ABSTRACT

Activity theory is a relatively young methodology for researching higher education teaching practices. Beyond systemic analyse of workplace activities and their development, activity theory used in its full interventionist capacity can foster practitioners’ transformative agency to initiate practice change. Nevertheless, this is not an easy process. This paper shares activity theory research into the digital teaching activity of anatomy teachers within an Australian university. Using the lens of this project, the paper exposes several methodological dilemmas experienced by the researcher. Beyond the issue of the methodological level of activity theory used, these dilemmas relate to the authentic determination of both the unit of analysis and the object of the activity, the type of intervention (i.e. full Change Laboratory or modified), and the complexity in analysis using a concept-rich theory. Sharing these dilemmas invites further research to examine inherent contradictions in the human activity of conducting activity theory research focussed on university teaching.

Introduction

For investigating teaching activity in higher education, this paper positions activity theory as developmental research and locates the university as a site of workplace learning for teachers. By using activity theory in this form of workplace developmental research focussing on human activity, it follows the Finnish tradition advanced by Yrjö Engeström from the 1980s, as built upon Russian psychology and human development work of Vygotsky, Marx, Leont’ev, and others (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, Citation2001; Bligh and Flood Citation2015). Activity theory in this variant is increasingly referred to by key proponents as ‘cultural-historical activity theory’, to render explicit its rich cultural and historical contexts for understanding how cultural tools and norms, and historical conditions and perspectives, influence the development of a collective work activity (Engeström and Glăveanu Citation2012; Sannino and Engeström Citation2018). For seminal works on the Finnish tradition of activity theory, see Engeström (Citation1987/Citation2015, Citation2001).

Like any methodological approach, activity theory is open to critique. For example, Postholm (Citation2015) critiques a set of articles with a school-based focus, and Bligh and Flood (Citation2017) critique 59 papers using activity theory in higher education contexts. For the latter, Bligh and Flood (Citation2017) demonstrate that activity theory is gaining momentum in higher education research ‘from a low starting point’ to a ‘gradual increase in explicit theoretical usage’ (p.148), and they expose a continuum of methodological levels used from paradigmatic through to post-hoc data analysis.

Compared to activity-theoretical studies that focus on university student learning (e.g. Gedera Citation2016; Westberry and Franken Citation2015), this paper centres on a university teaching activity as the focus of a critical investigation. Research into academic (faculty/teacher) activities in the university workplace includes, for example, academic professional development and teacher induction activities (e.g. Garraway et al. Citation2023; Gilbert Citation2017; Mathieson et al. Citation2023), curriculum design and delivery activities (e.g. Englund Citation2018; Cliff et al. Citation2022), university guideline compliance activities (e.g. achieving web accessibility, Spinuzzi Citation2007), research activities (e.g. Ludvigsen and Digernes Citation2009; Berg et al. Citation2016; Russell Citation2009), and university teaching with technology (e.g. Al-Naabi Citation2023; Blin and Munro Citation2008; Hu and Webb Citation2009; Lee et al. Citation2022).

Formative interventions informed by activity theory, especially Change Laboratory initiatives (e.g. Engeström et al. Citation1996), can support a practitioner teams’ expansive learning. Such developmental learning is different and more horizontal than hierarchical, top-down change/learning processes found in management (Blackler Citation2009; Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015) or in formal student (school/university) learning situations (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, Citation2011). Expansive learning centres on learning for ‘communities as learners’ and ‘on transformation and creation of culture’ (Engeström and Sannino Citation2010, 2). When formative interventionist research is used to support expansive learning within a university workplace setting, activity theory has the potential to foster teachers’ transformative agency. Teachers can analyse activity-related data and activity theory models to become attuned to apparent contradictions within or extending from their activity. Identified contradictions can form stimulus to drive expansive learning and initiate transformative change within the teachers’ collective practice.

This paper shares a formative interventionist project focussed on the digital teaching activity of a team of anatomy teachers in an Australian university. Through sharing this project, the paper aims to recognise various methodological and practical challenges and draw implications for future activity theory researchers, especially for those who focus on universities as workplace sites for critical investigation of higher education teaching practice.

The project

The project questions how university anatomy teachers construct and transform their cultural-historically located teaching practices, and conceive the resultant outcomes, when using digital resources (including video) as tools to mediate learning in the contextual settings of higher education, and to what extent they are content with the existing situation compared to their potential for changing practices that might foster different outcomes. Used as methodology, activity theory informed the research design conducted across two phases. The first phase involved intensive ethnographic fieldwork, as an important part of activity theory interventionist research (Engeström and Glăveanu Citation2012; Engeström and Sannino Citation2012; Lund and Kerosuo Citation2019), to collect activity-related field data for later analysis by the teachers in formative interventionist workshops. The fieldwork focused on the human activity (a relatively new digital teaching activity) by members of a social group (teachers) and their related cultural artefacts (videos, etc.) as they go about their practice, where the tools contribute the nonhuman elements that help shape social actions and practice of culture (Markham Citation2018).

The multi-faceted sites of practice meant the fieldwork ventured into the physical constructs of two campuses (one metropolitan, one regional), various teaching venues and study spaces (including online classrooms), and individual and communal workspaces of the teacher-coordinators (four lead teachers). Fieldwork activities extended to follow ethnographic traces related to the digital teaching activity, and involved community members (other contributing teachers, students) and networked activity systems (students, university administrator). The need for ‘frameworks and techniques that resonate with and work for [complex contexts in the field]’ (Markham Citation2018, 655) meant that the models and principles of activity theory helped to map the ethnographic field. This included identifying who was involved in and who influenced the teachers’ practice, and whether they formed part of the community of the focal activity and/or of boundary activities.

For the second phase, in a series of formative interventionist workshops adapted from the Change Laboratory, the anatomy teacher-coordinators analysed the field data. The teachers questioned and analysed their digital teaching activity and critiqued its composition. They identified conflicts (as manifestations of contradictions, Engeström and Sannino (Citation2011)), and proposed practice-based solutions while envisaging a transformation of their digital teaching practice.

The dilemmas

Drawing upon the digital teaching project, this paper shares several challenges experienced while conducting activity theory transformative interventionist research in higher education. These challenges differentiate from both grand societal challenges (i.e. highly complex fields of activity theory research as per Sannino and Engeström Citation2018), and from the impossibilities or helplessness of a double bind (Engeström and Sannino Citation2011). The methodological challenges were experienced as dilemmas by the researcher, evidenced by hesitations and doubts (Engeström and Sannino Citation2011) during the research project. Each dilemma might be dismissed or denied, or the researcher might make a (limited) reformulation (Engeström and Sannino Citation2011).

The methodological dilemmas that surfaced in this paper include: (1) Activity theory as paradigm versus methodology versus method, (2) Assumed unit of analysis versus protracted discovery of, (3) Authentically versus conveniently attributing the object of the activity, (4) Full Change Laboratory versus modified formative intervention, and (5) Multi-concept analysis versus single-concept analysis. The first is highly relatable to other social science research theories; therefore, it is kept relatively brief. Each dilemma that follows is discussed in relation to activity theory research, how others in the higher education field have addressed this, how it was confronted in the anatomy digital teaching project, and its implications for other researchers.

Dilemma 1: activity theory as paradigm versus methodology versus method

Activity theory can be viewed and applied as ‘a methodology of its own’ (Engeström Citation2016; Sannino and Engeström Citation2018); however, not all researchers clarify their specific methodological purpose for this theory. This is not unique to activity theory and might apply to various other social science theories when they are applied methodologically in research projects. Highlighting this issue helps to establish a methodological base before moving on to more specific dilemmas experienced.

When reviewing a range of activity theory studies, Postholm (Citation2015) found that researchers do not often provide sufficient methodological detail. This can leave the reader to interpret whether activity theory is used as a paradigmatic stance to approach the research, a methodology to inform the research design, as analytical tools to support data collection methods and/or analysis, or as post-hoc analytical tools to interpret the data. For educational investigations, activity theory is more often used as a conceptual analytical lens (Engeström Citation2016) as compared to use as a developed form using formative intervention at its core (Sannino and Engeström Citation2018).

Activity theory, as a somewhat young theory for researching collective human practices within universities, is applied at various methodological levels. When reviewing studies in higher education, Bligh and Flood (Citation2017) found minimal evidence of activity theory used as a paradigm to shape the ‘research design and data interpretation at a strategic level’ (p.142). Further, of the few studies employing activity theory at the paradigmatic level, only a minority of these ‘deploy some activity-theoretical justification for selecting their methodologies’ (p.147). At the methodology level, Bligh and Flood (Citation2017) found that developmental interventionist strategies were less frequent compared to using activity theory for data interpretation. Predominant use for data analysis does imply methodology influence; however, it might alternatively suggest use as an analytical technique at the method level.

In the current research on anatomy digital teaching, the researcher was hesitant to use activity theory as a paradigm due to insufficient evidence in the literature of higher education studies claiming it at the paradigmatic level. This approximates a ‘denial’ response to this dilemma (Engeström and Sannino Citation2011, 375); however, settlement upon using activity theory as a methodology allowed it to significantly inform the project’s key research question, the two-phased research design of fieldwork followed by interventionist workshops, the data collection techniques, analysis, and write-up.

Activity theory as methodology aligned with the researchers’ otherwise qualitative-constructivist paradigmatic stance. By qualitatively examining professional practices, the ‘research [was brought] closer to the practitioners who can use it to improve practice’ (Major and Savin-Baden Citation2011, 646). A constructivist approach emphasised ‘the world of experience as it is lived, felt, [and] undergone by social actors’ (in this case university teachers and networked others), with pluralistic viewpoints and yet sufficiently adaptive ‘to fit purposeful acts of intentional human agents’ (Schwandt Citation1998, 236). While activity theory might align with other paradigms, a constructivist outlook suited the digital teaching project, for example, aligning with the ‘multivoicedness’ principle of activity theory (Engeström Citation2001, 136), where development is influenced by the perspectives of and constructions by multiple participants through cultural and historical viewpoints.

Given the limited evidence of activity theory employed at the paradigmatic level in higher education, compared to more so at the methodology level and more again as a method (e.g. analytical techniques) (Bligh and Flood Citation2017), the research implications point to communicating and justifying the specific methodological level used. This aligns with Yamagata-Lynch’s (Citation2010) call for making explicit the value intended for using the theory and underpins an appeal to higher education researchers who position activity theory as a research paradigm to explicitly claim this position and share their justification(s).

Dilemma 2: assumed unit of analysis versus protracted discovery of

The smallest unit of analysis in activity theory is the activity system, which forms the first principle that Engeström (Citation2001) attributes to the theory. However, determining what structurally comprises an activity system via its constituent components and activity boundaries, let alone its dynamic features such as internal contradictions, can be difficult.

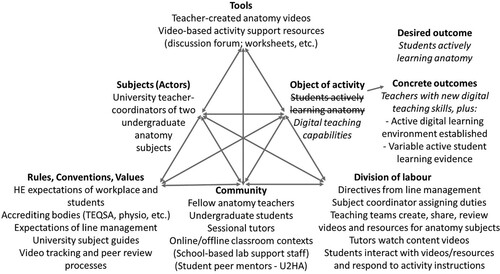

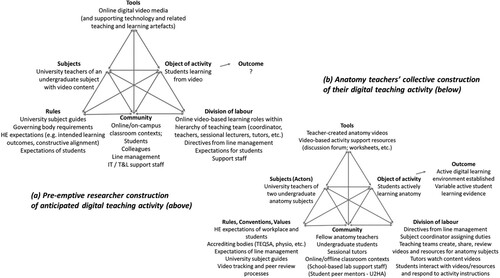

There is much written on first-generation activity theory as an individual-mediated activity, second-generation as a collective-mediated activity constituting an activity system (base unit of analysis), third-generation as two or more networked activity systems (see Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, Citation2001), and an emerging fourth-generation activity theory (Engeström and Sannino Citation2021). A second-generation activity system, in summary, comprises subjects/actors using an artefact/tool to mediate an activity towards achieving an object, in a collective with roles structured via a division of labour, and within this labour, practice rules and cultural conventions apply. One point of difference between the generations, as visually comparable in , involves a singular object that motivates one activity system (second generation) compared to potentially contradictory and ‘partially shared and often fragmented objects’ between ‘multiple interconnected activity systems’ (third generation) (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, xv).

Figure 1. (a) An activity system in second-generation activity theory; (b) Two networked systems in third-generation activity theory.

Given the complexity, authentically attributing the range of structural and dynamic features within single or interacting activity systems is not simple and requires concerted analysis. Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010) critiques descriptions of activities that have omissions and misrepresentations, which fall short of the analysis required of real-life, complex, cultural-historical human activities. A simplistic approach assumes or randomly attributes values to the constituent components of an activity system, and/or accepts the activity boundaries as obvious or natural, rather than determining these through intensive fieldwork, multiple participant voices, and dialectical thinking. An activity system ‘preserves the essential unity and integral quality behind any human activity’, and studying anything less risks oversimplification (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, 65). Additionally, where an activity is represented as static rather than dynamic, it represents its ideal form (Karanasios Citation2018) (e.g. no arrows or other indicators of internal contradictions). In reality, an activity is a complex ‘system possessing structure, inner transformations, conversions, and development’ (Leont'ev Citation1972, 10).

The difficulty of representing a unit of analysis in higher education is illustrated by Paul (Citation2017). Here second-generation activity theory is used to represent unit coordinators (university teachers) as the subjects/actors attributed with the object of ‘Blended Learning Solution’ (p.350). Artefacts of project management documentation comprise the data, and blended learning project coordinators are otherwise implied as the people focussed on the object. The teachers ultimately play a partial role in the blended learning curriculum development before undertaking the delivery. Retrospectively, there appears to be missed opportunities for surfacing teacher insights to clarify the constituent components of the teachers’ activity, and similarly to clarify the networked activity system of the project coordinators, and from this to determine a partially shared object between the networked activity systems.

Comparatively, in another higher education study, Airaj (Citation2024) uses third-generation activity theory to illustrate three interacting activity systems for the respective subjects/actors of human teachers, AI teachers, and students, with attention given to their partially shared objects. In this example, a feature that forms an interesting frontier for the theory in higher education is that the technology of AI is recognised in two ways: AI platforms as tools and AI (non-human) teachers embodied as subjects/actors.

In the current study, the unit of analysis is the digital teaching activity led by a small team of university teachers. Digital teaching here refers to university-level teaching that involves a substantial form of digital mediation. Structurally, the activity system comprises the activity (digital teaching) undertaken by human subjects/actors (university anatomy teacher-coordinators) who are focussed on the object (digital teaching capabilities), as mediated through digital and other tools (video, support technology, related resources). Further, the activity encompasses cultural and historical influences on their teaching practices via university rules and discipline community conventions, and associated divisions of labour. Nevertheless, this activity system was not straightforward to determine, with multiple moments of hesitation and doubt.

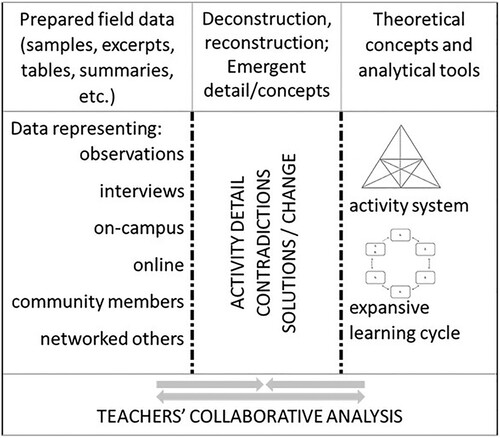

The second- and third-generation triangular models helped to map the field boundaries. However, what comprised the constituent components, and the differentiation between who was in the teachers’ community compared to the networked activity systems, required layers of analysis and multiple reformulations by revisiting the data-theoretical nexus for deeper analysis. First, a pre-emptive unit of analysis devised prior to participant recruitment (see (a)), reveals tool-oriented preconceptions evidenced by overuse of video across the model (i.e. beyond the tool component). This reflects an existing researcher bias towards video (e.g. Colasante Citation2022) via initially privileging video over other factors. During the post-fieldwork workshops, the teacher-coordinators deconstructed and reconstructed their digital teaching activity model (see (b)) which allowed a more credible cultural representation to begin to emerge. However, beyond an introduction to both activity system and expansive learning models, there was no expectation that the teachers held any activity theory expertise. Intensive post-workshop analysis was required to evolve an activity-theoretically informed activity system. In further analysis after leaving the field, fault in the theoretical data interpretation was found in relation to the attributed object (see Dilemma 3) and the activity system overall remains open to critique.

Figure 2. (a) The pre-emptive unit of analysis; (b) The unit of analysis constructed by the teacher-coordinators (notwithstanding networked activities from the university project and the anatomy students).

Misrepresenting a unit of analysis through assumptions can misdirect the analytical process and render it more difficult to arrive at quality findings. In empirical studies, activity systems require intensive examination of collective and dynamic influences and interchanges within and between various systems (Engeström and Glăveanu Citation2012; Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, Citation2001). Activity systems take shape over lengths of time and require protracted examination of data from multiple cultural and historical perspectives to foster fresh insights. While every layer of historical development might be difficult to ascertain, activity analysis should not settle upon one that is convenient for the current inquiry but explore ways of drawing out various historical perspectives (ScribnerCitation1985). If an activity system (including its constituent components and boundaries) is determined too quickly or too easily, there is a risk of establishing an erroneous foundation for an activity theory study. Through intensive fieldwork, agentic input from participating practitioners, and dialectical thinking, the activity composition might be more authentically determined.

Dilemma 3: authentically versus conveniently attributing the object of the activity

The object is often a point of confusion regarding what it means within an activity (Kaptelinin Citation2005; Foot Citation2002; Hardman Citation2007). This might stem from imprecise translation, trailing from Russian origins and links to German philosophy (Kaptelinin Citation2005) and forward to Finnish evolution; or perhaps it reflects the limitations of everyday English language. Certainly, with internationalisation of activity theory within a globalised era, the concept of the object remains difficult to grasp (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015).

Each activity should be ‘primarily determined by its object’ (Leont’ev in Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, 254), that is, one object per activity system. Engeström (Citation1999b, 65) explains the object ‘is to be understood as a project under construction, moving from potential “raw material” to a meaningful shape and to a result or an outcome.’ This raw material or problem space gives the activity direction (Taylor Citation2009), and while some complex activities might involve various subjects/actors focussed upon the same problem space, the object is the singular defining feature of an object-oriented activity system. To further complicate things, an ‘object is inherently contradictory from its beginning’ (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, xxxii). Authentically attributing the object of an activity can be difficult and perplexing.

While not all activity theory studies in higher education teaching indicate the level of difficulty in determining their objects, there are various cases clarifying how direct insights from the teachers as the subjects/actors do inform the object. For one example, Hopwood and Stocks (Citation2008) use survey data from doctoral students as emerging university teachers to attribute their object of ‘teaching practice’, that is, what ‘they are working (or would like to work) on’ given the students’ desire to build teaching skills and experiences (p.190-191). Second, Al-Naabi (Citation2023) uses focus group data from six experienced university teachers to attribute their object of ‘implement online teaching’, given ‘the participating teachers (the subjects) were actively engaged in’ using a technological ‘platform for implementing online teaching and blended learning’ (p. 199-200).

In a comparative higher education example, Hu and Webb (Citation2009) illustrate the complexity of determining the object. They describe the activity of seven experienced university teachers (subjects/actors) who adopt technology into their English for Business Purposes teaching, for the multi-pronged object of ‘students and their learning’ and ‘pedagogical decisions … to establish an ICT rich environment for improved teaching and learning attainment’ (Hu and Webb Citation2009, 146). A networked activity system is implied, that of university management undertaking technology investment and allocation decisions. Given multiple objects indicate multiple activity systems (Karanasios Citation2018), the student-focused, teacher-focussed, and management-focussed objects within the one activity system suggest a potential conflation of activities. Rich data on teacher perspectives are obtained for the activity via interviews and focus group discussions (Hu and Webb Citation2009), although these data are not claimed for gaining teacher insights to clarify the object of the activity.

In the anatomy digital teaching research, the object was initially preconceived as students learning from video (see prior (a)); an assumption made before participant recruitment and again reflecting researcher bias towards video. During teacher questioning and analysis of their activity in the workshops, their object was reconceptualised (yet still misappropriated) as students actively learning anatomy (see prior (b)). This ignored nuances in the teachers’ dialogue. When the teacher-coordinators expressed in the workshops their desired ‘outcome is that the students are actively learning’ (Colasante Citation2021), researcher bias accepted this as a convenient object, denying the teachers’ explicit use of ‘outcome’ over ‘object’. Collegiate feedback subsequently challenged the object as student-activity focussed rather than authentically representing the teachers’ collective object of their activity, which initiated doubt and a further round of analysis.

The object of digital teaching capabilities (see italicised edits in ) shows where the teachers as subjects/actors were directing their attention towards, their problem space under development within the activity. The teachers signalled this focus of attention multiple times in the data, for example, discussing how they collectively ‘dragged [them]selves up and learned some skills’ (Colasante Citation2021). Given an object of an activity can be moulded or transformed into an outcome (Kaptelinin Citation2005; Taylor Citation2009), the teachers did ultimately developtheir digital teaching capabilities; however, they also desired an outcome involving students learning anatomy actively from their digital teaching development efforts (Colasante Citation2021).

Misappropriation of the anatomy teachers’ object as a student-focused one put limitations on subsequent analytical processes. However, once reformulated as a teacher-focused object, deeper implications could be meaningfully analysed. This included studying the granular actions that the teachers collectively took to resolve the conflicts they experienced while building their digital capabilities(see Dilemma 5).

Precedence of misattribution of objects in higher education activities (including the study shared), demonstrates the challenge of authentically discovering an object. While each activity system is principally determined by its object, an object is not necessarily immediately explicit. In a complex activity, a specific object can be difficult to determine until rediscovered through empirical and historical analysis (Engeström Citation2000). Misappropriation or conveniently transposing an object more authentically positioned in a boundary activity system, or researcher subjectivity getting in the way, indicate deeper layers of analysis are required for authentic object identification.

To avoid mistaken and arbitrary attribution of objects, which can damage subsequent analysis, insights from the practitioners (subjects/actors) of the workplace activities are required and the researcher must ‘study the practices by which the objects of work are constructed, [and] to reflect upon associated consequences’ (Engeström and Blackler Citation2005, 310). While an object can prove to be transient through to durable, it deserves detailed analysis (Engeström and Blackler Citation2005) to authentically determine the problem space under focus, the area actually being worked upon by the subjects/actors.

Dilemma 4: Full Change Laboratory versus modified formative intervention

Change Laboratory initiatives, as interventions guided by principles of activity theory and expansive learning (Bligh and Flood Citation2015), involve intensive collaboration by the practitioners to analyse and envision future possibilities for their activity. These interventions provide collaborative space for practitioner-agentic transformations of practice, where practitioners confront activity contradictions as a stimulus to model new solutions to trial between workshop events, and to visualise alternative models for their activity (Engeström et al. Citation1996). A series of ‘successive intervention sessions are carried out on a tight enough schedule to ensure that the discussion continues, and ideas accumulate from session to session’, for practitioners to build their collaborative transformative agency and gain new understandings of their activity and renewed perspectives for its development (Virkkunen and Newnham Citation2013, 10). However, fully fledged Change Laboratory initiatives can be labour intensive.

Activity theorists ‘invite a developmental focus and associate that with interventionism’; nevertheless, ‘intervention-research is uncommon’ in higher education activity theory studies (Bligh and Flood Citation2017, 147, original emphasis). When interventions are employed in a university, they might entail a full Change Laboratory or a modified approach. In one project committed to a full Change Laboratory (Englund Citation2018), 12 interdisciplinary university teachers met across nine fortnightly 90-minute video-recorded sessions, with follow-up sessions conducted after a timelapse. The teachers analysed curricula problem areas to ultimately visualise new ways of working and to collaboratively develop a new pharmacy curriculum.

Comparatively, in a higher education work-integrated learning (WIL) project (Spante et al. Citation2023), the intervention of ‘contradiction analysis workshops’ deviated from a longitudinal Change Laboratory process. Five single workshops were held in various geographical locations with five different sets of participants. This case study-styled approach focussed on identifying contractions within the broad entity of WIL as a pedagogical model. Despite preparedness to move to a full Change Laboratory, the researchers identified this may not be feasible (Spante et al. Citation2023). Regardless, their modified approach suggests a starting mechanism for how to examine a complex entity; potentially to help to define units of analysis to subsequently map the field in preparation for specific activity theory research projects.

In the anatomy digital teaching project, several constraints and compromises created hesitancy towards conducting a full Change Laboratory. The resultant formative interventionist workshops were inspired by the Change Laboratory but designed with several modifications. First, a series of three 90-minute formative interventionist workshops for the anatomy teacher-coordinators over one semester is arguably minimalist in terms of Change Laboratory initiatives (albeit, not unique given at least one researcher has conducted three 90-minute intervention sessions (St. Clair Browne 2011; in Bligh and Flood Citation2015)). Expectations of ‘six to twelve weekly meetings … plus one or two follow-up meetings’ (Engeström and Sannino Citation2010, 12), were considered not achievable with respect to the anatomy teachers’ academic schedules, while three workshops over one semester were accepted by the Human Ethics Committee as a suitable compromise. Nonetheless, the well-established collegiate nature of the anatomy team, along with the nature of at-home ethnography fostering rich interactions during the fieldwork stages, allowed for vocal participant centrality from the first workshop (Colasante Citation2021).

The teachers were active agents in the workshops; agentic practitioners who reviewed the empirical data coupled with their cultural-historical knowledge of their activity (Gale et al. Citation2020). They reviewed their own and others’ constructions as related to their digital teaching activity, including empirical data from their teaching colleagues, students, and a university administrator. They confronted various conflicts and contradictions which formed stimulus for practitioner-led and agentic transformative change and expansive reorganisation of their own practice (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, Citation2004).

Second, in temporal terms, the intervention occurred towards the culmination of an innovation-focused workplace change project that had disrupted the anatomy teachers’ practice. This timing is at odds with typical approaches to activity theory interventions, which occur at the point of facing significant change (Engeström and Sannino Citation2010) rather than towards a settling period. At the time of the workshops, a central university project was concluding that had directed change for several anatomy on-campus subjects/courses, that is, to change to a blended format (a mix of online and on-campus teaching). While the teachers’ new digital teaching activity had begun to stabilise, they recalled an atmosphere of coercion rather than motivation to adopt a model that they felt did not suit anatomy and that they weren’t sufficiently resourced to enact. Despite their uncomfortable experience, or perhaps because of related contradictions manifested, the teachers decided to design their own pedagogical models and find their own resources for their digital teaching activity (Colasante Citation2021).

It could be argued that had a formative interventionist approach been offered at the initial point of the workplace change, the teachers might have experienced agency at the outset. The research under focus occurred late in the digital teaching change process, which aligns with learning opportunities during activity stabilisation periods, while still taking into account previous historical developments and the practitioners’ ‘knowledge and competencies for creation of new stabilities’ (Ludvigsen et al. Citation2011, 110). The workshops ultimately provided the collaborative space for further transformation of the teachers’ digital teaching activity, upon confronting conflicts and contradictions (past and present).

Third, while it was encouraging to witness teacher engagement and progress towards further activity transformation during the workshops, the achievements were more heavily evidenced across the first iterative stages (compared to later stages) of an expansive learning cycle. Using the stimuli of empirical data and models of activity theory, the teachers organically and iteratively moved between the stages of questioning and analysing the data, generating ideas as solutions for trial and experimentation, and reflecting on their practice (Engeström et al. Citation1996). Given the minimal number of sessions, follow up of their post-implementation reflection and consolidation stages was limited to the solutions that the teachers trialled between workshops, and the consolidated transformation of their practice was left to the teachers to enact post-intervention without researcher oversight.

Fourth, not using video in the anatomy teachers’ workshops was atypical to Change Laboratory expectations (and is somewhat ironic given the key activity tool of teacher-generated videos). Video typically has two roles in Change Laboratory initiatives: as a medium to convey empirical data during the workshops, and for videorecording the workshops for subsequent analysis (Moffitt and Bligh Citation2021). Therefore, video can stimulate practitioner reflection, and aid ‘the collection of rich longitudinal data on the actions and interactions’ (Engeström and Sannino Citation2010, 15).

Video was used in the field to record anatomy students interacting with their new digital learning spaces, capturing their hands, laptop screens, and voices, but not their faces to meet agreed human ethics requirements. However, the teachers raised the likelihood of identifying the participating students by their video-captured voices. Loaded with perceived power-imbalance (e.g. when students undertake subsequent anatomy subjects/courses), it was collectively decided to analysis excerpts of student transcripts in the workshops instead of video recordings. Additionally, the workshops were conducted across two campuses using videoconferencing between meeting rooms. Audio recordings of paper artefacts from the workshops seemed a sufficient compromise for analytical needs. The workshop facilitator/researcher took turns to be physically located at each site.

Given the complexity of and time commitment for Change Laboratory initiatives, modifications provide a way to foster practitioner agency and activity outcomes in alternative formats. Yet modifications raise questions of sufficiency. For example, for modifications affecting temporality: are formative interventions that begin post-workplace change still useful once the subjects/actors are stabilising their new activity. The teachers had the potential to further transform their activity given learning can occur at times ‘when you get stabilising out of flux’ (Ludvigsen et al. Citation2011, 110). Nonetheless, to mitigate risks related to timing, consultations with university management when change is occurring (or about to occur) could allow for more timely and full-scale Change Laboratory interventions in higher education. ‘Connecting the process to management’ could facilitate more sufficient time and resource allowances for participant engagement (Bligh and Flood Citation2015, 156, emphasis removed).

Overall, any modifications to Change Laboratory initiatives should not lose sight of the change component. A core part of expansive learning in formative interventions is the potential for motion through agentic change and development in human activity (Hopwood and Sannino Citation2023). The circumstances created for the intervention provided the teachers with imagined distance from their routine practice, to move through past activity patterns and propose alternative future patterns (Miettinen et al. Citation2012), thus moving through historical, present, and envisaged future forms of how their activity might be (Engeström et al. Citation1996) and enabling longitudinal data analysis.

Dilemma 5: multi-concept analysis versus single-concept analysis

As a concept-rich theory, activity theory offers a range of theoretical-analytical tools, which interrelate and can be difficult to both unpack and meld together for the activity under research focus. For example, see Sannino and Engeström (Citation2018) for explanations of how multiple concepts are intertwined with the expansive learning cycle (e.g. Vygotskian double stimulation, ascending from the abstract to the concrete, germ cell determination).

Despite the conceptual complexity, some activity theory studies have an overreliance on simply examining the constituent components of an activity system (Virkkunen and Newnham Citation2013). The models of second- and third-generation activity theory, despite their value for cultural mapping of elements, identifying contradictions, and visualising boundary crossing for ‘analyses of sideways interactions between different actors and activity systems’ (Engeström Citation1987/Citation2015, xxiv) are not the only analytical possibilities.

In higher education contexts, Bligh and Flood (Citation2017) found a high frequency of activity theory-informed data interpretation. However, they found that some studies do not venture beyond categorising and analysing activity system elements and that studies which do refer to other key concepts (e.g. granular operation-action-activity relationships) may not take these concepts substantively into analysis (Bligh and Flood Citation2017).

In the anatomy digital teaching research, the tools and techniques for data analysis were iteratively determined. Engeström’s (Citation1999a, Citation2016) advice on dialectical analysis provided a pivotal role, and various other tools were ‘used both directly and indirectly, as thinking tools, during development processes’ to construct knowledge (Postholm Citation2015, 55). Additionally, advice on ‘thinking with theory’ for ‘analytic practices of thought, creativity, and invention’ supported seeking emergent insights through thinking about theory and data together (Jackson and Mazzei Citation2018, 717). Overall, the process was progressively more challenging as moving through the analytical stages, yet strengthened once doubt was eased around the determination of the unit of analysis (Dilemma 2) and the authentic object (Dilemma 3).

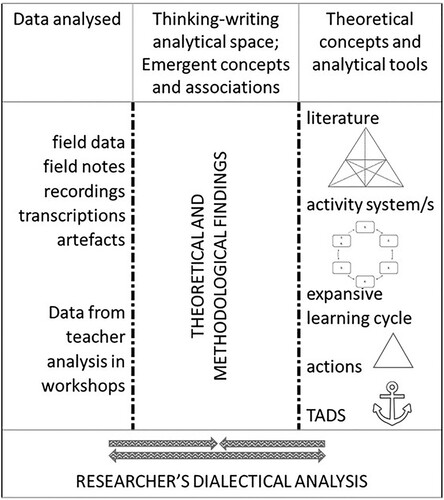

The researcher and the researched carried specific analytical roles. Researcher analysis began in the field, continued pre- and post-workshop, and teacher-coordinator analysis occurred during the workshops. Initial researcher pre-workshop analysis involved preparing excerpts and summaries from the empirical data, to share back with the anatomy teacher-coordinators in the interventionist workshops to ‘stimulate analysis and negotiation between the participants’ (Engeström Citation2009, 328).

During the workshops, the teachers moved between the prepared data and the models of both second-generation activity theory and expansive learning. They engaged collaboratively with these resources, oscillating between them, facilitated by the researcher as principally inspired by Engeström (Citation1999a, Citation2016) and represented by back-and-forth arrows in . The middle column () is somewhat synonymous with the middle ideas pane in a classic Change Laboratory (e.g. Engeström et al. Citation1996). It represents the ideas and concepts emerging from the teachers’ analysis as related to contradictions they experienced and their evolving solutions, leading to visualising and constructing alternative models of their practice.

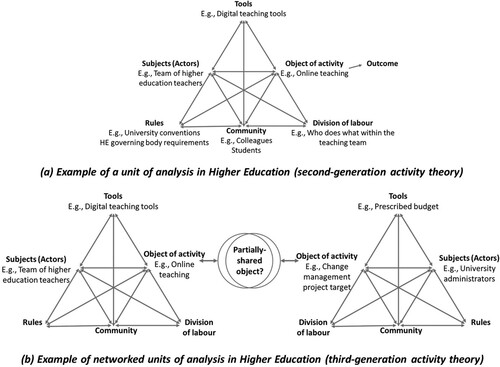

The intensive post-workshop analysis became the methodological responsibility of the researcher to create a ‘bridge between theory and data’ (Engeström Citation2016, viii). To supplement Engeström’s (Citation1999a, Citation2016) dialectical-theoretical thinking analysis process, a key resource outside of activity theory was used, that of ethnographic inbetween writing (Coles and Thomson Citation2016). represents the oscillating thinking-writing process undertaken by the researcher while moving between multiple activity-theoretical tools and the data range, to write and refine a cultural-historical account of the evolving anatomy digital teaching activity. The central column in again indicates emergent detail, the thinking space for the progressive analytical stages. The conceptual tools beyond activity system models and the expansive learning cycle included actions and TADS as detailed below.

Actions, as an activity theory concept in the operation-action-activity hierarchy (Spinuzzi Citation2002; Leont'ev Citation1972), was called upon during researcher analysis. This notion of action emerged somewhat novelly in relation to the activity system under focus. During intensive post-workshop data analysis, various actions towards digital capability became visible that contributed to the overall digital teaching activity. Inspiration to analyse these activity-contributing actions initially came from Sannino’s (Citation2011) call to examine actions. During this analysis, the researcher coined the term auxiliary activity to help illustrate the evolution of activity-contributing actions that ultimately become activities themselves, yet these activities remain auxiliary or subordinate to the focal activity of digital teaching (Colasante Citation2021).

After leaving the sites of anatomy teaching practice, a subsequent round of analysis was inspired by Sannino’s (Citation2015) transformative agency double stimulation (TADS) model. The focus shifted to a deep analysis of teacher-agentic actions that contributed to their transformation processes. Using TADS as represented by a nautical kedge anchor metaphor (Sannino Citation2022; Hopwood et al. Citation2022), this further round of analysis allowed for testing of the TADS framework in a higher education context (Colasante CitationManuscript in preparation). However, for this analysis to be meaningful, the authentic determination of the anatomy teachers’ object was critical (see Dilemma 3).

Realistically, various activity theory concepts might emerge more substantively in some projects over others (e.g. Engeström et al. (Citation2022) analysis of discursive manifestations of contradictions in school-level education). Conversely, the constructs of space limitations in publications may not enable researchers to convey the full range of activity theory concepts examined, with various aspects of a project represented across multiple publications (Bligh and Flood Citation2015, 158). Space limitations might also restrict the ability to detail how analysis was achieved. However, being open to analysing multiple intertwining activity-theoretical concepts that may emerge from the research, using dialectical thinking and thinking with theory models over a timespan, can help to deepen the analytical process. An explicit mapping of publications to specific projects, beyond in-text citations, may be a way forward to bring complex cultural-historical threads together.

Conclusion

As a relatively young methodological approach in higher education teaching research, activity theory has much to offer, irrespective of the challenges inherent in this concept-rich theory and the potential dilemmas experienced. Activity theory is valued as a methodology for critically investigating activities in the university workplace, given its inherent focus on systemic and intensive cultural-historical analysis of collective human activities. When using activity theory for formative interventionist research, there is potential to not only deepen the researchers’ insights into relationships between theory, research, and practice, but to also create an agentic learning environment for teachers. Compared to top-down directives to change practice, designing an activity theory intervention collectively positions participating teachers in the centre of the contestation of ideas, offering to foster transformative agency for those whose workplace practice is under examination. This need not silo teachers from others in university activities at the boundary of and networked to their activity (e.g. students’, colleagues’, leaders’ activities), who can otherwise be represented via ethnographic fieldwork data in interventionist workshops.

Despite valuable research using activity theory, not all papers critique the complex methodological processes. In higher education research, activity theory is more often valorised compared to critiqued, and the theory is more often used for the analytical categorisation of data compared to its potential to underpin formative developmental interventions (Bligh and Flood Citation2017). While some narrower analytical interpretations can add value, there is criticism for using activity theory to solely frame structural elements of an activity without exploring the developmental possibilities (Virkkunen and Newnham Citation2013).

While no doubt other dilemmas might be experienced when using activity theory methodologically in higher education teaching research, those presented in this paper emerge from one researcher’s experiences during one formative interventionist project. The project aimed to understand a university digital teaching activity and to further stimulate agentic transformation in the teachers’ practice. By exposing several researcher-experienced dilemmas through the lens of this project, a critique of methodological and practical approaches in using the theory intends to build upon critical conversations on activity theory while further locating the conversation within higher education contexts. These dilemmas, beyond the issue of activity theory as paradigm/methodology/method, include determining the unit of analysis through protracted discovery versus assumption; authentically versus conveniently attributing the object of the activity; full Change Laboratory versus modified formative intervention; and multi-concept analysis versus single-concept analysis.

Each dilemma presented is open for further critique or building upon by other higher education activity theory researchers. While the hesitation and doubt experienced by the researcher for each of these challenges and attempted reformulations signal them as dilemmas (Engeström and Sannino Citation2011), the marginal corrective steps taken do not necessarily resolve the dilemmas. These issues might be tested in new higher education contexts for further reconceptualisation as contradictions to stimulate transformative actions. Structurally, the research process itself can be viewed as a human activity with its own inherent contradictions, given contradictions exist in most research project communities (Ludvigsen and Digernes Citation2009). Within the dilemmas presented in this paper, various issues were raised that impact methodological processes. These relate, for example, to researcher subjectivity or own object for research competing with the emergent data, and limitations imposed by networked university activities such as conditions agreed upon with human ethics committees on whether to design full or modified Change Laboratory interventions. Overall, the methodological dilemmas that surfaced in this paper might contribute to encouraging the growth and refinement of activity theory research in higher education contexts.

Declaration of interest statement

No known competing financial interests or personal relationships have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Ethics statement

The research project received ethics approval from Deakin University, Faculty of Arts and Education Human Ethics Advisory Group, ID HAE-16-199 Colasante. Informed, voluntary consent was received by all participants prior to data collection.

Acknowledgements

This article builds upon the work of the author's PhD thesis, completed at Deakin University, Australia. The author would like to thank both Professor Damian Blake (principal supervisor and critical peer adviser on this paper) and the article reviewers for their insightful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Airaj, M. 2024. Ethical artificial intelligence for teaching-learning in higher education. Education and Information Technologies 1–23. doi:10.1007/s10639-024-12545-x.

- Al-Naabi, I. 2023. Exploring Moodle usage in higher education in the post-pandemic era: An activity-theoretical investigation of systemic contradictions. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 22, no. 10: 190–208. doi:10.26803/ijlter.22.10.11.

- Berg, D.A.G., A.C. Gunn, M.F. Hill, and M. Haigh. 2016. Research in the work of New Zealand teacher educators: A cultural-historical activity theory perspective. Higher Education Research & Development 35, no. 6: 1125–1138. doi:10.1080/07294360.2016.1149694.

- Blackler, F. 2009. Cultural-historical activity theory and organization studies. In Learning and expanding with activity theory, eds. Annalisa Sannino, Harry Daniels, and Kris D Gutiérrez, 19–39. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Bligh, B., and M. Flood. 2015. The change laboratory in higher education: research-intervention using activity theory. In Theory and method in higher education research, eds. Jeroen Huisman, and Malcolm Tight, 141–168. Bingley: Emerald.

- Bligh, B., and M. Flood. 2017. Activity theory in empirical higher education research: choices, uses and values. Tertiary Education and Management 23, no. 2: 125–152. doi:10.1080/13583883.2017.1284258.

- Blin, F., and M. Munro. 2008. Why hasn’t technology disrupted academics’ teaching practices? understanding resistance to change through the lens of activity theory. Computers & Education 50, no. 2008: 475–490. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2007.09.017.

- Cliff, A., S. Walji, R.J. Mogliacci, N. Morris, and M. Ivancheva. 2022. Unbundling and higher education curriculum: a cultural-historical activity theory view of process. Teaching in Higher Education 27, no. 2: 217–232. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1711050.

- Colasante, M. 2021. Co-constructing digital teaching practice in higher education: An activity theory perspective. Unpublished PhD thesis, Deakin University.

- Colasante, M. 2022. Not drowning, waving: The role of video in a renewed digital learning world. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 38, no. 4: 176–189. doi:10.14742/ajet.7915.

- Colasante, M. Manuscript in preparation. Examining agentic actions: university teachers as a community of learners during systemic digital change.

- Coles, R., and P. Thomson. 2016. Beyond records and representations: inbetween writing in educational ethnography. Ethnography and Education 11, no. 3: 253–266. doi:10.1080/17457823.2015.1085324.

- Engeström, Y. 1987/2015. Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research,2 ed). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Y. 1999a. Communication, discourse and activity. The Communication Review 3, no. 1-2: 165–185. doi:10.1080/10714429909368577.

- Engeström, Y. 1999b. Expansive visibilization of work: An activity-theoretical perspective. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 8: 63–93. doi:10.1023/A:1008648532192.

- Engeström, Y. 2000. Activity theory as a framework for analyzing and redesigning work. Ergonomics 43, no. 7: 960–974.

- Engeström, Y. 2001. Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work 14, no. 1: 133–156. doi:10.1080/13639080020028747.

- Engeström, Y. 2004. New forms of learning in co-configuration work. Journal of Workplace Learning 16, no. 1/2: 11–21. doi:10.1108/13665620410521477.

- Engeström, Y. 2009. The future of activity theory: A rough draft. In In learning and expanding with activity theory, eds. A Sannino, Harry Daniels, and Kris D Gutiérrez, 303–328. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Y. 2011. From design experiments to formative interventions. Theory & Psychology 21, no. 5: 598–628. doi:10.1177/0959354311419252.

- Engeström, Y. 2016. Foreword: making use of activity theory in educational research. In Activity theory in education: research and practice, vii-ix, eds. Dilani S. P Gedera, and P. John Williams. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Engeström, Y., and F. Blackler. 2005. On the life of the object. Organization 12, no. 3: 307–330.

- Engeström, Y., and V. Glăveanu. 2012. On third generation activity theory: interview with Yrjö Engeström. Europe's Journal of Psychology 8, no. 4: 515–518. doi:10.5964/ejop.v8i4.555.

- Engeström, Y., J. Nuttall, and N. Hopwood. 2022. Transformative agency by double stimulation: advances in theory and methodology. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 30, no. 1: 1–7. doi:10.1080/14681366.2020.1805499.

- Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2010. Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings and future challenges. Educational Research Review 5: 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002.

- Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2011. Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts: A methodological framework. Journal of Organizational Change Management 24, no. 3: 368–387. doi:10.1108/09534811111132758.

- Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2012. Concept formation in the wild. Mind, Culture, and Activity 19, no. 3: 201–206. doi:10.1080/10749039.2012.690813.

- Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2021. From mediated actions to heterogenous coalitions: four generations of activity-theoretical studies of work and learning. Mind, Culture, and Activity 28, no. 1: 4–23. doi:10.1080/10749039.2020.1806328.

- Engeström, Y., J. Virkkunen, M. Helle, J. Pihlaja, and R. Poikela. 1996. The change laboratory as a tool for transforming work. Lifelong Learning in Europe 1, no. 2: 10–17.

- Englund, C. 2018. Exploring interdisciplinary academic development: The change laboratory as an approach to team-based practice. Higher Education Research & Development 37, no. 4: 698–714. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1441809.

- Foot, K.A. 2002. Pursuing an evolving object: A case study in object formation and identification. Mind, Culture, and Activity 9, no. 2: 132–149. doi:10.1207/S15327884MCA0902_04.

- Gale, T., R. Cross, and C. Mills. 2020. Researching teacher practice: social justice dispositions revealed in activity. In Practice methodologies in education research, edited by Julianne Lynch, Julie Rowlands, Trevor Gale, and Stephen Parker, 48–62. Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Garraway, J., X. Cupido, H. Dippenaar, V. Mntuyedwa, N. Ndlovu, A. Pinto, and J. Purcell van Graan. 2023. The change laboratory as an approach to harnessing conversation for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development 28, no. 3: 362–377. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2021.2019039.

- Gedera, D.S.P. 2016. The application of activity theory in identifying contradictions in a university blended learning course. In Activity theory in education: research and practice, eds. Dilani S. P Gedera, and P. John Williams, 53–69. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Gilbert, A. 2017. Using activity theory to inform sessional teacher development: what lessons can be learned from tutor training models? International Journal for Academic Development 22, no. 1: 56–69. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2016.1261358.

- Hardman, J. 2007. Making sense of the meaning maker: tracking the object of activity in a computer-based mathematics lesson using activity theory. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT) 3, no. 4: 110–130.

- Hopwood, N., K. Pointon, A. Dadich, K. Moraby, and C. Elliot. 2022. Forward anchoring in transformative agency: How parents of children with complex feeding difficulties transcend the status quo. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 33: 100616. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2022.100616.

- Hopwood, N., and A. Sannino. 2023. Motives, mediation and motion: towards an inherently learning- and development-orientated perspective on agency. In Agency and transformation, eds. Nick Hopwood, and Annalisa Sannino, 1–34. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hopwood, N., and C. Stocks. 2008. Teaching development for doctoral students: what can we learn from activity theory? International Journal for Academic Development 13, no. 3: 187–198. doi:10.1080/13601440802242358.

- Hu, L., and M. Webb. 2009. Integrating ICT to higher education in China: from the perspective of activity theory. Education and Information Technologies 14: 143–161. doi:10.1007/s10639-008-9084-6.

- Jackson, A.Y., and L.A. Mazzei. 2018. Thinking with theory: A new analytic for qualitative inquiry. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, eds. Norman K Denzin, and Yvonna S Lincoln, 717–737. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Kaptelinin, V. 2005. The object of activity: making sense of the sense-maker. Mind, Culture, and Activity 12, no. 1: 4–18. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca1201_2.

- Karanasios, S. 2018. Toward a unified view of technology and activity: The contribution of activity theory to information systems research. Information, Technology & People 31, no. 1: 134–155. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2016-0074.

- Lee, K., M. Fanguy, B. Bligh, and X.S. Lu. 2022. Adoption of online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis of changes in university teaching activity. Educational Review 74, no. 3: 460–483. doi:10.1080/00131911.2021.1978401.

- Leont'ev, A.N. 1972. The problem of activity in psychology. Voprosy filosofii (Problems of Philosophy) 9: 95–108.

- Ludvigsen, S., and T.Ø. Digernes. 2009. Research leadership: productive research communities and the integration of research fellows. In Learning and expanding with activity theory, eds. Annalisa Sannino, Harry Daniels, and Kris D Gutiérrez, 240–254. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Ludvigsen, S.R., I. Rasmussen, I. Krange, A. Moen, and D. Middleton. 2011. Intersecting trajectories of participation: temporality and learning. In Learning across aites: New tools, infrastructures and practices, eds. Sten R Ludvigsen, Andreas Lund, Ingvill Rasmussen, and Roger Säljö, 105–121. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Lund, V., and H. Kerosuo. 2019. The reciprocal development of the object of common space and the emergence of the collective agency in residents’ workshops. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 22: 100327. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100327.

- Major, C.H., and M. Savin-Baden. 2011. Integration of qualitative evidence: towards construction of academic knowledge in social science and professional fields. Qualitative Research 11, no. 6: 645–663. doi:10.1177/1468794111413367.

- Markham, A.N. 2018. Ethnography in the digital internet era: from fields to flows, descriptions to interventions. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, eds. Norman K Denzin, and Yvonna S Lincoln, 650–668. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Mathieson, S., K. Black, L. Allin, H. Hooper, R. Penlington, L. Mcinnes, L. Orme, and E. Anderson. 2023. New academics’ experiences of induction to teaching: using cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) to understand and improve induction experiences. International Journal for Academic Development, 1–15. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2023.2217799.

- Miettinen, R., S. Paavola, and P. Pohjola. 2012. From habituality to change: contribution of activity theory and pragmatism to practice theories. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 42, no. 3: 345–360.

- Moffitt, P., and B. Bligh. 2021. Video and the pedagogy of expansive learning: insights from a researchintervention in engineering education. In Video pedagogy, eds. Dilani Gedera, and Arezou Zalipour, 123–145. Singapore: Springer.

- Paul, A. 2017. Using cultural-historical activity theory to describe a university-wide blended learning initiative. Paper presented at the ASCILITE2017: 34th international conference on innovation, practice and research in the Use of educational technologies in tertiary education, Toowoomba, QLD.

- Postholm, M.B. 2015. Methodologies in cultural–historical activity theory: The example of school-based development. Educational Research 57, no. 1: 43–58. doi:10.1080/00131881.2014.983723.

- Russell, D.R. 2009. Uses of activity theory in written communication research. In Learning and expanding with activity theory, eds. Annalisa Sannino, Harry Daniels, and Kris D Gutiérrez, 40–52. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Sannino, A. 2011. Activity theory as an activist and interventionist theory. Theory & Psychology 21, no. 5: 571–597. doi:10.1177/0959354311417485.

- Sannino, A. 2015. The emergence of transformative agency and double stimulation. Learning, Culture, and Social Interaction 4: 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.001.

- Sannino, A. 2022. Transformative agency as warping: How collectives accomplish change amidst uncertainty. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 30, no. 1: 9–33. doi:10.1080/14681366.2020.1805493.

- Sannino, A., and Y. Engeström. 2018. Cultural-historical activity theory: founding insights and new challenges. Cultural-Historical Psychology 14, no. 3: 43–56. doi:10.17759/chp.2018140304.

- Schwandt, T.A. 1998. The landscape of qualitative research: theories and issues. In Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry, eds. Norman K Denzin, and Yvonna S Lincoln, 221–259. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Scribner, S. 1985. “Vygotsky’s Uses of History.” In Culture, Communication, and Cognition: Vygotskian Perspectives, edited by J. V. Wertsch, 119–145. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Spante, M., J. Garraway, C. Winberg, F. Nofemela, and T.P. Duma. 2023. Cultural historical activity theory as a tool for reimagining WIL: Conducting contradiction analysis workshops and the implications for Change Laboratory work. Bureau de Change Laboratory, Accessed February 2, 2024. https://bureaudechangelab.pubpub.org/pub/cultural-historical-activity-theory-as-a-tool-for-reimagining-wil/release/2.

- Spinuzzi, C. 2002. Toward integrating our research scope: A sociocultural field methodology. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 16, no. 1: 3–32. doi:10.1177/1050651902016001001.

- Spinuzzi, C. 2007. Accessibility scans and institutional activity: An activity theory analysis. College English 70, no. 2: 189–201.

- Taylor, J.R. 2009. The communicative construction of community: authority and organizing. In Learning and expanding with activity theory, eds. A Sannino, H Daniels, and K.D Gutiérrez, 228–239. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Virkkunen, J., and S. Newnham. 2013. The change laboratory: A tool for collaborative development of work and education. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Westberry, N., and M. Franken. 2015. Pedagogical distance: explaining misalignment in student-driven online learning activities using activity theory. Teaching in Higher Education 20, no. 3: 300–312. doi:10.1080/13562517.2014.1002393.

- Yamagata-Lynch, L.C. 2010. Activity systems analysis methods: understanding complex learning environments. New York, NY: Springer.