ABSTRACT

It has been argued that party membership has declined in most liberal democracies over the past several decades, and the remaining party members are even more committed to party goals and policies. If partisanship becomes more of an elite phenomenon, it might also become a very effective tool to exert political influence. We use Comparative Study of Electoral Systems data (1996–2016) to investigate the magnitude of the association over time between party identification and political efficacy. The results support our main hypotheses that party identification remains strongly associated with political efficacy throughout the observation period, and that the magnitude of this association has increased in recent years. Thus, despite attention in the literature to stagnating or declining party identification, we provide new evidence that supports expectations in the literature of continued and even increased importance of the relationship between party identification and political efficacy.

Traditionally, it is assumed that citizens exert political influence by supporting the political party that best reflects their own political preferences. Being close to a political party therefore seems to be the most straightforward manner to gain political efficacy: if that party does well in elections and can implement its programme, citizen actually do have an influence on political decision making. Yet, research indicates that the key institution of political parties has become weaker in recent decades. Membership figures have declined systematically over several decades, and feelings of partisanship have also eroded (Huddy et al., Citation2015; Scarrow, Citation2015). While the erosion of traditional, institutionalised partisanship has been investigated extensively, there is far less knowledge about what this trend implies for the way citizens relate to the political system (Mair, Citation2014). If political parties really are the most crucial linkage mechanism between citizens and the political system, they should be a key source for the feeling of political efficacy, while their gradual demise should have a detrimental effect on that feeling of efficacy.

Trends with regard to the connection between party identification and political efficacy, therefore, are highly relevant for the broader question about the popular disenchantment among the public with liberal democracy. First of all, it is important to get the trends right. While there is a wide array of studies showing a structural decline in partisanship (Dalton, Citation2002; Katz et al., Citation1992; Mair & van Biezen, Citation2001; Scarrow, Citation2000; Scarrow et al., Citation2017; van Biezen et al., Citation2012; van Biezen & Poguntke, Citation2014; van Haute & Gauja, Citation2015; Webb et al., Citation2002; Whiteley, Citation2011), other authors tend to portray more stability in these figures, particularly in recent decades (e.g. Dalton, Citation2016; Dalton et al., Citation2011; Lupu, Citation2015). It has also been claimed that changes in partisanship are not just quantitative, but also qualitative: citizens have developed new means to connect to political parties, and this more recent participation pattern might be associated with more political power (Scarrow, Citation2015, Citation2019; Scarrow & Gezgor, Citation2010). If that is the case, the effect of partisanship on political efficacy should become stronger over time. It is important to ascertain the precise relation between partisanship and political efficacy, because efficacy is a key requirement for democratic legitimacy.

High levels of political efficacy have been assessed as central to the health of democratic systems (Craig et al., Citation1990; Oser, Citation2023). If citizens do not have the feeling that their vote makes a difference, and can have an impact on the way their societies are being governed, they have far less reason to consider their political system as fair and legitimate (Campbell et al., Citation1954; Oser et al., Citation2023). Political efficacy is strongly related to political participation, not only because feeling efficacious encourages participation, but also because participation can boost feelings of efficacy, thus increasing the likelihood that participators will continue to participate in the future (Finkel, Citation1985; Pollock, Citation1983). As such, political efficacy is a crucial resource to ensure both the functioning and the legitimacy of democratic political systems (Iyengar, Citation1980) and to enable a chain of responsiveness between citizens and their elected leaders (Powell, Citation2004, Citation2014). It has been well-established in the literature that citizens who feel they can influence government outcomes are more likely to support the democratic system as a whole (Easton, Citation1965). While some studies have shown a positive relation between partisanship and political trust (Hooghe & Oser, Citation2017; Whiteley & Kölln, Citation2019), we do not know all that much about (trends in) the relation between partisanship and political efficacy (Mair, Citation2014; Muirhead, Citation2006, Citation2014; Muirhead & Rosenblum, Citation2020).

The goal of the current study is to investigate this relation in a comparative manner, over a two decade period. To do so, we analyse all available data on this topic from the Comparative Studies of Electoral Systems (CSES) survey between 1996 and 2016, focusing on the subset of countries that are included in all four observation periods, in order to make a valid over time comparison. The findings show that during this time period, party identification is indeed positively associated with political efficacy, and the strength of this association increases significantly over time. Feeling very close to a political party has an even stronger effect on political efficacy. We close with some observations on what these results imply for the future democratic role of political parties.

Party identification and political efficacy

Party identification is traditionally regarded as an important component in the linkage between citizens and the political system (Miller et al., Citation1999). Therefore it is assumed that those who feel close to a political party will have higher levels of political efficacy, as those who do not have a preferred party, indeed have fewer means available to make sure their opinion prevails in political decision making (e.g. Almond & Verba, Citation1963; Banducci & Karp, Citation2009; Karp & Banducci, Citation2008). Research shows that this effect is very strong, for those who are involved in the party organisation as such (Bentancur et al., Citation2019). However, the traditional notion of ‘partisanship’ does not require any formal connection with, or activity in a political party: the mere fact that one feels close to a political party, and even identifies as being close to that party, is sufficient to be considered a partisan. The question we want to investigate is whether this broader, attitudinal measurement of partisanship also has effect on political efficacy, even in the absence of any formal engagement within political parties.

Political efficacy is a highly important attitudinal measure as it connects individuals with the functioning of the state, and is indicative of the health of the democratic systems (Oser, Citation2023). Research shows a positive association between political efficacy and political participation, such as election turnout (Abramson & Aldrich, Citation1982), civic participation and volunteerism (Verba et al., Citation1995), including online political participation (Oser et al., Citation2022); all contributing to the legitimacy of democratic systems.

The concept of political efficacy is traditionally defined as: ‘the feeling that individual political action does have, or can have, an impact upon the political process’ (Campbell et al., Citation1954, p. 187). Subsequent studies have shown that political efficacy is conducive to democratic government, and provides diffuse support for system stability (Almond & Verba, Citation1963; Easton, Citation1965; Easton & Dennis, Citation1967; Finifter, Citation1970; Pateman, Citation1970; Thompson, Citation1970).

The crucial distinction between internal and external measures of political efficacy was introduced early in the literature by Lane (Citation1959) to distinguish between individuals’ feelings about their own capacity to participate in the democratic process, versus their assessments of external system responsiveness. In the former case, a lack of efficacy is attributed to the individual (e.g. ‘not knowledgeable enough’), while in the latter case, the political system is to blame for its unwillingness to be responsive to public opinion. Both concepts are therefore measured in a different manner. Niemi et al.’s (Citation1991, pp. 84–85) definition of the two key dimensions of political efficacy can still be regarded as seminal: internal efficacy, defined as ‘beliefs about one’s own competence to understand, and to participate effectively in, politics’, and external efficacy, defined as ‘beliefs about the responsiveness of governmental authorities and institutions to citizen demand’. External efficacy therefore relates to citizens’ beliefs about the consequences of people’s involvement in politics (Esaiasson et al., Citation2015). While both of these dimensions of political efficacy may have a relation to party identification, the most relevant dimension for this topic is external efficacy since party identity should provide citizens with more and more effective access opportunities to the political system (Jacobs et al., Citation2022; Wolak, Citation2018).

Taken together, this literature supports the expectation that people who feel close to a political party are more likely to have higher levels of political efficacy in general, and external efficacy in particular. However, we note that this relation between party identification and political efficacy might be endogenous, as it could be that political efficacy predicts party identification, rather than the other way around. Nevertheless, we believe that party identification is the explanatory factor, rather than the outcome. First, the literature on economic voting recognises that individual perceptions might be affected by partisan identity (Bartels, Citation2002).Footnote1 In this line of research, partisanship defines attitudes about the overall government performance and with that about overall government responsiveness. Second, party identifiers are more likely to be involved in political parties (thorough party membership or participation in meetings) and with that have more channels to affect the political system and the general responsiveness of the system, affecting their attitudes about external political efficacy. These additional channels are the link we believe that makes party identification an explanatory factor of external political efficacy.

External efficacy has been the focus of concerns due to documented trends of decline in U.S. data (Chamberlain, Citation2012), and also due to the relevance of this attitude for connecting individuals with democratic processes (Henderson & Han, Citation2021). A potential explanation for the expected positive association between party identification and external political efficacy is that individuals who are close to a political party have invested time and effort to gather knowledge about the political party they support. This investment could be driven by expected benefit, as those who are close to a political party may have more incentives to believe that the act of voting has beneficial political consequences. In line with previous research, we first expect a positive relation between partisanship and political efficacy, as our baseline hypothesis. Despite the fact that in numerous countries there are indications about a decline of levels of partisanship, as a baseline hypothesis we have no reason to assume that this positive association would have disappeared in the more recent period. Thus, we first expect that

Baseline hypothesis: party identification will be positively associated with political efficacy in general.Footnote2

While this baseline hypothesis draws on established expectations in classic social science literature, we are unaware of any empirical study that has rigorously tested whether these expectations are supported by an analysis of recent, high-quality cross-national data.

Our further theoretical expectations build on the concept developed by Whiteley and Kölln’s (Citation2019) about changing forms of partisanship, where party identifiers are divided into two types. Type-I partisanship is stable in nature, where party identifiers always vote for the same party. Type-II partisanship is performance based and party identifiers calculate the perceived effectiveness of policy output, i.e. the running tally model (Fiorina, Citation1981). A large body of literature suggests that the electorate is a mixture of the two types, and depending on the time-period the pool of partisans might shift in dominance, thus affecting accountability function (Whiteley & Kölln, Citation2019). We aim to study this time shifting trend, as the type of party identifiers in our sample might also influence the level of external political efficacy. For example, if party identifiers are generally more satisfied with the overall party performance, this might produce an increased level of political efficacy (that who is in power can make a difference, and whom people vote for makes a difference), although the overall level of partisanship remains stable. However, if this satisfaction with the general policy output of the party they support is declining, this could lead to a decline in external political efficacy as well. Unfortunately, we can only partially test this mechanism, as the CSES data use questions regarding the evaluation of government performance only in half of our sample (i.e. in Modules 2 and 3 only). Yet, the results suggest that indeed a positive evaluation of government performance is positively associated with both measures of external political efficacy (see Appendix A3.7), suggesting that this mechanism about the source of partisanship might be present here as well.

This connects to an important line of literature stating that while partisanship might have declined in a quantitative manner, qualitative changes imply that those who remain partisan will become more highly motivated, and are more likely to make a strong, reasoned choice for being close to a political party (Scarrow, Citation2015, Citation2019; Scarrow & Gezgor, Citation2010). This line of reasoning leads to the expectation that the relationship between party identification and political efficacy should have strengthened in recent years. In contrast to our baseline hypothesis, this is not a widespread expectation in the literature, as it focuses attention on the attitudinal connection of those citizens who maintain identification with parties, despite negative trends with regard to the occurrence of partisanship. While the theoretical reasoning of this expectation is appealing, we are unaware of any empirical tests of this hypothesis:

H1: The association between party identification and political efficacy strengthens over the 1996–2016 observation period.

To the extent that partisanship becomes more a scarce phenomenon across democratic societies, one can expect that the remaining partisans indeed feel very close to a political party. A standard assumption in organisational research is that those who feel only lukewarm towards the organisation, will be first to jump ship, thus leaving a smaller group of highly motivated hardcore supporters within the organisation. To the extent that there are fewer ‘leaning’ or ‘moderate’ partisans, and therefore the proportion of ‘strong’ partisans is increased, this gradation, too, should become more important in the recent period:

H2: The association between the level of party identification and political efficacy strengthens over the 1996–2016 observation period.

Data and methods

We analyse data from the Comparative Studies of Electoral Systems Integrated Module Dataset (CSES).Footnote3 The CSES surveys are conducted after general elections, and cover a period of 20 years, from the CSES Module 1 in 1996 to Module 4 in 2016. The CSES data structure is a repeated cross-section, and therefore cannot shed light on causal relations over time. However, CSES provides high-quality cross-national data for the theoretical focus of our study. The Appendix includes additional information about the data and methods described in this section, including variable descriptions (Appendix Section A1), descriptive statistics (Section A2), and supplementary analyses (Section A3). The analyses were conducted in R 4.0.4, and data, code, and replication files are available from the authors.

The full CSES dataset for Modules 1 (1996) through 4 (2016) includes data on 53 countries and 276,968 individuals.Footnote4 The dataset includes cross-national data from a 20-year observation period that can contribute to making valid inferences regarding over-time changes in the relation between the key concepts of party identification and political efficacy. Since we are interested in over-time trends, our analyses focus on only those countries that participated in all four CSES modules, i.e. a sample of 20 countries and most of them can be regarded as stable democracies.Footnote5 The CSES survey includes two questions on political efficacy that are included with similar question wording in all modules: (a) respondents’ perception of whether who is in power makes a difference, which we will refer to as ‘efficacy power’; and (b) respondents’ perceptions of whether who people vote for can make a difference, which we refer to as ‘efficacy vote’. Taken together, these two indicators measure citizens’ perceptions of whether elections have consequences. Both measures are important indicators of external efficacy, and unfortunately the CSES cumulative file does not include measures of internal efficacy. However, for the purpose of testing our hypotheses regarding the relationship between party identification and political efficacy, external efficacy is the more theoretically relevant of the two measures.

The CSES includes two main levels of data, with respondents (micro-level observations) nested in countries (macro-level observations). The clustered structure of the data violates the assumption of independence of observations, and failure to account for this data structure could lead to incorrect estimations of standard errors (Gelman & Hill, Citation2006). As the CSES surveys are conducted in each country in coordination with the timing of national elections, another relevant level for research that focuses on over-time change is the time period of survey implementation in each country. We therefore estimate a three-level model with individuals (level 1) nested in survey module country-years (level 2) in a given country (level 3). We estimate OLS models with year and country dummies to account for this nested structure. As robustness tests, we also employ multilevel models with random intercepts by year and by country. Further, we analyse the full sample of 53 countries, and these findings do not deviate from those reported in the manuscript (see Appendix).

Independent variables

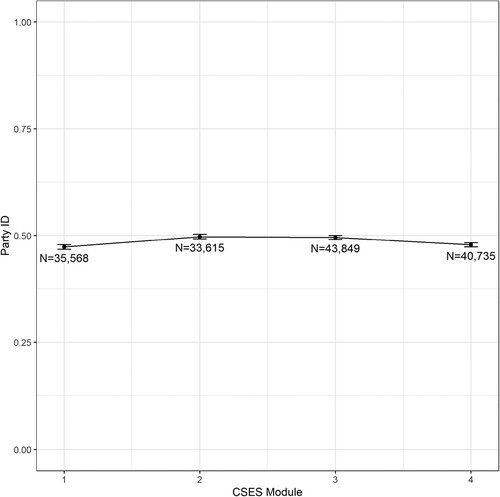

The key independent variables in the analysis are identification with a political party (PID), and the closeness of this identification (PID level). Party identification is a binary measure of whether respondents considered themselves as close to any political party (0 = no; 1 = yes). For all 20 countries in the dataset, 47% of all respondents reports being close to at least one political party, and the results in indicate that this proportion remained relatively stable across all four survey modules. However, variations across countries clearly exist, with the largest percentage of reported partisans in Australia (85.4%) and U.S.A. (60.0%) across the CSES modules, while Peru and Slovenia report the lowest percent of respondents identifying as close to a political party, with 36.0% and 20.1% respectively.Footnote6

Figure 1. Proportion respondents with party identity for 20 countries, 1996–2016.

Notes: Entries are the proportion of respondents (ranging from 0 to 1) that is close to a political party. Times spans are as follows: Module 1 (1996–2001), Module 2 (2001–2006), Module 3 (2006–2011), and Module 4 (2011–2016). Standard deviation for party identity = 0.50.

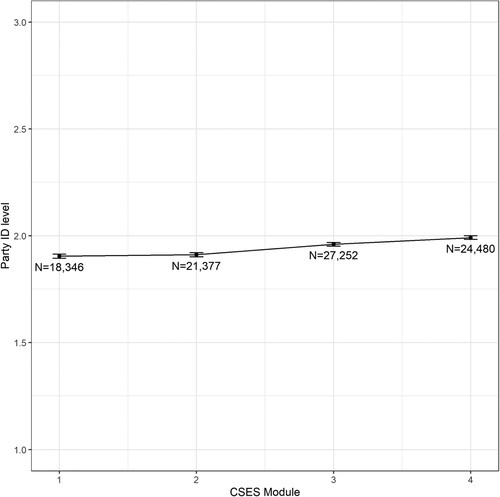

Respondents who reported being close to a political party received a follow-up question that asks how close respondents felt to this party, ranging from 1 = not very close; 2 = somewhat close; to 3 = very close. shows that the mean point estimate increased in each observation period,Footnote7 with significant but modest increases in the two most recent modules. So while the total proportion of partisans is rather stable, within this group there seems to be a trend to report being closer to the preferred party over time.

Figure 2. Party identification level for 20 countries, 1996–2016.

Notes: Entries are ‘degree of closeness to a political party’, for partisans only, ranging from 1 (not very close) to 3 (very close). Times spans are as follows: Module 1 (1996–2001), Module 2 (2001–2006), Module 3 (2006–2011), and Module 4 (2011–2016). Standard deviation for level of party identification = 0.69.

Taken together, the trends for both the PID and PID level measures are consistent with findings in the literature that show stability in PID in the most recent decades: the CSES data show that the proportion of respondents that identified with at least one party (response options: 0 = no; 1 = yes) remained fairly stable, with almost half (0.47) of the population reporting closeness to any political party. The level of reported closeness among those with a party identification (response options: 1 = not very close; 2 = somewhat close; 3 = very close) increased modestly, supporting the observation in the literature that those who report a partisan identity have increased their commitment to that party.

Outcome measures

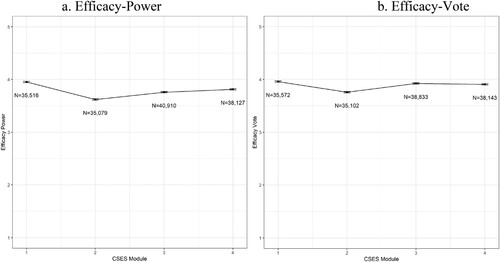

As noted, we analyse two measures of external political efficacy in the CSES data, based on the items: (a) who is in power can make a difference, and (b) whom people vote for makes a difference. This in particular measures respondents’ attitudes towards the external political system, not their own belief of individually being capable to influence the system. Response categories are measured on a 5-point scale where 1 refers to ‘it does not make any difference’ and 5 refers to ‘it makes a big difference’. Higher scores thus imply a higher level of external political efficacy. displays the mean efficacy scores for respondents in the 20 countries that participated in all four CSES modules (see Appendix for means by country). The figure shows that throughout the observation period, average efficacy levels are relatively stable and high: efficacy-power ranged from 3.62 to 3.96, and efficacy-vote ranged from 3.76 to 3.96.

Figure 3. Political efficacy means for 20 countries, 1996–2016.

Notes: Entries are mean scores on two items on external political efficacy, ranging from 1 (low efficacy) to 5 (high efficacy). Time spans are as follows: Module 1 (1996–2001), Module 2 (2001–2006), Module 3 (2006–2011), and Module 4 (2011–2016). Standard deviation for efficacy-power = 1.29; Standard deviation for efficacy-vote = 1.24.

Control variables

We control for variables that are expected to affect the relationship between partisanship and efficacy (Hayes & Bean, Citation1993; Wolak, Citation2018). Therefore, we include controls for age (measured in continuous years); gender (0 = male; 1 = female); and socio-economic status, measured by level of education (1 = none; 5 = university) and income (1 = lowest quintile; 5 = highest quintile). The literature reports mixed findings regarding the association of political efficacy with gender and age, while the association with socio-economic status has generally been found to be positive. Following concerns that missing data on the income variable may not be missing at random, we include income in the model as a supplementary analysis reported in full in the Appendix.

We also control for respondents’ political ideology to account for whether political efficacy is more closely related to one end of the political spectrum than the other (left or right). This variable is based on a standard ideology survey question, in which respondents were asked to place themselves on an 11-point scale with 0 indicating left and 10 indicating right. As recent research has identified a right-wing bias in government positions (Blais et al., Citation2022; Dassonneville et al., Citation2021), it is plausible that those on the right may have higher efficacy levels than those on the left.

As a robustness test, we also control for electoral participation, measured as self-reported voter turnout. The analyses include a binary measure based on respondents’ report of whether they voted in the last election (0 = no; 1 = yes). We expect that those who participate in elections will have higher levels of political efficacy, but self-evidently we do not wish to make any claim about the causal relation involved (Abramson & Aldrich, Citation1982; Banducci & Karp, Citation2009; Karp & Banducci, Citation2008; Shaffer, Citation1981). Similar to the reasoning underlying the expected relation with party identification, we expect that individual decisions to invest time and effort to vote are driven by the expected political benefit, i.e. incentives based on the belief that the act of voting or those who are in power can make a political difference. However, research has also shown evidence that political efficacy can come first in the equation, meaning that political efficacy can have a causal influence on voter turnout (Finkel, Citation1985; Quintelier & van Deth, Citation2014). We therefore conduct supplementary analyses that include electoral participation (see Appendix), and the findings are consistent with those presented in the results section.

Finally, we include a supplementary analysis that controls for respondents’ assessment of government performance, which asks respondents to assess how good or bad a job the current government has done (1 = very bad job; 4 = very good job). Based on recent research on the relationship between policy processes and political efficacy (Wolak, Citation2018), we expect that citizens’ positive assessment of their governments’ performance will also be positively associated with their sense of political efficacy. As the government performance question was not asked in CSES Modules 2 and 3, and therefore has a large number of missing observations (n for missing observations = 94,944), we briefly summarise the findings from these models to inform future research, and report on the findings in more detail in the Appendix.

Results

As noted, our empirical approach separately investigates the two dependent variables measuring political efficacy, namely, efficacy-power and efficacy-vote. As we only have two items to measure the concept, we cannot meaningfully conduct any factor analysis on these items. This section documents the coefficient plots of the key variables from the multilevel regression models, and the fully specified regression tables are documented in the Appendix.

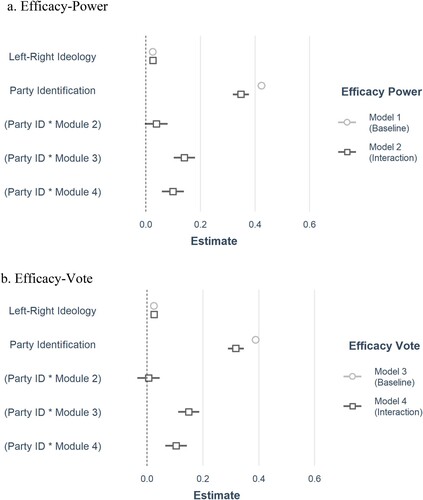

In , the baseline models present the results in relation to our baseline hypothesis that party identification is positively associated with efficacy. As expected, the findings support this hypothesis as party identification is strongly associated with both survey items for political efficacy ((a) Model 1 for efficacy-power, and (b) Model 3 for efficacy-vote). These results affirm established findings in prior research by showing that party identification is still closely linked with efficacy in the 1996–2016 observation period of the current study, as those who reported being close to at least one political party reported higher levels of political efficacy than those who lacked a connection to any party. also plots the coefficient for left-right ideology, which aligns with our expectations of a positive coefficient informed by scholarship showing that those on the right may have higher efficacy levels than those on the left due to right-wing bias in government positions. The findings for all additional control variables are consistent with expectations in the literature (see Appendix).

To test our expectation that party identification has become more strongly associated with political efficacy in recent years (H1), we test for an interaction effect between party identification and CSES module. In , the coefficient plots for the interaction effects support this expectation ((a) Model 2 for efficacy power, and (b) Model 4 for efficacy vote). The findings show that the magnitude of the association of party identification with efficacy in Module 2 is not significantly different from that in Module 1, but that the interaction term has significantly increased in Modules 3 and 4, compared to Module 1. Taken together, these findings confirm that party identification has become more strongly associated with political efficacy in recent years.

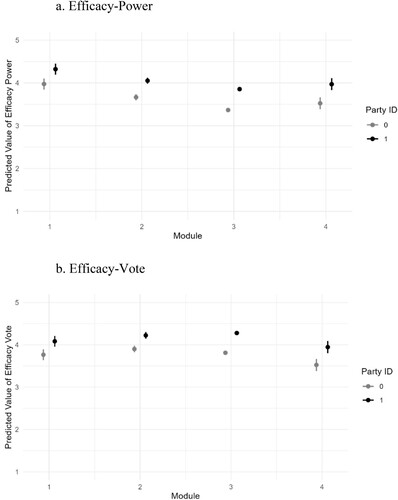

The predicted values in provide an alternate visualisation of the over-time trend of the interaction by plotting the predicted values of efficacy by party identification and CSES module. The findings demonstrate that regardless of the average levels of efficacy in society as a whole, the gap in predicted values of efficacy between those who lack identification with a party (Party identification = 0) and those who report a positive identification with at least one party (Party identification = 1) has increased over time. In other words, those who report feeling close to at least one party have increasingly higher levels of efficacy in recent years in comparison to those who lack any party identification.

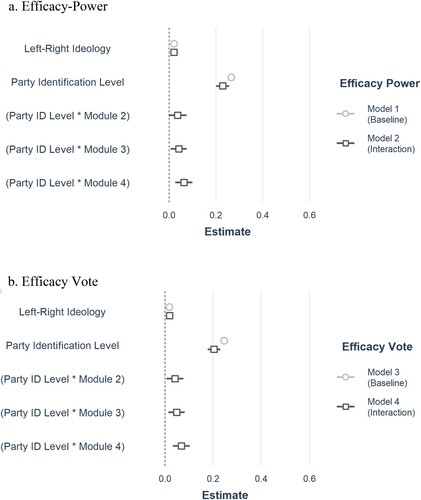

The next stage of the analysis tests the second and final hypothesis regarding whether levels of party closeness (PID level) have a stronger positive association with efficacy over time. The findings in indicate that party identification level indeed has a modestly increased association with both types of efficacy over time. Taken together with the findings related to Hypothesis 1, the results of testing Hypothesis 2 indicate that although the societal proportion of those who identify with at least one party has generally remained stable in the CSES data between 1996 and 2016, the modestly increasing proportion of those who report a higher level of closeness with a party is characterised by increased levels of efficacy over time. This relation holds for both indicators for efficacy.

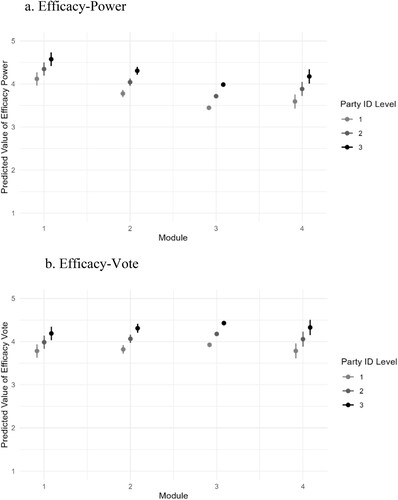

Following the coefficient plot of the interaction effects in to test H2 (‘The association between the level of party identification and political efficacy strengthens over the 1996–2016 observation period’), we again focus exclusively on the over-time interaction relations between the key variables of the study – now plotting in the interaction of PID level with CSES module on both types of efficacy. displays predicted values, which show a greater gap between those with different levels of PID over time, thereby supporting H2. Thus, for PID level the findings are consistent with the explanation that levels of closeness to a party contribute to the strengthened linkage between PID and efficacy over time.

The findings to this point are consistently similar for the two key outcome measures of efficacy power and efficacy vote. Our final analysis adds the variable of citizens’ perception of government performance to the model, with the noted caveat that this variable has a high proportion of missing data, as it was not included in all four CSES modules (see Appendix for multilevel regression tables). The findings show that the association between government performance and efficacy is the only coefficient that shows meaningful difference in the magnitude of the coefficient for efficacy power and efficacy vote, and the coefficient for efficacy vote is more than twice as large as the coefficient for efficacy power. This finding indicates that citizens’ perception of good government performance is more closely linked to their perception that voting makes a difference than their perception that the specific people in power is what matters. This finding points to an important area of future research on political efficacy that assesses the direction of causal relations to identify whether improved government performance motivates citizens to vote, or whether higher levels of citizen voting is what leads to improved government performance.

Discussion

At a time when the phrase ‘elections have consequences’ has become a slogan for motivating disaffected voters, the current study examines how citizens’ party identification relates to their sense of political efficacy in recent years. The results of the analysis indicate that party identification is positively associated with political efficacy, and that the strength of this association increased over the 1996–2016 observation period. Further, the findings on the connection between PID level and efficacy show that the association between citizens’ level of closeness to a party and their political efficacy has become stronger in recent years. The results do not indicate a linear trend, but instead show that the strength of the connection between party identification and political efficacy is greater in the two most recent modules of the CSES. In sum, the findings clarify that party identification remains strongly linked with efficacy – but only for those who identify with at least one party. This means that for those who lack identification with any party, their sense of political efficacy increasingly lags behind party identifiers in recent years. This finding has important implications for understanding the role of political parties in contemporary democracies. Even as their membership is stable or worse, our findings show that those who are closely identified with parties in recent years report even higher levels of self-perceived efficacy in the political system compared to those who lack this connection.

As noted, an important limitation of the current study is that the CSES cross-sectional data do not allow the assessment of causal relationships. We noted the common theoretical approach in the literature of presuming that feeling close to a political party leads to stronger feelings of political efficacy, even though the reverse causal logic is also plausible. Future research analysing panel data is therefore needed to determine the direction of causality. Another caveat is that the concept of ‘feeling close’ to a political party might have changed during the observation period due to party organisational changes or changing ideologies among the population (Scarrow, Citation2019). This shift might mean that those who reported that they felt ‘very close’ to a specific political party 20 years ago used the concept differently in comparison to contemporary respondents. Finally, variation across countries exists. The proportion of respondents that identify with being close to a political party differs substantially across the 20 countries. This suggests that different patterns might exist in relation to political efficacy when studies focus on a single case (or cluster of similar cases) with high or low levels of party identifiers nationally. Yet, the cross-sectional cross-time analysis provided here indicates that party identification, has stronger effect on attitudes of political efficacy.

Keeping these limitations in mind, the findings of the current study highlight that an important democratic linkage mechanism is still being offered by political parties, which is often overlooked due to the literature’s attention to long-term trends in the decline of party membership and party identity reaching back several decades. The findings of the present study show that citizens who do not feel that there is at least one political party that represents their interests and preferences increasingly lag behind those who identify with at least one party in their sense of political efficacy. For those who lack an identification with a party, even when they do vote, they may feel that their vote does not really make a difference, as they lack a sense of closeness with the offer they receive from the party system. Party identification, therefore, remains an important linkage mechanism, and our findings suggest that between 1996 and 2016 the strength of this identification became even more important in relation to citizens’ beliefs about whether elections have consequences.

An important implication of these findings is to consider the societal effects of the increased gap in efficaciousness between party identifiers and those who lack a sense of connection to any party. This finding highlights the potential that this increased gap over time between party identifiers and non-identifiers may also contribute to a greater gap in their support for democratic legitimacy in general. These findings also raise questions regarding the relevant pathways for contributing to citizens’ sense that their vote and who governs make a difference for democracy if they do not identify with even a single political party in their political system. A first path could be to strengthen the party system and its structures – a path that has received considerable attention in the literature over time (e.g. Gauja, Citation2015). A second path is to identify alternate mechanisms, organisations, or institutions through which people can gain a sense that their voice makes a difference to democratic governance. For example, Rasmussen and Reher (Citation2019) found that civil society engagement is strongly related to policy representation in Europe. Similarly, Henderson and Han (Citation2021) investigated the underlying mechanisms that may enhance political efficacy among state-level civic organisations in the United States, and their longitudinal evidence indicated that organisation members who develop relationships with association leaders have a strengthened sense of political efficacy. The current study suggests the importance of conducting further research on the viability of these and related paths in order to identify effective ways to strengthen citizens’ sense of connection to the political system.

Finally, the findings of this study highlight the importance of advancing research on political efficacy as part of a broader effort to investigate changing trends in democratic legitimacy. While political efficacy was a central topic in the classic early survey-based research on political attitudes, more recent literature tends to focus on related attitudes like political trust or satisfaction with democracy. The current study, however, suggests that political efficacy is an important attitudinal measure for the study of contemporary democratic functioning, as discussed in some of the earliest studies on voter attitudes (Campbell et al., Citation1954). An attitude like political trust may emphasise the allegiant side of political culture, while the findings of the current study confirm that political efficacy is clearly related to citizens’ political agency in terms of the strength of their connection to the political system. Thus, for both empirical and normative considerations, the findings of the current study emphasise the importance of future research on political efficacy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (423.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s ).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marc Hooghe

Marc Hooghe is a professor of political science at the University of Leuven (Belgium). He has published mainly on political participation and political trust.

Martin Okolikj

Martin Okolikj is post-doctoral research fellow in the Department of Comparative Politics at University of Bergen. His research interests are in comparative political behavior, with focus on elections, economy and political psychology.

Jennifer Oser

Jennifer Oser is an Associate Professor in the Department of Politics and Government at Ben Gurion University in Israel. Her research focuses on the relationships between public opinion, political participation, and policy outcomes.

Notes

1 For alternative views, see Lewis-Beck et al. (Citation2008), Okolikj and Hooghe (Citation2022), and for an overview of this topic, see Okolikj (Citation2023).

2 We use a baseline hypothesis to establish the overall association between partisanship and political efficacy, although we acknowledge that this association is to be expected.

3 We use phase 3 data released on 8 December 2020, The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES Integrated Module DATASET (IMD) [dataset and documentation]. 8 December 2020 version. doi:10.7804/cses.imd.2020-12-08. url: https://cses.org/data-download/cses-integrated-module-dataset-imd. The time periods of the four modules in the integrated dataset are Module 1 (1996–2001), Module 2 (2001–2006), Module 3 (2006–2011), and Module 4 (2011–2016).

4 We exclude Hong Kong and Kyrgyzstan because of high rates of nonresponse on key demographic variables. The 53 countries included in the full CSES sample are: Albania, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Montenegro, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, United States of America, and Uruguay.

5 The 20 countries in the main analytic sample are: Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, and United States of America.

6 This variation is however smaller within countries. For full descriptive results on this see Table A4.1 and Figure A4.1 in Appendix.

7 For cross country and within country variations in level of partisanship see Table A4.2 and Figure A4.2 in Appendix.

References

- Abramson, P. R., & Aldrich, J. H. (1982). The decline of electoral participation in America. American Political Science Review, 76(3), 502–521. https://doi.org/10.2307/1963728

- Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture. Princeton University Press.

- Banducci, S. A., & Karp, J. A. (2009). Electoral systems, efficacy, and voter turnout. In H.-D. Klingemann (Ed.), The comparative study of electoral systems (pp. 109–134). Oxford University Press.

- Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021226224601

- Bentancur, V. P., Rodriֳguez, R. P., & Rosenblatt, F. (2019). Efficacy and the reproduction of political activism: Evidence from the broad front in Uruguay. Comparative Political Studies, 52(6), 838–867. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018806528

- Blais, A., Guntermann, E., Arel-Bundock, V., Dassonneville, R., Laslier, J.-F., & Péloquin-Skulski, G. (2022). Party preference representation. Party Politics, 28(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820954631

- Campbell, A., Gurin, G., & Miller, W. (1954). The voter decides. Row & Peterson.

- Chamberlain, A. (2012). A time-series analysis of external efficacy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(1), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr064

- Craig, S. C., Niemi, R. G., & Silver, G. E. (1990). Political efficacy and trust: A report on the NES pilot study items. Political Behavior, 12(3), 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992337

- Dalton, R. J. (2002). The decline of party identifications. In R. J. Dalton & M. P. Wattenberg (Eds.), Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies (pp. 19–36). USA: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, R. J. (2016). Party identification and its implications. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.72

- Dalton, R. J., Farrell, D. M., & McAllister, I. (2011). Political parties and democratic linkage: How parties organize democracy. Oxford University Press.

- Dassonneville, R., Feitosa, F., Hooghe, M., & Oser, J. (2021). Policy responsiveness to all citizens or only to voters? A longitudinal analysis of policy responsiveness in OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 583–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12417

- Easton, D. (1965). A framework for political analysis. Prentice-Hall.

- Easton, D., & Dennis, J. (1967). The child's acquisition of regime norms: Political efficacy. American Political Science Review, 61(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953873

- Esaiasson, P., Kölln, A.-K., & Turper, S. (2015). External efficacy and perceived responsiveness: Similar but distinct concepts. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 27(3), 432–445. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edv003

- Finifter, A. W. (1970). Dimensions of political alienation. American Political Science Review, 64(2), 389–410. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953840

- Finkel, S. E. (1985). Reciprocal effects of participation and political efficacy: A panel analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 29(4), 891–913. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111186

- Fiorina, M. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. Yale University Press.

- Gauja, A. (2015). The construction of party membership. European Journal of Political Research, 54(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12078

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2006). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press.

- Hayes, B. C., & Bean, C. S. (1993). Political efficacy: A comparative study of the United States, West Germany, Great Britain and Australia. European Journal of Political Research, 23(3), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1993.tb00359.x

- Henderson, G., & Han, H. (2021). Linking members to leaders: How civic associations can strengthen members’ external political efficacy. American Politics Research, 49(3), 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X20972101

- Hooghe, M., & Oser, J. (2017). Partisan strength, political trust and generalized trust in the United States: An analysis of the general social survey, 1972–2014. Social Science Research, 68, 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.08.005

- Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604

- Iyengar, S. (1980). Subjective political efficacy as a measure of diffuse support. Public Opinion Quarterly, 44(2), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1086/268589

- Jacobs, L. R., Mettler, S., & Zhu, L. (2022). The pathways of policy feedback: How health reform influences political efficacy and participation. Policy Studies Journal, 50(3), 483–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12424

- Karp, J., & Banducci, S. (2008). Political efficacy and participation in twenty-seven democracies: How electoral systems shape political behaviour. British Journal of Political Science, 38(2), 311–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000161

- Katz, R. S., Mair, P., Bardi, L., Bille, L., Deschouwer, K., Farrell, D., Koole, R., Morlino, L., Müller, W., Pierre, J., Poguntke, T., Sundberg, J., Svasand, L., van de Velde, H., Webb, P., & Widfeldt, A. (1992). The membership of political parties in European democracies, 1960–1990. European Journal of Political Research, 22(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1992.tb00316.x

- Lane, R. E. (1959). Political life: Why people get involved in politics. The Free Press.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., Nadeau, R., & Elias, A. (2008). Economics, party, and the vote: Causality issues and panel data. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00300.x

- Lupu, N. (2015). Partisanship in Latin America. In R. Carlin, M. Singer, & E. Zechmeister (Eds.), The Latin American voter: Pursuing representation and accountability in challenging contexts (pp. 226–245). University of Michigan Press.

- Mair, P. (2014). On parties, party systems and democracy. ECPR Press.

- Mair, P., & van Biezen, I. (2001). Party membership in twenty European democracies 1980–2000. Party Politics, 7(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068801007001001

- Miller, W. E., Pierce, R., Thomassen, J., Herrera, R., Esaisson, P., Holmberg, S., & Webels, B. (1999). Policy representation in western democracies. Oxford University Press.

- Muirhead, R. (2006). A defense of party spirit. Perspectives on Politics, 4(4), 713–727. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592706060452

- Muirhead, R. (2014). The promise of party in a polarized age. Harvard University Press.

- Muirhead, R., & Rosenblum, N. L. (2020). The political theory of parties and partisanship: Catching up. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-020727

- Niemi, R. G., Craig, S. C., & Mattei, F. (1991). Measuring internal political efficacy in the 1988 national election study. American Political Science Review, 85(4), 1407–1413. https://doi.org/10.2307/1963953

- Okolikj, M. (2023). Economic voting. In M. Giugni & M. Grasso (Eds.), The encyclopedia of political sociology, (pp. 138–141). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781803921235.00041

- Okolikj, M., & Hooghe, M. (2022). Is there a partisan bias in the perception of the state of the economy? A comparative investigation of European countries, 2002–2016. International Political Science Review, 43(2), 240–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120915907

- Oser, J. (2023). Political efficacy. In M. Giugni & M. Grasso (Eds.), The encyclopedia of political sociology (pp. 388–390). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Oser, J., Feitosa, F., & Dassonneville, R. (2023). Who feels they can understand and have an impact on political processes? Socio-demographic correlates of political efficacy in 46 countries, 1996–2016. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 35(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edad013

- Oser, J., Grinson, A., Boulianne, S., & Halperin, E. (2022). How political efficacy relates to online and offline political participation: A multilevel meta-analysis. Political Communication, 39(5), 607–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2022.2086329

- Pateman, C. (1970). Participation and democratic theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Pollock, P. H. (1983). The participatory consequences of internal and external political efficacy: A research note. Western Political Quarterly, 36(3), 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591298303600306

- Powell, G. B. (2004). The chain of responsiveness. Journal of Democracy, 15(4), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2004.0070

- Powell, G. B. (2014). Conclusion: Why elections matter. In L. LeDuc, R. G. Niemi, & P. Norris (Eds.), Comparing democracies: Elections and voting in a changing world (4th ed.), (pp. 187–204). Sage publications Ltd.

- Quintelier, E., & van Deth, J. W. (2014). Supporting democracy: Political participation and political attitudes. Exploring causality using panel data. Political Studies, 62(S1), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12097

- Rasmussen, A., & Reher, S. (2019). Civil society engagement and policy representation in Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 52(11), 1648–1676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830724

- Scarrow, S. (2000). Parties without members? In R. J. Dalton & M. P. Wattenberg (Eds.), Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies (pp. 79–101). Oxford University Press.

- Scarrow, S. (2015). Beyond party members: Changing approaches to partisan mobilization. Oxford University Press.

- Scarrow, S. (2019). Multi-speed parties and representation. The evolution of party affiliation in Germany. German Politics, 28(2), 162–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2018.1496239

- Scarrow, S. E., & Gezgor, B. (2010). Declining memberships, changing members? European political party members in a new era. Party Politics, 16(6), 823–843. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809346078

- Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., & Poguntke, T. (2017). Organizing political parties: Representation, participation, and power. Oxford University Press.

- Shaffer, S. D. (1981). A multivariate explanation of decreasing turnout in presidential elections, 1960–1976. American Journal of Political Science, 25(1), 68–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2110913

- Thompson, D. M. (1970). The democratic citizen: Social science and democratic theory in the twentieth century. Cambridge University Press.

- van Biezen, I., Mair, P., & Poguntke, T. (2012). Going, going, … gone? The decline of party membership in contemporary Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 51(1), 24–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01995.x

- van Biezen, I., & Poguntke, T. (2014). The decline of membership-based politics. Party Politics, 20(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813519969

- van Haute, E., & Gauja, A. (2015). Party members and activists. Routledge.

- Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

- Webb, P., Farrell, D., & Holliday, I. (2002). Political parties in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford University Press.

- Whiteley, P. (2011). Is the party over? The decline of party activism and membership across the democratic world. Party Politics, 17(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810365505

- Whiteley, P., & Kölln, A.-K. (2019). How do different sources of partisanship influence government accountability in Europe? International Political Science Review, 40(4), 502–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118780445

- Wolak, J. (2018). Feelings of political efficacy in the fifty states. Political Behavior, 40(3), 763–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9421-9