Abstract

This paper explores gendered student learning in physical education (PE) viewed as a situated emerging process involving a triadic relationship between teacher, student(s) and forms of knowledge that are socioculturally bounded. It concerns gymnastic teaching and learning in Tunisia. It was conducted against the background of the Joint Action Studies in Didactics (JASD). Three Tunisian PE teachers having different expertise and experience and 12 male and female students with contrasted skill levels were observed within a gymnastics unit. Based on the video record of the lessons and on teachers' interviews, the findings stress the personal, institutional and cultural dimensions that shape the observed PE practices with special attention to the gendered content taught and learned. The use of the JASD framework highlights the intertwined processes during classroom interactions that influence the co-construction of gendered learning. It makes visible the interplay between the teacher's practical epistemology and the students' gender positioning and its consequence on inequalities in terms of students' learning and the maintenance of gender order in the gym.

Introduction

In physical education (PE), as in many other school subjects, an increasing volume of gender studies over the past years have recognised that pedagogical practices reproduce gendered aspects of the cultural heritage of societies (e.g. Davisse & Louveau, Citation1998; Ennis, Citation1999; Erraïs, Citation2002; Evans, Davies, & Penney, Citation1996; Flintoff & Scraton, Citation2006; Kirk, Citation2010; Larsson, Fagrell, & Redelius, Citation2009; Penney, Citation2002; Wright, Citation1997). In this paper we focus on the relationships between day-to-day school PE and physical culture in Tunisia, with special attention paid to the gendered content taught and learned. With a departure in the French didactique research tradition (Amade-Escot, Citation2006) of Joint Action Studies in Didactics (JASD) (Ligozat, Citation2011), the study seeks to understand how teachers and students co-construct both the context and the learning outcomes of their gendered relationships (Verscheure & Amade-Escot, Citation2007). The study also draws on Kirk's definition of physical culture as the corporeal discourses about the bodily practices organised, codified and institutionalised in a particular society just as in school PE, sport, exercises, leisure or dance (Kirk, Citation2010), as a way to understand to what extent cultural dimensions of the enacted curriculum generate unequal learning among students. Hence, students' learning should not be understood only in considering ‘the body in nature … (but also) the body in culture (the signifying and symbolising body)’ (Kirk, Citation2010, p. 99).

To account for how gendered knowledge content is co-constructed during Tunisian PE practices, attention is drawn to teachers' and students' joint action at the micro-level of the teaching and learning of a particular piece of the curricular content, the gymnastic handstand, which is, according to the national Tunisian curriculum, a major objective in PE teaching in upper secondary school. The choice of content area was also guided by the fact that gymnastics in PE historically has been a content that expressed bodily forms of femininity and masculinity (Kirk, Citation2010).

The purpose of our article is twofold: (1) To study the personal, institutional and cultural dimensions that shape Tunisian PE practices and their consequences on inequalities in terms of students' learning and the maintenance of gender order in the gym and (2) to address the relevance of the JASD framework for the theme of this special issue: ‘Learning movement cultures in PE practice’. In congruence with the JASD framework, the underlying thesis that guides this inquiry considers that analysing the intertwined teacher and student transactions related to the particular subject content at stake in a given situation is a relevant means for deciphering their experiences and the meaning constructed through these experiences. In relation to the framework, the following questions have guided our analysis: How does the teacher's practical epistemology have an effect on the evolving transactions related to the learning of a handstand? How does students' gender positioning impact the teaching? How can we understand the relation between teachers' practical epistemology and students' gender positioning in terms of a differential didactic contract?

Tunisian context of PE teaching

Since Independence (1956), a development process has been launched in Tunisia to favour equality between women and men in many areas. The Code of Personal Status is a series of progressive laws aimed at the institution of equality that has an important impact on Tunisian society. For instance, schooling is nowadays a fundamental right for all Tunisians without any discrimination based on sex, social origin, race or religion (Tunisian Law 2002-80). These revolutionary achievements remain unique in the Arab and Muslim world. Recently, the new Constitution of the Republic of Tunisia stated:

The State shall protect the acquired rights of women and work to strengthen and develop them. The State shall guarantee equal opportunities between women and men in access to all responsibilities in all areas. The state is working to achieve parity between women and men in elected assemblies. The State shall take the required measures to eliminate violence against women. (Article 46, 27 January 2014, our translation)

Outlines of the Tunisian national PE curriculum

In Tunisia, since the mid-eighties the national PE curriculum is multi-sports driven, characterised by short units of activity rooted in a ‘goal-oriented pedagogy’ (Zouabi, Citation2005). According to Ennis (Citation1999) this type of curriculum is generally ‘male oriented’, having as a consequence few opportunities for sustained instruction, little accountability for learning and unequal participation between students. One can add that the technical foci of Tunisian PE convey a mind–body duality philosophy whose source is in the contradictions of Tunisian body culture, between tradition and modernity (Bedhioufi, Citation2002; Erraïs, Citation2002). Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that Tunisia is a North African country where female schooling from primary school to university is very high compared to other countries in the region. Furthermore, PE is a mandatory school subject taught at each level by either female or male teachers who complete a three- to five-year university teacher education programme.

If single-sex classes in secondary schools were the PE standard recommendation before the 1980s, from this time on the Tunisian educational system has encouraged teaching in mixed classes. However, this political will towards coeducation stayed at an informal stage due to lack of application at school level. It is only since the end of the 1990s that PE has been progressively taught in mixed classes as a part of the overall education for young people, at times within a conservative and hostile environment. A survey conducted in 2002 suggested that most PE teachers are less than happy to teach mixed classes arguing about the difference of performance levels between male and female students (Zouabi, Citation2005).

In the ‘Official Directives for Physical Education and Sport’ (namely the national curriculum for secondary schools), the compulsory weekly time allotment for PE is between two and three lessons of 50 minutes (MJES, Citation1990). These directives, still in effect, list the following PE objectives: ‘development of motor skills, hygiene and health, social integration, improvement of individual technical performances in sports’. Related to the infrastructures and pedagogical equipment available, the subjects are track and field, games (handball, basketball and soccer) and gymnastics (Zouabi, Citation2005, p. 677). Acrobatic gymnastics is afforded an important content in Tunisia, where the basic skills to be learned are listed in detail including, for example ‘forward and backwards rolls, handstand, cartwheel, handspring, flyspring’, and so on. These objectives include institutionalised reference to the sport-gendered specification as ‘front and back walkover, pirouettes’ for female students versus ‘handstand full pirouette, dive roll’ for male students as examples. Likewise, one can say that the habits of teaching isolated gymnastic skills through different stations contribute to maintain gender-segregated sessions underpinned by discourses that emphasise gender differences in terms of attitudes, abilities and experiences.

In the ambiguous Tunisian context of tradition and modernity, gender issues in PE seem not be a real concern within the pedagogical field, even though a few sport sociologists have drawn attention to the tensions related to the subject, the body and cultural traditions (Bedhioufi, Citation2002; Erraïs, Citation2002; Lachheb, Citation2008). The fact remains that there is very little research on gender issue within PE practices in a Muslim country like Tunisia, apart from a few works recently presented at French-speaking conferences. The study presented in this article may be considered as the first attempt to scrutinise how gender order is produced in Tunisian mixed classes.

Exploring the interplay between teacher's practical epistemology and students' gender positioning using a didactical theoretical framework

The purpose of didactique research is to develop a better understanding of the teaching–learning processes within a comprehensive approach of how the social–cultural dimensions of the subject content shape teacher and students relationships. In this sense, its purpose is to capture in detail the enacted curriculum. Drawing on the idea that the knowledge taught and learned and all meanings associated are co-produced by teacher and students in culturally situated institutions, it takes into account simultaneously the teacher, the students and the particular situatedness of knowledge content as interrelated instances. In other words, this line of research considers that teachers' and students' practices are theoretically regarded as ‘joint actions’.

Since the mid-2000s, the study of joint action in didactics has been conducted in various subject disciplines in the French-speaking research area (Ligozat, Citation2011). These studies share a set of concepts and analytical tools that have been developed over time as a theoretical framework. Ligozat (Citation2011) reported that JASD is a pragmatist and social-interactionist approach to classroom practices, which has links with the theoretical works of Mead, Blumer, and Goffman as well as the one of Vygotsky. It has also commonalities with the ‘Swedish didactics research tradition’ of studying PE practices within a pragmatist and transactional theory of experience (Quennerstedt, Citation2013; Quennerstedt, Öhman, & Öhman, Citation2011; see also Ward & Quennerstedt, Citation2015) as well as in considering that students' learning emerges through social interactions including how the body is implicated in interactional situations (Larsson, Fagrell, & Redelius, Citation2009; see also Barker, Quennerstedt, & Annerstedt, Citation2015). From a theoretical standpoint, teacher and students ‘joint action’ stands for the situated interdependence of classroom actions on the one hand and the cultural, institutional and historical contexts in which the joint action occurs on the other. As a descriptive theoretical framework to analyse classroom interactions related to the knowledge at stake, the JASD offers a relevant lens to examine PE practice and to explore the constraints and possibilities of students' learning in settings that are always bounded by different physical cultures.

Overview of JASD framework

The JASD framework attempts to take into account the situated dimensions of teacher and students transactions concerning the transmission of a socio-historically built culture. Looking at classroom practices as being organically constituted by cooperative actions between participants, this framework acknowledges the idea that student's learning occurs within the unavoidable tension between individual agentivity and the cultural, institutional and historical contexts of the activity. However, joint action does not mean that participants (teacher and students) have the same goals or the same agendas. Negotiations and transactions occur between them about the particular piece of content at stake (Amade-Escot, Citation2006; Verscheure & Amade-Escot, Citation2007). Understanding the temporal dynamics of the whole process demands a fine-grained description of teacher's and students' actions and discourses related to the content embedded within an ongoing changing learning environment. To summarise, the purpose of JASD is to comprehend the logic of the didactical practice, understood in the sense of Bourdieu, that is how the practical concerns of everyday life (here in the classroom) condition the transmission and functioning of social or cultural forms (cf. Bourdieu, Citation1980).

Concepts used in this study

Against the background of the JASD framework, three main concepts are used in the study: (1) ‘Teacher's practical epistemology’, which permits identifying the cultural facets of knowledge privileged by teachers when teaching; (2) ‘Gender positioning’, which helps in understanding how individuals (particularly students) engage themselves in the practice and how they interpret the content; and finally, (3) ‘Differential didactical contract’, which accounts for the influence of didactical joint action on student's learning trajectories.

Teacher's practical epistemology

The concept of teacher's practical epistemology has close links to Bourdieu's logic of practice (1980). Borrowed from Sensevy (Citation2007) the concept underlines that teachers' views on the subject and the knowledge content they teach are part of their actions: ‘The teacher's epistemology is practical because it acts directly or indirectly in the everyday functioning of the class and because it is - in large measure - produced by and for practice’ (Sensevy, Citation2007, pp. 37–38). This definition marks the links of JASD with pragmatism. One should bear in mind that teacher's practical epistemology functions less as a knowledge base than as a tropism of action, which influences the ways the teacher supervises students' learning. The setting of a primitive didactic milieu (briefly defined as the set of material, symbolic and semiotic objects that characterise the initial setting by the teacher of any learning environment) as well as the teacher's discourses during classroom interactions documents her/his practical epistemology. In this sense, teacher's actions reveal what counts as valid knowledge and also modes of practice.

Teaching is then seen as a discursive act, where students' attention is directed towards certain events, questions and relationships while others are undervalued or ignored. The role of the teacher is to give the students directions that expose what counts as knowledge and appropriate ways of practicing in a specific social practice (here gymnastics as a part of Tunisian PE). This concept helps to understand what facets of knowledge are privileged by teachers when teaching physical activities, and how these facets impact students' actions. It is thus a useful concept to account for how the content is marked by gendered patterns of expectation and perception of the subject.

Gender positioning

As indicated earlier, PE research has pointed out the social construction of gendered bodies and minds through the curriculum. Female students do not benefit from equal opportunities to participate in PE. Bearing in mind that gender-biased curriculum and teacher's gendered interactions play an important role in the classroom, we assume that PE practices are constrained by the cultural and institutional contexts as well as the multiple micro-social interactions that affect classroom experiences. In that line, the concept of ‘positioning’, from Harré and van Langenhove (Citation1999), helps in reconsidering how gendered contents are enacted in classrooms. Drawing on the social, symbolic and interactional dimensions of human action, the importance of context and language, the authors contend that the concept of ‘positioning’ offers a dynamic alternative to the one of role. Their ‘positioning theory’, based on social constructionism, assumes among other things that human behaviour is goal-directed and constrained by group norms and that human subjectivity is a product of the history of each individual's interactions with other people. It draws on Vygotsky's ideas about the cultural embeddedness of thought and language and on Wittgenstein's concept of language games. For Harré and van Langenhove (Citation1999), ‘positions’ are thus not fixed but fluid and can change from one moment to the next, depending on the context through which the various participants take meaning from the interaction. Extending the idea of ‘positioning’ to students' gendered participation in PE practices, we elsewhere argued that ‘gender positioning’ is a fruitful concept to account for the transactional dynamics of the construction of gender inequities in day-to-day classroom life (Amade-Escot, Elandoulsi, & Verscheure, Citation2012).

Differential didactic contract

In order to highlight the intertwined role of teacher's practical epistemology and gender positioning in students' learning, the concept of differential didactic contract is used to conduct relational analyses at the micro-level of didactical transactions. The didactic contract refers to teacher and students implicit, reciprocal and specific expectations related to the content to be studied. In PE studies, it has been used to account for the evolution of student's learning through interactions (Amade-Escot, Citation2006, Hennings, Wallhead, & Byra, Citation2010; Wallhead & O'Sullivan, Citation2007; Verscheure & Amade-Escot, Citation2007). Drawing attention to the fact that social interactions consist of a continuous process of interpretation and (re)definition of both the context and the meanings, the notion of didactic contract emphasises that the meaning each student attributes to the situation in which she/he is involved depends on her/his personal experience in the immediate context, as well as in the social and institutional context in which the immediate context takes place. That is why the evolution of the didactic contract during didactical transactions is different among students. This brings up the notion of the ‘differential didactic contract’ (Schubauer-Leoni, Citation1996) which

is not implicitly negotiated with all the students of the classroom but with some groups of students which have diverse standings in the classroom. These standings are related to diverse hierarchies of excellence and are partially attributable to students' social backgrounds. (p. 160, our translation)

Materials and methods

In order to explore the enacted curriculum as well as the teaching and the learning going on (Amade-Escot, Citation2005; Quennerstedt et al., Citation2014), the methodological design is based on video observations of PE practices and teacher interviews during three gymnastics units of five lessons in the first year of Tunisian upper secondary school (15–16 years old, 10th grade). It particularly concerns the learning of the handstand, which according to the national syllabus is a skill that students should master at this age: ‘all students should be able to perform basic gymnastic skills, maintaining their balance and alignment in unusual positions as with the handstand’ (Tunisian Official Directives, MJES, Citation1990). At this level, the Tunisian curriculum does not require that students perform a floor routine even though a compulsory floor routine is a part of PE assessment for the final high school degree (Baccalauréat diploma, 12th grade). Three qualified PE teachers (Mohamed, Nada and Riadh) having different backgrounds in terms of gymnastics expertise and teaching experience, and 12 students designated by the teachers (two female and two male students with contrasted skill levels in each setting, ) were observed by the second author of this article (Elandoulsi, Citation2011).

Table 1. Observed students

Data collection

Data collection encompasses: (1) teacher interviews about general pedagogical values and objectives, (2) teacher's pre-lesson interviews, (3) video and audio recordings of lessons when the handstand is implemented, and (4) teacher post-lesson interviews. The purpose of teachers' interviews is to understand their perspectives on the teaching and learning process. The videos account for teacher and students transactions about the specific content (for details, see Amade-Escot, Citation2005; Quennerstedt et al., Citation2014; Verscheure & Amade-Escot, Citation2007).

Data analysis in relation to subject content

To document how the cultural and institutional dimensions of the curricular content influence the ways it is interpreted and (re)defined through the continuous process of didactical transactions, special attention is given to the teaching materials used (for a development, see the notion of ‘a priori analysis’ in Amade-Escot, Citation2005, pp. 135–136). The purpose of this analysis in this study is to grasp which type of content is embedded in the primitive didactic milieu in relation with teachers' practical epistemology as well as to identify which possible forms of gender positioning students may activate in such a learning environment. The primitive didactic milieu defined by the teacher has roots in her/his implicit theories about learning, about PE in general and, in this study, about gymnastics, all of them more or less supported by professional norms and institutional curriculum texts.

A brief outline points out that gymnastics encompass different forms of combinations of aesthetic and acrobatic dimensions (Aubert, Citation2003; Goirand, Citation1996). Relying on Mauss's concept (Citation1934) of the ‘techniques of the body’, Goirand (Citation1996) argues that the historical development of gymnastics skills during the twentieth century expressed the evolution of the cultural and legitimate forms of using the body: from force exhibition to the aesthetic combination of risk and originality. Those dimensions are also marked by gendered stereotypes (Kirk, Citation2010). ‘Gymnastics is a girls’ thing!’ pointed out Griffin (Citation1983) from an American student perspective. According to the literature, a feminine stereotype in gymnastics envisions the aesthetics of the movement as feminine, whereas a masculine stereotype values the acrobatic dimension. These stereotypes are of course reductionist, but Whitson (Citation1994) argues that ‘since the demands of every sport involve a particular balance between force and skill, it can be suggested that the more it is force that is decisive, the more a physically dominating hegemonic masculinity can be publicly celebrated’ (p. 363). These arguments lead to the idea that the gymnastic aesthetic and/or acrobatic dimensions may be valued (or not) by each teacher (in action and associated discourse) depending on her/his practical epistemology. Symmetrically, students may (or not) elicit in the ‘primitive didactic milieu’ proposed by the teacher, one of these dimensions or both, indicating (in actions and associated discourses) the meanings she/he is construing. It should be noted, however, that aesthetics and acrobatics are not dichotomous categories but should be understood as the two poles of a continuum as demonstrated by Aubert (Citation2003) in her study on students' forms of participation in school gymnastics. These clues drive the data analysis.

Data analysis of didactical transactions

With the purpose of comparing PE practices in the three settings, the analysis of teacher–students joint action focuses on (1) which dimension (acrobatic or aesthetic) students tend to favour when accomplishing their work, (2) how the teacher's actions value and promote the different forms of performing a handstand, and (3) which dynamics convey the evolution of the differential didactic contract.

Narrative records of the evolution of the didactical interactions related to the learning of the handstand were systematically created from the video data. They encompass the description of teacher's and students' actions and associated discourses. The analysis of the recurrent student's actions when performing the handstand enabled characterising her/his gender positioning with regard to the aesthetic and acrobatic dimensions valued. Although it is granted that gymnastics skills require both qualities, students do not necessarily identify this requirement in the didactic milieu. Aligned with the theoretical framework, it was considered that the recurrent selection of one or the other dimension, as well as from time to time both dimensions together when performing the handstand reveals aspects of what counts in students' learning experience, as well as the evolution of their gender positioning in the in situ context mediated by the teacher. For example, performing the handstand forward roll involves an ‘acrobatic’ dimension because it implies that the learner accepts to go over the inverted vertical position, just as to overcome ‘the fear of the fall in the back space’ (Aubert, Citation2003, p. 320) where the postural control of the body alignment plays a decisive role. This example highlights the fact that such a complex action encompasses not only behaviour but also emotion, postural adjustment as well as cultural embodiment of risk taking. To avoid a risk of misinterpretation of the bodily movement, the analysis also takes into account, as far as the data make it possible, the students' associated discourses. All this documents the differential dynamics of their learning trajectories.

The purpose of these rigorous methodological steps is to fulfil Rogoff's recommendation for educational research:

when both the individual and the environment are considered, they are often regarded as separate entities rather than being mutually defined and interdependent in ways that prelude their separation as units or elements…. Without an understanding of such mutually constituting processes, a sociocultural approach is at times assimilated to other approaches that examine only part of the package. (Rogoff, Citation1995, pp.139–141)

Findings

To account for how gendered knowledge content is constructed during the learning of the handstand in Tunisian PE practices, we first give an outline of the teachers' actions. Then we highlight the situated dimensions of teacher–students' joint action through a description of didactical transactions in each setting. Finally, we sum up the findings in a condensed matrix display with the aim of discussing how teacher's practical epistemology and student's gender positioning impact students' learning and maintain gender order in the gym.

Teachers' actions when teaching gymnastics

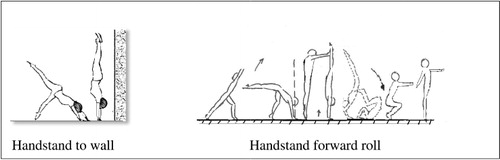

The classes observed belong to three high schools located in the ‘Kef governorate’, a north western region of Tunisia. Mohamed, Nada and Riadh planned a five-lesson gymnastic unit with the objective that students perform among other basic gymnastic skills a ‘handstand forward roll’. All lessons were organised with several stations. In each setting, groups of three to four students rotate from one station to another under the teacher's supervision. Once teachers have organised the class and the gymnastic stations (in terms of JASD, the primitive didactic milieus), they go from group to group and interact with students when needed. In such spatial context, almost all didactical joint action is related to a group, or to one of the other students in the group. For comparison purposes, the analysis focuses on the same two didactic milieus set up by the three teachers: ‘handstand to the wall’ and ‘handstand forward roll’ (see , borrowed from a Tunisian textbook).

Beyond these common practices, which shed light on the sociocultural features and gymnastic teaching traditions in Tunisia, teaching practices emerge as described below:

Mohamed, a football specialist with 7 years of service, considers that ‘Gymnastics as an individual sport is very difficult to teach, because of the weakness of students' skills’ (teacher's interview). In this gymnastics unit, only lesson 3, which last 80 minutes was dedicated to the learning of the handstand. The 19 students (7 female, 12 male) were asked to spread out in groups, which finally were five single-sex groups. During the lesson Mohamed gives the same instruction to all groups. The content related to the handstand is brought into molecular techniques (Kirk, Citation2010) that students repeat. Commenting on his lesson, Mohamed says: ‘The first learning task was to align the bottom over the hands, the second was to work on the leg push-off, the last one was to hold on handstand straight arms and look forward the hands’. Mohamed's discourse confirms that the teaching—always under his control—is based on a molecular approach of dividing and segmenting the content to be learned (Rovegno, Citation1995).

Nada has taught PE for 3 years and has a strong background in gymnastics as a competitor and judge at the university level. She likes to teach gymnastics but does not feel confident having a mixed class of 25 students (18 female, 7 male). She expresses that ‘gymnastics should be mandatory in PE because its purpose is to improve health and motor coordination’ and ‘doing gymnastics needs mental qualities’ (teacher's interview). She deplores the lack of gymnastic equipment. Her gymnastics unit is structured by a diagnostic evaluation (lesson 1) and a short floor routine assessment including the ‘handstand forward roll’ (lesson 5). The three other 50-minute lessons are dedicated to basic skills including the handstand: ‘a key element to produce a gymnastic routine’ (post-lesson 3 interview). For Nada, all students should have the opportunity to experiment with ‘the inverted vertical position because it is at the core of gymnastics experiences’ (pre-lesson 1 interview). She deliberately organises her class with the male students on one side of the gym and the female students on the opposite, each of them grouped into skill-level groups. Four stations are provided on both sides, two of them are related to the handstand. At each station a poster presents a schema of the gymnastic skill involved, how it should be performed, the spotting instructions and the correct achievement criteria. These posters are pieces of the primitive didactic milieus, which devolve some responsibilities to the students (in this case reading, understanding what is expected, etc.). Nada's actively supervises the two stations: ‘handstand to wall’ and ‘handstand forward roll’. During the unit Nada feels increasingly upset by six male students who progressively disengage themselves from the specified work. She concentrates on in-depth monitoring of female students while male students are more or less engaged in self-learning. Her discourse on teaching gymnastics is about safety and fears:

handstand is a non-habitual body position and it's scary. The fear of backward space has an impact on low skilled students…. Females are less enthusiastic than males to act in such scaring environment that is why I systematically organise spotters for them. (post-lesson 3 interview)

After the diagnostic test, I will focus on the handstand as soon as possible, because it is the most important skill in gymnastics. My objective is a good solid tight handstand and the best way to get comfortable is to do a lot of handstands. (pre-lesson 1 interview)

To sum up, each teacher tries to bring into play the curricular content related to the handstand. Nevertheless, the ways each of them accounts for their actions in the interviews underline some premise of their practical epistemology. It gives some insight into her/his understanding of what gymnastics is on its own practical and socially constituted terms. At this stage, it appears that the experiences, the values and what is privileged by teachers' discourses concerning gymnastics let us think that their teaching might be quite different according to female and male students.

Teacher and students transactions

This section argues that gendered learning outcomes are the result of the differential evolution of the didactic contract implicitly negotiated between teacher and students. The detailed analysis of didactical transactions supports the idea that gender positioning gives attention to how knowledge content is enacted through micro-social transactions within an evolving didactic milieu in which some masculine versus feminine forms of actions may be valued (or not) by either the teacher and/or the student.

Mohamed and students didactical joint action during lesson 3

Mohamed has very few interactions with students compared to the two other teachers and not any with Sonia designated as a low-skilled student (). We might interpret that Mohamed, having a weak expertise in gymnastics, does not really feel confident in monitoring students' actions. His few verbal interactions are always related to the acrobatics dimension of the handstand: ‘you should throw the leg and then roll’. For example, to Salim who does not reach the handstand position, he says: ‘go go, push on your leg’; ‘hey guys, make explosive push’. His discourse is always related to some technical dimension in terms of ‘strength’ or ‘force’ that illustrate, according to Whitson (Citation1994), how masculinity is publicly celebrated in the class.

Table 2. Condensed matrix display of the 12 students' cases

The case of Ouissal, who is considered by Mohamed as a good student of gymnastics, is significant of the gendered transactional climate of the lesson. Ouissal is very engaged at all times. Moreover, she is willing to help other students during the assigned work, indorsing a responsibility in relation to the knowledge at stake. The video shows 6 attempts at the ‘handstand forward roll’ versus 18 at the ‘handstand to the wall’. In both didactic milieus, she favours the aesthetic dimension of the gymnastic skills, with body alignment, feet and toes pointed. Over the attempts, she gradually performs a tight handstand. Mohamed asks her to demonstrate to the class and comments on her performance saying: ‘you should be as strong as she is’. At the end of the lesson Ouissal is able to reach the handstand body position at almost every attempt; however, in the handstand forward roll she continuously avoids the risk of engaging herself in the ‘back space’ to initiate the rotation. She looks reluctant to curl up her back and to lose her visual control of action. Repeatedly, Ouissal's actions are to reach the handstand position but not the split back. Doing this she introduces a breach in the didactic contract. Mohamed never interacts with her on this theme as if, one may interpret, the handstand forward roll is not an objective for a female student. Thus, Ouissal does not find any support or opportunity to experience the acrobatic dimension of a gymnastic movement. An implicit differential didactic contract emerges through transactions about what is valuable gymnastic knowledge for her in comparison with the one implicitly negotiated with male students who are called upon to perform more acrobatic gymnastics.

Nada and students didactical joint action

As already pointed out, Nada breaks her class into single-sex groups. She briefly defines what is expected to be performed and devolves to the students the responsibility to check other clues on the posters. When defining, Nada puts emphasis on what counts for her: ‘to be able to reach and maintain the handstand position with a complete alignment of arms body and legs … what I want is tightness!’ (lesson 2, ‘handstand to wall’). The analysis of her discourse throughout the lessons shows that Nada is privileging the aesthetic dimension of the gymnastic elements she teaches. Her attention to a ‘perfect body position’ expresses what Nada considers to be practicing gymnastics. Her experience as a competitor and a judge might explain her focus. This conventional viewpoint has an impact on her teaching. For instance, six of the seven male students seem not share the same meaning of what is gymnastic practice: first, they transform the primitive didactic milieus to be engaged in more acrobatic ways (e.g. extending the run to perform a handspring, adding a mat for when they fall on their back) and then, they progressively disengage themselves as a mark of boredom. Nada does not interact much with the male students ().

Nada directs her teaching to the groups of female students, especially to Fatma, a low-skilled student, but ‘a good thoughtful girl, who will improve during the unit’ (post-lesson 1 interview). The video record shows an assiduous student. Since the beginning of the unit, Fatma practiced consistently (42 attempts at the handstand to wall but only three attempts at the handstand forward roll). She benefits from 25 teacher's verbal interactions including teacher's spotting during the three lessons. An important improvement in reaching the handstand position when performing ‘handstand to wall’ appears in lesson 3. After six unsuccessful attempts that allow her to reach an angle of 70 degrees to the floor, Nada comes and asks Fatma to ‘repeat again’. Fatma says ‘Madam I'm scared’. Nada then initiates a long one-to-one transaction with her. She takes a mat from the floor and puts it against the wall, modifying the initial didactic milieu, while she asks the two other female students to hold it. She monitors Fatma’ actions, spotting her up to the vertical position while saying ‘be tight’, then ‘stretch your legs’ and ‘as tall as possible ... toes pointed’. After eight monitored attempts, Fatma succeeds by herself and gives a big smile to the group. The teacher's actions in modifying the learning environment (the mat against the wall, the verbal interactions and encouragement as well as the non-verbal interactions when spotting) create a specific didactic milieu that helps Fatma to overcome her legitimate fear. It should be noticed that Fatma finds opportunities in the didactical joint action as her goal is aligned with that of her teacher: to perform a perfect body position. However, Fatma, in contrast with Faten () never explores the acrobatic dimension of the gymnastic movement and her teacher never asks for it. The data analysis of the three lessons confirms that Nada and Fatma, whatever the specific gymnastic content at stake is, activate a feminine gender positioning that helps the latter to improve.

Riadh and students didactical joint action

Riadh's verbal and non-verbal interactions focused on the acrobatic dimensions of the handstand. At the beginning of the unit, this teacher asks the mixed groups of high-skilled students ‘to perform a handstand forward roll, without any spotter’. He then puts the focus on ‘the kinetic energy’ used to reach the position and on the control of the curl up of the head and shoulders ‘to generate roll speed’. These foci help Hana and Khaled (high-skilled female and male students) to perform better, both engaging themselves in the didactic contract with consistency and diligence. Throughout the lessons, the two students not only favour the acrobatic dimension as valued by Riadh's actions but also cleverly decode the subtleties of the knowledge content embedded in the primitive didactic milieus (the twofold aesthetic and acrobatic dimensions of handstand). They also participate in the process when spotting each other's activating a ‘balanced gender position’ (Verscheure & Amade-Escot, Citation2007). Imen, considered by Riadh as a ‘very low skilled female’ does not receive much attention from him () and participates as a competent bystander (Griffin, Citation1983). By contrast, Hichem's case highlights how teachers' expectations may help student's learning. Hichem's attempts mark the value he gives to the acrobatic dimension of the handstand even though at the beginning of the unit he is unable to perform it: this student always throws his first leg without control, goes over the vertical position and falls on his back repeatedly. This low-skilled male student received a lot of attention from Riadh (). The dynamics of their joint action, which refines the primitive didactic milieu, allows Hichem to improve in performing the handstand. Throughout the unit, this student systematically adopts a masculine stereotyped gender position that echoes with the one Riadh is privileging when teaching. Implicitly, a differential didactic contract appears sustained through very specific interaction patterns where Hichem develops a studious attitude that fulfils the demand of his teacher.

Concluding discussion

The results of the study portray the dynamics of the differential didactic contract and its consequences in terms of the gendered learning trajectories between and among students. The analysis of the 12 students' cases as summarised in suggests that student's gender positioning and teachers' privileging impact how individuals engage themselves in the situated teaching and learning processes in ways that maintain subtle forms of gender order in the gym.

These findings allow us to comprehend how classroom interactions are modelled through forms of participation and positioning with regard to the handstand (as a specific piece of curricular content), which are not independent of the teacher's practical epistemology. Mohamed, Nada and Riadh do not value the same cultural facets of gymnastic knowledge within the larger physical culture. Their actions play a leading role in orienting students learning, in order to tell them what counts as knowledge and appropriate gender ways of practicing gymnastics. Teachers, when privileging one or the other dimensions of the social practice (here the acrobatic and/or aesthetic dimensions of gymnastics), open or close opportunities related to the gendered nature of knowledge enacted through these tacit and implicit transactions. As individuals, students (as well as teachers) are moulded into a body culture, which is always complex and multiform. Thus, they activate forms of positioning (Harré & van Langenhove, Citation1999) depending on the situated context at hand but also constrained by group norms and valued cultural practices. The findings also bring to light that ways of knowing in PE classrooms emerge from interactions wherein individual subjectivity, which is the product of the history of each individual's interactions with others, modifies and colours the forms of engagement in learning a subject matter. These share similarities with the ones of Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius (Citation2009) when they argue that PE teachers are both paying tribute to masculinity and at the same time are trying to be benevolent towards girls. However, this study suggests that in addition to such schema, gender order in the gym also implies norms of excellence that are institutionally and culturally valued. Our findings from the detailed analysis of classroom transactions support the idea that the observed dynamics combine gender and excellence-ability in student's positioning. For example, female or male high-skilled students benefit more from the teaching in terms of their positive engagement in the differential didactic contract (). This intricate and unequal process requires certainly further studies but, within the limitation of this one, the data demonstrate how individual, institutional and cultural dimensions that shape Tunisian PE practices produce various forms of gendered learning among students.

In conclusion, within the context of Tunisia, the paper has shown how the studying of classroom transactions in day-to-day practices through the JASD perspective makes visible the interplay between the teacher's practical epistemology and the students' positioning related to the subject content and its unequal consequences in terms of students' learning and the maintenance of gender order in the gym. The JASD framework discloses how the content of lessons is brought into play in PE practices. Knowledge construction at school is a result of in situ social interactions and, at the same time, classroom activities work with referenced knowledge, which is knowledge recognised by any institution (society, community of practice, group of students, etc.) as adequate knowledge to fully participate therein. Enlightening how individuals co-produce the conditions in which teaching and learning a particular content may or may not contribute to all students' empowerment draws attention to the possible limitations due to the potential discrepancy between the physical activities institutionally promoted by any curriculum and those that students identify to be culturally significant for them. The various gendered learning trajectories uncovered in the observed lessons indicate that all students' empowerment requires also teachers' strong and exacting pedagogical content knowledge that should encompass meanings, knowledge, skills, know-how, dispositions that are to be learned by students, including individual and societal concerns and values. This broad definition stands up for the idea of PE as culture that has implication for teacher education (Kirk, Citation2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the guest editors of this special issue for their supportive comments and their editing suggestions on the earlier draft of this paper.

References

- Amade-Escot, C. (2005). The critical didactic incidents as a qualitative method of research to analyze the content taught. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 24(2), 127–148.

- Amade-Escot, C. (2006). Student learning within the didactique tradition. In D. Kirk, M. O'Sullivan, & D. Macdonald (Eds.), The handbook of physical education (pp. 347–365). London: SAGE.

- Amade-Escot, C., Elandoulsi, S., & Verscheure, I. (2012). Gender positioning as an analytical tool for the studying of learning in physical education didactics. Paper presented at the European Conference on Educational Research, Cádiz, 18–21 September.

- Aubert, J. (2003). Représentations et conduites d'élèves de collège en gymnastique scolaire [Students' representations and performance in school gymnastics]. In C. Amade-Escot (Ed.), Didactique de l'éducation physique – Etat des recherches (pp. 309–323). Paris: Editions Revue EP.S., Recherches et Formation.

- Barker, D., Quennerstedt, M., & Annerstedt, C. (2015). Learning through group work in physical education: A symbolic interactionistic approach. Sport, Education and Society, 20, 604–623. doi:10.1080/13573322.2014.962493

- Bedhioufi, H. (2002). Attitudes et représentations liées aux pratiques sportives de la femme tunisienne. In B. Erraïs & M.C. Lanfranchi (Eds.), Femmes et sport dans les pays méditerranéens (pp. 272–277). Nice: AFSCM, European Council.

- Bourdieu, P. (1980). Le sens pratique. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit.

- Davisse, A., & Louveau C. (1998). Sports, école, société : la différence des sexes. Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Elandoulsi, S. (2011). L’épistémologie pratique des professeurs : Effets de l’expérience et de l’expertise dans l'enseignement de l’Appui Tendu Renversé en mixité. Analyse comparée de 3 enseignants d’EPS en Tunisie ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Université Toulouse Le-Mirail, Toulouse.

- Ennis, C. D. (1999). Creating a culturally relevant curriculum for disengaged girls. Sport, Education and Society, 4, 31–49. doi:10.1080/1357332990040103

- Erraïs, B. (2002). Culture patriarcale méditerranéenne, corps féminin tabou et pratique sportive. In B. Erraïs & M. C. Lanfranchi (Dir.), Femmes et sport dans les pays méditerranéens (pp. 23–32). Nice: AFSCM, European Council.

- Evans, J., Davies, B., & Penney, D. (1996). Teachers, teaching and the social construction of gender relations. Sport, Education and Society, 1, 165–185.

- Flintoff, A., & Scraton, S. (2006). Girls and physical education. In D. Kirk, M. O'Sullivan, & D. Macdonald (Eds.), Handbook of research in physical education (pp. 767–783). London: SAGE.

- Goirand, P. (1996). Evolution historique des objets techniques en gymnastique [Historical development of acrobatic gymnastics techniques]. In P. Goirand & J. Metzler (Eds.), Techniques sportives et culture scolaire: une histoire culturelle du sport [Sport techniques and school culture: a cultural history of sport] (pp. 99–144). Paris: Editions Revue EP.S.

- Griffin, P. S. (1983) “Gymnastics is a girl's thing”: Student participation and interaction patterns in a middle school gymnastics unit. In T. Templin & J. K. Olson (Eds.), Teaching physical education (pp. 71–85). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Harré, R., & van Langenhove, L. (1999). Positioning theory: moral contexts of intentional action. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hennings, J., Wallhead, T. L., & Byra, M. (2010). A didactic analysis of student content learning during the reciprocal style of teaching. Journal on Teaching Physical Education, 29(3), 227–244.

- Kirk, D. (2010). Physical education futures. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

- Lachheb, M. (2008). L'idéaltype du corps dans l'enseignement de l'éducation physique tunisienne contemporaine. Education et Sociétés, 22(2), 145–159.

- Larsson, H., Fagrell, B., & Redelius, K. (2009). Queering physical education. Between benevolence towards girls and a tribute to masculinity. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 14(1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/17408980701345832

- Ligozat, F. (2011). The development of comparative didactics & joint action theory in the context of the French-speaking subject didactiques. Paper presented at the European Conference on Educational Research, Berlin, 13–16 September.

- MJES (1990). Instructions Officielles de l’Education Physique et Sportive dans l'enseignement secondaire. Ministère de la Jeunesse, de l’Enfance et du Sport, Direction de l’Education Physique. Tunis: Centre de documentation et d'information.

- Mauss, M. (1934). Les techniques du corps. In M. Mauss (Ed.), Sociologie et anthropologie (pp. 363–386). Paris: PUF.

- Penney, D. (2002). Gender and physical education. Contemporary issues and future directions. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Quennerstedt, M. (2013). Practical epistemologies in physical education practice. Sport, Education and Society, 18, 311–333.

- Quennerstedt, M., Annerstedt, C., Barker, D., Karlefors, I., Larsson, H., Redelius, K., & Ohman, M. (2014). What did they learn in school today? A method for exploring aspects of learning in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 20(2), 282–302. doi:10.1177/1356336X14524864

- Quennerstedt, M., Öhman, J., & Öhman, M. (2011). Investigating learning in physical education – a transactional approach. Sport, Education and Society, 16, 159–177.

- Rogoff, B. (1995). Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In J. V. Wertsch, P. del Rio, & A. Alvarez (Eds.), Sociocultural studies of mind (pp. 139–164). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rovegno, I. (1995). Theoretical perspectives on knowledge and learning and a student teacher's pedagogical content knowledge of dividing and sequencing subject matter. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 14, 283–304.

- Schubauer-Leoni, M. L. (1996). Etude du contrat didactique pour des élèves en difficulté en mathématiques. Problématique didactique et/ou psychosociale. In C. Raisky & M. Caillot (Eds.), Au-delà des didactiques le didactique: débats autour de concepts fédérateurs (pp. 159–189). Bruxelles: De Boeck, Perspectives en éducation.

- Sensevy, G. (2007). Des catégories pour décrire et comprendre l'action didactique. In G. Sensevy & A. Mercier (Eds.), Agir ensemble. L’action didactique conjointe du professeur et des élèves (pp. 13–49). Rennes: Presses Universitaires.

- Verscheure, I., & Amade-Escot, C. (2007). The gendered construction of physical education content as the result of the differentiated didactic contract. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 12(3), 245–272. doi:10.1080/17408980701610185

- Wallhead, T., & O'Sullivan, M. (2007). A didactic analysis of content development during the peer teaching tasks of a sport education season. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 12(3), 225–243. doi:10.1080/17408980701610177

- Ward, G., & Quennerstedt, M. (2015). Knowing in primary physical education in the UK: Negotiating movement culture. Sport, Education and Society, 20, 588–603. doi:10.1080/13573322.2014.975114

- Whitson, D. (1994). The embodiment of gender: discipline, domination and empowerment. In S. Birrell & S. Cole (Eds.), Women, sport and culture (pp. 353–371). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Wright, J. (1997). The construction of gendered contexts in single sex end co-educational physical education lessons. Sport, Education and Society, 2, 55–72.

- Zouabi, M. (2005). Sport and physical education in Tunisia. In U. Pühse & M. Gerber (Eds.), International comparison of physical education. Concepts, problems and prospects (pp. 673–685). Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport.