ABSTRACT

Research focusing on the Covid-19 crisis politics treats ideology mostly as an independent or intervening variable, lacking attention to the effects of the pandemic on ideological conflict and the configurations between ideas and actors and is ambiguous about its impact. To address these deficiencies, we provide an assessment of ideological change by combining accounts of political development and theories of hegemony and apply the resulting framework through a comparative history of “crisis” in Western Europe, juxtaposing the pandemic with the 2008 financial crisis. We argue that the pandemic’s ideological impact entails signs of both continuity and change, across both ideational and institutional dynamics, more change than the financial crisis, but not reaching the threshold of “a critical juncture” and thus amounts to a partial ideological reconfiguration. The analysis has implications for the Covid-19 pandemic legacy, the study of crises and the ideological terrain in the current context.

Introduction

Recent literature about the pandemic has mostly treated ideas and ideologies as independent or intervening variables, investigating the effect of partisanship on public attitudes and behaviour with respect to Covid-19 (Gadarian, Goodman, and Pepinsky Citation2021; Lipsitz and Pop-Eleches Citation2020), of party ideology on Covid-19 response (Rovny et al. Citation2022), of the ideas driving public policy responses and government ideology (Vasco Santos Citation2021). Although this helps us understand actor fixicity, how ideologies develop and are adapted remains pertinent for the evolution or inertia of ideas over time, shifting radically or incrementally, legitimising or overturning patterns of domination (Blyth Citation2011). As Berman (Citation2011, 106) explains, “from a methodological viewpoint, if we can show how different ideational variables emerge and develop over time, we will be in a much better position to trace out their independent impact on political life”.

Yet, we do not know how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected ideological configurations internationally. Some authors are “cautiously optimistic” enough to talk about the possible “end of neoliberalism” (Saad Filho Citation2020), or a change in the overall paradigm of policy making through the “return of the state” (Gerbaudo Citation2021). Others see new dangers of dehumanisation (Regilme Citation2023), microfascism is understood as “a nihilism formed in the spirit of defeat” or necropopulism, which “seeks to extinguish the life that allows people to exist” (Bratich Citation2021). Further reasons for questioning that there is such a thing as “the democratic advantage” in the West has also been projected (Drezner Citation2022). The timing of being too close to unfolding events, and the siloing of intellectual history and institutional analysis may have contributed to the absence of an accepted framework to locate manifestations of ideological struggle. Disagreement about both the extent and manner of political change may also be due to the lack of systematic comparison, making claims to emerging continuity or change in the aftermath less reliable. Therefore, we lack a historical benchmark in terms of whether the ideological map we operate in has been fundamentally redrawn if new normative legacies and policy paradigms are taking hold.

We address this in two ways: First, we place crisis politics at the heart of socio-political conflict and its ideological parameters to construct a typology and index that accounts for the type and extent of ideological reconfigurations during the crisis. In doing so we respond to the “what”, and “how” questions of studying change (Crawford Citation2018, 235–236). In line with emerging work utilising critical juncture theories to discern pandemic effects on policy areas (Kopec Citation2023; Hogan et al. Citation2022; Dupont, Oberthür, and von Homeyer Citation2020), we transpose their focus on contingency onto the systemic, ideational level, estimating the nature and extent of ideological continuity and change in the pandemic’s immediate aftermath. We understand critical junctures as historical moments or events providing opportunities for new path dependencies to form (Capoccia and Kelemen Citation2007). We relate them to how exogenous shocks signal both objective events and their construal by hegemonic and counter-hegemonic actors that instrumentalise and narrate these events in favour of either keeping in line with systemic continuity or shifting to alternative policy paradigms (Blyth Citation2002; Capoccia Citation2016).

Second, in establishing a historical benchmark for temporally relativising change, we apply our framework to the two most recent global crises as politicised in Western Europe.Footnote1 Chronologically, the first is the global financial crisis and austerity “to avert economic collapse” and anti-austerity narratives (2008–2015), and the second is protection from Covid-19 in 2020–2023 and society’s response. Both periods shared the experience and perception “of a serious threat to the basic structures or the fundamental values and norms of a system, which under time pressure and highly uncertain circumstances necessitates making vital decisions” (Boin, ‘t Hart, and Kuipers Citation2017; Twigg Citation2020). Hitherto, comparative studies have focused on the pandemic aspect, thus isolating and juxtaposing different instances of health emergencies or disasters (Dionne and Turkmen Citation2020). Instead, the conceptual underpinning of this investigation is crises more generally, as exogenous shocks to societies and economies, so that we can assess whether the pandemic health crisis constitutes a critical juncture.

The rationale behind approaching the pandemic crisis through the prism of a “comparative history of crises” is to illuminate the ideological shifts behind the socio-political conflict dynamics by temporally contextualising them. One can understand better the “criticalness” of a contemporary critical juncture if one sets it also in relation to prior events and developments, indeed other potential critical junctures whose assessment is possible through the examination of their own antecedent conditions (Capoccia Citation2015). This enhances reliability avoiding misinterpretations of say the acceleration of earlier trends or incremental change as the emergence of something new (Schot and Kanger Citation2018). Hence, we ask and show if the pandemic can be identified as a “critical juncture”, both in relation to the previous crisis and the ideological configurations in place before the pandemic started. Beyond the “relationships between ideas and institutions, ideas and interests” we thus, also engage, with “ideas and change” (Béland and Cox Citation2011).

Framework of analysis

We define ideology as a type of overarching frame and as a map of meaning through which subjects understand the world, assign significance to things, and accordingly act (Gago Citation2017; Vallas Citation1991) Although we employ the term ideology in the analytic or neutral fashion (Freeden et al. Citation2013), ideology is more than a set of ideas; it is also related to consciousness (Lukács Citation1968)Footnote2 and underpins both hegemony and counter-hegemony (Gramsci Citation1972). More importantly, ideologies are dynamic, change over time, interact with their spatio-temporal context and with each other and some are more porous than others. Often social and political conflicts are framed and fought through ideological terms (Eagleton Citation2007).

We define ideological change as a series of shifts in the articulation and constitution of ideologies, which evolve over time depending on the outcomes of power struggles. Critical junctures may provoke ideological shifts, speeding up or even reversing processes underway. Ideational change can be the outcome of a critical juncture, but as we explain further below, not necessarily of crisis. Thereafter, the relationship between ideology and crisis sometimes appears to be unclear. In the rest of this section, we seek to clarify this relationship, first, by conceptualising ideology as grounded in socio-political conflict, and then, through addressing its possible associations with critical juncture theory and crisis.

Towards a grounded theory of ideology

A grounded theory of ideology situates ideational structures in socio-political ones. Ideology, hegemony, and discourse have been employed by social theorists to explain how the social production of ideas relates to power relations (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998; Therborn Citation1999). We understand ideology, not as a fixed bundle of ideas but as a dynamic template of interpreting and politicising public affairs. Its internal patterns across political spaces are fluid and evolving in morphological terms so that some concepts can travel from the core to the periphery of an ideology (Freeden Citation1996), and so that some ideologies can travel towards or away from the power of hegemony. Power is constituted “within various ideologies”, or as in Althusser’s and Foucault’s explorations, within “regimes of truth” (Vincent Citation1996) or of “knowledge” (Broome, Clegg, and Rethel Citation2012). An ideology that becomes dominant is not necessarily more coherent than other competing ideologies, nor is it necessarily more comprehensive. It may be merely better positioned in a particular moment or situation to centre-stage some issues and marginalise other ones and offer its own frames over alternative frames through which these issues are to be understood. Ideologies that are backed up by economic force and state power can afford to have less logical coherence than other alternative ideologies (Hall Citation[2011] 2017).

Hegemony is the outcome of power battles and consists of the ability of an ideological perspective to become so dominant that its axioms appear as natural and general realities and its viewpoints as common sense (Gramsci Citation1972). Hegemony, by definition, accords mainstream status to ideologies that can inhabit distinct spaces, so that there can be establishment ideologies (such as centrist and right, centrist and left, right and far right or left and far left) that leave counter-hegemonic ideologies away from power. An ideology, not currently in power is not necessarily counter-hegemonic; only when its adherents aspire to become the future governing faction and implement a radically different policy it becomes such.

Mainstream ideology can utilise its dominant position and secure its necessary cohesion by connotations rather than denotations (Seymour Citation2014). Subaltern ideology on the other hand needs to be more carefully articulated, more robustly structured and more unified internally to stand a chance to successfully contest dominant ideology. Ideology infuses discourses, that is, the ways of language in “representing aspects of the world” (Van Dijk Citation1993, 96) so that rhetorical frames and situational narratives express underlying ideas. Both hegemonic and especially counter-hegemonic ideologies can cover a broad range of forms through discursive framing.

Still, the categories of Left and Right and the spatial understanding of party and political actors have their use in classifying the movements of both powerholders and power-opposers across the ideological spectrum of a polity (Schwarzmantel Citation2008). Within different fields of antagonism, conflict and dissent to dominant ideas are expressed in various ways and at different degrees of intensity. Each idea can entail a series of positions in programmatic terms, both ideational spirit and policy direction and even organisational and lifestyle suggestions. Hegemonic ideas need to be internalised by a substantial section of the public, expressed explicitly, and confront counter-hegemonic ideas, which spring up on different issues forming and shaping the conflict lines. This is a dynamic process whereby hegemony (and its constituent lines of conflict) must be worked upon, maintained, and constantly revised. Passive consent, integral to the functioning ideological hegemony, is to some extent necessary, but it is neither sufficient for it, nor inexhaustible (Hall et al. Citation1978).

Ideational theory and theories of hegemony are often criticised as too abstract and insufficiently grounded in structures and institutions for ideational variables to be operationalised in a valid and reliable manner (Berman Citation2011, 105–106; Bevir Citation2000, 277). This would entail understanding which ideas are in the arena, how they come to be prominent, why, and with what consequences for whom. Ideas are both exchanged within and across institutional structures but are also “enshrined” in institutions and reproduced with interaction. This reproduction or institutionalisation involves individuals, groups, societies, and political systems (Berman Citation2001, 33), necessitating a grounding of ideologies and the discourses they narrate into their context of political contestations within and outside of the state. In the absence of mapping interacting collective actors and the structural features of conflict, agency would have to be only attributed to abstract entities and processes (Hofferberth Citation2019). Whereas, in reality, ideological change happens when “perceived failures or inadequacies of the reigning intellectual paradigm(s) create a demand for new ideologes” (Berman Citation2011, 107). Both within and outside power structures, the relevant discourses and the actors who voice them are collective: social movements, parties, governments, interest and value groups, expert groups, and others.

Yet although ideological change is not agent-less and manifests in terms of both how ideologies instrumentally assemble, and structure ideas and the ways these ideas infuse behaviour (Ostrowski Citation2022), it can vary in degree. A sudden transformation of an ideology may entail either keeping its adherents in power or a shift from one ideology to another, where a counter-elite can use this transition to take power away from the former elite. A more incremental path would show signs of consolidation among new social divides and realignment in the conflicts, interests, and ideas they produce. Ideas and ideologies are engendered in socio-institutional life. Although theories of hegemony are well positioned to grasp the dynamics of ideological conflicts in the sense of their power mechanics, and by extension the mechanics of social systems, they are less able to discern shifting conflict lines because they lack a map of ideological “formats” on the ground (see Sartori [Citation2005] Citation2005). Without concrete divides in party systems, for example, such questions as “the extent to which the established ideological categories have been able to retain a coherent and recognizable identity under pressure from the pandemic debate” (Soborski Citation2021), cannot be answered. Ideologies and their discursive and performative communication are embodied within socio-political conflicts and contribute to the formation of social cleavages around them, as well as turn into programmatic positions and competitive mobilisation feeding back into the cleavage (De Leon, Desai, and Tuğal Citation2009).

To operationalise ideological change in empirically concrete terms, we refer to ideational structures – how ideas with different relations to power and political institutions are discursively articulated in the public sphere. This includes how the crisis is incorporated into pre-existing or new political spaces or sub-spaces, which are mobilised through political participation and activism. Ideational structures respond to crises as the latter “generate framing contests to interpret events, their causes” (Boin, ‘t Hart, and McConnell Citation2009, 83), as well as opportunities to be prescriptive (Vincent Citation1996; White Citation2013). Actors and entities construct crises at the same time as encountering them, communicating the responsibilities and lessons involved (Hay Citation1996).

Actors with different relations to power utilise or exploit crises in ways that suit their politics. The predominant discourse reflects the hegemonic ideology and the political spaces, which express it. The management of every situation and the controversy around it begins with identifying a threat (a natural disaster, a war, a financial crisis, or any other collective problem causing alarm). This amounts to a diagnostic framing of crisis, capturing and addressing it through a narrative about its nature, magnitude, and causes. In the context of crisis, explaining also entails blaming because it includes identifying enemies, those whose (in)actions led to the problem at hand or those who are defying the new rules. Framing crisis in a certain way, political actors can claim or imply “moral righteousness”, so to assert victimhood and ascribe responsibility (Roitman Citation2013, 31).

At the same time, the predominant discourse about a crisis will carry a prognostic framing as well, describing how the future might look like if we follow one or another policy path. When it comes to crises, therefore, the predominant discourse entails both diagnostic and prognostic framings, the former focused on identifying the systemic location of failure, the nature and logic of the threat, the causes, and agents responsible and the latter suggesting a future effect and schematising the way forward, the problem-solving task. The management of every situation includes deciding and applying a policy framework on behalf of the state, led by the executive and the governing party(ies). In the face of exogenous shocks government responses and political decision-making intermediate the consequences for the society. In connection with the threat, the adopted policy framework itself, can be opposed, or criticised, but also be effective to different degrees in mitigating the consequences of crises on public affairs. Government dealing with the crisis will be judged and opposed based on its demonstrated capacity to respond effectively, manage, and terminate the crisis. This, itself, is contested as rulers will seek to portray an effective response, while their opponents will condemn them for slowness or for the wrong (or insufficient) measures.

Counter-hegemonic forces respond negatively to the predominant discourse underlying the state’s response, through articulating dissent. Dissent can be marginal or widespread, multi-ideological or cohesive in terms of its composition, it can be expressed in the streets or online, it can be to a varying degree organised, militant, and/or effective in invoking a response from the government. Protest and dissent can be related to emerging collective problems or to the moral economy of crises whereby access to basic subsistence goods is regulated; this is so, especially for disasters and other events with a direct material impact (Barnett Citation2020). Like the hegemonic story from which it is dissenting, protesting social forces can contest government response to a crisis both diagnostically and prognostically; in fact, protesting solutions to a problem is highly likely to also reflect a dissenting voice on diagnosing the problem to begin with.

Our framework then turns to how hegemony and counter-hegemony interact within and across political parties and movements. As ideologies are enacted they correspond to political spaces, which choose either the hegemonic or the dissenting side(s), depending on the crisis topic or policy issue in question, and which manage or not through their discourses to benefit electorally out of the crisis. At one level, the ideological coordinates of (socio-institutional) conflict, dynamics of hegemony are about how ideologies correspond to specific crises, specifically how diachronic and generalisable ideological lines of demarcation between political spaces on the key left-right dimension – radical left, centre-left, centre-right, and extreme right – and their alignments as embodied in socio-political conflict reflect hegemony and its antithesis. Accordingly, distinct crises can shift or sustain the ideological coordinates of conflict, independent of the changing actual issues at stake, so that social and political spaces shift or remain fixed in terms of their positions aligning or not with hegemonic discourse (Stahl Citation2019). Ideologies are flexible and may adapt by rationalising several policy choices. Political spaces espouse policy choices that are closer to or further from the mainstream, depending on the idea or policy in question as embedded in a concrete situation of crisis. Party system openness is the second element of the dynamics of hegemony. Like the first element, it allows us to consider differentiation in public opinion often spurred by crises (White Citation2013, 164–165), yet it additionally enables a political mapping of competing crisis diagnoses and an assessment of their prominence at the elections following the crisis, that is, within the institutions.

We also acknowledge that ideas need to be connected to their materiality in the sense that collective actors will project an understanding of the world, assign significance to specific things, and act accordingly. We therefore provide thick information on actor dynamics and their relation to the material circumstances of each crisis, noting any significant shifts as regards worldviews, issue signification and the logic of appropriateness that defines actions.

Ideological change opposite critical juncture theory

Critical junctures are the formative moments in time, which precipitate shifts in the direction of historical development and set new or revised path dependencies.Footnote3 Critical junctures produce change in the cultural and ideational context as actors grapple with the conditions and problems arising and this becomes incorporated into the institutional order, infusing it with a legacy that is lasting (Sanders Citation2006), which implies a “long-term divergence in outcomes” (Slater and Simmons Citation2010). These are major events with macro-societal consequences and are typically, although not always, seen as “crises” of different sorts. When they emerge, crises entail decisions that can potentially realign social ruptures along new issue divides (Rovny et al. Citation2022, 1). Actors construct events as crises of a certain type and then promote ideas about the necessary institutional arrangements to resolve the problem; in the same way that “ideas give content to preferences and thus make action explicable” (Blyth Citation2003, 702). During a critical juncture, ideational battles lead to collective action that builds new institutions (Blyth Citation2002). However, critical junctures are not the same as “crises” because the latter do not necessarily entail change (Lowery Citation2022), whereas critical juncture theory relies on “general laws” to signify something new for a substantial amount of time (Collier and Munck Citation2017, 2–9).

For the critical juncture change is a given, while for crises, it is the possibility of change that matters, but path dependency may be its outcome.Footnote4 How a “crisis” develops into a “critical juncture” or not depends overall on whether the proponents of counter-hegemonic positions manage to assemble large enough coalitions to support significant transformative or incremental policy change, one that systemically shifts the balance of social and political power (Acemoglu and Robinson Citation2012; Collier and Collier Citation2002), so that hegemony changes hands or is severely weakened. This shifting or continuous balance is entrenched in socio-cultural divides that affect both individual behaviour and collective action (Ostrowski Citation2022). Between inertia and transformation, ideational shifts and continuities can only be traced within actual processes of mobilisation and socio-political conflict (Schwarzmantel Citation2008).

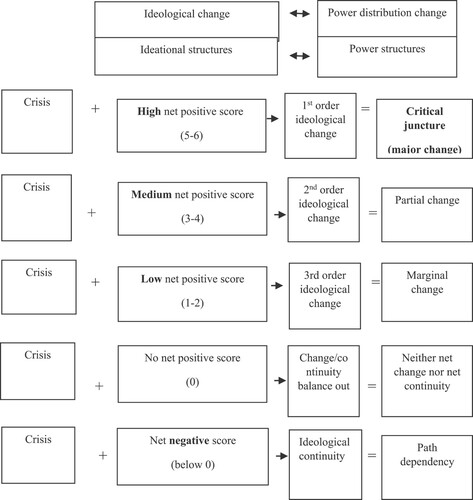

We can distinguish between change, depending on whether there are more net realignments in ideational configurations. In , the six qualitative indicators of change in the schema are guided by six questions moving from the hegemonic framing of a crisis to the counter-hegemonic framing, and then to their reflection in socio-political space. The first four indicators capture what the dominant and dissenting discourses in the party system and society have been diagnosing as the problem (and problem-creators) and suggesting as solutions. Novelty is understood as an observable change compared to the situation prevailing in the years prior to each crisis in terms of the enemies identified, and the policy framework proposed. The key matter at stake is whether hegemonic and counter-hegemonic responses introduce new content of ideological conflict, and whether new elements coexist with and balance out stability, or one of the two prevails.

Table 1. Qualitative indicators of change in ideational structures.

The last two indicators unravel novelty by looking at how ideas and positions over a crisis are associated with political spaces as embodied by parties and civil society actors, thus endogenising social and political conflict into our theoretical framework. Where, that is, are the main political spaces – radical left, centre-left, centre-right and far-right – positioned in terms of the two sides of various crisis-related debates? In addition, whether a crisis generates a political opening or vice versa a closure, and for whom (Gourevitch Citation1986), as certain ideas and interests become more popular than others.

All indicators have similar and inter-connected implications therefore each type and subtype are ascribed equal weight, and the index is additive. For instance, if the hegemonic narrative changes to align with counter-hegemonic ideas, this will have similar significance for ideological coordinates as the counter-hegemonic discourse changing to align with hegemony. If ideological coordinates change, its likely consequences – such as the emergence of challengers to the left-right divide – can be assumed to follow realignment in the threat defined and/or the policy framework proposed by either or both the hegemonic and counter-hegemonic sides. In responding to a crisis both powerful actors and counter-power diagnose and prognose within a wider logic whereby the problem informs the solution and more generally the past matters for the present.

illustrates our theoretical design of ideological change opposite a typologized threshold for a critical juncture. This is a variation of the modern understanding of critical junctures, which assumes “that change must be significant, swift, and enduring”, as well as one that is able to differentiate between degrees, hence aspects of ideological configuration (Hogan Citation2019). Adapting Peter Hall’s (Citation1993) original formulation, we disaggregate the process of ideological change and continuity into three subtypes in accordance with the magnitude of the changes involved. This provides a useful tool to discern variation across both time and space. Here, we encapsulate a full range of seven possible outcome orders between 3rd order (major) net ideological change signalling a critical juncture; 2nd order change capturing “near miss cases”; 1st order denoting relative (but not “significant, swift and enduring”) change (Capoccia and Kelemen Citation2007); as well as the adjacent notions of 1st order, 2nd order and 3rd order net ideological continuity, signalling path dependencies of various degrees and (when combined with our framework of analysis) types, too. The schema is based on a simple aggregated scoring range based on the six indicators of ideological change derived from the literature: threat and policy hegemonically defined, threat and policy counter-hegemonically defined, and coordinates of conflict and political openness.

Figure 1. Theoretical schema of critical junctures in ideological change. Source: Adapted from Hogan (Citation2019, 12).

A comparative historical perspective on ideological change and the pandemic

To apply our framework, utilisable also on the national level, we isolate a region because countries there share a similar structure of political competition – socio-economic (left-right) and socio-cultural (“new politics”) – which allows for systematic comparison of how ideologies are reflected on the ground. In addition, West European countries share similar party family constellations and social cleavage structures, again allowing to generalise among them, despite national variation. We are assuming that “changes at the system level could trigger changes in regional orders” (Paul Citation2018, 179), and thus their constitutive domestic socio-political contexts. To this sense of a regional order also contributes to the fact that almost all Western Europe is composed of countries that are also EU (European Union) member states (except Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland), and thus bounded also in a legal-political sense. In addition to their commonalities in terms of social structure and political culture broadly conceived, countries in Western Europe have a historical and geopolitical connection since the end of the Second World War, which has further evolved in more recent decades, and translated into stronger economic ties.

Having Western Europe as a demonstration case, we now move to the application of the framework constructed through an empirical assessment of the impact of the pandemic crisis on the ideological order after examining first the financial crisis and its legacy. To the extent that phenomena deriving from or indirectly linked to the financial crisis laid the social and political ground for the pandemic to affect, the previous crisis is especially crucial for a historical comparative look.

The legacy of the financial crisis

The antecedent conditions of the financial crisis were essentially the heyday of the globalisation narrative, characterised by the consolidation of neoliberalism, not only as a policy framework but also as a broader societal worldview. The Global Justice Movement emerged as the main expression of dissent focusing on the issues of poverty and social inequality and championing solidarity across national borders. At the level of geopolitics as well as ideas the West saw itself as globally dominant after the collapse of the Soviet Union – yet at the same time identified Muslim fundamentalism as the new threat to the maintenance of the “global order” as well as “liberal values”. Following the 2001 terrorist attack in the USA, the adoption of measures restricting civil liberties and human rights were taken at home along with a more aggressive tone in foreign policy involving the stepping up of the USA’s global military interventionism. Dissent was expressed in the form of the massive anti-war movement that developed in the early 2000s – the February 2003 demonstrations across many countries to oppose the Iraq War, facilitated also by the pre-existing Global Justice Movement networks and activity.

These developments shaped the ideological universe of socio-political conflict. The “conflict of civilizations” frame for example (Marranci Citation2004), upon which anti-Muslim narratives were built lent substantial support to state policy and anti-immigration arguments to conservatives, helping the ascend of the far right (Arzheimer Citation2018, 153–155; Oztig, Gurkan, and Aydin Citation2021). On the opposite side, it forged alliances between left-wingers, liberals and migrant communities dissenting with the securitisation discourse, in defence of liberty and human rights at home and peace abroad. A crisis environment was proclaimed on many occasions in the 2000s before the events of 2007/2008. Always concerning neoliberalism’s economic development potential (Held Citation2005; Touraine [Citation2005] Citation2007) and its negative political impact, that is on democracy.

The austerity drive that followed the outbreak financial crisis in 2008 was framed in solid material and political economy terms. In its aftermath deteriorating employment conditions and austerity policies came at the forefront of public debate and made material and distribution questions the central social cleavage. The stakes in the financial crisis concerned the functioning of the banking system and the economy and the threat was state bankruptcy and economic collapse that needed to be averted at any cost.Footnote5 After a brief spell of state interventionism to save the banks, neoliberalism rose resurgent again determining the policy framework pushing through privatizations, liberalisation of labour markets and cutbacks in the social budgets (Crouch Citation2011). It was as Saad Filho (Citation2010) aptly called it, a crisis “in neoliberalism” rather than “of neoliberalism”.

Whereas at the beginning of the financial crisis, the lax regulation of the banking system, the recklessness of bankers and the speculatory movements of the international money markets were seen as the causes of the recession, soon, after private banks were rescued with public money leading to piling national debt, all this were forgotten (Basu Citation2018). The hegemonic narrative shifted quickly from the monetary to the fiscal side of the economy, with the threat and the blame shifting from the external to the internal dimension. Imprudent and wasteful public spending and insufficient national competitiveness became the culprits (Walby Citation2015), and this was constantly repeated in all tones by journalists and experts parading in the media who argued that austerity policies were beneficial in the long term, and inevitable in the medium term (Mylonas Citation2014). The successful promotion of austerity was made possible through a systematic and sustained “economic story telling about debt” (Montgomerie Citation2019) resorting to simplistic arguments by politicians such as “not spending above one’s means” (Reporter Citation2012).

The dominant discourse propounded by European and national political elites and aided by the media was that cuts to social spending and market-enhancing reforms were necessary (Jessop Citation2012). The promotion of austerity varied from an ideologically offensive “extreme centre” position treating it as something good in itself, to the stance of the moderate Centre-Right and Centre-Left parties which were more pragmatic and defensive treating it as a necessary evil. Systemic banks were “too big to fail”, one Eurozone country defaulting on its national debt would lead to the dismantling of the Eurozone system, states continuing to spend more than their tax collection allowed risked state bankruptcy. Painful, yet essential austerity measures were needed to avert an economic collapse, which was to bring about chaos (Ioannou Citation2021).Footnote6 Thus, the loss of employment rights and welfare was meant as a small sacrifice, necessary to appease the global markets and through increasing competitiveness to bring back growth (Euractiv Citation2012).

Public spending cuts, especially in health and welfare, along with deregulatory drives in industrial relations promoting the liberalisation of labour markets were contested by trade unions, left-wing political parties, and social movements in several countries, especially in Southern Europe where the economic crisis was deep and austerity policies imposed through EU support mechanisms (Ioannou Citation2021). In this context, discursive conflict ensued over who was to really blame for the crisis and austerity, with the left pointing to Germany and the EU, and the right pointing to a problematic culture, whereby the average, Greek, for example, was anomic, lazy, seeking instant gratification. It was in this trope that the southern European states were characterised as PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain).

Mass mobilisations in the period 2010–2012 protested the austerity agenda and connected it with democracy, arguing overall that representative and other democratic institutions are hollowed out and damaged by a neoliberal political economy institutionalised at the EU level and beyond.Footnote7 This was the time of the “Occupy movement” and which spread from the US to numerous Western countries. In the crisis-stricken Southern Europe, Spain and Greece, for example, citizens from various political and social backgrounds without any organisational support coalesced in the squares of the main cities to protest against politicians and their austerity policies (Diani and Kousis Citation2014), as well as mobilised various other repertoires of connection, often mixing on the ground activity with social media activism. While the intensity and longevity of protests and contention varied across countries, being higher in Greece and Spain than Italy and Cyprus for example, they were produced political shifts, bigger or smaller across southern Europe (Charalambous and Ioannou Citation2017). Although its magnitude and political opportunities varied significantly between both regions and countries, protest and disruption drastically increased after 2008, indeed across the whole of Europe (Giugni and Grasso Citation2015).

While there was a continuity in the process of narrowing further the scope of the political process and hollowing out the institutions of representative democracy, especially where Troika (European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund) intervened, in some cases including evading or modifying constitutional provisions (Streeck Citation2014) and in other facilitating technocratic governments. There were also new political openings such as the rising relevance of the Greens benefiting from an inter-generational rise in environmental awareness and these parties’ partial capitalisation on the ecological protest movements, and always in the direction of institutionalisation. Democracy in Europe 25 (Diem25) was established by former Greek Finance Minister and bail-out dissenter, Giannis Varoufakis and others, as a transnational radical left movement-party and an alternative to the European Left Party (ELP), where SYRIZA continued to belong. The biggest political change was the rise of populism both on the right and on the left imbuing the mass protests challenging the predominant austerity discourse emanating from state elites (Bailey Citation2020). In a series of countries, new populist or quasi-populist movements and parties emerged from mass protests and some achieved significant electoral successes.

SYRIZA in Greece was the most characteristic example of left-populism which rose to power, but high electoral results were also achieved by Podemos in Spain, while the radical Left and its anti-austerity discourse gained ground elsewhere as shown by Melanchon’s presidential campaigns in France and the rise of Corbyn in the UK and Sanders in the USA within their respective Centre-Left parties (Labour and Democrats). Yet, populism was also witnessed in the centre (as in the case of Movimento 5 Stelle and Italia dei Valori in Italy), and most importantly the far right, both radical and extreme, including parties such as the True Finns in Finland, UKIP in the UK, National Front in France, the AfD in Germany and the Golden Dawn in Greece.

The extreme Right was also able to benefit from voter fluidity, the dissenting milieu and the protest vote and make gains not only in Eastern Europe where its ideas have taken over major parties including governing ones, but also in France, Italy, Greece, Cyprus and more recently Spain and Portugal (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Citation2022). Although again variable in terms of both country and region, the electoral success of these parties has increased substantially and is statistically correlated with the social conditions of financial crises, such as impoverishment and more broadly widespread economic grievances that constitute political opportunities for anti-immigrant sentiment, welfare chauvinism and xenophobia (Funke, Schularick, and Trebesch Citation2016).

Whereas right-wing populism emphasised national sovereignty and expressed anti-immigration narratives, it also co-opted traditional social democratic ideas about the welfare state, the protection of jobs and so on, France’s National Rally (Front) being the prime example of this. Left-wing populism on the other hand going the reverse way expressed traditional labourism, welfarism and Keynesian recipes and at the same time tried to play down notions of class in favour of the schema of the people versus the elites (Charalambous and Ioannou Citation2020). Corbyn in the UK for example talked about democratising the economy, Melenchon in France articulated a redistribution agenda and more generally the United European Left (GUE/NGL) in the European Parliament shaped a policy response on the EU level that was interventionist but not very Eurosceptic.

In any case, although merely the combination of anti-austerity and democracy signals novelty in the hegemonic as well as counter-hegemonic narratives, what changes the most with the financial crisis concerns political realignments across the crisis divide, as well as political space openness.

Ideational structures at the encounter of the pandemic crisis

The antecedent conditions of the pandemic feature both the aftershock of financial ruin and lingering questions about identity politics (immigration), the environment (climate change, foremost) and security (from terrorism). Masses of people escaping war-torn Syria or elsewhere in the Middle East and Africa, translated into a highly and toxically politicised debate about refugees, asylum seekers and migrants, in which the pro-immigration left confronted the anti-immigration right. A point of reference became the terrorist attacks across Western Europe in the late 2010s and the militarisation of security provision, as seen in Belgium (Volinz Citation2017).

Environmental issues, already mobilising substantial crowds since the 1980s also had a significant resurgence in the 2010s, a time when even the medium-term sustainability of the existing system begun to be questioned because of new scientific data.Footnote8 Climate change was seen as the most important threat leading to a global campaign aiming among other things at the reduction in the use of fossil fuel and the promotion of alternative renewable forms of energy.Footnote9 The expansion of environmental activism particularly popular among young people was accompanied by increased funding made available to research aiming to study environmental problems and propose solutions in the form of green policies serving sustainable growth. On the more radical spectrum of the ecology movement the notion of degrowth was put forward as the only viable strategy for the planet along with condemnation of what were seen as an increasing sophistication of green washing by political elites and commercial interests (Kallis Citation2018).

The threat of the pandemic was initially and primarily about health and consequently had an existential dimension tied to it. In April 2020 the heads of the major United Nations agencies issued an urgent call to fund the global emergency supply system to fight COVID-19 because it “knows no borders, spares no country or continent, and strikes indiscriminately” pointing out that “humanity is collectively facing its most daunting challenge since the Second World War” (WHO Citation2020a). In December 2020, the European Commission, begun its communication to the European Parliament and the Council “Staying safe during the winter” with the phrase “every 17 seconds a person dies in the EU due to Covid-19” (European Commission Citation2020). The external threat was this time a highly transmittable virus, which commanded the need to sacrifice one thing (freedom and welfare) to safeguard another (safety and even life, itself). Covid-19 threatened not just vulnerable individuals but carried the risk of collapsing public health systems in toto, and consequently potentially all individuals. Moreover, restricting its transmission, especially in overcrowded West European cities, necessitated that every individual needed to isolate herself, limit social contacts, even below the household unit, and physically avoid public space and where possible workplace.

The state undertook to oversee this temporary adjustment in everyday life, bore the immediate cost and compensated to some extent the decline in welfare through increased public spending in furlough schemes and temporary relief measures (Daly et al. Citation2020). Most importantly though the state intervened to ensure that citizens did sacrifice their freedom, attacking discursively all those that did not as “irresponsible” (Bajde Citation2020; Finlayson, Jarvis, and Lister Citation2023). Building on decades-long of forceful, authoritarian practices (Wilkinson Citation2018), the state assumed emergency powers, legitimated through references to the exceptional circumstances and identified itself with “science” assigning advisory role to selected health experts and using their recommendations as justifications of the measures adopted (Lynggaard, Dagnis Jensen, and Kluth Citation2023). As France’s president famously framed it, the unprecedent measures were necessary because “we are at war” (BBC Citation2020).

The dominant policy framework was initially varying forms of lockdown internally and movement restriction at the borders and promotion of telework, subsequently obligatory face coverings and finally vaccinations. All these were seen as temporary, necessary evils and essentially voluntary; nevertheless, coercion was also used in the form of increased police powers and penalisation of non-abiding citizens (Tidman Citation2020). While the form and the severity in the imposition of restrictions varied across different states, even in the liberal ones, where emergency rules and regulations resembled more recommendations and guidelines rather than full-fledged legal requirements, there was a significant volume of penalties imposed. In England alone for example there were 85,000 Fixed Penalty notices issued in one year, while in the same period between March 2020 and March 2021, the Covid-19 restrictions changed 65 times (UK Parliament Citation2021). Although the pandemic’s long-term effects remain to be seen, the politics of fear and repressed freedoms that various studies have noted (Bieber Citation2022) do not really signal change in the dominant policy paradigm. This remained entrenched in the frame of existential questions, as with the climate crisis countries were increasingly responding to, and in the spirit of authoritarian responses and crackdowns on civil liberties or human rights, for the collective sake.

During 2020 and 2021 diverse dissenting views were voiced, gradually gaining pace and support as people became disaffected with the restrictive measures adopted to combat the pandemic (Al Jazeera Citation2021). Oppositional narratives reversed the dominant claim about the threat from the virus and argued that the real threat came from the practices adopted to combat it rather than the virus itself (Joffe Citation2021; Wu Ming Citation2021). The severity of the virus was downplayed and in some more extreme versions its existence was discounted altogether and/or seen as a product of a global conspiracy (Eichhorn et al. Citation2022; Shackle Citation2021). At the more mainstream range of the dissenters’ spectrum, the emphasis was placed on the threat of authoritarianism with increased state surveillance and coercion and the democratic backsliding with the suspension of civil liberties and concentration of power at the hands of the executive (Lynggaard, Dagnis Jensen, and Kluth Citation2023).

More progressive and radical left voices pointed to environmental destruction as the underlying cause of the pandemic and neoliberal austerity as responsible for the poor state of the public health systems (BMA Citation2020; Vidal Citation2020). The ambitious EU-level campaign “No profit from the pandemic” however failed to reach the needed threshold in seven countries and secure 1 million signatures (European Citizens Initiative Citation2022). In all, dissent to the management of the pandemic challenged and criticised established policy frames, organisational forms, and decision-making modes, nevertheless, it did not really signal novelty in terms of rationalising the threat of the pandemic. Among dissenters the pandemic was either perceived as a grave biological danger with wider socio-economic roots, the older threats underlying the new threat; dismissed as unimportant, for example in relation to other viruses; or it was contested as a sham through conspiracy theories. Distinct worldviews produced distinct logics of appropriateness in assessing the new threat. Yet, neither did the views expressing conspiracy theories or underplaying the virus due to some sort of alternative view of science nor those focusing on authoritarianism, the environmental underlings of Covid-19 or the disastrous effects of austerity on public health and welfare, entail a break with the past. That is, there is no shift in the dissenting ideas during the crisis compared to dissenting ideas before the crisis. That said, some novelty is to be found in the debates about science and its political role as well as the explicit opposition to state encroachment on hitherto private spheres, its prescription of individual behaviours and its curtailing of individual rights.

The wide range of views among the dissenters was also reflected in the policy frameworks suggested. While the primacy of individual rights against the state was a common thread, views differed with respect to the science and health aspects, especially after mass testing was introduced and after the vaccination programmes began. Opposition to the politicisation of science was at the ideological core of dissent, fed also by the big commercial interests involved, especially in the vaccination programmes (Sciacchitano and Bartolazzi Citation2021). At the extreme end, there was opposition to mainstream science per se with respect to the vaccines (Sturgis, Brunton-Smith, and Jackson Citation2021). Beyond the anti-vaxxers, and those opposed to vaccines in general, there was increased scepticism about the speed with which, these particular vaccines were produced and distributed bypassing regular, established vaccine protocols. When some states in their effort to promote vaccination, introduced in 2021 the “safe pass”, a negative test and/or a vaccination certificate as a requirement to enter some spaces for work or recreation purposes. There was dissent from wider societal sections who made a distinction between “opposition to vaccination” and “opposition to forceful vaccination”, through socially ostracising the unvaccinated and excluding them from much of the public space (DW Citation2021; Sherwood Citation2021).Footnote10

In the pandemic crisis, the “extreme centre” was much less isolated as the Centre-Right and Centre-Left hegemony could count also on the qualified support of a major section of the radical Left, the regular champion of protest. The common reaction to the pandemic of European radical left parties was to either align with the government or criticise measures on an ad hoc basis. The need to defend “science” and “rationalism” against conspiracy theorists and anti-vaxxers, whom although not a majority were centrally positioned amongst the crowds dissenting to Covid-19 management, denied the radical left from an opening (Russel Citation2023). The extreme Right was comparatively better positioned to offer leadership to the dissenters, but ultimately there was no clear opening for its values among the dissenting crowds either (Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Citation2022). Although nationalist populism was the space that sought the most to capitalise on anti-vax mobilisation, in the elections immediately following the fading out of the pandemic, that is, between the end of 2021 and 2023, the far-right in Europe witnessed a picture whereby most cases – except perhaps the Brothers of Italy and the Swedish Democrats – did not thrive. Party systems in Europe did not radically open, yet they did not close much either, since both the openings of the far right and a broader right-wing shift since earlier were relatively sustained and the downfall of the social democrats consolidated.Footnote11

Discussion

The impact of the pandemic largely faded by mid-2022, as the massive vaccination campaigns launched by West European states were successful, and societies entered a phase where restrictions were lifted, and public attention shifted away from the pandemic. Yet even if the threat of the virus subsided by 2023, its legacy in multiple spheres lingered on. At the political level, the state was largely insulated from public demands during the pandemic, a trait that may outlive Covid, while the enhanced crisis authoritarianism has set a precedent making this easier to invoke in the future. The secret dealings of the EU and national states with big pharmaceuticals for example, in combination with the reduced due to austerity ability of governments to manage healthcare systems may have contributed to the further erosion of trust (Eurofound Citation2022).

At the same time, the state has become more important, more interventionist and supportive of consumption, reaffirming its role as the only institution charged with maintaining social order (Jessop Citation2002). This double intervention, in the realm of health and thus social reproduction, in the realm of production and consumption as well as in the realm of civil freedoms has given rise to arguments about a broader change in ideological hegemony, a new statism whereby national sovereignty and economic protectionism supersede the market centred politics of neoliberal globalisation (Gerbaudo Citation2021). Our analysis points to a more qualified and more nuanced understanding of these signs of a “new statism”, questioning that the neoliberal paradigm has been shaken so much as to warrant talk of its replacement or phasing out. For one, “the new statism” is challenged by the history of neoliberalism itself, which has always been statist to some extent, as shown for instance in David Harvey’s (Citation2003) analysis of the neoliberal state in supporting the private market, so the breach with the past is arguably not that significant.

Moreover, as Van Apeldoorn and de Graaff (Citation2022) argue when examining recent major capital-state trajectories from a global level perspective, it is the market-directive function of the state (state steering of the accumulation process) that is being enhanced. What is underway is thus not a restructuring that reduces the power of the market, but a reconfiguration of the capitalist state’s relationship with it, bringing a global convergence among competing economic and political models. This process has arguably been ongoing since the early 2000s and can be seen in the changed operation of financial markets and central banks. The incrementally expanded regulation of the financial sector for example begun before the financial crisis (Quaglia Citation2014) and was only accelerated during and after it. The same is true of the centralisation and enhancement of the power of central banks, aimed at both increased protection of the sector through increased stability of the system. Similarly, the recent changes in the supply chains aiming at real-time visibility and cost efficiency, through enhanced technological upgrades, digitalisation, and analytics to achieve improved monitoring rationalisation and resilience were stimulated by the pandemic, but their roots precede it (Schoenherr and Speier-Pero Citation2015). The point here is that we have changes that serve continuity – changes in institutional forms aiming at the strengthening of the existing economic structures as opposed to institutional changes aiming or precipitating socio-economic restructuring.Footnote12

In , we identify both continuity and change in the ideational structures across the two crises. It should be clarified that the starting points, the “prior to the crisis” moment, upon which the impact of each crisis is assessed are different in the two cases: it is the prevailing conditions in mid-2000s and late 2010s respectively. In some dimensions of our model, continuity and change elements balance out. For example, the primacy of “the economy” in the financial crisis politics signified continuity – yet the understanding of that primacy as involving generalised welfare decline signified change. Whereas the policy frameworks implemented during the financial and the pandemic crises had elements of both permanence, such as putting technocracy above politics and sacrificing rights for the public good, as well as change, such as harsh austerity and harsh lockdowns, at the level of dominant definition of the threat the pandemic crisis exhibited more novelty. The causes of threat were solely external this time, the virus always came from outside the national borders, and while some citizens were blamed for “irresponsibility” and efforts were made to discipline them, they were not explicitly defined as a threat – the threat remained an elusive, immaterial force this time, only partly reducible to human actions and behaviours.

Table 2. Ideational structures across crises.

The dissenting discourse and the policies advocated by dissenters on the other hand both combined new as well as old ideas. In terms of the perceived causes of the threat and the blame direction, elements of continuity and change balanced out in both the financial and the pandemic crisis. In the financial crisis, the focus of dissenters on impoverishment and social inequality signified more continuity than change, but the blaming of the EU and Eurozone institutions for this championing of national and popular sovereignty constituted relative change. Supranational institutions as champions of capitalism were blamed in the past – but this time the targets, the critique and the proposed alternatives were much more specific. The defence of existing, previously won rights under attack, such as civil liberties and the right to healthcare, went in tandem with the claiming of relatively new rights pertaining to environmental sustainability and bodily autonomy. The World Health Organisation itself was led to frame the recovery from the pandemic as necessarily green if it was to be healthy (WHO Citation2020b). The slow-down especially during the 1st lockdown in early 2020 and the reduction of domestic and international travel and tourism which continued into 2021 made links with the climate emergency and the ideas of degrowth more salient, as argued by groups such as “Extinction Rebellion” and “Fridays for the Future”. These new rights which gained pace during the pandemic crisis were already acknowledged by the ruling elites, at least in theory, such as for example in terms of the new emissions’ regulations and the environmental targets set by the EU, or the non-enforcement of obligatory universal vaccination. Moreover, dissenters on the right incorporated the pandemic into pre-existing conspiracy-theory attitudes, while dissenters on the left raised the flag of anti-authoritarianism, welfarism and freedom.

Regarding the dynamics of hegemony, when examined together, both crises produced shifts. As per the ideological coordinates of conflict, the common reaction to the pandemic of European radical Left parties was to either align with the government or criticise measures on an ad hoc basis. There was a partial correspondence of Centre – Left and Centre – Right at the government level and the radical Left was caught off guard amidst policies that were clearly authoritarian yet pertaining to collective thinking and pointing to the public good. The extreme Right on the other hand had more political space yet limited ideological resources to become hegemonic in such a setting. Unlike the financial crisis, there was no policy alignment between the radical left and extreme right and therefore limited scope for the “two extremes” thesis under the umbrella of populism.

Concerning the political capital of specific party families, the financial crisis and its management via austerity, narrowed down the hegemony of Centre-Right and Centre-Left and produced openings for both the radical Left and the extreme Right. Against the “extreme centre” defending austerity, a counter-hegemonic discourse developed putting forward populist demands that were based on a national sovereignty framing. Whether advocating welfarism against austerity and spearheaded by the radical left or attacking the politicians in toto as in the apolitical/anti-political populist strands and/or following the extreme right and blaming the immigrants, there was political space openness, in a way that has been absent during the pandemic crisis.

The fact that “Western Europe” has been the unit of analysis does not mean that there was no variation across national settings. In both crises, both the hegemonic and the counter-hegemonic discourses and conflict politics exhibited some differences depending on the national government-opposition dynamics, and the historical and institutional traditions and contexts. We opted however not to zoom in on these elements for two reasons. Firstly because at least as the more advanced Western European democracies are concerned, national variation was not big enough in the indicators used in our model (threat, policy frameworks, lines of conflict). Secondly, because at the level of general historical development, this paper is interested in, it is the convergence across national settings that stands out.

Conclusions

In this article, we sketched a map of ideological configurations and used it to assess stability or interruption through a comparative historical perspective juxtaposing ideational structures across two moments of crisis in Western Europe. In doing so, we have shown the value of combining theories of hegemony and accounts of ideational structures and their expression in institutional dynamics and political competition. Our theoretical framework can be checked and tested for withstanding scrutiny, as much as it can be applied to other regions of the planet beyond the West, where political spaces and ideational traditions are differently drawn or where the pandemic has impinged upon populations much graver material damage.

On the empirical level and in terms of ideational structures, continuity and change in the pandemic, balance out to a second-order outcome towards change. The established ideological categories are still coherently and recognisably present; they were not eroded because of the pandemic debate. Importantly, we also challenge the idea of a significant shift in the dominant policy paradigm away from neoliberalism due to the pandemic. The reinforcement of the welfare state by governments in Western Europe was limited and temporary and oriented to social control; at no point was state commitment and support to corporate interests seriously weakened (Pleyers Citation2020). The identification of an external threat that warrants suspending normal freedoms, increasing surveillance, and blaming individual irresponsibility may signal the consolidation of authoritarian biopolitics, especially given that no solid, ideological, and cohesive opposition has emerged. The massive intervention of the state in the economy during the pandemic, and the readiness of national and EU elites to suspend deficit rules and allow national debt to climb should not be underestimated. This is a sign of ideological fluidity whereby the rigidity of neoliberal economic governance bends or more accurately it becomes evident that it can be bent. While this may deprive the left of a distinct agenda it is also true that elements of its agenda are diffused into wider society.

Although the realignments and currents noted have not changed the balance of power in the ideational realm, they nevertheless have had ramifications, even if chiefly in the style and scope of policy action by both hegemonic and counter-hegemonic forces. These may warn us towards incremental change that could manifested a longer-term relevance in the future. Yet, the pandemic appears more as “re-equilibration”, rather than critical ideological reconfiguration whereby a hegemonic shift away from neoliberalism “was proposed, considered, and narrowly rejected, thereby reinstating the previous path” of socio-economic relations (Capoccia Citation2016, 103). Changes in preferences and beliefs were not really registered among collective actors. The financial crisis can be understood as even less representative of ideational change, although the legacy of post-2008 has been imprinted in both the antecedent conditions of the pandemic and dissent to its management by governments. Shifts among movements and party systems did not produce a game-changing electoral landscape. This brings us to reconfirm that a destabilising crisis episode does not necessarily bring about radical realignments in the battle of ideologies, thus a diagnosis of crisis should not automatically suggest transforming political representations. Although issue priorities among collective actors in West European politics have partly realigned or have been re-signified in view of unfolding material developments, worldviews and the actions accordingly pursued by left, right and centre do not seem to suggest new, different path dependencies.

Finally, our conclusions should be approached with some caution, as at the time of research and writing, “slow outcomes” (Pierson Citation2004) of the pandemic, indeed, even of the financial crisis, may still not show. As the notion of a critical juncture implies a non-linear process because one change shapes all path dependencies looking ahead, it may be still early to say if what has changed during the pandemic or the financial crisis, as outlined in this paper, will have transformative impact on the world oh ideas. Nevertheless, the above withstanding, our graded approach to critical juncture theory, the fact that slow outcomes tend to leave trails, and the early signs of the pandemic’s aftermath in terms of both ideational and socio-political structures point to more nuanced than transformative ideological change.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their thanks to Adrian Wilkinson, and the panel participants of Historical Materialism conference in London (November 2022) for feedback given on an early draft of this paper. Also, to the editor of “Global Society” and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on subsequent versions of the manuscript.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gregoris Ioannou

Gregoris Ioannou is a reader at the Faculty of Business and Law, Manchester Metropolitan University. His research utilises political sociology and political economy frameworks to examine power dynamics in employment relations, as well as their cultural and communicational forms. He has published in numerous journals including ‘Economic and Industrial Democracy', ‘European Journal of Industrial Relations' and ‘Industrial Law Journal' and his latest research monograph (2021) with Routledge is titled ‘Employment, Trade Unionism and Class: The Labour Market in Southern Europe Since the Crisis’.

Giorgos Charalambous

Giorgos Charalambous is an associate professor of political science at the department of politics and governance, University of Nicosia. He works in comparative European politics and political sociology, focusing on political ideas, parties, mobilisation and political behaviour broadly conceived. He has published in numerous journals including ‘Mobilization', ‘Party Politics' and ‘European Political Science Review' and his latest monograph (2022) with Pluto Press is titled ‘The European Radical Left: Movements and Parties since the 1960s’.

Notes

1 West European countries share similar structures of political conflict (see further down in the text), and include Central Europe (France, Germany, Netherlands and the low countries, Austria, Switzerland, UK and Ireland), Northern Europe (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden,) and Southern Europe (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Spain, Malta). We do not compare West European countries between themselves nor with other country groupings. Our use of the category Western Europe should be understood as “a field” with which we demonstrate our conceptual approach rather than as a subject of empirical analysis.

2 Marx Citation2006 [1852]

3 Mahoney Citation2000

4 Volpi and Gerschewski Citation2020

5 In this context, for the first time in its history the IMF prescribed a global fiscal expansion (Lowery Citation2022).

6 The collapse of the Lehman Brothers was initially alluded to, then it was the bankruptcy of southern European states who could no longer service their debts and then it was the eurozone in general. In Cyprus the banks closed for weeks in 2013 until the bail-out (and an additional bail-in for the banks) was agreed and legislated and capital controls remained in place for months. In Greece, where formal state bankruptcy was threatened throughout the period 2010–2017, there was a similar albeit shorter closing of the banks and capital controls in 2015 during the referendum conducted on the 3rd bail-out plan. The uncertainty about the future and the spectre of chaos through the collapse of everyday money transactions, in a new national currency that would be constantly depreciated really frightened people – this fear was integral to the discourse that became eventually dominant.

7 The dilution of liberal democracy, emptied out of its political content has been debated since the 1990s with the notion of “post-democracy” coined by Crouch (Citation2004) capturing the zeitgeist at the turn of the Century. In the 2nd decade of the twenty-first century, social movements such as “Real Democracy Now” confronted this process head on.

8 Global methane emission from the energy sector went up more than 30% from 2000 to 2015 provoking alert about the speed of the already rising planetary temperature (IEA Citation2022). More generally the evidence pointing to the enhanced threats from the acceleration of climate change in the last decades has become prolific (e.g. Cramer et al. Citation2018; Anderegg et al. Citation2021).

9 Fridays for the Future (https://fridaysforfuture.org/), the international youth movement that begun in 2018, inspired by the activism of Greta Thunberg, is the key example here.

10 AP Citation2021

11 Despite social democratic advances in Portugal and Germany, the vote share of social democratic parties is some 1.4 percentage points lower in the post-pandemic period than in the period immediately prior to the pandemic (Krowel and Martin Citation2022).

12 Social inequalities generally increased during the pandemic but state intervention in the economy through increased spending on infrastructure and support for both business and labour prevented overt polarization (ETUI and ETUC Citation2021). This was made possible only at the expense of piling national debt, which European and international neoliberal institutions of governance were more than willing to accept because of the large and prolonged disruptions of demand and supply chains in the global economy that legitimated increased government spending in the light of fear of the worst (Giles Citation2021). The rhetoric of debt as a looming risk however begun to gradually re-emerge in the context of recovery (ESM Citation2021). Lizz Truss’ ousting from power in the UK when she was seen to be overstepping her hand with policies bound to pile up public debt is the most vivid example of this. And of course, the return to austerity afterwards (Smith Citation2022).

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. New York: Crown.

- Al Jazeera. 2021. “Thousands Protest amid Global Anger Against COVID Restrictions.” Al Jazeera, July 24. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/24/protesters-against-covid-restrictions-clash-with-police-in-paris.

- Anderegg, William R. L., John T. Abatzoglou, Leander D. L. Anderegg, Leonard Bielory, Patrick L. Kinney, and Lewis Ziska. 2021. “Anthropogenic Climate Change is Worsening North American Pollen Seasons.” PNAS 118 (7). https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073pnas.2013284118.

- AP. 2021. “Thousands Protest Against Vaccination, COVID Passes in France.” Associated Press, July 17. https://www.voanews.com/a/covid-19-pandemic_thousands-protest-against-vaccination-covid-passes-france/6208387.html.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2018. “Explaining Electoral Support for the Radical Right.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by Jens. Rydgren, 143–165. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bailey, David. 2020. “Mapping Anti-Austerity Discourse: Populism, Sloganeering and/or Realism?” In Left Radicalism and Populism in Europe, edited by Giorgos Charalambous and Gregoris Ioannou, 183–203. London: Routledge.

- Bajde, Domen. 2020. “Coronavirus: What Makes some People act Selfishly While Others Are More Responsible?” The Conversation, March 24. https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-what-makes-some-people-act-selfishly-while-others-are-more-responsible-134341.

- Barnett, Michael. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Sacrificial International Order.” International Organization 74 (S1): E128–E147. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081832000034X.

- Basu, Laura. 2018. Media Amnesia. London: Pluto Press.

- BBC. 2020. “Coronavirus: ‘We Are at War’ – Macron.” BBC, March 16. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/51917380.

- Béland, Daniel, and Robert Henry Cox. 2011. “Introduction: Ideas and Politics.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by Daniel Béland and Robert Henry Cox, 3–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berman, Sheri. 2001. “Ideas, Norms, and Culture in Political Analysis.” Comparative Politics 33 (2): 231–250. https://doi.org/10.2307/422380.

- Berman, Sheri. 2011. “Ideology, History and Politics.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by D. Béland and R. Henry Cox, 105–126. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bevir, Mark. 2000. “New Labour: A Study in Ideology.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 2 (3): 277–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.00038.

- Bieber, Florian. 2022. “Global Nationalism in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nationalities Papers 50 (1): 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.35.

- Blyth, Mark. 2002. Great Transformations. Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blyth, Mark. 2003. “Structures Do Not Come with an Instruction Sheet: Interests, Ideas and Progress in Political Science.” Perspectives on Politics 1 (4): 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592703000471.

- Blyth, Mark. 2011. “Ideas, Uncertainty and Evolution.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by D. Béland and R. Henry Cox, 81–101. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- BMA. 2020. “Austerity – COVID’s Little Helper.” Accessed December 20, 2022. https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/austerity-covid-s-little-helper.

- Boin, Arjen, Paul ‘t Hart, and Saneke L. Kuipers. 2017. “The Crisis Approach.” In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by H. Havidán, R. W. Donner, and J. E. Trainor, 23–38. Cham: Springer.

- Boin, Arjen, Paul ‘t Hart, and Allan McConnell. 2009. “Crisis Exploitation: Political and Policy Impacts of Framing Contests.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (1): 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802453221.

- Bratich, Jack. 2021. “‘Give Me Liberty or Give Me Covid!’: Anti-Lockdown Protests as Necropopulist Downsurgency.” Cultural Studies 35 (2-3): 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2021.1898016.

- Broome, André, Liam Clegg, and Lena Rethel. 2012. “Global Governance and the Politics of Crisis.” Global Society 26 (1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2011.629992.

- Capoccia, Giovanni. 2015. “Critical Junctures and Institutional Change.” In Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis: Strategies for Social Inquiry, edited by James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen, 147–179. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Capoccia, Giovanni. 2016. “Critical Junctures.” In In Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism, edited by O. Fioretos, T. G. Falletti, and A. Sheingate, 95–108. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Capoccia, Giovanni, and R. Daniel Kelemen. 2007. “The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism.” World Politics 59 (3): 341–369. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100020852.

- Charalambous, Giorgos, and Greoris Ioannou. 2017. “Party Systems, Party-Society Linkages and Contentious Acts: Cyprus in a Comparative South European Perspective.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 22 (1): 97–119. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-22-1-97.

- Charalambous, Giorgos, and Gregoris Ioannou. 2020. “Introducing the Topic and the Concepts.” In Left Radicalism and Populism in Europe, edited by G. Charalambous and G. Ioannou, 1–30. London: Routledge.

- Collier, Ruth B., and David Collier. 2002. Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Collier, David, and Gerardo L. Munck. 2017. “Building Blocks and Methodological Challenges: A Framework for Studying Critical Junctures.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15 (1): 2–9.

- Cramer, William, Joël Guiot, Marianela Fader, Joaquim Garrabou, Jean-Pierre Gattuso, Ana Iglesias, Manfred A. Lange, et al. 2018. “Climate Change and Interconnected Risks to Sustainable Development in the Mediterranean.” Nature Climate Change 8 (11): 972–980. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0299-2.

- Crawford, Neta C. 2018. “The Potential for Fundamental Change in World Politics.” International Studies Review 20 (2): 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viy034.

- Crouch, Colin. 2004. Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Crouch, Colin. 2011. The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Daly, Mary, Bernhard Ebbinghaus, Lukas Lehner, Marek Naczyk, and Tim Vlandas. 2020. “Oxford Supertracker: The Global Directory for COVID Policy Trackers and Surveys.” Department of Social Policy and Intervention. Accessed December 20, 2022. https://supertracker.spi.ox.ac.uk/.

- De Leon, Cedric, Manali Desai, and Cinhal Tuğal. 2009. “Political Articulation: Parties and the Constitution of Cleavages in the United States, India, and Turkey.” Sociological Theory 27 (3): 193–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01345.x.