ABSTRACT

The psychological impact of COVID-19 on Health Care Workers (HCWs) has been widely reported. Few studies have sought to examine HCWs personal models of COVID-19 utilising an established theoretical framework. We undertook a mixed methods study of beliefs about COVID-19 held by HCWs in the Mid-West and South of Ireland during the first and third waves of COVID-19. Template analysis was undertaken on the free text responses of 408 HCWs about their perceptions of the Cause of COVID-19 as assessed by the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ). Responses were re-examined in the same cohort for stability at 3 months follow-up (n = 100). This analytic template was subsequently examined in a new cohort (n = 253) of HCWs in the third wave. Female HCWs perceived greater emotional impact of COVID-19 than men (t = −4.31, df405, p < 0.01). Differences between occupational groups were evident in relation to Timeline (F4,401 = 3.47, p < 0.01), Treatment Control (F4,401 = 5.64, p < 0.001) and Concerns about COVID-19 (F4,401 = 3.68, p < 0.01). Administration staff believed that treatment would be significantly more helpful and that COVID-19 would last a shorter amount of time than medical/nursing staff and HSCP. However, administration staff were significantly more concerned than HSCP about COVID-19. Template analysis on 1059 responses to the Cause items of the B-IPQ identified ten higher order categories of perceived Cause of COVID-19. The top two Causes identified at both Waves were ‘individual behavioural factors’ and ‘overseas travel’. This study has progressed our understanding of the models HCWs hold about COVID-19 over time, and has highlighted the utility of the template analysis approach in analysing free-text questionnaire data. We suggest that group and individual occupational identities of HCWs may be of importance in shaping HCWs responses to working through COVID-19.

Introduction

Healthcare workers (HCWs) have experienced a range of adverse psychological responses while working during the COVID-19 pandemic (Pappa et al., Citation2020; Spoorthy et al., Citation2020). Significant levels of anxiety (Lai et al., Citation2020), depression (Huang & Zhao, Citation2020), post trauma symptoms (Lai et al., Citation2020), burnout (Serrano-Ripoll et al., Citation2020), moral injury (Serrano-Ripoll et al., Citation2020), stigma (Taylor et al., Citation2020) and sleep disturbance (Zhang et al., Citation2020) have been reported. However, the majority of HCWs continue to report generally good well-being (Greenberg et al., Citation2021). Studies have suggested that a combination of demographic, environmental, occupational and psychosocial factors may be important in explaining individual responses (Alshekaili et al., Citation2020; Sharma et al., Citation2020). However, few studies have set out to elucidate HCWs beliefs about COVID-19, which may be important for understanding HCWs psychological responses while working during the pandemic.

The ‘common sense’ model of illness self-regulation (CSM-SR; Leventhal et al., Citation1992, Citation2016) is one of the most widely used health behaviour models to understand individual’s responses to illness or threat of illness (Hagger & Orbell, Citation2021). The CSM-SR explains how an individual’s beliefs about a condition or illness are developed from a number of factors that may include: information derived from healthcare sources; the persons own experience with health and illness; and lay ideas from friends, family and the media. These beliefs drive an individual’s cognitive, behavioural and emotional attempts to cope with the condition or threat of the condition and consequently will influence important outcomes including psychological distress (Hagger et al., Citation2017). The key beliefs or illness perceptions generally held by individuals have been empirically demonstrated to fall under a number of key areas: Illness Identity (symptoms associated with a condition), Consequences, Coherence (understanding), Control (behavioural and treatment related), Concern, Emotional consequences and Causes associated with the condition. As such this would appear to be a helpful approach for understanding HCWs psychological responses to working in the pandemic. There is to date little data exploring HCWs personal beliefs about COVID-19.

Based on the CSM-SR, one of the most coherent measures developed to understand an individual’s illness beliefs is the Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ; (Weinman et al., Citation1996) and its modified versions, the IPQ-revised (IPQ-R; Moss-Morris et al., Citation2002) and the 9 item Brief-IPQ (B-IPQ; Broadbent et al., Citation2006, Citation2019). In the context of COVID-19 there have been a number of studies which have utilised the IPQ-R and B-IPQ, in the general population (Chong et al., Citation2020; Dias Neto et al., Citation2021; Perez-Fuentes et al., Citation2020; She et al., Citation2021; Skapinakis et al., Citation2020) and HCWs (Man et al., Citation2020; Shahzad et al., Citation2020) in attempts to understand the beliefs held and impact of COVID-19 on individuals. Very few studies have used the measures in the original format; some have used modified versions of the scales (Chong et al., Citation2020; Perez-Fuentes et al., Citation2020), have used it as a measure of illness-related threat more generally rather than examining individual illness beliefs in line with the model (Mimoun et al., Citation2020), or have not analysed or reported the results of the free text Cause items (Liu et al., Citation2020; Mimoun et al., Citation2020; She et al., Citation2021). To our knowledge one peer-reviewed study to date (Man et al., Citation2020) has reported data on the Cause subscale of the B-IPQ in 67 HCWs related to the COVID-19 pandemic. While this lack of data related to Cause items reflects research in this area more generally, it is recommended that the Cause items are included and analysed (Broadbent et al., Citation2015).

Given the potential for beliefs about COVID-19 to be an important component in understanding how HCWs have responded in the context of working during the pandemic, we aimed to examine HCWs beliefs about COVID-19, and qualitatively examine the causal attributions and stability of those causal attributions held by HCWs over time.

Materials and methods

Participants

HCWs were recruited from 12 hospitals and adjacent community healthcare services in the Mid-West and South of Ireland.

Initial recruitment took place between 15th April and 31 May 2020 (Wave 1). Of 640 healthcare workers who consented to take part, 408 completed the B-IPQ. A subset (n = 100) of HCWs were sampled again in August 2020 to examine the stability of the analytic framework. Subsequently a new cohort of HCWs from the same regions (n = 253) completed the B-IPQ in January 2021 (Wave 3). Ethical approval was granted by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals and HSE Limerick Hospitals ethics committee (CREC: ECM 4 (a) 09/04/2020 & ECM 3 (u) 09/04/2020 and UHL REC 041/2020) and local site approval was obtained for each of the individual hospitals and community health areas participating in the study.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were employed and working within the hospital or community setting as medical staff, HSCP, support staff, administration, or management and providing online consent to participate.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to provide information on a range of demographics including gender, age, profession (medicine and nursing, health and social care professionals (HSCP), administration, management, or support services) and the number of years working in that role.

Brief-Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ)

The B-IPQ is a 9-item self-report assessment of illness perceptions which has been used in a wide range of illness conditions (Broadbent et al., Citation2015) and in the general population and HCWs in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Liu et al., Citation2020; Man et al., Citation2020; Perez-Fuentes et al., Citation2020; Skapinakis et al., Citation2020).

Each item of the 9 B-IPQ items assesses a specific illness perception. Eight of the illness perceptions are assessed via a VAS from 0–10: Consequences, Timeline, Personal Control, Treatment Control, Illness Identity, Concern, Coherence, and Emotional Response. Higher scores represent a stronger belief in that illness perception and thus the Coherence, Personal Control and Treatment Control items are reverse scored. The final item of the B-IPQ assesses perceived ‘Causes’ related to the condition and asks participants to list their perceptions of the three most important causes of COVID-19.

Procedure

Key administrators and managers at each hospital and community site relayed an email inviting HCWs to participate in this online study in April 2020. On accessing the link to an online Qualtrics platform, HCWs were provided with an information sheet and consent form. Following online consent, participants were requested to answer screening questions, provide demographic information, and completed the B-IPQ. Participants also opted to consent to email contact at 3-month follow-up, and if so provided an email address to receive a further link to complete the questionnaire 3 months later. The email invitation was again distributed in January 2021, during the third wave of COVID-19 in Ireland (Lima, Citation2021).

Statistical analysis of B-IPQ questionnaire

IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 was utilised in the statistical analyses. Data were checked for normality and Levene’s test was used to examine homogeneity of variance between groups. Based on these examinations, parametric tests were utilised throughout the analyses except where data violated the assumptions of homogeneity of variance and nonparametric analysis was used (e.g. Kruskal-Wallis). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the sample (e.g. gender, age, occupational category). T-tests and one way ANOVA’s permitted examination of differences between groups (e.g. gender, occupational group), with post-hoc comparisons where appropriate. Correlations were processed by Pearsons correlation coefficient (e.g. age, years qualified and perceptions of COVID-19) and Chi2 utilised for examination of categorical associations. Significance levels were set at p < 0.01 to control for the possibility of type 1 error.

Qualitative analysis of HCWs perceptions of the causes of COVID-19

A template analysis approach was used to analyse the free text data in relation to participant’s perception of Causes of COVID-19 (Brooks et al., Citation2015). This involved a number of stages.

Firstly, the first 300 responses to the Cause items of the B-IPQ collated in Wave 1 were examined via a process of familiarisation, via reading and re-reading the responses. Secondly, a preliminary coding of the data was carried out using a number of existing a priori themes generated from the original IPQ & IPQ-R Cause subscales and recent data using the IPQ scales in COVID-19. On this basis, our initial coding template included 8 Cause areas: risk factors (e.g. behavioural factors, adherence to guidelines), virus specific factors (e.g. new virus, no vaccine); chance or bad luck (e.g. Act of God), environmental factors (e.g. increased urbanisation), missed opportunities for containment (e.g. lack of quarantine), human/animal disease interface, PPE-related factors, and conspiracy theories. The responses of the first 300 participants were applied to this initial template and the template modified as required by iteratively inserting new themes and redefining other categories as fresh data was worked through resulting in revision of the template (Brooks et al., Citation2015). We reached a point of satisfaction with the coding template when agreed by the authors (HLR, DGF) that all of the available data could be coded to it. The final template was applied to the entire data set, and the free responses from each participant were individually assigned one of the template category codes directly onto the database.

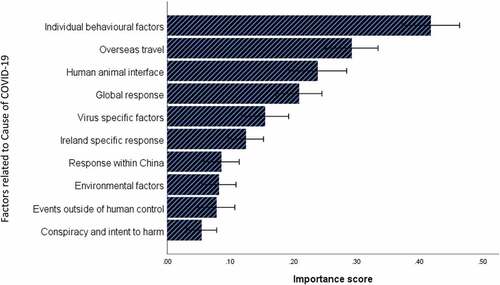

The significance of the Cause categories was further analysed utilising an importance score (IS) for each cause category (Kelly et al., Citation2020). The IS takes into account the importance assigned to each Cause category by its rank position and the frequency of being listed by HCWs. As per Kelly et al. (Citation2020) the IS was calculated by assigning a score of 1 if the particular category was ranked first by a participant, 2/3 if ranked second and 1/3 if ranked third. If the item was not ranked it was given a score of 0. The rankings for each category were then averaged, the IS ranging from 0–1, with higher scores representing the cause category most frequently reported by HCWs. For example, if ‘overseas travel’ was rated first by one participant, second by another and not at all by two other participants, the rankings would be 1, 2/3, 0 and 0 respectively, with an average (IS) of 0.42. The IS permitted analysis of both subgroups (e.g. gender, occupation) and stability of the template over time within participants at wave one and at 3 month follow-up and in a new cohort of HCWs during wave three.

Results

illustrates the demographic and work-related variables of the cohort.

Table 1. Demographic and work related variables of healthcare workers.

Perceptions of COVID-19

The mean scores for each of the illness perception dimensions are shown in .

Table 2. Mean and SD for B-IPQ at wave 1.

Female HCWs had significantly more negative emotional representations (t = −4.31, df405, p < 0.01). There was a weak correlation between HCWs who were older and stronger beliefs that they had more personal control over COVID-19 (r = 0.14, p < 0.01) and had a greater understanding of COVID-19 (r = 0.13, p < 0.01). In line with this, being qualified for a greater amount of time was weakly associated with beliefs of more personal control over COVID-19 (r = 0.15, p < 0.01). There were no significant associations between gender and occupational group (X2 = 10.86, df4, p > 0.01). Kruskal-Wallis test indicated significant differences in age across occupational groups (H = 15.02, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that HSCP staff were significantly younger than administration staff (U = 3787, p < 0.01) and managerial staff (U = 975.5, p < 0.01). There were no other significant age differences between the occupational groups.

There were statistically significant differences in perceptions about how long COVID-19 would last (Timeline) between the occupational groups (F 4,401 = 3.47, p < 0.01). Tukey-Kramer post hoc analysis indicated that administration staff believed that COVID-19 would last a significantly shorter time than medical/nursing staff (m = 0.66, 95%CI 0.02–1.3, p < 0.05) and HSCP (m = 0.75, 95%CI 0.1–1.4, p < 0.05). The perception of Treatment Control was also significant between groups (F 4,401 = 5.64, p < 0.001), with administration staff reporting that treatment would be more effective than Medical/nursing staff (m = 1.48, 95%CI 0.62–2.34, p < 0.01). There were significant differences between occupational groups in terms of Concerns about COVID-19 (F4,401 = 3.68, p < 0.01), with staff working in administration holding significantly stronger concerns than HSCP staff (m = 1.0, 95%CI 0.18–1.82, p < 0.001).

Differences between those who did and did not complete Cause subscale of IPQ

Of the 408 healthcare workers who completed the B-IPQ, 353 (87%) completed the Cause items. This completion rate is similar to previous studies (Broadbent et al., Citation2015). Thus 1059 responses to the B-IPQ Cause items were examined (three for each participant). There were no significant age, gender differences, or occupational category differences between people who completed the Cause subscale of the B-IPQ versus those who did not (p’s>0.01).

Qualitative template analysis

HCWs Perceptions of the Cause of COVID-19

From the template analysis, ten categories were identified from the 1053 responses, which classified the entirety of the data. Cause item 2 (the second most important cause of COVID-19 for me) and item 3 (the third most important Cause of COVID-19 for me) were assigned a response of ‘not specified’ if the participant responded to Cause item 1 but did not respond to item 2 or 3, or specifically stated that they did not know. The final categories arising from the analysis are outlined in .

Table 3. Perception of COVID-19 causes by healthcare staff.

The template was able to classify all of the free text responses in the subsample of the original cohort at 3 months follow-up, and during wave 3 of COVID-19 in a new cohort of HCWs. The Causes identified as most important in Wave 1, based on the IS are illustrated in and the IS for all cohorts are illustrated in .

Table 4. Perception of COVID-19 causes and mean importance scores (possible range 0–1) for each cohort.

Associations between causal perceptions, demographic and occupational related factors

The top three Cause categories identified by men were, human and animal interface (IS 0.33), individual behavioural factors (IS 0.30) and events outside of human control (IS 0.25). For women the top 3 were individual behavioural factors (IS 0.44), overseas travel (IS 0.29) and human and animal interface (IS 0.23). The only gender difference to reach significance was male healthcare workers were more likely to rate the Cause of COVID-19 as being an event outside of human control (U = 5640, p < 0.001). There were no significant associations between occupational groups and causal factors (F’s <2.50, p’s>0.01).

Younger HCWs were significantly more likely to rate individual behavioural factors as Causes of COVID-19 lower (r = −0.17, p < 0.01). Older HCWs were more likely to cite virus specific factors as a cause of COVID-19 (r = 0.16, p < 0.01). There were no other significant associations between age and causal factors (r’s<0.13, p’s>0.01).

Stability of the causal perceptions template

Paired t-tests were undertaken on the IS for the Cause categories (n = 100). The only significant difference was related to the human and animal interface factor with Wave 1 IS ranking significantly higher than the ranking for the same category at 3 month follow-up IS (t = 3.37, df99, p < 0.01). The strength of HCWs belief about the response of the Chinese authorities (t = −2.96, df658, p < 0.01), the global response (t = −5.29, df658, p < 0.001), and the human animal interface (t = −3.04, df658, p < 0.01) being the cause of COVID-19 significantly weakened between Wave 1 and Wave 3. By contrast there was a significant increase in the strength of HCWs perceptions between Wave 1 and Wave 3, about the importance of Ireland-specific response factors being the most important Cause of COVID-19 (t = 3.45, df658, p < 0.01).

Discussion

This is the first study of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic that has comprehensively and longitudinally examined HCWs common sense beliefs about COVID-19, using both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Our Healthcare worker sample covered a wide range of ages, working experience and occupational categories of HCWs, including frontline and non-patient facing staff.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, female HCWs had more negative beliefs about the emotional impact of COVID-19 than male HCWs. This is consistent with previous studies during COVID-19 suggesting that female HCWs tend to report more distress than males (Bettinsoli et al., Citation2020; Lai et al., Citation2020). This association may of course be due to male HCWs being less likely to report distress in the context of a pandemic (Conway, Citation2000), where the ‘hero’ label for HCWs has been extensively utilised (Cox, Citation2020), but also reflects previous well-established findings of gender differences in levels of reported distress (Salk et al., Citation2017). Our data showed no other associations with gender which differs from a recent large scale survey of the general public across Europe (Dias Neto et al., Citation2021). Dias Neto and colleagues found an association not only between being female and increased perceptions of emotional impact but also negative consequences, longer timeline, increased concern, increased treatment control and lower coherence (Dias Neto et al., Citation2021). However, this study was not conducted with HCWs and it may be the case that there is something about working and identifying as an HCW that influences the possible expected effects of gender on illness perceptions. It may be that HCWs as a group were exposed to information about COVID-19 as a function of their occupation, which potentially informed their perceptions. As such, perceptions of HCWs may be different to those of the general population due to the nature of their occupation-related exposure to information about COVID-19. An alternative reason for this discrepancy between HCWs perceptions in the current study the perceptions of non-HCWs (Dias Neto et al., Citation2021) might be that group identity as a HCW became more salient than gender identity in terms of how HCWs developed their common sense model of COVID-19 (Drury, Citation2020; Spears, Citation2021).

There were some mixed patterns of findings identified within some occupational roles. Administration staff believed that COVID-19 would last a significantly shorter amount of time, that treatment would be more effective, yet they had stronger concerns about COVID-19 than other patient facing groups (medical/nursing and HSCP). Previous systematic reviews have suggested that beliefs about influenza (e.g. susceptibility) differ according to HCWs occupation and setting (Bish et al., Citation2011; Koh et al., Citation2011). It may be that HCWs in administration roles dissonant beliefs were a result of managing the concern they had about COVID-19 by engaging thoughts of COVID-19 being over more quickly and the effectiveness of treatments. Alternatively this may be related to a misalignment of descriptive and injunctive norms between a perception of what is likely to be effective in the context of COVID-19 versus perceptions about what should be done (Neville et al., Citation2021). It may be the case that because of an absence of the common symbols and practices to establish a common identification with the broader group of HCWs, administration workers may have construed their identities less as part of the larger collective of HCWs and may instead have retained a potentially more individual identity, which may have impacted their perceptions differently to the other HCW group members (Spears, Citation2021; Reicher et al, Citation2021).

We found weak associations between being older or qualified longer and stronger beliefs in personal control over COVID-19. This is interesting, as it is well understood that increasing age is a risk factor for more serious consequences of the condition. While only a small proportion of our population of HCWs would have been considered to be in a higher risk grouping age wise (>60 years; 4.2%), whether this increase in personal control translates to the enactment of behaviours is unknown.

The template developed for the interpretation of the perceptions of potential Cause of COVID-19 in wave 1 was upheld at 3-month follow-up, and the stability of the template was supported during the analysis of Causal beliefs at wave 3 of COVID-19. For HCWs, the top two causal perceptions in terms of overall importance were individual behavioural factors and travel, and these two casual perceptions retained their importance for HCWs from waves 1 to 3 (April 2020 and January 2021). While HCWs during wave 1 considered the third most important cause to be the ‘human and animal interface’, data collected in the third wave from a new cohort of HCWs found ‘Ireland specific responses’ to be the third most important factor causing COVID-19. It is generally recognised that illness perceptions may change (Leventhal et al., Citation2003) as new information is appraised in the context of personal, developmental and condition related outcomes (Fortenberry et al., Citation2014).

As a method of thematic analysis, template analysis proved to be a useful approach for making sense of and analysing the free-text Cause items of the B-IPQ. The hierarchy of themes under each of the higher order categories, permitted reflection of the richness of the data, while the higher order categories allowed for further analysis as to the importance of each of these categories. The use of the a priori template based on empirical work aided the analyses by providing an initial structure that could be modified alongside the new emergent data. The only previous study we are aware of presenting the B-IPQ cause items in HCWs (Man et al., Citation2020) did not provide a methodological basis or explanation of categories to their coding of Cause items. The current study therefore presents a new and helpful method for examining and coding Cause perceptions in HCWs. The calculation of an IS was also found to be advantageous. While other approaches aiming to identify the importance of Cause items have been proposed (Lukoševičiūtė & Šmigelskas, Citation2019), the calculation of an IS permitted the comparison of causal perceptions across groups and between individuals and over time (Kelly et al., Citation2020). It is suggested that researchers wishing to fully represent the dimensions of illness perceptions consider utilising a template analysis in the analysis of free text responses of the Cause items. In the context of COVID-19, this approach has permitted us to be responsive to and represent a range of contributing factors and using the IS allowed for the inclusion of the Cause component in quantitative statistical analyses to provide important information on the full range of perceptions of COVID-19 held by HCWs.

As with any study, there are some limitations. Participants self-selected into the study from emails and websites available to HCWs in the health service and thus the findings may be subject to selection bias and we cannot state that those who had entirely different common sense models either selected into or out of the study. Secondly and relatedly, findings may not generalise to the experiences of other HCWs. Moreover, the ratio of males to females was low, which while representative of the healthcare workforce generally may have influenced the results. Nonetheless, the current study has provided novel data on the range and variance of beliefs held in relation to COVID-19 by HCWs at wave 1 (April/May 2020) to wave 3 (January 2021) and has suggested that there remains significant consistency in beliefs about the principal causes of COVID-19 across these key time points. This study has also demonstrated a coherent means to analyses the Cause items of the B-IPQ and as an important component of the CSM-SR should help us in the ongoing efforts to understand and respond to the variance in personal common sense HCWs models of COVID-19.

Ethical standards

The above study received full ethical approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hosptials and HSE Limerick Hospitals ethics committee and local site approval was obtained for each of the individual hospitals and community health areas participating in the study.

Financial support statement

The work reported in the current manuscript was supported by a grant from the Health Research Board, Ireland COV19-2020-042. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alshekaili, M., Hassan, W., Al Said, N., Al Sulaimani, F., Jayapal, S. K., Al-Mawali, A., Chan, M. F., Mahadevan, S., & Al-Adawi, S. (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes across healthcare settings in Oman during COVID-19: Frontline versus non-frontline healthcare workers. BMJ Open, 10(10), e042030. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042030

- Bettinsoli, M. L., Di Riso, D., Napier, J. L., Moretti, L., Bettinsoli, P., Delmedico, M., Moretti, L., Piazzolla, A., & Moretti, B. (2020). Mental health conditions of Italian healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 Disease Outbreak. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-being, 12(4), 1054–1073. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12239

- Bish, A., Yardley, L., Nicoll, A., & Michie, S. (2011). Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: A systematic review. Vaccine, 29(38), 6472–6484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107

- Broadbent, E., Petrie, K. J., Main, J., & Weinman, J. (2006). The brief illness perception questionnaire. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(6), 631–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020

- Broadbent, E., Schoones, J. W., Tiemensma, J., & Kaptein, A. A. (2019). A systematic review of patients’ drawing of illness: Implications for research using the common sense model. Health Psychology Review, 13(4), 406–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2018.1558088

- Broadbent, E., Wilkes, C., Koschwanez, H., Weinman, J., Norton, S., & Petrie, K. J. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the brief illness perception questionnaire. Psychology & Health, 30(11), 1361–1385. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2015.1070851

- Brooks, J., McCluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2015). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

- Chong, Y. Y., Chien, W. T., Cheng, H. Y., Chow, K. M., Kassianos, A. P., Karekla, M., & Gloster, A. (2020). The role of illness perceptions, coping, and self-efficacy on adherence to precautionary measures for COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186540

- Conway, M. (2000). On sex roles and representations of emotional experience: Masculinity, femininity and emotional awareness. Sex Roles, 43(9/10), 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007156608823

- Cox, C. L. (2020). ‘Healthcare Heroes’: Problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(8), 510. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106398

- Dias Neto, D., Nunes da Silva, A., Roberto, M. S., Lubenko, J., Constantinou, M., Nicolaou, C., Lamnisos, D., Papacostas, S., Höfer, S., Presti, G., Squatrito, V., Vasiliou, V. S., McHugh, L., Monestès, J.-L., Baban, A., Alvarez-Galvez, J., Paez-Blarrina, M., Montesinos, F., Valdivia-Salas, S., … Kassianos, A. P. (2021). Illness perceptions of COVID-19 in Europe: Predictors, impacts and temporal evolution. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 640955. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.640955

- Drury, J. (2020). Recent developments in the psychology of crowds and collective behaviour. Current Opinion in Psychology, 35, 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.02.005

- Fortenberry, K. T., Berg, C. A., King, P. S., Stump, T., Butler, J. M., Pham, P. K., & Wiebe, D. J. (2014). Longitudinal trajectories of illness perceptions among adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(7), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsu043

- Greenberg, N., Weston, D., Hall, C., Caulfield, T., Williamson, V., & Fong, K. (2021). Mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. Occup Med (Lond), 9 71(2), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqaa220.

- Hagger, M. S., Koch, S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., & Orbell, S. (2017). The common sense model of self-regulation: Meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychological Bulletin, 143(11), 1117–1154. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000118

- Hagger, M. S., & Orbell, S. (2021). The common sense model of illness self-regulation: A conceptual review and proposed extended model. Health Psychology Review, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.1878050

- Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

- Kelly, A., Tymms, K., de Wit, M., Bartlett, S. J., Cross, M., Dawson, T., De Vera, M., Evans, V., Gill, M., Hassett, G., Lim, I., Manera, K., Major, G., March, L., O’Neill, S., Scholte-Voshaar, M., Sinnathurai, P., Sumpton, D., Teixeira‐Pinto, A., … Tong, A. (2020). Patient and caregiver priorities for medication adherence in gout, osteoporosis, and rheumatoid arthritis: nominal group technique. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 72(10), 1410–1419. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24032

- Koh, Y., Hegney, D. G., & Drury, V. (2011). Comprehensive systematic review of healthcare workers’ perceptions of risk and use of coping strategies towards emerging respiratory infectious diseases. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 9(4), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00242.x

- Lai, J., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Hu, J., Wei, N., Hu, J., Wu, J., Du, H., Chen, T., Li, R., Tan, H., Kang, L., Yao, L., Huang, M., Wang, H., Wang, G., Liu, Z., & Hu, S. (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e203976–e203976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

- Leventhal, H., Brissette, I., & Leventhal, E. A. (2003). The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In L. D. Cameron & H. Leventhal (Eds.), The self-regulation of health & illness behaviour (pp. 42–60). Routledge.

- Leventhal, H., Diefenbach, M., & Leventhal, E. A. (1992). Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173486

- Leventhal, H., Phillips, L. A., & Burns, E. (2016). The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): A dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(6), 935–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2

- Lima, V. (2021). The pandemic one year on: Trends and statistics between three waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. UCD Geary Institute for Public Policy, University College Dublin, Accessed 20.May.2021. Website: https://www.ucd.ie/geary/

- Liu, H., Li, X., Chen, Q., Li, Y., Xie, C., Ye, M., & Huang, J. (2020). Illness perception, mood state and disease-related knowledge level of COVID-19 family clusters, Hunan, China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 30–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.045

- Lukoševičiūtė, J., & Šmigelskas, K. (2019). Illness perception and its changes during six months after cardiac rehabilitation: Relevance of biopsychosocial factors. European Journal of Health Psychology, 26(3), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1027/2512-8442/a000034

- Man, M. A., Toma, C., Motoc, N. S., Necrelescu, O. L., Bondor, C. I., Chis, A. F., Lesan, A., Pop, C. M., Todea, D. A., Dantes, E., Puiu, R., & Rajnoveanu, R. M. (2020). Disease perception and coping with emotional distress during COVID-19 Pandemic: A survey among medical staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134899

- Mimoun, E., Ben Ari, A., & Margalit, D. (2020). Psychological aspects of employment instability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S183–S185. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000769

- Moss-Morris, R., Weinman, J., Petrie, K., Horne, R., Cameron, L., & Buick, D. (2002). The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychology & Health, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440290001494

- Neville, F. G., Templeton, A., Smith, J. R., & Louis, W. R. (2021). Social norms, social identities and the COVID‐19 pandemic: Theory and recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(5), e12596. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12596

- Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

- Perez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Molero Jurado, M. D. M., Oropesa Ruiz, N. F., Martos Martinez, Á., Simon Marquez, M. D. M., Herrera-Peco, I., & Gazquez Linares, J. J. (2020). Questionnaire on perception of threat from COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(4), 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9041196

- Reicher, S., Hopkins, N., Stevenson, C., Pandey, K., Shankar, S., and Tewari, S. (2021), Identity enactment as collective accomplishment: Religious identity enactment at home and at a festival. British Journal of Social Psychology 60(2), 678–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12415

- Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S., & Abramson, L. Y. (2017). Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychological Bulletin, 143(8), 783–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000102

- Serrano-Ripoll, M. J., Meneses-Echavez, J. F., Ricci-Cabello, I., Fraile-Navarro, D., Fiol-deroque, M. A., Pastor-Moreno, G., Castro, A., Ruiz-Pérez, I., Zamanillo Campos, R., & Gonçalves-Bradley, D. C. (2020). Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.034

- Shahzad, F., Du, J., Khan, I., Fateh, A., Shahbaz, M., Abbas, A., & Wattoo, M. U. (2020). Perceived threat of COVID-19 contagion and frontline paramedics’ agonistic behaviour: employing a stressor-strain-outcome perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145102

- Sharma, M., Creutzfeldt, C. J., Lewis, A., Patel, P. V., Hartog, C., Jannotta, G. E.,andWahlster, S. (2020). Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of critical care resource availability and factors associated with mental well-beingduring COVID-19: Results from a US survey. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 72(10), e566–e576. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1311

- She, R., Luo, S., Lau, M. M., & Lau, J. T. F. (2021). The mechanisms between illness representations of COVID-19 and behavioral intention to visit hospitals for scheduled medical consultations in a Chinese general population. Journal of Health Psychology, 13591053211008217. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053211008217

- Skapinakis, P., Bellos, S., Oikonomou, A., Dimitriadis, G., Gkikas, P., Perdikari, E., & Mavreas, V. (2020). Depression and its relationship with coping strategies and illness perceptions during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: a cross-sectional survey of the population. Depression Research and Treatment, 2020, 3158954. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3158954

- Spears, R. (2021). Social Influence and Group Identity. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 367–390. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-070620-111818

- Spoorthy, M. S., Pratapa, S. K., & Mahant, S. (2020). Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic-A review. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119

- Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Rachor, G. S., Paluszek, M. M., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020). Fear and avoidance of healthcare workers: An important, under-recognized form of stigmatization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 75, 102289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102289

- Weinman, J., Petrie, K. J., Moss-morris, R., & Horne, R. (1996). The illness perception questionnaire: A new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychology & Health, 11(3), 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400270

- Zhang, C., Yang, L., Liu, S., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., … Zhang, B. (2020). Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(306). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306