ABSTRACT

The focus of this paper is on the contestations and dilemmas emergent in the higher education curriculum in a context of increasing processes of unbundling, digitisation and marketisation. The paper explores the notion of contestation through the theoretical lens of Cultural-Historical Activity Theory. It points to illustrative examples of this contestation from empirical data drawn from stakeholder research in South African higher education. The paper grapples with understandings of the concept of curriculum and argues how these have been shaped by – and are shaping – emergent meanings of the curriculum in an unbundling context. The argument is that these emergent meanings are a function of different explicit and tacit understandings of curriculum and what higher education offers to students. These understandings are deepened or modified by processes of unbundling. Empirical data from the research study show these understandings to be forming against the backdrop of powerful cultural and agentic forces and players.

Introduction

The concept of unbundling as applied to higher education has a history that dates back some decades (Gehrke and Kezar Citation2015), with our specific interest being on unbundling in relation to educational provision. Scholars and practitioners have variously provided useful understandings of the term in this context. Thus, for example, Lawton et al. (Citation2013, 23) describe unbundling as ‘ … the de-linking of teaching provision from qualifications gained’, while Gehrke and Kezar discuss it as ‘pertaining to the differentiation of university and faculty tasks’ (Citation2015, 93). Staton (Citation2012) refers to unbundling as ‘Disaggregating the components of a college degree’ and MacFarlane (Citation2010, 464) claims that ‘ … academic work is being subdivided into specialist functions’. The increasing prevalence of the term in higher education literature – whether defined at an institutional services level or at a faculty roles level – is leading to greater interest in empirical research into the impacts of unbundling (Gehrke and Kezar Citation2015).

Of particular relevance to notions of curriculum and unbundling, Staton (Citation2013) describes the components of a college degree as seen from a student’s perspective and how these might be unbundled. Staton conceptualises what a student gets when buying a college degree across four dimensions which include the knowledge-acquisition and knowledge-making dimension; the graduation and access to networking dimension; the meta-cognitive and meta-skill dimension; and the personal development and civic citizenship dimension. His purpose is to break down the elements of a college degree into constituent parts and, while a broader curriculum is possible to give students the full college degree experience, the disaggregated components indicate the ease by which the components can be unbundled.

Staton’s contention appears to be that if the college degree and broader curriculum are unbundled, the student will get the same unbundled (curriculum) experience, but efficiencies in costs will have been achieved. Others, however, are more sceptical about the possible impacts of unbundling higher education, with McCowan (Citation2017, 13) posing the question, ‘Are the components of higher education in this way interrelated, interdependent, and mutually reinforcing, with unbundling thereby entailing their undermining and impossible destruction?’. Our interest in this paper is to explore empirically the intersection between curriculum and unbundling, digitisation and marketisation and propose that – out of this intersection – a different understanding of curriculum and its processes emerges.

For the research project referred to in the introduction to this paper and about curriculum, the following working definition of unbundling has been adopted – a definition that flows from the literature on digitisation and marketisation and points importantly to the impact of unbundling on higher education provision and curriculum:

Unbundling is the process of disaggregating educational provision into its component parts likely for delivery by multiple stakeholders, often using digital approaches and which can result in rebundling. An example of unbundled educational provision could be a degree programme offered as individual standalone modules available for credit via an online platform, to be studied at the learners’ pace, in any order, on a pay-per-module model, with academic content, tutoring and support being offered by the awarding university, other universities and a private company. (Swinnerton et al. Citation2018)

We now explore the conceptualisations of the higher education curriculum and propose a set of understandings as a backdrop to our argument. After offering a definition and description of unbundling, the paper sets out to interpret processes underpinning higher education curriculum in the context of unbundling. We use cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) (Engeström Citation2001; Roth and Lee Citation2007) as a lens through which to understand curriculum activity as a process mediated by unbundling. In our view, CHAT offers a useful systemic lens to view the intersecting and inter-related activities of curriculum and unbundling while avoiding or reducing the possibilities of viewing either set of activities as deterministic or causally related to one another. Furthermore, CHAT offers the possibility of viewing curriculum and unbundling as multi-dimensional systems, with both implicit and explicit cultural histories, that intersect and interact with each other and with other systems of activity. As such, these systems have agency and are imbued with power, and the relation between them arguably produces a new emergent activity that is more than or different from the sum of its constituent parts. We use CHAT to analyse interviews with senior higher education leaders focusing on the inter-relation between curriculum and unbundling. The paper concludes with a critically evaluative look at CHAT as a useful theory for this kind of systemic analysis and proposes further lines of enquiry beyond those which form the subject here.

An exploration of understandings of higher education curriculum enables us to analyse whether understandings of the curriculum are being influenced by the processes of unbundling. Curriculum theorists essentially propose a continuum of understandings of what curriculum means, ranging from instrumental content and product-oriented approaches to holistic and transformative approaches where the curriculum is seen as co-constructed and emergent. Bali (Citation2013) describes and expands on these four orientations:

curriculum as content transmission;

curriculum as product;

as process; and, finally,

as praxis.

The first orientation, curriculum as content transmission, essentialises curriculum as reproductive, uncontested and assimilationist. The roles of lecturers and students in relation to disciplinary knowledge are replicative and iterative: knowledge is packaged in particular stable ways and handed down to students, whose role is to acquire and apply that knowledge. Pedagogy is transmissive and aimed at enabling student assimilation and participation in existing knowledge structures. The second orientation, curriculum as a product, assumes a relatively stable and static, commodified view of curriculum, and is perhaps most closely aligned with original conceptions of unbundling in higher education (McCowan Citation2017). As objects or commodities, various aspects and functions of the curriculum – such as content delivery, teaching and learning, academic support, assessment – can be packaged and repackaged to suit the needs of key players, such as lecturers, students, content specialists and the like. Pedagogy is also seen as a commodity, which can be packaged and repackaged to suit similar needs.

The third and fourth of Bali’s orientations, curriculum as a process and a praxis, is arguably more closely aligned with CHAT principles (later in this paper). In these two orientations, the curriculum is much more seen as mutable, emergent, tacit as well as explicit, and aimed at critical engagement and transformation of content, lecturers and students, ways of thinking, reflecting and being. Pedagogy, as an integral component of curriculum, is critical, self-reflective and embedded in mutating forms of knowledge production and reproduction, and imbued with goals of social justice and parity of participation by all role players (see, for example, Fraser (Citation2005) and Walker (Citation2012)). Bernstein defines curriculum as ‘what counts as valid knowledge’ (Bernstein Citation1975, 85). This definition ‘places knowledge at the center of its conceptualization of curricula’ (Shay Citation2015, 432). ‘What counts’ also signals that curricula are constituted by a set of choices. Bernstein (Citation2000) summarises these as choices ‘about selection (the content of the curriculum), sequencing (what order/progression), pacing (how much time/credit), and evaluation (what counts for assessment)’ (Shay Citation2015, 433). Finally, Walker (Citation2012, 449) argues that:

A curriculum encapsulates value judgements about what kinds of knowledge are considered important, for example the ethical dimensions of biotechnology advances, or the equal importance of exposure to arts and science for all students, or the literatures that are studied. But a curriculum further indicates with what attitudes and values students are expected to emerge in respect of the knowledge and skills they have acquired, e.g. the uses of scientific knowledge or historical understanding. As such, curriculum is a statement of intent, but there may be practical gaps between the aims of those constructing the curriculum and implementing it and what is actually learned by the students who experience the curriculum. Moreover, knowledge carried by a curriculum has significant effects and projects into anticipating and preparing for the future and future persons.

Given the background developed in the foregoing, two substantive arguments are made here about the concept of curriculum:

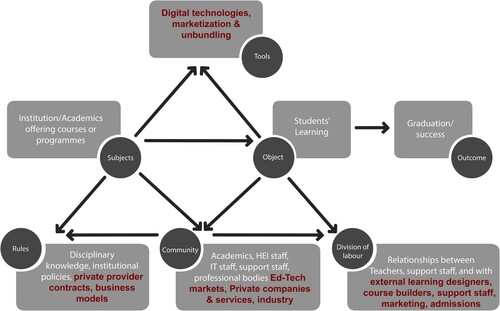

The curriculum is essentially a mental construct which might be represented as an intersecting and dynamic set of knowledge-objects (the CHAT nodes in ); and

These knowledge-objects might be (a) disciplines and their knowledge structures, including knowledge of teaching, learning and assessment activity; and (b) embedded social and material contexts, including connections between sites of teaching and sites of practice, platforms for engagement and role players who have agency, power and different roles (the tacit dimensions represented in the base of the CHAT activity triangle, , in particular).

Curriculum, unbundling, digitisation and marketisation are a set of intersecting eco-systems that are mutable, contextual, dynamic and responsive and have agency.

Theoretical framework: Cultural-Historical Activity Theory

The following section of the paper argues CHAT as an important theoretical framework for understanding and interpreting the intersections and contestations that arise from these eco-systems and argues that CHAT is a useful analytical lens for understanding the dynamic nature of these eco-systems.

The relationship between curriculum, unbundling, digitisation and marketisation might be depicted as an activity system whose behaviour and intention mirror the relational elements (see and discussion further on). Conceptually viewing the eco-systems as multi-dimensional enables the exploration of the explicit and tacit contestations in the system, which provides the essential energy of this paper and a framework for analysing empirical data. Unbundling, digitisation and marketisation are giving rise to new contestations in the higher education space. And the relationships between these three processes and curriculum processes are emergent, not linear, and difficult to describe as causal. One process has not caused another; curriculum in the emergent space is shaping and is being shaped by the other processes. Each process has an agency and power that is both determining of and determined by the others. As a theory of Activity Systems and their socially situated inter-relations, CHAT has attracted a substantial amount of interest, debate and application particularly in the last 20 years or so (Roth and Lee Citation2007). ‘Because CHAT addresses the troubling divides between individual and collective, material and mental, biography and history, and praxis and theory (e.g. Cole Citation1988), we believe that it is deserving of wider currency in the educational community’ (Citation2007, 191). Our use of CHAT is in reference to third-generation Activity Theory (AT) and the activity triangle centrally explicated in the work of Engeström (see, for example, Citation1987, Citation2001). The primary reason we have chosen a third-generation AT focus is precisely because of its focus on intersecting systems of activity: the intersecting systems of curriculum, digitisation and marketisation. While we might have selected another theory such as Actor-Network Theory, CHAT’s strengths are that it foregrounds both the intersection and the systems, yet still enables an analysis of the human and the context, and the extent to which power operates within these systems. CHAT has developed from a sociocultural theory of learning, so is particularly appropriate when analysing Higher Education in a learning organisation context.

CHAT is a useful methodology for understanding and describing human activities, seeing them as systemic and socially situated phenomena where ‘what takes place in an activity system … is the context’ so that ‘context is not just “out there”’ (Nardi Citation1996, 78). Accordingly, researchers in education have deployed CHAT in several ways. Murphy and Rodriguez-Manzanares (Citation2008) found CHAT useful for characterising contradictions after educators transitioned to a virtual high school classroom, while, in another study, Hardman (Citation2005) used CHAT to investigate pedagogical transformation in a rural school once computers had been introduced. Trowler and Knight (Citation2000) used CHAT to understand new academics’ socialisation and ways of knowing when entering higher education as a workplace, while Peruski and Mishra (Citation2004) applied CHAT to examine the collaboration between faculty members making online courses and identified emerging contradictions. These studies indicate that the CHAT lens provides a useful way for explaining human activities systemically and is of particular resonance to educational contexts in which change is catalysed or mediated through the introduction of new tools and approaches into an existing complex system.

Our interest is in exploring in what ways and to what extent does CHAT illuminate and contribute towards an understanding of curriculum in the context of unbundling, digitisation and marketisation? If we now apply the discussion above to a particular example of the curriculum process, we respond to this question.

As can be seen from , subject, object and outcome in the activity triangle/pyramid are here represented as multi-dimensional processes at the curriculum level of teaching, learning and graduation or success. Complex, socially situated, relational acts of teaching intersect with and have their counterparts in learning and – in overall curriculum terms (see Staton earlier) – lead to graduate ‘outcomes’. Of course, it would be possible to view the curriculum in other ways or to select a more atomistic level of analysis of curriculum, but these would arguably lend themselves to a similar analytical discussion as is presented here.

What CHAT particularly enables in a discussion about the enactment of a curriculum here is engagement with the intersecting explicit and tacit contexts of unbundling, digitisation and marketisation as a way of understanding these contexts as sites of contestation. depicts these sites of contestation as applied in the activity triangle/pyramid with those elements of possible contestation marked in red/bold. Of particular interest in this argument is the base of the triangle, where lie the rules that undergird activity systems, the communities which form the social and material contexts in which these activity systems cohere, and the division of labour systems in which roles and power can be expected to be played out. Additionally, the apex of the triangle (the place where mediating artefacts or tools are inserted into the system) is worth analysing in this argument, as being the site of contestation of provision (learning technology platforms, modes of delivery, forms of pedagogy) in increasingly digitised curricula spaces.

Three dominant eco-systems intersect with curriculum in this figure: unbundling as the disaggregation of curricula into standalone units or components; digitisation as the increasing availability of online, blended or flexible modes of curriculum provision in conventional or unbundled – or re-bundled – higher education environments; and marketisation as the extent to which private providers of education increasingly play in, profit from and offer curriculum solutions in the new, emergent disaggregated, technologised curriculum space. Conceptually, these ecosystems intersect with and mediate the Activity System in which curriculum is enacted – the object of which is student learning.

CHAT and its focus on activity systems help us to analyse and interpret processes and contestations in each of the activity ‘nodes’ and across the system(s) as a whole. In the tools space, material and social activity systems such as online and flexible educational technology platforms and modes of provision demand – at a minimum – a response at the curriculum level of engagement. Tools here are mediating artefacts for the delivery of curriculum and what unbundling, digitisation and marketisation have meant is a new, emergent curriculum reality that is situated on a continuum between conventional, blended and fully online modes of provision. Contestation in this space relates to the pedagogical, socio-cultural and material rules, communities and divisions of labour histories, practices and belief systems that are represented in curriculum, unbundling, digitisation and marketisation – and the human and material ‘actors’ (including students) that contest this space, imbued as they are with agency, differential forms of power and abilities to co-construct forms of engagement and outcomes.

In the rules space in the figure, higher education curriculum with its own disciplinary, design and pedagogical knowledge systems and practices intersects with the knowledge systems and practices of digitisation (technology), curriculum unbundling, and marketisation or market-making (Komljenovic and Robertson Citation2016) to produce further contestation. Opportunities afforded by unbundling interact with curriculum design and pedagogy in an increasingly marketised space. At a blunt level, where knowledge systems and practices – rules of engagement – are mutually exclusive (unlikely), contestation would lead to an impasse between curriculum, digitisation and marketisation. A more likely scenario is that each system attempts to impose, blend or integrate its rules with the other (using collective agency and explicit or tacit power) to produce a new, emergent curriculum reality.

In the community space, processes of unbundling, digitisation and marketisation have most interestingly resulted in the merging of socially situated communities of practice (cf. Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Wenger Citation1998) that have historically been seen as mutually exclusive. Marginson (Citation2013), Tomlinson (Citation2018) and others have recently argued that the higher education community is irreconcilably different from private, for-profit, market-driven communities – particularly with regard to higher education as a public good, although there is an acknowledgement that some forms of market-making are in operation. CHAT and activity systems can enable an analysis of how different knowledge and practice communities do intersect in increasingly unbundled, digitised and marketised spaces, not least by signalling an analytical engagement with the explicit and tacit meanings associated with ‘community’ and how these are similar or different.

In terms of the division of labour space, of particular interest here from an activity systems perspective are the ways in which different role-players including new players entering the space in higher education curriculum act pedagogically, technologically and in terms of markets. At a minimum, unbundling, digitisation and marketisation call for questions into whose interests are served and how players move to shore up, replicate and reconfigure the space. Of even more importance are questions around the hegemonic spaces, how power is contested and negotiated, how human and material agency operate, and how these produce change or reinforce the status quo. Here we refer back to our earlier discussion about what is meant by curriculum – whether it is conceptualised as content, product, process or praxis, and to this, we add the question as to who defines what curriculum is and how it is enacted. In terms of division of labour, unbundling, digitisation and marketisation have arguably given rise to contestations around what it means to be a higher education curriculum specialist – with attendant debates about the historical notion of academic specialism – in the context of competing specialisms in educational technology (digitisation), private provision and curriculum design (the markets) and the disaggregation and re-aggregation of curriculum provision (unbundling) to make higher education more flexible, competitive internationally and – so it is claimed – more responsive to changing student constituencies, internationalisation and institutional branding.

Findings from the South African research project

The findings and analyses that follow derive from qualitative data (interviews) with individual South African higher education stakeholders (n = 23). Interviews were conducted by members of the project team and were wide-ranging, but our interest here is on what these stakeholders had to say about the impact of unbundling on the curriculum. Interviews were transcribed and then coded using NVIVO software. Codes for the categorisation of interview excerpts were initially established by three project researchers. These codings were then reviewed and debated by other members of the project team before final codes were agreed. The excerpts below were drawn from the following codes (or their synonyms) in the data: curriculum; teaching, learning, assessment; students. Selection of interview excerpts for this paper was based on ensuring that we reflected as much variation of perspective as possible.

For reasons of brevity, not all interview data can be reflected, but we drew on data from three historical classifications of South African higher education institutions according to their fundamental purpose, and reflective of the variation desired: research-intensive, comprehensive (teaching-focused, but emergent applied research-focused) and teaching-intensive. In selecting a range of institutional stakeholders, we intend to illustrate key trends and discourses. Swartz et al. (Citation2019) provide an overview of the history and contextualisation of South African Higher Education. In essence, their paper points to the State-driven, post-1994 classification of the (then) 23 Higher Education institutions into three broad categories, according to their core focus and based on their histories as shown in .

Table 1. Summary of the dataset by Higher Education institutions and type.

The four interview excerpts represent views from three higher education stakeholders spanning this range with the addition of the State perspective as the chief custodian and regulator of higher education in South Africa. All stakeholders interviewed were institutional executive-level staff, specifically Vice-chancellors or Deputy Vice-chancellors. The interviewee from the State holds an executive position in the office of the Director-General, Higher Education.

From an analytical point of view, the interview excerpts below are approached through the lens of CHAT as a way of interpreting the intersection of unbundling, digitisation (including online modes) and marketisation as multi-dimensional ecosystems in a curriculum space.

Excerpt 1: the state view

Excerpt 1 below foregrounds the higher education curriculum contestations among research, innovation, development as well as the wider purposes between economic imperatives and community development.

So, it’s not, not to say that, that institutions should, I mean that higher education should be commoditised to the, to the nth degree or something like that, but it’s about how do you, how are higher education institutions interacting in the, in the economy and how are they interacting within the context in order to create opportunities for funding for, for research, for innovation, for development. And, and that development is not only just about the development of, you know, new, new ideas from a knowledge production perspective but it’s also about community development and the development of, of the localities in, in the area and, and how they engage in that. [Senior Leader, State Department of Higher Education and Training]

However, they acknowledge the roles of the markets in higher education – the rules and community nodes in (referring to the sector becoming commoditised), and the realist contributions of the markets and the economy to knowledge production, but draw a clear distinction between these and community development in local settings. Markets serve as a mediating mechanism, but in terms of divisions of labour, the interviewee sees themselves (and, by implication, the department whom they represent) as acting in defence of both the public good and the private value of the sector. The object of what constitutes curriculum in public higher education is local and social development-driven against the backdrop of the potential opportunities enabled by private engagement. Again, in this excerpt, market discourses and higher education discourses have become inter-related – but they sit perhaps a little less comfortably in this excerpt than they do in the following excerpt (excerpt 2).

Excerpt 1 points to the cultural-historical contestations around the regulatory or mediating mechanisms of the state in the purposes of public higher education (between commodification and development) and the opportunistic nature of the markets in contributing to research, innovation and development. The excerpt suggests not only the agency of the state in playing in the market-place, but also potential challenges in retaining its rules and communities of engagement in the regulatory space.

Excerpt 2: research-intensive institution view

Excerpt 2’s interviewee is a Vice-Chancellor from a Research-Intensive university. Here they refer to the curriculum for residential undergraduate students:

I would like all students to have, .. have a breadth of disciplinary education outside of their main disciplines; so some people call it ways of thinking, different disciplines and different professions have different ways of thinking about the world, and I would like to see students' understanding, graduates' understanding that there are different ways of thinking, so that they don’t think that their way of thinking is the only right way, and for that, they should ideally take courses that draw on those different ways of thinking. So I would like all natural scientists to do a course in either anthropology or literature or something … it’s brought outside of their field and it highlights ways of thinking and seeing the world that are different from their main discipline. Now in that regard I haven’t had the success ‘cause everyone is too protective of the curricula, of what’s in it and not being able to fit more, [Vice-chancellor, Research-Intensive university]

I don’t anticipate that there would be any savings of staff through the online learning, but I do anticipate that everyone could generate more revenue. So, one wouldn’t lose the staff or have to reduce the staff, but then once you’ve got something good online you can extend it to the population of students that you don’t have on campus because the campus is full, we can’t grow anymore, and you could do that in two ways: one is you could franchise it out to other universities, so I think for us a good market is the African market … And that would require us to have more staff, but that staff, the extra staff would be covered by, by the extra income; and that’ll also improve our brand and our reach. So, I haven’t really heard of any models where it replaces people within the same university. I think it does present a threat possibly to other universities … [Vice Chancellor, South African Research-Intensive University]

The cultural-historical context of the institution here is associated with privilege, endowment, entitlement and wealth, and diversity is an affordance. The institution has an agency to be able to position itself as a leading player in a market. This represents a potential expansion of the object of the activity system, given that the university’s reach can expand to more students and service (for a fee) other less-resourced institutions. It can manage the tensions between private and public good; it is flexible and responsive to new modes of provision; it can extend its competitive ‘edge’ in the sector and simultaneously enact a public service to others in the sector (or the African region). There is an implicit belief in the value of the offering (the franchise) and the assumption that this value is desired elsewhere (the African market), which suggests a view of curriculum as a product albeit for other institutions.

Division of labour and roles in this context are flexible, and the socio-cultural communities of higher education, technology and the markets can happily co-exist. Discourses around the meaning and purposes of higher education are marketised and modernised to accommodate the current realities of the massification of higher education and the need to provide access for virtual students or students who might otherwise not be catered for while maintaining the holistic curriculum for residential students.

However, in the same interview the respondent acknowledges the possible contestation around curriculum changes and adoption of digital technologies, with one solution to make people aware of what other institutions within a broader community are doing to try and influence people who might resist changes:

… one can’t simply persuade people to switch to digital technologies or to change the content of their curriculum to include say digital humanities … by order, or by diktat, you have to do it through … through motivating them, through making the case and I find what is important, because people are very concerned about what peers think in the academic environment that one effective way of doing that is to bring along peers from respected institutions that are already ahead of the curve.

Excerpt 3: comprehensive (urban) university view

I think the two things to look at with regard to online, and this is the way in which I have approached it, one is access to higher education. At the moment we – you know, even if we wanted to massify higher education, we don’t have the infrastructure in the country to – to accommodate the increased numbers in higher education. Government certainly doesn’t have the money to create even more universities than it’s already done. And the – the fees must fall, you know. There’s a lot of emphasis on government providing financial support to students, those that are in higher education, so it’s not going to be able to expand that pocket of – of resource envelope beyond what it currently has. … So the – the – the online programs is an opportunity to tap into that particular applicant pool. [Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Comprehensive University]

Excerpt 3 introduces student dimensions into the present discussion and locates unbundling, digitisation (expressed here in its form as online provision) and marketisation in relation to critical issues of face-to-face and remote student access, massification in higher education and the opportunity of differential forms of curriculum delivery, including online options.

The mediating artefacts or tools (online learning) are seen somewhat here as a panacea to resolve issues of student massification, access and inequities as a solution to a challenge which is not resolvable elsewhere (‘Government certainly doesn’t have the money’). As role-players in this context, the state is constructed as an inadequate funder and physical resource provider and the higher education institution as having the flexibility to respond to the state funding crisis and to contribute to the resolution of the twin challenges of under-funding and student access. The reference to the Fees Must Fall movement is presented as a reason for the large-scale launch of online curriculum provision and a solution to the physical and socio-cultural (small group) disruption of students to the mass right to access to higher education. At the same time, the market opportunity of being able to tap into that particular applicant pool is also hinted at. Yet the interviewee expresses doubts about the curriculum experience online students might have:

I don’t think it’s ever going to replace the kind of content environment that higher education provides. I think at the end of the day, students … want to be able to come to university; they still want to have the kind of contact, the social, I mean because university is more than just what you do in a classroom. It’s also about the whole kind of feeling of, you know, making friends. You’re not going to be able to necessarily do that if you’re sitting at home, like just doing work on online programs.

I think one would have to be very careful that online programs doesn’t (sic) – doesn’t end up so it’s, you know, and I don’t think that it would, but I would be very concerned if an online market is intended for a certain segment of a population and the more wealthy and privileged come to the university and the less privileged and – and – would be the ones that go on online. I think that at the end of the day one would need to – to look at that. But at the end of the day it’s also a way of allowing students to both work and – and study at the same time. And, you know, I think what we are seeing globally is that, you know, there’s increasing need for – for – for students to both work and study simultaneously. Higher education is simply becoming unaffordable.

Excerpt 4: comprehensive (rural) university view

How do we embrace the knowledge of the people that are surrounding the university into our own curriculum? How do we do that without taking over or trying to educate them, but rather we work as, in partnership?

… It is the future of higher education to ensure that when students go through our curriculum they get out of it ready for, for the world. [Vice-Chancellor, Comprehensive University]

In this particular case, the interviewee goes on to express uncertainty around disaggregation of teaching and learning, linking again to an understanding of curriculum enactment that leads to a particular type of graduateness:

But we have not been approached on outsourcing. That’s a scary concept, outsourcing education …

I think probably my, my reaction comes from anything that is change, you fear that it might not necessarily be … Although I think we are so used to, in education, to taking ownership of the programmes and taking ownership of how you do things, and therefore you, it gives you certainty on the graduateness of, of your students at the end.

I’ve always been, as a, as a person in education, not been very flexible, even in terms of getting outside people come and teach or mark students because I’ve always said marking yourself your scripts for your students gives you an insight on how your students are doing.

Even though this comprehensive rural institution has not been approached by private companies for online education provision, the interviewee is aware of and concerned about the perceived needs of the broader market and of the industry in terms of the potential curriculum offering. As the following excerpt illustrates, this provides an area of contestation around curriculum given it affects what students are taught.

Somewhere there’s been an appetite from the industry point of view to want to prescribe to universities that this is what the programme they would expect, yet higher education has got our own agenda or mandate in terms of the curriculum that we deliver.

for me, … the push to, to bring more of the industry in the classroom might be taking away some of the, the critical issues about that particular subject. And therefore, if we are wanting to produce, in the future, intellectuals in terms of that specific area, that could be taken away or usurped by their, their desire to, to make them practitioners at the same time.

It is our view that this is a cultural contestation: the for-profit, competitive culture of the market or needs of industry bumps up here against the for-public good, locally responsive culture of this rurally located institution – a contestation hinted at in Excerpt 1. The rules and community are expanding to include industry needs, which for this interviewee impacts on the type of curriculum that is taught, which, in turn, threatens an intended agenda and outcome – those of student development and producing a particular socially aware, intellectual graduate.

Discussion

A generalised view of the excerpts above allows us to view online, blended and flexible forms of curriculum delivery in relation to their dialectic category pair: conventional, face-to-face forms of delivery. As socio-material entities, the affordances, limitations and contestations of online or face-to-face curriculum delivery (as opposite ends of a continuum) are usefully understood by reference to this continuum. In a similar manner, digitised or non-digitised forms of the curriculum can be seen as a dialectic, as might marketised or non-marketised forms. In this argument, dialectics is not focused on the binary between online and face-to-face curriculum delivery, for example, but on the ways in which the affordances and challenges of these forms of curriculum are enacted in higher education teaching and learning contexts, by different interest groups and players, imbued with differential forms of individual and structural power. The differing attitudes expressed by our interviewees towards an unbundled curriculum offering is testament to this.

In the activity system, power operates at micro, meso- and macro-levels. The individual lecturer, making curriculum delivery choices, is able, as a function of his or her agency, to make choices about the extent of online or face-to-face curriculum engagement; but so are his or her students, colleagues, and so on. At the meso-level, academic programmes or departments may make similar choices, and, at the macro-level, so may institutions or whole higher education systems. And these levels intersect or interact with one another in predictable and sometimes unpredictable, human and material ways, with their own resistances, reluctances and resiliences, which give rise to emergent and contested forms of curriculum provision. To the extent that the subjects, objects and outcomes of these activity systems are convergent or divergent, consonant or dissonant, different forms of emergence will arise as a consequence of the interplay among the rules, communities and divisions of labour that pertain to the activity system.

Furthermore, the dialectic between market and non-market is particularly interesting. The dynamics of market-making have presented the higher education curriculum space with particular opportunities to consider its purpose inter alia as public vs private good, profit or not-for-profit motive, aggregated, disaggregated or perhaps the re-aggregated mode of provision, compartmentalised or integrated offering, and so on. It is perhaps in the marketised space that the contestations between unbundling, digitisation and curriculum as an activity system are most clearly visible.

At the micro-level, academics (and students) are at the confluence of profiting (sometimes literally) from their knowledge-making and pedagogy, contributing to student development and graduates as a public good, delivering curriculum in its totality or ‘selling-off’ some or all of its components. At the meso-level, teaching programmes or academic departments, for example, intersect with the market in offering or ‘consuming’ online curriculum provision or parts thereof. At the macro-level, whole institutions get to ‘play’ in the curriculum space alongside – or intersecting with – private providers offering curriculum solutions or responses in an unbundling higher education context.

In the unbundling, digitised, marketised curriculum space, there are multiple subjects, objects, outcomes, mediating artefacts, rules, communities and divisions of labour. And there are many potential or actual dialectical pairs. It is this multiplicity which makes engagement with the curriculum (and how it is conceptualised) so dynamic and contested. We believe this study to provide the beginnings of a framework of engagement for Higher Education curriculum designers and developers, which addresses the nexus between curriculum, digitisation and marketisation through the following lenses:

How does the higher education sector interact with external providers and forces in an unbundling, digitising, marketising space and process?

How is power distributed, contested and negotiated in these activity systems?

How do different role-players – each with their own changing cultural-historical ontologies and epistemologies – navigate and negotiate relationships and engagements with each other?

Whose interests are served in these networks of activity, particularly in the context of inequality of provision such as in South African higher education?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bali, M. 2013. “Critical Thinking in Context: Practice at an American Liberal Arts University in Egypt.” PhD diss., University of Sheffield. http://dar.aucegypt.edu/handle/10526/3721.

- Bernstein, B. 1975. Class, Codes and Control: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmission. London: Routledge.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Cole, M. 1988. “Cross-cultural Research in the Sociohistorical Tradition.” Human Development 31: 137–157. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000275803

- Engeström, Y. 1987. Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research. Helsinki, Finland: Orienta-Konsultit.

- Engeström, Y. 2001. “Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity-Theoretical Reconceptualization.” Journal of Education and Work 14 (6): 133–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747.

- Fraser, N. 2005. “Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World.” New Left Review 36: 69–88. https://newleftreview.org/issues/II36/articles/nancy-fraser-reframing-justice-in-a-globalizing-world.

- Gehrke, S., and A. Kezar. 2015. “Unbundling the Faculty Role in Higher Education: Utilizing Historical, Theoretical, and Empirical Frameworks to Inform Future Research.” In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research: Volume 30, edited by M. B. Paulsen, 93–150. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12835-1_3.

- Hardman, J. 2005. “An Exploratory Case Study of Computer Use in a Primary School Mathematics Classroom: New Technology, New Pedagogy?” Perspectives in Education: Research on ICTs and Education in South Africa: Special Issue 23 (4): 1–13.

- Komljenovic, J., and S. Robertson. 2016. “The Dynamics of ‘Market-Making’ in Higher Education.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (5): 622–636. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1157732.

- Lave and Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lawton, W., M. Ahmed, T. Angulo, A. Axel-Berg, A. Burrows, and A. Katsomitros. 2013. Horizon Scanning: What Will Higher Education Look Like in 2020? Observatory on Borderless Higher Education. http://www.obhe.ac.uk/documents/view_details?id=934.

- MacFarlane, B. 2010. “The Unbundled Academic: How Academic Life is Being Hollowed Out.” In Research and Development in Higher Education: Reshaping Higher Education, edited by M. Devlin, J. Nagy, and A. Lichtenberg, 33, 463–470. Melbourne. http://www.herdsa.org.au/publications/conference-proceedings/research-and-development-higher-education-reshaping-higher-40.

- Marginson, S. 2013. “The Impossibility of Capitalist Markets in Higher Education.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (3): 353–370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.747109.

- McCowan, T. 2017. “Higher Education, Unbundling, and the End of the University as We Know It.” Oxford Review of Education 43 (6): 733–748. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1343712.

- Murphy, E., and M. Rodriguez-Manzanares. 2008. “Contradictions between the Virtual and Physical High School Classroom: A Third-Generation Activity Theory Perspective.” British Journal of Educational Technology 39 (6): 1061–1072. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00776.x.

- Nardi, B. 1996. “Studying Context: A Comparison of Activity Theory, Situated Action Models, and Distributed Cognition.” In Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction, edited by B. Nardi, 69–102. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Peruski, L., and P. Mishra. 2004. “Webs of Activity in Online Course Design and Teaching.” Research in Learning Technology 12 (1): 37–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0968776042000211520.

- Roth, W., and Y. Lee. 2007. “Vygotsky’s Neglected Legacy: Cultural-Historical Activity Theory.” Review of Educational Research 77 (2): 186–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654306298273.

- Shay, S. 2015. “Curriculum Reform in Higher Education: A Contested Space.” Teaching In Higher Education 20 (4): 431–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1023287.

- Staton, M. 2012. “Disaggregating the Components of a College Degree.” American Enterprise Institute. Accessed 21 December 2018. http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/-disaggregating-the-components-of-a-college-degree_184521175818.pdf.

- Staton, M. P. 2013. Unbundling Higher Education, a Doubly Updated Framework. Edumorphology.com, December 11. http://edumorphology.com/2013/12/unbundling-higher-education-a-doubly-updated-framework/.

- Swartz, R., M. Ivancheva, L. Czerniewicz, and N. P. Morris. 2019. “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Dilemmas Regarding the Purpose of Public Universities in South Africa.” Higher Education 77 (4): 567–583. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0291-9.

- Swinnerton, B., M. Ivancheva, T. Coop, C. Perrotta, N. P. Morris, R. Swartz, L. Czerniewicz, A. Cliff, and S. Walji. 2018. “The Unbundled University: Researching Emerging Models in an Unequal Landscape. Preliminary Findings from Fieldwork in South Africa.” In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Networked Learning 2018, edited by M. Bajić, N. B. Dohn, M. de Laat, P. Jandrić, and T. Ryberg, 218–226. Zagreb, Croatia: Networked Learning.

- Tomlinson, M. 2018. “Conceptions of the Value of Higher Education in a Measured Market.” Higher Education 75 (4): 711–727. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0165-6.

- Trowler, P., and P. Knight. 2000. “Coming to Know in Higher Education: Theorising Faculty Entry to New Work Contexts.” Higher Education Research and Development 19 (1): 27–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360050020453.

- Walker, M. 2012. “Universities and a Human Development Ethics: A Capabilities Approach to Curriculum.” European Journal of Education 47 (3): 448–461. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2012.01537.x.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.