ABSTRACT

Studies have argued that gridlock in the multilateral trade regime has contributed to processes of regime shifting and creation through the expansion of regional and bilateral agreements. Scholars have long debated the impact of such agreements on the multilateral regime exploring their effect on the incentives of insiders, countries that have signed such agreements, and outsiders, countries that are excluded from such agreements. Based on interviews with officials from sixty member states at the World Trade Organisation, this paper examines this issue by analysing the behaviour of insiders and outsiders in the multilateral trade regime. While analysis of trade and investment diversion might lead us to predict that outsiders will have a stronger interest in the multilateral regime, I find that insiders, particularly middle powers, are key drivers of attempts to end the stalemate in the World Trade Organisation by championing what became known as Joint Statement Initiatives. I explain this position by the systemic support of middle powers to the multilateral regime and by the shift in trade governance towards deep integration issues in which discrimination against outsiders is infeasible or costly.

Introduction

The long-running stalemate in negotiations at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has raised doubts about the ability of the WTO to continue its role as the principal forum for trade governance. Scholars have highlighted how structural shifts in power particularly the rise of emerging economies such as China and India have undermined the ability of the United States, the EU and Japan, to advance their preferred agendas within the WTO (Nariklar Citation2010, Hopewell Citation2016, Stephen Citation2017). In addition, scholars have highlighted how smaller states have succeeded in leveraging institutional sources of power through coalition building to increase their power (Lee and Smith Citation2008, Wilkinson and Scott Citation2008, Eagleton-Pierce Citation2012). In recent years, this WTO gridlock was transformed into a ‘WTO crisis’ by the hostile position of the United States, the country that played the major role in constructing this regime, towards the organisation (Nelson Citation2019). This crisis, however, did not mean that the need for trade governance has declined. On the contrary, growing global interdependencies have raised the need for such governance (Hale et al. Citation2013). This need has expanded as a result of the emergence of new issues with important cross-border implications for trade such as digital trade (Azmeh et al. Citation2020).

The demand for expanding governance, alongside the gridlock in the multilateral regime, has been, it was argued, a driver of processes of forum shifting and regime creation through the proliferation of bilateral and regional trade agreements (Morse and Koehane Citation2014, Urpelainen and Van de Graaf Citation2015). Scholars are divided on the implications of regional and bilateral regimes on the multilateral regime. On the one hand, some have argued that regional and bilateral regimes are stumbling blocs for the multilateral trade regime by creating trade diversion and fragmentation and shifting resources (Limão Citation2007, Bhagwati Citation2008, Hoekman and Sabel Citation2019). Others, however, have argued that regional and bilateral trade agreements provide building blocs for multilateral liberalisation (Wei and Frankel Citation1996, Baharumshah et al. Citation2007, Faude Citation2020, Libman Citation2021). For both positions, the key mechanism of focus is on how bilateral and regional agreements influence the behaviour of insiders, countries that have signed such agreements, and outsiders, countries that are excluded from such agreements. For the ‘stumbling blocs’ argument, the disproportionate gains to insiders make them less likely to seek multilateral liberalisation in order to maintain their gains. For the ‘building blocs’ argument, the negative implications for outsiders becomes the driver for those outsiders to demand multilateral liberalisation to reduce the negative impacts on their economies. In both perspectives, we should expect outsiders to regional and bilateral agreements to support multilateral liberalisation while insiders show less enthusiasm for such liberalisation particularly insiders who have signed bilateral agreements with countries that offer large markets.

This paper examines this issue through analysing the behaviour of insiders and outsiders in the WTO. I focus, in particular, on a number of plurilateral initiatives that became known as joint statement initiatives (JSIs) which have been launched in the WTO since 2017. Based on original data collected from in-depth interviews with officials from sixty member states at the World Trade Organisation, I argue that a key objective of the JSIs is to disrupt the gridlock at the WTO and to limit the divergence between the multilateral regime and regional and bilateral regimes. Contrary to conventional predictions that outsiders to regional and bilateral regimes will drive such effort, I find that insiders to regional and bilateral regimes have, particularly in the context of US hostility towards the WTO, stepped in to play an important role in leading these initiatives. In particular, I find that insiders who have entered deep integration agreements with some of the three largest markets (the United States, the EU, and China) are highly supportive of the JSIs. This support is particularly evident in the position of middle powers such as South Korea, Canada, Singapore, Japan, and Australia, who are driving the JSI agenda. From a trade and investment diversion lens, the enthusiasm by those insiders for advancing multilateral processes is surprising. Why would countries who have secured preferential relationships with large economic powers erode this privileged position by advancing multilaterlisation? I offer an explanation that focuses on two factors. First, middle powers show strong systemic support to the multilateral regime as a result of the smaller size of their economies and the power asymmetry they face in their bilateral relationships with the more powerful economies. Second, the shift in trade governance towards deep integration areas in which discrimination against outsiders is infeasible or costly, what most JSIs focus on, means that middle powers, having incurred the costs involved in negotiating and implementing these rules in regional and bilateral agreements, find little future bargaining value in withholding such benefits from other countries and focus instead on the opportunities of expanding those rules to a wider set of countries through the multilateral regime. These two factors are intertwined. The relatively smaller size of middle powers and their lack of the resources and leverage needed to exploit the opportunities created by the new rules bilaterally or regionally with the rest of the world make the multilateral framework an attractive arena for them to disseminate these rules globally particularly through working together to advance their agenda in the WTO and to compensate for the declining interest of some of the major powers in the WTO.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. Section two examines the relationship between regional and bilateral agreements and the multilateral regime. Section three discusses middle powers and regional and bilateral trade regimes. Section four provides an overview of the JSIs and the role of middle powers in advancing them. Section five explains the role of middle-power insiders in the JSIs. Section six concludes.

This paper is based on research conducted in Geneva in 2021 and 2022 and included interviews with trade officials (ambassadors or counsellors) from sixty WTO member states. Geneva missions are the ‘eyes and ears’ of capitals on WTO processes and provide recommendations that often drive decisions by national governments. Many of Geneva staff are closely involved in negotiating bilateral and regional trade agreements which enable them to compare and discuss the two forums. This research in Geneva was followed by ten in-depth virtual interviews in 2022 and 2023 with capital-based officials from some of the middle power insider countries I examine in more detail. Those interviews aimed to develop the findings from Geneva and to deepen my understanding of the factors driving the support of those countries to the JSIs particularly in relation to bilateral and regional agreements. Findings from these interviews were triangulated with public statements and submissions related to the JSIs including communications from WTO members and discussions in the WTO General Council.

Insiders and outsiders: bilateral and regional agreements and the multilateral trade regime

The relationship between regional and bilateral trade agreements and the multilateral trade regime has been contested by scholars in different disciplines, particularly trade economics and international political economy. This research has been dominated by two points of view: The first argues that regional and bilateral agreements contribute to multilateral liberalisation while the second argues that regional and bilateral agreements undermine the multilateral regime.

A number of scholars have argued that regional and bilateral trade agreements undermine the multilateral system through creating a ‘spaghetti bowl’ of rules that create fragmentation and trade diversion and shift resources from the multilateral system (Limão Citation2007, Bhagwati Citation2008, Krishna Citation2013, Hoekman and Sabel Citation2019). Scholars have highlighted how trade diversion is harmful for economies outside those agreements as it reduces their exports and create new obstacles for their trade (Chang and Winters Citation2002, Fugazza and Nicita Citation2013, Krishna Citation2013, Baccini et al. Citation2017). Chang and Winters (Citation2002), for example, found that the creation of the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) was associated with significant declines in the prices of non-members exports to the region. Similarly, Romalis (Citation2007) found that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) agreement increased North American output and prices in many highly protected sectors by driving out imports from non-member countries. Examining preferential agreements implemented in 1990–2002, Anderson and Yotov (Citation2016) found a sizeable gain for member and a loss, albeit small, for non-members. Baccini et al. (Citation2017) found that preferential trade liberalisation with the United States has led to market concentration in partner countries. In addition to trade, some studies have highlighted the investment diversion impacts that result from such agreements (Cardamone and Scoppola Citation2012, Baccini and Dür Citation2015, Zahid et al. Citation2021).

These gains for insiders and loss for outsiders drive what some scholars have called the exclusion incentive (Lake & Krishna Citation2019). This exclusion incentive is often seen as the key mechanism by which regional and bilateral agreements undermine multilateral liberalisation as insiders to regional and bilateral agreements opt to keep their gains within the regional and bilateral regime (Levy Citation1994, Krishna Citation1998, Lake and Krishna Citation2019, Wang et al. Citation2020). Major powers, it has been argued, also have limited incentives to reduce their multilateral tariff rates as those rates provide them with high leverage in bilateral and regional negotiations (Limao Citation2006). Other studies, however, have argued that such an effect depends on the size of the gains from regional and bilateral agreements and if those gains are so large for insiders that a multilateral agreement becomes undesirable (Freund and Ornelas Citation2010).

The exclusion incentive, nonetheless, is also a key mechanism for scholars who argued that bilateral and regional agreements are building blocs towards multilateral liberalisation. The domino theory of regionalism proposed by Baldwin (see Baldwin Citation1993, Baldwin Citation2006, Baldwin and Jaimovich Citation2012) argues that the formation of a bilateral and regional trade agreements drives negative impacts on exporters in third countries and triggers a political conflict between pro-membership forces who gain if the nation joins and anti-membership forces who are associated with import-competing industries that would lose from such liberalisation. If a decision to join emerge as a result of this conflict, the expansion of the bilateral or regional agreement leads to deeper discrimination against other third countries who remained outside the agreement resulting in the continuous expansion and ultimately the ‘multilateralisation of regionalism’ (Baldwin Citation2006, Baldwin and Jaimovich Citation2012). While the focus in Baldwin’s work has been on how this mechanism leads to outsiders seeking membership in bilateral and regional agreements, another possibility is that outsiders will seek multilateral liberalisation particularly if they are not invited to join the regional or bilateral agreement (Takamiya Citation2019).

One of the key contested issues in this debate is that of free riding (Lake and Krishna Citation2019). Some studies have found that regional and bilateral agreements drive lower external barriers by members (Bohara et al. Citation2004, Ornelas Citation2005a, Estevadeordal et al. Citation2008). As such, rather than drive outsiders to seek membership or multilateral liberalisation, they might allow them to benefit from those agreements without paying any costs (Ornelas Citation2005b, Freund and Ornelas Citation2010). The expansion of deep integration in trade agreement has complicated this relationship as the ability to discriminate between insiders and outsiders in those areas is less clear and the possibility of positive spillovers to non-members is higher (Hofmann et al. Citation2017, Lake and Krishna Citation2019, Mattoo et al. Citation2022). Such shifts have led some scholars to argue that the earlier framework of analysing the relationship between regional/bilateral agreements and the multilateral regime are outdated and incapable of explaining these processes in today’s world economy (Baldwin Citation2011).

Overall, the literature on the relationship between bilateral and regional agreements and the multilateral regime is complex and inconclusive. The two perspectives outlined above disagree on the outcome but agree on the mechanism; that the exclusion incentive is the key driver of the implications of bilateral and regional agreements for the multilateral regime. In both perspectives, we should expect outsiders to regional and bilateral agreements to support multilateral liberalisation while insiders would be less eager. While further quantitative research might shed light on these questions, it faces a number of methodological barriers due to the limited ability to account for counterfactuals and limitations to correlations and case studies (Freund and Ornelas Citation2010). As such, qualitative research might provide us with important insights by examining the behaviour of insiders and outsiders in the multilateral trade regime: Do insiders to regional and bilateral agreements show limited enthusiasm for further multilateralism? And do outsiders show stronger enthusiasm for the multilateral regime? And how do officials from both groups explain their policies?

Middle powers in regional and bilateral trade agreements

While the literature on international political economy is dominated by analysis of the behaviour and motivations of large powers such as the United States, the EU, and China, the concept of middle powers has been used by scholars to move beyond the dichotomy of ‘North-South’ in international economic governance (Lee Citation2022). No consensus exists on the definition of middle powers with different strands of this literature focusing on behaviour as a key determinant of middle powers while others focus on material resources such as state capacity (Jordaan Citation2003, Efstathopoulos Citation2018). Reflecting these varying definitions, the concept of middle power has been applied to a relatively large number of countries including Australia (Beeson and Higgott Citation2014), Canada (Gecelovsky Citation2009), Brazil (Selcher Citation2019), South Africa (Schoeman Citation2015), South Korea (Karim Citation2018, Lee Citation2022), Singapore (Lam Citation2022), Thailand (Freedman Citation2022), Indonesia (Karim Citation2018), Japan (Soeya Citation2013) and post-Brexit Britain (Trommer Citation2017).

While a broad discussion of this concept and its limitation is beyond the scope of this paper, I draw on this literature to achieve two objectives. First, the concept of middle powers is useful to think beyond the dichotomies of north versus south (or developed versus developing) which dominate analysis of trade governance. While useful in some areas, such dichotomies provide an over-simplistic view of the international trade regime and the interests and behaviour of different countries in this regime. Second, an important insight that emerges from the middle powers literature is that such powers, considering their limited ability to unilaterally shape global outcomes, show strong support for multilateral organisation (Jordaan Citation2003). In trade governance, studies have highlighted the support and roles some middle powers have played in promoting and shaping the multilateral trade regime and their desire to act as facilitators and bridge-builders in trade regimes (Cooper et al. Citation1993, Trommer Citation2017, Efstathopoulos Citation2018).

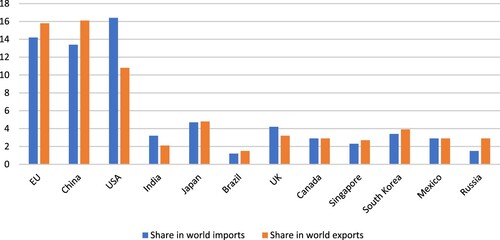

The concept of middle powers can also be useful when analysing regional and bilateral trade agreements. While countries such as Canada and South Korea are usually grouped with the advanced economies in discussions on international trade governance, those countries are significantly smaller and weaker than the large economic powers, as shows.

In recent years, the expansion of bilateral and regional trade agreements was particularly marked between those middle powers and the largest economic powers often with strong power asymmetries between these two groups (Lewis Citation2011, Lee Citation2022). provides a list of the main free trade agreements of the three major economic powers including those with deep provisions.Footnote1We find that a number of middle powers such as Australia, Canada, Singapore, South Korea, Mexico, Japan, as well as countries such as Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, and New Zealand, have signed free trade agreements with at least two of the three powers. A smaller number of them have deep agreements with some of the main powers. These countries are in a particularly strong position in the international trade regime as they have preferential access to some of the largest markets in the world.

Table 1. Main Free trade agreements of the large economic powers.

To conclude, this section has shown how a relatively small number of middle powers are highly integrated into the trade regime of the three main economic powers placing these countries in a highly privileged position in the global trade regime. Analysis of trade and investment diversion will lead us to conclude that those countries might be reluctant to support wider liberalisation in order not to erode this privileged position. I now move to examine the behaviour of those countries in the multilateral trade regime.

Joint statement initiatives at the WTO

Following the failure of the WTO ministerial conference in Buenos Aires in 2017 to make any progress, groups of members began to announce what became known as joint statement initiatives (JSIs). These initiatives are plurilateral negotiations targeting different issues. JSIs are distinct in terms of some being rule-making initiatives while others are, at least for now, broader discussions of a certain issue. Each of these initiatives is led and coordinated by a small number of countries called the co-conveners. lists the main JSIs with the number of participants and the co-conveners.

Table 2. Joint Statement Initiatives in the WTO.Footnote20

The nature of the JSIs has been debated. Some scholars have argued that their aim is to restore the dominance of powerful states in the WTO (Kelsey Citation2022). Other scholars, however, have argued that JSIs offer a path to reinvigorate the multilateral regime by allowing open plurilateral negotiations to be incorporated into the multilateral regime (Hoekman and Sabel Citation2021, Boklan et al. Citation2023). These debates are reflected in discussions between member states. Some countries particularly India and South Africa have been very vocal against the JSIs arguing that these initiatives violate the principles of the WTO.Footnote2 On the other hand, as can be seen above, a relatively large number of countries have joined at least some JSIs. Interviews with officials from those countries reveal that a key objective of participation is ‘keeping the WTO relevant’ in the face of recent economic shifts particularly the growing focus on regional and bilateral agreements. The WTO, many argued, has expanded substantially in recent decades both in terms of number of member states and in terms of the number of issues governed through the organisation. This growing complexity, alongside consensus decision-making, has made it hard to reach any agreements leading many countries to pursue regional and bilateral agreements instead. The JSIs, thus, are seen by many negotiators as a way to improve decision-making in the WTO and restore its centrality in trade governance through a more open approach to negotiations.Footnote3 The roots of the JSIs can be traced to the earlier Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) negotiations. During these negotiations, as a former negotiator involved in the discussion explained in an interview, and while some countries such as the US were open to the idea of negotiating TiSA as a standalone agreement, others insisted that the negotiations should aim to produce an agreement that can be incorporated into the WTO.Footnote4 As one negotiator who was involved in the TiSA negotiations explained:Footnote5

TISA was not in the WTO technically. Materially, it was here in Geneva, it was done at the beginning in the missions of some countries. But towards the end, the meetings were held in the lobby of the WTO. And our objective back then was to create an agreement that was easy dockable into the WTO. So we try to diminish the friction as much as possible. From that time, we were already thinking about the next step for the WTO, the idea of plurilateral agreement with multilateral outcome

Membership in all or most JSIs

To examine membership, I focused on the three initiatives that have moved into rule-making processes (other JSIs remain at a discussion stage and countries can find it harmless to join at this stage). The three rule-making JSIs I examined were: e-commerce, investment facilitation for development, and services domestic regulation. Thirty-six countries have joined all three JSIs. Those countries are Albania, Argentina, Australia, Bahrain, Brazil, Canada, Costa Rica, Chile, Colombia, EU, China, Hong Kong, Uruguay, Georgia, Iceland, Japan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Salvador, Mauritius, Mexico, Nigeria, Montenegro, United Arab Emirates, Moldova, New Zealand, Philippines, Paraguay, Singapore, North Macedonia, United Kingdom, Turkey, Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, Peru, and Norway.

Systemic and proactive support for JSIs

The second criteria was based on the primary reason for joining all or some JSIs. Systemic reasoning includes that membership in JSIs is driven by issues such as the stalemate in the WTO and the need for the multilateral regime to move forward. I contrasted this systemic support with selective support in case of countries that highlight the benefits of a certain JSI as a reason for joining. The United States, for example, is strongly supportive of the e-commerce JSI, due to strong US interests in this sector. Similarly, China is highly supportive of investment facilitation JSI but was initially sceptical of the e-commerce JSI (Gao Citation2020).

Similarly, a proactive reasoning for joining was contrasted with reactive reasoning. A reactive reasoning includes, for example, the pressure to join a JSI because other countries have started the process and there is fear that such discussion will lead to future agreements or the fact that a key trading or strategic partner has joined. In the above list for instance, countries that are EU candidates or seeking EU candidacy such as Albania, Moldova, Georgia, and North Macedonia can be seen as reactive joiners as they align their trade policy with the EU. Similar reactive reasoning was evident in interviews with many developing countries who have joined some JSIs to ‘be in the room’ and limit the negative impact of being left out of future agreements.

Investing resources to move the JSIs forward

Providing resources to the JSIs is particularly important considering that they are effectively organised outside the WTO and that support from the secretariat have been controversial. As such, the JSIs have required substantial resources from members in order to drive the process forward. Initially, some countries embarked on special funding to the WTO with the idea that this funding would be allocated to the JSIs. Critics of JSIs, such as India and South Africa,Footnote6 have, however, questioned this process and demanded successfully that funding that goes into the WTO pool cannot be allocated to specific activities. The smaller role of the WTO secretariat was translated into a larger role of co-conveners relative to normal multilateral processes. In addition to the resources needed to lead the JSIs, some of the co-conveners have allocated additional funding for JSIs. In 2022, for example, the co-conveners of the e-commerce JSI, Australia, Japan, and Singapore in addition to Switzerland, launched the E-Commerce Capacity Building Framework to support the participation of developing and least developing WTO members in the JSI.Footnote7

Based on these three factors, I identify a group of countries that are key systemic drivers of the JSI agenda in the WTO. While the position of China and the US is selectively supportive, and the position of the EU is very supportive (although without playing an official role in the process), the following group of countries are playing a crucial role in driving the JSIs forward: South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica. Those countries have expressed systemic and proactive support for the JSIs, have joined all or most JSIs, and have provided resources to the negotiations (). Two main characteristics of this group can be made. First, it includes a number of middle powers such as Canada, Australia, South Korea, and Japan. Secondly, it includes a high number of insiders to bilateral and regional trade agreements with the key three economic powers, as per , particularly countries who have entered deep agreements with those powers. While some aspects of this position are predictable. For instance, once they have decided to support the JSIs, middle powers have more ability to provide resources than smaller members. The question of why is less clear. What explains this strong support by middle power insiders to the multilateral regime rather than maintaining their privileged bilateral position with the largest powers?

Table 3. Statements of support to the JSI in the WTO General Council.Footnote22

Explaining middle power insiders support for the JSI agenda

Reflecting their support for this agenda, middle power insiders have played an important role in launching and advancing the negotiations within different JSIs. As co-conveners of JSIs, the ambassadors and negotiations of countries such as Singapore, South Korea, Chile, Japan, and Australia, have played an important role in organising and advancing the negotiations. A negotiator who attended the Buenos Aires Ministerial explained the process as followsFootnote8:

The truth is that people had high stakes for the ministerial in Argentina. There was a moment where we were negotiating to actually have an outcome document of that ministerial on some of these JSI issues. The idea was, maybe people don't want to join from the start. But we do need to mature the idea so that when we arrive to the ministerial, if people want to join, they will. I think that that's how it started. In e-commerce, for example, prior to the JSI, the Costa Rican Ambassador started the small group of Friends of e-commerce but then, out of the sudden, everything changed when Australia, Singapore, and Japan said we are going to go beyond just talking about e-commerce and we are going to start an initiative to negotiate rules

I now move to explain this support and role of middle powers in the JSIs.

Support for the multilateral regime

Support for the multilateral regime is a key issue highlighted by officials from middle powers both in interviews and in policy documents.Footnote9 Such support has been explained by multiple factors.

First, officials from middle power insiders have argued that although their countries have bilateral agreements with the largest powers, the existence of the multilateral regime serves as a broader principle of trade governance and as a ‘baseline’ for bilateral relationships with the largest powers.Footnote10 A negotiator for a JSI-supporting country argued thatFootnote11:

We always considered ourselves to be in the middle and we have always supported the multilateral system. If anything happens there, we need to be part of it because we do not want to be squeezed out, and there is a real risk of being left on the outside if we are not inside. We are not the US, we are not the EU, and we are not China, we could be squeezed out

JSIs are a way to in which we can advance and update the rulebook of the WTO by addressing new issues. We have already done a lot of that in our bilateral agreements with the United States, Canada, the European Union, etc. But we are lagging behind in the WTO. For us, the WTO is the basis on which we have our trade policies. It is also the point of departure for negotiating our bilateral agreements. If we start a negotiation with China or the United States, we know that at least we have the WTO that is the base, but we need to update it, because now the base is quite low and the WTO has become outdated

The best outcome for us is within the WTO because we do not have the political or negotiating muscle to move the big members in bilateral negotiations but at the WTO we have the advantage, if we cherry-pick on the sensitivities of the big ones we can get a good outcome

In the case of disputes, the WTO remains our last resort. We may have some schemes in our bilateral agreements but in the end the WTO system is very important and we see it as an equaliser in the sense that we are the same as the others

The multilateral system for a smaller country like us is the assurance of our participation in world trade in the sense that it provides a dispute settlement mechanism that is sound and meaningful and it also puts us in the same level as the others, and help us to have information and get access to all the countries with which we don't have free trade agreements because at the end of the day if you have the resources, maybe if you are the EU, you could have free trade agreements with other 164 or 163 WTO members, but that requires a significant effort and you end up with a very complicated system to administrate all these different agreements.

India always says that investment and services are interests of developed countries and that unless we finish agriculture and non-agricultural market access, we are not interested in going into services. This position, for us, and for others, is a poison candy, because we do not have the market they have, we need to export, and in some of the new areas we have a huge potential but in those areas there is no formal international institution and this is an opportunity for a country like us to have that discussion with other countries and to create rules that can help our exports in those areas. In many of these topics, we have similar policies to those implemented in some of the advanced economies, some countries in the EU for example, so we can work to reach a sensible solution but there are also those in our region who are less advanced than us and need certain benefits and we can help with that. This is a great scenario for us, as we can be bridge-builders between those who are more advanced and those who are less advanced

Non-discrimination in deep integration

As outlined earlier, discrimination between insiders and outsiders has been central to theories on the relationship between regional and bilateral agreements on the one hand and the multilateral regime on the other hand. Such logic, however, is not sufficient to understand deep integration measures that are focused on regulatory harmonisation. Officials from middle power insiders who have signed deep integration agreements with the advanced economies highlighted in interviews how discrimination in those measures is either infeasible or very costly. One official argued thatFootnote17:

Investment facilitation is inherently about regulatory framework. And these regulatory frameworks are implemented on a non-discriminatory basis so we cannot discriminate in these measures and say they apply only to you but not to you. I guess, theoretically, it's possible, but it would be an administrative nightmare.

In services and e-commerce, you are not changing your domestic regime when negotiating these agreements. You are binding it essentially by promising not to do things you already do not do. In e-commerce, for instance, we have made binding commitments not to impose data localisation in our bilateral and regional agreements with the US and others. But, broadly speaking, it is not like we have data localisation requirements for, say India or Argentina. We have the same regime and other countries can benefit from this regime since we are not going to impose data localisation requirements. In this case, your domestic regime is not really changing from one agreement to another, so it makes sense to negotiate them multilaterally as you are giving everybody the same thing anyway and the cost is very low. It is different from traditional trade policy where you are agreeing to mutually reduce barriers and there is as a result horse-trading.

We are looking at it on case-by-case basis. In some areas, such as trade or investment facilitation, you practically cannot discriminate between members and non-members. It is the same for services domestic regulations. But the MSMEs, or e-commerce, that could be a different story and it very much depends on what do they achieve in the JSI. Maybe certain aspects will apply to all, like electronic signature or data localisation, but other aspects, such as zero tariffs on electronic transmissions, can be different. This is something we will have to look at based on the outcome of each JSI

Conclusions

The literature on the political economy of trade agreements leads us to predict that countries who have obtained preferential economic relationships with the largest economic powers would show little enthusiasm for the multilateral regime as they currently enjoy a privileged position that could be eroded by multilateral liberalisation. Countries such as Singapore, South Korea, Australia, Canada, Colombia, and Chile have obtained deeper integration with, to varying degrees, the United States, the European Union, and China can thus be expected to show little enthusiasm for the multilateral regime while countries who have been excluded from such bilateral agreements with the largest powers are expected to show a high level of enthusiasm for this regime in order to limit the damage of bilateral and regional agreements on their economies.

This paper, however, has shown that the opposite has been true in the WTO. It is exactly those insiders to regional and bilateral agreements with leading powers who are the key supporters of advancing the multilateral regime with some of them, particularly middle powers, going further to provide the resources to disrupt the gridlock at the WTO through the JSI agenda. I offered two explanations for this position. First, I highlighted how middle powers maintain strong systemic support for the multilateral regime as they see it as a guarantor of their bilateral relationships with the leading powers and a fall-back option that reduce power asymmetry in those relationships. Further, I argued that middle powers see the multilateral regime as the forum through which they can play the role of ‘bridge-builders’ between the largest economic powers and more developing economies and to expand their economic opportunities considering the challenge of negotiating trade agreements with a large number of partners. Secondly, I argued that the deepening of trade agreements is altering the logic of insiders and outsiders in bilateral and regional agreements due to the infeasibility or high cost of discrimination in many of these regulatory areas. In such contexts, once insiders enter deep integration agreements with leading powers, they largely offer these benefits on non-discriminatory basis to all countries which reduces the bargaining value of these issues in any future trade negotiations with third countries. In this context, middle power insiders focus on the opportunities of expanding those rules to a wider set of countries through the multilateral regime rather than on the limited bargaining value they can obtain by trying to withhold those benefits from third countries for future trade negotiations. These two factors are intertwined. The relatively smaller size of middle powers and their lack of the resources and leverage needed to exploit the opportunities created by the new rules bilaterally or regionally with the rest of the world make the multilateral framework an attractive arena for them to disseminate these rules globally particularly through working together to advance their agenda in the WTO and to compensate for the declining interest of some of the major powers in the WTO.

Through these two findings, this paper has contributed to the literature on trade regimes and to the literature on middle powers. With regards to trade regimes, my findings support the argument by scholars such as Richard Baldwin (Baldwin Citation2011) that traditional thinking of regionalism through the lenses of trade diversion and creation is not adequate to analyse twenty-first-century regionalism and its relationship with the multilateral regime. By examining the way insiders to bilateral and regional agreements with the large economic powers seek to disseminate these rules multilaterally, this paper has examined specific channels through which this new type of integration drive new incentives that cannot be explained by previous frameworks of analysis. In addition, this paper has provided one of the first attempts to examine empirically, based on extensive research with WTO negotiators, the processes and incentives behind the emergence of the JSIs and the debates surrounding their expansion in the trade arena. With regards to middle powers, while recent studies have discussed the role of middle powers in attempting to fill the growing vacuum in global leadership and to pursue multilateral initiatives (Brattberg Citation2021), this paper has illustrated the proactive role of middle powers in launching, leading, and investing resources into specific initiatives that partially aimed at maintaining the relevance of the WTO in the context of growing US hostility to the organisation. This entrepreneurial leadership role of middle powers is not only driven by their direct economic interests but also by their attempts to position themselves as champions of the multilateral trade regime in an era of fragmentation and as bridge-builders in this regime (Efstathopoulos Citation2018). The challenges surrounding the JSIs, however, raise the question of the ability of middle powers in playing such a role without strong support from powerful actors with more material capabilities, namely the United States, China, and the EU. As the JSIs move forward and debates around incorporating them into the WTO architecture intensify, the power of middle powers to deliver will be tested.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shamel Azmeh

Shamel Azmeh is a lecturer at the Global Development Institute (GDI) at the University of Manchester. His work focuses on global production and trade, global value chains, and trade governance.

Notes

1 For the purpose of this classification, I have defined deep agreements as those that include measures on investments liberalization, domestic regulation, government procurement, intellectual property rights, and competition.

2 See submission WT/GC/W/819 (date 19/2/2021) by India and South Africa to the WTO General Council.

3 See the joint Communiqué by Ottawa Group (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, the European Union, Japan, Kenya, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore and Switzerland) on WTO reform (October 25, 2018).

4 Interview#74, February 2023.

5 Interview#30, May 2022.

6 See submission WT/GC/W/819 (date 19/2/2021) by India and South Africa on the legal status of the JSIs.

7 'E-Commerce JSI co-convenors announce capacity building support', World Trade Organisation, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/ecom_e/jiecomcapbuild_e.htm.

8 Interview#33, May 2023.

9 See for example the Australian government impact analysis of the service domestic regulation JSI (available at: https://oia.pmc.gov.au/published-impact-analyses-and-reports/wto-services-domestic-regulation-joint-statement-initiative). See also the WTO Trade Policy Reviews for Colombia (WT/TPR/G/372).

10 See for example the WTO Trade Policy Review for Costa Rica (WT/TPR/G/392).

11 Interview#73, January 2023.

12 Interview#57, August 2022.

13 Interview#30, May 2022.

14 Interview#35, May 2022.

15 Interview#40, June 2022.

16 Interview#30, May 2022.

17 Interview#25, April 2022.

18 Interview#73, January 2023.

19 Interview#32, May 2022.

20 These numbers are as of April 2023.

21 EU members are counted individually (27).

22 See WTO General Council minutes of meetings for the following dates: 23–24 February 2022 (WT/GC/M/196), 1–2 and 4 march 2021 (WT/GC/M/190), 7–8 October 2021 (WT/GC/M/193), 27–28 July 2021 (WT/GC/M/192), 5–6 May 2021 (WT/GC/M/191).

References

- Anderson, J.E., and Yotov, Y.V., 2016. Terms of trade and global efficiency effects of free trade agreements, 1990–2002. Journal of international economics, 99, 279–298.

- Azmeh, S., Foster, C., and Echavarri, J., 2020. The international trade regime and the quest for free digital trade. International studies review, 22 (3), 671–692.

- Baccini, L., Pinto, P.M., and Weymouth, S., 2017. The distributional consequences of preferential trade liberalization: firm-level evidence. International organization, 71 (2), 373–395.

- Baccini, L., and Dür, A., 2015. Investment discrimination and the proliferation of preferential trade agreements. Journal of conflict resolution, 59 (4), 617–644.

- Baldwin, R.E., 2006. Multilateralising regionalism: spaghetti bowls as building blocs on the path to global free trade. World economy, 29 (11), 1451–1518.

- Baldwin, R., and Jaimovich, D., 2012. Are free trade agreements contagious? Journal of international economics, 88 (1), 1–16.

- Baldwin, R., 1993. A domino theory of regionalism. In: R. Baldwin, P. Haarparanta, and J. Kianden, eds. Expanding membership of the European Union. Cambridge University Press, 25–45.

- Baldwin, R.E., 2011. 21st Century Regionalism: filling the gap between 21st century trade and 20th century trade rules. Available from: SSRN 1869845.

- Baharumshah, A.Z., Onwuka, K.O., and Habibullah, M.S., 2007. Is a regional trade bloc a prelude to multilateral trade liberalization? Empirical evidence from the ASEAN-5 economies. Journal of Asian economics, 18 (2), 384–402.

- Beeson, M., and Higgott, R., 2014. The changing architecture of politics in the Asia-pacific: Australia's middle power moment? International relations of the Asia-Pacific, 14 (2), 215–237.

- Bhagwati, J., 2008. Termites in the trading system: How preferential agreements undermine free trade. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bohara, A.K., Gawande, K., and Sanguinetti, P., 2004. Trade diversion and declining tariffs: evidence from mercosur. Journal of international economics, 64 (1), 65–88.

- Boklan, D., Starshinova, O., and Bahri, A., 2023. Joint statement initiatives: A legitimate end to ‘until everything is agreed’? Journal of world trade, 57 (2), 339–360.

- Brattberg, E., 2021. Middle power diplomacy in an Age of US-China tensions. The Washington quarterly, 44 (1), 219–238.

- Cardamone, P., and Scoppola, M., 2012. The impact of EU preferential trade agreements on foreign direct investment. The world economy, 35 (11), 1473–1501.

- Chang, W., and Winters, L.A., 2002. How regional blocs affect excluded countries: The price effects of MERCOSUR. American economic review, 92 (4), 889–904.

- Cooper, A.F., Higgott, R.A., and Nossal, K.R., 1993. Relocating middle powers: Australia and Canada in a changing world order (Vol. 6). Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Eagleton-Pierce, M.D., 2012. The competing kings of cotton:(Re) framing the WTO African cotton initiative. New political economy, 17 (3), 313–337.

- Efstathopoulos, C., 2018. Middle powers and the behavioural model. Global society, 32 (1), 47–69.

- Estevadeordal, A., Freund, C., and Ornelas, E., 2008. Does regionalism affect trade liberalization toward nonmembers? The quarterly journal of economics, 123 (4), 1531–1575.

- Faude, B., 2020. Breaking gridlock: How path dependent layering enhances resilience in global trade governance. Global policy, 11 (4), 448–457.

- Freedman, A., 2022. Thailand as an awkward middle power. In: G. Abbondanza, and T.S Wilkins, eds. Awkward powers: escaping traditional great and middle power theory. Global political transitions. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 131–149.

- Freund, C., and Ornelas, E., 2010. Regional trade agreements. Annual review of economics, 2 (1), 139–166.

- Fugazza, M., and Nicita, A., 2013. The direct and relative effects of preferential market access. Journal of international economics, 89 (2), 357–368.

- Gao, H.S., 2020. Across the Great Wall: E-commerce Joint Statement Initiative Negotiation and China. Available from: SSRN 3695382.

- Gecelovsky, P., 2009. Constructing a middle power: ideas and Canadian foreign policy. Canadian foreign Policy journal, 15 (1), 77–93.

- Hale, T., Held, D., and Young, K., 2013. Gridlock: from self-reinforcing interdependence to second-order cooperation problems. Global policy, 4 (3), 223–235.

- Hoekman, B., and Sabel, C., 2019. Open plurilateral agreements, international regulatory cooperation and the WTO. Global policy, 10 (3), 297–312.

- Hoekman, B., and Sabel, C., 2021. Plurilateral cooperation as an alternative to trade agreements: innovating one domain at a time. Global policy, 12, 49–60.

- Hopewell, K., 2016. Breaking the WTO: How emerging powers disrupted the neoliberal project. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Hofmann, C., Osnago, A., and Ruta, M., 2017. Horizontal depth: a new database on the content of preferential trade agreements. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7981, the World Bank.

- Jordaan, E., 2003. The concept of a middle power in international relations: distinguishing between emerging and traditional middle powers. Politikon, 30 (1), 165–181.

- Karim, M.F., 2018. Middle power, status-seeking and role conceptions: the cases of Indonesia and South Korea. Australian journal of international affairs, 72 (4), 343–363.

- Kelsey, J., 2022. The illegitimacy of joint statement initiatives and their systemic implications for the WTO. Journal of international economic law, 25 (1), 2–24.

- Krishna, P., 1998. Regionalism and multilateralism: A political economy approach. The quarterly Journal of Economics, 113 (1), 227–251.

- Krishna, P., 2013. Preferential trade agreements and the world trade system: a multilateralist view. In: Robert C. Feenstra, and Alan M. Taylor, eds. Globalization in an age of crisis: multilateral economic cooperation in the twenty-first century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 131–160.

- Lake, J., and Krishna, P., 2019. Preferential trade agreements: recent theoretical and empirical developments. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance.

- Lam, P.E., 2022. Singapore as an awkward “little Red Dot”: between the small and middle power status. In: G. Abbondanza, and T.S Wilkins, eds. Awkward powers: escaping traditional great and middle power theory. Global political transitions. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 329–348.

- Lee, S.Z., 2022. Middle power and power asymmetry: how South Korea’s free trade agreement strategy with ASEAN changed under the New southern policy. Contemporary politics, 29 (3), 318–338.

- Lee, D., and Smith, N.J., 2008. The political economy of small African states in the WTO. The round table, 97 (395), 259–271.

- Lewis, M.K., 2011. The politics and indirect effects of asymmetrical bargaining power in free trade agreements. In: T. Broude, M. Busch, and A. Porges, eds. The politics of international economic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 19–39.

- Libman, A., 2021. Eurasian regionalism and the WTO: a building block or a stumbling stone? Post-communist economies, 33 (2–3), 246–264.

- Limao, N., 2006. Preferential trade agreements as stumbling blocks for multilateral trade liberalisation: Evidence for the United States, American economic review, 96 (3), 896–914.

- Limão, N., 2007. Are preferential trade agreements with non-trade objectives a stumbling block for multilateral liberalization? The review of economic studies, 74 (3), 821–855.

- Levy, P.I., 1994. Political economy and free trade agreements. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Mattoo, A., Mulabdic, A., and Ruta, M., 2022. Trade creation and trade diversion in deep agreements. Canadian journal of economics, 55 (3), 1598–1637.

- Morse, J.C., and Keohane, R.O., 2014. Contested multilateralism. The review of international organizations, 9 (4), 385–412.

- Narlikar, A., 2010. New powers in the club: the challenges of global trade governance. International affairs, 86 (3), 717–728.

- Nelson, D.R., 2019. Facing up to Trump administration mercantilism: The 2018 WTO trade policy review of the United States. The world economy, 42 (12), 3430–3437.

- Ornelas, E., 2005a. Rent destruction and the political viability of free trade agreements. The quarterly journal of economics, 120 (4), 1475–1506.

- Ornelas, E., 2005b. Trade creating free trade areas and the undermining of multilateralism. European economic review, 49 (7), 1717–1735.

- Romalis, J., 2007. NAFTA's and CUSFTA's impact on international trade. The review of economics and statistics, 89 (3), 416–435.

- Schoeman, M., 2015. South Africa as an emerging power: from label to ‘status consistency’? South African journal of international affairs, 22 (4), 429–445.

- Selcher, W.A., 2019. Brazil in the international system: the rise of a middle power. New York: Routledge.

- Stephen, M.D., 2017. Emerging powers and emerging trends in global governance. Global governance, 23 (3), 483–502.

- Soeya, Y., 2013. Prospects for Japan as a middle power. East Asia forum quarterly, 5 (2), 36–37.

- Takamiya, K., 2019. Recently acceded members of the world trade organization: membership, the Doha development agenda, and dispute settlement. Singapore: Springer.

- Trommer, S., 2017. Post-Brexit trade policy autonomy as pyrrhic victory: being a middle power in a contested trade regime. Globalizations, 14 (6), 810–819.

- Urpelainen, J., and Van de Graaf, T., 2015. Your place or mine? institutional capture and the creation of overlapping international institutions. British journal of political science, 45 (4), 799–827.

- Wang, Q., 2020. FTA: a stumbling bloc towards global free trade. International journal of economics and finance, 12 (1), 1–22.

- Wilkinson, R., and Scott, J., 2008. Developing country participation in the GATT: a reassessment. World trade review, 7 (3), 473–510.

- Wei, S.J., and Frankel, J.A., 1996. Can regional blocs be a stepping stone to global free trade? a political economy analysis. International review of economics & finance, 5 (4), 339–347.

- Zahid, H., Bashir, M.F., and Tahir, M., 2021. Relationship between preferential trade agreements and foreign direct investment: evidence from a panel of 147 countries. The international trade journal, 35 (6), 523–539.