ABSTRACT

International students are a key demographic in UK higher education, yet there is limited literature dedicated to pedagogies for and with international students. We undertook a systematic literature review of journal articles from 2013 to 2019 which presented empirical evidence on specific pedagogic practices relating to international students in the UK. We identified 49 articles matching our selection criteria and analysed their aims, methods, findings and discursive framings of international students. Our findings show a dispersed literature, with wide ranging practices and conclusions, prohibiting an effective evidence based synthesis. International students continue to be subtly framed as in deficit or passive, rarely as partners or knowledge agents. We propose future research can be more methodologically ambitious, offer richer pedagogic detail to facilitate transferability and replication of teaching practices, and build in positive framings of international students.

Introduction

International student mobility increases annually, with over 4 million tertiary students travelling abroad in 2018 (Organization of Economic and Cultural Development Citation2019). The UK is the second global destination, hosting over 300,000 non-EU students in 2017/18 (Higher Education Statistics Authority Citation2019), constituting 14% of the total higher education (HE) student population. International students contribute £25.8 billion annually to the UK economy (Universities UK Citation2017). They are also valued for ‘offering a window on the world’, enhancing HE quality by facilitating internationalisation (Lomer Citation2017). Yet, while there is considerable academic interest in international student mobility, limited critical research specifically focuses on practical pedagogies with international students (Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2015).

Much recent research focuses on challenges experienced by international students and staff. For example, international students are often described as lacking the language and academic skills required for British academic life (Lomer Citation2017). Their silence is misunderstood as critical thinking and participation failures (Marlina Citation2009; Song and McCarthy Citation2018). Intercultural tensions with home students are well-documented, particularly during group work and seminar discussions (Straker Citation2016). Perceived cultural and academic differences also shape learning relationships, given many international students perceive discriminatory language and bias from their classmates (Heliot, Mittelmeier, and Rienties Citation2019) and lecturers (Rhoden Citation2019). Thus, one frequent narrative depicts international students, particularly non-EU and East Asian students, as a ‘necessary evil’: perceived as essential economic contributors, but simultaneously net educational drains in the classroom. Taken together, international students have been popularly described as ‘cash cows’ who lower educational standards (Lomer Citation2017).

These perceptions likely shape pedagogic practices in HE through deficit narratives which imply students should ‘assimilate’ to traditional (British) pedagogic practices (Ploner Citation2017). International students, particularly those from China, are frequently framed as passive (Karram Citation2013), unparticipative (Straker Citation2016), and uncritical (Song Citation2016). Lecturers have stereotyped many international students as rote learners who are incapable or unwilling to learn from collaborative or creative pedagogies (Turner Citation2013). Yet, in the literature and common discourse, international students are rarely critically conceptualised as complex knowledge agents and partners in pedagogy (Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2015). This has led to calls to acknowledge that ‘different is not deficient’ (Heng Citation2018) and recognise the complexity and diversity of international students’ prior experiences (Wu Citation2015).

Looking beyond the deficit model implies re-imagining fundamental pedagogic practices (Jenkins and Wingate Citation2015), conceptualising teaching as relational, equitable, and inclusive. Individual academics frequently adopt inclusive, ethical, and sustainable pedagogies in their classrooms. However, there is a lack of systematic evidence across the sector for understanding how lecturers have pedagogically responded to these concerns. Although the UK produces the most publications about internationalisation and international students (Kuzhabekova, Hendel, and Chapman Citation2015), the link to pedagogy remains fuzzy, particularly regarding transferable and ethical practices between lecturers or institutions. For example, it remains uncertain how lecturers have internationalised academic content, incorporated new classroom technologies, or developed culturally diverse pedagogic tools when working with international cohorts.

These issues are particularly concerning in the context of COVID-19 and global reluctance to travel, resulting in an increasing reliance on online or flexible teaching models. The UK must demonstrate the value of its teaching approaches to remain internationally competitive and its HE system financially viable. For example, our recent study with education agents (Yang et al. Citation2020) indicates international Chinese students and their families are concerned about the quality of teaching if delivery is online. Substantive pedagogic research on innovative approaches that explicitly include international students offers a way to do this, particularly in reflection of associated ethical tensions (Lomer and Mittelmeier Citation2020).

This study addresses these concerns by reporting on a systematic literature review of recent research specifically focusing on pedagogies with international students. We aim to synthesise empirical understandings of internationalisation in practice through the research question:

What evidence-based pedagogic practices with international students are highlighted in UK higher education literature?

Methodology

The systematic review process

We undertook a systematic literature review of pedagogic practices with international students in UK HE, informed by the PRISMA checklist (Moher et al. Citation2009). To identify pedagogic practices, our keywords included: pedagogy; classroom; teaching; curriculum; or assessment. These were used in a Boolean ‘and’ combination with ‘UK’ and ‘higher education’. These search terms were applied in our institutional library search, ProQuest, Web of Science, British Education Index and archives of major publishing companies (SAGE, Elsevier, Emerald, Springer, and Taylor & Francis).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

summarises the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to our search. A wide range of sources were identified in the initial searches from other countries, but this was outside our scope, as pedagogies vary widely by national context and degree of internationalisation. A multinational comparison offers potential for further research.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for systematic literature review.

We limited our search to taught units in degree-level HE settings, as pedagogic practices and purposes vary widely for programmes such as pre-sessional or in-sessional language courses, extracurricular activities, or informal learning programmes.

Finally, the key phrase ‘international students’ was used. We considered a wider range of terms related to internationalisation (e.g. ‘intercultural learning’), but search strategy testing revealed this did not identify new papers for inclusion, generated more theoretical results and did not necessarily relate to the classroom presence of international students, which was a key interest for this project.

We focused on peer-reviewed journal articles to synthesise evidence-based pedagogic practices in internationalised HE taught course units. Our review includes only articles with some form of empirical data. Conceptual explorations were excluded. We also purposefully excluded research about students’ experiences, unless connected to a specific classroom pedagogy.

Grey literature was originally included in our design, and more diverse samples may be present in published book chapters. However, library closures due to COVID-19 made access to books challenging, and grey literature was often hidden or challenging to identify. For the purposes of this paper, we opted to focus specifically on journals.

We reviewed all titles for relevance, applied exclusion criteria, and retained 1216 articles for further review of the abstracts to see whether a specific pedagogic practice was mentioned, and confirmed that part of the empirical data was collected in the UK. The full text of remaining articles was then reviewed to confirm our inclusion. We established no quality criteria, other than publication in peer-reviewed journals. We also set no defining criteria for international students, accepting the authors’ definitions (or lack thereof) as a key datapoint.

We initially planned to examine only those articles that described an innovation or development in teaching practices. However, notions of innovation in HE pedagogy are highly contested. A practice may be established in one discipline, but innovative in another. Further, much of the literature that relates international students to pedagogy examines established or traditional practices. We decided therefore not to impose an external or generalised criteria as to the ‘innovative-ness’ of the practices described and encompass both ‘new’ and ‘established’ practices. We do not differentiate between these in our analysis.

We also found we needed to relax the criteria around international students. Our initial aim was to examine pedagogies ‘for and with international students’, implying particular practices would be closely related to student demographics. We found very few articles met this criteria. Instead, we examined all papers which explicitly considered international students at all in their design, evaluation, or rationale. We anticipate that some papers which match our aims might be excluded by this criteria and welcome contact from such authors.

The search was limited to papers published between 2013 and 2019. This starting date was purposefully chosen as 2013 demarcates the beginning of the current international HE policy period, with the publication of the UK’s first International Education Strategy. Patterns of international student recruitment being shaped in part by policy (Lomer Citation2018), we expected to see intensification of pedagogic development relating to international students during this period.

Altogether, 49 studies fit our established criteria for analysis, which is listed in our findings ().

Table 2. Pedagogic practices investigated in included literatures.Table Footnotea

Analysis

Included studies were read by both researchers. Afterwards, papers were split between the researchers for inclusion in a data extraction template, which included: pedagogic focus, research context, methods, participants included, theoretical frameworks, and key findings. This template formed a basis for numerically exploring themes across the papers and compiling evidence for our findings.

Originally our intent was to synthesise findings about particular pedagogies to make concrete recommendations for practitioners, but as we detail below, this has proved impossible. Instead, qualitative analysis was undertaken to explore representations of international students in the literature sample. We adopted a Foucauldian-based discourse analysis approach (Foucault Citation1977), with attention given to dominant themes and key linguistic features (Fairclough Citation2013). We treated the sample of 49 articles as a linguistic corpus and further sampled all extracts of text directly referring to ‘international students’. This generated 622 extracts (excluding references). Using NVivo to facilitate the qualitative analysis (Bazeley and Jackson Citation2013), we coded these extracts simultaneously to en vivo codes based on keywords (particularly adjectives and verbs) associated with ‘international students’. This generated 17 codes based on keywords such as ‘ability’, ‘active’, ‘lack’, and ‘passive’, which formed the basis for the discursive analysis reported in the final section of the results.

Results

Academic disciplines and pedagogies in included papers

Our initial intention was to synthesise relevant research to build evidence-based and actionable recommendations for practice. This proved challenging on review of the 49 included studies, as there was a wide range of disparate approaches, limiting potential for synthesis. These are displayed in .

The most researched category pedagogic practice was group work, featured in 13 studies. 11 studies used student-centred approaches, nine explored assessment, nine looked at different ways of enhancing teaching through technology, seven explored different aspects of academic literacy, three included placements or work-based learning, two explored internationalising the curriculum, two explored work-based learning, and a further five examined isolated pedagogic approaches. Given the extreme dispersal of work across multiple pedagogies, it was impossible to synthesise evidence for individual pedagogies across different projects and contexts. Even where a similar pedagogic practice is referenced, these are not necessarily conceptualised in the same way, used with a similar theoretical framework, or presented with sufficient detail on implementation to enable comparison.

We expected much of this literature would aim to enable the transfer of findings to other disciplines, institutions or contexts. As such, a ‘thick description’ of the pedagogic practice, its implementation and course design would be a prerequisite. However, 18 of the studies (37%) lacked a ‘thick description’ about the teaching practices and classroom structures, so as to make the pedagogies replicable. Those that did include sufficient pedagogic detail often inversely lacked research methodology details (as described in the next section). This highlights how publication practices around standard word limitations often create a significant barrier to the inclusion of such essential details for pedagogic research. One way forward would be for pedagogic-focused journals to allow the submission of extended pieces, appendices or digital supplementary materials.

Research designs

Methodologies and research designs were evaluated to provide an overview of the quality of current empirical knowledge about pedagogies with international students. This proved a significant challenge, as the quality of reporting was often limited. In particular, not all articles included key information about research designs or contexts, such as number of participants or discipline. As such, one concern for the field is reconciling the scholarship of teaching and learning with standards of high quality empirical research.

The vast majority were single site case studies (n = 44, 90%), often taking place within the researchers’ own teaching practices. There were few cross-disciplinary studies (n = 6, 12%) and only three (6%) cross-institutional designs. Although we recognise pedagogies are often contextual, this relative immaturity of the field limits the transferability of findings for other lecturers.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting a high percentage of studies (n = 36, 73%) adopted mixed methods approaches, demonstrating complexity of analyses undertaken through triangulation. Several studies also embedded reflective, iterative approaches in which previous empirical research data (collected in the literature or from previous cohorts by the researcher) informed pedagogic practices.

Action research was a popular approach in the sample (n = 10, 20%). These papers typically documented several iterations of a pedagogic practice, with data collected at various stages. Other studies described their approach as a ‘longitudinal case study’ (n = 2, 4%). The incorporation of text analysis, particularly of student work (e.g. reflections, dissertation chapters, plagiarism reports, or feedback provided to students) was likewise a popular approach (n = 12, 25%). Several studies also adopted broadly ethnographic or autoethnographic approaches (n = 3, 6%). Taken together, this shows most of the research on this topic has been conducted in naturalistic settings in reflection of researchers’ own teaching practices.

The most common data collection method used was questionnaires (n = 25, 51%). The next most common research methods were interviews (n = 18, 38%), focus groups (n = 12, 24%) and observations (n = 8, 16%). All were commonly triangulated with other data sources and only rarely used as the sole method. Other research methods used more rarely included collecting data in workshops with students or staff and partnership research with students as researchers.

Taken together, this shows the methodological approaches taken by these studies were highly variable and often operated within the researchers’ own teaching domain. Nevertheless, methodological innovation was promising, particularly in the volume of mixed methods approaches and focus on triangulation of various data sources.

Participants

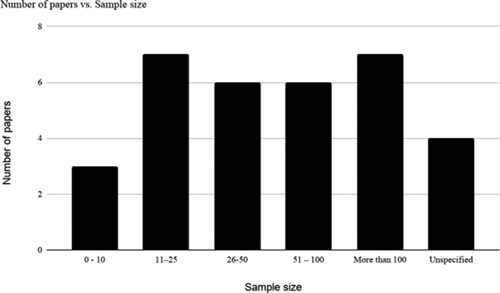

In this section, we discuss the sample sizes and characteristics of the participants involved in the included studies. A wide range of sample sizes were incorporated across the studies as demonstrated in . Notably, nine studies (18%) did not specify a sample size.

In most cases, the sample size adopted was dependent on the data collection method. However, we did find examples of sample sizes that were inappropriate to the analysis methods, particularly for quantitative research. For example, one paper used linear regression analysis with six variables on questionnaire data from only 13 participants. While other questionnaire sample sizes were small, many were used with content and thematic analysis, suggesting (though this was rarely explicitly identified) the surveys were open-ended in nature. Sample sizes for interviews were predictably and appropriately small, between five and 24. Nonetheless, we suggest there is scope for future research based on larger scale classroom observations.

Most studies (n = 24, 49%) specifically focused on postgraduate taught units, while 13 (26%) articles focused on undergraduate units, and 9 (18%) combined undergraduates and postgraduates in the sample. Two papers (4%) did not specify a study level. This broadly reflects the numerical distribution of international students across levels of study (HESA Citation2019). It does suggest, however, that there may be a comparative dearth of knowledge in undergraduate contexts, especially in under-represented subjects.

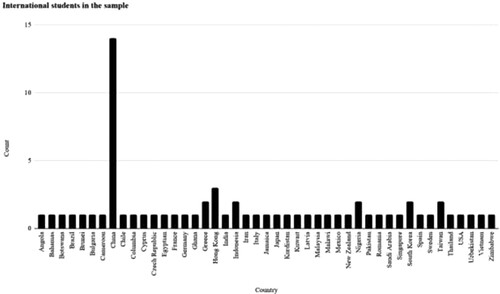

Given our inclusion criteria heavily emphasised the key phrase ‘international students’, it was expected that articles would include international students in their sample. outlines the range and frequencies of nationalities included as participants, as it was reported (and if it was reported) by authors. Where participant numbers were not included, the nationality reported appears in the chart above as ‘0’. This highlights overall the common nationalities included in the studies on pedagogies with international students in the UK.

Figure 2. Nationality of international student participants by count of articles mentioned in the sample.

Only seven nationalities were mentioned in more than one paper (China, Greece, Hong Kong, Nigeria, South Korea, Indonesia and Taiwan). This means there is a discrepancy between the key sending countries for the UK, of which the top five are China, India, Hong Kong, USA, and Malaysia (Higher Education Statistics Authority Citation2019), and those represented in the literature.

Other articles included descriptions that were of broad regional, continental or highly aggregated in nature. For example, students were broadly referred to as: ‘European’, ‘EU’, ‘Other European countries’, ‘Eastern Europe’, ‘African’, ‘Middle East and Africa’, ‘South and East Asia’, and ‘Asia’. The lack of conceptual clarity in the use and significance of these descriptions makes synthesis across the literature challenging. For example, European may commonly be used as a synonym for the EU, but not all European countries are EU members. Similarly, which countries are included in ‘Eastern Europe’ is unclear. There is also a concerning lack of detail in the application of continent-level descriptors such as ‘Asian’ and ‘African’ that fail to engage with the continents’ national, ethnic, religious, linguistic, historical and educational diversities. As a recommendation, we suggest that researchers use national-level descriptors as a minimum for describing their international student participants. As a provocation, we encourage researchers to consider how characteristics beyond national citizenship (e.g. family background, prior educational experiences, race, social class, religion, and membership in minority ethnic groups), might impact upon international students’ learning.

At the same time, over half of the articles (n = 28, 57%) did not specify at all where students were from or broadly labelled them ‘international students’. These articles typically identified international students as present in the classroom and sample, but did not engage with their cultural, linguistic, or educational backgrounds. Instead they often referred to ‘diverse nationalities’ or ‘international students from 8 different countries’. This homogenisation of the category ‘international students’ could arguably constitute ‘othering’, whereby international students’ are constructed as a single group with common experience that differentiate them from home students (Lomer and Mittelmeier Citation2020). This was astutely observed by the authors of one paper, where they note: ‘The category “international” is problematic, assimilating different as well as differentiating similar identities, and to target the group would produce it as a reality’ (Waldron Citation2017, 14).

Even when participants’ nationalities or backgrounds were outlined, there was rarely engagement with cultural differences in their experiences. For example, thirteen papers (27%) reported their sample of international students was exclusively or mostly of Chinese nationality or ‘East Asian’ background. However, only three of these papers specifically identified Chinese or ‘Asian’ students in their title or framing. A further six studies included staff or lecturers, but offered no further demographic details or information about their education or backgrounds. This may be impeded by word count limitations in many journals, yet we note increasing literature on staff biographies and trajectories (Morley et al. Citation2018) and suggest there may be a link to the pedagogic internationalisation.

Data collection contexts

In review of the context descriptions in the included articles, the majority focused in the business field (aggregated across marketing, accounting, finance, and business students) (n = 26, 53%). This is perhaps unsurprising, considering business programmes host the majority of international students in the UK (HESA Citation2019). The next most common disciplines were language studies or TESOL (n = 5, 10%) and education (n = 4, 8%), with isolated instances from engineering, linguistics, law, and medicine. Three studies did not identify a disciplinary context, which is problematic considering potential transferability. There has also been limited research in many fields which recruit significant numbers of international students, including engineering, social studies, art and design, or biological and physical sciences (HESA Citation2019).

As noted previously, we found limited cross-disciplinary studies (n = 6, 12%), cross-institutional (n = 3, 6%) or multi-national (n = 1, 2%) designs. The majority were case studies in a single location or classroom, typically (although not always explicitly) in the researchers’ own classrooms. While this is common of the literature in the scholarship of learning and teaching, it does constitute a serious limitation in evaluating the transferability of specific practices. We argue this might imply a sense of individualism in teaching approaches, that pedagogic practices depend on personal experiences, context and intuition, rather than on an established base of evidence. It is troubling that this positionality is not consistently made explicit, both for the purposes of transparency and reflexivity, and for lending authenticity to the authors’ first-hand insights.

Despite this highly contextual focus, 24 articles (49%) provided no information about the institution where the research took place. Eight (16%) identified the institution by name in the text. Other studies reported the institutional categorisation: post-1992 (n = 8, 16%) or Russell Group (n = 7, 14%). Some reported in terms of size (n = 2, 4%), (e.g. ‘mid-sized UK university’ with ‘approximately 16,000 students’). One described the context as a ‘well-known higher education business institution’, while another included mention of its location as ‘city-based’ (presumably in juxtaposition with campus-based institutions). As the range of different descriptors again makes synthesis and comparison difficult, we cannot assert that any of these factors have any necessary relationship with pedagogy, but a simple recommendation is that pedagogic research should describe the institutional context in terms of size, subject specialisation, and sector group at a minimum so that these potential relationships can be later explored through comparative research.

In terms of institutional location, often limited information was provided. 23 articles (47%) referred only to the UK and gave no further geographical information. Fourteen articles (29%) specifically situated their context in England, with some specifying vaguely ‘the South’ and or ‘the North’. Four studies (8%) were conducted in Scotland and two (4%) in Wales. None of the selected studies noted taking place in Northern Ireland. The absence of further geographical details implies these have no bearing on the implementation or outcomes of the pedagogic interventions, an empirical question which bears future investigation.

The lack of geographic detail can often be attributed to the challenge of anonymising institutions given comparatively small numbers in most geographical locations. Given that context impacts pedagogy and practices (Englund, Olofsson, and Price Citation2018), it may be that the anonymity for the purposes of ethical compliance creates an opportunity cost for evaluating transferability. One study provided further relevant details as follows: ‘a region of the UK with relatively low ethnic and cultural diversity reflected in the student make-up at the university’ (Cotton, George, and Joyner Citation2013, 274). This is an excellent model for providing relevant contextual detail without compromising the institutional anonymity.

Representations of international students

In addition to descriptive analyses of the included studies, we conducted a qualitative inductive analysis to explore how the literature on pedagogic practices in the UK represents or constructs international students. This was an important question, given frequent criticisms made regarding a dominant deficit narrative in the literature (Heng Citation2018). As outlined in our introduction, this narrative frequently positions international students as ‘lacking’ skills, language, or other characteristics intrinsic to academic success. We contend any pedagogic intervention that starts from a premise of deficit, even where intentions are sincerely oriented towards enhancing achievement or engagement, necessarily positions international students as subaltern, generating destructive and marginalising representations.

Several studies (Foster and Carver Citation2018; Lahlafi and Rushton Citation2015; McKay, O’Neill, and Petrakieva Citation2018; Simpson Citation2017; Divan, Bowman, and Seabourne Citation2015) explicitly identified deficit narratives as a concern, critiquing this perspective with reference to their pedagogic design and dealing sensitively with it in discussion. However, this conversely implies the majority in our sample did not explicitly discuss the deficit narrative, suggesting limited engagement with more critical perspectives on curriculum and pedagogic internationalisation. However, where the deficit narrative does appear, it is much more subtle than in the literature 20 years ago.

Our first observation was there was an overwhelming tendency to describe international students as a homogenous group. This was particularly evident in the methodology sections where, as discussed above, there was often no breakdown of further characteristics provided. By this, we do not necessarily mean to suggest a nationality-based breakdown (Ely Citation2018) is always of significant value, but reflecting on multiple axes of diversity. Omitting more nuanced descriptions about student cohorts, however briefly, implies the salient characteristics from the perspective of the teacher and researcher is simply their difference: they are ‘international’. This differentiation has been described as a process of ‘othering’, drawing on the work of Edward Said (Citation1979) regarding the construction of the ‘Orient’ in the Western literary canon. We have set out to examine literature on pedagogy relating specifically to ‘international students’, so in a sense intentionally targeted articles more prone to ‘othering’ international students. However, what we hoped we would find was complexity and nuance in the pedagogic treatment of international students, at odds with institutional and often financially driven narratives that frame international students as objects of distinction and economic resource. We did not, in general, find such complexity in these articles.

There were in some cases interesting discrepancies in the definitions used for ‘international students’. For most, this was taken for granted but not further explained. However, some explored the issue in more depth, and below we quote Morgan (Citation2017, 4–5) to illustrate:

Participants were recruited from allied healthcare students who, until the age of 18, undertook their formative education in another country (emphasis ours). The selection of these criteria was deemed apposite as international students may also be defined by their differential fee-paying status. However, using this latter criterion would possibly include students who are ostensibly ‘international’ but who may have been resident within the UK for their schooling. It would also have precluded students who have acquired asylum status within the UK. As the fee-paying issue for European/some international students who study in Wales can be quite complicated, the schooling/residency categorisation was adopted.

This shows the category of ‘international students’ has here been reflexively interrogated with reference to the aims and objectives of the research. Spencer-Oatey and Dauber (Citation2017, 7) gave a similarly nuanced definition, exploring the implications of fee status and relative use of EU vs EEA in terms of politics and culture. Harwood and Petrić (Citation2019, 151) use a standardised OECD definition as those ‘who have crossed borders for this purpose of study’. Each of these is potentially a valid definition, but it is noticeable that few articles in the sample adopt a reflexive approach to defining international students or contemplate the overlap or exclusions generated by adopting particular criteria. Most articles lacked even an awareness that international students could be defined in multiple ways.

In some cases, international students are further reified or objectified in references to ‘internationals’ (Frimberger Citation2016; Waldron Citation2017). By eliding the key descriptor of ‘student’, this nominalisation turns the adjective (international) which normally modifies the key noun (student) into the noun. This changes how we understand the individual: in the construction ‘an international student’, an interlocutor infers ‘a student (primary characteristic) who is international (secondary characteristic, albeit placed first for grammatical purposes)’. But the term ‘internationals’ removes the identity of ‘student’ and replaces it only with their difference.

We also found frequent use of terms and concepts reflecting deficit narratives. Descriptions of ‘barriers, challenges, problems, stresses, needs, struggles’ of international students were more frequent than descriptions as ‘capable, able, coping, managing’. This was confirmed by further keyword searches enabled by NVivo, with a range of synonyms established inductively through close reading of the text. Here, we deliberately quote from authors out of context, not to paint the authors as intentionally promoting or consciously subscribing to the deficit discourse, but to highlight the insidiousness of negative language portraying international students. To show good faith, we include one of our own papers in this critique as well.

For example, Chew, Snee, and Price (Citation2016, 250) describe a challenge to their research process with reference to ‘cultural barriers and participated (sic) international students are camera-shy’. Similarly, Cowley, Sun, and Smith (Citation2017) discuss the ‘range of challenges and adjustment issues’ international students are likely to experience. Heron (Citation2019, 2) concludes, ‘studies on international students’ experiences of higher education (HE) have identified three main challenges of seminar participation’. Kraal (Citation2017, 8) states: ‘Such student diversity in a class presents special problems as the international students lack knowledge of local issues and institutions’. These broad generalisations do not account for variations in students’ educational experiences or personal histories. For example, some postgraduate international students may have completed their previous degree in the UK or another international destination. There is a recurrent assumption that international students, simply by virtue of their nationality, have predictably ‘unique needs’ (Scally and Jiang Citation2019). For example, ‘any initial writing development programme should be adapted to accommodate the differing needs of the UK and international students within the cohort’ (Divan, Bowman, and Seabourne Citation2015).

‘Lack’ was a particularly prevalent word associated with international students, who are described as lacking: ‘social integration (with home students)’ (Cockrill Citation2017; Cotton, George, and Joyner Citation2013), ‘the culture-specific knowledge to follow conversations’ (ibid), ‘participation’ (Cotton, George, and Joyner Citation2013), ‘experience with academic writing in the UK HE tradition’ (Divan, Bowman, and Seabourne Citation2015), ‘knowledge of local issues and institutions’ (Kraal Citation2017), and ‘the confidence to engage with opportunities to ask questions’ (Turner Citation2015), amongst others.

In some cases, the ‘challenges’ derive from the data offered by the students as research participants, but often these references are made in the framing of the research context, significance, and methodological approach. This is often subtle and in the context of justifying the pedagogy in focus as innovation or change to existing practice. However, it suggests a framing of international students’ academic experiences as necessarily ‘challenging’ and ‘stressful’.

It was less frequent to see students described as ‘capable’ (McKay, O’Neill, and Petrakieva Citation2018), or ‘able’ – and in one instance the deficit narrative was reinforced by the latter: ‘international students from Europe were more able to work and network with host students than Confucian students’ (Rienties, Héliot, and Jindal-Snape Citation2013). Although this quote is taken from a description of the data, the research was premised on a social learning network reflecting students’ social patterns, not their ability. Such nuance is important for future research to avoid reinforcing deficit representations of international students.

Students are often constructed as passive as in the following example: ‘international students may be inhibited or even intimidated by their new learning environment’ (Cowley, Sun, and Smith Citation2017). This positions students’ behaviour as determined by their environment, rather than framing them as active agents. While obviously intended to provide an empathic insight, such framings fall into the trap described above by Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo (Citation2015) in not positioning international students as knowledge agents. This could be positively re-framed as ‘depending on their confidence and knowledge, international students may assess the learning environment as hostile and decide to disengage’. This construction re-positions students as active and intentional in their practices. Notable exceptions are those that explicitly positioned students as partners (Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Brown Citation2019). Several articles likewise referred to their pedagogic practices as ‘enabling’ international students’ (Chew, Snee, and Price Citation2016; Robson, Forster, and Powell Citation2016; Bamford, Djebbour, and Pollard Citation2015; Deeley and Bovill Citation2017; Ely Citation2018; Green Citation2019; Scoles, Huxham, and Mcarthur Citation2013; Scott, Thompson, and Penaluna Citation2015; Sloan et al. Citation2014).

Finally, there is a false inference frequently made or at least unchallenged by many of these articles that, as Cockrill (Citation2017, 64) puts it, ‘internationalisation of the student body and diversity of viewpoints are a cornerstone of a global education’. This implies students of different nationality necessarily implies different viewpoints, though how a person’s nationality should determine their opinion is never adequately explained.

Again, these critiques are not intended to assert bad faith or negative stereotyping on the part of the authors. Indeed, in examining one of our research team’s previous articles included in the sample (Lomer and Anthony-Okeke Citation2019) there are discursive traces of the deficit narrative. Rather, our intention is to problematise how pedagogic literature on internationalisation represents international students in the course of describing and justifying teaching practices, even with the best of intentions. This may also be a product of the rhetorical demands of publication; often authors are expected to frame pedagogic interventions as responses to a ‘need’ or a ‘lack’ to highlight its wider significance. It is clearly difficult to extricate oneself discursively and, therefore, conceptually from the ‘othering’ of international students and the deficit narrative about their competencies or skills. For projects invested in ethical and emancipatory HE pedagogies, this poses a real challenge: how can we talk and think differently about international students? The study of international students in HE inherently involves constructing ontological categories of student populations, but this poses a real ethical paradox for researchers: how do we authentically depict individual and collective experiences without homogenising or reifying often marginalised social groups? As a first step, there must be nuance in any analysis, recognising a plurality of different groups of international students, intersectional dynamics and different configurations of privilege.

Discussion

This systematic literature review has mapped recent research related to pedagogies with international students in the UK. In outlining the numerous challenges facing the research on this topic, we show that pedagogies of internationalisation is not yet an established field of research, although we hope it will continue to develop into one. A wide range of research focuses on international students’ general experiences of academic and social transitions (Kuzhabekova, Hendel, and Chapman Citation2015). However, as demonstrated by our systematic review, only a limited number of these studies focus on specific classroom pedagogies. Therefore, a consideration for future research is to pivot away from descriptive research about general experiences and, instead, develop more in-depth understandings of evidence-based pedagogies with international students. To support this endeavor, we outline in this section several key areas of research maturation needed to develop a distinctive field of pedagogies with international students.

In terms of methodologies adopted, the majority of work on this topic presently uses small scale, exploratory, and single-site case studies. This leaves great scope for methodological innovation and enhancement, particularly cross-institutional, cross-contextual, and multi-site research. At present, research remains opportunistic, based primarily on easily accessible data within researchers’ own contexts. Therefore, we suggest increased collaboration between researchers in different institutions and replication or triangulation of findings by investigating similar pedagogies in different institutional and disciplinary contexts. Similarly, longitudinal research or research collecting data from multiple iterations of courses would support deeper analysis of pedagogic innovations.

The hyper-contextuality of research related to pedagogies with international students also outlines significant concerns about the transferability of findings to other contexts. This confirms prior critiques that knowledge is limited about the specific pedagogies that can effectively and ethically support international students (Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2015). These concerns were exacerbated in our review by the details commonly missing about the environment where the research was undertaken. For example, many of the studies included in our review did not adequately describe the institutional or classroom context or were missing essential details about their participants. For this reason, we suggest future research should include a ‘thick description’ (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985) of the learning context and explicitly written implications for practice. However, this requires support of pedagogic-focused journals, as such descriptions are often limited by word count allowances.

Many of the papers we reviewed were uncritical in the framing and categorisation of international students, often through a binary lens – either ‘international student’ or ‘not international student’ – despite recent problemisations of this approach (Jones Citation2017). Similarly, we saw limited engagement with the diversity present within international student cohorts, particularly regarding their unique cultures, histories, and prior experiences. This was often portrayed by ‘othering’ international students as a collective group, categorising students by region without justification or consideration of the presumed relationship between geography and culture, or, in the cases where nationality was provided, not authentically engaging with cultural impacts on experiences. In this regard, there was a tendency to homogenise international students’ experiences and ignore the intersectionalities which would otherwise be applied to other groups of (home) students, such as the intersectional impacts of race, gender, or socioeconomic background on pedagogic experiences. Nonetheless, research about international students beyond pedagogy recognises the multidimensionality of their experiences (e.g. Madriaga and McCaig Citation2019). As such, we suggest future research more critically evaluate how international students are labelled or categorised, with an alertness to the nuances of pedagogic framings of international students as ‘others’ and intersectionalities of their experiences.

Recent critiques have been made about the pervasive deficit narrative held by many university staff about international students (Heng Citation2018; Ploner Citation2017; Wu Citation2015). Our findings have expanded this notion by outlining that deficit narratives are similarly pervasive in the research about pedagogies with international students. This included consistent framings of challenges or struggles and depictions of skills, competencies, or experiences international students are perceived to lack. While we have no doubts about the inclusive intentions of authors, this highlights the difficulties of disentangling oneself from such ubiquitous ‘othering’ of international students, including in our own previous work. Therefore, we urge scholars to continue to engage with developing critical voices in the field (see, for example: Harrison Citation2015; Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2015; Song and McCarthy Citation2018; Zepke Citation2014) and critically reflect on the language and assumptions used to portray international students’ experiences.

Conclusion

Our analysis of recent research related to pedagogies with international students in the UK has provided key areas of critical development for future research on this topic. We cannot identify empirical evidence that intense contemporary international student recruitment has re-shaped pedagogic practices in the UK. Rather it appears that an assimilationist model predominates, wherein international students are still expected to ‘adapt’ fully to the assumed inherently superior British model of teaching and learning in HE. These entrenched pedagogic practices contribute to the epistemic exclusion of international students (Hayes Citation2019).

However, we recognise several limitations to our work. First, our inclusion criteria focused on research explicitly mentioning international students. We note some studies may have been missed by our inclusion and exclusion criteria if they did not explicitly mention international students or evaluate a specific pedagogy. Such exclusions may nonetheless offer valuable insight for this field and we welcome contact form authors with relevant papers. Second, we recognise other publication types beyond journal articles, such as book chapters or reports, may offer more variation in their findings or framings. However, this research was impacted by COVID-19 and subsequent loss of access to many printed materials through library closures. Third, we specifically narrowed our research to the UK to focus on pedagogy research from a particular national perspective, but suggest a widening of this search to other global contexts in the future.

Nonetheless, this systematic review has developed a blueprint for the future of the field of pedagogies with international students. Adopting this systematic literature review appears to be a relatively innovative approach in HE pedagogies, and offers the potential to consolidate and progress the field. This review also offers researchers currently working in this area concrete suggestions for developing their work, while simultaneously offering suggested innovations to the journals that publish them.

In summary, methodological innovation and greater ambition in research designs are essential. Future research requires thicker descriptions and critical engagement with the impact of the context of pedagogies. Journal editors and reviewers need to be attentive to a balance of methodological rigour and sufficient detail of pedagogic practices. The field also presently lacks criticality of how international students are represented, in particular around the discourse of deficit, with greater attention needed on the complexities of their experiences. We hope that authors and reviewers can encourage each other to frame international students in light of their primary identity as students with agency, rather than in light of their differences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adelopo, Ismail, Joseph Asante, Eleanor Dart, and Ibrahim Rufai. 2017. “Learning Groups: The Effects of Group Diversity on the Quality of Group Reflection.” Accounting Education 26 (5-6): 553–575. doi:10.1080/09639284.2017.1327360.

- Baden, Denise, and Carole Parkes. 2013. “Experiential Learning: Inspiring the Business Leaders of Tomorrow.” International Journal of Management & Enterprise Development 32 (3): 295–308. doi:10.1108/02621711311318283.

- Bamford, Jan, Yaz Djebbour, and Lucie Pollard. 2015. “‘I’ll Do This No Matter If I Have to Fight the World!’ Resilience as a Learning Outcome in Urban Universities.” Journal for Multicultural Education 9 (3): 140–158. doi:10.1108/JME-05-2015-0013.

- Bazeley, Patricia, and Kristi Jackson. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. SAGE. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=Px8cJ3suqccC.

- Brown, Nicole. 2019. “Partnership in Learning: How Staff-Student Collaboration Can Innovate Teaching.” European Journal of Teacher Education 42 (5): 608–620. doi:10.1080/02619768.2019.1652905.

- Burns, Caroline, and Martin Foo. 2013. “How is Feedback Used? The International Student Response to a Formative Feedback Intervention.” The International Journal of Management Education 11 (3): 174–183. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S147281171300030X?casa_token=nFM8X_xb39wAAAAA:Ywwyml5YwK65oM5rjB1I9fK5WnZxDVFzRVAKXc2TuuOfjhVcavjDGgdtcNLdaqm4K1b6ZBJc5Q.

- Burrows, Karen, and Nick Wragg. 2013. “Introducing Enterprise – Research into the Practical Aspects of Introducing Innovative Enterprise Schemes as Extra Curricula Activities in Higher Education.” Higher Education, Skills and Work – Based Learning 3 (3): 168–179. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-07-2012-0028.

- Chew, Esyin. 2014. “‘To Listen or to Read?’ Audio or Written Assessment Feedback for International Students in the UK.” On the Horizon 22 (2): 127–135. doi:10.1108/OTH-07-2013-0026.

- Chew, Esyin, Helena Snee, and Trevor Price. 2016. “Enhancing International Postgraduates’ Learning Experience with Online Peer Assessment and Feedback Innovation.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 53 (3): 247–259. doi:10.1080/14703297.2014.937729.

- Cockrill, Antje. 2017. “For Their Own Good: Class Room Observations on the Social and Academic Integration of International and Domestic Students.” Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness 11 (2): 64–77.

- Cooley, S. J., J. Cumming, and M. J. G. Holland. 2015. “Developing the Model for Optimal Learning and Transfer (MOLT) Following an Evaluation of Outdoor Groupwork Skills Programmes.” European Journal. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/EJTD-06-2014-0046/full/html.

- Costley, Carol, and Abdulai Abukari. 2015. “The Impact of Work-Based Research Projects at Postgraduate Level.” Journal of Work-Applied Management 7 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1108/JWAM-10-2015-006.

- Cotton, D. R. E., R. George, and M. Joyner. 2013. “Interaction and Influence in Culturally Mixed Groups.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 50 (3): 272–283. doi:10.1080/14703297.2012.760773.

- Cowley, Paul, Sally Sun, and Martin Smith. 2017. “Enhancing International Students’ Engagement Via Social Media – A Case Study of Wechat and Chinese Students at a UK University.” INTED2017 Proceedings 1 (March): 7047–7057. doi:10.21125/inted.2017.1633.

- Deeley, Susan J., and Catherine Bovill. 2017. “Staff Student Partnership in Assessment: Enhancing Assessment Literacy Through Democratic Practices.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (3): 463–477. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1126551.

- Divan, Aysha, Marion Bowman, and Anna Seabourne. 2015. “Reducing Unintentional Plagiarism Amongst International Students in the Biological Sciences: An Embedded Academic Writing Development Programme.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 39 (3): 358–378. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2013.858674.

- Elliott, Carole Jane, and Michael Reynolds. 2014. “Participative Pedagogies, Group Work and the International Classroom: An Account of Students’ and Tutors’ Experiences.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (2): 307–320. doi:10.1080/03075079.2012.709492.

- Ellis, David. 2015. “Using Padlet to Increase Student Engagement in Lectures.” Proceedings of the European Conference on E-Learning, ECEL 2013: 195–198.

- Ely, Adrian V. 2018. “Experiential Learning in ‘Innovation for Sustainability’: An Evaluation of Teaching and Learning Activities (TLAs) in an International Masters Course.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 19 (7): 1204–1219. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-08-2017-0141.

- Englund, Claire, Anders D. Olofsson, and Linda Price. 2018. “The Influence of Sociocultural and Structural Contexts in Academic Change and Development in Higher Education.” Higher Education 76 (6): 1051–1069. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0254-1.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Routledge. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=nf7cAAAAQBAJ.

- Foster, Monika, and Mark Carver. 2018. “Explicit and Implicit Internationalisation: Exploring Perspectives on Internationalisation in a Business School with a Revised Internationalisation of the Curriculum Toolkit.” International Journal of Management Education 16 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2018.02.002.

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Vintage.

- Frimberger, Katja. 2016. “A Brechtian Theatre Pedagogy for Intercultural Education Research.” Language and Intercultural Communication 16 (2): 130–147. doi:10.1080/14708477.2015.1136639.

- Green, Wendy. 2019. “Engaging ‘Students as Partners’ in Global Learning: Some Possibilities and Provocations.” Journal of Studies in International Education 23 (1): 10–29. doi:10.1177/1028315318814266.

- Hardman, Jan. 2016. “Tutor–Student Interaction in Seminar Teaching: Implications for Professional Development.” Active Learning in Higher Education 17 (1): 63–76. doi:10.1177/1469787415616728.

- Harrison, Neil. 2015. “Practice, Problems and Power in ‘Internationalisation at Home’: Critical Reflections on Recent Research Evidence.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (4): 412–430.

- Harwood, Nigel, and Bojana Petrić. 2019. “Helping International Master’s Students Navigate Dissertation Supervision: Research-Informed Discussion and Awareness-Raising Activities.” McGill Journal of Medicine: MJM: An International Forum for the Advancement of Medical Sciences by Students 9 (1): 150–171. doi:10.32674/jis.v9i1.276.

- Hayes, Aneta. 2019. “‘We Loved It Because We Felt That We Existed There in the Classroom!’ International Students as Epistemic Equals Versus Double-Country Oppression.” Journal of Studies in International Education 23 (5): 554–571. doi:10.1177/1028315319826304.

- Heliot, Yingfei, Jenna Mittelmeier, and Bart Rienties. 2019. “Developing Learning Relationships in Intercultural and Multi-Disciplinary Environments: A Mixed Method Investigation of Management Students’ Experiences.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (11): 2356–2370.

- Heng, Tang T. 2018. “Different is Not Deficient: Contradicting Stereotypes of Chinese International Students in US Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1152466.

- Hennebry, Mairin Laura, and Kenneth Fordyce. 2018. “Cooperative Learning on an International Masters.” Higher Education Research and Development 37 (2): 270–284. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1359150.

- Heron, Marion. 2019. “Pedagogic Practices to Support International Students in Seminar Discussions.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (2): 266–279. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1512954.

- Higher Education Statistics Authority. 2019. “Higher Education Student Statistics.” https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/16-01-2020/sb255-higher-education-student-statistics.

- Jenkins, Jennifer, and Ursula Wingate. 2015. “Staff and Students Perceptions of English Language Policies and Practices in International Universities: A Case Study from the UK.” Higher Education Review 47 (2): 47–73.

- Jones, Elspeth. 2017. “Problematising and Reimagining the Notion of International Student Experience.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (5): 933–943. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1293880.

- Karram, Grace L. 2013. “International Students as Lucrative Markets or Vulnerable Populations: A Critical Discourse Analysis of National and Institutional Events in Four Nations.” Canadian and International Education. Education Canadienne et Internationale 42: 1.

- Kraal, Diane. 2017. “Legal Teaching Methods to Diverse Student Cohorts: A Comparison Between the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and New Zealand.” Cambridge Journal of Education 47 (3): 389–411. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2016.1190315.

- Kuzhabekova, Aliya, Darwin D. Hendel, and David W. Chapman. 2015. “Mapping Global Research on International Higher Education.” Research in Higher Education 56 (8): 861–882. https://idp.springer.com/authorize/casa?redirect_uri=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11162-015-9371-1&casa_token=VfB9qr5i3jQAAAAA:_LhNNVhNzys4fV7qqje3-hm9uMhi0hjA3RESoM7hCgH70AC1zhPSqk2HXznN71PjmJeYWzV4g7B82fgjVw.

- Lahlafi, Alison, and Diane Rushton. 2015. “Engaging International Students in Academic and Information Literacy.” New Library World 116 (5-6): 277–288. doi:10.1108/NLW-07-2014-0088.

- Leger, Lawrence A., and Kavita Sirichand. 2015. “Training in Literature Review and Associated Skills.” Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 7 (2): 258–274. doi:10.1108/JARHE-01-2014-0008.

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Lomer, Sylvie. 2017. Recruiting International Students in Higher Education Representations and Rationales in British Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lomer, Sylvie. 2018. “UK Policy Discourses and International Student Mobility: The Deterrence and Subjectification of International Students.” Globalisation, Societies and Education. doi:10.1080/14767724.2017.1414584.

- Lomer, Sylvie, and Loretta Anthony-Okeke. 2019. “Ethically Engaging International Students: Student Generated Material in an Active Blended Learning Model.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (5): 613–632. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1617264.

- Lomer, Sylvie, and Jenna Mittelmeier. 2020. “Ethical Challenges of Hosting International Chinese Students.” In UK Universities and ChinaMichael Natzler, 43–66. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute.

- Madge, Clare, Parvati Raghuram, and Patricia Noxolo. 2015. “Conceptualizing International Education: From International Student to International Study.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (6): 681–701.

- Madriaga, Manuel, and Colin McCaig. 2019. “How International Students of Colour Become Black: A Story of Whiteness in English Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1696300.

- Marlina, Roby. 2009. “I Don’t Talk or I Decide Not to Talk? Is It My Culture? International Students’ Experiences of Tutorial Participation.” International Journal of Educational Research 48 (4): 235–244. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2009.11.001.

- McKay, Jane, Deborah O’Neill, and Lina Petrakieva. 2018. “CAKES (Cultural Awareness and Knowledge Exchange Scheme): A Holistic and Inclusive Approach to Supporting International Students.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 42 (2): 276–288. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2016.1261092.

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and Prisma Group. 2009. “Reprint-Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” Physical Therapy 89 (9): 873–880. https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/89/9/873/2737590.

- Morgan, Gareth. 2017. “Allied Healthcare Undergraduate Education: International Students at the Clinical Interface.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 41 (3): 286. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2015.1100713.

- Morley, Louise, Nafsika Alexiadou, Stela Garaz, José González-monteagudo, Marius Taba, and Louise Morley. 2018. “Internationalisation and Migrant Academics: The Hidden Narratives of Mobility.” Higher Education 76: 537–554.

- Morris, Neil P., Bronwen Swinnerton, and Taryn Coop. 2019. “Lecture Recordings to Support Learning: A Contested Space Between Students and Teachers.” Computers & Education 140. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103604.

- Organization of Economic and Cultural Development. 2019. “Students – International Student Mobility – OECD Data.” https://data.oecd.org/students/international-student-mobility.htm.

- Pagano, Rosane, and Alberto Paucar-Caceres. 2013. “Using Systems Thinking to Evaluate Formative Feedback in UK Higher Education: The Case of Classroom Response Technology.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 50 (1): 94–103. doi:10.1080/14703297.2012.748332.

- Ploner, Josef. 2017. “Resilience, Moorings and International Student Mobilities–Exploring Biographical Narratives of Social Science Students in the UK.” Mobilities 12 (3): 425–444. doi:10.1080/17450101.2015.1087761.

- Rhoden, Maureen. 2019. “Internationalisation and Intercultural Engagement in UK Higher Education – Revisiting a Contested Terrain.” In International Research and Researchers Network Event. Society for Research in Higher Education.

- Richards, Kendall, and Nick Pilcher. 2014. “Contextualising Higher Education Assessment Task Words with an ‘Anti-Glossary’ Approach.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education: QSE 27 (5): 604–625. doi:10.1080/09518398.2013.805443.

- Rienties, Bart, and Yingfei Héliot. 2018. “Enhancing (in)formal Learning Ties in Interdisciplinary Management Courses: A Quasi-Experimental Social Network Study.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (3): 437–451. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1174986.

- Rienties, Bart, Ying Fei Héliot, and Divya Jindal-Snape. 2013. “Understanding Social Learning Relations of International Students in a Large Classroom Using Social Network Analysis.” Higher Education 66 (4): 489–504. doi:10.1007/s10734-013-9617-9.

- Robson, Fiona, Gillian Forster, and Lynne Powell. 2016. “Participatory Learning in Residential Weekends: Benefit or Barrier to Learning for the International Student?” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 53 (3): 274–284. doi:10.1080/14703297.2014.937731.

- Said, Edward W. 1979. Orientalism. Vintage. https://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/book_archive/196174216674_10154888789381675.pdf.

- Scally, Jayme, and Man Jiang. 2019. “‘I Wish I Knew How to Socialize with Native Speakers’: Supporting Authentic Linguistic and Cultural Experiences for Chinese TESOL Students in the UK.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 00 (00): 1–14. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2019.1688263.

- Scoles, Jenny, Mark Huxham, and Jan Mcarthur. 2013. “No Longer Exempt from Good Practice: Using Exemplars to Close the Feedback Gap for Exams.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (6): 631–645. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.674485.

- Scott, Jonathan, John L. Thompson, and Andy Penaluna. 2015. “Constructive Misalignment? Learning Outcomes and Effectiveness in Teamwork-Based Experiential Entrepreneurship Education Assessment.” http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/29929/1/Constructive%20misalignment.pdf.

- Shah, Syed Zulfiqar Ali. 2013. “The Use of Group Activities in Developing Personal Transferable Skills.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 50 (3): 297–307. doi:10.1080/14703297.2012.760778.

- Simpson, Colin. 2017. “Language, Relationships and Skills in Mixed-Nationality Active Learning Classrooms.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 611–622. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1049141.

- Slater, Stephanie, and Mayuko Inagawa. 2019. “Bridging Cultural Divides: Role Reversal as Pedagogy.” Journal of Teaching in International Business 30 (3): 269–308. doi:10.1080/08975930.2019.1698395.

- Sloan, Diane, Elizabeth Porter, Karen Robins, and Karen McCourt. 2014. “Using E-Learning to Support International Students’ Dissertation Preparation.” Education+Training 56 (2/3): 122–140. doi:10.1108/ET-10-2012-0103.

- Song, Xianlin. 2016. “‘Critical Thinking’ and Pedagogical Implications for Higher Education.” East Asia 33 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1007/s12140-015-9250-6.

- Song, Xianlin, and Greg McCarthy. 2018. “Governing Asian International Students: The Policy and Practice of Essentialising ‘Critical Thinking.” Globalisation, Societies and Education. doi:10.1080/14767724.2017.1413978.

- Spencer-Oatey, Helen, and Daniel Dauber. 2017. “The Gains and Pains of Mixed National Group Work at University.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38 (3): 219–236. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1134549.

- Straker, John. 2016. “International Student Participation in Higher Education: Changing the Focus from ‘International Students’ to Participation.” Journal of Studies in International Education 20 (4): 299–318. doi:10.1177/1028315316628992.

- Turner, Yvonne. 2013. “Pathologies of Silence? Reflecting on International Learner Identities Amidst the Classroom Chatter.” Cross-Cultural Teaching and Learning for Home and International Students: Internationalisation of Pedagogy and Curriculum in Higher Education, 227–240.

- Turner, Yvonne. 2015. “Last Orders for the Lecture Theatre? Exploring Blended Learning Approaches and Accessibility for Full-Time International Students.” International Journal of Management Education 13 (2): 163–169. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2015.04.001.

- Universities UK. 2017. “International Students Now Worth £25 Billion to UK Economy – New Research.” https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/news/Pages/International-students-now-worth-25-billion-to-UK-economy—new-research.aspx.

- Vemury, Chandra Mouli, Oliver Heidrich, Neil Thorpe, and Tracey Crosbie. 2018. “A Holistic Approach to Delivering Sustainable Design Education in Civil Engineering.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 19 (1): 197–216. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-04-2017-0049.

- Waldron, Rupert. 2017. “Positionality and Reflexive Interaction: A Critical Internationalist Cultural Studies Approach to Intercultural Collaboration.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1080/14703297.2016.1156010.

- Walker, Richard, and Zoe Handley. 2016. “Designing for Learner Engagement with Computer-Based Testing.” Research in Learning Technology 24: 1063519. doi:10.3402/rlt.v24.30083.

- Winch, Junko. 2016. “Does the Students’ Preferred Pedagogy Relate to Their Ethnicity: UK and Asian Experience.” Comparative Professional Pedagogy 6 (1): 21–27. doi:10.1515/rpp-2016-0003.

- Wu, Qi. 2015. “Re-Examining the ‘Chinese Learner’: A Case Study of Mainland Chinese Students’ Learning Experiences at British Universities.” Higher Education 70 (4): 753–766. doi:10.1007/s10734-015-9865-y.

- Yang, Ying, Jenna Mittelmeier, Miguel Antonio Lim, and Sylvie Lomer. 2020. “Chinese International Student Recruitment during the COVID-19 Crisis: Education Agents’ Practices and Reflections.” https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/173092496/Ying_et_al._2020_final.pdf.

- Zepke, Nick. 2014. “Student Engagement Research in Higher Education: Questioning an Academic Orthodoxy.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (6): 697–708. doi:10.1080/13562517.2014.901956.

- Zhang, Lulu, and Ying Zheng. 2018. “Feedback as an Assessment for Learning Tool: How Useful Can It Be?” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (7): 1120–1132. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1434481.