ABSTRACT

Interprofessional simulation has been linked to improved self-efficacy, communication, knowledge and teamwork skills in healthcare teams. However, there are few studies that synthesize learners’ perceptions of interprofessional simulation-based approaches and barriers or facilitators they encounter in such learning approaches. The aim of this review was to explore these issues through synthesis of the published literature on healthcare staff engaging in interprofessional simulation to inform enhancement of instructional design processes. Searches of four major databases resulted in the retrieval of 2,727 studies. Following screening and full-text review, a total of 13 studies were included in the final review and deductive content analysis was used to collate the findings, which were then synthesized using a narrative approach. Three categories of barriers and facilitators were identified: characteristics of the simulation learning process, outcomes of interprofessional simulation, and interprofessional dynamics. Related to the latter, the findings indicate the instructional design of interprofessional simulation-based approaches may benefit from a greater focus on the context of healthcare teams that prioritizes teamwork. Furthermore, greater emphasis on designing realistic clinical situations promotes effectiveness of simulation. It is important to recognize the perspectives of healthcare team members engaging in these learning approaches and how they may affect clinical performance and influence patient outcomes.

Introduction

Traditional classroom-based education approaches with healthcare teams often fail to translate to practical settings as the classroom can enforce roles and habits which do not align with the concept of active treatment required by modern healthcare teams (Griffiths & Ursick, Citation2004; Issenberg & Scalese, Citation2014). Institute of Medicine’s seminar report on patient safety, ‘To Err is to Human’ (1999), underlined the need for healthcare professionals to work and train in multidisciplinary teams. Healthcare professionals need to learn to work interprofessionally in order to improve quality and safety and evince better outcomes for patients (Eppich & Schmutz, Citation2019; Reeves et al., Citation2013). Interprofessional simulation approaches have been suggested as a strategy to improve healthcare teams’ preparation for clinical situations (Donaldson, Citation2009; MacKinnon, Citation2011; Reese et al., Citation2010).

Simulation has been defined as “a near representation of an actual life event … may be presented by using computer software, role play, case studies or games that represent reality and actively involve learners in applying the content of the lesson” and “replicate some or nearly all of the essential aspects of a clinical situation so that the situation may be more readily understood and managed when it occurs for real in clinical practice” (Hovancsek, Citation2007, p. 3). The goal of human simulation is to imitate real-life situations through skills-focussed clinical experience in a safe and secure environment to limit potential harm to patients (Fowler-Durham & Alden, Citation2008). Simulation is often employed using manikins or advanced software in order to support consolidation of learning and developing competence (Hogg et al., Citation2006; Issenberg et al., Citation2005; Kardong-Edgren et al., Citation2008; Rabøl et al., Citation2010).

Background

Simulation has been employed for educational purposes in three primary domains: (i) practice and assessment of technical based procedures, (ii) teaching of clinical skills using simulated patients for performance-based assessment and (iii) team training and interprofessional education to improve teamwork and communication (Aggarwal et al., Citation2010). Simulation aims to improve patient safety by separating learner development from patient care and providing standardized and structured exposure to patient conditions and procedures and improved delivery methods (Rosen et al., Citation2010). Simulators can vary from low fidelity to high fidelity depending on their relation to reality whereby fidelity refers to “the extent to which the appearance and behaviour of the simulator⁄simulation match the appearance and behaviour of the simulated system” (Maran & Glavin, Citation2003, p. 23). For example, low-fidelity simulation may employ role-play or case studies (Kinney & Henderson, Citation2008) and high-fidelity simulation utilize computerized manikins which replicate human anatomy and can be programmed to imitate vital signs (Hovancsek, Citation2007). Simulation has been proven to be an effective way to improve skills from surgical procedures (Dunkin et al., Citation2007; Kneebone et al., Citation2002; Nackman et al., Citation2003; Sturm et al., Citation2008) to patient communication (Kneebone et al., Citation2006). Simulation has also been linked with additional gains in knowledge, critical thinking, ability, satisfaction or confidence among nurses (Cant & Cooper, Citation2010; Anderson, Citation2007).

Simulation-based learning approaches have been identified as effective tools for training in healthcare in a variety of disciplines (Gardner & Raemer, Citation2008; Cumin et al., Citation2013). However, there is still a lack of robust evidence linking interprofessional simulation-based approaches to improved multidisciplinary professional practice and patient outcomes (Reeves et al., Citation2013). Given the concern over the challenges and implications of wide-scale simulation implementation (Merién et al., Citation2010), qualitative evidence may hold the key to identifying how simulation approaches to education can elicit transfer of knowledge and skills to real-world and patient outcomes through greater knowledge support and improved instructional design (Yardley & Dornan, Citation2012).

Modern education with interprofessional teams would benefit from adopting principles grounded in adult learning as teaching strategies are more effective when learners see a direct relevance between the interprofessional learning paradigm and their future work practice (Barr & Learning and Teaching Support Network Centre of Health Sciences and Practice, Citation2001; D’Eon, Citation2005). Given the evolving nature of healthcare teams and need to embrace more inclusive interprofessional work practices (Eppich & Schmutz, Citation2019; Reeves et al., Citation2013), there is growing evidence outlining the benefits of interprofessional simulation. Interprofessional simulation has been shown to increase self-efficacy and communication, knowledge and teamwork skills and provide the “confidence to close the loop in patient care” (Tofil et al., Citation2014, p. 189) among nursing and medical students and healthcare professionals (Stewart et al., Citation2010). Visser et al.’s (Citation2017) paper, which aimed to identify facilitators and barriers that residents, medical and nursing students perceive in their interprofessional education paradigms, recommended that modern curricula integrate the reality of working in interprofessional teams by encouraging improved interprofessional collaboration in education. Interprofessional simulation has been specifically identified as an effective method of interprofessional learning which results in improved clinical knowledge, interprofessional collaboration and patient outcomes when compared with other instructional paradigms (Cook et al., Citation2013).

Simulation has been credited with improved communication between professions (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2011), increased learner engagement (Zhang et al., Citation2011) and improved team performance and knowledge (Capella et al., Citation2010). For interprofessional simulation approaches to be successful, stakeholder engagement of healthcare staff is paramount. While there has been significant focus on the outcomes of interprofessional simulation approaches, the perceptions and experiences of interprofessional simulation among healthcare members constitute a significant gap in the literature (Rabøl et al., Citation2010). Rich qualitative data from various clinical settings are essential to ensure that interprofessional training opportunities are contextual and provide an effective reflection of the complexities of the modern workplace (Sharma et al., Citation2011). Qualitative research may hold the key to a greater understanding of the effective components of simulation which lead to improved patient outcomes and can then inform interventions to test best practices (Cook et al., Citation2013; Rabøl et al., Citation2010). The objectives of implementing simulation must be aligned with the needs of learners and the goals of trainers alongside ensuring participants are engaged in a way that cognitively best reflects the actual task at hand (Schmidt et al., Citation2013).

This review presents a narrative synthesis of qualitative research exploring team members’ perceptions of interprofessional simulation techniques with a particular focus on the barriers and facilitators to the success and effectiveness of interprofessional simulation. Healthcare workers have a unique insight into the effectiveness and practicality of interprofessional simulation techniques and can inform education programme design, implementation strategies and future research in this area. The aim of this review is to identify effective components of instructional design as well as barriers and facilitators (identified by simulation participants) to effective learning transfer as a result of participating in interprofessional simulation training.

Methods

Search strategy

An initial scoping search for papers which addressed interprofessional simulation practices was carried out using Google Scholar. Previous research has highlighted the value of Google scholar for identifying relevant literature, but emphasized the advantages of using major academic databases for a thorough retrieval of relevant studies (Haddaway et al., Citation2015). A more refined strategy was developed as a result of this search through identification of key terms. Comprehensive searches were performed using PubMed, Web of Science, PsychInfo and CINAHL Plus to identify relevant studies using key terms related to interprofessional simulation approaches: “simulation”, “interprofessional”, “multidisciplinary”, “high-fidelity”, “low-fidelity” alongside terms related to healthcare teams and healthcare institutions. Searches did not restrict year of publication. Titles and abstracts were screened by three reviewers [redacted for peer review] to identify relevant articles. Articles which met the inclusion criteria (outlined below) were reviewed and a decision regarding relevance for inclusion in the analysis was made. Finally, the reference list of included papers was examined to identify other potentially relevant papers.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they presented qualitative data concerning the perspectives and experiences of healthcare workers who were involved in interprofessional simulation, were written in English, and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Eligible papers were restricted to qualitative empirical studies which included a clear description of sampling strategy, data collection and identification of the data analysis methodology in order for judgments to be made about the quality and rigour of reviewed studies.

Exclusion criteria

Editorials, reviews and papers that were not based on actual healthcare workers’ experiences of interprofessional simulation, quantitative-only studies or studies published in a language other than English were excluded from the analysis. Studies were excluded if we were unable to determine the sampling strategy, data collection tool, if the qualitative data collection method was not reported on or information on how the data were analyzed.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from each study using a data extraction template that included the following information: author(s), year of publication, location of study, country of study, number/information on participants in study, qualitative data collection methods, perceived benefits and facilitators and perceived challenges/barriers to approach.

Content analysis

Deductive content analysis was used to interpret the data. Content analysis is a systematic and objective method through which topics, words, phrases or other units of content can be distiled into meaningful categories to examine the representation (and quantitatively summarize content) of an issue (Neuendorf, Citation2016. In a deductive approach, categories are devised in advance of the analysis. The first and second author devised the coding framework and trained together in coding. Three overarching coding categories were predetermined based on the extant literature: (i) factors related to the learning process; (ii) factors related to perceived outcomes of simulation; and (iii) factors related to the interprofessional dynamic of training. Facilitators were defined as any factors which encouraged achievement of goals and learning outcomes. Barriers were defined as any factors which prevented the successful achievement of learning outcomes. The first author conducted the coding and to ensure credibility, dependability, and confirmability of the findings, this was checked by the second author. Independent coding of a subset of data (~20%) helped to ensure credibility of the analysis (through analyst triangulation). High levels of agreement were evident between coders. Instances of disagreement mainly related to organization of coding and the thematic structure and were resolved through discussion. The first author presented findings regularly as analysis progressed to enable discussion to clarify and finalize themes and findings. The use of quotes as supportive evidence demonstrates the relevance of each theme and sub-theme, highlighting the common patterns evident in the data.

The findings are reported as a narrative review of the literature. A narrative review confers several advantages over a traditional systematic review as where the purpose of a typical systematic review is to address a narrowly focused research question, a narrative review facilitates interpretation, critique and deepening of understanding (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2018) and is more thematic and conceptual in nature (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). As such, a narrative approach is most appropriate to address the research question.

Results

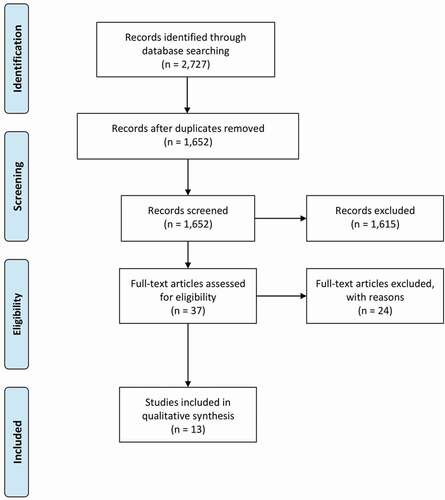

The literature search, which was completed between 3 and 10 December 2017, returned 2,727 papers. Thirteen papers were included in the review after removing duplicate papers and applying the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Stages of the literature search process are detailed in . provides an overview and summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Barriers and facilitators are organized around three primary themes: characteristics of the simulation learning process, outcomes of interprofessional simulation and interprofessional dynamics. presents a summary of the number of studies which contained barriers, facilitators and categories, as synthesized below and summarizes the key barriers and facilitators under each theme.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

Table 2. Number of studies per level and category

Table 3. Key barriers and facilitators identified

Facilitators

In discussion of key facilitators to effective learning from simulation, we organize findings in sub-themes related to characteristics of the simulation learning process, outcomes of interprofessional simulation, and interprofessional dynamics.

Characteristics of the simulation learning process

Realism: Participants in simulation reported that the fidelity of clinical scenarios allowed them to carefully observe their peers and improve their clinical skills and interprofessional simulation (Koo et al., Citation2014). The realistic nature of the training provided participants with insight into their own roles and responsibilities using real-world examples of healthcare processes of care delivery (Egenberg et al., Citation2017; Leonard et al., Citation2010; Wehbe-Janek et al., Citation2012). One participant reported that “going through the sequence of events and seeing how others perform gave me insight and a realistic impression” (Wehbe-Janek et al., Citation2012). Realism of situations was consistently stated as being conducive to learning. The quality of the simulation made them reflect on how they would act, think and change: “It was like real cases. They reached a diagnosis and called the doctor. When I assisted for the first time, I wanted to start doing something without even putting on gloves” (Egenberg et al., Citation2017). Nurses appreciated the opportunity to engage in hands-on practice outside the classroom as this is what would be expected as a floor nurse in a code situation. This high perceived relevance and realism were appreciated by healthcare staff as the training was considered more credible, beneficial, and as directly transferable to practice.

“hands-on training [was] the most valuable part of the training. Changing roles and running several scenarios is so important” (Wehbe-Janek et al., Citation2012).

Psychological Safety: Staff appreciated the freedom to speak up in order to empower them when patients are at risk of adverse events, given the legal requirement to do so (Reime et al., Citation2016). Team members also noted greater confidence in speaking up to other disciplines, lack of fear in challenging doctors’ orders (from nurses’ perspectives and embedded the importance of “communicating and speaking up when I think something should be done” (King et al., Citation2013): “If a physician starts giving the wrong drug dose, it is important that someone on the team alerts them of the error and that they in turn take this into account and do not get angry or upset” (King et al., Citation2013). Participants identified that training interprofessionally highlighted the importance of communicating effectively when working across disciplines by “communicat[ing] thoughts out loud so other team members can help identify treatment gaps” (Watters et al., Citation2015).

Ability to make mistakes: Simulation encouraged participants to accept that making mistakes in training enabled transference of positive patient safety practices (Reime et al., Citation2016; Keller et al., Citation2013; Treadwell et al., Citation2014): “I really got hit, I had even checked the name, I thought, but had not done it well enough. This experience was a real wake-up call that it is so easy to make mistakes. I have become more aware overall since then and have been more thorough in checking IDs and ensuring that double-control procedures for drug doses are followed” (Reime et al., Citation2016) and “Rather make mistakes on something that is not living than killing someone inadvertently in casualty. I would have made these mistakes and the patient would have died” (Treadwell et al., Citation2014).

Engagement with debriefing: Participants reported that engaging with the debriefing and reflective learning aspects of training helped them to gain greater insight into the roles and responsibilities of other disciplines. This was said to encourage speaking up in the future (Reime et al., Citation2016; Severson et al., Citation2014). The debrief was an essential tool to explore methods of co-operating effectively and achieve a shared common understanding of patient status (Reime et al., Citation2016): “One often assumes that everyone is thinking and understanding things the same way; however, what is inside my head is not inside the other person’s head, so you have to communicate. No one can read your thoughts” (medical student). Interprofessional team members identified team training as a key method of enabling teamwork whereby each member is trained to perform a particular task for a smooth transition from training to real-life situations (Wehbe-Janek et al., Citation2012). Through this interprofessional debriefing, teams could effectively review collaborative practices. Nurses participating in one simulated course highlighted that a key learning point was that, in times where situations got hectic, they appreciated the importance of “taking time out to recap with the team” (Watters et al., Citation2015).

Outcomes of interprofessional simulation

Key sub-themes that emerged related to outcomes of interprofessional simulation included skill level and effective leadership.

Skill Level: The simulation improved participants’ confidence, knowledge and critical thinking about healthcare processes as they were able to implement past clinical knowledge and learning during simulations to solve problems. One participant felt that simulations which were directly relevant to work-related tasks provided participants with “comprehensive knowledge and critical thinking. I know what the diagnosis, etiology, is and know how to solve the problem; I have the nursing skills to implement treatment” (Leonard et al., Citation2010). Simulation training improved staff ability in both technical and non-technical skills (i.e., communication, co-operation and co-ordination). This improved competence and confidence in performing procedures engender professional confidence: “After that training, I am courageous and confident. I can check inside up to the cervix and I am able to do bimanual compression” (Egenberg et al., Citation2017). Nurses appreciated the opportunity to build up confidence and learn more effective communication strategies in order to speak up and provide clinical input (Weller et al., Citation2012). King et al. (Citation2013) reported that the simulation training encouraged staff to prioritize and delegate tasks to improve patient safety.

Effective Leadership: Simulation can encourage a new perception of responsibility which can allow functional and appropriate leadership to flourish within interprofessional teams: “After the training, the nurse knows what to do. Now she is the pillar. She takes the position of leader” (Egenberg et al., Citation2017). The emergence of an organic leader was a catalyst to achieve simulation goals (Treadwell et al., Citation2014). Similarly, the opportunity to nominate a leader was central to achieving the goals of simulated scenarios (Watters et al., Citation2015; Severson et al., Citation2014). Staff identified that simulation reinforced the need to enact a leadership role in order to direct decisions: “It brought the focus for me on to the urgency of making the decision and facilitating the intubation … rather than the clinical skill itself” (Severson et al., Citation2014). Participants also highlighted the importance of effective followership to facilitate the clinical leader (Watters et al., Citation2015).

Interprofessional dynamics

Interprofessional Communication: Simulation was successful in increasing comfort, familiarity and confidence in communicating effectively with fellow team members. The peer support provided by the interprofessional paradigm allowed the team to work together and encouraged greater multidisciplinary input in decision-making (King et al., Citation2013). Training helped to elucidate expectations and roles of each team member alongside confidence in team members’ ability to provide quality care during this time (Koo et al., Citation2014; Wehbe-Janek et al., Citation2012; Watters et al., Citation2015): “It helps to make the situation seem more real and it … ties you in with the emotions you realize are in practice so that you don’t feel so surprised when it happens in real life” (Keller et al., Citation2013). Secondly, physicians reported greater confidence in delegating and stepping back from clinical situations in order to involve nurses in decision-making (Weller et al., Citation2012), thus enabling collective leadership.

Although team exercises were described as anxiety-inducing initially, learning how to communicate with interprofessional peers in simulated clinical scenarios significantly enhanced team members satisfaction with simulation (Leonard et al., Citation2010; Weller et al., Citation2012; Keller et al., Citation2013; King et al., Citation2013; Koo et al., Citation2014; Egenberg et al., Citation2017). Peer support encouraged greater confidence in delegating tasks, reporting clinical findings and coordinating effectively with others (King et al., Citation2013; Leonard et al., Citation2010; Reime et al., Citation2016; Van Schaik et al., Citation2011; Wehbe-Janek et al., Citation2012). The use of common structured communication tools (e.g., SBAR) was identified as key to enhancing interprofessional communication to achieve simulation goals (Keller et al., Citation2013; Koo et al., Citation2014).

Role Clarity: Simulation was successful in underlining the unique professional expertise and skillsets of healthcare professionals: the value of nurses as team members from the perspective of physicians (Treadwell et al., Citation2014) and, for nurses, the underlying reasons behind demands of physicians when requesting clinical information (Keller et al., Citation2013; King et al., Citation2013). Participants appreciated the opportunity to recognize their own strengths and weaknesses relative to their own level of experience (Leonard et al., Citation2010). Nurses reported a greater appreciation for other team members’ understanding of their responsibilities in a crisis situation after being given the opportunity to train alongside other disciplines: “Interprofessional team training can decrease or remove prejudice between the disciplines” (Kyrkjebo et al., Citation2006). Physicians reported a clearer understanding of nurses’ scope of practice: “I did not realise that she [nurse] could suture the arm … They [nurses] are very capable of taking care of a patient, even more than I and have lots of advice to give and experience to share” (Egenberg et al., Citation2017; Treadwell et al., Citation2014). In a similar vein, the multidisciplinary element of the training enhanced mutual understanding and correction of misconceptions of team members’ contribution: “After the training, it was quite evident that nurses have a very clear role to perform, and doctors, as well as attendants. Everyone has a contribution to the team work” (Egenberg et al., Citation2017).

Shared Responsibility: Team members who shared responsibility of tasks in clinical simulation gained a greater understanding of both the physical care of the patient and the decision-making process in patient care (Keller et al., Citation2013; Watters et al., Citation2015). Shared responsibility helped to “get on the same page mentally making the treatment plan obvious and decisions easier to make” (Watters et al., Citation2015); “The doctors used to undermine the nurses: ‘they know nothing’” (Egenberg et al., Citation2017). Moreover, the nurses too felt that all disciplines played a vital role during patient care. After simulation training, it was quite evident that each profession brought a unique and valuable skillset to the table. The experience of team training enhanced mutual understanding and allowed correction of misconceptions and recognition of the importance of everyone’s contribution (Egenberg et al., Citation2017; King et al., Citation2013). Participants reported that the simulation underlined a professional need to focus on the mutuality of their shared clinical purpose rather than react to their own personal feelings: “It felt good because it seemed like we were all on the same page, we all understood what the problems were regardless of what our discipline was. The first thing to do was to worry about the patient” (Keller et al., Citation2013).

Interprofessional co-operation: The experience of participating in training with other disciplines engendered a greater focus on teamwork and skill repetition (Kyrkjebo et al., Citation2006; Wehbe-Janek et al., Citation2012; Keller et al., Citation2013; Koo et al., Citation2014). Residents appreciated the opportunity to hear perspectives of other healthcare disciplines and the opportunity to practice working as a team, as it was perceived that such opportunities were rare in day-to-day practice:

“It’s the one time where we can talk through some of the systems issues, with everyone actually there, like the charge nurse, the floor nurses, the residents; talk through those things and focus on (…) the interaction between people in different roles” (Kyrkjebo et al., Citation2006).

This greater respect for the perspective of other disciplines was mirrored by Weller et al. (Citation2012), whereby physicians were more cognizant of the importance of sharing information and goals in preventing adverse events and to verbalize their thought processes so that the team developed a shared understanding of the situation. In one study, nurses identified that enhanced communication was a key outcome of simulation training as they were often unaware of the relationship between clear communication and rapid team deployment (a key learning outcome); nurses were able to gain an improved understanding about the importance of the team and not just individual skill (King et al., Citation2013; Weller et al., Citation2012).

Barriers

In discussion of barriers to effective learning from simulation, we describe findings relevant to two sub-themes: characteristics of the similar learning process and interprofessional dynamics.

Characteristics of the simulation learning process

Lack of realism: Scenarios were criticized as being unrealistic when there were very few learning points: i.e., learning limited to a central line scenario (Kyrkjebo et al., Citation2006). Realism was compromised when learning was only aimed towards one discipline, thereby limiting the value of such simulations when other team members did not see their own role in the scenarios (Kyrkjebo et al., Citation2006). Broadly relevant scenarios with multiple learning points were thus deemed important to promote realism.

Preparation for simulation: In one particular simulation exercise, only intensive nursing students could lead the session as they were the only staff with the existing competence; medical students noted their interest in participating while nursing students could not do anything without a registered nurse (Kyrkjebo et al., Citation2006). Similarly, participants reported that a greater orientation to the simulation role and process prior to simulation may have improved performance (Koo et al., Citation2014). Thus, the appropriate planning and selection of scenarios, as well as the engagement and involvement of appropriate personnel, are crucial to enable successful implementation and to enhance realism.

Interprofessional dynamics

Debriefing: Debriefing was identified as a key aspect to ensure learning transferred to real-life settings. However, some studies perceived that learning opportunities from debriefs were limited if they were multidisciplinary: “I think it is good to have it all as a group, but I (…) also think it is important that nurses and the residents get separated because I think we reflect on different aspects of it” (R07)” (Van Schaik et al., Citation2011). Concerns included doctors not wanting to offend nurses and the fear that the interprofessional context inhibits critical feedback as a result of existing structural hierarchy and the desire to maintain positive relationships with colleagues (Van Schaik et al., Citation2011).

Interprofessional hierarchy: In one study, it was reported that a mock code situation provoked anxiety, especially among doctors. This was hypothesized to be a result of existing interprofessional dynamics: residents were anxious and insecure about adopting roles in the learning process due to their lack of leadership experience and tendency to defer to more experienced staff (Van Schaik et al., Citation2011). The fidelity of simulated scenarios was reduced if they did not take into account ‘cultural competency’, i.e. a greater awareness of nurse-doctor relationships in hospitals (Keller et al., Citation2013). Participants also reported feeling intimidated and nervous when performing simulation tasks in front of peers as not everybody was as exposed to criticism as the participants in the simulation (Treadwell et al., Citation2014). Participants reported a concern that they would be unable to ensure long-term retention of studied material and that existing healthcare hierarchies would undermine the learning afforded by simulation (Keller et al., Citation2013; Treadwell et al., Citation2014).

Discussion

This study aimed to identify effective components of instructional design processes alongside specific barriers and facilitators when participating in a particular interprofessional education paradigm, namely low- and high-fidelity simulation, which may encourage transfer of skills and improved teamwork when working in interprofessional teams. This article organizes the barriers and facilitators identified by simulation participants into three primary themes: process factors related to instructional design and simulation process, interprofessional-specific factors related to teamwork and interprofessional communication and outcome factors, delineating the learning points and skills as a result of engaging in interprofessional simulation. Given the emergence of simulation as an effective method of training interprofessional collaboration and clinical knowledge (Cook et al., Citation2013; Cook, Citation2005; Cant & Cooper, 2015; Dawe, Pena, Windsor, Broeders, Cregan, Hewett, & Maddern, Citation2014) it is imperative to identify healthcare staffs’ perspectives in order to understand how implementation of simulation can be planned and delivered to enhance the learning experience and likelihood of learning transfer to real-world practice.

These data demonstrate that interprofessional dynamics were most frequently cited as a facilitator for learning transfer. This is an important insight given the evidence that simulation literature is perceived to overlook the importance of professional identity, the impact of hierarchy and power relations in educational opportunities and how this may buffer interprofessional conflict (Kitto et al., Citation2009; Lingard et al., Citation2002; Reeves et al., Citation2011). Future research must recognize the context of interprofessional work patterns and consider the local context of implementation when planning simulation training. Inclusive leadership approaches are likely to be necessary to promote and encourage engagement (Eppich & Schmutz, Citation2019).

Interprofessional dynamics were also found to facilitate effective simulation: engaging in simulation resulted in improved teamwork, greater role awareness and improved interprofessional communication. Participants perceived that the teamwork element successfully reduced professional preconceptions and silos between disciplines and was a key driver in improved interprofessional communication and clinical decision making. Failures in interprofessional communication and role clarity are a leading cause of medical error (Bognor, Citation1994; Reader et al., Citation2007; Reason, 2000; Manser et al., Citation2009; Webb et al., 1993) and are significantly related to compromised patient care, staff distress, tension and inefficiency (Lingard et al., Citation2004; Pronovost et al., Citation2003). Instructional design of simulation approaches should include a focus on improved interprofessional communication to improve patient outcomes, such as through use of structured communication tools (such as ISBAR; Marshall et al., Citation2009).

Effective debriefing, realism, psychological safety and ability to make mistakes were identified by participants as facilitators related to the process of simulation. This resonates with evidence which outlines that effective debriefing resulted in significant positive changes in teamwork and communication skills in practice after engaging in simulation (Andersen et al., Citation2018). Recently, there have been calls to embed team reflexivity into simulation-based team training (Schmutz et al., Citation2018). Integrating opportunities for the team to collectively reflect on objectives, strategies and decision-making can promote effective learning through debriefing.

Participants reported a preference for realistic clinical simulated scenarios, a finding echoed by Norman et al. (Citation2012) study which outlined how simulation transfer to real-world performance is predicted by greater task fit rather than a focus on higher fidelity. Given the greater cost of high-fidelity simulation, interprofessional simulation should be driven by training and task requirements, strong task fit, cost and learning objectives rather than fidelity as an explicit goal, especially in an interprofessional context (Norman et al., Citation2012; Salas et al., Citation1998). A focus on these aspects is more feasible for low-resource settings, and suggests that simulation can be a powerful educational tool even in the absence of high-fidelity simulation opportunities (Pitt et al., Citation2017).

Interprofessional simulation was hindered when it offered a lack of realism or did not take into account learners’ existing skills or competence. This mirrors previous evidence where participants appreciated realistic scenarios. However, participants reported that interprofessional simulation exercises could be stressful and anxiety-inducing and so could limit the capacity for learning as a factor related to the simulation process. Psychological safety was also identified as a process theme. Team members expressed increased confidence in speaking up against other professions and disciplines. A culture of psychological safety has been shown to help teams to engage in learning behaviours (Edmondson, Citation1999). However, a barrier was observed to effective debriefing when psychological safety was not present in teams and resulted in important and constructive topics not raised for discussion.

Participants in interprofessional simulation reported that tangible outcomes from interprofessional simulation were improved clinical skills and more effective leadership to manage interprofessional clinical scenarios. This underlines evidence which shows that interprofessional simulation increases leadership and management skills and technical skills among emergency healthcare staff during simulated emergency clinical scenarios (Nicksa et al., Citation2015; Murphy, Curtis & McCloughen, Citation2016). Given the link between effective leadership and high-quality provision of care (SfantouSfantou et al., Citation2017) interprofessional simulation should be encouraged as a cost-effective method to improve patient outcomes and encourage collective and shared approaches to leadership. Simulation training can help enable collective leadership in teams as individuals can dynamically lead the team, where they have the expertise and motivation to do so and as required by the task at hand.

A lack of appreciation for interprofessional dynamics may inhibit the success of interprofessional simulation. Participants identified a need to recognize the interprofessional culture of healthcare teams and how this may affect learning in dynamic healthcare teams, especially when debriefing (Sharma et al., Citation2011). Secondly, interprofessional simulation approaches need to consider all participants’ existing skills and experience. If a participant is unable to fully engage in the education piece, this will limit their capacity for learning transfer (Kyrkjebo et al., Citation2006). Simulation can serve to highlight the relative value and contribution of various disciplines, likely promoting respect and shared understanding of roles among team members.

One interesting finding from our synthesis was a lack of evidence showing organizational support or lack thereof as a significant barrier or facilitator to interprofessional simulation. This is surprising given the established relationship between perceived quality of care and perceived support from unit-level managers (Gunnarsdóttir et al., Citation2009) alongside reports that supportive management and leadership behaviour is essential to create a positive working atmosphere and prevent staff burnout (Aiken et al., Citation2001; Laschinger & Finegan, Citation2005). Further qualitative evidence is needed to understand healthcare professionals’ perception of the role of organizational support.

Limitations

This review of the qualitative evidence of the perceptions of healthcare staff engaging in interprofessional simulation is key to ensure that objectives of learning are in line with the needs and objectives of healthcare staff. However, there are limitations to the review. Firstly, this review did not take into account educators’ perceptions of interprofessional simulation approaches. Secondly, the barriers and facilitators in this review did not differentiate between type of simulator. Future research may benefit from a deeper understanding of the distinctive barriers and facilitators pertaining to low- and high-fidelity simulators. In addition, this review purposively only investigated qualitative evidence. A common criticism of qualitative evidence is the higher proclivity of researcher bias and generalization (Britten & Fisher, Citation1993). Despite this, we observed common patterns across studies which lends support to these findings and their potential for generalizability.

Conclusion

Interprofessional simulation approaches have been shown as an effective method of simulating clinical situations with multidisciplinary healthcare teams by providing a safe environment to practice clinical skills and teamwork. However, in order to ensure that participants are actively engaging in education, educators must ensure that interprofessional simulation approaches can effectively mirror realistic clinical scenarios, embrace interprofessional integration and teamwork and provide a psychologically safe learning environment. Facilitators were reported more commonly than barriers (which may be indicative of publication bias of positive results) and facilitators were most common when addressing interprofessional dynamics. Appreciating the context in which healthcare staff work is essential to ensure that objectives of implementing simulation are aligned with the needs of learners and engaged in a way that cognitively best reflects the everyday practice (Schmidt et al., Citation2013).

Declaration of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by the Irish Health Research Board, grant reference number RL-2015-1588. This research is also supported by the Health Service Executive.

Data availability statement

All papers/data included in this review are available online.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fergal Connolly

Mr Fergal Connolly worked as a Research Assistant with the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Systems, University College Dublin, Ireland. Fergal holds an Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Maynooth University, Ireland and a Masters of Science in Foundations of Health Psychology and Clinical Psychology from Goldsmiths, University of London. He has experience in working with multidisciplinary teams in projects in health systems and health psychology research.

Aoife De Brún

Dr. Aoife De Brún is Assistant Professor/Ad Astra Fellow at the UCD Centre for Research, Education and Innovation in Health Systems (UCD IRIS) at the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Systems in University College Dublin, Ireland. She is a registered Chartered Psychologist and conducts inter-disciplinary health systems and healthcare services research.

Eilish McAuliffe

Professor Eilish McAuliffe is Professor of Health Systems at University College Dublin, Ireland. She holds a B.Sc. Psychology from University College Dublin, an M.Sc. Clinical Psychology from University of London, an MBA from Strathclyde University and a PhD from Trinity College Dublin. Prof McAuliffe is the Director of the UCD Centre for Interdisciplinary Research Education and Innovation in Health Systems (UCD IRIS Centre). The work of the IRIS Centre is characterised by systems thinking, interdisciplinary and intersectoral working, patient and public involvement and robust evidence synthesis, informing the collaborative design of health systems interventions and professional development programmes, as well as contributing to methodological innovation and strong networks and partnerships.

References

- Aggarwal, R., Mytton, O. T., Derbrew, M., Hananel, D., Heydenburg, M., Issenberg, B., Ziv, A., Mancini, M. E., Morimoto, T., Soper, N., Ziv, A., & Reznick, R. (2010). Training and simulation for patient safety. BMJ Quality & Safety, 19(Suppl 2), i34–i43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.038562

- Aiken, L. H., Clarke, S. P., Sloane, D. M., Sochalski, J. A., Busse, R., Clarke, H., Shamian, J., Hunt, J., Rafferty, A. M., & Shamian, J. (2001). Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs, 20(3), 43–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43

- Andersen, P., Coverdale, S., Kelly, M., & Forster, S. (2018). Interprofessional Simulation: Developing Teamwork Using a Two-Tiered Debriefing Approach. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 20, 15–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2018.04.003

- Anderson, M. (2007) Effect of integrated high-fidelity simulation on knowledge, perceived self-efficacy and satisfaction of nurse practitioner students in newborn assessment. PhD thesis, Texas Woman’s University

- Barr, H. (2001). Interprofessional education: Today, yesterday, and tomorrow. London, UK: Westminster University, Learning and Teaching Support Network Centre of Health Sciences and Practice. UK Higher Education Academy, Health Sciences and Practice Network.

- Beaubien, J. M., & Baker, D. P. (2004). The use of simulation for training teamwork skills in health care: How low can you go? BMJ Quality & Safety, 13(suppl 1), i51–i56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.009845

- Boet, S., Bould, M. D., Sharma, B., Revees, S., Naik, V. N., Triby, E., & Grantcharov, T. (2013). Within-team debriefing versus instructor-led debriefing for simulation-based education: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery, 258(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31829659e4

- Bognor, M. (1994). Human error in medicine (1st edn ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Association Inc.

- Britten, N., & Fisher, B. (1993). Qualitative research and general practice. The British Journal of General Practice, 43(372), 270. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1372451/

- Cant, R. P., & Cooper, S. J. (2010). Simulation‐based learning in nurse education: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05240.x

- Capella, J., Smith, S., Philp, A., Putnam, T., Gilbert, C., Fry, W., Ranson, S., Henderson, K., Baker, D., Ranson, S., ReMine, S., & Harvey, E. (2010). Teamwork training improves the clinical care of trauma patients. Journal of Surgical Education, 67(6), 439–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.06.006

- Cook, D. A. (2005). The research we still are not doing: An agenda for the study of computer-based learning. Academic Medicine, 80(6), 541–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200506000-00005

- Cook, D. A., Hamstra, S. J., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Comparative effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation-based education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Teacher, 35(1), e867–e898. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.714886

- Cumin, D., Boyd, M. J., Webster, C. S., & Weller, J. M. (2013). A systematic review of simulation for multidisciplinary team training in operating rooms. Simulation in Healthcare, 8(3), 171–179.

- D’Eon, M. (2005). A blueprint for interprofessional learning. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 49–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820512331350227

- Dawe, S. R., Pena, G. N., Windsor, J. A., Broeders, J. A. J. L., Cregan, P. C., Hewett, P. J., & Maddern, G. J. (2014). Systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation‐based training. British Journal of Surgery, 101(9), 1063–1076.

- Donaldson, L. (2009). Safer medical practice: Machines, manikins and polo mints. 150 years of the annual report of the Chief Medical Officer: On the state of public health 2008. Department of Health, Crown Copyright.

- Donaldson, M. S., Corrigan, J. M., & Kohn, L. T. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system (Vol. 6). National Academies Press.

- Dunkin, B., Adrales, G. L., Apelgren, K., & Mellinger, J. D. (2007). Surgical simulation: A current review. Surgical Endoscopy, 21(3), 357–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-006-9072-0

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative science quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

- Egenberg, S., Karlsen, B., Massay, D., Kimaro, H., & Bru, L. E. (2017). “No patient should die of PPH just for the lack of training!” Experiences from multi-professional simulation training on postpartum hemorrhage in northern Tanzania: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0957-5

- Eppich, W., Howard, V., Vozenilek, J., & Curran, I. (2011). Simulation-based team training in healthcare. Simulation in Healthcare, 6(7), S14–S19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e318229f550

- Eppich, W. J., & Schmutz, J. B. (2019). From ‘them’ to ‘us’: Bridging group boundaries through team inclusiveness. Medical Education, 53(8), 756–758. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13918

- Fowler-Durham, C. F., & Alden, K. R. (2008). Enhancing patient safety in nursing education through patient simulation.

- Friedman, C. P. (1994). The research we should be doing. Academic Medicine, 69(6), 455–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199406000-00005

- Fukuchi, S. G., Offutt, L. A., Sacks, J., & Mann, B. D. (2000). Teaching a multidisciplinary approach to cancer treatment during surgical clerkship via an interactive board game. The American Journal of Surgery, 179(4), 337–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00339-1

- Gardner, R., & Raemer, D. B. (2008). Simulation in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America, 35(1), 97–127.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Greenhalgh, T., Thorne, S., & Malterud, K. (2018). Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 48(6), e12931. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12931

- Griffiths, Y., & Ursick, K. (2004). Using active learning to shift the habits of learning in health care education. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 2(2), 5. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1043&context=ijahsp/

- Gunnarsdóttir, S., Clarke, S. P., Rafferty, A. M., & Nutbeam, D. (2009). Front-line management, staffing and nurse–doctor relationships as predictors of nurse and patient outcomes. A survey of Icelandic hospital nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(7), 920–927. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.11.007

- Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. (2015). The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PloS One, 10(9), e0138237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

- Hogg, G., Pirie, E. S., & Ker, J. (2006). The use of simulated learning to promote safe blood transfusion practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 6(4), 214–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2006.01.004

- Hovancsek, M. T. (2007). Using simulation in nursing education. In P. R. Jeffries (Ed.), Simulation in Nursing Education: From Conceptualization to Evaluation, (1–9). New York, NY: National League for Nursing

- Issenberg, S. B., McGaghie, W. C., Petrusa, E. R., Gordon, D. L., & Scalese, R. J. (2005). Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Medical Teacher, 27(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500046924

- Issenberg, S. B., & Scalese, R. J. (2014). Five Tips for a Successful Submission on Simulation-Based Medical Education.

- Kardong-Edgren, S. E., Starkweather, A. R., & Ward, L. D. (2008). The integration of simulation into a clinical foundations of nursing course: Student and faculty perspectives. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 5(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.1603

- Keller, K. B., Eggenberger, T. L., Belkowitz, J., Sarsekeyeva, M., & Zito, A. R. (2013). Implementing successful interprofessional communication opportunities in health care education: a qualitative analysis. International journal of medical education, 4, 253.

- Kelly, S. (1995). Research in brief. Trivia-psychotica: The development and evaluation of an educational game for the revision of psychiatric disorders in a nurse training programme. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2(6), 366–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.1995.tb00108.x

- Kenaszchuk, C., MacMillan, K., van Soeren, M., & Reeves, S. (2011). Interprofessional simulated learning: Short-term associations between simulation and interprofessional collaboration. BMC Medicine, 9(1), 29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-29

- King, A. E. A., Conrad, M., & Ahmed, R. A. (2013). Improving collaboration among medical, nursing and respiratory therapy students through interprofessional simulation. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(3), 269–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.730076

- Kinney, S., & Henderson, D. (2008). Comparison of low fidelity simulation learning strategy with traditional lecture. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 4(2), e15–e18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2008.06.005

- Kitto, S. C., Gruen, R. L., & Smith, J. A. (2009). Imagining a continuing interprofessional education program (CIPE) within surgical training. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 29(3), 185–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.20034

- Kneebone, R., Kidd, J., Nestel, D., Asvall, S., Paraskeva, P., & Darzi, A. (2002). An innovative model for teaching and learning clinical procedures. Medical Education, 36(7), 628–634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01261.x

- Kneebone, R., Nestel, D., Wetzel, C., Black, S., Jacklin, R., Aggarwal, R., Yadollahi, F., Wolfe, J., Vincent, C., & Darzi, A. (2006). The human face of simulation: Patient-focused simulation training. Academic Medicine, 81(10), 919–924. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000238323.73623.c2

- Koo L, Layson-Wolf C, Brandt N, Hammersla M, Idzik S, Rocafort PT, Tran D, Wilkerson RG, Windemuth B. 2014. Qualitative evaluation of a standardized patient clinical simulation for nurse practitioner and pharmacy students. Nurse Education in Practice. Nov 1;14(6):740–746.

- Kyrkjebø, J. M., Brattebø, G., & Smith-Strøm, H. (2006). Improving patient safety by using interprofessional simulation training in health professional education. Journal of interprofessional care, 20(5), 507–516.

- Laschinger, H. K. S., & Finegan, J. (2005). Using empowerment to build trust and respect in the workplace: A strategy for addressing the nursing shortage. Nursing Economics, 23(1), 6. https://search.proquest.com/openview/d0f331cadea9d1c9b10a73bb826d25fe/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=30765&casa_token=rWPSAeMusHIAAAAA:v0UU9L_chKrmlzrk6N55jfnt41C_QnPYX0Z6knaCDSiwCsWzJd_TLTac2ALOH5b23fU3xdMs

- Leighton, K., & Scholl, K. (2009). Simulated codes: Understanding the response of undergraduate nursing students. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 5(5), e187–e194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2009.05.058

- Leonard, B., Shuhaibar, E. L., & Chen, R. (2010). Nursing student perceptions of intraprofessional team education using high-fidelity simulation. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(11), 628–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20100730-06

- Lingard, L., Espin, S., Whyte, S., Regehr, G., Baker, G. R., Reznick, R., … Grober, E. (2004). Communication failures in the operating room: An observational classification of recurrent types and effects. BMJ Quality & Safety, 13(5), 330–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.008425

- Lingard, L., Reznick, R., Espin, S., Regehr, G., & DeVito, I. (2002). Team communications in the operating room: Talk patterns, sites of tension, and implications for novices. Academic Medicine, 77(3), 232–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200203000-00013

- MacKinnon, R. J. (2011). Editorial: The rise of the collaborative inter-professional simulation education network? Infant, 7(1), 6–8. https://www.infantjournal.co.uk/pdf/inf_037_mul.pdf

- Manser, T., Harrison, T. K., Gaba, D. M., & Howard, S. K. (2009). Coordination patterns related to high clinical performance in a simulated anesthetic crisis. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 108(5), 1606–1615. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e3181981d36

- Maran, N. J., & Glavin, R. J. (2003). Low‐to high‐fidelity simulation–a continuum of medical education? Medical Education, 37(Suppl.1), 22–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.37.s1.9.x

- Marshall, S., Harrison, J., & Flanagan, B. (2009). The teaching of a structured tool improves the clarity and content of interprofessional clinical communication. BMJ Quality & Safety, 18(2), 137–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.025247

- Merién, A. E. R., Van de Ven, J., Mol, B. W., Houterman, S., & Oei, S. G. (2010). Multidisciplinary team training in a simulation setting for acute obstetric emergencies: A systematic review. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 115(5), 1021–1031. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d9f4cd

- Murphy, M., Curtis, K., & McCloughen, A. (2016). What is the impact of multidisciplinary team simulation training on team performance and efficiency of patient care? An integrative review. Australasian emergency nursing journal, 19(1), 44–53.

- Nackman, G. B., Bermann, M., & Hammond, J. (2003). Effective use of human simulators in surgical education1. Journal of Surgical Research, 115(2), 214–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4804(03)00359-7

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2016). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage.

- Nicksa, G. A., Anderson, C., Fidler, R., & Stewart, L. (2015). Innovative approach using interprofessional simulation to educate surgical residents in technical and nontechnical skills in high-risk clinical scenarios. JAMA Surgery, 150(3), 201–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2235

- Norman, G., Dore, K., & Grierson, L. (2012). The minimal relationship between simulation fidelity and transfer of learning. Medical Education, 46(7), 636–647. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04243.x

- Pitt, M. B., Eppich, W. J., Shane, M. L., & Butteris, S. M. (2017). Using simulation in global health: Considerations for design and implementation. Simulation in Healthcare, 12(3), 177–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000209

- Pronovost, P., Berenholtz, S., Dorman, T., Lipsett, P. A., Simmonds, T., & Haraden, C. (2003). Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. Journal of Critical Care, 18(2), 71–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1053/jcrc.2003.50008

- Rabøl, L. I., Østergaard, D., & Mogensen, T. (2010). Outcomes of classroom-based team training interventions for multiprofessional hospital staff. A systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care, 19(6), e27–e27. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.037184

- Reader, T. W., Flin, R., & Cuthbertson, B. H. (2007). Communication skills and error in the intensive care unit. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 13(6), 732–736. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f1bb0e

- Reese, C. E., Jeffries, P. R., & Engum, S. A. (2010). Using simulations to develop nursing and medical student collaboration. Nurse Education Perspectives, 31(1), 33–37. https://journals.lww.com/neponline/Abstract/2010/01000/LEARNING_TOGETHER_Using_Simulations_to_Develop.9.aspx

- Reeves, S., Lewin, S., Espin, S., & Zwarenstein, M. (2011). Interprofessional teamwork for health and social care (Vol. 8). John Wiley & Sons.

- Reeves, S., Perrier, L., Goldman, J., Freeth, D., & Zwarenstein, M. (2013). Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 3, 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3

- Reime, M. H., Johnsgaard, T., Kvam, F. I., Aarflot, M., Breivik, M., Engeberg, J. M., & Brattebø, G. (2016). Simulated settings; powerful arenas for learning patient safety practices and facilitating transference to clinical practice. A mixed method study. Nurse Education in Practice, 21, 75–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.10.003

- Rosen, M. A., Weaver, S. J., Lazzara, E. H., Salas, E., Wu, T., Silvestri, S., Schiebel, N., Almeida, S., & King, H. B. (2010). Tools for evaluating team performance in simulation-based training. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock, 3(4), 353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.70746

- Salas, E., Bowers, C. A., & Rhodenizer, L. (1998). It is not how much you have but how you use it: Toward a rational use of simulation to support aviation training. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 8(3), 197–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327108ijap0803_2

- Schmidt, E., Goldhaber-Fiebert, S. N., Ho, L. A., & McDonald, K. M. Simulation exercises as a patient safety strategy: A systematic review. (2013). Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(5_Part_2), 426–432. 5_Part_2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00010

- Schmutz, J. B., Kolbe, M., & Eppich, W. J. (2018). Twelve tips for integrating team reflexivity into your simulation-based team training. Medical Teacher, 40(7), 721–727. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1464135

- Severson, M. A., Maxson, P. M., Wrobleski, D. S., & Dozois, E. J. (2014). Simulation-based team training and debriefing to enhance nursing and physician collaboration. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 45(7), 297–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20140620-03

- Sfantou, D., Laliotis, A., Patelarou, A., Sifaki-Pistolla, D., Matalliotakis, M., & Patelarou, E. 2017. Importance of leadership style towards quality of care measures in healthcare settings: A systematic review. Healthcare. 5(4), 73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5040073

- Sharma, S., Boet, S., Kitto, S., & Reeves, S. (2011). Interprofessional simulated learning: The need for ‘sociological fidelity’.

- Stewart, M., Kennedy, N., & Cuene‐Grandidier, H. (2010). Undergraduate interprofessional education using high‐fidelity paediatric simulation. The Clinical Teacher, 7(2), 90–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00351.x

- Sturm, L. P., Windsor, J. A., Cosman, P. H., Cregan, P., Hewett, P. J., & Maddern, G. J. (2008). A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training. Annals of Surgery, 248(2), 166–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176bf24

- Tofil, N. M., Morris, J. L., Peterson, D. T., Watts, P., Epps, C., Harrington, K. F., Leon, K., Pierce, C., & White, M. L. (2014). Interprofessional simulation training improves knowledge and teamwork in nursing and medical students during internal medicine clerkship. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 9(3), 189–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2126

- Treadwell, I., Van Rooyen, M., Havenga, H., & Theron, M. (2014). The effect of an interprofessional clinical simulation on medical students. African Journal of Health Professions Education, 6(1), 3–5. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajhpe/article/view/104893

- Van Schaik, S. M., Plant, J., Diane, S., Tsang, L., & O’sullivan, P. (2011). Interprofessional team training in pediatric resuscitation: A low-cost, in situ simulation program that enhances self-efficacy among participants. Clinical Pediatrics, 50(9), 807–815. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922811405518

- Visser, C. L., Ket, J. C., Croiset, G., & Kusurkar, R. A. (2017). Perceptions of residents, medical and nursing students about Interprofessional education: A systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative literature. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0909-0

- Ward, M., McAuliffe, E., Shé, É. N., Duffy, A., Geary, U., Cunningham, U., Holland, C., McDonald, N., Egan, K., & Korpos, C. (2017). Imbuing medical professionalism in relation to safety: A study protocol for a mixed-methods intervention focused on trialling an embedded learning approach that centres on the use of a custom designed board game. BMJ Open, 7(7), e014122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014122

- Watters, C., Reedy, G., Ross, A., Morgan, N. J., Handslip, R., & Jaye, P. (2015). Does interprofessional simulation increase self-efficacy: a comparative study. BMJ open, 5(1).

- Wehbe-Janek, H., Lenzmeier, C. R., Ogden, P. E., Lambden, M. P., Sanford, P., Herrick, J., Song, J., Pliego, J. F., & Colbert, C. Y. (2012). Nurses’ perceptions of simulation-based interprofessional training program for rapid response and code blue events. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 27(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182303c95

- Weller, J., Frengley, R., Torrie, J., Webster, C. S., Tomlinson, S., Henderson, K., Tomlinson, S., Henderson, K., & Henderson, K. (2012). Change in attitudes and performance of critical care teams after a multi-disciplinary simulation-based intervention. International Journal of Medical Education, 3, 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5019.6b01

- Yardley, S., & Dornan, T. (2012). Kirkpatrick’s levels and education ‘evidence’. Medical Education, 46(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04076.x

- Zendejas, B., Cook, D. A., Bingener, J., Huebner, M., Dunn, W. F., Sarr, M. G., & Farley, D. R. (2011). Simulation-based mastery learning improves patient outcomes in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery, 254(3), 502–511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c6994

- Zhang, C., Thompson, S., & Miller, C. (2011). A review of simulation-based interprofessional education. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 7(4), e117–e126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2010.02.008