ABSTRACT

In recent years there has been an increasing interest in the concepts of bullying and banter within both sport research and media reporting. However, at present, research has not explored reports of bullying and banter within the UK sport media This is a potential omission, as the media may provide important conceptual information about bullying and banter to those outside of the academic domain. Therefore, the present study sought to understand how banter and bullying are framed by the UK sport media and how these concepts have been distinguished from one another. Guided by a pragmatist approach, 85 print and broadcast media articles were analysed from The Times, The Telegraph, Daily Mail, The Sun, The Guardian, British Broadcasting Company (BBC) and Sky Sports News (SNN). Through an abductive thematic analysis, the findings highlighted several themes around the media’s view of bullying. The media differentiated bullying and banter through the tipping point between these concepts and a misinterpretation of jokes and banter. The present study contributed to the current research on bullying and banter by analysing the media’s perspectives of the concepts. Overall, the findings outline the contemporary understanding of bullying in sport, whilst highlighting the significant influence the media has in shaping the discussion around banter in this context.

Introduction

Within recent research and media reporting in the United Kingdom (UK), there has been a growing interest in the similarities and divide between bullying behaviours and what might be viewed as banter in elite sport. For example, in English football, a multitude of players have made allegations of bullying and harassment (BBC, Citation2019, Citation2021c), whilst in cricket derogatory behaviour such as ‘racial harassment and bullying’ has been identified as ‘friendly, good-natured banter’ (e.g. BBC, Citation2021b). Furthermore in British gymnastics cases of physical and emotional abuse cases have been reported (Falkingham, Citation2022). These reports describe how the normalisation of abuse discussed within research in sport (Kelly & Waddington, Citation2006) remains prevalent today.

To date, research has explored elite athletes’ experiences of abuse (e.g. Kavanagh et al., Citation2017) and, more specifically, the dividing line between bullying and banter (Booth et al., Citation2023; Newman et al., Citation2022; Newman, Eccles, et al., Citation2022). Although this research provides a valuable contribution to the understanding of potential wrongdoing (as well as the positive humorous aspects of banter) in elite and community sport, it is uncertain as to how much these findings may have been received by those outside of the academic community. Therefore it is of interest to explore the media’s reporting of bullying and banter, given the power this outlet has to shape thoughts, feelings and behaviour around a specific set of phenomena (Alexander et al., Citation2022).

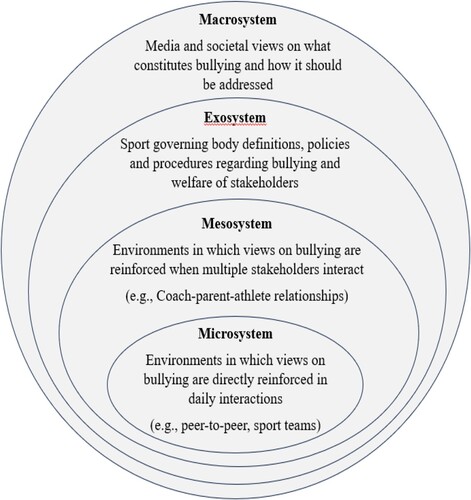

The media's influence as a macrosystem

The media plays a substantial role in the public’s understanding of sport due to their wide range of audiences where they can influence an individual's perceptions of behaviour, through guiding and limiting views of a topic (Lewis & Weaver, Citation2013). Unfortunately, even though the way athletes are portrayed in the media is of considerable importance, these accounts have been found to not always provide neutral and factual information and can be biased towards one perspective (Lewis & Weaver, Citation2013). For example, Lewis and Weaver (Citation2013) how journalists can influence their audience’s support of an athlete which can boost the consumptions of their media’s content. From an ecological systems theory perspective (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999), this could be problematic for consumers of the media given the media occupy one of the major institutions in society as part of a wider macrosystem (Eriksson et al., Citation2018). According to this theory, although the media may not directly impact the settings surrounding a developing person, they may influence individual perceptions of behaviour (e.g. bullying and banter in sport) by reinforcing the settings within which people are found (see , Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999). Research corroborates these theoretical propositions as the sport media remains a key influence on the behaviours of its consumers through indicators such as motivation, competitiveness, self-improvement and violence (Pilar et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it appears critical to understand how the media frames behaviours connected to wrongdoing in sport, and, understand how elements in the news are displayed and impact the audience's perceptions (Lewis & Weaver, Citation2013).

Figure 1. Nested model of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory with high-performance sport environments as an example.

Currently, to our knowledge, empirical studies analysing the media perspectives of bullying and banter remain limited in sport. The lack of studies is a pertinent omission as the potential influence and repercussions of the media’s messages around these concepts are not understood by researchers (Alexander et al., Citation2022). Moreover, it is important to further explore the reporting within media’s messages around bullying and banter. For example, research findings evidence a lack of representativeness within the media, as well as institutional racism, and the potential for bullying and harassment to not be appropriately framed in sport (Boyle, Citation2013; Velija & Silvani, Citation2020). These issues may also contribute to the discourse around wrongdoing and the public’s perceptions of these behaviours. Given the media have also been accused of normalising unacceptable behaviour as part of the high-pressure nature of sport, it appears to further necessitate greater understanding of their perspective (Velija & Silvani, Citation2020). By contrast, further exploration of the media’s reporting of bullying and banter may provide a useful extension to those reporters who have sought to understand the blurred line between these concepts in elite sport (Ingle, Citation2021). Furthermore, by exploring the media’s perspective it also provides the opportunity to explore whether the potential prosocial (as well as negative) aspects of banter alluded to in the research literature (Dynel, Citation2008; Steer et al., Citation2020), are also prevalent within journalists’ reports.

Conceptualising banter and bullying

At present research contains various definitions which are indicative of the conceptual similarities and differences between banter and bullying. These definitions offer some understanding of these concepts within the micro (e.g. the close relationships and interactions an individual has) and the mesosystems (e.g. the relationships between influential figures close to the individual) of sport (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999). Instead of a specific contextual definition, research in sport tends to favour Olweus’ (Citation1993, p. 8) definition of bullying which describes this behaviour as ‘an intentional, negative action which inflicts injury and discomfort on another’ (Olweus, Citation1993, p. 8). Typically, this involves a power disparity whereby the victim cannot defend themselves (Olweus, Citation1993). While more recent definitions of bullying (e.g. Volk et al., Citation2014) contest aspects such as intentionality and repetition highlighted by Olweus, they do reaffirm that this is a goal-directed behaviour which occurs in the presence of a power imbalance between the bully and victim.

Banter as a concept is much less defined, though it can be seen as a playful interaction between individuals which can improve their relationship, but where this interaction can involve innocuous aggression (Dynel, Citation2008). Thus, banter can be an ambiguous concept as it exhibits elements of the violent, repetitive nature which underpins bullying yet it can be seen to be humorous among friends (Steer et al., Citation2020). Although these definitions delineate these concepts, research findings and media reports demonstrate how terms such as banter and bullying can be conflated. For example, although Olweus’ (Citation1993) definition of bullying has retained support in recent sport research (Jewett et al., Citation2019), others have found that this behaviour is conducted for ‘entertainment purposes’ and does not necessarily carry the intent to harm (Booth et al., Citation2023; Kerr et al., Citation2016). Similarly, media reports have identified how banter links to harassment and abuse in elite sport (BBC, Citation2021b). Therefore, findings across research and media illustrate there is conceptual ambiguity in relation to bullying and banter. For banter specifically, this reaffirms that this concept can be regarded as exclusionary (where jokes transgress acceptability and can be abusive) and inclusionary (where close relationships can facilitate more prosocial behaviour) in sport (Lawless & Magrath, Citation2021).

In an attempt to understand banter and bullying further, sport research favours Stirling’s (Citation2009) conceptual model of maltreatment which focuses on the relational nature of these concepts. This model suggests two broad categories of maltreatment (relational and non-relational) that occur in sport with various forms of maltreatment being categorised depending on the nature of the relationship in which the actions happened. According to Stirling (Citation2009), bullying is characterised as non-relational maltreatment as the behaviour occurs in a ‘non-critical’ relationship whereby the perpetrator has no official authority over the victim. In contrast, relational maltreatment focuses on characteristics which occur within a ‘critical’ relationship. This form of maltreatment focuses on different forms of abuse and neglect which occur when an individual has authority (e.g. parents, sport coaches) over athletes (Stirling, Citation2009).

Although Stirling’s (Citation2009) model provides an important framework for understanding various forms of maltreatment within the microsystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999), findings both within (Newman, Warburton, et al., Citation2021) and outside (Hershcovis, Citation2011) of sport have demonstrated issues with its application. For example, professional footballers conceptualised bullying as occurring within a ‘critical’ relationship where individuals in positions of authority (e.g. coaches) were the perpetrators of this behaviour (Newman, Warburton, et al., Citation2021). A further limitation of Stirling’s (Citation2009) model is the lack of reference to terms such as banter, which is problematic given its centrality to the culture of certain sports (Parker, Citation2006). This is problematic as in its ‘bad’ form, banter displays some of the characteristics which underpin bullying (Steer et al., Citation2020). Moreover, Stirling’s (Citation2009) model does not capture the ambiguous elements of concepts such as banter where this behaviour may be deemed as prosocial. Finally, while Stirling’s (Citation2009) conceptual model makes a significant contribution to the understanding of terms such as bullying in sport research, its contribution to the wider societal discourse around these behaviours at the macro-level may be more limited. This is reflected insofar that media articles often do not include a substantial discussion of research findings about various topics (Jonker et al., Citation2022). In this case, this may include a lack of discussion of research findings connected to maltreatment in sport. The lack of representation from the media may be a particular omission in research literature given their broad readership, and potential influence on understanding (Alexander et al., Citation2022) of concepts such as bullying and banter.

Present study

As the sports media appear to normalise abusive and bullying behaviour in a similar way to other sporting populations in elite sport (Newman, Eccles, et al., Citation2022; Salim & Winter, Citation2022), an exploration into how the media report wrongdoing, as well as how they differentiate the potentially prosocial elements of banter, was merited. Furthermore, given media reports of abuse and bullying appear to mirror findings with sporting populations around the interrelated nature and blurred lines of these behaviours with banter (Booth et al., Citation2023; Newman et al., Citation2022; Newman, Eccles, et al., Citation2022), it was worthwhile for the present study sought to explore the views presented by this population further. This was particularly pertinent given the prominence and influence of the media as part of the macrosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999) of sport.

Therefore, due to the issues identified in both sport research and media in terms of understanding of the concepts of bullying and banter the present study explored how the sport media reported stories related to these terms in elite sport. The present study aimed to understand how banter and bullying are framed and how these concepts are distinguished from each other by the UK sport media. Through exploring the media as a unique sporting population, the present study extended upon previous research in this area by focusing on an institution who represent a macrosystem in the wider landscape of organised sport. In doing this an alternative voice was represented who may contribute to the wider safeguarding and welfare of those in sport.

Methods

Research design

The present study was guided by a pragmatist approach, which rejects the top-down privileging of ontological assumptions in the metaphysical paradigm as too narrow and positions methodology at the centre to connect epistemology and actual methods (Morgan, Citation2007). A pragmatist approach positioned the study’s purpose centrally, emphasising communication, shared meaning-making and transferability to reflect on the purpose of the study’s outcomes (Morgan, Citation2007; Shannon-Baker, Citation2016). Furthermore, through a pragmatist approach, a qualitative study design was adopted. In line with the pragmatist approach, the practical need to explore understanding of how bullying and banter are framed by the sports media dictated the choice of qualitative methods rather than mixing methods (Gibson, Citation2019). This approach enabled a more significant in-depth analysis and observation (Gibson, Citation2019) of the media perceptions of bullying and banter within elite sport.

In terms of the selection of media sources, while we recognise that a variety of media sources can affect attitudes, beliefs and preconceptions (Alexander et al., Citation2022), the present study was guided by the prominence of online and print media in influencing public opinion on a topic (Cheong et al., Citation2016). Moreover, given these sources contain sport sections that provide journalists with the space to convey in-depth and opinionated pieces which may influence their audience’s attitudes and beliefs (Alexander et al., Citation2022) articles from online and print media were solely focused on for this study. Therefore, media articles within the present study had to meet specific criteria guided by Velija and Silvani’s (Citation2020) study around print narratives of bullying. Firstly, to maintain consistency in terms of English language, articles were selected from established print and broadcast media organisations from the UK. Secondly, media articles were selected from when the key concepts for the study started to gain prominence in UK sports media, reporting in March 2014 up until February 2023. We excluded radio broadcast (e.g. TalkSport) and sports magazine sources since they have limited viewership and readership compared to the print media (Velija & Silvani, Citation2020).

To access a range of print media articles and journalistic styles a maximum variation sampling was employed. Maximum variation sampling enables the capture of a wide range of perspectives (Langdridge, Citation2007). Therefore, collecting data from various print and broadcast media articles enabled an exploration of the different perspectives of these concepts, with the following sources selected: The Times, The Telegraph, The Sun, The Guardian and The Daily Mail. In addition, the publicly owned and funded British Broadcasting Company (BBC) and Sky Sports News (SSN), who are an editorially independent part of Sky UK owned by Comcast NBCUniversal (Sky News, Citation2023), were utilised for broadcast media representation. For context, in the United Kingdom, The Sun (owned and funded by News Corporation) is known as Eurosceptic, a right-leaning newspaper with an estimated circulation of 1,210,915 and readership of 6,174,000 per month (Ponsford, Citation2023; Tobitt & Majid, Citation2023). The Daily Mail, privately owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust chaired by Lord Rothermere (Kleinman, Citation2023), is also a right-leaning organisation with a circulation of 633,086 and readership of 6,169,000 per month (Ponsford, Citation2023; Tobitt & Majid, Citation2023). The Times (also owned and funded by News Corporation) is a broadsheet newspaper with an overall smaller circulation of 365,880 and readership of 843,766 (Hurst Media, Citation2020c; Tobitt & Majid, Citation2023) and is acknowledged as a right-wing conservative paper (Cushion et al., Citation2018). The Telegraph, owned by Sir Frederick Barclay (Pellegrino, Citation2023) is also a right-wing broadsheet newspaper with a circulation of 470,000 and readership of 734,000 (Cushion et al., Citation2018; Hurst Media, Citation2020b). The Guardian, by contrast, was selected as it is a left-leaning newspaper, owned by the not-for-profit Scott Trust, with a circulation of 105,134 and readership of 516,624 (Hurst Media, Citation2020a; Tobitt & Majid, Citation2023). SSN was selected as a subscription service which provides 24-hour coverage of the UK sports industry. The BBC was selected as it is the UK's primary news provider and is considered to offer a neutral stance (Cushion et al., Citation2018).

Data collection

Following ethical approval (ER51028506), the study followed purposeful sampling guidelines (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014) to understand the media's perspective of bullying and banter within elite sport. A purposive sampling approach offered the potential to find information-rich articles (Patton, Citation2002) and was combined with a maximum variation approach (see Rumbold et al., Citation2023) to explore if there were commonalities and differences within the media’s reporting of bullying and banter within elite sport. The present study analysed 85 print and broadcast media articles which were identified using the search terms ‘Abuse in sport’, ‘Banter in sport’ and ‘Bullying in sport’. Given the broader categorisation of behaviours such as bullying into forms of maltreatment (Stirling, Citation2009) a further search of ‘Maltreatment in sport’ was also conducted. These articles were placed into four files, one for each news article. Print and broadcast media articles were found online using ‘Google Advanced’ and ‘LexisNexis’ search engines (Velija & Silvani, Citation2020).

Data analysis

Consistent with pragmatism, we used an abductive thematic analysis approach (Thompson, Citation2022) to identify the media’s reporting of bullying and banter in elite sports. An abductive approach to thematic analysis facilitates an empirical discovery whilst being guided by theoretical understanding (Thompson, Citation2022). In the present study, Thompson’s (Citation2022) 8 steps of abductive analysis were followed. Initially, the authors familiarised themselves with the media reports and read these accounts accurately to search for meaning and the underlying narratives within the accounts (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Then a cyclical act of coding took place, which involved extracting as much semantic from the data corpus as possible during the first round of coding, before consolidating codes at a deeper level in subsequent rounds (Thompson, Citation2022). As a result a codebook was generated, where a label was provided for each code that was short, concise and as relevant to original data as possible with an accompanying quotation. This process also allowed the research team the opportunity to prompt an internal discussion without an objective, numerical ranking system (Thompson, Citation2022). Next specific, concise themes were developed which were distinct from the codes and consolidated codes to theoretically explain the phenomena (Thompson, Citation2022). Labels were selected which were memorable phrases that were digestible to the reader and captured the essence of the theme (e.g. ‘the tipping point’ which distinguished between bullying and banter). Following this theorising took place, which was guided by the principle of themes being developed but not determined by theoretical (and conceptual) understanding (Thompson, Citation2022). An example of this was the theme of debatable intent and frequency being guided by conceptual models and definitions of bullying (Olweus, Citation1993; Stirling, Citation2009). Then a comparison of datasets took place to examine whether some codes were expressed amongst a particular cohort (e.g. type of newspaper) in the present study (Thompson, Citation2022). As the study’s aims were exploratory to build conceptual understanding, quantification did not take place here (Thompson, Citation2022). The penultimate step involved a data display (see ) to demonstrate that the theoretical contributions were reflective of the raw data. Last, the data were written up with headings denoting each theme (e.g. ‘a media view of bullying’). Themes were written in such a way (e.g. through a combined results and discussion) that a theoretical explanation was provided for the empirical data, whilst at the same time quotations were used to support this theorisation (Guest et al., Citation2012).

Table 1. The media’s representation of bullying and banter

Establishing rigour and reflexivity

It is important for authors to acknowledge their identities to ensure transparency in the research process (Russell et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the first and third author identify as white British, heterosexual men and the second author identifies as a British Pakistani, heterosexual man. The authors are experienced in sport psychology research and consultancy. Although the authors were not supporters of a specific news organisation, they would regularly use BBC and SSN to keep up to date with the current sports news. Instead of viewing this effect as a possible pollution of the data to be prevented, the authors employed a retrospective approach (regarding the influence of the study on the authors) and a prospective approach (regarding the influence of the whole-individuals-researcher on the study) (Attia & Edge, Citation2017). This approach to reflexivity enabled us to identify the significance of the author's values, emotions and information that they provided in the conceptualisation of the present study’s concerns and the systematic lens employed in the results (Attia & Edge, Citation2017; Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Additionally, during the data analysis phase critical friends were utilised (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). The responsibility of ‘critical friends’ (the first and third authors) was to discuss the interpretation of the findings and to promote reflexivity by questioning how the authors constructed knowledge (Cowan & Taylor, Citation2016).

Results and discussion

The present study aimed to understand how banter and bullying are framed within sport media reporting and how these concepts are distinguished from each other. First, the media’s view of bullying is presented which outlines how reports discuss the typical features of this behaviour such as intentionality, repetition and a culture of abuse. Second, the questionable framing as banter is presented which discusses how reports may inadvertently misappropriate this term and present a blurred line with bullying.

A media view of bullying

Sport media reports appeared to outline some of the classic components of bullying, yet a deeper inspection of these accounts revealed the questionable nature of intent as part of bullying. Furthermore, these reports discussed bullying as repetitive behaviour. Finally, the media reports discussed how various abusive actions become conflated into a view of bullying in sport.

Debatable intent and frequency

Although media reports often drew reference to the notion of intent as a feature of bullying, closer inspection of these accounts revealed how bullying was often reported as an unintentional act. As such this highlighted the potential for how perspectives at the macrosystem level may be reflected in behaviours at the microsystem level (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999) that conflict with established definitions of bullying (e.g. Olweus, Citation1993). Within media reports of abuse and bullying at Chelsea Football Club in the 1990s (Magowan, Citation2022) coaches denied being ‘bullies, aggressive and racist’ and how,

in High Court documents referenced last year, Williams denied having used certain racially offensive terms but, regarding others, claimed there was ‘no intention to cause harm’ and added he would ‘never use these words today’.

Despite not being explicitly referenced in the article, this piece highlighted an important point which contrasts with the most commonly cited definition of bullying (e.g. Olweus, Citation1993), in that an act does not need to be intentional to be bullying. Instead, these articles appear to be more reflective of recent findings in the bullying in sport literature which question the degree to which this behaviour is intentional (Kerr et al., Citation2016; Newman, Warburton, et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, the lack of specific discussion around the defendant’s description of not meaning to cause harm could convey to the reader a sense that this may lessen the effects of their behaviour and mean it is not regarded as bullying. This is problematic given more recent conceptualisations of bullying have highlighted the centrality of perceptions of harm from the victim’s perspective in underpinning this behaviour (Volk et al., Citation2014). The result is that the media may inadvertently reaffirm understanding of bullying from the perpetrator’s perspective.

This position around a lack of intent was continued in other media reports. Discussing an internal investigation at Cardiff City FC, Sky Sports News (Citation2019) reported,

Bellamy denied intentionally bullying players during his time as an academy coach. ‘I accept the report highlighted aspects of my coaching skills that could perhaps be improved. I have probably relied too much on my own life experiences playing under some of the best coaches in the world rather than assessing the sensitivities of a new generation of players. If I was insensitive in any way towards their feelings, then that was never my intention. If I inadvertently offended anyone, then I am truly sorry’.

In a similar vein to the discussion around intent, despite reporting converging around the significance of repetition as a hallmark of bullying (Olweus, Citation1993), there were contradictions in the frequency of the behaviour required to indicate this concept. This may provide further evidence for more contemporary views of bullying which reflect that this behaviour is more a function of the frequency and intensity of an act (Volk et al., Citation2014), rather than traditional definitions which stress the importance of repetition (Olweus, Citation1993). For example, Keene (Citation2022) described how jockey Robbie Dunne was found to ‘have bullied Frost at several race meetings over a sustained period of time’. Whereas Keene’s article intimated a continuous form of attack other reports discussed a more sporadic nature to bullying, ‘Mourinho has publicly shamed the 22-year-old at various points this season … Mourinho's behaviour towards the defender has been described as bullying’ (Seward, Citation2018). This article intimated a less sustained form of bullying, yet in the using the words that Mourinho’s behaviour was ‘described as’ bullying it potentially insinuated that it might be questioned whether the various actions of shaming truly constituted this form of maltreatment. This could be concerning if the reader interprets these words in this fashion, given the media’s potential influence on proximal process if an individual is interacting with it frequently (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, Citation2000) as well as its broader impact on its readership (Alexander et al., Citation2022).

A culture of abuse

Two articles published in The Telegraph in 2017 were indicative of how media reports of bullying subsumed various forms of abuse into bullying,

Swimming became the latest major sport to be engulfed by a bullying scandal on its elite programme … The coach was alleged to have belittled and criticised athletes, leading to a culture of fear within the elite set-up. (Rumsby & Davies, Citation2017)

Among the accusations made against MacDonald, a former interim first-team manager, are emotional bullying and shaming of players in front of team-mates, alienation from the group, which was interpreted as a form of punishment, personal insults, and abusive language on a daily basis. (Hayward, Citation2017)

It was apparent from these reports, that the media corroborated findings from the exosystem (see ) of sport research that bullying appears as a multifarious, heterogenous phenomenon (Farrell et al., Citation2014) which provides an umbrella for various forms of abuse and wrongdoing in elite sport. Moreover, bullying as a concept is regarded as something which can inform the culture of a sports group or organisation (Newman, Warburton, et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the media narratives of Rumsby and Davies (Citation2017) and Hayward (Citation2017), contradict micro-level conceptual models of maltreatment in the sport literature (Stirling, Citation2009). Both narratives contradict Stirling’s (Citation2009) model by suggesting that bullying typically occurs within the context of a ‘critical’ coach-athlete relationship (meso-level). This finding is particularly noteworthy and illustrates that the wider public’s view of bullying in sport may be shaped differently to those in the research community in sport, given the more significant role the mass media plays in the macrosystem of organised sport (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999).

The broad realm of issues reported on within the coach-athlete relationship was continued by Woods (Citation2023), who discussed coaches propagating bullying, fat-shaming and emotional abuse,

She was just one of many swimmers who would regularly starve themselves before being weighed and coaches would often blame poor performance in the pool on weight gain … Zara, who competed nationally with a club in the north of England, lost almost half a stone in three weeks while on a foreign trip with her coach because she was scared to eat in front of him. (Woods, Citation2023)

These media reports were indicative of the abuses of power on behalf of the coaches and were indicative of recent findings that bullying is driven by the power differentials within coach-athletes’/players’ relationships (Booth et al., Citation2023). The articles demonstrated throughout that bullying is not limited to a micro-level, peer-to-peer relationship and that individuals in authority abuse their power. As such this offers further evidence to suggest that the conceptual model of maltreatment in sport (Stirling, Citation2009) may need to be revisited to consider that bullying occurs within the context of ‘critical’ (e.g. coach/athlete) relationships, as well as ‘non-critical’ peer-to-peer relationships. More widely, by offering victims the chance to speak out, the media article was more informative of the misguided beliefs about the culture of sport and its impact on performance.

Importantly, the articles also emphasised that bullying can act as a discriminatory attack where victims have been called ‘derogatory racial names, suffered racial stereotypes, and been bullied … into showing others their genitals’ (Magowan, Citation2022). Within sport, this reaffirmed findings which discussed that racial discrimination is an important component of individuals’ experiences of bullying in this context (Newman, Warburton, et al., Citation2021), suggesting that this needs to be part of future definitions of this concept. Incorporating racial and other forms discrimination into a definition of bullying may further help sensitise sporting populations to continued issues with discrimination and raise awareness of the varied nature of bullying. Furthermore, given Magowan (Citation2022) described how victims were forced to ‘show their genitals’ it also raises questions as to whether racial discrimination may also overlap with other terms such as sexual abuse and harassment. Bullying of this nature (e.g. getting to victims to ‘show their genitals’) may also reinforce white privilege in elite/professional sporting contexts where victims are expected to engage with behaviours that are discriminatory and would not be expected of white populations.

The elasticity of banter

This dimension highlighted how the media could, at times, differentiate between bullying and banter. Specifically, media reports identified where non-inclusive actions migrated behaviour from banter into bullying. Nonetheless, the theme of the misinterpretation of jokes highlighted a more profound issue where bullying became masked and covered derogatory behaviour through the terms ‘jokes’ and ‘banter’, revealing concerns on how the media differentiated these concepts.

Misinterpretation of jokes

Analysis of the media perspective of banter revealed continued concern around the interpretation of this term. From the media’s reporting, it was apparent that jokes and banters are seen as unintentional in sport even though the behaviour was highly discriminatory. Former England Rugby Union player Luther Burrell described various forms of racial abuse which he accepted as part of a ‘need to fit in, the need to be liked’,

Every week, every fortnight. Comments about bananas when you’re making a smoothie in the morning. Comments about fried chicken when you’re out for dinner. I’ve heard things that you wouldn’t expect to hear 20 years ago. We had a hot day at training, and I told one of the lads to put on their factor 50. Someone came back and said, ‘You don’t need it, Luth, put your carrot oil on’. ‘Then another lad jumps in and says, ‘No, no, no, he’ll need it for where his shackles were as a slave’. (Simon, Citation2022)

This article provided an important characterisation to the sports readership of the painful experience of banter for some athletes which led to extreme acts of discrimination. It also challenged some of the views in sport that banter is a joke or funny, reflecting that banter also functions in a negative way (see Booth et al., Citation2023; Newman et al., Citation2022).

However, the language used in other articles raised potential issues with the sport media’s reporting of the Azeem Rafiq cricket case. ‘During his second spell in Yorkshire between 2016 and 2018, there were jokes made around religion which made individuals uncomfortable about their religious practices’ (BBC, Citation2021a). The framing within media articles around the term ‘jokes’ did create concern over what is portrayed as acceptable behaviour. The articles also revealed a sense of white privilege, where acts of discrimination around culture and ethnicity are indirectly reinforced as ‘humour’. Although it is acknowledged that banter exists as an ambiguous concept (Booth et al., Citation2023), the references the reporters made to the terms ‘jokes’ and ‘banter’ potentially disguised the seriousness of the derogatory comments which might otherwise be regarded as bullying. As such, from a moral disengagement perspective, the media may engage in a form euphemistic labelling where the damaging aspects of banter are deemphasised as prosocial jokes (Bandura, Citation2002). Furthermore, the nature of this reporting highlights concern around the media as a stakeholder, given similar research findings have established issues with the presentation of sporting stories about racism and bullying (Velija & Silvani, Citation2020). From an ecological systems theory, the media may inappropriately influence the readership’s learning and development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999) around understanding wrongdoing and promote a sense that there are different standards around what are acceptable behaviours in sport (Velija & Silvani, Citation2020). On a practical level, this may mean that the sports readership carry out or indulge in inappropriate behaviours in their own sporting pursuits.

The tipping point

Although some media articles may have inadvertently used terms like ‘jokes’ (e.g. BBC, Citation2021a) in such a way that inappropriate acts may be misinterpreted as banter, other reports (e.g. Sky News, Citation2022) strove to demonstrate where banter crossed the line. Amongst some of the media, they referenced how the acts of discriminatory behaviour and other forms of abuse were not classified as banter,

While some fans were engaged in harmless banter and fun with the former Manchester United star [Rio Ferdinand who was broadcasting for BT Sport], the defendant took this a step further, engaging in unpleasant hand gestures, and jumping up and down … ‘Not only was it offensive, it was racist’. (Sky News, Citation2022)

Moreover, this notion of there being a divide between banter and bullying was also highlighted in response to an independent review of institutional racism at Cricket Scotland. The article highlighted,

inappropriate use of language, in some cases, which would be racist but considered simply as banter. Concern that sledging is being used as an excuse to racially abuse opposition players. Lack of understanding of the impact of language and behaviour on individuals. (Dewar, Citation2022)

This was a further indication of the categorical presentation within media reports that discriminatory behaviour separates banter from bullying. Importantly, the reference to ‘inappropriate use of language’ provided a potentially positive avenue for the media to send clear messages to the public about the constituents of wrongdoing in sport and where behaviour cannot be legitimised as banter. As such racism is one of the forms of ‘inappropriate language’ that crosses the line of acceptability racism from playfully negative banter into something which is offensive (Steer et al., Citation2020), and more aligned with bullying. Therefore, the media play a pivotal role as part of the macrosystem in influencing individuals’ thoughts and actions at the micro-, meso- and macrosystem levels (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1999) regarding bullying and banter in organised sport. In doing so, the media can educate their audiences, and potentially benefit wider society, through identifying where banter can move from being prosocial to inappropriate in nature.

General discussion

Within recent years, several studies have sought to explore the concepts of bullying and banter as well as divide between these terms (Booth et al., Citation2023; Lawless & Magrath, Citation2021; Newman et al., Citation2022; Newman, Eccles, et al., Citation2022). However, these studies have been limited to a microsystem focus on sport performers or coaches, rather than a wider systems focus on other influential stakeholders such as the media. The present study addressed this limitation by focusing on media reports of these concepts, whilst exploring how the media represents the similar and contradicting concepts of bullying and banter.

Articles selected from a range of UK media sources discussed some of the classical features found within definitions of bullying, such as a focus on repetition of acts and various forms of harm (Olweus, Citation1993; Volk et al., Citation2014). However, the reports highlighted a more blurred line around whether bullying is intentional or not, which is more reflective of the perspective of athletes/players (e.g. Newman et al., Citation2022) than coaches (e.g. Newman, Eccles, et al., Citation2022). From a conceptual stance, the findings also provided an important contribution to the relational dynamics within which bullying occurs. In contrast to existing conceptual models in sport (Stirling, Citation2009), bullying was regarded as occurring in the context of what this framework regards as the ‘critical relationship’ between coaches and athletes (a mesosystem). Due to the significance the media has in influencing public perceptions of behaviour, this is a noteworthy finding (Lewis & Weaver, Citation2013) with clear implications for understanding bullying in sport.

In terms of banter, the study revealed important findings in relation to how the public may perceive this behaviour and as well as the macro-level interpretation of this concept within the media itself. While it was clear that the articles were keen to convey clear messages about the inappropriate and discriminatory nature of this behaviour, it was evident that some of the language used in reporting has the potential to influence the audience less positively. By stating language such as ‘jokes’ concerning reporting on discriminatory forms of banter, a perpetuation of white privilege may remain within the media and its reporting (Carrington, Citation2011). This has significant potential to influence public opinion around this concept.

Limitations and future directions

First, we considered the content of the reports themselves rather than the perspectives of the journalists themselves. Given perceptions and interpretations of bullying and banter can vary, it may be worthwhile to interview journalists and newspaper editors themselves to assess their views of this topic. To supplement this, the present study did not establish specific differences in the portrayal of bullying and banter by media outlet. Nonetheless, it may be useful to further explore whether the political leaning of the media sources affect the reporting of these concepts. Second, although the focus of the analysis was centred more towards exploring the conceptual similarities and differences between bullying and banter, the authors did make every attempt (Russell et al., Citation2022) to explore the intersectional information within the media reports of these concepts. Despite this, it may be useful for future research to consider the identities of the authors when considering reports around bullying and banter, to ensure the experiences of those being reported on are identified with (Russell et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, the findings were specific to UK print and broadcast media and did not cover international perspectives of bullying and banter. Given findings which suggest UK media can maintain white supremacy and existing power relations (Velija & Silvani, Citation2020), it is important to consider international perspectives to assess whether this view is replicated or challenged. Therefore, future research may want to investigate these concepts with a broader, more diverse set of media reports.

Implications

The present research provides key implications related to the current understanding of bullying and banter in sport. Although there was a significant crossover between recent research findings and how the media reports covered bullying in sport, it did not appear that the articles had necessarily drawn on research findings in this area. It may be particularly beneficial for both researchers and journalists interested in bullying and banter in elite sport to collaborate to inform the wider public about contemporary understanding and findings concerning these concepts. Specifically, the findings may be used as part of education around bullying and banter in school curricula and/or as part of education programmes for athletes, coaches and parents in sport. Thus the findings may reach a wider audience (Alexander et al., Citation2022) to shape the discourse around this behaviour. In line with the previous point, researchers in bullying and banter may look to provide education to those in the media about their use of language concerning these behaviours. It may be important for researchers in this field to highlight a careful use of language, for example about reporting jokes, so that the readers of articles do not misconstrue terms such as banter. Consistent with this, media reporters need to reflect on whether their stories reinforce white privilege and to be fully cognisant of equality, diversity and inclusion. Finally, it is critical to highlight that any collaboration between journalists and researchers interested in reporting information about bullying and banter in elite sport to a wider audience offers huge potential. Through these collaborations there is the potential to educate the public, as well as to show the media audience how to navigate humour-related behaviours in a positive way. Therefore the media offer a potentially important and positive voice in shaping perceptions around bullying and banter in sport.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study provides important insights around how the media may influence the public’s perception of bullying and banter in sport. Through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1999) Ecological Systems Theory, the findings illustrate how the media at the macrosystem level, may ultimately impact individuals’ relations in various interacting microsystems. The present findings reflect the blurred nature of the concepts of bullying and banter, whilst also showing the potential of the media as a voice in differentiating between appropriate and inappropriate forms of banter. Finally, the present study outlines important future directions in relation to exploring the perspectives of journalists both in the UK as well as internationally and considering intersectional information in relation to bullying and banter in sport.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the journalist(s) of each article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Alexander, D., Duncan, L. R., & Bloom, G. A. (2022). A critical discourse analysis of the dominant discourses being used to portray parasport coaches in the newspaper media. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(4), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1947885

- Attia, M., & Edge, J. (2017). Be(com)ing a reflexive researcher: A developmental approach to research methodology. Open Review of Educational Research, 4(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2017.1300068

- Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724022014322

- BBC. (2019). Peter Beardsley: Football association to investigate ex-Newcastle coach. Retrieved March 12, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/47535578.

- BBC. (2021a). Azeem Rafiq: Report by Yorkshire finds former player was ‘victim of racial harassment and bullying’. Retrieved June 12, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/cricket/58514665.

- BBC. (2021b). Azeem Rafiq: Yorkshire cricket racism scandal – How we got here. Retrieved April 1, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/cricket/59166142.

- BBC. (2021c). Fulham open investigation into academy allegations. Retrieved February 26, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/55813618.

- Booth, R. J., Cope, E., & Rhind, D. J. A. (2023). Crossing the line: Conceptualising and rationalising bullying and banter in male adolescent community football. Sport, Education and Society, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2023.2180498

- Boyle, R. (2013). Book review: Neil Farrington, Daniel Kilvington, John Price and Amir Saeed, race, racism and sports journalism. Journalism, 14(7), 983–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913480299

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1999). Environments in developmental perspective: Theoretical and operational models. In S. L. Friedman & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts (pp. 3–28). American Psychological Association.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Evans, G. W. (2000). Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social Development, 9, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00114

- Carrington, B. (2011). What I said was racist – But I’m not a racist’: Anti-racism and the white sports/media complex. In J. Long & K. Spracklen (Eds.), Sport and challenges to racism (pp. 83–99). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Cheong, J. P. G., Khoo, S., & Razman, R. (2016). Spotlight on athletes with a disability: Malaysian newspaper coverage of the 2012 London Paralympic Games. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 33(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1123/APAQ.2015-0021

- Cowan, D., & Taylor, I. M. (2016). ‘I’m proud of what I achieved; I’m also ashamed of what I done’: A soccer coach’s tale of sport, status, and criminal behaviour. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 8(5), 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1206608

- Cushion, S., Kilby, A., Thomas, R., Morani, M., & Sambrook, R. (2018). Newspapers, impartiality and television news. Journalism Studies, 19(2), 162–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1171163

- Dewar, H. (2022). Explosive report reveals Scottish cricket governance and leadership practices ARE institutionally racist … with governing body to be placed in ‘special measures’ until at least October 2023 on one of the darkest days for sport in the country. Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/sportsnews/article-11045809/Cricket-Scotlands-governance-leadership-practices-institutionally-racist-reveals-report.html.

- Dynel, M. (2008). No aggression, only teasing: The pragmatics of teasing and banter. Lodz Papers in Pragmatics, 4(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10016-008-0001-7

- Eriksson, M., Ghazinour, M., & Hammarström, A. (2018). Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: What is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Social Theory & Health, 16(4), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-018-0065-6

- Falkingham, K. (2022). Gymnastics abuse: Athletes reveal their stories after Whyte Review report. Retrieved December 13, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/gymnastics/61843628.

- Farrell, A., Cioppa, V., Volk, A., & Book, A. (2014). Predicting bullying heterogeneity with the HEXACO model of personality. International Journal of Advances in Psychology, 3, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.14355/ijap.2014.0302.02

- Gibson, K. (2019). Mixed method research in sport and exercise: Integrating qualitative research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 382–396). Routledge.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. SAGE Publications.

- Hayward, P. (2017). Exclusive: Aston Villa warned over ‘bullying’ of young players by U-23 coach Kevin MacDonald. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/football/2017/02/28/aston-villa-warned-bullying-young-players-u-23-coach-kevin-macdonald/.

- Hershcovis, M. S. (2011). Incivility, social undermining, bullying … oh my!: A call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(3), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.689

- Hurst Media. (2020a). The Guardian: One of the UK’s most influential leading daily newspapers. Retrieved September 28, from https://www.hurstmediacompany.co.uk/the-guardian-profile/.

- Hurst Media. (2020b). The Telegraph: One of the world’s greatest quality newspaper brands. Retrieved September 28, from https://www.hurstmediacompany.co.uk/the-daily-telegraph-profile/.

- Hurst Media. (2020c). The Times: One of Britain’s oldest and most influential newspapers. Retrieved September 28, from https://www.hurstmediacompany.co.uk/the-times-profile/.

- Ingle, S. (2021). Blurred lines: when does a bit of banter slip into bullying in sport? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/blog/2021/nov/15/the-line-between-banter-and-bullying-in-sport-is-a-blurred-one.

- Jewett, R., Kerr, G., MacPherson, E., & Stirling, A. (2019). Experiences of bullying victimisation in female interuniversity athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1611902

- Jonker, H., Vanlee, F., & Ysebaert, W. (2022). Societal impact of university research in the written press: Media attention in the context of SIUR and the open science agenda among social scientists in Flanders, Belgium. Scientometrics, 127(12), 7289–7306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04374-x

- Kavanagh, E. J., Brown, L., & Jones, I. (2017). Elite athletes’ experience of coping with emotional abuse in the coach–athlete relationship. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 29(4), 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1298165

- Keene, J. (2022). DUNNE AND DUSTED ‘It’s been a horrible time and I’m truly sorry’ – Robbie Dunne releases statement on Bryony Frost bullying saga. The Sun. https://www.thesun.co.uk/sport/20082476/robbie-dunne-statement-bryony-frost-bullying-saga/

- Kelly, S., & Waddington, I. (2006). Abuse, intimidation and violence as aspects of managerial control in professional soccer in Britain and Ireland. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 41(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690206075417

- Kerr, G., Jewett, R., Macpherson, E., & Stirling, A. (2016). Student athletes’ experiences of bullying on intercollegiate teams. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 10(2), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/19357397.2016.1218648

- Kleinman, M. (2023). Daily Mail proprietor Rothermere in talks with investors over Telegraph bid. Retrieved September 28, from https://news.sky.com/story/daily-mail-proprietor-rothermere-in-talks-with-investors-over-telegraph-bid-12938653.

- Langdridge, D. (2007). Phenomenological psychology: Theory, research and method. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Lawless, W., & Magrath, R. (2021). Inclusionary and exclusionary banter: English club cricket, inclusive attitudes and male camaraderie. Sport in Society, 24(8), 1493–1509. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1819985

- Lewis, N., & Weaver, A. J. (2013). More than a game: Sports media framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and enjoyment. Communication & Sport, 3(2), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479513508273

- Magowan, A. (2022). Chelsea pay damages to former youth players after racism claims. Retrieved June 12, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/60289437.

- Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292462

- Newman, J. A., Eccles, S., Rumbold, J. L., & Rhind, D. J. A. (2022). When it is no longer a bit of banter: Coaches’ perspectives of bullying in professional soccer. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(6), 1576–1593. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2021.1987966.

- Newman, J. A., Warburton, V. E., & Russell, K. (2021). Conceptualizing bullying in adult professional football: A phenomenological exploration. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 101883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101883

- Newman, J. A., Warburton, V. E., & Russell, K. (2022). It can be a “very fine line”: Professional footballers’ perceptions of the conceptual divide between bullying and banter. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fpsyg.2022.838053

- Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Parker, A. (2006). Lifelong learning to labour: Apprenticeship, masculinity and communities of practice. British Educational Research Journal, 32(5), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920600895734

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage.

- Pellegrino, S. (2023). Who owns The Telegraph? Retrieved Septemvber 28, from https://pressgazette.co.uk/publishers/nationals/who-owns-the-telegraph/.

- Pilar, P. M., Rafael, M. C., Félix, Z. O., & Gabriel, G. V. (2019). Impact of sports mass media on the behavior and health of society. A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030486

- Ponsford, D. (2023). Audience data: Sun claims top spot as UK’s most widely read commercial newsbrand. Retrieved September 28, from https://pressgazette.co.uk/media-audience-and-business-data/media_metrics/most-popular-newspaper-uk-the-sun/.

- Rumbold, J. L., Newman, J. A., & Carr, S. (2023). Coaches’ experiences of job crafting through organizational change in high-performance sport. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000328

- Rumsby, B., & Davies, G. A. (2017). Coach accused of ‘culture of fear’ as bullying inquiry is launched: Sport Formula One SWIMMING. The Daily Telegraph, 8. https://www.pressreader.com/uk/the-daily-telegraph-sport/20170324/281560880620158

- Russell, K., Leeder, T. M., Ferguson, L., & Beaumont, L. C. (2022). The space between two closets: Erin Parisi mountaineering and changing the trans* narrative. Sport, Education and Society, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2029738

- Salim, J., & Winter, S. (2022). I still wake up with nightmares … The long-term psychological impacts from gymnasts’ maltreatment experiences. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(4), 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000302

- Seanor, M. E., Giffin, C. E., Schinke, R. J., Coholic, D. A., & Larivière, M. (2023). Pixies in a windstorm: Tracing Australian gymnasts’ stories of athlete maltreatment through media data. Sport in Society, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2022.2060825

- Seward, J. (2018). Manchester United stars left shocked by Jose Mourinho's ‘bullying’ of Luke Shaw after latest public slamming. Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-5517919/Man-Utd-stars-shocked-Jose-Mourinhos-bullying-Luke-Shaw.html.

- Shannon-Baker, P. (2016). Making paradigms meaningful in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(4), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815575861

- Simon, N. (2022). ‘When is this going to stop?': England star Luther Burrell lifts the lid on racist ‘banter’ about wearing shackles as a slave and ‘jokes’ about bananas and fried chicken, from his own team-mates, as he lays bare rugby's shocking racism problem. Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/rugbyunion/article-10953063/England-star-Luther-Burrell-lays-bare-rugby-unions-racism-problem.html.

- Sky News. (2022). Wolves fan in court after ‘making monkey gesture’ at Rio Ferdinand during Premier League match. Retrieved June 12, from https://news.sky.com/story/wolves-fan-in-court-after-making-monkey-gesture-at-rio-ferdinand-during-premier-league-match-12668555.

- Sky News. (2023). The Trust Project: Sky News policies and standards. Retrieved September 28, from https://news.sky.com/feature/sky-news-policies-and-standards-11522046.

- Sky Sports News. (2019). Craig Bellamy apologises after Cardiff bullying investigation. Retrieved June 12, from https://www.skysports.com/football/news/11704/11844962/craig-bellamy-apologises-after-cardiff-city-bullying-investigation.

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. Routledge.

- Steer, O. L., Betts, L. R., Baguley, T., & Binder, J. F. (2020). I feel like everyone does it”- adolescents’ perceptions and awareness of the association between humour, banter, and cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 108, 106297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106297

- Stirling, A. E. (2009). Definition and constituents of maltreatment in sport: Establishing a conceptual framework for research practitioners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43, 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.051433

- Thompson, J. (2022). A guide to abductive thematic analysis. The Qualitative Report, 27, 1410–1421. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5340

- Tobitt, C., & Majid, A. (2023). National press ABCs: Daily Star Sunday and Sunday People record biggest annual declines. Retrieved 28th September from https://pressgazette.co.uk/media-audience-and-business-data/media_metrics/most-popular-newspapers-uk-abc-monthly-circulation-figures-2/.

- Velija, P., & Silvani, L. (2020). Print media narratives of bullying and harassment at the football association: A case study of Eniola Aluko. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(4), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520958342

- Volk, A. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2014). What is bullying? A theoretical redefinition. Developmental Review, 34(4), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.09.001

- Willson, E., Kerr, G., Battaglia, A., & Stirling, A. (2022). Listening to athletes’ voices: National team athletes’ perspectives on advancing safe sport in Canada. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.840221

- Woods, R. (2023). Swimmers ‘ruined’ by culture of fat-shaming and bullying. Retrieved 12th June from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-64256659