ABSTRACT

Ontological security is the personal need to build fundamental certainty about the continuity of life events. It is central to long-term human development, particularly among adolescents in highly vulnerable communities in South Africa. We examined the cumulative effects of eight hypothesised provisions (development accelerators) in reducing the risks of ontological insecurity outcomes aligned with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets. Three waves of survey data from adolescents living in high HIV prevalence areas in South Africa were analysed. We used standardised tools to measure twelve outcomes linked to two dimensions of ontological security: mental health and violence. Sustained receipt (at baseline and follow-ups) of eight hypothesised accelerators were examined: emotional and social support, parental/caregiver monitoring, food sufficiency, accessible health care, government cash transfers to households, basic economic security, positive parenting/caregiving, and participation in extramural activities. Associations of all accelerators with outcomes were evaluated using multivariable regressions controlling for age, sex, orphanhood and HIV status, rural/urban location, and informal housing. Cumulative effects were tested using marginal effects modelling. Of 1,519 adolescents interviewed at baseline, 1,353 (89%) completed the interviews at two follow-ups. Mean age was 13.8 at baseline; 56.6% were female. Four provisions were associated with reductions in twelve outcomes. Combinations of accelerators resulted in a percentage reduction risk in individual indicators up to 18.3%. Emotional and social support, parental/caregiver monitoring, food sufficiency and accessible health care by themselves and in combination showed cumulative reductions across twelve outcomes. These results deepen an essential understanding of the long-term effects of consistent exposure to accelerators on multi-dimensional human development. They could be directly implemented by existing evidence-based interventions such as peer-based psychosocial support, parenting programmes, adolescent-responsive healthcare and food support, providing safer and healthier environments for South African adolescents to thrive.

Introduction

Adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa are at increased risks of violence exposure (Mathews et al., Citation2019) and poor mental health (Owen et al., Citation2016), posing significant threats to the human development of the world’s fastest-growing population group (UNICEF, Citation2019). Violence and mental health are intrinsically linked, and urgent action in these two key areas is required to simultaneously provide safer and healthier environments for adolescents, ranging from 10 to 24 years (Sawyer et al., Citation2018). This has led to global commitments within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to promote mental health and well-being and respond to violence against vulnerable children and adolescents. To achieve that, countries in the region have to increase their efforts. Considering this need and the several gaps faced to reach SDGs, the United Nations Development Group (UNDG) has called for identifying ‘accelerators’: scalable and evidence-based practical actions and interventions at priority areas, targeting multiple SDGs at once (UNDP, Citation2017).

The interlinked nature of mental health issues and violence exposure has been widely identified across different settings (Pierre et al., Citation2020; Tol, Citation2020). However, little attention has been given to understanding them as components that inhibit the formulation of a fundamental existential security system (Giddens, Citation1984), elaborated since early childhood and consolidated during adolescence, and to the societal mechanisms that contribute to the consolidation of secure platforms for identity development and self-actualisation (Giddens, Citation1997; Laing, Citation1990). Structuration theory emphasises that social agents elaborate this security system through a psychic investment in reproducing ordered attributes of social life, suggesting that this investment responds to a need for ontological security, an existential drive to experience the societal world as relatively safe, reliable, predictable, and intelligible (Giddens, Citation1991).

Routinisation of positive social experiences, and programmatic actions that promote them, are crucial for mitigating ontological insecurity, a concept first used to describe the experiences of those with severe mental illness (Laing, Citation1990). In adolescence, the life stage in which routinisation shifts due to the combination of societal expectations and internal transformations, experiences of marginalisation due to poverty, violence, and trauma may lead to an abrupt and unhealthy transition into adulthood (Munson et al., Citation2013). In the context of the high burden of violence experienced by a high proportion of adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa (Hillis et al., Citation2016), the foundations of ordinarily organised everyday interactions that promote ontological security, a sense of well-being that gives a sense of continuity in one’s life events, might be disturbed or severely weakened. In contexts of material scarcity and psychological adversity, adolescents face various risks when threats materialise into experiences of disrespect, violence and abuse with high costs to society (Hsiao et al., Citation2018).

Examining quantitative data through the lens of ontological security allows us to explore its two crucial dimensions in real life and identify the sustained interventions and social circumstances that can support adolescents in reaching their full potential. Particularly for examining samples with high levels of HIV infection, who face higher risks in various areas (Too et al., Citation2021), this theoretical framework supports understanding what may promote or hinder adolescents’ opportunities to build a fundamental certainty about the continuity of life events.

The present study widens the scope of the existing approaches in accelerator research in two ways: firstly, it establishes linkages between the SDG targets and a theoretical framework that captures nuances of how to interpret these goals. To our knowledge, the current study makes the first attempt to measure two unexplored dimensions of ontological security (violence and mental health), aligning them with SDG targets. Second, most studies focusing on accelerators used cross-sectional data and longitudinal data up to two time points (Chipanta et al., Citation2022; Cluver et al., Citation2019; Haag et al., Citation2022; Mebrahtu et al., Citation2021; Meinck et al., Citation2021). The current study is one of the first accelerator research using data from three time points, which could pose essential understanding of the long-term effects of consistent exposure to accelerators, enhancing their potential to be considered protective factors (Rudgard et al., Citation2022). The study objectives were to 1) evaluate the association between eight hypothesised accelerators in reductions of two or more ontological insecurity outcomes aligned with SDG targets and 2) assess whether experiencing multiple accelerators might be linked to more significant reductions in risk factors for ontological insecurity.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

This analysis draws upon individual-level data from the Mzantsi Wakho longitudinal cohort, recruited in a health sub-district in the Eastern Cape province in South Africa. Adolescents (n = 1,519) aged 10–20 (56.9% female), 1080 of whom were adolescents living with HIV, were interviewed at baseline (2014–2015), follow-up (2015–2016) and second follow-up (2017–2018). This study catchment area is characterised as a resource-limited setting with high HIV-prevalence rates (Department of Health, Citation2012). The study had high acceptability with low refusal rates (<4% at both baseline and subsequent follow-ups). We used standardised interviews and extracted prospective data from clinical records. Sampling took place in clinic and community settings, including schools, adolescents’ homes, home-based care organisations, and community-based sampling through youth programmes in villages or cities. We presented the research focus as general adolescent health and social needs to adolescents and their caregivers, and voluntary informed consent was provided by all participants 18 and over. When participants were under 18 years old, both caregiver and adolescent provided assent/consent. We co-designed the questionnaires relying on youth advisory processes (Cluver et al., Citation2021) and piloted them with adolescents from the study area. Interviewers with experience working with vulnerable youth were trained to discuss sensitive topics with adolescents. They conducted 60 to 90-min face-to-face interviews in a location chosen by participants to maximise confidentiality and safety. In light of the most recent data protection regulations, continuous research governance and data management practices are in place to protect adolescents’ personal information throughout the data life-cycle (Hertzog et al., Citation2021). Ethical approvals for data collection were obtained from Universities of Oxford (SSD/2/3/IDREC and SSD/CUREC2/12-21) and Cape Town (HREC 389/2009 and CSSR 2013/04), and the relevant provincial South African Departments of Health, Basic Education, and Social Development. Participants were given no financial incentives, but they all received a certificate, a small gift pack including soap and pencils, and refreshments, regardless of interview completion.

Measures

Ontological insecurity outcomes, hypothesised accelerators, and covariates

All measures of this study are summarised in . We identified twelve outcomes aligned with two dimensions of ontological insecurity in the data, including six mental health and six violence measures. Since data collection was initiated before 2015, outcomes were retrospectively aligned with adolescent focused SDG targets. All outcomes were coded as binary indicators for analysis purposes. We also identified eight potential development accelerators. Hypothesised accelerators were measured as consistent exposure at baseline and subsequent follow-ups based on the literature suggesting that sustained and predictable access enhances their long-term potential to protect children and adolescents in vulnerable settings (Cluver et al., Citation2020; Haag et al., Citation2022; Meinck et al., Citation2021; Toska et al., Citation2020). The analyses controlled for six covariates, pre-selected for their potential to influence ontological security levels: age (in years), sex, orphanhood status (defined as being either maternally or paternally orphaned), HIV status (determined through clinical records (Haghighat et al., Citation2021)), urban/rural location, and informal housing (either living in a shack or the streets).

Table 1. SDG targets, hypothesised accelerators, definitions and scales used in this analysis.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted in five steps using Stata 16.1, all stratified by sex. First, descriptive analyses (of frequencies and percentages for all hypothesised accelerators, SGD-aligned ontological insecurity outcomes and covariates) were conducted to compare participants who completed all three rounds of interviews with those who did not (, Supplement 1). Second, nonzero spearman correlations between outcomes were computed (Supplement 3). Third, generalized estimating equations (GEE) models with an exchangeable correlation matrix were fitted to account for correlated observations within participants (). The GEE models contained a logit link and binomial family distribution to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Models of individual outcomes included hypothesised accelerators controlled for age, sex, orphanhood and HIV status, urban/rural location, and informal housing. Fourth, all predictors associated with reductions in at least two SDG-aligned ontological insecurity outcomes were considered accelerators. Finally, we calculated adjusted predicted probabilities (95% CIs), testing for possible cumulative effects between identified accelerators, using marginal effects models with each combination of accelerators, holding covariates at their observed values (Long & Mustillo, Citation2021; ).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 3. Summary of multivariable associations between accelerators and outcomes disaggregated by sex.

Table 4. Adjusted predicted percentage probabilities for experiencing outcomes and no, one, two, three, and all accelerators, disaggregated by sex.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Of 1,353 adolescents who completed interviews at three time points 56.6% were female. Frequency distributions for sociodemographic characteristics, the prevalence of hypothesised accelerators, and SDG-aligned ontological insecurity outcomes are shown in . Participants who did not complete interviews at all three time points (n = 166) were, on average older, more likely to live in urban areas, and less likely to have lost at least one parent (Supplement 1). They were also less likely to receive emotional and social support, parental monitoring and positive parenting, cash grants, access basic needs, and participate in extramural activities. No other group differences were found. Overall, missing data were low (less than 1% for all variables), with the higher number of missing data being for substance misuse across three time points (n = 59), which might be explained due to the sensitivity of the question concerning a behaviour considered deviant. Of the analytic sample with participants who completed interviews at all time points, the mean age was 13.8 years at baseline, 15.26 at first follow up, and 16.44 at second follow up. Correlations between hypothesised accelerators and between outcomes were weak (r < 0.3), suggesting no multicollinearity (Vatcheva & Lee, Citation2016; Supplements 2 and 3).

Associations between hypothesised accelerators and outcomes

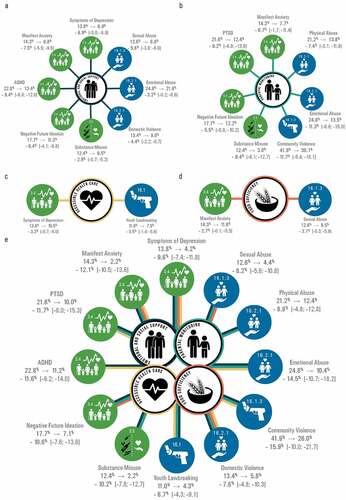

We identified four accelerators associated with reductions in ontological insecurity outcomes aligned with SDG targets (). For the whole sample, including boys and girls, emotional and social support was associated with fewer symptoms of depression, manifest anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, negative future ideation, sexual and emotional abuse, domestic violence, and substance misuse. Parental/caregiver monitoring was associated with fewer symptoms of manifest anxiety, PTSD, negative future ideation, physical and emotional abuse, experience of community violence, and substance misuse. Food sufficiency was associated with fewer symptoms of manifest anxiety and sexual abuse. Accessible health care was associated with less symptoms of depression and youth lawbreaking. Similar results were shown in the sample stratified by sex. However, food sufficiency was associated with a single outcome for girls (less symptoms of manifest anxiety) and accessible health care with a single outcome for boys (reductions in youth lawbreaking), thus not considered accelerators when stratification is taken into account. Cash grants were also associated with a single outcome for girls and boys (less sexual abuse). Other hypothesised accelerators (basic economic security, positive parenting/caregiving, and participation in extramural activities) have shown results in contradictory directions and were not proven to be accelerators ().

Predicted percentage probabilities of accelerating ontological security

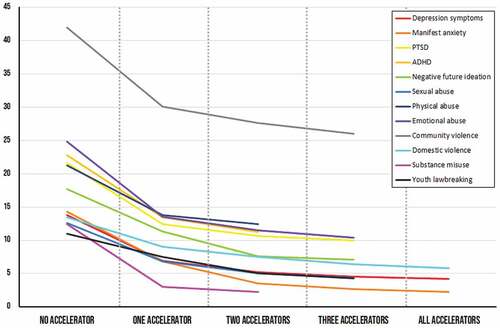

Adjusted predicted percentage probabilities for experiences outcomes and different combinations of accelerators are shown in , ). In the whole sample, accounting for girls and boys, accelerators with higher reductions were emotional and social support and parental monitoring, impacting eight and seven outcomes, respectively. Accessible health care and food sufficiency were associated with reductions in two outcomes each.

Figure 1. Accelerators modelled effects and synergy effects of all four accelerators.

Figure 2. Additive effects of accelerators on selected outcomes.

The most impactful reduction associated with receipt of emotional and social support was in the predicted probability of adolescents showing symptoms of ADHD. The probability was 22.8% (95% CI 19.5–26.0) with no accelerators. When the accelerator was present, this reduced to 13.4% (95% CI 10.8–15.9), a percentage-point reduction of 9.4 (6.8–12.0).

Parental monitoring was associated with substantial reductions across seven outcomes, with higher impacts in reducing the predicted probability in two violence outcomes (). The higher reduction associated with accessible health care was in the predicted probability of adolescents’ involvement in youth lawbreaking. Food security has shown to be associated with higher reductions in sexual abuse ( and ).

When acting in synergy, accelerators were associated with higher reductions. Seven out of the twelve impacted outcomes showed reductions above ten percentage points, and different combinations of accelerators showed higher impacts than a single accelerator present (). This pattern is observed across the twelve examined outcomes. For example, the additive effects of combining emotional and social support, parental monitoring, and accessible health care were associated with substantial reductions of 15.9% (95% CI 10.0–21.7) in exposure to community violence, 14.5% (95% CI 10.7–18.2) in experiencing emotional abuse, and a reduction of 11.7 percentage points (95% CI 8.0–15.3) in symptoms of PTSD.

Examining the sample stratified by sex, the most impacted outcome for adolescent girls was emotional abuse, associated with reductions of 18.1% (95% CI 12.7–23.5) when they received good levels of parental monitoring and emotional and social support. For boys, parental monitoring alone was associated with a reduction from 42.1% (95% CI 36.4–47.8) in experiencing community violence to 23.7% (95% CI 14.5–33.0), a reduction of 18.3% (95% CI 9.1–27.6), the higher found for an individual outcome in this study.

Discussion

Our study’s results support evidence that specific accelerators may stimulate a state of ontological security for adolescents. The identified accelerators could be translated into targeted interventions to alleviate the associated risks and intersecting vulnerabilities faced in the everyday experiences of adolescents living with HIV. We identified four accelerators for reducing the risks of ontological insecurity amongst a group of vulnerable adolescents in South Africa: emotional and social support, parental/caregiver monitoring, accessible health care, and food sufficiency. The first two have shown to be associated with higher reductions in outcomes. Additionally, we found evidence of synergistic effects when accelerators were combined, in line with other studies’ results using the accelerator approach (Cluver et al., Citation2019; Haag et al., Citation2022; Meinck et al., Citation2021). This indicates that combining accelerators may result in additional benefits for adolescents. Combined interventions may support them in consolidating a basic existential security system, responding to the need to elaborate a basic sense of certainty about the continuity of life events threatened by poor mental health and exposure to violence.

This study is subject to several limitations. First is related to the challenges of quantifying ontological security (Saunders, Citation1989). The inherent subjectivity of the concept opens multiple avenues for interpretation of the risks associated with day-to-day life. Despite the inherent difficulties in operationalising the concept, our study avoids the pitfalls of bridging theoretical constructs with factual data by focusing on two specific dimensions of ontological security, stimulated by other studies that used a similar approach in different empirical settings (Haney & Gray‐Scholz, Citation2020; Padgett, Citation2007). Second, we tested associations between accelerators and outcomes using quasi-experimental analysis, which calls for future tests in randomised experiments. The accelerators identified were not interventions but social circumstances and conditions encountered and measured in real life. The reductions in outcomes identified in our study cannot be explained as caused by accelerators. However, we hypothesised accelerators that potentially address frailties in adolescents’ lives and could be directly implemented by interventions such as promoting psychosocial support groups, parenting programmes, targeted health investments and food programmes. Third, our sample is not representative of South Africa. However, our study has in-sample variation concerning access to accelerators, SDG outcomes, and sociodemographic characteristics. Fourth, we used self-reported measures in the study, leading to potential bias. However, we used validated and piloted measures previously used in similar settings, aside from having an experienced data collection team trained to explain the purposes of the research project and encourage disclosure.

Despite such limitations, our study expands on existing evidence from South Africa, identifying accelerators that could narrow the gap between the constraints in adolescents’ lives and the commitments made by the 2030 agenda (Cluver et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Meinck et al., Citation2021). First, we identified that adolescents who receive emotional and social support and good parental monitoring are less exposed to violence and mental health issues. This is in line with a growing body of evidence that demonstrates the importance of psychosocial support and parenting programmes in child and adolescent development in sub-Saharan Africa, promoting mental health and violence prevention (Cluver et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). Second, this study identified accelerators’ synergistic effects when they acted in combination. For example, accessible health care was associated with reductions in youth lawbreaking and symptoms of depression, and food sufficiency was associated with reductions in sexual abuse and manifest anxiety. However, combination with other accelerators showed substantial reductions across twelve outcomes (). That evidence supports that adolescents will only reach their full potential if there is enough food on their plates, if they receive good parental monitoring, can access health services, and live in a supportive environment surrounded by peers and adults who pay attention to their problems and recognise them as valuable subjects, leading to individual self-realisation in safer environments.

In a resource-limited setting such as the one from our study, prioritising investments in key programme areas is crucial to increase the likelihood of converting adolescents’ potentiality into a demographic dividend estimated at US$500 billion per year in sub-Saharan Africa (UNFPA, Citation2014). This dividend relies on countries to make the right investments in adolescent human capital and adopt policies that aim to expand their opportunities.

Our study sheds light on four accelerators that had significant impacts on promoting adolescents’ ontological security, which may, in turn, enable them to elaborate positive self-identities and promote the development of their capacities. The most promising accelerator identified in our study was emotional and social support. It showed significant improvements in the two ontological security dimensions examined. As shown in , the higher impacts in adolescent outcomes occur when one accelerator is present compared to no accelerators, followed by a combination of two, three, and four accelerators that demonstrate further reductions in selected outcomes. Our study builds upon the existing evidence about psychosocial support’s positive influence on adolescents. This can be achieved by promoting interventions such as community-based organisations and parenting programmes (Cluver et al., Citation2018; Sherr et al., Citation2020), which stimulates further research to estimate the costs of promoting these interventions.

Author contributions

LH conceptualised the paper and wrote the manuscript. LH, BHB, HS, and ET conceptualised the analyses. LH conducted the analyses, and BHB, HS, and ET provided feedback on the analyses. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (144.8 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank all adolescents who participated in this study and the fieldwork teams who collected data. Acknowledgements to Prof Mark Orkin, Dr William Rudgard, and Dr Mia Saminathen for furthering methodological discussions around accelerator analyses. We thank Prof Lorraine Sherr, Dr Katharina Haag, and the Child Community Care team for inspiring the concept used in our illustrations. We also thank all members of the Accelerate Hub for their support and meaningful interactions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2022.2108079.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (1992). Manual for the child behavior checklist/2-3 and 1992 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

- Amaya-Jackson, L., McCarthy, G., Cherney, M. S., & Newman, E. (1995). Child PTSD checklist. NC: Duke University Medical Center. Durham

- Boyes, M. E., Mason, S. J., & Cluver, L. D. (2013). Validation of a brief stigma-by-association scale for use with HIV/AIDS-affected youth in South Africa. AIDS Care, 25(2), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.699668

- Chipanta, D., Estill, J. G., Stockl, H., Hertzog, L., Toska, E., Mwanza, J., Kaila, K., Matome, C., Tembo, G., Keiser, O., & Cluver, L. (2022). Associations of sustainable development goals accelerators with adolescents’ well-being according to head-of-household’s disability status – A cross-sectional study from Zambia. International Journal of Public Health, 67, 1604341. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604341

- Cluver, L. D., Meinck, F., Steinert, J. I., Shenderovich, Y., Doubt, J., Herrero Romero, R., Lombard, C. J., Redfern, A., Ward, C. L., Tsoanyane, S., Nzima, D., Sibanda, N., Wittesaele, C., De Stone, S., Boyes, M. E., Catanho, R., Lachman, J. M., Salah, N., Nocuza, M., & Gardner, F. (2018). Parenting for lifelong health: A pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial of a non-commercialised parenting programme for adolescents and their families in South Africa. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000539. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000539

- Cluver, L. D., Orkin, F. M., Campeau, L., Toska, E., Webb, D., Carlqvist, A., & Sherr, L. (2019). Improving lives by accelerating progress towards the UN sustainable development goals for adolescents living with HIV: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(4), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30033-1

- Cluver, L., Shenderovich, Y., Meinck, F., Berezin, M. N., Doubt, J., Ward, C. L., Parra-Cardona, J., Lombard, C., Lachman, J. M., Wittesaele, C., Wessels, I., Gardner, F., & Steinert, J. I. (2020). Parenting, mental health and economic pathways to prevention of violence against children in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 262 , 113194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113194

- Cluver, L. D., Rudgard, W. E., Toska, E., Zhou, S., Campeau, L., Shenderovich, Y., Orkin, M., Desmond, C., Butchart, A., Taylor, H., Meinck, F., & Sherr, L. (2020). Violence prevention accelerators for children and adolescents in South Africa: A path analysis using two pooled cohorts. PLOS Medicine, 17(11), e1003383. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003383

- Cluver, L., Doubt, J., Wessels, I., Asnong, C., Malunga, S., Mauchline, K., Vale, B., Medley, S., Toska, E., Orkin, K., Dunkley, Y., Meinck, F., Myeketsi, N., Lasa, S., Rupert, C., Boyes, M., Pantelic, M., Sherr, L., Gittings, L., Thabeng, M. (2021). Power to participants: Methodological and ethical reflections from a decade of adolescent advisory groups in South Africa. AIDS Care, 33(7), 858–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1845289

- Department of Health. (2012). The 2010 national antenatal sentinel HIV & syphilis prevalence survey in South Africa.

- DuPaul, G. J., Power, T. J., Anastopoulos, A. D., & Reid, R. (1998). ADHD rating scale—IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. Guilford Press.

- Elgar, F. J., Waschbusch, D. A., Dadds, M. R., & Sigvaldason, N. (2007). Development and validation of a short form of the alabama parenting questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(2), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9082-5

- Finkelhor, D., Hamby, S., Turner, H., & Ormrod, R. (2011). Juvenile victimization questionnaire: 2nd Revision (JVQ-R2). Government Printing Office.

- Frick, P. J. (1991). The Alabama parenting questionnaire. University of Alabama.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press.

- Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Polity press.

- Giddens, A. (1997). The consequences of modernity (6th ed.). Stanford Univ. Press.

- Haag, K., Du Toit, S., Rudgard, W. E., Skeen, S., Meinck, F., Gordon, S. L., Mebrahtu, H., Roberts, K. J., Cluver, L., Tomlinson, M., & Sherr, L. (2022). Accelerators for achieving the sustainable development goals in sub-Saharan-African children and young adolescents – A longitudinal study. World Development, 151, 105739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105739

- Haghighat, R., Toska, E., Bungane, N., & Cluver, L. (2021). The HIV care cascade for adolescents initiated on antiretroviral therapy in a health district of South Africa: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05742-9

- Haney, T. J., & Gray‐Scholz, D. (2020). Flooding and the ‘new normal’: What is the role of gender in experiences of post‐disaster ontological security? Disasters, 44(2), 262–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12372

- Hertzog, L., Wittesaele, C., Titus, R., Chen, J. J., Kelly, J., Langwenya, N., Baerecke, L., & Toska, E. (2021). Seven essential instruments for POPIA compliance in research involving children and adolescents in South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 117(9/10). https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/12290

- Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154079. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079

- Hsiao, C., Fry, D., Ward, C. L., Ganz, G., Casey, T., Zheng, X., & Fang, X. (2018). Violence against children in South Africa: The cost of inaction to society and the economy. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000573. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000573

- Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s depression inventory. Multi-Health Systems.

- Laing, R. D. (1990). The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness. Penguin books.

- Long, J. S., & Mustillo, S. A. (2021). Using predictions and marginal effects to compare groups in regression models for binary outcomes. Sociological Methods & Research, 50(3), 1284–1320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799374

- Martinez, P., & Richters, J. E. (1993). The NIMH community violence project: II. Children’s distress symptoms associated with violence exposure. Psychiatry, 56(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1993.11024618

- Mathews, S., Abrahams, N., Martin, L. J., Lombard, C., & Jewkes, R. (2019). Homicide pattern among adolescents: A national epidemiological study of child homicide in South Africa. PLOS ONE, 14(8), e0221415. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221415

- Mebrahtu, H., Skeen, S., Rudgard, W. E., Du Toit, S., Haag, K., Roberts, K. J., Gordon, S. L., Orkin, M., Cluver, L., Tomlinson, M., & Sherr, L. (2021). Can a combination of interventions accelerate outcomes to deliver on the sustainable development goals for young children? Evidence from a longitudinal study in South Africa and Malawi. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48(3), 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12948

- Meinck, F., Orkin, M., & Cluver, L. (2021). Accelerating sustainable development goals for South African adolescents from high HIV prevalence areas: A longitudinal path analysis. BMC Medicine, 19(1), 263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02137-8

- Munson, M. R., Lee, B. R., Miller, D., Cole, A., & Nedelcu, C. (2013). Emerging adulthood among former system youth: The ideal versus the real. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(6), 923–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.03.003

- Owen, J. P., Baig, B., Abbo, C., & Baheretibeb, Y. (2016). Child and adolescent mental health in sub-Saharan Africa: A perspective from clinicians and researchers. BJPsych. International, 13(2), 45–47. https://doi.org/10.1192/S2056474000001136

- Padgett, D. K. (2007). There’s no place like (a) home: Ontological security among persons with serious mental illness in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 64(9), 1925–1936. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.011

- Pierre, C. L., Burnside, A., & Gaylord-Harden, N. K. (2020). A longitudinal examination of community violence exposure, school belongingness, and mental health among African-American adolescent males. School Mental Health, 12(2), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09359-w

- Pillay, U., Roberts, B., Rule, S., & Rule, S. (2006). South African social attitudes: Changing times, diverse voices. HSRC press.

- Reynolds, C. R., & Richmond, B. O. (1978). What I think and feel: A revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 6(2), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00919131

- Rudgard, W. E., Dzumbunu, S. P., Yates, R., Toska, E., Stöckl, H., Hertzog, L., Emaway, D., & Cluver, L. (2022). Multiple Impacts of Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program on Adolescent Health and Well-Being: A Quasi-Experimental Study 2002–2013. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.04.010

- Saunders, P. (1989). The meaning of ‘home’in contemporary English culture. Housing Studies, 4(3), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673038908720658

- Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De La Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

- Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

- Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

- Sherr, L., Yakubovich, A. R., Skeen, S., Tomlinson, M., Cluver, L. D., Roberts, K. J., & Macedo, A. (2020). Depressive symptoms among children attending community based support in South Africa – pathways for disrupting risk factors. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25(4), 984–1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104520935502

- Snider, L., & Dawes, A. (2006). Psychosocial vulnerability and resilience measures for national-level monitoring of orphans and other vulnerable children: Recommendations for revision of the UNICEF Psychological Indicator. Cape Town: UNICEF. https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/Psychosocial%20Vulnerability%20and%20Resilience%20Measures%20for%20National-Level%20Monitoring%20of%20Orphans%20and%20Other%20Vulnerable%20Children.pdf

- Tol, W. A. (2020). Interpersonal violence and mental health: A social justice framework to advance research and practice. Global Mental Health, 7, e10. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2020.4

- Too, E. K., Abubakar, A., Nasambu, C., Koot, H. M., Cuijpers, P., Newton, C. R., & Nyongesa, M. K. (2021). Prevalence and factors associated with common mental disorders in young people living with HIV in sub‐Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(S2). doi:10.1002/jia2.25705

- Toska, E., Campeau, L., Cluver, L., Orkin, F. M., Berezin, M. N., Sherr, L., Laurenzi, C. A., & Bachman, G. (2020). Consistent provisions mitigate exposure to sexual risk and HIV among young adolescents in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 24(3), 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02735-x

- UNDP. (2017). SDG accelerator and bottleneck assessment tool. New York: United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/publications/sdg-accelerator-and-bottleneck-assessment

- UNFPA. (2014). The power of 1.8 billion: Adolescents, youth and the transformation of the future.

- UNICEF. (2019). Adolescent Demographics. https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/demographics/

- Vatcheva, K. P., & Lee, M. (2016). Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology: Open Access, 06(02). https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1165.1000227