ABSTRACT

This systematic literature review provides an overview of existing empirical research on embodied teaching and learning in higher education. The review is based on a literature search in eleven databases resulting in 247 articles being included. These articles span a wide range of disciplines in higher education, with 66 articles situated in teacher education representing a significant proportion. By exploring the research shared in these articles and how the articles describe embodiment and the aspects of embodiment that they foreground, we are approaching research on embodied teaching and learning as a potential new research field. Our findings indicate that existing research primarily foregrounds cognitive and discursive aspects of embodiment, leaving its sensory, bodily and intersubjective aspects in the background. Research into embodied teaching and learning shows that it has the potential to become an interdisciplinary research field. However, this emerging field appears fragmented, with limited discussion and knowledge-building across publications.

Introduction

In this article we present and critically discuss the results of a qualitative systematic literature review on embodied teaching and learning in higher education in an effort to form an overview of existing empirical research, detect research gaps and make suggestions for further research. The overarching question is how research on embodiment in teaching and learning are discussed in the articles, how the articles describe embodiment in teaching and learning and which aspects of embodiment they foreground. In this way we are exploring embodied teaching and learning as a potential field of research in higher education in general and in teacher education specifically.

Traditionally, pedagogy has not emphasised the body in teaching and learning, treating mind and body as a dichotomy in which the body is regarded primarily as a subordinate instrument in service of the mind (Nguyen and Larson Citation2015). The body has either been marginalised or rejected as a source of knowledge (Bresler Citation2004; Estola and Elbaz-Luwisch Citation2003; Forgasz and McDonough Citation2017; Macintyre Latta and Buck Citation2007). More recently, several educational researchers have recognised the value of embodied knowledge and the embodied nature of teaching and learning (Andrews Citation2016; Craig et al. Citation2018; Forgasz and McDonough Citation2017; Mitchell and Reid Citation2015; Ørbæk Citation2021). For instance, Craig et al. (Citation2018) state that ‘embodied knowledge sits at the heart of teaching and teacher education’ and that teaching and learning are fully dependent on it (Craig et al. Citation2018, 329). Viewing teaching and learning as inherently embodied practices requires an explicit focus on embodiment, both in higher education and in educational research. As Forgasz and McDonough (Citation2017) assert, this may offer new methodological and pedagogical opportunities for exploring and understanding the emotional and embodied dimensions of teaching and learning to teach (Forgasz and McDonough Citation2017).

In teacher education and in other disciplines in higher education, as well as in the broader field of education, there are diverse understandings and several definitions of the concept of embodiment. We will begin this article with an elaboration on the concept of embodiment and an outline of our theoretical framework. After that, we will describe our methods for selecting, analysing and categorising articles. Finally we will present our five categories, the articles within them, important findings that underpin our discussion and suggestions for further research.

Embodiment

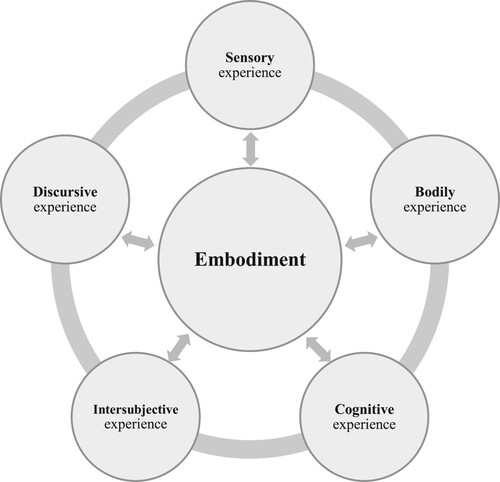

The philosophical roots of embodiment date back to the post-war French philosophers, most notably Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, Foucault, and Bourdieu. These philosophers drew attention to the centrality of the body to mind and being. The body/mind relation has also been addressed by Dewey and by Lakoff and Johnson, amongst others (Bresler Citation2004; Sööt and Anttila Citation2018). Traditionally, Merleau-Ponty is recognised as having introduced the body into philosophy, and he is usually regarded as the father of embodied phenomenology. However, he was heavily influenced by Husserl’s theory of the body. Husserl’s descriptions suggest that embodiment consists of several connected layers of experience (Rodemeyer Citation2018b). Rodemeyer identifies five intersecting and overlapping layers of embodiment in the work of Husserl: (1) primordial or hyletic flow, (2) passive synthesis, (3) active constitution, (4) interpersonal intersubjectivity and (5) intersubjective community (Rodemeyer Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020b). These layers indicate different aspects of embodied experience. In this study, we refer to the layers of embodiment as aspects of embodiment. Turning to how these aspects appear, we refer to them as (1) sensory experience, (2) bodily experience, (3) cognitive experience, (4) intersubjective experience and (5) discursive experience ().

Aspects of embodiment

Our outline of these aspects of embodiment draws on Rodemeyer’s theorisation on layers of embodiment (Rodemeyer Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The sensory experience aspect of embodiment is the flow of primary sense data that underlies our active perception. This aspect of embodiment grounds its other aspects and goes far beyond the traditional five senses. It includes all bodily sensations, which Fuchs refers to as the affective component of bodily resonance, such as feelings of warmth or coldness, tickling or shivering, tension or relaxation (Fuchs Citation2016). In the bodily experience aspect of embodiment, consciousness is engaged indirectly and we do not pay attention to the work that is being done by consciousness. This aspect relates to embodied habits, patterns of movements such as sedimented practices, movement repetitions, and movement training and what Sheets-Johnstone refers to as the experience of movement (Sheets-Johnstone Citation2009). Cognitive experience is the aspect of individual meaning constitution and cognitive awareness, based on our bodily experience of ourselves. The traditional understanding of pedagogy primarily foregrounds this aspect with its weight on reflection and language-based construction of meaning. According to Rodemeyer, this is also the most common understanding of Husserl’s phenomenology (Rodemeyer Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The intersubjective experience aspect of embodiment addresses our one-to-one relation with others or in small groups and our experience of living in a shared world with specific others. Fuchs (Citation2016) and De Jaegher’s (Citation2018) theorisation on embodied intersubjectivity and interaffectivity provide insights into this aspect (De Jaegher Citation2018; Fuchs Citation2016). Discursive experience addresses the meanings of embodiment that develop within a culture, and the transition from one generation to another. Here we find traditional and institutional attitudes about specific types of embodiment, such as how race, disability and gender are expressed in various embodied ways. This level also concerns how bodies are perceived by and expressed within a community and institutions and how this filters in through individual bodies (Rodemeyer Citation2018a, Citation2020b).

Rodemeyer suggests that we experience through all of these aspects at once, and our lived embodiment is always a mixture of them. They mutually influence one another, filtering in and working together to constitute the body as a whole. For instance, discourse about the body affects what we sense, and what we sense can contribute to changed discourse (Rodemeyer Citation2018a, Citation2020b). What Rodemeyer outlines is a broad understanding of embodiment that may unify multiple perspectives. We use this theoretical framework to analyse the research on embodied teaching and learning.

Materials and methods

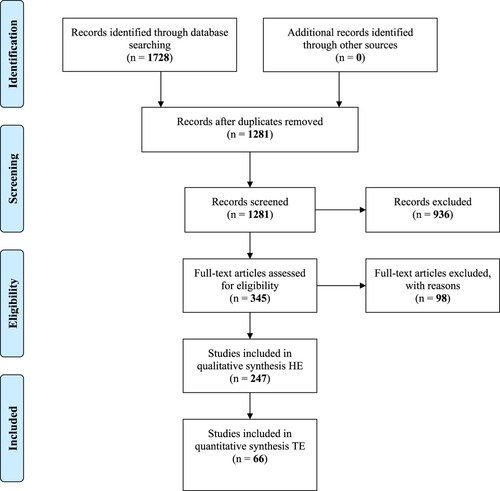

Our review is a qualitative systematic literature review (Sutton et al. Citation2019). To identify the articles relevant to exploring embodied teaching and learning in higher education, we employed five steps inspired by Pautasso (Citation2013): (1) conducting initial searches and preparing search strings, (2) searching in 11 electronic databases, (3) screening and including/excluding, (4) full-text reading and including/excluding, and (5) identification of the articles situated in teacher education. The different phases of the review process are presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (see ).

Database search and selection of articles

The literature search was conducted between 28 August and 2 September 2020 in seven international databases: ERIC, Academic Search Premier, Web of Science, Scopus, Social Science Premium Collection, SportDiscus and the Music Periodicals Database. The selection of search terms was based on our knowledge of the field, initial searches, guidance from university librarians and terms from relevant articles and database thesauruses. Search terms were consistent across the databases. We used the following search string: ((embod* OR corporeal*) NEAR/3 (pedagog* OR teach* OR learn*)) AND ((‘higher education’) OR college* OR universit* OR (‘post-secondary’) OR postsecondary)). Because of the variations among the databases as regards characters, abbreviations and search options, we had to make some adjustments during the search process. A corresponding literature search was conducted in four Scandinavian databases: ORIA, SWePub, the Danish National Research Database and NORART.

On the basis of our knowledge of the field, we expected a manageable quantity of hits and decided not to limit the timespan. In the initial database search, a total of 1,728 articles were identified. After removing duplicates, the number was reduced to 1, 281. The next phase involved screening of titles and abstracts for the remaining articles. They were assessed for relevance according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) published in a scientific journal, (2) peer-reviewed, (3) addressing the topic of embodied teaching and learning, (4) situated in higher education/teacher education, (5) based on empirical studies and (6) written in English, French or a Scandinavian language. This inclusion/exclusion process resulted in 345 potentially relevant articles across a range of disciplines in higher education. After reading the full texts, the number of articles was further reduced to 247. Sixty-six of these 247 articles are situated in teacher education. We define teacher education broadly. This suggests that articles from, say, physical education teacher education, arts teacher education and dance teacher education are included in the review. The articles included in the present review were identified individually by the two authors, who used a combination of EndNote X9 and RAYYAN software ().

Analysis and categorisation

In our exploration of embodied teaching and learning as a potential research field, we draw on Bourdieu’s concepts of scientific field and scientific habitus, ‘a temporary construct which takes shape for and by empirical work’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 161). According to Bourdieu and Wacquant (Citation1992), participation in a research field has to do with being among those who can formulate the set of rules, the methods and the discussions that the field of research engages with. A research field, in other words, emerges through the formulation of research projects and the choice of research topics, theoretical perspectives, methodologies and methods. To be part of a research field also involves publishing research and participating in ongoing discussion. We primarily paid attention to research subject(s), geography, journals, methodology, theoretical perspectives and researchers and we used a combination of EndNote X9 and Excel software.

To further explore the concept of embodiment in teaching and learning, we chose to examine the articles contextualised within teacher education by conducting content analysis, a research method for the subjective interpretation of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes and patterns (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). We initially conducted a conventional content analysis, primarily deriving coding categories inductively from the text data (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). We then further developed the categories through levels of embodiment (Rodemeyer Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020b), which we have referred to above as aspects of embodiment. This theoretical framework provides a broad but nuanced understanding of embodiment that provide an opportunity to explore the kinds of embodied experience that the various studies are looking at. This is primarily a matter of foregrounding certain aspects while leaving other aspects in the background. We use aspects of embodiment to analyse the empirical articles that we identified, emphasising which aspects they foreground. Through the analytical process described above, the 66 articles that are situated in teacher education were finally categorised within five main categories: (1) awareness of embodiment, (2) embodied diversity and discursive experience, (3) practice of embodied teaching, (4) teaching as embodied practice and intersubjective experience and (5) learning as sensory and bodily experience. In the next section, we begin with a brief descriptive overview of the articles identified, situated respectively in higher education and teacher education. This overview is followed by a more detailed presentation of the five categories and the articles within them.

Results

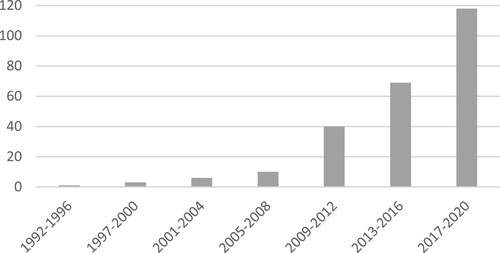

The 247 articles span a wide range of disciplines in higher education, with the 66 articles situated in teacher education representing a significant proportion of these. In researching embodied teaching and learning in higher education, we find disciplines as diverse as medicine (Cooper and Tisdell Citation2020), anthropology (Nuttall Citation2018), physics (Close and Scherr Citation2015), agriculture (Robinson Citation2018), nursing (Knutsson, Jarling, and Thorén Citation2015), the arts (Kvammen, Hagen, and Parker Citation2020), police education (Söderström, Lindgren, and Neely Citation2019), language and literature (Cunningham Citation2017), computer science (D’Mello et al. Citation2012), religion (Ricker et al. Citation2018), mathematics (Smyrnis and Ginns Citation2016) and the 66 articles situated in teacher education. The professions, including teacher education, make up a considerable proportion of this (43%). Of the articles published in the period 1992-2020, 48% of them were published in 2017 or later (see ). Fifty countries are represented, but the greatest proportion of the studies were conducted in the United States (92 articles), Australia (40), Canada (25) and the United Kingdom (23). The 247 articles were published in 190 different scientific journals ().

Our results indicate that the amount of research is limited but rapidly increasing in both higher education in general and teacher education specifically. Of the articles published during the period 2001-2020, 50% of those contextualised in teacher education were published in 2017 or later. The increased level of publication signals an increased interest in this area of research in recent years.

Of the 66 articles relating to teacher education, the greater proportion of the studies were conducted in the United States (18), Australia (16), Canada (5) and the United Kingdom (5). These articles were published in 48 different journals. Seven authors are responsible for two articles each, the others for one. The articles reveal a great diversity of theoretical perspectives, methodologies and methods, but limited discussion and knowledge construction across the publications. Qualitative methodologies were the most prominent approach taken to the research (54). There are a few mixed-method studies (10) and only one quantitative study (Stibbards and Puk Citation2011).

Embodied teaching and learning in teacher education

We will now take a more detailed look at the categorised articles situated in teacher education. To ensure transparency and make the diversity visible, we keep the descriptions, formulations and concepts close to those used in the identified articles. The articles use various concepts addressed towards both students and educators. We have chosen to use the terms student teachers and teacher educators to make the text more coherent and readable. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of articles in each category or subcategory. provides an overview of the categorised articles ().

Table 1. Overview of categorised articles situated in teacher education.

Awareness of embodiment (24)

This category contains more than one third of the identified articles. Here we find articles that reveal an awareness of embodiment in teaching and/or learning in teacher education, but where embodiment is not the focus of the research. The articles merely describe it but do not analyse or theorise it. They state the importance of embodiment but the articles’ contribution to knowledge in the field of embodied teaching and learning is limited. The way these articles describe embodiment primarily foregrounds the aspect of cognitive experience. A few of the articles also touch upon sensory and bodily aspects of embodiment (Beard Citation2018; Beals et al. Citation2013; Hinchion Citation2016). On the basis of what they show an awareness of, the articles in this category fall into three subcategories: Embodied learning in becoming a teacher, Preparing student teachers for the classroom through embodied drama and art-based approaches and The embodied work of teaching.

Embodied diversity and discursive experience (19)

This category includes 19 articles divided into three subcategories: (a) gender dimensions of embodiment and dressage, (b) race, ethnicity and culture and (c) (dis)ability, health and illness.

Gender dimensions of embodiment (5) and dressage (1)

Braun (Citation2011) examines teaching as a physical experience, and the ‘teacher body’ emerges as an important element of student teachers’ stories of trying to fit with the new professional environment. The article concludes by arguing for the consideration of gender and body politics in the practice and training of teachers, thus challenging the assumption that professional occupations are essentially ‘disembodied’ and gender neutral (Braun Citation2011). Similarly, Rutherford, Conway, and Murphy (Citation2015) make the case for bringing in the body from the margins of research on teacher education in their article about ‘looking like a teacher’. Drawing on Foucault’s theorisation of the body and his concept of dressage, this article explores learning to embody and fashion teacher identity through dressage as a practice of power and shows how a professional discourse is historically written onto the student teacher’s body (Rutherford, Conway, and Murphy Citation2015). Another study by Brown and Evans (Citation2004) explores the social construction of gender relations in the teaching of physical education and school sports. The perspective they put forward is that the embodied gendered dispositions that student teachers bring into the profession constitute a powerful influence on their professional behaviour. In addition, they draw attention to the part played by male physical education teachers in reproducing gender relations and ideologies (Brown and Evans Citation2004). Addressing the question of what an embodied form of pedagogy in physical education might look like for young women, an article by Lambert (Citation2020) rethinks the educative purpose and potential of the discipline for young women in relation to embodied learning and pleasure (Lambert Citation2020). In an article by Case and Joubert (Citation2020), two teacher educators, in their respective locations as a black cisgender gay man and a white queer masculine-presenting woman, imagine bodies as tools for resistance. Drawing on examples from their teaching experiences of their social justice pedagogies, they locate and attempt to articulate the knowledge in their bodies, stories and emotions. The authors discuss both the implications and possibilities of resistance for teacher preparation classrooms and pedagogy (Case and Joubert Citation2020).

Race, ethnicity and culture (8)

In an effort to better understand the phenomenon of antiracist teaching in the United States, Ohito (Citation2019a) asks what is revealed about this phenomenon by paying attention to women’s knowledge of antiracist teaching. The findings show that the teacher educators’ beliefs about and enactments of antiracist teaching are shaped by their knowledge of the (inter)connections among: (1) race(ism) and family histories, (2) race(ism) and schooling experiences and (3) race(ism) and embodiment (Ohito Citation2019a). In a critical autoethnography of racial body politics in urban teacher education, Ohito (Citation2019b) studies the relationships among whiteness, pedagogy and urban teacher education. The findings underpin the call for urban teacher educators to embrace a pedagogy of embodiment in order to build student teachers’ capacities to teach racially marginalised children and youth (Ohito Citation2019b).

An article by the Asian American researcher Chan (Citation2002) proposes a new paradigm of embodiment for multicultural teacher education. Teachers’ bodily experience of participating in a cultural diversity project is explored and discussed. The author argues that it is necessary to bring the body into teacher education programmes that are committed to preparing and supporting culturally sensitive teachers (Chan Citation2002). On the basis of a study of student teachers engaged in urban field placement in a United State context, Powell and LaJevic (Citation2011) underscore the importance of conceptualising pre-service teaching as an embodied and relational way of knowing and to prepare student teachers to teach a diverse population of students (Powell and LaJevic Citation2011).

Within the context of social studies teacher education in the United States, Hawkman (Citation2020) examines how five white student teachers embodied, wrestled with and resisted whiteness during a social studies methods course. The findings indicate that, despite prolonged attention to antiracism, the participants struggled to disrupt whiteness and white supremacy throughout the duration of the study (Hawkman Citation2020). In an article exploring the findings of two teaching and learning projects in indigenous Australian studies, Mackinlay and Barney (Citation2014) look at the implementation of PEARLS (Political, Embodied, Active and Reflective Learning) in two university courses. PEARL pedagogy aims to enable students to walk away from the classroom as ‘agents of change’ committed to putting their knowing into action for a more socially just world – to know, to feel and to act. The article examines the shift in students’ understanding of indigenous issues, histories and people (Mackinlay and Barney Citation2014). Trout and Basford (Citation2016) explore the practice of one American teacher educator who was teaching mostly white students about systemic forms of oppression. This article offers an inside look into the teacher educator’s practice to show how the educator avoids what they refer to as ‘the shut-down’ and maintains student engagement through a pedagogy of embodied critical care. The findings show how the teacher educator pushes the students to grapple emotionally and intellectually with the issues related to systemic oppression and how this positions students to become change agents (Trout and Basford Citation2016).

An article by Flintoff (Citation2014) contributes to the limited knowledge and understanding of racial and ethnic differences in physical education and seeks to show how race, ethnicity and gender are interwoven in individuals’ embodied, everyday experience of learning how to teach. This article focusses on black and minority ethnic students’ experience of physical education teacher education in the United Kingdom (Flintoff Citation2014).

(Dis)ability, health and illness (6)

Maher, Williams, and Sparkes (Citation2020) explore the preparation of prospective physical education teachers for teaching pupils with disabilities through embodied simulations. The authors argue that such simulations appear to have a positive impact on the prospective teachers’ inclusive pedagogies (Maher, Williams, and Sparkes Citation2020). Another article by Sparkes, Martos-Garcia, and Maher (Citation2019) helps address the paucity of research analysing the physical education experiences of pupils and students with disabilities while also evaluating embodied pedagogy as a tool for better preparing physical education teachers for their role as inclusive educators (Sparkes, Martos-Garcia, and Maher Citation2019). An article by Wrench and Garrett (Citation2015) focuses on the significance of embodied understandings to the emerging subjectivities and pedagogical practices of student teachers undertaking a physical education specialisation. The findings suggest that the participants located themselves in a contemporary narrative of physical education that reinforces assumptions that bodies, subjectivities and lives can be shaped, leaving no space for the aging teacher or one who experiences illness and/or injury (Wrench and Garrett Citation2015).

(Dis)abled embodiment is the subject of an article by Overboe (Citation2001) that seeks to create a space for embodied wisdom through teaching and to show how experience of embodied wisdom enriches education. The article specifically concentrates on Overboe’s embodied wisdom as a person with cerebral palsy, but he advances the notion that embodied wisdom can apply to the embodiment of other people who are not white, heterosexual, non-disabled males. The article emphasises that it is the ‘interactive moment’ between varying individual notions of embodied wisdom that will enrich the classroom (Overboe Citation2001). Yoo’s article of 2017 is a conceptual exploration of the value of illness, bodies and embodied practice in teacher education. It draws on the author’s reflections and practitioner accounts of poor health to investigate the potential for learning from illness (Yoo Citation2017). Raphael, Creely, and Moss (Citation2019) describe and analyse a drama-based inclusive education workshop on disability in initial teacher education. The article states that participatory, affective and embodied approaches in teacher education are highly effective for overcoming barriers and promoting inclusivity (Raphael, Creely, and Moss Citation2019).

Patterns in the category of embodied diversity and discursive experience

The articles in this category challenge the assumptions that professional occupations are essentially ‘disembodied’ and gender, race and (dis)ability neutral. Power relations, systemic oppression, reproduction, resistance and the creation of opportunities for change are addressed, together with the preparation of students for teaching a diverse population of pupils. There are multiple theoretical perspectives found in this category, ranging from Bourdieu’s theory of habitus to literature on critical whiteness studies and critical anti-racist and anti-colonial pedagogy. Critical race theory, feminism, poststructuralist perspectives, feminist phenomenology and embodied phenomenological perspectives are also present. All of the studies are based on qualitative methodologies, and we find case studies, narrative studies, autoethnographies and critical discourse analysis. Methods used include interviews, observations, video recordings, phenomenological writing, document analysis, free written responses, reflective journals and coursework. Some of the articles refer to other articles in the same category or to researchers and articles across categories. This category primarily foregrounds the discursive experience aspect of embodiment.

Practice of embodied teaching (11)

Focussing on embodied knowledge in learning to teach, Mitchell and Reid (Citation2017) report on an empirical inquiry that introduced a theoretically informed practice-based intervention in a teacher education course. A key element of the project was the opportunity for students to use repetition and practice to begin to develop a teaching habitus. In this the authors draw on the work of Bourdieu, which emphasises the corporeal dimensions of habitus. The study reveals significant changes in students’ embodied practice over time. The authors state that attention to what teachers know and believe is essential in initial teacher education, but that on its own this knowledge is insufficient without simultaneous attention to what teachers do (Mitchell and Reid Citation2017).

Inspired by Bourdieu’s theory that habitus or dispositions are unconsciously embodied and therefore require bodily counter-training for change, Fellner and Kwah (Citation2018) examine an activity for transforming student teachers’ communicative habitus. Their findings support the proposition that the experience of a breach in habitus may facilitate dispositional change when embodied sensitising, visible in video recordings, was consciously recognised through reflexivity and explicit pedagogy (Fellner and Kwah Citation2018). Video-enhanced learning environments are also explored in studies by Xiao and Tobin (Citation2018) and Roche and Gal-Petitfaux (Citation2015). Interactive virtual training for student teachers with a focus on gestures (Barmaki and Hughes Citation2018), game-based simulations of teaching (Presnilla-Espada Citation2014) and a role-play parent-teacher conference (Puvirajah and Calandra Citation2015) are the subject of three studies.

An article by Tellier and Yerian (Citation2018) considers the body, gesture and voice as tools of the language teacher, stating that these professional multimodal skills are essential for sharing knowledge and classroom management. From a detailed analysis of video corpus extracts collected during training sessions, the authors show the aspects of these skills that student teachers can improve on (Tellier and Yerian Citation2018). Inspired by arts-based research and performative social science, Winther (Citation2018) shows how artists, researchers and student teachers examine important issues when making the film Dancing Days With Young People together. The research questions examine how somatic awareness, creativity and embodied leadership can be developed through innovative educational processes and how close-to-practice artistic elicitation methods may contribute to both researching and portraying this process (Winther Citation2018). Within the context of a corporeal-expression didactic programme for physical education student teachers, Canales-Lacruz and Arizcuren-Balsco (Citation2019) explored the students’ experiences in corporeal expression sessions in order to better understand factors that can stimulate or inhibit the learning process (Canales-Lacruz and Arizcuren-Balsco Citation2019). Embodiment in voice training is the subject of an article by Vainio (Citation2017). This article discusses the significance of embodiment in corporeal awareness exercises as part of Finnish teacher voice training, preparing students to be able to control and reduce the negative effects of vocal risk factors (Vainio Citation2017).

The articles in the category practice of embodied teaching draw attention to what teachers do, opportunities for development and change and the importance of repetition and training. Such practice takes different forms in the studies, including real world teaching, teaching in video enhanced-learning environments, interactive virtual training and game-based teaching simulation. Common to all the studies is the idea of predefined core practices or ways of teaching that students are meant to acquire and apply. However, it is generally unclear exactly what they are practising, how they practise it and on what grounds. What kinds of embodied practice are valued and why? The theoretical perspectives in this category are diverse, ranging from Bourdieu’s theory of habitus, embodied phenomenological perspectives, practice theory and socio-constructivist theory to theory on instructional design in virtual world and situated cognition. All but one of the studies (Tellier and Yerian Citation2018) introduce an intervention in teacher education and explore the utility of the approach to student learning, using different methods that address student experiences. Methods used include students’ written descriptions, think-aloud videos, observation, questionnaires, scales and interviews. In contrast with the other categories, half of the studies in this category use mixed-method methodologies. None of the articles refer to other articles in the same category. This category primarily foregrounds the aspect of cognitive experience, but several of the studies also touch upon the aspect of bodily experience.

Teaching as embodied practice and intersubjective experience (9)

This category consists of nine articles exploring teaching as embodied practice. Eight of the articles also describe teaching as intersubjective, whereas an article by Bolldén (Citation2016) does not foreground this aspect of embodiment as clearly as the others do.

A meta-level study of embodied knowledge in teaching and learning by Craig et al. (Citation2018) revolves around ‘knowing without words’ and how this largely hidden form of knowledge was present, but unacknowledged, in five educational research projects. The purpose of the study was to show that embodied knowledge is not simply knowledge of the body but knowledge dwelling in the body and enacted through the body. Findings show that embodied knowledge sits at the heart of teaching and teacher education and that high quality teaching, learning and teaching-learning relationships are fully dependent on it. The article thus argues that embodied knowledge should be intentionally integrated into teacher education (Craig et al. Citation2018).

To acquire new insight into the practice of teaching as an embodied activity, Estola and Elbaz-Luwisch (Citation2003) ask what teachers’ stories tell about the voices of bodies and bodily positions in classrooms at schools and universities. The authors emphasise three main implications of their inquiry: (1) teachers’ body voices are simultaneously concrete and culturally bound, (2) teachers’ body voices are moral and emotional and (3) attention to the body is a challenge to both the researcher and the method used (Estola and Elbaz-Luwisch Citation2003).

Teachers’ embodied presence in online teaching is the subject of an article by Bolldén (Citation2016). Its analytical interest lies in analysing what the body looks like and how it is handled in the actual teaching situation. Thus, this article is concerned with professional capability in handling embodiment online. Its findings show that teacher embodiment occurs online and that teachers deliberately use their embodiment and bodily traces online in order to sustain presence and to bring about certain teaching practices (Bolldén Citation2016).

In a collaborative self-study of their developing understanding of embodied pedagogies, Forgasz and McDonough (Citation2017) explore the emotional and embodied dimensions of teaching and learning to teach. They recognise that teaching, learning and pedagogy are always inherently embodied practices. The article examines what the authors have learnt about the nature, value and facilitation of embodied pedagogies. Their study suggests that embodied pedagogies are valuable because of the unique access point to self-understanding that they offer (Forgasz and McDonough Citation2017).

Drawing on the scholarship of the self-study tradition within educational research, Macintyre Latta and Buck (Citation2007) consider teacher knowledge as an important and largely untapped resource for the improvement of teaching. In their article, the role of embodiment within teaching-learning practice is elucidated through educator professional development in action, by articulating the discourse generated within their self-study group. Their findings suggest that our bodies are the reflexive ground of comprehension, confronting vulnerability, seeking accountability to self, negotiating theory as working notions and experiencing the pull of teaching-learning possibilities. The authors foreground the relational and interactive workings of our bodies and state that the locus of education lives in between teacher and learner (Macintyre Latta and Buck Citation2007).

Dixon and Senior (Citation2011) also enter the area of ‘bodily between’ in their article, which is grounded in data gathered during an arts-based teaching project in teacher education. Their article uses images to present traces of embodied pedagogy from the classroom, and in the images the authors see intricate relationships. They argue that it is not only the learning and teaching that are bodily, but the form of the relationship is also bodily, as the body of each extends beyond its apparent boundaries and the connections are felt by others and seen by others (Dixon and Senior Citation2011).

An article by Hunter (Citation2011) relates to one teacher educator’s attempt to embody praxis as a form of academic work, emphasising the importance of the body in learning and teaching. Evidence of praxis in emergence is illustrated through written text and visual artefacts in a modest attempt to interrupt the dominance of written text. The author argues in favour of a more explicit focus on the body in teacher education (Hunter Citation2011).

An article by McMahon and Huntly (Citation2013) reports on narrative research that focuses on two health and physical education teacher educators’ bodies. It explores how their lived embodied experiences have had an impact upon their everyday teaching practice and draws attention to the body’s importance in pedagogical practice. The authors state that acknowledging the body and its importance to teaching remains imperative for all higher education teachers, teachers, student teachers and students (McMahon and Huntly Citation2013). McMahon and Penney (Citation2013) explore the use of narrative as a pedagogical tool in teacher education to engage with student teachers’ embodied experience (their lived body) and the ways in which such experience in turn influences their ‘living bodies’ with regard to what health and physical education are and how this should be taught. The authors argue that locating, acknowledging and positioning student teachers’ bodies is important for all educators to assist in moving students beyond their experience as school students (McMahon and Penney Citation2013).

The articles in the category teaching as embodied practice and intersubjective experience emphasise the centrality of embodied knowledge in teaching and teacher education and that teaching is always inherently embodied. The authors also argue in favour of a more explicit focus on embodiment in teacher education. Several of the articles foreground the ‘bodily between’ – the relational and interactive workings of our bodies – and state that the locus of education lives in between teacher and learner. Two articles (McMahon and Huntly Citation2013; McMahon and Penney Citation2013) also foreground how teacher educators’ individual embodied experiences interweave with everyday teaching practice and how the lived body of students may lead to the recycling of experiences and pedagogy if not addressed. Compared to the other categories, the articles in this category are more similar in terms of theoretical perspectives. They draw primarily on embodied phenomenological perspectives but also on Bourdieu’s theory of habitus and Dewey’s theory of experience, amongst others. They refer to the other articles to a greater extent than do the articles in the other categories. However, their methodologies are diverse, ranging from online ethnographic approach, narrative enquiry and art-based research to self-study methodology. This category primarily foregrounds the aspect of intersubjective experience, apart from the article by Bolldén (Citation2016), which puts the aspect of cognitive experience at the fore.

Learning as sensory and bodily experience (3)

In this category we find three articles addressing learning as a sensory and bodily experience. One is situated in physical teacher education and focusses on the moving body and feelings related to an activity involving movement (Maivorsdotter and Lundvall Citation2009). Its aim was to study how physical education student teachers felt when participating in a ball game and how their feelings related to the movement activity. In the discussion section of the article, the authors suggest that movement activities in physical education are often regarded as technical or instrumental in nature. By taking an aesthetic perspective on embodied learning, however, it is possible to go beyond that impression and show other dimensions of participation in ball games. This may become an important shift away from exploring performance only to studying learning connected to feelings (Maivorsdotter and Lundvall Citation2009).

The second article in this category is situated in tertiary dance education, where embodied activities, experiences and sensations are prominent (Sööt and Anttila Citation2018). The study explores the dimensions of embodiment that appear in oral and written reflections by novice dance teachers generated after having gone through a guided core reflection procedure and how these dimensions appeared. In their article, Sööt and Anttila (Citation2018) discuss how such guided core reflection can be used to support the professional development of novice dance teachers. The authors emphasise that, within the arts, the body is central to the process of inquiry and constitutes a mode of knowing, thus arguing that this aspect gives education in dance, drama, music and the visual arts particular potential for the exploration of embodiment in education (Sööt and Anttila Citation2018).

The third article investigates the immersive and embodied experience of environment and place through children’s literature (Burke and Cutter-Mackenzie Citation2010). This study focusses on the attributes of visual qualities in picture books that encourage sensory, experiential, perceptual, relational, cultural and socially critical investigations of the environments and places featured in the books. Their approach to immersive pedagogical experience privileges the bodily engagement of the learner with the content or subject matter. This approach was informed by the a/r/tographic position on embodiment, which presuppose that sensory and perceptual experience is a valid means of knowing (Burke and Cutter-Mackenzie Citation2010).

The first two articles draw on the work of John Dewey, one in combination with embodied phenomenological perspectives and the third draw on a/r/tography perspectives. Observations, students’ written reflections, video recordings of teaching, interviews and a/r/tograpic approaches have been used. This category of learning as sensory and bodily experience foregrounds the aspect of sensory experience and bodily experiences, as well as the aspect of cognitive experience.

Our analysis indicates that research so far has foregrounded primarily the cognitive and discursive aspects of embodiment, leaving sensory, bodily and intersubjective aspects in the background.

Discussion

Drawing on Bourdieu’s concepts of scientific field and scientific habitus, we have explored embodied teaching and learning as a potential new research field (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Our exploration makes visible the limited, diverse and increased volume of research over the last twenty years. This research reveals multiple understandings of embodiment and a diversity of theoretical perspectives, methodologies and methods that may contribute to reciprocal enrichment. Research on embodied teaching and learning gives the impression that it is rapidly emerging and has the potential to become a research field. It seems to address something fundamental that is valuable across disciplines and subjects in higher education generally and teacher education specifically. Based on the disciplines in higher education that the articles originate from, this field seems to be particularly relevant to educating professionals. This may not be surprising considering their dependency on integrating thinking, being, doing and interacting within their professional practice. However, this emergent field appears fragmented and loosely structured, and there seems to be limited discussion and knowledge-building across publications. Considering that publishing research and participating in ongoing discussions are an important part of participating in a research field (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), an interesting finding is the number of scientific journals involved: 190 unique journals for the 247 articles situated in higher education and 48 journals for the 66 articles situated in teacher education. A related finding is that, with only a few exceptions, each author in both higher education and teacher education is responsible for only one article each. In addition, the articles identified refer to each other only to a limited extent. We recognise that including publications other than peer-reviewed scientific articles might have revealed a higher degree of knowledge-building within and across publications. There may also be relevant empirical research that does not use the concepts of embodied teaching and embodied learning and thus is not included in the present review.

The present review makes visible the need for heightened attention, increased research and knowledge-building. Our review makes the case for establishing an interdisciplinary research field by providing an overview of existing empirical research and by identifying researchers working on relevant topics. To establish and develop embodied teaching and learning as a research field, ongoing communication between researchers and joint knowledge-building through publication in selected scientific journals are crucial. We consider it important to publish in journals that are concerned with teaching so as to contribute to the broader field of education. To include a wider range of topics relevant for further development, we also find it of great importance to open up the field of embodied teaching and learning and make it more visible to a broader community of researchers and practitioners.

The aspects of embodiment (Rodemeyer Citation2018a, Citation2020b) offer a broad and nuanced understanding of embodiment that we find suitable for exploring research in embodied teaching and learning in teacher education. It enables the exploration of certain aspects of embodiment and an awareness of which aspect of embodiment we, and other researchers, are foregrounding. It also makes it possible to explore more systematically the interplay between these various aspects. This is valuable both as a framework for analysis and in the design of research projects.

Within teacher education, the existing empirical research primarily foregrounds the cognitive and discursive aspects of embodiment. We have thus identified a research gap between teaching/learning and sensory, bodily and intersubjective experience. Research that explores the interdependency between different aspects of embodiment is also limited. To deepen our understanding of teaching and learning, we consider it essential to also include sensory, bodily and intersubjective aspects of embodiment.

Conclusion

This qualitative systematic literature review has revealed a growing interest in research on embodied teaching and learning across a wide range of disciplines in higher education. Our findings suggest that embodied teaching and learning has the potential to become an interdisciplinary research field. However, this emerging field appears fragmented, with limited discussion and knowledge-building across publications. In preparing the ground for future research, we propose the aspects of embodiment as a valuable theoretical framework. By our literature review, we aim to inspire researchers, teacher educators and teachers to continue moving this underexplored yet significant field forward.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for being founded through the strategical research programme on professional learning at the University of South-Eastern Norway.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acton, Renae, and Kelsey Halbert. 2018. “Enacting Learning Citizenship: A Sociomaterial Analysis of Reflectivity and Knowledge Negotiation in Higher Education.” Reflective Practice 19 (5): 707–720. doi:10.1080/14623943.2018.1538960.

- Anderson, Vince, Marcia McKenzie, Scott Allan, Teresa Hill, Sheelah McLean, Jean Kayira, Michelle Knorr, Joshua Stone, Jeremy Murphy, and Kim Butcher. 2015. “Participatory Action Research as Pedagogy: Investigating Social and Ecological Justice Learning Within a Teacher Education Program.” Teaching Education 26 (2): 179–195. doi:10.1080/10476210.2014.996740.

- Anderson, Vivienne, Rafaela Rabello, Rob Wass, Clinton Golding, Ana Rangi, Esmay Eteuati, Zoe Bristowe, and Arianna Waller. 2020. “Good Teaching as Care in Higher Education.” Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research 79 (1): 1–19.

- Andrew, Martin, and Oksana Razoumova. 2017. “Being and Becoming TESOL Educators: Embodied Learning via Practicum.” Australian Journal of Language and Literacy 40 (3): 174–185.

- Andrews, Kimber. 2016. “The Choreography of the Classroom: Performance and Embodiment in Teaching.” PhD diss., University of Illinois. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/90528.

- Barmaki, Roghayeh, and Charles E. Hughes. 2018. “Embodiment Analytics of Practicing Teachers in a Virtual Immersive Environment.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 34 (4): 387–396. doi:10.1111/jcal.12268.

- Beals, Fiona Mary, Catherine Braddock, Alison Dye, Julie McDonald, Andrea Milligan, and Ed Strafford. 2013. “The Embodied Experiences of Emerging Teachers: Exploring the Potential of Collective Biographical Memory Work.” Cultural Studies/Critical Methodologies 13 (5): 419–426. doi:10.1177/1532708613496393.

- Beard, Colin. 2018. “Learning Experience Designs (LEDs) in an Age of Complexity: Time to Replace the Lightbulb?” Reflective Practice 19 (6): 736–748. doi:10.1080/14623943.2018.1538962.

- Bolldén, Karin. 2016. “Teachers’ Embodied Presence in Online Teaching Practices.” Studies in Continuing Education 38 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2014.988701.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to a Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Branscombe, Margaret, and Jenifer Jasinski Schneider. 2018. “Accessing Teacher Candidates’ Pedagogical Intentions and Imagined Teaching Futures Through Drama and Arts-Based Structures.” Action in Teacher Education 40 (1): 19–37. doi:10.1080/01626620.2018.1424657.

- Braun, Annette 2011. “Walking Yourself Around as a Teacher: Gender and Embodiment in Student Teachers’ Working Lives.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 32 (2): 275–291. doi:10.1080/01425692.2011.547311.

- Bresler, Liora. 2004. “Prelude” In Knowing Bodies, Moving Minds: Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning, edited by Liora Bresler, 7–11. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Brown, David, and John Evans. 2004. “Reproducing Gender? Intergenerational Links and the Male PE Teacher as a Cultural Conduit in Teaching Physical Education.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 23 (1): 48–70.

- Burke, Katie. 2020. “Virtual Praxis: Constraints, Approaches, and Innovations of Online Creative Arts Teacher Educators.” Teaching and Teacher Education 95: 1–10.

- Burke, Geraldine, and Amy Cutter-Mackenzie. 2010. “What’s There, What If, What Then, and What Can We Do? An Immersive and Embodied Experience of Environment and Place Through Children’s Literature.” Environmental Education Research 16 (3/4): 311–330. doi:10.1080/13504621003715361.

- Canales-Lacruz, Inma, and Eva Arizcuren-Balsco. 2019. “Feelings and Opinions of Primary School Teacher Trainees Towards Corporeal Expressivity, Spontaneity and Disinhibition.” Research in Dance Education 20 (2): 241–256. doi:10.1080/14647893.2019.1572732.

- Case, Alissa, and Ezekiel Joubert. 2020. “Teaching in Disruptive Bodies: Finding Joy, Resistance and Embodied Knowing Through Collaborative Critical Praxis.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 33 (2): 192–201. doi:10.1080/09518398.2019.1681539.

- Chan, Kam Chi. 2002. “The Visible and Invisible in Cross-Cultural Movement Experiences: Bringing in Our Bodies to Multicultural Teacher Education.” Intercultural Education 13 (3): 245–257. doi:10.1080/1467598022000008332.

- Close, Hunter G., and Rachel E. Scherr. 2015. “Enacting Conceptual Metaphor Through Blending: Learning Activities Embodying the Substance Metaphor for Energy.” International Journal of Science Education 37 (5/6): 839–866. doi:10.1080/09500693.2015.1025307.

- Cooper, Amanda B., and Elizabeth J. Tisdell. 2020. “Embodied Aspects of Learning to Be a Surgeon.” Medical Teacher 42 (5): 515–522. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1708289.

- Craig, Cheryl J. 2018. “Metaphors of Knowing, Doing and Being: Capturing Experience in Teaching and Teacher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 69: 300–311. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.09.011.

- Craig, Cheryl J., JeongAe You, Yali Zou, Gayle Curtis, Rakesh Verma, Donna Stokes, and Paige Evans. 2018. “The Embodied Nature of Narrative Knowledge: A Cross-Study Analysis of Embodied Knowledge in Teaching, Learning, and Life.” Teaching and Teacher Education 71: 329–340. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.01.014.

- Cunningham, Catriona. 2017. “Teaching and Learning French: A Tale of Desire in the Humanities.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 16 (2): 127–140. doi:10.1177/1474022215599165.

- De Jaegher, Hanne. 2018. “The Intersubjective Turn.” In The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition: Embodied, Embedded, Enactive and Extended, edited by Albert Newen, Leon De Bruin and Shaun Leon Gallagher, 453–467. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dixon, Mary, and Kim Senior. 2011. Appearing Pedagogy: From Embodied Learning and Teaching to Embodied Pedagogy, Pedagogy, Culture and Society 19 (3): 473–484.

- D’Mello, Sidney, Andrew Olney, Claire Williams, and Patrick Hays. 2012. “Gaze Tutor: A Gaze-Reactive Intelligent Tutoring System.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 70 (5): 377–398. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2012.01.004.

- Duran, Derya, and Christine M. Jacknick. 2020. “Teacher Response Pursuits in Whole Class Post-Task Discussions.” Linguistics and Education 56: 1–15.

- Duran, Derya, and Olcay Sert. 2019. “Preference Organization in English as a Medium of Instruction Classrooms in a Turkish Higher Education Setting.” Linguistics and Education 49: 72–85. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2018.12.006.

- Estola, Eila, and Freema Elbaz-Luwisch. 2003. “Teaching Bodies at Work.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 35 (6): 697–719. doi:10.1080/0022027032000129523.

- Fellner, Gene, and Helen Kwah. 2018. “Transforming the Embodied Dispositions of Pre-Service Special Education Teachers.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 31 (6): 520–534. doi:10.1080/09518398.2017.1422291.

- Flintoff, Anne. 2014. “Tales from the Playing Field: Black and Minority Ethnic Students’ Experiences of Physical Education Teacher Education.” Race, Ethnicity and Education 17 (3): 346–366. doi:10.1080/13613324.2013.832922.

- Forgasz, Rachel, and Sharon McDonough. 2017. “Struck by the Way Our Bodies Conveyed so Much: A Collaborative Self-Study of Our Developing Understanding of Embodied Pedagogies.” Studying Teacher Education 13 (1): 52–67. doi:10.1080/17425964.2017.1286576.

- Fuchs, Thomas. 2016. “Intercorporeality and Interaffectivity.” Phenomenology and Mind 11: 194–209.

- Gannon, Susanne, and Cristyn Davies. 2007. “For Love of the Word: English Teaching, Affect and Writing.” Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education 14 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1080/13586840701235123.

- Griffin, Shelley M. 2015. “Shifting from Fear to Self-Confidence: Body Mapping as a Transformative Tool in Music Teacher Education.” Alberta Journal of Educational Research 61 (3): 261–279.

- Guerrettaz, Anne Marie, Tara Zahler, Vera Sotirovska, and Ashley Summer Boyd. 2020. “We Acted Like ELLs: A Pedagogy of Embodiment in Preservice Teacher Education.” Language Teaching Research. doi:10.1177/1362168820909980.

- Hadjipanteli, Angela. 2020. “Drama Pedagogy as Aretaic Pedagogy: The Synergy of a Teacher’s Embodiment of Artistry.” Research in Drama Education 25 (2): 201–217. doi:10.1080/13569783.2020.1730168.

- Hawkman, Andrea M. 2020. “Swimming in and Through Whiteness: Antiracism in Social Studies Teacher Education.” Theory and Research in Social Education 48 (3): 403–430. doi:10.1080/00933104.2020.1724578.

- Hinchion, Carmel. 2016. “Embodied and Aesthetic Education Approaches in the English Classroom.” English in Education 50 (2): 182–198. doi:10.1111/eie.12104.

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Hunter, Lisa. 2011. “Re-Embodying (Preservice Middle Years) Teachers? An Attempt to Reposition the Body and Its Presence in Teaching and Learning.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (1): 187–200. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.016.

- Hunter, Philippa. 2019. “Problematised History Pedagogy as Action Research in Preservice Secondary Teacher Education.” Educational Action Research 27(5): 742–757. doi:10.1080/09650792.2018.1485590.

- Knutsson, Susanne, Aleksandra Jarling, and Ann-Britt Thorén. 2015. “It Has Given Me Tools to Meet Patients’ Needs: Students’ Experiences of Learning Caring Science in Reflection Seminars.” Reflective Practice 16 (4): 459–471. doi:10.1080/14623943.2015.1053445.

- Kvammen, Anne Cecilie Røsjø, Johanne Karen Hagen, and Stephen Parker. 2020. “Exploring New Methodological Options: Collaborative Teaching Involving Song, Dance and the Alexander Technique.” International Journal of Education and the Arts 21 (7). http://www.ijea.org/v21n7.

- Lambert, Karen. 2020. “Re-Conceptualizing Embodied Pedagogies in Physical Education by Creating Pre-Text Vignettes to Trigger Pleasure ‘in’ Movement.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 25 (2): 154–173. doi:10.1080/17408989.2019.1700496.

- Macintyre Latta, Margaret, and Gayle Buck. 2007. “Professional Development Risks and Opportunities Embodied Within Self-Study.” Studying Teacher Education 3 (2): 189–205. doi:10.1080/17425960701656585.

- Macintyre Latta, Margaret, and Jeong-Hee Kim. 2011. “Investing in the Curricular Lives of Educators: Narrative Inquiry as Pedagogical Medium.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 43 (5): 679–695. doi:10.1080/00220272.2011.609566.

- Mackinlay, Elizabeth, and Katelyn Barney. 2014. “PEARLs, Problems and Politics: Exploring Findings from Two Teaching and Learning Projects in Indigenous Australian Studies at the University of Queensland.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 43 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1017/jie.2014.5.

- Maher, Anthony J., Dean Williams, and Andrew C. Sparkes. 2020. “Teaching Non-Normative Bodies: Simulating Visual Impairments as Embodied Pedagogy in Action.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (5): 530–542. doi:10.1080/13573322.2019.1617127.

- Maivorsdotter, Ninitha, and Suzanne Lundvall. 2009. “Aesthetic Experience as an Aspect of Embodied Learning: Stories from Physical Education Student Teachers.” Sport, Education and Society 14 (3): 265–279. doi:10.1080/13573320903037622.

- McMahon, Jennifer A., and Helen E. Huntly. 2013. “The Lived and Living Bodies of Two Health and Physical Education Tertiary Educators: How Embodied Consciousness Highlighted the Importance of Their Bodies in Their Teaching Practice in HPE.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 38 (4): 31–49. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol38/iss4/3.

- McMahon, Jennifer A., and Dawn Penney. 2013. “Using Narrative as a Tool to Locate and Challenge Pre Service Teacher Bodies in Health and Physical Education.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 38 (1): 115–133. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol38/iss1/8.

- Mitchell, Donna Mathewson, and Jo-Anne Reid. 2017. “(Re)Turning to Practice in Teacher Education: Embodied Knowledge in Learning to Teach.” Teachers and Teaching 23 (1): 42–58. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1203775.

- Morawski, Cynthia M. 2010. “Transacting in the Arts of Adolescent Novel Study: Teacher Candidates Embody ‘Charlotte Doyle’.” International Journal of Education and the Arts 11 (3): 1–23. http://www.ijea.org/v11n3.

- Nguyen, David, and Jay Larson. 2015. “Don’t Forget About the Body: Exploring the Curricular Possibilities of Embodied Pedagogy.” Innovative Higher Education 40 (4): 331–344. doi:10.1007/s10755-015-9319-6.

- Nuttall, Denise. 2018. “Learning to Embody the Radically Empirical: Performance, Ethnography, Sensorial Knowledge and the Art of Tabla Playing.” Anthropologica 60 (2): 427–438. doi:10.3138/anth.2017-0009.

- Ohito, Esther O. 2019a. “Mapping Women’s Knowledges of Antiracist Teaching in the United States: A Feminist Phenomenological Study of Three Antiracist Women Teacher Educators.” Teaching and Teacher Education 86: 1–11.

- Ohito, Esther O. 2019b. “Thinking Through the Flesh: A Critical Autoethnography of Racial Body Politics in Urban Teacher Education.” Race, Ethnicity and Education 22 (2): 250–268. doi:10.1080/13613324.2017.1294568.

- Ørbæk, Trine. 2021. “Å utvikle lærerstudenters profesjonskunnskap gjennom kroppslig læring.” [To Develop Student Teachers’ Professional Knowledge through Embodied Learning.] In Kroppslig Læring: Perspektiver og praksiser [Embodied Learning: Perspectives and Practices], edited by Tone Pernille Østern, Øyvind Bjerke, Gunn Engelsrud and Anne Grut Sørum, 224–236. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Overboe, James. 2001. “Creating a Space for Embodied Wisdom Through Teaching.” Encounter 14 (3): 34–41.

- Pautasso, Marco. 2013. “Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review.” PLoS Computational Biology 9 (7): 1–4.

- Phillips, Donna Kalmbach, and Mindy Legard Larson. 2009. “Embodied Discourses of Literacy in the Lives of Two Preservice Teachers.” Teacher Development 13 (2): 135–146. doi:10.1080/13664530903043962.

- Powell, Kimberly, and Lisa LaJevic. 2011. “Emergent Places in Preservice Art Teaching: Lived Curriculum, Relationality, and Embodied Knowledge.” Studies in Art Education 53 (1): 35–52. doi:10.1080/00393541.2011.11518851.

- Power, Kerith, and Monica Green. 2014. “Reframing Primary Curriculum Through Concepts of Place.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 42 (2): 105–118. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2014.896869.

- Presnilla-Espada, Janet. 2014. “An Exploratory Study on Simulated Teaching as Experienced by Education Students.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 2 (1): 51–63. doi:10.13189/ujer.2014.020106.

- Puvirajah, Anton, and Brendan Calandra. 2015. “Embodied Experiences in Virtual Worlds Role-Play as a Conduit for Novice Teacher Identity Exploration: A Case Study.” Identity 15 (1): 23–47. doi:10.1080/15283488.2014.989441.

- Raphael, Jo, Edwin Creely, and Julianne Moss. 2019. “Developing a Drama-Based Inclusive Education Workshop About Disability for Pre-Service Teachers: A Narrative Inquiry After Scheler and Levinas.” Educational Review: doi:10.1080/00131911.2019.1695105.

- Ricker, Aaron, Jill Peterfeso, Katherine C. Zubko, William Yoo, and Kate Blanchard. 2018. “The Mock Conference as a Teaching Tool: Role-Play and ‘Conplay’ in the Classroom.” Teaching Theology and Religion 21 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1111/teth.12423.

- Robinson, Philip A. 2018. “Learning Spaces in the Countryside: University Students and the Harper Assemblage.” Area 50 (2): 274–282. doi:10.1111/area.12379.

- Roche, Lionel, and Nathalie Gal-Petitfaux. 2015. “A Video-Enhanced Teacher Learning Environment Based on Multimodal Resources: A Case Study in PETE.” Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society 11 (2): 91–110.

- Rodemeyer, Lanei M. 2018a. “Layers of Embodiment: A Husserlian Analysis.” Paper presented at the conference Time, Body, and the Other, Heidelberg, September 13-15, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3lgNkIIHtcQ

- Rodemeyer, Lanei M. 2018b. Lou Sullivan Diaries (1970-1980) and Theories of Sexual Embodiment: Making Sense of Sensing. New York: Springer.

- Rodemeyer, Lanei M. 2020a. “Deep Bodily Learning: Suggestions for Pedagogical Approaches.” Paper presented at the conference Rethinking Physical Education for the Future: Dimensions of Bodily Teaching and Learning. Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo, September 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=atdb7MXyT5k&t=14711s

- Rodemeyer, Lanei M. 2020b. “Philosophical Perspectives on the Body: Possible Theoretical Foundations for Physical Education.” Paper presented at the conference Rethinking Physical Education for the Future: Dimensions of Bodily Teaching and Learning. Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo, September 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=atdb7MXyT5k&t=14711s

- Rutherford, Vanessa, Paul F. Conway, and Rosaleen Murphy. 2015. “Looking Like a Teacher: Fashioning an Embodied Identity Through ‘Dressage’.” Teaching Education 26 (3): 325–339. doi:10.1080/10476210.2014.997699.

- Sanagavarapu, Prathyusha. 2018. “From Pedagogue to Technogogue: A Journey Into Flipped Classrooms in Higher Education.” International Journal on E-Learning 17 (3): 377–399.

- Sheets-Johnstone, Maxine. 2009. The Corporeal Turn: An Interdisciplinary Reader. Charlottesville: Imprint Academic.

- Smyrnis, Eleni, and Paul Ginns. 2016. “Does a Drama-Inspired “Mirroring” Exercise Enhance Mathematical Learning?” Educational and Developmental Psychologist 33 (2): 178–186. doi:10.1017/edp.2016.17.

- Söderström, Tor, Carina Lindgren, and Gregory Neely. 2019. “On the Relationship between Computer Simulation Training and the Development of Practical Knowing in Police Education.” International Journal of Information and Learning Technology 36 (3): 231–242. doi:10.1108/IJILT-11-2018-0130.

- Sööt, Anu, and Eeva Anttila. 2018. “Dimensions of Embodiment in Novice Dance Teachers’ Reflections.” Research in Dance Education 19 (3): 216–228. doi:10.1080/14647893.2018.1485639.

- Sparkes, Andrew C., Daniel Martos-Garcia, and Anthony J. Maher. 2019. “Me, Osteogenesis Imperfecta, and My Classmates in Physical Education Lessons: A Case Study of Embodied Pedagogy in Action.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (4): 338–348. doi:10.1080/13573322.2017.1392939.

- Stibbards, Adam, and Tom Puk. 2011. “The Efficacy of Ecological Macro-Models in Preservice Teacher Education: Transforming States of Mind.” Applied Environmental Education and Communication 10 (1): 20–30. doi:10.1080/1533015X.2011.549796.

- Sutton, Anthea, Mark Clowes, Louise Preston, and Andrew Booth. 2019. “Meeting the Review Family: Exploring Review Types and Associated Information Retrieval Requirements.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 36: 202–222. doi:10.1111/hir.12276.

- Tellier, Marion, and Keli D. Yerian. 2018. “Embodying the Teacher: Incorporating the Physical Self in Language Teacher Education.” Recherche et Pratiques Pédagogiques en Langues de Spécialité - Cahiers de L’Apliut 37 (2): 1–16.

- Trout, Muffet, and Letitia Basford. 2016. “Preventing the Shut-Down: Embodied Critical Care in a Teacher Educator’s Practice.” Action in Teacher Education 38 (4): 358–370. doi:10.1080/01626620.2016.1226204.

- Vainio, Katri-Liis. 2017. “Embodiment in Voice Training: Teacher and Student Perspectives from Voicepilates Course.” CFMAE: The Changing Face of Music and Art Education 9: 63–82.

- Winther, Helle. 2018. “Dancing Days With Young People: An Art-Based Coproduced Research Film on Embodied Leadership, Creativity, and Innovative Education.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17 (1): 1–10.

- Wrench, Alison, and Robyne Garrett. 2015. “PE: It's Just Me: Physically Active and Healthy Teacher Bodies.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 28 (1): 72–91. doi:10.1080/09518398.2013.855342.

- Xiao, Bing, and Joseph Tobin. 2018. “The Use of Video as a Tool for Reflection with Preservice Teachers.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 39 (4): 328–345. doi:10.1080/10901027.2018.1516705.

- Yoo, Joanne. 2017. “Illness as Teacher: Learning from Illness.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 42 (1): 54–68. doi:10.14221/ajte.2017v42n1.4.