ABSTRACT

Educational discourse is becoming increasingly globalized. This trend is particularly pronounced in the area of assessment, where notions of accountability, comparability, and competition have become prevalent in many countries. Scholars have critiqued this trend. They contend that global assessment discourse provides educators with decontextualized terms and concepts for teaching, which have little connection to the lives of learners. The specific purpose of the paper is to critically consider the encounter between global PE assessment discourse and local educational traditions. The International Association for Physical Education in Higher Education (AIESEP) position statement on physical education assessment is taken as a case of global assessment discourse and is considered in relation to Swedish physical education traditions. Robertson’s [(1995). Time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity. In M. Featherstone, S. Lash, & R. Robertson (Eds.), Global modernities. Sage] notion of glocalization is employed as a theoretical perspective. We begin our consideration by outlining general tenets of the position statement and of Swedish physical education. We then examine areas of synergy and tension. This examination is structured according to six issues: (1) rationales for assessment; (2) underlying views of learning; (3) teachers’ role in teaching and assessment; (4) positioning of students; (5) understandings of subject content, and; (6) the ways in which contextual conditions are framed. Using a glocalization perspective, we raise three issues that have a strong bearing on the encounter between global discourse and local educational traditions and which provide insights into how assessment discourse within PE can be understood. These issues concern: (1) the risk of local educational traditions being appropriated by global assessment discourse; (2) the relation between assessment homogeneity and local diversity; and (3) meaningful PE practices. The paper is concluded with general reflections concerning implications for research and practice.

Introduction

Scholars have suggested that educational discourse is becoming increasingly globalized (Lingard, Citation2021a; Spring, Citation2008; Stromquist & Monkman, Citation2014). Exley et al. (Citation2011), for example, claim that ideas and values concerning education are circulating between international policy arenas, with some nations ‘exporting’ ideas and values while others ‘import’ them (p. 213). Exley et al. (Citation2011) contend that educational globalization is particularly pronounced in the area of assessment, where notions of accountability, comparability, and competition have become prevalent. Torrance (Citation2011) concurs, suggesting that internationally, the development of a standards-based, test-driven education system has been ‘the key policy objective’ in the last two decades (p. 468, our emphasis). Scholars have also pointed to projects such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo), the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and the Institute of Education Sciences’ (IES) Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) as prime examples of the globalization of assessment discourse (Engel & Rutkowski, Citation2020; Lewis et al., Citation2016).

The idea of assessment discourse proliferating across national and cultural borders has attracted critique from scholars concerned with the effects of neoliberalism on education (Gray et al., Citation2018; Rizvi, Citation2017; Torrance, Citation2012, Citation2017). According to Sundberg and Wahlström (Citation2012), organizations such as the OECD are now influential in constructing educational indicators and performance measures and developing concepts such as ‘standards’ and ‘choice’ (p. 344). These efforts constitute attempts to define ‘what counts as valid knowledge’ and can provide ‘decontextualized scripts for teaching’ (Sundberg & Wahlström, p. 344; see also Rutkowski, Citation2015). For Sundberg and Wahlström, such scripts have little connection or relevance to the lives of learners, especially as local contexts become increasingly diverse (see also Lipman, Citation2004). El Bouhali (Citation2015) claims that global assessment programs often have conflicting agendas and while programs purportedly serve students and the communities they live in, they tend to work in the interests of international organizations. Pike (Citation2015) expands on this idea, suggesting that curricula are increasingly oriented to a free-market economy (see also Hursh, Citation2007; Rutkowski, Citation2015). With this orientation, the STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) are prioritized over ‘softer’ subjects in the humanities and social sciences, and an education is increasingly seen as something to be procured by market-oriented individuals rather than a civic process (Pike, Citation2015).

Physical education (PE) has not been included in international large-scale assessments (or ILSAs – Rutkowski et al., Citation2020) such as PISA and TIMMS, which have concentrated predominantly on reading, mathematics, and science knowledge (Spord-Borgen & Hjardemaal, Citation2017). Nonetheless, PE has been influenced by global assessment discourses (Hay & Penney, Citation2013). Several scholars have drawn attention to the introduction of high-stakes assessment in PE (Rink & Mitchell, Citation2002; Thorburn, Citation2007) and the increasing significance that issues such as accountability and comparability in assessment has for PE practices (Dyson, Citation2014; Macdonald, Citation2011). While high stakes assessment – usually in the form of examinations in senior secondary school – is generally organized at the state or national level and is thus not the same order of development as the ILSAs described above, assessment research in PE does point to increasing prominence of assessment discourse in different national contexts. Recently, the International Association for Physical Education in Higher Education (AIESEP) released a position statement on assessment in PE (Citation2020). The stated purpose of the position statement is fourfold:

(1) To advocate internationally for the importance of assessment practices as central to providing meaningful, relevant and worthwhile physical education; (2) To advise the field of PE about assessment-related concepts informed by research and contemporary practice; (3) To identify pressing research questions and avenues for new research in the area of PE assessment; (4) To provide a supporting rationale for colleagues who wish to apply for research funds to address questions about PE assessment or who have opportunities to work with or influence policy makers (AIESEP, Citation2020, preface).

Glocalization – a way of understanding the global and the local

Robertson (Citation1995) introduced the notion of glocalization out of dissatisfaction with the way globalization was being used in popular and scientific literature. Essentially, he suggested that globalization had come to refer to a process of cultural homogenization that left little room to consider local, spatial, or historical dimensions of social change. Such a perspective was, for Robertson, misleading and risked providing social observers with deterministic explanations of social phenomena. As an alternative, Robertson (Citation1995) employed glocalization to suggest that processes of homogenization and heterogenization are both features of contemporary societies and that the tendencies are ‘mutually implicative’ (p. 27). Rather than opposites, the processes of homogenization and heterogenization that occur when discourse spreads across national borders are complementary and interpenetrative – even if they can work against each other at certain historical moments (see Lingard, Citation2021b). From a glocal perspective, the global and the local need to be understood dialectically. Conceptions of (local) nationalism and indigeneity are for example, contingent upon, and defined in relation to, encounters with global others.

Glocalization has proven a useful concept to consider the local and global within educational research (Are Trippestad, Citation2015). Brooks and Normore (Citation2010), for example, provide a glocal perspective on educational leadership. They put forward different glocal literacies, suggesting that grasping the interconnections between local and global politics, pedagogies, and technologies is increasingly important for educators (Brooks & Normore, Citation2010, p. 73). Weber (Citation2007) examines the dialectic of the local and the global in the context of South African educational reform. His analysis illustrates how educational practices in South Africa have been shaped by many of the trends identified as ‘global’ in educational literature (performance cultures, cuts to education spending, accountability through high stakes testing, loss of teacher autonomy, for example). He stresses that reading these trends simply as global conceals the ways in which the context under examination diverges markedly from the contexts in which much of the globalization scholarship has been conducted.

Our focus in this paper is Sweden, a nation that is industrialized and Western. In this respect, our context is close to the foci of many of the scholars cited at the outset of the paper. Based on a glocalization perspective, our contentions are that (1) the Swedish educational context has a tradition that is mutually implicative with global assessment discourse, and (2) that considering how national educational traditions relate to globalizing assessment discourse can provide insights into why certain practices, questions and debates arise at this particular point in time. In this respect, a glocalization perspective can provide a vantage point from which to consider PE anew. As indicated, we are specifically interested in how the AIESEP position statement on PE assessment articulates with Swedish PE. In the next section, we consider the position statement in detail.

The AIESEP position statement on PE assessment

The AIESEP position statement was created as the result of the AIESEP specialist seminar ‘Future Directions in PE Assessment’ in 2018. The seminar brought together leading scholars in the field to present and discuss ‘evidence-informed’ views on PE assessment (AIESEP, Citation2020). The participants of the seminar represented their own localities. Thus, from the outset, the position statement cannot be regarded as a supranational text, established by policy makers, but rather a product of specialists’ efforts whose views are based on local research. This means that local research influenced global discourse which in turn is designed to guide local policy and practice.

The position statement acknowledges a growing emphasis on assessment in education and an increasing global prominence of accountability and standardization discourses within education. The statement takes several problems identified in research on PE assessment as a point of departure (e.g. López-Pastor et al., Citation2013). The first is poor instructional alignment in PE, where educational aims, methods of achieving aims through teaching and learning activities, and assessment of these aims do not fit together (Borghouts et al., Citation2017). Poor instructional alignment is closely related to a second problem, that is, students’ uncertainty regarding PE’s goals and grounds for assessment. Referring to research, the statement suggests that students rarely understand the criteria that are used as the basis for assessment and that students’ perspectives of grading are often inconsistent with their conceptions of achievement in PE (Redelius & Hay, Citation2012). Third, the statement proposes that there is a high prevalence of product-oriented assessment practices in PE such as fitness testing and the assessment of isolated technical skills (Lorente-Catalán & Kirk, Citation2016; Penney et al., Citation2009). Again, drawing on research, the statement claims that these forms of assessment lack meaning for students because they do not relate to the world outside of schools (AIESEP, Citation2020).

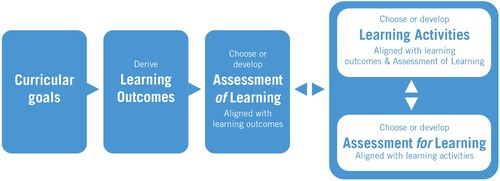

To resolve these problems, the statement puts forth three related recommendations. These recommendations essentially constitute the statement’s position. The first recommendation is that instructional alignment be assured by means of an instructional model (see ). According to the model, the intended learning outcomes and ways of conducting an assessment of learning are to be outlined for students in advance. Then, assessment for learning (AfL) is to be integrated in the learning activities to promote student learning. The two-way arrows in indicate that assessment for and of learning should be viewed as a reciprocal process.

Figure 1. Sequence for the planning and design of an instructionally aligned curriculum (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 7).

Second and related, the statement suggests that PE teachers need to be better equipped to work with students and assessment. Work with students and assessment involves helping students to achieve intended learning outcomes and demonstrate their learning progress; providing students with feedback and helping students to act on this feedback; ensuring that all students feel valued and supported, and; providing an assessment that focuses on ‘lifelong participation in physical activity and Sport’ (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 6). Referencing Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007), the statement underscores the importance of feedback. AfL, including feed-up, feedback, and feed-forward, is presented as an essential way to help students comprehend learning outcomes and quality criteria throughout their learning process and should increase assessment transparency.

Finally, the statement suggests that those responsible for education ensure that teachers have assessment literacy and that students are familiar with learning goals (Dinan-Thompson & Penney, Citation2015). Assessment literacy is put forward as an important prerequisite for assessment quality, which allows teachers and students to make valid judgements about the learning process and its outcomes. Assessment literacy is seen to consist of four interdependent elements: assessment comprehension; assessment application; assessment interpretation, and; critical engagement with assessment (Hay & Penney, Citation2013).

In sum, the statement draws on research from a variety of local contexts to suggest that there are three broad problems with assessment that are affecting physical educators internationally: poor instructional alignment, student uncertainty regarding assessment, and assessment practices that lack meaning. The statement suggests that these problems can be addressed by improving PE teachers’ assessment literacy, working closely with students when it comes to assessment, and planning teaching in accordance with a model of instructional alignment. These recommendations sit relatively comfortably with global assessment discourses of accountability and comparability (Exley et al., Citation2011), and indeed, they can be seen as part of the globalized understanding of education (Rizvi, Citation2017). Our interest in this article is the encounter between global PE assessment discourse and local PE traditions. In the next section, we give a description of the Swedish educational context – with reference to the national curriculum – in which Swedish PE has developed.

The Swedish educational context – from German didaktik to Swedish PE didaktik

Although the Swedish educational context has been shaped by a number of philosophical traditions,Footnote1 North European didaktik traditions have been particularly influential (Quennerstedt & Larsson, Citation2015). This influence can be seen in the current Swedish curriculum for compulsory school (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011), and particularly in the general introduction to the curriculum (Sivesind, Citation2013). A detailed examination of this perspective will help us to understand the Swedish educational context and Swedish PE with greater clarity.

‘Didaktik’ refers to a way of understanding the educational process and encompasses general principles as well as subject-specific aspects of teaching and learning (Gundem, Citation2011). While various didaktik traditions exist, most share a concern with (a) understanding education holistically through the concept of Bildung,Footnote2 (b) the embedded differentiation of matter and meaning, and (c) teaching as an autonomous process (Hopmann, Citation2007, pp. 114–115). Swedish education has been influenced by the German school of thinking. Principally, German didaktik places the teacher at the centre of the teaching/studying/learning process (Hudson, Citation2002). It affords teachers the responsibility and opportunity to consider ‘the most basic how, what and why questions around their work’ (Hudson, Citation2002, p. 51). Teachers are expected to carefully consider curricula before attempting to enact them. Westbury (Citation2000) elaborates, proposing that from a German didaktik perspective, ‘the state curriculum does lay out a prescribed content for teaching; but, this content is understood as an authoritative selection from cultural traditions that can only be educative as it is given life by teachers’ (p. 17, our emphasis).

The idea that content is ‘brought to life’ connotes a view of education whereby meanings of content are latent and subjective. Hopmann (Citation2007) notes that within German didaktik, ‘the relation between matter and meaning is always situated in unique moments and interactions [which means that] there is no way to fix the outcome in advance’ (p. 117). A German didaktik position thus sees teaching as ‘a necessarily restrained effort to make certain substantive outcomes possible, while knowing that it can always turn out completely differently from what was intended’ (Hopmann, Citation2007, p. 117). Thus, in German didaktik, assessment is not regarded as central to providing meaningful (physical) education (cf. AIESEP, Citation2020). Bildung in terms of ‘personhood’ is not something that can be measured (at least, not instrumentally), nor is it something that teachers can evaluate from an objective moral position. From a didaktik perspective, decontextualized assessment is thus highly problematic.

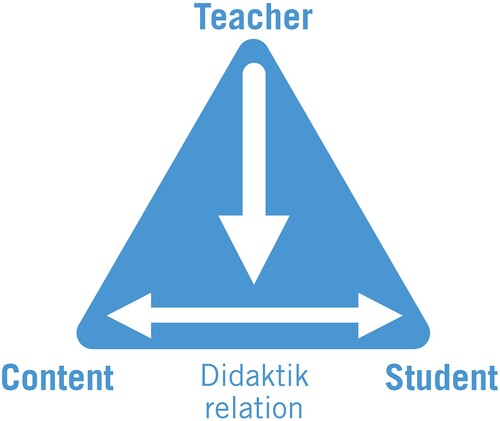

In line with this view of content, preparation for teaching moments is not a technical issue, but rather an interpretive issue. To adequately prepare for a pedagogical encounter, teachers need to develop an understanding of the distinctive requirements of a given situation (Hudson, Citation2002). Teachers develop this type of understanding by interrogating both what students already know about the content and the possible significance of the content for the students. The teacher’s role is to establish a relation to another relation; that between the student and the subject content (see ). The teacher’s evaluation of the learning situation through didaktik reflections could be referred to as a kind of assessment but not the same kind that is advocated in contemporary global educational discourse.

Figure 2. Didaktik relations in the didaktik triangle (Hudson, Citation2002, p. 49).

While German didaktik has had a considerable impact on the current Swedish curriculum, it has not been the only influence. Sundberg and Wahlström (Citation2012) point out that Swedish education underwent significant change in the early 1990s when the Swedish state began to govern the school system through objectives and results. This form of educational governance gained further momentum with educational reform in 2011. It was at this point when knowledge requirements and assessment criteria in five levels (A-E) were introduced.Footnote3 Although the introductory section of the current curriculum strongly reflects didaktik thinking, the individual subject descriptions in the second part of the curriculum reflect an evidence-based assessment discourse with specific learning objectives and knowledge requirements (Sivesind, Citation2013). In this second respect, the curriculum provides a prescription for teaching and assessment and has a keen focus on the results of the educational process.

With regards specifically to Swedish PE, didaktik thinking has had a considerable influence on research and teacher education. Quennerstedt and Larsson (Citation2015) refer to a ‘Swedish Didactics of Physical Education research tradition’ which has focused on ‘the relations between teaching, learning and socialization’ (p. 565). For Quennerstedt and Larsson, ‘PE and PE teaching are never seen to occur in a void but are inscribed in a social context […] Bildung is not only about transforming the person but also about transforming society’ (Quennerstedt & Larsson, Citation2015, p. 569). A number of practice-based studies focus on didaktik problems experienced by PE teachers and students in educational contexts. Redelius et al. (Citation2015) for instance, investigated how students understand lesson goals. Recently, Quennerstedt (Citation2019) highlighted the importance of considering the didaktik questions of why, what, and how when planning PE teaching. The issue of assessment has received some attention in Swedish PE research (Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Redelius & Hay, Citation2012; Svennberg et al., Citation2014). Two investigations have focused on assessment in a local educational context where the culture of performativity meets the didaktik tradition: Tolgfors (Citation2018) used the didaktik triangle to analyse how different relations are established through ‘assessment for learning’ in the teaching practice of PE (see also Tolgfors & Öhman, Citation2016).

In short, the Swedish educational context is influenced by different educational traditions. The general introduction to the current national curriculum significantly reflects a didaktik perspective, especially the notion that teachers are responsible for providing students with a holistic education that addresses students’ individual needs. The subject-specific descriptions in the same curriculum reflect more globalized discourses where desired outcomes of teaching are both generic and clearly prescribed. For its part, Swedish PE research and teacher education has been influenced by didaktik thinking, although little research on assessment has been conducted from a didaktik perspective. We now want to consider how the local and the global – represented by the AIESEP position statement on PE assessment – might work together. It is worth noting that Swedish PE teachers are not obliged to follow the AIESEP position statement. The encounter does not so much take place at the ‘chalk face’ as at higher education institutions where PETE educators like us attempt to make sense of position statements within our local educational contexts.

A case of global assessment policy in a local educational context

In line with our overarching interest in the encounter between global assessment discourse and national educational traditions, we want to consider areas of both synergy and tension. We structure our discussion around six issues: (1) rationales for assessment; (2) underlying views of learning; (3) teachers’ roles in teaching and assessment; (4) positioning of students; (5) understandings of subject content, and; (6) the ways in which contextual conditions are framed. These issues stem from our own local PE didaktik perspective and in this respect, represent the encounter from a local position. We acknowledge that we could have foregrounded the global (AIESEP position) and then examined how the local might fit or not fit with its principles. Our approach is closer to our interpretive experience of reading the position statement. We believe the approach will accord with readers’ encounters of global assessment discourse whereby discourse is understood from a particular position.

Rationales for assessment

According to the position statement, assessment is a process by which ‘information on student learning is obtained, interpreted and communicated, relative to one or more predefined learning outcomes’ (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 3). The statement proposes that assessment should: ‘(1) Guid[e] and support the learning process of students, (2) Inform teachers about the effectiveness of their teaching and curriculum, (3) Decid[e] whether students may progress to the following phase in their learning process or whether a formal qualification (e.g. diploma) can be awarded, (4) Provid[e] evidence of student learning for relevant stakeholders (accountability)’ (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 3). The position statement further recommends teachers select and create Assessment of Learning activities that are aligned with learning outcomes prior to the commencement of the teaching and learning process to ensure ‘assessment transparency’ (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 8). Then, throughout the learning activities, ‘assessment for learning’ has the function of promoting learning, and ‘assessment of learning’ has the function of measuring its outcomes.

The idea that teachers might engage in assessment to collect information on students and their learning is consistent with the tenets of didaktik traditions (Hopmann, Citation2007; Hudson, Citation2002). Moreover, the idea of integrating assessment in the teaching and learning process is not so far removed from the idea of didaktik reflections (Hopmann, Citation2007; Westbury, Citation2000). In these respects, there is a degree of synergy between the local and the global. However, while making didaktik reflections involves a continuous evaluation of the teaching and learning process, the general aim of these reflections is to adapt the teaching to the students’ needs (Hopmann, Citation2007), not to modify the students to meet criteria set out in the standards. The proposition that information be collected relative to one or more predefined learning outcomes is also somewhat problematic. Assessment in Swedish PE, as in other countries, is goal related and criteria referenced (SNAE, Citation2011). At the same time, ‘there is not one single competency necessarily attached to a given matter’ (Hopmann, Citation2007, p. 118). Goals may be reached in various ways, and from a didaktik perspective, assessment practices should be open for negotiation and adaptation to the students’ individual needs and prerequisites (Tolgfors, Citation2018).

Underlying views of learning

The position statement is relatively explicit about the relation between curricular goals, learning outcomes, and assessment of learning. In the statement’s model of instructional alignment (), the learning process is framed linearly, where teachers set learning goals, work towards them, and then evaluate whether learners have successfully met these goals. The model acknowledges an interaction between assessment of learning and assessment for learning, which is integrated in the learning activities. The overall process, nonetheless, remains one-dimensional in that the learning content is expected to remain constant throughout the educational process – the only dependent variable is how well the learners have acquired the content (Pike, Citation2015).

The idea of learning taking place in short sequences defined by clusters of goals, activities, and examinations, is not particularly consistent with the didaktik tradition (cf. Lundgren’s Citation2015 LEGO-metaphor). For one, the didaktik tradition highlights the interactive and changing nature of learning as the teacher, students, and subject content develop together in triadic relation. Equally important from a didaktik perspective is that learning is seen as broader than the mastery of specific content or the achievement of pre-determined goals. Learning refers to the overall development of the individual (Quennerstedt & Larsson, Citation2015). As Hopmann (Citation2007) notes, the very aim of bringing students and content together is holistic development or Bildung – ‘the generalized subject matter of the curriculum is only used to instigate the process’ (Hopmann, Citation2007, p. 118). This view opens up for collaborative working methods in the world of PE and health, when students are introduced to, for example, different movement cultures. It is worth noting that the didaktik tradition endeavours to avoid an atomistic view of learning through the use of, for instance, explorative learning tasks.Footnote4 A didaktik approach is therefore partly in line with the position statement’s recommendation to make students’ assessment experiences meaningful, a point to which we return in our Discussion.

Teachers’ roles in teaching and assessment

The position statement recommends that PE teachers improve their assessment literacy, which includes critical engagement with assessment (AIESEP, Citation2020). PE teachers are positioned as curriculum agents (Westbury, Citation2000), responsible for enacting their national curricula by aligning objectives with teaching and assessment. At the same time, teachers’ knowledge of assessment is framed as insufficient – whatever teachers currently know, it is not enough (see Ball’s Citation2003 discussion of deficit-positioning and the ‘terrors of performativity’, p. 215). We imagine that few teachers want to appear assessment illiterate, and the presence of recommendations may be enough to compel teachers to adopt prescribed practices. Significantly, the position statement (AIESEP, Citation2020) notes that its recommendations should ensure the legitimacy of teachers’ assessment practices.

There is a considerable tension between these recommendations and the didaktik tradition. The tradition positions teachers as reflective practitioners (Westbury, Citation2000). This position involves continuous analysis of one’s pedagogical practices and includes an examination of why one has chosen specific activities, what content is appropriate, and how this content can be made educative (Quennerstedt, Citation2019). Assessment is not prioritized in the didaktik tradition, even if the teacher’s role includes evaluation of how students have understood the subject content. From a didaktik position, teachers are not expected to implement curricula so much as use it as a starting point for developing learning activities together with students. The current Swedish national curriculum nonetheless involves high-stakes assessment, and an accountability culture has influenced Swedish education in recent decades (Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012). An incongruity between imported assessment ideas and the tradition of didaktik has led to tensions for practicing teachers. Some teachers have been criticized for relying too heavily on subjective, opaque assessment criteria (Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Svennberg et al., Citation2014). Others have been compared with ‘administrators of a computerized assessment practice’ (Tolgfors, Citation2018, p. 322).

Positioning of students

The position statement states that:

In order to achieve optimal learning experiences, students should be actively involved in the assessment process, by for example: (i) Determining their learning priorities; (ii) Choosing when and how to demonstrate their learning progression; (iii) Having a part in the construction of assessment tasks and/or criteria; (iv) Self- and peer-assessment; (v) Dialogue with teachers and peers about assessment and its outcomes; (vii) Reflection tasks. (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 8)

From a didaktik perspective, students should be active subjects in the process of ‘becoming’. For eminent didaktik theorist Wolfgang Klafki, education necessarily involved having possibilities for decision making, contributing to social and cultural development, and; expressing solidarity (Hudson, Citation2002). These aspects are synergistic with at least two key strategies of AfL: activating students as resources for one another and activating students as owners of their own learning (Wiliam, Citation2011). This is an instance where globalized assessment policy and the local tradition of didaktik articulate smoothly with one another. Both perspectives are open for different routes toward individual growth. According to the position statement (Citation2020): ‘Evidence of learning in PE should address individual achievement and learning growth and come from multiple, fine-grained and varied sources and take into account student differences’ (p. 6).

Understandings of subject content

In the testing community, ‘generalized competencies are a given, whereas the matter attached may vary depending on situations, contexts, and tests, as long as it necessarily engages the same types of competency’ (Hopmann, Citation2007, p. 119). The idea of declaring intended learning outcomes at the outset of learning sequences is based on the idea of transparency (see for e.g. AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 8). The logic is that the earlier subject content, objectives, and forms of assessment can be communicated to students, the better.

Somewhat counterintuitively, didaktik provides an alternative position on content, a position that gives rise to potential tensions. From a didaktik perspective, what counts as knowledge cannot be given ipso facto but is ‘subject to communicative praxis of validation and justification’ (Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012, p. 353). Questions of why, what, and how can be used for thinking about how a relevant subject content can be selected and justified (Hudson, Citation2002; Quennerstedt, Citation2019). Rather than enacting a ‘model’ with a given content, why/what/how questions require teachers and students to ‘model’ the subject content. Authenticity is embedded in the pedagogical responses to the questions because the questions relate to the students’ lives in terms of previous experiences and future significance. Questions of ‘what’ and ‘why’ are interrelated, whereas the ‘how’ question relates to the issue of making the content educative (see Quennerstedt, Citation2019). The relation between matter and meaning is complex. Since holistic education is an individual outcome, it is not possible to predict or prescribe by means of standardized intended learning outcomes of the type implied by the AIESEP statement.

Contextual considerations

Finally, the position statement is directed at the international PETE community. Scholars are encouraged to translate the document into their own languages and disseminate the recommendations (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 11). On one hand, the position statement could be critiqued for being ‘denationalized and instrumental’ (Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012, p. 342). On the other, the policy statement acknowledges differences in educational conditions and suggests that: ‘Assessment should be embedded in the local (i.e. national, state, province) PE content standards/objectives’. It further states that ‘teachers need a sufficient level of support and autonomy to adapt policies and guidelines to the local context and translate them to the level of students, allowing for equality and inclusiveness’ (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 6).

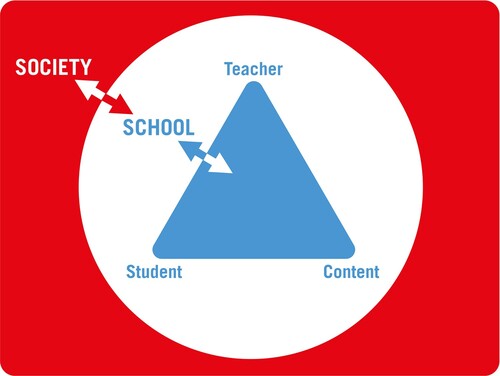

In its acknowledgement of the importance of context, the position statement is close to the didaktik perspective. Didaktik embeds the triadic relation between the teacher, student and subject content within the contextual conditions provided by the school as an institution and by society as a whole (Öhman, Citation2014). Thus, what comes to be regarded as meaningful, relevant, and worthwhile in school PE will relate to students’ sociocultural prerequisites, interests, and ambitions in life. The expanded didaktik triangle can be used to illustrate these contextual considerations ().

Figure 3. The expanded didaktik triangle (Öhman, Citation2014; Quennerstedt, Citation2019).

This approach to educational context is compatible with Hay and Penney’s (Citation2013) suggestion to put authentic assessment in relation to life-long and life-wide learning. If assessment practices are open for students’ worlds outside school, the position statement and didaktik thinking can be seen as synergistic regarding context.

Discussion

As an example of global policy discourse, the AIESEP position statement on PE assessment contains both synergies and tensions with the local Swedish PE didaktik tradition. Using a glocalization perspective, we would like to raise three issues that we believe have a strong bearing on the global assessment discourse – local educational context encounter. Discussion of these issues provides novel insights into how global assessment discourse with PE can be understood. The issues relate to (1) the risk of local PE educational traditions being appropriated by global assessment discourse; (2) the relation between assessment homogeneity and local diversity, and; (3) meaningful PE practices.

The first issue concerns assessment discourse and what it might do to local PE. In considering the encounter between global assessment discourse manifested in the AIESEP position statement on the assessment and Swedish PE traditions from a glocal standpoint, we have identified areas of both synergy and tension. The encounter is synergistic in the positioning of students, for example, and the way in which school and social contexts are considered important in the overall process of education. There are ample examples of tension that relate to underlying views of learning and teachers’ roles in teaching and assessment. For instance, a short-term, tightly-defined understanding of learning as meeting objectives is inconsistent with a long-term, wide understanding of learning as personal growth. It is along these latter lines that debate and uncertainty might arise. For instance, physical educators might well question their freedom to design assessment activities and whether meeting local assessment needs might compromise equivalent testing across schools (cf. Tolgfors & Öhman, Citation2016). In practice, the ideas contained in the position statement are likely to both disrupt/challenge and support/help PETE educators and PE teachers. None of this suggests that Swedish PE and PE assessment practices are entirely inconsistent with global assessment discourse (Weber, Citation2007) or that assessment in Swedish PE is about to be arrogated by an oversimplified culture of performativity (Ball, Citation2003; Lingard, Citation2021a) and test-driven accountability (Ball et al., Citation2012; El Bouhali, Citation2015; Gray et al., Citation2018; Rizvi, Citation2017; Torrance, Citation2011; Citation2017). It is worth remembering nonetheless that the AIESEP position statement is of a different order (and a smaller scale) to projects run by organizations such as the OECD discussed at the outset of the paper. The AIESEP position statement is aimed at members of the PE higher education community, not directly at politicians, policy makers or frequently, the general public via the media (Engel & Rutkowski, Citation2020). Further, unlike DeSeCo, whose major impetus has come from the business sector and from employers (OECD, Citation2021), the AIESEP position statement has been formulated by education experts within the field. The intended audience perhaps helps explain why the position statement and local PE tradition contain synergies and why signs of homogenization might be less evident in our analysis.Footnote5

As in many other countries (Lipman, Citation2004; Spring, Citation2008), Swedish schools and school populations are becoming progressively heterogenous (Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012). Independent schools have become commonplace and due to global events such as the last decade’s refugee crises, current student cohorts have wider experiences of sports and school PE compared to earlier cohorts (see for example, Barker, Citation2019). Several scholars have suggested that assessment discourse has particularly adverse effects in educational settings characterized by diversity. Hopmann (Citation2007), for example, draws attention to children with special needs and students with minority backgrounds, suggesting that ‘within the realms of modern comparative assessment they can only count as liabilities or are simply excluded as non-fitting entities’ (p. 119). We would propose that in educational contexts characterized by diversity, PE teachers face a dilemma: If they adapt teaching and assessment to the students’ different needs, there will be problems in terms of comparability and equal grading. If they do not adapt, assessment practices will help to cement social injustice.

The AIESEP position statement reflects this dilemma. On one hand, it advocates a ‘set of orderly steps’ (Westbury, Citation2000, p. 19) which can be enacted by all PE teachers through planning based on instructional alignment and the use of feed-up, feedback and feedforward (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007) or the five universal strategies of AfL (Wiliam, Citation2011). On the other hand, it is explicit in its expectation that teachers will acknowledge local differences and transform assessment practices to meet the needs of learners. The encounter is therefore not straightforward. Robertson’s (Citation1995) commentary on glocalization provides a useful take on the student diversity-assessment standardization relationship. He claims that it is precisely under conditions of increasing heterogeneity that processes of homogenization gather momentum. From a glocal perspective, the emergence of homogenizing projects like the AIESEP position statement on assessment is unsurprising because homogenization and heterogenization tendencies tend to be mutually implicative (see also Weber, Citation2007). Shifts towards greater cultural diversity and greater assessment uniformity are comparable in that both represent an evolution of the educational context. In this respect, both developments can provoke conservative critique and a nostalgic narrative that education was once simpler and more ‘ontologically secure’ (Robertson, Citation1995, p. 30). Importantly though, global assessment discourse anticipates a future state based on standardization and comparison. In this sense, it can be understood as a ‘reactionary reflex’ (Are Trippestad, Citation2015, p. 12) to diverse and multicultural future states shaped by migration and diaspora. Both homogenization and heterogenization are nonetheless involved in the ongoing reconstruction of educational localities.

A third and related issue concerns whether assessment practices are meaningful to learners. The AIESEP statement proposes that assessment is ‘central to providing meaningful, relevant and worthwhile physical education’ (AIESEP, Citation2020, p. 2). That assessment is necessary for providing meaningful education is contentious and as noted at the outset of the paper, several scholars have claimed that global assessment discourses are unconnected or irrelevant to learners’ lives (Lipman, Citation2004; Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012). From a didaktik perspective, assessment is certainly not essential for meaningful education (Hopmann, Citation2007).

We should, however, consider for a moment what meaningful education entails. Drawing on Miller’s (Citation1993) work, Are Trippestad (Citation2015) suggests that we are living in cultural-capitalistic conditions. These conditions are dominated by two major discourses: a capitalistic-economic discourse that has ‘change, development, profit and wealth as its themes’ (p. 18), and a political discourse that tries to ‘produce citizens who are moral, with feelings of community and societal spirit, both in the public sphere and in private life’ (p. 18). Working from Are Trippestad’s (Citation2015) thesis, an education connected to the lives of learners would reflect both a capitalistic-economic discourse and a political discourse. Both discourses are evident in Swedish PE. A globalizing assessment discourse, with tenets of accountability, comparability, and competition (Exley et al., Citation2011) is reflected in the curriculum’s knowledge requirements and assessment criteria. Increased research interest in local PE assessment issues has followed in the wake of this global tendency (Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010; Svennberg et al., Citation2014). These features correspond roughly with a capitalistic-economic discourse (Gray et al., Citation2018; Rizvi, Citation2017), which aims to produce utilitarian individuals who are willing to adapt to an ever-changing environment. A didaktik perspective with its focus on holistic development (Hudson, Citation2002; Quennerstedt & Larsson, Citation2015) and why, what and how questions (Quennerstedt, Citation2019), corresponds roughly to a political discourse. It represents an attempt to provide learners with a personal and political education. In this vein, Quennerstedt and Larsson (Citation2015) claim that Bildung in PE is not only about transforming the person but also about transforming society. Accordingly, assessment for learning can be used as a way of promoting students’ individual training and health projects that are mainly carried out outside school (Tolgfors, Citation2018; Tolgfors & Öhman, Citation2016). In this sense, the endeavour to provide students with meaningful PE experiences needs to have two foci. If schooling offered only an induction into a capitalistic-economic discourse or only a civic education, students would be unprepared for life in modern societies.

Conclusion

In this article, we have critically considered the encounter between global PE assessment discourse and local educational traditions. Taking the AIESEP Position Statement on Physical Education Assessment (Citation2020) as an example of global discourse and Swedish PE didaktik as an example of a local tradition, we described areas of synergy and tension between the global and the local. Then using the concept of glocalization (Robertson, Citation1995), we considered three issues that have a significant bearing on the encounter. These issues concerned risk of appropriation, the relation between global homogeneity and local heterogeneity, and meaningful practices within PE.

We want to finish with four brief reflections. First, some of the problems that global assessment discourse attempts to resolve (poor instructional alignment, student uncertainty regarding assessment, and assessment practices that lack meaning) and some of the solutions the discourse provides (improving PE teachers’ assessment literacy, working closely with students when it comes to assessment, and planning teaching in accordance with a model of instructional alignment) are derived from local contexts. For instance, the statement is partly based on the identification of problems with assessment validity, comparability and fairness in Swedish PE (Annerstedt & Larsson, Citation2010). The assessment discourse represented in the position statement is thus already imbued with aspects of the local when the encounter takes place. Second and related, we have shown that the position statement is multifaceted, containing different, and at times conflicting, ideas. Assessment should for example, be comparable or standardized but at the same time, student-centered. To our minds, a degree of inconsistency is a productive element of a discourse and without inconsistency, the discourse risks losing its persuasiveness. For example, both comparability (the same for all students) and student-centeredness (unique to all students) can be presented as valuable characteristics of assessment in a text, and to omit one might invite critique. In practice, however, the attainment of one presents significant challenges to the attainment of the other. Third, we recognize that have devoted much of this paper to theoretical issues – practical implications have gone largely undiscussed. Our hope nonetheless is that the paper has raised pedagogical issues that educators will be inspired to reflect on. Questions relating, for example, to instructional alignment, authentic assessment, breadth of learning outcomes, and the clustering of learning and grading activities can all be raised and scrutinized from different perspectives. In this sense, we hope that the paper will be seen as generative rather than conclusive. Finally, although we have focused on the Swedish educational context, our contention is that all educational contexts exist in conditions of glocality. Further examinations of how global assessment is encountered in other local contexts will provide useful insights into how physical education as a field is evolving. Such insights will help physical educators prepare for – and shape – PE in the future.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank our colleagues in the ReShape research group at Örebro University – Joacim Andersson, Natalie Barker-Ruchti, Annica Caldeborg, Helena Ericson, Susanna Geidne, Emil Johansson, Mikael Quennerstedt, Marie Öhman – for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 These include phenomenography (Marton, Citation1981), curriculum theory (Lundgren, Citation1972), socio-political perspectives (Englund, Citation2007; Forsberg, Citation2014; Wahlström, Citation2016), as well as socioculturalist (Vygotsky, Citation1986/Citation2012), constructivist (Piaget, Citation1980), and pragmatist perspectives (Dewey, Citation1938/Citation1997).

2 Bildung as an education of the whole person involves three aspects: Self-determination (independent, responsible decisions and interpretations); co-determination (the right and responsibility to contribute to socio-cultural development together with others), and; solidarity (actions to help others) (Hudson, Citation2002).

3 The shift to prescribed educational objectives in Swedish education has not gone without criticism. Forsberg (Citation2014) suggested that this tendency threatens teachers’ autonomy, claiming that if assessment criteria are prioritized, education risks being trivialized, fragmented, and emptied of meaning (see also Carlgren, Citation2016). Lundgren (Citation2015) disparagingly compares the educational approach signaled by the Swedish curriculum’s focus on outcomes to modern LEGO kits which he claims now consist of ‘a box with an instruction manual for building a pre-designed product’ (p. 11).

4 Explorative tasks are similar to ‘rich tasks’ (MacPhail & Halbert, Citation2010), which embrace several learning outcomes simultaneously. According to MacPhail and Halbert (Citation2010), a task is rich when ‘it is authentic for the student and relevant to the learning outcomes in question. It should also contain transparent criteria and standards, encompass more than one learning outcome, involve acquiring, applying and evaluating knowledge, skills and understanding’ (p. 25).

5 To date, physical and health-related competencies that are gained through PE have not caught the attention of organizations such as the OECD, whose focus remains firmly fixed on mathematics, science and literacy (Spord-Borgen & Hjardemaal, Citation2017). This is not to rule out possible attention in the future.

References

- AIESEP. (2020). The AIESEP position statement on physical education assessment. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from https://aiesep.org/scientific-meetings/position-statements/

- Annerstedt, C., & Larsson, S. (2010). ‘I have my own picture of what the demands are … ’: Grading in Swedish PEH – problems of validity, comparability and fairness. European Physical Education Review, 16(2), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X10381299

- Are Trippestad, T. (2015). The glocal teacher: The paradox agency of teaching in a glocalized world. Policy Futures in Education, 14(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210315612643

- Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., Perryman, J., & Hoskins, K. (2012). Assessment technologies in schools: ‘deliverology’ and the ‘play of dominations’. Research Papers in Education, 27(5), 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2010.550012

- Barker, D. (2019). In defence of white privilege: Physical education teachers’ understandings of their work in culturally diverse schools. Sport, Education and Society, 24(2), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1344123

- Borghouts, L. B., Slingerland, M., & Haerens, L. (2017). Assessment quality and practices in secondary PE in the Netherlands. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(5), 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2016.1241226

- Brooks, J. S., & Normore, A. H. (2010). Educational leadership and globalization: Literacy for a glocal perspective. Educational Policy, 24(1), 52–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904809354070

- Carlgren, I. (2016). Skuggan. Undervisning och läroplanens janusansikte [The shadow. Teaching and the Janus face of the curriculum.] Skola och Samhälle. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from www.skolaochsamhälle.se.

- Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. Touchstone. (Original work published 1938)

- Dinan-Thompson, M., & Penney, D. (2015). Assessment literacy in primary physical education. European Physical Education Review, 21(4), 485–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15584087

- Dyson, B. (2014). Quality physical education: A commentary on effective physical education teaching. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(2), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.904155

- El Bouhali, C. (2015). The OECD neoliberal governance: Policies of international testing and their impact on global education systems. In A. Abdi, L. Schultz, & T. Pillay (Eds.), Decolonizing global citizenship education (pp. 119–129). Brill Sense.

- Engel, L. C., & Rutkowski, D. (2020). Pay to play: What does PISA participation cost in the US? Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(3), 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1503591

- Englund, T. (2007). Om relevansen av begreppet didaktik [On the relevance of didactics.]. Acta Didactica Norge, 1(1), 02–10. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.1013

- Exley, S., Braun, A., & Ball, S. (2011). Global education policy: Networks and flows. Critical Studies in Education, 52(3), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2011.604079

- Forsberg, E. (2014). Utbildningens bedömningskulturer i granskningens tidevarv [Education assessment cultures in the audit era.]. Utbildning & Demokrati–Tidskrift för Didaktik och Utbildningspolitik, 23(3), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.48059/uod.v23i3.1024

- Gray, J., O’Regan, J. P., & Wallace, C. (2018). Education and the discourse of global neoliberalism. Language and Intercultural Communication, 18(5), 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2018.1501842

- Gundem, B. B. (2011). Europeisk didaktikk. Tenkning og viten [European didactics. Thinking and knowing.] Universitetsforlaget.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Hay, P. J., & Penney, D. (2013). Assessment in physical education. A sociocultural perspective. Routledge.

- Hopmann, S. (2007). Restrained teaching: The common core of didaktik. European Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.109

- Hudson, B. (2002). Holding complexity and searching for meaning: Teaching as reflective practice. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 34(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270110086975

- Hursh, D. (2007). Assessing no child left behind and the rise of neoliberal education policies. American Educational Research Journal, 44(3), 493–518. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207306764

- Lewis, S., Sellar, S., & Lingard, B. (2016). PISA for schools: Topological rationality and new spaces of the OECD’s global educational governance. Comparative Education Review, 60(1), 27–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/684458

- Lingard, B. (2021a). The changing and complex entanglements of research and policy making in education: Issues for environmental and sustainability education. Environmental Education Research, 27(4), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1752625

- Lingard, B. (2021b). Multiple temporalities in critical policy sociology in education. Critical Studies in Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2021.1895856

- Lipman, P. (2004). High stakes education: Inequality, globalization, and urban school reform. Routledge Falmer.

- López-Pastor, V. M., Kirk, D., Lorente-Catalán, E., MacPhail, A., & Macdonald, D. (2013). Alternative assessment in physical education: A review of international literature. Sport, Education and Society, 18(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.713860

- Lorente-Catalán, E., & Kirk, D. (2016). Student teachers’ understanding and application of assessment for learning during a physical education teacher education course. European Physical Education Review, 22(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15590352

- Lundgren, U. P. (1972). Frame factors and the teaching process. A contribution to curriculum theory and theory on teaching. Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Lundgren, U. P. (2015). When curriculum theory came to Sweden. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(1), 27000. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.27000

- Macdonald, D. (2011). Like a fish in water: Physical education policy and practice in the era of neoliberal globalization. Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich ), 63(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2011.10483661

- MacPhail, A., & Halbert, J. (2010). ‘We had to do intelligent thinking during recent PE’: Students’ and teachers’ experiences of assessment for learning in post-primary physical education. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(1), 23-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940903565412

- Marton, F. (1981). Phenomenography – describing conceptions of the world around us. Instructional Science, 10(2), 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00132516

- Miller, T. (1993). The well-tempered self: Citizenship, culture and the postmodern subject. John Hopkins University Press.

- OECD. (2021). Skills beyond school. Retrieved June 28, 2021, from https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/ definitionandselectionofcompetenciesdeseco.htm

- Öhman, J. (2014). Om didaktikens möjligheter – ett pragmatiskt perspektiv [The possibilities of didactics – a pragmatist perspective.]. Utbildning & Demokrati, 23(3), 33–52.

- Penney, D., Brooker, R., Hay, P. J., & Gillespie, L. (2009). Curriculum, pedagogy and assessment: Three message systems of schooling and dimensions of quality physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 14(4), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320903217125

- Piaget, J. (1980). The psychogenesis of knowledge and its epistemological significance. In M. Piatelli-Palmarini (Ed.), Language and learning (pp. 23–34). Harvard University Press.

- Pike, G. (2015). Re-imagining global education in the neoliberal age: Challenges and opportunities. In R. Reinolds, J. Bradbery, J. Brown, K. Carroll, D. Donnelly, K. Ferguson-Patrick, & S. Macqueen (Eds.), Contesting and constructing international perspectives in global education (pp. 9–25). Brill Sense.

- Quennerstedt, M. (2019). Physical education and the art of teaching: Transformative learning and teaching in physical education and sports pedagogy. Sport, Education and Society, 24(6), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1574731

- Quennerstedt, M., & Larsson, H. (2015). Learning movement cultures in physical education practice. Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.994490

- Redelius, K., & Hay, P. J. (2012). Student views on criterion-referenced assessment and grading in Swedish physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 17(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2010.548064

- Redelius, K., Quennerstedt, M., & Öhman, M. (2015). Communicating aims and learning goals in physical education: Part of a subject for learning? Sport, Education and Society, 20(5), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.987745

- Rink, J., & Mitchell, M. (2002). High stakes assessment: A journey into unknown territory. Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich ), 54(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2002.10491775

- Rizvi, F. (2017). Globalization and the neoliberal imaginary of educational reform. Education research and foresight: Working papers.

- Robertson, R. (1995). Time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity. In M. Featherstone, S. Lash, & R. Robertson (Eds.), Global modernities (pp. 25–44). Sage.

- Rutkowski, D. (2015). The OECD and the local: PISA-based test for schools in the USA. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(5), 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2014.943157

- Rutkowski, D., Thompson, G., and Rutkowski, L. (2020). Understanding the policy influence of international large-scale assessments in education. In H. Wagemaker (Ed.), Reliability and validity of international large-scale assessment (pp. 261–279). IEA Research for Education, Springer E-book. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53081-5

- Sivesind, K. (2013). Mixed images and merging semantics in European curricula. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2012.757807

- Spord-Borgen, J., & Hjardemaal, F. R. (2017). From general transfer to deep learning as argument for practical aesthetic school subjects? Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1352439

- Spring, J. (2008). Research on globalization and education. Review of Educational Research, 78(2), 330–363. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308317846

- Stromquist, N. P., & Monkman, K. (2014). Globalization and education: Integration and contestation across cultures. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Sundberg, D., & Wahlström, N. (2012). Standards-based curricula in a denationalised conception of education: The case of Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 11(3), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2012.11.3.342

- Svennberg, L., Meckbach, J., & Redelius, K. (2014). Exploring PE teachers’‘gut feelings’. An attempt to verbalize and discuss teachers’ internalised grading criteria. European Physical Education Review, 20(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X13517437

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011). The national curriculum for compulsory school. Norstedts.

- Thorburn, M. (2007). Achieving conceptual and curriculum coherence in high-stakes school examinations in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 12(2), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980701282076

- Tolgfors, B. (2018). Different versions of assessment for learning in the subject of physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1429589

- Tolgfors, B., & Öhman, M. (2016). The implications of assessment for learning in physical education and health. European Physical Education Review, 22(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15595006

- Torrance, H. (2011). Using assessment to drive the reform of schooling: Time to stop pursuing the chimera? British Journal of Educational Studies, 59(4), 459–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.620944

- Torrance, H. (2012). Formative assessment at the crossroads: Conformative, deformative and transformative assessment. Oxford Review of Education, 38(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.689693

- Torrance, H. (2017). Blaming the victim: Assessment, examinations, and the responsibilisation of students and teachers in neo-liberal governance. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 38(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1104854

- Vygotsky, L. S. (2012). Thought and language. MIT Press. (Original work published 1986)

- Wahlström, N. (2016). A third wave of European education policy: Transnational and national conceptions of knowledge in Swedish curricula. European Educational Research Journal, 15(3), 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116643329

- Weber, E. (2007). Globalization, “glocal” development, and teachers’ work: A research agenda. Review of Educational Research, 77(3), 279–309. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430303946

- Westbury, I. (2000). Teaching as a reflective practice: What might didaktik teach curriculum? In I. Westbury, S. Hopman, & K. Riquarts (Eds.), Teaching as a reflective practice. The German didaktik tradition (pp. 15–39). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Wiliam, D. (2011). What is assessment for learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.001