ABSTRACT

Adjustment to a Chronic Medical Condition (CMC) is associated with developing hypotheses regarding one’s symptoms, known as illness cognition (IC). Aging is associated with a higher rate of CMC. We assessed the effects of aging and psychological flexibility (PF)-one’s ability to be open to change, and to alter or persist in behaviors according to environmental circumstances – on IC development in CMC. In a cross-sectional study of hospitalized patients with CMC, 192 patients in four age groups: younger (<50), midlife (50–59), young old (60–69), and elderly (≥70) completed questionnaires sampling IC, PF and demographics. Younger participants reported less helplessness (IC) while lower scores in one PF component (perceiving reality as multifaceted) were reported by the elderly (≥70); older age was associated with a more fixed, narrow perception of reality. Both effects remained significant when using the medical condition severity as a covariate. In general, age was positively associated with IC of acceptance and Helplessness. In regression analysis, CMC severity significantly predicted all IC. Moreover, the interaction of age and perceiving reality as dynamic and changing (PF-RDC component) significantly predicted IC- acceptance of illness; follow-up analysis revealed significant correlations between PF-RDC and acceptance only for younger patients (< age 50). PF-RDC also significantly predicted IC – perceived benefit; among the entire sample higher RDC was associated with less IC – perceived benefit. Implications for theory and practice are discussed.

Introduction

Aging is associated with a greater risk of developing a chronic medical condition (CMC, Kennedy et al., Citation2014). In the U.S. in 2010, 65% of men and 72% of women above age 65 had two or more chronic illnesses (Ward & Schiller, Citation2013). The prevalence of a CMC – and multiple CMCs, in particular – increases drastically with advancing age (Jiang et al., Citation2020). CMCs and chronic diseases impose mental and economic burdens on individuals and on health care providers (Allegrante et al., Citation2019). Along with impairment in everyday functioning (Flora et al, Citation2015), a CMC often requires lifestyle changes as well as frequent communication with healthcare providers (Allegrante et al., Citation2019). However, the average rate of adherence to dietary and medication regimens, annual checkups, etc., is estimated to be as low as 50% (Brown & Bussell, Citation2011). Having a CMC has also been linked to lower levels of mental health and subjective well-being (Parks et al., Citation2020), which may be an important factor in reduced medication adherence, specifically among older people (Rodgers et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, there is a significant need for better understanding of the factors associated with the emotional and behavioral reactions of older people coping with chronic disease.

The Common-Sense Model (CSM), a theoretical conceptualization for understanding illness behavior (H. Leventhal et al., Citation1980), posits that one’s response to a health threat involves facilitation of two coping processes, at the cognitive level and the emotional level. The cognitive process includes an active effort to develop Illness cognition (IC), hypothesizing about the nature of one’s symptoms (H. Leventhal et al., Citation2003). According to CSM, these hypothesis center around five cognitive dimensions; cause (beliefs regarding the cause of the illness), consequences (the possible impact of the illness on everyday living), Identity (labeling the medical condition), personal control (beliefs regarding the ability to cure or control the disease) and timeline (beliefs regarding the expected duration of the illness). Other conceptualizations have also been developed. Evers et al. (Citation2001) suggested the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic disease draws on three dimensions; helplessness, in which one’s medical condition is perceived as uncontrollable and unpredictable; acceptance, in which one embraces a lack of control related to one’s medical condition and Perceived benefit, denoting beliefs regarding possible positive personal outcomes associated with a medical condition (Evers et al., Citation2001). Generally, previous research demonstrates that those perceiving their condition as more manageable (more acceptance, less helplessness) report better psychological and physical outcomes (Berner et al., Citation2018; Flora et al., Citation2015; Kruitwagen van Reenen et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2019; Limperg et al., Citation2020; Ozdemir et al., Citation2021; Princip et al., Citation2018; Ruksakulpiwat et al., Citation2020; Vowles et al., Citation2008 for review, see Kucukarslan, Citation2012). An additional coping channel at the emotional level may include responses such as worry and fear, which can induce additional coping strategies (e.g. distraction, or treatment-seeking) and subsequent appraisals of those coping reactions (Hagger & Orbell, Citation2021).

In spite of increasing research interest on this topic within geriatrics and health psychology, the possible effects of aging on IC are still not clear. While Citation1984) concluded that age does not affect cognitive illness appraisal among those coping with CMC (despite increasing age being associated with attenuated negative emotional responses to CMCs such as less anger and fear), other studies’ findings are inconclusive, reporting either no change in IC or improved IC (more acceptance, less helplessness) with advancing age (Hamama-Raz et al., Citation2017; Husson et al., Citation2020). In a study among gastric cancer patients, Palgi et al. (Citation2014) reported a gradual increase in acceptance among the ‘young old’ (age 60–69), compared to young (age 30–49) and midlife (age 50–59) participants; however, elderly participants (≥70 years old) reported increased helplessness and significantly more psychological distress. In accord with previous conceptualizations of aging (Birren & Cunningham, Citation1985), the authors theorized that this process of a gradual increase in acceptance with age up until the late sixties collapses around the early seventies, leading to an inability to accept illness among elderly individuals (>70 years old). This theory is corroborated by other research findings suggesting that an individual’s sense of control tends to increase from young adulthood to late midlife and then decreases rapidly around age 70 (Pudrovska, Citation2010; Wolinsky et al., Citation2003). Notwithstanding, the effect of aging on illness cognitions among those with various CMCs has yet to be examined.

Another factor suggested to affect illness-related threat evaluation is psychological flexibility (PF). Various conceptualizations of PF have been suggested, the most used of which, in research, derives from the Acceptance Commitment Therapy approach (ACT; Hayes et al., Citation1999). While it is defined by Hayes et al. (Citation2006) as the ability to accept unwanted drives, thoughts, experiences, and bodily sensations without acting upon them, others describe PF as a personal characteristic associated with adaptation capacity: the ability to adjust to fluctuating situational demands (Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010) or, alternatively, the ability to be open, present-focused, and change or persist in behaviors according to shifting internal and external circumstances (Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014). A considerable volume of research has indicated a significant association between greater PF and improved well-being/mental health indices in the context of various CMCs (Graham et al., Citation2016; Kamodya et al., Citation2018; Landstra et al., Citation2013; Maor et al., Citation2021; McCracken et al., Citation2013; Novakov, Citation2020). PF was found to mediate the association between illness cognition about the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health, among individuals all over the world (Chong, Chien, Cheng, Kassianos, et al., Citation2021; Chong, Chien, Cheng, Lamnisos, et al., Citation2021). In those studies, PF was measured by asking about coping with unwanted memories, emotions, and worries (Bond et al., Citation2011; Hayes et al., Citation2004) in accordance with the ACT approach (Hayes et al., Citation1999). However, as PF relates to several dynamic processes, it has been explored in diverse contexts (Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010) with various tools. Illness cognitions may be affected by one’s overall ability to react to change (PF). That, in turn, may change with advancing age. Thus, examining the effects of PF on the association between age and IC is warranted. In this study, we focused on the psychological flexibility questionnaire (PFQ, Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014). The PFQ was developed with relation to conceptualizing PF as a multifaceted construct that relates to an individual pattern of coping in various life situations. As such, PF can be assessed by measuring several factors, as suggested by previous authors (Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010). In a principal component extraction, PFQ items were demonstrated to be comprised of five distinct (though complementary) components, each with eigenvalue greater than 1. These components are related to self and reality (environment) perceptions as well as to the way by which self and environment interact (Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014); 1. Positive Perception of Change (PPC) – an individual inclination to perceive change in a positive way, along with the individual’s conviction about one’s ability to adapt to change. 2. Self-characterization as flexible (SAF) – i.e. perceiving oneself as attuned to external and internal changes and being able to react to these changes in a flexible and adequate manner. 3. Self-characterization as open and innovative (SOI); the level of inherent tendency to seek changes and diversity, as a possibility for development and growth. 4. Perception of reality as dynamic and changing (RDC); perceiving reality as a relative concept, constantly changing and open to various interpretations. 5. Perception of reality as multifaceted (RMF) – a disposition to adopt an integrative approach that considers the complex and multiple aspects of reality. A principal component extraction has demonstrated the unique contribution of each of these components to the overall concept of PF (Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014).

This study was designed to explore the effects of age, PF, and their possible interaction, on illness cognitions – namely acceptance, helplessness, and perceived benefit – among individuals coping with various CMCs. As mentioned above, we used the PFQ to examine attitudes towards, and coping mechanisms for, change and diversity by measuring the individual’s perceptions of self and reality as either narrow and rigid or multifaceted and flexible. In accordance with previous findings, we hypothesized that: 1. The severity of CMCs would be positively associated with the illness cognitions of helplessness, such that higher health threats lead to greater helplessness (H. Leventhal et al., Citation1980; Hagger & Orbell, Citation2021); 2. A positive association between age and more acceptance/less helplessness would be evident among non-elderly participants (<70 years old); and 3. PF would be positively associated with greater acceptance of CMCs.

Method

Participants

The study sample included 192 participants (92 females, Mage = 60.42 years) consisting of 76 participants undergoing dialysis on the nephrology ward due to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 83 participants with psoriasis from the dermatology ward and 33 participants from the geriatric ward (patients over age 70, usually suffering from high fevers, inflammation, or fractured limbs). In accordance with Palgi et al. (Citation2014), participants were divided into four age groups: younger (age 49 and below; n = 50), midlife (age 50–59; n = 29), young old (age 60–69, n = 46), and elderly (age 70 and above, n = 65). Significant differences in education level, x2(15,188) = 33.51 p = .004, and family status, x2(9, 190) = 99.33, p < .00, between the study groups were evident. presents the demographic data by age groups.

Table 1. Demographics by Age Group.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire. We asked about age, sex, education level (five-point scale), income (five point) and family status. For convenience, in , five educational level categories were consolidated into four categories, and, for income, four categories were consolidated into three categories.

Psychological Flexibility Questionnaire (PFQ)

The PFQ (Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014) includes 20 items tapping into 5 domains of PF: 1. Positive perception of change – PPC (5 items); 2. Self-characterization as flexible – SAF (5 items); 3. Self-characterization as open and innovative – SOI (3 items); 4. Perception of reality as dynamic and changing – RDC (4 items); and 5. Perception of reality as multifaceted – RMF (3 items). The items are scored on a six-point Likert scale. Scores are summed to produce a total score (higher scores indicating greater PF) and five PF subdomains. Previous research indicated high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha =.918; Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014), and satisfactory internal consistency (α Cronbach=.74) was evident in the current study.

Illness Cognition Questionnaire (ICQ)

This self-report instrument (Evers et al., Citation2001) assesses three cognitive dimensions of the experience of chronic illness: helplessness, acceptance, and perceived benefit. These dimensions may reflect either a positive or negative perception of one’s illness. Higher levels of helplessness and lower levels of acceptance have been previously associated with negative outcomes, while lesser helplessness and greater acceptance have been associated with positive outcomes on indices of self-efficacy and health related quality of life (Limperg et al., Citation2020; Sturrock et al., Citation2016). High internal consistency has been reported (Evers et al., Citation2001; Lauwerier et al., Citation2010), and satisfactory internal consistency (α Cronbach=.78) was evident in the current study.

Medical Condition Severity

Participants in this study came from three hospital wards, representing different medical conditions. To establish the relative severity of the participants’ medical conditions, nine health professionals (a chief physician in a large hospital, and eight psychologists) were asked to evaluate the average severity of their medical condition (geriatric-related condition, ESRD, psoriasis) on a five-point scale (from ‘mild’ to ‘most severe’). Raters were asked to evaluate illness severity taking into consideration the following points 1. Possible rates of mortality 2. Chances of recovery/remission 3. Possible complications 4. The levels of lifestyle adaptation needed in coping with the CMC 5. Distress levels. All of the psychologists were professionals working in the field of health/clinical psychology at the time of the study with extensive experience in these specific hospital wards and familiarity with these patients. Inter-rater reliability between the professionals was high (interclass correlation coefficients =.967, p < .01). Average severity ratings were 2 for psoriasis and the geriatric-related conditions, and 5 for ESRD.

Procedure

The medical center’s ethics committee approved the study. All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. A research assistant (psychology master’s degree student) approached patients from the three specific hospital wards in a large-sized hospital and presented the study. Patients were offered to participate in the study and, upon agreeing, provided signed informed consent.

Data analysis

Normal distribution of outcome variables was assessed in accordance with Kim (Citation2013). Chi square analysis was utilized to explore the distribution of demographics (Sex, Education Level, Income, and Family Status). Multivariate analyses of variance were used to study the effect of age group affiliation on illness cognitions (Helplessness, Acceptance, and Perceived Benefit). Additional MANOVAs were conducted to explore the effect of age group affiliation on PF factors (PPC, SAF, SOI, RDC, RMF). Analyses were conducted with and without the level of severity of the medical condition as a covariate. A correlational analysis (Pearson and Spearman) was conducted to explore the association between the study variables. Three linear regression analyses were conducted in order to explore the contribution of study factors to the explained variance in illness cognitions (helplessness, acceptance, perceived benefit). Sex, education, income, and family status were entered in the first step. Family status was indicated by three categorical variables (single, married, divorced/other/did not answer). Medical condition severity (1–5) was entered in the second step. Age and the five factors of psychological flexibility (PPC, SAF, SOI, RDC, RMF) were entered in the third step. The interactions of age with PF factors (Age*PPC, Age*SAF, Age *SOI, Age*RDC, Age*RMF) were entered in the fourth step in a stepwise manner. Regression analyses were conducted according to Dawson, (Citation2014). Continuous variables were standardized. All independent variables in the regression analysis were examined for multicollinearity.

Results

Normal distribution was evident in all continuous outcome variables. No multicollinearity of the study dependent variables was detected (all VIF’s < 2). Multivariate analysis yielded a significant effect of Age Group on Illness Cognitions, F(9,548) = 3.24, p = .01, η2p = .05. Univariate analysis indicated a significant difference in Helplessness, F(3,190) = 3.84 p = .01, η2p = .06. Bonferroni post hoc tests revealed significantly lower Helplessness scores among younger (≤ age 49) participants compared to those in midlife (age 50–59) and young old (age 60–69) groups (p < .05 in both). A significant effect of Age Group on PF was observed, F(15, 542) = 2.19, p < .01,η2p = .05. A follow-up ANOVA indicated a significant effect of Age Group for the “Psychological Flexibility – Reality as Multifaceted (PF-RMF) factor, F(1,186) = 3.80, p = .01, η2p = .06. Bonferroni post hoc testing revealed significantly lower RMF among the elderly (>70 years old) in comparison to all other age groups. The age group effects on either illness cognitions or psychological flexibility remained significant even when Medical Condition Severity was used as a covariate.

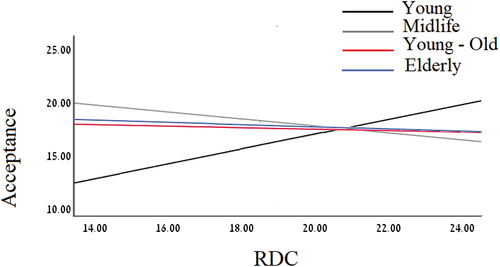

presents ICQ and PF scores as a function of Age Groups. Pearson correlation analysis (Spearman rho was used for the Sex, Education, Income, and Family Status variables) indicated a positive association between Medical Condition Severity to all illness cognitions (Helplessness, Acceptance, and Perceived Benefit), while age was positively correlated only with Helplessness and Acceptance. Given the sample size, these finding indicate a moderate association between these factors (). The results of the regression analyses for ICQ – Acceptance and ICQ – Perceived Benefit are presented in , respectively. In the final model, Education, Medical Condition Severity, and the interaction between Age Group and the Psychological Flexibility – Perception of Reality as Dynamic and Changing (PF- RDC) factor significantly contributed 21.1% to the explained variance in the ICQ – Acceptance score outcome variable (see ). In the follow-up analysis, the correlation between PF-RDC and Acceptance was tested for each Age Group separately. A significant positive correlation between PF-RDC and Acceptance was evident among participants in the young (49 years or less) age group, r = .527, n = 50, p < .000. No significant correlations between PF-RDC and Acceptance were found in the Midlife (age 50–59) (r = −.19, n = 29), Young Old (age 60–69) (r = −.06, n = 46) and Elderly (age≥70) (r = −.10, n = 65) age groups (see ).

Table 2. Illness cognition and psychological flexibility ratings by age Group.

Table 3. Correlations Between Study Variables.

Table 4. Linear regression model for ICQ-Acceptance Scores (n = 181).

Table 5. Linear regression model for ICQ-Perceived Benefit Score (n = 181).

As for the illness cognition ICQ-Perceived Benefit, in the final model, Medical Condition Severity and the Individual’s Psychological Flexibility factor of Perception of Reality as Changing and Dynamic (PF-RDC),were significantly associated with the outcome variable, explaining 14.2% of the total variance (). For ICQ-Helplessness, in the final model, only Medical Condition Severity was significantly associated with Helplessness – explaining 13.1% of the total variance – although PF-RDC marginally predicted Helplessness scores (p = .06).

Discussion

In this study of patients with various CMC’s, a robust positive association was found between the perception of reality as dynamic and changing (a psychological flexibility factor) and the individual’s level of acceptance (IC factor), but only among younger (< age 50) participants. One possible explanation for this finding is that levels of perceived control are higher among younger patients, which may impact acceptance. Previous research has suggested that an individual’s sense of control follows a curvilinear pattern throughout one’s life course, peaking in midlife and declining rapidly from later adulthood (> age 65) (Robinson & Lachman, Citation2017). It is possible that among the younger participants, greater perceived control (i.e. less helplessness), together with higher levels of perception of reality as dynamic and changing, elicited more positive appraisals of future change, leading to greater acceptance of the uncertainty associated with their CMC. Of note, though perceiving reality as dynamic and changing (PF-RDC) was associated with more acceptance among younger participants, this factor was also associated with less perceived benefit among the entire sample, regardless of age (of note, though the differences in correlation were robust, the overall contribution of PF-RDC* age interaction to IC-acceptance was quite small). Possibly, acknowledging the transient nature of reality may attenuate perceiving illness as a constant factor of negative outcomes, leading to more acceptance, particularly among younger people. On the other hand, higher perception of RDC may be associated with reduced ability of identifying illness situations as a possible path for beneficial outcome. Future studies are warranted in order to explore these issues.

Additionally, lower psychological flexibility was found among the elderly group. This finding contradicts previous studies reporting higher levels of PF with advancing age (for review, see Plys et al., Citation2022), but this contradiction may stem from different conceptualizations of PF. PF is a multifaceted construct that is often explored in different ways (Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010). Previous research in the context of various CMCs (Ekman et al., Citation2020; Hulbert-Williams et al., Citation2015) usually operationalized PF via an Acceptance Commitment Therapy approach (ACT), namely the ability to notice and accept interfering thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations without acting on them (Hayes, Citation2016). However, the current finding was derived from measuring PF via a different conceptualization: a trait-like feature relating to attitudes towards change (Ben-Itzhak et al., Citation2014). Thus, while age may be associated with enhanced ability to regulate negative emotions and thoughts (Bond et al., Citation2011; Livingstone & Isaacowitz, Citation2015) as suggested by the ACT approach, the inclination to adopt an integrative approach towards reality, perceiving it as containing multiple aspects (one of the PF factors according to the latter conceptualization) may be reduced among the elderly, possibly reflecting a more fixed, narrow perception of reality compared to younger individuals. Several preliminary suggestions can be made regarding the age specific effect only on the PF-RMF component. Perceiving reality as multifaceted and adopting a more integrative interpretation of events in the environment may rely on cognitive flexibility. Namely, the ability to flexibly alternate between perspectives, focus or responses, according to changes in task demands, which is usually compromised with advancing age (Richard’s et al., Citation2021). Alternative hypotheses are reduction of interest in the complexities of the environment, or even less motivation with age (Soutschek et al., Citation2022). Further research is advised to explore this issue.

The current findings also indicate a direct association between the chronic medical condition severity (CMS) and all domains of illness cognitions. Objective/medical evaluation of illness severity was associated with illness related outcomes such as post discharge survival rates among geriatric patients (Engvig et al., Citation2022), the level of physical fitness among patients with fibromyalgia (Estévez-López et al., Citation2015) as well as with well-being measures (depression, life satisfaction) in various CMCs (Pavon Blanco et al., Citation2019; de Gucht, Citation2015; Greco et al., Citation2015; Rose et al., Citation2012; Steca et al., Citation2013). Moreover, significant association between the individual’s subjective evaluation of his/her CMC severity and well-being has been reported (April et al., Citation2022).

The assumption regarding illness severity effects on illness cognitions is grounded within Leventhal’s CSM model (1980), denoting the consequence dimension of illness that is comprised of beliefs about the impact of the disease on everyday living. However, research examining the association between illness severity and illness cognition is scarce. Only one study reported a direct association between higher severity of irritable bowel syndrome and poorer emotional and cognitive representation of illness (Knowles et al., Citation2017). Of note, several studies have shown a mediation of illness cognition/perception on the association between illness severity and well-being (de Gucht, Citation2015; Greco et al., Citation2015; Steca et al., Citation2013). The current finding suggests that the subjective evaluation of the individual’s CMC by professionals is directly associated with his/hers perceptions of acceptance, perceived benefit and helplessness. This should be examined in future studies.

The use of the Psychological Flexibility Questionnaire (PFQ), tapping into different aspects of the construct by exploring various PF factors, along with the involvement of participants within a clinical setting, are the study’s strengths. However, several limitations also exist. While the medical condition severity variable was derived from the assessment of nine raters (one chief physician and eight psychologists experienced in working with patients with these conditions and within this particular clinical setting), additional measures, such as the individual’s illness severity score as determined by a treating physician (for example, the Acute Physiology & Chronic Health Evaluation, Knaus et al., Citation1985; Luo et al., Citation2021) as well as the individual’s own subjective rating of their illness severity, would provide a more comprehensive clinical picture. Including participants from the dermatology, geriatric and nephrology wards resulted in a sample with a wide age range, and the comparison of older with younger participants. However, different wards, representing different CMC, with diverging levels of illness severity, may be associated with different illness cognitions. Though illness severity was entered as a covariate to the analyses in this study, it might be that other factors, associated with illness type beyond severity, affected the findings. Furthermore, we did not measure time since diagnosis, which is another important factor. The relatively small sample size, the cross-sectional design, and the use of self-report measures, also constitute the study’s limitations. Future studies are suggested to use a longitudinal design, concentrate on one CMC and use a larger sample size.

The current study findings may have several clinical implications. The most interesting finding was the association between illness severity and illness cognitions, suggesting that this factor may have an important effect on the individual’s illness perception. The findings also suggest that in working with individuals with CMCs, encouraging perception of one’s situation in a more flexible way and viewing potential change as a challenge or opportunity rather than a threat, might enhance illness acceptance, particularly among younger (under age 50) patients. In addition, while older people may possess enhanced abilities to regulate their emotions, they may view potential change presented by a CMC with less versatility. While needing more affirmation from additional research, these findings may offer useful insights for health professionals to consider when assisting patients of various ages with chronic medical conditions.

Statements

Data Sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [G.Z]. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allegrante, J. P., Wells, M. T., & Peterson, J. C. (2019). Interventions to support behavioral self-management of chronic diseases. In Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044008

- April, M. E., Palmer-Wackerly, A. L., & Brock, R. L. (2022). Perceived severity of chronic illness diagnosis and psychological well-being: exploring the multiplicity and dimensions of perceived identity change. Identity, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2021.1919115

- Ben-Itzhak, S., Bluvstein, I., & Maor, M. (2014). The psychological flexibility questionnaire (PFQ): Development, reliability and validity. WebmedCentral Psychology, 5(4). WMC004606. https://doi.org/10.9754/journal.wmc.2014.004606.

- Berner, C., Erlacher, L., Fenzl, K. H., & Dorner, T. E. (2018). A cross-sectional study on self-reported physical and mental health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis and the role of illness perception. Health Quality Life Outcomes, 16(1), 238. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1064-y

- Birren, J. E., & Cunningham, W. R. (1985). Research on the psychology of aging: Principles, concepts and theory. In J. E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (2nd ed., pp. 3–34). Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire – II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688.

- Brown, M. T., & Bussell, J. K. (2011). Medication adherence: WHO cares? In Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 86(4), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575

- Chong, Y. Y., Chien, W. T., Cheng, H. Y., Kassianos, A. P., Gloster, A. T., & Karekla, M. (2021). Can psychological flexibility and prosociality mitigate illness perceptions toward COVID-19 on mental health? A cross-sectional study among Hong Kong adults. Globalization and Health, 17(43). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00692-6

- Chong, Y. Y., Chien, W. T., Cheng, H. Y., Lamnisos, D., Ļubenko, J., Presti, G., Squatrito, V., Constantinou, M., Nicolaou, C., Papacostas, S., Aydin, G., Ruiz, F. J., Garcia-Martin, M. B., Obando-Posada, D. P., Segura-Vargas, M. A., Vasiliou, V. S., McHugh, L., Höfer, S., Baban, A., Kassianos, A. P. … Kassianos, A. P. (2021). Patterns of psychological responses among the public during the early phase of covid-19: A cross-regional analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084143

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- De Gucht, V. (2015). Illness perceptions mediate the relationship between bowel symptom severity and health-related quality of life in IBS patients. Quality of Life Research, 24(8), 1845–1856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0932-8

- Ekman, U., Kemani, M. K., Wallert, J., Wicksell, R. K., Holmström, L., Ngandu, T., Rennie, A., Akenine, U., Westman, E., & Kivipelto, M. (2020). Evaluation of a novel psychological intervention tailored for patients with early cognitive impairment (PIPCI): Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 600841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600841

- Engvig, A., Wyller, T. B., Skovlund, E., Ahmed, M. V., Hall, T. S., Rockwood, K., Njaastad, A. M., & Neerland, B. E. (2022). Association between clinical frailty, illness severity and post-discharge survival: A prospective cohort study of older medical inpatients in Norway. European Geriatric Medicine, 13(2), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-021-00555-8

- Estévez-López, F., Gray, C. M., Segura-Jiménez, V., Soriano-Maldonado, A., Álvarez-Gallardo, I. C., Arrayás-Grajera, M. J., Carbonell-Baeza, A., Aparicio, V. A., Delgado-Fernández, M., & Pulido-Martos, M. (2015). Independent and combined association of overall physical fitness and subjective well-being with fibromyalgia severity: The al-Ándalus project. Quality of Life Research, 24(8), 1865–1873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0917-7

- Evers, A. W. M., Kraaimaat, F. W., van Lankveld, W., Jongen, P. J. H., Jacobs, J. W. G., & Bijlsma, J. W. J. (2001). Beyond unfavorable thinking: The illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 1026–1036. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1026

- Flora, P. K., Anderson, T. J., & Brawley, L. R. (2015). Illness perceptions and adherence to exercise therapy in cardiac rehabilitation participants. Rehabilitation Psychology, 60(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039123

- Graham, C. D., Gouick, J., Ferriera, N., & Gillanders, D. (2016). The influence of psychological flexibility on life satisfaction and mood in muscle disorders. Rehabilitation Psychology, 61(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000092

- Greco, A., Steca, P., Pozzi, R., Monzani, D., Malfatto, G., & Parati, G. (2015). The influence of illness severity on health satisfaction in patients with cardiovascular disease: The mediating role of illness perception and self-efficacy beliefs. Behavioral Medicine, 41(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2013.855159

- Hagger, M. S., & Orbell, S. (2021). The common sense model of illness self-regulation: A conceptual review and proposed extended model. Health Psychology Review, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.1878050

- Hamama-Raz, Y., Ben-Ezra, M., Tirosh, Y., Baruch, R., & Nakache, R. (2017). Illness cognition among kidney transplant recipients: A preliminary longitudinal study. In Health and Social Work, 42(3), 187–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlx028

- Hayes, S. C. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies – republished article. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., Wilson, K. G., Bissett, R. T., Pistorello, J., Toarmino, D., Polusny, M. A., Dykstra, T. A., Batten, S. V., Bergan, J., Stewart, S. H., Zvolensky, M. J., Eifert, G. H., Bond, F. W., Forsyth, J. P., Karekla, M., & Mccurry, S. M. (2004). Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record, 54(4), 553–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395492

- Hulbert-Williams, N. J., Storey, L., & Wilson, K. G. (2015). Psychological interventions for patients with cancer: Psychological flexibility and the potential utility of acceptance and commitment therapy. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12223

- Husson, O., Poort, H., Sansom Daly, U. M., Netea-Maier, R., Links, T., & Mols, F. (2020). Psychological distress and illness perceptions in thyroid cancer survivors: Does age matter? Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 9(3), 375–383. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2019.0153

- Jiang, C., Zhu, F., & Qin, T. (2020). Relationships between chronic diseases and depression among middle-aged and elderly people in China: A prospective study from CHARLS. Current Medical Science, 40(5), 858–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-020-2270-5

- Kamodya, R. C., Berlin, K. S., Rybaka, T. M., Klagesa, K. L., Banksa, G. G., Alia, J. S., Alemzadehc, R., Ferry, R. J., & Diaz Thomasc, A. M. (2018). Psychological flexibility among youth with type 1 diabetes: relating patterns of acceptance, adherence, and stress to adaptation. Behavioral Medicine, 44(4), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2017.1297290

- Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

- Kennedy, B. K., Berger, S. L., Brunet, A., Campisi, J., Cuervo, A. M., Epel, E. S., Franceschi, C., Lithgow, G. J., Morimoto, R. I., Pessin, J. E., Rando, T. A., Richardson, A., Schadt, E. E., Wyss-Coray, T., & Sierra, F. (2014). Aging: A common driver of chronic diseases and a target for novel interventions. Cell, 159(4), 709–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039

- Kim, H. -Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52

- Knaus, W. A., Draper, E. A., Wagner, D. P., & Zimmerman, J. E. (1985). APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine, 13(10), 818–829. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009

- Knowles, S. R., Austin, D. W., Sivanesan, S., Tye Din, J., Leung, C., Wilson, J., Castle, D., Kamm, M. A., Macrae, F., & Hebbard, G. (2017). Relations between symptom severity, illness perceptions, visceral sensitivity, coping strategies and well-being in irritable bowel syndrome guided by the common sense model of illness. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 22(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2016.1168932

- Kruitwagen van Reenen, E. T. H., Post MW. van Groenestijn, A., & van den Berg, L. H. Visser-Meily JM. (2020). Associations between illness cognitions and health-related quality of life in the first year after diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.109974

- Kucukarslan, S. N. (2012). A review of published studies of patients’ illness perceptions and medication adherence: Lessons learned and future directions. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 8(5), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2011.09.002

- Landstra, J. M. B., Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. P., & Hillman, R. J. (2013). Identifying and describing feelings and psychological flexibility predict mental health in men with HIV. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18(4), 844–857. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12026

- Lauwerier, E., Crombez, G., Ven Damme, S., Goubert, L., Vogelares, D., & Everts, W. M. (2010). The construct validity of the illness cognition questionnaire: The robustness of the three-factor structure across patients with chronic pain and chronic fatigue. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17(2), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9059-z

- Lee, J. Y., Jeong, D. C., Chung, N. G., & Lee, S. (2019). The effects of illness cognition on resilience and quality of life in Korean adolescents and young adults with leukemia. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 8(5), 610–615. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2018.0152

- Leventhal, E. A. (1984). Aging and the perception of illness. Research on Aging, 6(1), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027584006001007

- Leventhal, H., Brissette, I., & Leventhal, E. A. (2003). The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In L. D. Cameron & H. Leventhal (Eds.), The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour (pp. 42–65). Routledge.

- Leventhal, H., Meyer, D., Nerenz, D., & Rachman, S. (1980). The common sense representation of illness danger. In S. Rachman (Ed.), Contributions to medical psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 17–30). Pergamon Press.

- Limperg, P. F., Maurice-Stam, H., Heesterbeek, M. R., Peters, M., Coppens, M., Kruip, M. J. H. A., Eikenboom, J., Grootenhuis, M. A., & Haverman, L. (2020). Illness cognitions associated with health-related quality of life in young adult men with haemophilia. Haemophilia, 26(5), 793–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.14120

- Livingstone, K. M., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2015). Situation selection and modification for emotion regulation in younger and older adults. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(8), 904–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615593148

- Luo, Y., Wang, Z., & Wang, C. (2021). Improvement of APACHE II score system for disease severity based on XGBoost algorithm. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-021-01591-x

- Maor, M., Zukerman, G., Amit, N., Richard, T., & Ben-Itzhak, S. (2021). Psychological well-being and adjustment among type 2 diabetes patients – the role of psychological flexibility. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2021.1887500

- McCracken, L. M., Gutiérrez-Martínez, O., & Smyth, C. (2013). “Decentering” reflects psychological flexibility in people with chronic pain and correlates with their quality of functioning. Health Psychology, 32(7), 820–823. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028093

- Novakov, I. (2020). Emotional state, fatigue, functional status and quality of life in breast cancer: Exploring the moderating role of psychological inflexibility. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 26(7), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1842896

- Ozdemir, S., Lee, J. J., Malhorta, C., Teo, I., Yeo, K. K., Than, A. U. N. G., Sim, K. L. D., & Finkelstein, E. (2021). Associations between prognostic awareness, acceptance of Illness, and psychological and spiritual well-being among patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 28(5), 736–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.08.026

- Palgi, Y., Ben-Ezra, M., Hamama-Raz, Y., Shacham Shmueli, E., & Shrira, A. (2014). The effect of age on illness cognition, subjective well-being and psychological distress among gastric cancer patients. Stress and Health, 30(4), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2521

- Parks, A. C., Williams, A. L., Kackloudis, G. M., Stanford, J. L., Boucher, E. M., & Honomichl, R. D. (2020). The effects of a digital well-being intervention on patients with chronic conditions: Observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(1), e16211. https://doi.org/10.2196/16211

- Pavon Blanco, A., Turner, M. A., Petrof, G., & Weinman, J. (2019). To what extent do disease severity and illness perceptions explain depression, anxiety and quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa? The British Journal of Dermatology, 180(2), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17123

- Plys, E., Jacobs, M. L., Allen, R. S., & Arch, J. J. (2022). Psychological flexibility in older adulthood: A scoping review. Aging & Mental Health, 27(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2022.2036948

- Princip, M., Gattlen, C., Meister Langraf, R. E., Schnyder, U., Znoj, H., Barth, J., Schmid, J. P., & von Känel, R. (2018). The role of illness perception and its association with posttraumatic stress at 3 months following acute myocardial infarction. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 941. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00941

- Pudrovska, T. (2010). Cancer and mastery: Do age and cohort matter? Social Science and Medicine, 71(7), 1285–1291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.029

- Richard’s, M. M., Krzemien, D., Valentina, V., Vernucci, S., Zamora, E. V., Comesaña, A., García Coni, A., & Introzzi, I. (2021). Cognitive flexibility in adulthood and advanced age: Evidence of internal and external validity. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 28(4), 28(4. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2019.1652176

- Robinson, S. A., & Lachman, M. E. (2017). Perceived control and aging: A mini-review and directions for future research. Gerontology, 63(5), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1159/000468540

- Rodgers, J. E., Thudium, E. M., Beyhaghi, H., Sueta, C. A., Alburikan, K. A., Kucharska-Newton, A. M., Chang, P. P., & Stearns, S. C. (2018). Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly: The role of mental health. Medical Care Research and Review, 75(6), 746–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558717696992

- Rose, M. R., Sadjadi, R., Weinman, J., Akhtar, T., Pandya, S., Kissel, J. T., & Jackson, C. E. (2012). Role of disease severity, illness perceptions, and mood on quality of life in muscle disease. Muscle & Nerve, 46(3), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.23320

- Ruksakulpiwat, S., Liu, Z., Yue, S., & Fan, Y. (2020). The association among medication beliefs, perception of illness and medication adherence in ischemic stroke patients: A cross-sectional study in China. Patient Preference and Adherence, 14, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S235107

- Soutschek, A., Bagaihni, A., Hare, T. A., & Tobler, P. N. (2022). Reconciling psychological and neuroscientific accounts of reduced motivation in aging. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(4), 17(4. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsab101

- Steca, P., Greco, A., Monzani, D., Politi, A., Gestra, R., Ferrari, G., Malfatto, G., & Parati, G. (2013). How does illness severity influence depression, health satisfaction and life satisfaction in patients with cardiovascular disease? The mediating role of illness perception and self-efficacy beliefs. Psychology and Health, 28(7), 765–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2012.759223

- Sturrock, B. A., Xie, J., Holloway, E. E., Hegel, M., Casten, R., Mellor, D., Fenwick, E., & Rees, G. (2016). Illness cognitions and coping self-efficacy in depression among persons with low vision. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 57(7), 3032–3038. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-19110

- Vowles, K. E., McCracken, L. M., & Eccleston, C. (2008). Patient functioning and catastrophizing in chronic pain: The mediating effects of acceptance. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 27(2S), S136–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S136

- Ward, B. W., & Schiller, J. S. (2013). Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: Estimates from the national health interview survey, 2010. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10(4), E65.

- Wolinsky, F. D., Wyrwich, K. W., Babu, A. N., Kroenke, K., & Tierney, W. M. (2003). Age, aging, and the sense of control among older adults: A longitudinal reconsideration. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(4), S212–220. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.4.S212