ABSTRACT

Recent reforms to Initial Teacher Education in England are a continuation of a decades-long political project, aiming to change the whole social complex around teachers’ professional education. But the most recent frameworks present some new inflections to the construction of learning, pedagogical relationships and difference. Positivist versions of knowledge and progress and standards-based reform as ‘a solution’ to social inequalities, need to be countered strategically with accounts of teaching and learning that reclaim the affective realm in public discourse. This investigation sets the new frameworks against the work of one early-career teacher on his master’s research project. It draws on excerpts from his dissertation and accounts by a teacher educator of working with him, concluding that hybridised accounts of learning flexible enough to encompass affect and autobiographical experience, as well as policy, research and critique, are not only professionally purposeful for those involved but also offer wider strategies of resistance.

Methodologies and the tricky question of joint authorship

First, a word about the authorship of this article. Benjamin is an early career teacher and master’s student and Gill is the teacher educator working with him on his final dissertation.

While Benjamin’s voice (in excerpts from his dissertation) is strongly framed by Gill’s reflections on the recent ITE frameworks, presenting this as a jointly authored article is a (perhaps at times awkward and no doubt imperfect) methodological choice, that nonetheless makes specific claims about the value of such teacher research and the collaboration between teachers and university-based teacher-educators. The different perspectives interwoven here, are an attempt to represent something of the social and dialogic nature of teachers’ professional learning – qualities that are incompatible with hierarchical, high-stakes, standards-based curriculum and assessment frameworks. But ‘joint authorship’ only goes so far as an attempt to represent the multi-accented discourse that has accrued over time around the social complex of teacher education that surrounds this story. While we have both followed ethical protocols for obtaining consent and acknowledging published work in relation to our research writing, there are many voices which are not formally acknowledged by our ‘joint authorship’. Pupils’ voices are central to the argument here and Benjamin’s dissertation includes remembered conversations with his PGCE tutor and other members of the teaching team, as well as colleagues and family, that stretch across several years. We are both drawing on readings that form a body of work that has been established, worked on and elaborated within our community of practice over many decades and even the anonymous peer reviewers have contributed to this article in significant ways – all of which is a context central to the argument we are making here about learning in English and teacher education.

How do you learn to be a teacher?

In recent years, we have taken to pointing out to applicants on our pre-service teacher education programme that there is a confusing array of routes into teaching – and they are not all the same. Crucially, these different routes propose very different answers to the questions of what education itself is. This makes it incumbent on new entrants to the profession to make an informed decision about what kind of profession they think they are entering, what it is for and what kind of learning process will best prepare them.

But even this contested landscape is now under significant threat from the most recent raft of government interventions to reshape teacher education. The Initial Teacher Training Market Review Report – from now on referred to as TMR (DfE Citation2021) – follows hard on the heels of the introduction of the new ITT Core Content Framework – CCF (DfE Citation2019a), The Early Career Framework – ECF (DfE Citation2019b), a new set of National Professional Qualifications (DfE Citation2020) and the proposal for a new Institute of Teaching to oversee every aspect of early career teacher development. These recent interventions need to be seen as the culmination of the decades-long, determined political project of the right in relation to schools, teachers and learning (Jones Citation2013). Partnerships between universities and schools, and the model which prepares principled and critically reflective teachers with the judgment, resources and research skills they might need to adapt and respond creatively to the range of different contexts, classrooms and curricula that they might encounter over a lifetime in the profession, are threatened by the new curriculum for initial teacher education and the structural changes proposed, since, ‘it is not only educational programmes that have been changed but “the entire social complex” of relationships and institutions through which such programmes can be realised’ (Gramsci Citation1971, 36).

The model proposed instead is narrow and instrumental and positions early career teachers as empty vessels who need to digest a body of pre-existing ‘knowledge’, derived from some notionally bounded and uncontested body of ‘high quality research’ ‘that defines great teaching’ (DfE Citation2021, 3). The story presented here challenges these versions of knowledge and research, suggesting that learning is constructed actively by the learners out of particular contexts and through the social relations of the classroom.

The structural proposals of TMR have already been denounced by many stakeholders with long experience and success in the field of teacher education (University of Cambridge Citation2021; Daly Citation2021; Russell and Price Grimshaw Citation2021; Strickland Citation2022). All these objections are important ones. However, I want to take a slightly different tack here and focus on the dismal, joyless, reductive and impoverished view of learning on which this whole project is based. The list of emotive adjectives is deliberate. My contention is that those of us seeking to promote alternative versions of learning and teacher education in England, need to do more than seek to preserve an existing ‘social complex’. Instead, as part of a wider strategic response, it seems imperative to reclaim the human and ‘affective realm’ (Jones Citation2013, 339–40) within educational discourse and debate, because the Conservative project has so effectively mobilised and politicised the language of ‘standards’ (Jones Citation2013).

Reading the documents

What does learning feel like?

At the heart of the recent initiatives listed above is a view of learning – pupils’ learning and the learning of new teachers – that is characterised in very particular ways. It is concerned with the transmission of chunks of ‘knowledge’, often referred to as ‘facts’ and this represents merely the latest manifestation of ‘the knowledge turn’ derived from Hirsch, amplified in England by Young (Citation2008) and given a potent political inflection by the rhetoric of Gove (and other Conservative ministers) – and ably explained and critiqued by many writers in this journal and elsewhere (Yandell and Brady Citation2016; Bomford Citation2019; Eaglestone Citation2020). Progress is seen as predictable and linear and teachers should learn to ‘secure foundational knowledge before encountering more complex content’ (DfE, Citation2019a, 11). The important skill for the teacher to learn, therefore, is how to break this ‘knowledge’ down into smaller and smaller parcels that can be dropped into pupils’ brains in a carefully controlled and sequenced manner, where they are picked up by the ‘working memory’ – though ‘its capacity is limited and can be overloaded’ (DfE Citation2019a, 11) – before being deposited into the long term memory, after which pupils’ need to be given repeated opportunities, strategically ‘spaced’, to ‘retrieve’ them. While there might be a superficially reassuring sound to this notional and predictable version of learning, the holes, in relation to learning in real English classrooms are immediately apparent. Rather than the distorted picture where the cognitive process of memory is isolated and cast as central to all learning requiring a sequenced acquisition of simplified steps of ‘knowledge, in the story of Benjamin’s dissertation that follows, it is precisely the offer of complexity in the tasks and a focus on pupils’ wider humanity and development – including affective, imaginative, social and psychological aspects, that enables some impressive learning. Key to pedagogy in the documents’ version of ‘learning’, are repeated opportunities to practise, to follow and repeat closely worked examples offered by the teacher or more experienced colleague. The qualities required by the learner in this joyless endeavour are ‘perseverance’ and ‘effort’.

Relationships matter

Within the documents, the learning process and the relationships involved are strictly hierarchical. In the case of pupils’ learning, it is the responsibility of the teacher to lead, tightly control, ‘scaffold’ and micro-manage all stages of the learning process which are repeatedly described as ‘exposition, repetition, practice and retrieval of critical knowledge’ (DfE, Citation2019a, 12) a hopelessly inadequate map for what pupils accomplish in Benjamin’s classroom and for his learning journey as a teacher. In the case of teacher education, the key direction of travel in the knowledge and skill transfer process, is one-way, from more experienced ‘expert colleagues’ to the novice. There is no acknowledgement of what teachers might learn from or about their pupils, or of the learning an experienced mentor may gain through working with a new teacher. It seems it is not the job of new teachers to innovate, to draw on their own experiences, subject enthusiasms or personal, linguistic or cultural resources, or even to create their own lesson plans with their pupils in mind, but rather ‘to discuss and analyse with expert colleagues the rationale for curriculum choices’ (DfE Citation2019a, 13) and to use ‘resources and materials aligned with the school curriculum e.g. textbooks or shared resources designed by expert colleagues that carefully sequence content’ (DfE Citation2019a, 13). There are many possible objections to this, not least the ossifying effect on curricula and planning and the demotivating effect on new teachers, as well as an inbuilt culture of complacency and compliance, the notion of teachers as functionaries, ‘delivering’ a prescribed set of resources in prescribed ways. Learners of any kind have very little of value to bring to the table. Their role in taking on and processing the prescribed learning outcomes is restricted to being encouraged to voice ‘prior learning’ and ‘emerging knowledge’, which are repeatedly characterised as likely to be in deficit, taking the form of ‘points of confusion’ or ‘misconceptions’ to be corrected (DfE Citation2019a, 11).

Difference – a problem or a resource?

It is striking that all the documents foreground anxiety about and hostility towards difference. It is repeatedly summoned up as a ‘bogeyman’ and a pressing justification and driver for the reforms – in the form of ‘variation’ or ‘inconsistency’ between schools or teacher education programmes. Difference always seems to be about deficit – which is why ‘standardisation’ and this whole project built around it seems like an ‘answer’ to the ‘problem’ of difference. One of the introductory paragraphs of TMR (2021) offers the need to ‘level up’ ITE programmes in England, as one of its justifications and key aims. In relation to pupils, difference seems to be imagined as something teachers need to be taught ‘to address’ (using particular kinds of skills and knowledge), specifically in relation to two categories of pupils, which appear, in these documents at least, to be clearly defined, bounded and knowable: ‘disadvantaged pupils’ and SEND pupils (those with special education needs). Presumably, the rest of the pupil body is a homogenous one, with no differences worth knowing about – and there is no sense of the different languages, cultures, identities of the classroom as either a huge part of the pleasure of teaching or a resource for learning.

The affective and political appeal of ‘standardisation’ is what drives the recent reforms in ITE in England. But standardised versions of learning, unqualified by stories of real pupils, teachers and classrooms in all their particularity, difference and complexity – and reinforced by all the structural power of the legal curriculum and assessment frameworks and new institutions – result in reducing learning to what is easily measurable, assessed and accounted for. This is harmful on many levels, too often leaving only a husk of memorised ‘facts’, routines, checklists and mnemonics, resulting in lessons that can become absurd in their structures and rationales (Anderson Citation2013). But even more seriously, as Bartolomé (Citation1994) and Hart et al. (Citation2004) have argued, a fear of difference and a focus on standardisation as a way to address social inequality, directs teachers’ attention away from ‘the living actuality, the contours and pressures of individual minds’ (Hart et al. Citation2004, 39). In doing so, it risks pathologising and dehumanising whole groups of ‘disadvantaged’ pupils (and disadvantaging all pupils), by ignoring all the rich difference of experience, culture and subjectivity that is central to human dignity as well as a crucial resource for learning:

By robbing students of their language history and values, schools often reduce these students to the status of sub-humans who need to be rescued from their ‘savage’ selves. (Bartolomé Citation1994, 176)

What good is research and what is good research?

As mentioned above, the documents under review here valorise a dominant but deeply problematic view of research in relation to classroom learning and teacher education (Yandell Citation2019). They propose the idea that research produces generalisable theories about how learning happens that can be translated directly into forms of pedagogy ‘that work’, and that professional learning simply involves practising how to carry out these moves in the classroom. They perpetuate the idea that research is done by expert researchers from beyond the school, and that its outcomes are truths about ‘what defines great teaching’ (DfE Citation2019b, 4) that somehow move beyond history, ideology and debate. Perpetuating positivist myths of knowledge that exists independently of ‘knowers’, situates new teachers as passive recipients of this ‘current high-quality evidence’ (DfE Citation2019b, 4), rather than as participants in a series of debates or producers of knowledge themselves. There is no allowance for the idea that the particularities of their identities and professional autobiographies might constitute the raw materials of learning. In contrast to this ‘theoretical transcendence or gross generalisability’ (Miller Citation1995, 23), this particular story of Benjamin’s research project seems to illuminate what is inadequate about all of this, and why the recent reforms are anti-learning, anti-professionalism and why they will ultimately fail, even in their own instrumental objectives of teacher retention and some kind of notional standardisation.

Benjamin’s research

The story of Benjamin’s research is presented here as a kind of dialogue between excerpts from his dissertation (in italics) and Gill’s perspective as the teacher educator working with him.

I first met Benjamin as his dissertation supervisor last year. The excerpts from the opening to his dissertation that follow, build on our early conversations as we got to know each other and serve as an introduction to him and his project as well as an example of ‘the autobiography of the question’ (Miller Citation1995), that says much about what is missing from the documents under scrutiny here:

The changes to exams in response to the Coronavirus pandemic have shown that the exam as an institution is just as liable to change as any other aspect of our world and the attachment that many in education have to high-stakes examinations has always interested me as a teacher. I decided to train as a teacher after several different experiences in other industries and this has always left me questioning the ease with which I have seen many practitioners accept the status quo. Outside of education I felt there was often more willingness to try things out and even to fail, and it wasn’t until I left the UK and began working in an international environment that I felt the same attitude in education. Although my current school is open to trying things out, we are still constrained by an exam system that requires conformity and constrains the imaginations of teachers and students alike …

… Education as a form of social progress for those ‘left behind’ (Doecke and Pereira Citation2012) is the stated aim of Governments across the world and it seems clear that standards-based reforms fail to deal with the wider factors that can prevent learners from progressing. Yet teachers are now positioned as the solution to a problem that has existed for decades, with improving standards of teaching now the ‘magic bullet’ (Black and Wiliam Citation1998) to solve generations of inequality in opportunity and outcome. I have seen in my own family the difference my parents’ security of income and finances made in the academic success I experienced at school compared with my brothers. When they were in school, my parents worked multiple jobs and the attainment of my brothers (despite their intelligence) was far lower than that of my sister, and me who grew up under more privileged conditions. We both attended university and none of my brothers did so and neither did either of my parents. We are one example, but many teachers can speak of countless demotivated students who do not see the point in education and good teachers are supposed to solve this problem.

… I remember very clearly a conversation with a colleague as we observed the Head Teacher at my East London School interacting with students.

He’s just a social worker really isn’t he, it’s sad isn’t it that they have to do all this stuff, they should be focussing on the school

And I agreed … .Austerity across Europe has impacted the poorest in society most acutely and in the UK it has impacted those who are the most vulnerable (Equality and Human Rights Commission Citation2018). Teachers, dealing with the social consequences of this every day, are hampered rather than helped by a strong focus on assessment and ranking that directs their attention away from creative pedagogy that responds to what pupils bring to the classroom.

… This is a system that is damaging for all those that engage with it and yet we persist. Considering the damage these exams perpetuate and regardless of how often my fellow teachers discussed the inadequacies of the high-stakes exam system, the GCSE exams have been running since before I was born and there is no alternative actively discussed. The neoliberal agenda is continually facilitated through the idea that there is no alternative and we, as teachers, have bought into this approach in our own daily practice … However, I am working for the first time in a school environment where I feel completely trusted by the leadership … . So, for me, the question of how we asses our students has arisen again …

More detailed investigation of what might be claimed for teacher research writing that includes ‘the autobiography of the question’ can be found elsewhere (Miller Citation1995; Turvey and Anderson Citation2010; Doecke Citation2013; Johnstone Citation2021). In brief, I would suggest it allows the teacher as writer and researcher to scope out and ‘enter’ some big debates, holding some authoritative voices from the worlds of school and research at a distance and, self-consciously and creatively, to weave their own professional story into that terrain. It allows for a bridge between what is obviously professional experience and other, wider autobiographical details that hold particular kinds of emotion and meaning for the writer.

Benjamin considers issues of social inequality, standards-based educational reforms, assessment and creativity and brings them into relation with his own experience as a child within a particular family, specific recollected moments from his PGCE teaching practice and reflection on his work as a teacher in different settings as well as in other kinds of employment. In the process of doing this, he is learning more about debates he has come across through reading and also more about his own experience in the light of them because he is ‘setting (his) life and interests in contexts more capacious than (his) own’ (Miller Citation1995, 23) For his readers, he is adding to and ‘filling out’ some of the categories in those debates. As a piece of research writing, it is helping him to situate himself as a teacher researcher, to consider what kinds of claims he might (and might not) make for his work. In trying to voice his feelings about a lack of professional agency, mentioning the way he and his colleagues often discuss the constraints of the exam system while continuing to operate within it, or the fact that it has taken a global pandemic to allow public questioning of the assessment system, he is ‘learning to insert the impossibilities and incongruities of (his) teaching narratives into the academic discourses’ – such as the new ‘evidence-based’ professional learning frameworks – ‘which have ignored them’.(Miller Citation1995, 24) But the writing is also making an important intervention in debates about what constitutes research, contesting, for instance, the dominant model of research promoted in the CCF, ECF and TMR because it is an example of ‘the hybridization of those discourses’. (Miller Citation1995, 23)

Above all, this was not about Benjamin performing his ‘mastery’ of prescribed knowledge about ‘what makes great teaching’ or of the discourses of academic research but mainly about us getting to know each other and together, noticing what seemed salient from Benjamin’s initial account. That seems significant as a starting point in a sequence of professional learning and quite different either from that described in the CCF and ECF (sequenced simple steps towards complex knowledge) above, or from the conventional notion within research discourses of starting with ‘a research question’.

Over several months, we began to design a research project that would allow him to go beyond familiar school schemes of work that aimed to ‘hit’ the highly prescriptive and detailed assessment criteria, to investigate how his GCSE pupils might respond to their poetry anthology in a more open way. It is a complicated and multi-faceted process to support an early career teacher in this kind of critical thinking about their daily work, helping them to negotiate strong frameworks and discourses while they are still embedded within them and to foster a process of research that involves exploration and change-making in their thinking and practice. But it can be a rich and rewarding experience, with learning opportunities for all involved. It is certainly not a linear process, beginning with ‘foundational knowledge’ offered by ‘an expert’, honed through structured opportunities for practise with feedback and assessment, as the current frameworks around professional learning prescribe. In Benjamin’s case, it involved returning to readings and conversations from earlier in his career and seeing new things in them. He took seriously Kress’ (Citation2006) insights about multimodality and English as cultural production (rather than reproduction) and he was particularly inspired by Confronting Practice (Doecke and McClenaghan Citation2011) with its detailed narrative accounts of teachers and researchers working together to offer pupils the opportunity to respond to texts in more creative and multimodal ways. He decided to do the same and to ask them to produce a visual artefact of their own in response to a GCSE poem, to present their work to the class and to reflect on their experience later in a questionnaire. He also recorded his experience in a research journal and in the early lessons, was very struck by some palpable changes in the atmosphere:

The energy in the room has been very different from what I would expect from a typical ‘standards based’ assessment on the poems that requires them to meet certain assessment criteria. Instead, I note in my journal on the first day of the project that the room has a ‘calm, focussed and positive work environment’, with students helping one another and sharing ideas.

As I walk around the room talking with students and looking at their works in progress I am struck by the pride they are taking in their work. The discussions I am having show the students have taken ownership of their work and are proud of their ideas or creations. I spend some of my time speaking through ideas with them and promoting the idea that there is not one way to complete the task and they are free to work on the poem in the way they choose. This leads some to changing their original idea, in particular, when some of the boys (and it is only boys) notice that they can create a Minecraft world to present their understanding of the poem and others are very keen to do the same.

I would say it was Benjamin’s experience of these early lessons and his experience of taking time to write about and reflect on them ‘in role’ as teacher-researcher (rather than any authoritative knowledge about what ‘defines great teaching’), that significantly shaped his learning here, generating the next steps in his teaching and his research writing.

In response to Carol Ann Duffy’s poem ‘Valentine’, many impressive artefacts were produced and Benjamin presented pupils’ reflections on these in writing and in discussion with their classmates:

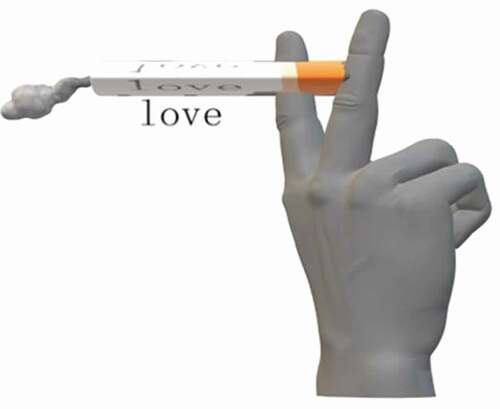

Here is what Sandra wrote when she was asked to reflect on the artefact () she had created:

My piece of work was a hand with a cigarette and the word ‘love’ on it. It shows how people go back to things even though they know they’re bad for them. I found the toxic relationship and violent imagery really interesting and thought of my idea for the work almost immediately so I wanted to see how my idea would turn out

When I read the poem for the first time the idea of love being a vice and addictive came to mind. I thought that it was represented as something bad.

Sandra reflects on her own work, interestingly, weaving together observations of her own creative authoring process (the immediacy and ease of the idea popping into her head), including what it felt like (the motivating excitement and interest of following your own strong ‘first’ thought – or in this case, image – and response to a poem through a process of making), with thoughts about her own compelling (and remarkably sophisticated) construction of the central ‘meaning of the poem’ (the possibility for addictive behaviours in romantic relationships which are damaging, or ‘toxic’ in some way, to both parties).

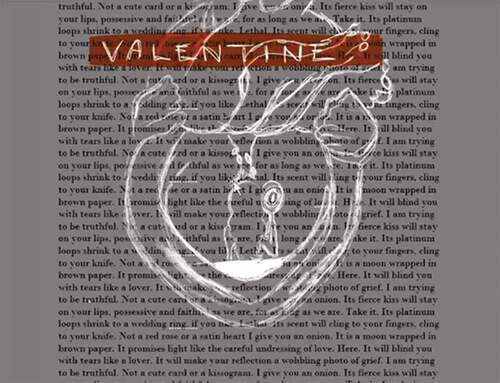

Another pupil, Belen, produced a complex, haunting design, superimposed on the ‘collapsed’ text of the original poem ():

A characteristic feature of Benjamin’s pedagogy is that the students were producing work for each other, not just for him as their teacher. This is how her peers responded to Belen’s work:

Nico: I think it’s really cool.

Ariadna: Is the writing in the back just the poem repeated?

Belen: Yes, I wanted to put the poem in the back because erm it talks about all the good stuff that er people try to tell you in order to get you to fall in love so I wanted to put that in the back so like the girl has to look at that and listen to it, but being trapped inside …

Mia: Why is the time running out on the hourglass?

Belen: Because she … the person in the poem, isn’t really confronting the lover or she isn’t trying to get help, she isn’t trying to escape. She’s accepting the fact that it’s not a very good relationship and if she doesn’t get out time is running out and I don’t think she’s going to be able to get out of the relationship, which is like my point of view on it, but there are obviously other points of views.

Pablo: Why is the title red and everything black and white?

Belen: Ah yes, OK. Everything’s black and white because usually, the way I see the poem is just it’s … it’s black and white it’s uh a relationship and it’s uh very possessive so I wanted to put the title in a different colour as the title is um, it’s a ‘deception’, you see, the title ‘Valentine’, and you think it’s going to be a poem about how people love each other and then it’s not so I wanted to differentiate that.

Our most immediate response to these pieces – and the conversations around them – was how rich they were, and excitement about just how much pupils can do when they are offered a chance and how interesting, surprising and enjoyable the process is and so unlike the world of predictable outcomes, effort and perseverance described in CCF. The frameworks deny any possibility for new subject learning being constructed out of wider cultural knowledge or even knowledge gained in another subject as, ‘pupils are likely to struggle to transfer what has been learned in one discipline to a new or unfamiliar context’ (DfE Citation2019a, 11). Drawing energy, motivation and learning from the social roles and relations of the classroom and the opportunity to perform a complex task of re-creative production, as Benjamin’s pupils do, is unlikely to happen when teachers are advised ‘to reduce distractions that take attention away from what is being taught (e.g. keeping the complexity of a task to a minimum, so that attention is focused on the content)’ (DfE, Citation2019a, 11).

It was interesting to me and Benjamin to see precisely how social roles and relations became a catalyst for learning, as other pupils responded to Belen’s work immediately in everyday, affective and admiring terms (‘It’s cool’) and with a series of ‘genuine questions’ (Miller Citation2003) that fuelled and enabled Belen’s own responses. In the ways in which she forms, reforms and shapes her own explanations, where she is ‘reaching for’ and refining her thinking, it was very clear to us that she was not simply repeating earlier learning (and certainly not retrieving nuggets of knowledge from her short or long-term memory), but rather developing and realising it there and then, in the social and dialogic moment.

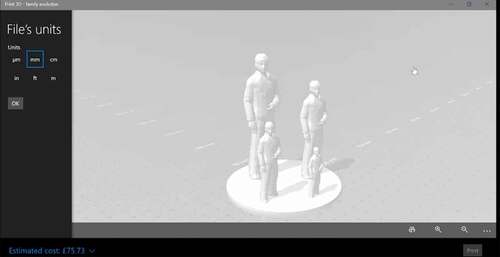

One pupil posed a question for Jorge:

Diren: I have a question. Why did you do growth and not anything else to reference the poem?

Jorge: Because you can’t really stop growth, it’s like a metaphor, cos the relationship’s just changing, they’ve lost control and they can’t really stop it and you can’t really stop growth either …

Jorge was the first pupil to present an artefact printed on a 3D printer () and his presentation was met with cries of ‘He’s 3D printed it!’ – a visceral response of admiration and excitement, that struck Benjamin who recognised it at the time as a heightened moment. Eventually it became a gateway, inspiring other pupils who went on to draw on their own enthusiasms for digital media, in some cases building elaborate Minecraft worlds with interiors and exteriors, and many and various symbols drawn from and constitutive of their close readings of the poem. We felt Jorge’s work, using the unusual language of 3D printing, encouraged other pupils to draw on these out-of-school enthusiasms, media and modes in a way that was motivating and meaningful for them. English often draws most powerfully on shared cultural and social resources of the classroom, something that is not acknowledged in the frameworks and is likely to be squeezed out by a relentless focus on individual learners practising and repeating a series of micro-steps towards notional nuggets of curricular knowledge. Pupils are learning from each other here, not in any simple sense of knowledge transfer. Rather, they are drawing energy, ideas and motivations from the classroom relationships and roles constructed over time and in this particular activity.

The varied, nuanced and attentive readings of the original poem and the confidence and agency the pupils communicated when offered this role of expert author in relation to their own ‘re-creative’ text (McCallum Citation2012), was something unfamiliar for Benjamin and he saw his own pedagogy and particular pupils in new ways. Rather than measuring each pupil’s performance on this task against prescribed criteria, he found his reflections opened up a more human, relational and longer developmental perspective on their progress, another crucial kind of professional learning for him. He said this, for instance, about his thinking about Jorge and his image of unstoppable growth representing the way being ‘in love’ might be about being ‘taken over’ and constructed by powerful discourses:

Jorge is considering the whole text in his response, not simply picking out language features for analysis, but has engaged with the poem on his own terms. In his introductory letter to me at the start of the term, he shared his lack of confidence in speaking in English and I wrote back that we could work on this together throughout the year. I’m reminded of this interaction as I consider Jorge’s work, thinking of how empowering tasks that engage the whole learner can be in their allowance for broader responses … The model Jorge printed reflects not only an understanding of the poem that is evidently complex, but also highlights the ‘idiocultures’ (McCallum Citation2012) that exist in classrooms, how they can be shared and the value that understanding these can have for the teacher.

In contrast to the version of learning in the documents, there is no sense here of pupils climbing ‘the ladder of learning’ from the simple steps of ‘foundational knowledge’: nobody needed to ‘teach’ Jorge about the 3D printer or Sandra about addictive behaviours and yet both are able to draw on existing knowledge, concepts, skills and experiences as well as the affordances of different modes and media, to think more about love and relationships and about the poem. And what would ‘climbing the ladder’ look like in this case? Ascending to something more complex and worthwhile? What they are achieving here – in various surprising, unpredictable, unique and delightful ways – is already complex and worthwhile. Far from relying on simple steps, the learning arises precisely from the opportunity to engage in a complex task in a social context that encompasses ‘big picture’ thinking about interpretation of a text, as well as attention to the formal linguistic and structural details of their own and Duffy’s texts. While I agree with Sawyer and Mclean Davies that it is worthwhile, professionally and politically, for English teachers to consider and articulate ‘the kinds of literary knowing their students are encountering in subject English’ (2021, 114), I am not sure this is where the primary value of English as a school subject lies. The more important (social, cultural and learning) achievement is almost hiding ‘in plain sight’, in the kind of practice described here. It is not primarily to do with progress over time towards a future subject expertise within taxonomies of knowledge of any kind and any attempt to fit this kind of learning into the frameworks’ categories, such as ‘foundational knowledge’, seems at best pointless and at worst damaging to all concerned. What is already achieved here in this classroom, in the making and negotiation of meanings in relation to literature and language and the simultaneous construction of the kinds of identities and social relations that allow this to happen – is what I have previously called the cultural production of the classroom (Anderson Citation2015).

Valeria’s beautifully realised, painted response below () invites the kind of writerly creative criticism that most English teachers enjoy: the thickly textured paint, the impossibly smooth exterior to the onion skin and the scratchy sinister roots surrounding the sickly idealised, cartoonish and commodified love-heart. That kind of creative critique draws on meanings, categories and judgements from a rich mix of autobiographical and textual experiences, an aesthetic experience of Duffy’s original poem and Valeria’s intertextual response to it, rather than referring to a pre-existing list of prescribed criteria. That is a compelling, and joyful learning activity, so unlike the mechanistic assessment that goes on in many English classrooms. If the aim of the reforms in teacher education frameworks is to retain teachers, they need to acknowledge the powerful motivation and professional learning derived from agency and subject enthusiasm mobilised in this enjoyable and creative way.

Benjamin explored this creative critique of pupils’ work in different ways through his dissertation and it is notable that in his analysis of the pupils’ artefacts, he increasingly coins his own categories of judgment, describing pupils’ work variously as ‘brave in its minimalism’, comparing it to other cultural forms that have personal meaning for him, such as the minimalist designer Deiter Rams or making links to the New Romantic movement in his discussion of culture and class. As his research progressed, drawing on a piece of fictionalised research writing shared by his PGCE tutor several years previously, Benjamin decided, as an alternative approach to assessment, to take his own creative critique a step closer to a novelistic form where the writing itself is foregrounded in the way meaning is made of the research evidence.

We lose ourselves in the discussions that blur our sense of lunch.

‘It’s that time already?’

Oh no, I don’t want it to end … a long distant memory of a time when we didn’t have to compare ourselves to one another.

An essay turned upside down on a desk to hide his shame, doesn’t quite fit with what we thought we’d be doing in these rooms.

Yet we are here with the blood dripping, or red paint slipping and sliding down to the classroom floor. We are questioning what was her intention when she created this living presentation of the poem from before? And we can ask and ask and ask, why did you include the blue background? Good question! Go on … tell us!

This was something Benjamin initiated as a method of analysis in the process of writing his dissertation. An extension of his thinking about making more space for his pupils’ creative responses, it also arose from conversations with Deirdre Diffley-Pierce, his tutor on the PGCE (pre-service teacher education programme) several years previously, and specifically from his memory of a piece of fictionalised research writing she had shared earlier in the MA course. But it was also a point of learning and negotiation for me and I wondered (with some powerful discourses about ‘systematic research methods’ in my own head), whether introducing a brief experimental bit of creative analysis late on in the project was maybe a ‘hybridization too far’. His own justification in his methodology chapter was persuasive. In his dissertation, Benjamin quotes a section from Diffley-Pierce’s (Citation2017) fictionalised account, her story of observing a student teacher where the fictional version of herself laments the way the classroom is filled with grids and charts that seem to be ‘reducing and reducing’, until all the frail, tantalising and ragged flesh of thought had been trussed up – well and truly bound and then he comments:

As I read this, I am sent back to my own lessons observed by Deirdre and her excitement in our discussions afterwards that would leave me feeling like I was walking on air for days. Her encouraging words at the time, to allow time for the classroom conversation to flow and see where it goes were so influential for me as a practitioner and Deirdre’s voice is with me as I teach and engage with students to this day. At the end of my course in 2018 when I read this story, everything fitted into place and it was such a powerful and unforgettable moment. Just as I have drawn on the power of narrative in my research, professional autobiographical stories like this are important in my justification of methods too. The inclusion of my own creative reflection on Valeria’s work is an opportunity for the reader to engage with the text in a different way and read into it what they will, as well as for me to engage with my creative identity as a teacher, in the way Diffley-Pierce does in her piece.

There is complex learning here about research and narrative and we decided his creative analysis should stay in. It allowed him to (re)connect as a teacher with the expressive language arts at the heart of his experience of English as a subject and to draw on stream-of-consciousness techniques in a way that echoes Joyce and Woolf. His writing across the dissertation is also hybridised and is flexible enough to represent something of the negotiation between personal and professional, between past and present and between wider contexts and official frameworks and the immediacy of classroom interactions. By investigating his subjective, affective and embodied experience as a teacher in the classroom (and drawing on it in justifying his research methodology), he is constructing important learning for himself and also making it available to others.

Conclusions

What is left out in the UK government’s ideologically-driven and exhaustive attempts to atomise, generalise and standardise the process of (professional learning), is space for what is human, relational and particular. This is not a trivial matter and even less a matter of just making everyone ‘feel good’, because learning depends on and is derived from these. An undue focus on memory at the expense of other cognitive, social, emotional and psychological processes, distorts learning to the point where it becomes absurd, banal or grotesque. This assertion is based both on my own long observation of and reflection on learning in English classrooms such as Benjamin’s and also on theoretical perspectives on human development such as Vygotsky’s idea of consciousness as ‘an overall system, within which other psychological functions and systems always interrelate’. (Barrs Citation2022, 184). If the attention of new teachers and teacher educators is focused on complying with cumbersome (bureaucratic) frameworks that insist on reducing complex socio-cultural processes of learning in which there are always many variables at play, to a series of micro-steps of things ‘to learn that … and learn how to’ (2019b, p.4), then there will be no room for the kinds of discussion I had with Benjamin. This is not just a question of time, but of the roles, relationships and structures involved – ‘the entire social complex’ around teacher education.

Part of the argument here, is that rather than positioning new teachers as recipients of ‘knowledge’ derived from highly selective readings of ‘authoritative’ research, there should be a focus on teachers as researchers, investigating learning in their own contexts and in partnership with their pupils, as well as with educators who can help them access wider perspectives and stand outside the day-to-day priorities of the school. Of course, new teachers need to learn about a range of possible pedagogical approaches but research writing that centres affect and ‘the autobiography of the question’ and allows for its consideration in more ‘capacious’ theoretical and political contexts, should be central to professional learning.

All of this is re-presenting and making visible again a very different tradition of professional learning from that proposed by the current reforms. However, ‘what comes next’ is also a matter of political strategy. I would argue that it is no longer enough for teacher education programmes in England to ‘demonstrate compliance’ and yet again to take a deep breath and conduct a tortuous paper exercise to squeeze practice like that represented by Benjamin’s research into a standards-based straight-jacket that clearly doesn’t fit. Of course, it might be (and no doubt will be) possible to argue that elements of Benjamin’s pedagogy could be construed to fit categories like ‘foundational knowledge’. But a key argument here is that it is precisely because their definitions of knowledge and research do not recognise that learning is constituted in relationships and dialogue, that the new frameworks and structural changes are something to be resisted rather than ‘worked with’. Undoubtedly, the frameworks are part of a wider attempt to dismantle values, structures, traditions and communities of practice and they are ideological in intent and political in purpose. The notions of learning and learning relationships that underpin them are so fundamentally at odds with the values and practice described here, that we felt it was important to present a detailed account of a well-established version of the social complex around teacher education, rather than entering into a process of negotiation with the unhelpful categories proposed by the new frameworks.

Certainly, the strategic response should include a determination to reclaim the affective realm in public debates about learning. This means talking more about what is interesting and pleasurable within an expanded version of English as a creative subject involved with cultural production, what is motivating, energising and rewarding about inclusive and collaborative pedagogy and how a model of teacher research that integrates reflective discussion, writing and wider reading into everyday classroom practice can produce sustaining professional learning and the emotional and intellectual rewards of professional agency. All of this is essential if we are to educate and retain good English teachers. In addition, there could be opportunities to reimagine the partnerships between universities and schools across several years of early career development, building on existing practice in thinking more about how teachers might write about or represent their teaching experiences in creative ways, and how university-based teacher educators might collaborate with them in a wider range of classroom research projects. In the spirit of ‘hybridizing’ narrow and problematic discourses about learning and making links with wider movements for social and political change, there is scope for more research and investigation that centres and amplifies teachers’ and pupils’ stories about their particular experiences of, feelings about and acts of resistance to the current curriculum and assessment frameworks, including the new frameworks around teacher education.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the pupils as important participants in this research and the team of teacher educators whose work is mentioned here or informs the writing. We are very grateful for the dialogue with the anonymous peer reviewers for their careful and constructive readings that helped to shape this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gill Anderson

Gill Anderson taught English in London secondary schools and colleges for fifteen years and has worked in teacher education in school and university settings since 2003. She is interested in all aspects of learning in English, and particularly in teacher development and the relationships between reading, writing and talk in classroom learning.

Benjamin Elms

Benjamin Elms is in his 4th year as an English teacher. He has worked in London and in international schools. He is interested in creative and multimodal responses to texts in the English classroom and in exploring wider forms of assessment of pupils’ learning in English.

References

- Anderson, G. 2013. “Exploring the Island: Mapping the Shifting Sands in the Landscape of English Classroom Culture and Pedagogy.” Changing English 20 (2): 113–123. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2013.788291.

- Anderson, G. 2015. “What Is Knowledge in English and Where Does It Come From?” Changing English 22 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2014.992203.

- Barrs, M. 2022. Vygotsky The Teacher. Oxon & New York: Routledge.

- Bartolomé, L. 1994. “Beyond the Methods Fetish: Towards a Humanizing Pedagogy.” Harvard Educational Review 64 (2): 173–194. doi:10.17763/haer.64.2.58q5m5744t325730.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 1998. “Assessment and Classroom Learning.” Assessment in Education 5: 7–74.

- Bomford, K. 2019. “What Are (English) Lessons For?” Changing English 26 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2018.1519370.

- Daly, C. 2021. “Expertise in being a generalist is not what student teachers need.” Accessed 3 March 2022. https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/ioe/2021/12/15/expertise-in-being-a-generalist-is-not-what-student-teachers-need/

- DfE [Department for Education]. 2019a. “ITT Core Content Framework.” Accessed 28 February 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-training-itt-core-content-framework

- DfE [Department for Education]. 2019b. “Early Career Framework.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-career-framework

- DfE [Department for Education]. 2020. “National Professional Qualifications Frameworks: From Autumn 2021.” Accessed 29 June 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-professional-qualifications-frameworks-from-september-2021

- DfE [Department for Education]. 2021. “ITT Market Review Report.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-training-itt-market-review-report

- Diffley-Pierce, D. 2017. “A Fable: The Happy Teacher.” In Students, Places and Identities in English and the Arts Creative Spaces in Education, edited by D. Stevens and K. Lockney, 148–161. London: Routledge.

- Doecke, B., and D. McClenaghan. 2011. Confronting Practice. Australia: Phoenix Education.

- Doecke, B., and I. S. P. Pereira. 2012. “Language, Experience and Professional Learning.” Changing English 19 (3): 269–281. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2012.704578.

- Doecke, B. 2013. “Storytelling and Professional Learning.” English in Australia 48 (2): 11–21.

- Eaglestone, R. 2020. “’Powerful Knowledge’, ‘Cultural Literacy’ and the Study of Literature in Schools.” Impact 26: 2–41. doi:10.1111/2048-416X.2020.12006.x.

- Equality and Human Rights Commission. 2018. “The Cumulative Impact of Tax and Welfare Reforms.” Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series, Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/cumulative-impact-assessment-report.pdf

- Gramsci, A. 1971. “On Education.” In Selections from the Prison Notebooks, edited by Q. Hoare and G. Nowell-Smith, 24–43. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Hart, S., A. Dixon, M. J. Drummond, and D. McIntyre. 2004. Learning Without Limits. Maidenhead: OUP.

- Johnstone, L. 2021. “The Autobiography of the Answer: Emerging Specifically and Particularly as an English Teacher.” Changing English 28 (3): 306–315. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2021.1902280.

- Jones, K. 2013. “The Right and the Left.” Changing English 20 (4): 328–340. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2013.855559.

- Kress, G. 2006. “Reimagining English: Curriculum, Identity and Productive Futures.” In Only Connect: English Teaching, Schooling and Community, edited by B. Doecke, M. Howie, and W. Sawyer, 31–41. Kent Town, South Australia: AATE/Wakefield Press.

- McCallum, A. 2012. Creativity and Learning in Secondary English. London and New York: Routledge.

- Miller, J. 1995. “Trick or Treat? the Autobiography of the Question.” English Quarterly 27 (3): 22–26.

- Miller, S. M. 2003. “How Literature Discussion Shapes Thinking.” In Vygotsky’s Educational Theory in Cultural Context, 289–316. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Russell, T., and J. Price Grimshaw. 2021. “A Look at Recent ITT Inspections.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.teachbest.education/a-look-at-recent-itt-inspections-by-terry-russell-and-julie-price-grimshaw/

- Strickland, S. 2022. “What next for an EFC that is already failing new teachers and mentors?” Accessed March 24, 2022. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/what-next-for-an-ecf-that-is-already-failing-new-teachers-and-mentors/

- Turvey, A., and G. Anderson. 2010. “Tasks, Audiences and Purposes: Writing and the Development of Teacher Identities within pre-service Teacher Education.” In Critical Practice in Teacher Education: A Study in Professional Learning,edited by R. Heilbronn and J. Yandell, 58–73. Bedford Way Papers 35. London: IOE Press.

- University of Cambridge Faculty of Education. 2021. “ITT Market Review: full consultation response.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/news/downloads/itt_review_download/2108121145-Consultation-response-announcement.pdf

- Yandell, J., and M. Brady. 2016. “English and the Politics of Knowledge.” English in Education 50 (1): 44–59. doi:10.1111/eie.12094.

- Yandell, J. 2019. “English Teachers and Research: Becoming Our Own Experts.” Changing English 26 (4): 1–12. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2018.1556006.

- Young, M. 2008. Bringing Knowledge Back In: From Social Constructivism to Social Realism in the Sociology of Education. London and New York: Routledge.