ABSTRACT

Students seem to encounter various challenges when writing bachelor’s and master’s theses, indicating a need to support them in their writing processes. In this study, academic writing workshops for students writing bachelor’s and master’s theses were developed and investigated during three years of a participatory action research project. The study uses a more-than-human approach to students’ thesis writing to explore how academic writing workshop practices are produced. Based on diffractive analytical engagements, this study conceptualizes the workshop practices as the enactment of academic writing workshop-ing in the spacetimemattering of the workshops. The workshop-ing recognizes the workshops as active doings with students and writing tutors in social and material realities; workshop-ing is an enacted practice, rather than preexistent or preceding. The study contributes to the existing literature with insights about how different entanglements matter in thesis writing practices and how workshop-ing can become productive in supporting students’ thesis writing.

Introduction

Most university students write a thesis, commonly involving a small-scale research project, to earn a bachelor’s or master’s degree. Students seem to encounter various problems in their thesis writing processes (Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006; Todd, Bannister, and Clegg Citation2004; Ylijoki Citation2001), indicating that there is a need to support them to complete their theses. Focus on improving the conditions for students’ thesis writing has increased, with research addressing supervision and student-supervisor relationships (e.g. Filippou, Kallo, and Mikkilä-Erdmann [Citation2021]; de Kleijn et al. [Citation2016]). Scholars have also emphasized the benefits of peer-learning and collaboration in thesis writing (Anderson, Day, and McLaughlin Citation2008; Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006; Miedijensky and Lichtinger Citation2016). Several studies have addressed collaborative aspects in terms of writing groups for doctoral students (e.g. Aitchison [Citation2009]; Colombo and Rodas [Citation2021]; Ferguson [Citation2009]). Although similar initiatives exist for bachelor’s and master’s students (e.g. Cameron, Nairn, and Higgins [Citation2009]; Delyser [Citation2003]; Dysthe et al. [Citation2006]), considerably less research focuses on that group.

Through consultations with supervisors and students, the current research project identified a need to support students’ thesis writing at Åbo Akademi University, Finland. During three years of a participatory action research project, academic writing workshops for students writing bachelor’s and master’s theses were developed. We acted as writing tutors and held the workshops when we were doctoral students and actively involved in our thesis writing processes. The theoretical premises of the study outline that supporting students’ thesis writing processes is not a human-centered endeavor, but it requires recognition of the material circumstances of the thesis writing. Consequently, we use a more-than-human approach to acknowledge writing as relational processes of becoming, affected and produced by humans and more-than-humans (Gourlay Citation2015). We recognize the inseparability of humans and more-than-humans and avert from thinking of the workshops as neutral containers; both humans and more-than-humans matter in the workshops and the writing processes.

This article explores the academic writing workshop practices developed, to learn how workshops can support students’ thesis writing and advance a more-than-human understanding of thesis writing.

Thesis writing and writing workshops

Previous studies have shown that students experience various challenges in academic and thesis writing, such as confusion about academic writing requirements (Elliott et al. Citation2019; Itua et al. Citation2014), lack of preparation for writing theses (Delyser Citation2003), and difficulties in completing them within the stipulated time (Dysthe Citation2002; Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006). Such struggles can prolong study time and increase drop-out, and this can worsen because students work alone (Todd, Bannister, and Clegg Citation2004; Ylijoki Citation2001). These aspects constitute a personal problem for students and a departmental problem as the number of graduates is a key performance indicator for institutions and departments (Ylijoki Citation2001). Additionally, thesis writing has often proved to be a source for emotions of disappointment, guilt, self-doubt, stress, and anxiety (Cameron, Nairn, and Higgins Citation2009; Ferguson Citation2009; Ylijoki Citation2001). Thus, writing workshops may be a constructive forum for discussing negative emotions about thesis writing among peers, which may improve emotional states and feelings (Cameron, Nairn, and Higgins Citation2009; Miedijensky and Lichtinger Citation2016).

In response to the common perception of thesis writing as a solitary process, scholars have argued for the importance of collaboration among peers (e.g. Ferguson Citation2009; Miedijensky and Lichtinger Citation2016). Collaborative writing environments can increase students’ emotional and motivational well-being and counteract loneliness in writing (Miedijensky and Lichtinger Citation2016). Scholars have emphasized the value of discussing the thesis process between students and supervisors (Anderson, Day, and McLaughlin Citation2008; Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006) and across different disciplines (Dysthe Citation2002; Itua et al. Citation2014). Thesis writing forums could advantageously welcome discussion and the sharing of understandings, hopes, fears, and uncertainties related to the thesis to create a safe environment (Anderson, Day, and McLaughlin Citation2008; Colombo and Rodas Citation2021; Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006; Ferguson Citation2009).

Proposing such a collaborative approach, Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim (Citation2006) developed a supervision model for master’s students with student colloquia, supervision groups, and individual supervision. Results showed that students experienced student colloquia as safe-havens, that supervision groups provided multivoiced feedback and disciplinary enculturation, and that individual supervision assured quality. Critical factors of success for the model were students’ motivation, engagement in peer projects, training in feedback strategies, personal commitment and attendance, clear routines, hearing multiple perspectives on writing, and realistic time allocation.

Research on supervision and student-supervisor relationships (e.g. Filippou et al. [Citation2021]; de Kleijn et al. [Citation2012]; de Kleijn et al. [Citation2016]) has increased, with some researchers highlighting concerns that writing workshops could address. de Kleijn et al. (Citation2016) found that some students needed more critical comments, which could reduce their motivation, and some students needed more supervision than the supervisor could give. The researchers suggested that writing workshops can address these aspects. Previous research has indicated positive traits of participating in writing workshops. It can enhance motivation, increase academic writing confidence, create a more positive take on thesis writing, shape academic writing identities, and improve scientific reasoning and writing skills (Cameron, Nairn, and Higgins Citation2009; Dowd et al. Citation2015; Ferguson Citation2009; Miedijensky and Lichtinger Citation2016). Additionally, the writing tutors’ academic writing beliefs and experiences can influence students’ beliefs and experiences (Itua et al. Citation2014). Research has also shown that teachers, or writing tutors, found that their writing improved when teaching workshops (Delyser Citation2003).

A more-than-human approach to writing

A more-than-human approach to academic writing acknowledges that humans and more-than-humans can become agentic and produce changes in the writing processes (Allen Citation2019; Gourlay Citation2015; Hort Citation2020). Acknowledgment of the more-than-humans’ agency has received little attention in previous research on academic writing (Gourlay Citation2015; Hort Citation2020; Rule Citation2013) because academic writing studies have primarily used a sociocultural academic literacies framework (see Lea and Street [Citation1998], [Citation2006]). However, theories adopting a more-than-human approach when studying writing are gaining ground on different educational levels.

Moving beyond a human-centered view on writing to account for different more-than-humans (e.g. spaces and texts) that contribute to producing the academic writing workshops, we think with more-than-human theories developed by Barad (Citation2007) and Deleuze and Guattari (Citation2013). We argue that reading these together can be productive in analyzing how the practices of the academic writing workshops matter in students’ thesis writing processes, although we are aware of the critique regarding the compatibility of Barad’s and Deleuze and Guattari’s ontologies (see Hein [Citation2016], for a more detailed discussion). A founding premise of a more-than-human approach is that knowledge is created in relations between humans and more-than-humans (Barad Citation2007). In a more-than-human approach, humans/more-than-humans are not separate, but these relations are intra-active becomings, according to Barad (Citation2007). They cannot be separated because they are entangled and not intertwined separate entities. A concrete example would be entanglements between students and computers when writing (e.g. Gourlay [Citation2015]).

The workshop practices are produced in intra-active becomings by active humans/more-than-human entanglements, where space, time, and matter are not static but always in the process of becoming (Barad Citation2007). Space can be understood differently depending on the field of science. In the current article, space is specifically related to writing and understood as more than a physical container. In the process of becoming, spaces for writing are produced iteratively by both humans and more-than-humans. Space is produced in relation to time that is ‘not a succession of evenly spaced individual moments’ (Barad Citation2007, 180). We understand such a spatial and temporal perspective to (re)configure the spacetime boundaries of writing and writing processes. Further, matter is not a fixed or static substance or thing, but instead, active doings and forces that come to matter in human/more-than-human entanglements (Barad Citation2007). Noteworthy, however, is the inseparability of space, time, and matter. Barad’s (Citation2007) concept of spacetimematter underscores this inseparability, emphasizing that space, time, and matter are mutually constituted. Barad asserted that the practices make a difference in relation to how the spacetime manifold is iteratively (re)configured. As such, ‘bodies do not simply take their place in the world … rather ‘environments’ and ‘bodies’ are intra-actively constituted’ (170). Thus, we assume that the students are not separated from the writing practices produced in the writing workshops, but rather, fundamentally entangled with them, which may affect the thesis writing processes in different ways. Therefore, we perceive spacetimematter as agential forces that emerge in an ongoing flow of intra-actions with the participants, writing tutors, materialities, and the environment in the workshop practices.

These Baradian concepts enable a complex analysis of the workshop practices. However, the Deleuzo–Guattarian (2013) concepts of affect and rhizome provide another way to approach the workshop practices. The current understanding of writing acknowledges the mind–body connection and recognizes writing as shaped and produced by material, embodied, and affective forces (Rule Citation2013). Affect encompasses the capacity to affect and be affected by other bodies and constitutes, accordingly, more than emotional reactions that can be put into words (Deleuze and Guattari Citation2013). Instead, affects are prepersonal and volatile intensities, which can be understood as diverse, embodied, experienced materialities. Applying an affective approach to writing allows conceptualization of how humans and more-than-humans relate and respond to different materialities (Rule Citation2013). Further, we also understand academic writing as rhizomatic, with Deleuze and Guattari (Citation2013) explaining a rhizome as a root system that spreads in different irregular and infinite directions with several non-hierarchical entries and exits. Such a relational approach to writing allows for exploration of the writing’s connections, multiplicity, and unpredictability in the workshops. Additionally, a rhizomatic approach enables a focus on the non-linearity of thesis writing. In the writing workshops, thesis writing is not constricted to a linear process but instead produced in an ongoing process of becoming human and non-human entanglements.

Using this more-than-human approach, we understand academic writing as relational, material, intra-active, affective, and rhizomatic. These premises emphasize writers and their texts as entangled (Allen Citation2019). Texts affect and are affected by humans/more-than-humans; writing is not an isolated activity but always created in relations to humans/more-than-humans (Burnett and Merchant Citation2021; Gourlay Citation2015). Therefore, rather than being a neutral backcloth to human agency, more-than-humans are perceived as active and necessary components in writing (Gourlay Citation2015; Rule Citation2013).

Aim and analytic questions

This study explores how the academic writing workshop practices are produced, guided by the following analytic questions: How do human/more-than-human entanglements produce the academic writing workshop practices, and how do these entanglements matter in students’ thesis writing processes?

Methodological engagements

The context of the workshops

In Finland, all university students write a bachelor’s thesis to earn a bachelor’s degree and a master’s thesis to earn a master’s degree. The nature of the theses varies between disciplines and study programs, but they generally encompass a scientifically reported, small-scale research project, conducted and written individually. Students can also write master’s theses in pairs. Students have an individual supervisor during the thesis process and receive obligatory content-related supervision individually and in seminar groups. Language guidance is optional but recommended. In these practices, students may present their work and receive feedback, but they do not actively write during these sessions. Thus, students are responsible for scheduling their own time for writing. Based on previous findings indicating that independent responsibility seems to be difficult for some students (Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006), and that diversity and interdisciplinarity in supervision groups seem to promote academic learning (Colombo and Rodas Citation2021), we developed academic writing workshops that welcomed bachelor’s and master’s students studying various subject areas.

The workshop structure

We developed the workshops during three participatory action research cycles in 2017–2019 (PAR; Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014). A more-than-human approach to PAR acknowledges the significance of material relations in the researched practice (Allen and Marshall Citation2019; Suopajärvi Citation2017). We planned, implemented, and evaluated the evolving workshop structure in dialogue with other project research members during the cycles. The actions taken to develop the workshops arose through our intra-activity with humans and more-than-humans, which had active parts in shaping the knowledge generation and developing the workshops.

The workshops shared some characteristics with writing courses and supervision models investigated in previous research (Delyser Citation2003; Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006), especially concerning the collaborative approach to thesis writing. Our structure differed from these approaches in that we, as writing tutors, were doctoral students and not the student’s supervisors. Thus, our intention was not to supervise the choice of subject, theory, or methodology, but rather to support the writing processes by offering a positive and supportive writing environment, to show genuine interest in their writing processes, and to initiate discussions about academic writing and research in general. The approach was collaborative as we approached the students’ theses as a joint project in the workshops and presented feedback in dialogue with writing tutors and students.

Starting with Cycle 1, we arranged the first workshops as a summer course (5–10 European Credit Transfer System credits; ECTS) for students enrolled in educational, social, and health sciences. The reason for arranging the course in the summer was to reduce students’ isolation during the summer break in June and August. Participation in the courses was voluntary, and the workshops offered a designated time and space for thesis writing, approximately two times a week, for three hours per workshop. The workshops offered three types of writing support, which we describe in detail below. We held the workshops in a computer room at the university library. The students needed an approved research plan to participate, and they could be in any phase of the thesis writing process. Sofia held the first course but felt the need for reinforcement from another writing tutor. When evaluating the workshops, the students requested a Moodle platform and the possibility to participate in workshops in July and during the academic year.

Anna joined as a writing tutor in Cycle 2, and we took turns holding the workshops. Cycle 2 included one course during the academic year and one summer course from June to August. However, July had low participation, probably due to July being the primary vacation month in Finland. When evaluating the courses, the students stated that they would appreciate pop-up workshops during the academic year without ECTS. The Moodle platform proved to be helpful for the students.

In Cycle 3, we opened the workshops for all students at the university campus. We tested pop-up workshops without ECTS during the academic year. However, we considered that structure unsuccessful because participation was meager and did not provide the structural framework of a course. Accordingly, the current study focuses on the workshops with ECTS, as that structure seemed to be the most efficient for supporting students’ writing processes. The summer course returned to being arranged in June and August. Consequently, we deemed that courses during the academic year and the summer breaks (June and August) constituted a successful structure.

The workshops offered three types of support: a) tutor feedback focusing on students’ drafts, b) small response group discussions with their peers, and c) larger whole-group thematic discussions with both the tutors and peers (see ). The students worked on their theses within and between the workshops to advance the writing process, but these types of support were offered only during the workshops. During the time spent outside these three types of support in the workshops, students worked on their theses. The tutor feedback mainly encompassed shorter, non-scheduled feedback sessions with the writing tutor, often involving detailed and individualized matters regarding their writing. In each workshop, the students had the opportunity to submit a draft to the tutors, who read and gave feedback. In the response groups, students gathered in small groups to give and receive feedback on their work-in-progress. All students received training in feedback strategies during a thematic discussion before meeting in the response groups. Lastly, the tutors facilitated thematic discussions, whose intention was to help students with the writing process and its mechanics, help them break their theses down into smaller, more graspable units, and discuss emerging issues; the discussions concerned both procedural and technical aspects of writing a thesis (see ). Participation in the thematic discussions was voluntary as the students were in different phases of their writing processes. Response groups and thematic discussions were arranged on different days.

Table 1. Three types of support in the workshops.

Research materials and analytical engagements

We produced several research materials in the three PAR cycles, during which we held four courses. Participation in the research project was voluntary, and a total of 92 students gave their written consent to participate in the study. The produced research materials (see ) contributed to the development of the workshops. As the workshop structure evolved, the research strategies changed to continue developing the workshops.

Table 2. Overview of the produced materials.

We administered electronic, anonymous, open-ended questionnaires to evaluate the workshops for further development. In the audio-recorded group interviews, groups of 2–5 students received questions to discuss independently without tutors/researchers to give them opportunities to discuss the thesis writing and writing workshops freely among peers. Moreover, we kept logbooks of our experiences in the workshops. The research materials also included our bodyminded experiences of the workshops, which we understand as embodied materials that escape language (see Ellingson [Citation2017]). Our bodyminded experiences included emotional aspects of working as tutors, the embodied act of participating in the workshops, and discussions with and responses given by students, supervisors, and research project members. We perceived these produced materials as lively and agentic as their agentic capacities contributed to developing the workshops between the PAR cycles. The research materials were non-hierarchical; we did not foreground a specific type of material but read them through each other with the theoretical premises.

We performed a diffractive analysis to analyze the workshop practices. Diffraction is an optical and physical phenomenon, which Barad (Citation2007) explained as waves that bend and spread in new ways when encountering an obstacle. A diffractive analysis is about reading materials and theory through each other and studying how differences make a difference, rather than identifying sameness through themes or categories (Barad Citation2007; Lenz Taguchi Citation2012). Accordingly, the analysis focused on identifying differences and exploring their effects, following Barad (Citation2007) who stressed that ‘a diffractive methodology provides a way of attending to entanglements in reading important insights and approaches through one another’ (30). Thus, in dialogue with Anna, Sofia primarily performed the analysis by reading with the concepts of intra-action, entanglement, spacetimematter, affect, and rhizome and putting them to work when analyzing the empirical materials (see ).

In the analysis, we enacted agential cuts, which can be explained as separating what is researched from how it is researched (Barad Citation2003, Citation2007). Enacting agential cuts enables investigation of different phenomena by freezing entanglements – a cut can bring things together and take them apart (Barad Citation2007) – to analyze how they produced the academic writing workshop practices. As such, we enacted agential cuts in three entanglements that produced the workshop practices and cut them together-apart to analyze how the entanglements mattered in students’ writing processes. Reading the research materials diffractively from our bodies as tutors/researchers, we were agential parts of the analysis and responsible for the cutting together-apart in the analysis.

Analyzing the workshop practices

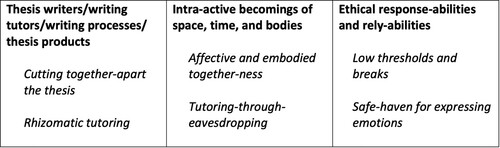

The analysis included two parts. First, we enacted agential cuts in three entanglements, and second, we analyzed how the entanglements mattered in students’ thesis writing processes. The entanglements and how they mattered in students’ thesis writing processes are presented in .

Thesis writers/writing tutors/writing processes/thesis products

Entanglements of thesis writers/writing tutors/writing processes/thesis products produced the workshop practices. The written texts were entangled with the students and tutors; they affected the texts, and the texts affected them. This entangled inseparability indicated that every workshop, in its here-and-now, was dynamic in becoming something new and different. No two workshops were alike.

Our tutoring approach was (in)formal. The formal part concerned the three types of support, while the informal part concerned the students’ desires and here-and-now needs. The (in)formal tutoring produced and was produced by a pedagogical indeterminacy rather than an outcome-based approach; we could not determine the exact direction of the workshops due to the unpredictability of students’ here-and-now needs. Due to the students’ questions, we addressed a type of tacit knowledge of academic writing, making us more aware of what choices we make when writing. In our tutoring, our doctoral thesis processes and the students’ writing processes intra-acted as we used our texts, problems, and solutions as examples. The tutoring we enacted was affected by our own experiences and motivation toward thesis writing, and our motivation towards academic writing was experienced as contagious by students:

It has been great to have motivated and encouraging writing tutors who seem to like academic writing, because that attitude is contagious in a good way. Also, I am very grateful to get a response immediately, to be able to ask questions and submit parts of my text. (Student, questionnaire, 2019)

After reading Linda’s text, it’s a bit calmer in the classroom, so I write in my logbook. I think about how much my writing process affects me as a tutor. Yesterday, I had a positive supervision conversation with my supervisor, and my motivation was raised after being quite low for about two weeks. I feel that I give much better feedback to the students’ texts today because I am motivated myself, while last week, it felt quite heavy. (Anna’s logbook, 2019)

These entanglements mattered in the students’ thesis writing processes as they enabled a cutting together-apart the thesis and rhizomatic tutoring.

Cutting together-apart the thesis

Cutting together-apart the thesis was about making sense of the thesis, but also about unmaking sense as we covered a multitude of different possibilities and perspectives in writing a thesis that is dependent on, for example, fields of science, theories, and methodologies. The (un)making embraced that thesis writing was not a linear and straightforward process; it included making complicated choices throughout the writing processes and disrupting preconceived beliefs of how thesis writing should be done. We often cut together-apart our doctoral theses to provide examples for the students. For example, when discussing how to write an introduction, we cut together-apart introductions we had written and then analyzed the structure with the students. The cutting together-apart was particularly agential in the thematic discussions:

I learned much about what the different parts of a thesis should contain and what I should focus on in my writing. (Student, questionnaire 2018)

Moodle is available as support when you need to refresh your knowledge. Great that all materials are available from the beginning of the course because everyone is at different phases in their writing. (Student, questionnaire, 2019)

Rhizomatic tutoring

The entanglements also mattered in students’ thesis writing processes because of the rhizomatic tutoring approach used. Our (in)formal tutoring approach was rhizomatic because all students were at different phases in their writing processes, indicating that we did not approach thesis writing linearly in the workshops. Our tutoring had multiple entries and exits to respond to the students’ here-and-now needs. This rhizomatic approach meant that students did not have to compare their writing processes and how far they had come with the other participants in the workshops, thus removing a stressful element in thesis writing.

Except for participating in response groups, the students could choose how much tutoring they wanted, making the optionality of the rhizomatic tutoring approach agentic. Due to this rhizomatic approach, the thematic discussions were not always current for all students; some students had either ‘completed’ or not yet reached that part of the writing:

The themes addressed after the summer break were not yet so relevant in the writing phase I am in, and therefore it did not feel so rewarding. But it was positive to have participated and saved the discussed material for future use. (Student, questionnaire, 2017)

It is satisfying to look out over the writing group and see that EVERYONE is concentrating on something. When I left at noon, most students were still there and wanted to continue to write. That is a good sign. (Anna, logbook, 2019)

Intra-active becomings of space, time, and bodies

The writing practice emerged in a particular space, in a particular time, and with particular humans (e.g. tutors and students) and more-than-humans (e.g. computers and texts), highlighting the open-ended becoming of spacetimemattering in the workshops. The inseparability of the space where the thesis writing occurred, the time scheduled in the students’ calendars, and other student bodies in the same situation became productive in the workshops:

We have had exact times for when to be there; it gives structure and framework. I know that I will work there and then, but I also have these workshops as a “carrot” when I work at home. (Student, questionnaire 2017)

It was a bit crazy when I arrived at 1 pm because the computer room had been double-booked […]. We tried to find another computer room, but there was none … We had to solve it with everyone who participated in the workshop going to the library and using a public computer or sitting somewhere with their laptops. It did not seem to be a big problem for most students because they sat down in the library and started working. I took a group (7), who wanted to discuss literature searches, with me. […] When I came back to the computer room/library, there were about ten students left who wrote. The rest had probably gone home because I could not find them anywhere. Previously, it has been very unusual for someone to leave the workshop early, so I guess that the lack of a shared space, which included me as a leader and the support of fellow students, caused the disappearances. This phenomenon is interesting in itself and possibly shows how important this shared physical space actually is, where you sit and work next to each other where everyone can see each other work. (Anna’s logbook, 2019)

The spacetimematterings of the workshops mattered in multiple ways and were not a neutral container for thesis writing. The intra-active becomings of space, time, and bodies mattered in students’ writing processes by producing an affective and embodied together-ness and by tutoring-through-eavesdropping.

Affective and embodied together-ness

The entanglements identified above moved the workshops beyond the commonly perceived solitary one-ness of thesis writing, which mattered in students’ thesis writing processes in producing and embracing an affective and embodied together-ness with students writing theses in the same space, at the same time. The materialities of thesis writing brought everyone together in the workshops and created a writing community:

The workshops might create some kind of togetherness like you are actually not alone against the world; the others are here and struggling, in some way like a community. (Student, interview 2019)

The students discussed thesis writing together, discussed thesis writing with me, discussed the workshop’s theme, and it was really rewarding. I notice that they have started to get to know each other now as well. (Sofia, logbook, 2019)

Student bodies writing in the same space mattered as seeing other students write simultaneously made the thesis writing a collaborative process that the participants underwent together. This affective and embodied together-ness could create possibilities to overcome negative feelings about the thesis writing process. The students appreciated the response groups, where students gave constructive feedback on each other’s texts, feeling that it contributed to their writing.

Ultimately, the affective and embodied together-ness was related to the tutors as our being-in-the-same-room mattered in the students’ writing processes. The fact that the students knew that we were there if they needed us has contributed to their writing processes. Our support has been agentic for the affective and embodied together-ness even though the students have not requested, for example, tutor feedback.

Tutoring-through-eavesdropping

The spacetimematterings enabled an (in)formal approach of tutoring-through-eavesdropping in the workshops. As we held the tutoring discussions in the workshop space, other students had the opportunity to eavesdrop. Accordingly, the tutoring approach was also productive for the other students as they could listen in on the discussion, ask follow-up questions, learn from other students’ questions, and the writing tutors’ recommendations:

It has been a nice atmosphere and fun to be able to talk and hear what kind of questions others have asked during the discussions. (Student, questionnaire, 2019)

I sometimes find it disturbing when others talk, because I want it to be completely silent when I work. No talking, no music. (Student, questionnaire, 2017)

Ethical response-abilities and rely-abilities

The workshops were produced in relations to the tutors’ ethical considerations. Barad stated that ‘agency is about response-ability, about the possibilities of mutual response, which is not to deny, but to attend to power imbalances’ (Dolphijn and van der Tuin Citation2012, 55). Since we were not the students’ supervisors, we had other ethical response-abilities for their writing processes than their supervisors. The response-abilities were entangled with what we call our ethical rely-abilities, as the students relied upon and confided in us about their thesis writing and sometimes also in deeply personal matters:

[A good writing tutor should be] understanding, in some way, and actually want to know what you are writing and what kind of help you need. Maybe what your goal is with the thesis, like if it is just to pass with the lowest possible effort or if you want the highest grade. Then they can adjust the tutoring according to that. (Student, interview, 2019)

I have had difficulties receiving answers from my supervisor. I write an email, and then it takes a long time [to get an answer]. (Student, interview, 2019)

These entanglements mattered in the students’ writing processes because they produced low thresholds and breaks and safe-havens for expressing emotions.

Low thresholds and breaks

Ethical response-abilities and rely-abilities mattered in the students’ thesis writing processes by producing low thresholds in the workshops. Students experienced that the workshops were more relaxed compared with other supervision forums:

I do not feel that the threshold has been too high to dare to send in a text (Student, questionnaire, 2018)

Especially now, at the beginning of August, before the students’ supervisors return to work and the students contact their supervisors, the workshops are important and productive because the students need help, and they tell me that I help them […] I feel more needed in August compared to June. (Sofia’s logbook, 2019)

Safe-haven for expressing emotions

Our ethical response-abilities and rely-abilities mattered in the students’ writing processes by producing a safe-haven for expressing emotions about thesis writing. This safe-haven was produced through the together-ness created between students and tutors, by discussing thesis writing with other students in the same situation, and through trusting each other:

Great to meet other students who write theses and to get the opportunity to think with them, and “ventilate” some anxiety, and to be able to ask questions when needed. (Student, questionnaire 2017)

And it feels like, the only thing I will get out of it [writing the thesis] is that one stressful element is removed from my life. (Student, interview, 2019)

Negative emotions regarding different aspects of the writing came to the surface, and sometimes, relieving some pressure could make a difference in students’ writing processes. This emphasized thesis writing as a profoundly affective process where diverse, embodied, experienced materialities mattered. To allow these negative emotions, we also shared some of our feelings and frustrations and how we have tried to overcome them. Discussing negative emotions about thesis writing could even erase some preconceived negative notions about what thesis writing is and how it ‘should be done.’ This aspect created a sense of together-ness, and we acknowledged that all writers, no matter their experience, sometimes struggle with various parts of the writing process.

Discussing academic writing workshop-ing

Based on the analysis, we conceptualize the workshop practices as the enactment of academic writing workshop-ing in the spacetimemattering of the workshops. Workshop-ing recognizes the workshops as active doings with students and tutors in social and material realities; workshop-ing is an enacted practice, rather than preexistent or preceding. The workshop-ing encompasses specificities of the (in)formal tutoring of cutting together-apart the thesis in rhizomatic ways, the intra-active relations of space, time, and bodies producing affective and embodied together-ness and opportunities for tutoring-through-eavesdropping, as well as the tutors’ ethical response-abilities and rely-abilities creating low thresholds and safe-havens for approaching thesis writing.

The workshop-ing produces a collaborative thesis writing environment with low thresholds to ask for help, which can contribute to students’ thesis writing processes as other supervision forums can have higher thresholds (Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006). As students experience different challenges in academic writing processes (Delyser Citation2003; Dysthe Citation2002; Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006; Elliot et al. 2019; Itua et al. Citation2014; Ylijoki Citation2001), and some students need more guidance than the supervisors can provide (de Kleijn et al. Citation2016), the workshop-ing seems to be useful and helpful for the students. The workshop-ing also goes beyond the actual act of writing to attend to students’ here-and-now needs on an affective level. Agreeing with previous research (Cameron, Nairn, and Higgins Citation2009; Ferguson Citation2009; Ylijoki Citation2001), the results demonstrate that students sometimes feel stress and anxiety about writing a thesis. Workshop-ing attends to these emotional states to create a safe environment, which has been deemed necessary in previous research (Cameron, Nairn, and Higgins Citation2009; Colombo and Rodas Citation2021; Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006; Miedijensky and Lichtinger Citation2016). We propose that the workshop-ing’s affective and embodied together-ness can raise students’ motivation and engagement in thesis writing, thus suggesting similar implications for practice as in the supervision model proposed by Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim (Citation2006). Like their supervision model, the workshop-ing produces routines, provides training in feedback strategies, and presents multiple perspectives on writing. However, this study adds a different structural and relational perspective as the tutors are not the students’ supervisors. Importantly, this study also contributes with knowledge about the value of tutoring-through-eavesdropping in collaborative writing environments, which we suggest is crucial to consider as an essential part of the academic writing workshop-ing.

We maintain that the workshop-ing approach can promote both the students and the tutors – in this case, doctoral students – who arrange the workshops (cf. Delyser [Citation2003]). However, due to how the tutors matter in students’ writing processes, their writing experiences cannot be treated separately from the workshop-ing (Itua et al. Citation2014). This aspect highlights the importance of the tutors’ beliefs and approaches toward academic writing to support the students in terms of raising motivation, confidence, and providing writing support. The fact that doctoral students also experience problems in their writing processes (e.g. Colombo and Rodas [Citation2021]; Ferguson [Citation2009]) can be advantageous, because they might have experience of the problems that the students face, but also disadvantageous if the problems become insurmountable and reduce their motivation and self-confidence for academic writing. With this in mind, we urge transparency regarding the writing processes on the part of writing tutors. Taking part in how more experienced writers have encountered and overcome problems can support students’ thesis writing processes in an affective, reinforcing, and motivating manner.

The results indicate that students’ thesis writing processes are affected by a multiplicity of humans/more-than-humans. Nevertheless, decentering the human through a more-than-human perspective has implications for thesis writing. Adding to knowledge advanced in previous research using more-than-human approaches (Allen Citation2019; Gourlay Citation2015; Hort Citation2020; Rule Citation2013), the study blurs the boundaries between the student as the ‘subject’ and the thesis as the ‘object.’ The thesis writing happens in-between bodies; the student affects and is affected by the thesis, pointing to how entanglements of student/thesis in the workshop-ing can produce changes for the students’ thesis writing processes. This study has demonstrated how the materialities of the academic writing workshop-ing are not and cannot be a mere backdrop as they make something happen in students’ thesis writing processes in different ways.

Conclusions

The study has implications for higher education, in which thesis writing is an essential part of obtaining a university degree. We suggest that three aspects, in particular, have implications for supporting students’ thesis writing processes through academic writing workshop-ing: Recognition of the value and opportunities of tutoring and supervision in collaborative environments (e.g. tutoring-through-eavesdropping); utilization of collaboration and support across bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral student levels; and acknowledgment of the agency of more-than-humans in supporting students’ thesis writing processes. We recommend consideration of these aspects. This study has generated knowledge about how the proposed academic writing workshop-ing approach matters in students’ thesis writing processes, thus contributing valuable insights about how academic writing practices and supervision forums can be further developed and what aspects can become productive and support students’ thesis writing.

The results align with previous arguments that it is fruitful to support students in multiple ways during their thesis writing processes, which is also supported by the fact that multiple supervision and tutoring forums can make students more independent in their thesis writing processes (Dysthe, Samara, and Westrheim Citation2006). As thesis writing is connected to students’ study performances and acts as a performance indicator for departments (Ylijoki Citation2001), it is essential to offer students support to complete their theses within the stipulated time. What remains unknown, however, is how supervisors experience writing workshop-ing to affect and complement the content-related supervision they provide to students. Also, the workshop-ing is limited to students who deliberately turn to the workshops. Students who need the most support may not participate because workshop participation is voluntary. Research is still needed to address how to support all students, especially those who struggle with thesis writing. Nevertheless, based on the present study, we propose that giving bachelor’s and master’s students opportunities for academic writing workshop-ing with doctoral students constitutes a step toward creating flexible and multifaceted practices that support students’ thesis writing in higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aitchison, C. 2009. “Writing Groups for Doctoral Education.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (8): 905–916. doi:10.1080/03075070902785580.

- Allen, S. 2019. “The Unbounded Gatherer: Possibilities for Posthuman Writing-Reading.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 35 (1): 64–75. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2018.07.001.

- Allen, S., and J. Marshall. 2019. “What Could Happen When Action Research Meets Ideas of Sociomateriality?” International Journal of Action Research 15 (2): 99–112. doi:10.3224/ijar.v15i2.02.

- Anderson, C., K. Day, and P. McLaughlin. 2008. “Student Perspectives on the Dissertation Process in a Master’s Degree Concerned with Professional Practice.” Studies in Continuing Education 30 (1): 33–49. doi:10.1080/01580370701841531.

- Barad, K. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (3): 801–831. doi:10.1086/345321.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Burnett, C., and G. Merchant. 2021. “Returning to Text: Affect, Meaning Making, and Literacies.” Reading Research Quarterly 56 (2): 355–367. doi:10.1002/rrq.303.

- Cameron, J., K. Nairn, and J. Higgins. 2009. “Demystifying Academic Writing: Reflections on Emotions, Know-How and Academic Identity.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 33 (2): 269–284. doi:10.1080/03098260902734943.

- Colombo, L., and E. L. Rodas. 2021. “Interdisciplinarity as an Opportunity in Argentinian and Ecuadorian Writing Groups.” Higher Education Research & Development 40 (2): 207–219. doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1756750.

- de Kleijn, R. A. M., L. H. Bronkhorst, P. C. Meijer, A. Pilot, and M. Brekelmans. 2016. “Understanding the Up, Back, and Forward-Component in Master’s Thesis Supervision with Adaptivity.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (8): 1463–1479. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.980399.

- de Kleijn, R. A. M., M. T. Mainhard, P. C. Meijer, A. Pilot, and M. Brekelmans. 2012. “Master’s Thesis Supervision: Relations Between Perceptions of the Supervisor–Student Relationship, Final Grade, Perceived Supervisor Contribution to Learning and Student Satisfaction.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (8): 925–939. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.556717.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. [1987] 2013. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Delyser, D. 2003. “Teaching Graduate Students to Write: A Seminar for Thesis and Dissertation Writers.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 27 (2): 169–181. doi:10.1080/03098260305676.

- Dolphijn, R., and I. van der Tuin. 2012. New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. Open Humanities Press.

- Dowd, J. E., M. P. Connolly, R. J. Thompson, and J. A. Reynolds. 2015. “Improved Reasoning in Undergraduate Writing Through Structured Workshops.” The Journal of Economic Education 46 (1): 14–27. doi:10.1080/00220485.2014.978924.

- Dysthe, O. 2002. “Professors as Mediators of Academic Text Cultures: An Interview Study with Advisors and Master’s Degree Students in Three Disciplines in a Norwegian University.” Written Communication 19 (4): 493–544. doi:10.1177/074108802238010.

- Dysthe, O., A. Samara, and K. Westrheim. 2006. “Multivoiced Supervision of Master’s Students: A Case Study of Alternative Supervision Practices in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (3): 299–318. doi:10.1080/03075070600680562.

- Ellingson, L. L. 2017. Embodiment in Qualitative Research. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Elliott, S., H. Hendry, C. Ayres, K. Blackman, F. Browning, D. Colebrook, C. Cook, et al. 2019. “‘On the Outside I’m Smiling but Inside I’m Crying’: Communication Successes and Challenges for Undergraduate Academic Writing.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 43 (9): 1163–1180. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2018.1455077.

- Ferguson, T. 2009. “The ‘Write’ Skills and More: A Thesis Writing Group for Doctoral Students.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 33 (2): 285–297. doi:10.1080/03098260902734968.

- Filippou, K., J. Kallo, and M. Mikkilä-Erdmann. 2021. “Supervising Master’s Theses in International Master’s Degree Programmes: Roles, Responsibilities and Models.” Teaching in Higher Education 26 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1636220.

- Gourlay, L. 2015. “Posthuman Texts: Nonhuman Actors, Mediators and the Digital University.” Social Semiotics 25 (4): 484–500. doi:10.1080/10350330.2015.1059578.

- Hein, S. F. 2016. “The New Materialism in Qualitative Inquiry: How Compatible Are the Philosophies of Barad and Deleuze?” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 16 (2): 132–140. doi:10.1177/1532708616634732.

- Hort, S. 2020. “Skrivprocesser på högskolan. Text, plats och materialitet i uppsatsskrivandet” Writing Processes in Higher Education. Text, Places, and Materiality in Essay Writing”]. PhD diss., Örebro University.

- Itua, I., M. Coffey, D. Merryweather, L. Norton, and A. Foxcroft. 2014. “Exploring Barriers and Solutions to Academic Writing: Perspectives from Students, Higher Education and Further Education Tutors.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 38 (3): 305–326. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2012.726966.

- Kemmis, S., R. McTaggart, and R. Nixon. 2014. The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Singapore: Springer.

- Lea, M. R., and B. V. Street. 1998. “Student Writing in Higher Education: An Academic Literacies Approach.” Studies in Higher Education 23 (2): 157–172. doi:10.1080/03075079812331380364.

- Lea, M. R., and B. V. Street. 2006. “The ‘Academic Literacies’ Model: Theory and Applications.” Theory Into Practice 45 (4): 368–377. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4504_11.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. 2012. “A Diffractive and Deleuzian Approach to Analysing Interview Data.” Feminist Theory 13 (3): 265–281. doi:10.1177/1464700112456001.

- Miedijensky, S., and E. Lichtinger. 2016. “Seminar for Master’s Thesis Projects: Promoting Students’ Self-Regulation.” International Journal of Higher Education 5 (4): 13–26. doi:10.5430/ijhe.v5n4p13.

- Rule, H. K. 2013. “Composing Assemblages: Toward a Theory of Material Embodied Process.” PhD diss., University of Cincinnati.

- Suopajärvi, T. 2017. “Knowledge-Making on ‘Ageing in a Smart City’ as Socio-Material Power Dynamics of Participatory Action Research.” Action Research 15 (4): 386–401. doi:10.1177/1476750316655385.

- Todd, M. J., P. Bannister, and S. Clegg. 2004. “Independent Inquiry and the Undergraduate Dissertation: Perceptions and Experiences of Final-Year Social Science Students.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 29 (3): 335–355. doi:10.1080/0260293042000188285.

- Ylijoki, O.-H. 2001. “Master’s Thesis Writing from a Narrative Approach.” Studies in Higher Education 26 (1): 21–34. doi:10.1080/03075070020030698.