000 livebirths whereas that for females was 11.7/1000 livebirths. Neonates delivered by caesarean section were more likely to die than neonates delivered vaginally (OR 1.6; CI 1.07–2.35) and of the neonates delivered by caesarean section those delivered on an emergency basis were at higher risk of dying than those delivered electively (OR 3.6; CI 1.8–7.3).

Table 2. Factors associated with mortality in the JAKIDS cohort 2011.

The major clinical causes for mortality were prematurity 67%, sepsis 15% and hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) 15% (). For the neonates who died within 24 hours of birth, prematurity 37/54(68%) and HIE 12/54 (22%) were the most common causes of mortality. Clinical cause of death was recorded for 24 (63%) babies who died within the first 1–2 hours of life, the commonest causes were extreme prematurity 16(67%) and HIE 3(13%).

Table 3. Main clinical causes of mortality in the JAKIDS cohort 2011.

Discussion

There has been a sluggish decline in the neonatal mortality rate for Jamaica over the 25-year period 1986 (17.9/1000) to 2011 (14.9/1000) live births. There has been an 8% and 5% decrease in the number of neonatal deaths occurring in the first 24 hours and the first 7 days of life, respectively, between 1986 and 2011. Approximately half of the deaths that occur in the first 24 hours happen within 1 − 2 hours after birth and the commonest causes (prematurity and asphyxia) for mortality in infants who die in the first 24 hours remains the same as seen in 1986. This finding demands strengthening of obstetric measures for intrapartum monitoring and detection of at risk foetuses and neonatal measures for resuscitation of the newborn and care of very premature infants.

Similar, to that seen in the 1986 Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality Survey (Ashley et al., Citation1988) babies born to mothers <15 years had the highest risk of dying. This increased risk of poor pregnancy outcome in young mothers has been previously documented (Neal et al., Citation2018; UNFPA, Citation2013). However, these extremely young mothers only accounted for 0.4% of the birth cohort in 2011 compared to accounting for 3% of the birth cohort in 1986. This may be a reflection of better public health education about teenage pregnancy, increased exposure of young girls to family life education within schools and increased access to sexual and reproductive health services over time. Fonner et al. (Citation2014) have demonstrated that exposure to family life education increases refusal of sex.

As seen in the 1986–1987 Jamaican Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality Survey (Ashley et al., Citation1988) we demonstrated an excess male mortality, which in our case achieved statistical significance. This increased risk of male mortality has also been previously demonstrated (Lawn et al., Citation2014). An increased risk of mortality for multiple gestation was also seen in the 1986–1987 Survey (Ashley et al., Citation1988), however, in this present study the risk was 5-fold compared to 7-fold for the previous study. This decrease may be due to the fact that all women with multiple gestation are now managed in high-risk clinics, a recommendation coming out of the 1986–1987 Jamaican Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality Survey. This increased mortality for multiple gestation is not unexpected as many of these women deliver prematurely giving rise to VLBW and ELBW infants who have a higher risk of mortality.

It is not unreasonable to expect neonates delivered by emergency caesarean section to be at an increased risk of dying than those delivered vaginally or by elective caesarean section as one of the main causes for operative delivery is foetal distress, indicating that the clinical status of these neonates has been compromised in utero. Additionally, a common reason in our setting for an operative delivery is maternal pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and many of these infants are delivered prematurely with the concomitant risk of increased mortality (McKenzie & Trotman, Citation2018). Lindo et al. (Citation2006) also found that a greater proportion of the neonates who died in their study had an operative delivery.

Decreased mortality with increasing birth weight is not unexpected. The more mature the neonate the less likely the complications of prematurity and its increased risk of mortality. What is extremely problematic for Jamaica is the disproportionate mortality seen in VLBW and ELBW infants whereby although they account for less than 2% of the birth cohort they contribute to up to just over half of neonatal mortality for the island. Lindo et al. (Citation2006) also documented that VLBW infants accounted for 50% of neonatal deaths occurring in the first 7 days in Jamaica. Similarly, Trotman and Olugbuyi (Citation2018) in looking at neonatal mortality over six decades at a tertiary-level institution in Jamaica also noted disproportionate mortality for VLBW infants who although accounting for less than 5% of births accounted for 64% of neonatal mortality. Decreasing mortality in these tiny infants will require human and financial resources and the provision of newer technologies.

The introduction of PROMAC in 2013 is therefore timely as one of the objectives of this programme is to decrease neonatal deaths due to lack of access to high dependency care. To this end six neonatal high dependency units will be built in various parishes across the island to increase access to technologies such as mechanical ventilation, continuous positive pressure ventilation, surfactant replacement therapy, and parenteral nutrition which are all vital for the management of premature VLBW and ELBW infants. The requisite staff are also being trained to man these units. Concomitantly with this initiative, however, in the face of resource constraints there needs to be policy decisions about triage at the limits of viability based on probable futility of care. Data from this study will provide useful baseline data on neonatal mortality against which any gains secondary to the implementation of PROMAC can be measured.

There has been a decrease in the percentage contributed to mortality by asphyxia, however, this is likely to be an underestimate as this was clinically diagnosed in this study as opposed to by autopsy in the 1986–1987 Survey (Ashley et al., Citation1988). Additionally, further studies are needed to see if there is a true decrease in incidence of the condition as opposed to merely a decrease in neonates dying from the condition.

The lack of accurate data on gestational age of the neonates in this study limited the ability to analyze mortality based on maturity, additionally the low autopsy rate limited the ability to accurately document cause of death and to make valid comparisons with the data from the 1986–1987 Survey.

Conclusion

Although, there has been some decrease in the neonatal mortality rate over a 25-year period further significant gains will require decreasing mortality in the very low birth infants who disproportionally contribute to mortality as well as continuing to implement measures to further decrease mortality in the larger infants.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the staff in clinics and hospitals throughout Jamaica for their help in recruiting them, and the whole JA KIDS team from the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical and administrative workers, research scientists, volunteers and managers. The Inter-American Development Bank (Grant ref: ATN/JF-12312-JA; ATN/OC-14535-JA) and the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus provided core support for JA KIDS. Additional support was provided by the World Bank, UNICEF, the CHASE Fund, the National Health Fund, Parenting Partners Caribbean, the University of Nevada – Las Vegas, the University of Texas Health Science Centre at Houston and Michigan State University and its Partners. This publication is the work of the authors Helen Trotman, Maureen Samms Vaughan, Charlene Coore-Desai, Jody Reece and Oluwayomi Olugbuyi who will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ashley, D., McCaw-Binns, A., & Foster-Williams, K. (1988). The perinatal morbidity and mortality survey of Jamaica 1986-1987. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 2(2), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.1988.tb00194.x

- Basha, G. W., Woya, A. A., & Tekile, A. K. (2020). Determinants of neonatal mortality in Ethiopia: An analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. African Health Sciences, 20(2), 715–723. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v20i2.23

- Fonner, V. A., Armstrong, K. S., Kennedy, C. E., O’Reilly, K. R., & Sweat, M. D. (2014). School based sex education and HIV prevention in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 9(3), e89692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089692

- Lawn, J. E., Blencowe, H., Oza, S., You, D., Lee, A. C., Waiswa, P., Lalli, M., Bhutta, Z., Barros, A. J., Christian, P., Mathers, C., & Cousens, S. N., Lancet Every Newborn Study Group. (2014, July 12). Every Newborn: Progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. Lancet, 384(9938): 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60496-7

- Lawn, J. E., Cousens, S., & Zupan, J., & Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. (2005). 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet (London, England), 365(9462), 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5

- Lindo, J. L. M., McCaw Binns, A., Gordon-Strachan, G., Lewis-Bell, K., & Ashley, D. (2006). Perinatal mortality rates of Jamaican health regions. The West Indian Medical Journal, 55(Suppl 2), 50.

- McCaw-Binns, A., Mullings, J., & Holder, Y. (2015). The quality and completeness of 2008 perinatal and under-five mortality data from vital registration, Jamaica. West Indian Medical, J.64(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.7727/wimj.2015.115

- McKenzie, K. A., & Trotman, H. (2018). A retrospective study of neonatal outcome in preeclampsia at the University hospital of the West Indies: A resource-limited setting. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmy014

- Ministry of Health Jamaica. (n.d.). Programme for the reduction of maternal and child mortality. https://www.moh.gov.jm/programmes-policies/promac/.

- Neal, S., Channon, A. A., & Chintsanya, J. (2018). The impact of young maternal age at birth on neonatal mortality: Evidence from 45 low and middle income countries. PloS One, 13(5), e0195731. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195731

- Samms-Vaughan, M. E., McCaw-Binns, A. M., Ashley, D. C., & Foster-Williams, K. (1990). Neonatal mortality determinants in Jamaica. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 36(4), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/36.4.171

- Trotman, H., & Olugbuyi, O. (2018). Neonatal mortality at the university hospital of the West Indies over six decades: trends and causes. The West Indian Medical Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.7727/wimj.2018.173

- UNFPA. (2013). The state of the world population 2013: Motherhood in childhood: Facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy. United Nations Population Fund. http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/swp2013/ENSWOP2013-final.pdf.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- United Nations Development Programme. (2015). The millennium Development goals report 2015. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf

- WHO, UNICEF. (2014). Every Newborn: An action plan to end preventable deaths (2014): Executive summary. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/newborns/every-newborn/en/