ABSTRACT

The complexity and challenges of higher education (HE) in recent times have been widely discussed in HE literature, as have concomitant demands on university teachers and their professional learning needs. Much attention has been paid to new academics in these conversations, but less so to international PhD and post-doctoral researchers, who are often asked to teach, yet can be precluded from attending foundational pedagogical courses. This paper discusses an interpretive-hermeneutic study based on a pedagogical course developed for new academics in this very situation. Our discussion focuses on professional growth experienced by the course participants in terms of pedagogical understanding and self-confidence, and what enabled that growth from the participants’ perspectives. On the basis of analysis of interviews, questionnaires and qualitative course evaluations, we consider the value of such purpose-built courses and offer insights into what may need to be considered by course developers to ensure that their impact is optimal.

Introduction

Higher education (HE) pedagogy courses have become increasingly commonplace in universities in recent times, with many courses now being a mandatory part of an academic’s career. These courses are generally designed to promote a deeper understanding of theoretical issues and the rationale behind teaching approaches for better student learning outcomes, sometimes in combination with particular teaching strategies and techniques. These courses seem especially important with the increasing demands being placed on university teachers in their everyday work due to accountability pressures, increasing student diversity, intensification of academic work, funding pressures, and demands of industry and other stakeholders.

Many courses are aimed at tenured academic staff or staff on long-term contracts and have been shown to have an impact especially for academics with minimal teaching experience. However, it seems to us that there is a somewhat ‘forgotten’ group when it comes to pedagogical courses and other professional learning opportunities related to teaching: PhD candidates and post-doctoral (post-doc) researchers. These academics are often required to take on minor teaching responsibilities despite little or no formal preparation for teaching or prior teaching experience. They are also sometimes excluded from foundational teaching courses due to ineligibility or the time commitments required for course completion. This puts them in a particularly stressful position in terms of learning to teach with little support. International PhD candidates and post-doc researchers can have the added challenge of having to negotiate new cultural and educational norms and language challenges (Robinson-Pant Citation2009) while dealing with the difficulties of transitioning to a new country without their familiar social networks to support them.

This paper focuses on a non-mandatory pedagogical course designed at our university with the professional learning needs of international PhD candidates and post-doc researchers in mind. The university, located in Sweden, attracts a very high share of international PhD candidates.Footnote1 Our discussion is based on findings of a small-scale inquiry which explored the experiences of course participants in this course. In particular, the investigation focussed on whether and how participants experienced professional growth (Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002), the nature of this growth, and what enabled it during the course. The inquiry involved six course participants from various disciplines and countries other than Sweden who became involved in the study upon completion of the course. Motivations for the study were, on the one hand, a desire to reflect on the impact and efficacy of the course for review and redevelopment purposes, and on the other hand, a more general interest in better understanding the processes that course participants go through and what makes individual professional growth possible in or during pedagogical courses.

The inquiry suggested that the participants experienced growth during the course in many respects, but particularly in terms of a more holistic and nuanced understanding of teaching and learning in HE, and along with that, changed self-confidence. Analysis also highlighted specific aspects of the course – such as the dialogic and reflective nature of the activities, and opportunities for collegial learning and exploring relevant pedagogical concepts and practices – that, in combination with participants’ motivations and backgrounds, contributed to, or mediated, this growth. This paper aims to contribute to ongoing conversations and debate about nurturing professional growth among new academics by elaborating on these findings.

The paper is structured as follows. First, an overview of relevant research into professional growth associated with pedagogical courses is provided. This is followed by a description of the course in focus. The next section outlines the research approach and strategies used to generate and analyse empirical material. In the second half of the paper, discussion centres on the main findings related to (a) enhanced pedagogical understanding, (b) changed self-confidence, and (c) what enabled (a) and (b). The significance and implications of our findings in terms of nurturing professional growth more broadly amongst new academics are considered. The paper concludes with some general remarks about the role of staff development programmes and/or pedagogical courses in this nurturing process.

Pedagogical courses, pedagogical understanding, and self-confidence

The value of pedagogical courses for university teachers has been recognised by several writers (e.g. Ho Citation2000; Kligyte Citation2011), not least for their role in creating conditions in which new and expanded perspectives on teaching and learning can develop. Studies related to such courses have varied in terms of their focus and starting points. Many investigations have attended, for instance, to conceptions of teaching and learning (e.g. Åkerlind Citation2008), highlighting that how teachers think about and understand teaching and learning (i.e. their pedagogical understandings) is directly related to their teaching practices (Ho Citation2000). Some have explored changes in teacher ‘behaviour’, or deepened/expanded pedagogical knowledge and whether and/or how that knowledge has manifested in teaching practice (e.g. Norton et al. Citation2010; Kligyte Citation2011; Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2011; Derting et al. Citation2016). Some researchers have focussed quite specifically on teacher’s shifts in orientations from what is regarded as ‘teacher-centred’ to what is considered ‘student-centred’ (e.g. Gibbs and Coffey Citation2004; Derting et al. Citation2016). More recent studies have examined constraints (structural; pertaining to the academic context) experienced by new academics when endeavouring to act on insights and agency derived from pedagogical courses (e.g. Behari-Leak Citation2017).

A great deal of the existing research points to the importance of participants in such programmes developing a greater appreciation of the complexities of teaching and learning in HE (Åkerlind Citation2005; Kligyte Citation2011). Their new perspectives on an intellectual level reportedly serve as a culturally-based filter which helps them navigate in teaching and learning contexts (Kligyte Citation2011). They provide a basis for reflections on teaching experiences.

The extent to which teachers act on their new perspectives and pedagogical understandings, some argue (e.g. Åkerlind Citation2003; Sadler Citation2013), is partly a matter of self-confidence and, relatedly, a willingness on the part of those teachers to take risks (e.g. Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2011) connected to experimenting with and changing teaching practice. Sadler (Citation2013), in his investigation of self-confidence in learning to teach in HE, stressed a feeling of uneasiness associated with the risks of acting on new ideas. Conversely, positive self-confidence was linked to a readiness to put newly encountered ideas and strategies (such as interactive teaching and learning strategies) into practice. Such trying out, or risk taking, is important for pedagogical development in that it leads to new experiences upon which to reflect (Kligyte Citation2011).

According to Sadler’s (Citation2013) case study, positive self-confidence usually originates from the perception of having good-enough content knowledge for the unit to be taught and familiarity with practical arrangements and the teaching situation. Self-confidence grows, he argues, with increasing experiences of (positive) interactions with students, and reaching a point of no longer feeling ‘a need to know it all’ (163). On a different note, Kligyte’s study (Citation2011) links feelings of increased confidence with an increased sense of agency derived from an awareness of being able ‘to change and shape one’s teaching practice’ (210). Interestingly for us, because of the experiences of some of our course participants, not all studies describe increases in self-confidence associated with increased pedagogical understanding. Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne (Citation2011), for example, cite instances of some teachers feeling less self-confident after pedagogical courses due to a realisation that their skills are not as good as they thought they were prior to courses.

These studies suggest that self-confidence related to teaching practice is not a stable personal characteristic.Footnote2 Rather, it is subject to change and sensitive to context (Sadler Citation2013; see also Bandura Citation1986). The studies also highlight that pedagogical courses can affect academics' self-confidence, for example, by raising academics’ awareness of what university teaching entails. However, Sadler (Citation2013) comments that pedagogical courses need to be proactive regarding self-confidence: they need to be deliberately ‘sensitive and supportive of confidence’ (Citation2013, 165). He argues further that there is a role for course managers within academic departments to provide a stable teaching environment for beginning university teachers where they can feel secure with their content knowledge and have opportunities to become familiar with the course unit at stake.

Together existing studies provide important insights into the role of pedagogical courses in nurturing the professional growth of new academics. However, it seems to us that few studies have gone far enough in terms of unpacking the variety of influencing factors for growth, especially regarding self-confidence and pedagogical understanding, or focussed particularly on the group of new academics we are concerned with here. Our paper aims to build on existing studies and contribute to the discussion about learning to teach in HE in this respect.

Course description

The pedagogical course at the centre of this inquiry introduces participants to teaching and learning in a university setting with a view to helping them to prepare for their future teaching duties. Its main aims are to foster a nuanced understanding of teaching and learning in a Swedish HE context; to encourage participants to be open, reflective, and self-aware practitioners; to support transition from other countries, other contexts, and other disciplines into HE pedagogical practice; and to provide opportunities to encounter and critically explore theoretical resources that can help participants understand their roles and the kinds of pedagogical challenges their future work as university teachers might entail.

The course was purpose-designed for new university staff not in a position to enrol in the university’s existing foundational university teaching course because they were undertaking doctoral studies and thus could not meet the commitment/attendance demands of that course, and/or were not yet proficient in Swedish, the language of instruction for that course.Footnote3 Course participants so far have mainly come from countries other than Sweden, and primarily to undertake PhD research. They have also represented a variety of disciplinary fields. Most have had very little prior teaching experience, either in universities or in other contexts. Some have been assigned minor teaching duties whilst studying (e.g. tutoring a Masters thesis or teaching classes at Masters or Bachelor level). Enrolments in the course have varied from 4 to 12 per group.

The course is framed by assumptions about the importance of reflection, collegial learning, and active inquiry into relevant educational knowledge bases. At the time of this inquiry, the course consisted of 5 days of face-to-face sessions spread evenly over one academic term and interspersed with various reading and assessment-related tasks. The face-to-face sessions were made up of, for example, lectures (by multiple academics), hands-on activities using digital tools, and a range of dialogic activities including case analyses, discussions based on course readings, and reflective discussions about the participants’ practices, experiences, and pre-existing beliefs/values about teaching and learning. Assessment tasks included, among other things, an oral report on a classroom observation of, and follow-up interview with, an experienced teaching colleague (seminar presentation). Through the course activities, the participants collaboratively and individually considered a range of pedagogical issues and challenges and were exposed to, investigated/reflected on, and had the opportunity to experiment with, a variety of pedagogical approaches and strategies. Further details about the course are provided in the context of the findings discussion below.

The inquiry

The inquiry was conducted as a case study (Yin Citation2006) based on the perspectives and experiences of six participants in the course. The central aim was to investigate how the participants understood their development and learning processes during course participation, and how this might relate to their practice and development as teachers in the future. The necessity of a research approach looking at the process of learning during a staff development course has been stressed by Kligyte (Citation2011) on the basis that such methodological perspectives will deepen our understanding ‘if we are to consider academics’ development in their roles more holistically, and particularly, if we are to move beyond narrowly conceived ‘before and after’-type impact evaluations’ (212).

The investigation was informed by an interpretive-hermeneutic tradition (Muganga Citation2015), and guided by two main research questions:

Did the participants experience professional growth, and if so, what did that entail?

What enabled (or made possible) such growth for the participants in the course and how?

The course participants – Karl, Lin, Kim, Jacques, Jon, and AryaFootnote4 (3 males and 3 females) – willingly agreed to participate in the inquiry upon an invitation by the course directors after course completion. These particular course participants were chosen on the basis of convenience: they were based at the university post-course and thus available for interview. Each was fully informed about the nature of the study and provided consent on the understanding that he/she could withdraw from the study at any time.

The participants were either doctoral candidates or post-doctoral researchers from a mixture of African, Asian, South American, Middle Eastern, and European countries. They also represented a range of subject fields within textile engineering, chemistry, library and information science, and textile management and had specialised knowledge in their respective fields. In terms of teaching experience, one had some lecturing experience, another had school teaching experience. The others were mostly fresh teachers with limited teaching experience (e.g. tutoring in Masters classes) or, in one case, with no teaching experience. The participants were from two cohorts across two consecutive years.

All participants took part in an interview which was audio-recorded and transcribed. These interviews were the primary source of empirical material in the inquiry. After the interview transcripts were analysed, the questionnaires and course evaluations were also systematically analysed to complement the findings from the interview analysis. Specific processes for conducting and analysing the interviews, course evaluations, and questionnaires are explained below.Footnote5

Interviews

Individual, semi-structured face-to-face interviews of about 0.5–1 h duration were conducted several weeks after course completion. The interview prompts ranged widely over educational issues (e.g. conceptions of teaching, links between teaching and learning, prior teaching/learning experience, the nature of good teaching, recent professional growth and growth as a course outcome), while simultaneously giving the participants space for individual thoughts and ideas within the general framework of HE. The interviewees were also given the opportunity to explain their responses to the questionnaire outlined below.

Analysis of the interview transcripts involved an iterative process best described as thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The first stage involved an initial reading of transcripts by two of the authors whereby general themes were identified. Next, a list of codes and categories combining these preliminary themes with themes that emerged from the literature reviewed for the research was created. Using the list of codes and categories, all transcripts were systematically coded by two of the authors independently, with a review involving all three authors at a midway point to discuss consistency in analysis. During this phase of analysis, the list of codes was modified and some re-categorisation of themes occurred to accommodate the emergence of additional themes. At the completion of the coding process, detailed narrative summaries were generated for each transcript in order to capture a sense of the ‘whole’, a sense that was, in some ways, diluted in the dissection of the texts via our coding.

Course evaluations

The evaluations comprised questions developed in cooperation with participants as a learning activity in the course. Questions included, for example, ‘What was the most important thing you learned about teaching and learning in HE from taking this course?’ What was the most important thing you learned about yourself while taking this course?’ The answers to the course evaluation questions were coded according to categories that emerged in the analysis of interview transcripts. General categories included expanded awareness and changed understanding (e.g. of theoretical matters, of the complexities of teaching, and of instrumental matters such as teaching resources and strategies) and shifts in beliefs (about the nature of knowledge formation, the nature of learning, and beliefs about oneself).

Questionnaires

A questionnaire adapted from Norton et al. (Citation2005) was used in the course as a pedagogical resource to stimulate course participant reflection on assumptions about teaching and learning in HE at both the beginning (pre-course) and the end of our course (post-course).Footnote6 The items targeted two main areas of how participants view teaching and learning in HE. One related to beliefs about oneself (i.e. the confidence and skills the participants estimate they have in their role as a teacher/facilitator). The other dealt with different approaches to teaching and learning (e.g. student v. teacher-centred approaches). Analysis of the questionnaires involved comparison of pre-course and post-course responses. Due to the small number of participants, analysis mostly focused on the results that showed significant variations among individual course participants. The trends that were discernible from the analyses were captured in graph formats.

Findings and discussion

Our analyses of the interviews, questionnaires, and course evaluations revealed that what the participants experienced as professional growth and/or learning was certainly not straightforward. Rather, it involved a combination of processes that differed in nuanced ways from person to person. Also, there were many and varied contributing factors. Four key, interrelated areas of professional growth emerged as significant:

a more holistic and nuanced understanding of teaching and learning in HE;

changed self-confidence;

shifts in attitudes towards, and beliefs about, teaching and learning and the teaching role; and

shifts in orientation to teaching (towards a student-centred orientation and a focus on learning, or becoming more firmly student-centred).

In the paragraphs that follow, we have chosen to focus on the first two since they have received less attention in HE literature. We draw mostly on excerpts from the interviews and course evaluations due to our chosen focus.

A more holistic and nuanced understanding of teaching and learning in HE

In the interviews, most of the participants alluded to having a more holistic and nuanced understanding of what teaching and learning in HE entails. This appeared to manifest in three main (overlapping) ways. Firstly, some of the participants referred to the learning of new theoretical ideas and particular concepts and a language with which to make sense of, and articulate ideas about, teaching and learning. This apparently meant coming to understand how various aspects of teaching and learning relate to each other. Karl’s interview comment highlights this well:

When you have only your experience, you try to make sense of things, categorise. I think this course was really helping in the sense that a lot of things that I have in my mind, here and there, really fragmented thoughts, I kind of was able to link it through theory, in some sense it was something that was in my head already but I could never put this out as structured, as reasonable, as sense making as after the course, I think [the thing] I took most out of the course, was this.

Secondly, the course participants seemed to become more aware of the uncertainties and complexities, and therefore the demands, of teaching. One of the participants, for instance, described coming to see the ‘grey’ and not just the ‘black and white’ of teaching (Karl’s interview). Part of the expanded awareness for some participants included greater awareness of the importance of student needs and motivations in the teaching and learning dynamic, and factors that impact on teaching practice, for example, ‘organisation policies and norms’ (Kim’s interview).

Participant comments also reflected a keener sense of what was needed for ongoing professional growth and learning. This included further reading (particularly for Lin and Karl), collegial support (particularly for Jacques), and being committed to continuous professional learning (e.g. ‘([I learnt that] it is important to constantly develop one’s own pedagogic skills and to get new ideas’ – Arya’s course evaluation). On the basis of this awareness, some of the participants were already engaged in further reading at the time of the interviews and/or starting to network with colleagues to discuss pedagogical matters, both in and outside the course group. This was a positive outcome given the importance of networking for the ongoing support of professional learning and sustaining changes to practices (see Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2011; Rienties and Kinchin Citation2014).

Thirdly, participants suggested that increased knowledge about alternative strategies and possibilities in teaching was an important area of professional growth. This is similar to findings in the Norton et al. (Citation2010) study (see participant comment about having his/her eyes ‘opened’ to ‘what and how much is out there’ [351]). In our study, the participants became aware of alternatives to teacher-centred approaches, as Karl’s comments illustrate:

I never thought there were other options, I mean … my academic life, most of the time was teacher centred … it’s school to university … and I think that was something that I was never really happy about, when you don’t have an alternative, then you don’t think about an alternative. (Karl’s interview)

[The course] gave me an understanding that a good lecturer is one who is not ideologically closed to one approach, but one who understands and makes use of the different possible methodologies to enhance learning according to … [several] factors in the classroom, such as the students’ profile, the subject … my idea of the possibilities for a good lecture changed (Karl’s course evaluation).

Increased knowledge about alternative ideas and approaches was linked by participants to choice about what actions to take as teachers. Also, because of their new or more nuanced pedagogical understandings, the participants were able to instructively reflect on and see their past experiences (as students or university teachers) in a new light. Jacques, for example, looked in a new way at high failure rates in his home country. He also described a realisation through the course that he had been ‘doing many kilometres without my students’ (Jacques’ interview) and not paying enough attention to how students were experiencing their studies. He talked about needing to attend more to the ‘process of assessment’ in his future practice to foster student learning and as a form of feedback on his teaching.

Changed self-confidence

The developing pedagogical understandings noted above were accompanied by changes to self-confidence in the participants’ abilities as teachers. This also varied from person to person. In two cases, the change appeared to involve a decrease in self-confidence, while others alluded to or described enhanced self-confidence.

Those who experienced an increase in self-confidence linked the change to greater awareness, a willingness to take risks, or increased self-efficacy. Arya, for instance, said, ‘I became more aware of my strengths and that I can be confident in my role as a lecturer’ (Arya’s course evaluation). She also came to realise that she did not need the answers to all questions as a university teacher, even if that were possible: ‘[Taking the course] has changed my view concerning the role of a lecturer, that a lecturer is rather a facilitator and does not have to be all knowing’ (Arya’s course evaluation). Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne (Citation2011) described similar comments in their study of emotions and self-confidence in university pedagogy courses (see also Sadler Citation2013).

This in some ways relates to the Jon’s experience. Jon talked about being initially preoccupied with making ‘safe moves’ as a teacher, which meant concentrating on content that was easier to teach and that made it easier to convey a sense of being an expert as a teacher:

You need some safe moves. You don’t want the students to see you doing something you don’t know. So you want them to make sure that they see what you are doing is correct … So therefore the difficulty levels stop because you want to be safe … it’s like you will use a simple … approach to show the … basic … phenomenon, so you are really not touching something at the cutting edge of the research. (Jon’s interview)

In a different vein, Jacques hinted at strong self-efficacy (Bandura Citation1986) in relation to a capacity to a focus on the learner in his teaching practice (‘I know it’s a process to – but now I think I can be a good teacher – paying attention to the learner’ – Jacques’ interview). This was enhanced through expanded understandings of the learner’s needs and interests in the educational process (cf. Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2011).

In the questionnaire responses, two participants noted feeling less secure in their teaching. The following interview comment by Karl gives an insight into how this was possible. Karl explained that increased knowledge about teaching and learning came with increased awareness of what he did not know, which led him to feel less confident:

I was more confident in the beginning of the course than in the end, and at the same time I consider that I have more knowledge now than I had before … I think the difference [is], that in the beginning I had no idea, no concept. As we increase our knowledge, I think you kind of decrease your confidence a little bit, because you realise that it is much more … it is a vast area of knowledge that you don’t know. And when you don’t know there is such a vast area of knowledge, you tend to be more confident. (Karl’s interview)

Contributing factors: enablers of professional growth

While we cannot definitively say what particular factors led to the development of a more holistic and nuanced understanding, and/or changes to self-confidence, we can point to key factors that the participants identified as relevant (either explicitly or implicitly). In the discussion that follows, we elaborate on these key factors. They relate to (a) course arrangements (in the general sense of the word ‘arrangements’) and (b) individual participant factors.

Course arrangements

All participants indicated that the course affected how they viewed teaching and learning in HE. Features of the course that were particularly highlighted included course content and course design, collegial learning activities and peer support, and diversity within the participant group. In terms of course content, it seemed that the participants’ ideas were challenged by an emphasis on learning and learners and reflective practice, rather than an emphasis on teaching methods and approaches alone. For example, in the peer observation assessment task, participants were encouraged to focus not just on what observed peers did in the observed lessons, but on the potential impact and implications for student learning and engagement. Also, as shown above in relation to Karl’s and Lin’s sense-making, exploration of educational theory and issues helped give order and intelligibility to previously un-theorised participant ideas and experiences. The participants encountered educational theory in a range of ways, including via workshops and lectures, and through engagement with the course text book, course readings, and additional literature sourced by the participants.

As for course design and the kinds of activities in which the participants engaged, the space and opportunity to reflect was deemed important. Arya commented, for instance, that the course allowed her space and time to think about pedagogy in a way she had not previously. As noted earlier, reflective activities were built into many aspects of the course, including self-reflections by participants about their own seminar presentations. The experiential nature of the course also appeared to be relevant for some. The course was designed to provide opportunities to experience real-life manifestations of some of the concepts being explored, for example, learning about student-centred approaches partly by experiencing and observing them. Some participants had still not had a chance to teach in a formal teaching role by the end of the course, and thereby act on or test their new ideas and pedagogical understandings in interactions with students. However, the seminar presentations provided at least some degree of space for trying out different ways of engaging learners, in this case, their peers and course facilitators.

Opportunities for collegial learning constituted another enabling factor. Collegial learning took the form of peer feedback, as well as discussions about particular cases related to university classroom dilemmas, and collaborative reflection on previous experiences and assumptions about teaching and learning and their relevance to Swedish HE. In this sense, the participants shared an ‘intense’ (Arya) collegial experience that allowed them to think about similar things, try out things together, while working towards similar goals. The participating group, in this way, became a learning community. Most of the participants explicitly mentioned the supportive character of this community. It provided a sense of comfort and a safe space to talk about teaching.

The sharing of stories, perspectives, challenges, and approaches within this supportive learning community was regarded as especially important by one of the participants (Jon) because it meant not becoming ‘stuck’ in particular ways of doing and seeing things. This relates to another key factor: diversity. The participants greatly valued the diversity of the participants’ backgrounds (country of origin, prior experiences, and disciplinary/professional backgrounds). The variety of backgrounds made for rich and lively discussion where multiple perspectives on a range of issues emerged, allowing the participants to expand their horizons in terms of understanding teaching and learning (cf. Kligyte Citation2011). Diversity in this sense was a resource for learning. The diversity of styles and perspectives of course lecturers was identified as enabling for similar reasons. Many of the sessions were facilitated by the two course directors. However, the programme also included guest seminars (e.g. ‘norms’ in HE from a norm-critical perspective; student motivation; and the use of digital technologies in the university classroom) by other university staff, each with his/her own style/approach to, and perspectives on teaching. Although not noted by the participants themselves, we believe that this was important for promoting awareness of the contested nature and complexity of education.

Individual participant factors

In the interviews especially, the participants revealed a range of individual factors relevant to the growth they experienced. Among these were their motivations for undertaking the course. Three of the participants were notably motivated by pedagogical dissatisfaction, supporting to an extent the case made by Ho (Citation2000) about university teachers’ tensions and dilemmas as impetus for moving forward conceptually. In the interests of space, we elaborate on two cases of this: those of Jacques and Arya.

In Jacques’ case, the dissatisfaction was with prevailing teaching orientations and strategies in his home-university department and home country. He described a highly competitive education environment characterised by greater concern for promoting the elite/brightest students than supporting student learning, a high failure rate (the ‘mark of a good teacher’), and the use of assessment ‘to prove that the teacher is strong’. Jacques referred to himself as a ‘victim’ of this system. Through the course, Jacques was able to find some answers to questions he had regarding how to bring about change in his own context and individual practice: ‘this approach [i.e. a student-centred approach] is like a response to what I wanted’.

In Arya’s case, there was a motivation to inspire her students in a way that contrasted with the traditional and rather authoritarian educational (and predominantly male) approaches she was frustrated by as a student. Arya reported having encountered positive role models who were much opposed to the content-centred and authoritarian approach of some male lecturers and that this gave her a sense of there being other ways of teaching in HE. Arya implied that the course provided an opportunity to explore the alternatives further.

Given such strong motivations going into this course, it is not surprising that Arya and the other participants were open to new ways of thinking about teaching and learning. The fact that the course was not compulsory, is also relevant. The participants were participating because they wanted to learn, not because course attendance was mandatory.

These examples highlight the relevance of prior experiences to the ways in which the participants engaged in and responded to the course. The participants’ experiences provided impetus for seeking knowledge, finding answers to questions, and/or exploring possibilities for doing teaching differently. The participants’ beliefs related to those past experiences arguably also mediated the participants’ sense-making during the course (Nespor Citation1987). In this way, the participants’ prior histories served as enablers for growth, especially in terms of prior experiences as students and university teachers.

Whether new and more nuanced pedagogical understandings might manifest as changed teaching practice, however, is another matter. As Karl pointed out, prior experiences, can work against the kind of self-confidence needed to act on new or altered understandings:

I could never start a new course, completely the opposite to what I have been doing my whole life, I think it would be a challenge … Like it or not, teacher centred [pedagogy] is something we are comfortable with, something that we’ve known for so long. I think the challenge is introducing more and more [student-centred approaches], until you feel super comfortable, to kind of be confident and powerful to make a change to- a structural change. (Karl’s interview)

The career trajectories of the participants also appeared to be relevant, although this was not mentioned directly. All participants were either doctoral candidates or post-doctoral researchers with strong researcher identities and a keen interest in theoretical matters of many different kinds. We wonder whether this had a bearing on the extent to which the participants assumed an inquiry stance and scholarly disposition (Wilkinson and Eacott Citation2013) to understand their histories and present and future circumstances as teachers (and or students). They certainly showed a desire to engage in ‘deep learning’ (Marton and Säljö Citation1976) throughout the course, which was most likely crucial for developing understanding.

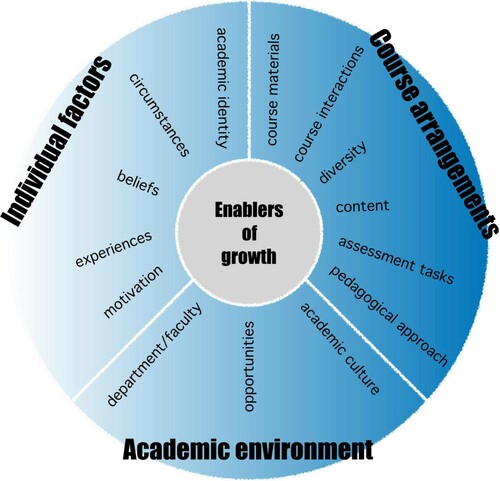

The following diagram () is our attempt to capture the main ‘enablers’ we have discussed, as well as some factors external to the course (but part of the broader academic environment) that were hinted at by the participants. Some of the main enablers are taken up for further discussion in the next section where we consider the implications and significance of the findings more closely.

General discussion and concluding remarks

According to the participants in our study, all of them came to see teaching and learning and/or their roles and/or their practices differently by the end of the course relative to how they saw them at the beginning of the course (cf. Åkerlind Citation2005; Kligyte Citation2011), and this was viewed in a positive way. Not surprisingly, given prior claims that professional growth is idiosyncratic and individual (e.g. Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002; Åkerlind Citation2003), our analysis highlighted that professional growth, especially in relation to pedagogical understanding and self-confidence, was experienced variously. Each participant clearly brought different resources to the course in the form of unique histories, capabilities, prior knowledges and understandings, identities, and motivations.

These resources not only mediated how and the extent to which each participant engaged and made sense of what he/she was encountering in the course. They also shaped other people’s experiences of the course. The participants drew on these resources, through feedback to peers, presentations, stories, questions, and comments, to help co-produce the course and provide stimulus for other people’s reflections. This is an argument, we suggest, for deliberately drawing participants’ prior experiences into class dialogue, as well as for interdisciplinary (or interdepartmental) pedagogical courses and other professional learning opportunities (and for diverse groups).

It is also an argument for space in courses for participants to consciously and collaboratively reflect on their practices and concerns about teaching, and their developing pedagogical understandings (Kligyte Citation2011). Although such space can be difficult to create in shorter pedagogical courses, we believe that it is imperative. New academics are professionally vulnerable to the extent that they are establishing their academic identity (Behari-Leak Citation2017) and thus can feel less inclined to share their thoughts about teaching with colleagues. Perhaps international PhD students and post-doc researchers could be even less inclined due to the power relations and cultural norms they possibly sense but do not yet understand, and due to the tenuousness of their positions as academics. Having the space and time dedicated to sharing and reflecting and even problematising aspects of teaching and learning may be actually crucial for their growth as teachers.

The role played by the course participant group as a supportive learning community is in line with the case made by others (e.g. Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2011) that peer support should be an important element of pedagogical courses. In order for this to be possible in the course we investigated, there needed to be a degree of trust within the groups, for as Tangney (Citation2014) notes, ‘learning is an emotional activity’ (273) and the sharing of views and stories can expose participants to negative judgement and ridicule. Although not mentioned by the participants, the small group size, and the fact that the participants shared common circumstances in terms of being new to Sweden and of undertaking (or having recently undertaken) PhD studies, may have contributed to the level of trust developed in the course if both helped them to realise they were not ‘alone’ (see Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2011, 804). The course directors were committed, along with participants, to setting a supportive tone and fostering trust, but we are aware that a culture of trust and support does not come easily in all groups, regardless of how small the groups are, or of what the group members have in common.

Significantly, our analysis suggested a role for peer or collegial support of new academics beyond pedagogical courses, especially with respect to the ongoing development of self-confidence. Self-confidence, as highlighted, can ironically be shaken when academics develop a more nuanced and holistic understanding of teaching and learning, and continuing professional learning opportunities may be important for restoring and (re)building confidence. Also, self-confidence may have more to do with factors that are beyond what a pedagogical course can influence, such as a person’s discipline-specific knowledge and familiarity with the particular situations in which people find themselves (Sadler Citation2013) or structural and systemic characteristics of the university (see Behari-Leak Citation2017). Furthermore, acting on new perspectives as we have discussed, requires some degree of risk when those perspectives run counter to what is comfortable, known, safe, or normalised in particular discipline areas. Again, a supportive community beyond the course peer group may be important for encouraging, or at least not discouraging, the necessary risk-taking to develop as teachers, and perhaps for surfacing and addressing some of the constraints for change. This may be equally relevant for academics in tenured or extended contract positions. There are obvious implications here for academic departments and the creation of supportive, reflective, inclusive academic environments. Mentoring arrangements (see Behari-Leak Citation2017), seminars on teaching and learning, and the careful management of new academics’ teaching responsibilities by course managers (see Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2011) come to mind.

Due to the small number of participants, we cannot claim that our findings lend themselves to general application. It is our conviction, however, that the insights gained from our findings further understanding of how course participants can experience professional growth. Whether and how the different ways of seeing teaching and learning manifested as doing teaching differently by the participants is not known, since neither the participants’ teaching practice nor their ongoing (informal) professional learning were part of this small-scale inquiry. We believe, however, that we gained insight into the potential for change in practice based on coming to ‘see things differently’ (Åkerlind Citation2005, 15).

What courses like the one we have described can contribute may be humble, but nevertheless important, as shown, for those whose teaching tasks are largely on the periphery of teaching and learning activities in a university: those of PhD and post-doc researchers. The challenge for those facilitating such courses is to create conditions that allow more nuanced and holistic pedagogical understandings to emerge, and raising awareness of factors that can affect self-confidence as pedagogical understandings are deepened.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the generosity and insights of the study participants, and all those who have been involved with the course.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Their rate being approximately 60% compared to an average of 40% for Sweden as a whole (Sveriges officiella statistic Citation2018; UKÄ Citation2018, 10).

2 For a counter view, see the discussion of a risk-taking disposition by Sutton and Wheatley (Citation2003, 348–349).

3 Compared with the university’s foundational course, the course investigated has fewer contact hours, attracts fewer credits (3 versus 15), takes place within a single teaching term, and is offered in English. While some of the content and general teaching approaches can be similar, the group size is smaller, and topics are not explored in as much depth.

4 Pseudonyms.

5 One of the three co-authors (co-researchers) is a former course participant. The other two were course facilitators at the time of the study. This composition of the co-researcher team has meant that both course facilitator and course participant perspectives have mediated analytical interpretations.

6 A discussion in which the course participants compared their pre-course and post course responses to the questionnaire was part of the final reflection activity in the course.

References

- Åkerlind, G. 2003. “Growing and Developing as a University Teacher – Variation in Meaning.” Studies in Higher Education 28 (4): 375–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507032000122242.

- Åkerlind, G. 2005. “Academic Growth and Development – How Do University Academics Experience it?” Higher Education 50 (1): 1–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6345-1

- Åkerlind, G. 2008. “A Phenomenographic Approach to Developing Academics’ Understanding of the Nature of Teaching and Learning.” Teaching in Higher Education 13 (6): 633–644. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802452350.

- Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Behari-Leak, K. 2017. “New Academics, New Higher Education Contexts: A Critical Perspective on Professional Development.” Teaching in Higher Education 22 (5): 485–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1273215.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Clarke, D., and H. Hollingsworth. 2002. “Elaborating a Model of Teacher Professional Growth.” Teaching and Teacher Education 18: 947–967. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7

- Derting, T. L., D. Ebert-May, T. P. Henkel, J. M. Maher, B. Arnold, and H. A. Passmore. 2016. “Assessing Faculty Professional Development in STEM Higher Education: Sustainability of Outcomes.” Science Advances 2 (3): e1501422. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Gibbs, G., and M. Coffey. 2004. “The Impact of Training of University Teachers on Their Teaching Skills, Their Approach to Teaching and the Approach to Learning of Their Students.” Active Learning in Higher Education 5 (1): 87–100. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787404040463

- Ho, A. 2000. “A Conceptual Change Approach to Staff Development: A Model for Programme Design.” International Journal of Academic Development 5 (1): 30–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/136014400410088

- Kligyte, G. 2011. “Transformation Narratives in Academic Practice.” International Journal for Academic Development 16 (3): 201–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Marton, F., and R. Säljö. 1976. “On Qualitative Differences in Learning: I – outcome and Process.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 46 (1): 4–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1976.tb02980.x

- Muganga, L. 2015. “The Importance of Hermeneutic Theory in Understanding and Appreciating Interpretive Inquiry as a Methodology.” Journal of Social Research & Policy 6 (1): 65–88.

- Nespor, J. 1987. “The Role of Beliefs in the Practice of Teaching.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 19 (4): 317–328. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027870190403

- Norton, L., O. Aiyegayo, K. Harrington, J. Elander, and P. Reddy. 2010. “New Lecturers’ Beliefs About Learning, Teaching and Assessment in Higher Education: The Role of the PGCLTHE Programme.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 47 (4): 345–356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Norton, L., J. Richardson, J. Hartley, S. Newstead, and J. Mayes. 2005. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Intentions Concerning Teaching in Higher Education.” Higher Education 50 (4): 537–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Pajares, M. F. 1992. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning up a Messy Construct.” Review of Educational Research 62 (3): 307–332. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

- Postareff, L., and S. Lindblom-Ylänne. 2011. “Emotions and Confidence Within Teaching in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (7): 799–813. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Rienties, B., and I. Kinchin. 2014. “Understanding (In)Formal Learning in an Academic Development Programme: A Social Network Perspective.” Teaching and Teacher Education 39: 123–135. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.01.004

- Robinson-Pant, A. 2009. “Changing Academies: Exploring International PhD Students’ Perspectives on ‘Host’ and ‘Home’ Universities.” Higher Education Research & Development 28 (4): 417–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Sadler, I. 2013. “The Role of Self-Confidence in Learning to Teach in Higher Education.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 50 (2): 157–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Sutton, R. E., and K. F. Wheatley. 2003. “Teachers’ Emotions and Teaching: A Review of the Literature and Directions for Future Research.” Educational Psychology Review 15 (4): 327–358. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026131715856

- Sveriges oficiella statistik. Statistiska meddelande. 2018. Higher Education. Postgraduate Students and Degrees at Third Cycle 2017, UF 21 SM 1801.

- Tangney, S. 2014. “Student-Centred Learning: A Humanist Perspective.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (3): 266–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- UKÄ [Swedish HE Authority]. 2018. Higher Education in Sweden. Status Report 2018:10.

- Wilkinson, J., and S. Eacott. 2013. “‘Outsiders Within’? Deconstructing the Educational Administration Scholar.” International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice 16 (2): 191–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422.

- Yin, R. K. 2006. “Case Study Methods.” In Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research, edited by J. Green, and Associates, 111–122. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.