ABSTRACT

Institution-wide curriculum change is a costly, time-intensive and politically fraught undertaking. It is a challenge identifying who has responsibility for the curriculum and who is empowered to change it. The unbundling of the traditional tri-partite academic role of teaching, research and service leaves a gap of who in those communities decides what features in the curriculum. Using discourse analysis of curriculum change documentation, this paper analyses the experience of departments in a research-intensive institution undergoing a holistic, large-scale curriculum review. Departments engaged to varying degrees, with associated integration of educational and disciplinary perspectives. Landscapes of practice are used to explore different communities within departments coming together, or not, in the process. The acknowledgement and appreciation of educational expertise alongside disciplinary research-based knowledge is highlighted as a marker for successful adoption of the curriculum review intentions. This paper contributes to the underdeveloped field of curriculum change in higher education.

Introduction

Higher education policy development in England has positioned students and their learning and teaching experience at the ‘heart of the system’ in the past decade (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills [BIS] Citation2011), addressing an imbalanced focus on research. This has included the introduction of a regulator, the Office for Students (OfS) with a remit to ‘to ensure that every student, whatever their background, has a fulfilling experience of higher education that enriches their lives and careers’ (Citation2020) and a national Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) assessing teaching and outcomes for students to mirror the highly influential Research Excellence Framework (REF).

Quality of teaching is a key predictor of student satisfaction (Langan and Harris Citation2019) and the top driver of students positively rating the value of their course (Neves and Hewitt Citation2020). Government policies were developed shifting the burden of tuition fees from the state to students with the aim of creating a competitive market (BIS Citation2016). However, the attempt at developing associated metrics around teaching excellence and student outcomes have been critiqued for not capturing the process or outcomes of excellent teaching (Canning Citation2019; Tomlinson, Enders, and Naidoo Citation2018). Despite government and sector interest and funding in standardising and benchmarking best practice (Gunn Citation2018; Gunn and Fisk Citation2014), the recognition and valuing of excellent teaching happens largely within opaque institutional structures and disciplinary cultures. This is particularly challenging at research-intensive institutions where reward and recognition schemes have traditionally favoured research outcomes.

The curriculum

Tensions between research and teaching play out in the heart of the student experience – in the curriculum. The curriculum can be defined as a process of making choices about educational aims and how to go about realising them (Toohey Citation1999). Individuals’ ideologies and value systems influence their decision-making process in designing and delivering the curriculum (Lattuca and Stark Citation2009). Curriculum design can reveal gaps in the curriculum as written, taught and experienced to the fore (Bernstein Citation2000), breaking down assumptions about identity and community (Billett Citation2006). Orientations to the curriculum vary, including discipline-based emphasis; those linked to professional, personal and social relevance; as well as a ‘systems designed’ focus, based on effective learning systems (Roberts Citation2015). These show the tensions in the prioritisation between content and the delivery process in the curriculum. What is valued by individuals, institutions and disciplines are often bridged through attempts at developing links between research and teaching in the curriculum (Brew Citation2006; Fung Citation2017).

Institution-wide curriculum change is highly contentious and is often used as a vehicle for significant institutional change (Blackmore and Kandiko Citation2012). This can be structural, bureaucratic, cultural as well as in response to budgetary and societal pressures. The intent of the curriculum is reflected in the language and understanding of the change process. However, this complex process is conducted within institutional structures and rarely reported on in the literature. Given the importance of teaching quality to the student experience, this paper explores the tensions between teaching and research expertise in shaping departmental responses to an institution-wide curriculum change process and is part of a wider research and evaluation exercise at a UK-based research-intensive institution.

Landscapes of practice

The higher education curriculum has historically been set by academic staff who research and teach in the relevant department. The traditional tripartite academic role involved research, teaching and service, but with a recurrent call for greater focus on the latter two elements (Fairweather Citation1996; Barnett Citation2005). Research has identified the unbundling of the academic role and an increase in differentiated academic roles in academia (Coates and Goedegebuure Citation2012). This has led to different forms of academic prestige as academic roles become disaggregated and more specialised (Macfarlane Citation2011). Once holistic tasks involving several aspects of an academic's role, such as designing the curriculum, now spread across a range of communities, including research, teaching, digital learning, professional development, and diversity and inclusion teams. This separation is further exasperated by the rise of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary programmes, which cut across disciplinary and departmental communities.

In his influential research Etienne Wenger (Citation1998) identified communities of practice which formed around three features:

| 1. | Mutual Engagement: the community of people share a social connection, and their interactions inform the work they are doing. | ||||

| 2. | Joint Enterprise: also called ‘the domain’; this refers to the aims of the group and the goals negotiated between the participants. | ||||

| 3. | Shared Repertoire: the common language and routines of the community form a shared repertoire, along with the stories and symbols shared by the group. | ||||

In research-intensive institutions, reviewing and redesigning the curriculum involves working across multiple communities, many beyond the institutional structures. Professional, statutory and regulatory bodies accredit degrees, many practice-based subjects include experiences in business and industry, and disciplinary communities network across institutional cultures. However, the teaching role is largely confined within institutional structures, albeit situated in departments across the university. In developing expertise across communities, ‘knowledgeability is a relationship individuals establish with respect to a landscape of practice that makes them recognizable as legitimate actors in complex social systems’ (Omidvar and Kislov Citation2014, 266).

Professionalisation of teaching

Historically, good teaching was done by a disciplinary expert delivering the maximum of relevant knowledge to students (Smith and Tiberius Citation1998-99) and was ‘seen as requiring certain skills in oration, in rhetoric, and in organisation, but little more than these’ (Taylor Citation1999, 52). There is now differentiation between teaching excellence (performance), teaching expertise (gained from experience and reflection) and the scholarship of teaching (Kreber Citation2002). Several facets of teaching expertise (Kenny et al. Citation2017) have been identified:

teaching and supporting learning,

professional learning and development,

mentorship,

research, scholarship, and inquiry, and

educational leadership.

As part of the unbundling of the academic role, institutions have begun to acknowledge the expert teaching role and develop teaching and learning promotion pathways. Progression is important to publicly acknowledge the expertise and worth of the teaching role and not position this as secondary, incidental, or worse, as an option for ‘failed’ disciplinary researchers. There has been a recent growth of pedagogical research, but it is still lacking in prestige (Cotton, Miller and Kneale Citation2018). Teaching-only staff face less respect (Clarke et al. Citation2015) but nonetheless display high levels enthusiasm (Gretton and Raine Citation2017). However, when faced with institutional structures designed primarily to reward disciplinary research, there are challenges in defining roles and developing skill sets for those in teaching-only roles (Bennett et al. Citation2018).

A key aspect of professionalisation is recognition. There are noted issues of power in communities for granting status and legitimacy (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2015). This is particularly important when working across communities who have different aims, goals and recognition and reward schemes. ‘Combining multiple voices can produce a two-way critical stance through a mutual process of critique and engagement in reflection’ (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2015, 18). Reflection is important to understand the boundaries (or lack thereof) across communities. The process of curriculum change brings to the fore the relationship between disciplinary and teaching expertise. This paper adds to research on curriculum studies, embracing contradictions between the curriculum as written, taught and experienced, moving away from over-instrumentalism (Priestley and Biesta Citation2014) to explore how various forms of expertise shape the curriculum.

Context

This study is based in an urban, mid-size, highly devolved research-intensive institution in the UK. The institution is several years into a nine-year curriculum change programme. It is driven by a Learning and Teaching Strategy (hereafter Strategy), focusing on four pillars of: reforming assessment, adopting active and collaborative learning, embracing diversity and inclusion and taking advantage of the possibilities of digital and technology enhanced learning. The thematic changes were supported by a Learning and Teaching job family, including progression and promotion routes based on teaching and educational scholarship. This change mirrored the government's rebalancing of research and teaching functions through the development of the TEF.

An institution-wide approach to change was seen as necessary to bring a wide and disparate collection of courses and departments forward in developing the educational offering of the institution. Departments are diverse in their research and teaching functions and have had considerable autonomy in hiring staff and vary widely in their proportions of staff with teaching responsibilities – from 30 to 60%. This figure is less than half for most departments, highlighting the research-intensive nature of the institution. The proportion of teaching staff who are teaching fellows, those in full-time teaching-based roles, varies from one to 33%, but about one in eight across all departments. These variations reflect how departments are becoming more complex, signifying wider landscapes of practice rather than ‘simple’ well-defined communities.

Departments went through a multi-year curriculum review, with all undergraduate courses across three Faculties aligning modules and credit frameworks, creating space for innovative teaching and new pedagogical approaches, and aligning assessment strategies. The outputs from the change process include internally based Curriculum Redesign Forms, which function as the quality assurance documents detailing the process, decision-making and outcomes of the process. Official external-facing Programme Specifications detail the new curriculum offering for prospective students and function as the contract between students and what the institution will deliver for a given course.

Departments were able to bid for central funding to deliver on implementing the Strategy through freeing up existing disciplinary expertise and hiring in new pedagogic expertise. The process for undergoing change varied across departments, with different committee structures, varying staff roles involved and localised interpretation and translation of the intent of the Strategy into practice. Every department received funding, and this process allowed departments to tailor the funding to their specific contexts and bring communities of expertise together to facilitate ‘connection, engagement, status, and legitimacy’ (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2015, 14).

There were different patterns of recruitment with the funding from the Strategy and how empowered incomers were in impacting the curriculum review process. There were also variations in existing learning and teaching expertise. The variety of newly hired staff are part of the institutional change culture, creating new learning and teaching communities in some departments and changing the educational landscape across the institution. Analysis of the implementation of the Strategy through the curriculum review process shows how different approaches to landscapes of practice and positioning of educational expertise changes departmental communities and the culture of the institution.

Methods

This paper reports on a wider evaluation of institution-wide curriculum change. The focus here is on the analysis of outcomes of an evaluation rubric exploring different departmental approaches to implementing the Strategy. Data is drawn from three sources described above, firstly the Strategy, which set out the guiding principles for the curriculum review process. The second are the Curriculum Redesign Forms, drafted as part of the internal quality assurance process. The final draft of these details the departmental rationale approach to redesigning the curriculum, engagement with stakeholders, how the programme responded to the Strategy and future plans for evaluation. These were internally public presented at institutional quality assurance committees and curriculum development workshops and were available for internal staff evaluation. A specific request was made to analyse the documents for research purposes from the relevant chair of the committee and this was granted. Further, the researchers approached the institutional ethics committee which decided the public nature of the documents meant that formal institutional ethical review approval was not necessary. The last document is the externally facing Programme Specification which acts as a marketing tool and contract for students on describing the course and how it is structured, the format of teaching and assessment and the details of the award for completing the course. We analysed data from 15 undergraduate departments across three Faculties.

A discourse analysis approach is used on the three linked sources to explore the reform process, exploring patterns of language use which ‘embody shifts in perspectives and values’ (Baldwin Citation1994, 128). The Strategy document was first analysed and fed into the development of an evaluation rubric based on its key principles, distilled into the four pillars. Discourse analysis explored the extent to which these principles were adopted in the Curriculum Redesign Forms and Programme Specification documents. A linguistic ethnographic approach was used, which allows for viewing the activities of individuals situated in broader social landscapes (Copland and Creese Citation2015, 13). This exploration of language offers insight into how it is used in practice and how such practices shape wider social processes and vice versa (Rampton et al. Citation2004).

Linguistic ethnography draws on communications processes and how they contribute to broader practice theory (Rampton, Maybin, and Roberts Citation2015). Linguistic ethnography is a broad approach, which includes analysis of ‘authentic data pertaining to language in use, and giving something back to participants’ (Wilson Citation2017, 40). This very much aligns with the practice-based orientation of this research and the wider curriculum reform agenda. A linguistic ethnographic approach allows researchers to explore how ideologies, powerful discourses and departmental and institutional norms unfold and how these phenomena influence the roles of those involved in educational change (Copland and Donaghue Citation2021). This methodology was particularly suited to this study as it enabled the researchers to explore a number of different texts, with different audiences and purposes and draw them together to explore roles within curriculum change more widely.

Evaluation tool

The first phase of discourse analysis led to the development of the evaluation rubric. The core elements of the Strategy were surfaced, with a focus on the four pillars as these were the guiding principles of change initiative. This formed the basis of the evaluation rubric, as we were exploring the degree to which the Strategy was put into practice. The Curriculum Redesign Forms provided insight into the change process, as these documents detailed the departmental response to the Strategy and the specific practices put in place to enact it. Thematic elements were drawn out from the Curriculum Redesign Forms, as this research explores the process of curriculum change, rather than the specific content. The external-facing Programme Specification allowed for analysis into the degree to which the Strategy was put into practice summarising the course on offer to students. Analysis focused on key sections that were relevant to the Strategy and wider curriculum change process.

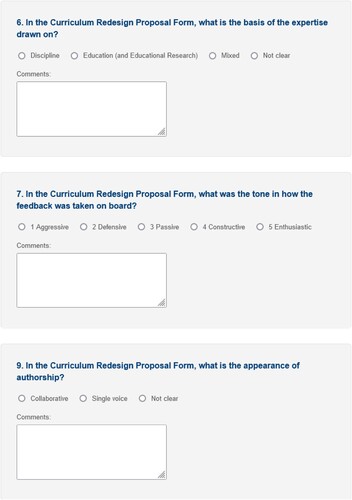

The rubric was divided into four sections. The first explored the degree of engagement with the Language, Intent and Application of the Strategy for each pillar in the Curriculum Redesign Form. The second section contained five questions exploring the change process. The first addressed the basis of the expertise drawn on in the Curriculum Redesign Form (ranging from Discipline; Education and Educational Research; Mixed). The next covered the overall tone (ranging from Aggressive; Defensive; Passive; Constructive; Enthusiastic). The next two covered acknowledging the change process in the Form (Yes, No response) and the appearance of authorship (Collaborative or Single Voice). The last one captured information on the evaluation plans for the department. This led to 15 further indicators, as the Evaluation question covered 11 aspects used across departments including national, institutional, departmental and module level data.

The third section explored the alignment of the Programme Specification with the Strategy, focusing on the Programme Overview; Learning Outcomes; Learning and Teaching Approach; and the Assessment Strategy. The last section of the rubric covered engagement with stakeholders with the same scale leading to two further indicators. In total, the rubric led to 45 indicators. See the full Curriculum Evaluation Rubric in Appendix 1.

This paper reports on the findings of the second section on the change process, specifically the questions on expertise, tone and authorship [see ].

Analysis

Analysis was conducted by two researchers, one closely involved in the review process and one who had no previous engagement. The evaluation rubric was piloted across two departments, with validity confirmed through periodic checks prior to full analysis across all departments. A holistic linguistic approach was taken by several readings of the documents for a single department. This provided a wider context of the department and their engagement with the curriculum change process. Discourse analysis was done through the questions in the rubric. The relevant section was read and categorised in the response options in the rubric. The rubric was completed for each department, with comments for each questions left to illustrate examples, follow up points across documents and raise questions to clarify between the researchers.

The initial analysis focused on sections one and three, exploring the engagement with the pillars of the Strategy in the Curriculum Redesign Form and the Programme Specification, with the scoring on the rubric supporting the categorising of the patterns identified. Previous research identified three clusters of departmental engagement. One-third of the departments were categorised as ‘Active’ and were highly engaged in the curriculum review process. They considered each of the four pillars, providing clear links with the Strategy and applied it in the context of their department. Roughly another third of departments were grouped as ‘Engaged’. These departments engaged with most of the pillars, but with greater focus on the language of the Strategy than the application in the departmental context. A final third were classified as ‘Passive’ with engagement with some pillars completely absent and there was little application of the Strategy proposed in the Curriculum Redesign Forms or evidenced in the Programme Specification.

We report the findings broadly rather than naming specific departments for several reasons. First, this research provides a snapshot in time of an on-going change process, and different departments engaged with the process at different times and thus may be at different points in their trajectory. Further, in this research, we are interested in exploring curriculum change across the institution, not to rank or compare departments with one another – a common occurrence in a highly competitive environment. Thus we report on thematic findings rather than detail specific identifiable roles or content areas. Finally, this research is meant to be developmental, to reflect on the institution's curriculum change journey and to support other institutions undertaking large-scale initiatives.

Findings

Discourse analysis of the curriculum documentation focused on the questions in the change process section on ‘Expertise’, ‘Tone’, and ‘Authorship’ in this paper. It identified patterns of attitudes towards educational change. Unsurprisingly, these patterns largely mapped onto the previously identified three departmental clusters of engagement: Active, Engaged and Passive. These groups present different landscapes to explore the role of voices in the curriculum change process.

Educational expertise

Passages from the Curriculum Redesign Forms feature indicative of text for each of the three categories, shown in . Most of the Active departments drew on a combination of disciplinary and educational expertise, whereas all but two of the Engaged and Passive departments drew primarily on disciplinary expertise, largely focusing on the content and structure of the programme. Integration of the Strategy with the discipline is key, requiring translators, such as recognised, distributed disciplinary pedagogical experts, educational developers and educational technologists. We saw engagement and acknowledgement with translators in the Active departments, with references to educational theory and citations of disciplinary-based pedagogical research in the Curriculum Redesign Forms. These translators had a direct effect on local disciplinary communities and also acted as brokers between wider landscapes of practice (Omidvar and Kislov Citation2014).

Table 1. Analysis of text about expertise.

We also saw the opposite approach, where the Passive departments used funding for new teaching-based staff for mostly discipline-based content delivery, but not teaching design, assessment change or rethinking graduate attributes. And nor was there much engagement with institutional support offered for such activities. Where there was engagement, it was more often in support for the change process rather than with the educational or technological underpinning of actual curricular change.

Tone

In analysis of the overall tone if the documents, the Active and Engaged departments were positive in tone, with several of the Active departments very enthusiastic about the opportunities for reflection brought on by the curriculum review process. A few praised the institution-wide approach as a necessary catalyst for overdue rethinking and change. Several highlighted the usefulness of working across departments and learning about good practices elsewhere in the institution. However, the Passive departments were more negative, with several being hostile to the process, citing bureaucratic processes, lack of time and support and conflicts with cycles of disciplinary and professional body accreditation cycles (see for a comparison).

Table 2. Analysis of text about tone.

Some departments used the central funding to bring in new pedagogical experts, and also engaged with existing expertise in curriculum review, innovation and operationalisation. Disciplinary pedagogical experts were positioned as brokers negotiating the exchange of knowledge across communities and boundaries (Wenger-Trayner et al. Citation2015). This approach was seen in the use of expert language and curriculum design in the evaluation. This contrasted with departments whose language about the curriculum was rooted in disciplinary content and ways of thinking. This was reflected in departments where the curriculum review team was made up of research-based academics who retained power but did not always have access to evidence-informed pedagogic approaches.

Authorship

The Active and Engaged departments were also more likely to have a collaborative approach to the documentary process, citing specific efforts of teams and staff members and examples of activities already put in place. There were also examples of where existing good practice was being built on and expanded across the curriculum. This collaboration extended beyond the department, with acknowledgement of cooperation and engagement with educational development staff and other professional support departments and experts. The Passive departments were more likely to have a single voice, either representing a single author of the documentation or less involvement across the department in the curriculum change process (see ).

Table 3. Analysis of text about authorship.

Power dynamics between groups emerged along traditional teaching and research divisions and across disciplinary and educational expertise. The select group of individuals brought on through the additional funding offered, and to a lesser extent the whole department, were not always the group of individuals with the pedagogic experience, knowledge, and power to affect change. Particularly some departments used the ‘new’ and existing discipline-based pedagogic expertise in curriculum review, innovation, and operationalisation, while for others the review was more the domain of an existing ‘old guard’ who retained the power but did not always have access to the evidence informed newer pedagogic thinking. This links to local perceptions of the worth or prestige of such activity and the sense of ‘agency’ to design and affect real change. This might well be said to interact with the power and status of departments and individuals and structures within departments.

Crossing boundaries involves leaving one's own community and engaging with new language, values and policies, foregoing established expertise and professional identity (Wenger-Trayner et al. Citation2015). The power dynamics within communities can undermine knowledge sharing at the boundaries between communities (Roberts Citation2006), as was seen in the Passive departments where the voices of newly hired teaching-based staff did not emerge in the curriculum review process. These departments were examples where communities resist managerial interventions (Waring and Currie Citation2009). The tensions between teaching and research show conflicting identities and tensions between professional groups (Hong and Fiona Citation2009) and challenges in trusting competencies across different communities (Heizmann Citation2011).

Discussion

The educational approach and attitude towards the change process was likely affected by who or what expertise of people that were recruited with the associated curriculum review funding, and how empowered they were. The Active departments were more likely to have recruited quickly in the change process, bringing in both disciplinary and pedagogic expertise. Many in the Engaged group struggled in their recruitment and staff joined the process further along, limiting their impact in the initial phases of planning the new curriculum. The Passive group were more likely to hire discipline-focused staff with less pedagogic experience and expertise who predominately were used to back-fill teaching or to perform review tasks positioned as an unnecessary or unwelcome distraction, allowing the newly hired staff to support the ‘business as usual’ rather than engage with curriculum change and development.

This evaluation exercise highlighted the tension between research and teaching in a research-intensive environment. The process identified how various forms of expertise and position within landscape grant status and legitimacy. Curriculum change, and the associated shifts in funding and authority in departments and across the institution, was an opportunity for transformation in some departments and a retrenchment of existing practices and structures in other departments.

Findings identified the need for engagement and buy-in across departments for successful curriculum change, as the institutional Strategy needs to be translated into disciplinary contexts which can only effectively be done by disciplinary experts. If the change process is only top down, and process focused, when centralised plans are implemented locally, they frequently become stuck mimicking change, reflecting language and concentrating on process rather translating these into application and changed practice.

Strategic drivers

There was a strategic decision to make the funding associated with the curriculum review process competitive following practices in disciplinary research cultures, the milieu in which most staff have experience and expertise. The outcomes of this process played out differently across the three clusters. The Passive departments largely aimed to get the funding and follow a path of least resistance and minimal change. There was some adoption of educational change and innovation but the core discipline was kept separate. They also recruited discipline-focussed staff perhaps with the primary intent of using the funding opportunity to support and extend the existing approaches rather than to enable the new.

The Engaged group went beyond merely following the process but held back on integrating the discipline and adopting disciplinary change. There were noted pockets of enthusiasm in the Engaged group, but disciplinary pedagogical experts and educational development staff were often positioned in support rather than leadership roles. Thus, even when they had a ‘voice’ in the change process this tended to be localised and often associated with the pockets of enthusiasm rather than being empowered to change at a larger scale. The limited voice of the new experts meant that the overall status quo was often not challenged.

In contrast, these roles were valued in the Active group, which treated the review process as an opportunity to prepare ‘a curriculum for the future’. In the Active group the new discipline focussed pedagogic experts linked with existing landscapes of expertise and sometimes with wider landscapes such as external bodies and used their relative institutional naivety to help question and challenge and support change (because they were valued and supported and given ‘voice’) rather than seeing this as a barrier and positioning them in a system where they only really engaged with a few like-minded individuals. This linking across landscapes broadened the pockets of enthusiasm that were found in the engaged group.

Forms of expertise

Analysis of the curriculum review process showcased expertise being utilised, which can be divided into three levels drawing on both research and teaching experience. The first is disciplinary expertise, largely based on research experience and external professional practice. When individuals and teams with disciplinary-based expertise recognised the value of pedagogical expertise they were able to implement the Strategy in a disciplinary context. The second is disciplinary pedagogical expertise, seen in those trained in the discipline but with significant teaching responsibilities or with pedagogic expertise linked with being an experienced teaching practitioner. As brokers in the curriculum review process, they were able to value disciplinary expertise and general educational expertise and say why those without disciplinary knowledge still have a valid perspective to contribute to curriculum change. The third level was pedagogical expertise, identified and valued as separate and worthy in its own right.

Educational expertise was positioned differently in the departmental clusters. In some of the Passive departments there was superficial mimicry of the language of the Strategy, which may over time turn into change. But curriculum control was kept within the existing power frame rather than bringing in new voices. Pedagogic expertise was seen as a barrier in the process. Power was held with the discipline research-based ‘old-timers’, which can inhibit effective learning across a community (Levina and Orlikowski Citation2009). Looking across wider institutional landscapes, rather than single departmental communities, learning and expertise require going beyond competence in specific practices (Farnsworth, Kleanthous, and Wenger-Trayner Citation2016).

The Active third of departments brought the discipline into the change process. They engaged disciplinary expertise and pedagogical expertise from the discipline and educational developers and professional support staff. The various forms of expertise were integrated and linked to disciplinary practices, acknowledging the shift from competence, knowing within a single community of practice, to knowledgeability ‘a person's relations to a multiplicity of practices across the landscape’ (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2015, 13).

Prestige

From documents that we analysed what is valued emerges from the language used. The prestige of educational expertise was positioned in relation to disciplinary expertise. Part of the working across boundaries of these communities was understanding and valuing the role of ‘disciplinary ignorance’, valuing education outside of knowing the discipline and the importance of internal disciplinary pedagogical experts to act in brokerage roles. Taking a social perspective of learning grants the opportunity to define competence and success in navigating landscapes of practice (Farnsworth et al. Citation2016).

Relative prestige is usually positioned in opposition between landscapes of teaching and research, but this analysis shows something different. The tensions exist across the valuing of discipline teaching and discipline research, but also across discipline-based research and pedagogic research. There is an ongoing struggle, both within institutional structures and across the sector in recognising prestige of pedagogical research (Cotton et al. Citation2018). This is at the level of the practitioner looking to improve practice and operationalising the intent of the curriculum, for example through workshops of writing learning outcomes. This also occurs at the strategic level, informing strategic direction, as seen with the influence of Carl Weiman's research on active learning in the Strategy and in shaping the large-scale structure of courses (Citation2019). This highlights the role of how communities are valued in relation to each other, creating economies of meaning (Contu Citation2014) and understanding. The discourse is facilitated across communities, and there can be mutual benefits for both communities, but also in growing the prestige of the spaces between communities, such as pedagogical research.

The study and the processes of curricula review at this scale also revealed evidence of a change in the relative prestige of pedagogic language and skill. This was not even across departments, in departments more ‘resistant’ to change there was a somewhat grudging recognition that pedagogic language and expertise had to be applied to gain the extra funding and reach the minimum standards perceived as necessary to avoid further extra-departmental pressure to change beyond a comfort zone. In these cases, fixed hierarchies control the ability to define competence (Farnsworth et al. Citation2016), limiting the opportunity for growth and interaction across landscapes. In the more engaged departments, there was a sometimes radical change of the relative prestige of pedagogic expertise and qualification with repositioning and promotion of existing faculty and purposeful recruitment and use of new disciple-related pedagogic expertise.

This research adds to the few studies published on evaluating institution-wide curriculum change. It details how different communities can be supported, or constrained, to collaborate. It highlights the importance of valuing roles and expertise in attempting to make change happen in higher education. Further, it uses a practice-based methodology – linguistic ethnography – to explore curriculum change in practice, highlighting the messiness and complexity of institutional change. Institution-wide change involves a series of landscapes of practice learning to communicate, collaborate and compromise to be successful.

Limitations and further research

This study identified multiple levels of situated learning (Pyrko et al. Citation2019), across individuals, communities and departments. In the three clusters of departments identified, all had the potential to transform, but the timing for many was different, indicating transformation as a liminal stage. There may also be a timing effect with those most engaged and prepared able to explicitly show intent in the documentation while perhaps for others the intent to adopt the principles of the Strategy was growing out of the writing and curriculum review process and did not make it into the review documentation. The methodology of discourse analysis offers useful insight into documents at a point in time, but is limited by not exploring the experiences of individuals or the impact of the documents in practice.

Landscapes of practice consist of diffuse competences driven by informal learning processes. It is important to consider how and where to formalise and structure such practices, and how activities fit into reward and recognition schemes throughout careers in academia. Negotiation of landscapes of practice may involve ‘boundary experiences’ for individuals, temporary journeys from professional communities (Clark et al. Citation2017). Future research could address how individual actors experience these communities and landscapes of practice, tensions across communities and how they feel the institution recognises their accomplishments. Further, although promotion structures were put in place to support progression for staff in teaching-based roles, analysis is needed to explore how individuals have navigated these pathways and whether they are matched with the experience, expertise and opportunities that other staff are able to obtain. Finally, analysis was drawn from documentary ethnography of curriculum change, and it remains to be seen how this is embodied in the operationalised curriculum.

Conclusions

Disciplines and departments are becoming more complex landscapes of practice rather than neatly defined communities of practice. The scale and institutional level of the curriculum review process created new landscapes and added relevance and potential in existing landscapes. While the complexity of an institution-wide curriculum change process did produce challenges, it also shifted the whole institutional perspective, setting a higher bar for recognising educational expertise, rather than just praising the keen and willing and identifying those requiring remedial support. As pressures from the REF and TEF lead to more staff being put in teaching-based roles, it will be interesting to track how prestige is granted to such positions.

In changing the relative prestige of educational language, both disciplinary-based and discipline-independent pedagogic expertise were part of changing the landscape of. What the curriculum change process may have created is multiple landscapes of practice, operating at the discipline, departmental and institutional levels. Exploring the interactions of these landscapes, and formations of new ones, in the delivery of the new curriculum is an opportunity for further exploration of the prestige of educational expertise. How these job roles, their value, prestige and recognition fare beyond the institution will be a further measure of their legitimacy (or not). The wider value of educational expertise may also be played out at national levels in how teaching and research are recognised and rewarded across the sector.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baldwin, G. 1994. The student as customer: The discourse of ‘quality’ in higher education. Journal of Tertiary Education Administration 16, no. 1: 125–33. doi:10.1080/1036970940160110.

- Barnett, R. 2005. Reshaping the university: New relationships between research, scholarship and teaching. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Bennett, D., L. Roberts, S. Ananthram, and M. Broughton. 2018. What is required to develop career pathways for teaching academics? Higher Education 75, no. 2: 271–86. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0138-9.

- Bereiter, C., and M. Scardamalia. 1993. Surpassing ourselves. Chicago and La Salle: Open Court.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research and critique. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Billett, S. 2006. Constituting the workplace curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies 38, no. 1: 31–48. doi:10.1080/00220270500153781.

- Blackmore, P., and C.B. Kandiko. 2012. Strategic curriculum change in universities: Global trends. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Brew, A. 2006. Research and teaching. beyond the divide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Canning, J. 2019. The UK Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) as an illustration of Baudrillard’s hyperreality. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 40, no. 3: 319–30. doi:10.1080/01596306.2017.1315054.

- Clark, J., K. Laing, D. Leat, R. Lofthouse, U. Thomas, L. Tiplady, and P. Woolner. 2017. Transformation in interdisciplinary research methodology: The importance of shared experiences in landscapes of practice. International Journal of Research & Method in Education 40, no. 3: 243–56. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2017.1281902.

- Clarke, M., J. Drennan, A. Hyde, and Y. Politis. 2015. Academics’ perceptions of their professional contexts. In Academic work and careers in Europe: Trends, challenges, perspectives, eds. T. Fumasoli, G. Goastellec, and B. M. Kehm, 117–31. Basel: Springer International Publishing.

- Coates, H., and L. Goedegebuure. 2012. Recasting the academic workforce: Why the attractiveness of the academic profession needs to be increased and eight possible strategies for how to go about this from an Australian perspective. Higher Education 64, no. 6: 875–89. doi:10.1007/s10734-012-9534-3.

- Contu, A. 2014. On boundaries and difference: Communities of practice and power relations in creative work. Management Learning 45, no. 3: 289–316. doi:10.1177/1350507612471926.

- Copland, F., and A. Creese. 2015. Linguistic ethnography: Collecting, analysing and presenting data. London: Sage.

- Copland, F., and H. Donaghue. 2021. Linguistic ethnography. In Analysing discourses in teacher observation feedback conferences, eds. F. Copland, and H. Donaghue, 11–33. New York: Routledge.

- Cotton, D.R.E., W. Miller, and P. Kneale. 2018. The Cinderella of academia: Is higher education pedagogic research undervalued in UK research assessment? Studies in Higher Education 43, no. 9: 1625–36. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1276549.

- Department for Business, Innovation & Skills [BIS]. 2016. Success as a knowledge economy: Teaching excellence, social mobility & student choice. (Cm 9258). London: BIS. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/higher-education-success-as-a-knowledge-economy- white-paper.

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills [BIS]. 2011. Higher education: Students at the heart of the system. UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Fairweather, J.S. 1996. Faculty work and public trust: Restoring the value of teaching and public service in American academic life. Needham Heights, MA: Longwood Division, Allyn and Bacon.

- Farnsworth, V., I. Kleanthous, and E. Wenger-Trayner. 2016. Communities of practice as a social theory of learning: A conversation with Etienne Wenger. British Journal of Educational Studies 64, no. 2: 139–60. doi:10.1080/00071005.2015.1133799.

- Fung, D. 2017. A connected curriculum for higher education. London: UCL Press.

- Gherardi, S., D. Nicolini, and F. Odella. 1998. Toward a social understanding of how people learn in organizations: The notion of situated curriculum. Management Learning 29, no. 3: 273–97. doi:10.1177/1350507698293002.

- Gretton, S., and D. Raine. 2017. Reward and recognition for university teaching in STEM subjects. Journal of Further and Higher Education 41, no. 3: 301–13. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2015.1100714.

- Gunn, A. 2018. Metrics and methodologies for measuring teaching quality in higher education: Developing the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). Educational Review 70, no. 2: 129–48. doi:10.1080/00131911.2017.1410106.

- Gunn, V., and A. Fisk. 2014. Considering teaching excellence in higher education: 2007-2013. A literature review since the CHERI Report 2007. HEA Research Series. Higher Education Academy.

- Heizmann, H. 2011. Knowledge sharing in a dispersed network of HR practice: Zooming in on power/knowledge struggles. Management Learning 42, no. 4: 379–93. doi:10.1177/1350507610394409.

- Hendry, G.D., and S.J. Dean. 2002. Accountability, evaluation and teaching expertise in higher education. International Journal of Academic Development 7, no. 1: 75–82. doi:10.1080/13601440210156493.

- Hodson, N. 2020. Landscapes of practice in medical education. Medical Education 54, no. 6: 504–9. doi:10.1111/medu.14061.

- Hong, J.F.L., and O.K.H. Fiona. 2009. Conflicting identities and power between communities of practice: The case of IT outsourcing. Management Learning 40, no. 3: 311–26. doi:10.1177/1350507609104342.

- Kenny, N., C. Berenson, N. Chick, C. Johnson, D. Keegan, E. Read, and L. Reid. 2017. A developmental framework for teaching expertise in postsecondary education. In International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Conference (14–17 October), Calgary, Canada. http://connections.ucalgaryblogs.ca/files/2017/11/CC4_Teaching-Expertise-Framework-Fall-2017.pdf (accessed on November 27, 2017).

- Kreber, C. 2002. Teaching excellence, teaching expertise, and the scholarship of teaching. Innovative Higher Education 27, no. 1: 5–23. doi:10.1023/A:1020464222360.

- Langan, A.M., and W.E. Harris. 2019. National student survey metrics: Where is the room for improvement? Higher Education 78, no. 6: 1075–89. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00389-1.

- Lattuca, L.R., and J.S. Stark. 2009. Shaping the college curriculum: Academic plans in context, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Levina, N., and W.J. Orlikowski. 2009. Understanding shifting power relations within and across organizations: A critical genre analysis. Academy of Management Journal 52, no. 4: 672–703. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.43669902.

- Macfarlane, B. 2011. The morphing of academic practice: Unbundling and the rise of the para-academic. Higher Education Quarterly 65, no. 1: 59–73. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2273.2010.00467.x.

- Neves, J., and R. Hewitt. 2020. Student academic experience survey. Higher Education Policy Institute and Advance HE. York: Advance HE.

- Office for Students. 2020. About us. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/about/our-strategy/.

- Omidvar, O., and R. Kislov. 2014. The evolution of the communities of practice approach: Toward knowledgeability in a landscape of practice—An interview with Etienne Wenger-Trayner. Journal of Management Inquiry 23, no. 3: 266–75. doi:10.1177/1056492613505908.

- Priestley, M., and G. Biestam, eds. 2014. Reinventing the curriculum. London: Bloomsbury.

- Pyrko, I., V. Dörfler, and C. Eden. 2019. Communities of practice in landscapes of practice. Management Learning 50, no. 4: 482–99. doi:10.1177/1350507619860854.

- Rampton, B., J. Maybin, and C. Roberts. 2015. Theory and method in linguistic ethnography. In Linguistic ethnography. palgrave advances in language and linguistics, eds. J. Snell, S. Shaw, and F. Copland, 14–50. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rampton, B., K. Tusting, J. Maybin, R. Barwell, A. Creese, and V. Lytra. 2004. UK Linguistic Ethnography: A Discussion Paper, published at www.ling-ethnog.org.uk.

- Roberts, J. 2006. Limits to communities of practice. Journal of Management Studies 43, no. 3: 623–639. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00618.x.

- Roberts, P. 2015. Higher education curriculum orientations and the implications for institutional curriculum change. Teaching in Higher Education 20, no. 5: 542–555. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1036731.

- Shulman, L.S. 1987. Knowledge and teaching. Harvard Educational Review 57: 1–22. doi:10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411.

- Smith, R.A., and R.G. Tiberius. 1998. -99. “The nature of expertise: Implications for teachers and teaching.”. Teaching Excellence 10, no. 8: 1–2.

- Taylor, P.G. 1999. Making sense of academic life: Academics, universities, and change. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

- Tomlinson, M., J. Enders, and R. Naidoo. 2020. The teaching excellence framework: Symbolic violence and the measured market in higher education. Critical Studies in Education. 61, no. 5: 627–642. doi:10.1080/17508487.2018.1553793.

- Toohey, S. 1999. Designing courses for higher education. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

- Waring, J., and G. Currie. 2009. Managing expert knowledge: Organizational challenges and managerial futures for the UK medical profession. Organization Studies 30, no. 7: 755–78. doi:10.1177/0170840609104819.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger-Trayner, E., and B. Wenger-Trayner. 2015. Learning in a landscape of practice: A framework. In Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning, eds. E. Wenger-Trayner, M. Fenton-O’Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak, and B. Wenger-Trayner, 13–31. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wenger-Trayner, E., M. Fenton-O’Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak, and B. Wenger-Trayner, eds. 2015. Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning. London: Routledge.

- Wieman, C.E. 2019. Expertise in university teaching & the implications for teaching effectiveness, evaluation & training. Dædalus 148, no. 4: 47–78.

- Wilson, N. 2017. Linguistic ethnography. In The Routledge handbook of language in the workplace, ed. B Vine, 40–50. Abingdon, England: Routledge.