ABSTRACT

Since the adoption of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by the United Nations (UN), the search has been on to identify interventions that have effects on multiple SDG-targets simultaneously. Like other developing countries, Ghana has a youthful population and would require creative, urgent, youth-focused interventions to be able to attain the SDGs by 2030. This paper describes the application of the accelerator model on data from a sample of Ghanaian adolescents to identify potential accelerators towards selected SDG targets involving youth. The data for 944 adolescents, 10–19 years (mean age 12.31 ± 3.51 years), extracted from two cross-sectional surveys on children and adolescents aged 6–19 years in Kumasi, Ghana, were analysed in this paper. Variables considered suitable proxies for SDG targets and potential accelerators were identified from the study instruments. Consequently, four aligned SDG targets (good mental health, access to ICT, school completion and no open defaecation) and five accelerators (cognitive stimulation, no relative poverty, low student–teacher ratio, high caregiver education and safe water) were extracted. Associations between accelerators and SDG targets were assessed using multivariable logistic regression adjusting for sociodemographic covariates and multiple testing. Cumulative effects were tested by marginal effects modelling. The three hypothesised accelerators identified were cognitive stimulation, low student–teacher ratio, and no relative poverty. A combination of all three accelerators was associated with a higher likelihood of adolescents having access to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) by +73% (CI 0.72–0.74), no open defecation by +44% (CI 0.43–0.46), school completion by +27% (CI 0.26–0.27) and good mental health by +9% (CI 0.08–0.10). Three hypothesized accelerators showed association across all four SDG aligned targets. The accelerator model has been further validated in this dataset from Ghana. Robust interventions designed around these accelerators may represent an opportunity for achieving the SDGs in Ghana.

Introduction

At the forefront of driving support for attaining the sustainable development goals (SDGs) is the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) through the identification of ‘accelerators’ within the framework of the ‘mainstreaming, acceleration, and policy support’ (MAPS) approach (UNSDG, Citation2016). Within this framework, an accelerator is described as any service, programme or intervention that impacts multiple SDG targets simultaneously (Cluver et al., Citation2019; UNDP, Citation2017). First, the goal is to identify which potential single interventions have significant effects across multiple targets, and then which combination of interventions have a synergistic effect in ‘accelerating progress towards specific SDG targets’ (Cluver et al., Citation2019). This paper is a contribution towards the efforts at validating this model using an existing dataset from Ghana.

The concept of accelerators for sustained progress towards the SDGs is timely. The literature is replete with evidence of the efficacy of many interventions in achieving one SDG-target (Aber et al., Citation2017). However, a new approach of targeting multiple SDGs that reinforce each other with one single intervention might be a more efficient use of resources (Nilsson et al., Citation2016), particularly given the resource constraints of many developing countries in Africa with a growing youthful population (DESA, Citation2017). Some accelerators identified in the literature include safe schools, promotion of mental health, good school performance (Devries et al., Citation2014), and parental support to reduce risky adolescent sexual behaviour, substance use and violence perpetration (World Health Organization, Citation2016). The number and type of caregivers raising children (grandparents versus biological parents, for example) were found to have an impact on SDG targets such as academic performance (Jingzhong & Lu, Citation2011; Zai & Chen, Citation2010; Zhao et al., Citation2014) and child labour (Castañeda & Buck, Citation2011; Jingzhong & Lu, Citation2011; Salah, Citation2008), although these effects may depend on the nature of kin relationships which are culture-specific (Mazzucato et al., Citation2015). This paper seeks to utilise the accelerator model on data from Ghana to determine potential accelerators towards reaching selected SDG targets.

Methodology

Data source and study location

The data used in this paper was a combination of two datasets from two separate cross-sectional studies carried out by the first author in Kumasi, Ghana (Kusi-Mensah, Citation2017). Kumasi is the second most urbanized city in Ghana, a lower-middle-income country (LMIC) in West Africa (Nyarko, Citation2014), which has a relatively high standard of living because of its strategic location in central Ghana serving as the principal inland transport terminal for the profitable business of the distribution of goods in Ghana and beyond to other West African countries. Kumasi therefore has relatively good access to basic amenities like pipe-borne drinking water, stable electricity, and reliable internet service providers, several of which are SDG-outcomes in this study.

The first was a study carried out in 2017 to establish norms for the Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices – a test for fluid intelligence (Raven & Court, Citation1998) on 614 children and adolescents aged 6–19 years in rural and urban schools. In this study, any child of school-going age within the specified age range of 6–19 years in rural and urban Kumasi was included in the study, with selection of participants being done in 11 (seven urban, four rural) private and government-run schools. The second study was a cross-sectional community-based survey carried out in 2018 to investigate the social determinants of the mental well-being of 672 children and adolescents (aged 6–17 years) in an urban inner-city community. In this study, any child aged 6–17 years who resided in Fante New Town and was given appropriate informed consent was included in the study, with recruitment being done in randomly selected households in the community. Out of the 1286 participants in both studies, data for 944 adolescents aged 10–19 years were subsequently extracted and analysed. In both studies, the same information on socio-demographic details and cognitive functioning was obtained. However, for instruments on mental health information, there were differences. The in-school study used the Patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to screen for depression and anxiety (Spitzer et al., Citation1999), while the community study utilised the Kiddies Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime version (KSADS-PL) to assess for psychiatric disorders (Kaufman et al., Citation1997). has a summary of instruments.

Table 1. SDG targets mapped from questionnaires and their measures.

Procedure

The study instruments were reviewed, and items deemed suitable as proxies for measuring different SDG targets were identified by the authors. This is summarised in .

Mapping of accelerators

Potential accelerators (Cluver et al., Citation2019) were identified from the variables collected, and all variables were converted into binary measures. In all, five potential accelerators were hypothesized for the Ghana data based on available evidence in the literature on practices or interventions that affect the well-being of adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa (Harris et al., Citation2014; Luketero & Kangangi, Citation2019; Nicholas-Omoregbe et al., Citation2010; The water project, 2018). All potential accelerators and their operational measures are presented in .

Table 2. Mapped accelerators and measures.

A detailed operational definition of such essential variables as ‘poverty’ and ‘student-teacher ratio’ can be found in the supplemental material 1.

Ethical considerations

For both datasets, ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) (Ref. No: CHRPE/AP/266/17, and Ref. No: CHRPE/AP/266/18). Informed consent was obtained from adolescents who were aged 18 years and above. For adolescents younger than 18 years, informed consent was obtained from their parents and the adolescents gave their assent. Adolescents diagnosed with a mental disorder received further clinical assessments and intervention by the study team which comprised psychiatrists.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out in four (4) stages with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 and R, an open-source data analytic software (Chambers, Citation2008; Dalgaard, Citation2008).

In step 1, descriptive statistics of all SDG-aligned targets (), hypothesized accelerators () and covariates were calculated and reported (). In step 2, multivariable logistic regressions were carried out simultaneously while adjusting for similar covariates identified from previous studies. Each model included all hypothesized accelerators and all covariates on one SDG target. In Step 3, to account for the risk of type I error from multiple-hypothesis testing, we checked that the estimated p-values were below their estimated Benjamini–Hochberg critical values specified for five tests at a false discovery rate of 10%. Collinearity was also assessed among SDG outcomes using polychoric correlations, with all being less than 0.3 indicating no multicollinearity (see supplemental material 2). In step 4, we used fitted regression models to calculate adjusted probabilities and probability differences comparing different combinations of the accelerators while holding significant covariates at their individual values, providing probabilities and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 3. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

Table 4. Frequency distribution of SDG targets.

Table 5. Bivariate correlation with predictor variables.

Table 6. Multivariable Associations Between Accelerator Protective Factors and SDG Aligned Targets.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

Of the sample of 944 adolescent participants, the mean age was 12.31 (SD ± 3.51 years), with 498 (52.8%) females and 787 (83.4%) living in urban areas. Seven Hundred Sixty Five (81.0%) were from high socioeconomic families (see ). Missing values were less than 1% for all variables.

Frequency of SDG-aligned target indicators and accelerator protective factors

Forty (4.8%) of the participants were diagnosed with a mental health condition. Eight Hundred Fourty Five (89.7%) of the participants reported that they were not engaged in open defaecation and 577 (61.1%) reported access to the internet. 580 (61.4%) reported an active reading habit, while 179 (19%) were classified as living below the poverty line. See,

Multivariable regression analysis of associations between accelerator provisions and SDG-aligned targets

shows correlations between the hypothesized accelerators (for correlations between SDG outcomes see Supplemental Material 2). All associations between the predictors (accelerators) were small (tetrachoric correlation coefficient less than 0.24) indicating no co-linearity.

shows the results of the overall multivariable regression analysis spanning the five hypothesized accelerator protective factors and four SDG aligned targets while simultaneously controlling for three (3) covariates which were age-category (early versus late adolescence), area of residence (urban versus rural) and gender (male versus female). After correcting for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, three factors (cognitive stimulation, low student–teacher ratio, and no relative poverty) emerged as hypothesized accelerators (predictors significantly associated with two or more SDG outcomes). For example, adolescents who had adequate cognitive stimulation were two times more likely to achieve school completion (OR: 2.26; CI: 1.58–3.24) and three times more likely to have Internet access (OR: 3.24; CI: 2.31–4.57). However, access to safe water, although positively associated with access to ICT (OR: 2.75; CI: 1.78–4.27), it was not associated with any other remaining SDG outcomes. See,

Data are adjusted odds ratio (95% CI, p-values). Potential accelerators were defined as predictors that were significantly associated with two or more SDG targets. None of the SDG targets were dropped after corrections for multiple comparison using the Benjamin-Hochberg corrections.

Associations of individual potential accelerators and combined synergy provisions with SDG-aligned targets

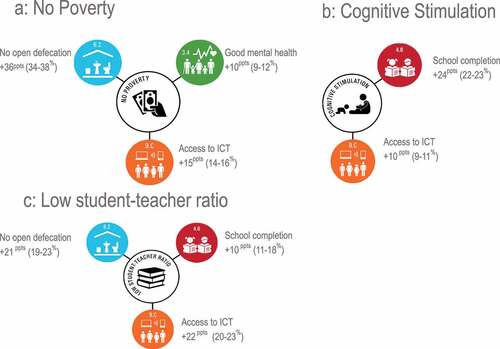

Accelerator synergies were presented for four of the SDG-aligned targets: good mental health, school completion, no open defaecation and access to ICT, in that, the chance of achieving the SDG targets increased when two or more of these accelerators were combined compared to just one accelerator. shows the marginal effect models which identified the probability of achieving the SDGs when the participant was not exposed to the accelerator versus when the participant was exposed to all three accelerators combined. For example, results showed that, whereas adolescents who had none of the accelerators had 6% likelihood of having access to ICT, those who had all the accelerators (i.e. had cognitive stimulation, were not living in poverty and had a low student–teacher ratio) had 79% likelihood (a 73% increase) of having access to ICT. Similarly, adolescents who had none of the accelerators had an 87% chance of not having a mental disorder, while those who had all three accelerators had a 96% chance of not having a mental disorder. The remaining results are shown in and summarized in .

Figure 1. Probability differences comparing adjusted probability of achieving sustainable development goals in the absence and presence of identified accelerator protective factors. The accelerator protective factors identified are no poverty (a), cognitive stimulation (b) and low student–teacher ratio (c).

Figure 2. Probability differences comparing adjusted probability of achieving sustainable development goals in the absence and presence of all three accelerator protective factors. Data are percentage point improvements (95% CI) in percentage probabilities. Double lines indicate where two protective factors are associated with an outcome, and triple lines indicate the where three protective factors are associated with outcomes. Lines are colour-coded to reflect which exact accelerators are having the effect indicated in the data reported next to the SDG-target.

Table 7. Adjusted probability of SDG outcomes considering different combinations of identified accelerator protective factors.

Data are adjusted probabilities (95% CI), except for the final row which summarises the probability difference in percentage points (95% CI) comparing a scenario with no accelerator protective factors and one with all three accelerator protective factors.

Discussion

This study on adolescents in Ghana identified cognitive stimulation, low student–teacher ratio, and no poverty as accelerator protective factors associated with a higher likelihood of reaching 4 SDG targets, with each showing positive associations across at least two SDG targets. Furthermore, three accelerators combined additively across SDG targets such that cognitive stimulation, low student–teacher ratio and not living in poverty synergised for good mental health and internet access. Cognitive stimulation and low student–teacher ratio synergised for school completion, no poverty and low student–teacher ratio synergised for no open defaecation.

Cognitive stimulation

The association between having an active reading habit (a proxy for cognitive stimulation) and self-reported access to ICT may not have an intuitive causative link on the initial examination. However, further examination suggests a bi-directional relationship with ICT exposure affecting reading ability and reading ability affecting internet access.

In one direction, exposure to ICT has been shown to improve reading self-efficacy and reading academic achievement (Walters, Citation2013). In the other direction, according to information-foraging theory, people who habitually read (because of high cognitive stimulation) seek out access to the internet more aggressively because it is a more efficient means of obtaining information about what they read (Czaja, Citation2008; Pirolli & Card, Citation1999; Sharit et al., 2011; Trewin et al., Citation2012) and are more likely to be comfortable and adept with using the internet (Sharit et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it is not difficult to imagine an adolescent engaged in active reading seeking for the use of a smartphone to enable access to the Internet for further learning. More so, given that this association remained significant after controlling for possible confounders (such as SES and parental education), the association may not simply be because adolescents of better-educated parents have greater access to books and the Internet. However, this study suggests that the connection between active reading and access to the Internet is real and independent, but this does not detract from the known dangers of excessive screen time and Internet use (Hale & Guan, Citation2015; Lissak, Citation2018).

Our study also found that Cognitive stimulation (by way of having an active reading habit) was also associated with higher cognitive functioning (by way of above age-defined average fluid intelligence scores), which has been found in the literature to be a strong predictor of the SDG target ‘school progression and completion’ (Knighton & Bussière, Citation2006; Lloyd, Citation1978; Nakajima et al., Citation2017; Polidano et al., Citation2013; Reschly, Citation2010). There is a direct connection between an active reading habit and higher cognitive functioning (Walker et al., Citation2005) bearing out findings in the present study. This lack of cognitive stimulation is also in turn linked with failure of school completion in the literature, as suggested by a study from India where the lack of reading skills by age 12 puts girls, for example, at risk of school dropout (Singh & Mukherjee, Citation2018). Indeed, reading interventions in grades 2 and 3 significantly improve high school completion (Blachman et al., Citation2014). There are other important factors associated with school completion, but the role of reading skills in school completion is clearly highlighted here.

Further, as found in this paper, there is extensive documentation on the link between reading and having a lower risk for mental disorders (another SDG target; Carroll et al., Citation2005; Martin et al., Citation2007; Maughan & Carroll, Citation2006; Willcutt & Pennington, Citation2000b). For example, children who do not read outside of school are much more likely to have externalising disorders such as ADHD (Willcutt & Pennington, Citation2000a). Carroll and colleagues (Carroll et al., Citation2005) found a robust association between reading difficulties and mental disorders such as ADHD, Conduct disorder and Anxiety disorders among both boys and girls, and self-reported depressed mood in boys. This is a significant finding particularly in a LMIC setting such as Ghana, where children from low SES backgrounds often experience significantly fewer opportunities for literacy-enriched activities and are less likely to develop intuitive reading skills (Leslie & Allen, Citation1999). Further studies are therefore warranted.

Low student–teacher ratio

The association of low student–teacher ratio with cognitive functioning and by extension school completion was unsurprising. Reducing the size of primary school classes seemed to have positively affected school completion (Rumberger & Lim, Citation2008), and educational performance (Wandera et al., Citation2020). Educational performance has been reported to be the highest predictor for dropout or completion (Lyche, Citation2010; Markussen, Citation2010; Markussen et al., Citation2008; Nakajima et al., Citation2017; Rumberger & Lim, Citation2008; Traag & Van der Velden, Citation2008), even when other factors such as SES were taken into account (OECD, O. for E. C. and D, Citation2010; Polidano et al., Citation2013; Treviño et al., Citation2010; Zoch, Citation2017). The converse (large class sizes) has also been shown to have adverse effects on school completion rates (Bickel et al., Citation2001; Buckman & Tran, Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2018; O’Sullivan & Weiss, Citation1999; Rumberger & Lim, Citation2008; Stanard, Citation2003).

This positive association between low student-teacher ratio and cognitive functioning may be explained by better one-on-one interactions (SESRIC & Alpay, Citation2014), a stronger student-teacher bond, greater teacher’s influence on the students to complete school (Ancess & Wichterle, Citation2001; Rumberger & Lim, Citation2008) and greater cognitive stimulation (Ancess & Wichterle, Citation2001). This is not to suggest, though, that student–teacher ratio and educational performance are the only predictors of school completion as several other factors (poverty, parental supervision, etc.) have also been shown in the literature to affect school dropout rate (Lyche, Citation2010). However, cognitive ability and educational performance are still the strongest predictors of school completion among these.

Low student–teacher ratio was also associated with a second SDG-target: improved ICT access, but here the picture is a bit more nuanced. There are published data to support this association even if sometimes confounded by SES (Krüger, Citation2011); although, on the other hand, both factors were significantly associated with access to ICT, it might be possible that there might have been some residual confounding if there was some measurement error in ‘no poverty’. In a similar vein, the association between low student–teacher ratio and no open defaecation is also likely not to be direct, although there is support for this association in the literature mainly because both are indicators of good-quality schools (Sachs Leventhal et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, it seems more plausible that the closer interaction that a low-student teacher ratio provides between pupils and teachers could lead to greater influence of the teacher on the sanitation habits of students, similar to the parental influence reported in several studies (Bauza et al., Citation2019), including from Ghana (Ritter et al., Citation2018; Teunis et al., Citation2016) although admittedly this is speculative.

Poverty

While not living in relative poverty showed a strong independent association with good mental health, no open defecation and improved internet access, one might consider poverty not just an ‘accelerator’ but a ‘super accelerator’ because of how broad-based and far-reaching its impact is on other accelerators as well as SDG-targets. Nonetheless, there are several anti-poverty interventions that could be explored such as cash transfers and microfinance, but these would nevertheless require high-level political commitment. However, given that the data shows an independent association with various SDG targets, poverty still needs to be addressed.

There is ample evidence in the literature to support the association between poverty and mental health difficulties (Bøe et al., Citation2014; Rutter, Citation2003; Wickham et al., Citation2016). Poverty-related factors such as food insecurity, poor economic protection and exposure to work at an early age increase the risk of children developing mental health problems (Cluver & Orkin, Citation2009; Cortina Citation2012; Das-Munshi et al., Citation2016; Omigbodun et al., Citation2010; Sturrock & Hodes, Citation2016). Specifically, parental emotional well-being and parenting practices are two potential mechanisms through which low socioeconomic status is associated with child mental health problems (Bøe et al., Citation2014; Omigbodun & Olatawura, Citation2008). It is worth observing that poverty is an underlying factor running through all the other accelerators.

Accelerator synergies and policy implications

Accelerator protective factors combined additively on 4 SDG targets: ending open defaecation, improving internet access, school completion and good mental health. The results showed a dramatic change in the probability of these outcomes in the presence of the accelerators when combined in synergy indicates that additional gains could be achieved by acting on multiple protective factors simultaneously.

The policy implications of the associations observed in this study have been alluded to previously, such as reading interventions in grades 2 and 3 significantly improving high school completion (Blachman et al., Citation2014) and, therefore, the need for not only improving access to education but also school quality (such as focusing on reading and writing skills) to solve the problem of school dropout. Shared reading programmes where parents are given an active role in encouraging reading have particularly shown real promise in encouraging reading in children (Chang et al., Citation2022). Actively promoting reading clubs, library use (both physical and virtual) and other forms of reading activities, particularly at the early education levels, is a form of cognitive stimulation and a worthwhile investment for governments and stakeholders to have maximum impact across multiple SDG goals. It may also be worthwhile to invest in the promotion of leisurely reading in school, public and virtual libraries. To improve the student–teacher ratio to OECD levels, it is also recommended that greater investment is made into teacher-training programmes at the tertiary institutions specialised in education. This would be an intervention that not only targets educational outcomes but will also drive other SDG targets for adolescents such as ending open defaecation, improving access to ICT and school completion.

This study had various strengths and limitations. The data were collected in one city (urban and rural) Kumasi, Ghana, which was a relatively wealthy cohort, hence limiting the generalizability to other parts of Ghana. The cross-sectional design means causation cannot be determined, and results need to be interpreted with caution. Finally, the measures were based on self-report, which has limited reliability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has contributed to the growing evidence for the concept of accelerators and the potentially important roles they could play in achieving the SDG targets. Robust interventions designed around these accelerators may represent the best opportunity for achieving the SDG goals, particularly for developing countries such as Ghana.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2022.2108086

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aber, J. L., Tubbs, C., Torrente, C., Halpin, P. F., Johnston, B., Starkey, L., Shivshanker, A., Annan, J., Seidman, E., & Wolf, S. (2017). Promoting children’s learning and development in conflict-affected countries: Testing change process in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Development and Psychopathology, 29(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416001139

- Ancess, J., & Wichterle, S. O. (2001). Making school completion integral to school purpose & design how severe is the problem? What do we know about intervention and prevention?. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/30j264wj#author

- Bauza, V., Reese, H., Routray, P., & Clasen, T. (2019). Child defecation and feces disposal practices and determinants among households after a combined household-level piped water and sanitation intervention in rural Odisha, India. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 100(4), 1013–1021. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.18-0840

- Bickel, R., Howley, C., Williams, T., & Glascock, C. (2001). High school size, achievement equity, and cost: Robust interaction effects and tentative results. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 9(40), 9. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v9n40.2001

- Blachman, B. A., Schatschneider, C., Fletcher, J. M., Murray, M. S., Munger, K. A., & Vaughn, M. G. (2014). Intensive reading remediation in grade 2 or 3: Are there effects a decade later? Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033663

- Bøe, T., Sivertsen, B., Heiervang, E., Goodman, R., Lundervold, A. J., & Hysing, M. (2014). Socioeconomic status and child mental health: The role of parental emotional well-being and parenting practices. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(5), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9818-9

- Buckman, D. G., & Tran, H. (2015). The relationship between school size and high school completion: A Wisconsin study. Journal of Education Policy, Planning, and Administration, 5(7), 1–16. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Buckman/publication/315610644_THE_RELATIONSHIP_BETWEEN_SCHOOL_SIZE_AND_HIGH_SCHOOL_COMPLETION_A_WISCONSIN_STUDY/links/58d52ed24585153378588b39/THE-RELATIONSHIP-BETWEEN-SCHOOL-SIZE-AND-HIGH-SCHOOL-COMPLETION-A-WISCONSIN-STUDY.pdf

- Carroll, J. M., Maughan, B., Goodman, R., & Meltzer, H. (2005). Literacy difficulties and psychiatric disorders: Evidence for comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(5), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00366.x

- Castañeda, E., & Buck, L. (2011). Remittances, transnational parenting, and the children left behind: Economic and psychological implications. The Latin Americanist, 55(4), 85-110. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1557-203X.2011.01136.x/full

- Chambers, J. M. (2008). Software for data analysis programming with R. Springer.

- Chang, M.-C., Weng, C.-Y., Yu, J.-H., Cheng, W.-L., & Chu, S.-Y. (2022). The effectiveness of a shared reading program among parents of newborns. Journal of Nursing, 69(1), 73–82. doi:10.6224/JN.202202_69(1).10

- Cluver, L., & Orkin, M. (2009). Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: Interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 69(8), 1186–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2009.07.033

- Cluver, L., Orkin, M. F., Campeau, L., Toska, E., Webb, D., Carlqvist, A., & Sherr, L. (2019). Improving lives by accelerating progress towards the UN sustainable development goals for adolescents living with HIV: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 3(4), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30033-1

- Cortina, M. A. (2012). Prevalence of child mental health problems in sub-Saharan Africa. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(3), 276. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.592

- Czaja, S. J. (2008). Usability of the medicare health web site. JAMA, 300(7), 790–792. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.7.790-b

- Dalgaard, P. (2008). Introductory statistics with R. Springer.

- Das-Munshi, J., Lund, C., Mathews, C., Clark, C., Rothon, C., Stansfeld, S., & Seedat, S. (2016). Mental health inequalities in adolescents growing up in post-apartheid South Africa: Cross-sectional survey, Shaw study. PLOS ONE, 11(5), e0154478. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154478

- DESA, U. N. (2017). World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision. Population division of the department of economic and social affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, New York. https://population.un.org/wup/publications/files/wup2014-report.pdf

- Devries, K. M., Child, J. C., Allen, E., Walakira, E., Parkes, J., & Naker, D. (2014). School violence, mental health, and educational performance in Uganda. Pediatrics, 133(1), e129–e137. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.2013-2007

- Hale, L., & Guan, S. (2015). Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 21, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SMRV.2014.07.007

- Harris, T., Sideris, J., Serpell, Z., Burchinal, M., & Pickett, C. (2014). Domain-specific cognitive stimulation and maternal sensitivity as predictors of early academic outcomes among low-income African American preschoolers. Journal of Negro Education, 83(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.83.1.0015

- Jingzhong, Y., & Lu, P. (2011). Differentiated childhoods: Impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.559012

- Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., Williamson, D., & Ryan, N. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

- Kim, Y., Joo, H. J., & Lee, S. (2018). School factors related to high school dropout. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 15(1), 59-79. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2064317197?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Knighton, T., & Bussière, P. (2006). Educational outcomes at age 19 associated with reading ability at age 15. Statistics Canada Ottawa.

- Krüger, N. (2011). The segmentation of the argentine education system: Evidence from PISA 2009. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 11(3). https://ideas.repec.org/a/eaa/eerese/v11y2011i3_3.html

- Kusi-Mensah, K. (2017). Normative data for raven’s standard progressive matrices and Slosson intelligence test among Ghanaian children. University of Ibadan.

- Leslie, L., & Allen, L. (1999). Factors that predict success in an early literacy intervention project. Reading Research Quarterly, 34(4), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.1598/rrq.34.4.2

- Lissak, G. (2018). Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: literature review and case study. Environmental Research, 164, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVRES.2018.01.015

- Lloyd, D. N. (1978). Prediction of school failure from third-grade data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 38(4), 1193–1200. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447803800442

- Luketero, S. W., & Kangangi, E. W. (2019). The factors influencing students’ academic performance in Kenya certificate of secondary education in Kirinyaga central sub-county, Kirinyaga County, Kenya. International Journal of Innovation Education and Research, 7(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.31686/ijier.vol7.iss4.1143

- Lyche, C. S. 2010. Taking on the completion challenge: A literature review on policies to prevent dropout and early school leaving. OECD Education Working Papers 53. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5km4m2t59cmr-en

- Markussen, E., Frøseth, M. W., Lødding, B., & Sandberg, N. (2008). Completion, drop-out and attainment of qualification in upper secondary vocational education in Norway. NIFU STEP Norsk institutt for studier av innovasjon. https://nifu.brage.unit.no/nifu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/283433/NIFUrapport2008-29.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1#page=33

- Markussen, E. (2010). Frafall i utdanning for 16-20 åringer i Norden. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Martin, A., Volkmar, F., & Lewis, M. (2007). Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=s9Jdn43iac8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Martin,+A.,+F.R.+Volkmar,+and+M.+Lewis,+Lewis%27s+child+and+adolescent+psychiatry:+a+comprehensive+textbook.+2007:+Lippincott+Williams+%26+Wilkins.&ots=d2lvoe4F-V&sig=kA5ukbXrR3TZFyDKns_hfy0EEec

- Maughan, B., & Carroll, J. (2006). Literacy and mental disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(4), 350–354. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000228752.79990.41

- Mazzucato, V., Cebotari, V., Veale, A., & White, A. (2015). International parental migration and the psychological well-being of children in Ghana, Nigeria, and Angola. Social Science & Medicine, 132(May 2015), 215-224. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953614007114

- Nakajima, M., Otsuka, K., & Kijima, Y. (2017). Dynamics of school progression in Andhra Pradesh, India: The role of gender and job opportunities. The 9th ASAE International Conference: Transformation in agricultural and food economy in Asia 11-13 January 2017 Bangkok, Thailand. https://doi.org/10.22004/AG.ECON.284857

- Nicholas-Omoregbe, Omoregbe, S., & Nicholas-Omoregbe, O. S. (2010). The effect of parental education attainment on school outcomes”. Ife Psychologia, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.4314/ifep.v18i1.51660

- Nilsson, M., Griggs, D., & Visbeck, M. Nature 2016 534:7607. (2016). Policy: Map the interactions between sustainable development goals. 534(7607), 320–322. https://doi.org/10.1038/534320a

- Nyarko, P. E. (2014). Ghana 2014 demographic and health survey. Maryland, USA. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/publications/2014GDHSReport.pdf

- O’Sullivan, C. Y., & Weiss, A. R. (1999). Student work and teacher practices in science. Education Statistics Quarterly, 1(2), 44–45. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9tLW9AZe0p0C&oi=fnd&pg=IA5&dq=O%E2%80%99Sullivan,+C.+Y.,+%26+Weiss,+A.+R.+(1999).+Student+work+and+teacher+practices+in+science.+Education+Statistics+Quarterly,+1(2),+44%E2%80%9345.&ots=1RnICaXc1t&sig=QDtCWHaO0a2IshnxMEvWZ-x2mlk&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- OECD, O. for E. C. and D. (2010). PISA 2009 results: What makes a school successful?: Resources, policies and practices (vol. iv).

- Omigbodun, O., Gureje, O., Ikuesan, B., Gater, R., & Adebayo, E. (1996). Psychiatric morbidity in a Nigerian paediatric primary care service: A comparison of two screening instruments. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 31(3–4), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00785766

- Omigbodun, O. O., & Olatawura, M. (2008). Child rearing practices in Nigeria: Implications for mental health. Nigerian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.4314/njpsyc.v6i1.39904

- Omigbodun, O. O., Adediran, K., Akinyemi, J., OMIGBODUN, A. O., ADEDOKUN, B. O., & ESAN, O. (2010). Gender and rural–urban differences in the nutritional status of in-school adolescents in south-western Nigeria. Journal of Biosocial. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932010000234

- Pirolli, P., & Card, S. (1999). Information foraging. Psychological Review, 106(4), 643. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.643

- Polidano, C., Hanel, B., & Buddelmeyer, H. (2013). Explaining the socio-economic status school completion gap. Education Economics, 21(3), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2013.789482

- Raven, J., & Court, J. (1998). Raven’s progressive matrices and vocabulary scales. Oxford Psychologists Press Oxford.

- Reschly, A. L. (2010). Reading and school completion: Critical connections and Matthew effects. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 26(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560903397023

- Ritter, R. L., Peprah, D., Null, C., Moe, C. L., Armah, G., Ampofo, J., Wellington, N., Yakubu, H., Robb, K., Kirby, A. E., Wang, Y., Roguski, K., Reese, H., Agbemabiese, C. A., Adomako, L. A. B., Freeman, M. C., & Baker, K. K. (2018). Within-compound versus public latrine access and child feces disposal practices in low-income neighborhoods of Accra, Ghana. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 98(5), 1250–1259. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0654

- Rumberger, R. W., & Lim, S. A. (2008). Why students drop out of school: A review of 25 years of research. University of California, Santa Barbara. https://www.issuelab.org/resources/11658/11658.pdf

- Rutter, M. (1967). A children’s behaviour questionnaire for completion by teachers: Preliminary findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1967.tb02175.x

- Rutter, M. (2003). Poverty and child mental health. JAMA, 290(15), 2063. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.15.2063

- Sachs Leventhal, K., Andrew, G., Collins, C. S., Demaria, L., Singh, H. S., & Leventhal, S. (2018). Training school teachers to promote mental and social well-being in low and middle income countries: Lessons to facilitate scale-up from a participatory action research trial of youth first in India. International Journal of Emotional Education, 10(2), 42-58. www.um.edu.mt/ijee

- Salah, M. (2008). The impacts of migration on children in Moldova. United Nations. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=The+impacts+of+migration+on+children+in+Moldova.+In+M.+A.+Salah+%28Ed.%29%2C+United+Nations+children’s+fund&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5

- SESRICAlpay, S. (2014). Education and scientific development in OIC countries 2014. The Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC). http://www.aiwsi.org/imgs/news/ESD2014FinalDGrevised_Final(1).pdf

- Sharit, J., Taha, J., Berkowsky, R. W., Profita, H., & Czaja, S. J. (2015). Online information search performance and search strategies in a health problem-solving scenario. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 9(3), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555343415583747

- Singh, R., & Mukherjee, P. (2018). ‘Whatever she may study, she can’t escape from washing dishes’: Gender inequity in secondary education–evidence from a longitudinal study in India. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 48(2), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1306434

- Smits, J., & Steendijk, R. (2015). The International Wealth Index (IWI). Social Indicators Research, 122, 65–85. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-014-0683-x

- Spitzer, R., Kroenke, K., Williams, J., & Group, P. (1999). Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Jama, 288(18), 1737–1744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

- Stanard, R. P. (2003). High school graduation rates in the United States: Implications for the counseling profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81(2), 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2003.tb00245.x

- Sturrock, S., & Hodes, M. (2016). Child labour in low- and middle-income countries and its consequences for mental health: A systematic literature review of epidemiologic studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(12), 1273–1286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0864-z

- Teunis, P. F. M., Reese, H. E., Null, C., Yakubu, H., & Moe, C. L. (2016). Quantifying contact with the environment: Behaviors of young children in Accra, Ghana. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 94(4), 920–931. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0417

- Traag, T., & Van der Velden, R. K. W. (2008). Early school-leaving in the Netherlands: The role of student-, family-and school factors for early school-leaving in lower secondary education. ROA Research Memoranda, 3. https://doi.org/10.26481/umaror.2008003

- Treviño, E., Valdés, H., Castro, M., Costilla, R., Pardo, C., & Donoso Rivas, F. (2010). Factores asociados al logro cognitivo de los estudiantes de América Latina y el Caribe. OREALC/UNESCO.

- Trewin, S., Richards, J. T., Hanson, V. L., Sloan, D., John, B. E., Swart, C., & Thomas, J. C. (2012). Understanding the role of age and fluid intelligence in information search. Proceedings of the 14th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, 119–126.

- UNDP. (2017). WHO the who framework convention on tobacco control an accelerator for sustainable development. In WHO. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/fctc/implementation/publications/who-fctc-accelerator-for-sustainable-development/en/.

- UNSDG. (2016). UNSDG | MAPS - Mainstreaming, Acceleration and Policy Support for the 2030 Agenda. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/maps-mainstreaming-acceleration-and-policy-support-2030-agenda

- Walker, S. P., Chang, S. M., Powell, C. A., & Grantham-McGregor, S. M. (2005). Effects of early childhood psychosocial stimulation and nutritional supplementation on cognition and education in growth-stunted Jamaican children: Prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 366(9499), 1804–1807. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67574-5

- Walters, J. L. 2013. English language learners’ reading self-efficacy and achievement using 1:1 Mobile learning devices [ProQuest Information & Learning]. Dissertation abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 73. 8-. https://ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2013-99030-414&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Wandera, H., Marivate, V., & Sengeh, D. (2020). Investigating similarities and differences between South African and Sierra Leonean school outcomes using Machine Learning. http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.11369

- Wickham, S., Barr, B., & Taylor-Robinson, D. (2016). Impact of moving into poverty on maternal and child mental health: Longitudinal analysis of the millennium cohort study. The Lancet, 388(Supplement 2), S4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32240-1

- Willcutt, E. G., & Pennington, B. F. (2000a). Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940003300206

- Willcutt, E. G., & Pennington, B. F. (2000b). Psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents with reading disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(8), 1039–1048. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00691

- World Health Organization. (2016). INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children.

- Zai, L., & Chen, Y. P. (2010). The educational consequences of migration for children in China. In Investing in human capital for economic development in China (pp. 159–180). World Scientific Publishing Co. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812814425_0009

- Zhao, X., Chen, J., Chen, M., Lv, X., & Jiang, Y. (2014). Left‐behind children in rural China experience higher levels of anxiety and poorer living conditions. Acta, 103(6), 665-670. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/apa.12602/full

- Zoch, A. (2017). The effect of neighbourhoods and school quality on education and labour market outcomes in South Africa. Stellenbosch University, Department of Economics. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:sza:wpaper:wpapers284