ABSTRACT

This article critically assesses claims that India has entered a new party system after the 2014 general elections, marked by renationalisation with the BJP as the new ‘dominant’ party.’ To assess these claims, we examine the electoral rise of the BJP in the build-up to and since the 2014 general elections until the state assembly elections in December 2018. Overall, we argue that despite the emerging dominance of the BJP, a core feature of the third party system -a system of binodal interactions- has remained largely intact albeit in a somewhat weaker form. Furthermore, by comparing the post 2014 Indian party system with key electoral features of the first three party systems, we conclude that the rise of the BJP has thrown the third-party system into crisis, but does not yet define the consolidation of a new party system.

Introduction

This article seeks to substantiate claims about the changing nature of the Indian party system, following the 2014 general (national parliamentary) elections and 30 state (subnational) legislative assembly elections which have taken place since. More in particular, it examines and challenges the assertion that the 2014 general elections marked the start of a ‘fourth party system’ in India’s post-independence electoral history.

Scholars of Indian party politics have identified three distinctive phases or ‘party systems’ in India since 1952 (Yadav Citation1999), the first two of which (1952–1989) were marked by the dominance of the Congress Party, the party which led India into independence and shaped its constitution. Although Congress maintained its hold on central politics until 1989, scholars have usually identified two distinctive phases within this period of one-party dominance. The first phase or so-called ‘first party system’ lasted from 1952 until 1967. In this period, Congress dominated the centre and nearly all of the Indian states. The second party system covered the period between 1967 and 1989. In this period, Congress retained its dominant position at the national level (except for a brief period between 1977 and 1979) but faced fiercer competition from other parties in the states with which it engaged in an often-confrontational way. This period was also marked by higher electoral volatility and mobilizing strategies of the Congress which varied significantly from state to state.

One party-dominance broke down in 1989 with the emergence of a ‘post-Congress’ polity. However, it took a decade of unstable coalitions and minority governments (1989–98) before multipartisan tendencies in Indian politics had fully crystallized into a new party system, India’s third (Yadav Citation1999; Singh and Saxena Citation2003). This party system was marked by electoral competition between two pre-electoral coalitions, namely the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance and the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance – it became known as the ‘two national alliances’ (National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution Citation2002) or binodalFootnote1 system (Arora and Kailash Citation2013). This pluralized party system also coincided with diverse forms of party competition in the states and the de facto decentralization of the Indian polity.Footnote2

Nonetheless, with the comprehensive and resounding reelection of the incumbent United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in the 2009 elections to a second term, in which the Congress Party improved its own seat share by over 37 percent, coalition politics in India appeared to be entering a new phase. Some observers even proclaimed the beginning of a re-nationalization of India’s party system (The Hindu Citation2009), while others interpreted the 2009 election results as a sign of its further fragmentation (Jaffrelot and Verniers Citation2011). The result was also seen as evidence of the Congress party’s skill at forging strategic state-level agreements with regional(ist) parties while overlooking programmatic or ideological concerns (Kailash Citation2009). Overall, the prognosis was that a return to single-party governments was unlikely in the near future.

All of this changed in 2014 when a landslide victory in the general elections gave a decisive majority to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the lower house of parliament. Significantly reducing the strength of the opposition, it was termed a dramatic result (Sridharan Citation2014) and a critical turning-point (Palshikar Citation2014). The BJP’s majority in the Lok Sabha, with 282 (52%) seats, was both unexpected and extraordinary. Furthermore, Congress, with less than 20 percent of the vote was reduced to 44 seats in the federal lower house. In this context, the 2014 election result was associated with the renationalisation of Indian politics (Vaishnav and Smogard Citation2014) in which the BJP had become the new ‘dominant’ party’ replacing the Congress as the ‘system-defining’ party of the first and second party systems (Chhibber and Verma Citation2014). Indeed, some authors have gone as far as to identity the 2014 elections as the start of a fourth party system (Chhibber and Verma Citation2018).

In this article we assess the validity of this claim based on a detailed assessment of the electoral performance of the BJP and other political parties since the 2014 general elections. We argue that these developments demonstrate that at the national level the third party system has come under severe strain. In fact, the extent to which party competition is still ‘binodal’ can be questioned when the key node in one of the alliances has shrunk to about a fifth of its previous size (in seat share) while the other node has now amassed more than half of the parliamentary seats on its own, weakening the relative strength of its alliance partners. Yet a measure of dominance cannot be based on one single election result alone, certainly not in a multi-level democracy such as India. Overall, we make three claims.

Firstly, we support the view that the BJP is asserting its dominance across India’s multi-level party system since 2014. Yet, this process is still ongoing, and as we will demonstrate not irreversible. Furthermore, ‘one party dominance’ is usually associated with a party which, ‘over time, is much more successful in elections, in parliament and the government than any other party’ (Bogaards Citation2011, 1743–1744), yet there is no consensus on how long the party needs to be successful for (for at least two consecutive general elections?), at which levels (federal and/or regional?), and on how success is measured (votes and/or seats?). Furthermore, we provide empirical evidence to show that BJP dominance does not necessarily meet all of the criteria which Palshikar (Citation2018, 37) has attributed to party dominance ‘in the electorate’Footnote3; namely (1) the inability of any polity-wide party (especially the Congress) to provide a national alternative to the dominant BJP; (2) the possibility of ad hoc anti-BJP coalitions at the state level which lack the ‘nodal’ stability of the bipolar nodes in the third or post-Congress party system; (3) the progressive decline in the electoral support of regional and regionalist parties; and (4) the continued centrality of Modi as a strong central leader. Especially on the second and third, and perhaps at the time of writing (February 2019) even on the final criteria, the ‘dominance’ of the BJP is not necessarily established as much as is often assumed (on this point see also Diwakar Citation2016).

Secondly, using a Gini-based measure of party nationalization (Bochsler Citation2010) and a measure of party system congruence (Schakel Citation2013) we demonstrate that while the BJP has improved its nationalization score since 2009, the party system as a whole remains as denationalized as the party system in previous cycles of general and state assembly elections since 1999. Furthermore, the BJP vote share and its nationalization does not yet parallel that of the Congress during the first and even second party systems.

Finally, by comparing the current Indian party system with the first three party systems, we argue that the fourth party system is not yet upon us. This is so for two reasons. Firstly the decline in BJP support in some legislative assembly elections and several setbacks in by-elections between 2015 and 2019 illustrate that inter-party interactions which entail a decisive shift in voter-party linkages – a defining feature of party system change (Sartori Citation1976, 43–44)Footnote4 – are far from established. Secondly, the pre-2014 structure of binodal competition marked by pre-electoral alliances – a core feature of inter-party interactions (Mair Citation2012, 94) marking the third party system – has far from collapsed.

In a nutshell, although post 2014 the BJP is dominant, destabilizing the balance in electoral support between the two nodes within each alliance (NDA and UPA) and between both alliances, to infer from this that the binodal system has given way to a one-party dominant ‘system’ would seem to be a conclusion more generous than just. All we can say is that the system of binodal interactions that characterized the third-party system is ‘in crisis’. However, the third party system may breakdown if the BJP reproduces electoral support with only small-scale shifts in vote shares (leading to an absolute majority of seats) in the 2019 general elections.

In what follows, we first analyze the assertion of BJP dominance in the 2014 general elections (section 1) and in the assembly elections which have preceded the national election and followed since (section 2). We analyze the territorial spread of the vote, the campaign methods by which it was achieved and the extent to which that support was drawn equally from polity-wide, regional or regionalist parties. In the third section we provide evidence to query the start of a fourth party system by placing the rise of the BJP into a longitudinal perspective, especially with reference to the first and second party systems. The conclusion summarizes our main argument.

Making sense of India’s 2014 election results: The assertion of BJP dominance

In the federal election of 2014, the BJP claimed a landslide victory. The party won 282 of the 543 seats in the lower house of parliament by itself and 336 seats together with its allies of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), handing an unprecedented defeat to the incumbent Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA), which was reduced to 60 seats (of which Congress only captured 44). These results illustrate the rise of the BJP (up from just 116 seats in the 2009 elections). However, some scholars believe that the BJP win with only 31.3 percent of the vote share is underwhelming (Moussavi and Macdonald Citation2015). The illusion of a landslide, so they argue, was the result of the first-past-the-post system, where no minimum threshold of votes is required to win elections. Furthermore, although the BJP fielded 427 candidates (out of 543 single member-districts), its strike rate would have been considerably lower without seat-sharing arrangements or pre-electoral alliances. The BJP aligned itself with 10 parties in the National Democratic Alliance with which it made seat-sharing arrangements ahead of the elections (Sridharan Citation2014, 21).

Even so, 31 percent is a remarkable feat, especially in view of the fiercely competitive nature of elections in the coalition era since 1996. The vote share of the first party within the ruling coalition typically ranged between 23 and 28 percent. The BJP’s success in 2014 unfolded in a context in which elections had become even more contested (in 34.8 percent of constituencies there were more than 16 contestants as against 28.6 percent in 2009 (Election Commission of India, Electoral Statistics, 2016)). The results were also dramatic because the BJP improved its vote share by 12.5 percent whereas the support for Congress dropped by 9.2 percent.

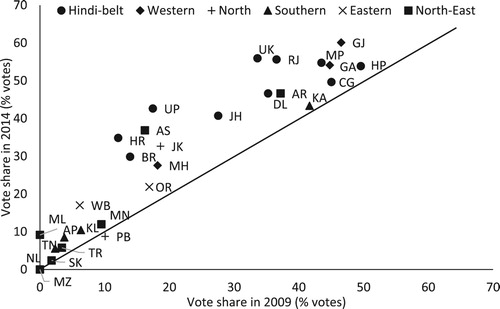

The 2014 election results are a telling demonstration of the BJP’s ability to maximize the vote-to-seat multiplier, or vote efficiency, to swing tightly-contested seats in its favour. However, to what extent was the rise of the BJP territorially (un)even, and why? The question is relevant because the BJP – being traditionally weak in the Northeast and South of India – has long been seen as a Hindi Belt (north and central India except Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir) and western-India-centered party. To answer this question we organize India’s states under five categories: Hindi Belt, East, North, North-East, South, and West (see online Annex, Table A1). We compare the results of the 2009 and 2014 Lok Sabha elections. reveals both the absolute and relative performance of the BJP in different states. In relative terms we compare low (0–10 percent vote share), middle-level (11–30 percent vote share) and high-level support states (31–50 percent vote share). Anything beyond the 50 percent mark would signify exceptionally high support levels. The entire Hindi Belt and the West gave high and middle-level support to the BJP in 2009, while most of the South and the North-East expressed low levels of support. Karnataka (South) and Arunachal (North-East) were exceptions as high-level support states and Assam (North East) was among the middle-level support states.

Figure 1. BJP vote shares in the 2009 and 2014 federal elections for 29 states.

Notes: See Table A1 in the Annex for the full names and classification of the states.

shows that in 2014, although the BJP vote advanced in nearly every state, the gains, relative to 2009 elections, were highest (11–25 percent increase) among the middle-level support states, followed by the high-level support states. The middle-level support states of the Hindi Belt such as Haryana, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh and the North Eastern state of Assam became high-level support states, as the BJP more than doubled or even tripled its vote share. High-level support states in 2009 such as Gujarat (West), Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Himachal, Madhya Pradesh (all Hindi Belt), and Goa (West) forged ahead to become ultra-high support states with more than 50 percent support for the BJP in 2014. Quite surprisingly, however, the BJP’s vote share did not increase significantly in many of the low-level support states (less than five percent increase) except West Bengal (10.7 percent increase) and Meghalaya (8.9 percent increase). Nonetheless even the relatively smaller gains in the North-East, South, and East of India mark a substantial achievement since support for the BJP and its ideology in these regions was almost entirely absent before. Furthermore, the exceptions among them, for the same reason, require some further explanation.

In West Bengal, significant relative gains pushed the BJP into third position. Given that the CPI (M) lost more than 10 percent of the vote, scholars have speculated on the BJP’s potential to overtake the CPI as the largest opposition party within the state (Banerjee Citation2016). By crossing the 20 percent support mark in Odisha, the BJP could also emerge as a credible alternative to the Congress there. Relative vote gains were also considerable in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, even though support for the party remains well below the 10 percent mark in both states.

We argue that the impressive performance of the BJP in some states which are generally averse to the Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) politics of the BJP can be attributed to the campaign style and messaging of Prime Ministerial candidate Narendra Modi. In his relentless campaign rallies, Modi, in addition to playing the development card, sought to broaden his territorial support by appealing to distinctive regional sentiments and customs. This ‘regional messaging’ took place despite the fact that the BJP’s campaign organization was highly centralized. A review of the speeches which Modi delivered in various parliamentary constituencies reveals that he not only wore the traditional headgear and costume representative of each state and spoke a few opening sentences in the appropriate regional language, but also that he attempted to play to the sentiments of regional parties (the online annex provides an overview of the main campaign strategies per state). His speeches extolled the ideals of revered state leaders from an earlier era, while criticizing the current regional state leaders for not upholding their predecessors’ ideals and not being true to their own people. He even focused on constituency-specific local issues and promised favours tailored to each state’s regional concerns and local situation. He also assured states of a specific formula to achieve double-digit growth. He promised to deliver the best public services in each state, citing the example of Gujarat, which he claimed to have modernized himself during his term in office as its Chief Minister.

Paralleling the uneven vote share across different categories of Indian states, the BJP’s gain in seat share in the 2014 elections remained territorially uneven. The party won 208 seats in just eight states adding 142 seats to what it had won in 2009. The gains were strongest in Uttar Pradesh (+61), Maharashtra (+14), Bihar (+10), Madhya Pradesh (+11), Gujarat (+11), Rajasthan (+21), Haryana (+7), and NCT of Delhi (+7). In five other states the BJP won 50 seats, either maintaining or consolidating its seat share: Karnataka (17), Assam (7), Jharkhand (12), Chhattisgarh (10), and Himachal Pradesh (4). The BJP also managed to seize all constituencies from incumbents in Jammu and Kashmir (3) and Uttarakhand (5). Seven major states resisted the rise of the BJP, restricting the party to eight seats in total: West Bengal (2 out of a total of 42), Tamil Nadu (1/39), Andhra Pradesh (2/25), Odisha (1/21), Telangana (1/17), Kerala (0/20), and Punjab (1/13). From 11 seats in the North East (excluding Assam) the party could win only one. Thus, while the BJP could not make a breakthrough in these seven major states, its victory in terms of seat share was formidable in the Hindi Belt and the Western states, geographic areas in which it stood strong already.

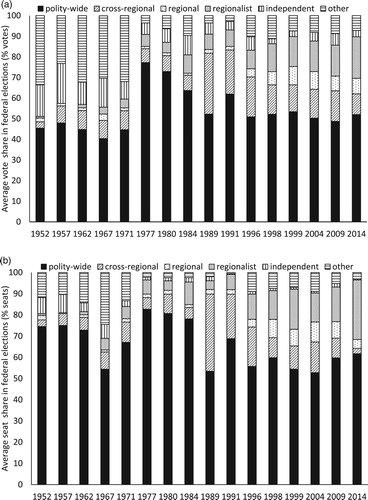

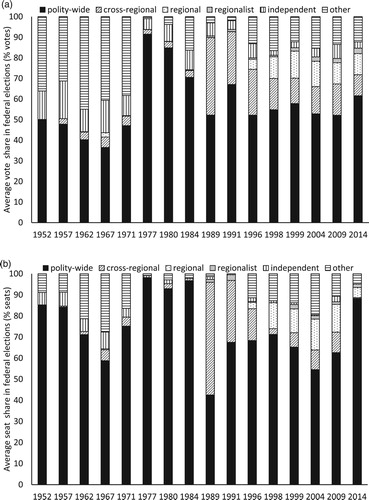

A second and related way of trying to make sense of territorial variations in the vote is to assess where the BJP vote gains have come from by type of party. Is this primarily from other polity-wide parties, from cross-regional parties or from regional or regionalist parties? We define a polity-wide or national party as a party which participates in general and state assembly elections in more than half of the states whereas a cross-regional party is a party which participates in more than one but less than half of the states. Regional and regionalist parties share a state-specific following, but as Adam Ziegfeld (Citation2014) observed, regionalist parties, unlike regional parties, emphasize regional or cultural nationalism or represent concerns that are specific to their state. Based on this definition, we have identified sixty-nine parties in India which are regional or regionalist. The online appendix provides a list of parties and their categorization as polity-wide, cross-regional, regional, and regionalist parties. We also include independent candidates and other remaining parties that contested elections. We zoom in on longitudinal shifts in the support base for these various parties in the final section, but here we only discuss findings which compare the 2014 general elections with the 2009 general elections. (A and B) present the share of the vote and seats in general elections per type of party.

Figure 2. (A) Vote share in federal elections per type of party (1952–2014). (B) Seat share in federal elections per type of party (1952–2014).

Notes: Vote and seat shares are weighted by the size of the state electorate. See Table A2 in the onine annex for a classification of parties.

(A) demonstrates a modest rise in the vote share for polity-wide parties in the 2014 general elections compared with the 2009 result. The BJP gained about 12.5 percent whereas the Congress vote share dropped about 10 percent. Not all voters who deserted the Congress party embraced the BJP. As Oliver Heath (Citation2015) observed, the BJP was able to attract only 33 percent of those who voted Congress in 2009. Former Congress support may have gone to regional or regionalist parties. The BJP also stole away votes from cross-regional parties, such as the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Communist Party of India and various splits from this party. Furthermore, it eroded the support base of regional parties. For instance, the BJP won 93 seats from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar alone where it competed against regional parties and Congress was not even a major player. In his analysis of the 2014 general elections, K.K. Kailash observed that regionalist parties have been able to withstand the rise of the BJP better than so-called regional parties (Kailash Citation2014; see also Tillin Citation2015). In fact, (A) shows that support for regionalist parties substantially increased between 2009 and 2014 (from 15 to about 20 percent of the vote) in contrast with (cross-)regional parties which saw their share of the vote decline (from 22.0 to 17.6 percent). Similarly, (B) illustrates that the representation of polity-wide parties in the Lok Sabha based on seat shares has continued a slightly upward trend since 2009. The BJP defeated Congress to such an extent that it could absorb about 85 percent of all seats attributed to polity-wide parties. Indeed, most direct bilateral contests between the BJP and Congress were won by the former (Palshikar Citation2014). (B) also confirms that regionalist parties have been able to hold onto their seats in the Lok Sabha much more successfully than regional parties. In fact, regionalist parties represent more than a quarter of Lok Sabha seats (compared with only about 14 percent in 2004), whereas the seat share for regional parties has shrunk from above 9 to scarcely 4 percent.

Is there any relation between the success of the BJP in the Hindi Belt states and its relative ability to outperform regional parties more so than the regionalist ones? To answer this question, we plot electoral performance of the six party types for the Hindi Belt states. We find that regional parties are more often found in the Hindi-heartland where BJP support has been more pronounced than in the non-Hindi Belt states of the East, North-East, and South of India. (A and B) illustrate the share of the vote and representation of seats in the Lok Sabha for the ten Hindi Belt states only. In comparison with the polity-wide results shown in (A and B), the support for polity-wide parties is substantially higher in the Hindi Belt states. Regionalist parties were never strong in the Hindi Belt, but several regional parties (most notably the Samajwadi Party, Janata Dal United and the Rashtriya Janata Dal) performed poorly in 2014, with many of their predominantly OBC (Other Backward Caste) or Dalit (Scheduled Caste) vote base flocking to the BJP instead. In other words, in the Hindi Belt vote changes not merely reflect a move away from Congress to the BJP, but equally from regional parties to the BJP.

Figure 3. (A) Vote share in federal elections per type of party (1952–2014): Hindi Belt states. (B) Seat share in federal elections per type of party (1952–2014): Hindi Belt states.

Notes: Shown are vote and seat shares weighted by the size of the electorate of the Hindi Belt states: 6 for 1952–1962; 7 for 1967–1999; 10 for 2004–2014. See Table A1 in the online annex for a classification of states and see Table A2 in the online annex for a classification of parties.

The making and consolidation of BJP dominance: State elections in the build up to and since the 2014 federal election

The magnitude of the BJP success in 2014 propelled the party to a more prominent role in subsequent assembly elections. The party went on to win no less than 16 state assembly elections between October 2014, expanding its control (either on its own or in coalition) to 21 states by March 2018 from just five in 2013. How did it happen? Is there an element of continuity in the factors that led to the party’s unprecedented victory in the national elections and its impressive performance in the subsequent state assembly elections? Did the unexpected win of the BJP in the 2014 general election now also start to erode the support base of the regionalist parties in subsequent state assembly elections as said parties cannot longer exert influence in national coalition politics. Equally, has the support base of the Congress Party eroded further in state assembly elections since, given the party’s weaker representation in national politics and the desire of third parties to align themselves with the BJP as the most likely winner?

To answer these questions, one needs to look at state elections before and after the 2014 federal election. In fact, we identity the 2012 December Gujarat election as a critical state assembly election. Its nationalizing and mobilizing impulse on the electorate can be read by contrasting BJP support in state assembly elections between January 2008 and 31 December 2012 with the party’s electoral following in later state assembly elections. confirms the December 2012 Gujarat elections as a watershed. In our calculations, states are weighted equally by averaging state assembly election results. We compare separately for state assembly elections in all 30 states (plus elections in the union territory assemblies of Delhi and Puducherry) and in the 17 largest Indian states plus Delhi (see online Annex Table A1). The latter count for more than 90 percent of the population.

Table 1. Vote shares in regional elections.

clearly demonstrates that the support for the BJP, in terms of vote share, increased significantly in state assembly elections post 2012, rising on average by 7 percent compared with state assembly elections held in the period between January 2008 and December 2012. The rise is significant, irrespective of whether it is measured across all states, the 17 largest states plus Delhi, the Hindi Belt, or non-Hindi Belt states.

Indeed, our findings make a further distinction between Hindi Belt states and the non-Hindi Belt states for reasons set out above. clearly demonstrates that although the support for the BJP rises in both categories of states, that rise was less steep in the non-Hindi states; leaving a considerable gap in its performance across both sets of states. Mimicking the rise of the BJP is the sharp fall in support of the Indian National Congress, especially in the non-Hindi Belt states. The less pronounced fall of the Congress in the Hindi Belt may well be explained by the fact that the party was already reduced to a minor party in some of the Hindi Belt states most notably Bihar and Uttar Pradesh well before the 2013 assembly elections.

In terms of seat share, the rise of the BJP is especially significant in the Hindi Belt states, where electoral support of around 38 percent () easily translates into seat shares of more than 50 percent. Although the decline in support for the Congress Party generates a significant drop in seats shares for the party between 7 and 10 percent across all states, until November 2018 that drop was momentous in those Hindi Belt states in which Congress has been engaged in bipolar competition against the BJP. Successive wins for the Congress in three important Hindi-belt states (Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh) narrowed this gap to about 10 percent.

In below, we have listed the performance of the BJP, Congress Party (INC) as well as a set of regional or regionalist parties in order to analyze in how far the rise of the BJP has altered party competition in the states. For each state, we list the nature of dominant party competition (classified on the basis of their two strongest parties in vote-share between 2004 and 2009). Party competition can revolve around national or polity-wide parties (as in most of the Hindi Belt states, except for Uttar Pradesh and Bihar), pit a national against a regional (as in Bihar or Uttar Pradesh) or regionalist party (as in much of the North-East, South, East, and Maharahstra), or involve competition between two regional(ist) parties (as in Tamil Nadu). We consider assembly elections between 2004 and 2009, 2009 and 2014 and since 2014 until December 2018. lists for each state, the position of the party holding the largest and the second largest share of votes. is a summative table, distinguishing between different forms of party competition by listing the number of states in which the BJP, INC, a regional or regionalist party comes first or second.

Table 2. Party competition in 30 states since 2004.

Table 3. Summary of party competition in 30 states since 2004.

clearly illustrates the rising support of the BJP (marked in bold) across all type of state party systems since 2014. The party is first in five states in which party competition (based on the 2004–2009 classification) is predominantly between polity-wide parties (but one down from its position in 2004–09). In Delhi the AAP displaced Congress as the largest party in the 2013 and 2015 assembly elections, but the BJP is the strongest opposition party (and also captured all Delhi seats in the 2014 parliamentary elections). With the exception of Jharkhand, the BJP did not come first or second among the 16 states in which competition revolved between a national party (Congress, CPI) and a regional(ist) party between 2004 and 2009. Now it is the strongest party in six states among that cohort and it is placed second in a further two. That the BJP has not advanced further is largely due to the sustained success of the regionalist parties which, as in the 2014 general elections have been able to hold on to their top positions much better than regional parties. Regional(ist) parties dominate about as many state assemblies after 2014 as between 2009 and 2014 (see ). Finally, by displacing regional parties from power in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar the BJP has become the largest in two states in which competition revolved mainly between regional parties, but it has not been able to break through in Tamil Nadu where regionalist parties continue to dominate.

The evolution of the Congress (underlined in ) tells a different story. Except for Delhi the Congress remains the second largest party in those states with competition between national or polity-wide parties only. As, we will discuss below, it even wrested back control from the Bharatiya Janata Party in the November–December 2018 elections in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan, three Hindi-heartland states. However, with the exception of Mizoram, Kerala, Odisha and Telangana it is not well placed to fight back in those states where polity-wide parties compete against regional or regionalist parties. In several of these states the BJP has displaced Congress as the largest party or pushed it into third position. illustrates the advance of the BJP as first or second party at the expense of the INC. Regionalist and regional parties more or less held their strength within the party system, albeit more successfully so in case of the former.

What enabled the BJP to do so well in most state assembly elections since 2014? Firstly, the BJP rode the coattails of its national win in state assembly elections that were held in 2014, shortly after the general election (Haryana, Maharashtra, Jammu and Kashmir, and Jharkhand). Engineering political defections and caste arithmetic were integral to the plan – for instance, in Haryana, the BJP engineered defections by offering tickets to 32 rebel leaders of the Congress and the Indian National Lok Dal (INLD), mostly Jats, while at the same time appealing to its core constituency among non-Jats (First Post Citation2014). Furthermore, in none of the states did the BJP announce its chief ministerial candidate. The party’s campaign image built on Modi and his call for corruption-free politics was key to its success (see online Annex for an overview of regional campaign narratives).

Yet, state Assembly elections in 2015 did not go as planned. In Delhi, the BJP did not win, as voters could opt for a strong and corruption-free alternative instead; that of Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), a party which like the BJP also mobilized young volunteers in tireless grass-roots campaigning (Mathur Citation2014). Something similar happened in Bihar, where Nitish Kumar, Chief Minister since 2005, provided a credible and ‘corruption-free’ alternative to the BJP. Furthermore, playing on regional sentiment, Kumar outmaneuvered Modi: his ‘Bihari versus Bahari’ (outsider) slogan catapulted a ‘Grand Alliance’ (in which two regional parties and the Congress joined forces) to an outstanding victory in the assembly (Kumar Citation2015). Furthermore, while Kumar stuck to his model of ‘inclusive development’, the BJP, by 2015, had appeared to have switched back from a development message to identity politics and religious polarization (see below). In the following year, the BJP did not make headway in any of the states or union territories with strong regionalist parties (Puducherry, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal), with the exception of Assam where it displaced a twice incumbent and increasingly unpopular Congress-government (Ananth Citation2016; Roy Citation2016; Seethi Citation2016). To counter its replacement with a regionalist party, the BJP had forged a rainbow alliance with two such parties, the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) and the Bodoland People’s Front (BPF), and also engineered defections from the Congress party. Furthermore, it played to regional sentiments by employing a ‘sons of the soil’ (nativist) campaign particularly targeting ‘Muslim or Bangladeshi immigrants’, and unlike in most of the previous state assembly elections anointed a local leader as Chief Ministerial candidate ahead of the election (Misra Citation2016).

Between February 2017 and May 2018, assembly elections were held in Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Goa, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Himachal Pradesh, Gujarat, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura, and Karnataka. In Goa, Manipur, and Meghalaya, elections resulted in a fractured mandate with the Congress party winning the largest number of seats (Noronha Citation2017; Phanjoubam Citation2017). However, in each of these states, the BJP formed post-poll alliances with regional parties and independents to claim majority support. The governors in these states (always appointed by the central hence BJP government) promptly invited the BJP to form the state government, ignoring the claims of the Congress. In Karnataka, Congress prevented the BJP from adopting this strategy again by forging ties with a regional party (Janata Party) and even conceding the Chief Ministerial post to that party, despite its smaller share of the vote and seats (The Hindu Citation2018). The Nagaland elections also gave a hung verdict, with the Nagaland People’s Front (NPF) being the largest party. However, the BJP managed to form the government by supporting the Nationalist Democratic Progressive Party (NDPP) and gaining the support of smaller parties in the assembly (Phanjoubam Citation2018).

What appears to have set the 2017–2018 elections apart from earlier elections is the (selective) move away from development in the campaign (given that job-creation and economic growth figures were not living up to expectations) to ‘Moditva’ (a word-play on Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism), in which development sits alongside a narrative of Hindu nationalism (Tharamalangam Citation2016). Regional variations remain: in some states of the North-East (some of which have large tribal and/or Christian populations) the BJP reiterated its development promise and pledged to use its control of the central government to that effect. However, ‘Moditva’ played a more prominent role in the BJP’s traditional strongholds. For instance, in the Gujarat elections, to consolidate Hindu votes, Modi declared that a vote for Congress would be a vote for Pakistan and that Pakistan wanted the Congress party to win. Such statements were carefully combined with the standard rhetoric of development, opposing corruption, controlling black money and improving law and order. In Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, the BJP did not project a Chief Ministerial candidate, but fought the elections in the name of Modi himself. The party’s efficient electoral machine mobilized voters from every nook and cranny (Jha Citation2017). The BJP’s IT cell created thousands of WhatsApp groups and waged a data war, circulating provocative messages to shore up support. Furthermore, Modi carried out a relentless election campaign to project himself as a crusader against corruption and black money. By making references to Pakistan-sponsored terrorism and India’s surgical strikes in response, he sought to convey his concern for national security. He also deflected criticism related to his demonetization initiative (in November 2016, without advance warning, 85% of cash notes were withdrawn from circulation), defending it as a measure aiming to counter black money, dry up funding for terrorism, and facilitating the transition into a cashless economy. Amit Shah, the BJP President, engineered defections of OBC leaders from the BSP, SP and Congress. In an attempt to split Dalit votes, Modi promised a posthumous Bharat Ratna (India’s highest civil honour) for Kanshi Ram (the founder of the BSP and mentor of Mayawati, the Dalit BSP leader). The BJP’s emphasis on Moditva and its formidable electoral machinery did not work in Punjab though where a twice incumbent SAD-BJP government faced a credible and clean leadership alternative in the person of Captain Amarinder Singh, a seasoned Congress leader (EPW Citation2017). The November and December 2018 assembly elections put an even stronger halt to the streak of BJP wins: the BJP lost control of three important Hindi-belt states (Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan) to the Congress, but only in the case of Chhattisgarh on the basis of a decisive gap in the vote. Although Congress lost Mizoram, it retained its second place in the state party system (though the BJP increased its vote share by 8 percent compared with 2014). The same was true for Telangana. Thus, in both of the latter states, Congress is in a stronger position than the BJP to mount a potential comeback.

The third party system is in crisis, but not yet dead

Notwithstanding the BJPs impressive electoral performance, we issue a note of caution not to read too much into these victories just yet. For starters, there are some signs of the Modi wave weakening, which can be linked to four observations.

Firstly, the BJP could win only five out of 27 Lok Sabha by-polls conducted since the 2014 elections. In most of these by-elections, a united opposition defeated the BJP (The Hindu Citation2018). As a result, the BJP’s share of seats has come down from 282 to 268, four less than the halfway mark of 272.Footnote5 Since anti-incumbency will potentially reduce the number of BJP seats in the 2019 general elections compared with 2014, its reliance on the support of junior partners is likely to increase rather than decrease.

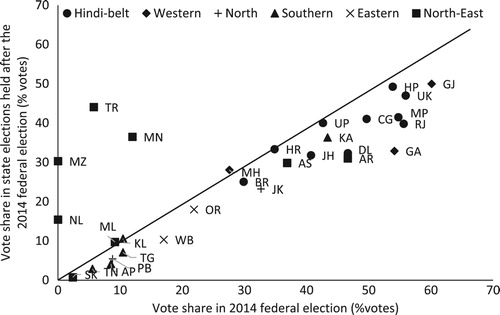

Secondly, , which is almost a perfect ‘mirror-image’ of , shows that the party’s hold on voters who had supported Modi in 2014 is declining based on the party’s performance in state assembly elections. Thus, the rising support for the BJP has not discouraged voters from supporting regional or regionalist parties even though the favourable opportunity structure in which these parties could exert influence at the centre in the coalition-era is no longer present. Significant exceptions to this trend are the North Eastern states of Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya where the party’s rise is linked to defections and Tripura, where the BJP was able to able to secure the support of the tribal community (Roy Citation2018).

Figure 4. BJP vote shares in the 2014 federal election and subsequently held state elections.

Notes: See Table A1 in the Annex for the full names and classification of the states. Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, and Rajasthan are not shown because these states did yet have held their state elections at the writing of this election article.

Thirdly, by losing three important Hindi-heartland states to Congress in November 2018, the BJP has demonstrated its vulnerability. Although in two of these states the contest was extremely close, the BJP losses here may have undermined the party’s narrative of invincibility. Such a narrative had even driven some erstwhile allies of the BJP to desert the National Democratic Alliance as its leadership style was perceived to be arrogant (The New Indian Express Citation2018). For instance, the BJP lost the support of the TDP (Andhra Pradesh).

The assembly elections of late 2018 may have forced the BJP into altering its strategy. On the one hand, opposition parties feel they can gain votes by raking up issues such as a negative growth of employment, farm distress and a sharp rise in agrarian riots, thus exposing weaknesses in the BJP’s development record, a key component of its 2014 electoral platform. On the other hand, the BJP has felt it necessary to seek ties with some (erstwhile or new) allies, realizing that it may need them to win the 2019 general elections. After all, by December 2018, the BJP controls only about a third of the state assembly seats and the party only enjoys an absolute majority in six out of 18 states in which it currently (co-)governs. Hence, it renewed electoral alliances with Shiv Sena (Maharashtra), the Janata Dal (U) in Bihar, the Shrimoni Akali Dal (Punjab), and it has forged an alliance with the AIADMK (the largest party of Tamil Nadu) and seeks to extend similar alliances in other states where it is weak (e.g. Kerala and Andhra Pradesh) (The Hindustan Times Citation2019). Finally, the BJP has mended bridges with erstwhile allies in the North-East, e.g. with the Asom Gana Parishad. In turn, the Congress is seeking to forge comparable alliances with regional allies in those states where it knows it cannot win the elections on its own. Therefore, the building of a two alliance system centred around the BJP and Congress, a core feature of the third party system is crystalizing itself once more ahead of the 2019 general elections.

Finally, Narendra Modi as Prime Minister remains a ‘trump card’ in the view of many voters. In the most recent ‘Mood of the Nation Poll tracker’, 46 percent of respondents see him best suited to be the next prime minister of India, against 34 percent who back Rahul Gandhi, the Congress leader, but in January 2017 these figures stood at 65 and 10 percent respectively (India Today Citation2019).

Apart from cautioning against reading too much in the BJP victories since 2014, we also argue that psephologists who declare the start of a fourth party system (marked by BJP one party dominance) should do so by placing the core features of the current party system into a longitudinal perspective. This can be done in three ways.

Firstly, we can revisit (A and B). Taking into consideration that most of the voters who supported polity-wide parties in 1967–1989 in general elections supported Congress or the BJP, with about 31 percent of the polity-wide vote the BJP is still some way off the dominant electoral and seat share status of the Congress Party in the 1980s, at least based on its performance in general elections. Until 1989, this never fell below 40 percent.

Secondly, we can assess the extent to which the BJP has developed into a genuine polity-wide party, i.e. by amassing its support across as many of the states and territories of the Indian federation as possible. The assumption is that dominance is not only a function of overall vote share in a national election, but also of the ability to obtain consistently high vote shares across as many of the states as possible in national and state elections. Until recently, the BJP was believed to score worse on this metric than Congress, given its traditional support in the Hindi Belt and West of India. We calculate Daniel Bochsler’s (Citation2010) party nationalization score to illustrate this point. This score expresses the extent to which a party obtains similar vote shares across all the various states of India. It ranges from 0 (in which case a party is assumed to obtain all its votes from within one state) to 1 (which assumes that a party obtains an identical share of the vote across all the states of a federation). Importantly, nationalization scores only consider the distribution of a party’s vote across the states, but not its size. below lists party nationalization scores for the BJP and INC in recent national and state elections. The national figures list standardization scores in a given federal election. The state election scores list nationalization scores for the cycle of state assembly elections starting from the date of the previous general election until the date of the general election for which a date is listed (hence the nationalization scores for state elections in 2014 calculate party nationalization on the basis of party shares in state assembly elections which have taken place after the federal election in May 2014).

Table 4. Party nationalization scores.

demonstrates that until the federal election of 2014 the Congress Party had a more evenly spread support base than the BJP in federal and state elections. But this situation reverses as of the federal elections of 2014 when the BJP and Congress have the same territorial spread and their nationalization score is just marginally (0.06) different in the cycle of state assembly elections after 2014. Therefore, in time, the data shows evidence of the BJP’s rising nationalization, especially in state assembly elections and of a decline in the territorial spread of the INC vote across national and state assembly elections since 2014. However, if we situate these figures in a more longitudinal perspective, then the nationalization of the BJP remains well below that of the Congress Party in the period of the first and second party systems. Indeed, between 1952 and 1989, the Congress obtained nationalization scores in general and state assembly elections which approximated or even exceeded values of 0.9 (Schakel and Swenden Citation2018, 16). Given that such a territorial spread was combined with vote shares in general elections which exceeded 40 percent up until the 1989 national elections, the Congress was comparatively more dominant than the BJP today.

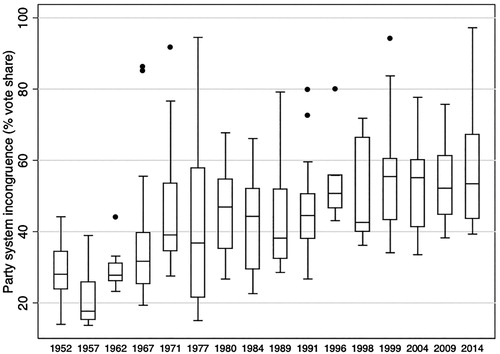

Finally, the long-term nationalization of a party system can be expressed by calculating congruence measures. We look here at one of a range of measures which have been developed by Arjan H. Schakel (Citation2013), namely party system congruence. Party system congruence measures the extent to which a particular state party system is different from a federal party system and it is the result of two sources of variation: the extent to which voters in a general election across the polity are different from the electorate within a particular state or union territory in the same (general) election and the extent to which voters within a particular state or union territory switch their vote between federal and state assembly elections. Hence party system congruence maximizes variation in the level of aggregation and the type of election. The more congruent or more nationalized a party system, the lower the degree of dissimilarity in electoral outcomes when varied by level of aggregation and type of election; the more incongruent or less nationalized a party system, the higher the degree of dissimilarity in electoral outcomes when varied by level of aggregation and type of election. In below, the x-axis denotes a set of elections, whereby each year corresponds with a general election and a set of state assembly elections held thereafter until the next general election (the 2014 data incorporate state assembly elections results until December 2018). The y-axis denotes dissimilarity values, i.e. the higher the value, the less nationalized or congruent is the party system.

Figure 5. Party system congruence between federal and state elections since 1952.

Notes: Shown are dissimilarity scores (percent votes) between a federal election and subsequently held state elections held at the same time or after the federal election but before the next federal election. Dissimilarity scores are calculated based on Schakel (Citation2013). A box plot distributes values into four groups with each 25 per cent of the observations. The values of the first quartile of observations lies in between the bottom line of the box and lower whisker, the second quartile in between the bottom line of the box and the middle line of the box which is the median, the third quartile between the median and the upper line of the box, and the fourth quartile between the upper line of the box and upper whisker. Dots are outliers which have values more than 3/2 times of the upper quartile.

Based on the evidence produced here, the Indian party system remains as denationalized as for previous cycles of general and state assembly elections since 1999. Therefore, while we do not dispute the dominance of the BJP at the moment, especially in light of Congress’s decline; the position of the BJP in the party system does not appear to be strong enough to reproduce the level of dominance which marked the more nationalized of especially the first- and second-party systems.

Conclusion: The 2019 general election as a critical juncture

The BJP’s unexpected rise to federal power in 2014 and the landslide victories in state assembly elections held close to the national elections led political scientists to proclaim the dominance of the BJP and the arrival of India’s fourth party system. In this article, we took a closer look at the data to investigate whether such a conclusion is warranted. The analysis in the first two sections clearly demonstrated that the BJP has established a dominant position in the Indian political landscape. However, we also observed the resilience of a structural split between the Hindu nationalist and regional(ist) domains of politics. The ruling party has not yet succeeded in integrating the non-Hindi Belt cultures into its discourse, despite the BJP-RSS effort to produce a narrative of inevitability and some electoral successes in the North-East.

Furthermore, the very dominance of the BJP appears to be quite fragile. The party’s rise is mainly attributable to its performance in the Hindi Belt, well known for anti-incumbency swings, except where the incumbents deliver on economic performance. The BJP, even during the so-called Modi Tsunami, could not outmaneuver regionalist parties. Finally, opposition unity, although difficult to orchestrate given the conflicting ambitions of the opposition leaders, can still pose a serious threat to the BJP’s winning streak, as was evidenced by the assembly elections in Bihar and Karnataka. More recently, the BJP lost where it appeared to be strongest: in those states where it faced a direct competition from the Congress.

To decode the spectacular rise of the BJP, we determined the December 2012 Gujarat election to be critical. We disaggregated state-by-state data on vote and seat share of the political parties based on two criteria: (a) cultural-locational attributes (Hindi Belt, West, South, East, North, and North-East) and (b) the type of political party competition. We argued that the party’s rise is linked primarily with its performance in the Hindi Belt and in the Western states where the party competes either with a national party or with caste-based regional parties. However, the party has made some unexpected advances in both national and state assembly elections in other regions as well. In some low-level support states the BJP even managed to form the government by securing post-poll alliances with regionalist parties and by engineering defections from rival parties.

Overall, we find that the BJP dominance (and the decline of the Congress) has certainly thrown the third party system into crisis, although key features of it (the strength of regionalist parties, and the forging of competing alliances centered around the BJP and Congress nodes ahead of the 2019 general elections) remain intact. Furthermore, despite the impressive set of BJP wins in state assembly elections since 2014, the BJP vote is not quite as nationalized as that of Congress during the first and second party systems. Equally, in spite of the party’s rise, India’s contemporary party system as a whole is more alike the party systems of the coalition-era, marked by comparatively low levels of congruence or nationalization of the vote. That said, we acknowledge that the current party system stands at a critical juncture.

The outcome of the 2019 elections may well reassert a more recognizable pattern of binodal party competition in which the BJP lacks an absolute majority and the NDA and UPA are more evenly matched. However, should the BJP reassert itself with an absolute majority, the fourth party system may well be upon us. Yet, critical junctures need not necessarily be followed by a new pathway; they may well reinforce an existing path. Only a resounding win in the 2019 general elections could seal the return to a one party dominant system, and in fact assert BJP hegemony, i.e. forcefully assert its ideology not just dominance.Footnote6

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Named as such to reflect bipolar competition, with the Congress and BJP as the ‘nodes’ of two competing alliances.

2. The relationship between the (de)centralization of the party system and the (de)centralization of the Indian polity is contested and a detailed debate falls beyond the scope of this paper. Chhibber and Kollman (Citation2004) argue that institutional, especially fiscal decentralization has triggered a more denationalized party system. However, there is also a widespread literature which suggests that the advent of coalition politics at the centre with the inclusion of state-based or regional parties in government induced a more decentralized polity – more so in practice (e.g. in the much less widely practiced suspension of state autonomy by the centre) than in form (constitutional change). For a summary and various articles addressing this issue, see (Sharma and Swenden Citation2017).

3. Palshikar (Citation2018) has added criteria which are not linked to electoral performance per se, but associate dominance with the social base of the party and its ability to dominate the electoral narrative. We do not touch upon both of these explicitly in this article, although briefly make reference to these in our conclusion.

4. Sartori defines a party system as ‘the system of interactions resulting from inter-party competition’ (Citation1976, 44). The notion of ‘system’ implies some degree of regularity, that is, continuity of inter-party interactions between elections (Sartori Citation1976, 43).

5. The effective strength of Lok Sabha has been reduced to 522 with two 22 seats falling vacant, as on 6 February 2019. In that sense the BJP still holds a majority with 268 seats.

6. Note that Palshikar (Citation2018) also adds two further characteristics of dominance which were left outside our analysis: the extent to which the BJP has been able to widen its social base and the ability of voters to trust its narrative irrespective of its (socio-economic) performance in the national or state governments which it controls. As Suri and Palshikar (Citation2014) and Chhibber and Verma (Citation2018) show, the ability of the BJP to capture the support of different social segments (except the Muslim minority community) is impressive, but Chhibber and Verma also point at the rising dissatisfaction among young voters (who do not share the BJPs Hindu agenda) and poorer voters (especially Dalits). Palshikar’s second characteristic is more a measure of ‘hegemony’ i.e. the ability of the BJP to exert ‘ideological, moral or cultural’ leadership or dominance over an otherwise socially diverse electorate. This would require a deeper analysis of the narratives during election campaigns and the extent to which they impregnate attitudes of voters. Furthermore, in our view hegemony is a more longitudinal process which can be the result of party dominance sustained over multiple election cycles. Since, at the time of writing, the BJP government is only completing its first term in national office, we find any evidence that hints at ‘hegemonization’ inconclusive at this point.

References

- Ananth, V. K. 2016. “Democratic Process Not Yet Lost in Tamil Nadu.” Economic and Political Weekly 51 (22): 26–28.

- Arora, B., and K. K. Kailash. 2013. “The New Party System: Federalised and Binodal.” In Party System in India: Emerging Trajectories, edited by Ajay K. Mehra, 235–261. New Delhi: Lancer Publishers.

- Banerjee, S. 2016. “West Bengal Elections. Myopic Popular Verdict in a Political Vacuum.” Economic and Political Weekly 51 (36): 28–30.

- Bochsler, D. 2010. “Measuring Party Nationalisation: A New Gini-based Indicator that Corrects for the Number of Units.” Electoral Studies 29 (1): 155–168. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2009.06.003.

- Bogaards, M. 2011. “One Party Dominance.” In International Encyclopedia of Political Science, edited by D. Badie, D. Berg-Schlosser, and L. Morlino, 1743–1744. London: Sage.

- Chhibber, P. K., and K. Kollman. 2004. The Formation of National Party Systems: Federalism and Party Competition in Canada, Great Britain, India, and the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Chhibber, P. K., and R. Verma. 2014. “It is Modi, not BJP that Won this Election.” The Hindu, June 1. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/Itis-Modi-not-BJP-that-won-this-election/article11640727.ece.

- Chhibber, P. K., and R. Verma. 2018. Ideology and Identity: The Changing Party Systems of India. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Diwakar, R. 2016. “Change and Continuity in Indian Politics and the Indian Party System. Revisiting the Results of the 2014 General Elections.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 2 (4): 327–346. doi: 10.1177/2057891116679309

- EPW. 2017. “Punjab’s Voters Settle for the Familiar Kind of Change.” 52 (11), March 18. Web-Exclusive: https://www.epw.in/journal/2017/11/web-exclusives/punjabs-voters-settle-familiar-kind-change.html.

- First Post. 2014. “Social Engineering: How Congress Lost its Traditional Vote Banks in Haryana.” October 27. https://www.firstpost.com/politics/social-engineering-congress-lost-traditional-vote-banks-haryana-1774761.html.

- Heath, O. 2015. “The BJP’s Return to Power: Mobilisation, Conversion and Vote Swing in the 2014 Indian Elections.” Contemporary South Asia 23 (2): 123–135. doi:10.1080/09584935.2015.1019427.

- India Today. 2019. “Mood of the Nation. How has Narendra Modi’s performance been as PM.” https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/web-exclusive/story/20190204-motn-poll-pm-narendra-modi-performance-1439368-2019-01-25.

- Jaffrelot, C., and G. Verniers. 2011. “Re-nationalization of India’s Political Party System or Continued Prevalence of Regionalism and Ethnicity?” Asian Survey 51 (6): 1090–1112. doi:10.1525/as.2011.51.6.1090.

- Jha, P. 2017. How the BJP Wins. Inside India’s Greatest Election Machine. New Delhi: Juggernaut Books.

- Kailash, K. K. 2009. “Alliances and Lessons of Election 2009.” Economic and Political Weekly 44 (39): 52–57.

- Kailash, K. K. 2014. “Regional Parties in the 16th Lok Sabha Elections.” Economic and Political Weekly 49 (39): 64–71.

- Kumar, A. 2015. “Where is Caste in Development. Bihar Assembly Elections.” Economic and Political Weekly 50 (45), November 7. https://www.epw.in/node/146046/pdf.

- Mair, P. 2012. “Comparing Party Systems.” In Comparing Democracies: New Challenges in the Study of Elections and Voting, edited by L. LeDuc, R. G. Niemi, and P. Norris, 88–107. London: Sage.

- Mathur, C. 2014. “The AAP Effect. Decoding the Delhi Assembly Elections.” Economic and Political Weekly 49 (12), March 22. https://www.epw.in/node/129207/pdf.

- Misra, U. 2016. “Victory for Identity Politics, not Hindutva in Assam.” Economic and Political Weekly 51 (22): 20–23.

- Moussavi, B., and G. Macdonald. 2015. “Minoritarian Rule - How India’s Electoral System Created the Illusion of a BJP Landslide.” Economic and Political Weekly 50 (8): 18–21.

- National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution. 2002. Report of the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution. New Delhi: Universal Law Publishing.

- Noronha, F. 2017. “Carrying on a Dubious Game in Goa.” Economic and Political Weekly 52 (11), March 18. https://www.epw.in/journal/2017/12/commentary/carrying-dubious-game-goa.html.

- Palshikar, S. 2014. “A New Phase of the Polity.” The Hindu, May 22.

- Palshikar, S. 2018. “Towards Hegemony. BJP Beyond Electoral Dominance.” Economic and Political Weekly 53 (33): 36–42.

- Phanjoubam, P. 2017. “BJP’s Short Term Score in Manipur.” Economic and Political Weekly 52 (11), March 18. https://www.epw.in/journal/2017/11/web-exclusives/bjps-short-term-score-manipur.html.

- Phanjoubam, P. 2018. “How BJP Won Without Winning in Nagaland.” Economic and Political Weekly 53 (10), March 10. https://www.epw.in/engage/article/bjp-won-without-winning-nagaland.

- Roy, R. 2016. “Nothing Succeeds Like Success in West Bengal.” Economic and Political Weekly 51 (22): 24–26.

- Roy, E. 2018. “How Tripura was Won.” The Indian Express, June 26. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/tripura-assembly-elections-2018-results-bjp-manik-sarkar-amit-shah-narendra-modi-5085186/.

- Sartori, G. 1976. Parties and Party Systems. A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schakel, A. H. 2013. “Congruence between Regional and National Elections.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (5): 631–662. doi:10.1177/0010414011424112.

- Schakel, A. H., and W. Swenden. 2018. “Rethinking Party System Nationalization in India (1952–2014).” Government and Opposition 53 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1017/gov.2015.42.

- Seethi, K. M. 2016. “Left Front Victory in Kerala. A Verdict for ‘Social-Re-engineering’.” Economic and Political Weekly 51 (22): 29–31.

- Sharma, C. K., and W. Swenden. 2017. “Continuity and Change in Contemporary Indian Federalism.” India Review 16 (1): 1–13. doi: 10.1080/14736489.2017.1279921

- Singh, M. P., and R. Saxena. 2003. India at the Polls: Parliamentary Elections in the Federal Phase. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

- Sridharan, E. 2014. “India’s Watershed Vote: Behind Modi’s Victory.” Journal of Democracy 25 (4): 20–23. doi: 10.1353/jod.2014.0068

- Suri, K. C., and S. Palshikar. 2014. “India’s 2014 Lok Sabha Elections.” Economic and Political Weekly 49 (39): 39–49.

- Tharamalangam, J. 2016. “Moditva in India: A Threat to Inclusive Growth and Democracy.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 37 (3): 298–315. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2016.1196656

- The Hindu. 2009. “How India Voted: Verdict 2009.” The Hindu, May 26.

- The Hindu. 2018. “The BJP’s Electoral Juggernaut Meets Opposition Unity.” The Hindu, May 31.

- The Hindustan Times. 2019. “Lok Sabha Polls 2019: After Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, BJP now Eyes Poll Alliances in Kerala, Andhra Pradesh.” February 21. https://www.hindustantimes.com/lok-sabha-elections/lok-sabha-elections-2019-after-maharashtra-tamil-nadu-bjp-now-eyes-poll-alliances-in-kerala-andhra-pradesh/story-O1wD1mne9e4AUahMXEx8XK.html.

- The New Indian Express. 2018. “Discontent of Allies May Burn BJP in 2019 Lok Sabha Election.” The New Indian Express, March 9.

- Tillin, L. 2015. “Regional Resilience and National Party System Change. India’s 2014 General Elections in Context.” Contemporary South Asia 23 (2): 181–197. doi: 10.1080/09584935.2015.1021299

- Vaishnav, M., and D. Smogard. 2014. “A New Era in Indian Politics?” https://carnegieendowment.org/2014/06/10/new-era-in-indian-politics-pub-55883.

- Yadav, Yogendra. 1999. “Electoral Politics in the Time of Change: India’s Third Electoral System, 1989–99.” Economic and Political Weekly 34 (34/35): 2393–2399.

- Ziegfeld, A. 2014. “India’s Election Isn’t As Historic As People Think.” Washington Post, May 16.