1. Introduction

In late August 2021, academics and students of two prestigious liberal arts programmes at the National University of Singapore (NUS) received an email message. Yale-NUS College and the University Scholars Programme are two distinctly different programmes intended to provide students with a high-quality cross-disciplinary education, a core priority of NUS. While not entirely unexpected, faculty, students, and parents were nevertheless taken aback by news of a merger between these two programmes, and the matter ended up being discussed very widely, including in parliament. The ‘merger’ was officially justified as part of a larger reorganization of the university into colleges that would enable greater cross- and indeed, transdisciplinary collaboration in research and education.

The point of starting our editorial with this anecdote is twofold. First, it suggests the ‘supercomplexity’ (Barnett, Citation2000) of the contemporary university and the higher education landscape within which we, as academic developers, find (or sometimes lose) ourselves. Second, it explicitly connects this high level of complexity with what Bass (Citation2020, p. 6) calls the ‘wicked problem of learning’. Recognizing learning as a wicked rather than a tame problem means recognizing that higher education has ‘many interdependent complexities and a dynamic set of questions requiring extensive, ambitious, and unrelenting interdisciplinary investigation, innovation, and imagination, as all wicked problems demand’ (Bass, Citation2020, pp. 11–12). This requires a big-picture orientation to transdisciplinarity and ‘convergence research’: it is precisely because of this that NUS is reorganizing. As the ‘broader context surrounding the core activities of academic development – teaching and learning – is becoming more organizationally complex’ (Stensaker, Citation2018, p. 257), how might we as academic developers address this complexity proactively and meaningfully? How might we be part of, and indeed shape, this complexity? Doing so requires a strategic orientation to academic development.

The idea for this special issue first arose in 2018 during a course on strategic academic development (hereafter AD) in the context of Singapore higher education. The course, run by the Swedish academic developers Katarina Mårtensson and Torgny Roxå, was conceptualised as a professional development opportunity for participants, all of them academic/educational/faculty developers from across Singapore institutions. It was further planned as a vehicle for connecting participants in order to cultivate a scholarly community of practice of academic developers. Course participants could submit papers – developed from their course projects – for possible inclusion in the special issue, although the call for papers went beyond these participants and the majority of contributions do not derive from them.

The theme of this issue, ‘strategic academic development in Asia’, arises from our observation that AD in Asia is becoming more important, yet remains marginal in many universities in this vast and diverse continent. As in other parts of the world, it often stands in tension with other, competing priorities and different conceptions of academic work; moreover, there is lack of agreement as to what ‘academic development’ is and how academic developers – for the most part situated in centralized units known variously by such names as ‘teaching and learning centres’, ‘divisions for pedagogical development’, or increasingly, ‘learning sciences labs’ – can contribute to universities’ strategic priorities to advance teaching quality and innovation. In part, this lack of agreement can be attributed to the undertheorized nature of AD in much of Asia, as indeed also elsewhere in the world, which leads to a lack of common understanding of what it is. These issues are not unique to AD in Asian contexts, but we experience them as particularly acute.

In what follows, we examine different aspects of this complexity by considering the idea of ‘strategic’ AD, and we do so by contextualising this discussion in relation to Asia, since this part of the world is the focus of all of the thematic papers in this issue. At the same time, AD in Asian contexts is arguably at present rather marginal within the international discourse of higher education in general, and that of AD in particular – including within the pages of IJAD. We focus on the papers in this special issue to highlight some of the tensions that appear to be inherent in AD and explore the complex problems involved in taking a more strategic approach to AD in Asian contexts. We believe that these insights will be of interest to academic developers located not only in Asia but also beyond, as many of the issues cut across contexts and have larger relevance.

2. Academic Development in Asia

It appears that there is relatively little literature on AD in Asia, as compared to other regions of the world. Data relating to submissions as well as downloads of articles from IJAD, consistently indicate that the vast majority of these derive from North America, the UK, and Australia. In a survey of academic developers’ roles and practices from around the world, Asian responses constituted a paltry 3% while Europe garnered almost 50%, suggesting that AD in Asia is under-represented (Green & Little, Citation2016). As a result, the data from Asia were not reported in that paper. As highlighted in Zou and Geertsema (Citation2020), when compared to North American, European, and Australian/New Zealand contexts, studies on AD in Asian contexts are only just emerging ‘despite the fact that academic development programmes in most universities in the region have existed for two to three decades’ (p. 607). Likewise, Sugrue et al. (Citation2018) lamented in their review of over 100 peer-reviewed papers written on AD, that there is ‘a clear dominance of papers from the “Western” world and the English language; a “bias” in the literature that needs to be acknowledged’ (p. 2337).

Phuong et al. (Citation2015) conducted a review of AD in Southeast Asian higher education and found that there is a dearth of publications by local authors (especially academic developers). While the key reasons for the low number of publications were not elaborated, the focus of AD is predominantly on pedagogical improvement and self-directed learning in the domain of teacher education. The authors recognised that more could be done to enhance the role of AD for organisational development, including setting up campus-based AD centres and seeking collaboration opportunities. In a similar vein, Samarasekera et al. (Citation2020)’s survey of AD in medical education programmes in Southeast Asia (Singapore, Korea, Japan, and Indonesia) and Australia indicates that centres in these countries were set up for the predominant purpose of providing programmes aimed at improving the ‘teaching and learning skills’ of future health professions educators. Not surprisingly, the authors shared that research publication in this area in Asia is lacking. One of the reasons that they identify is language, which could be a major barrier as English is not the first-language in most of the countries; in addition, research skills might also be limited, given that carrying out quality research and publication in AD could be a daunting task for untrained medical health educators. To strengthen research publication, there is a need to collaborate and engage in productive partnership with other institutions. As recognised by Zhu and Li (Citation2019) in their book Faculty Development in Chinese Higher Education, there is a need to take a strategic approach and to enhance international perspectives of AD research through comparative and collaborative studies, to strengthen the overall quality of AD, and to expand the research methods and skills of academic developers to go beyond case analyses of data, and reliance on self-report data.

3. Towards theorising strategic academic development in Asian contexts

While AD has often been defined as being ‘about the creation of conditions supportive of teaching and learning’ (Leibowitz, Citation2014, p. 359), recently there have been attempts to understand it more broadly and holistically, and in relation to such larger contexts as organisational development. For example, Sutherland (Citation2018) argues that while AD involves support of teaching and learning, it should be approached holistically: in the context of engagement with academics in relation to their full practice and within the larger context of the whole academic role, the whole institution, and the whole an understanding that also informs the newly updated guiding questions for evaluating IJAD submissions and the journal’s working definition of AD. This more holistic view of AD situates it within debates about the complex purposes of education as involving the sometimes competing demands of qualification, subjectification, and socialization (Biesta, Citation2010).

Within these complex domains of purpose, AD focuses on changes in how we learn and how we make learning happen as professionals in higher education (Popovic & Plank, Citation2016; Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2015; Timmermans & Sutherland, Citation2020). To be strategic, academic developers need to learn from past experiences, analyse all available information, and synthesise what could be the way forward within the complex contexts of their practice (Baume, Citation2016; Gibbs, Citation2013; Land, Citation2001; Sugrue et al., Citation2018). A number of papers have taken a retrospective view of the changes in AD and tried to make sense of these trends in relation to their own or others’ experiences, to offer alternative or new perspectives for strategic AD. For example, Land (Citation2001) drew on models or conceptions of change to explore academic developers’ orientations to AD as well as their attitudes to change. This early work provides a working typology of strategic AD and a reminder that ‘though developers emerged from the study as a fragmented tribe [nonetheless] all recognise that a process of change must be negotiated if the developer’s role is not to be superfluous’ (Land, Citation2001, p. 10). A further important insight is that understanding the change process involves embracing both systematic as well as ‘chaotic nonlinear’ change strategies (Land, Citation2001, pp. 17–18).

Many others have pointed to the contested nature of AD, which includes such matters as whether it is a field, a discipline, a profession, a subject, or something else; whether AD is academic work, and accordingly whether academic developers should hold academic positions and conduct research, or instead be appointed in support/administrative positions with no research expectations; and how AD might negotiate: (1) facing towards university senior management, for example, through implementing and contributing to university policy and strategy; (2) at the same time building trust and meeting the needs of individuals as well as groups of academics and others who support teaching; (3) and the degree to which AD should be student-facing (see Barrow & Grant, Citation2012; Harland & Staniforth, Citation2003, Citation2008; Popovic & Baume, Citation2016). Gibbs’s (Citation2013) reflective account of the changing nature of AD acknowledged that it ‘is defined within an institution by the sub-set of change mechanisms in use that [units] are responsible for (and also, by default, the sub-set others are responsible for)’ (p. 5). The changes identified over time, such as a shift in focus from fine-tuning of current practice to transforming practice in new directions, and from AD being organisationally peripheral to being central, holds true also of more recent observations (see Bolander Laksov & Huijser, Citation2020). These documented change strategies provide useful signposts or roadmaps on the AD journey – to see one’s own AD practices in a different light and to prompt critical reflection.

Given the contested nature of AD, a wide range of models have been proposed, though most can be ‘encompassed within a consistent conceptual framework, grounded by three approaches to educational development focused on the individual, the institution, and the sector’ (Fraser et al., Citation2010, p. 56). But how do we as academic developers actually enable change in higher education? Following Stensaker (Citation2018) and Sutherland (Citation2018), we can understand AD as a form of cultural work that is focused on teaching through engagement with academics in relation to their full practice and within the larger contexts alluded to above, so that ideally, it will ‘move away from a “tips-and-tricks” approach to generic skill building’ (Greer, Cathcart, & Swalwell, 2021, p. 437) and instead work towards supporting academics ‘in identifying their own challenges in their own academic environments, and turning these into opportunities for change and development’ (Geertsema & Bolander Laksov, Citation2019, p. 3). Doing this requires a strategic, ‘joined-up’ (Trowler & Bamber, Citation2005) approach that integrates AD activities and initiatives to avoid fragmentation, such ‘that activities at the management level are linked to the activities at the operational level’ (Bolander Laksov, Citation2008, p. 91). AD itself then becomes ‘an activity with a longer-term perspective aiming to contribute to the transformation of the organization of teaching and learning activities’ (Bolander Laksov, Citation2008, p. 91), which requires a strategic approach to AD as culture change.

There are multiple reasons for the comparative marginalisation of Asian AD in the global literature, as well for what we discern as its marginal institutional status. One is the rapidity of the changes in higher education globally, especially in this part of the world (for example, see Marginson et al., Citation2011; Sanders, Citation2020; Sidhu et al., Citation2011). However, it is further no doubt linked to various well-documented constraints faced by academic developers as a field of practice globally. For example, back in 2006, in the specific context of post-Bologna European higher education (HE), Havnes and Stensaker (Citation2006) argued for the need to broaden the focus of AD: to link it more closely ‘to other processes related to quality and organisational development’ (p. 7). Like Gibbs (Citation2013), they trace the changing nature of AD in light of the various systemic constraints and challenges that it faces.

We postulate that the cogent list of constraints that Havnes and Stensaker enumerated remains valuable 15 years later, also in other contexts of HE, including Asia. They argue that HE is characterized by a multiplicity of cultures, which moreover are often hesitant about change and also ‘perhaps somewhat annoyed by increasingly being pressured to change’ (p. 10). There is also the best-known constraint of them all, namely the traditional priority of research over teaching (in research-intensive institutions especially, but also in higher education more generally), which makes teaching a low-status activity, one that is viewed as an individual process and tends to be weakly conceptualised by teachers and not subject to critical reflection. They further highlight what they term the ‘distributed autonomy’ of higher education, which constitutes a barrier to open communication, debate, and critique. Time pressure means individual teachers often find it difficult to allocate time to teaching development, and for institutions to prioritize it. Development of teaching is rendered even more complex in the context of higher education since ‘highly qualified disciplinary specialists might feel incompetent when they enter the challenges of the pedagogical discipline. … Expertise in the discipline does not necessarily imply expertise in teaching the discipline’ (pp. 10–11). And a final constraint of AD is that traditionally, ‘there are few incentives in the system that motivate staff and institutional leaders to participate in, or initiate, educational development’ (p. 11), a situation that remains true today, even if it is the case that there has been a significant rise in education-focused employment pathways, including in Asian contexts (Geertsema et al., Citation2018), as well as national attempts to professionalise university teaching, for example, recognition schemes such as that run by AdvanceHE in the UK, which has been spreading fast in some parts of Asia, including Bahrain, China, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand (Greer et al., 2021, p. 435).

The result is that AD in general faces institutional contexts characterized by diverse approaches to teaching, learning, and assessment, and by diverse expectations of what AD is about (for instance, whether it is remedial, executes corporate top-down policy, or involves peer learning relevant for localized practice). Academic developers tend to be seen not as academics (Harland & Staniforth, Citation2003, Citation2008) but as merely ‘trainers’, a situation that becomes entrenched as university teachers generally want to be provided with practical advice and technical support (Havnes & Stensaker, Citation2006, p. 13). Many if not most of these contextual constraints persist today, including ‘the well-known scepticism about academic development stemming from traditional disciplines and subject areas that consider teaching a menial and amateurish task’ (Stensaker, Citation2018, p. 275). These various constraints can be summarised as involving a tension between on the one hand a narrow, instrumental, technical understanding of AD, and on the other hand a broader, more strategic and cultural conception (see Havnes & Stensaker, Citation2006, p. 13). The technical understanding of AD is prevalent among the many university faculty and administrators who see the purpose of academic developers as providing ‘only practical advice and technical support’ – for example, to support academics in ‘constructively aligning’ their curricula, or by providing advice on using educational technology (Silander & Stigmar, Citation2021). As Stensaker clarifies, what is needed is less a ‘shift’ from the technical to the strategic, than a process of ‘layering’ AD: ‘These changes [in the function of AD] should not be seen as a shift from one mode to another, but rather as a form of layering where new tasks and responsibilities have been added to existing ones’ (Stensaker, Citation2018, p. 274); overall, the ‘dominant belief [still seems to be] that academic development should be about teaching and learning issues’ (p. 275). In other words, as the view of AD broadens, it is important to recognise that a primary concern with ‘teaching and learning issues’ remains key, and that accordingly, a more ‘strategic’ and ‘holistic’ AD will always need to ensure that this core concern remains central to practice and theory.

4. A ‘layered’ conceptualisation of strategic academic development in Asia (and beyond)

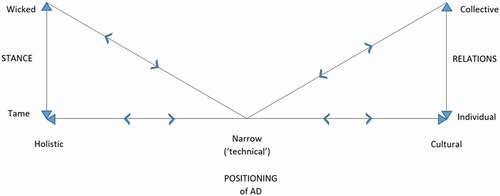

Building on the foregoing discussion, our view of strategic AD recognises the need to transcend a set of binaries that are baked into AD: the ways it is seen and practised (see Macfarlane, Citation2015). It is a reorientation that includes but at the same time moves beyond a view of AD activities as technical, focused on practical advice and technical support, and has a more expansive vision oriented towards feeding into and changing institutional culture in relation to, and in alignment with, strategic institutional goals – and indeed in relation to the problems and purposes of higher education. In this ‘layered’ understanding of AD, it becomes strategic when it incorporates, but goes beyond, AD as pedagogical development; when it moves towards a more holistic view that includes curriculum and an engagement with knowledge, and ultimately in the direction of organisational development. below illustrates this ‘layered’ view of strategic AD as integrating three overlapping continua: (1) position, (2) stance, and (3) relationships.

Positioning (or re-positioning) AD can be seen as a strategic move when we take into consideration a wider, more inclusive view of AD that expands beyond a narrow conception of providing teachers with teaching skills, to include also cultural work (Stensaker, Citation2018) or a more holistic approach (Sutherland, Citation2018). While the literature suggests that leadership plays an important role in shaping or supporting this strategic AD positioning (see Fossland & Sandvoll, Citation2021), academic developers do have a choice about how we take these different conditions/constraints/contexts into account, to enable strategic change in our own institutions. In short, where do we see ourselves in relation to others (or what is happening)?

Taking a strategic stance involves negotiating the continuum from tame to wicked: rather than regarding AD as solving a tame problem or taking a ‘marginal’ stance, we should problematize our approach to professional learning and adopt a wicked problem stance (Bass, Citation2020). This does not mean that we treat every problem as highly complex and thus as a barrier, but instead that we leverage on an integrated and adaptive approach which draws from individual learning as well as learning in an ecosystem (Kirst & Stevens, Citation2015). The question to ask ourselves is: ‘What is the wicked problem?’

To move strategically from a narrow to a broader view of AD, also involves navigating complex relationships within the organisation and beyond. In this respect, we draw on work within a social realist frame, which sees a key purpose of higher education as providing students with epistemic access that enables a transformative, theoretically grounded relationship with knowledge (Ashwin, Citation2020; Wheelahan, Citation2010; Young & Muller, Citation2016), as well as concepts from social practice theory, such as Trowler’s teaching and learning regimes (Trowler, Citation2020) and professional/significant conversations (see Pleschová et al., Citation2021; Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009). Based on such concepts, we argue that a collective approach is both critical and beneficial for strategic AD in Asia. In other words: ‘How can we work together?’

We now move to a discussion of the papers in this special issue to consider this ‘layered’, integrated conception of strategic AD in specific Asian contexts, as academic developers work to overcome the set of tensions we have discussed above.

5. Overview of papers

The papers in this special issue all grapple, in different ways and to different degrees, with the tension between a view of AD as technical and AD as strategic. The authors of these papers yearn to move beyond an understanding of teaching as the concern of individual teachers, where AD is focused just on change in classroom performance, and instead to recognise that ‘any educational process is collectively produced’ (Ashwin, Citation2020, p. 97). The papers, in their different ways, aspire to a larger, more holistic view of what teaching involves, and how AD can become more ‘worldly’: that is, how it can foster change beyond individual teachers while yet supporting them. In short, we discern attempts to move beyond seeing ‘the problem of learning in bounded isolation in the context of learning design, learning goals, outcomes, and assessment of institutional effectiveness’ (Bass, Citation2020, p. 19), and instead as requiring a ‘transdisciplinary approach [that] is not just about disciplines or academic expertise, but also about functional role, identity, and perspective [and that regards everyone] as learners, inquirers, researchers, and agents of change’ (p. 21). It is just this shift that marks strategic AD as we consider it in this introductory paper, with reference to the articles included in the special issue.

The main contribution of the first article, by Mårtensson and Roxå, is to provide a framework for understanding the development of academic developers. Before discussing the five dimensions that they identify, it is worth highlighting a key methodological aspect of their paper, namely the value that they attach to moving beyond a particular context. The authors note that a key factor that enabled them to write their paper was moving out of their own context, or rather, connecting that context and their experience with that of others. As they put it, ‘when moving between contexts, our own experiences came into focus through interactions with colleagues with experiences of academic development practice in different parts of the world’ (p. 406). From this, we can infer that while attention to one’s specific context as an academic developer practitioner and scholar is essential, there is an element of liberation in stepping beyond that context: being confronted with the views, concerns, and contexts of others; relating one’s own context to that of others–seeing ‘the bigger picture’. While on the one hand AD practice is highly contextual, by implication such practice can stagnate when it is not aware of a bigger world, and when it is not framed by values, principles, and knowledge that transcend that context. And this, to us, constitutes a key tension that is implicit in thinking strategically about AD: to be strategic, it needs to be attuned to the local context in which it is located and aligned with institutional priorities; but on the other hand, to be strategic it also needs to transcend that context so as to ‘see the bigger picture’. This is a tension inherent in mapping the global and the local that we can trace throughout the contributions to this special issue, and we maintain it proves to be a useful lens for looking at the tension between challenges and opportunities (Geertsema & Bolander Laksov, Citation2019).

Mårtensson and Roxå identify five dimensions in the development of academic developers:

expanding horizons in AD;

widening professional orientations;

intensified focus on ‘the others’;

academic developers as a) users and/or b) producers of research;

perceptions of the frames within which academic developers work.

What is especially noteworthy about these dimensions is that they helpfully trace a strategic orientation as being foundational to the developmental trajectories of academic developers, as expanding by moving from a narrow, technical focus and a primary concern with academic developers and our problems, towards a much broader view that might eventually involve that ‘ADs [academic developers] gain strategic positions within institutions and are offered responsibilities in collaboration with institutional leaders as ‘brokers’ and ‘bridge-builders’ (p. 414). And increasingly, academic developers themselves are becoming institutional leaders, with a theoretically grounded understanding of higher education that can enable a more thorough-going strategic approach to AD (Denney, Citation2020).

In the second paper, Anjum, Fraser and Thomas consider the professional growth experiences of six Pakistani academics teaching in universities, which were collected through individual interviews and iteratively analysed to address the research question: ‘How do Pakistani academics seek processes of professional growth within their poorly resourced teaching context?’ (p. 419). They identify four themes–relationship, quest, creativity, and optimism–to unpack and re-construct a narrative of AD from the academics’ perspectives that reminds us about the need for culturally responsive and contextually sensitive approaches to support professional growth and learning. What stands out in this paper are the positive mindsets of the academics to take control of their own learning despite the impoverished conditions in which they find themselves, and despite the lack of formal professional development opportunities. Behind the encouraging stories of personal struggles and growth is a powerful lesson, namely the need to draw on academics’ own volition and agency to negotiate and overcome a deficit view of professional development, and building on a strong sense of academic identity to go beyond passive cultures and notions of helplessness. AD in this study involves reframing a teaching problem (due to a lack of resources) as a self-inquiry problem – where the academics themselves take on the role of academic developers to seek and create opportunities for learning.

Although the interviews were carried out separately, the overall bigger picture painted helps to inform our understanding of strategic AD by showing that collectively, the academics struggle to ‘transcend’ their deficit situations/conditions by negotiating an alternative narrative that speaks of relationship, quest, creativity, and optimism. The authors call for a more holistic approach that connects ‘academic developers, institutional leadership, and higher education authorities’ (p. 429), which echoes Mårtensson & Roxå’s call for academic developers to collaborate with institutional leaders as brokers. As three of the participants in the study put it, ADs need to focus on collaboration in the context of bigger picture concerns that go beyond technical, ‘instrumental “what works” approaches to development’ (p. 429). While the ‘tips and tricks’ or ‘what works’ is of course important, ‘what is good or morally appropriate’ (p. 430) is equally as important and requires moving towards the ‘layering’ of a much more holistic approach to AD that would take care to connect with academics also on their own terms: in relation to their identities, their professional and personal struggles, and in the context of their disciplines. As ADs, we ‘“must act as both managers and mentors” (Najma), as “co-learners who know how to relate new content to our experiences” (Irfan), and in the context of “peer-to-peer learning” (Zaynab)’. This would require ‘a common strategic purpose among the stakeholders in higher education’ (p. 430). Since this was lacking, ‘participants revealed a real discordance between the individual academic and the system. Influenced by their regional realities and exercising a mix of “what works” and “what is good or morally appropriate” in their profession, these academics long for a learning-enriched professional culture to realise their ideals and values in teaching’ (p. 430).

Greer and colleagues conducted an action research project to investigate the effects of a combination of a teaching development programme and professional recognition through AdvanceHE’s Higher Education Academy (HEA) fellowship scheme, focusing on the teaching self-efficacy of academics in Shanghai, Chengdu, and Hong Kong SAR. Educators in the participating universities attended a three-day programme that was designed to be taught locally by practising Australian academics active in teaching and research, with content aligned to the UK Professional Standards Framework (PSF) and situated within the Chinese and Hong Kong SAR contexts. Professional recognition via an application for Associate Fellow, Fellow, or Senior Fellow of the HEA, was offered to participants, with formal mentoring by the academics teaching in the programme through video conferencing. The programme adopted a cognitive apprenticeship framework, whereby participants were encouraged to reflect on their own learning within the context of their practice and efforts were made to ensure that the content was relevant to participants, focusing on local quality assurance practices and acknowledging the ‘sensitivity of challenging norms of teaching practice that historically centre the academic rather than students’ (p. 438).

The findings of this study showed that participating in the programme and submission for professional recognition both improved teaching self-efficacy. The success rate for achieving professional recognition was 97%. A key implication for AD is the need for thoughtful design and integration of professional development programmes that are relevant to educators in their local context and provide opportunities for both personal and career growth. Seen through a strategic lens, AD of the participants involved not only the ‘technical’ aspects of what HEA standards had to offer but also an expanded view of ‘cultural work’ (Stensaker, Citation2018) by leveraging on the career growth opportunity and aspiration of the individual participants. Furthermore, the academic developers were able to take on a strategic stance by conceptualising the implementation of PSF as introducing a ‘common language’ for learning and thinking about university teaching. The authors argue that the programme helped to foster mutual learning of the participating educators from China, Hong Kong SAR, and Australia ‘using the PSF as a common framework or language to think about learning and teaching’ (p. 443). They also observed that both Chinese and Australian educators appear to share similar concerns about learning and teaching, and found the PSF useful to guide their development.

Nguyen and Pham locate their contribution firmly in the context of Asia, more specifically, that of the Confucian heritage culture of Vietnam. Their focus is peer review of teaching, a practice that, as they highlight at the start, is widely recognised as having the potential of being ‘strategic in higher education to improve quality teaching’ (p. 448). This is a key aspect of what Mårtensson and Roxå term ‘the expanding scope of academic development globally’, as it is increasingly being valued by institutions as a way of driving improvement. At the same time, Nguyen and Pham articulate the multiple challenges involved in implementing peer review of teaching, and the need for a theory with appropriate models to underpin such implementation. They usefully discuss three models for peer review of teaching: the evaluation model, which has the potential to promote an evaluative improvement culture but suffers from the likelihood that it will be perfunctorily practised when institutionally required; the developmental model, often used by academic developers and institutions for improvement of practice, which can promote critical reflection but has the drawback that distance in relationship between reviewer and reviewee may militate against an open and rich dialogue about teaching; and the collaborative model, which is premised upon mutual respect and trust, though this may hinder critical feedback.

In the context of higher education in Vietnam, peer review of teaching is not used for academics’ appraisal though it may be used for quality assurance purposes. The study reports on the implementation of formative peer review of teaching at a Vietnamese university with the goal of improving reflection and teaching practice, for which reason the collaborative model was chosen. Within this context, given the centrality of Confucian values, harmony and its articulation in the notion of face is an important factor that affects the design and implementation of peer review of teaching. However, their data reveal that while formative peer review requires ‘principles of reciprocity and parity’ (p. 451), this requirement then results in tensions within a hierarchical Confucian context that values harmony. The paper foregrounds the importance of relationships built on reciprocal respect within a Confucian context, which as pointed out implies the need for an institutional armature that integrates peer review into the fabric of the institution for it to have impact. In addition, institutions need to show academics that they value participation in peer review; for example, through adequate preparation for peer review as well as appropriate rewards and incentives (p. 459). Peer review of teaching, to be effective, needs to be weaved into the institutional fabric since one-off observations and dialogues have limited impact; ‘academics thought that one semester was too short for them to make changes’ (p. 458). Such a more extensive time commitment on the part of academics would require an institutional investment, to prepare academics engaged in it for full participation in an iterative cycle of review, preparatory discussions, and feedback dialogues that would foster a collegial culture of sharing (Hendry et al., Citation2021). Enabling such a productive approach to peer review would involve appropriate pairing of academics and support to guide academics on how to give culturally sensitive feedback (p. 458) so as to develop a ‘collegial culture that values this kind of scholarship of teaching’ (p. 458). Beyond working with the individual academics, however, the authors recognize the need to situate peer review of teaching schemes at an institutional level that respects academics’ autonomy, so they have the flexibility ‘to establish their agendas and design steps in the intervention to suit their schedule, and be given ownership’. Clearly, ADs have a role to play here that goes beyond ‘training’ by connecting peer review of teaching with higher-level concerns.

The final contributions are both reflections on practice. Ng situates her reflection within the context of an institution-wide strategic push for e-learning in Hong Kong. The author was responsible for supporting six academics in designing and implementing a flipped-classroom approach, as one of the pedagogical approaches aligned to the strategic thrust of the university. Drawing from her experiences in the project, Ng considers two key questions: the degree to which students are able to ‘self-learn’, using out-of-class online materials, and the extent to which teachers’ IT competency affect their flipped-classroom implementation. In general, students found a flipped-classroom approach helpful in their learning and were able to use the online materials effectively and appropriately. The findings indicate that technical IT competencies are important, but insufficient for bringing about effective use of a flipped-classroom approach. Instead, a more layered, strategic approach is needed: ‘implementing a successful flipped classroom requires a culture of sharing, with concerted effort by students and teachers’ (p. 465), supported by ADs, in particular to foster regular conversations about practice and collaborative sharing of successful implementation experiences.

Chen provides an account of how the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) was institutionalised as a key priority of her university, in response to a national government initiative in Malaysia. As pointed out by other scholars (see Harland et al., Citation2014), this national initiative raised many challenges which ADs elsewhere would do well to take note of. Chen focuses on one framework for taking account of such issues and resolving them, namely Kotter’s eight-step model of organisational change. A key aspect of using this model as a guiding framework for planning institutional change within a hierarchical educational culture was to ensure ‘buy-in’ not only ‘from all relevant stakeholders’ (p. 470), which she recognises as ‘indispensable’, but crucially also from the university’s top management’. SoTL may offer an opportunity for culture change if it becomes enculturated in the institution, which requires a clear vision and strong leadership, with institutional support from senior management and departments, coupled with great sensitivity to academics in the context of their disciplines.

6. Implications and directions for future research

What are the practical implications of this special issue and the contributions to it? What all of them suggest is the need for AD to be more strategic, to become part of the institutional conversation about education. How might we reach this goal? To end, we offer a few suggestions for consideration.

We started work on this special issue before the COVID-19 pandemic. If anything, the pandemic has underscored the importance of a more strategic approach to AD. Across the world, and certainly in Asian contexts, educational technology has been massively pushed by institutions, and for understandable reasons. There is a narrative we have come across in conversations with colleagues that during the pandemic, academic developers have become more highly valued; however, in our experience, institutions have been reactive rather than reflective and academic developers have often been further reduced to ‘technical support’ staff at the expense of more thoughtful AD work; often, including in our own case, academic developers in Asian contexts have not been part of strategic institutional conversations for mitigating the effects of the pandemic and rethinking the institutional fabric.

To be part of such conversations, AD needs not just to have champions across multiple institutional levels, from the individual/micro, to the network/meso, and the systems/macro level (Hannah & Lester, Citation2009), but as academic developers we ourselves need to engage in strategic leadership in and across these levels. The condition for this is the development of what Shulman (Citation1986, p. 12) terms ‘strategic knowledge’, which goes beyond (but includes) approaching teaching as a technical ‘skill’ based on propositional knowledge, and moves towards strategic knowledge as grounded ‘judgment’. Such ‘strategic knowledge’ needs to be added to ‘pedagogical content knowledge’ since, as McLean and Ashwin (Citation2016, p. 98) write, ‘it bestows the flexibility to judge, to weigh alternatives, to reason about ends and means, and to teach self-consciously and reflectively’. Strategic pedagogical knowledge does justice to the complexity of the scene of university teaching and, as Shulman recognized, is founded on a rich case literature (Shulman, Citation1986, pp. 11–13). Building a cadre of scholars and practitioners who possess such strategic knowledge is needed for the education of academic teachers, if such an education (that is, AD) is to have credibility and impact. Moreover, building such a cadre of academic developers with deep knowledge of the discipline and curriculum as well as of pedagogy will take a shift in the culture of higher education institutions. How this might be done is a key area for future research. We hope to have contributed towards building a foundation for such research through our attempt here to move toward theorising strategic AD in terms of a ‘layered’ view, one that involves integrating the dimensions of positioning (or re-positioning) AD, a strategic stance that involves negotiating the continuum from tame to wicked, and navigating complex relationships within the organisation and beyond.

This shift in culture is essentially that traced by Mårtensson and Roxå’s (this issue, p. 411) account of directions for the development of academic developers: ‘development is not necessarily what ADs do, but instead is what happens in the organisation of which an individual AD is a part’. An intensified focus on the others, in this case the academics, leaders, staff, and students with whom academic developers work – such that these people themselves become ‘academic developers’ – has the potential for a positive effect.

[Development] is no longer limited to, nor solely dependent on, what ADs do. They do not need to be present everywhere and every time when things happen. They can start to do things that are more intentionally – strategically – targeted towards longitudinal development. Sustainable change happens in the complex midst of various practitioners’ work, rather than as a direct result of interaction with an AD. Thereby development becomes ongoing instead of occasional. The focus moves towards the agency of the others. (2021, p. 411)

In other words for ‘the educational development centre … to be transformed from a merely technical activity focusing on how individuals become good teachers, into having a broader focus in which the organisation, frameworks and infrastructure surrounding the teaching and learning experience is addressed’ (Havnes & Stensaker, Citation2006, p. 19), a whole-of-institution approach with ‘joined-up thinking’ (Trowler & Bamber, Citation2005, p. 82) is needed. We started this paper by offering an example from our own context of the ‘supercomplexity’ of higher education, and asked how we as academic developers are to address it. A strategic approach to AD requires coherent, synthesizing knowledge building and theorizing of higher education and of AD itself, while at the same time being oriented to academics’ practical priorities and needs. Only through such a ‘layered’ approach can learning as a wicked problem be addressed, not only in Asia but beyond.

IJAD update and thanks

Over the last several months, the editorial team has worked on a set of question prompts that are intended as criteria for evaluating IJAD submissions. We hope these guiding questions may be helpful not only to reviewers and editors, but also to authors. We are keen to avoid a restrictive set of rules, hence the decision to phrase the criteria as questions. Since the questions assume a shared understanding of academic development, we have further drafted a working definition, albeit in full awareness of the complexity of the task and therefore the likely incompleteness of any such definition. You will find this document towards the end of the issue.

As is customary in our final issue of the year, in the online version we include a list of everyone who was involved in reviewing articles over the past year: our heartfelt thanks to all the peer reviewers who contribute to developing academic development by reviewing for IJAD.

And finally, at the end of 2021 co-editor Peter Felten (Elon University, United States of America), will be rotating out of this role after two terms. The IJAD editorial team wishes to express our immense gratitude to Peter for his leadership, wisdom, generosity, and friendship over the years. In the next issue, we will introduce the new member of the editorial team.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Torgny Roxå and Katarina Mårtensson for agreeing to offer a strategic development course for Singapore academic developers in 2018, and for acting as our critical friends: we would like to thank them especially for their insightful feedback on this paper. We wish to thank all the contributors and reviewers, as well as colleagues locally and abroad with whom we have discussed the topic of this special issue.

References

- Ashwin, P. (2020). Transforming university education: A manifesto. Bloomsbury.

- Barnett, R. (2000). Realizing the university in an age of supercomplexity. SRHE & Open University Press.

- Barrow, M., & Grant, B. (2012). The ‘Truth’ of academic development: How did it get to be about ‘Teaching and Learning’? Higher Education Research & Development, 31(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.602393

- Bass, R. (2020). What’s the Problem Now? To Improve the Academy, 39(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.102

- Baume, D. (2016). Analysing IJAD, and some pointers to futures for academic development (and for IJAD). International Journal for Academic Development, 21(2), 96–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1169641

- Biesta, G. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Routledge.

- Bolander Laksov, K. (2008). Strategic educational development. Higher Education Research & Development, 27(2), 91–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701805226

- Bolander Laksov, K., & Huijser, H. (2020). 25 years of accomplishments and challenges in academic development – Where to next? International Journal for Academic Development, 25(4), 293–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1838125

- Denney, F. (2020). Understanding the professional identities of PVCs education from academic development backgrounds. International Journal for Academic Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1856667

- Fossland, T., & Sandvoll, R. (2021). Drivers for educational change? Educational leaders’ perceptions of academic developers as change agents. International Journal for Academic Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1941034

- Fraser, K., Gosling, D., & Sorcinelli, M. (2010). Conceptualizing evolving models of educational development. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 122, 49–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.397

- Geertsema, J., & Bolander Laksov, K. (2019). Turning challenges into opportunities: (re)vitalizing the role of academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 24(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1557870

- Geertsema, J., Chng, H. H., Gan, M., Soong, A., & Di Napoli, R. (2018). Teaching excellence and the rise of education-focused employment tracks. In C. Broughan, G. Steventon, & L. Clouder (Eds.), Global perspectives on teaching excellence: A new era for higher education (pp. 130–142). Routledge.

- Gibbs, G. (2013). Reflections on the changing nature of educational development. International Journal for Academic Development, 18(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.751691

- Green, D., & Little, D. (2016). Family portrait: A profile of educational developers around the world. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1046875

- Hannah, S., & Lester, P. (2009). A multilevel approach to building and leading learning organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.11.003

- Harland, T., Hussain, R., & Abu Bakar, A. (2014). The scholarship of teaching and learning: Challenges for Malaysian academics. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.827654

- Harland, T., & Staniforth, D. (2003). Academic development as academic work. International Journal for Academic Development, 8(1–2), 25–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144042000277919

- Harland, T., & Staniforth, D. (2008). A family of strangers: The fragmented nature of academic development. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(6), 669–678. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802452392

- Havnes, A., & Stensaker, B. (2006). Educational development centres: From educational to organisational development? Quality Assurance in Education, 14(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880610643584

- Hendry, G., Georgiou, H., Lloyd, L., Tzioumis, V., Herkes, S., & Sharma, M. (2021). ‘It’s hard to grow when you’re stuck on your own’: Enhancing teaching through a peer observation and review of teaching program. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1819816

- Kirst, M. W., & Stevens, M. (Eds.). (2015). Remaking college: The changing ecology of higher education. Stanford University Press.

- Land, R. (2001). Agency, context and change in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 6(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440110033715

- Leibowitz, B. (2014). Reflections on academic development: What is in a name? International Journal for Academic Development, 19(4), 357–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2014.969978

- Macfarlane, B. (2015). Dualisms in higher education: A critique of their influence and effect. Higher Education Quarterly, 69(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12046

- Marginson, S., Kaur, S., & Sawir, E. (Eds.). (2011). Higher education in the Asia-Pacific: Strategic responses to globalization. Springer.

- McLean, M., & Ashwin, P. (2016). The Quality of Learning, Teaching, and Curriculum. In J. Gallacher, P. Scott, & G. Parry (Eds.), New languages and landscapes of higher education (pp. 84–102). Oxford University Press.

- Phuong, T. T., Duong, H. B., & McLean, G. N. (2015). Faculty development in Southeast Asian higher education: A review of literature. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16(1), 107–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-015-9353-1

- Pleschová, G., Roxå, T., Thomson, K. E., & Felten, P. (2021). Conversations that make meaningful change in teaching, teachers, and academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 201–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1958446

- Popovic, C., & Baume, D. (2016). Introduction: Some issues in academic development. In D. Baume & C. Popovic (Eds.), Advancing practice in academic development (pp. 1-16). Routledge.

- Popovic, C., & Plank, K. M. (2016). Managing and leading change: Models and practices. In D. Baume & C. Popovic (Eds.), Advancing practice in academic development (pp. 207–224). Routledge.

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks–exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597200

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2015). Microcultures and informal learning: A heuristic guiding analysis of conditions for informal learning in local higher education workplaces. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1029929

- Samarasekera, D. D., Lee, S. S., Findyartini, A., Mustika, R., Nishigori, H., Kimura, S., & Lee, Y. M. (2020). Faculty development in medical education: An environmental scan in countries within the Asia pacific region. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 32(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2020.160

- Sanders, J. S. (2020). Comprehensive internationalization in the pursuit of ‘World-Class’ status: A cross-case analysis of Singapore’s two flagship universities. Higher Education Policy, 33(4), 753–775. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-018-0117-5

- Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004

- Sidhu, R., Ho, K. C., & Yeoh, B. (2011). Emerging education hubs: The case of Singapore. Higher Education, 61(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9323-9

- Silander, C., & Stigmar, M. (2021). What university teachers need to know - perceptions of course content in higher education pedagogical courses. International Journal for Academic Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1984923

- Stensaker, B. (2018). Academic development as cultural work: Responding to the organizational complexity of modern higher education institutions. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(4), 274–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1366322

- Sugrue, C., Englund, T., Solbrekke, T. D., & Fossland, T. (2018). Trends in the practices of academic developers: Trajectories of higher education? Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2336–2353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1326026

- Sutherland, K. A. (2018). Holistic academic development: Is it time to think more broadly about the academic development project? International Journal for Academic Development, 23(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1524571

- Timmermans, J. A., & Sutherland, K. A. (2020). Wise academic development: Learning from the ‘failure’ experiences of retired academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1704291

- Trowler, P. (2020). Accomplishing change in teaching and learning regimes: Higher education and the practice sensibility. Oxford University Press.

- Trowler, P., & Bamber, R. (2005). Compulsory higher education teacher training: Joined-up policies, institutional architectures and enhancement cultures. International Journal for Academic Development, 10(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440500281708

- Wheelahan, L. (2010). Why knowledge matters in curriculum: A social realist argument. Routledge.

- Young, M., & Muller, J. (2016). Curriculum and the specialisation of knowledge: Studies in the sociology of education. Routledge.

- Zhu, X., & Li, J. (2019). Faculty development in Chinese higher education. Concepts, practices, and strategies. Springer.

- Zou, T., & Geertsema, J. (2020). Do academic developers’ conceptions support an integrated academic practice? A comparative case study from Hong Kong and Singapore. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(3), 606–620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1685948